Abstract

Background

Cancer patients, particularly those on active anticancer treatment, are reportedly at a high risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection and death. This study aimed to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 whilst on anticancer treatment in a developing country.

Methods

This is a retrospective observational study of all adult cancer patients at Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Pakistan, from March 15, 2020 to July 10, 2020, diagnosed with COVID-19 within 4 weeks of receiving anticancer treatment, where a purposive sampling was performed. Cancer patients who did not receive anticancer treatment and clinical or radiological diagnosis of COVID-19 without a positive reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test were excluded. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality after 30 days of COVID-19 test. Data was analyzed with SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical parameters were computed using chi-square test, keeping p value < 0.05 as significant.

Results

A total of 201 cancer patients with COVID-19 were analyzed. The median age of patients was 45 (18–78) years. Mild symptoms were present in 162 (80.6%) patients, whereas severe symptoms were present in 39 (19.4%) patients. The risk of death was statistically significant (p < .05) amongst patients with age greater than 50 years, metastatic disease, and ongoing palliative anticancer treatment. Anticancer treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy, and surgery) received within preceding 4 weeks had no statistically significant (p > .05) impact on mortality.

Conclusions

In cancer patients with COVID-19, mortality appears to be principally driven by age, advanced stage of the disease, and palliative intent of cancer treatment. We did not identify evidence that cancer patients on chemotherapy are at significant risk of mortality from COVID-19 correlating to those not on chemotherapy.

Keywords: Cancer, COVID-19, Outcome, Pakistan

Introduction

Patients with cancer have been identified to be at a high risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. The case fatality rate amongst the cancer patients has previously been shown to be almost double than that in the normal population at 5.6% [1]. Moreover, it is assumed that the risk of mortality is further amplified if the cancer patients are on active anticancer therapy.

A study from China established an increased risk of severe infection and poorer outcomes in cancer patients [2]. In the UK Coronavirus Cancer Monitoring Project (UKCCMP), COVID-19-positive cancer patients with advanced age and comorbidities had a significantly higher mortality [3]. This study did not reveal a significant impact of cancer treatment on mortality. Another European study revealed Karnofsky performance status <60, relapsed cancer, male sex, and respiratory manifestations as self-reliant risk factors for death in patients who are on active anticancer treatment [4]. The above studies described the impact of COVID-19 infection in cancer patients on active anticancer treatment. However, all these studies are from developed countries, and this correlation has not yet been studied in low- and middle-income countries.

This study, PakOncCovid19 (POC19), is the first study in Pakistan which evaluated the clinical features and outcomes of cancer patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 within 4 weeks of anticancer treatment. We also focused on identifying the possible risk factors in these patients which can lead to complications or death. This will aid in early recognition and timely management of the COVID-19-positive patients who are on active anticancer treatment.

Methodology

POC19 is a retrospective study of cancer patients with COVID-19 infection, diagnosed on the basis of nasopharyngeal reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), at Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre (SKMCH & RC), Pakistan. Clinical data were extracted from the hospital information system. The study was accepted and approved by the Institutional Review Board of SKMCH & RC.

The study population includes all adult patients who received anticancer treatment within 4 weeks of COVID-19 diagnosis, selected through non-probability purposive sampling. We evaluated all histologically confirmed cancer patients who were diagnosed with COVID-19 from March 15, 2020 to July 10, 2020. The active anticancer treatment includes chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy, and cancer-related surgery. Patients not undergoing active anticancer treatment and COVID-19-suspected patients based on radiological or clinical suspicion with a negative RT-PCR were excluded.

The primary outcome of our study was 30-day all-cause mortality. The study variables included age, sex, indications for COVID-19 testing (COVID-19 symptoms, pre-procedure screening, and incidental radiological finding confirmed with RT-PCR), primary cancer status (primary site localized, primary site advanced, and metastatic), type of malignancy (solid and haematological), the intent of treatment (palliative, curative), and severity of COVID-19 infection (mild/severe course).

Primary cancer was defined as localized when the solid organ tumor was deemed surgically resectable. Primary cancer was defined as advanced when the primary tumor was unsuitable for complete resection and metastatic cancer was a tumor with distant metastasis. The intent of anticancer treatment was defined as palliative when the intent was disease control, whereas curative anticancer treatment included radical intent involving surgery, neoadjuvant, and adjuvant treatment modalities.

The severity of the clinical course was divided into mild and severe. We modified the national criteria for the severity of the clinical course to ascertain the patient groups [5]. Patients diagnosed with mild COVID-19 infection were either asymptomatic or had symptoms with oxygen saturation of ≥94% on room air at the time of diagnosis. Patients diagnosed with severe infection had oxygen saturation of ≤93% on room air, septic shock, or any organ failure requiring treatment in the intensive care unit.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square test was applied using severity (mild and severe) and outcome (recovered and death) as dependent variables to see their association with different demographics (age and sex) and clinical characteristics, such as the type of anticancer treatment, intent of treatment, stage at presentation, severity of COVID-19 symptoms, and presence of comorbidities. The significance level was demarcated as a two-tailed p < .05.

The OS (overall survival) was updated as of August 10, 2020, and follow-up calls were made after 30 days of the initial presentation of each cancer patient with COVID-19 infection.

Results

Clinical characteristics of cancer patients with COVID-19

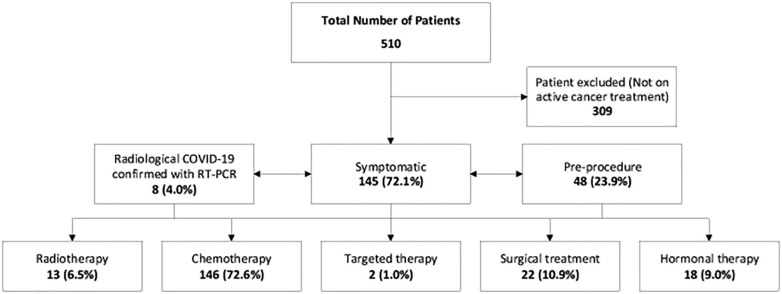

A total of 510 cancer patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were reviewed at SKMCH & RC, Pakistan, from March 15, 2020 to July 10, 2020. We identified 201 cancer patients infected with COVID-19 and receiving active anticancer treatment. The median age of the patients was 45 years, ranging from 18 years to 78 years. This includes 86 (42.8%) males and 115 (57.2%) females, with 162 (80.6%) mild cases and 39 (19.4%) severe cases. As shown in Fig. 1 , the majority of the patients (145 [72.1%]) were symptomatic with COVID-19 infection, 48 (23.9%) patients were found to be COVID-19-positive on pre-procedure screening, and eight (4.0%) patients tested positive on RT-PCR for COVID-19 after they were found to have incidental radiological features suggestive of COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Outlining the Patient Selection flow.

The breakdown of active anticancer treatment patients included in the study is as follows; chemotherapy (146 [72.6%]), hormonal therapy (18 [9.0%]), radiation therapy (13 [6.5%]), cancer-related surgical treatment (22 [10.9%]), and targeted agents (2 [1.0%]). Breast cancer (74 [36.8%]) was the most common cancer, followed by gastrointestinal cancer (28 [13.9%]), genitourinary cancer (21 [10.4%]), and others (Table 1 ). Haematological cancer was present in 33 (16.4%) patients and 168 (83.6%) patients had solid malignancy. There were 137 (68.2%) patients with localized cancer, 20 (10.0%) patients with locally advanced cancer, and 44 (21.9%) patients with metastatic disease. The most common COVID-19-related symptoms were fever (104 [51.7%]), cough (67 [33.3%]), and shortness of breath (24 [11.9%]). Comorbidities were observed in 52 patients and hypertension was the most common comorbidity present in 44 patients, followed by diabetes in 10 patients, while four patients had hypertension along with diabetes and ischemic heart disease in two patients.

Table 1.

Type of Cancer of Study Population.

|

Type of cancer |

Total (N = 201) |

|---|---|

| N (%) | |

| Breast cancer | 74 (36.8) |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 36 (17.9) |

| Genitourinary cancer | 26 (12.9) |

| Lymphoma | 18 (9) |

| Leukemia | 16 (8) |

| Head and neck cancer | 13 (6.5) |

| Sarcoma | 8 (4) |

| Gynecological cancer | 7 (3.5) |

| Lung cancer | 3 (1.5) |

Outcomes

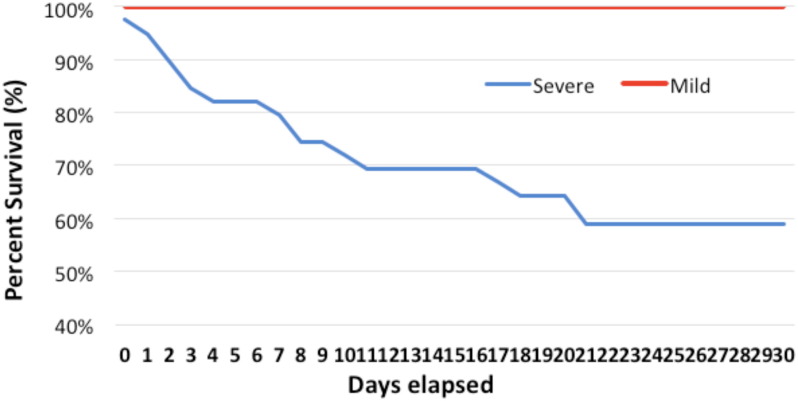

All patient outcomes (dead or recovered) were updated after 30 days of their initial presentation with COVID-19 infection. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. As shown in Table 2 , 39 patients presented with a severe form of COVID-19 infection, out of which 16 patients died. The remaining patients were diagnosed with mild COVID-19 infection, who remained stable for 30 days and recovered uneventfully Fig. 2. This also included the patients with incidental COVID-19 diagnosis during pre-procedure screening and incidental radiological findings confirmed with RT-PCR.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Study Population and its Distribution Based on the Severity of COVID-19.

|

Intent |

Total | Severity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Severe | p | |||

| (N = 201) | (n = 162) | (n = 39) | |||

| N (%) | |||||

| Treatment | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 146 (72.6) | 116 (79.5) | 30 (20.5) | .506 | |

| Hormonal therapy | 18 (9) | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | .349 | |

| Radiation | 13 (6.5) | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | .534 | |

| Surgical treatment | 22 (10.9) | 21 (95.5) | 1 (4.5) | .062 | |

| Targeted | 2 (1) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | .274 | |

| Stage at presentation | |||||

| Localized | 137 (68.2) | 117 (85.4) | 20 (14.6) | <.05 | |

| Locally advanced | 20 (10) | 14 (70) | 6 (30) | .209 | |

| Metastatic | 44 (21.9) | 31 (70.5) | 13 (29.5) | .055 | |

| Treatment outcome | |||||

| Recovered | 185 (92) | 162 (87.6) | 23 (12.4) | <.05 | |

| Death | 16 (8) | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | ||

| Asymptomatic | |||||

| Symptomatic | 141 (70.1) | 102 (72.3) | 39 (27.7) | <.05 | |

| Asymptomatic | 60 (29.9) | 60 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Fever | 104 (51.7) | 73 (70.2) | 31 (29.8) | <.05 | |

| Cough | 67 (33.3) | 45 (67.2) | 22 (32.8) | <.05 | |

| Chills | 5 (2.5) | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | 0.977 | |

| Myalgia | 22 (10.69) | 14 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | <.05 | |

| Sore throat | 19 (9.5) | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | .448 | |

| Shortness of breath | 24 (11.9) | 8 (33.3) | 16 (66.7) | <.05 | |

Fig. 2.

Survival Proportion of Mild and Severe COVID 19 Patients: Survival proportion of the patients was counted from the initial presentation with COVID-19 infection until 30 days.

Patients with mild disease were managed on an outpatient basis with symptomatic treatment. Out of 39 patients with severe COVID-19 infection, 10 patients were managed in the intensive care unit, whereas the remaining patients were managed in the ward. The only targeted therapy used was tociluzumab for five patients, out of which two died.

The mortality was statistically significant (p < .05) in patients aged older than 50 years compared with those aged 50 years or below, as shown in Table 3 . The overall mortality was 10/55 (18.2%) in cancer patients aged above 50 years and six/146 (4.1%) in those aged below 50 years.

Table 3.

Clinical Characteristics and its Impact on Outcome in Cancer Patients with COVID-19.

| Intent | Total | Outcome |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovered | Death | ||||

| (N = 201) | (n = 162) | (n = 39) | |||

| N (%) | |||||

| Age (yr) | |||||

| ≤50 | 146 (72.6) | 140 (95.9) | 6 (4.1) | <.05 | |

| >50 | 55 (27.4) | 45 (81.8) | 10 (18.2) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 86 (42.8) | 79 (91.9) | 7 (8.1) | .936 | |

| Female | 115 (57.2) | 106 (92.9) | 9 (7.8) | ||

| Type of cancer | |||||

| Solid | 168 (83.6) | 156 (92.9) | 12 (7.1) | .337 | |

| Hematological | 33 (16.4) | 29 (87.9) | 4 (12.1) | ||

| Treatment | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 146 (72.6) | 134 (91.8) | 12 (8.2) | .826 | |

| No chemotherapya | 55 (27.4) | 51 (92.7) | 4 (7.3) | ||

| Stage at presentation | |||||

| Localized | 137 (68.2) | 132 (96.4) | 5 (3.6) | <.05 | |

| Locally advanced and metastaticb | 64 (31.8) | 53 (82.8) | 11 (17.2) | ||

| Severity | |||||

| Severe | 39 (19.4) | 23 (59) | 16 (41) | <.05 | |

| Mild | 162 (80.6) | 162 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Intent of Treatment | |||||

| Curative | 161 (80.1) | 154 (95.7) | 7 (4.3) | <.05 | |

| Palliative | 40 (19.9) | 31 (77.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Comorbid | 52 (25.9) | 45 (86.5) | 7 (13.5) | .090 | |

| No comorbid | 149 (74.1) | 140 (94) | 9 (6) | ||

Radiation therapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy, and surgery (death in 2, 2, 0, and 0 patients, respectively).

Patients with locally advanced and metastatic disease: three/20 and eight/44, respectively.

There were a total of 16 deaths out of which 12 patients were post-chemotherapy, 2 patients were on hormonal therapy, and two patients received radiotherapy in a period of 4 weeks of their COVID-19 detection. No case of fatality was reported in patients who had cancer-related surgery or targeted anticancer therapy.

Most of the deceased patients (8/44 [18.2%]) had metastatic disease, followed by three/20 (15.0%) with locally advanced disease and only five/137 (3.65%) patients with localized disease. Compared with patients who had localized disease, mortality was statistically significant (p < .05) in those who had locally advanced and metastatic disease. Mortality was also statistically significant (p < .05) among patients with severe COVID-19 infection at presentation and who were on palliative intent anticancer treatment.

Of all those COVID-19-positive cancer patients, seven/161 (4.3%) patients who died received curative anticancer treatments and nine/40 (22.5%) patients received palliative treatment.

The type of anticancer treatment received within the preceding 4 weeks of COVID 19 infection was not statistically significant on the severity of the disease (p > .05).

Discussion

Patients with cancer and particularly those on active anticancer treatment are at a greater risk of a severe form of COVID-19 infection due to their immunosuppression [6]. In Pakistani population, the COVID-19-related mortality is 2–3% [5]. The worldwide COVID-19-related mortality is much higher in cancer population [7]. To the best of our knowledge, POC19 is the first retrospective observational study and this is also the largest study from a developing country to describe the clinical features and outcomes in cancer patients who received anticancer treatment within the preceding 4 weeks of COVID-19 diagnosis.

In a cohort study of patients with COVID-19 from Wuhan, China, the risk of severe disease was more than three times higher amongst the 230 patients with cancer than in matched controls [2]. Furthermore, the course of COVID-19 is much more severe in cancer patients on active anticancer treatment [3]. This study showed a similar percentage of severe infection in cancer patients with COVID-19, as described in previously observed studies.

The majority of patients in our study were aged below 50 years, which is a characteristic feature of the cancer population in Pakistan [8]. A 10-year data of breast cancer patients from Pakistan highlighted the age of presentation being one and a half decade earlier in Pakistan than in developed countries [9]. Similar trend was shown in oral cavity cancer and colonic cancer [8], [10]. In COVID-19, age has been an important determinant of mortality, as shown in a meta-analysis of 611,583 patients, with exponential increase in mortality after 50 years of age [11]. Older age is a significant independent risk factor of mortality in COVID-19 patients [12]. This fact could be influenced by both the physiological ageing process and comorbidities that contribute to a higher risk of complications from COVID-19 infection [13]. It was also established that age above 50 years was an independent risk factor for increased fatality and severity of COVID-19 infection.

A meta-analysis of data from four retrospective studies concluded that patients who received active anticancer treatment within 2–4 weeks of developing COVID-19 were associated with a nearly fourfold increased rate of in-hospital death compared with not having received such treatment [14]. The mortality can be up to 20% in cancer patients with COVID-19 in this meta-analysis. The mortality in UKCCMP is 27% in COVID-19-positive cancer patients on active treatment [3]. A unique aspect of our results is the lower mortality in our study than in the above mentioned studies; this difference in mortality can be attributed to the younger age of cancer onset in Pakistan. Being a developing country, we also faced the issue of limited resources along with shortage of other supportive treatment modalities for COVID-19, such as oxygen, antibiotics, and availability of the latest trial drugs like tocilizumab and remedesivir.

Accumulating data suggest that the likelihood of COVID-19-related severe illness and death is higher among the cancer patients with metastatic disease. The study by Assaad et al. [4] showed an increased risk of mortality in metastatic and relapsed cancer patients with COVID-19. The majority of cancer patients who died in our study also had locally advanced and metastatic disease; this difference was statistically significant compared with the patients who had localized disease at the time of diagnosis of COVID-19.

In our study, there were 30 patients with severe and 116 with mild COVID-19 infection who received chemotherapy in the preceding 4 weeks. There were 12 deaths observed in the chemotherapy group with severe infection, while 18 patients recovered within the 30 days of the study period. In an analysis of international COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium registry data on over 900 patients with active malignancy who were diagnosed with COVID-19 infection over 1 month, the use of anticancer treatment within 4 weeks of infection was not related with higher 30-day mortality rates [7]. These results were supported by another analysis of UKCCMP registery of patients with active cancer and symptomatic COVID-19 infection [3]. In this study, it is also concluded that cytotoxic chemotherapy which is given 4 weeks prior to COVID-19 diagnosis is not a statistically substantial contributor to more severe disease or a predictor of death from COVID-19 infection, when correlated with patients having cancer who have not received chemotherapy in that period. Therefore, it is ideal to individualize decisions regarding anticancer therapy amidst COVID-19 pandemic, taking into account factors such as the curability of cancer, risks of progression with treatment delay, and local incidence of COVID-19 and availability of resources.

We found that 52 out of 201 cancer patients had comorbidities, with 41 patients in the mild group and 11 in the severe group. One or more comorbidities were observed in nine severe patients who died. There was no significant statistical difference in deaths among patients who had comorbidities compared with those who did not have comorbidties.

As suggested in the American Society of Anesthesiologists guidelines, testing for COVID-19 should be performed for all patients prior to elective surgery and that surgery should be postponed until the patient has recovered from COVID-19 infection [7]. This screening is essential to protect the health care professionals from COVID-19 and to decrease the risk of nosocomial transmission of COVID-19. Our study revealed that 56/201 (27.9%) of asymptomatic patients with cancer had COVID-19 diagnosed during pre-procedural screening (48/56 [23.9%]) and after being highlighted on radiological investigations (8 [4%]), as shown in Fig. 1. All these patients remained well during the 30-day follow-up period.

There were some limitations in this study, as this was a retrospective analysis based on an observational design without a control group. Additionally, a limited number of patients received COVID-19-targetted therapies; therefore, it is difficult to accurately comment about its impact on patient outcome. We included only RT-PCR-positive patients, which can exclude a significant number of patients due to false-negative results. Identifying the characteristics of patients having cancer with COVID-19 infection who are at risk of a severe complication or death would be prudentn to form definitive precautionary measures and also to adapt to clinical trials. Further studies are needed to determine the optimal screening frequency for patients undergoing anticancer therapy cycles.

Conclusions

The mortality rate in COVID-19 cancer patients at 30 days is higher among patients with additional risk factors such as old age, metastatic disease, and palliative intent anticancer treatment received in the preceding 4 weeks of COVID-19 infection. Our study did not reveal higher COVID-19-related mortality in cancer patients undergoing active anticancer treatment in a developing country, comparable to existing evidence from developed countries, despite limited resources. Further studies dedicated to cancer patients on active cancer treatment will add in defining the future until preventive treatments, such as a vaccine, have been found.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the presented idea, devised and supervised the project and proof outline, developed the theory and performed the computations, took the lead in writing the manuscript including abstract, methodology, results, outcomes, discussion, and conclusion: JA

Wrote the manuscript: KS, ARF, MTA, SK

Interpreted the results and worked on the manuscript in terms of methodology, discussion, and conclusion: KS, ARF.

Performed and verified the analytic calculations and the numerical simulations: MTA

Conceived the presented idea: AR

Designed the model and the computational framework, analyzed the data: AR, SK

Designed the figures: SK.

All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge assistance from Farhad Ali, Khyber College of Dentistry, Peshawar, Pakistan and Sundus Amin and Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Peshawar, Pakistan.

References

- 1.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., Wang W., Li J., Xu K., et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee L.Y.W., Cazier J.B., Starkey T., Turnbull C.D., Kerr R., Middleton G. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1919–1926. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assaad S., Avrillon V., Fournier M.L., Mastroianni B., Russias B., Swalduz A., et al. High mortality rate in cancer patients with symptoms of COVID-19 with or without detectable SARS-COV-2 on RT-PCR. Eur J Cancer. 2020;135:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahmood SF, Nasir N, Sarfaraz S, Baqi S, Jehan F, Qamar F, et al. Clinical management guidelines for COVID-19 infection. Version 3. http://covid.gov.pk/new_guidelines/04July2020_20200704_Clinical_Management_Guidelines_for_COVID-19_infections_1203.pdf; 2020 [accessed 17 December 2020].

- 6.Meng Y., Lu W., Guo E., Liu J., Yang B., Wu P., et al. Cancer history is an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A propensity score-matched analysis. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:1. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00907-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuderer N.M., Choueiri T.K., Shah D.P., Shyr Y., Rubinstein S.M., Rivera D.R., et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anwar N., Badar F., Yusuf M.A. Profile of patients with colorectal cancer at a tertiary care cancer hospital in Pakistan. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1138:199–203. doi: 10.1196/annals.1414.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khokher S., Qureshi M.U., Riaz M., Akhtar N., Saleem A. Clinicopathologic profile of breast cancer patients in Pakistan: Ten years data of a local cancer hospital. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:693–698. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.2.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Camargo C.M., Voti L., Guerra-Yi M., Chapuis F., Mazuir M., Curado M.P. Oral cavity cancer in developed and in developing countries: Population-based incidence. Head Neck. 2010;32:357–367. doi: 10.1002/hed.21193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonanad C., García-Blas S., Tarazona-Santabalbina F., Sanchis J., Bertomeu-González V., Fácila L., et al. The effect of age on mortality in patients with COVID-19: A meta-analysis with 611,583 subjects. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:915–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korc-Grodzicki B., Holmes H.M., Shahrokni A. Geriatric assessment for oncologists. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12:261. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang L.V., Hu Y. Poor clinical outcomes for patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:862–864. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]