Summary

Geographically dispersed patients, inconsistent treatment tracking, and limited infrastructure slow research for many orphan diseases. We assess the feasibility of a patient-powered study design to overcome these challenges for Castleman disease, a rare hematologic disorder. Here, we report initial results from the ACCELERATE natural history registry. ACCELERATE includes a traditional physician-reported arm and a patient-powered arm, which enables patients to directly contribute medical data and biospecimens. This study design enables successful enrollment, with the 5-year minimum enrollment goal being met in 2 years. A median of 683 clinical, laboratory, and imaging data elements are captured per patient in the patient-powered arm compared with 37 in the physician-reported arm. These data reveal subgrouping characteristics, identify off-label treatments, support treatment guidelines, and are used in 17 clinical and translational studies. This feasibility study demonstrates that the direct-to-patient design is effective for collecting natural history data and biospecimens, tracking therapies, and providing critical research infrastructure.

Keywords: Castleman disease, orphan disease, patient-powered, direct-to-patient, natural history registry

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

Partnership with the patient community supports recruitment and results dissemination

A patient-powered design enables high enrollment from a rare disease population

Extensive clinical data reveal >40 off-label treatments used in Castleman disease

De-identified linkage with a biobank supports translational research discoveries

Pierson et al. describe the feasibility of a patient-powered natural history registry for studying Castleman disease. They pair a traditional registry with a patient-powered approach, in which patients self-enroll and data collection is centralized. Clinical insights support treatment guidelines, and de-identified linkage to a biobank enables translational discoveries.

Introduction

Approximately 300,000,000 individuals worldwide are affected by 1 of 7,000 rare diseases. Ninety-five percent of these diseases do not have an approved treatment; the identification of effective treatments for rare diseases therefore represents a major unmet medical need.1 Disease rarity, heterogeneity, fragmentation of data and biospecimens, and treatment variability present challenges to understanding the natural history of rare diseases and identifying new treatment strategies.2 Even when novel drug targets are identified, drug development in rare diseases is complicated by the high cost of research, long development times, and small number of patients accessible for clinical trials.3 Innovative strategies are urgently needed to understand rare disease biology and develop treatment options.

Although patient registries and longitudinal natural history studies can be powerful tools for collecting data and biospecimens, improving disease understanding, and identifying treatments in real-world settings, there are notable limitations. Traditional natural history studies require physician investigators at a select number of sites to enroll patients and extract clinical data into a central study database. This approach enables the extensive collection of high-quality data but restricts enrollment to patients seen only at the few study sites. Alternatively, patient registries typically involve direct patient self-enrollment and contribution of data into a central online study database. This approach enables efficient enrollment to yield a more statistically powered research study, but the quality and amount of data collected per patient are minimal. Innovative study designs are needed to leverage the available data to gain meaningful and clinically actionable insights for rare diseases.

Castleman disease (CD) describes a group of rare and poorly understood disorders that have suffered from the above challenges. All CD patients have lymphadenopathy, sharing some recurrent histologic alterations; however, there is substantial variability in the number of enlarged lymph node regions, symptomatology, and etiology.4 Unicentric CD (UCD) involves one region of enlarged lymph nodes and is usually asymptomatic.5 Multicentric CD (MCD) involves ≥2 regions of enlarged lymph nodes and more severe symptoms, including constitutional symptoms, systemic inflammation, cytopenias, and, in some cases, can be associated with life-threatening multi-organ dysfunction.5 MCD is subdivided based on etiology.6 Human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8)-associated MCD is a lymphoproliferative disorder marked by proliferating HHV-8-infected plasmablasts and associated expression of viral interleukin-6 (IL-6) caused by uncontrolled HHV-8 infection. Polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes (POEMS)-associated MCD is likely driven by a monoclonal plasma cell population,7,8 while idiopathic MCD (iMCD) has an unknown etiology.9 Worldwide CD incidence is unknown, but it is estimated that 6,500–7,600 patients are diagnosed in the United States each year, ∼1,500 of whom are iMCD,10 which is poorly understood. The underlying heterogeneity of the diseases complicates the understanding of their natural history and pathophysiology.

Treatment approaches and drug effectiveness vary by subtype and include surgical resection as well as many different off-label drug treatments. Only one drug has received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval to treat a subtype of CD. Siltuximab, a monoclonal antibody directed against human IL-6, is recommended as a first-line therapy for iMCD; however, 50%–66% of patients do not respond to treatment.8,11 Outcome data for off-label drugs recommended for second- and third-line therapies in iMCD are insufficient and the available results suggest limited efficacy.12 Investigation of existing treatments and identification of novel therapies is therefore urgently needed.12 Furthermore, treatment options for UCD, HHV-8-associated MCD, and POEMS-associated MCD have not previously been systematically collected, identified, and categorized; the real-world effectiveness of the many off-label treatments is unknown.

In 2013, we set out to overcome the aforementioned enrollment and data quality limitations by creating an innovative study design to advance the understanding of the natural history, pathogenesis, and real-world treatment response of CD. After the EMA imposed a post-approval measure to carry out a disease registry of patients on siltuximab or siltuximab-eligible, we partnered with the manufacturers of siltuximab (Janssen Pharmaceuticals through 2018 and EUSA Pharma 2019 to present) to build a registry that met both aims. We developed a prospective, international, observational, web-based natural history registry of pathology-confirmed CD of all subtypes that incorporates the elements of a patient registry with a longitudinal natural history study. The primary objective of the study, referred to as the ACCELERATE (Advancing Castleman Care with an Electronic Longitudinal Registry, E-Repository, and Treatment/Effectiveness research) natural history registry, is to collect real-world demographic, clinical, laboratory, and outcomes data on patients with CD.

Here, we report the methodology, feasibility, and initial results of this innovative hybrid approach. We sought to address the feasibility of this study design in regard to enrollment, site launch, data collection and entry, patient representation, and applicability to translational research. We demonstrate that this approach is capable of generating data to address the stated objectives and has been foundational to our clinical and translational CD research programs.

Results

Approach

ACCELERATE was established through a collaborative partnership between the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN), Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn). UPenn serves as the regulatory study sponsor, manages the central database, retains ownership of all study data, and supports study infrastructure. Janssen Pharmaceuticals served as the financial sponsor and provided advice in regard to large-scale study design, safety tracking, regulatory reports, and site management before transferring this role to EUSA Pharma. The financial sponsor does not participate in decisions related to study design, operations, or study execution. Before study launch, the CDCN engaged physicians, researchers, and patients to assist with the development of study questions and the online portal (http://www.cdcn.org/accelerate). Since the launch, the CDCN has led recruitment efforts directly to patients through social media, online forums, and direct outreach.

We designed a two-arm approach, consisting of the patient-powered arm (PPA), which operates out of UPenn, and the physician-directed arm (PDA), which operates out of nine sites in six European countries. In the PDA, all CD patients who are treated by a given site physician are approached for enrollment in the study, and the site physician confirms the existence of a CD pathology report to meet inclusion criteria. Patients provide written informed consent for the site study staff to extract their medical data into the research database and to collect excess lymph node tissue for use in ACCELERATE. The site physician or study staff complete the enrollment information, upload the CD pathology report, and review and extract the medical data, which is updated at each patient visit. The physician also assesses the responses to all treatment regimens.

In the PPA, CD patients of all subtypes are encouraged to directly enroll themselves via a web-based portal, in which they electronically provide consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization to the ACCELERATE Registry Team (ART), as well as demographic and preliminary diagnosis information. In contrast to most clinical research and due to the self-enrollment process, patients consent to participate before inclusion criteria are confirmed. Inclusion criteria are later confirmed when a pathology report suggestive of CD is obtained. After the patient consents to enrollment, the ART then contacts each institution that has provided the patient with CD-related care and requests comprehensive patient medical records and radiological images from the time of diagnosis. Existing excess tissue is also collected for use in ACCELERATE, and, optionally, for use in additional translational research studies. A trained data analyst manually reviews comprehensive medical records for each case and extracts all data elements into the central database. All data entry questions are reviewed weekly by the ART and the decisions are captured in a study manual. The analyst assesses the patient’s diagnosis subtype and response to all treatment regimens. Each case is then reviewed with the study’s principal investigator (PI). Internal auditing is performed on 10% of data extracted from a given patient record for ≥25% of all patient records entered in the PPA.

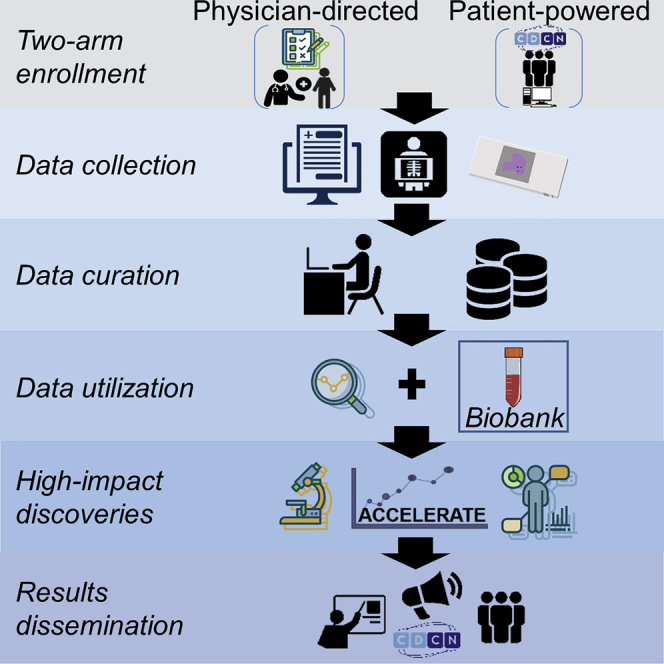

Retrospective data from the time of diagnosis through the time of enrollment are collected for all of the patients. Prospective patient reported outcome data collection and ongoing medical data extraction following enrollment are also performed. Study duration is planned for a minimum of 5 years. A diagram of the study design can be found in Figure 1 and further details can be found in the Method Details section.

Figure 1.

ACCELERATE Operations in the Patient-Powered Arm (PPA) and Physician-Directed Arm (PDA)

In the PPA, patients consent electronically and provide demographic data, at which point the ACCELERATE Registry Team acquires and enters the medical data into the database. Upon completion, treatment regimen responses are assessed and assigned, and the case is reviewed by the principal investigator. See also Table S1 for metrics on each step in the PPA process. In the PDA, physicians approach patients for enrollment, extract medical data, and assign treatment regimen responses. PDA cases do not require principal investigator review as they are assessed directly by the treating physician. All of the cases are then routed to the expert panel for review of the diagnosis. Patients in both arms have the opportunity to complete quarterly patient-reported outcome surveys.

Feasibility Assessment

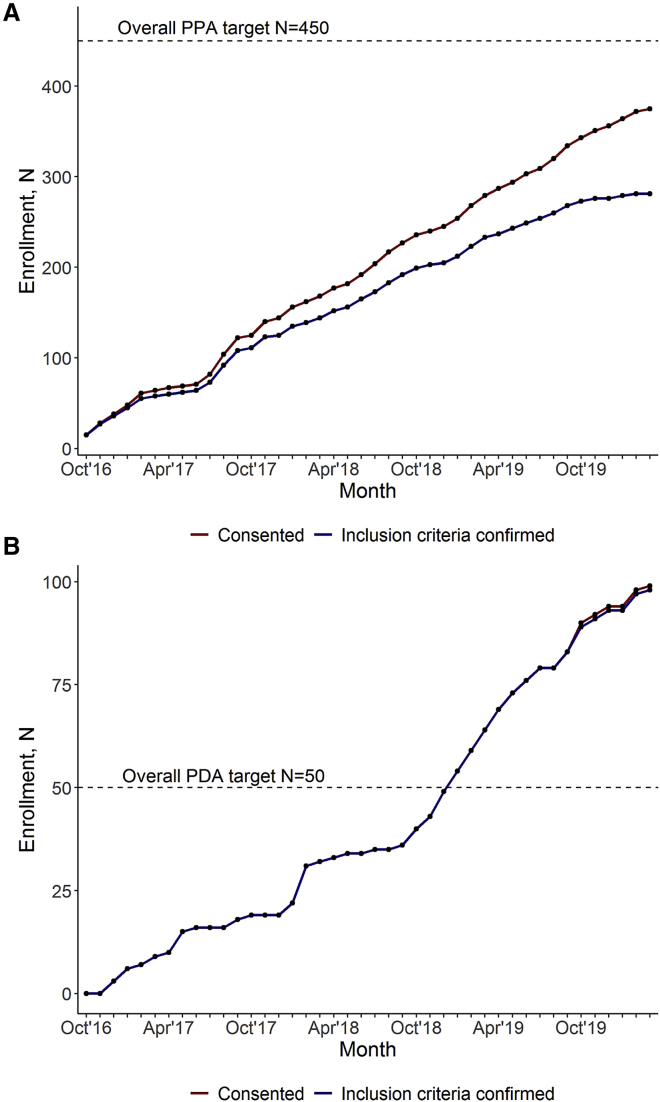

We sought to compare our enrollment rate with our targeted goals. Enrollment began in October 2016 for the PPA and in December 2016 for the PDA. To meet the minimum patient enrollment goal of 100 siltuximab-eligible or siltuximab-treated patients set by the EMA, we targeted an average enrollment of 1.67 iMCD patients per month between the PPA and PDA. The mean (SD) number of siltuximab-eligible patients enrolled per month was 3.8 (2.09), with 143 iMCD siltuximab-eligible patients enrolled to date. The 5-year EMA enrollment requirement was achieved in ∼2 years, primarily driven by PPA enrollment. We investigated whether the 9 PDA sites alone could have fulfilled the EMA requirement for 100 siltuximab-eligible patients. After 40 months of enrollment in the PDA, 44 iMCD patients have been enrolled. The rate of enrollment of iMCD patients from the time the first site was in place up to the present is 1.13 patients per month, with a marginally increased rate of 1.21 patients per month after all of the sites opened for enrollment (December 2018), which would have been short of the regulatory requirement.

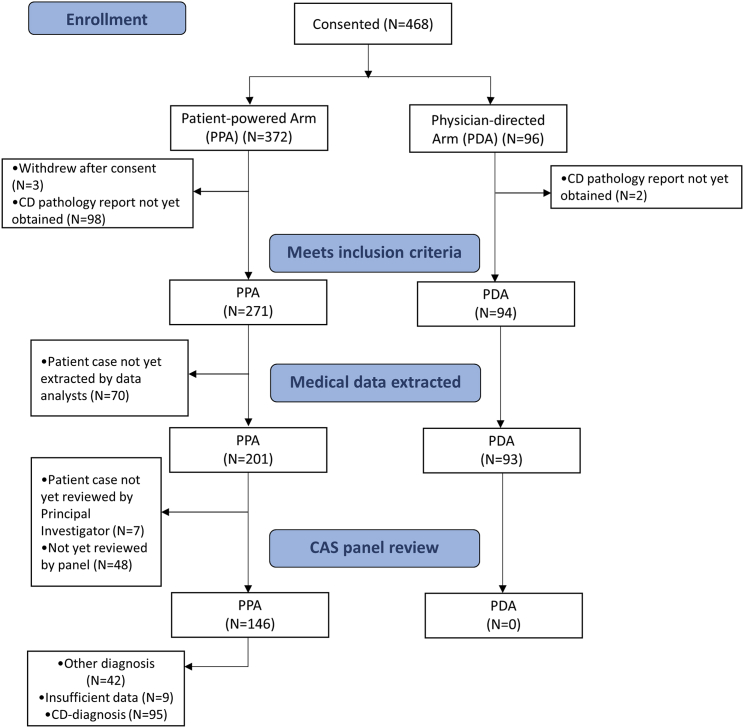

To meet our internal target of enrolling 500 CD patients of all subtypes over 5 years, we targeted an average enrollment of 8.3 CD patients per month between the PPA (goal: 7.5) and PDA (goal: 0.8). After 42 months of open enrollment, 468 patients had enrolled (PPA: 372, PDA: 96), and of those, 365 were confirmed to meet inclusion criteria (PPA: 271, PDA: 94) (Figures 2A and 2B). The mean (SD) number of CD patients enrolled per month was 9.1 (4.45) in the PPA and 2.5 (2.14) in the PDA, and the mean (SD) number of CD patients confirmed to meet inclusion criteria per month was 6.6 (4.34) in the PPA and 2.4 (2.05) in the PDA. Overall, enrollment has exceeded the internal target enrollment goal. An enrollment flowchart can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Enrollment Trends in ACCELERATE

(A) The PPA is on trend to meet its overall goal of enrolling n = 450 patients over 5 years. As of March 2020, n = 372 patients have consented in the PPA, with n = 271 meeting inclusion criteria.

(B) The PDA has successfully met and exceeded its goal to enroll n = 50 patients over 5 years. As of March 2020, n = 97 patients have consented in the PDA, with n = 94 meeting inclusion criteria.

Figure 3.

Study Enrollment Flow Diagram

Patients who receive a CD-diagnosis grade from the Certification and Access Subcommittee (CAS) will be included in select future analyses. PDA patients have not yet begun the CAS review process.

Data Representativeness

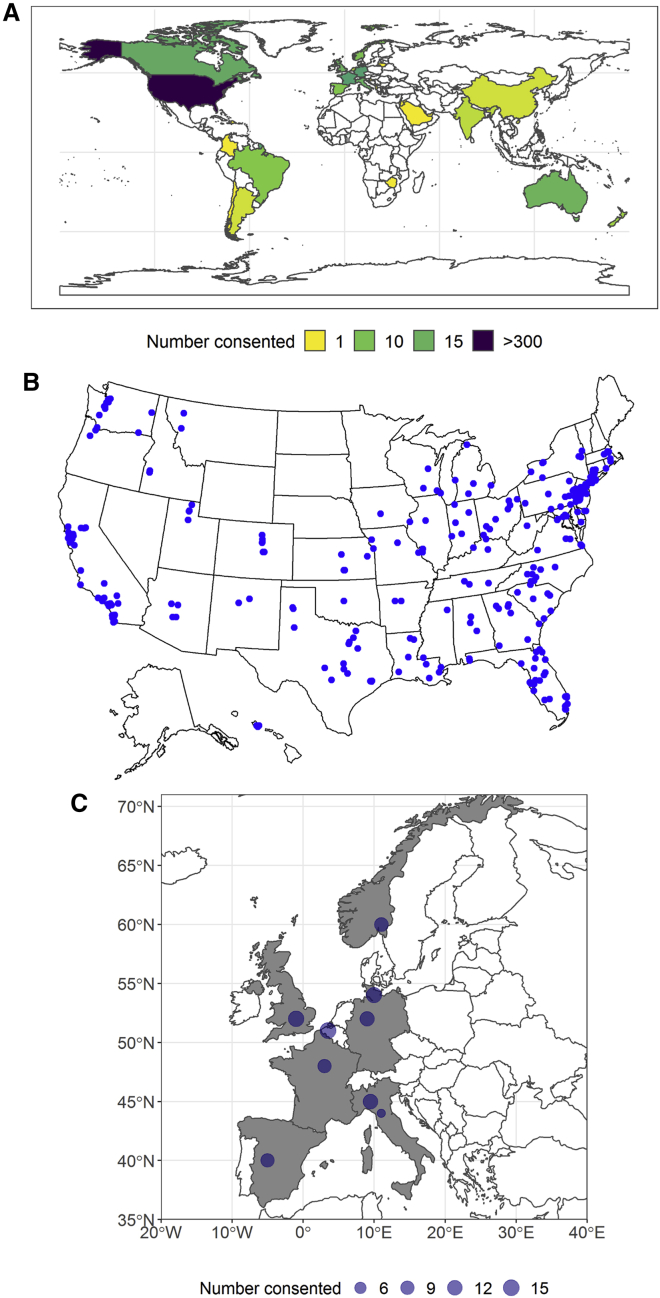

While ACCELERATE is not designed to assess disease epidemiology, we sought to assess the demographic representativeness of patients in ACCELERATE (Table 1). The relative frequencies of UCD to MCD (including iMCD, HHV8-associated MCD, POEMS-associated MCD, and HHV8 status-unknown MCD) in ACCELERATE are 37% and 63%. iMCD patients make up the largest subtype (39.1% overall, 47.3% PDA, and 36.3% PPA), with UCD being the second largest group (30.0% overall, 33.5% PDA, 28.2% PPA) in this study. Subtype composition overall is significantly different between the two arms (p < 0.0001). There is an overrepresentation of patients in the US and Europe in ACCELERATE (Figure 4A). In the PPA, enrolled patients who have had inclusion criteria confirmed come predominantly from the United States (n = 241, 89%), with another 5% from Canada (n = 13), 3% from Australia (n = 7), 1.5% from Brazil (n = 4), and <1% each from 6 additional countries (Figure 4B). In the PDA, patient enrollment is distributed throughout the 9 sites, with 25% located in Germany (n = 23) and France each (n = 24), 15% located each in Italy (n = 14) and the United Kingdom (n = 14), 11% in Norway (n = 10), and 10% in Spain (n = 9) (Figure 4C). There was no significant difference between arms in regard to racial composition, with the majority of patients (78.0%) being white (p = 0.56).

Table 1.

ACCELERATE Patient Demographics

| Overall, n = 365 |

PPA, n = 272 |

PDA, n = 93 |

p |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of UCD to MCD | 109:187 (37%:63%) | 76:129 (37%:63%) | 33:58 (36%:64%) | 1.00 |

| Overall composition | ||||

| Subtype, unknown | 55 (15.2) | 54 (20) | 1 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| UCD | 109 (30.0) | 76 (28.2) | 33 (33.5) | |

| HHV8-associated MCD | 23 (6.3) | 11 (4.1) | 12 (12.9) | |

| iMCD | 142 (39.1) | 98 (36.3) | 44 (47.3) | |

| HHV8-unknown MCD | 8 (2.2) | 8 (3.0) | 0 (0) | |

| POEMS-associated MCD | 12 (3.3) | 12 (4.4) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Other diagnosis | 14 (3.9) | 11 (4.1) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Racial composition, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 22 (6.1) | 19 (7.0) | 3 (3.2) | 0.5587 |

| Black | 23 (6.3) | 18 (6.7) | 5 (5.4) | |

| White | 283 (78.0) | 207 (76.7) | 76 (81.7) | |

| Other/unknown/refused to answer | 35 (9.6) | 26 (9.6) | 9 (9.7) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 201 (55.4) | 153 (56.7) | 48 (51.6) | 0.6668 |

| Male | 160 (44.1) | 115 (42.6) | 45 (48.4) | |

| Transgender | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | |

| Age at diagnosis, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 40.2 (16.3) | 38.8 (16.4) | 44.3 (15.3) | 0.0046 |

| Range | 1.0–80.0 | 1.0–80.0 | 2.0–78.0 | |

| Deceased patients | ||||

| N (%) | 10 (2.7) | 10 (100) | 0 | N/Aa |

| Patient-years mean (SD) | 2.8 (4.6) | 2.8 (4.6) | ||

Deceased patients not enrolled in the PDA.

Figure 4.

Geographic Trends in ACCELERATE

(A) Patients have consented from 27 different countries, with the majority from the United States (n = 303), Germany (n = 24), France (n = 24), Canada (n = 18), Italy (n = 16), the United Kingdom (n = 15), Australia (n = 14), Norway (n = 10), and Spain (n = 9).

(B) Enrollment within the United States is distributed across the country, with a cluster of patients near the Northeast.

(C) Enrollment from the 9 PDA sites demonstrates an even distribution.

The mean age at diagnosis in ACCELERATE is 40.2 (16.3) years (range: 1–80). We found that patients enrolled in the PPA are significantly younger (mean [SD] 38.8 [16.4]) than those enrolled in the PDA (mean [SD] 44.3 [15.3]) (p = 0.005). This observed age difference likely reflects the fact that children can enroll in the PPA but cannot enroll in the PDA. The two arms had a similar breakdown by gender, with females composing 55.1% (201/365) of the cohort overall (51.6% PDA, 56.7% PPA, p = 0.67). As the majority of patients self-enroll through the PPA, and PDA physicians cannot enroll deceased patients, we expect the proportion of CD patients who have died to be underrepresented in ACCELERATE. Deceased patients comprise 2.7% of the enrolled ACCELERATE cohort, with a mean (SD) 2.8 (4.6) years alive from diagnosis until death (range: 0–11). Although ACCELERATE is not suited to assess real-world epidemiology, a broad demographic cohort is represented.

Data Processing

We next assessed the efficiency of medical data collection and extraction in the PPA, for which the ART requests patient data from all of the treating institutions. For PPA patients, medical records, radiological images, and biospecimens are acquired from geographically dispersed patients and institutions. Of the 271 PPA patients meeting inclusion criteria, 59 self-uploaded their pathology report during enrollment (21.8%). For patients who did not self-upload their pathology report, median (interquartile range [IQR]) time from date of enrollment until receipt of report was 25 (3.0–67.0) days (range: 0–466) (Table S1). After receipt of the pathology report, the remaining time until receipt of comprehensive retrospective data was 145 (44.0–282.0) days. All requested medical records are combined into one readable electronic file for manual review and extraction. The median length of a patient’s medical record is 531 (274–1,041) pages, with the smallest record being 11 pages and the largest being 8,450 pages. The total number of pages received as of the data cutoff date is 216,851 pages.

As of March 2020, extraction has been started on 201 cases, and 194 of the 201 cases have been completed and reviewed by the PI. The median time from beginning data entry until completing a review with the PI is 44 (16.5–92.0) days, and a given full-time data analyst enters a median of 321 (243–437) medical record pages per week. Therefore, the median length of time from enrollment until case review with the PI is ∼7 months (Table S1).

Following the PI case review, each case undergoes Certification and Access Subcommittee (CAS) review and grading, which is performed to select optimal CD cases for certain analyses and publications. As of March 2020, the CAS has reviewed 146 of the 194 cases extracted into the database (75.3%) and assigned a grade that is insufficient for inclusion in select future analyses for 42 (28.8%) cases (Table S1). Overall, it takes ∼1 year from the time of patient enrollment until CAS review. Considering that this hybrid approach has not been done previously, these data suggest that it is feasible, given sufficient resources.

Data Quantity and Accuracy

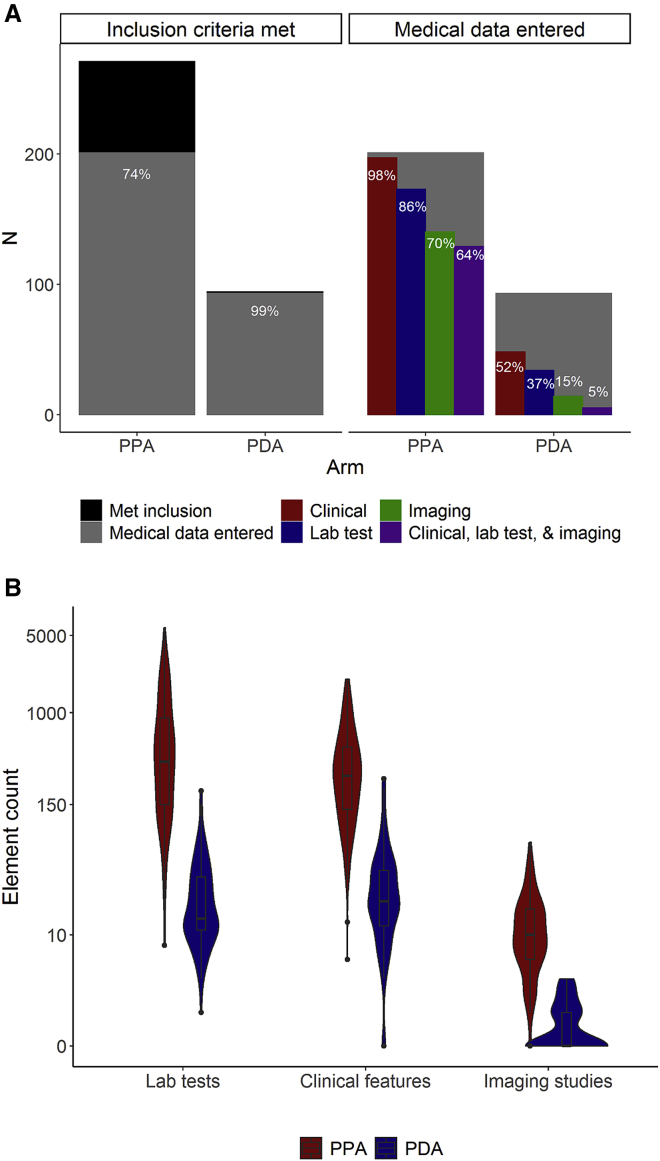

The ACCELERATE database is open-ended, which means that there is no limit to the number of times that an element (e.g., lab values, clinical symptoms) is captured, and the quantity of available data can vary greatly, so we examined the amount and type of data collected by each arm. Of the 365 patients confirmed to meet inclusion criteria, 294 (80.5%) have medical data entered in the database, including 93 of 94 patients (98.9%) in the PDA and 201 of 271 patients (74.2%) in the PPA (Figure 5A). A larger proportion of patients in the PPA (64.2%) have an adequate set of clinical, laboratory, and radiological data at the time of diagnosis than those in the PDA (5.4%) (Figure 5A). In addition, the amount of clinical, laboratory, and radiological data from diagnosis onward differs between arms. In the PPA, the median (IQR) number of assessed clinical symptoms entered per patient is 268.0 (134.0–486.0), and in the PDA, it is 20.0 (12.0–38.0). The median (IQR) number of laboratory tests entered per patient in the PPA is 358.5 (147.0–890.5) and in the PDA is 14.0 (11.0–33.0). The amount of radiological data, shown as the median (IQR) number of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or positron emission tomography (PET) scans, is 10.0 (6.0–17.0) in the PPA and 1.0 (1.0–2.0) in the PDA (Figure 5B). Overall, patients in the PPA have a median (IQR) of 683.0 (323.0–1334.0) clinical, laboratory, and imaging data elements entered, whereas patients in the PDA have 37.0 (19.0–69.0) clinical, laboratory, and imaging data elements entered.

Figure 5.

Data Entry Trends in the PPA and PDA

(A) The proportion of patients who meet inclusion criteria and have data entered into the study database for the PDA (99%) and PPA (75%), and the proportion of patients with medical data entered in each arm with clinical (98% PPA, 52% PDA), laboratory (86% PPA, 37% PDA), imaging (70% PPA, 15% PDA), and all 3 (clinical, lab test, and imaging data) in the database (64% PPA, 5% PDA).

(B) Violin plot showing the distribution (median, interquartile range, and range) of the number of required lab tests, positive or negatively assessed clinical features, and PET, PET/CT, CT, or MRI imaging studies entered in each arm.

Data are represented on a log scale.

Although a greater amount of data is available in the PPA, there is a larger percentage of treatment regimens with a documented response assessment in the PDA. Of the PDA patients, 44 (47.3%) have at least 1 regimen with a physician-assessed response, and of the total number (81) of assessed regimens, only 2 (2.5%) regimens lack response assessment. Comparatively, 194 of the PPA patients (96.5%) have at least 1 ART-assessed treatment regimen, and of the 654 assessed regimens, 118 (18.0%) regimens have an unknown outcome due to missing clinical, laboratory, and/or radiological data.

Given the large amount of data entered in the PPA, the potential for errors during data entry, and the fact that data are not entered by the patient’s physician, data audits are performed on PPA data. To date, 56 patients in the PPA have been audited with a 91.1% accuracy rate. Of the 8.9% of elements that were not accurately entered, 7.3% of those were not entered at all and 1.6% were entered incorrectly.

Data Utilization

Given that this study design has enabled sufficient enrollment of a representative cohort with a high quantity of data accurately sourced from medical records to meet our primary objective of collecting real-world CD data, we have begun addressing our secondary objectives (Figure 6). To identify patient subgroups, a study is under way to characterize the full spectrum of CD, specifically evaluating patients who do not clearly fall into the UCD or iMCD subgroups and do not carry an alternative or exclusionary diagnosis.13 Clinical data recorded in ACCELERATE are being analyzed along with corresponding CT and PET/CT images that were obtained through the ACCELERATE data collection process. To assess real-world response and safety profiles, an in-depth examination of treatments is also under way. Interestingly, we have identified 62 unique CD-treating drugs administered across patients of all CD subtypes in ACCELERATE, of which 46 have been administered to iMCD patients. Further analyses into these off-label treatments may be informative.

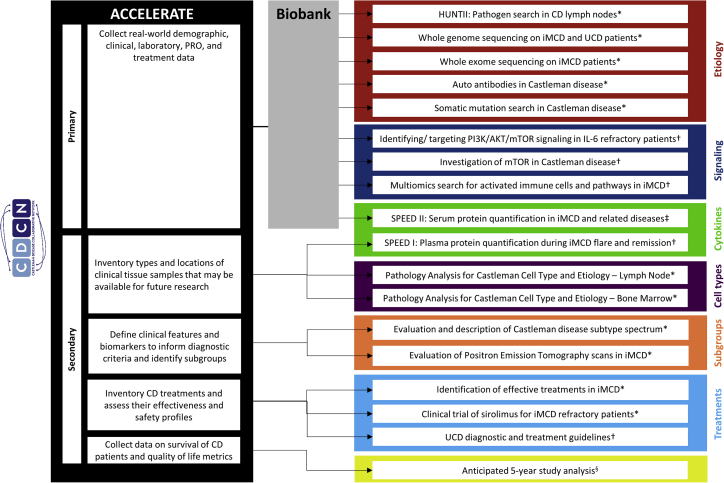

Figure 6.

Use of ACCELERATE Clinical Data and Tissue Samples in Translational Research

Key clinical data and tissue samples obtained through ACCELERATE have been used to further research CD etiology, signaling, cytokines, cell types, subgroups, and treatments. ACCELERATE clinical data have contributed to 5 published clinical and translational studies, 8 translational studies in progress, and 4 clinical studies in progress. §Planned research; ∗research in process; †published; ‡submitted for publication.

Furthermore, data extracted into ACCELERATE have served as critical correlative data for translational research performed on biospecimens around the world; patient data and tissue biospecimens collected from ACCELERATE have been used in published and ongoing translational and clinical studies that have led to treatment guidelines, critical biological insights, and the discovery of therapeutic targets (Figure 6).14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Overall, ACCELERATE patient data and tissue samples have enabled translational research studies that shed light on iMCD pathogenesis and will serve as an engine for future discovery.

Discussion

ACCELERATE maximizes enrollment and data collection through a hybrid strategy that combines an innovative patient-powered approach with a traditional physician-directed approach. The rarity and broad distribution have made it difficult to accrue large numbers of patients at specific sites through a traditional site-based approach alone. The patient-powered, centralized data entry approach used in this study has enabled us to enroll a large cohort of patients from a variety of demographics in a feasible time frame, collect extensive longitudinal medical data of high accuracy from primary sources, obtain biological materials, identify clinically actionable insights about CD natural history and treatment, and support critical translational research. This design builds upon aspects from prior efforts to remotely collect specific clinical data in progeria and clinically annotated samples in angiosarcoma.20,21

Several factors have likely contributed to the successful enrollment observed in the PPA and should be considered in future studies of rare diseases. Studies involving direct-online patient enrollment need to have a motivated patient population and a clear means for informing and engaging patients. The CDCN, which is one of three collaborative partners, facilitates patient involvement by providing information about ACCELERATE through its website, social media, and communications with physicians and patients, and subsequently disseminates research findings made through the registry to the patient community.22 Furthermore, in-person patient and physician meetings as well as online tools, such as GHDonline, RareConnect, CoDigital, and Facebook were used to engage physicians, researchers, and patients in ACCELERATE planning on research questions not previously addressed in the literature. Similar efforts to engage patients through qualitative interviews and research prioritization in other diseases have also been found to have a positive impact on the research and relationship between the patient community and research team.23,24 The Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation reported that in multiple myeloma, 93% of patients are willing to share data to help advance treatment research, and the foundation recently launched their own direct-to-patient web-based registry to collect longitudinal, clinical, genomic, and other data.25 Our experience collaborating with the CDCN demonstrates the success that can be achieved when patient networks partner on these kinds of studies.

Although the traditional site-based approach in this study has contributed to enrollment, study start-up time, differences in data collection, and resources required per site have limited the extent of that contribution. We selected sites in European countries, where we expected that rare disease patients would be more likely to be referred to fewer national reference centers. The nine sites were selected based on their historical patient populations and anticipated enrollment. However, the timeline required to obtain ethics committee approval, finalize site contracts, and train study staff delayed the start of patient enrollment. Also, differences in data privacy regulations and material transfer in European countries, as well as the limited geographical reach for each PDA site, likely contributed to the narrower enrollment capacity. From these data, a site-based approach can capably contribute to enrollment, but the limited geographical reach and extended time should be factored into the overall study goal.

There are also several differences between the PPA and PDA regarding data collection that should be both discussed and considered in the planning of future rare disease registry studies. A greater number of patients and more data per patient have been entered in the PPA than in the PDA. The lower amount of data entered for PDA patients is expected considering the resource-constrained PDA sites, where access to external medical records and available time to enter comprehensive data are limited compared to the PPA, where multiple full-time personnel have the capacity to obtain and enter all relevant data. In addition, the lower amount of data around the time of diagnosis in the PDA likely reflects the fact that the PDA sites are referral centers, so patients are diagnosed elsewhere and their data from diagnosis may not be available for entry into the database. Despite the higher number of patients and greater amount of data per patient in the PPA, a larger proportion of enrolled patients in the PDA are confirmed to meet inclusion criteria and have any amount of data entered in the database. Since patients in the PDA are enrolled by the site physician, these patients are clinically confirmed to meet inclusion criteria at the time of enrollment and patient data can be entered in a more timely manner. The smaller percentage of enrolled PPA patients meeting inclusion criteria (73%) reflects a lag between patient enrollment and receipt of pathology report, rather than a true difference in the proportion of patients meeting inclusion criteria compared to that in the PDA. Furthermore, the amount of time it takes to obtain comprehensive medical records in the PPA extends the time until medical data can be entered in the PPA, resulting in a reduced proportion of patients with entered data. In addition to enrollment and data collection differences, we also found differences in the assessment of treatment responses. Treating physicians at sites in the PDA can provide their own response assessments, whereas sufficient clinical, laboratory, and radiological data are required for an analyst to confidently assess response in the PPA. As such, adjustments will be warranted when data are combined for analyses.

Given the above differences between the two study arms, it is therefore important to consider the type and amount of data available and needed, time to obtain data, diagnosis assessment time, and resources available when designing a registry or natural history study. Studies of rare diseases in which a relatively large proportion of patients is treated by a small number of physicians and a relatively small amount of data need to be extracted per patient may benefit from the site-driven approach. However, studies of diseases with disbursed patient populations and many unknowns may benefit from the patient-powered approach, in which more patients can be included and more data can be collected and aggregated but per patient time to completion may be higher.

We set out to address a number of unanswered questions, such as an inventory of treatments and their real-world response. A systematic literature review published in 2016 reported a total of 18 different treatments in the 127 iMCD cases published in the literature. Publication biases, differences in response criteria, and sparse data presented with each case make it difficult to interpret the activity of these drugs in iMCD. In our preliminary review of iMCD treatments in ACCELERATE, we have identified 46 unique drugs given to iMCD patients and have extensive longitudinal clinical, radiological, and laboratory data to enable pragmatic treatment response evaluations. Given the mortality associated with iMCD and the large proportion of patients who do not respond to anti-IL6 treatment, the identification of other effective treatments is crucial. ACCELERATE has also served as a foundational element in the recent translational and clinical research discoveries in CD. The use of the global unique identifier (GUID) to enable de-identified linking of clinical data and samples in ACCELERATE with samples collected under other research protocols has enabled translational research and insights into disease pathogenesis that would not have been possible in isolation. In the past 3 years, data and tissue samples collected for ACCELERATE have been used in 5 published studies that have identified key cell types, signaling pathways, chemokines, therapeutic targets, and optimal treatment approaches.14, 15, 16, 17,19 The ACCELERATE model may also be helpful for other rare disease research studies.

Despite these successes, there are several limitations to the study design used in ACCELERATE. First, the differences in patient enrollment and data collection procedures between the PPA and PDA could introduce biases if combined. It is also possible that there are differences in clinical practice between physicians in the United States, where the largest proportion of PPA patients are located, and physicians in the PDA sites in Europe, which could explain some data entry differences. Second, online patient-driven registration may result in enrollment biases toward certain populations. In fact, the proportion of patients deceased by the time of follow-up is lower in ACCELERATE than in the published literature.26 This likely reflects a survival bias that is present in studies in which the patient must be alive. To address this potential bias, family members of deceased CD patients are invited to enroll these patients into the PPA. We found that the ratio of UCD to MCD patients in ACCELERATE (37% to 63%) is the inverse of that previously reported in the published literature (68% to 32%) and an insurance claims database (75% to 25%).10,26 This may reflect that the more symptomatic and less easily treated MCD patients may be more likely to seek resources and referrals and therefore be more likely to enroll in ACCELERATE than UCD patients. Third, the broad inclusion criteria could result in individuals who do not have CD enrolling and confounding the results. To address this, we assembled an expert panel to review key data for each patient. Although nearly all of these patients are being treated by a physician as though they have CD, a notable proportion of reviewed patients (42/146, 29%) did not achieve the minimum diagnostic grade to be included in some future analyses. Data from these cases will be useful for helping to differentiate the patients most consistent with CD from patients who may have CD or other overlapping diseases but do not meet all of the required criteria. Lastly, both study arms require extensive financial support. However, elements of ACCELERATE could be modified to reduce costs, such as stricter enrollment criteria and more targeted collection of data.

Here, we have described a design for a patient-powered natural history registry, leveraging online enrollment, which has proven to be foundational to our research program. This approach has overcome barriers intrinsic to traditional approaches, generated an overview of the natural history of CD, and facilitated discovery in the biology and clinical aspects of CD. Within 3.5 years, ACCELERATE assembled the largest cohort of CD patients reported to date who received 62 drug treatments, including 61 that are off-label. For a heterogeneous condition with few therapeutic options, the identification and evaluation of every potentially new therapeutic approach is critical to improving care and advancing clinical trials. Our results suggest that a patient-powered approach to natural history registry enrollment linked to biospecimens has been successful in CD and should be explored in other rare diseases.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| R 3.6.0 | R | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| R Studio 1.0 | RStudio | https://rstudio.com/ |

| SAS 9.4 | SAS | https://www.sas.com/en_us/home.html |

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, David Fajgenbaum (davidfa@pennmedicine.upenn.edu).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

The study datasets and code supporting the current study have not been deposited in a public repository because data collection is ongoing at the time of publication. They are available from the Lead Author upon request.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

The aim of the present study is to describe the feasibility and initial results from the ACCELERATE natural history registry. Inclusion criteria are broad and consist of a person of any age who has a pathology report suggestive of CD of any subtype and who can provide informed consent. Deceased patients can be enrolled by family members or site physicians per local regulations. There are no exclusion criteria. Detailed information on enrolled subjects, including accrual and sample size, is described in the Feasibility Assessment subsection of the Results section, as well as in Figures 2 and 3. A summary of demographic findings, including age at diagnosis, gender, and race, for all patients who meet study inclusion criteria is included in Table 1. The research protocol was approved by the UPenn Institutional Review Board and by the Ethics Committee at each respective European site (Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire de Lille, Lille, France; Hôpital Saint-Louis, Paris, France; Infektionsmedizinisches Centrum Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany; University of Münster, Münster, Germany; King’s College London, UK; Hospital Ramón Y Cajal, Madrid, Spain; Università degli Studi di Torino, Torino, Italy; Università di Bologna, Bologna, Italy; Oslo Universitetssykehus, Oslo, Norway). All subjects included in this study have provided their informed consent.

Method Details

Data collection

Once enrolled, patients are assigned a GUID, a unique computer-generated alphanumeric code, which is generated through software provided by the National Institutes of Health. The GUID enables de-identified linking of patient clinical data with translational research studies that use patient blood and/or tissue samples collected under separate research protocols. A complete listing of data elements collected in the registry for each patient at multiple time points can be found in Table S2. In addition, the European Quality of Life −5 dimensions, Multicentric Castleman Disease Symptom Scale, and a self-reported flare form are optionally completed by patients on a quarterly basis. See the Approach subsection of the Results for detailed information on the data collection approach in the PDA and PPA.

Treatment regimen and response assessment

Medical and surgical treatments used to treat CD are captured. Treatment combinations, termed regimens herein, are then defined based on the timing of initiation of different treatments. In the PDA, site physicians assess the patient’s clinical and lymph node response to a given regimen according to defined criteria (Table S3). In the PPA, physicians are not involved in providing or assessing data and physician-assessed responses are not consistently or systematically recorded in the medical record, so a response criterion was established according to the change in the proportion of abnormal minor diagnostic criteria between the initiation of a regimen and the time of greatest improvement (Table S4).8

Study Management and Oversight

The minimum patient enrollment goal for the first five years was 100 siltuximab-eligible (iMCD) patients across both arms in order to meet the EMA post approval measure. The internal target enrollment goal for the study was 500 CD patients across both arms (estimated 450 PPA and 50 PDA) over 5 years. Oversight of the ACCELERATE Registry is provided by two independent committees. The CAS, composed of 7 CD experts including 4 clinicians and 3 pathologists, is responsible for categorizing diagnoses, grading the likelihood of each patient’s diagnosis with CD, and granting access to ACCELERATE data to outside researchers. The CAS is assigned approximately 20 cases quarterly to review and grade. Cases are presented with available demographic and diagnostic information, including clinical features, radiological scans, and biomarkers within ± 90 days of diagnosis, as well as a scanned hematoxylin and eosin stained lymph node slide and other immunohistochemistry as available. CAS members grade each case independently and then meet to assign a consensus grade from 1 (least likely CD diagnosis) to 5 (most likely CD diagnosis). All cases that meet study inclusion criteria have been suspected of having CD and may be included in analyses; CAS grades are used to select optimal cases for certain analyses and publications. The ACCELERATE Steering Committee (ASC) is responsible for overseeing the operations, enrollment status, data accuracy, and safety data associated with the study. It is composed of three members each from CDCN, University of Pennsylvania, and EUSA Pharma (formerly Janssen Pharmaceuticals); two representatives from the patient and patient loved-one community are currently included among the 9 ASC members. The ASC meets regularly to review reports from the database and to address any relevant issues with the data.

Multiple mechanisms are in place to review and ensure data accuracy. First, a medical review report is generated and reviewed by the Principal Investigator and a member of the medical affairs division at the financial sponsor every 6 months to identify concerning data points relating to diagnosis, lab values, and safety events. Additionally, the database is queried regularly for potential inaccuracies including: missing data points (e.g., no information provided for a given clinical feature on a given form), duplicate data points (e.g., multiple entries of same drug treatment), out-of-range laboratory values, inconsistent data points (e.g., CT identifying multiple regions of enlarged lymph nodes but patient identified as unicentric subtype), missing treatment regimens, and additional ad hoc queries. A line listing of all queries is prepared and sent to the data analyst (PPA) or site (PDA) for reconciliation with the source documents. Queries are then reconciled, and line listings are returned with an indicated resolution, and all documentation is retained for reference.

The ACCELERATE registry meets all applicable data protection laws, including General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), HIPAA, and Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA). When the Regulation EU 2016/679 on Personal Data (i.e., GDPR) became fully effective in May 2018, patients enrolled in countries located in the European Economic Area (EEA) were provided with an informed consent addendum detailing their rights under GDPR and study compliance with GDPR, and the informed consent in each country was amended to address GDPR regulations after May 2018. Both the sponsor (UPenn) and the individual sites are considered “data controllers” and ensure that all data collected are processed in accordance with the law. In the PDA (i.e., sites located in EEA), all data elements that contain personally identifying information are collected, processed, and maintained at the site and visible only to the site physician and site study staff; data extracted into the database contains no personally identifying information. In the PPA, data elements that contain personally identifying information are provided by the patient at the time of enrollment and are visible only to study staff with appropriate database credentials. The registry platform is powered by Pulse Infoframe, which is compliant with HIPAA, PHIPA, and GDPR. All analyses performed on the data will be performed on de-identified data only.

Lastly, as outlined in the contractual agreement, ownership of the data and operational conduct of the study, with regards to collection and management of data, remain with UPenn. In the event that UPenn is no longer able to procure funding to maintain the registry, ownership of the data and study management will be turned over to the CDCN, which will make arrangements to fund and preserve the registry. Data is shared with EUSA Pharma (formerly Janssen Pharmaceuticals) for the purpose of performing regulatory submissions to Regulatory Authorities in connection with the PAM.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Data reported herein were collected from October 2016 through March 2020. Summary statistics were tabulated, and Pearson Chi-Square, Fisher's exact, or Student’s t test comparisons were performed where appropriate. Categorical data are presented as frequency (%), and continuous data are reported as median [IQR] unless otherwise stated. Data were prepared using SAS v9.4, R v3.6, and R Studio v1.0.

Additional Resources

More information on this study can be found at http://www.cdcn.org/accelerate. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02817997

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the volunteers for the CDCN who have supported this research, including Mary Zuccato, Patty Prazenica, Colin Smith, Greg Pacheco, Michael Stief, Kevin Silk, Chris Nabel, Sean Craig, Andrew Towne, Aleksas Juskys, and Helen Partridge. We wish to thank Dustin Shilling for contributions to the implementation of this study. We wish to thank Shawnee Bernstein, Nathan Hersh, Gerard Hoeltzel, and Jeremy Zuckerberg for their contributions to this study. We wish to thank Mary Guilfoyle, Martin Lukac, Jeff Faris, Ginneh Earle, Carlos Appiani, and Craig Tendler for their contributions to the design of the study and Reena Koodathil for facilitating many discussions relating to this research. We wish to thank Karan Kanhai and Rabecka Martin for their support of this research. We wish to thank Femida Gwadry-Sridhar, John Schaap, Ali Hamou, and other members of Pulse Infoframe, who built and supported the database. This study was funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals through 2018 and EUSA Pharma through the present.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.F., E.J., T.S.U., G.S., F.v.R., A.C., M.L., C.C., R.J., A.R., J.R., B.J., and K.E.-J.; Methodology, D.C.F., E.J., T.S.U., G.S., F.v.R., A.C., M.L., C.C., and R.J.; Formal Analysis, S.K.P.; Investigation, D.C.F., S.K.P., E.J., T.S.U., G.S., J.S.K., K.F., J.Z., E.H., E.N., F.A., A.L., F.v.R., A.C., M.L., C.C., M.S., E.O., L.A., C.H., L.T., J.L.P., S.F., P.L.Z., A.F., A.M.G., V.P., and M.-A.T.; Data Curation, S.K.P.; Writing – Original Draft, S.K.P. and D.C.F.; Writing – Review & Editing, D.C.F., S.K.P., E.J., T.S.U., J.S.K., A.L., F.v.R., A.C., M.L., C.C., A.F., A.M.G., V.P., and M.-A.T.; Visualization, S.K.P.; Supervision, D.C.F., E.J., T.S.U., G.S., F.v.R., A.C., M.L., C.C., J.R., B.J., K.E.-J., and M.R.; Project Administration, D.C.F.; Funding Acquisition, D.C.F., R.J., and A.R.

Declaration of Interests

A.L. reports employment and equity ownership from BridgeBio Pharma. A.R. reports consultancy to LabCorp and Consonance Capital, board member of Safeguard Biosystems, and member of academic advisory council to AMN. S.F. reports consultancy, advisory board membership, research funding, and speakers’ honoraria from Janssen Pharmaceuticals; consultancy, advisory board membership, and speakers’ honoraria from EUSA Pharma; advisory board membership in Clinigen; speakers’ honoraria from Servier; and research funding from Gilead. P.L.Z. reports consultancy to Verastem, MSD, EUSA Pharma, and Sanofi; speakers’ bureau of Verastem, Celltrion, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, BMS, Servier, MSD, Immune Design, Celgene, Portola, Roche, EUSA Pharma, and Kyowa Kirin; advisory board membership in Verastem, Celltrion, Gilead, and Janssen-Cilag, BMS, Servier, Sandoz, MSD, Immune Design, Celgene, Portola, Roche, EUSA Pharma, Kyowa Kirin, and Sanofi. L.T. reports advisory board membership in EUSA Pharma. C.C. reports consultancy to EUSA Pharma. E.O. reports advisory board membership in and consultancy to EUSA Pharma. G.S. reports speakers’ bureau involvement with Takeda, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Foundation Medicine, and EUSA Pharma. T.S.U. reports research support from Roche and Celgene and receives study drug for a clinical trial from Merck. F.v.R. reports a consultancy relationship with Takeda, Sanofi Genzyme, EUSA Pharma, Adicet Bio, Kite Pharma, and Karyopharm Therapeutics. D.C.F. reports research funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals (former financial sponsor) and EUSA Pharma (current financial sponsor) for the ACCELERATE Natural History Registry, donation of study drug from Pfizer for NCT03933904, and a provisional patent application filed by the University of Pennsylvania for Methods of Treating Idiopathic Multicentric Castleman disease with JAK1/2 inhibition (62/989,437). All of the other authors report no competing interests.

Published: December 22, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100158.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Global Genes. Rare facts. https://globalgenes.org/rare-facts/.

- 2.Kempf L., Goldsmith J.C., Temple R. Challenges of developing and conducting clinical trials in rare disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2018;176:773–783. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufmann P., Pariser A.R., Austin C. From scientific discovery to treatments for rare diseases - the view from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences - Office of Rare Diseases Research. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018;13:196. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0936-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dispenzieri A., Armitage J.O., Loe M.J., Geyer S.M., Allred J., Camoriano J.K., Menke D.M., Weisenburger D.D., Ristow K., Dogan A., Habermann T.M. The clinical spectrum of Castleman’s disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2012;87:997–1002. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fajgenbaum D.C., Shilling D. Castleman Disease Pathogenesis. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 2018;32:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fajgenbaum D.C., van Rhee F., Nabel C.S. HHV-8-negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis, and therapy. Blood. 2014;123:2924–2933. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-545087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dispenzieri A. POEMS syndrome and Castleman’s disease. In: Zimmerman T.M., Kumar S.K., editors. Biology and Management of Unusual Plasma Cell Dyscrasias. Springer; 2016. pp. 41–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fajgenbaum D.C., Uldrick T.S., Bagg A., Frank D., Wu D., Srkalovic G., Simpson D., Liu A.Y., Menke D., Chandrakasan S. International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria for HHV-8-negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2017;129:1646–1657. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-10-746933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fajgenbaum D.C. Novel insights and therapeutic approaches in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2018;132:2323–2330. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-05-848671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munshi N., Mehra M., van de Velde H., Desai A., Potluri R., Vermeulen J. Use of a claims database to characterize and estimate the incidence rate for Castleman disease. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2015;56:1252–1260. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.953145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Rhee F., Wong R.S., Munshi N., Rossi J.F., Ke X.Y., Fosså A., Simpson D., Capra M., Liu T., Hsieh R.K. Siltuximab for multicentric Castleman’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:966–974. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Rhee F., Voorhees P., Dispenzieri A., Fosså A., Srkalovic G., Ide M., Munshi N., Schey S., Streetly M., Pierson S.K. International, evidence-based consensus treatment guidelines for idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2018;132:2115–2124. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-862334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khor J., Pierson S.K., Powers V., Tamakloe M.-A., Gorzewski A., Floess K., Ziglar J., Haljasmaa E., Ren Y., Casper C. Castleman Disease Spectrum. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38(15 Suppl) 8548–8548. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fajgenbaum D.C., Langan R.-A., Japp A.S., Partridge H.L., Pierson S.K., Singh A., Arenas D.J., Ruth J.R., Nabel C.S., Stone K. Identifying and targeting pathogenic PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in IL-6-blockade-refractory idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129:4451–4463. doi: 10.1172/JCI126091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arenas D.J., Floess K., Kobrin D., Pai R.L., Srkalovic M.B., Tamakloe M.A., Rasheed R., Ziglar J., Khor J., Parente S.A.T. Increased mTOR activation in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2020;135:1673–1684. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierson S.K., Stonestrom A.J., Shilling D., Ruth J., Nabel C.S., Singh A., Ren Y., Stone K., Li H., van Rhee F., Fajgenbaum D.C. Plasma proteomics identifies a ‘chemokine storm’ in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2018;93:902–912. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pai R.L., Japp A.S., Gonzalez M., Rasheed R.F., Okumura M., Arenas D., Pierson S.K., Powers V., Layman A.A.K., Kao C. Type I IFN response associated with mTOR activation in the TAFRO subtype of idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. JCI Insight. 2020;5:e135031. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.135031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castleman Disease Collaborative Network. Research Pipeline: Leading to Personalized Medicine. https://cdcn.org/physicians-researchers/research-pipeline/.

- 19.van Rhee F., Oksenhendler E., Srkalovic G., Voorhees P., Lim M., Dispenzieri A., Ide M., Parente S., Schey S. International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic and treatment guidelines for unicentric Castleman Disease. Blood Adv. 2020 doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Painter C.A., Jain E., Tomson B.N., Dunphy M., Stoddard R.E., Thomas B.S., Damon A.L., Shah S., Kim D., Gómez Tejeda Zañudo J. The Angiosarcoma Project: enabling genomic and clinical discoveries in a rare cancer through patient-partnered research. Nat. Med. 2020;26:181–187. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0749-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Progeria Research Foundation. International registry. https://www.progeriaresearch.org/international-registry-2/.

- 22.Fajgenbaum D.C., Ruth J.R., Kelleher D., Rubenstein A.H. The collaborative network approach: a new framework to accelerate Castleman’s disease and other rare disease research. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e150–e152. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodward L., Johnson S., Walle J.V., Beck J., Gasteyger C., Licht C., Ariceta G., aHUS Registry SAB An innovative and collaborative partnership between patients with rare disease and industry-supported registries: the Global aHUS Registry. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2016;11:154. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0537-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young K., Kaminstein D., Olivos A., Burroughs C., Castillo-Lee C., Kullman J., McAlear C., Shaw D.G., Sreih A., Casey G., Merkel P.A., Vasculitis Patient-Powered Research Network Patient involvement in medical research: what patients and physicians learn from each other. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019;14:21. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0969-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation. Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF) launches groundbreaking direct-to-patient registry. https://themmrf.org/2019/10/10/multiple-myeloma-research-foundation-mmrf-launches-groundbreaking-direct-to-patient-registry/.

- 26.Talat N., Schulte K.-M. Castleman’s disease: systematic analysis of 416 patients from the literature. Oncologist. 2011;16:1316–1324. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The study datasets and code supporting the current study have not been deposited in a public repository because data collection is ongoing at the time of publication. They are available from the Lead Author upon request.