Abstract

Tigecycline is the antibiotic of last resort for the treatment of extensively drug-resistant bacterial infections, mainly those of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. The plasmid-mediated tet(X3) gene has recently been described in various pathogens that are resistant to tigecycline. We report three tigecycline-resistant Acinetobacter towneri strains isolated from porcine faeces in China, which all contained the tet(X3)-harboring plasmids. A broth microdilution method was used to examine the antimicrobial susceptibility of the isolates, and S1-Nuclease digestion pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (S1-PFGE) was used to characterize their plasmid profiles. The whole-genome sequences of the isolates were determined with the Nanopore PromethION platform. The sequence analysis indicated that the strains were A. towneri. They showed resistance to multiple antibiotics, and all the resistance genes were located on plasmids. The three tet(X3)-harboring plasmids had a similar backbone structure, and all contained bla OXA-58 with various insertion elements (IS). ISCR2 is considered an important factor in tet(X3) mobilization. In addition to ISCR2, we demonstrate that IS26 generates a circular intermediate containing the tet(X3) gene, which could increase the dissemination risk. To our knowledge, this is the first report of tet(X3)- and bla OXA-58-harboring plasmids in A. towneri. Because the IS26 is frequently found in front of tet(X3), research should be directed toward the action of IS26 in the spread of tet(X3).

Keywords: Acinetobacter towneri, tet(X3), IS26, circular intermediate, blaOXA-58

Introduction

Tigecycline, a broad-spectrum modified minocycline derivative, is considered a drug of last resort against multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, especially carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) (Tasina et al., 2011). However, recent studies have reported that plasmid-mediated tigecycline- resistance genes have been detected in various bacterial species. In particular, the novel tigecycline- resistance genes tet(X3), tet(X4), tet(X5), and tet(X6) have recently been discovered in Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter from sewage, livestock and humans (He et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; He et al., 2020).

The tet(X3) gene has been identified in Acinetobacter baumannii, A. schindleri, A. indicus, and Empedobacter brevis, but limited information about the mechanisms of tet(X3) transmission in bacteria is available (Li et al., 2019; He et al., 2020a). It has been shown that tet(X3) is transferred by plasmids or transposons in a mechanism called ‘rolling-circle (RC) transposition’ via ISCR2 (He et al., 2019). Moreover, plasmids carrying both tet(X3) and bla NDM-1 were detected in A. indicus in a recent study, but with no information on the plasmid containing tet(X3) together with other carbapenemase genes in A. towneri (He et al., 2020a).

In this study, we isolated plasmids carrying both tet(X3) and bla OXA-58 from A. towneri strains isolated from porcine faeces in China. We describe the whole-genome sequences of the three A. towneri isolates harboring tet(X3) and show that IS26 plays an important role in the spread of tet(X3).

Materials and Methods

Clinical Isolates and Detection of the tet(X) Genes

One hundred and sixteen anal swabs from pigs were collected on a pig farm in Guangxi Province, southern China, in 2019. The samples were stored at low temperature and transported directly to the laboratory. Three Acinetobacter strains were isolated from three independent anal swabs and cultured on Leeds Acinetobacter Agar containing 4 mg/L tigecycline. These strains were designated GX3, GX5, and GX7. We screened for the tigecycline-resistant genes tet(X3), tet(X4), and tet(X5) with PCR, as described in a previous report (Ji et al., 2020).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

The broth microdilution method was used to examine the antimicrobial susceptibility (ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, spectinomycin, tetracycline, florfenicol, sulfisoxazole, sulfamethoxazole, ceftiofur, ceftazidime, colistin, gentamicin, meropenem, and imipenem) of the isolates according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (CLSI, 2019), and E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as the quality control. The breakpoint criteria for tigecycline in Acinetobacter spp. was evaluated according to the EUCAST epidemiological cut-off values (https://www.mic.eucast.org/Eucast2/).

S1-Nuclease Digestion Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (S1-PFGE)

S1-PFGE was performed to characterize the plasmid profiles in the three strains. Salmonella H9812 was used as the size standard. Briefly, the cultured cells (optical density at 600 nm of 1.0) were harvested and suspended in Tris–EDTA buffer (pH 8.0), and then mixed with 2% gold agarose (SeaKem® Gold Agarose, Lonza, Atlanta, GA, USA) to make plugs. The plugs were treated with S1 nuclease (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) at 37°C for 15 min, and the DNA fragments were separated with the CHEF Mapper XA system (Bio-rad, USA), as previously described (Barton et al., 1995).

Conjugation and Electrotransformation Analysis

The plasmids were extracted and used to electrotransform into the recipient strains (laboratory strains Escherichia coli DH5α, E. coli C600, and bla OXA-23-positive A. baumannii isolate 5AB) (He et al., 2019). The plasmid-free strains E. coli C600 (streptomycin resistant) and E. coli 26R 793 (rifampin resistant) were chosen as recipient strains for conjugation (Wang et al., 2013).

Whole Genome Sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of the three A. towneri isolates was performed with the Nanopore PromethION platform (Biomarker Technologies, Beijing, China). The sequences were assembled with Canu v1.5. Pilon v1.22 was used to improve the draft genome assemblies by correcting bases.

Genome Analysis

The bioinformatics analysis of these sequences was conducted at the CGE server (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/), including multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) to identify the (STs), and ResFinder to detect drug-resistance genes. The WGS annotations were designed with the Rapid Annotations using Subsystem Technology (RAST) annotation pipeline (version 2.0) (http://rast.nmpdr.org/). A phylogenetic tree based on plasmid replication initiator protein genes was constructed with the MEGA version 7.0 software using the neighbour-joining method (Kumar et al., 2016). The sequence alignment was generated with Easyfig version 2.1 (Sullivan et al., 2011).

Results and Discussion

Strain Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

A 16S rDNA PCR detection and sequencing analysis suggested that these strains belonged to the genus Acinetobacter. The rpoB gene was then used to identify the Acinetobacter isolates at the species level. This analysis showed that strain GX3 was identical to GX5, and when compared with Acinetobacter spp. from the GenBank database, it shared a high degree of nucleotide similarity (99.85%) with strain 19110F47 isolated from the faeces of swine in China (CP046045.1). The rpoB gene of strain GX7 shared greatest homology with that of strain 205 (97.21% identical at the nucleotide level) isolated from swine faeces in China (CP048014.1).

S1-PFGE was used to identify the plasmids in the isolates, and indicated that the GX5 and GX7 isolates both contained one large plasmid of ~180-kb in size. Strain GX3 contained two plasmids, approximately 50-kb and 150-kb in size. Electroporation and conjugation experiments showed that the tet(X3)-harboring plasmids in the three isolates could not transfer to E. coli DH5α, E. coli C600, E. coli 26R 793, or A. baumannii 5AB. This could be related to the host specificity of the plasmids.

All of these strains were resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, spectinomycin, tetracycline, florfenicol, sulfisoxazole, sulfamethoxazole, ceftiofur, ceftazidime, imipenem, and tigecycline, but were susceptible to gentamicin, meropenem and colistin. The strains also showed different minimal inhibitory concentration to enrofloxacin and ofloxacin ( Table S1 ). The tet(X3) gene was identified in all three isolates.

WGS Analysis

Strain GX3 contained one 2.59-Mb chromosome and two plasmids (148-kb and 54-kb). Strain GX5 contained a 2.63-Mb chromosome and a single plasmid (178-kb). Strain GX7 contained a 2.84-Mb chromosome and one plasmid (178-kb) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Characterization of the A. towneri strains and their corresponding plasmids carrying the tet(X3) gene.

| Strains | Species | Chromosomes(-bp) | GC contents(%) | Plasmids(-bp) | ORFs | Multiple drug resistance genes | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GX3 | A. towneri | 2,597,534 | 41.48 | 148,166 | 166 | sul2, mph(E), msr(E), tet(X3), bla OXA-58, dfrA20, floR, aph(3′)-Ia | SAMN14490802 |

| 54,135 | 68 | mph(E), msr(E) | |||||

| GX5 | A. towneri | 2,630,890 | 41.53 | 178,808 | 202 | sul2, mph(E), msr(E), tet(X3), bla OXA-58, dfrA20, floR, aph(3′)-Ia | SAMN14490803 |

| GX7 | A. towneri | 2,841,560 | 41.22 | 178,739 | 199 | sul2, erm(B), mph(E), msr(E), tet(X3), bla OXA-58, floR, aph(3′)-Ia | SAMN14490804 |

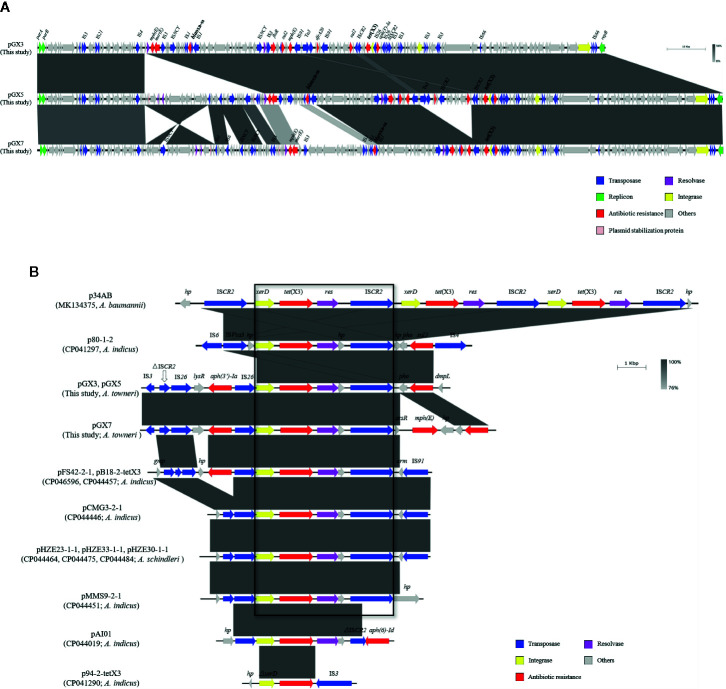

We analyzed the three tet(X3)-harboring plasmids from strains GX3, GX5, and GX7. All of them included several classes of resistance genes. As well as tet(X3) encoding tigecycline resistance, they contained bla OXA-58 encoding β-lactam resistance, sul2 encoding sulphonamide resistance, floR encoding chloramphenicol resistance, aph(3’)-Ia encoding aminoglycoside resistance, and mph(E) and msr(E) encoding macrolide resistance. However, dfrA20 encoding trimethoprim resistance was only identified in pGX3 and pGX5 ( Table 1 ). Notably, all of the resistance genes were located on plasmids in these strains ( Figure 1A ).

Figure 1.

(A) Sequence comparison of the tet(X3)-harboring plasmids. Comparison of plasmids pGX3, pGX5, and pGX7. Corresponding alignments are shown in gray. Arrows and triangles represent genes of different functional categories (dark blue: transposase; green: replicon protein; red: antibiotic resistance; pink: resolvase; golden: integrase; gray: other functions). (B) Comparison of plasmids in this study with 11 published plasmids. Large box contains the common sequences in 10 plasmids, including the xerD–tet(X3)–resolvase–ΔISCR2 genes. Corresponding alignments are shown in gray. Arrows and triangles represent genes of different functional categories.

A sequence analysis showed that the plasmids encoded the same replication protein. However, they did not belong to any known replicon type. A structural analysis of the three tet(X3)-harboring plasmids showed that they shared a high degree of nucleotide similarity (≥91%), suggesting that they may be derived from the same ancestral MDR plasmid backbone ( Figure 1A ).

Analysis of the Genetic Contexts of tet(X3)

A comparative analysis of the genetic contexts of tet(X3) was performed of the plasmids detected in this study and a series of tet(X3)-harboring plasmids from Acinetobacter spp. recorded in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. Eleven identified and annotated plasmids from the database were included ( Figure 1B ): p34AB (MK134375) from A. baumannii, pHZE23-1-1 (CP044464), pHZE30-1-1 (CP044484), pHZE33-1-1 (CP044475) from A. schindleri, p80-1-2 (CP041297), pFS42-2-1 (CP046596), pB18-2-tetX3 (CP044457), pCMG3-2-1 (CP044446), pMMS9-2-1 (CP044451), pAI01 (CP044019), and p94-2-tetX3 (CP041290) from A. indicus. To understand the evolutionary relationships among these tet(X3)-harboring plasmids, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the sequences of the repB genes in the plasmids ( Figure S1 ). During the comparative analysis, pGX3, pGX5, and pGX7 exhibited a high degree of nucleotide similarity (91%–92% nucleotide identity and 90.11%–90.37% coverage) with eight plasmids, including pFS42-2-1, pB18-2-tetX3, pCMG3-2-1, pMMS9-2-1 and pAI01 from A. indicus, pHZE23-1-1, pHZE30-1-1 and pHZE33-1-1 from A. schindleri. The length of the eight plasmids ranged from 110-kb to 179-kb. Interestingly, no repB-nucleotide similarity exhibited between the plasmids in our study and the p34AB (278-kb in length) from A. baumannii, p80-1-2 (54-kb) and p94-2-tetX3 (42-kb) from A. indicus.

An analysis of their genetic environments showed that the tet(X3) genes were frequently located between the integrase (xerD) and resolvase genes. This implies that xerD-tet(X3)-resolvase may play an important role in the process of gene transfer. Furthermore, the tet(X3) gene may be transferred by ISCR2, which located downstream of xerD-tet(X3)-resolvase in all the plasmids, except p94-2-tetX3. It is interesting to note that the p34AB and p80-1-2 contain complete copies of ISCR2 on each side of xerD-tet(X3)-resolvase ( Figure 1B ). Moreover, a truncated transposase (ΔISCR2) ( Figure S2 ) was located upstream from xerD-tet(X3) or IS26-xerD-tet(X3) in all plasmids (except p94-2-tetX3), which implies that the complete ISCR2 may have existed previously. ISCR2 belongs to the IS91 family, which is transposed by an RC transposition mechanism that differs from those of other IS elements (Toleman and Walsh, 2010). It has been demonstrated that a 4609-bp circular intermediate occurs in p34AB (He et al., 2020b). IS91 was previously considered a rare element in the transfer of resistance genes, but it has been increasingly detected in recent studies (Bello-López et al., 2019).

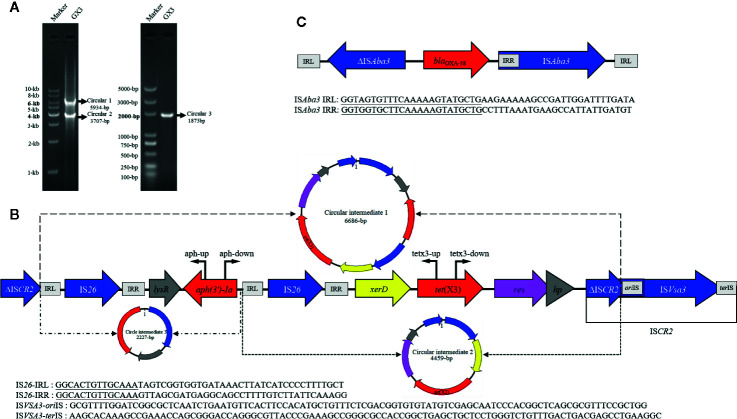

Previous studies have been shown that ISCR2 can move additional sequences located upstream from the transposase gene (Toleman et al., 2006). We used inverse PCR to examine whether this region could be mobilized by RC replication ( Figure 2A ). The inverse PCR primers used have been reported previously (He et al., 2020b). Interestingly, 5934-bp and 3707-bp amplicons were generated and a sequence analysis showed that both of them lacked the complete ISCR2 (IS26-LysR-aph(3’)-Ia-IS26-xerD-tet(X3)-resolvase-hp-ΔISCR2 (6686-bp) and IS26-xerD-tet(X3)-resolvase-hp-ΔISCR2 (4459-bp)) ( Figure 2B ). It is notable that oriIS and terIS were not detected in ΔISCR2. We also detected a minicircle containing aph(3’)-Ia (IS26-LysR-aph(3’)-Ia (2227-bp)) with an inverse PCR assay (aph-up: 5′-CGGTTTGGTTGATGCGAGTG-3′, aph-down:5′-GATTGTCGCACCTGATTGCC-3′) ( Figure 2B ). These results suggest that a circular intermediate was generated by IS26, which can disseminate antibiotic resistance genes via a translocatable unit (TU) containing only one copy of IS26 (Harmer and Hall, 2015). It is tempting to speculate that the 3′-end (GAAC) of ΔISCR2 is a specific target sequence in the TU in which 5′-GAAC or 5′-GTTC is the insertion target sequence in IS91 transfer (Toleman et al., 2006). IS26 also frequently occurs upstream from of tet(X3) in published plasmids recorded in the NCBI, and may increase the risk of tet(X3) dissemination ( Figure 1B ). The mechanism involved warrants further research.

Figure 2.

(A) Left: gel image of PCR products (circular 1 and circular 2) generated with the tetx3-up and tetx3-down primers. DNA ladder (1 kb) marker is used as the size standard. Right: PCR product (circular 3) generated with the aph-up and aph-down primers. DL5000 DNA Marker is used as the size standard. (B) Linear diagram of the genetic context of tet(X3) in the plasmids. The region of the circular intermediates is indicated with a dotted line and they are shown as circular graphs (circular intermediate 1, 6686 bp; circular intermediate 2, 4459 bp; circular intermediate 3, 2227 bp). Locations of primers used to map the targeted circular intermediates are shown with bent arrows. (C) Linear diagram of the genetic contexts of bla OXA-58 in the plasmids isolated in this study.

Analysis of the Genetic Context of bla OXA-58

We also identified the carbapenemase gene, bla OXA-58, in these isolates. The bla OXA-58 gene was all present in the tet(X3)-harboring plasmids, pGX3, pGX5, and pGX7 in our study. Further examination of the bla OXA-58 region revealed that a truncated ISAba3 element was located upstream of bla OXA-58 and a complete ISAba3 element on downstream in all plasmids ( Figure 2C ). This is consistent with a previous report that the bla OXA-58 gene was transferred by ISAba3 (Matos et al., 2019). It is notable that the isolates were resistant to imipenem (MIC, 8–16 mg/L), but they were susceptible to meropenem (MIC, 0.12–2 mg/L) ( Table S1 ). It may be due to bla OXA-58 hydrolyzes carbapenems weakly and often expresses poorly. Moreover, the insertion of an upstream ISAba3 can enhance expression of the bla OXA-58, but it is truncated in these strains (Hamidian and Nigro, 2019). Overall, our findings support the notion that the co-occurrence of bla OXA-58 and tet(X3) strengthens the risk of the dissemination of these plasmids.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the co-occurrence of tet(X3) and bla OXA-58 in plasmids identified from A. towneri. What is remarkable here is that, although A. towneri is an environmental bacterium, it was detected in the faeces of swine. pGX3 has a novel plasmid backbone containing MDR genes, which are similar to the backbone structures of pGX5 and pGX7, suggesting that they may be derived from the same ancestral MDR plasmid backbone. Like ISCR2, IS26 has been proved that it can generate a circular intermediate to transfer tet(X3), providing antibiotic resistance genes with a highly mobile genetic vehicle, although the mechanisms involved require further research.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), SRR11454657 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), SRR11454656 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), SRR11454655.

Author Contributions

JM, JW, and ZY conceived and designed the study. JF, YL, BY, and XW acquired the data. JM, RL, LB, and TH drafted the manuscript. JW critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 31702294, 31930110 and 31802230); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant numbers 2018T111114); Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (Grant No. 2019JQ-281) and China Agriculture Research System (grant numbers CARS-39-14). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2020.586507/full#supplementary-material

Neighbour-joining tree based on the plasmid replication initiator protein gene sequences, showing the phylogenetic positions of the tet(X3)-harboring plasmids from strains GX3, GX5, and GX7 (indicated by ●) and from some other representative related taxa. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentages of 1,000 replications) greater than 50% are shown at the branch points. Scale bar, 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide position.

Nucleotide sequence of ΔISCR2. Position of the transposase gene is indicated by green dots under the sequence. Predicted amino acid sequence of the transposase is given with the single-letter amino acid code, placed below the right nucleotide of each codon. Specific target sequence (-GAAC) is indicated with a black box.

References

- Barton B. M., Harding G. P., Zuccarelli A. J. (1995). A general method for detecting and sizing large plasmids. Anal. Biochem. 226, 235–240. 10.1006/abio.1995.1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello-López E., Castro-Jaimes S., Cevallos M., Rocha-Gracia R. D. C., Castañeda-Lucio M., Sáenz Y., et al. (2019). Resistome and a novel bla NDM-1-harboring plasmid of an Acinetobacter haemolyticus strain from a children's hospital in Puebla, Mexico. Microb. Drug Resist. 25, 1023–1031. 10.1089/mdr.2019.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2019). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-ninth Informational Supplement (Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; ). [Google Scholar]

- Hamidian M., Nigro S. J. (2019). Emergence, molecular mechanisms and global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii . Microb. Genom. 5, e000306. 10.1099/mgen.0.000306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C. J., Hall R. M. (2015). IS26-mediated precise excision of the IS26-aphA1a translocatable unit. mBio 6, e01866–e01815. 10.1128/mBio.01866-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T., Wang R., Liu D., Walsh T. R., Zhang R., Lv Y., et al. (2019). Emergence of plasmid-mediated high-level tigecycline resistance genes in animals and humans. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1450–1456. 10.1038/s41564-019-0445-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D., Wang L., Zhao S., Liu L., Liu J., Hu G., et al. (2020). A novel tigecycline resistance gene, tet(X6), on an SXT/R391 integrative and conjugative element in a Proteus genomospecies 6 isolate of retail meat origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 1159–1164. 10.1093/jac/dkaa012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T., Li R., Wei R., Liu D., Bai L., Zhang L., et al. (2020. a). Characterization of Acinetobacter indicus co-harbouring tet(X3) and bla NDM-1 of dairy cow origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 2693–2696. 10.1093/jac/dkaa182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T., Wei R., Li R., Zhang L., Sun L., Bao H., et al. (2020. b). Co-existence of tet(X4) and mcr-1 in two porcine Escherichia coli isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 764–766. 10.1093/jac/dkz510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji K., Xu Y., Sun J., Huang M., Jia X., Jiang C., et al. (2020). Harnessing efficient multiplex PCR methods to detect the expanding Tet(X) family of tigecycline resistance genes. Virulence 11, 49–56. 10.1080/21505594.2019.1706913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Liu Z., Peng K., Liu Y., Xiao X., Wang Z. (2019). Co-occurrence of two tet(X) variants in an Empedobacter brevis of shrimp origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e01636–e01619. 10.1128/AAC.01636-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos A. P., Cayô R., Almeida L. G. P., Streling A. P., Nodari C. S., Martins W., et al. (2019). Genetic characterization of plasmid-borne bla OXA-58 in distinct Acinetobacter Species. mSphere 4, e00376–e00319. 10.1128/mSphere.00376-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. J., Petty N. K., Beatson S. A. (2011). Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27, 1009–1010. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasina E., Haidich A. B., Kokkali S., Arvanitidou M. (2011). Efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of infectious diseases: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 11, 834–844. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70177-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toleman M. A., Bennett P. M., Walsh T. R. (2006). ISCR elements: novel gene-capturing systems of the 21st century? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 296–316. 10.1128/MMBR.00048-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toleman M. A., Walsh T. R. (2010). ISCR elements are key players in IncA/C plasmid evolution. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 3534. 10.1128/AAC.00383-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Stephan R., Karczmarczyk M., Yan Q., Hächler H., Fanning S. (2013). Molecular characterization of bla ESBL-harboring conjugative plasmids identified in multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli isolated from food-producing animals and healthy humans. Front. Microbiol. 4, 188. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Liu D., Lv Y., Cui L., Li Y., Li T., et al. (2019). Novel plasmid-mediated tet(X5) gene conferring resistance to tigecycline, eravacycline, and omadacycline in a clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e01326–e01319. 10.1128/AAC.01326-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Neighbour-joining tree based on the plasmid replication initiator protein gene sequences, showing the phylogenetic positions of the tet(X3)-harboring plasmids from strains GX3, GX5, and GX7 (indicated by ●) and from some other representative related taxa. Bootstrap values (expressed as percentages of 1,000 replications) greater than 50% are shown at the branch points. Scale bar, 0.05 substitutions per nucleotide position.

Nucleotide sequence of ΔISCR2. Position of the transposase gene is indicated by green dots under the sequence. Predicted amino acid sequence of the transposase is given with the single-letter amino acid code, placed below the right nucleotide of each codon. Specific target sequence (-GAAC) is indicated with a black box.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), SRR11454657 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), SRR11454656 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), SRR11454655.