Abstract

Background

Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4) is the canonical anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion partner in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and ALK-positive patients showed promising responses to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). However, studies that comprehensively investigate ALK TKI treatment in patients with different ALK fusion patterns are still lacking.

Methods

Ninety-eight ALK-positive patients with advanced NSCLC were retrospectively studied for their response to crizotinib and subsequent treatments. Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) was conducted to divide patients into different groups based on their ALK fusion patterns. Non-canonical ALK fusions were validated using RNA-sequencing.

Results

54.1% of patients had pure canonical EML4-ALK fusions, 19.4% carried only non-canonical ALK fusions, and 26.5% harbored complex ALK fusions with coexisting canonical and non-canonical ALK fusions. The objective response rate and median progression-free survival to crizotinib treatment tended to be better in the complex ALK fusion group. Notably, patients with complex ALK fusions had significantly improved overall survival after crizotinib treatment (p = 0.012), especially when compared with the pure canonical EML4-ALK fusion group (p = 0.010). The complex ALK fusion group also tended to respond better to next-generation ALK TKIs, which were used as later-line therapies. Most identified non-canonical ALK fusions were likely to be expressed in tumors, and some of them formed canonical EML4-ALK transcripts during mRNA maturation.

Conclusion

Our results suggest NSCLC patients with complex ALK fusions could potentially have better treatment outcomes to ALK TKIs therapy. Also, diagnosis using CGP is of great value to identify novel ALK fusions and predict prognosis.

Keywords: EML4-ALK, non-canonical ALK fusion, complex ALK fusions, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for more than 80% of all diagnosed cases (1, 2). Approximately 2–7% NSCLC patients harbor anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangements (3, 4), leading to aberrant expression and oncogenic activation of ALK. Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4)-ALK is the canonical and most common ALK gene arrangement found in NSCLC, by which multiple EML4 breakpoints fuse in frame with the kinase domain of ALK (5). Indeed, more than 15 different EML4-ALK fusion variants have been reported in NSCLC, with v1, v2, and v3a/b being the most abundant variants (6). Some ALK fusions that were less commonly reported in NSCLC (i.e., non-canonical ALK fusions) include kinesin family member 5B (KIF5B)-ALK, TRK-fused gene (TFG)-ALK, kinesin light chain 1 (KLC1)-ALK, striatin (STRN)-ALK, and TNFAIP3 interacting protein 2 (TNIP2)-ALK (7–10), while some ALK fusions were mainly found in other cancers, for example, nucleophosmin (NPM)-ALK fusion was almost exclusively found in large cell lymphomas (11).

Due to the rapid progress in targeted therapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are becoming the standard of care for oncogene-positive NSCLC. Crizotinib, showed improved objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) in ALK-positive NSCLC patients compared with chemotherapy (12–14). Subsequent generations of ALK TKIs were then developed and showed promising clinical responses (15–17). Nevertheless, about 10–40% of ALK-positive NSCLC patients failed to respond to ALK TKIs, suggesting that further stratifying ALK-positive patients based on their TKI response is of clinical importance. Given that EML4-ALK is the most common ALK fusions in NSCLC, several studies demonstrated that different variants of EML4-ALK fusions have distinct sensitivity to ALK inhibitors (18, 19), although some researchers found there was no significant differences in PFS among patients with these EML4-ALK variants (20). In contrast, there are limited data about the TKI clinical response for canonical (EML4-ALK) versus non-canonical (non-EML4-ALK) fusions in NSCLC. Rosenbaum et al. compared 14 canonical ALK fusions with 3 non-canonical ALK fusions and concluded that patients with canonical ALK fusions had better overall survival (OS) (21). However, this study is limited by small patient numbers and needs to be validated in larger patient cohorts.

Unlike traditional diagnosis methods, such as break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC), which only give the positivity/negativity of ALK fusion, comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is able to separate different ALK fusion variants and identify rare fusion partners that may be associated with different sensitivities to ALK TKIs. In the current study, we used CGP to characterize 98 ALK-positive NSCLC patients and grouped them based on the presence of canonical and/or non-canonical ALK fusions. We aimed to study the crizotinib response in patients with different ALK fusion patterns and sought to correlate the clinical outcomes with different patient/treatment characteristics and genomic profiling results.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Methods

This study was approved by the institutional ethics review board of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital [Ethics number: No. GDREC2019323H (R1)]. All patients signed informed consent forms prior to sample collection and consented for publication of related clinical information and any accompanying image. Ninety-eight ALK-positive patients with advanced NSCLC were retrospectively studied. Hybridization capture-based CGP using next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed with (FFPE) or plasma samples collected at baseline (n = 43) or progressive disease (PD; n = 55) to characterize their ALK fusion patterns. Crizotinib clinical response was evaluated via computed tomography scans six weeks after the first crizotinib administration and every 6/8 weeks thereafter according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. PFS was measured from the date of initiation of crizotinib treatment until disease progression or death. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of initiation of crizotinib treatment to death resulting from any causes or was censored at the last follow-up on November 30, 2019.

DNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and CGP Data Analysis

Tumor genomic DNA was extracted from FFPE samples with a tumor content >50% using a QIAamp DNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to detect somatic mutations. Genomic DNA from white blood cells was extracted using DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Hybridization capture-based CGP using NGS was performed at two genetic testing centers. Briefly, the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa Biosystems, USA) was used for DNA library preparation. Customized xGen lockdown probes (Integrated DNA Technologies, USA) were used for hybridization enrichment. All procedures were conducted according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The overlapping 279 cancer-relevant genes from the two testing centers were included for CGP analysis ( Supplementary Table 1 ). Somatic mutations were first filtered for common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with dbSNP and 1,000 Genome datasets, followed by further filtration of germline mutations with normal blood controls. Structural variants were detected using FACTERA with default parameters (22). The fusion reads were further manually reviewed and confirmed on Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (23). ADTEx (http://adtex.sourceforge.net) was used to identify copy number variations (CNVs) with default parameters.

Break-Apart Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) and Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Unstained FFPE sections from tumor specimens collected at diagnosis were subjected to FISH with ALK break-apart probes (Vysis ALK Break Apart FISH Probe Kit; Abbott Molecular, Abbot Park, IL, USA) and/or IHC staining with Ventana anti-ALK (D5F3) rabbit monoclonal primary antibody (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), following the manufacturers’ instructions.

Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) and Sanger Sequencing

Total RNA from FFPE samples was extracted using RNeasy FFPE kit (QIAGEN). Reverse transcription was performed with Superscript Vilo mastermix (Life Technologies). Gel-purified DNA was sent for Sanger sequencing to identify the sequence in cDNA.

RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq)

Poly(A) fractions from the globin depleted RNA samples (1.0 μg) were purified by oligo-dT purification beads (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, USA) and then used to construct cDNA libraries following the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Guide (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, USA). Sequencing was performed on the HiSeq 2000 System (Illumina, Inc.) using the TruSeq Paired-End (PE) 100 bp Kit (Illumina, Inc.). Real-time analysis and base calling were conducted using the Control software in the instrument. The initial processing of reads from the HiSeq instrument used the Illumina CASAVA (v1.8).

Statistical Analysis

The comparison of mutation frequency between different ALK fusion groups was done using Fisher’s exact test, and genes with p values smaller than 0.1 were included for further analysis. For survival data, Kaplan-Meier curves were analyzed using the log-rank test; for the pairwise log-rank test, the p values were adjusted by Benjamini and Hochberg method; the censored points were marked in the figure when the patient loss to follow-up during the study. The univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using the Cox regression model. For analyzing the next generation TKIs, only patients who had known next generation TKI treatment history were included. Two-sided p values of less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done in R (v.3.6.0).

Results

Patient Clinical Characteristics and ALK Fusion Patterns

From January 2016 to June 2019, a total of 2016 NSCLC patients from our hospital were diagnosed with NSCLC, and 150 of them (7.4%) were detected to be ALK-positive using break-apart FISH and/or IHC. Ninety-eight ALK-positive patients with advanced NSCLC were retrospectively studied for their clinical response to crizotinib after excluding patients with early staging, unacceptable crozotinib toxicitiesor unclear clinical history, as well as patients without crizotinib treatment ( Supplementary Figure 1 ). The ALK fusion patterns were characterized using CGP, with 43 patients being sequenced at diagnosis (baseline) and 55 patients being sequenced at PD after crizotinib treatment ( Supplementary Figure 1 ). Since the time of sampling (i.e., baseline vs. PD) makes little difference on the frequency of various ALK fusion patterns ( Supplementary Figure 2A vs. 2B ), we combined all the CGP analysis and used it to divide all 98 ALK-positive patients into 3 groups ( Supplementary Figure 2B ): 1) 53 patients (54.1%) had only the canonical EML4-ALK fusions; 2) 19 patients (19.4%) carried only the non-canonical ALK fusions; 3) 26 patients (26.5%) who harbored both canonical and non-canonical ALK fusions were classified as the complex ALK fusion group. As shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2 , patient characteristics such as age, gender, smoking history, histology, performance status (PS) scores, and disease stage were similar across different ALK fusion groups, with majorities of the ALK-positive patients in our cohort were never smokers (81.6%) with lung adenocarcinoma (ADC; 96.0%). Also, most patients received crizotinib as the first line (63.3%) or second-line (28.6%) treatment. After disease progression to crizotinib treatment, more than 60% of the patients used next-generation ALK inhibitors and about 40% of patients received palliative treatment ( Table 1 ). The median OS for all 98 patients was 19.7 months.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinicopathologic characteristics of ALK-positive NSCLC patients.

| Pure EML4-ALK fusionsn (%) | Pure uncommonALK fusionsn (%) | ComplexALK fusionsn (%) | All patientsn (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 53 | 19 | 26 | 98 |

| Median age, years (range) | 46 (25–76) | 50 (30–69) | 49 (28–70) | 47.5 (25–76) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 22 (41.5) | 10 (52.6) | 15 (57.7) | 47 (48.0) |

| Female | 31 (58.5) | 9 (47.4) | 11 (42.3) | 51 (52.0) |

| Smoking history | ||||

| Yes | 10 (18.9) | 4 (21.1) | 4 (15.4) | 18 (18.4) |

| No | 43 (81.1) | 15 (78.9) | 22 (84.6) | 80 (81.6) |

| Histology | ||||

| ADC | 51 (96.2) | 18 (94.7) | 25 (96.2) | 94 (96.0) |

| SCC | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (1.0) |

| LCNEC | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) |

| ASC | 1 (1.9) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.0) |

| Disease stage | ||||

| III | 3 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (3.8) | 5 (5.1) |

| IV | 50 (94.3) | 18 (94.7) | 25 (96.2) | 93 (94.9) |

| PS score | ||||

| 0 | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.0) |

| 1 | 46 (86.8) | 17 (89.5) | 23 (88.5) | 86 (87.8) |

| 2 | 5 (9.4) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (11.5) | 10 (10.2) |

| Crizotinib (line of treatment) | ||||

| 1 | 34 (64.2) | 11 (57.9) | 17 (65.4) | 62 (63.3) |

| 2 | 14 (26.4) | 7 (36.8) | 7 (26.9) | 28 (28.6) |

| 3 | 5 (9.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | 7 (7.1) |

| 5 | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Best clinical response for criztinib | ||||

| CR | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) |

| PR | 35 (66.0) | 12 (63.2) | 20 (76.9) | 67 (68.4) |

| SD | 13 (24.5) | 4 (21.1) | 3 (11.5) | 20 (20.4) |

| PD | 5 (9.4) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (11.5) | 10 (10.2) |

| Post-crizotinib ALK inhibitor treatment | ||||

| Yes | 36 (67.9) | 12 (63.2) | 15 (57.7) | 63 (64.3) |

| No | 11 (20.8) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (11.5) | 16 (16.3) |

| NA | 6 (11.3) | 5 (26.3) | 8 (30.8) | 19 (19.4) |

| Palliative treatment for advanced NSCLC* | ||||

| Yes | 21 (39.6) | 12 (63.2) | 8 (30.8) | 41 (41.8) |

| No | 31 (58.5) | 7 (36.8) | 16 (61.5) | 54 (55.1) |

| NA | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | 3 (3.1) |

| Baseline brain metastasis | ||||

| Yes | 10 (18.9) | 5 (26.3) | 8 (30.8) | 23 (23.5) |

| No | 43 (81.1) | 14 (73.7) | 18 (69.2) | 75 (76.5) |

*Palliative treatments include local surgical therapy, palliative radiotherapy, and interventional therapy.

The Association Between ALK Fusion Status and Crizotinib Treatment Outcomes

Firstly, we assessed the drug response in 43 ALK-positive patients with baseline CGP. As shown in Supplementary Table 3 , the ORR for crizotinib was 65.1% and the disease control rate (DCR) was 83.7%. By examining the crizotinib response in each ALK fusion group, we found that DCR was similar among all groups while the complex ALK fusion group had improved ORR compared with other groups ( Supplementary Table 3 ). Similar results were obtained when we used all 98 patients whose ALK fusion pattern was determined by combining baseline and progressive disease CGP ( Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3 ).

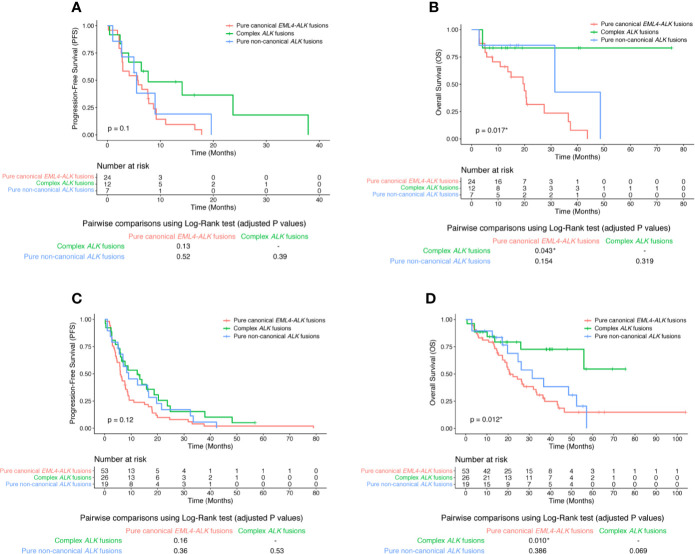

We further examined the post-treatment patient survival in these ALK-positive patients. For the 43 patients with baseline CGP, there was no statistically significant difference in PFS among patients with different ALK fusion patterns (log-rank p value = 0.1; Figure 1A ). Intriguingly, complex ALK fusions were significantly associated with better overall survival (OS) than other ALK fusion patterns (log-rank p value = 0.017), especially when comparing the complex ALK fusion group with the pure canonical EML-ALK fusion group (pairwise log-rank p values were 0.043; Figure 1B ). The results became even more significant if we included all 98 patients. Despite the statistically indistinguishable PFS among 3 ALK fusion groups (log-rank p value = 0.12; Figure 1C ), patients with complex ALK fusions were likely to have better OS than patients with pure canonical EML-ALK fusions (pairwise log-rank p value = 0.01; Figure 1D ). Therefore, our data suggest that harboring complex ALK fusions was a potential positive biomarker for crizotinib treatment in advanced NSCLC patients. Also, because analysis based on baseline CGP (n = 43) and analysis based on the combination of baseline and post-crizotinib CGP (n = 98) gave similar results in terms of the frequency of various ALK fusion patterns and the clinical results, we used the data of all 98 ALK-positive patients for the later on analysis.

Figure 1.

The clinical response of crizotinib in different ALK fusion groups. Kaplan-Meier curve of PFS (A) or OS (B) of crizotinib treatment in 43 patients with baseline CGP in strata of different ALK fusion patterns. Kaplan-Meier curve of PFS (C) or OS (D) of crizotinib treatment in all 98 ALK-positive patients in strata of different ALK fusion patterns. Log-rank test was used to analyze the OS or PFS for all 3 groups (The p value was shown within the Kaplan-Meier curve). Benjamini and Hochberg (BH)-adjusted p values of the log-rank test were reported for all pairwise comparisons (Individual pairwise comparison p values were shown below the Kaplan-Meier curve).

The Correlation Between the Crizotinib Response and the Clinical/Mutational Characteristics

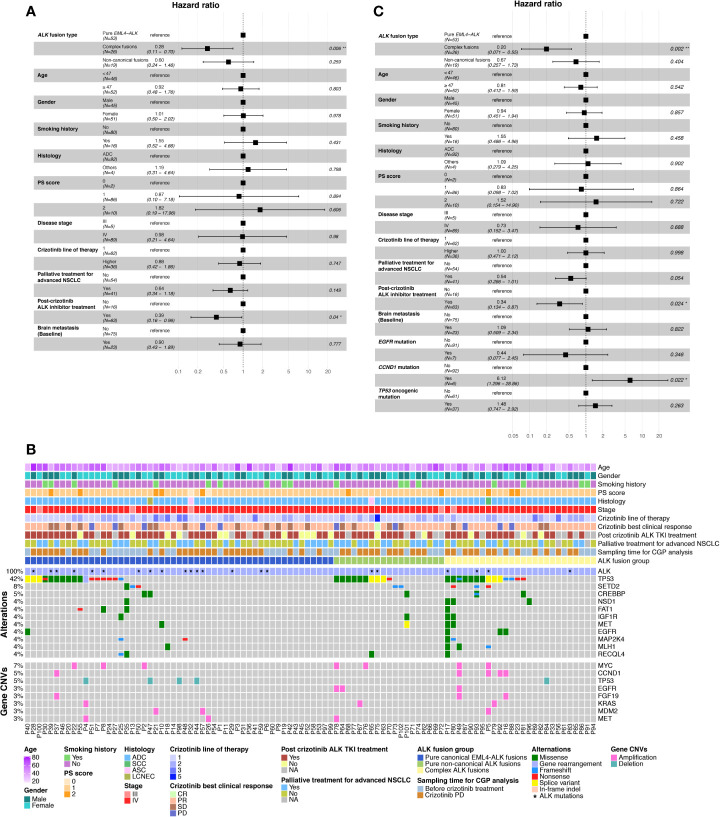

Next, we investigated the correlation between patients’ post-crizotinib OS and other demographic/clinicopathologic characteristics. As illustrated in Supplementary Table 4 , complex ALK fusions and post-crizotinib ALK inhibitor treatment were the only 2 factors that were significantly associated with improved OS (univariate Cox regression analysis, p values were 0.005 and 0.018, respectively). By multivariate analysis, we found complex ALK fusions and post-crizotinib ALK inhibitor treatment still significantly correlated with OS ( Figure 2A ). These results imply that harboring complex ALK fusions or subsequently treating with next-generation ALK TKIs are likely to associate with prolonged post-crizotinib survival in these ALK-positive patients.

Figure 2.

The correlation between the crizotinib response and the clinical/mutational characteristics. (A) Forest plot of multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrating the association between different clinical characteristics and OS in 98 ALK-positive NSCLC patients after crizotinib treatment. (B) Top changed genomic features in 98 NSCLC patients. Patient clinicopathologic characteristics (upper panel), co-mutation plot of genetic alterations (middle panel), and gene-level copy-number variation (lower panel) were illustrated. Genes were ranked based on the number of alterations. CNV, copy-number variation; PS score, performance status score; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease. (C) Forest plot of multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrating the association between clinical/mutational characteristics and OS in 98 ALK-positive NSCLC patients after crizotinib treatment.

We then checked the somatic mutation profile associated with different ALK fusion patterns. Tumor protein p53 (TP53) mutation/deletion and MYC amplification were found to be the most frequent genomic alterations in each ALK fusion group, followed by genomic changes in SET domain containing 2 (SETD2), CREB binding protein (CREBBP), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and cyclin D1 (CCND1) ( Figure 2B ). When comparing mutation frequency between different ALK fusion groups, EGFR mutation/amplification (Fisher’s exact test, p value = 0.038) and CCND1 amplification (Fisher’s exact test, p value = 0.087) were the top 2 genomic alterations enriched in complex ALK fusion groups compared with the pure canonical EML4-ALK fusion group ( Supplementary Table 5 ). To rule out the possibility that the improved OS in the complex ALK fusion group was due to the treatment effects from other targeted drugs (e.g., treating EGFR mutation/amplification-positive patients with EGFR TKIs), we included the mutation/CNV status of EGFR and CCND1 into the multivariate Cox regression analysis. We also included the oncogenic/loss-of-function TP53 mutations given that they have been shown to be associated with unfavorable treatment outcomes in ALK-positive NSCLC. Complex ALK fusions and post-crizotinib ALK inhibitor treatment could still predict post-crizotinib OS after including these genomic alterations (p values were 0.002 and 0.024, respectively); EGFR mutation/amplification was not significantly associated with OS, whereas CCND1 amplification was likely to be a hazard factor for OS ( Figure 2C ).

Lastly, we checked whether some acquired molecular features may explain the differential overall survival between the complex ALK fusion group and the other groups. Among 98 ALK-positive patients in our cohort, 17 of them had both baseline and crizotinib-PD CGP analysis, including 10 patients with pure canonical EML4-ALK fusions, 4 with pure non-canonical ALK fusions, and 3 patients with complex ALK fusions. Interestingly, nearly all the acquired ALK resistant mutations to ALK TKIs were found in the pure canonical EML4-ALK fusion group, implying the potential association between TKI resistant mechanisms and ALK fusion patterns ( Supplementary Figure 3 ).

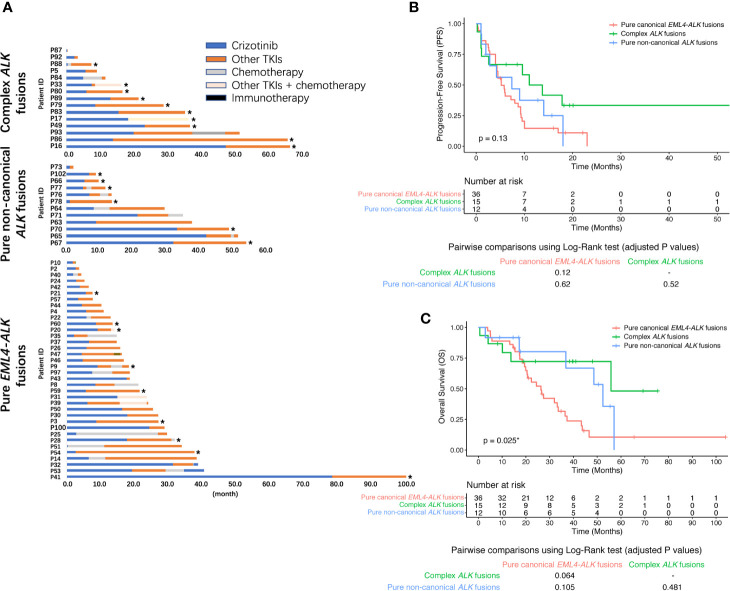

Complex ALK Fusions Also Had a Better Post-Crizotinib OS After the Next-Generation ALK TKIs Treatment

Given both complex ALK fusions and post-crizotinib ALK inhibitor treatment could predict post-crizotinib OS, we then studied whether patients with complex ALK fusions were more likely to respond to next-generation ALK TKIs. Of 98 ALK-positive patients, more than half of them were known to receive second- and/or third-generation ALK TKIs ( Figure 3A ). For patients with pure canonical EML4-ALK fusions, 6 patients switched to alectinib (median PFS = 5.0 months), 5 patients took brigatinib (median PFS = 5.2 months), 9 patients received ceritinib (median PFS = 5.8 months), and 7 patients received foritinib (median PFS = 5.2 months). The remaining 3 pure canonical EML4-ALK fusion patients received ensartinib (PFS = 4.5 months), lorlatinib (PFS = 5.0 months), and foritinib plus chemotherapy (PFS = 8.7 months), respectively. In the pure non-canonical ALK fusion group, 3 patients switched to alectinib (median PFS = 9.0), 2 patients took brigatinib (median PFS = 1.1 months), 1 patient received foritinib (median PFS = 11.6 months), 1 patient received ceritinib (PFS = 14.0 months), and 1 patient was treated with apatinib (PFS = 1.2 months). Among the complex ALK fusions cohort, 2 patients switched to brigatinib (PFS = 52.8 months and 1.0 month, respectively), 2 patients took ceritinib (PFS = 11.0 months and 17.8 months, respectively), 3 patients received aletinib (the duration of 2 patients was less than 1 month, and 1 patient have not progressed until the last follow-up), 5 patients treated with foritinib (clinical trial NCT04237805; median PFS = 13.7 months), and 1 patient received foritinib and concurrent chemotherapy (PFS > 18.2 months). As shown in Figures 3A, B , the complex ALK fusion group tended to have better response to next-generation ALK TKIs than other groups, although the PFS was not statistically significant (log-rank p value = 0.13). Similarly, these patients also seemed to have a better OS (log-rank p value = 0.025; Figure 3C ). These results imply that patients with complex ALK fusions might have a better chance to respond to next-generation ALK TKIs after crizotinib treatment, which might partially contribute to their improved OS.

Figure 3.

Therapeutic response to next-generation ALK TKIs in post-crizotinib patients. (A) Swimmer plot demonstrating the post-crizotinib treatment history in 63 NSCLC patients. The asterisk represents ongoing treatment with the last follow-up on November 30, 2019. Kaplan-Meier curve of PFS (B) or OS (C) in 63 next-generation ALK TKI-treated NSCLC patients in strata of different ALK fusions. When multiple next-generation ALK TKIs were used after crizotinib, the ALK TKI that immediately followed crizotinib treatment was included for the analysis. The OS was calculated from the date of initiation of crizotinib treatment to death resulting from any causes or was censored at the last follow-up. BH-adjusted p values of the log-rank test were reported for pairwise comparisons.

Validation of Non-Canonical ALK Fusions

Lastly, we investigated the non-canonical ALK fusions to check if they could form functional ALK fusion products. By CGP analysis, we identified multiple novel non-canonical ALK fusion partners, including dystrophin (DMD), transmembrane protein 178A (TMEM178A), spectrin repeat containing nuclear envelope protein 1 (SYNE1), zinc finger CCCH-type containing 8 (ZC3H8), acireductone dioxygenase 1 (ADI1), AF4/FMR2 family member 3 (AFF3), protein kinase C epsilon (PRKCE), CUGBP Elav-like family member 4 (CELF4), mal T-cell differentiation protein-like (MALL), SET binding factor 2 (SBF2), proteasome 20S subunit alpha 8 (PSMA8), potassium voltage-gated channel modifier subfamily G member 3 (KCNG3), peroxidasin (PXDN), and ring finger protein 10 (RNF10) ( Table 2 ). Most samples with the pure non-canonical ALK fusions had positive IHC, indicating that most of the identified non-canonical ALK fusions were likely to express the fusion products in the tumor ( Table 2 ).

Table 2.

The list of known or novel non-canonical ALK gene fusions identified in the NSCLC patient cohort.

| ALK Fusion Partner | ALK Fusion Group | Fusion Site | FISH | IHC (Ventana) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Known ALK fusions | GALNT14 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | GALNT14-ALK (exon1:exon19) | + | + |

| HIP1 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | HIP1-ALK (exon19:exon20) | + | + | |

| HIP1 | Complex ALK fusions | HIP1-ALK (exon1:exon16) | NA* | + | |

| HIP1 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | HIP1-ALK (exon19:exon19) | NA | + | |

| KIF5B | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | KIF5B-ALK (exon17:exon20) | + | NA | |

| SETD2 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | SETD2-ALK (exon1:exon20) | NA | + | |

| KLC1 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | KLC1-ALK (exon9:exon20) | + | + | |

| BIRC6 | Complex ALK fusions | BIRC6-ALK (exon43:exon19) | + | + | |

| LOC728730 | Complex ALK fusions | LOC728730-ALK (exon5:exon20) | NA | + | |

| CRIM1 | Complex ALK fusions | CRIM1-ALK (exon2:exon20) | + | + | |

| CLIP4 | Complex ALK fusions | CLIP4-ALK (exon1:exon20) | + | NA | |

| PPP1R21 | Complex ALK fusions | PPP1R21-ALK (exon8:exon20) | + | + | |

| Novel ALK fusions | DMD | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | DMD-ALK (exon55:exon20) | + | + |

| ALK | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | ALK-ALK (intron1:intron19) | + | + | |

| TMEM178A | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | TMEM178A-ALK (exon1:exon20) | NA | + | |

| SYNE1 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | SYNE1-ALK (exon63:exon20) | NA | + | |

| ZC3H8 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | ZC3H8-ALK (exon8:exon20) | + | NA | |

| ADI1 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | ADI1-ALK (exon2:exon20) | + | NA | |

| AFF3 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | AFF3-ALK (exon12:exon20) | NA | + | |

| PRKCE | Complex ALK fusions | PRKCE-ALK (exon10:exon20) | NA | + | |

| CELF4 | Complex ALK fusions | CELF4-ALK (exon2:exon20) | + | NA | |

| MALL | Complex ALK fusions | MALL-ALK (exon1:exon20) | + | + | |

| SBF2 | Complex ALK fusions | SBF2-ALK (exon1:exon18) | + | NA | |

| PSMA8 | Complex ALK fusions | PSMA8-ALK (exon2:exon18) | + | + | |

| KCNG3 | Complex ALK fusions | KCNG3-ALK (exon1:exon20) | + | NA | |

| PXDN | Complex ALK fusions | PXDN-ALK (exon1:exon20) | + | NA | |

| RNF10 | Pure non-canonical ALK fusions | RNF10-ALK (exon1:exon19) | NA | + |

*NA, Results not available due to lack of testing information.

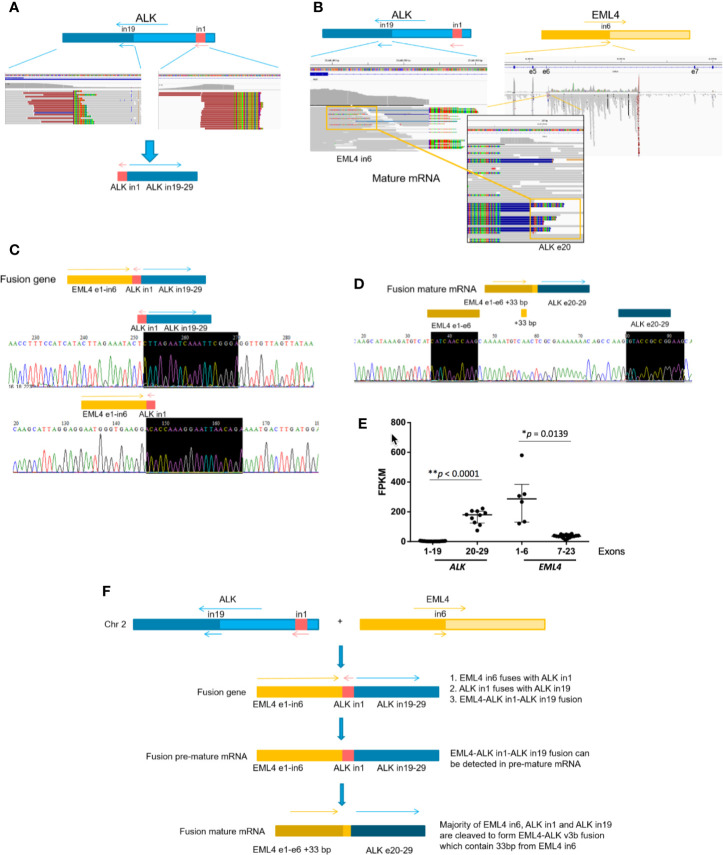

We then selected several novel ALK fusions for further studies. Patient P64 had a rare ALK fusion, linking ALK intron1 with ALK intron19 ( Figure 4A ). We detected mature EML4-ALK (v3b) mRNA using RNA-seq ( Figure 4B ). The CGP and RNA-seq results were further validated using PCR and RT-PCR, respectively ( Figures 4C, D ), and mRNA expression level of EML4 exon1-6 and ALK exon20-29, which corresponds to v3b variant of EML4-ALK fusion, was also significantly higher than other exons of these two genes ( Figure 4E ). To rule out the possibility that ALK intron1-intron19 fusion and EML4-ALK fusion independently existed in the patient sample while CGP failed to detect the latter, we searched through the DNA sequencing and RNA-seq data and found the evidence of fusing EML4 intron6-ALK intron1-ALK-intron19 at both DNA and pre-mature mRNA levels ( Figure 4C and Supplementary Figure 4 ). These results indicate that EML4 intron6-ALK intron1-ALK-intron19 was fused together in patient P64, and ALK intron1 was spliced out during mRNA maturation, resulting in the canonical EML4-ALK fusion ( Figure 4F ). Moreover, Patient P62 carried GALNT14-ALK fusion and SLC19A3 intergenic region (IGR)-ALK fusion simultaneously ( Supplementary Figures 5A, B ). We detected both EML4 intron13-GALNT14 fusion and GALNT14-ALK exon19 fusion in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq ( Supplementary Figures 5C, D ), and we also found EML4 exon13-ALK exon20 (v1) fusion in mature mRNA ( Supplementary Figure 5E ). This implies that the non-canonical GALNT14-ALK fusion was indeed EML4 intron13-GALNT14-ALK exon19 fusion that can be spliced to form EML4-ALK mature mRNA ( Supplementary Figure 5F ), whereas the co-existing SLC19A3 (IGR)-ALK fusion might be non-productive. Similarly, EML4-ALK mature mRNA were observed in patient P73, who harbored SETD2-ALK fusion at the DNA level ( Supplementary Figure 6 ). Taken together, most of the newly identified non-canonical ALK fusions were likely to be expressed in tumors and some of them would generate the canonical EML4-ALK transcripts during mRNA maturation.

Figure 4.

Non-canonical ALK fusions detected by CGP in an NSCLC patient (P64) resulted in a canonical EML4-ALK fusion mRNA. (A) ALK intron1-ALK intron19 fusion was detected at DNA levels by DNA-sequencing (DNA-Seq). (B) Mature EML4-ALK v3b fusion was detected at RNA levels by mRNA-seq. (C) Validation of EML4-ALK intron1 fusion and ALK intron1-ALK intron19 fusion at DNA levels, respectively, by PCR amplification of the fusion region followed by Sanger Sequencing. (D) RT-PCR validation of EML4-ALK v3b fusion at mRNA levels. (E) The relative expression level of ALK and EML4 detected by RNA-seq. FPKM: Fragments per kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads. (F) Model for stepwise EML4-ALK fusion formation during gene transcription.

Discussion

Given the promising therapeutic effects of ALK inhibitors, they are now generally used as the first-line treatment against ALK-positive NSCLC. As a result, identifying patients who will benefit from ALK TKIs is of great importance to improve patients’ survival and quality of life. Compared with the traditional testing methods, such as break-apart FISH or IHC, CGP could more accurately detect ALK fusions (21, 24–28). Besides, CGP can provide additional gene rearrangement information, such as the fusion partner and the breakage point, enabling further analyzing the correlation between the ALK fusion pattern and TKI therapeutic effects. In the present study, we used CGP to characterize 98 ALK-positive NSCLC patients and identified multiple known and novel non-canonical ALK fusions, most of which were likely to form functional products in tumors. In addition, we divided all 98 patients into 3 groups based on their ALK fusion patterns and found patients with complex ALK fusions had improved OS after crizotinib treatment, suggesting the ALK fusion pattern could be used as a prognostic marker for TKI treatment. This conclusion is supported by a recent study who found that NSCLC patients with both reciprocal and non-reciprocal ALK fusions had worse PFS to crizotinib treatment (29).

A few cases of co-existence of canonical and non-canonical ALK fusions has been reported in recent studies (29, 30); however, its clinical relevance was largely unknown. We found that there were little differences in PFS after crizotinib treatment among different ALK fusion groups, whereas patients with complex ALK fusions had better OS. This improved OS was unlikely due to confounding effects of other variables, as tested by multivariate Cox regression analysis. Intriguingly, our data showed that the complex ALK fusion group had trends to respond better to next-generation ALK TKIs after disease progression with crizotinib. Nevertheless, it is still unknown whether the prolonged OS in the complex ALK fusion group would apply to all types of ALK TKIs or whether it is due to sequentially treating patients with crizotinib and second/third-generation ALK TKIs. Recently, several next-generation ALK TKIs are being investigated as the front-line therapy rather than treating crizotinib-resistant patients (15, 16, 31). These studies generally relied on IHC and/or FISH to check ALK fusion status without knowing the specific fusion type. Our results suggest that it might be worth conducting these clinical trials by separating patients based on their ALK fusion patterns in order to figure out the optimal treatment regimen for each patient.

The mechanism of prolonged OS in patients with complex ALK fusions is still unknown. Although some of our preliminary data imply that different ALK fusion patterns may have distinct susceptibility to gain ALK resistant mutations after ALK TKI treatment, this result still needs to be further validated. Also, it is possible that tumors with multiple ALK fusions are likely to be more addicted to the ALK signaling pathway, thus making the ALK TKIs have more profound effects. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that the canonical and non-canonical ALK fusions could be harbored by different subclones of the same tumor and these subclones could have different ALK TKI sensitivity and oncogenic potentials. By eradicating the major and more sensitive subclone using one ALK TKI, the other subclone could then thrive, which makes it a good target for subsequent treatment using another TKI. This hypothesis is supported by prolonged, although not statistically significant, PFS in complex fusion patients who treated with crizotinib and then next-generation TKIs. Therefore, the existence of ALK fusion subclones as well as the drug resistant mechanism should be carefully investigated using paired baseline and PD samples (32) with multi-region sequencing (33) in the future studies.

By analyzing the mutation profile, we found that some somatic genomic alterations, such as EGFR mutation/amplification and CCND1 amplification, tended to be enriched in the complex ALK fusion group. However, these enriched mutations/CNVs were not likely to be the underlying mechanism of improved OS observed in these patients. Instead, CCND1 amplification seems to have negative effects on post-crizotinib patient survival. Consistent with this observation, mutation/amplification of genes involved in cell-cycle control, including CCND1, have also been suggested to hinder the therapeutic effects of EGFR TKIs in NSCLC (34). Nevertheless, because our CGP was based on panel sequencing, whether some rare co-occurred mutations could contribute to the improved crizotinib responses still needs to be tested using whole-exome sequencing or whole genome sequencing.

There were also some limitations associated with our study: 1) The ALK fusion patterns were determined using 43 baseline samples and 55 post-crizotinib samples. Although the ALK fusion patterns were less likely to be altered by crizotinib treatment and clinical results were consistent between 43 baseline patients and all 98 patients, characterizing ALK fusion patterns using only baseline samples should be more accurate. 2) As this study was initiated many years ago, we used crizotinib as the major ALK TKI treatment in our cohort; however, crizotinib was no longer used as the front-line therapy in ALK-positive patients in many countries given the promising therapeutic response of next-generation TKIs. Within the 150 ALK-positive NSCLC patients dragonized in our hospital, 30 of them used second generation ALK inhibitors as the first TKI treatment ( Supplementary Figure 1 ); however, the number of patients was limited and most of their clinical data have not matured. Therefore, we are unable to assess whether harboring complex ALK fusions is also a positive biomarker for front-line second-generation ALK TKIs. 3) Due to the limited availability of patient samples and the instability of RNA within the samples, we only performed RNA-seq validation for a few rare ALK fusions. Although the IHC positivity implies their expression in cancer cells, future studies were needed to confirm whether these rare ALK fusions could form functional products in the tumor. 4) The median OS in our patient cohort was significantly shorter than that in the previous studies (35). Possible reasons for this discrepancy may be due to the differences in patient ethnicity and disease stages among different studies, and our results need to be further confirmed using larger patient cohorts.

Conclusion

Overall, we identified multiple novel non-canonical ALK fusions in advanced NSCLC patients, and we showed that some of the non-canonical ALK fusions could form canonical EML4-ALK transcripts during mRNA splicing. We are also the first group to comprehensively investigate the therapeutic effects of crizotinib in NSCLC patients with different ALK fusion patterns and demonstrated that the complex ALK fusions were associated with improved post-ALK TKI patient survival. Therefore, our results suggest that the determination of ALK fusion pattern using CGP has great clinical potentials to identify novel ALK fusions and make better prediction about patient prognosis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NODE (http://www.biosino.org/node), accessions OEP001261 and OEP001269.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics review board of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Conception and design were done by J-JY, JK, and Y-LW. J-JY, JK, H-JC, and X-CZ provided the study materials or patients. W-ZZ, JS, QZ, H-YT, ZW, C-RX, X-NY, and Z-HC collected and assembled the data. Data analysis was done by JK, YX, XW, XZ, and YS. The manuscript was written by JK and J-JY. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the High-level Hospital Construction Project (Grant No. DFJH201809, J-JY), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81972164, J-JY), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2019A1515010931, J-JY), National Key Technology R&D Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China: Prevention and Control of Major Non-communicable Diseases (Grant No. 2016YFC1303304, J-JY), Key Lab System Project of Guangdong Science and Technology Department-Guangdong Provincial Key Lab of Translational Medicine in Lung Cancer (Grant No. 2017B030314120, Y-LW), and Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDA12020103 to X-CZ and JA, and grant No. XDA12020105 to X-CZ and A-JS).

Conflict of Interest

XZ and YS are the employees of Nanjing Geneseeq Technology Inc.; YX and XW are the employees of Geneseeq Technology Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We owe thanks to the patients in our study and their family members. We acknowledge the staffs for their assistance in our study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.596937/full#supplementary-material

An overview of the study design. The flowchart for including advanced NSCLC patients for the retrospective study.

The pie diagram illustrating the percentage of patients in each ALK fusion group for 43 patients with baseline CGP (A) or for all 98 ALK-positive patients with either baseline or progressive disease CGP (B).

Paired baseline (before crizotinib treatment) and PD (disease progression after crizotinib treatment) mutations/CNVs of NSCLC patients with different ALK fusion patterns. N = 17. BL, baseline.

Pre-mature mRNA detected by RNA-seq revealed complex ALK fusions. (A) ALK intron1-ALK intron19 fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq; (B) EML4 intron6-ALK intron1 fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq.

GALNT14-ALK and SLC19A3 (IGR)-ALK fusions detected by CGP in one NSCLC patient (P62) resulted in a classic EML4-ALK fusion mRNA only. (A) GALNT14-ALK fusion was detected at the DNA level by DNA-seq. (B) SLC19A3 (IGR)-ALK fusion was detected at the DNA level by DNA-seq. (C) EML4-GALNT14 fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq. (D) GALNT14-ALK fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq. (E) Mature EML4-ALK v1 fusion was detected at the RNA level by mRNA-Seq. (F) Model for stepwise EML4-ALK fusion formation during gene transcription.

SETD2-ALK fusion detected by CGP in an NSCLC patient (P73) resulted in a classic EML4-ALK fusion mRNA. (A) EML4-SETD2 fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq. (B) SETD2-ALK fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq. (C) Mature EML4-ALK v5a fusion was detected at RNA levels by mRNA-seq. (D) Model for stepwise EML4-ALK fusion formation during gene transcription.

References

- 1. Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc (2008) 83(5):584–94. 10.4065/83.5.584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Groot PM, Wu CC, Carter BW, Munden RF. The epidemiology of lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res (2018) 7(3):220–33. 10.21037/tlcr.2018.05.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature (2007) 448(7153):561–6. 10.1038/nature05945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Solomon B, Varella-Garcia M, Camidge DR. ALK gene rearrangements: a new therapeutic target in a molecularly defined subset of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol (2009) 4(12):1450–4. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c4dedb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hallberg B, Palmer RH. Mechanistic insight into ALK receptor tyrosine kinase in human cancer biology. Nat Rev Cancer (2013) 13(10):685–700. 10.1038/nrc3580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He Y, Sun LY, Gong R, Liu Q, Long YK, Liu F, et al. The prevalence of EML4-ALK variants in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomark Med (2019) 13(12):1035–44. 10.2217/bmm-2018-0277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Takeuchi K, Choi YL, Togashi Y, Soda M, Hatano S, Inamura K, et al. KIF5B-ALK, a novel fusion oncokinase identified by an immunohistochemistry-based diagnostic system for ALK-positive lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2009) 15(9):3143–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell (2007) 131(6):1190–203. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Togashi Y, Soda M, Sakata S, Sugawara E, Hatano S, Asaka R, et al. KLC1-ALK: a novel fusion in lung cancer identified using a formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue only. PLoS One (2012) 7(2):e31323. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feng T, Chen Z, Gu J, Wang Y, Zhang J, Min L. The clinical responses of TNIP2-ALK fusion variants to crizotinib in ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer (2019) 137:19–22. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lai R, Ingham RJ. The pathobiology of the oncogenic tyrosine kinase NPM-ALK: a brief update. Ther Adv Hematol (2013) 4(2):119–31. 10.1177/2040620712471553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med (2014) 371(23):2167–77. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang YC, Zhou Q, Wu YL. Efficacy of crizotinib in first-line treatment of adults with ALK-positive advanced NSCLC. Expert Opin Pharmacother (2016) 17(12):1693–701. 10.1080/14656566.2016.1208171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu YL, Lu S, Lu Y, Zhou J, Shi YK, Sriuranpong V, et al. Results of PROFILE 1029, a Phase III Comparison of First-Line Crizotinib versus Chemotherapy in East Asian Patients with ALK-Positive Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol (2018) 13(10):1539–48. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, et al. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med (2017) 377(9):829–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa1704795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou C, Kim SW, Reungwetwattana T, Zhou J, Zhang Y, He J, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated Asian patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (ALESIA): a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Respir Med (2019) 7(5):437–46. 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30053-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shaw AT, Felip E, Bauer TM, Besse B, Navarro A, Postel-Vinay S, et al. Lorlatinib in non-small-cell lung cancer with ALK or ROS1 rearrangement: an international, multicentre, open-label, single-arm first-in-man phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18(12):1590–9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30680-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoshida T, Oya Y, Tanaka K, Shimizu J, Horio Y, Kuroda H, et al. Differential Crizotinib Response Duration Among ALK Fusion Variants in ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol (2016) 34(28):3383–9. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.8732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heuckmann JM, Balke-Want H, Malchers F, Peifer M, Sos ML, Koker M, et al. Differential protein stability and ALK inhibitor sensitivity of EML4-ALK fusion variants. Clin Cancer Res (2012) 18(17):4682–90. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lei YY, Yang JJ, Zhang XC, Zhong WZ, Zhou Q, Tu HY, et al. Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Variants and the Percentage of ALK-Positive Tumor Cells and the Efficacy of Crizotinib in Advanced NSCLC. Clin Lung Cancer (2016) 17(3):223–31. 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosenbaum JN, Bloom R, Forys JT, Hiken J, Armstrong JR, Branson J, et al. Genomic heterogeneity of ALK fusion breakpoints in non-small-cell lung cancer. Mod Pathol (2018) 31(5):791–808. 10.1038/modpathol.2017.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Newman AM, Bratman SV, Stehr H, Lee LJ, Liu CL, Diehn M, et al. FACTERA: a practical method for the discovery of genomic rearrangements at breakpoint resolution. Bioinformatics (2014) 30(23):3390–3. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol (2011) 29(1):24–6. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ali SM, Hensing T, Schrock AB, Allen J, Sanford E, Gowen K, et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling Identifies a Subset of Crizotinib-Responsive ALK-Rearranged Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Not Detected by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization. Oncologist (2016) 21(6):762–70. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pekar-Zlotin M, Hirsch FR, Soussan-Gutman L, Ilouze M, Dvir A, Boyle T, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and next-generation sequencing for detection of EML4-ALK rearrangement in lung cancer. Oncologist (2015) 20(3):316–22. 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dacic S, Villaruz LC, Abberbock S, Mahaffey A, Incharoen P, Nikiforova MN. ALK FISH patterns and the detection of ALK fusions by next generation sequencing in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget (2016) 7(50):82943–52. 10.18632/oncotarget.12705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hirai N, Sasaki T, Okumura S, Sado M, Akiyama N, Kitada M, et al. Novel ALK-specific mRNA in situ hybridization assay for non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res (2020) 9(2):257–68. 10.21037/tlcr.2020.03.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sanchez-Herrero E, Blanco Clemente M, Calvo V, Provencio M, Romero A. Next-generation sequencing to dynamically detect mechanisms of resistance to ALK inhibitors in ALK-positive NSCLC patients: a case report. Transl Lung Cancer Res (2020) 9(2):366–72. 10.21037/tlcr.2020.02.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Y, Zeng L, Zhou C, Li Y, Wu L, Xia C, et al. Detection of non-reciprocal/reciprocal ALK translocation as poor predictive marker in first-line crizotinib-treated ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol (2020) 15:1027–36. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luo J, Gu D, Lu H, Liu S, Kong J. Coexistence of a Novel PRKCB-ALK, EML4-ALK Double-Fusion in a Lung Adenocarcinoma Patient and Response to Crizotinib. J Thorac Oncol (2019) 14(12):e266–e8. 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gadgeel S, Peters S, Mok T, Shaw AT, Kim DW, Ou SI, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in treatment-naive anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALK+) non-small-cell lung cancer: CNS efficacy results from the ALEX study. Ann Oncol (2018) 29(11):2214–22. 10.1093/annonc/mdy405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jin Y, Bao H, Le X, Fan X, Tang M, Shi X, et al. Correction: Distinct co-acquired alterations and genomic evolution during TKI treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer patients with or without acquired T790M mutation. Oncogene (2020) 39(9):2027. 10.1038/s41388-019-1143-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Niida A, Nagayama S, Miyano S, Mimori K. Understanding intratumor heterogeneity by combining genome analysis and mathematical modeling. Cancer Sci (2018) 109(4):884–92. 10.1111/cas.13510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Santoni-Rugiu E, Melchior LC, Urbanska EM, Jakobsen JN, Stricker K, Grauslund M, et al. Intrinsic resistance to EGFR-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in EGFR-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Differences and Similarities with Acquired Resistance. Cancers (Basel) (2019) 11(7):923–79. 10.3390/cancers11070923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Solomon BJ, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, Felip E, et al. Final Overall Survival Analysis From a Study Comparing First-Line Crizotinib Versus Chemotherapy in ALK-Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol (2018) 36(22):2251–8. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.4794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

An overview of the study design. The flowchart for including advanced NSCLC patients for the retrospective study.

The pie diagram illustrating the percentage of patients in each ALK fusion group for 43 patients with baseline CGP (A) or for all 98 ALK-positive patients with either baseline or progressive disease CGP (B).

Paired baseline (before crizotinib treatment) and PD (disease progression after crizotinib treatment) mutations/CNVs of NSCLC patients with different ALK fusion patterns. N = 17. BL, baseline.

Pre-mature mRNA detected by RNA-seq revealed complex ALK fusions. (A) ALK intron1-ALK intron19 fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq; (B) EML4 intron6-ALK intron1 fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq.

GALNT14-ALK and SLC19A3 (IGR)-ALK fusions detected by CGP in one NSCLC patient (P62) resulted in a classic EML4-ALK fusion mRNA only. (A) GALNT14-ALK fusion was detected at the DNA level by DNA-seq. (B) SLC19A3 (IGR)-ALK fusion was detected at the DNA level by DNA-seq. (C) EML4-GALNT14 fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq. (D) GALNT14-ALK fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq. (E) Mature EML4-ALK v1 fusion was detected at the RNA level by mRNA-Seq. (F) Model for stepwise EML4-ALK fusion formation during gene transcription.

SETD2-ALK fusion detected by CGP in an NSCLC patient (P73) resulted in a classic EML4-ALK fusion mRNA. (A) EML4-SETD2 fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq. (B) SETD2-ALK fusion was detected in pre-mature mRNA by RNA-seq. (C) Mature EML4-ALK v5a fusion was detected at RNA levels by mRNA-seq. (D) Model for stepwise EML4-ALK fusion formation during gene transcription.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: NODE (http://www.biosino.org/node), accessions OEP001261 and OEP001269.