Abstract

Objective:

We report a 35 year-old male with childhood learning disability and early onset dementia who is homozygous for the A431E variant in the PSEN1 gene. Presenilin1 mutations are associated with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s dementia with young and somewhat stereotyped onset. Such variants may cause Alzheimer’s dementia through aberrant processing of amyloid precursor protein through effects on γ-secretase activity. γ-secretase is involved in the cleavage of many proteins critical to normal function, including brain development. Therefore, manifestations in persons without normal Presenilin1 function is of interest.

Methods:

Clinical evaluation including family history, examination, brain MRI, and genetic analysis.

Results:

Our patient had mild developmental delay, chronic nighttime behavioral disturbance, and onset of progressive cognitive deficits at age 33. Clinical evaluation demonstrated spastic paraparesis and pseudobulbar affect. Brain MRI revealed cerebral atrophy disproportionate to age. Chronic microhemorrhages within bilateral occipital, temporal, and right frontal lobes were seen. Sanger sequencing confirmed homozygosity for the A431E variant in PSEN1, which is a known pathogenic variant causing autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s dementia.

Conclusions:

Our report demonstrates that homozygosity for pathogenic Presenilin1 variants is compatible with life, though may cause a more aggressive phenotype with younger age of onset and possibly REM behavior disorder.

Keywords: PSEN1, homozygote, Alzheimer’s disease, spastic paraparesis, A431E, autosomal dominant, REM behavior disorder

Introduction

While variants in the genes coding for Presenilin-1 (PSEN1), Presenilin-2 (PSEN2), and amyloid precursor protein (APP) are known to cause early onset Alzheimer disease (AD) which are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, the effects of homozygosity for these variants has not been well-documented. Variants in PSEN1 affect the endopeptidase activity of the γ-secretase complex and are thought to predispose to AD through their effects on APP cleavage1. Such variants cause an altered preponderance of the γ-secretase cleavage products of APP such as Aβ37, Aβ38, Aβ392, Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ433. Transgenic animal models suggest that some PSEN1 variants may be embryonic lethal when homozygous3 though others show more aggressive development of AD pathology4. As γ-secretase cleaves many proteins5, some of which play roles in neural development, it is possible that aberrant γ-secretase function leads to abnormal brain development.

Kosik et al6 identified 6 individuals homozygous for the c.839A>C (p.Glu280Ala, E280A) substitution in PSEN1 from an extended kindred in Colombia7. Of the 6, 2 met criteria for dementia at 5 and 13 years prior to the mean age of dementia diagnosis associated with this variant. One homozygous child had mild intellectual disability. As age of symptom onset and dementia diagnosis is frequently consistent within families and within autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease (ADAD) variants8, this provides evidence for a more aggressive phenotype associated with homozygosity. The developmental delay seen in one of 6 such persons suggests an effect of homozygosity on neural development, though this single case is far from conclusive. The characterization of other persons homozygous for variants in PSEN1 is therefore of interest.

Case Report

Our patient completed high school at the age of 18 but reportedly required remedial classes earlier in his education. He achieved gainful employment in semi-skilled labor. At age 28 he was noted to have episodes of calling out in his sleep, apparently in association with nightmares. His first symptom of progressive disease manifested as alexia at age 33 followed soon thereafter with memory and gait impairment and falls due to lower extremity spasticity. The patient had an unremarkable medical history until the onset of symptoms.

Family History:

The family history on both the parents’ sides were strongly positive for dementia of onset around age 40 in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. The index patient’s parents were first cousins with the paternal and maternal grandfathers being brothers. His father had onset of AD symptoms at age 38, dying at age 45. His mother died at age 54 from AD that started at around 50 years of age. An older sister was noted to have cognitive impairment from infancy but was lost to follow up. Our extensive review of the family history, focused on the presence of neurodegenerative disease, did not suggest an overall tendency towards intellectual impairment. A second-degree relative had the onset of memory problems at age 39 and died at the age of 47, with brain donation for neuropathological examination. During life, the relative was shown to be heterozygous for the A431E variant in PSEN1.

Clinical Findings:

On examination at age 36, the patient was alert and oriented to name and location, but not to the year or month. Speech was fluent, though naming and repetition were impaired. Comprehension was intact with one step commands but impaired with multistep commands. MMSE score was 14/30. He had brisk reflexes, greater in the legs than in the arms. His tone was increased at his ankles and he was unable to fully dorsiflex his feet. His gait was slow, stiff and unsteady.

Diagnostic Assessment:

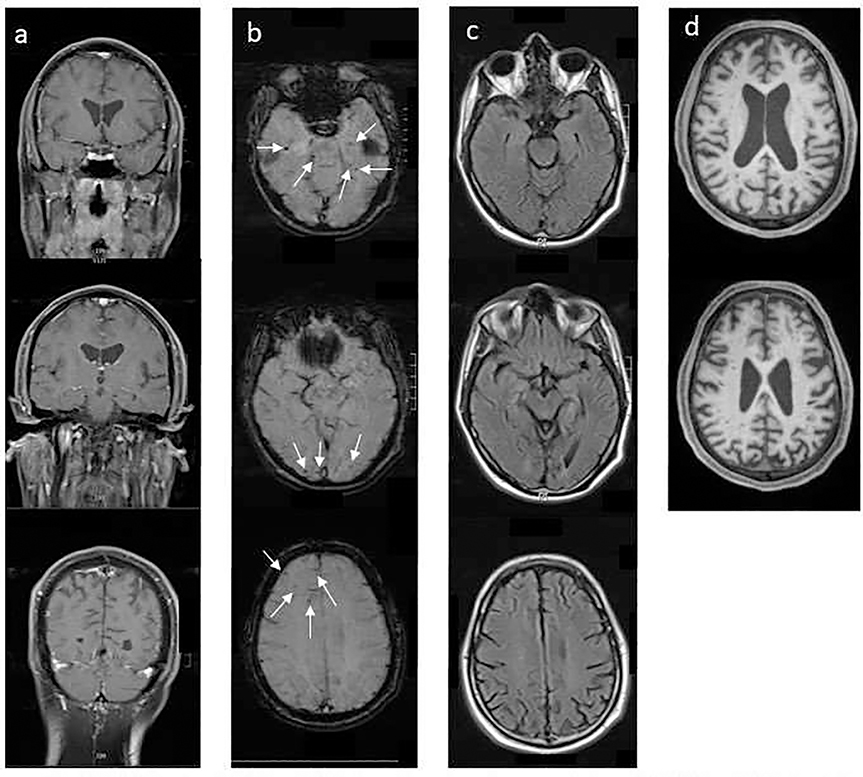

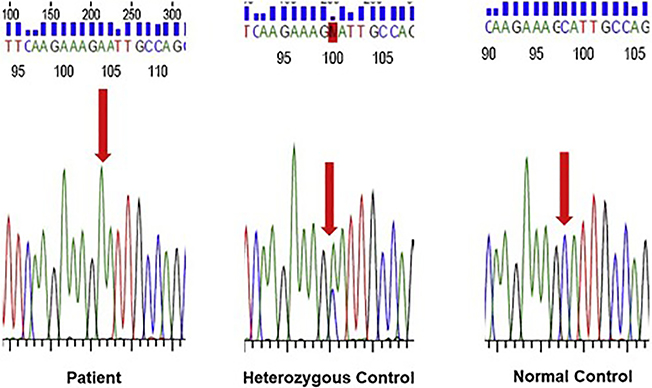

MRI brain (Figure 1) revealed cerebral atrophy disproportionate for age with parietal lobe predominance. Multiple chronic microhemorrhages were seen within the bilateral occipital, temporal, and right frontal lobes on SWI. MPRAGE was acquired later and revealed substantial increased perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale bilaterally. Sanger sequencing performed twice using independent primer pairs demonstrated homozygosity for the A431E variant in PSEN1 (Figure 2).

Fig. 1.

MRI brain. (a) T1 weighted post contrast coronal view. (b) SWI weighted axial view demonstrating micro-hemorrhages. (c) FLAIR sequence demonstrating pattern of atrophy. (d) MPRAGE sequence on 11 month follow up showing substantially increased perivascular spaces.

Fig. 2.

Sanger sequencing demonstrating homozygosity for the A431E variant in PSEN1.

Follow-up and Outcomes:

Over the next 6 months, the spastic paraparesis progressed rapidly with increasing dependence on assistive devices, from intermittent cane use to alternating walker and wheelchair use. Labile moods responded to the combination of dextromethorphan/quinidine and citalopram. Memory further declined to include profound rapid forgetting. When seen at age 37 he had an MMSE score of 8/30, a Clinical Dementia Rating scale score of 3 (severe dementia) and requires full time assistance with activities of daily living. He is unable to walk independently and has bradykinesia with arm rigidity but no tremor or cogwheeling.

Discussion

(ADAD) is caused by the presence of essentially fully-penetrant variants in one of three genes; PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP. Persons with ADAD, particularly when due to PSEN1 variants, can have features atypical for AD including myoclonus, pseudobulbar affect, and gait abnormalities due to spastic paraparesis9. The A431E substitution is a well-characterized pathogenic variant apparently arising as a founder effect in Jalisco State in Mexico10, 11. It is associated with early spastic paraparesis12 in approximately 45% of cases and has an average age of symptom onset of 40 years and of dementia diagnosis at 4210. Neuropathological examination sometimes reveals atypical “cotton wool” amyloid plaques and Lewy Bodies. While cotton wool plaques and spastic paraparesis can be independent of one another, they have been associated with numerous PSEN1 variants that include deletions in exon 9, insertions into exon 6, codeletion I83/M84, and substitutions such as P264L, P284L, E280G, N405S, and P436Q13 in addition to A431E. The neuropathologically examined relative was found to have frequent neuritic and cotton wool plaques and grade 3 amyloid angiopathy in widespread areas of cortex. Numerous Lewy Bodies and Lewy neurites in cortex as well as in the midbrain, pons, and medulla were also evident with anti-synuclein immunostaining (Ghetti et al, in preparation).

Our patient had a broadly similar phenotype though with symptoms consistent with REM behavior disorder (RBD) and the onset of progressive symptoms at age 33 and dementia diagnosis at age 35. He had significant progression in his cognitive and gait deficits over 6 months’ time at age 36, suggesting a particularly aggressive form of the disease. MRI at age 37 revealed lobar microhemorrhages and enlarged perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale, consistent with the presence of CAA(1) which is universally found in neuropathologically examined persons with the A431E PSEN1 mutation. He had been independently functional, gaining meaningful employment and supporting others. His full sister, on the other hand, was never able to live independently. Unfortunately, her genetic status and specifics regarding her development, course, and fate are unknown.

Though this is a single case of homozygosity for the A431E variant, our observations are consistent with those of Kosik et al6 of persons homozygous for the E280A substitution. That is, homozygosity for PSEN1 variants is compatible with life and can present with a phenotype similar to that of heterozygotes. The E280A cases’ ages of onset were also suggestive of a more aggressive form of the disease though all reported patients’ (including the current one) ages of onset were within the ranges previously described in association with heterozygosity for their respective variants. Both reports are consistent with, though far from conclusive for, intellectual deficits being associated with homozygosity.

Like other variants in PSEN1, the A431E substitution has been shown to be associated with an abnormal proportion of APP cleavage products of different lengths, suggesting a potential pathogenic disease mechanism2. The effects of PSEN1 variants on γ-secretase cleavage are quantitative, rather than qualitative. As such, a more aggressive form of illness with a generally similar phenotype might be anticipated in homozygotes. Though our data and those of Kosik et al6 are inconclusive regarding the presence of life-long intellectual impairment in persons homozygous for PSEN1 variants, they raise the possibility of a PSEN1 function in human development. Animal studies indicate a role of PSEN1 in neuronal differentiation and migration14–16 and a human case of AD with onset at age 29 in association with a PSEN1 variant was found to have ectopic neurons in white matter17. In the only known description of homozygosity for an APP variant (A713T), there did not appear to be a more aggressive phenotype in 3 homozygotes relative to their heterozygous family members18. This raises the possibility that the more aggressive phenotype apparent in PSEN1 homozygotes may be due to effects of these variants upstream from and independent of APP processing. However, the lack of a comprehensive premorbid intellectual history in our patient and the likelihood of homozygosity for a multitude of other loci in our patient and his sister due to the consanguinity of their parents leave this an open question.

Of interest is the patient’s history of dream-enactment behavior. Though confirmation by polysomnography is lacking, the potential presence of RBD is consistent with the known propensity for persons with ADAD to develop Lewy Body pathology19, 20 as was found in the brainstem of the index patient’s second degree relative. Should development of Lewy Body pathology in the brainstem be an early event in ADAD, the “premorbid” presence of RBD might be expected but has not been reported previously to our knowledge.

In summary, this case confirms that homozygosity for some PSEN1 variants are compatible with life but appear to lead to a more aggressive, though qualitatively similar phenotype. Despite the indirectness of the evidence presented herein, the possibility of a role for PSEN1 in brain and intellectual development deserves further study, particularly in light its potential as a target in AD therapeutics.

Highlights:

Homozygous autosomal dominant mutations in Presenilin-1 are compatible with life.

The homozygous state seems to confer a more severe phenotype, with earlier clinical onset and more rapid progression of neurodegeneration.

The homozygous state for A431E in PSEN1 may present with earlier onset, but are otherwise phenotypically similar to the heterozygous state and include spastic paraparesis, cortical atrophy, cerebral microhemorrhages, and dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We thank the family for their cooperation with the study and their permission to publish this case report. We would also like to thank Bernardino Ghetti for his valuable input.

Funding Sources: This study was supported by NIH U01 AG-051218 and P50 AG-005142.

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors report no conflicts relevant to the current report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, et al. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 1996;2:864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portelius E, Andreasson U, Ringman JM, et al. Distinct cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta peptide signatures in sporadic and PSEN1 A431E-associated familial Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2010;5:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito T, Suemoto T, Brouwers N, et al. Potent amyloidogenicity and pathogenicity of Abeta43. Nat Neurosci 2011;14:1023–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willuweit A, Velden J, Godemann R, et al. Early-onset and robust amyloid pathology in a new homozygous mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 2009;4:e7931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haapasalo A, Kovacs DM. The many substrates of presenilin/gamma-secretase. J Alzheimers Dis 2011;25:3–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosik KS, Munoz C, Lopez L, et al. Homozygosity of the autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease presenilin 1 E280A mutation. Neurology 2015;84:206–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lalli MA, Cox HC, Arcila ML, et al. Origin of the PSEN1 E280A mutation causing early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:S277–S283 e210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryman DC, Acosta-Baena N, Aisen PS, et al. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 2014;83:253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi A, Ringman JM, Lee AS, Juarez KO, Mendez MF. Comparison of clinical characteristics between familial and non-familial early onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol 2012;259:2182–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murrell J, Ghetti B, Cochran E, et al. The A431E mutation in PSEN1 causing familial Alzheimer’s disease originating in Jalisco State, Mexico: an additional fifteen families. Neurogenetics 2006;7:277–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yescas P, Huertas-Vazquez A, Villarreal-Molina MT, et al. Founder effect for the Ala431Glu mutation of the presenilin 1 gene causing early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in Mexican families. Neurogenetics 2006;7:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soosman SK, Joseph-Mathurin N, Braskie MN, et al. Widespread white matter and conduction defects in PSEN1-related spastic paraparesis. Neurobiol Aging 2016;47:201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlstrom H, Brooks WS, Kwok JB, et al. Variable phenotype of Alzheimer’s disease with spastic paraparesis. J Neurochem 2008;104:573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Handler M, Yang X, Shen J. Presenilin-1 regulates neuronal differentiation during neurogenesis. Development 2000;127:2593–2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selkoe D, Kopan R. Notch and Presenilin: regulated intramembrane proteolysis links development and degeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci 2003;26:565–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gadadhar A, Marr R, Lazarov O. Presenilin-1 regulates neural progenitor cell differentiation in the adult brain. J Neurosci 2011;31:2615–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takao M, Ghetti B, Murrell JR, et al. Ectopic white matter neurons, a developmental abnormality that may be caused by the PSEN1 S169L mutation in a case of familial AD with myoclonus and seizures. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2001;60:1137–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conidi ME, Bernardi L, Puccio G, et al. Homozygous carriers of APP A713T mutation in an autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease family. Neurology 2015;84:2266–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leverenz JB, Fishel MA, Peskind ER, et al. Lewy body pathology in familial Alzheimer disease: evidence for disease- and mutation-specific pathologic phenotype. Arch Neurol 2006;63:370–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ringman JM, Monsell S, Ng DW, et al. Neuropathology of Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer Disease in the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center Database. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]