Abstract

Patients with major presentations of alopecia experience physically harmful effects and psychological comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety. Oral minoxidil (OM) has been suggested by dermatologists as a potential remedy; however, its effectiveness remains unclear. This systematic review aims to collate published studies and to analyze the effect of OM among patients diagnosed with any type of alopecia. For this systematic review, Medline/PubMed, Cochrane Central, EMBASE, Web of Sciences, and Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Information System were searched for relevant studies from inception to September 21, 2019. Of 1960 studies retrieved in several electronic databases and three additional records identified though reference list from potentially eligible studies, nine studies (one randomized controlled trial and eight nonrandomized controlled trials) met the requirements and were used in our analysis. Although we found positive effects in favor of OM, this should be interpreted cautiously due to very low quality of the evidence of outcomes in the selected studies. Definitive conclusions are not possible without high-quality trials. This review has highlighted the absence of high-quality randomized controlled trials evaluating OM in the treatment of various types of alopecia. Given the mild adverse events of OM, future studies should also analyze doses and duration to maximize efficacy and decrease side effects.

Key words: Alopecia, evidence-based medicine, minoxidil, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Hair plays an important role in sensory function, provides thermal and physical insulation, and confers sociocultural characteristics in humans.[1,2] Hair production comprises a cycle of growth, shedding, and replacement, with around 50–100 hair lost per day as part of the normal physiological balance. However, unwanted hair loss (termed alopecia) is a clinical condition that develops when degenerative processes outpace hair regeneration.[3,4,5] There is a wide spectrum of types and etiologies of alopecia, including androgenetic alopecia (AGA), alopecia areata, scarring alopecia, and telogen effluvium types.[2] Therefore, a proper diagnosis is essential to determine the most appropriate treatment strategy for that individual. A detailed history is vital and should include interrogation of the presenting complaint, medical and family history, diet, and previous treatments. After this, a careful physical examination (including visual inspection and trichoscopy) should be performed.[6,7] After the diagnosis has been secured, various medications may be appropriate to reestablish the gross hair density and well-being.

The only Food and Drug Administration-approved pharmacological interventions for alopecia are the 5-alpha-reductase type 2 inhibitor finasteride (Propecia®) 1 mg (quantum dot; male-pattern hair loss [MPHL] only) and topical minoxidil (2%–5%) (twice a day; MPHL and female-pattern hair loss only).[8,9,10,11] Minoxidil (empirical formula C9H15N5O) is converted by sulfotransferase into minoxidil sulfate, the active ingredient that promotes hair growth by prolonging anagen and shortening the telogen/kenogen phase, thereby stimulating new hair (NH) production as the next anagen phase begins.[12] Minoxidil was first developed as a topically applied substance for male baldness in 1960 after the Upjohn Company observed increased hair growth as a side effect of oral minoxidil (OM) used to control blood pressure.[13] Since then, clinical trials have demonstrated topical minoxidil as an effective treatment for AGA. Unfortunately, response rates for topical minoxidil are variable (in part related to variations in sulfotransferase levels between individuals), and the regular topical applications to the scalp can be messy and poorly tolerated due to scalp irritation or hair breakage. For these reasons, OM has been suggested as an alternative treatment for alopecia, potentially limiting localized scalp side effects and allowing a higher drug concentration to maximizing treatment response and compliance.[14,15,16]

Although topical pharmaceutical formulation of minoxidil has been recognized throughout systematic reviews and meta-analysis to regrow hair in patients affected by different types of alopecia, data on the association between OM and hair growth remain inconsistent and unclear.[17,18,19] In this study, we aimed to systematically examine the evidence of an association of OM with hair growth.

METHODOLOGY

The protocol for this systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42019155760), and the completed review conforms to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P).[20]

Search strategy

In order to identify randomized clinical trial assessing the effects of OM in the hair follicle growth, we searched five independent databases to perform the sensitive literature search (publication up to August 2019): 1. PubMed/MEDLINE, 2. Cochrane Central, 3. EMBASE, 4. Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information, and 5. Web of Science. In addition, we searched for ongoing registered clinical trials at the National Institute of Health United States National Library of Medicine. There was no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register. We used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and non-MeSH terms in order to obtain target articles. Furthermore, a manual search of references of reports of included studies was conducted to further relevant studies.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) randomized controlled trials with crossover/parallel study designs, or nonrandomized controlled studies; (2) studies that were carried out on individuals diagnosed with any type of alopecia of any age; (3) studies that reported sufficient baseline and follow-up data of trials of hair growth/density (e.g., trichoscopic analysis, photographic documentation, biopsy analysis, validated severity scores, or quantitative hair count analysis - such as total hair density/cm2 [THD/cm2], density of terminal hair/cm2 [DTH/cm2], NH/cm2, and new terminal hair/cm2 [NTH/cm2]); also, data on patients' satisfaction, well-being, and adverse effects were included; and (4) studies conducted in a combined therapy (different drugs used at the same time, including OM).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies that were carried out on patients with no definite diagnosis of alopecia by a physician; (2) studies that did not provide sufficient information for outcomes in OM or control groups; and (3) case reports with <10 patients in total.

Data extraction

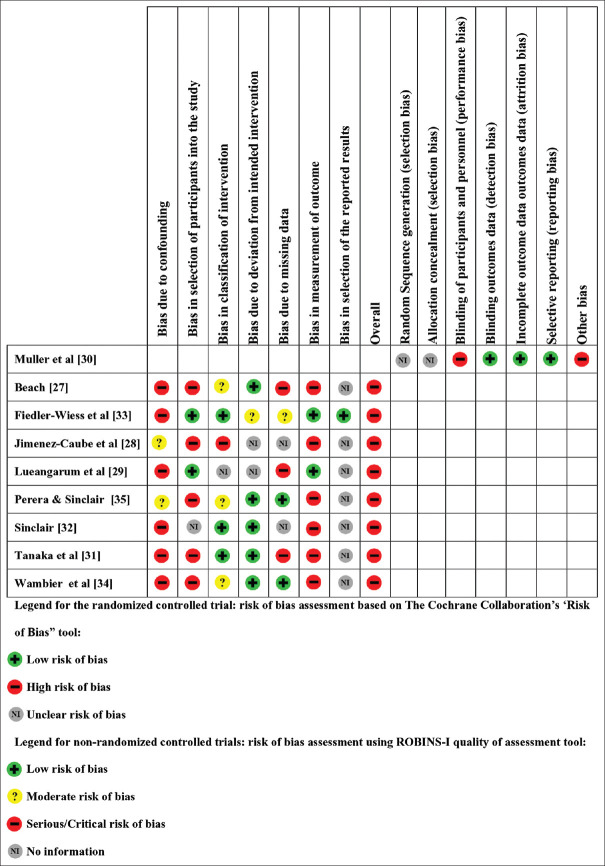

We uploaded electronic search results from the five defined databases to the Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute and summarized results using the PRISMA flow diagram [Figure 1].[21] Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of records identified without being blinded to authors, institutions, and journal name and assessed each study using the review eligibly criteria. In a case of disagreement between authors, a third expert resolved the conflict. If there was an absence in data reporting, the corresponding author was contacted via E-mail to obtain the required data. If there were missing data within potentially eligible studies, the corresponding author was contacted via E-mail to obtain the required data. The research group developed and piloted a data extraction sheet [Supplemental Material 1] to characterize studies and summarize outcomes. These extraction sheets included information such as first author's name, year of publication, age and gender of individuals, trial duration, study location, type and dosage of OM administration, study design, health status of participants, number of participants in each group, mean and standard deviation (SD) of outcome measures at baseline and posttrial, and/or changes in outcome measures from baseline to the end of the study. If a study reported multiple data points at various points in time, only the most recent data were included.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of records investigating effect of oral minoxidil in alopecia

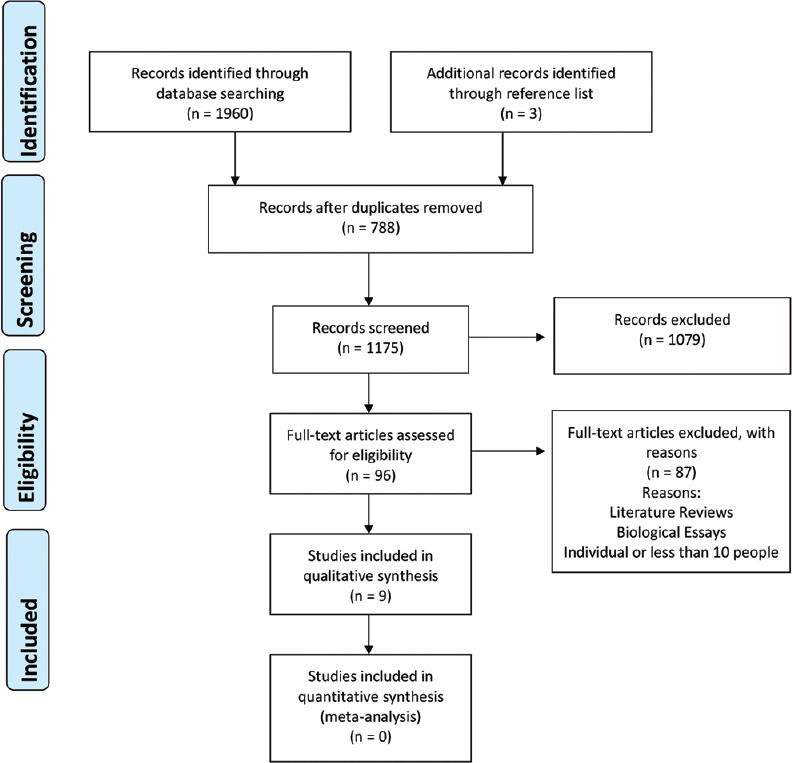

Quality assessment

Two independent research authors independently assessed the risk of bias of selected studies with input from content experts according to the Cochrane Collaboration's tool was used for assessing risk of bias.[22] Possible sources of bias in randomized trials include random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. The most common key sources of biases in dermatology are the nonrandomization of participants in trial, as well as no mutual blinding therapies. In addition, clinical research sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry is progressively reflecting measured outcomes. Three scores of yes, no, and unclear could be given to each aforementioned item, which resulted in classification of high risk, low risk, and unknown risk, respectively. For the randomized controlled trial, we used the software RevMan 5 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) to plot assessments.[23] For nonrandomized controlled studies, we used the updated Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I).[24]

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

In our protocol, we planned to use mean change and SD of the outcome measures to estimate the mean difference between the intervention group and the control group at follow-up. In addition, we also intended to evaluate possible heterogeneity among selected studies using I2, and if substantial heterogeneity (I2 >50%) existed, we explored precise reasons for this. However, due to limited number of studies, we considered the studies clinically heterogeneous and did perform any meta-analysis evaluation. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, United States of America)[25] and are referred as relative frequency and percentage. The adverse effects outcomes were qualitatively showed.

RESULTS

We identified 1960 studies through five selected database searches with duplicates: 656 references from MEDLINE, 400 from EMBASE, 1 from CENTRAL, 77 from Web of Sciences, and 826 from LILACS. After excluding 788 duplicates, we screened 1175 titles and abstracts. We retrieved full-text articles for the remaining 96 records, of which 87 were excluded due to study design (review articles). We found nine studies eligible that were eligible for inclusion in this review [Table 1]. Throughout reference list checking, we found three additional references. See Figure 1 for PRISMA diagram, in which presents the overall review pathway as well as the main characteristics of excluded studies.[35]

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected articles and its summary

| First author | Country and Sample | Study design and trial duration (months) | Type of alopecia and assessment tool (diagnosis and follow-up) | Intervention (treatment) | Control (comparator) | Measured outcomes | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. alopecia androgenetic | |||||||

| Beach[26] | Canada and 18 | Case series; patients’ average duration of prescription was 6 months | Androgenetic and traction alopecia; clinical diagnosis and patients’ report | OM* 1.25 mg, QD† | Patients after therapy were compared to baseline condition | Patient’s report (hair shedding and scalp hair) and side effects | 33% of patients reported decreased hair shedding28% of patients reported increased scalp hair |

| Jimenez-Cauhe[27] | Spain and 41 | Quasi-experimental; mean duration of treatment was 53 weeks | Androgenetic alopeciaClinical diagnosis and trichoscopy | OM of 2.5 mg-5.0 mg | Patients after therapy were compared to baseline condition | Photographic documentation pre- and posttreatment and side effects | 14.6% of patients showed marked improvement24.3% had mild improvement (monotherapy group) |

| Lueangarun[28] | Thailand and 30 | Quasi-experimental; duration of treatment was 24 weeks | Androgenetic alopecia; clinical diagnosis, Norwood-Hamilton scale, patient’s report | OM 5.0 mg, QD | Patients after therapy were compared to baseline condition | 7-point scale photography documentation, hair count, hair diameter, patient’s self-assessment | Photographic assessment revealed 100% improvementIncreased total hair count at the vertex from baseline to 26.0 hairs/cm2 (14.25%) and 35.1 hairs/cm2 (19.23%) (P=0.007) at week 12 and 24, respectively |

| Ramos[29] | Brazil and 50 | Randomized controlled study; duration of treatment was 24 weeks | Female-pattern hair loss; clinical diagnosis and trichoscopy | OM 1. 0 mg, QD | Topical minoxidil 5%, one a day | Pre- and post-treatment photographic documentation, Sinclair’s hair-shedding score, hair density, WAA-WoL¶ and side effects | Slight/great photographic evaluation improvement in 70% of patients using OMIncreased total hair count from baseline (164.6 hairs/cm2) to 184.7 hairs/cm2 at week 24Increased total terminal hair count from baseline (106. hairs/cm2) to 112.6 hairs/cm2 at week 24Improvement in the WAA-WoL |

| Tanaka[30] | Japan and 18.918 | Quasi-experimental; duration ranged from 6 to 12 months | Androgenetic alopecia; clinical diagnosis and patients’ report | Combination therapy (OF** 1.0 mg, QD + OM 2.5 mg + TM§, BID + injectable treatment) | Patients after therapy were compared to baseline condition | Patients’ report, pre- and posttreatment photographic documentation, and side effects | 60% and 80% of patients reported satisfaction with the results of the treatment after 6 and 12 months, respectively; |

| Sinclair[31] | Australia and 100 | Case series; treatment duration of 12 months | Female-pattern hair loss; clinical diagnosis | OM 0.25 mg, QD and spironolactone 25 mg, QD | Patients after therapy were compared to baseline condition | Sinclair’s hair-shedding score, hair density, blood pressure, side effects | Reduction in hair loss severity score was perceived for the treatment period (12 months) |

| II. Alopecia areata | |||||||

| Fiedler-Weiss[32] | USA and 65 | Quasi-experimental; mean time for cosmetic response 34.8 weeks | Alopecia areata; clinical diagnosis and scalp biopsy | OM 5.0mg, BID‡ | Patients after therapy were compared to baseline condition | Cosmetic response (terminal hair regrowth) and side effects | Cosmetic response was seen in 18% of patients |

| Wambier[33] | USA and 12 | Quasi-experimental; at least 6 months | Alopecia areata; clinical diagnosis, SALT | OT|| 5.0 mg-20 mg, BID, and OM 2.5 mg, QD (women) and BID (men) | Patients after therapy were compared to baseline condition | SALT# and side effects | 67% of patients achieved SALT75 (≥75% scalp hair regrowth) and 4 achieved SALT 11-74 (11%-74% scalp hair regrowth) |

| III. Telogen effluvium | |||||||

| Perera[34] | Australia and 36 | Quasi-experimental; duration ranged from 6 to 12 months | Telogen effluvium; clinical diagnosis, patients’ report and scalp biopsy | Compounding OM 0.25 mg-2.5 mg, QD | Patients after therapy were compared to baseline condition | Sinclair’s hair shedding score and side effects | Reduction in hair shedding score from baseline to 6 months of 1.7 (P<0.001) and to 12 months of 2.58 (P<0.001) |

*Oral minoxidil, †Quaque die (once a day), ‡Bis in die (twice a day), §Topical minoxidil, ||Oral tofacitinib, ¶ WAA-WoL: Women’s Androgenetic Alopecia Quality of Life Questionnaire, #SALT: Severity of Alopecia Tool, **Oral finasteride

Included studies

This systematic review includes one randomized controlled trial and eight nonrandomized controlled studies and yielded a pooled sample size of 19,270 patients. Regarding geographic representation of the studies included, we identified studies originating from the Americas,[26,27,30,34] Europe,[28] Oceania,[31,32] and Asia.[29,33] No study from Africa was included, and only two studies were in nondeveloped countries. The details of included studies are listed in Table 1. Years of publication ranged from 1980 to 2019, and most studies were published in English. OM was mostly given as tablets. The medication was extemporaneously compounded (doses ranged from 0.25 mg to 2.5 mg) in only one study. There was variation in the total oral dose and dose regimens for OM, ranging from 0.25 mg/day to 10.0 mg/day.

Excluded studies

We excluded 87 studies. Eight studies were strictly designed as biological experiments and eleven studies were literature reviews. Other excluded studies did not quantitatively assess the effects of OM. Some excluded articles were published in Portuguese, French, and Spanish but were translated before the final decision to exclude was made.

Incidence of side effects

All included records mentioned side effects associated with OM therapy, as shown in Table 2. The most relevant ones were hypertrichosis, postural hypotension, and lower-limb edema. However, the authors described the side effect as “mild” and mostly diluted with continued treatment.

Table 2.

Detailed adverse effects in the posttreatment assessment related to oral minoxidil

| First author | Posttreatment adverse effects |

|---|---|

| Beach[26] | Hypertrichosis (38.8%), fluid retention (5.5%), hypotensive symptoms (5.5%) |

| Fiedler-Weiss[32] | Hypertrichosis (17.0%), fluid retention, occasional episodes of headaches, depression, or lethargy in women; occasional episodes of palpitations or tachycardia after ingestion of caffeine, alcohol, or decongestants* |

| Jimenez-Caube[27] | Hypertrichosis (24.3%), lower-limb edema (4.8%), hair shredding (2.4%) |

| Lueangarun[28] | Hypertrichosis (93%), pedal edema (10%), ECG abnormality, including premature ventricular contractions and T-wave change (10% of patients) |

| Ramos[29] | Hypertrichosis (27.0%), edema of the limbs (4.0%) |

| Perera[34] | Hypertrichosis (38.8%), transient postural dizziness (5.5%)†, lower-limb edema (2.7%) |

| Sinclair[31] | Hypertrichosis (4%), urticaria (2%), hypotensive symptoms (2%) |

| Tanaka[30] | Swelling (0.22%), dizziness (0.15%) |

| Wambier[33] | Hypertrichosis (50.0%), acne (25.0%) |

*Study did not show quantitative data regarding most of adverse effect described, †Side effect resolved after continued treatment

Quality assessment

The risk of bias for each study is depicted in Figure 2. One randomized controlled trial was included and judged to have a high risk for bias due to lack of blinding of participants and personnel (open study design) and other biases, such as conflict of interest – one of the study authors was affiliated to a pharmaceutical company. Seven quasi-experimental studies were included and judged as having a high risk of bias due to missing data or inadequate measurement of outcomes. Most studies also had selection bias and other biases due to confounding factors (e.g., use of concomitant active drugs for alopecia). Overall, all included studies were associated with a high risk of bias.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: Review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for the included study

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to assess the effectiveness of OM in the treatment of different types of alopecia in human populations. We assessed nine studies (one randomized controlled trial and eight nonrandomized studies), involving a total of 19,270 patients. This high number of patients is fundamentally driven by one specific study (Tanaka et al.), which assessed 18,918 patients. Despite identifying many quasi-experimental studies during the search process and analysis, we could not carry out a meta-analysis as all selected articles had very different measurements of outcomes and methodologies. Overall, most of the outcomes presented in the selected studies were based on few data points, which were of poor quality in the majority of cases. Additionally, the ratings related to the quality of evidence among the included studies were considered as very low for the most relevant outcomes (including hair regrowth).

Interestingly, the positive effect of OM in hair regrowth in patients with various types of alopecia was suggested in all nine selected studies. However, the quality of evidence is extremely compromised due to risk of bias of included studies, heterogeneity, and the involvement or sponsorship of the pharmaceutical industry. This review highlights the need for accepted validated outcome measures in trichology trials to allow consistent interpretation of results across studies. Participants in the identified trials also experienced a range of adverse effects, such as hypertrichosis, hypotensive symptoms, and lower-limb edema, although these were generally mild in severity. We believe that our literature review and data synthesis will provide physicians and researchers with new insight to help decision-making for patients with hair loss.

Minoxidil was initially introduced as an oral antihypertensive agent in the late twentieth century because of its properties to treat ulcer and decrease blood pressure.[36,37] However, after researchers had found its off-labels effect in hair regrowth, in the 1980s, the Federal Drug Administration approved it as a topical solution for baldness treatment.[38,39] More recently, a study has suggested that a lower follicular enzymatic activity threshold is required for bioactivation of OM compared to topic minoxidil, suggesting that the scalp would be more susceptible to OM.[12] Based on the past literature, absorption of topical minoxidil appears to be slower and lesser when compared to OM.[40,41] In addition, as OM suffers liver metabolization and has a higher bioavailability compared to topical minoxidil, it is hypothesized that the oral formulation is more effective in treating hair loss in relation to topical formulation because of increased active compound in the hair follicle area. However, no previous studies had analyzed the in situ concentration of both treatment options.

Here, we identified studies evaluating the effect of OM in four different types of alopecia (alopecia areata, AGA, traction alopecia, and telogen effluvium). The doses of OM used in this review varied extremely, from 0.25 mg to 10 mg/day, in various regimens, from one to four times a day. The duration of the trials ranged from 6 to 12 months. Despite different administration regimens, studies had suggested that a minimum of 6 months is required for any cosmetic response.[14,16] However, more randomized clinical trials, with different doses and regimens, are needed to obtain a more precise information about posology. We did not analyze any study appraising the influence of OM in scarring/cicatricial alopecias. Considering the pathogenesis of AGA, OM might be an important mediator for clinical improvement, as shorten of telogen phase and prolongation of anagen phase is a proposed mechanism of action that counteracts the observed hair growth changes occurring in this disorder. In addition, a recent study showed in a cell model experiment that minoxidil caused a significant downregulation of 5α-reductase type 2 gene expressions (−0.22 fold change), compared with untreated control cells,[42] potentially suggesting an addition mechanism of action in AGA. Similarly, taking into account the pathophysiology of alopecia areata (inflammation and hair cycle changes), OM is likely to have a direct influence in the natural course of the disorder.[43] Clearly, additional high-quality studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of action of OM and its impact in the pathogenesis of different types of alopecia.

Adverse effects were one of the most commonly addressed outcomes associated with OM treatment. Hypertrichosis incidence ranged from 4.0% to 93.0% and fundamentally suggests that the drug also increased the anagen interval away from the scalp. However, hypertrichosis in unwanted body's zones was not associated with a low compliance in the selected studies and was frequently resolved with simple hair removal techniques, such as laser therapy, depilatory creams, waxing, and electrolysis. In addition, peripheral edema (0.22%–10.0%) was recognized in most of studies, associated with the known vasodilator effect of minoxidil and associated sodium and fluid retention. No severe hypotension side effects were recognized, and minor complications (i.e., headaches and dizziness) resolved spontaneously. In all analyzed studies (retrieving a total of 19,270 patients), only one patient declared discontinuation of treatment because of side effects (pedal edema).[28] Furthermore, one study stated that 33 patients discontinued taking OM because of lack of efficacy or personal reasons. Alternative, but not severe, adverse effects included headaches, depression, hair shedding, electrocardiogram abnormalities (including occasional premature ventricular contractions and T-wave changes), and acne. Considering potential adverse effects related to OM, it is essential to physicians to successfully perform the shared decision model, considering the best available evidence, understanding patients' fears and expectations over the treatment, reviewing previous therapies, and assessing the benefit versus risk associated with the intervention.[44]

Interestingly, it was noted a remarkable absence or inconsistent use of standardized alopecia assessment tools (pre- and posttreatment) that are both reliable and accurate. In selected studies, the data related to alopecia were measured and reported differently; thus, we could not mathematically combine them and conduct meta-analysis due to high heterogeneity. Regarding this, we suggest an evaluation tool for dermatologist when approaching any type of alopecia whether in interventional studies or clinical trials. A high-quality global photographic assessment (before, during, and posttreatment) is fundamental, and each alopecia must be evaluated in a different pattern.[45] For instance, alopecia areata, Severity of Alopecia Tool,[46,47] is the most suitable. For AGA, there are several scales, but the most used are Norwood–Hamilton for males and Ludwig and Olsen for females.[47] Trichoscopy (representing results as THD/cm2, DTH/cm2, NH/cm2, and NTH/cm2) using TrichoScan[48] is also a useful tool to measure the effect of a treatment in AGA.

A major strength of this systematic review is that we adhered to guidelines of the PRISMA and Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews throughout the full revision process: planning the review, defining search strategies and selecting adequate studies, collecting data, assessing the risk of bias, statistically analyzing extracted data, and interpreting results analysis. Regarding this, the authors of this review made every effort to minimize bias during the review execution, independently extracting data, and assessing bias. An important limitation of the present study is the fact that only one randomized controlled trial was identified through our sensitive search strategy, evidencing a lack of literature related to OM, and its use for alopecia. Therefore, future works should focus on assessing, via high-quality randomized controlled trials, OM at different doses for appropriate and safe use of OM for the treatment of alopecia.

CONCLUSION

Based on this review, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of OM for alopecia in human populations. OM appears to have positive effects on improving hair regrowth in patients with different types of alopecia, but data in this review are of very low quality, suggesting that future research is extremely likely to have a fundamental impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect. Furthermore, OM is also related to various adverse events, and four out of the nine included studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies. Therefore, currently, the available evidence to support the use of OM in any type of alopecia is very low-to-low quality.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental Material 1

Effect of oral minoxidil for alopecia: Systematic review and meta-analysis

| Researcher name or abbreviation: |

| Extraction date: |

Important note: This form contains, essentially, all information to be analyzed and extracted in the target selected studies. Potentially, not all characteristics can be extracted in a single study. Even if only one information is obtained, please, still consider this study for the systematic review

1. General information*

| Date form completed (dd/mm/yyyy) |

|---|

| Name of person extracting data |

| Title of paper and resource |

| Study number (ID) |

| Country where the study was conducted: |

| Possible conflicts of interest |

2. Eligibility*

| Study characteristics | Review inclusion criteria | Location in text (page) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of study | ||

| Population description | ||

| Types of outcome measured | ||

| Aim of study | ||

| Sample size | ||

| Results identified | ||

| Decision (with reasons for either inclusion or exclusion) | ||

| Notes |

3. Outcomes measured and results identified

| Outcomes measure | Result (unit) |

|---|---|

| Dosage of oral minoxidil and length | |

| Alopecia assessment tool and type of alopecia | |

| Initial total hair density | |

| Posttreatment total hair density | |

| Initial density of terminal hair/cm2 | |

| Posttreatment density of terminal hair/cm2 | |

| New hair/cm2 | |

| New terminal hair/cm2 | |

| Patients satisfaction | |

| Drugs used as a combination therapy | |

| Notes |

Footnotes

Data extraction form inspired by Islam RM, Oldroyd J, Karim MN, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of, and risk factors for, pelvic floor disorders in community dwelling women in low and middle.income countries: a protocol study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015626. [doi: 10.1136/bmjopen.2016.015626].

REFERENCES

- 1.Deborah Pergament, It’s not just hair: Historical and cultural considerations for an emerging technology. Chicago Kent Law Rev. 1999;75:21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoover E, Alhajj M, Flores JL. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island, (Florida): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Jan, [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Physiology. Hair [Updated 2019 Aug 10] Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499948 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NYU Langone Health. Types of Hair Loss. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Sep 20]. Available from: https://nyulangone.org/conditions/hair-loss/types .

- 4.American Academy of Dermatology. What kids shoudl know about how hair grows. [Accessed on January 28 2020 Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.aad.org/public/parents-kids/healthy-habits/parents/kids/hair-grows .

- 5.Santos JD. [Characterization of hair before and after of both chemical and physical treatments using Raman spectroscopy, infrared, and electronic microscopy] PhD Thesis. Federal University of Juiz de Fora: Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil. 2017. [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: http://repositorio.ufjf.br:8080/jspui/bitstream/ufjf/5936/1/jordanadiasdossantos.pdf .

- 6.Azulay RD. [Dermatology] 7th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro J, Hordinsky M. Evaluation and Diagnosis of Hair Loss. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-and-diagnosis-of-hair-loss#H638362 .

- 8.U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s. Example Drug Facts Label for Minoxidil Topical Solution 2% for Men and Women. U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s. [Accessed on January 25 2020 Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/72189/download .

- 9.U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s. Highlights of prescribing information-Finasteride U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s. [Accessed on: January 27 2020 Last accessed on 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/020788s020s021s023lbl.pdf .

- 10.Finn DA, Beadles-Bohling AS, Beckley EH, Ford MM, Gililland KR, Gorin-Meyer RE, et al. A new look at the 5alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride. CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12:53–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SW, Juhasz M, Mobasher P, Ekelem C, Mesinkovska NA. A systematic review of topical finasteride in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:457–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos PM, Goren A, Sinclair R, Miot HA. Oral minoxidil bio-activation by hair follicle outer root sheath cell sulfotransferase enzymes predicts clinical efficacy in female pattern hair loss. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e40–1. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zins GR. The history of the development of minoxidil. Clin Dermatol. 1988;6:132–47. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(88)90078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vañó-Galván S, Camacho F. New treatments for hair loss. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:221–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadick NS. New-Generation Therapies for the Treatment of Hair Loss in Men. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Najem I, Chen H. Use of low-level laser therapy in treatment of the androgenic alopecia, the first systematic review. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:252–7. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2017.1400174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Schoones J. Interventions for female pattern hair loss. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD007628. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007628.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freire PC, Riera R, Martimbianco AL, Petri V, Atallah AN. Minoxidil for patchy alopecia areata: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1792–9. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adil A, Godwin M. The effectiveness of treatments for androgenetic alopecia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:136–4100000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan – A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Altam DG, Gøtzche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Review Manager (RevMan) Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.StataCorp, Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beach RA. Case series of oral minoxidil for androgenetic and traction alopecia: Tolerability & the five C's of oral therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:e12707. doi: 10.1111/dth.12707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez-Cauhe J, Corralo-Saceda D, Rodrigues-Barata R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, Moreno-Arrones OM, Fernandez-Nieto D, et al. Effectiveness and safety of low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:648–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lueangarun S, Panchaprateep R, Tempark T, Noppakun N. Efficacy and safety of oral minoxidil 5 mg daily during 24-week treatment in male androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:AB113. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramos PM, Sinclair RD, Kasprzak M, Mio HA. Minoxidil 1 mg oral versus minoxidil 5% solution topically for the treatment of female pattern hair loss: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:252–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka Y, Aso T, Ono J, Hosoi R, Kaneko T. Androgenetic Alopecia Treatment in Asian Men. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:32–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinclair RD. Female pattern hair loss: A pilot study investigating combination therapy with low-dose oral minoxidil and spironolactone. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:104–9. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiedler-Weiss VC, Rumsfield J, Buys CM, West DP, Wendrow A. Evaluation of oral minoxidil in the treatment of alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1488–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wambier CG, Craiglow BG, King BA. Combination tofacitinib and oral minoxidil treatment for severe alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019:S0190-9622(19)32688-X. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perera E, Sinclair R. Treatment of chronic telogen effluvium with oral minoxidil: A retrospective study. F1000Res. 2017;6:1650. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11775.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bury M. The Medicalization of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions into Treatable Disorders - by Conrad P. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2019;31:147–148. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01145_1.x. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Limas CJ, Freis ED. Minoxidil in severe hypertension with renal failure Effect of its addition to conventional antihypertensive drugs. Am J Cardiol. 1973;31:355–61. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(73)90268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Pharmacology Review. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, FDA. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton JL, Marshall A. Hypertrichosis due to minoxidil. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101(5):593–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toxicology Data Network, Minoxidil, in U.S National Library of Medicine. TOXNET: United States of America; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eller MG, Szpunar GJ, Della-Coletta AA. Absorption of minoxidil after topical application: Effect of frequency and site of application. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;45:396–402. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1989.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pekmezci E, Turkoglu M. Minoxidil acts as an antiandrogen: A study of 5alpha-reductase type 2 gene expression in a human keratinocyte cell line. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pratt CH, King LE, Jr, Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17011. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta M, Mysore V. Classifications of patterned hair loss: A review. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2016;9:3–12. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.178536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olsen EA, Canfield D. SALT II: A new take on the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) for determining percentage scalp hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1268–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olsen EA, Hordinsky M, Price VH, Roberts JL, Shapiro J, Canfield D, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines--Part II. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. J Am Acad Der matol. 2004;51:440–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffmann R. TrichoScan: A novel tool for the analysis of hair growth in vivo. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2003;8:109–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]