Abstract

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is associated with a high mortality caused by rapidly progressive multiple organ failure. SFTS virus induces immunosuppression, mediated by interleukin-10 production, reduction of CD3+ and CD4+ T cells, and cytokine storms, and this may lead to various complications in critical SFTS patients. Recently, there have been reports of cases of invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis (IPA) in patients with SFTS in the absence of predisposing factors of IPA. However, there is no known relationship between SFTS and mycosis. Here, we report a SFTS patient with a low CD4+ T-cell count and a high viral load, who developed possible IPA in the absence of common risk factors for mycosis. This case adds to the evidence that IPA may occur as a complication of SFTS.

Key Words: Aspergillosis, galactomannan, phlebovirus, pneumonia, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) is a tick-borne virus in the Phenuiviridae family.[1,2] It has developed among East Asian populations involved in agricultural or outdoor activities.[2,3] SFTS is associated with high mortality, caused by rapidly progressive multiple organ failure. There have recently been reports of SFTS complicated by invasive Aspergillosis in the absence of other predisposing factors.[4,5] However, there was no known correlation between SFTS and mycoses. We describe a patient with mild SFTS who developed possible invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis (IPA) in the absence of known risk factors for fungal pneumonia.

CASE REPORT

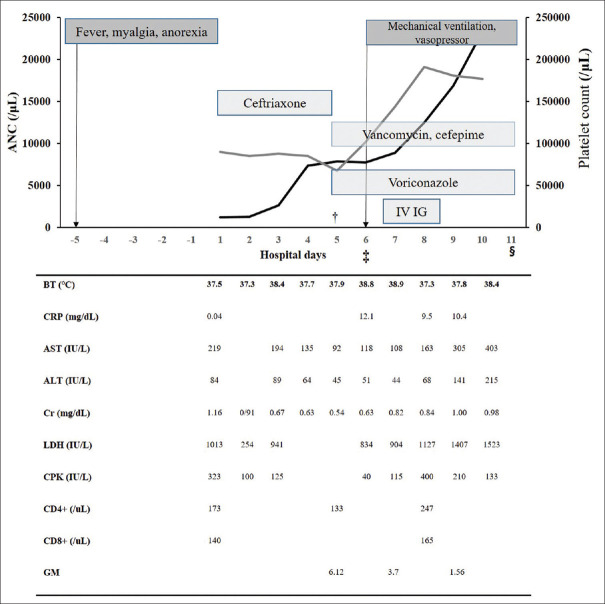

A previously healthy 92-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of fever, myalgia, anorexia, and general weakness. She had no medical history of note, other than hypertension, and could take care of herself. She lived in a rural region and was frequently in contact with grass and domestic animals. On physical examination, she was alert, and an insect bite was found on her left shoulder. Her initial vital signs included the following: blood pressure of 94/54 mmHg, pulse rates of 85 beats per minute, temperature of 37.5°C, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 95% while breathing room air. Her clinical course is summarized in Figure 1. Blood tests revealed leukopenia and thrombocytopenia (white blood cell count: 1,300 cells/μL, normal range: 4,000–10,000/μL; platelet count: 100 × 103/μL, normal range: 150–450 × 103/μL), and elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase: 88 IU/L, normal range: 8–38 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase: 40 IU/L, normal range: 4–44 IU/L).

Figure 1.

Clinical course of the patient with SFTS, †: The patient moved to the intensive care unit; ‡: The patient newly developed a dyspnea on the 5th hospital day; §: The patient died with respiratory failure, refractory hypotension, and metabolic acidosis on the 11th hospital day; ANC: Absolute neutrophil counts; IV IG: Intravenous immunoglobulin; BT: Body temperature; CRP: C-reactive protein; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; Cr: Creatinine; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; CPK: Creatine phosphokinase

Ceftriaxone was administered as an empirical antibiotic drug at 24-h intervals. On day 1 of her hospitalization, SFTSV was detected by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, with a SFTSV viral load of 186,606 copies/mL. She was treated conservatively and remained stable until the day 4. On day 5, she developed sudden-onset pneumonia, confirmed by chest X-ray and respiratory failure. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) of the lung revealed subtle bronchiolitis in both the upper lobes and bronchial wall thickening in both lower lobes. Cefepime and vancomycin were administered as empirical antibiotic drugs for hospital-acquired pneumonia, and 6 mg of voriconazole per kg was loaded at 12-h intervals for the treatment of possible IPA, and then maintained at 4 mg/kg. She was found to have a serum Aspergillus galactomannan antigen (GM) level of 6.1 (reference: 0–0.49) on day 5, and 3.7 and 1.6 on days 7 and 9, respectively. On day 6, she was started on mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU). Gram stain and culture, fungus culture were performed on bronchoalveolar fluid obtained on bronchoscopy. However, her septic shock status did not improve, and multifocal consolidations were observed on chest X-ray. We added intravenous immunoglobulin on day 7. She died on day 11. No other pathogens including viruses were identified from her sputum and blood.

DISCUSSION

This case of SFTS with possible IPA occurred in an old woman with clinically mild SFTS and a changing serum lymphocyte profile. Although her lymphocyte counts improved during the acute phase, her CD4+ lymphocyte count remained low. She died of acute respiratory distress syndrome, possibly caused by the IPA.

To date, there have been some of reports of SFTS infections with complicated by IPA. In view of the risk of IPA in patients with SFTS, our unit has a protocol of routine GM testing, and fungal culture of respiratory secretions of all patients with SFTS who develop pneumonia. SFTS patients with pneumonia are immediately started on voriconazole, with the dose adjusted according to the GM level.

Because SFTSV suppresses the immune system by a mechanism of interleukin-10 production, leading to a reduction of CD4+ T-cells, hypercytokinemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia.[6,7] SFTSV infection may be complicated by secondary infections caused by various other pathogens. In a recent study, septic shock, ICU admission, ventilator care, and mortality were found to be higher in SFTS patients with IPA than in those without IPA.[6] However, physicians may not consider SFTS as a risk factor for mycosis.

IPA can occur in severely immunocompromised hosts, especially those with severe and prolonged neutropenia.[8] One study found that 60% of ICU patients who developed IPA did not have traditional risk factors for IPA, and corticosteroid administration and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have been reported as risk factors for IPA in critically ill patients. Another study found that corticosteroids were used in 58% of patients with SFTS.[9] A summary of 15 cases of IPA with SFTS that have been reported previously in Table 1.[4,6,10] The patients had a median age of 65 years (range: 42–88 years), and 60% were female. None of the patients had any of the common risk factors of IPA, and ten of the 15 patients were (67%) died. All patients were leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, had a very high GM level, and were diagnosed with IPA within 2 weeks of the onset of SFTS. The CT findings were variable, and included consolidation, cavitation, nodules, and infiltration. In an autopsy case, both lungs showed marked pulmonary hemorrhage, numerous fungal parenchymal lesions, angioinvasion with thrombosis, and infarction.[10] Histopathological examination revealed necrotizing inflammation of her lungs with Aspergillus invading many bronchi and blood vessels. Our patient had relatively mild neutropenia, a high GM level, a low CD4 count, and bilateral lung infiltration, and she was not treated with corticosteroids. These findings are consistent with the previous reports of patients with SFTS and IPA. We hypothesize that SFTS is a risk factor of mycosis by another mechanism: T-cell lymphopenia. T-cell lymphopenia, which may be due to a viral-associated hemophagocytic syndrome, is commonly observed during the early stage SFTS, particularly in fatal cases, and T-cell levels improved during the recovery phase. Lymphopenia may limit the initiation and maintenance of effective humoral and cytotoxic T-cell immunity, leading to immunosuppression. The extent of the decrease in the percentage of CD4+ T cells has been observed to be associated with the severity of SFTS.[7] We hypothesize that in SFTS, T-cell lymphopenia, especially CD4+ T cell loss, may lead to an increased risk of fungal pneumonia because our patient had sustained CD4+ T-cell depletion and died, despite voriconazole being administered immediately according to the protocol for the study of IPA in patients with SFTS.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome

| Ref | Case | Age | Sex | Medical history | Diagnosis of IPA | Species of aspergillosis | Titer of GM | (1-3) ß-D glucan (pg/ml)‡ | Computed tomography finding | Antifungal drugs | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [4] | 1 | 72 | Male | HTN | Proven | A. flavus | 5.4 | 617.4 | Consolidation | VCZ | Death |

| [4] | 2 | 42 | Female | None | Proven | A. fumigatus | 5.6 | 134.8 | Cavity | VCZ, CSP, L-AmB | Death |

| [4] | 3 | 58 | Female | None | Probable | A. flavus | 5.22 | 243.3 | Left lung infiltration | VCZ | Death |

| [4] | 4 | 65 | Male | COPD | Probable | A. fumigatus | 4.3 | 461.8 | cavity | None | Death |

| [6] | 5 | 54 | Female | None | PIPA† | A. flavus | 2.44 | N/A | Consolidation | None | Death |

| [6] | 6 | 61 | Female | None | PIPA† | A. fumigatus | 5.65 | N/A | Consolidation, nodules | L-AmB | Improved |

| [6] | 7 | 66 | Male | None | PIPA† | A. terrus | >10 | N/A | Consolidation, nodules, GGO | VCZ | Improved |

| [6] | 8 | 50 | Male | Lung disease | PIPA† | A. fumigatus | 0.94 | N/A | Consolidation, GGO | None | Death |

| [6] | 9 | 60 | Male | DM | PIPA† | N/A | 6.71 | 276.8 | Consolidation, nodules, GGO | VCZ | Improved |

| [6] | 10 | 73 | Male | DM | PIPA† | A. oryzae | >10 | 539.6 | Aggravated plain X-ray | L-AmB | Death |

| [6] | 11 | 66 | Female | None | PIPA† | N/A | 3.52 | >1000 | Consolidation, nodules, GGO | VCZ | Improved |

| [6] | 12 | 74 | Female | DM | PIPA† | N/A | 1.38 | 366.4 | Consolidation | None | Death |

| [6] | 13 | 62 | Female | DM, lung disease | PIPA† | A. fumigatus | >10 | 386.2 | GGO, nodules | VCZ | Improved |

| [10] | 14* | 83 | Female | N/A | Proven | N/A | N/A | 261.7 | N/A | AmB | Death |

| [10] | 15* | 88 | Male | N/A | Proven | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | None | Death |

*These were autopsy cases, †SFTS patients do not have classic host factors according to the EORTC/MSG criteria, “putative aspergillosis concept is a new diagnostic IPA category defined by the aspergillosis ICU algorithm to encompass a broader range of patients at risk,[6] ‡Reference range of (1-3) ß-D glucan is <3.8 pg/ml. Ref: Number of reference, HTN: Hypertension, IPA: Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, PIPA: Putative IPA, N/A: Not applicable, A. flavus: Aspergillus flavus, A. fumigatus: Aspergillus fumigatus, A. terrus: Aspergillus terrus, A. oryzae: Aspergillus oryzae, GM: Galactomannan (ref: 0-0.5), CT: Computed tomography, COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, VCZ: Voriconazole, CSP: Caspofungin, L-AmB: Liposomal amphotericin B, DM: Diabetes mellitus, GGO: Ground-glass opacity, EORTC/MSG: European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer/Mycosis Study Group, ICU: Intensive care unit

Our case had some limitations: first, we did not conduct a follow-up chest CT scan; and second, we did not perform a post-mortem examination because it was against the wishes of the patient's family.

In conclusion, we have described a case of SFTS and possible IPA in a patient with a low CD4 T+-cell count and a high SFTSV viral load. Physicians should be aware that SFTS may be complicated by various opportunistic infections and should consider the risk of mycosis in SFTS, even in the absence of common risk factors for mycosis.

Research quality and ethics statement

The authors of this manuscript declare that this scientific work complies with reporting quality, formatting, and reproducibility guidelines set forth by the EQUATOR Network. The authors also attest that this clinical investigation was determined to not require institutional review board/ethics committee review, and the corresponding protocol/approval number is not applicable.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by a research grant from the Jeju National University Hospital in 2018 (Grant no. 2018-31).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams MJ, Lefkowitz EJ, King AM, Harrach B, Harrison RL, Knowles NJ, et al. Changes to taxonomy and the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2017) Arch Virol. 2017;162:2505–38. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Q, He B, Huang SY, Wei F, Zhu XQ. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:763–72. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70718-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo JR, Lee KH, Heo ST. Surveillance results for family members of patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:903–7. doi: 10.1111/zph.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X, Yu Z, Qian Y, Dong D, Hao Y, Liu N, et al. Clinical features of fatal severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome that is complicated by invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24:422–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaguchi K, Koga Y, Yagi T, Nakahara T, Todani M, Fujita M, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome complicated with pseudomembranous Aspergillus tracheobronchitis in a patient without apparent risk factors for invasive Aspergillosis: A case report. Intern Med. 2019;58:3589–92. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.3257-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae S, Hwang HJ, Kim MY, Kim MJ, Chong YP, Lee SO, et al. Invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis in patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:1491–4. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MM, Zhang WJ, Weng XF, Li MY, Liu J, Xiong Y, et al. CD4 T cell loss and Th2 and Th17 bias are associated with the severity of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) Clin Immunol. 2018;195:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson TF, Thomson GR, 3rd, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, et al. Practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of Aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e1–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato H, Yamagishi T, Shimada T, Matsui T, Shimojima M, Saijo M, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan, 2013-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiraki T, Yoshimitsu M, Suzuki T, Goto Y, Higashi M, Yokoyama S, et al. Two autopsy cases of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) in Japan: A pathognomonic histological feature and unique complication of SFTS. Pathol Int. 2014;64:569–75. doi: 10.1111/pin.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]