Key Points

Question

What are the long-term outcomes of laparoscopic peritoneal lavage compared with primary resection as treatment of perforated purulent diverticulitis?

Findings

This multicenter randomized clinical trial of 145 patients at a Hinchey stage less than IV (73 with laparoscopic lavage and 69 with resection; 3 lost to follow-up) showed no difference in severe complications, mortality, functional outcomes, or quality of life between treatment groups over a median of 59 months of follow-up. There were more stomas in the resection group.

Meaning

In this trial, laparoscopic lavage and primary resection had similar long-term results in the treatment of perforated purulent diverticulitis.

This long-term follow-up portion of a multicenter randomized clinical trial conducted in Sweden and Norway examines the 5-year outcomes of laparoscopic peritoneal lavage vs primary resection as treatments for perforated purulent diverticulitis.

Abstract

Importance

Perforated colonic diverticulitis usually requires surgical resection, with significant morbidity. Short-term results from randomized clinical trials have indicated that laparoscopic lavage is a feasible alternative to resection. However, it appears that no long-term results are available.

Objective

To compare long-term (5-year) outcomes of laparoscopic peritoneal lavage and primary resection as treatments of perforated purulent diverticulitis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This international multicenter randomized clinical trial was conducted in 21 hospitals in Sweden and Norway, which enrolled patients between February 2010 and June 2014. Long-term follow-up was conducted between March 2018 and November 2019. Patients with symptoms of left-sided acute perforated diverticulitis, indicating urgent surgical need and computed tomography–verified free air, were eligible. Those available for trial intervention (Hinchey stages <IV) were included in the long-term follow-up.

Interventions

Patients were assigned to undergo laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or colon resection based on computer-generated, center-stratified block randomization.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was severe complications within 5 years. Secondary outcomes included mortality, secondary operations, recurrences, stomas, functional outcomes, and quality of life.

Results

Of 199 randomized patients, 101 were assigned to undergo laparoscopic peritoneal lavage and 98 were assigned to colon resection. At the time of surgery, perforated purulent diverticulitis was confirmed in 145 patients randomized to lavage (n = 74) and resection (n = 71). The median follow-up was 59 (interquartile range, 51-78; full range, 0-110) months, and 3 patients were lost to follow-up, leaving a final analysis of 73 patients who had had laparoscopic lavage (mean [SD] age, 66.4 [13] years; 39 men [53%]) and 69 who had received a resection (mean [SD] age, 63.5 [14] years; 36 men [52%]). Severe complications occurred in 36% (n = 26) in the laparoscopic lavage group and 35% (n = 24) in the resection group (P = .92). Overall mortality was 32% (n = 23) in the laparoscopic lavage group and 25% (n = 17) in the resection group (P = .36). The stoma prevalence was 8% (n = 4) in the laparoscopic lavage group vs 33% (n = 17; P = .002) in the resection group among patients who remained alive, and secondary operations, including stoma reversal, were performed in 36% (n = 26) vs 35% (n = 24; P = .92), respectively. Recurrence of diverticulitis was higher following laparoscopic lavage (21% [n = 15] vs 4% [n = 3]; P = .004). In the laparoscopic lavage group, 30% (n = 21) underwent a sigmoid resection. There were no significant differences in the EuroQoL-5D questionnaire or Cleveland Global Quality of Life scores between the groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

Long-term follow-up showed no differences in severe complications. Recurrence of diverticulitis after laparoscopic lavage was more common, often leading to sigmoid resection. This must be weighed against the lower stoma prevalence in this group. Shared decision-making considering both short-term and long-term consequences is encouraged.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01047462

Introduction

Acute perforated diverticulitis with peritonitis is a feared complication of diverticular disease. The incidence in Western countries is estimated to be 1.85 per 100 000 population per year for purulent peritonitis.1,2,3,4 Even with optimal treatment, perforated diverticulitis has a high morbidity and mortality. Traditionally, the standard treatment has been emergency surgery with resection of the diseased bowel, often with colostomy creation. Studies have indicated that laparoscopic lavage with drainage and antibiotics might be a treatment option in perforated diverticulitis.5,6 So far, 3 European randomized clinical trials have shown somewhat different results, and no clear advantages have been demonstrated with laparoscopic lavage, except a lower stoma rate at 1-year follow-up.4,7,8,9,10 Nine meta-analyses and systematic reviews11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 of the short-term and 1-year results of these trials have been published in the last 4 years, with divergent conclusions. No long-term results on laparoscopic lavage have yet been published.

In the Scandinavian Diverticulitis (SCANDIV) trial, there were significantly more reoperations in the lavage group at 90-day and 1-year follow-up, but at the same time, stoma prevalence was lower.4,7 The mortality and quality of life (QoL) were similar in both treatment groups. Comparable results were reported in the laparoscopic lavage arm of the Ladies trial,10 with a total reintervention rate at 30 days of 35% in the lavage group vs 7% in the resection group. Long-term outcomes are crucial to evaluate the benefit of lavage compared with standard treatment. One core issue is the number of patients in need of secondary surgery, either for complications, stoma reversal, or recurrence of diverticulitis. Other important aspects are functional outcomes and QoL.

The aim of this study was to analyze the long-term results of the SCANDIV trial in terms of severe complications (Clavien-Dindo score >IIIa). Secondary outcomes included mortality, secondary operations, recurrences, stoma prevalence, functional outcomes, and QoL.

Methods

Trial Design

The SCANDIV trial was designed as a pragmatic, 2-armed, open-labeled, multicenter, superiority randomized clinical trial. Patients were enrolled in 21 surgical units (9 in Sweden and 12 in Norway) with a catchment population of approximately 5 million people. The trial was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Southeastern Norway and the Regional Ethical Review Board Stockholm Sweden. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01047462).

Participants

Patients older than 18 years with a clinical suspicion of perforated diverticulitis and a need for emergency surgery were enrolled between February 5, 2010, and June 28, 2014. Additional inclusion criteria were the patient’s ability to tolerate general anesthesia and abdominal computed tomography results compatible with perforated diverticulitis and revealing free air. Exclusion criteria were bowel obstruction and pregnancy. Written informed consent was obtained before enrollment in the study. The process of patient inclusion has previously been described in detail.4,7

Randomization

Patients were randomly assigned to either laparoscopic lavage or sigmoid resection by a computer-generated, center-stratified block randomization, without disclosing the treatment allocation to the patient before surgery.4 If fecal peritonitis (Hinchey stage IV) was detected at surgery, sigmoid resection was performed irrespective of randomization. In this long-term follow-up, only patients with Hinchey stages less than IV were analyzed.

Follow-up

Data collection for this long-term follow-up was based on reviews of electronic patient records and telephone interviews between March 2018 and November 2019. For patients with dementia or other conditions creating an inability to complete the telephone interview, collateral information from relatives or employees of the assisted facility was sought when possible. At least 2 attempts of telephone contact at different points were made to each patient before considering the patient as lost to follow-up for QoL and functional outcome analyses. The protocol required colonoscopy within 3 months after laparoscopic lavage or before stoma reversal after the Hartmann procedure. For patients who could not be contacted and for whom no collateral information was available, only data retrieved from medical charts were included in analyses. The information was registered into a web-based electronic case report form, developed and administered by the Unit of Applied Clinical Research, Institute of Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, in Trondheim, Norway.

Outcomes

The main outcome measures at long-term follow-up were disease-associated severe complications. This included all severe postoperative complications (defined by a Clavien-Dindo score >IIIa) after the index operation and after disease-associated operations, such as stoma reversal, missed colonic carcinoma, recurrent diverticulitis, or elective sigmoid resections during the whole follow-up period. Elective stoma reversals or sigmoid resections per se were not considered disease-associated complications; rather, these were considered as such only when performed in the emergency setting. Secondary outcomes at 5 years included stoma prevalence, recurrence, and secondary sigmoid resections, as well as functional outcomes using the EuroQoL (EQ-5D) questionnaire and Cleveland Global QoL tool. The EQ-5D is a questionnaire used to evaluate health status. The EQ-5D-5L official user guide was used to present gathered information, and patients were subgrouped as suggested by the manual.20,21 The Cleveland Global QoL questionnaire includes 3 questions, and the total calculated score ranges from 0 to 1 (with 1 being excellent); a change in score of 0.1 was considered clinically important.22

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 25 (IBM). We used χ2 tests for proportions and 2-tailed t test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

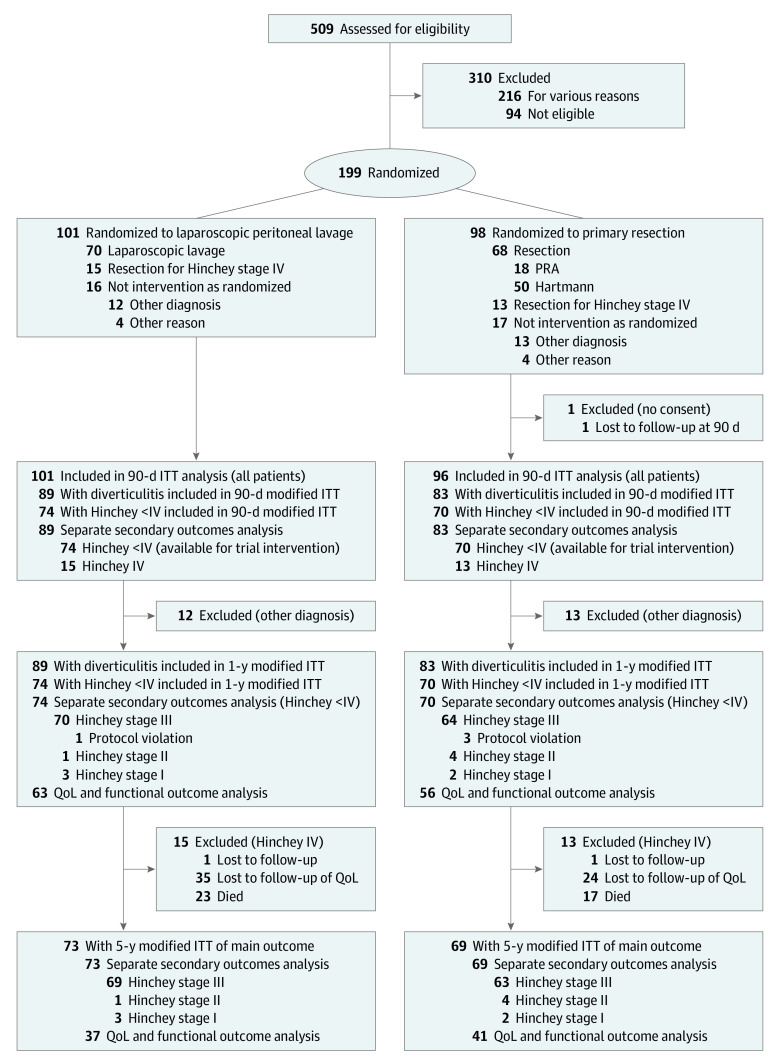

Of 509 screened patients, 94 were not eligible and a further 216 were not enrolled for various reasons (Figure). A total of 199 patients were randomly assigned to either laparoscopic lavage (n = 101) or primary resection (n = 98). One hundred forty-five patients, 74 in the lavage group and 71 in the resection group, were suitable for trial intervention (perforated purulent diverticulitis [Hinchey stage <IV, confirmed at index surgery]). Three patients were lost to follow-up. Thus, 73 patients randomized to lavage (mean [SD] age, 66.4 [13] years; 39 men [53%]) and 69 randomized to resection (mean [SD] age, 63.5 [14] years; 36 men [52%]) were included in this long-term follow-up, with a median follow-up time of 59 (interquartile range, 51-78; full range, 0-110) months. Baseline characteristics are assessed in Table 1.

Figure. Study Inclusion Flowchart.

IIT indicates intention to treat; PRA, primary resection with anastomosis; QoL, quality of life.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients Included in Long-term Follow-up With a Hinchey Stage Less Than IV.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lavage (n = 73) | Resection (n = 69) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 66.4 (13) | 63.5 (14) |

| Sex ratio (male:female) | 39:34 | 36:33 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.5 (5) | 26.1 (4) |

| Previous abdominal surgery | ||

| None | 53 (73) | 45 (65) |

| Single | 13 (18) | 15 (22) |

| Multiple | 7 (10) | 9 (13) |

| Previous episodes of diverticulitis | ||

| None | 57 (78) | 51 (74) |

| Single | 8 (11) | 10 (15) |

| Multiple | 8 (11) | 8 (12) |

| Comorbidity | ||

| None | 16 (22) | 14 (20) |

| Anti-inflammatory medication use | 16 (22) | 14 (20) |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease or asthma | 9 (12) | 14 (20) |

| Ischemic heart disease or heart failure | 6 (8) | 15 (22) |

| Cigarette smoking | 8 (11) | 12 (17) |

| Alcoholism or drug abuse | 2 (2) | 6 (8) |

| Active malignant condition | 5 (6) | 3 (4) |

| Insulin-treated diabetes | 3 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Immunodeficiency or chronic hepatitis | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

| Uremia needing dialysis | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 45 (62) | 45 (64) |

| American Society of Anesthesiology level | ||

| I | 12 (16) | 11 (16) |

| II | 38 (52) | 26 (38) |

| III | 20 (27) | 31 (45) |

| IV | 3 (4) | 1 (1) |

| V | 0 | 0 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 3.8 (2) | 3.6 (2) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Severe complications (excluding stoma reversals and elective sigmoid resections because of recurrence) were 36% (n = 28) in the laparoscopic lavage group and 35% (n = 24) in the resection group (P = .92; Table 2). Overall mortality was 32% (n = 23) in the laparoscopic lavage group and 25% (n = 17) in the resection group (P = .36). Secondary operations, including stoma reversal, were performed in 36% (n = 28) vs 35% (n = 24; P = .92), respectively. Among patients alive at long-term follow-up, the stoma prevalence was 8% (n = 4) vs 33% (n = 17; P = .002) (Table 2). Recurrence of diverticulitis occurred in 15 patients (21%) after laparoscopic lavage, compared with 3 (4%) after resection in the laparoscopic lavage group; 30% (n = 21) had undergone sigmoid resection at the time of follow-up. Eight of these patients were resected during the index admission (1 because of technical difficulties during lavage and the others because of uncontrolled sepsis and clinical deterioration). Nine of the remaining sigmoid resections were because of recurrence of diverticulitis, and 4 were because of cancer not detected at the index operation. All sigmoid resections, except for 1, were performed within 1 year from the index admission. Total length of hospital stay, including the index admission, were similar in both groups. Unplanned reoperations were more frequent in the laparoscopic lavage group (26% [n = 19] vs 12% [n = 8]; P = .03), as well as unplanned readmissions (34% [24 of 70] vs 11% [7 of 64]), whereas the total number of readmissions were similar (Table 2). All reasons for unplanned reoperations are listed in eTable 1 in Supplement 1.

Table 2. Secondary Outcomes in Patients With Diverticulitis of Hinchey Stage III or Less at Long-term Follow-up.

| Outcome | Patients, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic lavage (n = 73) | Resection (n = 69) | ||

| Severe complications | 26 (36) | 24 (35) | .92 |

| Patients alive with stoma, No./total No. (%) | 4/50 (8) | 17/52 (33) | .002 |

| Secondary reoperations (including stoma reversal) | 26 (36) | 24 (35) | .92 |

| Stoma reversal | 5 (7) | 17 (25) | .003 |

| Unplanned reoperations | 19 (26) | 8 (12) | .03 |

| Patients, No./total No. (%) | |||

| With readmissions | 28/70 (40) | 26/64 (41) | .94 |

| With unplanned readmissions | 24/70 (34) | 7/64 (11) | .001 |

| Total hospital stay, median (IQR), d | 14 (6-20) | 11 (7-20) | .79 |

| Diverticulitis recurrence | |||

| Total | 15 (21) | 3 (4) | .004 |

| Acute complicated diverticulitis | 5 (7) | 2 (3) | NA |

| Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis | 10 (14) | 1 (1) | NA |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

Four patients in the laparoscopic lavage group were diagnosed with sigmoid cancer after the index operation, compared with 2 in resection group. Those in the resection group were both diagnosed at histopathology following the index operation, making the rate of misdiagnosed cancer 4.2% in the group with Hinchey stages less than IV.

Of 102 total patients alive at long-term follow-up, 38 (76%) in the lavage group and 45 (87%) in the resection group could complete a telephone interview and were included in the analyses of functional outcomes and QoL. Their mean (SD) age at follow-up was 66.4 (12.8) years and 59.6 (13.5) years, respectively (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). There was no difference in Cleveland Global Quality of life scores between the groups (mean [SD], 0.72 [0.19] vs 0.69 [0.15]; P = .61). In the EQ-5D questionnaire, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups in any reported dimension. Although not significant, there were numerically more patients reporting pain (17 of 47 [46%] vs 29 of 43 [77%]; P = .07) and problems with mobility (7 of 47 [19%] vs 16 of 43 [37%]; P = .09) in the resection group (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Functional outcomes were similar between the groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Patient-Reported Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life.

| Characteristic | Patients, No./total No. (%)a | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic lavage (n = 38) | Resection (n = 45) | ||

| Cleveland Global Quality of Life score, mean (SD)b | 0.72 (0.19) | 0.69 | .61 |

| Problems recorded in EQ-5D summary score of all 5 dimensionsc | |||

| None reported | 14/37 (38) | 10/43 (23) | NA |

| Slight or moderate in at least 1 dimension | 17/37 (46) | 26/43 (61) | NA |

| Severe or extreme in at least 1 dimension | 6/37 (16) | 7/43 (16) | NA |

| Abdominal pain | |||

| Daily | 0/36 (0) | 3/45 (7) | .24 |

| More than once/wk | 5/36 (14) | 4/45 (9) | |

| Less than once/wk | 31/36 (86) | 38/45 (84) | |

| Social contact compared with before operation | |||

| Unchanged | 29/36 (81) | 33/44 (75) | .17 |

| Changes | 7/36 (19) | 7/44 (16) | |

| Dramatic changes | 0/36 (0) | 4/44 (9) | |

| Sexual function compared with before operation | |||

| Unchanged | 25/36 (69) | 33/45 (73) | .98 |

| Changes | 6/36 (17) | 7/45 (16) | |

| Dramatic changes | 1/36 (3) | 1/45 (2) | |

| Irrelevant | 4/36 (11) | 4/45 (9) | |

| Patients with stoma | 2/38 (5) | 13/45 (29) | <.001 |

| Stoma-associated problems | NA | ||

| Daily | 0/38 | 0/44 | |

| >1 wk | 1/38 (3) | 2/44 (5) | |

| <1 wk Or none | 1/38 (3) | 10/44 (23) | |

| Irrelevant | 36/38 (95) | 32/44 (73) | |

| Needs help with stoma care | 0/38 | 1/44 (2) | |

Abbreviation: EQ-5D, EuroQoL 5-Dimension score.

Patients who had died and those who could not be reached are excluded from analysis.

Missing data for 2 patients in lavage group and 1 patient in the resection group. The Cleveland Global Quality of Life score range was 0 to 1 (0, worst; 1, best).

Detailed EQ-5D data are reported in Supplement 2.

Discussion

The present long-term results (median follow-up, 59 months) of the SCANDIV trial, the largest completed randomized clinical trial (to our knowledge) comparing laparoscopic lavage with sigmoid resection in acute perforated purulent diverticulitis, demonstrate no significant difference in severe complications or overall mortality between the 2 treatment groups. However, there were more unplanned reoperations, unplanned readmissions, and recurrence of diverticulitis in the laparoscopic lavage group. Nearly one-third of patients (30%) in the laparoscopic lavage group ended up with a sigmoid resection. Not surprisingly, the overall stoma prevalence was remarkably lower in the laparoscopic lavage group. The proportions of secondary operations, when stoma reversals were included, were similar in both groups. No significant differences in QoL and functional outcomes were observed, although there was a nonsignificant difference of more pain and immobility in the resection group. However, the SCANDIV trial may have been underpowered to detect an actual difference in these dimensions of QoL.

During the long-term follow-up, there were only 5 additional secondary operations in the laparoscopic lavage group and 3 in the resection group, emphasizing that most of the secondary operations were performed within the first year after index surgery. There were no diverticulitis-associated or procedure-associated emergency interventions after 1 year of follow-up. This is consistent with previous cohort studies on diverticulitis, showing that most severe complications occur within the first year after acute complicated diverticulitis.23

A concern about missed adenocarcinomas in the laparoscopic lavage group has previously been raised. The colon cancer rate in this study was 4.2%, and all 4 patients in the laparoscopic lavage group with colon cancer were diagnosed within the first year. Postoperative colonoscopy was mandatory in the lavage group, and this finding supports the importance to rule out malignant disease in patients with complicated diverticular disease.24,25

A cost analysis should be considered when assessing the best treatment option. Although this has not been done yet for the SCANDIV trial, it was performed in the Diverticulitis–Laparoscopic Lavage (DILALA) and the Laparoscopic Lavage arm of the Ladies Trial randomized clinical trials, indicating that laparoscopic lavage was more cost-effective.26,27 Laparoscopic lavage is associated with shorter operating time as well as a shorter length of hospital stay.14,28

A recent retrospective long-term follow-up of a cohort of 38 patients treated with laparoscopic lavage (median follow-up time, 46 [interquartile range, 7-77] months) showed a disease-associated mortality of 11% and an overall mortality rate of 21%, which is lower than in our study.29 Although the recurrence rate of diverticulitis was higher (32%) than in SCANDIV, the rate of secondary surgery, including stoma reversal, was similar. However, these were selected patients, and the study lacked uniform treatment criteria for laparoscopic lavage as well as a control group. The DILALA trial has presented a 2-year follow-up, including subgroup analysis based on treatment intervention, showing a stoma rate of 7% in the laparoscopic lavage group and 23% in the resection group, which was limited to the Hartmann procedure.30 In a recent meta-analysis (including the SCANDIV and DILALA trials and laparoscopic lavage arm of the Ladies trial, along with 4 comparative studies), no significant differences were seen in mortality, 30-day reoperations, and unplanned readmission rates.16 Higher rates of intra-abdominal abscesses and increased long-term emergency reoperations were seen in the laparoscopic lavage group, and the benefits were shorter operation time, fewer wound infections, and shorter lengths of hospital stay. In the recent American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ “Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Left-Sided Colonic Diverticulitis,”31 there is a strong recommendation that colectomy be preferred over laparoscopic lavage in patients with purulent peritonitis, because laparoscopic lavage is associated with higher rates of secondary interventions. The authors31 concluded that laparoscopic lavage lacks clear selection criteria and standardized operational technique and entails a risk of unresolved septic foci requiring secondary intervention.32,33 In contrast, the newly published European Society of Coloproctology’s “Guidelines for the Management of Diverticular Disease of the Colon” considers laparoscopic lavage feasible in selected patients with peritonitis at Hinchey stage III, based on the same 3 randomized clinical trials and several noncomparative cohorts.7,9,10,34,35

Strengths

This study presents long-term follow-up of the largest randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic lavage with resection surgery in perforated diverticulitis. Loss to follow-up was low, making the results very reliable. Only 3 patients were lost to follow-up of the primary outcome, and a few more (n = 17) were lost to the analyses of functional outcomes, mainly because of the advanced age of the study population, with several patients currently living in assisted-living facilities.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that of all eligible patients, approximately 50% were not included.4 This can be attributed to the difficulties in conducting randomized clinical trials in an emergency clinical setting, where time constraints, patient involvement, and consent can be difficult to achieve. Plausibly, the personal opinion of the surgeon, because of the patient’s clinical assessment, may also have sometimes discouraged study inclusion. Consequently, the patients with the most severe illness and frailty might not have been included, and the results are not generalizable to them. Similar inclusion of eligible patients is also true for both of other randomized clinical trials.8,10 Preoperative randomization in the SCANDIV trial resulted in the exclusion of some patients from this long-term follow-up (with diagnoses other than perforated diverticulitis or Hinchey stage IV). This may have hampered the randomization. However, the number of exclusions and the baseline characteristics after exclusion were very similar in the 2 groups.

Conclusions

The question of which surgical approach should be the treatment of choice when facing a patient in the emergency department with perforated purulent diverticulitis remains. Laparoscopic lavage is faster and cost-effective but leads to a higher reoperation rate and recurrence rate, often requiring secondary sigmoid resection. However, the stoma prevalence is lower in the laparoscopic lavage group, both in short-term and long-term follow-up. After 5 years, approximately 1 in 3 patients still had a stoma in the resection group. Therefore, laparoscopic lavage may be used as a bridge to overcome the emergency septic state and lead to an elective sigmoid resection. This should be discussed with the patient whenever possible, also taking into account that preoperative differentiation between purulent and fecal peritonitis (Hinchey stage III vs IV) is impossible. Therefore, all patients selected for laparoscopic lavage should have consent secured for resection surgery as well.

The present long-term follow-up demonstrates no difference in severe complication or QoL, making laparoscopic lavage a feasible option in perforated purulent diverticulitis. Recurrence of diverticulitis after laparoscopic lavage is higher, often leading to sigmoid resection, but without stoma creation, which is usually the case in an emergency setting. Shared decision-making that takes both short-term and long-term consequences into account will be the key to better management of patients with perforated purulent diverticulitis.

eTable 1. Reasons for unplanned reoperations

eTable 2. Baseline characteristics of patients available for QoL follow-up

eTable 3. Quality of life (EQ-5D)

Trial Protocol.

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179-1187.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delvaux M Diverticular disease of the colon in Europe: epidemiology, impact on citizen health and prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(suppl 3):71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris CR, Harvey IM, Stebbings WS, Hart AR. Incidence of perforated diverticulitis and risk factors for death in a UK population. Br J Surg. 2008;95(7):876-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz JK, Yaqub S, Wallon C, et al. ; SCANDIV Study Group . Laparoscopic lavage vs primary resection for acute perforated diverticulitis: the SCANDIV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1364-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers E, Hurley M, O’Sullivan GC, Kavanagh D, Wilson I, Winter DC. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for generalized peritonitis due to perforated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2008;95(1):97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toorenvliet BR, Swank H, Schoones JW, Hamming JF, Bemelman WA. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for perforated colonic diverticulitis: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(9):862-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultz JK, Wallon C, Blecic L, et al. ; SCANDIV Study Group . One-year results of the SCANDIV randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic lavage versus primary resection for acute perforated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104(10):1382-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thornell A, Angenete E, Bisgaard T, et al. Laparoscopic lavage for perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(3):137-145. doi: 10.7326/M15-1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angenete E, Thornell A, Burcharth J, et al. Laparoscopic lavage is feasible and safe for the treatment of perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: the first results from the randomized controlled trial DILALA. Ann Surg. 2016;263(1):117-122. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vennix S, Musters GD, Mulder IM, et al. ; Ladies trial colloborators . Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or sigmoidectomy for perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10000):1269-1277. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61168-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceresoli M, Coccolini F, Montori G, Catena F, Sartelli M, Ansaloni L. Laparoscopic lavage versus resection in perforated diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s13017-016-0103-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angenete E, Bock D, Rosenberg J, Haglind E. Laparoscopic lavage is superior to colon resection for perforated purulent diverticulitis-a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(2):163-169. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2636-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galbraith N, Carter JV, Netz U, et al. Laparoscopic lavage in the management of perforated diverticulitis: a contemporary meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(9):1491-1499. doi: 10.1007/s11605-017-3462-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cirocchi R, Di Saverio S, Weber DG, et al. Laparoscopic lavage versus surgical resection for acute diverticulitis with generalised peritonitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(2):93-110. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1585-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall JR, Buchwald PL, Gandhi J, et al. Laparoscopic lavage in the management of Hinchey grade III diverticulitis: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):670-676. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penna M, Markar SR, Mackenzie H, Hompes R, Cunningham C. Laparoscopic lavage versus primary resection for acute perforated diverticulitis: review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2018;267(2):252-258. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed AM, Moahammed AT, Mattar OM, et al. Surgical treatment of diverticulitis and its complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Surgeon. 2018;16(6):372-383. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt S, Ismail T, Puhan MA, Soll C, Breitenstein S. Meta-analysis of surgical strategies in perforated left colonic diverticulitis with generalized peritonitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2018;403(4):425-433. doi: 10.1007/s00423-018-1686-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaikh FM, Stewart PM, Walsh SR, Davies RJ. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage or surgical resection for acute perforated sigmoid diverticulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2017;38:130-137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks R EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53-72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EuroQol Research Foundation EQ-5D—user guide. Published 2018. Accessed November 12, 2020. https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/

- 22.Kiran RP, Delaney CP, Senagore AJ, et al. Prospective assessment of Cleveland Global Quality of Life (CGQL) as a novel marker of quality of life and disease activity in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(8):1783-1789. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritz JP, Lehmann KS, Frericks B, Stroux A, Buhr HJ, Holmer C. Outcome of patients with acute sigmoid diverticulitis: multivariate analysis of risk factors for free perforation. Surgery. 2011;149(5):606-613. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azhar N, Buchwald P, Ansari HZ, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer following CT-verified acute diverticulitis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2020. doi: 10.1111/codi.15073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortensen LQ, Burcharth J, Andresen K, Pommergaard HC, Rosenberg J. An 18-year nationwide cohort study on the association between diverticulitis and colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2017;265(5):954-959. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gehrman J, Angenete E, Björholt I, Bock D, Rosenberg J, Haglind E. Health economic analysis of laparoscopic lavage versus Hartmann’s procedure for diverticulitis in the randomized DILALA trial. Br J Surg. 2016;103(11):1539-1547. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vennix S, van Dieren S, Opmeer BC, Lange JF, Bemelman WA. Cost analysis of laparoscopic lavage compared with sigmoid resection for perforated diverticulitis in the Ladies trial. Br J Surg. 2017;104(1):62-68. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan Z, Pan ZH, Pan RZ, Xie YX, Desai G. Is laparoscopic lavage safe in purulent diverticulitis versus colonic resection? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2019;71:182-189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sneiders D, Lambrichts DPV, Swank HA, et al. Long-term follow-up of a multicentre cohort study on laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for perforated diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21(6):705-714. doi: 10.1111/codi.14586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohl A, Rosenberg J, Bock D, et al. Two-year results of the randomized clinical trial DILALA comparing laparoscopic lavage with resection as treatment for perforated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2018;105(9):1128-1134. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall J, Hardiman K, Lee S, et al. ; Prepared on behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons . The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of left-sided colonic diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(6):728-747. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Acuna SA, Wood T, Chesney TR, et al. Operative strategies for perforated diverticulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(12):1442-1453. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gervaz P, Ambrosetti P. Critical appraisal of laparoscopic lavage for Hinchey III diverticulitis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8(5):371-375. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i5.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Binda GA, Bonino MA, Siri G, et al. ; LLO Study Group . Multicentre international trial of laparoscopic lavage for Hinchey III acute diverticulitis (LLO Study). Br J Surg. 2018;105(13):1835-1843. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultz JK, Azhar N, Binda GA, et al. European Society of Coloproctology: guidelines for the management of diverticular disease of the colon. Colorectal Dis. 2020. doi: 10.1111/codi.15140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Reasons for unplanned reoperations

eTable 2. Baseline characteristics of patients available for QoL follow-up

eTable 3. Quality of life (EQ-5D)

Trial Protocol.

Data Sharing Statement.