Abstract

Flavor is an important quality of mature tomato fruits. Compared with heirloom tomatoes, modern commercial tomato cultivars are considerably less flavorful. This study aimed to compare the flavor of 71 tomato accessions (8 pink cherry, PC; 11 red cherry, RC; 15 pink large-fruited, PL; and 37 red large-fruited, RL) using hedonism scores and odor activity values. Taste compounds were detected using high-performance liquid chromatography. Volatiles were detected using gas chromatography–olfactometry–mass spectrometry. The flavor of tomato accessions can be evaluated using the DTOPSIS analysis method. According to the results of DTOPSIS analysis, 71 tomato accessions can be divided into 4 classes. Tomato accessions PL11, PC4, PC2, PC8, RL35, RC6, and RC10 had better flavor; accessions PC4, PC8, RC10, RL2, and RL35 had better tomato taste; and accessions PL11, PC2, and RC6 had better tomato odor. The concentrations of total soluble solids, fructose, glucose, and citric acid were shown to positively contribute to tomato taste. Tomato odor was mainly derived from 15 volatiles, namely, 1-hexanol, (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol, hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-heptenal, (E)-2-octenal, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, (Z)-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadieal, 2,6,6-timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, (2E)-3-(3-pentyl-2-oxiranyl)acrylaldehyde, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, methyl salicylate, 4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol, and 2-isobutylthiazole. Significant positive correlations (P < 0.05) were detected between the compound concentrations and flavor scores. The above-mentioned compounds can be used as parameters for the evaluation of flavor characteristics and as potential targets to improve the flavor quality of tomato varieties.

Keywords: taste compound, volatiles, hedonism score, odor activity value, DTOPSIS analysis

Introduction

Tomato fruits are important dual-use (vegetable and fruit) products (Razifard et al., 2020). Because of their high nutritional value and various volatiles with delicious tastes and odors, tomato fruits are widely consumed worldwide (Zhu Y. et al., 2018). In 2018, tomato production reached 182.26 million tons all over the world (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2020). However, compared with heirloom tomatoes, modern commercial tomatoes have poor flavor, which can cause consumer dissatisfaction (Klee, 2010; Kanski et al., 2020). The flavor of tomato fruit mainly comes from soluble sugars, organic acids, amino acids, and volatile compounds. Compared with the wild or heirloom tomato varieties, modern tomato varieties have decreased many flavor compounds (fructose, glucose, citric acid, and at least 13 volatiles) throughout the process of domestication and improvement (Tomato Genome Consortium, 2012; Lin et al., 2014) because breeders serve growers, not consumers. Growers require tomato varieties with high yield, strong disease resistance, and a long shelf-life to ultimately ensure high returns (Giovannoni, 2018; Zhu G. et al., 2018; Razifard et al., 2020). A negative correlation has been observed between fruit weight and sugar concentration (Folta and Klee, 2016; Tieman et al., 2017). In order to obtain higher yield, breeders ignored the improvement of flavor quality. However, as living standards rise, consumers need not only sufficient food supplies but also nutritious, healthy, and delicious tomato fruits and are willing to pay more for them. Therefore, there is an increasing demand for the restoration of heirloom tomato flavors.

The challenge of improving modern tomato flavor has intrigued researchers. To achieve this, it is essential to understand the relationship between flavor compounds and sensory preferences (Franklin and Mitchell, 2019). As we know, the higher sugar and moderate acid make the sweetness and sourness ratio more suitable, nutritious, and delicious. The volatile profiles were primarily responsible for the differences in flavor across tomato varieties (Zhang et al., 2015). Through biochemical analysis and sensory evaluation, previous studies have found that taste compounds (soluble solids, fructose, glucose, and citric acid) and dozens of volatiles [6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, β-ionone, 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone, (E)-2-pentenal, heptanal, (E)-2-heptenal, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, benzaldehyde, phenylacetaldehyde, 1-pentanol, (E)-3-hexen-1-ol, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-ol, 2-phenylethanol, 1-penten-3-one, 2-isobutylthiazole, 1-nitro-2-phenylethane, and 1-nitro-3-methylbutane] were significantly correlated with consumer preference and overall flavor intensity (Tieman et al., 2012, 2017; Tudor-Radu et al., 2016). Unfortunately, most of these flavor compounds have decreased in modern tomato varieties (Klee and Tieman, 2018). Thus, there is an urgent demand to increase the concentrations of sugar and preferable volatiles.

It is not supported by growers to sacrifice yield to increase sugar concentration of tomatoes (Goff and Klee, 2006). Volatiles may affect the flavor at very low concentrations, so they would be a candidate for flavor improvement without sacrificing yield. Volatile compounds are mainly derived from essential nutrients, such as fatty acids, carotenoids, and amino acids (Tieman et al., 2012), and can be responsible for tomato fruits having very different odor profiles. Volatiles can be affected by genotype, cultivation conditions, harvest-stage maturity, and postharvest treatment (Baldwin et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2019), which could change the level of precursor supply, gene expression, enzyme activity, and frequency of enzyme contact with substrates (Klee and Tieman, 2013). Although previous studies have conducted more comprehensive and deeper evaluations of tomato flavor compounds, the key tomato flavor compounds that are screened differ greatly in the published literature. To further clarify the flavor compounds of tomato and their effects on tomato flavor, we analyzed the taste compounds and volatiles, selected the key flavor factors through hedonism scores and odor activity values, and compared the flavor of 71 tomato accessions to supply reference data for the cultivation of tomato varieties with excellent flavor.

Materials and Methods

Tomato Materials

The 71 tomato accessions were inbred lines (Table 1), which were screened, segregated, and fixed by our lab—the Tomato Genetic Breeding and Quality Improvement Lab of Northwest A&F University. We used 8 pink cherry (PC1–PC8), 11 red cherry (RC1–RC11), 15 pink large-fruited (PL1–PL15), and 37 red large-fruited (RL1–RL8) tomato accessions. All of them are fresh market tomatoes rather than processing tomatoes. Seedling cultivation was conducted in a specialized seedling factory in January 2019. Tomato seedlings were then planted in a standardized research greenhouse in Yangling Zone (34°N, 108°E, 500 m altitude) of Shaanxi Province in March 2019. Tomatoes on the third inflorescence were picked when they reached the red ripe stage (i.e., mature tomato fruits with 90% surface coloring) (Shinozaki et al., 2018) from mid-June to early July 2019. Tomato samples were required to be in consistent size, have uniform coloring, and have no deformities, cleft fruit, or rot (Cheng et al., 2020).

TABLE 1.

Concentrations of taste compounds of mature tomato fruits.

| Class | Accession | Evolution type | Soluble solids (%) | Fructose (mg 100 g–1) | Glucose (mg 100 g–1) | Citric acid (mg 100 g–1) | Malic acid (mg 100 g–1) | Sugar and acid ratio |

| I | PL11 | Large-fruited | 6.03 | 1,290.00 | 838.50 | 251.33 | 144.17 | 5.38 |

| PC4 | Cherry | 8.17 | 1,801.20 | 1,023.15 | 451.92 | 266.03 | 3.93 | |

| PC2 | Cherry | 7.23 | 2,148.80 | 1,220.60 | 267.21 | 157.29 | 7.94 | |

| RL2 | Large-fruited | 4.77 | 1,376.67 | 840.00 | 332.82 | 235.60 | 3.90 | |

| PC8 | Cherry | 6.80 | 2,391.07 | 1,358.22 | 243.89 | 143.57 | 9.68 | |

| RL35 | Large-fruited | 5.23 | 1,465.17 | 894.00 | 178.67 | 126.48 | 7.73 | |

| RC6 | Cherry | 7.13 | 1,420.83 | 955.83 | 264.18 | 57.35 | 7.39 | |

| RC10 | Cherry | 9.63 | 2,145.00 | 1,443.00 | 461.72 | 100.23 | 6.38 | |

| PL13 | Large-fruited | 4.97 | 1,120.00 | 728.00 | 278.40 | 159.70 | 4.22 | |

| PC7 | Cherry | 7.07 | 1,716.93 | 975.28 | 347.91 | 204.80 | 4.87 | |

| II | RL33 | Large-fruited | 4.30 | 1,307.83 | 798.00 | 255.74 | 181.04 | 4.82 |

| RL19 | Large-fruited | 4.27 | 1,327.50 | 810.00 | 253.99 | 179.80 | 4.93 | |

| PL7 | Large-fruited | 4.37 | 1,100.00 | 715.00 | 344.13 | 197.40 | 3.35 | |

| PL9 | Large-fruited | 6.10 | 1,530.00 | 994.50 | 214.60 | 123.10 | 7.48 | |

| RC8 | Cherry | 5.53 | 1,475.83 | 992.83 | 359.38 | 78.02 | 5.64 | |

| PL4 | Large-fruited | 4.43 | 1,250.00 | 812.50 | 421.47 | 241.76 | 3.11 | |

| PC3 | Cherry | 8.67 | 2,096.13 | 1,190.68 | 451.92 | 266.03 | 4.58 | |

| RC9 | Cherry | 9.23 | 2,374.17 | 1,597.17 | 309.40 | 67.17 | 10.55 | |

| PC1 | Cherry | 7.17 | 2,085.60 | 1,184.70 | 310.25 | 182.63 | 6.64 | |

| RL20 | Large-fruited | 3.90 | 1,140.67 | 696.00 | 268.01 | 189.72 | 4.01 | |

| RL12 | Large-fruited | 6.30 | 1,288.17 | 786.00 | 280.27 | 198.40 | 4.33 | |

| RL36 | Large-fruited | 4.07 | 1,278.33 | 780.00 | 253.99 | 179.80 | 4.74 | |

| PC6 | Cherry | 11.43 | 2,401.60 | 1,364.20 | 243.89 | 143.57 | 9.72 | |

| RC1 | Cherry | 5.20 | 1,237.50 | 832.50 | 409.36 | 88.87 | 4.15 | |

| RL28 | Large-fruited | 5.37 | 1,602.83 | 978.00 | 544.77 | 385.64 | 2.77 | |

| RL26 | Large-fruited | 5.53 | 1,091.50 | 666.00 | 282.02 | 199.64 | 3.65 | |

| RC7 | Cherry | 9.97 | 2,090.00 | 1,406.00 | 264.18 | 57.35 | 10.87 | |

| PL6 | Large-fruited | 6.00 | 1,200.00 | 780.00 | 278.40 | 159.70 | 4.52 | |

| RC5 | Cherry | 6.80 | 1,714.17 | 1,153.17 | 390.32 | 84.73 | 6.04 | |

| RL8 | Large-fruited | 4.67 | 1,111.17 | 678.00 | 224.21 | 158.72 | 4.67 | |

| III | RL23 | Large-fruited | 6.10 | 1,091.50 | 666.00 | 210.20 | 148.80 | 4.90 |

| RC4 | Cherry | 7.03 | 1,815.00 | 1,221.00 | 514.08 | 111.60 | 4.85 | |

| RL25 | Large-fruited | 6.97 | 1,593.00 | 972.00 | 259.25 | 183.52 | 5.79 | |

| RL27 | Large-fruited | 5.93 | 1,396.33 | 852.00 | 120.87 | 85.56 | 10.89 | |

| RL37 | Large-fruited | 6.40 | 1,229.17 | 750.00 | 194.44 | 137.64 | 5.96 | |

| RL1 | Large-fruited | 5.03 | 1,337.33 | 816.00 | 201.44 | 142.60 | 6.26 | |

| PL2 | Large-fruited | 5.47 | 1,270.00 | 825.50 | 280.33 | 160.81 | 4.75 | |

| PL1 | Large-fruited | 6.37 | 1,560.00 | 1,014.00 | 320.93 | 184.09 | 5.10 | |

| RL3 | Large-fruited | 4.53 | 1,337.33 | 816.00 | 283.77 | 200.88 | 4.44 | |

| RL9 | Large-fruited | 5.63 | 1,307.83 | 798.00 | 218.96 | 155.00 | 5.63 | |

| RC2 | Cherry | 8.03 | 1,925.00 | 1,295.00 | 254.66 | 55.28 | 10.39 | |

| RL13 | Large-fruited | 6.23 | 1,317.67 | 804.00 | 252.24 | 178.56 | 4.92 | |

| RL31 | Large-fruited | 6.80 | 1,219.33 | 744.00 | 178.67 | 126.48 | 6.43 | |

| RL14 | Large-fruited | 4.43 | 1,071.83 | 654.00 | 197.94 | 140.12 | 5.11 | |

| PL12 | Large-fruited | 6.33 | 1,650.00 | 1072.50 | 286.13 | 164.13 | 6.05 | |

| PL3 | Large-fruited | 5.67 | 1,660.00 | 1,079.00 | 274.53 | 157.48 | 6.34 | |

| PL15 | Large-fruited | 5.67 | 1,440.00 | 936.00 | 351.87 | 201.84 | 4.29 | |

| RL16 | Large-fruited | 9.93 | 1,760.17 | 1,074.00 | 252.24 | 178.56 | 6.58 | |

| RL6 | Large-fruited | 5.30 | 1,032.50 | 630.00 | 234.72 | 166.16 | 4.15 | |

| RC11 | Cherry | 6.73 | 1,613.33 | 1,085.33 | 490.28 | 106.43 | 4.52 | |

| RL21 | Large-fruited | 5.73 | 1,671.67 | 1,020.00 | 436.17 | 308.76 | 3.61 | |

| PC5 | Cherry | 6.67 | 2,212.00 | 1,256.50 | 245.69 | 144.63 | 8.89 | |

| RL10 | Large-fruited | 3.67 | 1,121.00 | 684.00 | 196.19 | 138.88 | 5.39 | |

| PL5 | Large-fruited | 5.03 | 1,220.00 | 793.00 | 288.07 | 165.24 | 4.44 | |

| PL14 | Large-fruited | 3.83 | 1,470.00 | 955.50 | 264.87 | 151.93 | 5.82 | |

| RC3 | Cherry | 6.07 | 1,585.83 | 1066.83 | 323.68 | 70.27 | 6.73 | |

| PL8 | Large-fruited | 5.37 | 1,050.00 | 682.50 | 255.20 | 146.39 | 4.31 | |

| RL24 | Large-fruited | 6.10 | 1,091.50 | 666.00 | 199.69 | 141.36 | 5.15 | |

| IV | RL7 | Large-fruited | 4.27 | 1,366.83 | 834.00 | 199.69 | 141.36 | 6.45 |

| RL15 | Large-fruited | 6.07 | 1,268.50 | 774.00 | 183.93 | 130.20 | 6.50 | |

| RL4 | Large-fruited | 5.53 | 1,121.00 | 684.00 | 294.28 | 208.32 | 3.59 | |

| PL10 | Large-fruited | 6.67 | 1,850.00 | 1202.50 | 187.53 | 107.57 | 10.34 | |

| RL17 | Large-fruited | 4.40 | 1,081.67 | 660.00 | 215.46 | 152.52 | 4.73 | |

| RL22 | Large-fruited | 5.97 | 1,347.17 | 822.00 | 271.51 | 192.20 | 4.68 | |

| RL32 | Large-fruited | 5.63 | 1,396.33 | 852.00 | 301.29 | 213.28 | 4.37 | |

| RL5 | Large-fruited | 4.40 | 1,130.83 | 690.00 | 143.64 | 101.68 | 7.42 | |

| RL29 | Large-fruited | 5.17 | 1,248.83 | 762.00 | 196.19 | 138.88 | 6.00 | |

| RL11 | Large-fruited | 4.57 | 1,268.50 | 774.00 | 203.19 | 143.84 | 5.89 | |

| RL30 | Large-fruited | 6.50 | 1,150.50 | 702.00 | 206.70 | 146.32 | 5.25 | |

| RL18 | Large-fruited | 5.40 | 1,022.67 | 624.00 | 264.50 | 187.24 | 3.65 | |

| RL34 | Large-fruited | 4.97 | 914.50 | 558.00 | 262.75 | 186.00 | 3.28 |

PC, PL, RC, and RL indicated pink cherry tomato, pink large-fruited tomato, red cherry tomato, and red large-fruited tomato, respectively.

Experimental Methods

Soluble Solid

A small hole was made on the tomato, and a drop of tomato juice was squeezed out by hand and dropped on a PAL–1 digital refractometer (Atago Co., Ltd., Japan) to measure the concentration of soluble solid (Xu et al., 2018).

Soluble Sugars and Organic Acids

Fructose, glucose, citric acid, and malic acid concentrations were determined by HPLC (LC-2010A HT, Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Japan) with chromatographic column of C18 (Nucleodur 250 mm × 4.6 mm) (Acosta-Quezada et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017). The tomato fruits were crushed with a homogenizer (FJ200-SH, Specimen model factory, Shanghai, China). The non-polar metabolites of 0.001 kg sample were fractionated by 0.01 L chloroform. The polar metabolites were transferred into 0.05-L round bottom flask and dried under vacuum. Then, the sample was derivatized with methoxyamine hydrochloride and N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyltrifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) sequentially. After derivatization, the sample was filtrated twice by 0.22-μm microfiltration membrane for HPLC analysis. The citric acid and malic acid were also detected using an ultraviolet detector (VWD, Agilent Inc., United States). The mobile phase used to detect fructose and glucose was acetonitrile/water = 7:3 (v/v), and the mobile phase used to detect citric acid and malic acid was 0.2% metaphosphate. The flowrate was 1.67 × 10–5 L s–1. Column temperature was 35°C, and injection volume was 10–5 L.

Volatiles

Qualitative and quantitative analyses of volatile compounds were conducted using the headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) gas chromatography–olfactometry–mass spectrometry (GC-O-MS) method (Farneti et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019). Briefly, the samples were crushed with a homogenizer, and a 0.005-kg sample was added to 0.005 kg of anhydrous NaCl. The mix was vortexed to deactivate the tomato enzymes and filtered through a glass wool (Birtic et al., 2009). The supernatant was transferred to a 40-ml headspace bottle and added a magnetic rotor and 10–5 L of chromatographically pure 3.284 × 10–5 kg L–1 3-nonanone (Meryer Chemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were added. The volatile 3-nonanone was used as the internal standard because it is not found in tomato and is stable under normal temperature and pressure. The retention time (RT) of 3-nonanone appeared at 19.26 min. The RTs of volatiles in tomato appeared between 6.60 and 35.07 min. In the chromatogram, there are many volatiles peaks near to the peak of 3-nonanone, but the different peaks can be clearly distinguished. The recovery rate of 3-nonanone was as high as 98.423%. The headspace bottle containing the sample was placed on a magnetic stirrer (Troemner Inc., United States) for 2,400 s at 50°C. At the same time, the volatiles were extracted using an solid-phase microextraction (SPME) carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (CAR/PDMS) fiber assembly (Product ID: 57318, 7.5 × 10–5 m; particle size, 0.01 m length) (Supelco Inc., United States). The fiber assembly was used in conjunction with the manual injection handle 57330U. As the temperatures increases, the fiber coating begins to lose its ability to adsorb analytes. Although the SPME fiber can be used at least 50 times, we replaced it after 45 uses. The volatiles were detected using the GC-MS instrument (ISQ & TRACE ISQ) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., United States), which had a polar elastic quartz capillary chromatographic column HP-INNOWAX (0.25 mm i.d., 60 m length, 0.25 μm film thickness). In order to remove the residual solvents and volatiles from the filler and promote the uniform distribution and fixation of the liquid film on the filler surface, the SPME fiber and HP-INNOWAX column must be deactivated before extraction and detection of volatiles. The deactivation methods were as follows: the SPME fiber and HP-INNOWAX column were connected to the GC-MS instrument; the helium flowrate of carrier gas was 1.67 × 10–4 L s–1; the initial column temperature was 40°C, then increased to 230°C at a rate of 0.08°C s–1, and maintained for 7200 s.

The GC conditions used were as follows: inlet temperature of 230°C, over 99.999% helium carrier gas, no split injection, column flowrate of 1.67 × 10–5 L s–1, a split ratio of 20:1, and the splitless sample injection mode. The volatiles were desorbed for 150 s at 40°C. The column temperature was then increased to 110°C at a rate of 0.17°C s–1, increased to 230°C at a rate of 0.10°C s–1, and maintained for 600 s. The olfactory detector (OP275 Pro II, GL Sciences Inc., Japan) was connected at the outlet of the capillary column of GC, and the split ratio of MS and the olfactory detector was 1:1. The odor characteristics and intensities of detected volatiles were described and evaluated by five olfactory panelists at the outlet of the olfactometer (Majcher et al., 2020). The MS condition used as follows: ion source of EI, ion energy of 70 eV, full scan mode, scan range of 35–500 m z–1, ion source, and transmission line temperature of 230°C.

The RT of each normal alkane was measured after mixing the standard solutions of C4–C26 normal alkanes using GC-MS instrument. The retention index (RI) is known as the Kovats index, a parameter for the qualitative analysis of unknown compounds by gas chromatography (Matyushin et al., 2020). The RI of target volatile compound is calculated according to the RTs of the two normal alkanes adjacent to the target volatile compound (Matyushin et al., 2020). The RI of each volatile compound was calculated using the following equation (Chen et al., 2019):

| (1) |

where t′R is the RT, and Z and Z + 1 are the numbers of carbon atoms in the normal alkanes before and after the target volatiles (x) flow out, respectively. Note: t′R(z) < t′R(x) < t′R(z + 1).

The qualitative analyses of volatiles were compared with the standard mass spectrum of the library (NIST2011, United States) and RI (Selli et al., 2014). Volatiles were assessed using mass spectrometry (Chen et al., 2020; Pu et al., 2020), and only those with both positive and negative matches > 800 (maximum of 1,000) were selected. The peak area normalization method was used to calculate the relative concentration of the various volatiles (Topi, 2020), as follows:

| (2) |

where mn is the concentration (10–9 kg L–1) of the volatile compound (named “n”), Sn is the peak area of the volatile compound (named “n”), mt is the internal standard (3-nonanone) concentration (10–9 kg L–1), St is the internal standard peak area, and m0 is the mass (kg) of the sample. Since tomato fruits were found to comprise up to 94.52% water (Petro-Turza, 1987), the mass of 1 L tomato homogenate is about 1 kg.

Volatile compounds are partitioned differently in the headspace and have different affinities for the polymer on the SPME fiber (Chambers and Koppel, 2013); therefore, the calibration curves of key volatiles were essential for quantitative analysis using the GC-MS method (Li et al., 2019), i.e., the measured volatile concentrations required correction according to their calibration curves. In this study, 60 chromatographically pure standards of volatile compounds (Meryer, China Chemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were added to 0.005 kg water containing 10–5 L 3-nonanone (as the internal standard). The concentration gradient was formed by adding 0, 0.5 × 10–5, 1 × 10–5, 1.5 × 10–5, 2 × 10–5, 2.5 × 10–5, or 3 × 10–5 L standards, respectively. The compounds were measured under the same GC-MS conditions. Linear regression analysis was performed using the theoretical concentrations of volatile standards and the concentrations calculated by equation (1), as measured by GC-MS. The accurate concentration of each compound was calculated according to the corresponding calibration curve (Table 2) and Equation (2).

TABLE 2.

Concentrations of volatiles in mature tomato fruits (10–9 kg L–1).

| Volatile compound | Abbreviation | Calibration curvea | Regression coefficient | Retention time (RT) | WAX retention index (RI) | Descriptionb | Threshold concentrationc | Concentration range | Average | Variation coefficient | OAV |

| Alcohols | |||||||||||

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol | V1 | y = 0.125x - 6E-05 | 0.997 | 11.43 | 1,210 | Malty, solvent-like | 250 | 17.3–1,328.78 | 108.26 | 0.34 | <1 |

| 1-Pentan-3-ol | V2 | y = 0.322x - 0.342 | 0.995 | 12.16 | 1,256 | Green | 400 | 20.01–1,036.58 | 109.26 | 0.34 | <1 |

| 1-Nonanol | V3 | y = 1.678x - 0.032 | 0.994 | 9.21 | 1,079 | Roses, oranges, grease -like | 50,000 | 20.62–556.15 | 142.28 | 2.24 | <1 |

| 1-Hexanol | V4 | Y = 2.987x - 2E-4 | 0.995 | 19.09 | 1,650 | Resin, floral, green | 500 | 208.8–24,033.28 | 3,109.08 | 1.47 | 6 |

| (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol*d | V5 | y = 3.012x + 0.043 | 0.996 | 20.03 | 1,695 | Lettuce-like | 70 | 112.03–11,848.2 | 977.52 | 0.85 | 14 |

| (E)-2-Hexen-1-ol | V6 | y = 0.192x + 0.049 | 0.99 | 14.91 | 1,403 | Fruity | 3,900 | 24.74–1,303.4 | 239.72 | 1.19 | <1 |

| (2Z)-3,7-Dimethyl-2,6-octadien-1-ol | V7 | y = 0.386x - 0.302 | 0.998 | 21.99 | 1,807 | Rose-like | 49,000 | 41.7–395.92 | 84.32 | 1.50 | <1 |

| 2,4-Decadien-1-ol | V8 | y = 0.186x + 0.004 | 0.995 | 25.27 | 2,042 | Fatty, deep-fried | 2,300 | 30.62–943.17 | 183.84 | 1.34 | <1 |

| (E)-2-Octen-1-ol | V9 | y = 0.966x - 0.330 | 0.999 | 18.66 | 1,445 | Mushroom, earthy | 4,000 | 68.73–1,297.18 | 235.40 | 0.95 | <1 |

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-ol | V10 | y = 0.128x + 0.051 | 0.993 | 22.03 | 1,810 | Floral | 2,000,000 | 1.15–124.13 | 15.85 | 1.04 | <1 |

| 1-Octanol | V11 | y = 0.326x - 0.467 | 0.996 | 17.8 | 1,582 | Strong fatty citrus, rose-like | 22,000 | 18.67–251.23 | 65.94 | 1.14 | <1 |

| 2-Phenylethanol | V12 | y = 0.142x - 0.009 | 0.996 | 31.74 | 2,373 | Hyacinth, gardenia, nutty, fruity | 140,000 | 44.43–1,227.32 | 255.21 | 1.56 | <1 |

| 3,7-Dimethyl-6-octen-1-ol | V13 | y = 0.023x + 0.008 | 0.991 | 26.64 | 2,148 | Rose-like | 46,500 | 50.86–256.63 | 146.80 | 0.78 | <1 |

| (2E,6E,10E)-3,7,11,15-Tetramethyl-2,6,10,14-hexadecatetraen-1-ol | V14 | y = 0.765x - 0.232 | 0.991 | 24.46 | 1,982 | Rose-like | 50,000 | 2.3–16.52 | 7.15 | 1.48 | <1 |

| Aldehydes | |||||||||||

| Hexanal* | V15 | y = 2.433x - 0.561 | 0.997 | 11.48 | 1,213 | Green, grassy | 45 | 22.57–8,523.65 | 1,174.85 | 0.54 | 26 |

| (E)-2-Hexenal* | V16 | y = 1.39x + 0.004 | 0.992 | 14.96 | 1,406 | Green apple-like, bitter | 17 | 44.53–5,041.44 | 619.87 | 0.72 | 36 |

| Non-anal | V17 | y = 1.233x + 0.04 | 0.994 | 20.3 | 1,711 | Citrus-like, soapy | 28,000 | 15.89–397.18 | 124.18 | 1.20 | <1 |

| (E)-2-Octenal* | V18 | y = 2.18x + 0.043 | 0.997 | 21.4 | 1,773 | Mushroom, earthy | 30 | 45.11–3,790.96 | 450.97 | 1.55 | 15 |

| Decanal | V19 | y = 4.268x + 5E - 3 | 0.994 | 23.08 | 1,887 | Fatty, citrus-like, floral | 30 | 25.46–1,343.38 | 165.74 | 0.69 | 6 |

| (E)-2-Non-enal | V20 | y = 1.043x + 0.031 | 0.992 | 17.54 | 1,570 | Fatty, green | 190 | 15.89–397.18 | 124.18 | 1.15 | 1 |

| 2,6,6-Timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde* | V21 | y = 0.026x - 8E-4 | 0.991 | 22.11 | 1,816 | Mint, fruity | 5 | 26.95–461.14 | 110.06 | 1.05 | 22 |

| (Z)-3,7-Dimethyl-2,6-octadienal | V22 | y = 1.897x + 0.006 | 0.994 | 20.28 | 1,709 | Rose-like, citrus-like | 30 | 26.7–1,360.92 | 190.66 | 0.69 | 6 |

| (E)-3,7-Dimethyl-2,6-octadieal | V23 | y = 4.548x + 0.072 | 0.992 | 21.11 | 1,757 | Rose-like, citrus-like | 1,100 | 2.4–239.64 | 65.65 | 0.75 | <1 |

| (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal* | V24 | y = 2.041x - 0.033 | 0.99 | 29.28 | 2,278 | Fatty, deep-fried | 27 | 113.22–4,679.54 | 1,091.43 | 1.17 | 40 |

| (2E)-3-(3-Pentyl-2-oxiranyl)acrylaldehyde | V25 | Y = 0.038x - 0.309 | 0.998 | 25.84 | 2,086 | Metallic | 38 | 30.17–3,053.17 | 331.70 | 0.77 | 9 |

| (E)-2-Heptenal* | V26 | Y = 2.042x - 0.132 | 0.994 | 18.52 | 1,622 | Green | 13 | 20.92–1,219.46 | 195.73 | 0.78 | 15 |

| 5,9,13-Trimethyl-4,8,12-tetradecatrienal | V27 | y = 0.712x + 0.034 | 0.997 | 30.15 | 2,312 | –e | – | 21.67–326 | 83.61 | 1.28 | – |

| 2-Undecenal | V28 | y = 0.340x - 0.231 | 0.994 | 20.48 | 1,721 | Fatty, floral, citrus-like | 44,000 | 41.9–1,422.62 | 256.16 | 1.07 | <1 |

| (E,E)-2,4-Non-adienal | V29 | y = 1.901x + 0.092 | 0.991 | 20.65 | 1,731 | Fatty, green | 62 | 39.15–676.24 | 200.43 | 0.86 | 3 |

| (2E,6E)-3,7,11-Trimethyl-2,6,10-dodecatrienal | V30 | y = 0.977x - 0.423 | 0.998 | 29.92 | 2,303 | Soap-like, wax, violet, citrus-like | – | 29.53–437.26 | 87.28 | 0.84 | – |

| (E)-2-Decenal | V31 | y = 1.347x - 0.036 | 0.996 | 19.53 | 1,672 | Fatty | 17,000 | 18.5–888.61 | 235.18 | 0.80 | <1 |

| Ketones | |||||||||||

| 1-Penten-3-one | V32 | y = 2.096x + 0.003 | 0.992 | 9.77 | 1,113 | Fruity, floral, green | 940 | 17.14–221.37 | 71.28 | 0.89 | <1 |

| 3-Octanone | V33 | y = 1.129x - 0.332 | 0.995 | 12.44 | 1,272 | Green, wax, vegetable-like | 28,000 | 22.52–216.36 | 51.17 | 0.66 | <1 |

| 1-Octen-3-one | V34 | Y = 2.062x - 0.088 | 0.996 | 17.76 | 1,579 | Mushroom-like | 16 | 23.9–205.65 | 64.25 | 0.69 | 4 |

| 6,10-Dimethyl-2-undecanone, | V35 | Y = 0.488x + 0.055 | 0.993 | 20.13 | 1,701 | Wax, fruity, fatty | 7,000 | 25.78–622.93 | 107.76 | 0.81 | <1 |

| (E)-6,10-Dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one* | V36 | y = 0.142x + 5E-4 | 0.994 | 23.16 | 1,893 | Sweet, floral, ester-like | 60 | 14.63–8,821.9 | 1,096.97 | 0.60 | 18 |

| 4-(2,6,6-Trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-3-buten-2-one | V37 | y = 0.449x - 0.671 | 0.992 | 24.8 | 2,005 | Floral, violet-like | 3,500 | 4.05–321.43 | 67.08 | 1.27 | <1 |

| 1-(2,6,6-Trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-2-buten-1-one* | V38 | y = 2.190x + 0.038 | 0.993 | 26.51 | 2,138 | Baked apple, grape-like | 13 | 211.46–647.49 | 429.47 | 1.13 | 33 |

| (E,Z)-6,10-Dimethyl-3,5,9-undecatrien-2-one | V39 | y = 3.044x - 0.490 | 0.995 | 26.42 | 2,131 | Balsamic, violet-like | 800 | 3.62–131.1 | 34.99 | 0.94 | <1 |

| (E,E)-6,10,4-Trimethyl-5,9,13-pentadecatrien-2-one | V40 | Y = 0.099x - 0.344 | 0.999 | 31.53 | 2,365 | Fruity, floral | – | 10.47–4,869.49 | 548.04 | 0.72 | – |

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one* | V41 | Y = 1.432x - 0.043 | 0.99 | 18.82 | 1,637 | Fruity, floral | 50 | 29.84–11,923.39 | 1,376.41 | 0.77 | 28 |

| 6,10,14-Trimethyl-2-pentadecanone | V42 | y = 1.376x - 0.233 | 0.999 | 27.56 | 2,210 | Sweet, tea-like | 15,000 | 1.99–42.93 | 8.80 | 1.15 | <1 |

| Esters | |||||||||||

| 2-Hydroxy-ethyl benzoate | V43 | y = 0.877x - 9E-5 | 0.991 | 22.74 | 1,862 | Herbs, sweet, spicy | 900 | 45.1–6,378.2 | 1,225.83 | 1.34 | 1 |

| Ethyl tetradecanate | V44 | Y = 0.423x - 0.491 | 0.994 | 26.25 | 2,118 | – | 4,000,000 | 24.29–193.35 | 62.62 | 1.01 | <1 |

| Methyl hexadecanoate | V45 | Y = 0.203x - 0.509 | 0.992 | 28.92 | 2,264 | – | 2,000,000 | 16.02–693.12 | 188.92 | 1.11 | <1 |

| Ethyl hexadecanoate | V46 | y = 1.047x + 0,007 | 0.992 | 29.45 | 2,285 | – | 2,000,000 | 41–2,266.54 | 566.09 | 0.70 | <1 |

| Dimethyl phthalate | V47 | y = 0.049x - 0.132 | 0.997 | 30.63 | 2,331 | Light fragrance | – | 22.97–305.44 | 63.94 | 0.82 | – |

| Ethyl (9Z,12Z)-9,12-octadecadienoate | V48 | y = 0.183x - 0.386 | 0.994 | 34.46 | 2,488 | – | – | 22.23–191.42 | 61.25 | 0.77 | – |

| Hept-4-yl-isobutyl phthalate | V49 | y = 0.345x + 0.057 | 0.998 | 35.07 | 2,516 | Light fragrance | – | 27.78–853.24 | 191.16 | 1.05 | – |

| Ethyl octanoate | V50 | y = 0.122x - 0.377 | 0.991 | 15.48 | 1,439 | Pears litchi-like, sweet | 13 | 28.94–180.99 | 71.64 | 0.65 | 6 |

| Methyl salicylate* | V51 | y = 0.071x + 0.003 | 0.994 | 29.71 | 2,295 | Wintergreen, herbal | 40 | 23.77–1,936.87 | 469.46 | 0.89 | 12 |

| Ethyl acetate | V52 | y = 4.823x - 0.061 | 0.999 | 6.61 | 942 | Fruity | 50,000 | 24.75–1,239.48 | 185.22 | 0.43 | <1 |

| Isopropyl palmitate | V53 | y = 1.990x - 0.223 | 0.99 | 29.74 | 2,296 | – | – | 30.52–2,662 | 264.65 | 1.08 | – |

| Phenols | |||||||||||

| 2,4-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-phenol | V54 | y = 0.055x - 0.367 | 0.995 | 30.39 | 2,321 | Smoky, sweet | 500,000 | 31.89–497.59 | 101.47 | 1.53 | <1 |

| 4-Allyl-2-methoxyphenol* | V55 | y = 0.032x + 0.001 | 0.997 | 28.52 | 2,249 | Lilac, cinnamon, cantaloupe-like | 20 | 34.31–1,752.73 | 330.04 | 2.51 | 17 |

| 2-Methoxyphenol | V56 | y = 0.422x - 0.542 | 0.994 | 30.96 | 2,344 | Smoky, sweet, woody, herbal | 840 | 63.47–250.61 | 154.64 | 1.03 | <1 |

| Other volatiles | |||||||||||

| Alanylglycine | V57 | y = 0.058x - 0.399 | 0.998 | 3.84 | 487 | Chicken-like | – | 39.68–840.72 | 162.79 | 1.07 | – |

| 2-Pentyl-furan | V58 | y = 1.099x + 0.383 | 0.99 | 14.93 | 1,404 | Earthy, vegetable, malty, ham-like | 6,000 | 42.09–1,157.35 | 301.08 | 0.60 | <1 |

| 2-Isobutylthiazole* | V59 | y = 1.049x + 0.097 | 0.996 | 20.74 | 1,736 | Tomato vine, green | 3.5 | 3.53–574.12 | 80.01 | 0.97 | 23 |

| 3-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-furan | V60 | y = 0.328x - 0.539 | 0.994 | 15.32 | 1,429 | Minty | – | 21.95–201.22 | 63.22 | 0.73 | – |

aIn the calibration curve (y = kx + b), “y” represents the theoretical concentration of the labeled standard, and “x” represents the peak area ratio of a compound in the internal standard. bOdor descriptions of volatiles come from the olfactory panelists and refer to the literature (Du et al., 2015; Kreissl and Schieberle, 2017; Zhu Y. et al., 2018). cOdor thresholds of volatiles determined in water (10–9 kg L–1), reference to the literature (Kreissl and Schieberle, 2017; Zhu Y. et al., 2018). dVolatiles that could be detected by an artificial olfactory system, as indicated by “∗” next to the compound name. e“–” indicates the absence of data.

Sensory Evaluation

Sensory evaluations of sweetness, sourness, characteristic flavor, and overall acceptability were conducted according to published methods (Tieman et al., 2012; Vallverdu-Queralt et al., 2013; Aisala et al., 2020), with slight modification. Briefly, different tomato accessions were numbered and cut into wedges (Cortina et al., 2018). After 7 days of training in the College of Food Science and Engineering, Northwest A&F University, the taste panels (25 male and 25 female, aged 18–60 years old) had mastered the taste evaluation methods (Tieman et al., 2012). Then, they conducted the sensory evaluations of 71 tomato accessions. To reduce the influence of visual preference on sensory evaluation, the sensory evaluators wore eye masks throughout the process. The maximum score was tentatively set at 8.00 points (Zhang K. et al., 2019). The taste panels scored the sweetness, sourness, characteristic flavor, and overall acceptability according to the taste intensity, e.g., the stronger the taste, the higher the score. After tasting each sample, the panels rinsed their mouths three times with purified water. To reduce taste fatigue, the panels conducted evaluations for 2,700-s periods (evaluate four to six tomato samples) and then took breaks of 900 s.

DTOPSIS Analysis

DTOPSIS analysis (Zhao et al., 2012) was used to evaluate the flavor of each tomato accession according to the following formula:

| (3) |

where Si+ is the distance from the desirable flavor (X+j), Si– is the distance from the undesirable flavor (X–j), and Ci is the closeness to the ideal fruit flavor.

Statistical Analysis

All test data were recorded using WPS Office 2019. The standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of the 71 tomato accessions were calculated using SPSS 22.0 (Zhang Y. et al., 2019). At least three biological replicates were performed for all flavor factors for each sample. The Z-score was used to standardize the data of tomato taste compounds, volatiles concentrations, and sensory evaluation scores (Ronningen et al., 2018). The significant differences in flavor among PC, PL, RC, and RL accessions were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA using SPSS 22.0. Pearson’s correlation of flavor compounds and sensory evaluation was analyzed using SPSS 22.0. The heatmap plots were prepared using the Heatmapper software1 (Sasha et al., 2016).

Results

Analysis of the Taste Compounds of Mature Tomato Fruits

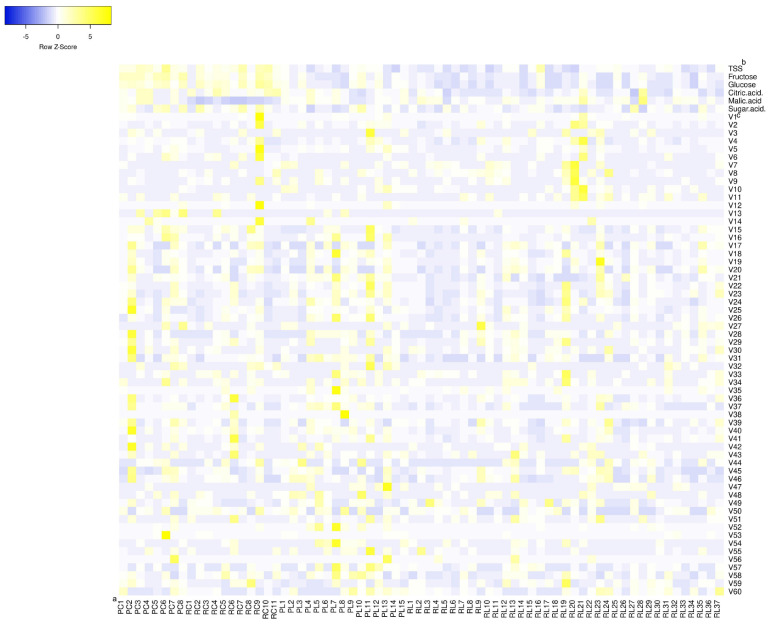

The concentrations of taste compounds from the 71 tomato accessions are shown in Table 1, Supplementary Table S1, and Figure 1. The soluble solids, fructose, glucose, citric acid concentrations, and the sugar and acid ratio in cherry tomatoes were significantly higher than that in large-fruited tomatoes. RC had the lowest malic acid concentration. The soluble solids consisted mainly of fructose, glucose, citric acid, and malic acid. The concentration of fructose was higher (by 1.61-fold) than that of glucose, and the concentration of citric acid was higher (by 1.77-fold) than that of malic acid. Among the 71 tomato accessions, the concentration of soluble solids was higher in accessions PC6, RL16, RC7, RC10, and RC9 and ranged from 3.67 to 11.43%. Fructose concentrations ranged from 910 to 2,400 mg 100 g–1 and were highest in accessions PC6, PC8, RC9, PC5, and PC2. Glucose concentrations ranged from 560 to 1,600 mg 100 g–1 and were highest in accessions RC9, RC10, RC7, PC8, and PC6. Citric acid concentrations ranged from 120 to 540 mg 100 g–1 and were highest in accessions RL28, RC4, RC11, and RC10. Malic acid concentrations ranged from 60 to 390 mg 100 g–1 and were highest in accessions RL28, RC4, RC11, and PC4. The sugar and acid ratios ranged from 2.77 to 10.89, and accessions RL27, RC7, RC9, RC2, and PL10 had the highest ratios (above 10.00). Accessions RC9, PC6, RC7, and RC10 had the highest concentrations of taste compounds.

FIGURE 1.

Heat map of concentrations of flavor compounds in mature tomato fruits. aPC, PL, RC, and RL indicate pink cherry tomato, pink large-fruited tomato, red cherry tomato, and red large-fruited tomato, respectively. bTSS represents the total soluble solids. cV1–V60 represents the volatiles from top to bottom in Table 2, respectively.

Analysis of the Volatiles in Mature Tomato Fruits

A total of 60 volatiles were detected in this study (Table 2 and Figure 1). The concentrations of the total volatiles ranged from 3.67 to 53.37 × 10–6 kg L–1 (mean: 15.54 × 10–6 kg L–1). Accessions PL11, RC9, RC6, PC2, and RL21 had the highest total volatile concentrations. Classified by functional groups (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S2), there were 17 aldehydes, 14 alcohols, 11 ketones, 11 esters, 3 phenols, and 4 other volatiles detected, at concentrations of 5.51 × 10–6, 5.68 × 10–6, 3.73 × 10–6, 3.35 × 10–6, 4.85 × 10–7, and 6.07 × 10–7 kg L–1, respectively. Phenols were detected in only 28 of the 71 tomato accessions. Classified by metabolic precursors (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S3), there were 31 lipid-derived, 17 carotenoid-derived, 8 Phe-derived, and 5 Ile/Leu-derived volatiles detected, at concentrations of 1.03 × 10–5, 3.56 × 10–6, 1.43 × 10–6, and 5.59 × 10–7 kg L–1, respectively. Phe-derived volatiles were not detected in accession RC7. The common volatiles in the 71 accessions were 1-hexanol, (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol, hexanal, (E)-2-octenal, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, (E,E)-6,10,4-trimethyl-5,9,13-pentadecatrien-2-one, and (E,E)-2,4-decadienal. The average concentration of each volatile in the 71 accessions was 2.59 × 10–7 kg L–1. The most abundant volatiles were 1-hexanol (mean: 3.11 × 10–6 kg L–1), 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, 2-hydroxy-ethyl benzoate, hexanal, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol, and (E)-2-hexenal (mean: 6.20 × 10–7 kg L–1), which were mainly derived from lipids and carotenoids.

TABLE 3.

Components and concentrations (10–9 kg L–1) of different groups of volatiles.

| Component | Concentration | Range | Variation coefficient | Higher concentration accessions | |

| Functional group | |||||

| Alcohols | 14 | 5,680.64 | 725.92–33,381.73 | 0.96 | RC9, RL21, RL20, PL11, RL23 |

| Aldehydes | 17 | 5,507.68 | 710.70–22,161.77 | 0.74 | PL11, PC2, PL7, RL19, PC6 |

| Ketones | 11 | 3,733.78 | 25.11–22,766.87 | 0.88 | RC6, PC2, PL11, RL19, RL37 |

| Esters | 11 | 3,350.78 | 166.77–9,779.93 | 0.58 | RL13, RC6, PC2, RL23, PL13 |

| Phenols | 3 | 484.69 | 0–1,752.73 | 0.58 | PL11, RL2, PC7, PL13, PC4 |

| Other volatiles | 4 | 607.1 | 139.59–2,202.85 | 0.60 | PL7, PL11, PL19, PL10, RC8 |

| Metabolic precursor | |||||

| Lipid-derived | 31 | 10,277.77 | 1,833.26–40,720.26 | 0.74 | RC9, RL11, RL21, PC2, PC6 |

| Carotenoid-derived | 17 | 3,557.60 | 25.11–23,571.42 | 0.99 | RC6, PC2, PL11, RL19, RL37 |

| Phe-derived | 8 | 1,427.94 | 0–8,860.50 | 1.23 | RC6, PL13, RL23, PL11, PL13 |

| Ile/Leu-derived | 4 | 559.44 | 50.65–2,790.32 | 0.94 | PL8, PL7, RC9, RC10, RL12 |

Only 1-hexanol in accessions RL21, RC9, RL20, PL11, (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol in accession RC9, and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one in accession RC6 were detected in concentrations higher than 10–5 kg L–1. The concentrations of volatiles, such as hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, 2,6,6-timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, (E)-2-decenal, 4-(2,6,6-trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-3-buten-2-one, (E,E)-6,10,4-trimethyl-5,9,13-pentadecatrien-2-one, ethyl (9Z,12Z)-9,12-octadecadienoate, and methyl hexadecanoate, were significantly higher in pink tomatoes than in red tomatoes. In addition, the concentrations of (2E,6E)-3,7,11-trimethyl-2,6,10-dodecatrienal, (E,Z)-6,10-dimethyl-3,5,9-undecatrien-2-one, and isopropyl palmitate were highest in PCs, and the concentrations of 1-nonanol, alanylglycine, and 2-pentyl-furan were the highest in pink PLs. Most volatiles were found in their lowest concentrations in RLs.

Flavor Evaluation of Mature Tomato Fruits

Sensory Evaluation

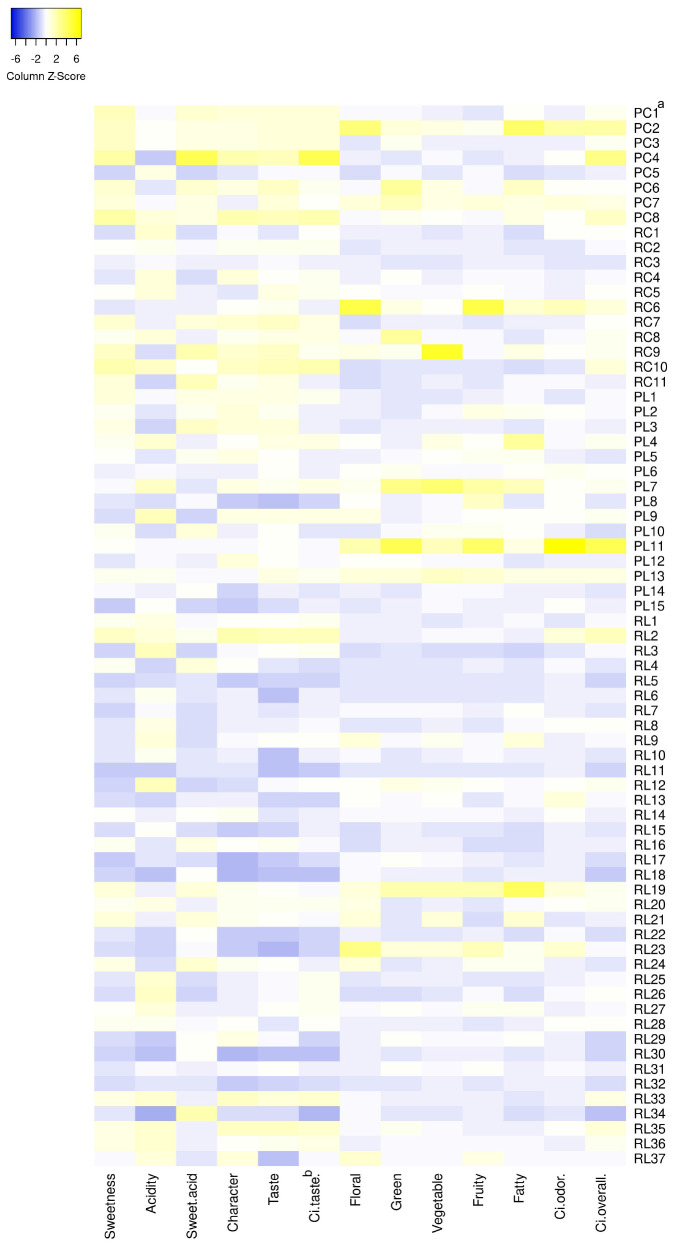

The sensory evaluation scores are shown in Supplementary Table S4 and Figure 2. The taste factors included sweetness, sourness, the sweetness and sourness ratio, characteristic flavor, and overall acceptability. Sweetness, sweetness and sourness ratio, characteristic flavor, and overall acceptability were the strongest in PCs and the weakest in PLs. The sweetness scores ranged from 2.00 to 8.00 (mean ± CV: 4.33 ± 0.35) and were higher for accessions PC8, PC4, and RC10. The sourness scores ranged from 1.50 to 6.00 (4.13 ± 1.10) and were lower for accessions RL34, RL30, RL18, and PC4. The sweetness and sourness ratios ranged from 0.44 to 3.56 (1.16 ± 0.47) and were higher for accessions PC4, RC9, and RL34. The characteristic flavor scores ranged from 2.00 to 7.75 (5.00 ± 0.28) and were higher for accessions PC4, PC8, and RL2. The overall acceptability scores ranged from 1.75 to 8.00 (4.97 ± 0.33) and were higher for accessions PC4, PC8, RC10, and RL2. Accession PC4 had a high sweetness and sourness ratio and high characteristic flavor and overall acceptability scores. Accessions PC8, RC10, and RL2 had high characteristic flavor and overall acceptability scores.

FIGURE 2.

Heat map of the sensory evaluations of taste and odor characteristics of 71 tomato accessions. aPC, PL, RC, and RL indicate pink cherry tomato, pink large-fruited tomato, red cherry tomato, and red large-fruited tomato, respectively. bCi values represent the scores of the DTOPSIS analysis.

Odor intensity can be quantified according to the ratio of the concentration to the olfactory threshold and is termed the “odor activity value” (OAV) (Buttery, 1993). In this study, the OAVs of 22 volatiles were >1 (Table 2), indicating that they had important impacts on flavor. Such volatiles are called odor-impact compounds (Baldwin et al., 2000). Of the 60 volatiles, 13 could be detected by an artificial olfactory system (as indicated by asterisk next to the compound names in Table 2). The volatiles that were found to contribute more to tomato flavor were (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, (E)-2-hexenal, 1-(2,6,6-trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-2-buten-1-one, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, hexanal, 2-isobutylthiazole, 2,6,6-timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, 4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol, (E)-2-heptenal, (E)-2-octenal, (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol, and methyl salicylate. The highest OAV was reported for accession PL11 (OAV = 1,196), and the lowest OAV was reported for accession RL26 (OAV = 79). The components of the odor-impact compounds ranged from 8 (accession RL26) to 21 (accession PL8).

According to the characteristic description, the volatile odors could be divided into green, floral, fruity, vegetable, fatty, and irritant odors. The intensities of green and fatty odors were the strongest in PCs, and the weakest in PLs. The OAVs of green odor ranged from 11 to 574 (mean ± CV: 98 ± 1.35) and were the highest for accessions PL11, PL7, and PC6. The OAVs of floral odor ranged from 5 to 175 (36 ± 0.82) and were the highest for accessions RC6, PC2, and RL23. The OAVs of fruity odor ranged from 4 to 258 (51 ± 0.88) and were the highest for accessions RC6, PL11, and PL7. Accessions RL19 and PL7 had stronger green, vegetable, and fruity odors. The OAVs of fatty odor ranged from 4 to 184 (42 ± 0.79) and were the highest for accessions RL19, PC2, and PL4. The OAVs of vegetable odor ranged from 6 to 194 (31 ± 0.96) and were the highest for accessions RC9, PL7, and RL19. The OAVs of irritant odor were lower than 153 (22 ± 1.14). No irritation odors were detected in accessions PC8, PL3, RL26, and RL31. “Irritant odors” represent the disliked odors and were mainly attributed to 2-hydroxy-ethyl benzoate (herbs, sweet, spicy), methyl salicylate (wintergreen, herbal), 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-phenol (smoky, sweet), 4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol (lilac, cinnamon, cantaloupe-like), and 2-methoxyphenol (smoky, sweet, woody, herbal).

DTOPSIS Analysis

The DTOPSIS analysis method was used to evaluate the flavors of the different tomato accessions (Supplementary Table S4 and Figure 2). Among all the sensory factors, the sourness and irritant odor were negative indicators of flavor, while the others were positive factors. To rank accessions according to taste and odor factors, each sensory factor was simplified as a unique score (Cortina et al., 2018). The scores and rankings of the tomato flavor evaluation [i.e., results from Equation (3)] are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The taste evaluation [Ci(taste)], odor evaluation [Ci(odor)], and comprehensive flavor evaluation [Ci(overall)] values were -2.05–4.45, -0.64–6.85, and -2.69–6.70, respectively. The 71 tomato accessions can be divided into four classes according to [Ci(overall)] from high to low, contains 10, 20, 28, and 13 tomato accessions, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S4). Of the 71 tomato accessions assessed, the flavor scores were higher in accessions PL11, PC4, PC2, PC8, RL35, RC6, and RC10; among these, accessions PC4, PC8, RC10, RL2, and RL35 had better tomato taste, and accessions PL11, PC2, and RC6 had better tomato odor. The intensities of the green and fatty odors were the strongest in PCs and the weakest in PLs. The [Ci(taste)] and [Ci(overall)] values were significantly higher in PCs than in the other types of tomatoes.

Correlation Analyses of Key Flavor Factors in Mature Tomato Fruits

The results of the Pearson’s correlation analyses between compound concentrations and flavor intensities are shown in Table 4. The [Ci(overall)] values were significantly positively (P < 0.05) correlated with the concentrations of glucose, citric acid, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, and (E,Z)-6,10-dimethyl-3,5,9-undecatrien-2-one. Furthermore, the [Ci(overall)] values were very significantly positively (P < 0.01) correlated with fructose, 1-nonanol, hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-octenal, (E)-2-heptenal, 2-undecenal, (E,E)-2,4-nonadienal, (E)-2-decenal, 1-penten-3-one, 2,6,6-timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, (Z)-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadienal, (E)-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadieal, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, (2E)-3-(3-pentyl-2-oxiranyl) acrylaldehyde, 4-(2,6,6-trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-3-buten-2-one, (E,E)-6,10,4-trimethyl-5,9,13-pentadecatrien-2-one, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, methyl salicylate, and 4-allyl-2-ethoxyphenol, i.e., mainly aldehydes. The [Ci(overall)] values were also very significantly positively correlated with sweetness, sourness, characteristic flavor, overall acceptability, floral, fruity, fatty, green, and irritation odors. The soluble solids, fructose, glucose, and citric acid were significantly positively correlated with the [Ci(taste)] values, sweetness, sweetness and sourness ratio, characteristic flavor, and overall acceptability. Many volatiles were significantly positively correlated with the [Ci(odor)] values, fatty, green, floral and fruity, vegetable, and irritant odors. According to metabolic precursors, the carotenoid-derived volatiles were significantly positively correlated with the floral and fruity odors; the lipid-derived volatiles were significantly positively correlated with the green, floral, and fruity odors; the Ile/Leu-derived volatiles were significantly positively correlated with the green and vegetable odors; and the Phe-derived volatiles were significantly positively correlated with the irritant odor.

TABLE 4.

Correlations between flavor compounds and sensory evaluations in mature tomato fruits.

| C | Ci(taste) | Ci(odor) | Sweetness | Sweetness/sourness | Characteristic flavor | overall acceptability | Floral | Green | Vegetable | Fruity | Fatty | Irritation | |

| Soluble solids | 0.219 | 0.295* | 0.023 | 0.437**b | 0.406** | 0.301*c | 0.445** | 0.016 | 0.136 | 0.121 | −0.053 | 0.004 | 0.021 |

| Fructose | 0.313** | 0.495** | −0.040 | 0.593** | 0.365** | 0.491** | 0.643** | −0.045 | 0.119 | 0.170 | −0.152 | 0.159 | −0.067 |

| Glucose | 0.283* | 0.457** | −0.045 | 0.556** | 0.332** | 0.489** | 0.649** | −0.047 | 0.098 | 0.204 | −0.118 | 0.120 | −0.073 |

| Citric acid | 0.248* | 0.377** | −0.016 | 0.363** | 0.248* | 0.290* | 0.339** | −0.098 | −0.024 | 0.052 | −0.113 | 0.036 | 0.011 |

| Sugar/acid | 0.059 | 0.135 | −0.050 | 0.214 | 0.096 | 0.216 | 0.338** | 0.038 | 0.108 | 0.132 | 0.011 | 0.083 | −0.085 |

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol | 0.050 | 0.081 | −0.009 | 0.229 | 0.273* | 0.169 | 0.194 | 0.130 | 0.028 | 0.687** | −0.046 | 0.125 | 0.012 |

| 1-Nonanol | 0.393** | −0.128 | 0.700** | −0.002 | 0.042 | −0.128 | −0.073 | 0.294* | 0.498** | 0.187 | 0.442** | 0.244* | 0.573** |

| 1-Hexanol | 0.226 | 0.075 | 0.254* | 0.173 | 0.152 | 0.112 | 0.125 | 0.416** | 0.210 | 0.512** | 0.137 | 0.225 | 0.214 |

| (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol | 0.193 | 0.093 | 0.187 | 0.260* | 0.310** | 0.140 | 0.218 | 0.259* | 0.228 | 0.790** | 0.132 | 0.203 | 0.179 |

| (E)-2-Hexen-1-ol | 0.035 | 0.077 | −0.026 | 0.284* | 0.311** | 0.201 | 0.255* | 0.160 | 0.112 | 0.639** | −0.052 | 0.238* | −0.033 |

| 2-Phenylethanol | 0.096 | 0.104 | 0.035 | 0.232 | 0.243* | 0.157 | 0.209 | 0.151 | 0.070 | 0.682** | 0.010 | 0.114 | 0.049 |

| Hexanal | 0.551** | 0.153 | 0.648** | 0.155 | −0.020 | 0.109 | 0.228 | 0.396** | 0.877** | 0.379** | 0.508** | 0.308** | 0.516** |

| (E)-2-Hexenal | 0.479** | 0.065 | 0.631** | 0.129 | 0.044 | 0.086 | 0.209 | 0.376** | 0.893** | 0.577** | 0.619** | 0.348** | 0.496** |

| (E)-2-Octenal | 0.307** | 0.087 | 0.359** | 0.087 | −0.010 | 0.125 | 0.133 | 0.426** | 0.682** | 0.697** | 0.596** | 0.699** | 0.302* |

| Decanal | 0.155 | −0.057 | 0.282* | 0.004 | −0.008 | −0.127 | −0.096 | 0.521** | 0.245* | 0.226 | 0.217 | 0.210 | 0.329** |

| 2,6,6-Timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde | 0.361** | 0.097 | 0.427** | 0.022 | −0.103 | 0.030 | 0.109 | 0.322** | 0.587** | 0.440** | 0.506** | 0.312** | 0.322** |

| (Z)-3,7-Dimethyl-2,6-octadienal | 0.495** | −0.045 | 0.765** | 0.062 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.648** | 0.724** | 0.493** | 0.839** | 0.576** | 0.655** |

| (E)-3,7-Dimethyl-2,6-octadieal | 0.380** | −0.064 | 0.615** | 0.048 | 0.023 | 0.019 | −0.035 | 0.723** | 0.628** | 0.481** | 0.788** | 0.621** | 0.563** |

| (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal | 0.360** | 0.177 | 0.346** | 0.350** | 0.195 | 0.247* | 0.302* | 0.582** | 0.475** | 0.591** | 0.472** | 0.998** | 0.356** |

| (2E)-3-(3-Pentyl-2-oxiranyl)acrylaldehyde | 0.405** | 0.154 | 0.434** | 0.208 | 0.119 | 0.101 | 0.154 | 0.481** | 0.385** | 0.381** | 0.263* | 0.655** | 0.494** |

| (E)-2-Heptenal | 0.452** | 0.056 | 0.600** | 0.032 | −0.065 | 0.063 | 0.088 | 0.481** | 0.810** | 0.674** | 0.692** | 0.601** | 0.487** |

| 2-Undecenal | 0.336** | 0.114 | 0.374** | 0.080 | −0.012 | 0.093 | 0.083 | 0.427** | 0.280* | 0.295* | 0.177 | 0.573** | 0.435** |

| (E,E)-2,4-Nonadienal | 0.483** | 0.098 | 0.603** | 0.111 | 0.017 | 0.112 | 0.123 | 0.605** | 0.460** | 0.378** | 0.546** | 0.731** | 0.590** |

| (2E,6E)-3,7,11-Trimethyl-2,6,10-dodecatrienal | 0.217 | 0.102 | 0.214 | 0.212 | 0.184 | 0.085 | 0.029 | 0.400** | 0.040 | 0.142 | 0.067 | 0.345** | 0.349** |

| (E)-2-Decenal | 0.483** | 0.180 | 0.521** | 0.251* | 0.101 | 0.214 | 0.257* | 0.420** | 0.494** | 0.381** | 0.401** | 0.596** | 0.530** |

| 1-Penten-3-one | 0.433** | 0.035 | 0.595** | 0.188 | 0.134 | −0.016 | 0.147 | 0.184 | 0.533** | 0.359** | 0.382** | 0.059 | 0.437** |

| 1-Octen-3-one | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.150 | 0.089 | 0.094 | 0.095 | 0.030 | 0.309** | 0.287* | 0.132 | 0.390** | −0.019 |

| (E)-6,10-Dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one | 0.297* | −0.002 | 0.432** | 0.014 | −0.014 | 0.047 | 0.023 | 0.889** | 0.239* | 0.197 | 0.658** | 0.501** | 0.552** |

| 4-(2,6,6-Trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-3-buten-2-one | 0.340** | 0.128 | 0.366** | 0.140 | 0.039 | 0.069 | 0.190 | 0.408** | 0.493** | 0.544** | 0.464** | 0.623** | 0.356** |

| 1-(2,6,6-Trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-2-buten-1-one | −0.035 | −0.143 | 0.093 | −0.103 | −0.032 | −0.161 | −0.176 | 0.184 | −0.031 | 0.005 | 0.337** | −0.028 | 0.149 |

| (E,Z)-6,10-Dimethyl-3,5,9-undecatrien-2-one | 0.248* | 0.038 | 0.320** | 0.150 | 0.109 | 0.131 | 0.089 | 0.588** | 0.254* | 0.213 | 0.374** | 0.588** | 0.361** |

| (E,E)-6,10,4-Trimethyl-5,9,13-pentadecatrien-2-one | 0.372** | 0.143 | 0.398** | 0.190 | 0.103 | 0.122 | 0.158 | 0.688** | 0.223 | 0.249* | 0.365** | 0.628** | 0.519** |

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 0.385** | −0.078 | 0.637** | −0.006 | −0.021 | 0.019 | 0.017 | 0.745** | 0.544** | 0.342** | 0.914** | 0.461** | 0.595** |

| 6,10,14-Trimethyl-2-pentadecanone | 0.225 | 0.097 | 0.229 | 0.254* | 0.241* | 0.166 | 0.184 | 0.393** | 0.088 | 0.142 | 0.118 | 0.457** | 0.307** |

| Methyl salicylate | 0.345** | −0.182 | 0.683** | −0.132 | −0.105 | −0.166 | −0.231 | 0.642** | 0.316** | 0.124 | 0.569** | 0.156 | 0.763** |

| 4-Allyl-2-methoxyphenol | 0.634** | 0.140 | 0.781** | 0.113 | 0.091 | 0.107 | 0.154 | 0.269* | 0.372** | 0.116 | 0.447** | 0.032 | 0.764** |

| 2-Pentyl-furan | 0.191 | 0.087 | 0.191 | 0.098 | 0.007 | 0.181 | 0.220 | 0.186 | 0.453** | 0.443** | 0.368** | 0.491** | 0.125 |

| 2-Isobutylthiazole | 0.143 | 0.093 | 0.113 | 0.118 | −0.011 | 0.081 | 0.138 | 0.238* | 0.529** | 0.262* | 0.291* | 0.457** | 0.094 |

| 3-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-furan | 0.085 | −0.148 | 0.272* | −0.077 | −0.069 | −0.047 | −0.205 | 0.239* | 0.176 | 0.018 | 0.345** | 0.050 | 0.210 |

aCi values represent the scores of the DTOPSIS analysis. b** means a very significant correlation (P < 0.01). c* means significant correlation (P < 0.05).

There was no significant correlation between taste compounds and odor characteristics, but some volatiles showed significant positive correlations with the taste evaluations. The overall acceptability was significantly positively correlated with (E)-2-hexen-1-ol and (E)-2-decenal. The characteristic flavor was significantly positively correlated with (E,E)-2,4-decadienal. The sweetness and sourness ratio were significantly positively correlated with 3-methyl-1-butanol, 2-phenylethanol, and ethyl tetradecanoate. Sweetness was significantly positively correlated with (E,E)-2,4-decadienal.

Discussion

Flavor involves both taste and odor and is perceived by the binding of taste compounds and volatiles to sensory receptors. The human taste system can detect five to seven tastes (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, hemp, umami, and koukumi) and the olfactory system can detect thousands of odors. Sweetness and sourness were the basis of tomato flavor (Baldwin et al., 2008; D’angelo et al., 2018). In a previous study, tomato fruits were found to comprise up to 94.52% water, in addition to fructose, glucose, citric acid, and malic acid concentrations accounting for 25, 22, 9, and 4% of the dry weight of tomato, respectively (Petro-Turza, 1987). In addition, this previous study reported the concentrations of fructose, glucose, citric acid, and malic acid in fresh tomato fruits to be 1,370, 1,205.6, 493.2, and 219.2 mg 100 g–1, respectively. Another previous study reported consistent values, i.e., fructose and glucose concentrations of 1,370 and 1,250 mg 100 g–1, respectively (United States Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2011). The concentrations of fructose, glucose, citric acid, and malic acid in tomato genotype “Fla.8153” were 1.20, 1.11, 0.31, and 0.04%, while they were 0.99, 0.96, 0.34, and 0.07% in tomato genotype “Florida 47,” respectively. In the present study, we reported fructose, glucose, citric acid, and malic acid concentrations of 1,464.36, 911.72, 281.50, and 158.81 mg 100 g–1, respectively (Baldwin et al., 2015). Compared to the wild-type Solanum pimpinellifolium (Çolaka et al., 2020), tomato fruits in this study have lower glucose and fructose (decreased by 75%) and higher malic acid and citric acid (by 40-fold). The decreased sugar and increased malic acid concentrations, and resulting higher sourness, are prominent issues in modern tomato fruits.

The sweetness of tomato fruits are mainly attributed to their fructose and glucose concentrations. The (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, ethyl octanoate, and 2-hydroxy-ethyl benzoate volatiles were perceived to be sweet. Baldwin et al. (1998) also found that sweetness was closely correlated with glucose, fructose, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, hexanal, (Z)-3-hexenal, (E)-2-hexenal, and (Z)-3-hexenol. The sweetness and the sweetness and sourness ratio were significantly higher in PCs than in the other three types tomatoes, which resulted in the overall acceptability and tomato-like flavor of PCs being perceived as more delicious. Decrease in sweetness is a prominent issue in modern tomato fruits, which can be improved by increasing the concentrations of sugars and volatiles with sweetness perception. However, sugar concentrations are reportedly negatively correlated with fruit weight (Folta and Klee, 2016). The most promising way to improve the sweetness of tomatoes is via the promotion of certain volatiles. Such investigations have great potential and are worth undertaking because (1) the concentrations of volatiles in tomato fruits are very low and can be increased greatly without affecting the yield or fruit size; there is an urgent requirement for the concentrations of consumer-preferred volatiles to be increased (Tieman et al., 2017) to improve the flavor intensity and variation in modern tomatoes.

The development of GC-O-MS has led to the identification of thousands of volatiles (El Hadi et al., 2013; Pott et al., 2019), and numerous odor characteristics are distinguishable by the developed human sense of olfactory (Pavagadhi and Swarup, 2020). Only a few dozen volatiles contribute substantially to flavor and only when their concentrations exceed the olfactory threshold (Czerny et al., 2008). Most volatiles can only be used as background odors (Tieman et al., 2012). This study identified 22 odor-impact compounds, 12 of which were consistent with those reported in the literature, e.g., hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-heptenal, 2,6,6-timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, (Z)-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadienal, 1-hexanol, (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, 1-(2,6,6-Trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-2-buten-1-one, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, methyl salicylate, and 2-isobutylthiazole (Tieman et al., 2012; Vallverdu-Queralt et al., 2013; Du et al., 2015). (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, 1-octen-3-one, (E)-2-nonenal, (2E)-3-(3-pentyl-2-oxiranyl)acrylaldehyde, and 4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol were found to be the important volatiles of tomato (Kreissl and Schieberle, 2017; Tieman et al., 2017). In the present study, decanal, (E)-2-octenal, (E,E)-2,4-nonadienal, ethyl octanoate, and 2-hydroxy-ethyl benzoate were shown to be important contributing volatiles to the flavor.

The OAVs of odor-impact compounds ranged from high to low for (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, (E)-2-hexenal, 1-(2,6,6- Trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-2-buten-1-one, 6-methyl-5-hep ten-2-one, hexanal, 2-isobutylthiazole, 2,6,6-timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, and (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one. Contrarily, the OAVs in a previous study on Italian tomatoes revealed (Z)-3-hexenal, (2E)-3-(3-pentyl-2-oxiranyl)acrylaldehyde, hexanal, wine lactone, (E)-β-damascenone, 1-penten-3-one, 1-octen-3-one, and (E,E)-2,4-decadienal to be the main odor contributors (Kreissl and Schieberle, 2017). The profiles of volatiles in tomato fruits appear to vary greatly among different genotypes and regions. Pearson’s correlation was used to indicate the contribution of chemicals to flavor. Fructose, glucose, citric acid, and 21 volatiles showed significant positive correlations (P < 0.05) with the [Ci(overall)] values. To our knowledge, the positive flavor characteristics are represented by the characteristic tomato taste, overall acceptability, sweetness, and floral, fruity, green, and vegetable odors, which are mainly derived from fructose, glucose, lipid-derive volatiles [hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-heptenal, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, 1-hexanol, (Z)-3-hexenol], carotenoid-derive volatiles [6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one] (Vogel et al., 2010), 2-phenylethanol, and 2-isobutylthiazole (Carbonell-Barrachina et al., 2005; Bartoshuk and Klee, 2013; Socaci et al., 2014; Klee and Tieman, 2018). The factors disliked by consumers were high sourness, phenolic odors, and pungent odors, which were mainly associated with the pH (Cohen et al., 2014; Tudor-Radu et al., 2016), esters (butyl acetate), Ile/Leu-derived volatiles (3-methyl-1-butanol), and Phe-derived volatiles (methyl salicylate and 2-methoxyphenol) (Piombino et al., 2013; Vallverdu-Queralt et al., 2013). In the present study, the volatiles with preferred odors and lower threshold concentrations were hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-octenal, 2,6,6-timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, (Z)-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadienal, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, (E)-2-heptenal, (E,E)-2,4-nonadienal, 1-penten-3-one, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, 4-(2,6,6- trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-3-buten-2-one, (E,Z)-6,10-dimethyl-3,5,9-undecatrien-2-one, (E,E)-6,10,4-trimethyl-5,9, 13-pentadecatrien-2-one, and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one. Their concentrations should be increased. Only malic acid, (2E)-3-(3-pentyl-2-oxiranyl)acrylaldehyde (metallic), 2-hydroxy-ethyl benzoate (herbs, sweet, spicy), methyl salicylate (wintergreen, herbal), and 2-methoxyphenol (smoky, sweet, woody, herbal) were disliked by the “consumers” (i.e., represented by the evaluation panels) and should, therefore, be reduced in tomato fruits. Baldwin et al. (1998) found that (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one had preferable odors in tomato fruits. Tieman et al. (2017) identified 33 chemicals linked to consumer preferences and 37 linked to the flavor intensity. Unexpectedly, several characteristic volatiles were not significantly correlated with consumer liking, such as (E)-2-hexenal, 1-penten-3-ol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, hexanol, and methyl salicylate (Klee and Tieman, 2018). The present study showed that both (E)-2-hexenal (0.479∗∗) and methyl salicylate (0.345∗∗) were very significantly positively correlated with the [Ci(overall)] values.

The sensory evaluation found a low correlation (only 0.06) between the taste score and odor intensity. The concentrations of taste compounds were not significantly correlated with odor intensity, and only several volatiles were significantly correlated with the taste score. These findings were consistent with those of a previous study, in which consumers largely considered sweet and sour to be important contributions to flavor (Andersen et al., 2019). Sugar and acid are considered to be the basic compounds for fruit flavor formation (Baldwin et al., 2008; Bastias et al., 2011), while the volatiles form the characteristic flavor compounds of different fruits (Baldwin et al., 2008; Du et al., 2015). Therefore, it is not scientifically valid to judge tomato flavor on taste alone; instead, taste and odor should both be assessed to comprehensively evaluate the flavor (Pavagadhi and Swarup, 2020). The results of the DTOPSIS evaluation in the present study indicated that tomato accessions with a preferred (i.e., “better”) flavor either scored high in the taste evaluation or had a strong odor.

The enhancement of consumer-preferred tomato fruits volatiles should be expected. From the perspective of metabolism, these preferred volatiles mainly come from fatty acids, carotenoids, and amino acids (Rambla et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2019), and the key enzymes involved in their production are lipase, lipoxygenase, hydroperoxidase lyase (Chen et al., 2004; Garbowicz et al., 2018), carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (Simkin et al., 2004; Ilg et al., 2014), phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, phenylacetaldehyde reductases, o-methyltransferases (Tieman et al., 2007; Tieman et al., 2010; Gapper et al., 2013), and branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase (Maloney et al., 2010). Many quantitative trait loci have been identified (Lin et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016; Bauchet et al., 2017; Kimbara et al., 2018; Ferrao et al., 2020), and the absence of relevant alleles has been noted in modern tomatoes (Zhu G. et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020). The reintroduction of certain alleles in modern tomatoes may be a feasible option to improve their flavor (Rigano et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2019). For example, the rare allele of the lipoxygenase C promoter has been shown to increase the concentrations of carotenoid-derived volatiles (Gao et al., 2019).

In the present study, only the free volatiles were analyzed, but the glycoside-bonded volatiles also account for a certain proportion of volatiles in tomato fruits. Glycoside-bonded volatiles serve as reserve odors and can be hydrolyzed by enzymes and acids to free volatiles (Schwab et al., 2015). Although the taste and odors of 71 tomato accessions were evaluated based on taste compounds and volatiles, the complexity of flavor and individual differences in the sensory evaluations complicates the process of improving tomato fruits flavor. Additionally, flavor factors can interact with each other; in which case both the concentration and proportion of the compounds affect the production of “good” flavors. Comprehensive investigations are still needed to effectively improve the flavor of tomato fruits. Driven by the motivation to breed delicious tomatoes and using multidisciplinary approaches that involve biological evolution, multiple omics, flavor chemistry, psychology, sociology, etc., researchers are presently exploring the flavor compounds that are absent in modern tomatoes, analyzing the reasons for these losses, studying the mechanisms of flavor formation, determining more scientifically valid and reasonable methods to evaluate flavor, clarifying the road map of tomato flavor improvement, and cultivating some tomato varieties with excellent flavor.

Conclusion

The flavor of 71 tomato accessions have significant differences, which can be divided into four categories according to the flavor evaluation scores. Seventy-one tomato accessions can be divided into four classes: among these, accessions PL11, PC4, PC2, PC8, RL35, RC6, and RC10 had better flavor; accessions PC4, PC8, RC10, RL2, and RL35 had better tomato taste; and accessions PL11, PC2, and RC6 had better tomato odor. The important flavor compounds were soluble solids, fructose, glucose, citric acid, the sugar and acid ratio, 1-hexanol, (Z)-3-hexenol, 2-phenylethanol, hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-heptenal, (E,E)-2,4-decadienal, 2,6,6-timethyl-1-cyclohexene-1-carboxaldehyde, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, (E)-6,10-dimetyl-5,9-undecadien-2-one, 4-(2,6,6-trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-3-buten-2-one, and 2-isobutylthiazole. These chemicals were positively correlated with flavor preferences and can, therefore, be used as targets for flavor improvement.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Material. The mass spectronomy data can be found here: doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12744695.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Northwest A&F University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

YL: conceptualization, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing, and project administration. GC: conceptualization, performing the experiments, data analysis, and writing—original draft preparation. FZ: supervision and writing—review and editing. PC: methodology, date analysis, and formula analysis. LW: visualization. YS: data analysis; AE-S: writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the Tomato Genetic Breeding and Quality Improvement Team of Northwest A&F University for providing the tomato material. Thanks to Yan Zhang for his suggestions on the test. Thanks also to Jing Zhang and Jing Zhao for their assistance in the use of GC-MS instruments in this experiment. Thanks to Qi Lu for her advice on the application of the formulas. Thanks to Dr. Tayeb Muhammad for correcting the English in this manuscript. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for the English language editing.

Abbreviations

- PC

pink cherry tomato

- PL

large-fruited tomato

- RC

red cherry tomato

- RL

red large-fruited tomato

- RT

retention time

- RI

retention index

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HS-SPME

headspace solid-phase microextraction

- GC-O-MS

gas chromatography–olfactometry–mass spectrometry

- SD

standard deviations

- CV

coefficient of variations

- OAV

odor activity values.

Funding. This work was supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (2016YFD0101703) and the Key Research and Development Projects of Shaanxi Province (2019ZDLNY03-05). The funder (YL) contributed to conceptualization, resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition in this study. The funder had no subjective effect on the results.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.586834/full#supplementary-material

Concentrations profiles of taste compounds of mature tomato fruits. aIn calibration curve (y = kx + b), “y” represents the theoretical concentration of the labeled standard, and “x” represents the peak area ratio of a compound in the internal standard. b‘—’ indicates that a labeled standard does not exist and, thus, a calibration curve was could not be created.

Concentrations of volatiles of different functional groups in 71 tomato accessions (10–9 kg L–1). n.d. represents not detected.

Concentrations of volatiles from different metabolic precursors in 71 tomato accessions (10–9 kg L–1). n.d. represents not detected.

Hedonism scores and odor activity values in 71 tomato accessions. aPC, PL, RC, and RL indicated pink cherry tomato, pink large-fruited tomato, red cherry tomato and red large-fruited tomato, respectively. bCi values represent the scores of the DTOPSIS analysis.

References

- Acosta-Quezada P. G., Raigon M. D., Riofrio-Cuenca T., Garcia-Martinez M. D., Plazas M., Burneo J. I., et al. (2015). Diversity for chemical composition in a collection of different varietal types of tree tomato (Solanum betaceum Cav.), an Andean exotic fruit. Food Chem. 169 327–335. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisala H., Manninen H., Laaksonen T., Linderborg K. M., Myoda T., Hopia A., et al. (2020). Linking volatile and non-volatile compounds to sensory profiles and consumer liking of wild edible Nordic mushrooms. Food Chem. 304:125403. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen B. V., Brockhoff P. B., Hyldig G. (2019). The importance of liking of appearance, -odour, -taste and -texture in the evaluation of overall liking. A comparison with the evaluation of sensory satisfaction. Food Qual. Prefer. 71 228–232. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin E. A., Goodner K., Plotto A. (2008). Interaction of volatiles, sugars, and acids on perception of tomato aroma and flavor descriptors. J. Food Sci. 73 S294–S307. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00825.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin E. A., Scott J. W., Bai J. H. (2015). Sensory and chemical flavor analyses of tomato genotypes grown in florida during three different growing seasons in multiple years. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Tec. 140 490–503. 10.21273/JASHS.140.5.490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin E. A., Scott J. W., Einstein M. A., Malundo T. M. M., Carr B. T., Shewfelt R. L., et al. (1998). Relationship between sensory and instrumental analysis for tomato flavor. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Tec. 123 906–915. 10.21273/JASHS.123.5.906 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin E. A., Scott J. W., Shewmaker C. K., Schuch W. (2000). Flavor trivia and tomato aroma: biochemistry and possible mechanisms for control of important aroma components. Hortsci. 35 1013–1022. 10.21273/HORTSCI.35.6.1013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk L. M., Klee H. J. (2013). Better fruits and vegetables through sensory analysis. Curr. Biol. 23 R374–R378. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastias A., Lopez-Climent M., Valcarcel M., Rosello S., Gomez-Cadenas A., Casaretto J. A. (2011). Modulation of organic acids and sugar content in tomato mature fruits by an abscisic acid-regulated transcription factor. Physiol. Plantarum 141 215–226. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2010.01435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauchet G., Grenier S., Samson N., Segura V., Kende A., Beekwilder J., et al. (2017). Identification of major loci and genomic regions controlling acid and volatile content in tomato fruits: implications for flavor improvement. New Phytol. 215 624–641. 10.1111/nph.14615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtic S., Ginies C., Causse M., Renard C. M. G. C., Page D. (2009). Changes in volatiles and glycosides during fruit maturation of two contrasted tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) lines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 57 591–598. 10.1021/jf8023062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttery R. G. (1993). “Quantitative and sensory aspects of flavour of tomato and other vegetables and fruits,” in Flavor Science: Sensible Principles and Techniques, eds Acree T. E., Teranishi R. (Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; ), 259–285. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell-Barrachina A. A., Agustí A., Ruiz J. J. (2005). Analysis of flavor volatile compounds by dynamic headspace in traditional and hybrid cultivars of Spanish tomatoes. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 222 536–542. 10.1007/s00217-005-0131-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers E. T., Koppel K. (2013). Associations of volatile compounds with sensory aroma and flavor: the complex nature of flavor. Molecules 18 4887–4905. 10.3390/molecules18054887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Hackett R., Walker D., Taylor A., Lin Z., Grierson D. (2004). Identification of a specific isoform of tomato lipoxygenase (TomloxC) involved in the generation of fatty acid-derived flavor compounds. Plant Physiol. 136 2641–2651. 10.1104/pp.104.041608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-N., Gao Q., Liu C.-J., Li D.-J., Liu C.-Q., Xue Y.-L. (2020). Comparison of volatile components in 11 Chinese yam (Dioscorea spp.) varieties. Food Biosci. 34:100531 10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Chen D., Jiang H., Sun H., Zhang C., Zhao H., et al. (2019). Aroma characterization of Hanzhong black tea (Camellia sinensis) using solid phase extraction coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and olfactometry and sensory analysis. Food Chem. 274 130–136. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G. T., Chang P. P., El-Sappah A. H., Zhang Y., Liang Y. (2020). Effect of fruit color and ripeness on volatiles profiles in cherry tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) fruit. Food Sci. Available onlien at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.2206.TS.20200722.1348.074.html (accessed September 26, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Itkin M., Yeselson Y., Tzuri G., Portnoy V., Harel-Baja R., et al. (2014). The PH gene determines fruit sourness and contributes to the evolution of sweet melons. Nat Commun. 5:4026. 10.1038/ncomms5026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çolaka N. G., Ekena N. T., Ülgerb M., Frarya A., Sami Doğanlar S. (2020). Exploring wild alleles from Solanum pimpinellifolium with the potential to improve tomato flavor compounds. Plant Sci. 298:110567. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortina P. R., Santiago A. N., Sance M. M., Peralta I. E., Carrari F., Asis R. (2018). Neuronal network analyses reveal novel associations between volatile organic compounds and sensory properties of tomato fruits. Metabolomics 14:57. 10.1007/s11306-018-1355-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czerny M., Christlbauer M., Christlbauer M., Fischer A., Granvogl M., Hammer M., et al. (2008). Re-investigation on odour thresholds of key food aroma compounds and development of an aroma language based on odour qualities of defined aqueous odorant solutions. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 228 265–273. 10.1007/s00217-008-0931-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’angelo M., Zanor M. I., Sance M., Cortina P. R., Boggio S. B., Asprelli P., et al. (2018). Contrasting metabolic profiles of tasty Andean varieties of tomato fruits in comparison with commercial ones. J. Sci. Food Agric. 98 4128–4134. 10.1002/jsfa.8930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X. F., Song M., Baldwin E., Rouseff R. (2015). Identification of sulphur volatiles and GC-olfactometry aroma profiling in two fresh tomato cultivars. Food Chem. 171 306–314. 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hadi M. A., Zhang F. J., Wu F. F., Zhou C. H., Tao J. (2013). Advances in fruit aroma volatile research. Molecules 18 8200–8229. 10.3390/molecules18078200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farneti B., Khomenko I., Grisenti M., Ajell I. M., Betta E., Algarra A. A., et al. (2017). Exploring blueberry aroma complexity by chromatographic and direct-injection spectrometric techniques. Front. Plant Sci. 8:617. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrao L. F. V., Johnson T. S., Benevenuto J., Edger P. P., Colquhoun T. A., Munoz P. R. (2020). Genome-wide association of volatiles reveals candidate loci for blueberry flavor. New Phytol. 226 1725–1737. 10.1111/nph.16459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folta K. M., Klee H. J. (2016). Sensory sacrifices when we mass-produce mass produce. Hortic Res. 3:16032. 10.1038/hortres.2016.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO] (2020). Available online at: http://www.fao.org/faostat/zh/?#data/QC/visualize (accessed Junuary 20, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Franklin L. M., Mitchell A. E. (2019). Review of the sensory and chemical characteristics of almond (Prunus dulcis) flavor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67 2743–2753. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Gonda I., Sun H., Ma Q., Bao K., Tieman D. M., et al. (2019). The tomato pan-genome uncovers new genes and a rare allele regulating fruit flavor. Nat. Genet. 51 1044–1051. 10.1038/s41588-019-0410-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapper N. E., Mcquinn R. P., Giovannoni J. J. (2013). Molecular and genetic regulation of fruit ripening. Plant Mol. Biol. 82 575–591. 10.1007/s11103-013-0050-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbowicz K., Liu Z. Y., Alseekh S., Tieman D., Taylor M., Kuhalskaya A., et al. (2018). Quantitative trait loci analysis identifies a prominent gene involved in the production of fatty acid-derived flavor volatiles in tomato and yariv brotman. Mol. Plant 11 1147–1165. 10.1016/j.molp.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni J. (2018). Tomato multiomics reveals consequences of crop domestication and improvement. Cell 172 6–8. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff S. A., Klee H. J. (2006). Plant volatile compounds: sensory cues for health and nutritional value? Science 311 815–819. 10.1126/science.1112614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]