Abstract

A super-carbon-chain compound, named gibbosol C, featuring a polyoxygenated C70-linear-carbon-chain backbone encompassing two acyclic polyol chains, was obtained from the South China Sea dinoflagellate Amphidinium gibbosum. Its planar structure was elucidated by extensive NMR investigations, whereas its absolute configurations, featuring the presence of 36 carbon stereocenters and 30 hydroxy groups, were successfully established by comparison of NMR data of the ozonolyzed products with those of gibbosol A, combined with J-based configuration analysis, Kishi’s universal NMR database, and the modified Mosher’s MTPA ester method. Multi-segment modification was revealed as the smart biosynthetic strategy for the dinoflagellate to create remarkable super-carbon-chain compounds with structural diversity.

Keywords: marine dinoflagellate, Amphidinium gibbosum, super-carbon-chain compound, absolute configuration, multi-segment modification

1. Introduction

Marine dinoflagellates produce huge organic molecules, particularly super-carbon-chain compounds (SCCCs), which are complex natural products with numerous carbon stereocenters on a long-carbon-chain backbone [1,2,3,4]. According to the structural feature of backbones, SCCCs can be categorized into two classes, viz., polyol-polyene and polyol-polyol compounds.

To date, most reported SCCCs are polyol-polyene compounds, such as amphidinol homologs [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] and karlotoxin congeners [17,18,19,20,21,22], characterized by the presence of both a polyol and a polyene chain, connected by a central core containing two tetrahydropyran rings. Polyol-polyene compounds, mainly isolated from marine dinoflagellates of the genera Amphidinium and Karlodinium, exhibit antifungal, antitumor, antiosteoclastic, and analgesic effects [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. These SCCCs can specifically bind to membrane cholesterol or ergosterol and then disrupt cell membranes without altering their integrity [23].

Polyol-polyol compounds, however, are SCCCs featuring the presence of two polyol chains connected by a central core containing tetrahydropyran rings. So far, few examples have been reported. Ostreol B, isolated from the marine dinoflagellate Ostreopsis cf. ovata, could be classified as a polyol-polyol compound, although it only contains a tetrahydropyran ring as the central core [24]. Previously, two SCCCs with activation or inhibitory effects on the expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, named gibbosols A and B (Figure 1a), were obtained by our team from the South China Sea dinoflagellate Amphidinium gibbosum. After years of unremitting effort, the planar structures and absolute configurations of these SCCCs have been completely established by a combined chemical, spectroscopic, and computational approach [25]. Gibbosols A and B represent a new type of polyol-polyol SCCC. During our ongoing investigation of SCCCs from the same dinoflagellate, a minor polyol-polyol SCCC, named gibbosol C (1) (3.0 mg) (Figure 1b), was obtained by the aid of the UPLC-MS/MS technique. The structures of the C-1–C-4, C-11–C-17, and C-34–C-35 segments within the starting polyol chain of gibbosol C (1) were different from those of gibbosol A. In this work, the isolation, planar structure elucidation, and stereochemical assignment of gibbosol C (1) are reported.

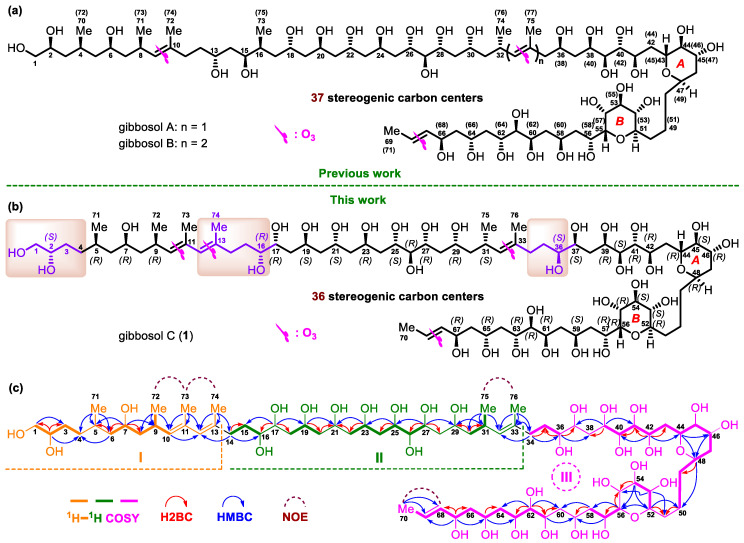

Figure 1.

(a) The structures and absolute configurations of gibbosols A and B. (b) The structure and absolute configurations of gibbosol C (1). (c) Key 1H–1H COSY, H2BC, and HMBC correlations and diagnostic NOE interactions of gibbosol C (1).

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Planar Structure and Ozonolysis of Gibbosol C (1)

The molecular formula of 1 was established as C76H142O32 with six degrees of unsaturation by the positive high resolution-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry [(+)-HR-ESI-MS)] ions at m/z 784.4814 ([M + 2H]2+, calcd 784.4815) and 1567.9579 ([M + H]+, calcd 1567.9557). According to the 1H and 13C NMR data of 1 (Table 1), four degrees of unsaturation result from four carbon–carbon double bonds. Thus, the molecule must contain two rings. The 13C NMR data and the DEPT135 experiment of 1 indicated the presence of 76 carbon resonances that can be categorized as seven methyl groups, 25 methylene groups (including an oxymethylene), 41 methine groups (including 5 olefinic and 33 oxymethine groups), and three non-protonated olefinic carbons.

Table 1.

1H (700 MHz) and 13C (175 MHz) NMR data for 1 in CD3OD.

| No. | δH (J in Hz) | δC, Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | 3.41, m | 67.4, CH2 |

| 1b | 3.45, m | |

| 2 | 3.53, m | 73.6, CH |

| 3a | 1.39, m | 31.9, CH2 |

| 3b | 1.48, m | |

| 4a | 1.32, m | 34.8, CH2 |

| 4b | 1.32, m | |

| 5 | 1.65, m f | 30.5, CH |

| 6a | 1.12, m | 47.1, CH2 |

| 6b | 1.46, m | |

| 7 | 3.62, m | 68.5, CH |

| 8a | 1.28, m | 47.4, CH2 |

| 8b | 1.43, m a | |

| 9 | 2.74, m | 30.6, CH |

| 10 | 4.92, br d (9.8) i | 136.2, CH |

| 11 | 133.3, qC | |

| 12 | 5.67, br s | 130.3, CH |

| 13 | 136.3, qC | |

| 14a | 2.08, m | 37.7, CH2 |

| 14b | 2.26, m | |

| 15a | 1.47, m | 32.3, CH2 |

| 15b | 1.74, m | |

| 16 | 3.42, m | 75.81, CH |

| 17 | 3.70, m | 72.8, CH |

| 18a | 1.50, m | 41.2, CH2 |

| 18b | 1.67, m e | |

| 19 | 4.10, m | 66.5, CH |

| 20a | 1.58, m b | 46.9, CH2 |

| 20b | 1.58, m b | |

| 21 | 4.09, m j | 66.4, CH |

| 22a | 1.58, m b | 46.9, CH2 |

| 22b | 1.58, m b | |

| 23 | 4.12, m | 66.3, CH |

| 24a | 1.54, m | 41.5, CH2 |

| 24b | 1.79, m | |

| 25 | 3.88, m | 70.5, CH |

| 26 | 3.37 t, (6.3) | 78.8, CH |

| 27 | 3.83, m | 73.1, CH |

| 28a | 1.58, m b | 41.0, CH2 |

| 28b | 1.80, m | |

| 29 | 3.78, m | 70.2, CH |

| 30a | 1.35, m | 46.8, CH2 |

| 30b | 1.43, m a | |

| 31 | 2.69, m | 30.1, CH |

| 32 | 4.92, br d (9.8) i | 132.1, CH |

| 33 | 135.5, CH | |

| 34a | 2.04, m | 37.1, CH2 |

| 34b | 2.19, m | |

| 35a | 1.55, m c | 32.44, CH2 |

| 35b | 1.69, m | |

| 36 | 3.44, m | 74.7, CH |

| 37 | 3.69, m | 73.5, CH |

| 38a | 1.77, m g | 37.4, CH2 |

| 38b | 1.81, m | |

| 39 | 4.13, m | 70.36, CH |

| 40 | 3.46, m | 74.6, CH |

| 41 | 3.69, m | 75.7, CH |

| 42 | 4.04, m | 70.06, CH |

| 43a | 1.77, m g | 34.9, CH2 |

| 43b | 1.98, m | |

| 44 | 3.67, m | 70.9, CH |

| 45 | 3.03, t (8.4) | 77.6, CH |

| 46 | 3.75, m | 70.4, CH |

| 47a | 1.70, m | 37.6, CH2 |

| 47b | 1.88, m | |

| 48 | 3.93, m | 73.2, CH |

| 49a | 1.38, m | 32.4, CH2 |

| 49b | 1.91, m | |

| 50a | 1.53, m | 23.4, CH2 |

| 50b | 1.53, m | |

| 51a | 1.52, m d | 32.8, CH2 |

| 51b | 1.75, m | |

| 52 | 3.41, m | 76.5, CH |

| 53 | 3.14, t (7.7) | 75.2, CH |

| 54 | 3.72, t (7.7) | 75.1, CH |

| 55 | 3.78, m | 73.8, CH |

| 56 | 3.60, dd (9.1, 4.9) | 75.76, CH |

| 57 | 4.39, m | 67.7, CH |

| 58a | 1.52, m d | 42.1, CH2 |

| 58b | 1.85, m h | |

| 59 | 4.09, m j | 67.1, CH |

| 60a | 1.67, m e | 42.7, CH2 |

| 60b | 1.85, m h | |

| 61 | 4.09, m | 69.7, CH |

| 62 | 3.24, dd (7.7, 1.4) | 77.1, CH |

| 63 | 3.82, m | 71.9, CH |

| 64a | 1.59, m | 42.2, CH2 |

| 64b | 1.94, m | |

| 65 | 4.08, m j | 68.7, CH |

| 66a | 1.55, m c | 45.7, CH2 |

| 66b | 1.65, m f | |

| 67 | 4.26, m | 70.1, CH |

| 68 | 5.51, ddq (14.7, 6.3, 1.4) | 135.9, CH |

| 69 | 5.66, m | 126.4, CH |

| 70 | 1.68, br d (6.3) | 17.9, CH3 |

| 71 | 0.88, d (6.3) | 19.7, CH3 |

| 72 | 0.96, d (6.3) | 22.2, CH3 |

| 73 | 1.72, br s | 17.6, CH3 |

| 74 | 1.76, br s | 18.1, CH3 |

| 75 | 0.94, d (7.0) | 22.4, CH3 |

| 76 | 1.68, br s | 16.7, CH3 |

a–j Overlapped signals assigned by 1H–1H COSY, HSQC, H2BC, and HMBC spectra without designating multiplicity.

Three substructures, viz., I (from C-1 to C-13, C-71, C-72, C-73, and C-74, in orange), II (from C-14 to C-33, C-75, and C-76, in green), and III (from C-34 to C-70, in pink), were determined by analysis of key 1H–1H COSY, H2BC, and HMBC correlations of 1 (Figure 1c).

For substructure I, the linear connection of C-1 to C-4 was indicated by the proton spin system H2-1–H-2–H2-3–H2-4, which was deduced from the corresponding 1H–1H COSY correlations; H2BC correlations from H-2/C-1 and H-2/C-3; and HMBC correlations from H-2/C-4 and H2-1/C-3. Similarly, the linear connection of C-6 to C-10 and the branched connection of C-9 and C-72 were revealed by the proton spin system H2-6–H-7–H2-8–H-9(H3-72)–H-10, H2BC correlations from H-7/C-6 and H-7/C-8, and HMBC correlations from H-7/C-9, H3-72/C-8, H3-72/C-9, and H3-72/C-10. The linear connection of C-4 to C-6 and the branched connection of C-5 and C-71 were corroborated by the H2BC correlation from H-6/C-5 and HMBC cross-peaks from H3-71/C-4, H3-71/C-5, H3-71/C-6, and H-7/C-5, whereas the linear connection of C-10 to C-13 and the branched connections from C-11/C-73 and C-13/C-74 were confirmed by HMBC cross-peaks from H-10/C-12, H3-73/C-10, H3-73/C-11, H3-73/C-12, H3-74/C-12, and H3-74/C-13. Taken together, the planar structure of I was elucidated (Figure 1c).

For substructure II, the linear connection of C-14 to C-16 was revealed by 1H–1H COSY correlations between H2-14/H2-15 and H2-15/H-16, H2BC correlations between H2-14/C-15, and HMBC cross-peaks between H2-14/C-16. Similarly, the linear connection of C-16 to C-27 was corroborated by two proton spin systems, H2-18–H-19–H2-20 and H2-22–H-23–H2-24–H-25– H-26–H-27; H2BC correlations between H-17/C-16, H-17/C-18, H-19/C-20, H2-20/C-21, H2-22/C-21, H-23/C-22, H-25/C-24, and H-27/C-26; and key HMBC cross-peaks between H-17/C-15, H-17/C-19, H-19/C-21, H-23/C-21, H-25/C-23, and H-27/C-25. In addition, the linear connection of C-27 to C-33 and the branched connections between C-31/C-75 and C-33/C-76 were established by 1H–1H COSY correlations between H2-30/H-31 and H3-75/H-31, H2BC correlations between H-27/C-28, H2-30/C-29, and H2-30/C-31, and HMBC cross-peaks between H-27/C-29, H-31/C-29, H3-75/C-30, H3-75/C-31, H3-75/C-32, H3-76/C-32, and H3-76/C-33. Taken together, the planar structure of II was assigned (Figure 1c).

For substructure III, the linear connection of C-34 to C-70 was undoubtedly elucidated by 1H–1H COSY, H2BC, and HMBC correlations (Figure 1c). The linear connection of C-34 to C-36 was revealed by 1H–1H COSY correlations from H2-34/H2-35 and H2-35/H-36, H2BC correlations from H2-34/C-35 and H-36/C-35, and HMBC cross-peaks from H2-34/C-36. The linear connections of C-39 to C-50, C-52 to C-54, C-56 to C-58, and C-61 to C-70 were confirmed by four proton spin systems, viz., H-39–H-40–H-41–H-42–H2-43–H-44–H-45–H-46–H2-47–H-48–H2-49–H2-50, H-52–H-53–H-54, H-56–H-57–H2-58, and H-61–H-62–H-63–H2-64–H-65–H2-66–H-67–H-68–H-69–H3-70; H2BC correlations from H-41/C-40, H-42/C-41, H-42/C-43, H-48/C-49, H-56/C-57, H-62/C-61, H-62/C-63, H-65/C-64, H-67/C-66, and H-67/C-68; and HMBC cross-peaks from H-39/C-41, H-42/C-40, H-42/C-44, H-44/C-46, H-46/C-48, H-48/C-50, H-54/C-52, H-56/C-58, H-62/C-64, H-65/C-63, H-67/C-65, H-67/C-69, H3-70/C-68, and H3-70/C-69. The linear connections of C-37 to C39, C-50 to C52, C-54 to C56, and C-58 to C-61 were resolved by H2BC correlations from H-39/C-38, H2-50/C-51, H-52/C-51, H-54/C-55, H-56/C-55, H2-58/C-59, and H-61/C-60 and crucial HMBC correlations from H-39/C-37, H-52/C-50, H-53/C-51, H-53/C-55, H-54/C-56, H-57/C-59, H2-58/C-60, H-61/C-59, and H-62/C-60 (Figure 1c)

The presence of two tetrahydropyran moieties in III was indicated by isotope shift experiments, measured in both CD3OD and CD3OH [26]. Four oxymethine carbons involved in ether linkage, viz., C-44 (δ 70.9), C-48 (δ 73.2), C-52(δ 76.5), and C-56 (δ 75.76), did not exhibit a deuterium-induced isotope shift. The presence of ether bridges between C-44/C-48 and C-52/C-56, respectively, was further supported by HMBC cross-peaks from H-44/C-48 and H-52/C-56. Taken together, the backbone of III was assembled (Figure 1c).

Finally, crucial HMBC cross-peaks from H3-74/C-14 and H2-14/C-12 confirmed the connection between I and II through C-13−C-14, whereas the correlations from H3-76/C-34, H2-34/C-32, and H2-34/C-33 revealed the connection between II and III through C-33−C-34. The large value of 3JH-68,H-69 (14.7 Hz) and NOE correlations from H3-72/H3-73, H-10/H-12, H3-75/H3-76, H-32/H2-34, and H3-70/H-68 concluded that the geometries of the four carbon–carbon double bonds in 1, viz., C10═C11, C12═C13, C32═C33, and C68═C69, were all E-configured. Based on the above results, the planar structure of 1, containing 30 hydroxy groups and six pendant methyl moieties, was successfully established (Figure 1c).

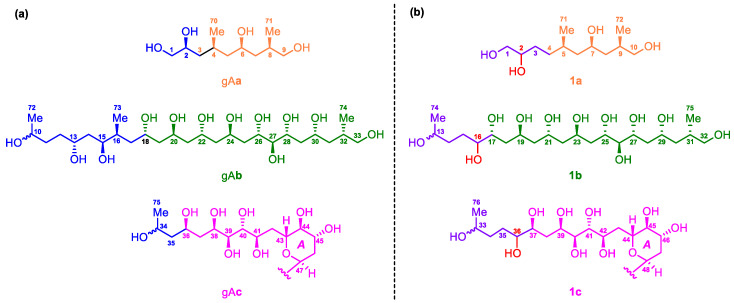

Due to the heavy overlap of the 1H and 13C NMR signals of 1, the relative configurations of its stereogenic carbons could not be determined based on various 1D and 2D NMR data of the intact 1. Comparison of the planar structure of 1 with that of gibbosol A (Figure 1) revealed that the structures of the C-5–C-11, C-17–C-33, and C-37–C-70 segments in 1 are the same as those of the C-4–C-10, C-18–C-34, and C-36–C-69 segments in gibbosol A, respectively. Based on the same biosynthetic machinery, the absolute configurations of the corresponding segments above should be identical. With detailed NMR data of three ozonolyzed products of gibbosol A (viz., gAa–c, Figure 2a) at hand [25], ozonolysis reaction was carried out for 1 to obtain the corresponding NMR data for comparison. As a result, O3/NaBH4-mediated cleavage of the carbon–carbon double bonds of 1 afforded three main fragments, viz., 1a, 1b, and 1c (Figure 2b, Tables S1–S3). Both 1b and 1c were obtained as epimeric pairs at C-13 and C-33, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Structures of the ozonolyzed fragments gAa–c of gibbosol A. (b) Structures of the ozonolyzed fragments 1a–1c of gibbosol C (1).

2.2. Relative and Absolute Configurations of Gibbosol C (1)

Because gibbosols A and C were produced by the same marine dinoflagellate, the common biosynthetic origins of the two SCCCs should lead to identical absolute configurations of the corresponding segments in the three main pairs of the ozonolyzed fragments above. Detailed analysis of the NMR data led to the conclusion that the relative configurations of 1a, 1b, and 1c were similar to those of gAa, gAb, and gAc, respectively, except for the insertion of an additional methylene group between C-2 and C-4 in 1a, the presence of an additional 16-OH group in 1b and an additional 36-OH group in 1c, and the absence of the 13,15-diol and 16-Me (Me-73 in gAb) groups in 1b (Figure 2). Coincidentally, all these modifications appear on the starting segments within three ozonolyzed products of gibbosol A [25].

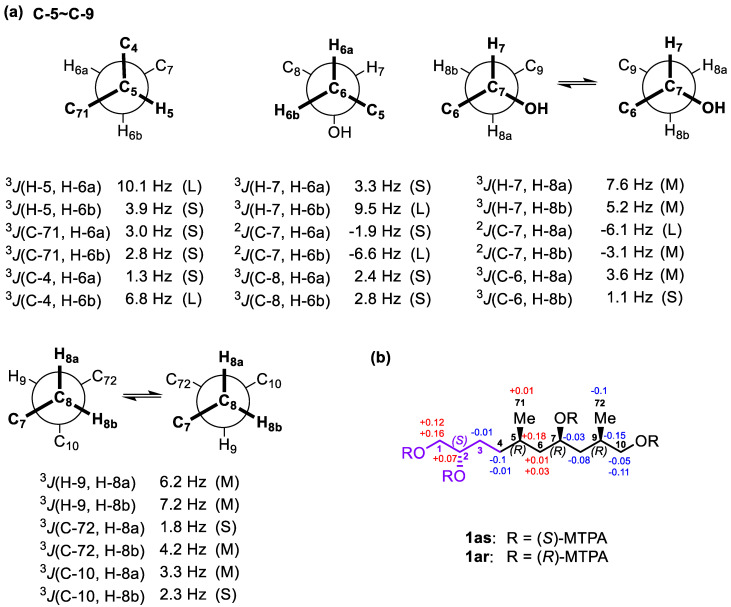

For the C-5−C-7 segment of 1a, J-based configuration analysis (JBCA) [27,28] was used (Figure 3a). 3JH,H values were measured by 2D J-resolved spectroscopy (2D JRES), whereas 2,3JC,H values were obtained by the HETLOC experiment. The anti orientations between H-5/H-6a and H-7/H-6b were assigned by the large values of 3JH-5,H-6a (10.1 Hz) and 3JH-7,H-6b (9.5 Hz), respectively, whereas the gauche orientations between H-5/H-6b and H-7/H-6a were proved by the small values of 3JH-5,H-6b (3.9 Hz) and 3JH-7,H-6a (3.3 Hz), respectively. The anti orientations between C-4/H-6b and 7-OH/H-6a were deduced from the large value of 3JC-4,H-6b (6.8 Hz) and the small value of 2JC-7,H-6a (−1.9 Hz), respectively. The gauche orientations between C-71/H-6a, C-71/H-6b, C-4/H-6a, C-8/H-6a, C-8/H-6b, and 7-OH/H-6b were established by the small values of 3JC-71,H-6a (3.0 Hz), 3JC-71,H-6b (2.8 Hz), 3JC-4,H-6a (1.3 Hz), 3JC-8,H-6a (2.4 Hz), and 3JC-8,H-6b (2.8 Hz) and the large value of 2JC-7,H-6b (−6.6 Hz), respectively. Thus, the relative configuration between Me-71/7-OH in 1a was concluded to be syn (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Rotamers and coupling constants for the C-5–C-9 segment of 1a. (b) ΔδSR values obtained for 1a.

The intermediate values of 3JH-7,H-8a (7.6 Hz) and 3JH-7,H-8b (5.2 Hz) indicated two interconverting conformations for both H-7/H-8a and H-7/H-8b. Similarly, those of 2JC-7,H-8b (−3.1 Hz) and 3JC-6,H-8a (3.6 Hz) suggested two alternating conformations for both 7-OH/H-8b and C-6/H-8a. The large value of 2JC-7,H-8a (−6.1 Hz) and the small value of 3JC-6,H-8b (1.1 Hz) revealed that both 7-OH/H-8a and C-6/H-8b remained in gauche orientations. Thus, two alternating conformers were assigned for the C-7−C-8 segment (Figure S1). Similarly, the intermediate values of 3JH-9,H-8a (6.2 Hz) and 3JH-9,H-8b (7.2 Hz) indicated two interconverting conformations for both H-9/H-8a and H-9/H-8b. Those of 3JC-72,H-8b (4.2 Hz) and 3JC-10,H-8a (3.3 Hz) suggested two alternating conformations for both C-72/H-8b and C-10/H-8a. The small values of 3JC-72,H-8a (1.8 Hz) and 3JC-10,H-8b (2.3 Hz) revealed that both C-72/H-8a and C-10/H-8b were in gauche orientations. Therefore, two alternating conformers were assigned for the C-8−C-9 segment. Based on the results above, the relative configuration between 7-OH/Me-72 was determined as syn (Figure 3a).

To determine the absolute configurations of C-2, C-7, and C-9 in 1a, the modified Mosher’s MTPA method was used. Through a comparison of the sign of ΔδSR values between 1as/1ar, the absolute configurations of C-2 and C-7 in 1a were determined to be S and R (Figure 3b), respectively [29]. In addition, the absolute configuration of C-9 was assigned as R by the widely separated H2-10 signals of 1ar (δ 4.29, 4.18) when compared with those of 1as (δ 4.18, 4.13) [30,31]. Based on this syn relationship between Me-71 and 7-OH, the absolute configuration of C-5 in 1a was established as R. Therefore, the absolute configurations of the stereogenic carbons in 1a were established as 2S,5R,7R,9R (Figure 3b), which are the same as those in gAa.

Based on Kishi’s universal NMR database, the relative configurations of the C-17−C-25 segment in 1b were assigned as (anti/anti/anti/anti), the same as those of the C-18−C-26 segment in gAb (Figure 2) [25], by chemical shifts of three central carbons of the consecutive 1,3,5-triol moieties, viz., C-19 (δ 66.5), C-21 (δ 66.4), and C-23 (δ 66.4) [32,33].

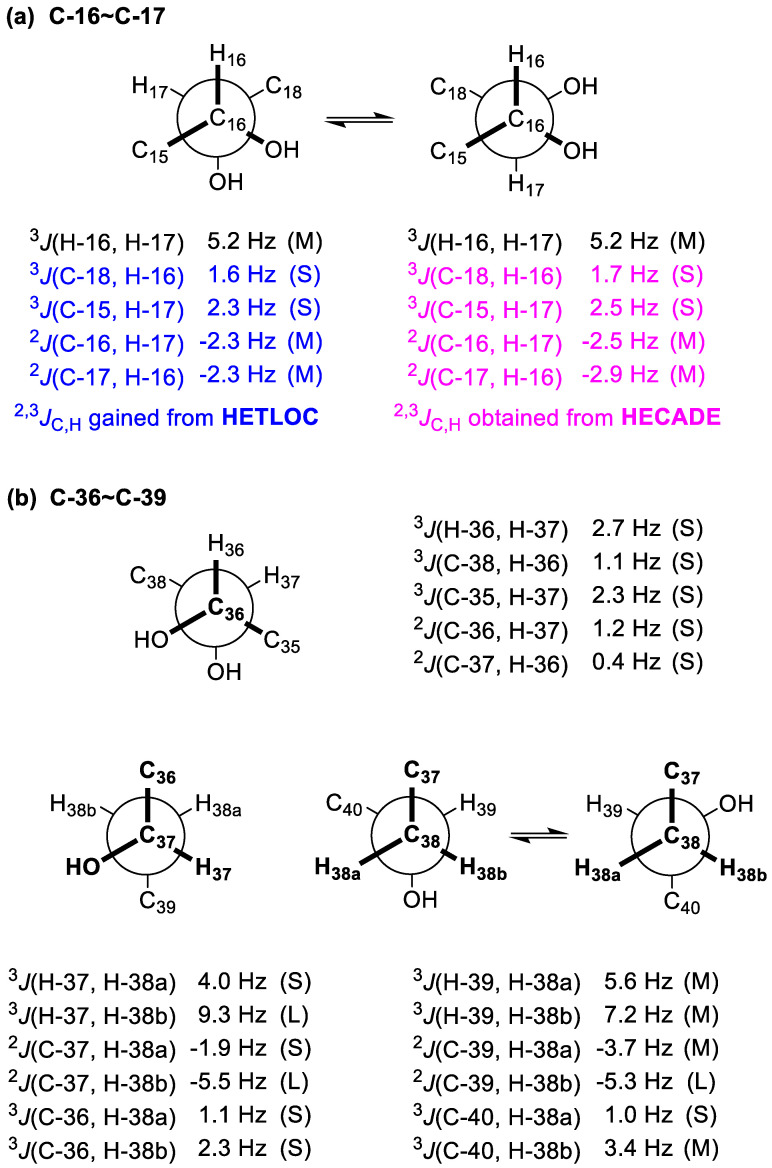

To establish the relative configuration between 16-OH and 17-OH, JBCA [27,28] was used. 2,3JC,H values were obtained by both the HETLOC and HECADE experiments (Figure 4a). Though the observed 3JH-16,H-17, 2JC-16,H-17, and 2JC-17,H-16 values fell into the intermediate range, implying interconversion between two conformers, the gauche orientations between C-18/H-16 and C-15/H-17 were undoubtedly determined by the small values of 3JC-18,H-16 (1.6 Hz from HETLOC and 1.7 Hz from HECADE) and 3JC-15,H-17 (2.3 Hz from HETLOC and 2.5 Hz from HECADE). Accordingly, the relationship between 16-OH and 17-OH was concluded to be syn (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

(a) Rotamers and coupling constants for the C-16–C-17 segment of 1b. (b) Rotamers and coupling constants for the C36–C39 segment of 1c.

For the C-36−C-37 segment, the gauche orientation between H-36 and H-37 was supported by the small value of 3JH-36,H-37 (2.7 Hz). The gauche orientations between C-38 and H-36 and between C-35 and H-37 were revealed by the small values of 3JC-38,H-36 (1.1 Hz) and 3JC-35,H-37 (2.3 Hz), while the anti orientations between 36-OH and H-37 and between 37-OH and H-36 were deduced from the small values of 2JC-36,H-37 (1.2 Hz) and 2JC-37,H-36 (0.4 Hz). Therefore, the relationship between 36-OH and 37-OH was concluded to be syn (Figure 4b).

The relative configurations of the C-37–C-39 segment in 1c were determined to be the same as that of the C-36–C-38 segment of gAc by JBCA [27,28] (Figure 4b). For the C-37−C-38 segment, the gauche orientation between H-37 and H-38a was determined by the small value of 3JH-37,H-38a (4.0 Hz), while the anti orientation between H-37 and H-38b was assigned by the large value of 3JH-37,H-38b (9.3 Hz). Similarly, the anti orientation between 37-OH and H-38a was established by the small value of 2JC-37,H-38a (−1.9 Hz), whereas the gauche orientation between 37-OH and H-38b was established by the large value of 2JC-37,H-38b (−5.5 Hz). In addition, the gauche orientations between C-36 and H-38a and between C-36 and H-38b were suggested by the small values of 3JC-36,H-38a (1.1 Hz) and 3JC-36,H-38b (2.3 Hz), respectively. For the C-38−C-39 segment, the intermediate values of 3JH-39,H-38a (5.6 Hz) and 3JH-39,H-38b (7.2 Hz) indicated two interconverting conformations for both H-39/H-38a and H-39/H-38b. Similarly, those of 2JC-39,H-38a (−3.7 Hz) and 3JC-40,H-38b (3.4 Hz) suggested two alternating configurations for both 39-OH/H-38a and C-40/H-38b. The gauche orientations between 39-OH/H-38b and C-40/H-38a were deduced from the large value of 2JC-39,H-38b (−5.3 Hz) and the small value of 3JC-40,H-38a (1.0 Hz). Accordingly, the relationship between 37-OH and 39-OH was concluded to be syn. Finally, the relative configurations of the C-36−C-39 segment in 1c were concluded to be syn/syn (Figure 4b).

Furthermore, the relative configurations of the C-39−C-42 segment in 1c were assigned as syn/anti/anti (Table S1), the same as those of the C-38−C-41 segment in gAc [25], on the basis of Kishi’s universal NMR database [27,28].

Based on the absolute configurations of the C-17–C-25 and C-37–C-42 segments of 1, viz., 17R,19S,21S,23R,25S and 37S,39R,40S,41R,42R, which were deduced from those of the corresponding segments of gibbosol A, the absolute configurations of C-16 in 1b and of C-37 in 1c were assigned as R and S, respectively. In summary, the absolute configurations of 36 stereogenic carbons in gibbosol C (1) were established as 2S, 5R, 7R, 9R, 16R, 17R, 19S, 21S, 23R, 25S, 26R, 27R, 29R, 31S, 36S, 37S, 39R, 40S, 41R, 42R, 44R, 45S, 46R, 48R, 52R, 53S, 54S, 55R, 56R, 57R, 59S, 61R, 62R, 63R, 65R, and 67R (Figure 1b).

In the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) promote the accumulation of macrophages within the intima, leading to formation of the atherosclerotic lesion [34,35,36]. The above two adhesion molecules, particularly VCAM-1, have been considered as potential therapeutic targets for anti-atherogenic drug development [37]. It is important to find promising VCAM-1 inhibitors from natural products. Thus, the effects of gibbosol C (1) on VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells were investigated according to previous procedures [25]. At the concentration range of 10.0 and 100.0 μg/mL, gibbosol C (1) showed no obvious activities on VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression (Figure S1), whereas gibbosol A displayed remarkable activation effects on VCAM-1 expression. On the contrary, gibbosol B exhibited marked inhibitory activities on VCAM-1 expression [25].

The co-isolation of gibbosols A–C enabled us to summarize their structural features, which may shed light on the biosynthesis of these polyol-polyol SCCCs. The 13 carbon central cores (C-43–C-55); the C-4–C-10, C-18–C-34, and C-36–C-42 segments of the starting polyol chain; and the whole terminal polyol chain (C-56–C-69) of gibbosol A are quite conserved, whereas other segments of the starting polyol chain are variable. Diverse modification patterns, such as insertion, substitution, oxidation, and reduction, appear on the C-1–C-4, C-11–C-17, or C-34–C-35 segment of the starting polyol chain of gibbosol A. In other words, multi-segment modification on the starting polyol chain is the biosynthetic strategy for the generation of gibbosol C (1).

In addition, glycolate should be the starter unit in the biosynthesis of gibbosols A–C [38]. Though acetate labeling patterns of some polyol-polyene SCCCs, such as amphidinols A [38], 4 [2,39], and 17 [39,40], have been reported, no enzymatic mechanisms involved in the biosynthesis of these SCCCs have been uncovered so far [38,39,40,41]. Of course, the acetate labeling patterns of gibbosols A–C are worthy of further investigation in future.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

HR-ESI-MS was obtained on a Bruker maXis ESI-QTOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) in the positive-ion mode. LR-ESI-MS was recorded on a Bruker amaZon SL mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) in both the positive- and negative-ion modes. One- and two-dimensional NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker AV-700 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker Scientific Technology Co. Ltd., Karlsruhe, Germany). UV spectra were recorded on a UV-2600 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan) and optical rotations determined on an MCP 500 modular circular polarimeter (Anton Paar GmbH, Seelze, Germany) with a 1.0 cm cell at 25 °C. Preparative HPLC was performed on a Waters 2535 pump equipped with a YMC C18 reversed-phase column (250 × 10 mm i.d., 5 μm, Kyoto, Japan) and a 2998 photodiode array detector coupled with a 2424 evaporative light scattering detector (Waters Corporation, Milford, NY, USA). For column chromatography, silica gel (100–200 mesh, Qingdao Mar. Chem. Ind. Co. Ltd., Qingdao, China) and C18 reversed-phase silica gel (ODS-A-HG 12 nm, 50 µm, YMC, Kyoto, Japan) were employed.

3.2. Isolation of the Dinoflagellate and the Large-Scale Culture

The isolation and culture of the marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium gibbosum was described in our previous publication [25].

3.3. Isolation of Gibbosol C (1)

The filtrate of the culture medium (1200 L) was loaded onto a macroporous resin column (DIAION, HP-20, 120 cm × 15 cm i.d.), eluted with freshwater to remove sea salt. The loaded sample was successively eluted with 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% aqueous ethanol. All the eluates were concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the resultant solid (5.5 g), which was separated by a C18 reversed-phase column (60 × 5 cm i.d.), eluted with an aqueous methanol solution (10% to 100%) to yield 83 fractions. UPLC-MS (Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 150 × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 μm, MeCN/H2O, from 5:95 to 98:2) was used for the detection of super-carbon-chain compounds in these fractions. Fractions 62 and 63 (23.6 mg) were combined and purified by HPLC (YMC-Pack 250 × 4.6 mm i. d., MeCN/H2O, 21:79) to give 1 (3.2 mg, tR = 60.5 min).

Gibbosol C (1): Colorless solid, = + 9.3 (c = 0.08, methanol); UV (MeCN) λmax (log ε) 203.6 (3.9), 230.2 (3.6) nm; for 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data, see Table 1; HR-ESI-MS m/z [M + 2H]2+ (calcd for C76H144O32, 784.4814, found 784.4815) and [M + H]+ (calcd for C76H143O32, 1567.9579, found 1567.9557).

3.4. Ozonolysis

Gibbosol C (1) (3.0 mg, 0.002 mM) was dissolved in a mixture of CH2Cl2–MeOH (1:1, each 2 mL). Ozone was bubbled into the above solution at –78 °C for 2 min. An excess amount of NaBH4 was then added and stirred at –78 °C for 3 h. The reaction mixture was purified by a C18 reversed-phase silica gel column (Daisogel, SP-120-50-ODS-B, 3 g, 5.0 cm × 1.0 cm i.d.), eluted with 10 mL of water followed by 15 mL of MeOH, to afford three fractions. The second fraction was purified by HPLC (Cosmosil, HILIC, 250 × 4.6 mm i. d., MeCN/H2O, 90:10−50:50) to afford three products, viz., fragments 1a (0.4 mg, tR = 4.9 min), 1b (0.9 mg, tR = 50.8 min), and 1c (1.3 mg, tR = 72.7 min) (Figure 2).

1a: For 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data, see Table S2; LR-ESI-MS m/z 257.6 [M + Na]+ and 491.6 [2M + Na]+.

1b: For 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data, see Table S3; LR-ESI-MS m/z 487.6 [M + H]+ and 509.5 [M + Na]+.

1c: For 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data, see Table S4; LR-ESI-MS m/z 869.4 [M + H]+ and 891.3 [M + Na]+.

3.5. Mosher’s MTPA Esters 1as and 1ar

The fragment 1a (0.3 mg) was treated with (R)-MTPACl (8.0 μL) in dried pyridine (0.8 mL) at room temperature for 10 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by HPLC (YMC-Pack 250 cm × 4.6 mm i.d., MeCN/H2O, 92:8) to afford the (S)-MTPA ester 1as (1.1 mg). The (R)-MTPA ester 1ar (1.0 mg) was prepared in the same way. With the aid of key 1H–1H COSY correlations, 1H NMR spectroscopic data of 1as and 1ar were assigned (Table S5).

1as: For 1H NMR spectroscopic data, see Table S5; LR-ESI-MS m/z 1116.4 [M + NH4]+ and 1121.2 [M + Na]+.

1ar: For 1H NMR spectroscopic data, see Table S5; LR-ESI-MS m/z 1116.4 [M + NH4]+ and 1121.3 [M + Na]+.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a new polyol-polyol SCCC, named gibbosol C, was isolated from the South China Sea dinoflagellate A. gibbosum. Its planar structure and absolute configurations, featuring the presence of 36 carbon stereocenters and 30 hydroxy groups, were successfully established by extensive NMR investigations, ozonolysis of the carbon–carbon double bonds, J-based configuration analysis, Kishi’s universal NMR database, the modified Mosher’s MTPA ester method, and comparison of the NMR data of the ozonolyzed products with those of gibbosol A. Multi-segment modification seems to be the smart biosynthetic strategy for the dinoflagellate to create remarkable SCCCs with diverse structures. Marine dinoflagellates of the genus Amphidinium harbor novel and complex SCCC biosynthetic routes. New integrated chemical, spectroscopic, and computational approaches or intelligent databases should be developed to cope with the stereochemical complexity of SCCCs. Evidently, specific carbon–carbon bond cleavages are an important means for the determination of the relative and absolute configurations of polyol-polyol SCCCs in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ai-Jun Sun and Yun Zhang (South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for the measurement of HR-ESI-MS. We thank Zhihui Xiao (Equipment Public Service Center, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for recording the 700 MHz NMR spectra.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/18/12/590/s1, Tables S1–S5, Figure S1, 1H-NMR data for 1a–1c, 1as, and 1ar; and 13C-NMR data for 1a–1c (PDF). Copies of the high-performance liquid chromatogram, the UV spectrum, HR-ESI-MS for 1; LR-ESI-MS for 1a–1c, 1as, and 1ar; and 1D and 2D NMR spectra for 1, 1a–1c, 1as, and 1ar (PDF).

Author Contributions

L.S. and J.W. conceived and designed the experiments; Z.L. performed the large-scale culture of the marine dinoflagellate, W.-S.L. performed the chemistry part of the experiments and analyzed the data; Y.-L.Z. and Y.Y. performed the bioactivity part of the experiments and analyzed the data; W.-S.L. and J.W. wrote the draft; L.S. and J.W. revised the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by grants from the Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars, China (2020B1515020056) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770377 and 81661148049).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kobayashi J., Ishibashi M. Bioactive metabolites of symbiotic marine microorganisms. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1753–1769. doi: 10.1021/cr00021a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi J., Kubota T. Bioactive macrolides and polyketides from marine dinoflagellates of the genus Amphidinium. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:451–460. doi: 10.1021/np0605844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uemura D. Bioorganic studies on marine natural products-diverse chemical structures and bioactivities. Chem. Rec. 2006;6:235–248. doi: 10.1002/tcr.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kita M., Uemura D. Marine huge molecules: The longest carbon chains in natural products. Chem. Rec. 2010;10:48–52. doi: 10.1002/tcr.200900030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satake M., Murata M., Yasumoto T., Fujita T., Naoki H. Amphidinol, a polyhydroxypolyene antifungal agent with an unprecedented structure, from a marine dinoflagellate, Ampbidnium klebsii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9859–9861. doi: 10.1021/ja00026a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murata M., Matsuoka S., Matsumori N., Paul G.K., Tachibana K. Absolute configuration of amphidinol 3, the first complete structure determination from amphidinol homologues: Application of a new configuration analysis based on carbon-hydrogen spin-coupling constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:870–871. doi: 10.1021/ja983655x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang X., Zhao D., Guo Y., Wu H., Lin L., Wang Z., Ding J., Lin Y. Lingshuiol, a novel polyhydroxyl compound with strongly cytotoxic activity from the marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:3117–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang X., Zhao D., Guo Y., Wu H., Trivellone E., Cimino G. Lingshuiols A and B, two new polyhydroxy compounds from the Chinese marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:5501–5504. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.05.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Washida K., Koyama T., Yamada K., Kita M., Uemura D. Karatungiols A and B, two novel antimicrobial polyol compounds, from the symbiotic marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:2521–2525. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.02.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morsy N., Houdai T., Matsuoka S., Matsumori N., Adachi S., Oishi T., Murata M., Iwashita T., Fujita T. Structures of new amphidinols with truncated polyhydroxyl chain and their membrane-permeabilizing activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:6548–6554. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang S., Kuo C., Lin Y., Chen Y., Lu C. Carteraol E, a potent polyhydroxyl ichthyotoxin from the dinoflagellate Amphidinium carterae. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:2512–2515. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.03.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanif N., Ohno O., Kitamura M., Yamada K., Uemura D. Symbiopolyol, a VCAM-1 inhibitor from a symbiotic dinoflagellate of the jellyfish Mastigias papua. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1318–1322. doi: 10.1021/np100221k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inuzuka T., Yamamoto Y., Yamada K., Uemura D. Amdigenol A, a long carbon-backbone polyol compound, produced by the marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:239–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.11.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inuzuka T., Yamada K., Uemura D. Amdigenols E and G, long carbon-chain polyol compounds, isolated from the marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:6319–6323. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.09.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satake M., Cornelio K., Hanashima S., Malabed R., Murata M., Matsumori N., Zhang H., Hayashi F., Mori S., Kim J.S., et al. Structures of the largest amphidinol homologues from the dinoflagellate Amphidinium carterae and structure-activity relationships. J. Nat. Prod. 2017;80:2883–2888. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martínez K.A., Lauritano C., Druka D., Romano G., Grohmann T., Jaspars M., Martín J., Díaz C., Cautain B., de la Cruz M., et al. Amphidinol 22, a new cytotoxic and antifungal amphidinol from the dinoflagellate Amphidinium carterae. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17:385. doi: 10.3390/md17070385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Wagoner R.M., Deeds J.R., Satake M., Ribeiro A.A., Place A.R., Wright J.L.C. Isolation and characterization of karlotoxin 1, a new amphipathic toxin from Karlodinium veneficum. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:6457–6461. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.08.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng J., Place A.R., Yoshida W., Anklin C., Hamann M.T. Structure and absolute configuration of karlotoxin-2, an ichthyotoxin from the marine dinoflagellate Karlodinium veneficum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3277–3279. doi: 10.1021/ja9091853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Wagoner R.M., Deeds J.R., Tatters A.O., Place A.R., Tomas C.R., Wright J.L.C. Structure and relative potency of several karlotoxins from Karlodinium veneficum. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1360–1365. doi: 10.1021/np100158r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waters A.L., Oh J., Place A.R., Hamann M.T. Stereochemical studies of the karlotoxin class using NMR spectroscopy and DP4 chemical-shift analysis: Insights into their mechanism of action. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:1–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai P., He S., Zhou C., Place A.R., Had S., Ding L., Chen H., Jiang Y., Guo C., Xu Y., et al. Two new karlotoxins found in Karlodinium veneficum (strain GM2) from the East China Sea. Harm. Algae. 2016;58:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen S.A., Binzer S.B., Hoeck C., Meier S., de Medeiros L.S., Andersen N.G., Place A., Nielsen K.F., Hansen P.J., Larsen T.O. Karmitoxin: An amine-containing polyhydroxy-polyene toxin from the marine dinoflagellate Karlodinium armiger. J. Nat. Prod. 2017;80:1287–1293. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espiritu R.A., Matsumori N., Tsuda M., Murata M. Direct and stereospecific interaction of amphidinol 3 with sterol in lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2014;53:3287–3293. doi: 10.1021/bi5002932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang B.S., Yoon E.Y., Jeong E.J., Park J., Kim E.-H., Rho J.-R. Determination of the absolute configuration of polyhydroxy compound ostreol B isolated from the dinoflagellate Ostreopsis cf. ovate. J. Org. Chem. 2018;83:194–202. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W.S., Yan R.J., Yu Y., Shi Z., Mándi A., Shen L., Kurtán T., Wu J. Determination of the absolute configuration of super-carbon-chain compounds by a combined chemical, spectroscopic, and computational approach: Gibbosols A and B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:13028–13036. doi: 10.1002/anie.202004358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamamoto Y., Tachibana K., Holland P.T., Shi F., Beuzenberg V., Itoh Y., Satake M. Brevisulcenal-F: A polycyclic ether toxin associated with massive fish-kills in New Zealand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4963–4968. doi: 10.1021/ja212116q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumori N., Kaneno D., Murata M., Nakamura H., Tachibana K. Stereochemical determination of acyclic structures based on carbon-proton spin-coupling constants. A method of configuration analysis for natural products. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:866–876. doi: 10.1021/jo981810k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bifulco G., Dambruoso P., Gomez-Paloma L., Riccio R. Determination of relative configuration in organic compounds by NMR spectroscopy and computational methods. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:3744–3779. doi: 10.1021/cr030733c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohtani I., Kusumi T., Kashman Y., Kakisawa H. High-field FT NMR application of Mosher’s method. The absolute configurations of marine terpenoids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4092–4096. doi: 10.1021/ja00011a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Riccardis F., Minale L., Riccio R., Giovannitti B., Iorrizi M., Debitus C. Phosphated and sulphated marine polyhydroxylated steroids from the starfish Tremaster novaecaledonìae. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1993;123:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finamore E., Minale L., Riccio R., Rinaldo G., Zollo F. Novel marine polyhydroxylated steroids from the starfish Myxoderma platyacanthum. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:1146–1153. doi: 10.1021/jo00003a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higashibayashi S., Czechtizky W., Kobayashi Y., Kishi Y. Universal NMR databases for contiguous polyols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14379–14393. doi: 10.1021/ja0375481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seike H., Ghosh I., Kishi Y. Attempts to assemble a universal NMR database without synthesis of NMR database compounds. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3861–3864. doi: 10.1021/ol061580t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preiss D.J., Sattar N. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1: A viable therapeutic target for atherosclerosis? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007;61:697–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiao H.L., Zhang Q., Lin Y.B., Gao Y., Zhang P. The ovotransferrin-derived peptide IRW attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses. BioMed Res. Int. 2019:8676410. doi: 10.1155/2019/8676410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park J.-G., Ryu S.Y., Jung I.-H., Lee Y.-H., Kang K.J., Lee M.-R., Lee M.-N., Sonn S.K., Lee J.H., Lee H., et al. Evaluation of VCAM-1 antibodies as therapeutic agent for atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2013;226:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ling S., Nheu L., Komesaroff P.A. Cell adhesion molecules as pharmaceutical target in atherosclerosis. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2012;12:175–183. doi: 10.2174/138955712798995057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cutignano A., Nuzzo G., Sardo A., Fontana A. The missing piece in biosynthesis of amphidinols: First evidence of glycolate as a starter unit in new polyketides from Amphidinium carterae. Mar Drugs. 2017;15:157. doi: 10.3390/md15060157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Wagoner R.M., Satake M., Wright J.L.C. Polyketide biosynthesis in dinoflagellates: What makes it different? Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014;31:1101–1137. doi: 10.1039/C4NP00016A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng Y., Van Wagoner R.M., Misner I., Tomas C., Wright J.L.C. Structure and biosynthesis of amphidinol 17, a hemolytic compound from Amphidinium carterae. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:409–415. doi: 10.1021/np900616q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kellman R., Stüken A., Orr R.J.S., Svendsen H.M., Jakobsen K.S. Biosynthesis and molecular genetics of polyketides in marine dinoflagellates. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8:1011–1048. doi: 10.3390/md8041011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.