Abstract

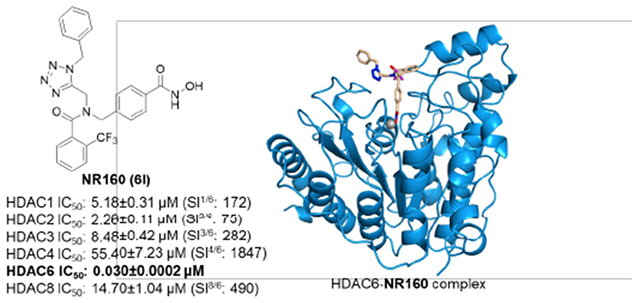

The histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) is an emerging target for the treatment of cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, inflammation, and other diseases. Here, we present the multicomponent synthesis and structure-activity relationships of a series of tetrazole-based HDAC6 inhibitors. We discovered the hit compound NR-160 by investigating the inhibition of recombinant HDAC enzymes and protein acetylation. A co-crystal structure of HDAC6 complexed with NR-160 disclosed that the steric complementarity of the bifurcated capping group of NR-160 to the L1 and L2 loop pockets may be responsible for its HDAC6-selective inhibition. While NR-160 displayed only low cytotoxicity as single-agent against leukemia cell lines, it augmented the apoptosis induction of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in combination experiments significantly. Furthermore, a combinatorial high throughput drug screen revealed significantly enhanced cytotoxicity when NR-160 was used in combination with epirubicin and daunorubicin. The synergistic effect in combination with bortezomib and anthracyclines highlights NR-160’s potential in combination therapies.

Keywords: Histone deacetylases, HDAC6, cancer, multicomponent reactions, leukemia

Table of Contents Graphic

INTRODUCTION

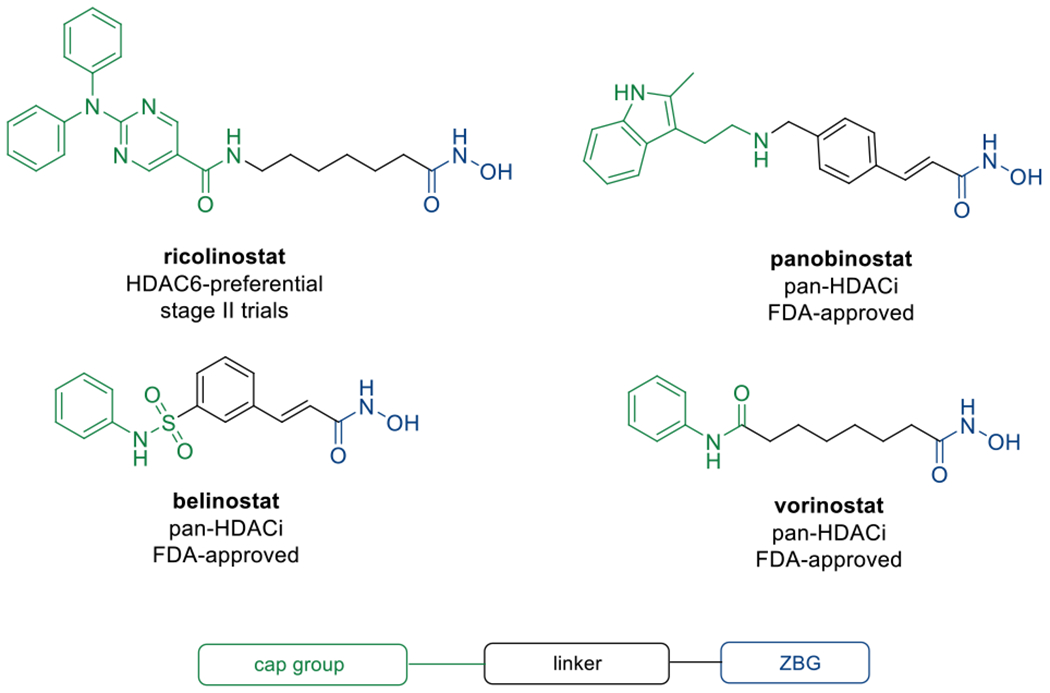

Controlling histone modifications using targeted epigenetic drugs has become an important alternative to non-selective chemotherapeutic agents in cancer therapy. Among other enzymes, histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) are crucial players in posttranslational histone modifications and therefore valuable drug targets.1 To date, eleven zinc-dependent HDAC isoforms have been identified.2 In accordance with their homology to yeast proteins, HDACs are subdivided into four classes: class I (HDACs 1, 2, 3 and 8), class IIa (HDACs 4, 5, 7 and 9), class IIb (HDAC6 and the polyamine deacetylase HDAC 10), and class IV (HDAC11).2,3 Class III consists of non-zinc-dependent sirtuins.2 The classic role of HDACs is to mediate gene expression by regulating histone acetylation levels through modifications of the chromatin structure.4 However, this interaction can only be observed for class I HDACs whereas other isoforms are involved in different pathways that contribute to the development of cancer and other diseases.4–6 The distinct shape of the active sites of all isoforms inspired the development of a well-established pharmacophore model comprising a cap group, a linker unit and a zinc-binding group, typically a hydroxamate, which is the basis for most HDAC inhibitors.4 In cancer therapy, unselective HDAC inhibitors, e. g. the FDA-approved drugs vorinostat (SAHA), panobinostat, belinostat (Figure 1) as well as the class I-selective natural product romidepsin, have been proven effective against haematological diseases while also causing severe adverse effects as a consequence of HDAC class I inhibition.6,7

Figure 1.

Selected HDAC inhibitors based on the established pharmacophore model.

To minimise off-target effects, the therapeutic potential of isoform selective inhibitors and particularly HDAC6 inhibitors (HDAC6i) is currently being investigated.4,7 Apart from α-tubulin, the substrate spectrum of HDAC6 includes Hsp90 and cortactin which makes it a crucial regulator of the cytoskeleton and a promising target for the treatment of rare and neurodegenerative diseases.8–11 Even though recent studies have demonstrated that HDAC6 inhibition alone exhibits no significant cytotoxicity,12,13 it is presumed to be a promising target for synergistic approaches in combination with other drugs, such as Hsp90 or proteasome inhibitors (PIs).14,15 The synergism between HDAC6i and PIs relies on the blockage of two major protein degradation pathways, the proteasome and aggresome.15 The hydrolysis of proteins into small oligopeptides mediated by the 20S proteasome core particle is the most important mechanism to prevent proteotoxic stress induced by accumulation of misfolded proteins.16 In the case of reduced proteasome function, protein degradation is assisted by HDAC6-mediated aggresome formation and simultaneous blockage of both targets induces apoptosis in fast-growing cells.14,15 This synergism has been widely investigated and led to the FDA-approval of the combination of panobinostat and the PI bortezomib (BTZ) against multiple myeloma while clinical trials using combinations of BTZ and the HDAC6-preferential drug candidate ricolinostat are ongoing. A recent approach towards HDAC6i application against haematological cancers led to the discovery that the compound MPT0G211 potentiates the cell cycle-arresting effect of the anthracycline-based intercalating agent doxorubicin in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell lines while the combined application of both compounds also appeared to increase apoptosis and reduce DNA repair-related doxorubicin resistance.17 In the same study, a combination of MPT0G211 and the mitotic inhibitor vincristine effectively disturbed the microtubule dynamics in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells, thus triggering apoptosis.17

In light of these initial results, the scope of selective HDAC6i as synergistic agents in cancer therapy is indeed promising and more detailed information on structural requirements might be helpful to fully exploit their therapeutic potential.

RESULTS

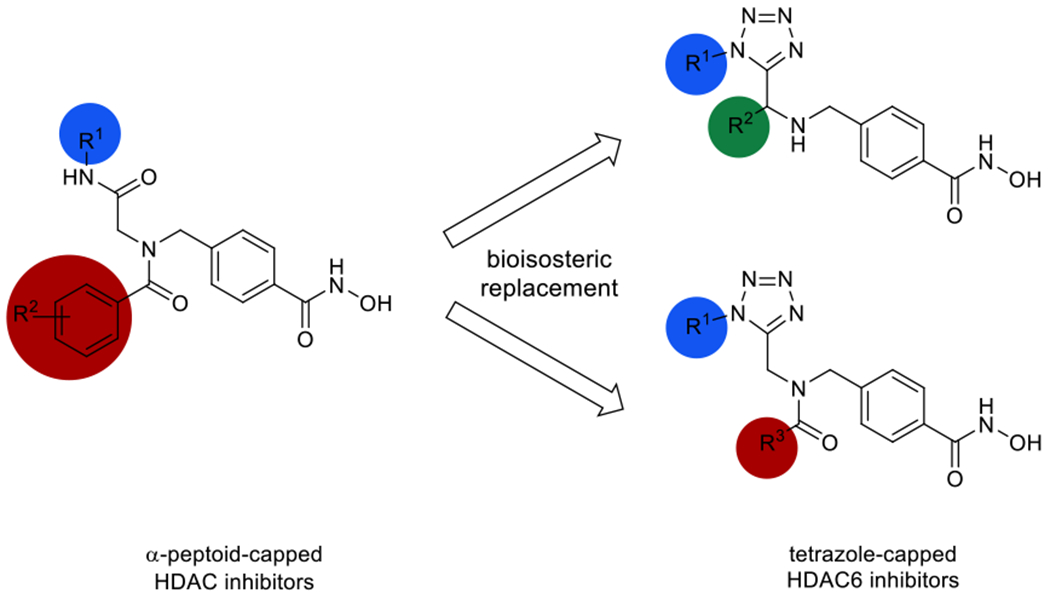

Design and synthesis of tetrazole-capped HDAC inhibitors.

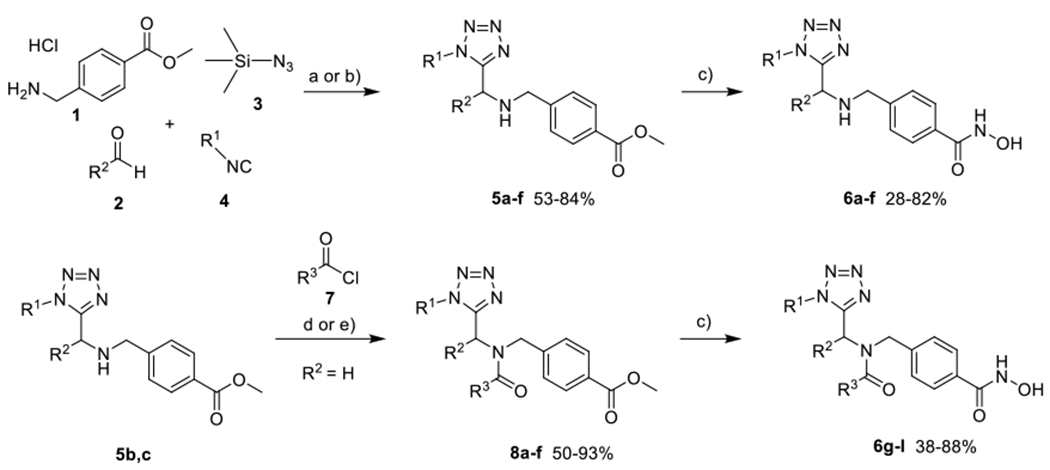

Following our previous work on peptoid-based HDAC6 inhibitors,18–20 we herein present the design and synthesis of a series of tetrazole-capped HDAC inhibitors. Based on recent results indicating a correlation between reduced flexibility and HDAC6 selectivity of the inhibitors,21 we decided to replace the amide unit in the cap group region by a bioisosteric tetrazole ring incorporated into differently shaped scaffolds (Scheme 1) in order to increase the rigidity of the compounds. Before attempting library synthesis, three model compounds were synthesised using a microwave-assisted Ugi-azide 4-component reaction starting from methyl 4-(aminomethyl)benzoate hydrochloride as the linker fragment, paraformaldehyde, trimethylsilyl azide to create the tetrazole ring, and different isocyanides to diversify the upper branch of the bifurcated capping group (5a-c; Scheme 2). In the next step, the resulting esters were treated with a mixture of aqueous hydroxylamine and sodium hydroxide to generate the corresponding hydroxamates 6a-c. Biochemical enzyme inhibition assays of the three prototypes 6a-c against HDAC isoforms 1 and 6 led us to discarding the tbutyl-derivative 6a (IC50 HDAC1: 8.24 μM; HDAC6: 0.330 μM). Instead, we focused on cyclohexyl-(IC50 HDAC1: 2.06 μM; HDAC6: 0.120 μM) and benzyl-analogues (IC50 HDAC1: 2.45 μM; HDAC6: 0.102 μM) as the most promising inhibitors with regards to inhibitory activity and HDAC6-selectivity. Following these initial results, a small library of branched inhibitors was created by varying the aldehyde component in the Ugi-reaction (5d-f) or by using in situ-made or commercial acyl chlorides for N-acylation of the formaldehyde-derived analogues (8a-f; Scheme 2). Subsequent aqueous hydroxylaminolysis, followed by precipitation from water afforded the corresponding hydroxamates (6d-l; Scheme 2) in high purities of at least 95%.

Scheme 1.

Design of tetrazole-capped selective HDAC6 inhibitors derived from α-peptoid-based HDACi.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of tetrazole-capped HDAC6i. a) Et3N, MeOH, microwave, 45 °C, 150 W, 30-120 min (imine formation), then 120-240 min (UA4CR); b) Et3N, MeOH, rt, 3 days; c) NaOH, H2NOH (50% in water), MeOH/DCM, 0 °C, 60-240 min; d) respective acyl chloride, Et3N, DCM, 0 °C to rt, 16 h; e) respective carboxylic acid, SOCl2, DCM, 0 °C, 30 min, then addition of 5 and Et3N, DCM, rt, 16 h.

HDAC inhibition.

HDAC inhibition assays of all compounds against HDAC isoforms 1 and 6 revealed potent inhibitory activities with a clear preference for HDAC6 (Table 1). It is striking that compounds 6d-f (selectivity indices (SI): 17-34) showed a similar selectivity profile as compounds 6g-j (SI: 11-50) while exhibiting lower inhibitory activity (IC50 HDAC6: 0.10-0.12 μM). Except for the unselective inhibitor 6k (IC50 HDAC6: 0.32 μM), all N-acylated compounds demonstrated potent HDAC6 inhibition in the low nanomolar concentration range (IC50 HDAC6: 0.03-0.08 μM). Comparison of compounds 6g (HDAC6 IC50: 0.07 μM, SI: 34) and 6h (HDAC6 IC50: 0.06 μM, SI: 50) further showed that residues in the 2-position of the benzamide group lead to an increase in both HDAC6 selectivity and inhibition while the benzyl-derivatives 6e (HDAC6 IC50: 0.10 μM, SI: 34) and 6i (HDAC6 IC50: 0.03 μM, SI: 41) are more potent and equally or slightly more selective than the cyclohexyl-capped compounds 6d (HDAC6 IC50: 0.12 μM, SI: 34) and 6g (HDAC6 IC50: 0.07 μM, SI: 34). Although most compounds only displayed moderate selectivities for HDAC6 (SI: 6-50), we were able to identify compound 6l bearing a trifluoromethyl group in the 2-position of the benzamide part of the cap as a very potent and selective HDAC6 inhibitor (HDAC6 IC50: 0.03 μM, SI: 173). Notably, 6l exceeds the HDAC6 selectivity of ricolinostat, HPOB, and nexturastat A and is nearly as selective as the well-established HDAC6 tool compound tubastatin A (IC50: 0.014 μM, SI: 178) in our biochemical assays.

Table 1.

IC50 of the tetrazole-capped HDACi 6a-f and vorinostat (SAHA) as control in comparison with ricolinostat (ACY-1215), nexturastat A, tubastatin A (Tub A), and HPOB against HDAC1 and HDAC6.

| Entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | HDAC1 IC50 [μM] |

HDAC6 IC50 [μM] |

SIa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6a | tert-Butyl | - | - | 8.24±0.07 | 0.33±0.01 | 25 |

| 6b | Bn | - | - | 2.45±0.22 | 0.10±0.01 | 25 |

| 6c | c-Hexyl | - | - | 2.06±0.33 | 0.12±0.01 | 17 |

| 6d | c-Hexyl | Ph | - | 4.06±0.02 | 0.12±0.01 | 34 |

| 6e | Bn | Ph | - | 3.37±0.01 | 0.10±0.01 | 34 |

| 6f | Bn | n-Butyl | - | 2.01±0.01 | 0.12±0.03 | 17 |

| 6g | c-Hexyl | - | Ph | 2.37±0.26 | 0.07±0.003 | 34 |

| 6h | c-Hexyl | - | 2-Me-Ph | 3.03±0.36 | 0.06±0.003 | 50 |

| 6i | Bn | - | Ph | 1.24±0.06 | 0.03±0.004 | 41 |

| 6j | Bn | - | 3,5-Me-Ph | 0.90±0.17 | 0.08±0.004 | 11 |

| 6k | Bn | - | 4-iPr-Ph | 1.78±0.16 | 0.32±0.06 | 6 |

| 6l | Bn | - | 2-CF3-Ph | 5.18±0.31 | 0.03±0.0002 | 173 |

| SAHA | - | - | - | 0.12±0.01 | 0.04±0.01 | 3 |

| ACY-1215 | - | - | - | 0.19±0.02 | 0.02±0.003 | 11 |

| Nexturastat A | - | - | - | 0.50±0.03 | 0.02±0.0001 | 24 |

| Tub Ab | - | - | - | 2.49±0.14 | 0.014±0.0006 | 178 |

| HPOBb | - | - | . | 2.10±0.23 | 0.085±0.009 | 25 |

Selectivity index (SI = IC50 (HDAC1)/IC50 (HDAC6)).

Data taken from reference 22.

Microsomal stability and HDAC6 selectivity of 6l.

Encouraged by its potent and selective HDAC6 inhibition, we decided to investigate the properties of the hit compound 6l in more detail. First, we determined the metabolic stability of 6l. Pleasingly, 6l demonstrated promising microsomal stability towards human (HLM, Clint: 30 μL/min/mg) and mouse liver microsomes (MLM, Clint: 26 μL/min/mg; Table S1, Supporting Information). Additional screenings confirmed the HDAC6 selectivity (Figure 2A) over all class I isoforms (HDAC2 IC50: 2.26 μM, SI: 75; HDAC3 IC50: 8.48, SI: 282; HDAC8 IC50: 14.70 μM, SI: 490) and indicated negligible inhibition of the class IIa isoform HDAC4 (IC50: 55.40 μM, SI: 1857). To examine the cellular selectivity of 6l for HDAC6, the acute myeloid leukemic (AML) cell line HL60 was treated for 24 h with two different concentrations of 6l and the clinical reference compound ricolinostat. Immunoblotting of the cellular lysates revealed that 6l treatment induced α-tubulin acetylation (ac-α-tubulin), which is a marker for HDAC6 inhibition (Figure 2B). The acetylation status of histone H3 (ac-H3) was unaffected after treatment, which was expected, as ac-H3 is a marker for the inhibition of class I HDACs. Together these results confirm the HDAC6 selectivity of compound 6l in the cellular environment.

Figure 2.

Functional specificity of 6l against HDAC6. (A) Inhibitory activities of compound 6l against HDAC isoforms 1-4, 6 and 8. (B) HL60 cells were treated for 24 hours with compound 6l and ricolinostat at the indicated concentration. Afterwards, cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-acetyl-α-tubulin, acetyl-histone H3, total α-tubulin, total histone H3. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Co-crystal structure of HDAC6 in complex with 6l.

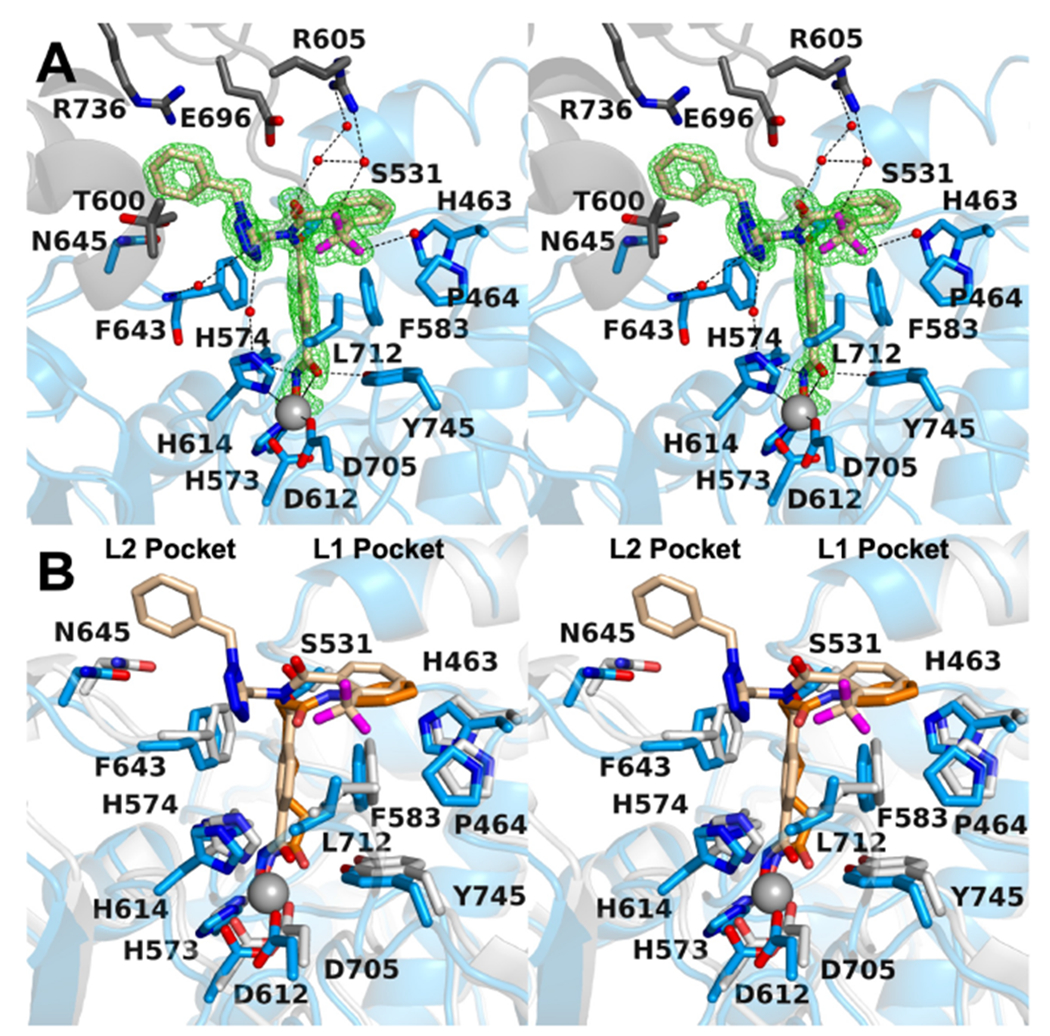

To elucidate the binding mode of 6l, an X-ray co-crystal structure of the catalytic domain 2 (CD2) of Danio rerio (zebrafish) HDAC6 complexed with 6l was determined. The 1.48 Å-resolution crystal structure of the zCD2–6l complex (Figure 3A) contains two virtually identical monomers in the asymmetric unit, and the r.m.s. deviation is 0.09 Å for 303 Cα atoms. Inhibitor binding does not cause any major conformational changes, and the r.m.s. deviation is 0.20 Å for 303 Cα atoms when compared with the structure of unliganded zCD2 (PDB 5EEM).23 Electron density for 6l bound in the active site of each monomer is very well-defined and reveals that the hydroxamate moiety of the inhibitor chelates the catalytic Zn2+ ion in bidentate fashion (Figure 3A). Overall, the coordination geometry of Zn2+ is pentacoordinate square pyramidal.

Figure 3.

(A) Polder omit map of the zCD2-6l complex (monomer A, contoured at 5.0σ) (PDB 6PYE). Atoms are color-coded as follows: C = light blue (zCD2 monomer A), dark gray (zCD2 symmetry mate), or wheat (inhibitor), N = blue, O = red, F = magenta, Zn2+ = gray sphere, and solvent = small red spheres. Metal coordination and hydrogen bond interactions are indicated by solid and dashed black lines, respectively. (B) Superposition of the zCD2-6l complex and the zCD2-SAHA complex (PDB 5EEI) illustrates how the bifurcated capping group of 6l makes interactions in both the L1 and L2 pockets, whereas the single capping group of SAHA makes interactions in only the L1 pocket. Atoms are color-coded as follows: C = light blue (protein, zCD2-6l complex), gray (protein, zCD2-SAHA complex), wheat (6l), or orange (SAHA), N = blue, O = red, F = magenta, Zn2+ = gray sphere, and solvent = small red spheres. Metal coordination and hydrogen bond interactions are indicated by solid and dashed black lines, respectively.

The ionized hydroxamate N–O− group of 6l coordinates to Zn2+ (average Zn2+---O distance = 1.9 Å) and accepts a hydrogen bond from H573, and the hydroxamate C=O coordinates to Zn2+ (average Zn2+---O distance = 2.5 Å) and accepts a hydrogen bond from Y745. The hydroxamate NH group donates a hydrogen bond to H574. A similar constellation of metal coordination and hydrogen bond interactions is observed for some but not all hydroxamate-based inhibitors bound in the active site of zCD2.21,24,25 6l contains two capping groups that branch out from the central benzylamine linker. This bifurcated capping group interacts with pockets defined by the L1 and L2 loops flanking the active site. The simultaneous binding of inhibitor capping groups in the L1 and L2 pockets has also been observed in a recently reported zCD2-inhibitor complex.26

The N-(4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)benzyl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide capping group binds in the L1 pocket. The capping group is complementary in shape to the contour of the L1 pocket, but it does not make any direct hydrogen bond interactions with protein residues. The trifluoromethyl group accepts a hydrogen bond from a nearby water molecule in monomer A (C–F---H2O distance = 3.2 Å); the corresponding hydrogen bond is absent in monomer B. A second C–F---H2O hydrogen bond is observed in both monomers, and this water molecule in turn accepts a hydrogen bond from R605 in a symmetry-related zCD2 molecule in the unit cell. The C–F group is a weak hydrogen bond acceptor,27,28 so these interactions are not expected to substantially contribute to enzyme-inhibitor affinity.

The N-(1-benzyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl moiety binds in the L2 pocket. Here, too, the capping group is complementary in shape to the contour of the pocket, but it does not make any direct hydrogen bond interactions with protein residues. The tetrazole moiety forms two water-mediated hydrogen bonds with the backbone NH group of F643 and side chain of H614. Interestingly, “gatekeeper” residue S531, located in the region between the L1 and L2 pockets, does not make any direct hydrogen bond interactions with 6l and adopts two alternate conformations. S531 accepts a hydrogen bond from the backbone NH group of acetyllysine when peptide substrates bind to zCD2.23 Since S531 has no equivalent in other HD AC isozymes, interactions with this residue could confer some measure of inhibitor selectivity for binding to HDAC6. The selectivity of 6l for HDAC6 is thus impressive and presumably results from other interactions, such as the steric complementarity of the bifurcated capping group as it occupies the L1 and L2 pockets. In comparison, pan-HDAC inhibitors such as SAHA typically bind with capping groups occupying just the L1 pocket (Figure 3B).

6l enhances the cytotoxicity induction of bortezomib, epirubicin and daunorubicin.

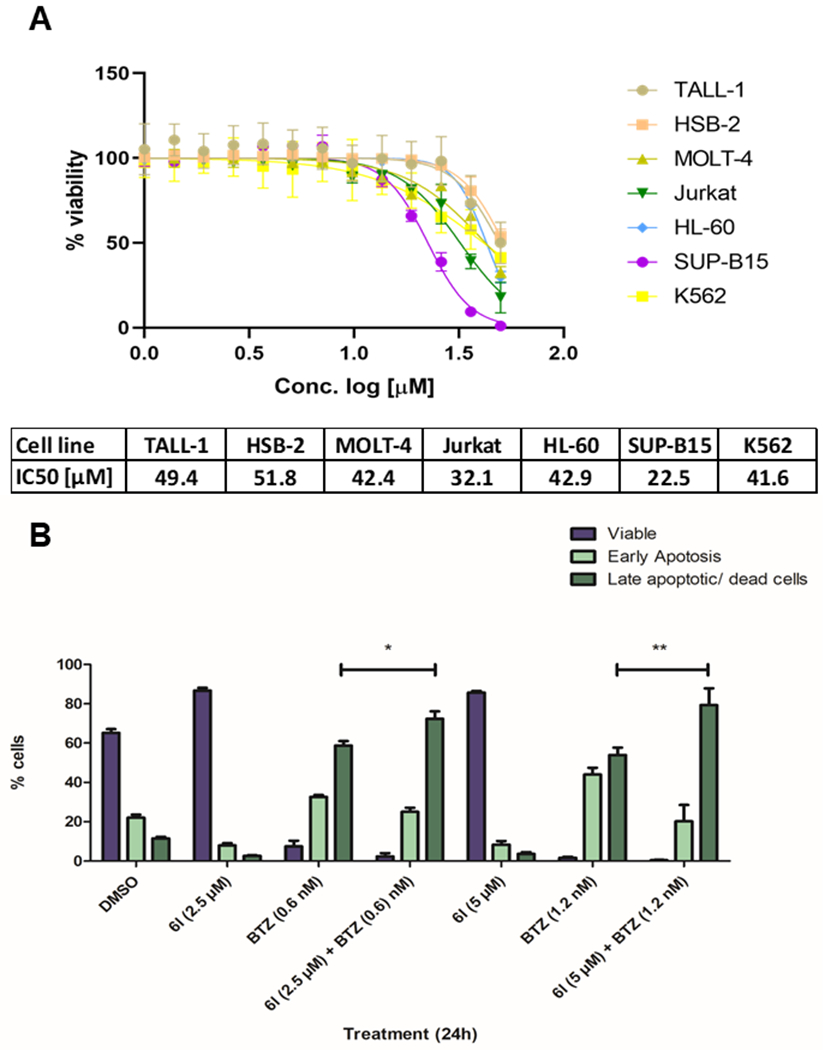

On the basis of the promising selectivity profile of compound 6l, we decided to evaluate its anticancer properties. First, we analysed the cytotoxic effects of 6l on a panel of seven leukemia cell lines originated from different leukemic subtypes. The cell lines were treated with a concentration gradient ranging from 1 μM to 50 μM (Figure 4A). Compound 6l had minor effects on the cell viability with IC50 values of > 20 μM (Figure 4A). This is in accordance with studies that indicate low single-agent cytotoxic properties of selective HDAC6 inhibitors.12,13 Recent studies revealed, however, that selective HDAC6 inhibitors show promising anticancer properties when combined with proteasome inhibitors.15,16,29,30 Therefore, we focused on the combination of 6l and the clinically used proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (BTZ). HL60 cells were treated for 24 h at two different concentrations of 6l or BTZ alone and in combination. The cytotoxic properties of 6l and BTZ as single agents and in combination were evaluated by using an annexin V-propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis assay. In accordance with the prior determined IC50 value for HL60 (42.9 μM), 6l alone showed no cytotoxic effect at 2.5 or 5 μM, as the number of viable cell was not affected (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Cytotoxic analysis of compound 6l. (A) Cytotoxicity of compound 6l against selected leukemic cell lines. (B) Annexin-PI staining of HL60 cells exposed to compound 6l alone, BTZ alone and compound 6l and BTZ in combination at the indicated concentration for 24 h (n=3). Significance analyses of normally distributed data with variance similar between groups used paired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. * < P 0.05, ** < P 0.005.

However, in combination with BTZ, 6l augmented the apoptosis induction of BTZ, as the number of late apoptotic/dead cells significantly increased when compared to BTZ alone. This effect becomes even more prominent with higher concentrations of both inhibitors (Figure 4B). These results suggest an anticipated synergistic induction of apoptosis in the HL60 cells due to the simultaneous inhibition of the proteasome as well as the aggresome formation.

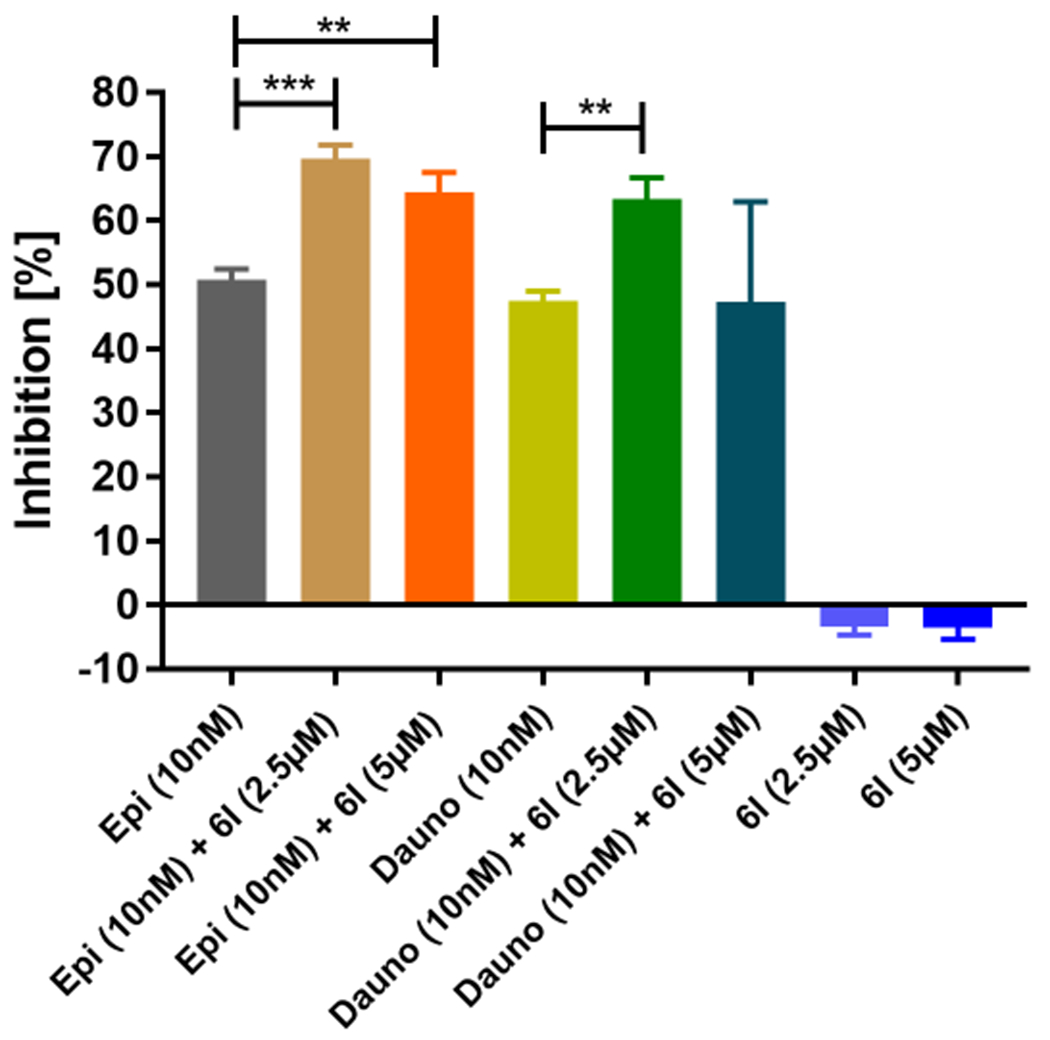

Encouraged by these results, we performed a high throughput drug combination screen using the T-ALL cell line (HSB-2) on a semi-automated platform with 6l (2.5 μM and 5 μM), 36 chemotherapeutics and 3 glucocorticoids (10 nM-25 μM), which are regularly applied to treat various cancers and leukemia (see Table S2 and Supplemental File 1, Supporting Information). We observed significant enhancement of cytotoxic activity of 6l especially with DNA intercalating anthracycline-based chemotherapeutic agents, i.e. epirubicin (Epi) and daunorubicin (Dauno), whereas 6l alone was unable to affect the cytotoxicity of the HSB-2 cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Combination analysis with 6l and chemotherapeutic compounds. Cytotoxicity of compound 6l alone or in combination with epirubicin (Epi) and daunorubicin (Dauno) against the T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cell line HSB-2. Significance analyses of normally distributed data (n=3) with variance similar between groups used unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. * < P 0.05, ** < P 0.005.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we have designed and synthesized a mini library of tetrazole-capped HDAC6 inhibitors. Besides obtaining valuable structure-activity relationship data, we were able to identify 6l, hereafter named NR-160, as a hit compound with remarkable selectivity for HDAC6 over class I isoforms which exceeded the selectivity of ricolinostat, HPOB, and nexturastat A and lies within the range of the widely-used tool compound tubastatin A. The co-crystal structure of HDAC6 complexed with NR-160 disclosed important molecular features responsible for HDAC6 selective inhibition. In particular, the steric complementarity of the bifurcated capping group of NR-160 to the L1 and L2 loop pockets was identified as an explanation for the selective binding to HDAC6. Additional enzymatic as well as cell-based assays were used to confirm the selectivity profile of the compound. Exhibiting only low cytotoxicity as a single-agent against a range of leukemia cell lines, NR-160 was found to have beneficial effects on apoptosis induction in HL60 cells treated with bortezomib. Moreover, NR-160 significantly enhanced cytotoxicity, when used in combination with epirubicin and daunorubicin, two drugs regularly used as chemotherapeutic agents in cancer treatment protocols. Surprisingly, it came up in several studies that exposure to selective HDAC6 inhibitors alone has no or very low cytotoxic effect on cancer cells.12 Instead, the cytotoxic effects observed in prior studies are most likely due to unselective binding at higher concentrations so that most of the observed anti-cancer effects may be attributed to unintentional HDAC class I inhibition.31,32 Therefore, we used NR-160 concentrations at which induction of histone H3 acetylation is not apparent in order to exclude the inhibition of class I HDACs. Accordingly, the enhanced cytotoxic effect of NR-160 in combination with bortezomib, epirubicin and daunorubicin emanates from selective HDAC6 inhibition alone. Although pan–HDACi have been approved for the treatment of haematological malignancies; they are often associated with severe adverse effects.33 Contrary to the other HDAC isoforms, HDAC6 deficiency has no or little effect on the development of mice, indicating HDAC6 as a potential therapeutic target.34 The usage of anthracyclines, on the other hand, is often associated with serious side effects, such as neuronal toxicity, cardiomyopathy and resistance.35,36 Hence, owing to the prominent role of HDAC6 in DNA repair machinery through interacting with microtubule dynamics after the anthracycline exposure, the combination with selective HDAC6 inhibitors can potentially decrease the drug related toxicity by reducing the drug dosage and enhance their potency by blocking drug resistance.17,37 Considering the good metabolic stability in presence of both human and mouse liver microsomes and the synthetic accessibility via a simple 3-step protocol, NR-160 can be considered a useful tool compound for selective HDAC6 inhibition with promising potential for combination therapies.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemistry.

Dry solvents, e.g. MeOH and DCM, were obtained from the MBraun MB SPS-800 solvent purification system. Except DCM, which was purified by distillation prior to use, all reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Thin layer chromatography was carried out using Macherey-Nagel pre-coated aluminium foil sheets, which were visualised using UV light (254 nm). Hydroxamic acids were stained using a 1% solution of iron(III) chloride in MeOH. 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded at rt or 60 °C using Bruker Avance III HD (400 MHz), and Varian/Agilent Mercury-plus (300 MHz & 400 MHz) spectrometers. Due to the occurrence of rotamers, some methylene group signals may overlap or appear twice and for two selected compounds (6j and 6l), additional spectra at temperatures ranging from rt to 70 °C are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S1 & S2). Chemical shifts (δ) are quoted in parts per million (ppm). All spectra were standardised in accordance with the signals of the deuterated solvents (DMSO-d6: δH = 2.50 ppm; δC = 39.5 ppm; CDCl3: δH = 7.26 ppm; δC = 77.0 ppm). Coupling constants (J) are reported in Hertz (Hz). Mass-spectra were measured by the Leipzig University Mass Spectrometry Service using electrospray ionisation (ESI) on Bruker Daltonics Impact II and Bruker Daltonics micrOTOF spectrometers. The uncorrected melting points were determined using a Barnstead Electrothermal 9100 apparatus. Analytical HPLC analysis were carried out using either a Gynkotek GINA 50 apparatus equipped with a Dionex P680A LPG pump, a Dionex UVD 340 U detector, and a China 50 autosampler, or a Thermo Fisher Scientific UltiMate 3000 system equipped with an UltiMateTM HPG-3400SD pump, an UltiMateTM 3000 Dioden array detector, an UltiMateTM 3000 autosampler, and a TCC-3000SD standard thermostatted column compartment by Dionex. Both systems were operated using Macherey-Nagel NUCLEODUR 100-5 C18 ec columns (250 mm x 4.6 mm). UV absorption was detected at 254 nm with a linear gradient of 5% B to 95% B within 23 min. HPLC-grade water + 0.1% TFA (solvent A) and HPLC-grade acetonitrile + 0.1% TFA (solvent B) were used for elution at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The purity of the final compounds was at least 95.0%.

General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 5a-c.

Paraformaldehyde (75.0 mg, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), methyl 4-(aminomethyl)benzoate hydrochloride (504 mg, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), and Et3N (0.34 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) were dissolved in MeOH (2 mL) and subjected to microwave irradiation at 45 °C and 150 W under high stirring for 30 min. The respective isocyanide (2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) and trimethylsilyl azide (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) were added consecutively and the resulting mixture was again subjected to microwave irradiation at the same settings for 4 h before the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude mixture was dissolved in MeOH (1 mL), followed by Et2O (20 mL) to precipitate triethylammonium chloride which was removed by filtration. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and recrystallised from MeOH (1 mL), 37% HCl (0.1 mL), and Et2O. The product was allowed to crystallise at 18 °C for 16 hours, isolated by filtration and washed with cold Et2O.

Methyl 4-({[(1-tert-butyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]amino}methyl)benzoate hydrochloride (5a).

Synthesised using tert-butyl isonitrile (0.28 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq). Purification by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 9:1 + 0.5% Et3N), followed by precipitation from MeOH (1 mL), Et2O (20 mL), and 37% HCl (0.2 mL) afforded 5a as a white solid (400 mg, 1.32 mmol, 53%); mp 200 – 204 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.37 (s, 2H, NH2), 8.09 – 7.98 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.80 – 7.67 (m, 2H, arom.), 4.85 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.45 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.87 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.67/1.52 (2 x s, 9H, tBu) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.9, 148.4, 136.9, 130.6, 130.1, 129.3, 62.0, 52.3, 50.0, 41.2, 40.2, 28.9 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C15H21N5O2 326.1587, found 326.1580.

Methyl 4-({[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]amino}methyl)benzoate hydrochloride (5b).

Synthesis using benzyl isocyanide (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) afforded 5b as an off-white solid (708 mg, 2.1 mmol, 84%); mp 155 – 160 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.31 (s, 2H, NH2.), 8.06 – 7.95 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.75 – 7.68 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.46 – 7.26 (m, 5H, arom.), 5.77 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.65 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.42 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.87 (s, 3H, CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.9, 149.1, 136.7, 133.9, 130.6, 130.1, 129.4, 128.9, 128.5, 128.4, 52.4, 50.6, 49.8, 38.0 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MH+ calcd for C18H19N5O2 338.1612, found 338.1621.

Methyl 4-({[(1-cyclohexyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]amino}methyl)benzoate hydrochloride (5c).

Synthesised using cyclohexyl isonitrile (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq). Purification by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 9:1), followed by precipitation from MeOH (1 mL), Et2O (20 mL), and 37% HCl (0.2 mL) afforded 5c as a white solid (458 mg, 1.39 mmol, 56%), mp 188 – 192 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.44 (br s, 2H, NH2), 8.05 – 8.00 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.78 – 7.72 (m, 2H, arom.), 4.69 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.64 – 4.53 (m, 1H, CH), 4.43 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.87 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.11 – 2.03 (m, 2H, c-Hexyl), 1.88 – 1.64 (m, 5H, c-Hexyl), 1.49 – 1.17 (m, 3H, c-Hexyl) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.9, 151.3, 148.2, 136.8, 130.7, 130.1, 129.3, 57.1, 56.5, 52.4, 49.8, 45.1, 38.1, 32.4, 24.6 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MH+ calcd for C17H23N5O2 330.1925, found 330.1926.

Methyl 4-({[(1-cyclohexyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methyl]amino}methyl)benzoate hydrochloride (5d).

Methyl 4-(aminomethyl)benzoate hydrochloride (504 mg, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), benzaldehyde (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), Et3N (0.34 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), and crushed molecular sieves 4Å (200 mg) were suspended in dry MeOH (4 mL) and stirred at rt for 30 min before cyclohexyl isonitrile (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) and trimethylsilyl azide (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) were added consecutively. After stirring at rt for 3 days, the molecular sieves were removed by filtration and washed with EtOAc (5 mL). The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and redissolved in MeOH (1 mL), followed by Et2O (20 mL) to precipitate triethylammonium chloride, which was removed by filtration. As addition of 37% HCl (0.2 mL) to the filtrate did not induce crystallisation of the product, 1M NaOH (pH 9) was added and the organic solvents were removed under reduced pressure. The residue was diluted with water (10 mL), extracted using EtOAC (3 x 50 mL), dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. Recrystallisation of the resulting crude product using EtOAc (1mL) and petrol (20 mL) afforded 5d as a white solid (853 mg, 2.10 mmol, 84%); mp 177 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.30 – 10.51 (m, 2H, NH2), 8.05 – 7.93 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.74 – 7.62 (m, 4H, arom.), 7.58 – 7.43 (m, 3H, arom.), 6.50 (s, 1H, CH), 4.53 – 4.39 (m, 1H, CH), 4.34 – 4.02 (m, 2H, CH2), 3.86 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.20 – 0.80 (m, 10H, c-Hexyl) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.9, 151.4, 130.6, 130.3, 129.9, 129.4, 129.3, 129.2, 57.2, 54.4, 52.3, 49.2, 32.4, 31.7, 24.6, 24.4, 24.3 ppm. HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C23H27N5O2 428.2057, found 428.2065.

Methyl 4-({[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methyl]amino}methyl)benzoate (5e).

Methyl 4-(aminomethyl)benzoate hydrochloride (504 mg, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), benzaldehyde (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), and Et3N (0.34 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) were dissolved in dry MeOH (1 mL) and subjected to microwave irradiation at 45 °C and 150 W under high stirring for 2 h. Benzyl isonitrile (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) and trimethylsilyl azide (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) were added consecutively and the resulting mixture was again subjected to microwave irradiation at the same settings for 4 h. To allow complete crystallisation, the reaction vessel was cooled to 0 °C for 2 h before the precipitate was isolated by filtration and washed with cold MeOH (2 mL) and n-hexane (10 mL). 5e was obtained as an off-white solid (813 mg, 1.97 mmol, 79%); mp 100 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.97 – 7.88 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.41 – 7.06 (m, 10H, arom), 6.95 – 6.83 (m, 2H, arom.), 5.40/5.17 (2 x d, J = 15.4/15.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.94 (s, 1H, NH), 3.93 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.71 (s, 2H, CH2) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.2, 156.2, 145.5, 138.1, 134.5, 129.1, 128.6, 128.5, 128.2, 128.1, 128.0, 127.8, 127.7, 55.2, 52.1, 50.1 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C24H23N5O2 436.1744, found 436.1756.

Methyl 4-({[1-(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)pentyl]amino}methyl)benzoate hydrochloride (5f).

Methyl 4-(aminomethyl)benzoate hydrochloride (504 mg, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), valeraldehyde (0.27 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq), and Et3N (0.34 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) were dissolved in dry MeOH (4 mL) and stirred at rt for 30 min before benzyl isonitrile (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) and trimethylsilyl azide (0.30 mL, 2.5 mmol, 1.0 eq) were added consecutively. After stirring at rt for 3 days, the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was redissolved in EtOAc (1 mL) and petrol (20 mL) to precipitate triethylammonium chloride which was removed by filtration. The filtrate was acidified using 37% HCl (0.2 mL) to obtain the hydrochloride salt of the product which was allowed to crystallise at −18 °C for 16 h before it was isolated by filtration. The crude product was recrystallised from MeOH (1 mL) and Et2O (20 mL) to afford 5f as a grey solid (542 mg, 1.26 mmol, 50%); mp 189 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.76 – 10.11 (m, 2H, NH2), 8.06 – 7.90 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.77 – 7.60 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.47 – 7.21 (m, 5H, arom.), 5.85 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 2H, CH2), 5.02 (s, 1H, CH), 4.37/4.18 (2 x d, J = 13.2/13.0 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.87 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.19 – 1.93 (m, 2H, CH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.26 – 0.74 (m, 4H, CH2CH2CH3), 0.61 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H, CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.8, 151.7, 136.9, 134.2, 130.5, 129.9, 129.2, 128.8, 128.6, 128.1, 52.3, 50.4, 49.9, 47.8, 30.1, 26.2, 21.5, 13.4 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MH+ calcd for C22H27N5O2 394.2238, found 394.2232.

General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 8a and 8b.

The respective carboxylic acid (0.70 mmol, 1.3 eq) was dissolved in dry DCM (5 mL) and cooled to 0 °C before thionyl chloride (0.08 mL, 1.1 mmol, 1.6 eq) was added dropwise. After 30 min of stirring at 0 °C, a solution of the respective ester or hydrochloride salt 5 (0.54 mmol, 1.0 eq) and Et3N (0.16 mL, 1.15 mmol, 2.1 eq) in dry DCM 2 mL) was added dropwise and the resulting mixture was stirred at rt for 16 h. The mixture was then diluted with DCM (100 mL) and washed with 10% aq. HCl (2x 10 mL), water (1 x 5 mL), sat. sodium bicarbonate solution (2 x 10 mL), water (1 x 5 mL), and brine (1 x 10 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was filtered over a layer of silica (n-hexane/EtOAC 3:1) to remove excess acyl chloride. The crude product was eluted using DCM/MeOH (9:1) and recrystallised from EtOAc (2 mL) and n-hexane (20 mL).

Methyl 4-({N-[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-(3,5-dimethylphenyl)formamido}methyl)benzoate (8a).

Synthesis using 5b (202 mg) and 3,5-dimethylbenzoic acid (105 mg) afforded 8a as a white oil (126 mg, 0.27 mmol, 50%); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.05 – 7.96 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.37 – 7.19 (m, 7H, arom.), 7.08 – 6.99 (m, 1H, arom.), 6.96 – 6.86 (m, 2H, arom.), 5.86 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.80 – 4.64 (m, 4H, 2x CH2), 3.92 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.39 – 2.35/2.29 – 2.21 (2 x m, 6H, 2 x CH3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.0, 166.7, 151.5, 140.8, 138.7, 138.3, 135.4, 134.2, 134.1, 132.2, 130.4, 130.1, 129.3, 129.3, 129.1, 129.0, 128.0, 127.9, 127.6, 127.5, 127.4, 124.5, 52.5, 52.4, 51.2, 36.0, 21.3 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C27H27N5O3 492.2006, found 492.2012.

Methyl 4-({N-[(1-cyclohexyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-(2-methylphenyl)formamido}methyl)benzoate (8b).

Synthesis using 5c (177 mg) and 2-methylbenzoic acid (95.0 mg) afforded 8b as a white oil (194 mg, 0.43 mmol, 80%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.06 – 7.96 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.33 – 7.16 (m, 6H, arom.), 5.02 – 4.29 (m, 5H, 2 x CH, 2 x CH2), 3.92 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.08 – 1.89 (m, 3H, CH3), 2.08 – 1.89 (m, 5H, c-Hexyl), 1.81 – 1.71 (m, 1H, c-Hexyl), 1.57 – 1.23 (m, 4H, c-Hexyl) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.5, 166.7, 150.4, 140.7, 134.8, 134.6, 131.0, 130.4, 130.3, 129.8, 128.9, 128.1, 127.8, 126.3, 125.8, 77.5, 77.2, 76.8, 58.4, 52.4, 52.0, 35.8, 32.7, 25.4, 25.0, 19.0 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C25H29N5O3 470.2163, found 470.2189.

General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 8c-f.

The respective ester 5 (0.54 mmol, 1.0 eq) and Et3N (0.16 mL, 2.15 mmol, 2.1 eq) were dissolved in dry DCM (10 mL) and the respective acyl chloride (0.65 mmol, 1.2 eq) was added dropwise at 0 °C. The resulting solution was stirred at rt for 16 h. Upon completion of the reaction, the mixture was diluted with DCM (100 mL) and washed with 10% aq. HCl (2x 10 mL), water (1 x 5 mL), sat. sodium bicarbonate solution (2 x 10 mL), water (1 x 5 mL), and brine (1 x 10 mL). The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by recrystallisation from EtOAc (2 mL) and petrol (20 mL) or by gradient column chromatography (EtOAc/petrol 3:1 to 1:1, followed by DCM/MeOH 9:1).

Methyl 4-({N-[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-phenylformamido}methyl)benzoate (8c).

Synthesised using 5b (202 mg) and benzoyl chloride (0.075 mL). Recrystallisation from EtOAc and petrol afforded 8c as a white solid (202 mg, 0.46 mmol, 85%); mp 115 – 118 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.06 – 7.93 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.48 – 7.12 (m, 12H, arom.), 5.84 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.76 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.69 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.89 (s, 3H, CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.7, 166.7, 151.5, 140.7, 134.3, 134.1, 133.6, 130.8, 130.5, 130.3, 130.2, 129.4, 129.0, 128.9, 127.7, 127.4, 127.0, 52.5, 52.4, 51.3, 36.3 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C25H23N5O3 464.1693, found 464.1696.

Methyl 4-({N-[(1-cyclohexyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-phenylformamido}methyl)benzoate (8d).

Synthesised using 5c (177 mg) and benzoyl chloride (0.075 mL). Filtration over a layer of silica using DCM/MeOH (9:1) as eluent and subsequent recrystallisation from EtOAc and n-hexane afforded 8d as a white solid (153 mg, 0.35 mmol, 65%); mp 78 – 82 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.95 – 7.86 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.35 – 7.15 (m, 7H, arom.), 4.74 – 4.58 (m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 4.58 – 4.46 (m, 1H, CH), 3.78 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.96 – 1.53 (m, 7H, c-Hexyl); 1.43 – 1.07 (m, 3H, c-Hexyl) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.4, 166.7, 150.4, 140.9, 134.6, 130.7, 130.5, 130.2, 129.0, 127.4, 126.9, 77.5, 77.2, 76.8, 58.3, 52.4, 36.3, 33.3, 27.1, 25.4, 25.0 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MH+ calcd for C24H27N5O3 434.2187, found 434.2182.

Methyl 4-({N-[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-[4-(propan-2-yl)phenyl]formamido}methyl)benzoate (8e).

Synthesised using 5b (202 mg) and 2-isopropylbenzoyl chloride (118 mg). Filtration over a layer of silica using DCM/MeOH (9:1) as eluent and subsequent recrystallisation from EtOAc and petrol afforded 8e as a yellow oil (145 mg, 0.30 mmol, 56%); mp 109 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.14 – 7.93 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.39 – 7.18 (m, 11H, arom.), 5.88 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.82 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.70 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.92 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.90 (p, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H, CH), 1.22 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H, 2 x CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.8, 166.7, 152.0, 151.5, 140.9, 134.1, 131.6, 130.5, 130.1, 129.4, 129.0, 127.7, 127.4, 127.2, 126.9, 77.5, 77.2, 76.8, 52.6, 52.4, 51.3, 36.3, 34.2, 23.9 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MH+ calcd for C28H29N5O3 484.2343, found 484.2339.

Methyl 4-({N-[1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]formamido}methyl)benzoate (8f).

Synthesised using 5b (202 mg) and 2-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl chloride (0.09 mL). Column chromatography afforded 8f as a yellow oil (257 mg, 0.50 mmol, 93%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.98 – 7.87 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.69 – 7.63 (m, 1H, arom.), 7.56 – 7.45 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.35 – 7.19 (m, 8H, arom.), 5.89 – 5.61 (m, 2H, CH2), 5.04 – 4.89/4.61 – 4.34 (2 x m, 4H, 2 x CH2), 3.86/3.84 (2 x s, 3H, CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.9, 166.6, 150.7, 139.7, 134.0, 133.3, 133.2, 132.5, 130.4, 130.3, 130.1, 129.9, 129.5, 129.3, 129.0, 128.7, 127.9, 127.7, 127.4, 127.3, 127.2, 127.1, 127.1, 126.9, 125.4, 121.8, 52.4, 51.9, 51.3, 47.8, 35.3 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MH+ calcd for C26H22F3N5O3 510.1748, found 510.1744.

4-({[(1-tert-Butyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]amino}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6a).

To a cooled solution of NaOH (149 mg, 3.73 mmol, 11 eq) in MeOH (4 mL) and DCM (1.5 mL) was added hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.62 mL, 10.1 mmol, 30 eq) and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 5 min before 5a (114 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.0 eq) was added in one batch. The solution was stirred at 0 °C for 60 min and then at rt for another 60 min before TLC (DCM/MeOH 9:1) indicated full conversion. The solvents were removed under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in water (10 mL). The mixture was neutralised using 10% aq. HCl (pH 8) and extracted using EtOAC (5 x 30 mL). The collected organics were dried over Na2SO4 and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Recrystallisation of the residue from MeOH (0.5 mL) and Et2O (10 mL) afforded 6a as a white solid (57 mg, 0.19 mmol, 55%); mp 154 °C (decomp.); tR: 5.72 min, purity: 95.5%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.20 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 9.00 (s, 1H, OH), 7.76 – 7.67 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.46 – 7.37 (m, 2H, arom.), 4.18 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.84 (s, 2H, CH2), 1.68/1.52 (2 x s, 9H, tBu) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.0, 152.5, 131.6, 128.8, 126.9, 61.4, 51.4, 42.3, 29.0 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MH+ calcd for C14H20N6O2 305.1721, found 305.1731.

General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 6b-l.

To a cooled (0 °C) solution of NaOH in MeOH (4 mL) and DCM (1.5 mL) was added hydroxylamine (50% solution in water) and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 5 minutes before a solution of the respective ester 5 or 8 in DCM (1 mL) was added dropwise. The resulting solution was stirred at 0 °C for 1-4 h until TLC (DCM/MeOH 9:1) indicated full conversion. Upon removal of the solvents in vacuo, the residue was suspended in water (10 mL) and neutralised using 10% aq. HCl (pH 8) to precipitate the crude product which was isolated by filtration and washed with water (5 x 4 mL). If HPLC proved insufficient purity <95%, the solid thus obtained was further purified by recrystallisation from MeOH (0.5 mL) and Et2O (10 mL) or EtOAc (0.5 mL) and petrol (10 mL), respectively.

4-({[(1-Benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]amino}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6b).

Synthesis using 5b (62.0 mg, 0.17 mmol 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.33 mL, 5.39 mmol, 32 eq), and NaOH (75.0 mg, 1.88 mmol, 11 eq), followed by recrystallisation from MeOH and Et2O afforded 6b as a white solid (47.0 mg, 0.14 mmol, 82%); mp 172 °C (decomp.); tR: 6.11 min, purity: 99.2%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.26 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 9.05 (s, 1H, OH), 7.82 – 7.69 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.55 – 7.21 (m, 7H, arom.), 5.74 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.32 (s, 2H, CH2), 4.05 (s, 2H, CH2) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.6, 149.4, 134.0, 133.2, 130.1, 128.9, 128.6, 128.3, 127.1, 50.6, 50.0, 38.2 ppm; HRMS (m/z): M− calcd for C17H18N6O2 337.1418, found 337.1430.

4-({[(1-Cyclohexyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]amino}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6c).

Synthesis using 5c (116 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.62 mL, 10.1 mmol, 30 eq), and NaOH (149 mg, 3.73 mmol, 11 eq), followed by recrystallisation from MeOH and Et2O afforded 6c as an off-white solid (53 mg, 0.16 mmol, 47%); mp 124 °C (decomp.); tR: 6.23 min, purity: 99.3%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.17 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 9.00 (s, 1H, OH), 7.79 – 7.68 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.46 – 7.30 (m, 2H, arom.), 4.61 – 4.49 (m, 1H, CH), 4.00 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.73 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.05 – 1.60 (m, 7H, c-Hexyl), 1.48 – 1.20 (m, 3H, c-Hexyl) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.0, 152.9, 143.4, 131.3, 127.9, 126.8, 56.7, 51.7, 40.4, 32.4, 24.8, 24.6 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C16H22N6O2 353.1696, found 353.1692.

4-({[(1-Cyclohexyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methyl]amino}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6d).

Synthesis using 5d (110 mg, 0.25 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.45 mL, 7.34 mmol, 30 eq), and NaOH (101 mg, 2.53 mmol, 10 eq) afforded 6d as a red solid (81.0 mg, 0.18 mmol, 73%); mp 101 °C (decomp.); tR: 6.98 min, purity: 97.0%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.39 – 10.83 (br s, 1H, NH-OH), 9.30 – 8.73 (br s, 1H, OH), 7.91 – 7.67 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.54 – 7.27 (m, 7H, arom.), 5.34 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, Ph-CH), 4.65 – 4.47 (m, 1H, c-Hexyl-CH), 3.80 – 3.59 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.85 – 1.47 (m, 7H, c-Hexyl), 1.47 – 1.04 (m, 3H, c-Hexyl) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.9, 155.1, 143.2, 138.5, 131.3, 129.2, 128.6, 128.0, 127.9, 127.7, 127.7, 126.8, 56.8, 55.3, 50.0, 32.34, 32.31, 24.7, 24.5 ppm; HRMS (m/z): M− calcd for C22H26N6O2 405.2044 found 405.2041.

4-({[(1-Benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methyl]amino}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6e).

Synthesis using 5e (140 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.62 mL, 10.1 mmol, 30 eq), and NaOH (139 mg, 3.48 mmol, 10 eq), followed by recrystallisation from MeOH and Et2O afforded 6e as a pale brown solid (114 mg, 0.28 mmol, 81%); mp 93 °C (decomp.); tR: 6.79 min, purity: 98.9%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.18 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 8.94 (s, 1H, OH), 7.74 – 7.61 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.43 – 7.19 (m, 10H, arom.), 7.08 – 6.94 (m, 2H, arom.), 5.77 – 5.52 (m, 2H, CH2), 5.28 (s, 1H, CH), 3.63 (s, 2H, CH2) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.1, 156.2, 143.0, 138.1, 134.5, 131.3, 129.3, 128.6, 128.5, 128.2, 128.0, 127.9, 127.8, 127.7, 126.8, 55.2, 50.09, 50.06 ppm; HRMS (m/z): M− calcd for C23H22N6O2 413.1731 found 413.1746.

4-({[1-(1-Benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)pentyl]amino}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6f).

Synthesis using 5f (146 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.62 mL, 10.1 mmol, 30 eq), and NaOH (149 mg, 3.73 mmol, 11 eq), followed by recrystallisation from MeOH and Et2O afforded 6f as an off-white solid (30.0 mg, 0.08 mmol, 28%); mp 130 °C (decomp.); tR: 6.94 min, purity: 99.0%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.15 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 8.98 (s, 1H, OH), 7.70 – 7.59 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.39 – 7.23 (m, 5H, arom.), 7.18 – 7.13 (m, 2H, arom.), 5.79 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH2), 5.65 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, CH2), 4.09 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, CH), 3.62 – 3.42 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.91 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, NH), 1.81 – 1.51 (m, 2H, CH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.15 – 0.83 (m, 4H, CH2CH2CH3), 0.70 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H, CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.0, 156.5, 143.3, 134.9, 131.2, 128.8, 128.2, 127.7, 127.5, 126.7, 51.7, 49.9, 49.8, 40.2, 39.7, 33.0, 27.5, 21.7, 13.7 ppm; HRMS (m/z): M− calcd for C21H26N6O2 393.2044 found 393.2053.

4-({N-[(1-Cyclohexyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-phenylformamido}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6g).

Synthesis using 8d (100 mg, 0.23 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.43 mL, 7.02 mmol, 31 eq), and NaOH (90 mg, 2.25 mmol, 9.8 eq) afforded 6g as a white solid (71.0 mg, 0.16 mmol, 70%); mp 106 °C (decomp.); tR: 7.98 min, purity: 97.7%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.23 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 9.03 (s, 1H, OH), 7.82 – 7.71 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.51 – 7.28 (m, 7H, arom.), 4.93 – 4.52 (m, 5H, 2x CH2, CH), 1.95 – 1.07 (m, 10H, c-Hexyl) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.3, 163.8, 151.4, 139.6, 135.1, 131.9, 130.0, 128.6, 127.3, 126.8, 126.4, 56.7, 52.5, 32.3, 24.6, 24.5 ppm; HRMS (m/z): M− calcd for C23H26N6O3 435.2139 found 435.2141.

4-({N-[(1-Cyclohexyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-(2-methylphenyl)formamido}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6h).

Synthesis using 8b (105 mg, 0.23 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.43 mL, 7.02 mmol, 31 eq), and NaOH (90 mg, 2.25 mmol, 9.8 eq), followed by recrystallisation from EtOAc and petrol afforded 6h as a pink solid (62.0 mg, 0.14 mmol, 60%); mp 117 °C (decomp.); tR: 8.31 min, purity: 95.1%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.22 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 9.03 (s, 1H, OH), 7.83 – 7.66 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.51 – 7.06 (m, 6H, arom.), 4.90 (s, 1H, CH2), 4.68 – 4.52 (m, 3H, 2 x CH2), 2.18 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.07 – 1.08 (m, 10H, c-Hexyl) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.2, 163.7, 151.4, 139.4, 135.2, 134.2, 132.0, 130.5, 130.4, 129.2, 127.7, 127.3, 127.2, 127.0, 125.8, 125.4, 56.7, 56.3, 52.0, 32.4, 31.9, 24.6, 24.5, 24.3, 18.5, 18.4 ppm; HRMS (m/z): M− calcd for C24H28N6O3 447.2150 found 447.2149.

4-({N-[(1-Benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-phenylformamido}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6i).

Synthesis using 8c (150 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.62 mL, 10.1 mmol, 30 eq), and NaOH (139 mg, 3.48 mmol, 10 eq), followed by recrystallisation from MeOH and Et2O afforded 6i as a white solid (93.0 mg, 0.21 mmol, 62%); mp 108 °C (decomp.); tR: 7.84 min, purity: 97.7%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.21 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 9.07 (s, 1H, OH), 7.80 – 7.71 (m, 2H), arom., 7.52 – 7.21 (m, 12H, arom.), 5.73 (s, 1H, CH2), 5.41 (s, 1H, CH2), 4.90 (s, 1H, CH2), 4.75 – 4.59 (m, 3H, 2 x CH2) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.4, 163.7, 152.4, 139.4, 135.0, 134.5, 130.0, 128.9, 128.6, 128.3, 127.7, 127.3, 127.3, 126.8, 126.4, 52.5, 49.9, 37.9; HRMS (m/z): M− calcd for C24H22N6O3 441.1681 found 441.1687.

N-[(1-Benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-N-{[4-(hydroxycarbamoyl)phenyl]methyl}-3,5-dimethylbenzamide (6j).

Synthesis using 8a (159 mg, 0.34 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.64 mL, 10.4 mmol, 31 eq), and NaOH (137 mg, 3.43 mmol, 10 eq), followed by recrystallisation from MeOH and Et2O afforded 6j as an off-white solid (61.0 mg, 0.13 mmol, 38%); mp 98 °C (decomp.); tR: 8.38 min, purity: 96.6%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.23 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 10.10 (d, J = 59.1 Hz, 1H, OH), 7.81 – 7.66 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.47 – 7.13 (m, 6H, arom.), 7.12 – 6.77 (m, 4H, arom.), 5.73 (s, 1H, CH2), 5.38 (s, 1H, CH2), 4.90 (s, 1H, CH2), 4.74 – 4.55 (m, 3H, 2 x CH2), 2.20 (s, 6H, 2 x CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.6, 163.8, 152.4, 139.6, 137.7, 134.9, 134.5, 131.9, 131.2, 128.8, 128.3, 127.6, 126.9, 124.0, 123.6, 52.3, 49.9, 40.2, 37.6, 20.7 ppm; HRMS (m/z): M− calcd for C26H26N6O3 469.1994 found 469.1996.

4-({N-[(1-Benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-[4(propan-2-yl)phenyl]formamido}methyl)-N-hydroxybenzamide (6k).

Synthesis using 8e (110 mg, 0.23 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.43 mL, 7.02 mmol, 31 eq), and NaOH (90 mg, 2.25 mmol, 9.8 eq) afforded 6k as an off-white solid (98 mg, 0.20 mmol, 88%); mp 121 °C (decomp.); tR 8.78 min, purity: 95.0%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.21 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 9.07 (s, 1H, OH), 7.94 – 7.61 (m, 2H, arom.), 7.44 – 7.06 (m, 11H, arom.), 5.80 – 5.34 (m, 2H, CH2), 4.96 – 4.59 (m, 3H, 2 x CH2), 4.09/3.77 (2 x s, 1H, CH2), 2.99 – 2.82 (m, 1H, CH), 1.18 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H, 6H, 2 x CH3) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 175.4, 166.1, 166.1, 163.1, 152.4, 150.5, 134.6, 132.5, 128.9, 128.3, 127.7, 127.7, 126.7, 126.7, 126.6, 126.4, 49.9, 40.2, 40.2, 33.3, 25.2, 23.6, 19.5 ppm; tR: 8.79 min, purity: 95.1%; HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C27H28N6O3 507.2115 found 507.2110.

4-({N-[(1-Benzyl-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl]-1-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]formamido}methyl-N-hydroxybenzamide (6l).

Synthesis using 8f (117 mg, 0.23 mmol, 1.0 eq), hydroxylamine (50% solution in water, 0.43 mL, 7.02 mmol, 31 eq), and NaOH (90.0 mg, 2.25 mmol, 9.8 eq) afforded 6l as a pale brown solid (98.0 mg, 0.19 mmol, 83%); mp 103 °C (decomp.); tR: 8.25 min, purity: 95.0%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, 60 °C, DMSO-d6) δ 11.08 (s, 1H, NH-OH), 8.89 (s, 1H, OH), 7.95 – 6.79 (m, 13H, arom.), 5.73 (s, 1H, CH2), 5.39 (s, 1H, CH2), 4.93 (s, 1H, CH2), 4.66 – 4.22 (m, 3H, 2 x CH2) ppm; 13C NMR (101 MHz, 26 °C, DMSO-d6) δ 168.8, 168.4, 163.8, 163.6, 151.9, 151.7, 139.5, 138.4, 134.4, 133.5, 133.4, 133.3, 133.3, 132.9, 132.7, 132.1, 131.8, 130.2, 130.1, 128.8, 128.34, 128.27, 128.0, 127.9, 127.34, 127.25, 127.21, 127.16, 127.0, 126.9, 126.83, 126.80, 125.7, 125.4, 125.2, 125.1, 124.9, 124.9, 122.21, 122.18, 52.2, 50.0, 49.7, 47.9, 42.3, 37.2 ppm; HRMS (m/z): MNa+ calcd for C25H21F3N6O3 533.1519 found 533.1516.

Crystal structure determination.

All reagents were purchased from Fisher Scientific, Millipore Sigma, or Hampton Research and used without further purification. HDAC6 catalytic domain 2 (CD2, residues 440-798; herein designated “zCD2”) from Danio rerio (zebrafish) was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described.38 Crystallisation was achieved by the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method. A 350-nL drop of protein solution [10 mg/mL zCD2, 50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 5% glycerol, and 2 mM NR160 in dimethyl sulfoxide] was added to a 350-nL drop of precipitant solution [0.2 M ammonium citrate tribasic pH 7.0, 20% w/v polyethylene glycol 3350] and equilibrated against 80 μL of precipitant solution in the well reservoir. Plate-like crystals appeared within two days at 4° C. Ethylene glycol (15% v/v) was added to the mother liquor as a cryoprotectant prior to flash-cooling crystals for X-ray diffraction data collection. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT) beamline 24-ID-C, Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Data were indexed and integrated using iMosflm39 and scaled using Aimless in the CCP4 program suite.40 The initial electron density map was phased by molecular replacement using the atomic coordinates of unliganded zHDAC6 (PDB 5EEM)23 as a search model. Residue conformations were manually adjusted using the graphics program COOT,41 and PHENIX42 was used for structure refinement. Inhibitor and solvent molecules were added in the later stages of refinement. MolProbity43 was used to assess the quality of the structure. All data collection and refinement statistics are recorded in Table S2.

Inhibition assay for HDAC1-3 and HDAC6.

The in vitro inhibitory activity of compounds 1-3 and vorinostat against human HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3/NcoR2 and HDAC6 were measured using a previously published protocol.44 OptiPlate-96 black microplates (Perkin Elmer) were used with an assay volume of 50 μL. 5.0 μL test compound or control, diluted in assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/mL BSA), were incubated with 35 μL of the fluorogenic substrate ZMAL (Z-Lys(Ac)-AMC)45 (21.43 μM in assay buffer) and 10 μL of human recombinant HDAC1 (BPS Bioscience, Catalog# 50051), HDAC2 (BPS Bioscience, Catalog# 50052), HDAC3/NcoR2 (BPS Bioscience, Catalog# 50003) or HDAC6 (BPS Bioscience, Catalog# 50006) at 37 °C. After an incubation time of 90 min, 50 μL of 0.4 mg/mL trypsin in trypsin buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) were added, followed by further incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. Fluorescence was measured with an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm using a Fluoroskan Ascent microplate reader (Thermo Scientific). All compounds were evaluated in duplicate in at least two independent experiments.

Inhibition assay for HDAC4 and HDAC8.

Human recombinant enzymes HDAC4 and HDAC8 were purchased from Reaction Biology (Malvern, PA, USA). HDAC inhibition assays were performed in 96-well-plates (Corning, Kaiserslautern, Germany). Recombinant enzymes were diluted in assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mg/mL BSA). 20 ng of HDAC4 or HDAC8 were used per well. After addition of assay buffer (control) or inhibitors diluted in assay buffer and a 5 min incubation step, enzyme reaction was started by addition of 100 μM (HDAC4) or 60 μM (HDAC8) Boc-Lys-(ε-Tfa)-AMC (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland). The reaction was stopped after 90 min by adding 100 μL stop solution containing 16 mg/mL trypsin (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany) and 8 μM panobinostat (Selleckchem, Houston, Texas, USA). 15 min after addition of the stop solution, fluorescence intensity was measured at an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm in a NOVOstar microplate reader (BMG LabTech, Offenburg, Germany). Panobinostat served as inhibition control for HDAC8 (IC50: 0.48±0.08 μM), CHDI 00390576 (Tocris, Wiesbaden-Nordenstadt, Germany) as control for HDAC4 (IC50: 0.35±0.04 μM).

Cell Culture.

HL60 (AML), K562 (CML) were cultured in in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. Molt-4, Jurkat, HSB-2 and TALL-1 (T-ALL) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% FCS (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). SUP-B15 (BCP-ALL) was cultured in McCoy’s 5A supplemented with 20% FCS (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany).

Cell Viability Assay.

CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Madison, USA) was performed to determine the IC50 values for every cell line. Compound 6l was printed using on white 384-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) with increasing concentrations (1 μM - 50 μM) by using a digital dispenser (D300e, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Cell viability was monitored after 72 h using CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay using a microplate reader (Spark, Tecan). IC50 for the compound 6l was determined by plotting raw data (normalized to controls) using sigmoid dose curve and nonlinear regression (GraphPad Prism Inc., San Diego, CA).

Combinatorial drug screening.

Combination screen was performed on a semi-automated platform following similar procedure as for the cell viability readout, described above. Briefly, the chemotherapeutic and glucocorticoid compounds (SelleckChem.com, Texas, USA) were printed with increasing concentrations (10 nM - 25 μM) alone or in combination with 6l (either 2.5 μM or 5 μM) by using a digital dispenser (D300e, Tecan).

Annexin V staining.

For evaluating apoptosis, cells treated with respective compounds or control for 24 h were stained with annexin V and PI and later subjected to FACS, following supplier’s guidelines (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Western Blotting.

Cell lysates were generated after 24 h treatment with the respective inhibitors and later immunoblotted using anti-acetyl-α-tubulin (no. 5335), anti-α-tubulin (no. 2144), antiacetyl-histone H3 (no. 9677S), anti-histone H3 (no. 9715), anti-Beta-Actin (no. 5125S), following supplier’s guidelines (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA).

In Vitro Metabolism.

Metabolic stability assay in human and mouse liver microsomes were performed under contract by Bienta (Enamine Biology Services, Kyiv, Ukraine), and more detailed information about the assays is given at bienta.net.

PAINS Analysis.

We filtered all compounds for pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) using the online filter http://zinc15.docking.org/patterns/home/.46 No compound was flagged as PAINS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Narayanasami Sukumar and the beamline staff at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT), which is funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P30 GM124165). The Pilatus 6M detector on beamline 24-ID-C is funded by a NIH ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Funding Sources

S.B. acknowledges the financial support by Forschungskommission (2018-04) and DSO-Netzwerkverbundes, HHU Dusseldorf. J.H. and A.B. have been supported by the TransOnc priority program of the German Cancer Aid within grant #70112951 (ENABLE).and Deutsches Konsortium fur Translationale Krebsforschung (DKTK), Joint funding (Targeting MYC L*10). J.H. is supported by the ERC Stg 852222; Testing on human HDACs was in part supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG: HA 7783/1-1 to FKH). D.W.C. is supported by grant GM49758 from the US National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DCM

dichloromethane

- Et2O

diethyl ether

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- MeOH

methanol

- min

minutes

- petrol

petroleum ether

- rt

room temperature

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- UA4CR

Ugi-azide four-component reaction

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Supplementary tables, NMR spectra, and HPLC traces of newly synthesised compounds. (PDF)

Molecular formula strings and some data (CSV)

Results from the drug combination screening (xlsx)

Accession Code

The atomic coordinates and crystallographic structure factors of the HDAC6 complex with inhibitor NR160 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) with the accession code 6PYE. Authors will release the atomic coordinates upon article publication.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biel M; Wascholowski V; Giannis A Epigenetics - an epicenter of gene regulation: histones and histone-modifying enzymes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 3186–3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertrand P Inside HDAC with HDAC inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2010, 45, 2095–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hai Y; Shinsky SA; Porter NJ; Christianson DW Histone deacetylase 10 structure and molecular function as a polyamine deacetylase. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 15368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roche J; Bertrand P Inside HDACs with more selective HDAC inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2016, 121, 451–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckschlager T; Plch J; Stiborova M; Hrabeta J Histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer drugs. J. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2017, 18, 1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y; Seto E HDACs and HDAC inhibitors in cancer development and therapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 2016; 6, a026831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalin JH; Bergman JA Development and therapeutic implications of selective histone deacetylase 6 inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 6297–6313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valenzuela-Fernandez A; Cabrero JR; Serrador JM; Sanchez-Madrid F. HDAC6: a key regulator of cytoskeleton, cell migration and cell-cell interactions. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brindisi M; Prasanth Saraswati A; Brogi S; Gemma S; Butini S; Campiani G Old but gold: tracking the new guise of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) enzyme as a biomarker and therapeutic target in rare diseases. J. Med. Chem 2020, 63, 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simões-Pires C; Zwick V; Nurisso A; Schenker E; Carrupt PA; Cuendet M HDAC6 as a target for neurodegenerative diseases: what makes it different from the other HDACs?. Mol Neurodegener. 2013, 8, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen S; Kozikowski AP A patent review of histone deacetylase 6 inhibitors in neurodegenerative diseases (2014-2019). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2020, 30, 121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Depetter Y; Geurs S; De Vreese R; Goethals S; Vandoorn E; Laevens A; Steenbrugge J; Meyer E; de Tullio P; Bracke M; D’hooghe M; De Wever O Selective pharmacological inhibitors of HDAC6 reveal biochemical activity but functional tolerance in cancer models. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 735–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaisina IN; Tueckmantel W; Ugolkov A; Shen S; Hoffen J; Dubrovskyi O; Mazar A; Schoon RA; Billadeau D; Kozikowski AP Identification of HDAC6-selective inhibitors of low cancer cell cytotoxicity. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suraweera A; O’Byrne KJ; Richard DJ Combination therapy with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) for the treatment of cancer: achieving the full therapeutic potential of HDACi. Front. Oncol 2018, 8, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hideshima T; Richardson PG; Anderson KG Mechanism of action of proteasome inhibitors and deacetylase inhibitors and the biological basis of synergy in multiple myeloma. Mol. Cancer Ther 2011, 10, 2034–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huber EM; Groll M Inhibitors for the immuno- and constitutive proteasome: current and future trends in drug development. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 8708–8720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu HJ; Lin YJ; Chao MW; Sung TY; Wu YW; Chen YY; Lin MH; Liou JP; Pan SL; Yang CR The anticancer effects of MPT0G211, a novel HDAC6 inhibitor, combined with chemotherapeutic agents in human acute leukemia cells. Clin. Epigenetics 2018, 29, 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diedrich D; Hamacher A; Gertzen CGW; Alves Avelar LA; Reiss GJ; Kurz T; Gohlke H; Kassack MU; Hansen FK Rational design and diversity-oriented synthesis of peptoid-based selective HDAC6 inhibitors. Chem. Commun, 2016, 52, 3219–3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diedrich D; Stenzel K; Hesping E; Antonova-Koch Y; Gebru T; Duffy S; Fisher G ; Schöler A; Meister S; Kurz T; Avery VM; Winzeler E; Held J; Andrews KT; Hansen FK One-pot, multi-component synthesis and structure-activity relationships of peptoid-based histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors targeting malaria parasites. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 158, 801–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackwitz MKW; Hesping E; Antonova-Koch Y; Diedrich D; Gebru T, Skinner-Adams T; Clarke M; Schöler A; Limbach L, Kurz T; Winzeler EA; Held J; Andrews KT; Hansen FK Structure-activity and structure-toxicity relationships of novel peptoid based histone deacetylase inhibitors with dual-stage antiplasmodial activity. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 912–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porter NJ; Osko JD; Diedrich D; Kurz T; Hooker JM; Hansen FK; Christianson DW Histone deacetylase 6-selective inhibitors and the influence of capping groups on hydroxamate-zinc denticity. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 8054–8060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackwitz MKW; Hamacher A; Osko JD; Held J; Schöler A; Christianson DW; Kassack MU; Hansen FK Multicomponent synthesis and binding mode of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-capped selective HDAC6 inhibitors. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 3255–3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hai Y; Christianson DW Histone deacetylase 6 structure and molecular basis of catalysis and inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 741–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter NJ; Mahendran A; Breslow R; Christianson DW Unusual zinc-binding mode of HDAC6-selective hydroxamate inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114, 13459–13464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter NJ; Wagner FF; Christianson DW Entropy as a driver of selectivity for inhibitor binding to histone deacetylase 6. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 3916–3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatia S; Krieger V; Groll M; Osko JD; Reßing N; Ahlert H; Borkhardt A; Kurz T; Christianson DW; Hauer J; Hansen FK. Discovery of the first-in-class dual histone deacetylase-proteasome inhibitor. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 10299–10309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A. O’Hagan D, Howard JAK, Hoy VJ, Smith GT How good is fluorine as a hydrogen bond acceptor? Tetrahedron 1996, 38, 12613–12622. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalvit C, Invernizzi C, Vulpetti A Fluorine as a hydrogen-bond acceptor: experimental evidence and computational calculations. Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 11058–11068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messinger Y; Gaynon P; Raetz E; Hutchinson R; DuBois S; Glade-Bender J; Sposto R; v. d. Giessen J; Eckroth E; Bostrom BC. Phase I study of bortezomib combined with chemotherapy in children with relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): a report from the therapeutic advances in childhood leukemia (TACL) consortium. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2010, 55, 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Messinger YH; Gaynon PS; Sposto R; v. d. Giessen J; Eckroth E; Malvar J; Bostrom BC. Bortezomib with chemotherapy is highly active in advanced B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: therapeutic advances in childhood leukemia & lymphoma (TACL) Study. Blood 2012, 120, 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linn A; Giuliano CJ; Palladino A; John KM; Abramovicz C; Lou Yuan M; Sausville EL; Lukow DA; Liu L; Chait AR; Galluzzo ZC; Tucker C; Sheltzer JM Off-target toxicity is a common mechanism of action of cancer drugs undergoing clinical trials. Sci. Transl. Med 2019, 11, eaaw8412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haberland M; Johnson A; Mokalled MH; Montgomery RL; Olson EN Genetic dissection of histone deacetylase requirement in tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. USA 2009, 106, 7751–7755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramanian S; Bates SE; Wright JJ; Espinoza-Delgado I; Piekarz RL Clinical toxicities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Phamaceuticals 2010, 3, 2751–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y; Kwon S; Yamaguchi T; Cubizolles F; Rousseaux S; Kneissel M; Cao C; Li N; Cheng HL; Chua K; Lombard D; Mizeracki A; Matthias G; Alt FW; Khochbin S; Matthias P Mice lacking histone deacetylase 6 have hyperacetylated tubulin but are viable and develop normally. Mol. Cell. Biol 2008, 28, 1688–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chatterjee K; Zhang J; Honbo N; Karliner JS Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 2010, 115, 155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park SB; Goldstein D; Krishnan AV; Lin CS; Friedlander ML; Cassidy J; Koltzenburg M; Kiernan MC Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: a critical analysis. CA Cancer J. Clin 2013, 63, 419–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zilberman Y; Ballestrem C; Carramusa L; Mazitschek R; Khochbin S; Bershadsky A Regulation of microtubule dynamics by inhibition of the tubulin deacetylase HDAC6. J. Cell. Sci 2009, 122, 3531–3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osko JD; Christianson DW Methods for the expression, purification, and crystallization of histone deacetylase 6-inhibitor complexes. Methods Enzymol. 2019, 626, 447–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Battye TGG; Kontogiannis L; Johnson O; Powell HR; Leslie AGW iMosflm: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with Mosflm. Acta Crystallogr. 2011, Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winn MD; Ballard CC; Cowtan KD; Dodson EJ; Emsley P; Evans PR; Keegan RM; Krissinel EB; Leslie AGW; McCoy A; McNicholas SJ; Murshudov GN; Pannu NS; Potterton EA; Powell, Read RJ; Vagin A; Wilson KS Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Sect D: Biol. Crystallogr 2011, 67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley P; Lohkamp B; Scott WG; Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams PD; Afonine PV; Bunkóczi G; Chen VB; Davis IW; Echols N; Headd JJ; Hung L; Kapral GJ; Grosse-Kunstleve RW; McCoy AJ; Moriarty NW; Oeffner R; Read RJ; Richardson DC; Richardson JS; Terwilliger TC; Zwart PH PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen VB; Arendall WB 3rd; Headd JJ; Keedy DA; Immormino RM; Kapral GJ; Murray LW; Richardson JS; Richardson DC MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2010, 66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raudszus R; Nowotny R; Gertzen CGW; Schöler A; Krizsan A; Gockel I; Kalwa H ; Gohlke H; Thieme R; Hansen FK Fluorescent analogs of peptoid-based HDAC inhibitors: synthesis, biological activity and cellular uptake kinetics. Bioorganic Med. Chem 2019, 27 (19), 115039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heltweg B; Dequiedt F; Verdin E; Jung M Nonisotopic substrate for assaying both human zinc and NAD+-dependent histone deacetylases. Anal. Biochem 2003, 319, 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baell JB; Holloway GA New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem 2010, 53, 2719–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.