Abstract

Objectives:

To determine if patient satisfaction of virtual clinical encounters is non-inferior to traditional in-office clinical encounters for postoperative follow up after reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

Methods:

Randomized controlled non-inferiority trial of women undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Women were recruited and randomized during their preoperative counseling visit to virtual clinical encounters via video conference technology or in-office clinical encounters for their 30-day postoperative follow up visits. The primary outcome was patient satisfaction measured by the validated patient satisfaction questionnaire-18 (score range 18–90 with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction) administered by telephone following the 30-day visit. Additional information regarding demographics, postoperative healthcare utilization and complications was collected via chart review and compared between groups.

Results:

A total of 52 women were randomly assigned to virtual clinical encounters via videoconference technology or traditional in-office clinical encounters (26 per group). The mean patient satisfaction score was 80.7 ± 2.6 in the virtual group and 81.2 ± 2.8 in the office group (difference, −0.46 points; 95% confidence interval, −1.95 to 1.03), which was consistent with non-inferiority. Postoperative complication rates were 31% in the virtual group and 46% in the office group (p = 0.3). There were no significant between-group differences in secondary measures of unscheduled telephone calls (88% vs 77%, p = 0.5) and office visits (35% vs 38%, p = 0.8), emergency room visits (15% vs 19%, p = 1.0) and hospital readmissions (4% vs 12%, p = 0.6) within 90 days of surgery.

Conclusions:

For patients with pelvic organ prolapse undergoing reconstructive surgery, postoperative virtual clinical encounters via video conference technology are non-inferior to traditional in-office clinical encounters with high levels of short-term patient satisfaction and no differences in postoperative healthcare utilization and complications rates.

Introduction

Telehealth refers to the utilization of telecommunication technologies such as telephone, video-conferencing, text messaging and electronic mail to disseminate health related information, services and clinical care to patients.1 National surveys show that patients increasingly expect telehealth options when accessing care and communicating with their healthcare providers.2,3 In a prior study, we have shown that women presenting at female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery clinics are very interested in alternative modes of access to care.4

Prior studies from the general surgery literature suggest that telehealth increases efficiency and access to care and improves patient engagement and adherence to care.5–10 The use of postoperative telephone visits after gynecologic surgery has been studied,11 however there remains a paucity of information on the use of video conference technology. Video conferencing is interactive and allows health care providers to have face to face contact with the patient in real-time, inspect the surgical wound, drains and catheters, and review the medications that patients are taking.

In the postoperative period, patient satisfaction is increasingly emerging as an indicator of overall surgical quality of care.12 Patient satisfaction is a multi-dimensional concept of a patient’s perception of the efficiency, quality and value of the healthcare that they have received.13 Factors shown to contribute to patient satisfaction include healthcare provider communication, timeliness of service, continuity, accessibility and convenience of care.12 By providing an opportunity to impact each of these factors, telehealth programs utilizing video conferencing are capable of improving the quality of postoperative care and the overall surgical experience.

Our primary objective was to determine if a telehealth program utilizing video conference technology is a reasonable option for initial postoperative care at 30 days following surgery for pelvic organ prolapse based on patient satisfaction. We hypothesized that patient satisfaction with virtual clinical encounters would be non-inferior to in-office clinical encounters for postoperative follow up after reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective randomized clinical trial of women undergoing reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Women undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse were recruited from four urban and suburban female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery (FPMRS) clinics of a tertiary academic health system between August 2018 and May 2019. Inclusion criteria were age greater than 18 years, the patient having technological capability to participate in videoconferencing (access to highspeed internet with desktop computer or mobile device), and surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in at least two compartments. Women who could not read or write English were excluded from the study. Women who were undergoing an isolated anti-incontinence surgery (midurethral sling) or vaginal prolapse repair using a mesh kit were also excluded. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent.

Patients were screened for participation in the study at the preoperative appointment. Women scheduled to undergo surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in at least two compartments were asked to complete a four-question technology screening form to assess technologic capability and willingness to participate in virtual clinical encounters via the HIPPA compliant medical video conferencing application Vidyo. Following informed consent, eligible patients were randomized using a blocked randomization schedule to virtual clinical encounters via video-conference technology (virtual group) or traditional in-office clinical encounters (office group).

Intervention:

The virtual group received a video conference call from the office nurse 48 to 72 hours after discharge. This was followed by a video conference call from a physician (FPMRS fellow and/or surgeon) approximately 30 days following surgery. The office group received a telephone call from the office nurse 48 to 72 hours after discharge. They then returned to clinic for an in-office visit with the physician (FPMRS fellow and/or surgeon) approximately 30 days following their surgery. Both groups returned to clinic for an in-office visit with the physician (FPMRS fellow and/or surgeon) 90 days following surgery. Both office and virtual encounters were conducted using a standard script which reviewed the following key aspects of postoperative care: bowel function, urinary function, presence of vaginal bleeding, pain, dietary status, ambulatory status and any additional concerns. Postoperative instructions and precautions were also reviewed.

Outcomes:

The primary outcome was patient satisfaction as measured by Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire – 18 (PSQ-18). This was administered by telephone 24 hours after the 30-day postoperative visit by a study coordinator. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire is a validated 18-item questionnaire developed to evaluate satisfaction with medical care in a variety of settings (Appendix 1).14–16 Responses to each item are on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) and assess patient satisfaction in seven different domains: General Satisfaction, Technical Quality of Care, Interpersonal Manner, Communication, Financial Aspect, Time Spent with Doctor, and Accessibility and Convenience. Each domain is averaged for the number of items such that the range of scores for each domain is 1 (dissatisfaction) to 5 (satisfaction). The total score for the questionnaire ranges from 18 (dissatisfaction with medical care) to 90 (highest satisfaction with medical care).

Secondary outcomes included postoperative utilization of healthcare services including telephone calls made to the surgeon’s office, unscheduled office visits, emergency room visits, and hospital readmissions.

We also measured patient experience using a patient experience questionnaire. Patient experience relates to overall interactions during a healthcare encounter and aims to determine if care was received in a respectful and responsive manner. This questionnaire was modified from existing questionnaires used in similar telehealth studies and focuses on specific aspects of the interactions with the healthcare provider and the overall assessment of the efficiency and quality of the postoperative visit.17–21 Items included perceptions of trust, confidentiality, time spent with provider, timeliness and efficiency of visit and if their specific needs were met during the visit. Responses to each item are on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). For data analysis, responses for each item on the questionnaire were dichotomized as favorable or unfavorable responses. An answer of strongly agree or agree (1 or 2) was categorized as favorable and an answer of uncertain, disagree or strongly disagree (3, 4 or 5) was categorized as unfavorable.

Demographic and medical information were obtained from the patients’ medical record including age, race, level of education, Charlson comorbidity index, and pelvic organ prolapse quantification stage (POP-Q).22,23 Data regarding the surgical procedures, American Society of Anesthesiologist physical status classification (ASA class), intraoperative and postoperative surgical complications, operative time, estimated blood loss and length of hospital stay were also collected from the medical record. Patients self-reported estimates of travel distance to the clinic.

Medical records were also audited for postoperative utilization of healthcare services within 30 days and 90 days after their surgery. This included telephone calls made to the surgeon’s office, unscheduled office visits with their surgeon and primary care provider, emergency room visits and hospital readmissions. Communication and office visits with other healthcare providers in the postoperative period were also tracked. Visit length time for virtual clinical encounters were calculated from the time the patient connected to the video conferencing platform to when they disconnected. Visit length time for traditional clinical encounters was calculated from the time the patient checked into their appointment with the reception desk to the time they checked out at the end of their visit.

All analyses were conducted using an intent-to-treat principle. Data between groups were analyzed using two-sample t-tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, Pearson chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. All reported p-values were two-sided and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 13.1 Software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

The minimum important difference (MID) has not been previously reported for the PSQ-18 but prior studies utilizing this questionnaire have shown that the standard deviation for total PSQ-18 scores range between 5 and 8 with a mean total score range between 67 and 72.24 With a non-inferiority margin of 5 points on the PSQ-18, a type I error rate of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, we estimated a sample size of 25 women per group.

Results

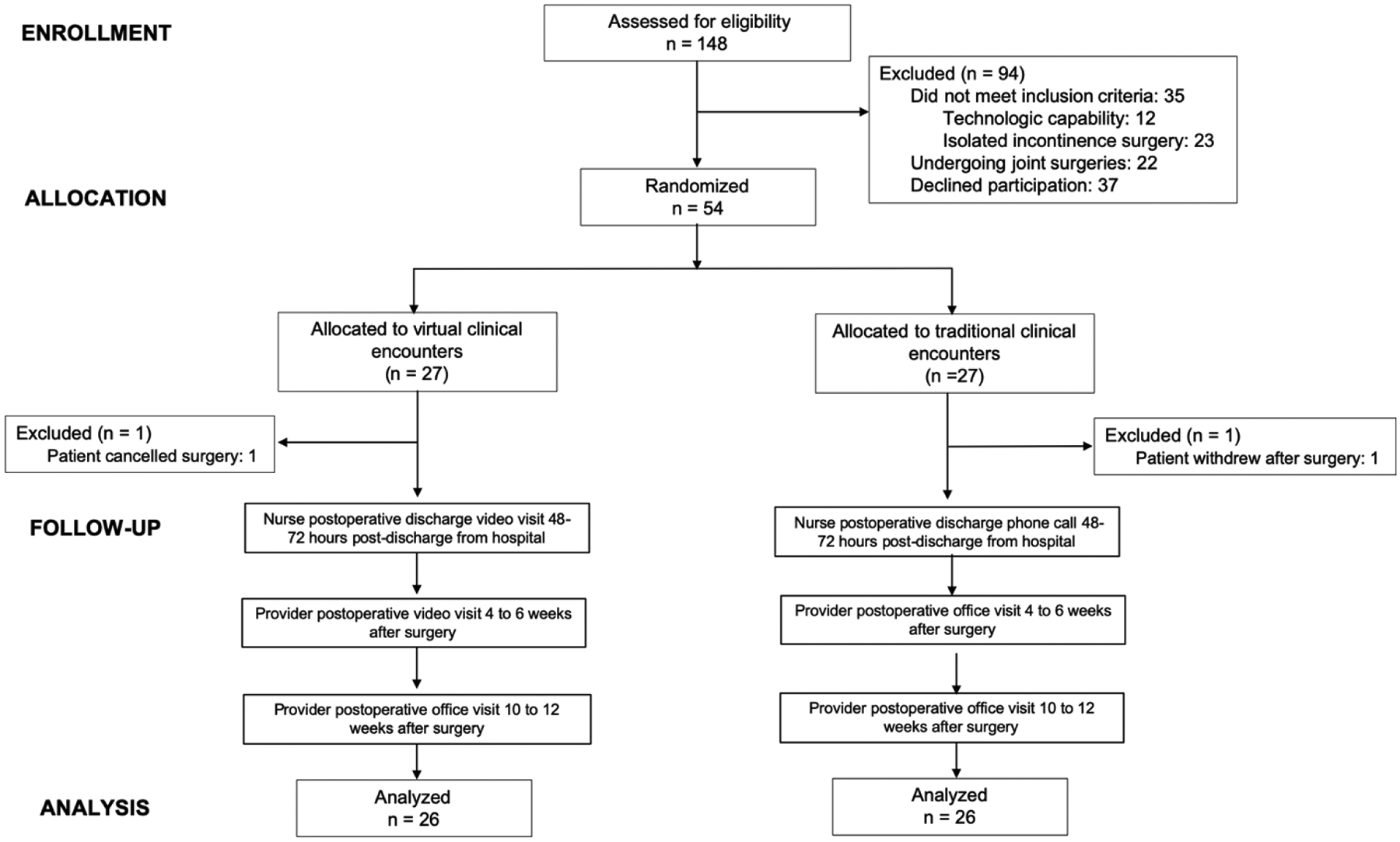

A total of 148 women were screened for eligibility, 54 were randomized, and 52 women completed all aspects of the 30 day and 90 day follow up visits (Figure 1). Of the 148 women screened, 12 (8%) were excluded because they did not have the technological capability to participate in videoconferencing. Our missing data rate was <1% for 1 subject who declined to answer one question on the patient experience questionnaire. All women completed the 30-day postoperative visit as per their original allocation (video or office). The median age of respondents was 62 years old (range 35 to 76 years old). Majority of the subjects were Caucasian (85%). The median number of miles traveled for clinic visits was 14.5 miles (range 1 to 121 miles).

Figure 1.

Randomization and enrollment flow diagram

Demographic and surgical data comparing the virtual and office groups are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, race, POP-Q stage, Charlson comorbidity index, or preoperative, operative and postoperative factors between groups. Majority of women in both groups had stage 3 or higher pelvic organ prolapse (73%) and received a concomitant synthetic mesh midurethral sling. Majority of women in both groups had a hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair (63%); no women in the office group underwent a transvaginal hysterectomy.

TABLE 1.

Demographics

| Characteristic | Virtual Clinical Encounter (N =26) |

Office Clinical Encounter (N = 26) |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 59.9 ± 10.9 | 58.0 ± 11.3 | 0.5† |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 24.7 ± 0.7 | 25.4 ± 4.5 | 0.5† |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 21 (80) | 23 (88) | 0.6 |

| Black | 3 (12) | 3 (12) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | |

| Distance to Clinic, miles (median, range) | 12.5 (1–43) | 21 (2–121) | 0.2‡ |

| POP-Q Stage, n (%) | |||

| 2 | 6 (23) | 8 (31) | 0.8 |

| 3 | 18 (68) | 17 (65) | |

| 4 | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | |||

| 0 – 2 | 18 (69) | 14 (54) | |

| 3 – 4 | 6 (23) | 11 (42) | 0.4 |

| > 4 | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | |

| ASA Class, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 4 (15) | 1 (4) | 0.3 |

| 2 | 21 (81) | 22 (84) | |

| 3 | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | |

| Route of Surgery, n (%) | |||

| Laparotomy | 8 (31) | 7 (27) | 0.8 |

| Minimally Invasive | 8 (31) | 10 (38) | |

| Vaginal | 10 (38) | 9 (35) | |

| Type of Prolapse Surgery | |||

| Sacrocolpopexy | 16 (62) | 16 (62) | |

| Uterosacral ligament suspension | 4 (15) | 3 (12) | 0.9 |

| Sacrospinous ligament suspension | 3 (12) | 3 (12) | |

| Anterior and Posterior colporrhaphies | 2 (8) | 4 (15) | |

| Obliterative procedure | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Intra-abdominal Mesh for Prolapse Repair, n (%) | 16 (62) | 16 (62) | 1.0 |

| Concomitant Midurethral Sling, n (%) | 17 (65) | 17 (65) | 1.0 |

| Type of Hysterectomy, n (%) | |||

| Abdominal (open and minimally invasive) | 15 (58) | 14 (54) | 0.1 |

| Transvaginal | 4 (15) | 0 (0) | |

| None | 7 (27) | 12 (46) | |

| Operative Time, minutes, mean ± SD | 205 ± 66 | 204 ± 87 | 1.0† |

| Estimated Blood Loss, milliliters (median, range) | 150 (50–350) | 150 (10–400) | 0.1‡ |

| Postoperative Length of Stay, days (median, range) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.3‡ |

| Discharged Home with Catheter, n (%) | 8 (31) | 8 (31) | 1.0 |

| Use of Homecare Services, n (%) | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | 1.0 |

BMI, body mass index; POP-Q, pelvic organ prolapse quantification system; SD, standard deviation

Fisher’s exact test or chi squared test unless otherwise specified

Two sample t-test

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

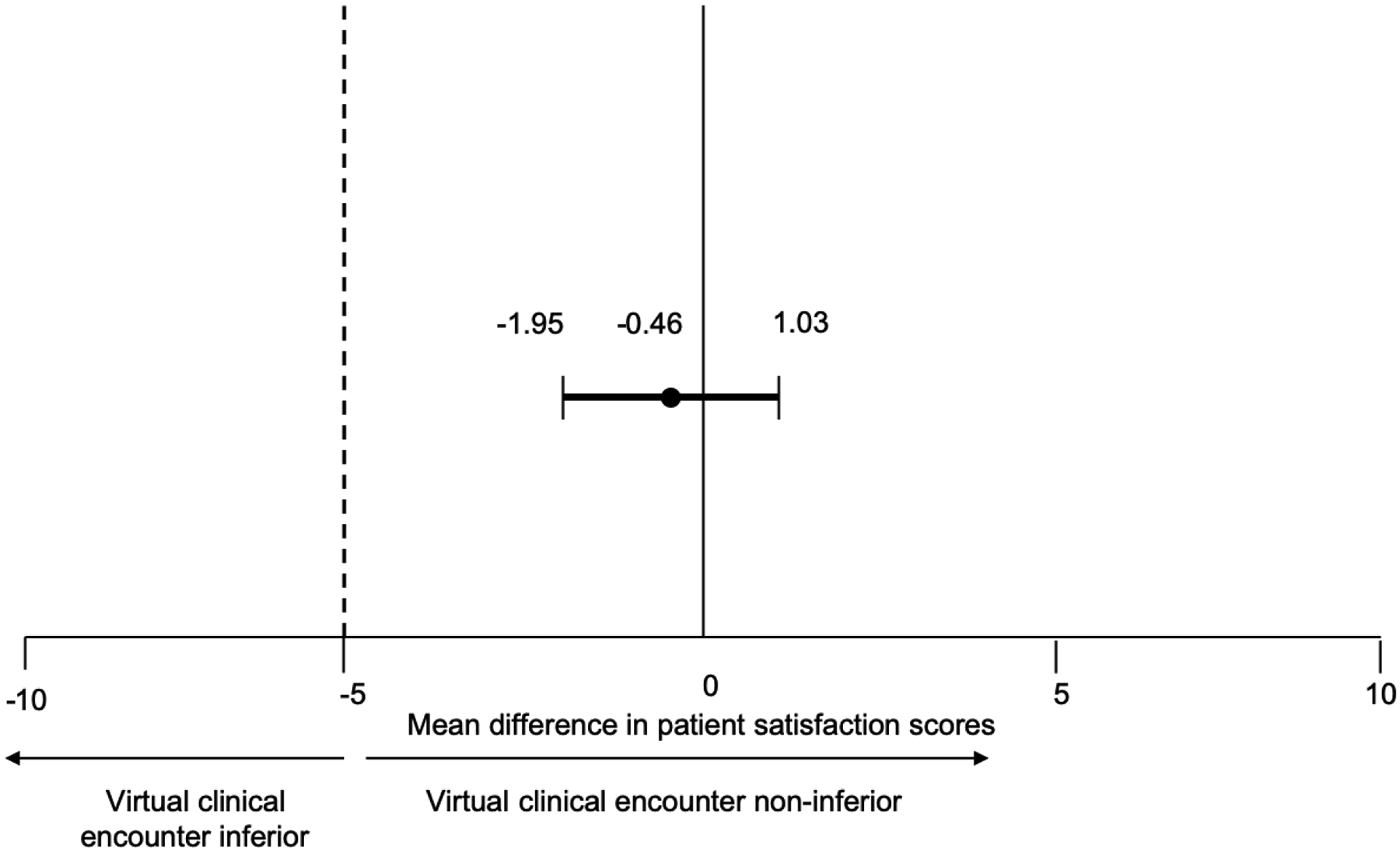

Patient satisfaction outcomes were similar in the virtual and office groups, total PSQ-18 scores were 80.7 ± 2.6 and 81.2 ± 2.8, respectively. The between-group mean difference of 0.46 (95% CI −1.95 to 1.03) in total patient satisfaction score as measured by the PSQ-18 met our criterion for non-inferiority of virtual clinical encounters (Figure 2). Women in the office encounter reported significantly greater satisfaction on the financial domain of the PSQ-18, no differences were observed in the remaining domains (table 2).

Figure 2.

Non-inferiority analysis

Table 2.

Patient Satisfaction*

| Patient Satisfaction Scores by Domain | Virtual Clinical Encounter | Office Clinical Encounter | p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Satisfaction Score | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Technical Quality Score | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Interpersonal Manner Score | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Communication Score | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 0.05 |

| Financial Aspects Score | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 0.03 |

| Time Spent with Provider Score | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Accessibility and Convenience Score | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 0.6 |

Mean ± standard deviation

As measured by Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire-18

Wilcoxon rank sum test

Patient experience in terms of perceived relationship and interactions with the healthcare provider was similar between the virtual and office groups (table 4). However, more women in the virtual group reported that their visit was on time and efficient (p < 0.001) while more women in the office group felt as if their visit took longer than expected (p < 0.001). Duration of the visit was significantly shorter for the virtual group than the office group (24 ± 5.8 versus 71 ± 22 minutes, p < 0.001). Significantly more patients in the virtual group reported that they were pleased with the quality of the visit. Both groups agreed that telehealth could help reduce stress, save time, and save money with no significant differences in these measures between groups.

TABLE 4.

Patient Experience of the Post-operative visit

| Virtual Clinical Encounter (n =26) N (%) |

Office Clinical Encounter (n =26) N (%) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit Duration, minutes (mean ± SD) | 24 ± 5.8 | 71 ± 22 | <0.001† |

| I could talk freely to the healthcare provider during the visit. | 26 (100) | 26 (100) | 1.0 |

| I have a trusting relationship with my healthcare provider. | 26 (100) | 26 (100) | 1.0 |

| I believe that my visit was conducted in a confidential manner. | 25 (96) | 26 (100) | 0.3 |

| The healthcare provider was knowledgeable, skillful and courteous. | 26 (100) | 26 (100) | 1.0 |

| The healthcare provider answered all of the questions that I had. | 26 (100) | 26 (100) | 1.0 |

| The healthcare provider spent enough time with me during the session. | 26 (100) | 23 (88) | 0.07 |

| I believe that the healthcare provider is able to do their job even if they are not able to conduct a physical examination at every appointment. | 26 (100) | 17 (65) | 0.001 |

| I knew who to contact if I had any questions in-between my visits. | 26 (100) | 26 (100) | 1.0 |

| My needs were met during my visit. | 26 (100) | 26 (100) | 1.0 |

| My visit was on time and efficient. | 26 (100) | 12 (50) | <0.001 |

| My visit made it easier to receive my healthcare today. | 26 (100) | 21 (81) | 0.02 |

| My visit took longer than expected. | 0 (0) | 14 (54) | <0.001 |

| I was pleased with the quality of my visit. | 26 (100) | 18 (69) | 0.002 |

| Telehealth could reduce stress on patients by preventing travel | 25 (96) | 26 (100) | 0.3 |

| Telehealth could save me time. | 26 (100) | 26 (100) | 1.0 |

| Telehealth could save me money. | 25 (96) | 26 (100) | 0.3 |

chi-squared test, unless otherwise specified

two sample t-test

Postoperative utilization of healthcare services within 30 and 90 days after surgery were similar in both groups (table 3). During the 30-day video visit evaluation, no urgent in-office visits were deemed necessary for women in the virtual group. No differences were seen in the number of women with unscheduled telephone calls, unscheduled office visits, emergency room visits and re-admissions.

TABLE 3.

Postoperative Outcomes

| Postoperative Characteristics* | Virtual Clinical Encounter (N = 26) |

Office Clinical Encounter (N = 26) |

p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unscheduled Telephone Calls, n (%) | |||

| 30-day | 22 (85) | 17 (65) | 0.2 |

| 90-day | 23 (88) | 20 (77) | 0.5 |

| Unscheduled Office Visits, n (%) | |||

| 30-day | 9 (35) | 9 (35) | 1.0 |

| 90-day | 9 (35) | 10 (38) | 0.8 |

| Emergency Room Visits, n (%) | |||

| 30-day | 2 (8) | 5 (19) | 0.4 |

| 90-day | 4 (15) | 5 (19) | 1.0 |

| Hospital Readmissions, n (%) | |||

| 30-day | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | 0.6 |

| 90-day | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | 0.6 |

| Postoperative Complications, n (%) | 8 (31) | 12 (46) | 0.3 |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 0.3 |

| Wound Infection | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0.5 |

| Other Infection | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 0.6 |

| Vaginal Bleeding | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Pain | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 1.0 |

| Constipation | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 1.0 |

| Urinary Retention | 3 (12) | 4 (16) | 1.0 |

| Nerve Injury | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1.0 |

| Postoperative Interventions, n (%) | |||

| Antibiotics | 4 (15) | 4 (15) | 1.0 |

| Vaginal Estrogen | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 1.0 |

| Intermittent self-catheterization | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | 0.6 |

| Re-operation | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 1.0 |

Number of patients with postoperative characteristics

Fisher’s exact test or chi squared test

Rates of postoperative complications were also similar between the virtual and office groups. The most common intervention in both groups was administration of antibiotics (15% vs 15%, p = 1.0). Urinary retention rates were similar between both groups with 1 patient in the virtual group and 3 patients in the office group requiring intermittent self-catheterization. Three patients, 1 (4%) vs 2 (8%), p=1.0, in the virtual and office group, respectively, needed additional surgery within 90 days of surgery: one for closure of incisional hernia, one for midurethral sling release and one for excision of midurethral sling mesh exposure. One patient in the office group experienced a temporary femoral nerve palsy that resolved by the time of her 12-week postoperative visit.

Discussion

Patient satisfaction is a critical component for adoption of new methods of health care delivery such as telehealth. Our randomized trial shows that patient satisfaction with telehealth using videoconferencing technology was non-inferior to traditional in-office postoperative clinical encounters. Another potential barrier to adoption of telehealth for postoperative patients is that it may increase the complication rate or unplanned office visits. In our study, the rate of postoperative utilization of healthcare services and postoperative complications rates was similar between the two groups. Taken together, these findings suggest that telehealth using video conferencing technology may be a reasonable alternative to traditional in office postoperative visits for patients undergoing surgery for pelvic floor disorders.

Wait time in the office is a leading source of patient dissatisfaction with health care services. Visit length for a traditional in-office visit includes time spent in the waiting room and exam room and direct time spent with their healthcare provider. Additionally, patients have to travel to the office to visit the provider and incur costs of travel such as parking. Studies have shown that patient perception of the time they spend with their healthcare provider is a large determinant of overall patient satisfaction in an ambulatory care setting.25,26 In our study, both the perceived and actual time burden for postoperative visits was lower in the virtual clinical encounter group than the traditional in-office visit group. The average visit length, excluding travel time, for women in the virtual encounter group was almost one third that of the traditional in-office visit group with the majority of the visit consisting of direct contact with the healthcare provider. Over half the women in the office group felt that their visits took longer than expected while more women in the virtual group perceived their visits to be on time and efficient. These findings suggest that innovations such as virtual clinical encounters have the ability to maintain the confidential patient-healthcare provider relationship while maintaining high patient satisfaction.

A major limitation of a virtual encounter is that it does not allow pelvic examinations. Our study excluded women who were at high-risk for vaginal complications such as those receiving transvaginal mesh, due to the risk and possible need for early intervention of mesh exposure following surgery. During the virtual encounter, we inspected abdominal wounds but did not inspect the perineum. Recent research indicates that the most common reasons for gynecological patients to contact their healthcare providers in the post-operative period are for pain and wound issues.27 In our study, a majority of women in both groups had at least one patient-initiated telephone call within 30 days of surgery. Despite the fact that a pelvic exam was not performed in the virtual group, the rate of postoperative telephone calls, office visits, emergency room visits and re-admissions within 30 and 90 days after surgery was similar between groups. Additionally, no urgent in-office exams were deemed necessary for women in the virtual group during their 30-day video visit evaluation. Our study was not powered to detect these secondary outcomes, and so our failure to find a difference in health care utilization between groups may be a result of small sample size. However, it is possible that since videoconferencing allows direct face to face contact with the provider, video-based telehealth could provide satisfactory patient care to women at low-risk for vaginal complications in the immediate post-operative period.

Our study has several limitations. There was a potential for sampling bias as only subjects who already had the technological capability and knowledge of conducting video conference visits were included. However, it should be noted that telehealth should be viewed as an alternative strategy for communication for those that are interested rather than a mandatory method of communication. Although in a prior study we showed that ownership of mobile technology and Internet access is high even in older women with pelvic floor disorders, our current findings cannot be generalized to patients who do not use such technology or to high-risk patients. Additionally, postoperative utilization of healthcare services outside of our healthcare system was not tracked, but less than 8% of study participants had primary care providers outside the health system. Strengths of our study include the utilization of a validated questionnaire and demonstration of the feasibility of conducting a randomized controlled trial of different modes of healthcare delivery for postoperative care. This is also the first published study to investigate the use of video conference technology to conduct virtual clinical encounters for postoperative follow up in gynecology.

In conclusion, our study shows that following surgery for pelvic organ prolapse, postoperative virtual clinical encounters through video conference technology are non-inferior to traditional in-office clinical encounters in terms of patient satisfaction with no differences in healthcare utilization or postoperative complications. Virtual clinical encounters are also associated with less time burden and higher perceptions of efficiency for healthcare visits. These insights will help healthcare providers develop and expand innovative telehealth programs that allow for more efficient and convenient delivery of postoperative care.

Supplementary Material

Financial support for this project:

Dr. Andy is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Aging (R03-AG-053277, PI: Andy). For the remaining authors none were declared.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: none

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT04138810.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ho K, Cordeiro J, Hoggan B, et al. Telemedicine: Opportunities and developments in member states. World Health Organization;2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Truex G As telehealth technology and methodologies mature, consumer adoption emerges as key challenege for providers. J.D. Power;2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telehealth Index: 2017. American Well;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee DD, Arya LA, Andy UU, Sammel MD, Harvie HS. Willingness of Women With Pelvic Floor Disorders to Use Mobile Technology to Communicate With Their Health Care Providers. Female pelvic medicine & reconstructive surgery. 2019;25(2):134–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenberg DH K; Wren SM Telephone follow-up by a midlevel provider after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair instead of face-to-face clinic visit. JSLS. 2015;19(1):e2014 00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emerson CG L; Harper S; Woodruff C Effect of telephone followups on post vasectomy office visits. Urol Nurs. 2000;20(2):125–127, 131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer KH V; Jager A; von Allmen D Efficacy and utility of phone call follow-up after pediatric general surgery versus traditional clinic follow-up. Perm. 2015;19(1):11–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greer JA, Xu R, Propert KJ, Arya LA. Urinary incontinence and disability in community-dwelling women: a cross-sectional study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2015;34(6):539–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafiji JS P; Hussain W Patient satisfaction with post-operative telephone calls after Mohs micrographic surgery: a New Zealand and U.K. experience. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(3):570–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwa KW SM Telehealth follow-up in lieu of postoperative clinic visit for ambulatory surgery: results of a pilot program. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(9):823–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson JC, Cichowski SB, Rogers RG, et al. Outpatient visits versus telephone interviews for postoperative care: a randomized controlled trial. International urogynecology journal. 2019;30(10):1639–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow A, Mayer EK, Darzi AW, Athanasiou T. Patient-reported outcome measures: The importance of patient satisfaction in surgery. Surgery. 2009;146(3):435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall GN, Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The structure of patient satisfaction with outpatient medical care. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(4):477–483. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall GN HR. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18). Santa Monica, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thayaparan AJ, Mahdi E. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) as an adaptable, reliable, and validated tool for use in various settings. Medical education online. 2013;18:21747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE, Snyder MK, Wright WR, Davies AR. Defining and measuring patient satisfaction with medical care. Eval Progam Plann. 1983;63(3–4):247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sathiyakumar V, Apfeld JC, Obremskey WT, Thakore RV, Sethi MK. Prospective randomized controlled trial using telemedicine for follow-ups in an orthopedic trauma population: a pilot study. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2015;29(3):e139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viers BR, Lightner DJ, Rivera ME, et al. Efficiency, satisfaction, and costs for remote video visits following radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial. European urology. 2015;68(4):729–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan GJ, Craig B, Grant B, Sands A, Doherty N, Casey F. Home videoconferencing for patients with severe congential heart disease following discharge. Congenital heart disease. 2008;3(5):317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz MH, Slack R, Bruno M, et al. Outpatient virtual clinical encounters after complex surgery for cancer: a prospective pilot study of “TeleDischarge”. The Journal of surgical research. 2016;202(1):196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park ES, Boedeker BH, Hemstreet JL, Hemstreet GP. The initiation of a preoperative and postoperative telemedicine urology clinic. Studies in health technology and informatics. 2011;163:425–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1996;175(1):10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emilia A Hermann M MPH, Ashburner Jeffrey M. PHD, MPH, Atlas Steven J. MD, MPH, Chang Yuchiao PHD, and Percac-Lima Sanja MD, PHD, MPH. Satisfaction With Health Care Among Patients Navigated for Preventive Cancer Screening Journal of Patient Experience 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the Patient-Physician Relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;Jan(14 Suppl 1):S34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin CT, Albertson GA, Schilling LM, et al. Patients’ Perception of Time Spent With the Physician a Determinant of Ambulatory Patient Satisfaction? Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(11):1437–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortin CN, Holthaus E, Radeva M, Barber M. Reasons and Risk Factors for Seeking Unscheduled Medical Advice in the Postoperative Period Among Gynecologic Patients. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 2018;34(6). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.