Correction to: J Transl Med (2020) 18:7. 10.1186/s12967-019-02196-9

Following publication of the original article [1], the authors noted that one study (PACE trial) [2] had been missed in the captured data. Accordingly, some corrections were made in multiple sections, including the addition of the reference information for the PACE trial in the reference list. The updated sections are given in this Correction, and the changes have been highlighted in bold typeface. The original article [1] has been corrected.

Abstract

The updated sentences are given below, and the changes have been highlighted in bold typeface.

Result: Among 513 potentially relevant articles, 56 RCTs met our inclusion criteria; these included 25 RCTs of 22 different pharmacological interventions, 29 RCTs of 19 non-pharmacological interventions and 2 RCTs of combined interventions. These studies accounted for a total of 6956 participants (1713 males and 5243 females, 6499 adults and 457 adolescents). CDC 1994 (Fukuda) criteria were mostly used for case definitions (42 RCTs, 75.0%), and the primary measurement tools included the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS, 35.7%) and the 36-item Short Form health survey (SF-36, 32.1%). Eight interventions showed statistical significance: 3 pharmacological (Staphypan Berna, Poly(I):poly(C12U) and CoQ10 + NADH) and 5 non-pharmacological therapies (cognitive-behavior-therapy-related treatments, graded-exercise-related therapies, rehabilitation, acupuncture and abdominal tuina). However, there was no definitely effective intervention with coherence and reproducibility.

Result section

The updated sentences are given below, and the changes have been highlighted in bold typeface.

Characteristics of RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria

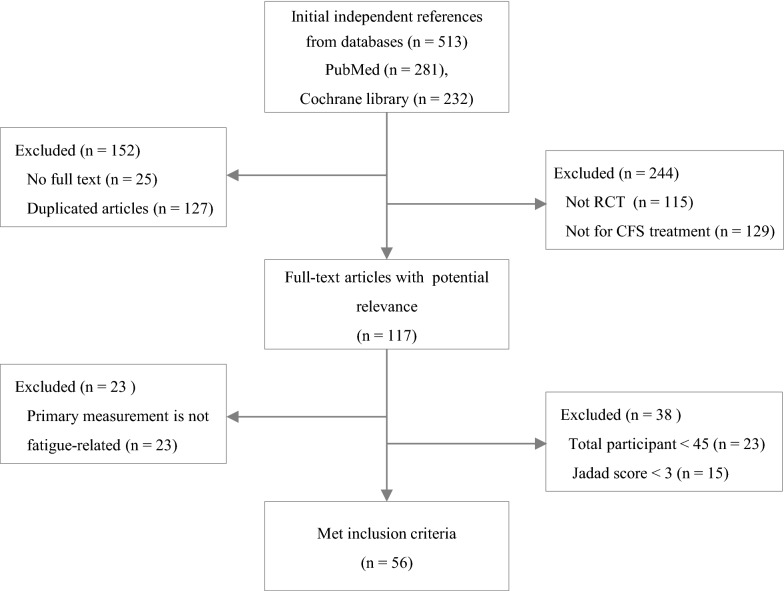

From the PubMed and Cochran databases, a total of 513 articles were initially identified, and 56 articles ultimately met the inclusion criteria for this study (Fig. 1). Fifty-one RCTs (91.1%) were conducted for adult patients, while 5 RCTs (8.9%) were conducted for the adolescent population (Table 1). The majority of RCTs were conducted in 3 countries: the UK (n = 16), the Netherlands (n = 14), and the USA (n = 9). Regarding interventions, 29 RCTs (51.8%) conducted nonpharmacological interventions, 25 RCTs (44.6%) conducted pharmacological interventions and 2 RCTs conducted a combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions (Tables 2 and 3).

Characteristics of participants and case definitions for inclusion criteria

In 56 RCTs, a total of 6956 participants (1713 males and 5243 females, 6499 adults with a mean age of 40.2 ± 4.0 years and 457 adolescents with a mean age of 15.5 ± 0.3 years) were enrolled. Fifty-five RCTs (98.2%) adapted at least one of the following CFS case definitions: CDC 1994 (Fukuda) criteria (42 RCTs), Oxford 1991 (Sharpe) criteria (13 RCTs), CDC 1988 (Holmes) criteria (3 RCTs), Lloyd 1988 criteria (2 RCTs), and Schluederberg 1992 (2 RCTs).

Main outcome measurement

A total of 31 primary measurement tools were used to assess the main outcome in 56 RCTs. The Checklist Individual Strength (CIS) was the most frequently used (35.7%), and others included the 36-item Short Form health survey (SF-36, 32.1%), Sickness Impact Profile (SIP, 14.3%), Chalder Fatigue Scale (14.3%), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, 10.7%) and Clinical Global Impression (CGI, 8.9%). There were 29 RCTs that used multiple primary measurements (Table 1).

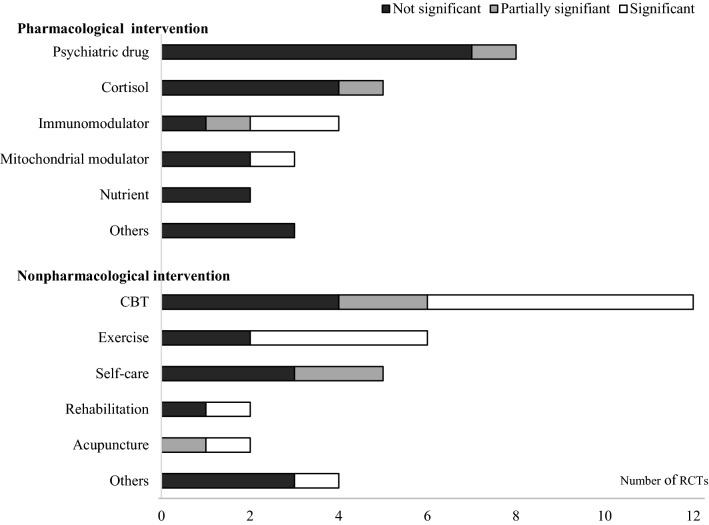

RCTs with nonpharmacological interventions

There were 29 RCTs in the nonpharmacological category (26 for adults, 3 for adolescents) with 19 kinds of interventions, mainly CBT (n = 12), exercise (n = 6), and self-care (n = 5). The mean treatment period was 18.5 ± 8.9 weeks (17.1 ± 7.1 weeks for adults, 30.7 ± 15.1 weeks for adolescents). Of the 12 CBT subcategories, 6 RCTs showed statistical effectiveness of CBT compared to the control [41, 44, 46, 49, 50, 52]. In addition, 4 RCTs of graded-exercise-related therapies [46, 53, 55, 56] and 3 RCTs of integrative, consumer-driven rehabilitation [64], acupuncture [65] and abdominal tuina [67] showed a significantly effect of the intervention compared to the control (Table 3).

Discussion section

The updated sentences are given below, and the changes have been highlighted in bold typeface. Sentences with only a change in reference citations numbering (the original references 46–92 were re-numbered to 47–93) are not provided.

The first paragraph (the 3rd sentence)

To support future studies for CFS/ME treatments, we systematically reviewed 56 RCTs to investigate characteristics such as participants, case definitions, interventions and primary measurements.

The second paragraph (the 1st sentence)

The sex ratio of the participants was male 1 vs. female 3 (1713/5143, except one RCT had recruited only females).

The third paragraph (the 1st–4th sentences)

A total of 56 RCTs included 25 pharmacological, 29 nonpharmacological and 2 combined interventions (Table 1). The mean treatment period of the RCTs with nonpharmacological interventions was longer than that with medication, especially for adolescents (total: 18.5 ± 8.9 vs. 10.8 ± 6.8, adolescent: 30.7 ± 15.1 vs. 8.5 ± 0.7, Table 1). Periodically, the trials gradually increased, with 13 trials in the 1990s, 19 trials in the 2000s and 24 trials in the 2010s. The pharmacological RCTs were predominant in the 1990s and 2000s, while nonpharmacological interventions became predominant in the 2010s (pharmacological:nonpharmacological ratio from 20:14 to 7:17) (data not shown).

The fifth paragraph (the 8th and 11th sentences)

Contrary to the positive outcomes in the 1990s and 2000s, more recent CBT trials have failed to show consistent benefits in patients with CFS/ME: 5 of 8 RCTs of CBT did not show significant effects in our data.

In our data, 5 of 6 RCTs with graded-exercise-related therapies presented positive outcomes; however, the clinical usefulness of GET is highly controversial [89].

The eighth paragraph (the 5th sentence)

In addition, only 9 of 56 RCTs had presented fragmentary data related to blood parameters.

Reference section

As one RCT (PACE trial) was added, its reference information [2] was included in the reference list as reference number 46. Accordingly, the original references 46–92 were re-numbered to 47–93.

Figures

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study. The numbers of literatures were changed and highlighted in bold typeface. ‘Excluded (n= 244)’ on upper-right box, ‘Not RCT (n = 115)’, ‘Not for CFS treatment (n = 129)’, ‘Full-text articles with potential relevance (n = 117)’ and ‘Met inclusion criteria (n= 56)’

Fig. 2.

Graphical display for statistical significance of interventions. Number of RCTs in nonpharmacological intervention were added one each in CBT (significant), Exercise (significant) and others (not significant)

Tables

The updated Tables 1, 3 and 4 are given below, and the changes have been highlighted in bold typeface.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Items | Adults | Adolescents | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. of RCT (%) | 51 (91.1) | 5 (8.9) | 56 (100.0) |

| N. of participants (%) (males/females) | 6499 (93.4) (1611/4888) | 457 (6.6) (102/355) | 6956 (100.0) (1713/5243) |

| Mean N. of participants | 127.4 ± 113.3 | 91.4 ± 33.5 | 124.2 ± 109.0 |

| Mean age (year)a | 40.2 ± 4.0 | 15.5 ± 0.3 | 38.7 ± 8.1 |

| N. of case definitions for inclusion criteria (%)b,c | |||

| CDC 1994 (Fukuda) | 37 (72.5) | 5 (100.0) | 42 (75.0) |

| Schluederberg 1992 | 2 (3.9) 12 (23.5) | – | 2 (3.6) 13 (23.2) |

| Oxford 1991 (Sharpe) | 3 (5.9) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (5.4) |

| CDC 1988 (Holmes) | 2 (3.9) | – | 2 (3.6) |

| Lloyd 1988 | 5 (9.8) | – | 6 (10.7) |

| Others | 1 (20.0) | ||

| RCTs with pharmacological intervention (N, %) | 23 (92.0) | 2 (8.0) | 25 (100.0) |

| Kinds of interventions (%) | 20 (90.9) | 2 (9.1) | 22 (100.0) |

| Mean treatment period (weeks) | 11.0 ± 7.0 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 10.8 ± 6.8 |

| RCTs with nonpharmacological intervention (N, %) | 26 (89.7) | 3 (10.3) | 29 (100.0) |

| Kinds of interventionsd | 18 (94.7) | 2 (10.5) | 19 (100.0) |

| Mean treatment period (weeks) | 17.1 ± 7.1 | 30.7 ± 15.1 | 18.5 ± 8.9 |

| RCTs with combined interventions (N, %) | 2 (100.0) | – | 2 (100.0) |

| Kinds of interventions (%) | 4 (100.0) | – | 4 (100.0) |

| Mean treatment period (weeks) | 26 ± 2.8 | – | 26 ± 2.8 |

| Primary measurements in 55 RCTs (n, %)c,e | |||

| Checklist Individual Strength (CIS) | 20 (35.7) | ||

| 36-item Short Form health survey (SF-36) | 18 (32.1) | ||

| Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) | 8 (14.3) | ||

| Chalder Fatigue Scale | 8 (14.3) | ||

| Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | 6 (10.7) | ||

| Clinical Global Impression (CGI) | 5 (8.9) | ||

| Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) | 3 (5.4) | ||

| School attendance rate (SAR) | 3 (5.4) | ||

| Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Others | 21 (37.5) | ||

aThis is the mean of ages presented as median or mean in original articles

bTwelve RCTs used two case definitions for inclusion criteria

cSome items have been applied multiple times, thus the total percentage is larger than 100%

dOne intervention (CBT) was used for both of adult and adolescent studies

eTwenty-nine RCTs used multiple primary measurements

Table 3.

RCTs with nonpharmacological interventions

| Intervention | N. of participants (N. of arms, control) | Period (week) | Primary measurement (subscale) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | ||||

| iCBT [41] | 240 (3, waitlist) | 27 | CIS (fatigue) | P < 0.01 |

| Group CBT [42] | 204 (3, waitlist) | 24 | CIS (fatigue), SF-36 (physical score) | CIS: d > 0.8 |

| CBT [43] | 122 (2, MRT) | 24 | CIS (fatigue), SF-36 | Not significant |

| FITNET [44] | 135 (2, usual care) | 48 | SAR, CIS (fatigue), CHQ (physical score) | P < 0.01 |

| CBT + GET [46] | 120 (2, usual care) | 24 | SF-36 | Not significant |

| CBT [46] | 640 (4, MC) | 24 | Chalder scale, SF-36 (physical score) | P < 0.01 |

| Family-focused CBT [47] | 63 (2, psychoeducation) | 24 | SAR | Not significant |

| Group CBT [48] | 153 (3, education + support, MC) | 16 | SF-36 (physical, mental score) | Not significant |

| CBT [49] | 71 (2, waitlist) | 20 | CIS (fatigue), SF-36 (physical score), SAR | CIS, SF-36: P < 0.01, SAR: P < 0.05 |

| CBT [50] | 278 (3, guided support, no treatment) | 32 | CIS (fatigue), SIP-8 | CIS: P < 0.01, SIP: P < 0.05 |

| CBT [51] | 60 (2, relaxation) | 16–24 | Chalder scale, SF-36 (physical score) | Chalder scale: P < 0.01 |

| CBT [52] | 60 (2, MC) | 16 | Karnofsky normal function scale | P < 0.01 |

| Exercise | ||||

| Guided exercise self-help [53] | 211 (2, MC) | 12 | Chalder scale, SF-36 (physical score) | P < 0.01 |

| Qigong [54] | 64 (2, waitlist) | 16 | Chalder scale, SF-12 | Not significant |

| GET [46] | 640 (4, MC) | 24 | Chalder scale, SF-36 (physical score) | P < 0.01 |

| GET [55] | 49 (2, MC) | 12 | Self-rated global change score | P < 0.05 |

| Education to encourage graded exercise [56] | 148 (4, MC) | 16 | SF-36 (physical score) | P < 0.01 |

| Graded aerobic exercise [57] | 66 (crossover, flexibility therapy) | 12 | CGI | Not significant |

| Self-care | ||||

| Fatigue self-management [58] | 137 (3, usual care) | 12 | FSS | Not significant |

| Group-based self-management [59] | 137 (2, usual care) | 16 | SF-36 (physical score) | Not significant |

| Guided self-instruction [60] | 123 (2, waitlist) | 20 | CIS (fatigue), SF-36 (physical, social score) | CIS: P < 0.01 |

| Stepped care [61] | 171 (2, CBT) | 16 | CIS (fatigue), SIP-8, SF-36 (physical score) | Not significant |

| Guided self-instruction [62] | 169 (2, waitlist) | 16 | CIS (fatigue), SIP-8, SF-36 (physical score) | CIS, SIP8: P < 0.01 |

| Rehabilitation | ||||

| Pragmatic rehabilitation [63] | 302 (3, supportive listening, general treatment) | 18 | Chalder scale, SF-36 (physical score) | Not significant |

| Integrative, consumer-driven rehabilitation [64] | 47 (2, delayed program) | 16 | CFS Symptom Rating Form, The QoL Index | P < 0.05 |

| Acupuncture | ||||

| Acupuncture [65] | 150 (3, sa-am, no treat) | FSS | P < 0.05 | |

| Acupuncture [66] | 100 (2, sham) | Chalder scale, SF-12, GHQ-12 (mental score) | Chalder scale: P < 0.05 | |

| Others | ||||

| Abdominal tuina [67] | 77 (2, acupuncture) | Chalder scale, SAS, HAMD | P < 0.05 | |

| Adaptive pacing [46] | 640 (4, MC) | 24 | Chalder scale, SF-36 (physical score) | Not significant |

| Low-sugar, low-yeast diet [68] | 52 (2, healthy eating) | 24 | Chalder scale, SF-36 | Not significant |

| Distant healing [69] | 409 (4, not knowing, no treat) | 24 | SF-36 (mental score) | Not significant |

CBT cognitive behavior therapy, FITNET: Fatigue In Teenagers on the interNET, GET graded exercise therapy, CIS Checklist Individual Strength, SF-36 36-item Short Form health survey, SAR school attendance rate, CHQ Child Health Questionnaire, SIP-8 Sickness Impact Profile, CGI Clinical Global Impression, FSS Fatigue Severity Scale, GHQ-12 General Health Questionnaire-12, SAS Self-rating Anxiety Scale, HAMD Hamilton rating scale for Depression

Table 4.

RCTs with pharmacological and nonpharmacological combined interventions

| Intervention | Intervention | Intervention | Intervention | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoxetine + graded exercise [70] |

Exercise + fluoxetine: 33 Exercise + placebo: 34 Appointment + fluoxetine: 35 Appointment + placebo: 34 |

24 20 mg/day |

Chalder scale |

Graded exercise P < 0.05 |

| Dialyzable leukocyte extract (DLE) + CBT [71] |

DLE + CBT: 20 DLE + clinic: 26 Placebo + CBT: 21 Placebo + clinic: 23 |

28 5 × 108 leukocytes 8 times biweekly |

VAS (global well-being) | Not significant |

VAS Visual Analogue Scale

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kim Do-Young, Lee Jin-Seok, Park Samuel-Young, Kim Soo-Jin, Son Chang-Gue. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) J Transl Med. 2020;18:7. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-02196-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, Potts L, Walwyn R, DeCesare JC, Baber HL, Burgess M, Clark LV, Cox DL, Bavinton J, Angus BJ, Murphy G, Murphy M, O’Dowd H, Wilks D, McCrone P, Chalder T, Sharpe M. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9768):823–836. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]