Abstract

Background:

Concurrent pheochromocytoma and/or paraganglioma (PPGL) in pregnant women can lead to severe complications and death due to associated catecholamine excess. We aimed to identify factors associated with maternal and fetal outcomes in women with PPGL during pregnancy.

Methods:

We performed a multi-center retrospective study of patients with PPGL and pregnancy between 1980 and 2019 and a systematic review of literature conducted on studies published between 2005 and 2019 containing at least 5 cases. Outcomes of interest were maternal/fetal death and maternal severe cardiovascular complications of catecholamine excess.

Findings:

We identified 232 eligible patients who had a total of 249 pregnancies while harboring a PPGL. Diagnosis was made before, during pregnancy, or after delivery in 37 (15%), 134 (54%), and 78 (31%) cases, respectively. Of 144 patients evaluated for genetic predisposition for pheochromocytoma, 95 (66%) were positive. Unrecognized PPGL during pregnancy (OR of 27.0; 95%CI 3.5-3128.0), abdominal/pelvic tumor location (OR of 11.3; 95%CI 1.5-1441.0), and catecholamine level ≥10 times the upper limit of reference range (OR of 4.7; 95%CI 1.8-13.8) were associated with adverse outcomes. For patients diagnosed antepartum, alpha-adrenergic blockade therapy prevented adverse outcomes (OR 3.6; 95%CI 1.1-13.2), while antepartum surgery was not associated with better outcomes (no surgery vs surgery: OR 0.9; 95%CI 0.3-3.9).

Interpretation:

Unrecognized and untreated PPGL was associated with a 27-times higher risk of either maternal or fetal complications. Appropriate case detection and counseling performed in premenopausal women at risk for PPGL may prevent adverse pregnancy-related outcomes.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health, Maryland, USA.

Keywords: catecholamine excess, paraganglioma, death, hypertension, genetics

Background

Pheochromocytoma (PHEO) and paraganglioma (PGL), collectively known as PPGL, are tumors that may secrete catecholamines(1). Release of catecholamines potentially leads to severe clinical consequences such as hypertensive crisis, stroke, and even death. Germline pathogenic variants are now identified in 40-50% of individuals with PPGL(2). Case detection programs for individuals genetically predisposed to PPGL use biochemical and imaging work-up to detect these tumors early in an attempt to decrease PPGL-related morbidity and mortality(3). Despite this change in practice, the majority of PPGL are still discovered incidentally on imaging performed for another reason or based on symptoms related to catecholamine production rather than through case detection testing(4).

In a pregnant woman, an unrecognized PPGL can be devastating as untempered catecholamine action can alter both maternal and fetal physiology leading to severe complications or even death (5-10). Only a few small retrospective studies report on the presentation, management and outcomes of pregnant women with PPGL(5-7, 9, 11-13). Therefore, determining predictors of favorable outcomes and making strong conclusions about optimal management is challenging.

Given the potentially deleterious maternal and fetal outcomes and the uncertain course of action, a systematic exploration of pregnancy-associated PPGL is needed. This is especially relevant given the significant advances made over the last decade in the genetic classification, clinical characterization, and anesthetic and therapeutic approaches for PPGL(3, 14-21). As such, we sought to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of women with PPGL during pregnancy, to identify factors associated with maternal and fetal outcomes, to determine the best approach to management of PPGL during pregnancy, and to develop recommendations for women with a known genetic predisposition for PPGL who are contemplating pregnancy.

METHODS

Study design and participants

Considering the rare incidence of this condition, we followed the framework by Lin et al recommending a combination of an original observational study and a systematic review of the literature that identifies additional non-overlapping cases(22). Therefore, we combined an international retrospective multi-center study based on the newly founded International-Pheochromocytoma-and-Pregnancy-Registry of patients with PPGL and pregnancy occurring between 1980 and 2019 and a systematic review of literature conducted on studies published between January 1st, 2005 to December 27th, 2019 (Appendix Table 1, 2). The multicenter study has been conducted in accordance to the local ethical/IRB committees for all participating centers. All patients provided either written informed consent or a consent waiver was used, depending on the local IRB requirements. A comprehensive search of several databases was conducted by an experienced librarian with input from the study’s principle investigator (Appendix Table 3). Case reports and case series with fewer than 5 patients were excluded. The systematic review of literature included 8 studies reporting on 73 pregnancies in 65 patients with PPGL with a period of enrollment of 1984-2015 (Appendix figure 1, Appendix Tables 4-6). Individual patient data collection from the included studies was performed independently and in duplicate by two investigators (NIA and RJK), and any discrepancies were resolved by the primary author. Assessment of methodological quality of studies was performed based on previously reported approach(23), with 7 of 8 studies demonstrating an adequate quality (Appendix Table 7). After excluding additional 21 pregnancies due to potential overlap and insufficient information (Appendix Table 1), the final cohort included a total of 249 pregnancies, 197 pregnancies from the multicenter study and 52 from the systematic review.

Any patient with pregnancy after 1980, and meeting one of the following inclusion criteria was eligible: 1) known PPGL during pregnancy, discovered before or during pregnancy, or 2) PPGL discovered within 12 months postpartum. If a patient had more than one pregnancy and untreated PPGL, each pregnancy was recorded separately with corresponding fetal and maternal outcomes. We recorded patient characteristics (demographics, germline pathogenic variant, follow up data), PPGL characteristics (type of PPGL, tumor size, number of tumors, presence of metastases, biochemical profile (noradrenergic, adrenergic, or dopaminergic), and type of therapy, and pregnancy related data (age at pregnancy, timing of PPGL diagnosis in relation to pregnancy, maternal symptoms of catecholamine excess during pregnancy, pregnancy outcome, including type and time of delivery, potential termination of pregnancy, complications during delivery, maternal and fetal complications). Severe cardiovascular complications of catecholamine excess included death or any cardiovascular event requiring intensive care or leading to permanent sequelae occurring any time during pregnancy or up to 3 days postpartum. When tested and present, PPGL germline pathogenic variants included PPGL susceptibility genes RET (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, MEN 2), VHL (von Hippel-Lindau disease), SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SDHAF2 (paraganglioma syndromes type 1-5, pathogenic variants of the succinate dehydrogenase subunit genes, SDHx), and other familial PPGL caused by pathogenic variants of the genes TMEM127 and MAX(14, 15, 24, 25). Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) was diagnosed in accordance with the NIH consensus criteria(26).

Statistical Methods

Pregnancy related maternal and fetal outcomes were analyzed only for pregnancies with known outcomes, pregnancies that were not electively terminated, and only for patients with functioning PPGL. Descriptive data are presented as frequencies for categorical variables and medians with ranges for continuous variables. Subgroup comparisons were performed using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and the Kruskal Wallis test for continuous variables. We pre-defined the following variables for analysis of association with maternal and fetal outcomes: 1) Timeline for PPGL discovery in relation to pregnancy (during, after vs before pregnancy), 2)Year of pregnancy (above and below median year of pregnancy in our cohort), 3) Location of PPGL ( abdominal/pelvic vs other), 4) Degree of catecholamine excess (>10 times upper normal range vs <10 times normal range), 5) Antepartum surgery, 6) Alpha-adrenergic blockade of at least 2 weeks duration, 7) Cesarean-section (C-section) versus vaginal delivery, 8) Presence of genetic predisposition for PPGL, 9) Metastatic PPGL. Variables possibly associated with maternal and fetal outcomes were evaluated using logistic regression and expressed as odds ratios. Multivariable analysis was not performed. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the R programming environment(27).

Findings

Patients

We identified 232 eligible patients who had a total of 249 pregnancies while harboring a PPGL: 215 patients had a single pregnancy, 10 patients had 2 pregnancies, 1 patient had 3 pregnancies, and 1 patient had 6 pregnancies. At the time of pregnancy, 182 (78%) patients had a single PPGL (PHEO in 142 (62%), PGL in 41 (17%)), 30 (13%) had multiple primary PPGL (bilateral PHEO in 19, 8%; multiple PGL in 11, 5%), and 20 (9%) patients had metastatic PPGL (Table 1). Median tumor diameter was 53 mm (range, 13-310). The majority of patients (220, 95%) presented with a functioning PPGL, with a noradrenergic profile in 103 (47%), adrenergic in 91 (41%), purely dopaminergic in 3 (1%), and unknown profile in 23 (11%).

Table 1:

Clinical presentation and treatment of patients with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PPGL)

| Number of patients | N=232 |

|---|---|

| Number of pregnancies | N=249 |

| 1 | 215 (92.7%) |

| 2 | 10 (4.3%) |

| 3 | 1 (0.4%) |

| 6 | 1 (0.4%) |

| Age at pregnancya | |

| Years, median (range) | 29 (15, 46) |

| Year of pregnancya (n=199)b | |

| Median (range) | 2012 (1980, 2019) |

| Type of disease(n=230)b | |

| Pheochromocytoma (PHEO) | |

| Unilateral PHEO | 142 (61.7%) |

| Bilateral PHEO | 19 (8.3%) |

| Paraganglioma (PGL) | |

| Head and neck PGL | 5 (2.2%) |

| Thoracic PGL | 6 (2.6%) |

| Abdominal/Pelvic PGL | 27 (11.7%) |

| Multiple primary PPGL | 11 (4.8%) |

| Metastatic PPGL | 20 (8.7%) |

| Genetic predisposition | |

| RET | 28 (12.1%) |

| SDHB | 27 (11.6%) |

| VHL | 18 (7.8%) |

| SDHD | 8 (3.4%) |

| NF1 | 5 (2.2%) |

| MAX | 2 (0.9%) |

| SDHC | 2 (0.9%) |

| SDHA | 1 (0.4%) |

| FH | 1 (0.4%) |

| CDKN2B | 1 (0.4%) |

| Carney Triad | 2 (0.9%) |

| Tested, not identified | 49 (21.1%) |

| Not tested | 88 (37.9%) |

| Family history of PPGL(n=196)b | |

| Yes | 49 (25.3%) |

| No | 145 (74.7%) |

| Tumor size (n=190)b | |

| mm, median (range) | 53 (13, 310) |

| Catecholamine excess | |

| Functioning | 220 (94.8%) |

| Noradrenergic | 103 (46.8%) |

| Adrenergic | 91 (41.4%) |

| Dopaminergic | 3 (1.4%) |

| Unknown subtype | 23 (10.5%) |

| Nonfunctioning | 12 (5.2%) |

| Degree of catecholamine excess (in functioning tumors) (n=190)b | |

| 2x upper limit of normal | 34 (19.1%) |

| 5x upper limit of normal | 29 (16.3%) |

| 10x upper limit of normal | 26 (14.6%) |

| >10x upper limit of normal | 89 (50.0%) |

| Therapy of PPGL(n=231)b | |

| Surgery during pregnancy | 42 (18.2%) |

| Gestation week, median (range) | 20 (10, 35) |

| Surgery after pregnancy | 161 (69.7%) |

| Weeks post-delivery, median (range), n=151 | 8 (0, 224) |

| No surgery | 28 (12.1%) |

Reported once for each patient, at the time of first pregnancy

Several categories have missing data, number indicates number of patients with available data

In 194 patients with available data, 49 (25%) patients reported family history of PPGL at the time of pregnancy, and 144 were tested for a predisposing germline pathogenic variant (or had a documented clinical diagnosis of NF1 or Carney triad); of these, 95 (66%) were positive (RET in 28, SDHB in 27, VHL in 18, SDHD in 8, NF1 in 5, and other syndromes in 9), (Table 1).

Pregnancies

PPGL was discovered during pregnancy in 134 (54%) patients at a median of 24 weeks gestation (range 2-38, Table 2). In 78 (31%) patients, PPGL was not recognized during pregnancy but was discovered at a median of 6 weeks (range, 0-52) after delivery (Figure 1). Of 37 (15%) women with known PPGL prior to pregnancy, 17 (46%) had metastatic PPGL not amenable to surgery, and 20 (54%) have not yet been operated for a resectable PPGL. Patients reported symptoms and signs of catecholamine excess during 206 (83%) pregnancies (Table 2). Of these, the most common was hypertension (191, 77%), followed by palpitations (117, 58%), headaches (102, 50%), and diaphoresis (87, 45%).

Table 2:

Clinical presentation and outcomes of pregnancy in women with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PPGL)

| Number of pregnancies in women with PPGL | N=249 |

|---|---|

| Age at pregnancya | 28 (15, 46) |

| Years, median (range) | |

| Year of pregnancya (n=214 b) | |

| Median (range) | 2012 (1980, 2019) |

| Time of PPGL discovery in relation to pregnancya | |

| Before pregnancy | 37 (14.9%) |

| During pregnancy | 134 (53.8%) |

| Gestation week, median (range), n=129 | 24.0 (2.0, 38.0) |

| After pregnancy | 78 (31.3%) |

| Weeks after delivery, median (range), n=54 | 6.0 (0.0, 52) |

| Signs and symptoms of catecholamine excess during pregnancya | |

| Symptoms | 206 (82.7%) |

| No symptoms | 43 (17.3%) |

| Management during pregnancya | |

| Surgery | 42 (16.9%) |

| Gestation week, median (range) | 20 (10, 35) |

| Alpha-adrenergic blockade | 104 (42.1%) |

| Duration, weeks, median (range) | 8 (0, 40) |

| Type of deliverya | |

| Caesarean section | 146 (58.6%) |

| Gestation week, median (range) | 36 (25, 41) |

| Vaginal | 76 (30.5%) |

| Gestation week, median (range) | 38 (28, 41) |

| Unknown, live birth | 3 (1.2%) |

| Gestation week, median (range) | 38 (36, 39) |

| Emergent Induced Vaginal | 1 (0.4%) |

| Gestation week | 20 |

| Elective abortion | 8 (3.2%) |

| Gestation week, median (range) | 9 (3, 22) |

| Miscarriage/intrauterine fetal loss | 11 (4.4%) |

| Gestation week, median (range) | 18 (8, 37) |

| Still in pregnancy | 2 (0.8%) |

| Gestation week | 25,26 |

| Autopsy | 2 (0.8%) |

| Gestation week | 28, unknown |

| Maternal adverse outcomes related to catecholamine excess (n=230)c | |

| Death related to catecholamine excess | 3 (1.3%) |

| Severe cardiac complications related to catecholamine excess | 15 (6.5%) |

| No complications | 212 (92.2%) |

| Fetal adverse outcomes related to catecholamine excess (n=230)c | |

| Death related to catecholamine excess | 20 (8.7%) |

| No complications related to catecholamine excess | 210 (91.3%) |

Reported for each pregnancy

Several categories have missing data, number indicates number of patients with available data

Reported for each pregnancy, after excluding nonfunctioning PPGL, pregnancies terminated through elective abortion, and ongoing pregnancies

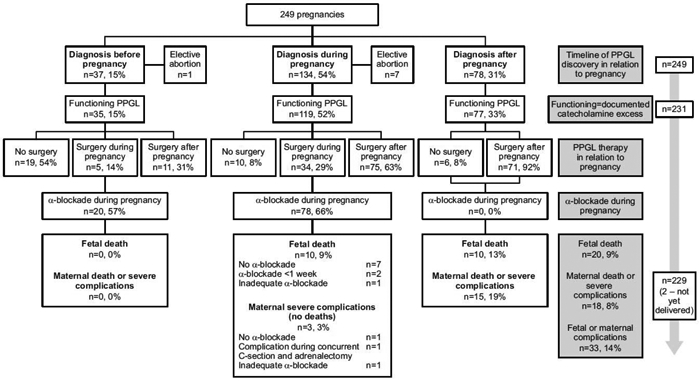

Fig. 1: Pregnancy in patients with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PPGL) based on the time of discovery.

Timeline of PPGL discovery in relation to pregnancy: Of 249 pregnancies, PPGL was discovered before pregnancy in 37 (15%) cases, during pregnancy in 134 (54%) cases, and after pregnancy in 78 (31%) cases. Elective abortion was performed in 8 cases.

Functioning=documented catecholamine excess: Of the remaining 241 cases, PPGL was functioning in 231 cases.

PPGL therapy in relation to pregnancy: Cases are stratified based on whether surgery was performed during or after pregnancy, or never performed ( no surgery).

a-blockade during pregnancy: proportion of cases where a-blockade was used during pregnancy is reported.

Last row represent fetal and maternal complications.

Elective pregnancy termination was performed in 8 (3%) patients at a median of 9 weeks (range 3-22), all in women with recognized PPGL before or during pregnancy. Miscarriage/intrauterine fetal loss occurred in 11 (4%) patients at a median of 18 weeks of gestation (range, 8-37), in 6 women with unrecognized PPGL during pregnancy and in 5 women who were discovered with PPGL within a median of 2 (0-10) weeks before pregnancy loss. Two pregnancies (0.7%) were confirmed at autopsy. Two women have not yet delivered at the time of the manuscript submission. Of the remaining 226 pregnancies, 168 (74%) were carried to term (>36 weeks of gestation) and delivered by C- section (94, 56%), vaginal delivery (71, 42%), and an unknown mode of delivery (3, 2%). An additional 58 (26%) pregnancies delivered pre-term (median gestation week of 32 (range, 20-35)) through C-section (52, 90%) and vaginal delivery (6, 10%). Seven fetal deaths occurred during or shortly after delivery (6 in pre-term deliveries, and 1 at term delivery). In patients with PPGL diagnosed before or during pregnancy, C-section was more common if symptoms of catecholamine excess (86% vs 64% for vaginal delivery, p=0.014), and if higher degree of catecholamine excess (catecholamine level>10 times upper limit of normal in 52% vs 13% for vaginal delivery, p=0.002), (Appendix Table 8).

PPGL therapy and follow up

Patients were treated with surgery (203, 88%) or other therapies/observation (29, 12%). Of 42 (18%) patients who underwent removal of PPGL antepartum, 40 had functioning PPGL, treated with surgery at a median gestation week of 20 (range, 10-35) (Table 1). PPGL surgery during pregnancy was performed with alpha-adrenergic blockade in 33 of 40 (83%) patients with functioning PPGL [median duration of alpha-adrenergic blockade was 4 weeks (range, 0.1-21)]. In 161 (70%) patients, surgery for PPGL was performed after delivery at a median of 8 weeks postpartum (range, 0-224). The remaining 29 unoperated patients were treated with postpartum iodine-131 metaiodobenzylguanidine therapy (131I-MIBG), lutetium-177-labeled somatostatin analogue, external radiation therapy or they were observed.

Factors associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes

Pregnancy-related maternal and fetal outcomes were analyzed for 230 (92%) pregnancies (excluded: 8 elective terminations, 1 ongoing pregnancy managed without antepartum surgery, and 10 patients with non-functioning PPGL). Maternal and/or fetal complications of catecholamine excess were observed in 33(14%) pregnancies: fetal death in 15 (7%) pregnancies, severe maternal complications or death in 13 (6%) pregnancies, or both maternal and fetal complications in 5 (2%) pregnancies. Several women had long-term sequelae from the catecholamine related complications, including residual neurologic deficits (Appendix Table 9).

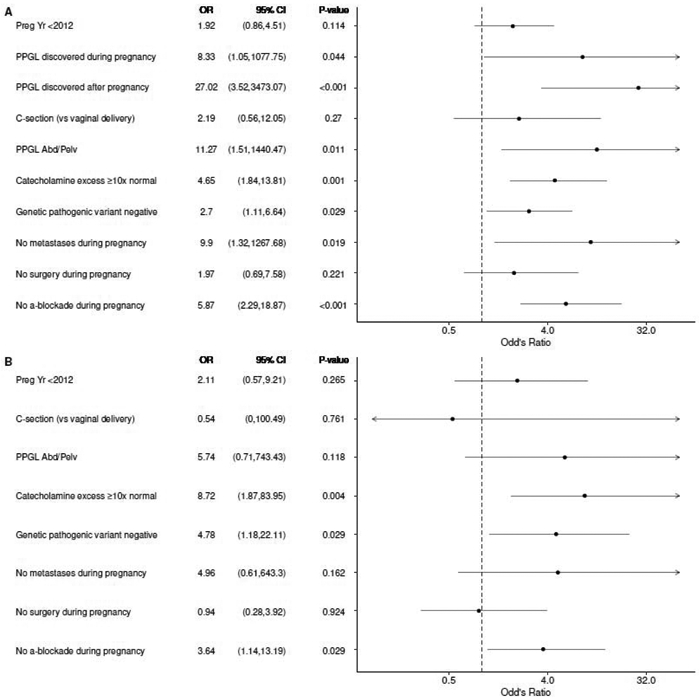

All adverse outcomes occurred in patients with functioning PPGL diagnosed during or after pregnancy (Table 3, Figure 1). In contrast, no complications occurred in patients diagnosed with PPGL prior to pregnancy, possibly due to lower degree of catecholamine excess (Appendix Table 10). Unrecognized PPGL during pregnancy was strongly associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes (OR 27.0; 95%CI 3.5-3128.0 for PPGL diagnosis after vs before pregnancy, Figure 2, Appendix Table 11). PPGL location (abdominal/pelvic vs other) also was associated with adverse outcomes (OR 11.3; 95%CI 21.51441.0). In a subset of patients where the actual catecholamine/metanephrine level was documented, a level ≥10 times the upper limit of normal range was associated with adverse outcomes (OR of 4.7; 95%CI 1.8-13.8). For patients diagnosed antepartum, alpha-adrenergic blockade therapy for at least 2 weeks prevented adverse outcomes (OR 3.6; 95%CI 1.1-13.2, for no alpha blockade vs alpha blockade). Antepartum surgery was not associated with better outcomes (Figure 2). Of 39 patients with functioning PGL treated with antepartum surgery, 3 (8%) adverse outcomes occurred (2 fetal deaths and 1 severe cardiovascular maternal complication). Maternal age, year of pregnancy, tumor size, or type of delivery were not associated with better outcomes (Table 3, Figure 2). Patients with known PPGL syndrome/positive pathogenic variants and those with metastatic disease were less likely to develop an adverse outcome (Figure 2, Appendix Table 11,12).

Table 3:

Factors associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnancy associated with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PPGL)

| Variable | No Complication (N=197) |

Complication/Death (N=33) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Pregnancy | |||

| Years, median (range) | 29 (15, 46) | 29 (19, 40) | 0.403 |

| Year of Pregnancy (n=195) | 0.043 | ||

| Median (range) | 2012 (1980-2019) | 2006 (1982-2019) | |

| Time of PPGL discovery in relation to pregnancy | |||

| Before pregnancy | 35 (17.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | < 0.001 |

| During pregnancy | 106 (53.8%) | 12 (36.4%) | |

| Gestation week, median (range) | 26 (6,38) | 25 (10,28) | |

| After pregnancy | 56 (28.4%) | 21 (63.6%) | |

| Location of PPGL | |||

| Abdominal or pelvic | 169 (85.8%) | 33 (100.0%) | 0.021 |

| Other locations | 28 (14.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Time of delivery or miscarriage (n=228) | |||

| <32 weeks | 15 (7.7%) | 19 (59.4%) | < 0.001 |

| >32 weeks | 181 (92.3%) | 13 (40.6%) | |

| Type of delivery in term pregnancies (n=156) | |||

| Vaginal | 62 (42.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0.237 |

| Caesarean section | 85 (57.8%) | 7 (77.8%) | |

| Tumor size (n=186) | 0.669 | ||

| mm, median (range) | 51 (13, 310) | 51 (20, 158) | |

| Level of catecholamine excess (n=187) | |||

| 2x upper limit of normal | 33 (20.4%) | 2 (8.0%) | 0.003 |

| 5x upper limit of normal | 31 (19.1%) | 2 (8.0%) | |

| 10x upper limit of normal | 26 (16.0%) | 1 (4.0%) | |

| 10x upper limit of normal | 72 (44.4%) | 20 (80.0%) | |

| Metastases present during pregnancy | |||

| No | 172 (86.8%) | 33 (100.0%) | 0.03 |

| Yes | 25 (12.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Positive for genetic disease (n=149) | |||

| No | 36 (28.6%) | 12 (52.2%) | 0.026 |

| Yes | 90 (71.4%) | 11 (47.8%) |

Fig. 2: Factors associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

Panel A demonstrates factors associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes in all pregnancies and functioning PPGL (n=232) and Panel B demonstrates factors associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnancies with PPGL diagnosed before or during pregnancy (n=141). Year of pregnancy (<2012 vs >2012), time of PPGL discovery, type of delivery (caesarian, C-section vs vaginal delivery), location of PPGL ( abdominal/pelvic vs other locations), level of catecholamine excess (>10 times higher than normal vs other), genetic pathogenic variant (negative vs positive), metastatic PPGL (vs non-metastatic), surgery during pregnancy (vs no surgery), and use of alpha--adrenergic blockade during pregnancy (vs no alpha-blockade) were the variables analyzed.

Interpretation

In this large international multicenter study and systematic review, we describe the presentation, management and outcomes of women with PPGL during pregnancy. Overall, we found that both maternal and fetal outcomes were excellent when catecholamine excess was treated. However, several severe and even fatal events occurred, mainly in patients with unrecognized PPGL.

We found that severe maternal complications of catecholamine excess and maternal death occurred in 7% and 1 % of pregnancies with a concomitant untreated functioning PPGL, respectively. In contrast, a review of the literature summarizing 89 cases and published in 1971 reported a much higher maternal mortality of 48%(28). Subsequently, several reviews described lower rates of maternal death of 5-17%(10, 29, 30), with the only systematic review from 2013 reporting a rate of maternal death of 8%(31), which was still higher than what we found in our study (1%), possibly representing a publication bias. Similarly, we found an overall fetal mortality of 9% (including miscarriage, intrauterine fetal loss, and death at delivery), whereas it was 54% in the older study from 1971(28), 14-26% in subsequent studies(10, 29, 30), and 17% in the systematic review from 2013(31). Notably, all previous studies were case reports, small case series, or reviews of literature. In addition to the selection and publication biases contributing to higher rates of adverse outcomes in previous studies, the decrease in both maternal and fetal adverse outcomes likely reflects the overall improvement in obstetric care, surgical expertise, and advances in anesthesia care, and also higher rate of PPGL discovery based on presymptomatic case detection or incidental diagnosis on imaging, and availability of alpha-adrenergic blockade(4, 18, 21, 32).

Adverse outcomes occurred at a higher rate in patients with abdominal or pelvic PPGL, possibly due to compression of tumor by the gravid uterus or the higher degree of catecholamine release in patients with abdominal or pelvic PPGL. However, tumor size was not associated with a higher rate of complications at delivery in patients with pregnancies carried to term. Type of delivery was not associated with adverse outcomes, however C-section was two-times more common and usually reserved for patients with higher degree of catecholamine excess. While it is difficult to make a specific recommendation for the type of delivery our data suggest that natural labor may be safe in an appropriately selected patients with PPGL.

Adverse outcomes occurred in 8% of pregnancies when antepartum surgery for PPGL was performed. Notably, antepartum surgery was not associated with better outcomes. Therefore, the choice of intervention during pregnancy depends on the availability of surgical expertise, particularities of the PPGL disease, the trimester of gestation, and anticipated tolerance and compliance with medical therapy.

Surprisingly, we found that patients with metastatic PPGL experienced no pregnancy-related cardiovascular adverse outcomes of catecholamine excess. As we previously reported, many patients with metastatic PPGL demonstrate indolent course of disease(33, 34). Absence of fatal or severe cardiovascular adverse events of catecholamine excess in our cohort of patients with metastatic PPGL was likely partly related to the indolent nature of PPGL disease in patients choosing to become pregnant including a lower burden of disease and lower degree of catecholamine secretion. In addition, patients with metastatic disease are more likely to be aggressively monitored - allowing for an ample time for planning PPGL management before and during pregnancy. Indeed, as we show in our data, most patients with metastatic PPGL were diagnosed with PPGL prior to pregnancy (Appendix Table 10). Notably, in one patient with metastatic PPGL management was difficult, and required hospitalization (Appendix Table 9).

We also observed that patients with a known syndromic PPGL had lower rates of adverse outcomes, possibly due to earlier diagnoses of PPGL during pregnancy. PPGL in a young woman of childbearing age is more likely to be related to a predisposing germline pathogenic variant(2). Indeed, we found that of patients tested, 66% carried a predisposing pathogenic variant. Thus, it is imperative for syndromic carriers to undergo clinical, radiological, and biochemical evaluation for a possible PPGL before planning a pregnancy.

When the diagnosis of PPGL was made before or during pregnancy, medical management with alpha-adrenergic blockade was associated with excellent outcomes. Optimal alpha-adrenergic blockade and compliance are likely the factors that contributed to favorable outcomes, though given the retrospective design, this was difficult to assess. Our data do not allow us to conclude on the dose and type of alpha-adrenergic blockers that should be used. It is reasonable to choose either a nonselective alpha-adrenergic blocker (eg, phenoxybenzamine) or an alpha1–selective shorter-acting alpha-adrenergic blocker (eg, doxazosin) and individualize the dose with the goal of sufficient alpha-adrenergic blockade to prevent hypertension during pregnancy. Intensification of alpha-adrenergic blockade one week prior to surgery or vaginal delivery could be considered.

The main strength of this study is that it represents the largest cohort known of pregnant women with PPGL. We also systematically searched multiple databases and obtained published data on individual patients not included in the registry, therefore, presenting the most complete evidence base to date and providing more generalizable inferences. To address potential differences in outcomes of patients enrolled through the multicenter collaboration versus patients from the systematic review of literature, we performed a subgroup analysis which demonstrated similar rates of adverse fetal and maternal outcomes (Appendix Table 13). Limitations of our study include the retrospective design, inclusion of convenience sample of patients, non-systematic reporting of data, selection, and information bias; however, a prospective study on PPGL in pregnancy is not feasible due to the rarity of disease, especially in young women. We were not able to ascertain or adjust for all potential confounders. Several important variables had missing data, and sample size for certain analyses was small. To address potential differences in outcomes of centers enrolling systematically (electronic search of databases) versus centers with non-systematic enrollment, we performed a subgroup analysis which demonstrated similar rates of adverse maternal outcomes, but lower rates of adverse fetal outcomes in centers enrolling non-systematically, possibly due to more recent period of enrollment (Appendix Table 14). The period of enrollment for this study spans several decades during which significant advances both in obstetric care and understanding of PPGL occurred. However, subgroup analysis of patients diagnosed in the first 20 years of the study has not identified significant differences when compared to patients treated in the last 20 years of the study (Appendix Table 15). Given the differences in assays and change of assays over time, comparison of catecholamine excess assessment was not possible. Geographic differences in the approaches to PPGL and pregnancy care, as well as higher PPGL expertise of participating centers may have influenced the results of this study. Given the international design of this study, the findings of this study are likely generalizable to most tertiary centers in the world, but not to community settings. Lastly, selection, publication and reporting bias are clearly concerning in a body of evidence that consists of case series, and estimates provided in this study may not have valid denominators.

In conclusion, the majority of pregnancies in women with PPGLs had excellent outcomes, even in women with metastatic or functional disease. PPGL diagnosed before or during pregnancy allowed for appropriate management, which likely improved maternal and fetal outcomes. PPGL surgery during pregnancy was in general safe, but was not associated with favorable outcomes, and medical management with alpha-adrenergic blockade alone during pregnancy can be considered. In contrast, unrecognized and untreated PPGL was associated with a 27-times higher risk of either maternal or fetal complications. Thus, we recommend biochemical and/or imaging evaluation for PPGL in patients with high suspicion of disease, ideally prior to conception or as soon as pregnancy is confirmed. Suspicion for PPGL should be high in those patients with a positive family history of PPGL or those who carry a PPGL susceptibility gene.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

We screened PubMed for studies on the epidemiology of adrenal tumors, using the terms “pheochromocytoma”, “paraganglioma”, “phaeochromocytoma”, or “adrenal mass” combined with “pregnancy”, “pregnancy complication”, or “pregnancy outcome”. We considered all studies published before December 27th, 2019, in any language. The majority of previous studies were case reports, relatively small studies from endocrine referral centers of <10 cases, or narrative reviews. Reviews of case reports and small case series summarized overall decreasing rates of maternal and fetal death over the years, and provide very scarce data on non-fatal maternal complications.

Added value of this study

This is a large retrospective study of 197 patients with pheochromocytoma and/or paraganglioma (PPGL) and pregnancy enrolled through an international multi-center collaboration of 25 countries and 52 patients from the systematic review of literature published between 2005 and 2019. The large sample size of our cohort allowed us to identify factors associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes in women with PPGL and pregnancy, and characterize the association between the known genetic predisposition, metastatic disease, antepartum medical and surgical management, degree of catecholamine excess, and the location of the tumor with the adverse outcomes.

Implications of all the available evidence

We found that severe maternal complications of catecholamine excess, maternal, or fetal death occurred in 14% of pregnancies, all with a concomitant unrecognized or suboptimally treated functioning PPGL. We showed that adverse outcomes occurred at a higher rate in patients with abdominal or pelvic PPGL and in patients with a higher degree of catecholamine excess. Alpha-adrenergic blockade therapy was associated with better outcomes. We found that patients with metastatic PPGL experienced no pregnancy-related cardiovascular adverse outcomes of catecholamine excess. We did not find that antepartum surgery was associated with better outcomes. Based on our findings, we recommend evaluation for PPGL prior to conception or as soon as possible during pregnancy in women with known predisposing germline pathogenic variants or who may be carriers of a heritable PPGL disorder. Alpha-adrenergic blockade therapy alone can be considered in women diagnosed with PPGL during pregnancy.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Catalyst Award for Advancing in Academics from Mayo Clinic (to Irina Bancos), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) USA under award K23DK121888 (to Irina Bancos). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIH. Prof. Eng is an ACS Clinical Research Professor, and the Sondra J. and Stephen R. Hardis Endowed Chair in Cancer Genomic Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Role of Funding Source

The sponsors had no role in designing the study, in collecting, analyzing or interpreting the data, or in writing the report. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Appendix

Marina Yukina, Debbie L Cohen, Steven G Waguespack, Maria Adelaide Albergaria Pereira, Xin He, Tushar Bandgar, Gianluca Donatini, Xiao-Ping Qi, Aviva Cohn, Anna Roslyakova, Claudio Letizia, Lauren Fishbein, Ravinder Jeet Kaur, Nicole Iniguez-Ariza, Mohammad H Murad, Lucinda Gruber, Heather Wachtel, Sergiy Cherenko, Camilo Jimenez, Tobias Else, Swati Ramteke-Jadhav, Xu-Dong Fang, Anand Vaidya, Luigi Petramala, Dmitry Beltsevich, Martin K Walz, Eleonora P M Corssmit, Nelson Wohllk, Nicola Tufton, Thera P Links, Alfonso Massimiliano Ferrara, Uliana Tsoy, Diane Donegan, Mariola Peczkowska, Henri J Timmers, Valentina Morelli, Andreas Ebbehoj, Lawrence S Kirschner, Tada Kunavisarut, Catharina Larsson, Inna Kudlai, Kornelia Hasse-Lazar, Marcin Barczyński, Timo Deutschbein, Katharina Langton, Åse Krogh Rasmussen, Sarka Dvorakova, Julie A Miller, Longfei Liu, Bonita Bennett, Ya-Sheng Huang, Zhi-Xian Yu, Sanjeet Kumar Jaiswal, Nalini Shah, Rene E Diaz, Robin P F Dullaart, Scott A Akker, William M Drake, Francesca Boaretto, Stefania Zovato, Giovanni Barbon, Elisa Taschin, Francesca Schiavi, Elena Grineva, Maximilien Rappaport, Paul Skierczynski, Martin Fassnacht, Jan Calissendorff, C Christofer Juhlin, Petr Vlĕek, Minghao Li, Eric Jonasch, Larry Prokop, Milan Jovanovic, Ronald M Lechan, Feyza Erenler, Vishnu Garla, Maryna Bobryk, Andrey Y Kovalenko, Emma Hodson, Bernadette Jenner, Helen L Simpson, Ruth T Casey, Oliver Gimm, Joanne Ngeow Yuen Yie, Zulfiya Shafigullina, Maria João Martins Bugalho, Silvia Rizzati, Merav Fraenkel, Mark Sherlock, Dipti Sarma, Uma Kaimal Saikia, Anna Riester, Marcus Quinkler, Stefan Zschiedrich, Jochen Seufert, Birke Bausch, Nino Zavrashvili, Esben Søndergaard, Jes Sloth Mathiesen, Maciej G Robaczyk, Per Løgstrup Poulsen, Volha Vasilkova, Flavia A Costa-Barbosa, Claudio E Kater, Ilgin Yildirim Simsir, M Umit Ugurlu, Utku E Soyaltin, Özer Makay, Nikita V Ivanov, Giuseppe Opocher, Viacheslav I Egorov, Roman Petrov, Natalia V Khudiakova

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

Dr. Bancos reports advisory board participation with Corcept, CinCor, and HRA Pharma outside the submitted work. Dr. Vaidya reports consulting for Corcept, HRA Pharma, and CatalysPacific, and research grants from National Institutes of Health and Ventus Charitable Foundation, all unrelated to the submitted work

Data Sharing Statement

Statistical code and de-identified data sets are available upon request.

References

- 1.Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr., Eng C. Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(6):552–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishbein L, Merrill S, Fraker DL, Cohen DL, Nathanson KL. Inherited mutations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: why all patients should be offered genetic testing. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(5):1444–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann HP, Young WF Jr., Krauss T, Bayley JP, Schiavi F, Opocher G, et al. 65 YEARS OF THE DOUBLE HELIX: Genetics informs precision practice in the diagnosis and management of pheochromocytoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(8):T201–T19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruber LM, Hartman RP, Thompson GB, McKenzie TJ, Lyden ML, Dy BM, et al. Pheochromocytoma Characteristics and Behavior Differ Depending on Method of Discovery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1386–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donatini G, Kraimps JL, Caillard C, Mirallie E, Pierre F, De Calan L, et al. Pheochromocytoma diagnosed during pregnancy: lessons learned from a series of ten patients. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(9):3890–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huddle KR. Phaeochromocytoma in black South Africans - a 30-year audit. S Afr Med J. 2011;101(3):184–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliva R, Angelos P, Kaplan E, Bakris G. Pheochromocytoma in pregnancy: a case series and review. Hypertension. 2010;55(3):600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salazar-Vega JL, Levin G, Sanso G, Vieites A, Gomez R, Barontini M. Pheochromocytoma associated with pregnancy: unexpected favourable outcome in patients diagnosed after delivery. J Hypertens. 2014;32(7):1458–63; discussion 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Weerd K, van Noord C, Loeve M, Knapen M, Visser W, de Herder WW, et al. ENDOCRINOLOGY IN PREGNANCY: Pheochromocytoma in pregnancy: case series and review of literature. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(2):R49–R58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harper MA, Murnaghan GA, Kennedy L, Hadden DR, Atkinson AB. Phaeochromocytoma in pregnancy. Five cases and a review of the literature. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96(5):594–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salazar-Vega JL, Levin G, Sanso G, Vieites A, Gomez R, Barontini M. Pheochromocytoma associated with pregnancy: unexpected favourable outcome in patients diagnosed after delivery. J Hypertens. 2014;32(7):1458–63; discussion 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song Y, Liu J, Li H, Zeng Z, Bian X, Wang S. Outcomes of concurrent Caesarean delivery and pheochromocytoma resection in late pregnancy. Intern Med J. 2013;43(5):588–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wing LA, Conaglen JV, Meyer-Rochow GY, Elston MS. Paraganglioma in Pregnancy: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(8):3202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bausch B, Schiavi F, Ni Y, Welander J, Patocs A, Ngeow J, et al. Clinical Characterization of the Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma Susceptibility Genes SDHA, TMEM127, MAX, and SDHAF2 for Gene-Informed Prevention. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):1204–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castinetti F, Qi XP, Walz MK, Maia AL, Sanso G, Peczkowska M, et al. Outcomes of adrenal-sparing surgery or total adrenalectomy in phaeochromocytoma associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: an international retrospective population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(6):648–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Q, Bancos I, Gruber LM, Bancos C, McKenzie TJ, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, et al. When Biochemical Phenotype Predicts Genotype: Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Am J Med. 2018;131(5):506–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brito JP, Asi N, Bancos I, Gionfriddo MR, Zeballos-Palacios CL, Leppin AL, et al. Testing for germline mutations in sporadic pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma: a systematic review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;82(3):338–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butz JJ, Weingarten TN, Cavalcante AN, Bancos I, Young WF Jr., McKenzie TJ, et al. Perioperative hemodynamics and outcomes of patients on metyrosine undergoing resection of pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma. Int J Surg. 2017;46:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butz JJ, Yan Q, McKenzie TJ, Weingarten TN, Cavalcante AN, Bancos I, et al. Perioperative outcomes of syndromic paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma resection in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, or neurofibromatosis type 1. Surgery. 2017;162(6):1259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canu L, Van Hemert JAW, Kerstens MN, Hartman RP, Khanna A, Kraljevic I, et al. CT Characteristics of Pheochromocytoma: Relevance for the Evaluation of Adrenal Incidentaloma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(2):312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weingarten TN, Welch TL, Moore TL, Walters GF, Whipple JL, Cavalcante A, et al. Preoperative Levels of Catecholamines and Metanephrines and Intraoperative Hemodynamics of Patients Undergoing Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma Resection. Urology. 2017;100:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin JS, Murad MH, Leas B, Treadwell JR, Chou R, Ivlev I, et al. A Narrative Review and Proposed Framework for Using Health System Data with Systematic Reviews to Support Decision-making. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1830–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23(2):60–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bausch B, Wellner U, Bausch D, Schiavi F, Barontini M, Sanso G, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with pediatric pheochromocytoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krauss T, Ferrara AM, Links TP, Wellner U, Bancos I, Kvachenyuk A, et al. Preventive medicine of von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(9):783–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: neurofibromatosis. Bethesda, Md., USA, July 13-15, 1987. Neurofibromatosis. 1988;1(3):172–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: 2019. [Available from: https://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schenker JG, Chowers I. Pheochromocytoma and pregnancy. Review of 89 cases. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1971;26(11):739–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahlawat SK, Jain S, Kumari S, Varma S, Sharma BK. Pheochromocytoma associated with pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1999;54(11):728–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mannelli M, Bemporad D. Diagnosis and management of pheochromocytoma during pregnancy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2002;25(6):567–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biggar MA, Lennard TW. Systematic review of phaeochromocytoma in pregnancy. Br J Surg. 2013;100(2):182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumann HPH, Tsoy U, Bancos I, Amodru V, Walz MK, Tirosh A, et al. Comparison of Pheochromocytoma-Specific Morbidity and Mortality Among Adults With Bilateral Pheochromocytomas Undergoing Total Adrenalectomy vs Cortical-Sparing Adrenalectomy. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamidi O, Young WF Jr., Gruber L, Smestad J, Yan Q, Ponce OJ, et al. Outcomes of patients with metastatic phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;87(5):440–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamidi O, Young WF Jr., Iniguez-Ariza NM, Kittah NE, Gruber L, Bancos C, et al. Malignant Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma: 272 Patients Over 55 Years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(9):3296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.