Abstract

Silica flour is one of the most commonly used material in cementing oil wells at high-temperature conditions of above 230 °F to prevent the deterioration in the strength of the cement. In this study, replacement of the silica flour with the granite waste material at which an inexpensive and readily available material in cementing oil-wells is evaluated. Four cement samples with various amounts of silica flour and granite powder were prepared in this work. The effect of including the granite waste instead of silica flour in the cement elastic, failure, and petrophysical properties after curing the samples at 292 °F and 3000 psi was examined. The results revealed that replacement of the silica flour with 40% by weight of cement (BWOC) optimized the cement performance and confirmed that this concentration of granite could be used as an alternative to the silica flour in oil-well cementing. This concertation of granite slightly improved the elastic properties of the cement. It also improved the cement compressive and tensile strengths by 5.7 and 39.3%, respectively, compared to when silica flour is used. Replacement of the silica flour with 40% BWOC of granite waste also reduced the cement permeability by 64.7% and porosity by 17.9%.

1. Introduction

Cementing operation is very essential after wellbore drilling,1 wherein the cement slurry is injected to fill the annular space between the casing and the drilled formation.2 Cementing is a critical process during the construction of well. It has several functions such as isolating the formations by providing a hydraulic seal that prevents the fluids escaping from the surface, anchoring the wellbore casing,3 protecting the casing from corrosion, and keeping the formation pressure under control.4 Therefore, to accomplish the highest potential of well production, well cementing must be performed properly to avoid any well integrity issues.5

Designing the cement involves various materials and additives that are compatible with others and able to provide the cement slurry and the formed cement matrix with the desired properties. Silica flour is one of the commonly used materials in oil-well cementing.6 It is very fine silica sand that contains a highly pure and high content of silica (more than 98%). The main purpose of using silica flour in well cementing is to increase the cement matrix strength and to reduce its the permeability of the cement especially at high-temperature conditions,7−9 and it is highly recommended to be used under high-temperature conditions (greater than 230 °F) because above this temperature, the cement strength starts to weaken.

Laboratory experiments are needed to select the optimum cement composition to provide the cement sheath with excellent properties.10 Several recent studies were conducted to enhance the cement properties using different materials such as olive waste,11 polypropelene fibers,12,13 tire waste,14 nanoclay,15,16 rice husk ash,17 nanosilica,18 laponite,19 metakaolin,20 sugar cane biomass waste,21 and cellulose nanofibers.22

Those materials that can be used in cementing operations include the industrial waste. These wastes could cause numerous issues to the human and the environment when discarded in an unseemly way.23 Additionally, transportation and disposing of these wastes cost their industries a lot of money.24 Subsequently, scientists have searched for decisions to incorporate these wastes in other industrial operations, to reduce the expenses and the environmental problem created by disposing them in inappropriate ways.25 Therefore, it is very encouraged to use waste materials in well cementing operations.

The granite coarse aggregate that could be used in self-compacting high-performance concretes has good strength properties; however, because it is highly costly, granite coarse aggregate is only used if it is necessary. Therefore, possibility of using the granite waste material by reusing readily stored waste could be significant in decreasing the costs of its reproduction and increasing its use as a ready aggregate additive for high-performance cement and concrete.26

Granite waste is an industrial waste produced from granite crushing in the industry of granite polishing. It has similar properties of pozzolanic materials such as fly ash and silica fume.27 The waste of granite is produced through several processes, starting by cutting and polishing the blocks of granite, which produce a powder that executed with water where this water is kept inside tanks.28 When the water is evaporated, the remained sludge of granite is carried and discarded randomly since it is considered as a waste material.29

Granite waste was applied in concrete industry by several authors.26,30,31 Abd Elmoaty32 studied the alteration of the corrosion resistance and mechanical properties of the granite waste-based concrete. Sharma et al.33 evaluated the alteration of the compressive and tensile strengths, pull-off strength, and depth of abrasion for concrete prepared with different concentrations of granite waste. Vijayalakshmi et al.34 investigated the changes in the durability and strength of the granite waste-based concrete.

The use of granite waste in oil-well cementing was suggested by Moura et al.35 The effect of different concentrations of the granite waste material (10, 15, and 20%) on the rheology of the cement under two temperature conditions of 80 and 102 °F was investigated. As an outcome, they concluded that the rheological properties of the cement including up to 20% of granite waste was acceptable.

The aim of this research is to evaluate the prospect of utilizing the granite waste as a replacement of silica flour in cementing oil-well at 3000 psi and 292 °F. The impacts of this replacement on the cement elastic, failure, and petrophysical properties were assessed.

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Materials

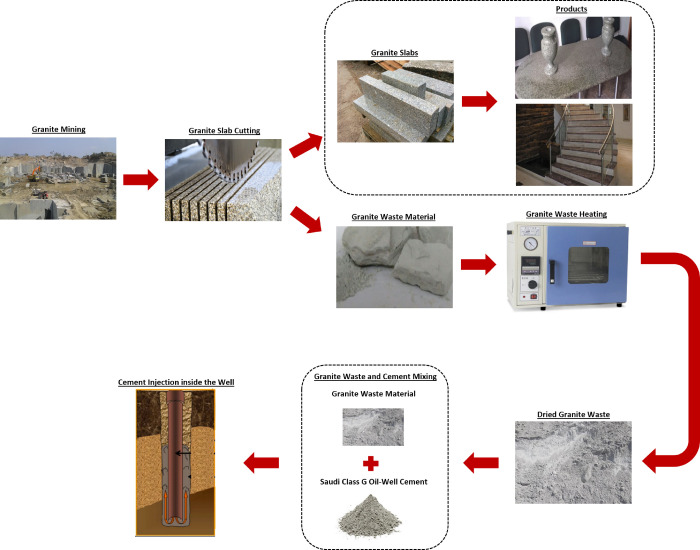

The used materials in this work are Saudi Class G cement, silica flour, and granite industrial waste material. The used cement and silica flour were supplied by a service company while the granite waste material was produced from granite cutting in the industry of granite polishing, as shown in Figure 1. As indicated in Figure 1, after granite mining, slabs of granite are required to be prepared, which will then be used for making different useful products. During slabs cutting, huge amount of a granite waste powder will be produced, which currently is not in use, this powder makes great environmental problems; in this study, the powder was then dried for in the heating oven, and this powder was then mixed with the cement slurry instead of the silica flour.

Figure 1.

Granite waste material production, processing, and mixing with the well cementing.

The composition of the cement, silica flour, and granite waste as characterized by the XRF technique is shown in Table 1. The XRF results indicates that Saudi Class G cement is mainly composed of Ca (72.0%) where both silica flour and granite waste have low Ca concentration of 1.79 and 2.62%, respectively. XRF results also shows that Si is the main element of silica flour and granite waste, which contain 97.2 and 54.6% of Si, respectively, while only 12.1% of Si is present in the cement.

Table 1. XRF Characterization for the Elemental Composition of Class G Cement, Silica Flour, and Granite Waste.

| spectrum | concentration, wt % |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| cement | silica flour | granite waste | |

| Na | 0.05 | 4.15 | |

| Mg | 1.33 | 0.03 | |

| Al | 2.37 | 0.47 | 9.35 |

| Si | 12.1 | 97.2 | 54.6 |

| P | 0.17 | ||

| S | 2.43 | 0.04 | 0.56 |

| K | 19.5 | ||

| Ca | 72.1 | 1.79 | 2.62 |

| Ti | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.31 |

| Cr | 0.01 | ||

| Fe | 9.08 | 0.21 | 8.68 |

| Ni | 0.02 | ||

| Cu | 0.04 | ||

| Zn | 0.04 | ||

| Mn | 0.06 | 0.07 | |

| Sr | 0.15 | 0.02 | |

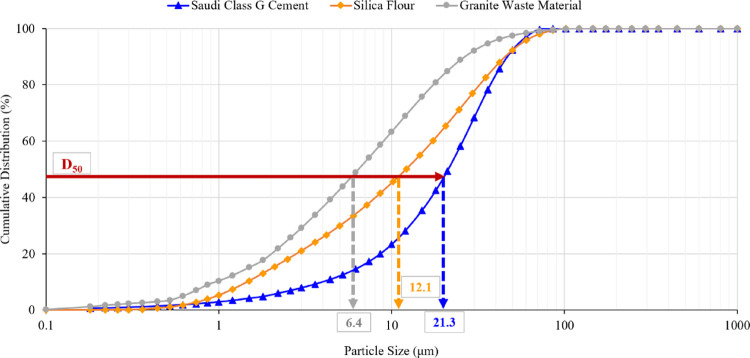

To compare the particle size of the materials used, the particle size distribution (PSD) analysis was performed. The results showed that 50% of the particles (D50) of Saudi Class G cement is less than 21.3 μm in size as shown in Figure 2, while D50 of silica flour and granite waste material are less than 12.1 and 6.4 μm, respectively. This result confirms that the size of the granite particles is less than those of both silica flour and Saudi Class G cement. This property is important to enable pore filling of the formed cement matrix, which is required to densify the cement matrix, reduce its permeability, and increase its strength.36−38

Figure 2.

PSD of the cement, silica flour, and granite waste.

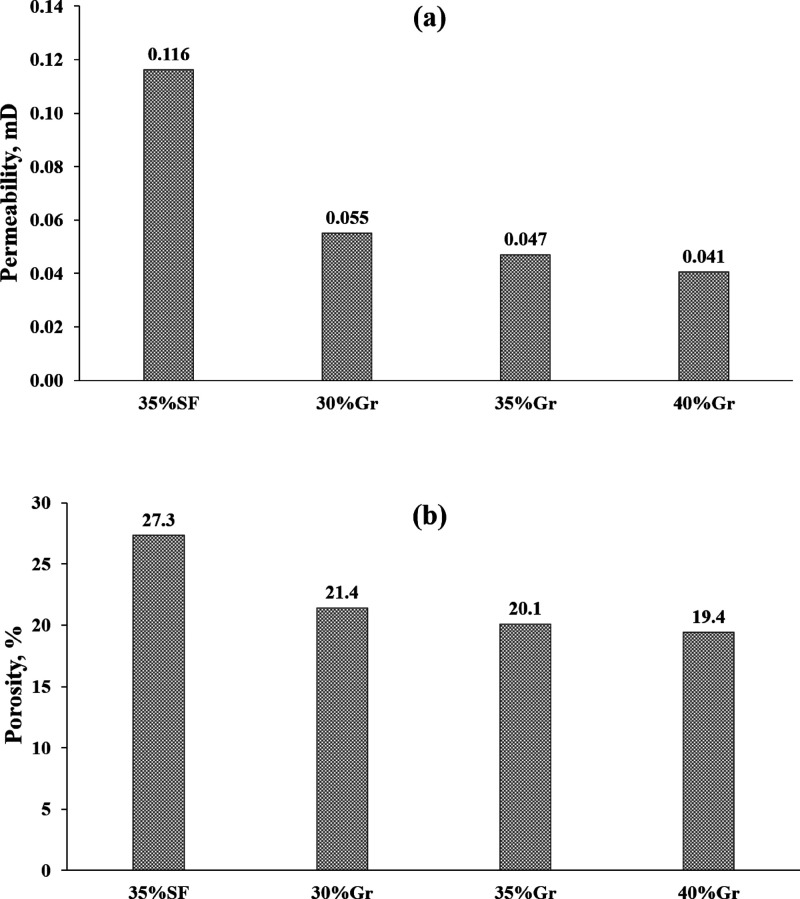

The granite waste particles were also imaged at high magnification in the scanning electron microscope (SEM). The SEM images in Figure 3 revealed that most of the granite waste particles have sharp edges with size of less than 10 μm, which is less than the D50 of the silica flour, this characteristic is important to improve the cement pore filling impact using the granite waste material. The ability of the granite waste powder to improve the cement pores filling effect is required to decrease the cement permeability, increase it is structure density, and therefore increase its strength.

Figure 3.

SEM images of the granite waste powder at (a) 50 μm and 500×, (b) 10 μm and 1000×, and (c) 5 μm and 5000×.

2.2. Methodology

The standards of the American Petroleum Institute (API)39,40 were followed in the preparation of four cement slurries that is shown in Table 2. The disparity between the prepared slurries is the silica flour (SF) content and the amount of granite waste used. All slurries prepared with 44% by weight of cement (BWOC) of water. The first slurry contains 35% BWOC of silica flour and no granite waste, and 35% of silica flour was considered as the base of comparison since it has been confirmed by the previous study that this concentration is the optimum to improve the cement properties at high-temperature conditions.41 The other slurries are prepared to have no silica flour and different concentrations of granite waste, where the second, third, and fourth slurries contain 30, 35, and 40% BWOC of granite, respectively.

Table 2. Concentration of Silica Flour and Granite Waste Material in the Different Cement Slurries.

| sample no. (ID) | silica flour (% BWOC) | granite waste material (% BWOC) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 (35% SF) | 35 | 0 | ||

| #2 (30% Gr) | 0 | 30 | ||

| #3 (35% Gr) | 0 | 35 | ||

| #4 (40% Gr) | 0 | 40 |

Cubical and cylindrical samples were prepared and cured for 1 day under a high pressure of 3000 psi and high temperature of 292 °F. Then, cement properties were evaluated using these samples.

2.2.1. Measurements of Elastic Parameters

Alteration of the elastic properties of the cement caused by replacing the silica flour with granite waste was studied. The compressional and shear waves were measured by the sonic method and used in calculating the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of cylindrical samples with a diameter of 1.5 in. and a length of 3 in.

2.2.2. Measurements of Failure Properties

The impacts of using the granite waste instead of the silica flour on the compressive and tensile strengths were examined for the cement samples. The American Society for Testing and Material (ASTM)42 standard was followed to evaluate the compressive strength for 2 in. cubical samples. The indirect tensile strength of cylindrical samples having a diameter of 1.5 in. and a thickness of 0.9 in. was measured using the Brazilian test.41

2.2.3. Measurements of Petrophysical Parameters

The effect of replacing silica flour by the granite waste on the permeability and porosity of the cylindrical cement samples were investigated. For the permeability, it was measured following the Hagen–Poiseuille law and the procedures explained by Sanjuán et al.43 For evaluating the porosity, the Boyle’s law44 was applied to find the porosity, as explained by Ahmed et al.45

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Elastic Parameters

Figure 4 illustrates the elastic properties of the used cement samples. As indicated in Figure 4a, Poisson’s ratio for the cement containing 35% SF is 0.265, and replacement of the silica flour with 30 and 35% BWOC of the granite waste material reduced Poisson’s ratio to 0.256 and 0.248, respectively. This decrease in Poisson’s ratio is not acceptable since it increases the cement expandability.46 Sample 40% Gr has a Poisson’s ratio of 0.266, which is almost similar to that of the silica flour.

Figure 4.

Results of Poisson’s ratio (a) and Young’s modulus (b) of the cement samples used in this work. Where 35% SF denotes the sample having 35% BWOC of silica flour, and 30% Gr, 35% Gr, and 40% Gr denote the samples with 30, 35, and 40% BWOC of granite.

Young’s modulus of sample 35% SF is 24.4 GPa, which increased to 25.3 and 26.0 GPa when the silica flour is replaced with 30 and 35% BWOC of granite waste in samples 30% Gr and 35% Gr, respectively, as indicated in Figure 4b. Replacement of the silica flour with 40% BWOC of granite reduced the cement Young’s modulus by 2.5% to reach 23.8 GPa, as indicated in Figure 4b. The reduction in the cement Young’s modulus improves the cement stability under shear stresses.46

3.2. Failure Properties

The effect of replacing the silica flour with granite waste on the compressive and tensile strengths were assessed, as depicted in Figure 5. The base sample (35% SF) which has 35% BWOC of silica flour and no granite has a compressive strength of approximately 58 MPa (Figure 5a) and tensile strength of 2.34 MPa (Figure 5b). Replacement of the silica flour with 30 and 35% BWOC of granite waste reduced the compressive and tensile strengths of the cement matrix. However, incorporation of 40% BWOC of the granite into sample 40% Gr increased both its compressive and tensile strength by 5.7 and 39.3% to reach 61.6 MPa (Figure 5a) and 3.26 MPa (Figure 5b), respectively.

Figure 5.

Compressive strength (a) and tensile strength (b) of all cement samples. Where 35% SF denotes the sample having 35% BWOC of silica flour, and 30% Gr, 35% Gr, and 40% Gr denote the samples with 30, 35, and 40% BWOC of granite.

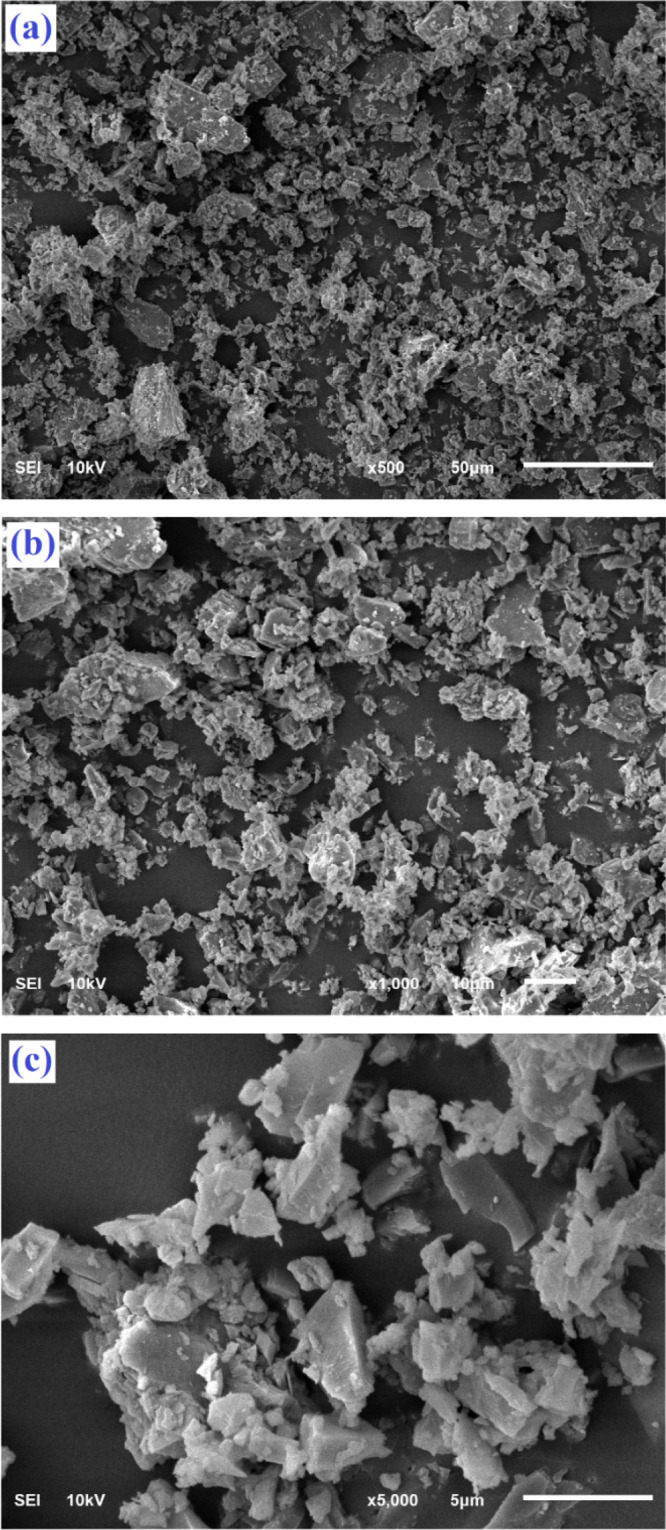

3.3. Petrophysical Parameters

The permeability and porosity of all cement samples were also examined. As illustrated in Figure 6, the 35% SF sample which incorporates 35% of the silica flour has the highest permeability and porosity of 0.116 mD and 27.3% compared with other samples. Replacement of the silica flour with a granite waste material showed a continuous reduction in the permeability and porosity of cement. Sample 40% Gr has the lowest permeability of 0.041 mD that is 64.7% less than that for sample 35% SF (Figure 6a), and the lowest porosity of 19.4%, which is 17.9% less than that for sample 35% SF (Figure 6b). The reduction in the permeability and porosity of cement after replacing the silica flour with granite is attributed to the pore filling effect of the granite waste material, which is characterized by pore size of less than both silica flour and Saudi Class G cement, as indicated earlier in Figure 2.

Figure 6.

(a) Permeability and (a) porosity of all cement samples. Where 35% SF denotes the sample having 35% BWOC of silica flour, and 30% Gr, 35% Gr, and 40%Gr denote the samples with 30, 35, and 40% BWOC of granite.

It should be mentioned that Figure 6 indicates that as the granite content increases, the permeability and porosity of cement samples gradually decrease. However, in Figure 5, the compressive strength of cement samples first decreases in sample 35% Gr and then increases significantly in sample 40% Gr. The same phenomenon was observed earlier by several authors after adding different concentrations of granite to the Portland cement used in concrete industry.32,47−49 The increase in the adhesion force between the cement and granite waste as the concentration of the granite waste was increased is another reason for the increase in the strength for the sample 40% Gr, this behavior was also reported earlier by Singh et al.50 The reason for the poor strength performance of the 35% granite is attributed to its poor microstructure. As explained by Singh et al.,50 addition of this amount of the granite waste increased the area of total particles, which requires additional amount of cement to bind the granite waste particles. As the cement quantity was the same for all the samples, there was a reduction in the strength trend at 35% granite.

3.4. Selecting the Best Slurry

A comparison between the three concentrations of granite waste materials considered in this study is performed to select the best granite concentration. The properties for each cement sample were tabulated, as shown in Table 3. For instance, sample 40% Gr exhibited the best performance for all properties evaluated in this study, as shown in Table 3. Sample 35% Gr exhibited the worst elastic and failure parameters while sample 30% Gr showed the worst petrophysical properties. The results shown in Table 3 confirm that sample 40% Gr in which the silica flour is replaced by with 40% BWOC of granite is the best granite-based slurry.

Table 3. Comparison of the Properties of the Granite-Based Cement Samples.

| sample name | sample ID | Poisson’s ratio | elastic modulus (GPa) | UCS (MPa) | tensile strength (MPa) | permeability (mD) | porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30% BWOC of granite | 30% Gr | 0.256 | 25.3 | 57.1 | 2.07 | 0.055 | 21.4 |

| 35% BWOC of granite | 35% Gr | 0.248 | 26.0 | 53.3 | 1.68 | 0.047 | 20.1 |

| 40% BWOC of granite | 40% Gr | 0.266 | 23.8 | 61.6 | 3.26 | 0.041 | 19.4 |

After selecting the best granite concentration, the optimum silica concentration was compared with the best granite concentration. In which the replacement of the 35% BWOC, which is the optimum silica flour concentration as indicated by previous studies,51,52 with 40% of granite waste material improved the properties of the cement, as explained in the previous sections.

The obtained results confirm that using 40% BWOC of granite waste instead of 35% BWOC of silica flour could slightly improve the cement stability under shear deformation, as shown by a reduction of Young’s modulus by 2.5% (Figure 4b) and a minor increase of Poisson’s ratio by 0.4% (Figure 4a).

Moreover, the addition of 40% BWOC of the granite waste showed an enhancement in the failure parameters compared to the sample with 35% BWOC of silica flour in which the compressive and tensile strengths were improved by 5.7 and 39.3%, respectively (Figure 5). Where this improvement in the failure parameters is because the pore filling impact of very fine used granite material that is smaller than cement and silica flour, which is able to fill capillary pores and other voids, leading to a denser and stronger material. In addition, the granite waste has higher aluminum concentration around 11.4% compared to silica flour which has only 0.47%, as shown in Table 1, which assures some pozzolanic reaction with the high calcium that presents in the cement pores (72%). During the hydration process, the interaction between silica, alumina, and calcium ions produces various types of hydrates such as calcium silicate hydrates (CSH), calcium aluminate hydrates, and calcium aluminum silicate hydrates.53 The reaction between cement and granite waste results in producing calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) crystals that contribute to the high compressive strength.54 Where the aluminum readily enters the CSH of the cement, and this substitution has an important effect in several aspects of the chemical behavior of the cement.55−60 The improvement in the compressive and tensile strengths can increase the ability of cement in supporting the casing, improving cement resistance to react with formation fluid, and enduring the tension forces to carry the casing weight.

Furthermore, 40% Gr sample showed a reduction in the petrophysical properties compared with sample 35% SF in which the permeability and porosity of 40% Gr were 64.7 and 28.9% less than 35% SF, respectively, (Figure 6). Where this reduction is attributed to the pore filling impact of the granite waste material, which as explained earlier has particles of less size compared with both silica flour and Saudi Class G cement, as indicated in Figure 2. This reduction in the petrophysical properties can significantly improve the cement matrix zonal isolation.

4. Conclusions

The possibility of reducing the oil-well cementing cost by replacing the silica flour with the inexpensive granite waste material for applications of cementing the oil-wells high-temperature conditions was evaluated. Three concentrations of the granite waste material (30, 35, and 40% BWOC) were evaluated to be used as alternative for 35% silica flour. Based on the evaluated properties and the obtained results, the following points are concluded:

Granite waste (40%) could be used as alterative for silica flour in oil well-cement.

Addition of the 40% BWOC of granite waste material showed a slight improvement in the cement Poisson’s ratio and Young’s modulus.

Compared to the sample with 35% of silica flour, the compressive strength was enhanced by 5.7% and its tensile strength improved by 39.3% when 40% BWOC of granite waste is added.

Addition of 40% BWOC of the granite waste decreased both permeability and porosity of the cement by 64.7 and 17.9%, respectively, compared with the sample incorporating 35% BWOC of the silica flour.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the College of Petroleum Engineering & Geosciences at the King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals for providing the support to conduct this research. The authors would like to thank Mr. Khaled Elnahas for providing the granite waste.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- El-Gamal S. M. A.; Hashem F. S.; Amin M. S. Influence of carbon nanotubes, nanosilica and nanometakaolin on some morphological-mechanical properties of oil well cement pastes subjected to elevated water curing temperature and regular room air curing temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 146, 531–546. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed R. M.; Takach N. E.; Khan U. M.; Taoutaou S.; James S.; Saasen A.; Godøy R. Rheology of foamed cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 353–361. 10.1016/j.cemconres.2008.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues E. C.; de Andrade Silva F.; de Miranda C. R.; de Sá Cavalcante G. M.; de Souza Mendes P. R. An appraisal of procedures to determine the flow curve of cement slurries. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 159, 617–623. 10.1016/j.petrol.2017.09.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S.; Ahmed A.; Gajbhiye R. Influence of Nanoclay Content on Cement Matrix for Oil Wells Subjected to Cyclic Steam Injection. Materials 2019, 12, 1452. 10.3390/ma12091452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E.; Well B.. Cementing; Elsevier: New York, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S.. Effect of the Temperature on the Strength of Nanoclay-Based Cement under Geologic Carbon Sequestration. In the Proceedings of the 2019 AADE National Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, Colorado, USA, 9–10 American Association of Drilling Engineers; April 2019.

- Taylor H. F. W.Cement chemistry; 2nd ed; Thomas Telford Publishing: London. 1997. ISBN: 07277 25920, 10.1680/cc.25929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luke K. Phase studies of pozzolanic stabilized calcium silicate hydrates at 180 C. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1725–1732. 10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E. B.; Guillot D.. Well Cementing; 2nd ed. Sugar Land, Texas, Schlumberger: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Calvert D. G.; Smith D. K. API Oilwell Cementing Practices. J. Pet. Technol. 1990, 42, 1364–1373. 10.2118/20816-PA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S. Improved durability of Saudi Class G oil-well cement sheath in CO2 rich environments using olive waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120623. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elkatatny S.; Gajbhiye R.; Ahmed A.; Mahmoud A. A. Enhancing the cement quality using polypropylene fiber. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2019, 10, 1097–1107. 10.1007/s13202-019-00804-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S.. Synthetic Polypropylene Fiber Content Influence on Cement Strength at High-Temperature Conditions. In the Proceedings of the 53rd US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium held in New York, USA; British Geotechnical Association at The Institution of Civil Engineers: 23–26 June 2019.

- Ahmed A.; Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S.; Gajbhiye R. Improving Saudi Class G Oil-Well Cement Properties Using the Tire Waste Material. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 27685–27691. 10.1021/acsomega.0c04270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S.; Ahmed S. A.; Mahmoud M.. Nanoclay Content Influence on Cement Strength for Oil Wells Subjected to Cyclic Steam Injection and High-Temperature Conditions. In the Proceedings of the 2018 Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, UAE; Society of Petroleum Engineers: 12–15 November, 2018, DOI: 10.2118/193059-MS. [DOI]

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S.; Mahmoud M.. Improving Class G Cement Carbonation Resistance Using Nanoclay Particles for Geologic Carbon Sequestration Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, UAE; Society of Petroleum Engineers: 12–15 November 2018, DOI: 10.2118/192901-MS. [DOI]

- Soares L. W. O.; Braga R. M.; Freitas J. C. O.; Ventura R. A.; Pereira D. S. S.; Melo D. M. A. The effect of rice husk ash as pozzolan in addition to cement Portland class G for oil well cementing. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 131, 80–85. 10.1016/j.petrol.2015.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choolaei M.; Rashidi A. M.; Ardjmand M.; Yadegari A.; Soltanian H. The effect of nanosilica on the physical properties of oil well cement. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2012, 538, 288–294. 10.1016/j.msea.2012.01.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elkatatny S. Development of a Homogenous Cement Slurry Using Synthetic Modified Phyllosilicate while Cementing HPHT Wells. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1923. 10.3390/su11071923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Y.; Du J.; Guo S.; Liu H.; Huang C. Properties of oil well cement with high dosage of metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 39–48. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anjos M. A. S.; Martinelli A. E.; Melo D. M. A.; Renovato T.; Souza P. D. P.; Freitas J. C. Hydration of oil well cement containing sugarcane biomass waste as a function of curing temperature and pressure. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 109, 291–297. 10.1016/j.petrol.2013.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Wu Q.; Zhang J.; Qing Y.; Wu Y.; Lee S. Rheology, curing temperature and mechanical performance of oil well cement: Combined effect of cellulose nanofibers and graphene nano-platelets. Mater. Des. 2017, 114, 92–101. 10.1016/j.matdes.2016.10.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M. M.; Ahmad F.; Azmi M.; Mohd Zahid M. Z. A.; Ab Manaf M. B. H.; Isa N. F.; Zainol N. Z.; Azizi Azizan M.; Muhammad K.; Sofri L. A. Properties of Cement-Based Material Consisting Shredded Rubber as Drainage Material. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 815, 84–88. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.815.84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B. S.; Gupta R. C. A comprehensive review on the applications of waste tire rubber in cement concrete. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1323–1333. 10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Nagar R.; Agrawal V. Performance of granite cutting waste concrete under adverse exposure conditions. J. Cleaner Prod. 2016, 127, 172–182. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski K.; Stefaniuk D.; Sadowski Ł.; Krzywiński K.; Gicala M.; Różańska M. Potential use of granite waste sourced from rock processing for the application as coarse aggregate in high-performance self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 238, 117794. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannam S.; Najm H.; Vasconez R. Experimental study of concrete made with granite and iron powders as partial replacement of sand. Sustainable Mater. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–9. 10.1016/j.susmat.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lokeshwari M.; Jagadish K. S. Eco-friendly Use of Granite Fines Waste in Building Blocks. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 618–623. 10.1016/j.proenv.2016.07.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad A.; Shahid I.; Anwar U. H. C.; Baig M. N.; Khan S.; Shakir K. The Wastes Utility in Concrete. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2014, 8, 1323–1328. 10.22059/IJER.2014.825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; ISSN: 1735-6865

- Kumar Y.; Vardhan V. Use of Granite Waste as Partial Substitute to Cement in Concrete. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2015, 5, 25–31. Retrieved from https://www.ingentaconnect.com/search/article?option1=tka&value1=Use of Granite Waste as Partial Substitute to Cement in Concrete&pageSize=10&index=1.. [Google Scholar]

- Mashaly A. O.; Shalaby B. N.; Rashwan M. A. Performance of mortar and concrete incorporating granite sludge as cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 169, 800–818. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd Elmoaty A. E. M. Mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of concrete modified with granite dust. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 743–752. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.05.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N. K.; Kumar P.; Kumar S.; Thomas B. S.; Gupta R. C. Properties of concrete containing polished granite waste as partial substitution of coarse aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 158–163. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.06.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayalakshmi M.; Sekar A. S. S.; Ganesh prabhu G. Strength and durability properties of concrete made with granite industry waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 46, 1–7. 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moura J. C.; Santos T. J.; Silva J. S.; Santos K. R.; Gonçalves J. P.; Simonelli G. Influence of Granite Waste on The Rheological Behavior of Oil Well Cement Slurries. Braz. J. Pet. Gas 2019, 13, 47–56. 10.5419/bjpg2019-0005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima S.; Hou P.; Corr D. J.; Shah S. P. Modification of cement-based materials with nanoparticles. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 36, 8–15. 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2012.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowiak K. J.; Thomas J. J.; Musso S.; James S.; Akono A. T.; Ulm F. J. Nano-chemo-mechanical signature of conventional oil-well cement systems: Effects of elevated temperature and curing time. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 67, 103–121. 10.1016/j.cemconres.2014.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S. Improving Class G Cement Carbonation Resistance for Applications of Geologic Carbon Sequestration Using Synthetic Polypropylene Fiber. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 76, 103184. 10.1016/j.jngse.2020.103184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worldwide Cementing Practices, API, Dallas, Texas, USA, 1991.

- API Recommended Practice 10B-2-Recommended Practice for Testing Well Cements, second edition American Petroleum Institute, Washington, 2013.

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S.. The Effect of Silica Content on the Changes in the Mechanical Properties of Class G Cement at High Temperature from Slurry to Set. In the Proceedings of the 53rd US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium held in New York, USA; Society of Petroleum Engineers: 23–26 June 2019.

- ASTM C109/C109M. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-In. or [50-Mm] Cube Specimens); ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Sanjuán M. A.; Muñoz-Martialay R. Influence of the age on air permeability of concrete. J. Mater. Sci. 1995, 30, 5657–5662. 10.1007/BF00356701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters E. J.Porosity and Fluid Saturation. In Advanced Petrophysics; Live Oak Book Company: Austin, TX, USA; Volume 1, pp. 2–7. 2012. ISBN 978–1–936909-45-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A.; Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S.; Chen W. The Effect of Weighting Materials on Oil-Well Cement Properties While Drilling Deep Wells. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6776. 10.3390/su11236776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fjaer E.; Holt R. M.; Horsrud P.; Reean A. M.; Risnes R.. Petroleum Related Rock Mechanics; 2nd edition. Elsevier Science; 2007. ISBN-10: 0444502602. [Google Scholar]

- Joel M.Use of Crushed Granite Fine as Replacement To River Sand in Concrete Production. Leo. Elec. J. Prac. Tech. 2010, 9 (). [Google Scholar]

- Ashola M. Cost Effectiveness of Replacing Sand with Crushed Granite Fine (CGF) In the Mixed Design of Concrete. IOSR J. Mech. Civil Eng. 2013, 10, 01–06. 10.9790/1684-1010106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felixkala T.; Partheeban P. Granite powder concrete. Ind. J. Sci. Techno. 2010, 3, 311–317. 10.17485/ijst/2010/v3i3.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; ISSN: 0974–6846,

- Singh S.; Nagar R.; Agrawal V.; Rana A.; Tiwari A. Sustainable Utilization of Granite Cutting Waste In High Strength Concrete. J. Cleaner Prod. 2016, 116, 223–235. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.12.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de sena Costa B. L.; de Souza G. G.; de Oliveira Freitas J. C.; da Silva Araujo R. G.; Santos P. H. S. Silica content influence on cement compressive strength in wells subjected to steam injection. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 158, 626–633. 10.1016/j.petrol.2017.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud A. A.; Elkatatny S. Mitigating CO2 Reaction with Hydrated Oil Well Cement under Geologic Carbon Sequestration Using Nanoclay Particles. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 68, 102902. 10.1016/j.jngse.2019.102902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doneliene J.; Eisinas A.; Baltakys K.; Bankauskaite A. The Effect of Synthetic Hydrated Calcium Aluminate Additive on the Hydration Properties of OPC. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 1. 10.1155/2016/3605845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amin S. K.; Allam M. E.; Garas G. L.; Ezz H. A Study of the Chemical Effect of Marble and Granite Slurry on Green Mortar Compressive Strength. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2020, 44, 19. 10.1186/s42269-020-0274-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson I. G. The nature of C–S–H in hardened cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 1131–1147. 10.1016/S0008-8846(99)00168-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson I. G.; Cabrera J. G. Nature of C–S–H in model slag-cements. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 259–266. 10.1016/S0958-9465(00)00022-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brough A. R.; Katz A.; Sun G.-K.; Struble L. J.; Kirkpatrick R. J.; Young J. F. Adiabatically cured, alkali-activated cementbased wasteforms containing high levels of fly ash, formation of zeolites and Al-substituted C–S–H. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1437–1447. 10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00589-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J.; Cincotto M. A.; Panepucci H. 29Si and 27Al high-resolution NMR characterization of calcium silicate hydrate phases in activated blast-furnace slag pastes. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 993–1001. 10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00530-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava O. P.; Shrivastava R. Sr2+ uptake and leachability study on cured aluminum-substituted tobermorite-OPC admixtures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1251–1255. 10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00567-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; 2001

- Hong S.-Y.; Glasser F. P. Alkali sorption by C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels: part II. Role of alumina. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 1101–1111. 10.1016/S0008-8846(02)00753-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]