Abstract

Distinct cell types emerge from embryonic stem cells through a precise and coordinated execution of gene expression programs during lineage commitment. This is established by the action of lineage specific transcription factors along with chromatin complexes. Numerous studies have focused on epigenetic factors that affect embryonic stem cells (ESC) self-renewal and pluripotency. However, the contribution of chromatin to lineage decisions at the exit from pluripotency has not been as extensively studied. Using a pooled epigenetic shRNA screen strategy, we identified chromatin-related factors critical for differentiation toward mesodermal and endodermal lineages. Here we reveal a critical role for the chromatin protein, ARID4B. Arid4b-deficient mESCs are similar to WT mESCs in the expression of pluripotency factors and their self-renewal. However, ARID4B loss results in defects in up-regulation of the meso/endodermal gene expression program. It was previously shown that Arid4b resides in a complex with SIN3A and HDACS 1 and 2. We identified a physical and functional interaction of ARID4B with HDAC1 rather than HDAC2, suggesting functionally distinct Sin3a subcomplexes might regulate cell fate decisions Finally, we observed that ARID4B deficiency leads to increased H3K27me3 and a reduced H3K27Ac level in key developmental gene loci, whereas a subset of genomic regions gain H3K27Ac marks. Our results demonstrate that epigenetic control through ARID4B plays a key role in the execution of lineage-specific gene expression programs at pluripotency exit.

Keywords: embryonic stem cell, cell differentiation, epigenetics, gene expression, chromatin modification, embryonic stem cell

During early embryonic development, a series of differentiation and cleavage events lead to the formation of distinct cell types that later form the organism. The emergence of various cell types is a complex process that requires a precisely timed mechanism for successful development. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) provide an in vitro model for studying early cell fate decisions. ESCs self-renew limitlessly in vitro. Because they have the capacity to form all cell types (pluripotency), they can be directed to desired lineages under the guidance of specific cytokines.

Cell fate decisions are executed by changes in gene expression. Whereas the gene expression program of a particular lineage is being established, unrelated programs are simultaneously extinguished. The chromatin environment plays a critical role in regulating the timing and the level of gene expression. The ESC-specific gene expression program is stabilized by the interactions of core pluripotency transcription factors and chromatin complexes (1–3). The plasticity of ESC differentiation potential is reflected in an open chromatin structure. Progressively during differentiation, ESCs undergo reorganization of chromatin, architecture and genomic topology (4–9). Alterations in the chromatin environment of ESCs, therefore, may impact lineage commitment dynamics.

Studies have identified chromatin factors regulating the ESC self-renewal and pluripotency (10–18). It is becoming increasingly clear that the chromatin architecture and histone modifications at the ESC stage can affect cell fate specification and differentiation kinetics at later stages (17, 19). However, a comprehensive study of the epigenetic regulators subsequent to the loss of self-renewal and pluripotency has been lacking. Therefore, we sought to determine the role of chromatin factors in an unbiased manner during meso/endodermal lineage commitment. To accomplish this goal, we have monitored the expression of the first lineage-specific master transcription factors to enable a more precise look at the chromatin-related requirements at cell fate decisions. Our approach departs from previous reports focusing on epigenetic effects on ESC characteristics (10, 12).

Results

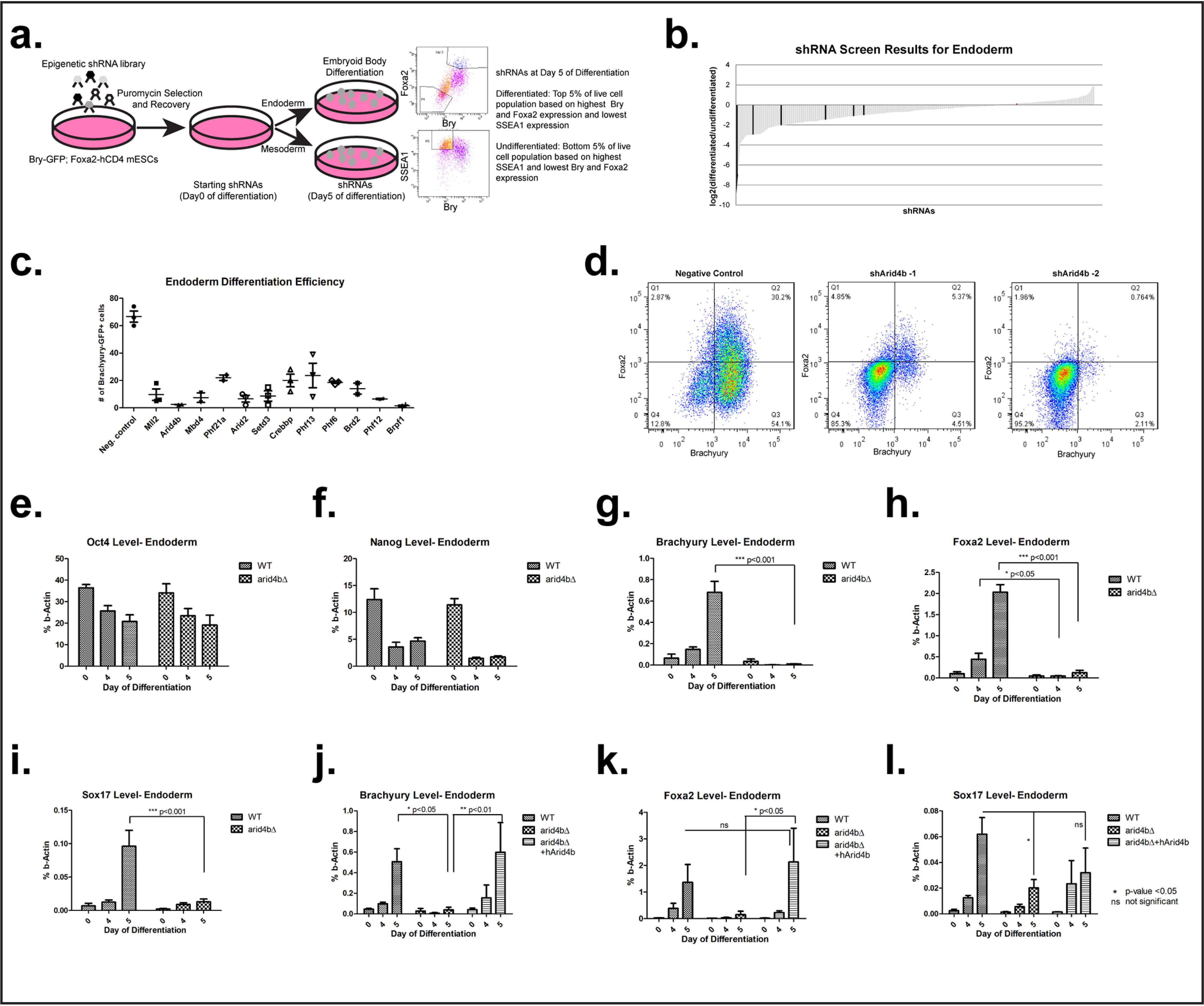

Functional RNAi screen identifies candidate chromatin factors required for endoderm and mesoderm commitment

We used a pooled shRNA library screen to identify epigenetic factors that impact mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation toward mesoderm and endoderm (Fig. 1a). The shRNA library consisted of 5 previously validated shRNAs per gene targeting ∼300 chromatin-related proteins. A Brachyury-GFP; Foxa2-hCD4 reporter mESC line was transduced at low multiplicity of infection with the pooled shRNA library, enabling single shRNA knockdown per cell. After puromycin selection of transduced mESCs, the starting (day 0) population of shRNAs was determined by DNA sequencing. Thereafter, the reporter line was directed toward mesoderm or endoderm. On day 5 of differentiation, shRNAs in the top 5% of differentiated cells (for mesoderm: highest BRACHYURY expression, for endoderm: highest BRACHYURY and FOXA2 expression, lowest SSEA1 expression) as well as the bottom 5% of undifferentiated cells (lowest BRACHYURY and/or FOXA2 expression and highest SSEA1 expression) were determined by cell sorting and DNA sequencing. The analysis was performed by comparing the enrichment of shRNAs in day 5 differentiated cells to day 5 undifferentiated cells or day 0 starting population (Fig. 1, a and b). We found that the loss of chromatin factors more frequently led to the differentiated phenotype with variable strength (Fig. 1b). However, this was to be expected for the screening design as the differentiation efficiency of WT cells was ∼70% as calculated by BRACHYURY-positive cell population on day 5 (Fig. 1c). Consistent with published data (20–26), depletion of several members of PcG and TrX complexes affected mESC differentiation (Fig. 1b). shRNAs that were depleted at least 2-fold in differentiated cell pools versus undifferentiated cell pools were selected as potential candidates and further validated by single shRNA knockdown experiments (Fig. 1c). Observed differentiation defects were similar for mesoderm and endoderm lineages (data not shown). This observation suggests that under the conditions of this screen the candidate chromatin factors might impact a common mesendodermal cell population that gives rise to both lineages.

Figure 1.

ARID4B loss leads to meso/endodermal differentiation defects. a, design of the shRNA screen. b, waterfall plot of shRNAs ranked by log2 of the enrichment score in differentiated over undifferentiated cells. Negative controls are in red (not visible since their enrichment score is close to zero) and positive controls (PcG complex members) are in black. c, endoderm differentiation efficiency is plotted as % BRACHYURY-positive cells on day 5 of differentiation. Negative control: nontargeting shRNA. d, flow cytometry data for endoderm differentiation. Negative control; nontargeting shRNA. Bry-GFP, Foxa2-hCD4 mESCs were transduced with either nontargeting or Arid4b-targeting shRNAs. After differentiation toward endoderm, expression of BRACHYURY (GFP, x axis) and FOXA2 (hCD4, y axis) were determined by flow cytometry. e–l, RT-qPCR of selected transcripts during endoderm differentiation time course in WT, arid4bΔ, or arid4bΔ cells that re-express human ARID4B.

ARID4B is essential for successful mESC differentiation toward endoderm and mesoderm

The ARID family protein ARID4B was chosen for in-depth study as its knockdown led to compromised mesoderm and endoderm differentiation. ARID family proteins exhibit DNA-binding activity with little or no sequence-specificity and display diverse functions in development and disease progression (27, 28). Arid4b and related Arid4a proteins contain a Tudor domain and a chromobarrel domain that recognizes methylated histones (29). In the adult tissues Arid4b expression is restricted to testis and important for spermatogonial development (30–32). Reactivation of expression has been reported in cancer (33–37). Deficiency of ARID4A and ARID4B results in a decrease in repressive chromatin modifications in the Prader-Willi/Angelman imprinting cluster (38). In our experiments knockdown of Arid4b with two independent shRNAs severely compromised differentiation of reporter mESCs toward mesodermal or endodermal lineages (Fig. 1, c and d), and SSEA1 remained high (Fig. S1, a and b), even with a modest decrease in the Arid4b level (Fig. S1c).

ARID4B is reported to be a component of the Sin3a corepressor complex (39, 40). Through its several protein interaction domains, SIN3A serves as a scaffold for histone deacetylases HDAC1/2 and several other proteins that regulate Hdac function and activity (41). Although the Sin3a complex was originally classified as a transcriptional repressor, more recent evidence suggests a role in transcriptional activation (42–44). In addition to Arid4b, knockdown of other members of the Sin3a complex, including Phf12, Mbd4, and Phf21a, lead to defects in commitment of mESCs to mesoderm and endoderm (Fig. 1c, Fig. S1, a and b).

To validate shRNA knockdown findings, we deleted the Arid4b gene in mESCs with CRISPR/Cas9 (Fig. S1d). Arid4b deleted mESCs expressed Oct4 and Nanog at similar levels to WT mESCs (Fig. 1, e and f, Fig. S1, e and f). Oct4 and Nanog expression was suppressed with similar kinetics as WT cells during endoderm or mesoderm commitment. Moreover, Arid4b-deleted mESCs failed to express Brachyury, Foxa2, or Sox17 during endoderm (Fig. 1, g–i) or mesoderm differentiation (Fig. S1g). Upon extension of endoderm differentiation from 5 to 8 days, we observed markedly reduced expression of Brachyury and Foxa2 in Arid4b-deleted cells (Fig. S1, h and i). Importantly, expression of human ARID4B in Arid4b-deleted mESCs rescued endoderm differentiation defect (Fig. 1, j–l, Fig. S1j). Due to this differentiation defect, we refer to arid4bΔ cells that are exposed to the same differentiation protocol as WT cells as “meso/endoderm directed” rather than “arid4bΔ meso/endoderm cells.”

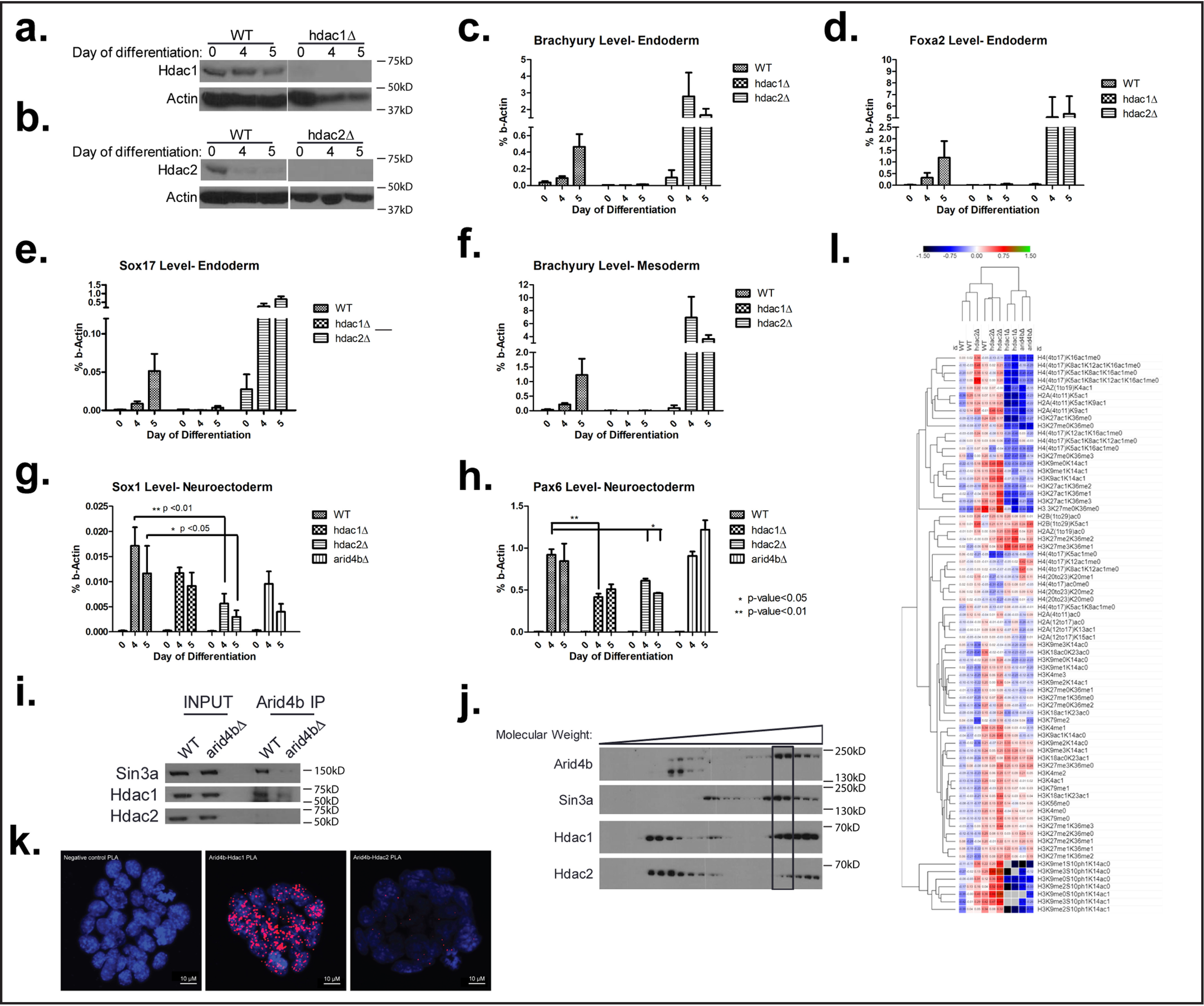

Hdac1 and Hdac2 exert different roles in lineage commitment

Given the reported presence of HDAC1 and HDAC2 (45) in Arid4b/Sin3a corepressor complexes, we tested whether the differentiation defect upon ARID4B loss is phenocopied by loss of histone deacetylase activity. First, we used a Class I HDAC inhibitor, Merck 60, which is selective toward HDAC1 and HDAC2 with IC50 of 1 and 8 nm, respectively. Histone deacetylation has key functions in maintaining a balance between self-renewal and differentiation (46–51). To prevent confounding effects of Merck 60 treatment at the ESC stage, we limited its use only to the differentiation phase. We assessed endoderm/mesoderm differentiation efficiency upon inhibitor treatment in the Brachyury-GFP; Foxa2-hCD4 reporter mESCs. Increasing concentrations of Merck 60 treatment was associated with elevated histone 3 acetylation (Fig. S2a). BRACHYURY and FOXA2 expression was reduced upon Merck 60 treatment during endoderm differentiation (Fig. S2b). However, SSEA1 levels were unchanged in DMSO or Merck 60-treated cells. Similar results were obtained for Merck 60 treatment during mesoderm differentiation (Fig. S2c).

To resolve ambiguities from inhibitor treatment, we generated independent CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Hdac1 or Hdac2 deletions in mESCs (Fig. 2, a and b). Similar to Arid4b-deleted cells, Hdac1-deleted mESCs fail to express Brachyury, Foxa2, or Sox17 during endoderm differentiation, whereas Hdac2 deletion had no evident effect (Fig. 2, c–e). Mesoderm differentiation was also defective in hdac1Δ cells (Fig. 2f). On the other hand, Nanog suppression during differentiation followed with similar kinetics in WT, hdac1Δ, and hdac2Δ cells (Fig. S2, d–f). These results are consistent with a critical role of HDAC1, but not HDAC2, in early embryogenesis (52, 53). In essence, HDAC1 loss phenocopies aspects of ARID4B deficiency.

Figure 2.

ARID4B functionally and physically interacts with HDAC1. a, validation of Hdac1 knockout by Western blotting in WT and CRISPR-mediated knockout cells during endoderm differentiation. b, validation of Hdac2 knockout by Western blotting in WT and CRISPR-mediated knockout cells during endoderm differentiation. c–e, RT-qPCR of Brachyury (c), Foxa2 (d), and Sox17 (e) during endoderm differentiation time course in WT, hdac1Δ, and hdac2Δ cells. f, RT-qPCR of Brachyury during mesoderm differentiation time course in WT, hdac1Δ, and hdac2Δ cells. g and h, RT-qPCR of Sox1 (g) and Pax6 (h) during neuroectoderm differentiation time course in WT, hdac1Δ, hdac2Δ, and arid4bΔ cells. i, coimmunoprecipitation using ARID4B antibody. Nuclear extracts from WT or arid4bΔ mESCs were used. j, cosedimentation assay using glycerol gradient centrifugation. k, PLA of ARID4B-HDAC1, ARID4B-HDAC2 in WT mESCs. Red dots depict interactions between tested proteins. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole was used to stain the nuclei. A PLA reaction without the use of primary antibodies was used as a negative control. l, proteomic analysis of histone modifications in endoderm directed WT, arid4bΔ, hdac1Δ, and hdac2Δ cells.

We next asked whether the loss of ARID4B or HDAC1 affected neuroectodermal lineage commitment. In contrast to mesoderm or endoderm differentiation, the loss of ARID4B or HDAC1 failed to affect commitment toward neuroectodermal lineage, as evidenced by the expression of Sox1, Pax6, or Jag1 marker genes (Fig. 2, g and h, Fig. S2g). We conclude that the function of ARID4B is essential for meso/endodermal commitment and dispensible for neuroectodermal lineage.

Although both HDAC1 and HDAC2 are present in the Sin3a complex, it is interesting that only Hdac1 deletion phenocopies Arid4b deletion. We tested whether this result might be due to a preferential physical interaction between ARID4B and HDAC1. We performed coimmunoprecipitation using Arid4b antibody in WT and arid4bΔ mESC nuclear extracts (Fig. 2i). As expected, ARID4B successfully immunoprecipitated SIN3A. HDAC1 was coimmunoprecipitated with ARID4B in WT nuclear extracts. Of note, HDAC2 was not detected in the pulldown with ARID4B even though it is expressed in these cells.

We then performed glycerol gradient centrifugation to analyze intact complex composition. ARID4B and SIN3A peaks coincided in high molecular weight fractions. We observed a greater proportion of HDAC1 coincided in these same fractions. Although there was some HDAC2 in these same fractions, the proportion of HDAC2 was more pronounced in lower molecular weight fractions that lacked SIN3A (Fig. 2j).

Next, we performed proximity ligation assay (PLA) to detect in situ ARID4B interaction with HDAC1 or HDAC2. This technique utilizes a pair of oligonucleotide-bound antibodies to enable continuous DNA synthesis only if epitopes are in close proximity (40 nm) and is used for intracellular visualization of protein–protein interactions. Consistent with previous results, we observed more ARID4B-HDAC1 interactions than ARID4B-HDAC2 interactions in mESCs (Fig. 2k). The majority of interactions colocalized with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, consistent of the subcellular localization and function of these proteins. A greater number of ARID4B-HDAC1 interactions were not because of differences in abundance, because HDAC1 and HDAC2 were expressed at similar levels in mESCs (Fig. S2h). These results suggest that the observed mesodermal and endodermal differentiation defect of ARID4B deficiency is associated with loss of HDAC1 activity in Sin3a complex.

arid4bΔ and hdac1Δ cells exhibit similar global histone modification profile

Next, we investigated the global chromatin profile of endoderm committed WT, arid4bΔ, hdac1Δ, and hdac2Δ cells. To this end, we performed a quantitative analysis of histone post-translational modifications by MS, which allowed for an unbiased examination of histone modifications, as well as their combinatorial constitution in each cell type. The results were normalized to WT and clustered using the Euclidean distance metric (Fig. 2l). WT cells clustered closely with hdac2Δ cells. arid4bΔ cells clustered away from WT cells and were more similar to hdac1Δ cells than hdac2Δ cells. These observations are consistent with the similarities in phenotype of ARID4B and HDAC1 loss.

Given the differentiation defect of arid4bΔ cells, it is possible that the arid4bΔ cells maintain an ESC stage histone modification profile. To test this, we compared the global histone modification profile of WT ESCs to those of endoderm-differentiated WT, arid4bΔ, hdac1Δ, and hdac2Δ cells. Interestingly, WT ESCs clustered away from endoderm-differentiated cells, regardless of the genotype (Fig. S2i). These observations support a model in which arid4bΔ cells do not remain as ESCs during differentiation but are unable to successfully execute commitment to endoderm or mesoderm lineages.

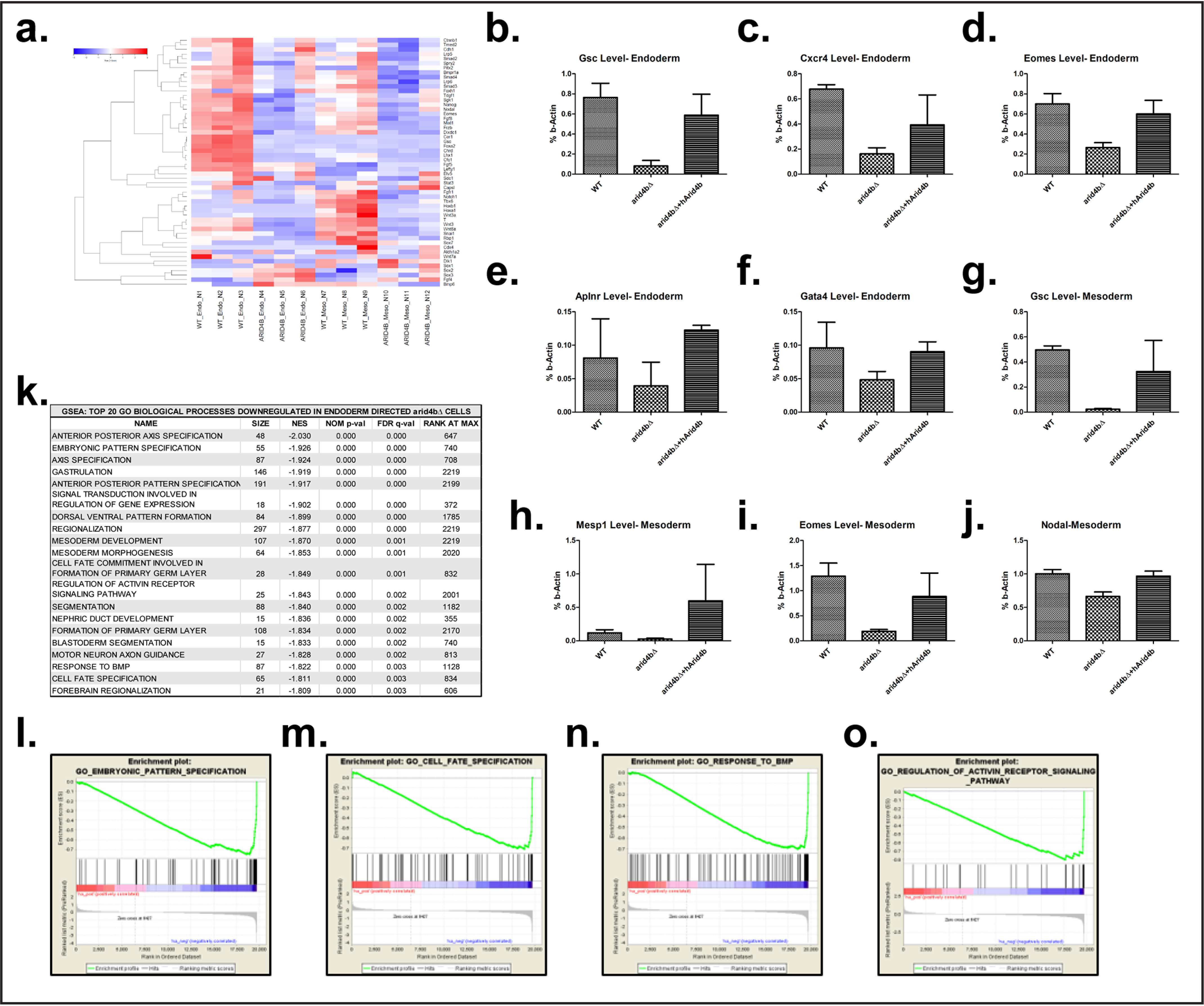

arid4bΔ cells fail to up-regulate meso/endodermal gene expression program

To further investigate the role of ARID4B in mESC lineage commitment, we conducted RNA expression profiling of WT or arid4bΔ cells directed toward mesoderm or endoderm. Hierarchical clustering of the samples showed that RNA-seq retained high reproducibility in replicates (Fig. S3a). Compared with WT cells, arid4bΔ cells showed a reduction in the expression of primitive streak and endodermal markers (Fig. 3a). Comparative analysis of transcriptomes revealed 171 genes were significantly down-regulated (fold-change > 2, adjusted p value < 0.01) in endoderm-directed arid4bΔ cells and 35 genes were up-regulated. We validated the expression of a larger set of lineage specific genes (Fig. 3, b–j). Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) demonstrated that the loss of ARID4B was associated with reduced representation of pathways related to proper lineage commitment and embryonic development (Fig. 3, k–m). Signaling pathways activated in stem cell differentiation were down-regulated in ari4bΔ cells (Fig. 3, n–o). On the other hand, type I interferon pathway and cellular viral defense response pathways were strongly activated in arid4bΔ cells (Fig. S3, b and c).

Figure 3.

Global gene expression changes upon ARID4B loss. a, RNA-seq heat map of genes related to primitive streak formation in endoderm- and mesoderm-directed WT and arid4bΔ cells. b–f, RT-qPCR of Goosecoid (b), Cxcr4 (c), Eomes (d), Aplnr (e), and Gata4 (f) transcripts during endoderm differentiation time course in WT, arid4bΔ, or arid4bΔ cells that re-express human ARID4B. g–j, RT-qPCR of Goosecoid (g), Mesp1 (h), Eomes (i), and Nodal (j) transcripts during mesoderm differentiation time course in WT, arid4bΔ, or arid4bΔ cells that re-express human ARID4B. k, biological processes down-regulated in endoderm directed arid4bΔ cells (Gene set enrichment analysis). l–o, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plot of selected biological processes that are down-regulated in endoderm-directed arid4bΔ cells.

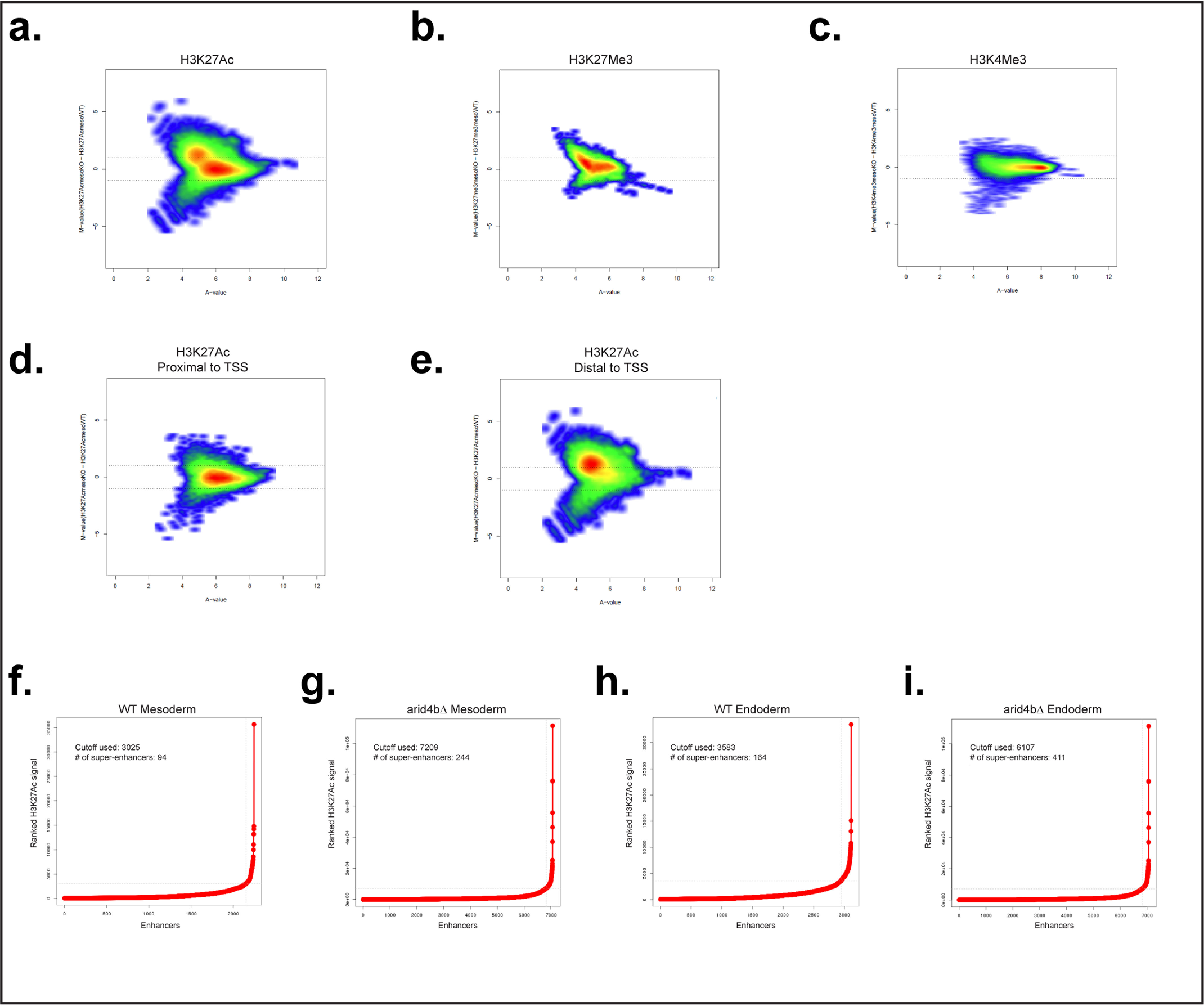

Chromatin landscape is altered upon Arid4b loss in lineage commitment

To interrogate changes in the chromatin structure of differentiating mESCs in arid4bΔ cells, we performed ChIP for the histone marks H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and H3K27Ac. We compared ChIP-seq intensities of these chromatin marks between WT and arid4bΔ cells using a quantitative algorithm called MAnorm (54). H3K27Ac signal was up-regulated in arid4bΔ mesoderm- or endoderm-differentiated cells (Fig. 4a, Fig. S4a). There was a small but notable change in H3K27me3 levels as well (Fig. 4b, Fig. S4b). In contrast, H3K4me3 peaks were largely unchanged (Fig. 4c, Fig. S4c). Further analysis of H3K27Ac signal revealed the increase to be in regions distal, rather than proximal, to the transcription start site (TSS) (Fig. 4, d and e, Fig. S4, d and e).

Figure 4.

Global chromatin landscape changes that result from ARID4B loss. a–c, MA plot for H3K27Ac (a), H3K27Me3 (b), and H3K4Me3 (c) in mesoderm-directed WT and arid4bΔ cells. Each point represents a genomic location for the signal. d and e, MA plot for H3K27Ac signal segregated based on distance to TSS (proximal, d; distal, e). f–i, H3K27Ac signal plots to identify super-enhancers for WT (f and h) and arid4bΔ (g and i) cells for mesoderm (f and g) and endoderm (h and i) lineages, x axis shows the ranked H3K27Ac signal, y axis shows the enhancers. The inflection point cutoff value of H3K27Ac signal as well as the number of identified super-enhancers are shown in each graph.

Genes responsible for a specific biological process might be coregulated through chromatin changes. Therefore, we used Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT) to identify biological processes enriched for each chromatin mark (55). Consistent with previous results, genes that lose H3K27Ac and H3K4me3 signal, and genes that gain H3K27me3 signal in mesoderm-directed arid4bΔ cells were strongly enriched in pathways related to embryonic development, pattern specification, and differentiation (Fig. S4, f–h).

H3K27 acetylation is observed in active enhancers. Super-enhancers (SE) are large clusters of enhancers that are marked by broad H3K27Ac and high concentration of transcription activators. They define cell identity by regulating the expression of key cell fate genes (56–58). Given the essential role of ARID4B in mesodermal and endodermal commitment, we assessed whether H3K27Ac changes in arid4bΔ cells correlate with any changes in SEs. We found that the number of SEs is greater in arid4bΔ cells as compared with mesoderm-differentiated WT cells (Fig. 4, f and g). There was a similar increase in the number of SEs in endoderm-differentiated arid4bΔ cells (Fig. 4, h and i). The changes in the number of SEs in arid4bΔ cells might underlie the cell fate defects. Next we analyzed the genes and pathways enriched in SEs using the GREAT database. We found that SEs unique to endoderm-differentiated WT mESCs were enriched in morphogenetic and developmental processes as well as regulation of transcription (Fig. S4i). No pathways were enriched in common SEs or arid4bΔ unique enhancers. It should also be noted that many of the common SEs exhibited increased H3K27Ac mark in arid4bΔ cells. These results indicate that developmental genes critical for endoderm development might fail to acquire H3K27Ac mark in arid4bΔ cells.

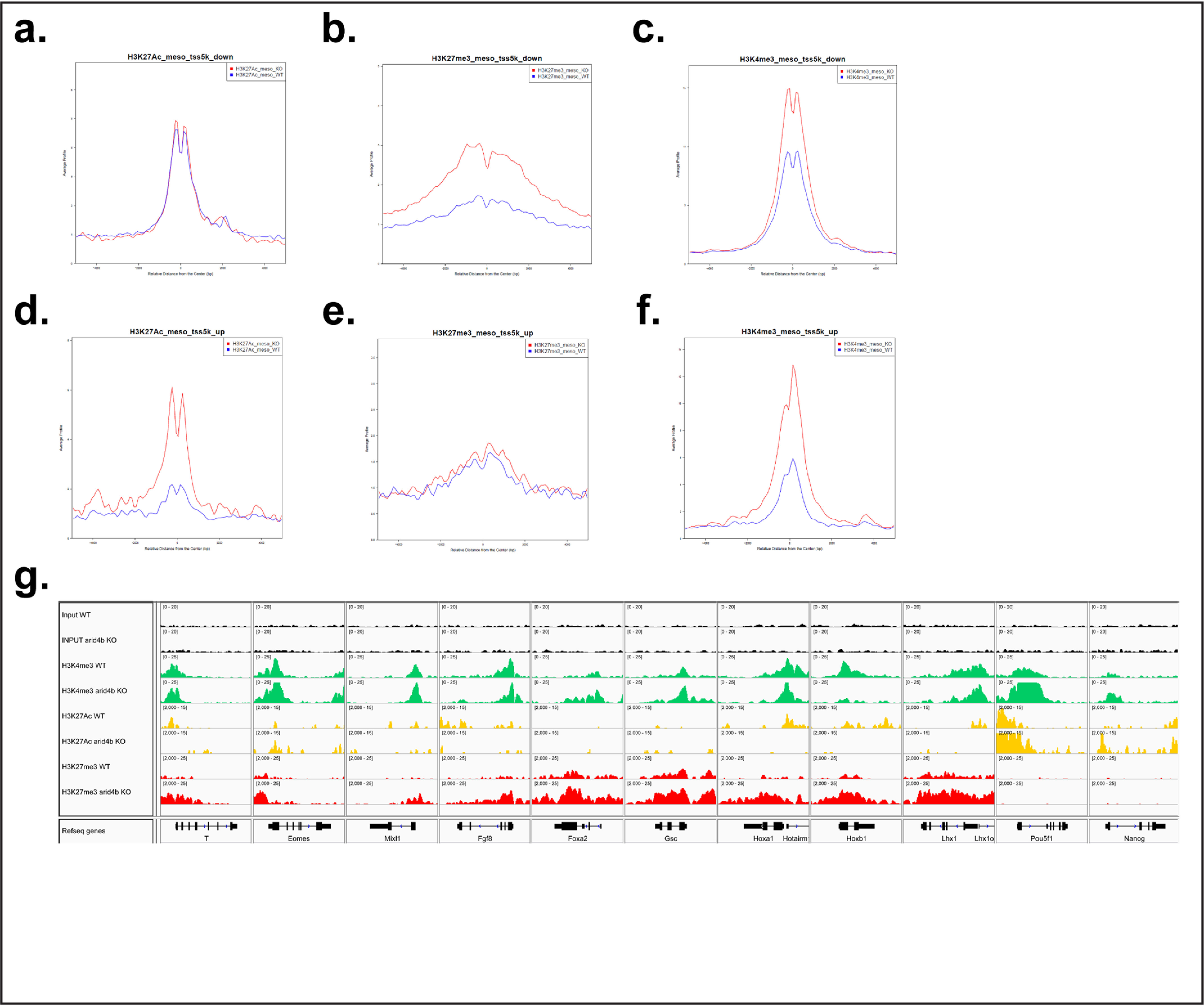

Next, we investigated a possible correlation between changes in chromatin landscape and gene expression. Using SitePro analysis, we found that the genes that are down-regulated in mesoderm-directed arid4bΔ cells show increased H3K27me3 signal around their TSS. Interestingly, higher H3K4me3 modification around TSS accompanied the H3K27me3 mark in these genes (Fig. 5, a–c). Genes that are down-regulated in endoderm-directed arid4bΔ cells had higher H3K27me3 and H3K4me3, and a pronounced decrease in H3K27Ac than WT (Fig. S5, a–c). On the other hand, up-regulated genes exhibited higher H3K4me3 and H3K27Ac mark around TSS in aridbΔ cells (Fig. 5, d–f, Fig. S5, d–f). These results indicate that the alterations in H3K27 rather than H3K4 are associated with changes in the gene expression program observed in Arid4b deficiency.

Figure 5.

Chromatin changes relevant to lineage markers in arid4bΔ cells. a–c, Sitepro analysis of H3K27Ac (a), H3K27Me3 (b), and H3K4Me3 (c) ChlP-seq on transcriptionally down-regulated genes in mesoderm-directed WT (blue) and arid4bΔ (red) cells. x axis, average signal profile; y axis, relative distance from the center (TSS). d–f, Sitepro analysis of H3K27Ac (d), H3K27Me3 (e), and H3K4Me3 (f) ChlP-seq on transcriptionally up-regulated genes in mesoderm-directed WT (blue) and arid4bΔ (red) cells. x axis, average signal profile; y axis, relative distance from the center (TSS). g, Integrative Genomics Viewer visualization of ChlP-seq tracks for selected lineage specific genes (Bry, Eomes, Mixl1, Fgf8, Foxa2, Gsc, Hoxa1, Hoxb1, and Lhx1) and ESC specific genes (Oct4 (Pou5f1), Nanog) in mesoderm-directed WT and arid4bΔ cells. y axes of WT and arid4bΔ tracks are set to the same data range.

We compared the distribution and the intensity of chromatin marks of WT and arid4bΔ cells using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). Genes required for the establishment of meso/endodermal lineage (such as Bry (T), Eomes, Mixl1, Foxa2, Gsc, Hoxa1, Hoxb1, Lhx1) were found to be generally marked with higher H3K27me3 and lower H3K27Ac throughout the gene loci in arid4bΔ cells (Fig. 5g, Fig. S5g). However, pluripotency genes Oct4 (Pou5f1) and Nanog were more strongly marked with H3K4me3 and H3K27Ac in arid4bΔ cells (Fig. 5g, Fig. S5g, last two columns).

Discussion

Prior analysis of the role of the Sin3a complex in ESC biology has led to apparently conflicting findings. Sin3a knockout results in embryonic lethality around E3.5 and 6.5 (59, 60). However, loss of the highly related SIN3B protein is lethal only later during development (61). Although Arid4a knockout mice are viable, Arid4b knockout mice die between E3.5 and 7.5 (38). Hdac1 knockout mice are similarly embryonic lethal, whereas Hdac2 deletion is viable (52, 62, 63). Although both HDAC1 and HDAC2 independently interact with SIN3A, it is unclear whether these proteins function within the same complex or are present in alternate Sin3a complexes (45). Taken together with the previous findings, our results point to a unique role of a SIN3A, HDAC1, and ARID4B containing complex in ESC biology and differentiation. We found that, similar to Arid4b deletion, the deletion of Hdac1 but not Hdac2, prevents mesoderm and endoderm differentiation. Our findings support previous reports on the role of HDAC1 in ESCs (50, 53, 64). Moreover, we observe ARID4B interaction with SIN3A and HDAC1, but not with HDAC2, despite considerable Hdac2 expression in these cells. Recently, an ESC-specific variant Sin3a complex was identified, supporting the notion that the composition of the Sin3a complex may vary among cell types and during cell differentiation (65).

A genetic perturbation of a member of a protein complex may lead to formation of residual complexes with different functional outcomes, as recently described for SWI/SNF complexes in cancer (66–68). Accordingly, the phenotype observed in arid4bΔ ESCs might be because of the function of ARID4B-less Sin3a complex rather than the complete loss of Sin3a complex function.

In endoderm-directed arid4bΔ cells, transcripts for 41 genes were up-regulated and 170 genes were down-regulated more than 2-fold (adjusted p < 0.05). Similarly, for mesoderm differentiation, transcripts for 39 genes were up-regulated and 308 genes were down-regulated in arid4bΔ cells. Although these genes represent both direct and indirect targets of the Sin3a complex, the observation that a majority of genes are down-regulated upon ARID4B loss is consistent with a role of the Sin3a complex in transcriptional activation. Indeed, evidence from yeast, Drosophila, and mammals reveal that the histone deacetylation by the Sin3a complex has a fine-tuning function for transcribed genes (42–44, 59, 69–79).

Our ChIP-seq experiments revealed critical changes associated with the loss of ARID4B during meso/endodermal differentiation, exemplified by modification at H3K27. Down-regulated genes, many of which have key developmental roles, have H3K4me3 around their TSS in arid4bΔ cells, suggesting ARID4B loss does not compromise MLL complex function. However, high H3K27me3 modification accompanies H3K4me3 and there is very little transcriptional output. These results suggest that the loss of ARID4B function might alter H3K27me3 deposition or removal in lineage-specific genes upon differentiation and might prevent their transcriptional up-regulation.

On the other hand, we observed elevated H3K27Ac mark and SEs in a subset of genes unrelated to ESC differentiation. SEs harbor a dense population of master regulators of cell fate and the Mediator complex components along with many chromatin factors (56–58). It is possible that the aberrant H3K27Ac-high SE regions in arid4bΔ cells may compete for and sequester away some of these factors required for the chromation reorganization and transcription of ESC differentiation genes.

Remodeling of the ESC cell cycle is coincident with exit from pluripotency (80, 81). Even though there appears to be a link between these two events, the notion that the change in cell cycle is directly linked to differentiation has been challenged (82, 83). ARID4A has a unique LXCXE motif that mediates interaction with pRB (27). ARID4A recruits the Sin3a corepressor complex (and thus HDAC1) to pRB targets for transcriptional suppression (84–86). This enables cell cycle control through the G1 phase. Interestingly, ARID4B lacks the LXCXE motif and is not predicted to interact with pRB. We also did not detect changes in the number of cycling ESCs or the distribution among cell cycle phases in arid4bΔ ESCs (data not shown). It is conceivable that a change in the composition of the Sin3a complex in arid4bΔ cells might indirectly affect the cell cycle. Similar changes in chromatin complex architecture and function are observed for chromatin remodeling complexes (66, 87–91).

Our Arid4b knockdown and knockout experiments resulted in protein deficiency at the ESC stage, whereas differentiation defects were observed later. Even though arid4bΔ ESCs are similar to WT ESCs on the basis of pluripotency marker expression and cell cycle analyses, we cannot rule out the possibility that the differentiation defect in arid4bΔ cells originates already at the ESC stage. A more detailed analysis of the transcriptomic changes observed in ESCs and throughout the differentiation time course is needed to identify precisely when and where ARID4B function is critical.

Experimental procedures

mESC culture and differentiation

For pooled shRNA screening, a previously established reporter mESC line was used (92) (shared by G. Keller).

mESCs were cultured in the mESC medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (Life Technologies), 0.1 mm β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 2 mm l-glutamine (Life Technologies), 0.1 mm nonessential amino acid (Life Technologies), 1% nucleoside mix (Sigma), 1,000 units/ml of recombinant leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF, Chemicon), and 50 units/ml of penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies)) on mouse-irradiated fibroblasts (CF-1, Thermo) and gelatinized tissue culture dishes.

Previously established protocols were adapted for mesoderm and endoderm differentiation (92, 93). Briefly mESC plates (day 0 of differentiation) were trypsinized and fibroblasts were removed from the mix by replating on gelatinized dishes for 30 min. The mESCs were then plated on Petri dishes to support suspension culture in differentiation base medium (75% Isocove's modified Dulbecco medium (Thermo), 25% F-12 (Thermo), 0.5% BSA (Sigma), 1% B27 without retinoic acid (Thermo), 0.5% N2 (Thermo), 1% GlutaMAX (Thermo), 10 μl/ml of zscorbic acid, 4.5 × 10−4 m monothioglycerol) at 750,000 cells/10-cm Petri dish density. After 2 days, embryoid bodies were collected and dissociated using Accutase (Sigma). Single cells were replated at 500,000 cells/6-cm Petri dish for endoderm and 750,000 cells/6-cm Petri dish for mesoderm in differentiation medium supplemented with cytokines (Activin A (75 ng/ml) for endoderm; Activin A (1 ng/ml), BMP4 (1 ng/ml), and Wnt3a (3 ng/ml) for mesoderm).

Generation of CRISPR deletion mESCs

Paired single guide RNAs were designed to limit off-target cleavage and delete critical coding exons of the selected candidate genes. mESC deletions were performed as previously described for MEL cells (94, 95). mESC clones were screened using conventional PCR and validated by Western blotting.

Generation of Arid4b rescue mESCs

Full human ARID4B cDNA was purchased from Dharmacon (clone number 40146449). HARID4B ORF was amplified with AscI and XbaI restriction sites and cloned into pEF1α-FlagBio plasmid (96). arid4bΔ mESCs were electroporated with 10 μg of plasmid using a Bio-Rad electroporator. Clones were screened with Western blotting using anti-FLAG antibody.

shRNA screen and analysis

A list of epigenetic factors was prepared through literature, chromatin-related domain homology search, and other database searches. shRNA selection and library production was done through the Broad Institute the RNAi Consortium.

Brachyury-GFP; Foxa2-hCD4 reporter mESCs were transduced by centrifugation at 2000 rpm at 37 °C for 2 h in serum-free mESC medium that contains 4 μg/ml of Polybrene. The transduced cells were immediately washed and plated in conventional mESC medium on a gelatinized tissue culture dish. Transductions were performed at >200 cells/shRNA to allow for adequate library representation. After 24 h, transduced cells were selected using 1 μg/ml of puromycin for 3-4 days. mESCs were allowed to recover for 2 days. Mesoderm and endoderm differentiations were performed as explained above. Day 0 mESC sample was taken as the starting shRNA population. At day 5 of differentiation, the top 5% of differentiated cells (for mesoderm: highest BRACHYURY expression, for endoderm: highest BRACHYURY and FOXA2 expression) as well as bottom 5% of undifferentiated cells (lowest BRACHYURY and/or FOXA2 expression and highest SSEA1 expression) were sorted on BD Aria (DFCI Flow Cytometry Core Facility). Library transductions were performed in three independent replicates. Genomic DNA was isolated from sorted cells and was sent to the Broad Institute for sequencing.

The analysis of the shRNA screen results were done using the average of the shRNAs for each gene as well as the Weighted Sum method on the GENE-E program developed by the Broad Institute. Day 5 shRNA representation was compared with day 0 mESC shRNA representation. Additionally, day 5 differentiated to undifferentiated comparison was also performed. The genes with less than three scored shRNAs were eliminated from analyses. Genes that are depleted at least 2-fold compared with the day 0 or day 5 undifferentiated population were selected as candidates. Of these candidate genes, the ones that show up in only one of the three biological replicates were eliminated. Known Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins were also discarded from further study. The final list of candidate genes were tested one by one with three independent shRNAs in mESCs for differentiation toward mesoderm and endoderm.

Flow cytometry

mESCs or differentiated cells were dissociated into single cells and stained with anti-SSEA1-Alexa Fluor 647 (eBioscience, 51-8213) and anti-human CD4-PE (eBioscience, 12-0049). Flow cytometry was performed on BD Fortessa and analyzed on FlowJo software. Cell sorting was done in DFCI Flow Cytometry Core Facility on BD FACSAria cell sorters.

RT-qPCR and RNA-seq

Cells were collected and resuspended in TRIzol (Thermo, 15596018). RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy plus kits according to provided protocols. The concentration of purified RNA samples was tested on Nanodrop. Equal amounts of total RNA (250 ng to 1 μg) was converted into cDNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, 1708890). qPCR was performed with primers listed in Table 1 and iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad) using Bio-Rad CFX96 and CFX384 machines according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′→ 3′) |

|---|---|

| Β-actin-F-qPCR | ATGAAGATCCTGACCGAGCG |

| Β-actin-R-qPCR | TACTTGCGCTCAGGAGGAGC |

| Oct4-F-qPCR | CTGAGGGCCAGGCAGGAGCACGAG |

| Oct4-R-qPCR | CTGTAGGGAGGGCTTCGGGCACTT |

| Nanog-F-qPCR | ATGAAGTGCAAGCGGTGGCAGAAA |

| Nanog-R-qPCR | CCTGGTGGAGTCACAGAGTAGTTC |

| Bry-F-qPCR | CATGTACTCTTTCTTGCTGG |

| Bry-R-qPCR | GGTCTCGGGAAAGCAGTGGC |

| Foxa2-F-qPCR | TGGTCACTGGGGACAAGGGAA |

| Foxa2-R-qPCR | GCAACAACAGCAATAGAGAAC |

| Sox17-F-qPCR | GCCAAAGACGAACGCAAGCGGT |

| Sox17-R-qPCR | TCATGCGCTTCACCTGCTTG |

| Pax6-F-qPCR | AGTGAATGGGCGGAGTTATG |

| Pax6-F-qPCR | ACTTGGACGGAAACTGACAC |

| Gsc-F-qPCR | ACCATCTTCACCGATGAGCAGC |

| Gsc-R-qPCR | CTTGGCTCGGCGGTTCTTAAAC |

| Cxcr4-F-qPCR | GGCTGTAGAGCGAGTGTTGC |

| Cxcr4-R-qPCR | GTAGAGGTTGACAGTGTAGAT |

| Eomes-F-qPCR | TGTTTTCGTGGAAGTGGTTCTGGC |

| Eomes-R-qPCR | AGGTCTGAGTCTTGGAAGGTTCATTC |

| Aplnr-F-qPCR | GGTTACAACTACTATGGGGCTGA |

| Aplnr-R-qPCR | AGCTGAGCGTCTCTTTTCGC |

| Gata4-F-qPCR | CATCAAATCGCAGCCT |

| Gata4-R-qPCR | AAGCAAGCTAGAGTCCT |

| Mesp1-F-qPCR | AATGCAACGGATGATTGT |

| Mesp1-R-qPCR | AGCGTGTACCCTATTGG |

| Nodal-F-qPCR | CCAGACAGAAGCCAACT |

| Nodal-R-qPCR | AAGCATGCTCAGTGGCT |

| Jagged1-F-qPCR | CCAGCCAGTGAAGACCAAGT |

| Jagged1-R-qPCR | TCAGCAGAGGAACCAGGAAA |

| Hdac1-F-qPCR | AAGGAGGAGAAGCCAGAAGC |

| Hdac1-R-qPCR | TCTGAGAAGTGAGGAACTTGGG |

| Hdac2-F-qPCR | ATGCAGAGATTTAACGTCGGAG |

| Hdac2-R-qPCR | TGCTTCTGACTTCTTGGCATG |

For RNA-seq, genomic DNA was eliminated in a column during RNA extraction using DNase (Qiagen, 79254). The quality of the RNA samples was tested on an Agilent BioAnalyzer (DFCI CCCB Core Facility). Libraries were prepared using New England Biolabs reagents (NEBnext ultra directional RNA library prep kit (E7420S), NEBnext rRNA depletion kit (E6310S), and NEBnext multiplex oligos for Illumina sequencing (E7335S)). The concentrations of library cDNA samples were analyzed using Qubit. Sequencing was performed using Illumina HiSeq2000.

Western blotting

WT and arid4bΔ were grown and lysed directly in 2× Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad) including β-mercaptoethanol at 95 °C for 10 min. After centrifugation to remove cell debris, equal amounts of cell lysate were loaded on 12% polyacrylamide gel. Primary antibodies (Hdac1 (06-720; Millipore), Hdac2 (sc-7899; Santa Cruz), Arid4b (A302-233A; Bethyl), α-H3Ac (06-599; Millipore), actin (Mab1501; Millipore)) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used for detection (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antibody | Company | Catalog number | Experiment used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hdac1 | Millipore | 06-720 | Western blotting |

| Hdac1 | Santa Cruz | sc-81598 | Proximity ligation assay |

| Hdac2 | Santa Cruz | sc-7899 | Western blotting |

| Hdac2 | Santa Cruz | sc-9959 | Proximity ligation assay |

| Sin3a | Active Motif | 39865 | Western blotting |

| Arid4b | Bethyl | A302-233A | Immunoprecipitation, Western blotting, proximity ligation assay |

| Histone H3K27ac | Active Motif | 39133 | ChIP |

| Histone H3K27me3 | Active Motif | 39155 | ChIP |

| Histone H3K4me3 | Millipore | 07-473 | ChIP |

| α-H3Ac | Millipore | 06-599 | Western blotting |

| SSEA-1 eFluor660 | eBioscience | 50-8813 | Flow Cytometry |

| CD4-PE | eBioscience | 12-0049 | Flow Cytometry |

| β-Actin | Millipore | Mab1501 | Western blotting |

Co-immunoprecipitation

Nuclear extracts were prepared from WT (CJ9) and arid4bΔ mESCs using the Universal Magnetic CoIP Kit (Active Motif, catalog number 54002) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For co-immunoprecipitation, kit protocol was followed. 400 μg of nuclear extract was incubated with 5 μg of anti-Arid4b (A302-233A; Bethyl) antibody. After immunoprecipitation and washes, beads were boiled in 2× Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad) supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol at 95 °C for 10 min.

Glycerol sedimentation assay

WT (CJ9) mESCs were grown and glycerol sedimentation assay was performed as previously described (67).

Proximity ligation assay

PLA was performed using DuoLink In Situ Red Starter Kit (Sigma, DUO92101) using Arid4b (rabbit, 1:250) and Hdac1 (mouse, 1:250) or Hdac2 (mouse, 1:250) primary antibodies on WT (CJ9) mESCs according to the manufacturer's protocol. Confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SP8) imaging was performed at Bilkent University UNAM Laboratories.

Histone proteomics

Quantitative analysis of histone post-translational modifications was performed in collaboration with Dr. Jacob Jaffe of the Broad Institute Proteomics Platform. WT, arid4bΔ, hdac1Δ, and hdac2Δ mESCs as well as endoderm-directed cells were collected and processed to isolate histones. The procedure was completed as described in Ref. 97. The enrichment results for each modification in knockout cells were normalized to the WT counterpart and visualized using Morpheus tool of the Broad Institute.

ChIP sequencing

ChIP was performed as previously described (96) using the following antibodies: H3K27ac (Active Motif, 39133), H3K27me3 (Active Motif, 39155), and H3K4me3 (Millipore, 07-473). ChIP-seq libraries were prepared using the NEBnext ChIP-seq library kit (E6240S) and NEBnext multiplex oligos for Illumina sequencing (E7335S) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The concentrations of library cDNA samples were analyzed using Qubit. Sequencing was performed using Illumina HiSeq2000.

RNA-seq data analysis

RNA-seq reads were aligned to the reference mouse genome mm10 using STAR (98) with default parameters. Aligned reads were counted in the genomic transcripts annotations from GenomicFeatures (99), using Rsamtools (Morgan M, 2016). DESeq2 (100) used for differentially expressed gene analysis was performed with the threshold at an adjusted p value 0.01 and fold-change 2.

ChIP-seq data analysis

ChIP-seq reads were aligned to the mm10 reference genome using Bowtie2 (101) with default parameters. Duplicate reads were removed using PICARD tools (RRID:SCR_006525). MACS2 (102) was used for ChIP-seq peaks calling MACS2 with the following parameters (–nomodel –keep-dup 1 –extsize = 146 -q 0.01). Peaks were filtered using the consensus excludable ENCODE blacklist (The ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012). MAnorm (54) was used for determining differential ChIP-seq peaks between WT and KO as previously described (103) with the threshold of M-value 1 and FDR 0.01.

Data availability

Data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus with accession numbers GSE153633) and GSE153634) (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Summary of RNA-seq data (GSE153633) generated in this study

| Sample | Raw reads | Aligned reads | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA_endo_Arid4b_rep1 | 48,861,669 | 33,558,672 | GSM4648443 |

| RNA_endo_Arid4b_rep2 | 92,513,368 | 63,011,764 | GSM4648444 |

| RNA_endo_Arid4b_rep3 | 56,781,086 | 39,324,816 | GSM4648445 |

| RNA_endo_wt_rep1 | 45,504,785 | 31,133,800 | GSM4648440 |

| RNA_endo_wt_rep2 | 74,616,171 | 50,206,366 | GSM4648441 |

| RNA_endo_wt_rep3 | 34,571,724 | 23,814,171 | GSM4648442 |

| RNA_meso_Arid4b_rep1 | 60,249,575 | 41,640,361 | GSM4648449 |

| RNA_meso_Arid4b_rep2 | 61,808,239 | 41,860,535 | GSM4648450 |

| RNA_meso_Arid4b_rep3 | 48,766,906 | 33,823,527 | GSM4648451 |

| RNA_meso_wt_rep1 | 56,017,656 | 38,469,918 | GSM4648446 |

| RNA_meso_wt_rep2 | 25,745,470 | 17,614,638 | GSM4648447 |

| RNA_meso_wt_rep3 | 67,948,168 | 45,998,987 | GSM4648448 |

Table 4.

Summary of ChIP-seq data (GSE153634) generated in this study

| Sample | Raw reads | Aligned reads | Aligned reads rmdup | Peak | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27ac_endo_Arid4b | 81,963,501 | 76,581,910 | 9,778,716 | 35,884 | GSM4648459 |

| H3K27ac_endo_wt | 47,539,489 | 45,868,810 | 18,884,143 | 14,216 | GSM4648455 |

| H3K27ac_meso_Arid4b | 49,307,346 | 45,368,018 | 9,368,799 | 22,747 | GSM4648467 |

| H3K27ac_meso_wt | 49,404,761 | 47,807,460 | 18,533,497 | 12,496 | GSM4648463 |

| H3K27me3_endo_Arid4b | 70,967,345 | 69,144,743 | 32,912,724 | 16,660 | GSM4648458 |

| H3K27me3_endo_wt | 56,464,721 | 55,101,389 | 23,397,909 | 10,326 | GSM4648454 |

| H3K27me3_meso_Arid4b | 53,621,397 | 52,172,143 | 28,569,202 | 9,863 | GSM4648466 |

| H3K27me3_meso_wt | 57,662,288 | 56,239,928 | 24,627,773 | 6,150 | GSM4648462 |

| H3K4me3_endo_Arid4b | 51,872,178 | 50,792,076 | 29,504,382 | 25,272 | GSM4648457 |

| H3K4me3_endo_wt | 52,521,226 | 51,353,318 | 24,042,979 | 22,292 | GSM4648453 |

| H3K4me3_meso_Arid4b | 51,901,859 | 50,643,552 | 31,218,452 | 26,852 | GSM4648465 |

| H3K4me3_meso_wt | 51,507,812 | 50,454,506 | 32,502,578 | 21,752 | GSM4648461 |

| Input_endo_Arid4b | 51,803,055 | 50,795,277 | 38,030,164 | GSM4648456 | |

| Input_endo_wt | 56,060,867 | 54,790,616 | 40,859,382 | GSM4648452 | |

| Input_meso_Arid4b | 52,918,141 | 51,792,208 | 39,111,202 | GSM4648464 | |

| Input_meso_wt | 56,640,634 | 55,521,376 | 44,735,823 | GSM4648460 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gordon Keller for providing the Bry-GFP; Foxa2-hCD4 mESC line and mesoderm differentiation protocol. We thank Valerie Gouon-Evans for endoderm differentiation protocol. We thank Davide Seruggia for the preparation of ChIP-seq libraries. We thank members of the Orkin lab for help with experimental protocols, sharing reagents, and critical comments.

This article contains supporting information.

Author contributions—N. T. C. and S. H. O. conceptualization; N. T. C., E. G. K., and X. W. data curation; N. T. C., J. H., and E. G. K. formal analysis; N. T. C. and S. H. O. supervision; N. T. C., J. H., E. G. K., X. W., I. E., F. C., and S. H. O. investigation; N. T. C., J. H., E. G. K., X. W., and I. E. methodology; N. T. C. writing-original draft; N. T. C. project administration; N. T. C., E. G. K., and S. H. O. writing-review and editing; J. H., E. G. K., F. C., and S. H. O. visualization; S. H. O. resources; S. H. O. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information—S. H. Orkin is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

Conflict of interest—The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- PLA

- proximity ligation assay

- TSS

- transcription start site

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- SE

- Super-enhancers

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR.

References

- 1. Orkin S. H., and Hochedlinger K. (2011) Chromatin connections to pluripotency and cellular reprogramming. Cell 145, 835–850 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morey L., Santanach A., and Di Croce L. (2015) Pluripotency and epigenetic factors in mouse embryonic stem cell fate regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 35, 2716–2728 10.1128/MCB.00266-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seruggia D., Oti M., Tripathi P., Canver M. C., LeBlanc L., Di Giammartino D. C., Bullen M. J., Nefzger C. M., Sun Y. B. Y., Farouni R., Polo J. M., Pinello L., Apostolou E., Kim J., Orkin S. H., et al. (2019) TAF5L and TAF6L maintain self-renewal of embryonic stem cells via the MYC regulatory network. Mol. Cell. 74, 1148–1163 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fraser J., Ferrai C., Chiariello A. M., Schueler M., Rito T., Laudanno G., Barbieri M., Moore B. L., Kraemer D. C. A., Aitken S., Xie S. Q., Morris K. J., Itoh M., Kawaji H., Jaeger I., FANTOM Consortium, et al. (2015) Hierarchical folding and reorganization of chromosomes are linked to transcriptional changes in cellular differentiation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 11, 852 10.15252/msb.20156492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonev B., Mendelson Cohen N., Szabo Q., Fritsch L., Papadopoulos G. L., Lubling Y., Xu X., Lv X., Hugnot J. P., Tanay A., and Cavalli G. (2017) Multiscale 3D genome rewiring during mouse neural development. Cell 171, 557–572.e24 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dixon J. R., Jung I., Selvaraj S., Shen Y., Antosiewicz-Bourget J. E., Lee A. Y., Ye Z., Kim A., Rajagopal N., Xie W., Diao Y., Liang J., Zhao H., Lobanenkov V. V., Ecker J. R., et al. (2015) Chromatin architecture reorganization during stem cell differentiation. Nature 518, 331–336 10.1038/nature14222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xie W., Schultz M. D., Lister R., Hou Z., Rajagopal N., Ray P., Whitaker J. W., Tian S., Hawkins R. D., Leung D., Yang H., Wang T., Lee A. Y., Swanson S. A., Zhang J., et al. (2013) Epigenomic analysis of multilineage differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell 153, 1134–1148 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhu J., Adli M., Zou J. Y., Verstappen G., Coyne M., Zhang X., Durham T., Miri M., Deshpande V., De Jager P. L., Bennett D. A., Houmard J. A., Muoio D. M., Onder T. T., Camahort R., et al. (2013) Genome-wide chromatin state transitions associated with developmental and environmental cues. Cell 152, 642–654 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fouse S. D., Shen Y., Pellegrini M., Cole S., Meissner A., Van Neste L., Jaenisch R., and Fan G. (2008) Promoter CpG methylation contributes to ES cell gene regulation in parallel with Oct4/Nanog, PcG complex, and histone H3 K4/K27 trimethylation. Cell Stem Cell. 2, 160–169 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fazzio T. G., Huff J. T., and Panning B. (2008) An RNAi screen of chromatin proteins identifies Tip60-p400 as a regulator of embryonic stem cell identity. Cell 134, 162–174 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hu G., Kim J., Xu Q., Leng Y., Orkin S. H., and Elledge S. J. (2009) A genome-wide RNAi screen identifies a new transcriptional module required for self-renewal. Genes Dev. 14, e8126 10.1101/gad.1769609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Das P. P., Shao Z., Beyaz S., Apostolou E., Pinello L., Angeles A. D. L., O'Brien K., Atsma J. M., Fujiwara Y., Nguyen M., Ljuboja D., Guo G., Woo A., Yuan G. C., Onder T., et al. (2014) Distinct and combinatorial functions of Jmjd2b/Kdm4b and Jmjd2c/Kdm4c in mouse embryonic stem cell identity. Mol. Cell. 53, 32–48 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee T. I., Jenner R. G., Boyer L. A., Guenther M. G., Levine S. S., Kumar R. M., Chevalier B., Johnstone S. E., Cole M. F., Isono K., Ichi, Koseki H., Fuchikami T., Abe K., Murray H. L., Zucker J. P., et al. (2006) Control of developmental regulators by polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 125, 301–313 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boyer L. A., Plath K., Zeitlinger J., Brambrink T., Medeiros L. A., Lee T. I., Levine S. S., Wernig M., Tajonar A., Ray M. K., Bell G. W., Otte A. P., Vidal M., Gifford D. K., Young R. A., et al. (2006) Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature 441, 349–353 10.1038/nature04733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bracken A. P., Dietrich N., Pasini D., Hansen K. H., and Helin K. (2006) Genome-wide mapping of polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev. 20, 1123–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ho L., Miller E. L., Ronan J. L., Ho W. Q., Jothi R., and Crabtree G. R. (2011) EsBAF facilitates pluripotency by conditioning the genome for LIF/STAT3 signalling and by regulating polycomb function. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 903–913 10.1038/ncb2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mas G., Blanco E., Ballaré C., Sansó M., Spill Y. G., Hu D., Aoi Y., Le Dily F., Shilatifard A., Marti-Renom M. A., and Di Croce L. (2018) Promoter bivalency favors an open chromatin architecture in embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 50, 1452–1462 10.1038/s41588-018-0218-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dawlaty M. M., Breiling A., Le T., Barrasa M. I., Raddatz G., Gao Q., Powell B. E., Cheng A. W., Faull K. F., Lyko F., and Jaenisch R. (2014) Loss of tet enzymes compromises proper differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Dev. Cell. 29, 102–111 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Denissov S., Hofemeister H., Marks H., Kranz A., Ciotta G., Singh S., Anastassiadis K., Stunnenberg H. G., and Stewart A. F. (2014) Mll2 is required for H3K4 trimethylation on bivalent promoters in embryonic stem cells, whereas Mll1 is redundant. Development 141, 526–537 10.1242/dev.102681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O'Carroll D., Erhardt S., Pagani M., Barton S. C., Surani M. A., and Jenuwein T. (2001) The polycomb group GeneEzh2 is required for early mouse development. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 4330–4336 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4330-4336.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pasini D., Bracken A. P., Jensen M. R., Denchi E. L., and Helin K. (2004) Suz12 is essential for mouse development and for EZH2 histone methyltransferase activity. EMBO J. 23, 4061–4071 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Voncken J. W., Roelen B. A. J., Roefs M., De Vries S., Verhoeven E., Marino S., Deschamps J., and Van Lohuizen M. (2003) Rnf2 (Ring1b) deficiency causes gastrulation arrest and cell cycle inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2468–2473 10.1073/pnas.0434312100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Collinson A., Collier A. J., Morgan N. P., Sienerth A. R., Chandra T., Andrews S., and Rugg-Gunn P. J. (2016) Deletion of the polycomb-group protein EZH2 leads to compromised self-renewal and differentiation defects in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep. 17, 2700–27141 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leeb M., and Wutz A. (2007) Ring1B is crucial for the regulation of developmental control genes and PRC1 proteins but not X inactivation in embryonic cells. J. Cell Biol. 178, 219–229 10.1083/jcb.200612127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang C., Lee J. E., Cho Y. W., Xiao Y., Jin Q., Liu C., and Ge K. (2012) UTX regulates mesoderm differentiation of embryonic stem cells independent of H3K27 demethylase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 15324–15329 10.1073/pnas.1204166109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bledau A. S., Schmidt K., Neumann K., Hill U., Ciotta G., Gupta A., Torres D. C., Fu J., Kranz A., Stewart A. F., and Anastassiadis K. (2014) The H3K4 methyltransferase Setd1a is first required at the epiblast stage, whereas Setd1b becomes essential after gastrulation. Development 141, 1022–1035 10.1242/dev.098152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilsker D., Patsialou A., Dallas P. B., and Moran E. (2002) ARID proteins: a diverse family of DNA binding proteins implicated in the control of cell growth, differentiation, and development. Cell Growth Differ. 13, 95–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Patsialou A., Wilsker D., and Moran E. (2005) DNA-binding properties of ARID family proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 66–80 10.1093/nar/gki145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gong W., Zhou T., Mo J., Perrett S., Wang J., and Feng Y. (2012) Structural insight into recognition of methylated histone tails by retinoblastoma-binding protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 8531–8540 10.1074/jbc.M111.299149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu R.-C., Zeng Y., Pan I.-W., and Wu M.-Y. (2015) Androgen receptor coactivator ARID4B is required for the function of sertoli cells in spermatogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 29, 1334–1346 10.1210/me.2015-1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu R.-C., Zeng Y., Chen Y.-F., Lanz R. B., and Wu M.-Y. (2017) Temporal-spatial establishment of initial niche for the primary spermatogonial stem cell formation is determined by an ARID4B regulatory network. Stem Cells 35, 1554–1565 10.1002/stem.2597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu R.-C., Jiang M., Beaudet A. L., and Wu M.-Y. (2013) ARID4A and ARID4B regulate male fertility, a functional link to the AR and RB pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 4616–4621 10.1073/pnas.1218318110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldberger N., Walker R. C., Kim C. H., Winter S., and Hunter K. W. (2013) Inherited variation in miR-290 expression suppresses breast cancer progression by targeting the metastasis susceptibility gene Arid4b. Cancer Res. 73, 2671–2681 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu M.-Y., Eldin K. W., and Beaudet A. L. (2008) Identification of chromatin remodeling genes Arid4a and Arid4b as leukemia suppressor genes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100, 1247–1259 10.1093/jnci/djn253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winter S. F., Lukes L., Walker R. C., Welch D. R., and Hunter K. W. (2012) Allelic variation and differential expression of the mSIN3A histone deacetylase complex gene Arid4b promote mammary tumor growth and metastasis. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002735 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cao J. N., Gao T. W., Stanbridge E. J., and Irie R. (2001) RBP1L1, a retinoblastoma-binding protein-related gene encoding an antigenic epitope abundantly expressed in human carcinomas and normal testis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93, 1159–1165 10.1093/jnci/93.15.1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang K., Ruan J., Qian Q., Song H., Bao C., Zhang X., Kong Y., Zhang C., Hu G., Ni J., and Cui D. (2011) BRCAA1 monoclonal antibody conjugated fluorescent magnetic nanoparticles for in vivo targeted magnetofluorescent imaging of gastric cancer. J. Nanobiotechnol. 9, 23 10.1186/1477-3155-9-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu M.-Y., Tsai T.-F., and Beaudet A. L. (2006) Deficiency of Rbbp1/Arid4a and Rbbp1l1/Arid4b alters epigenetic modifications and suppresses an imprinting defect in the PWS/AS domain. Genes Dev. 20, 2859–2870 10.1101/gad.1452206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Malovannaya A., Li Y., Bulynko Y., Jung S. Y., Wang Y., Lanz R. B., O'Malley B. W., and Qin J. (2010) Streamlined analysis schema for high-throughput identification of endogenous protein complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2431–2436 10.1073/pnas.0912599106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fleischer T. C., Yun U. J., and Ayer D. E. (2003) Identification and characterization of three new components of the mSin3A corepressor complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 3456–3467 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3456-3467.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grzenda A., Lomberk G., Zhang J. S., and Urrutia R. (2009) Sin3: Master scaffold and transcriptional corepressor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1789, 443–450 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reynolds N., O'Shaughnessy A., and Hendrich B. (2013) Transcriptional repressors: multifaceted regulators of gene expression. Development 140, 505–512 10.1242/dev.083105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baymaz H. I., Karemaker I. D., and Vermeulen M. (2015) Perspective on unraveling the versatility of “co-repressor” complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1849, 1051–1056 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Laugesen A., and Helin K. (2014) Chromatin repressive complexes in stem cells, development, and cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 14, 735–751 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Laherty C. D., Yang W. M., Jian-Min S., Davie J. R., Seto E., and Eisenman R. N. (1997) Histone deacetylases associated with the mSin3 corepressor mediate Mad transcriptional repression. Cell 89, 349–356 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80215-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hu G., and Wade P. A. (2012) NuRD and pluripotency: A complex balancing act. Cell Stem Cell. 10, 497–503 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yildirim O., Li R., Hung J. H., Chen P. B., Dong X., Ee L. S., Weng Z., Rando O. J., and Fazzio T. G. (2011) Mbd3/NURD complex regulates expression of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine marked genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell 147, 1498–1510 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Whyte W. A., Bilodeau S., Orlando D. A., Hoke H. A., Frampton G. M., Foster C. T., Cowley S. M., and Young R. A. (2012) Enhancer decommissioning by LSD1 during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature 482, 221–225 10.1038/nature10805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reynolds N., Latos P., Hynes-Allen A., Loos R., Leaford D., O'Shaughnessy A., Mosaku O., Signolet J., Brennecke P., Kalkan T., Costello I., Humphreys P., Mansfield W., Nakagawa K., Strouboulis J., et al. (2012) NuRD suppresses pluripotency gene expression to promote transcriptional heterogeneity and lineage commitment. Cell Stem Cell. 10, 583–594 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lee J. H., Hart S. R. L., and Skalnik D. G. (2004) Histone deacetylase activity is required for embryonic stem cell differentiation. Genesis 38, 32–38 10.1002/gene.10250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Saunders A., Huang X., Fidalgo M., Reimer M. H., Faiola F., Ding J., Sánchez-Priego C., Guallar D., Sáenz C., Li D., and Wang J. (2017) The SIN3A/HDAC corepressor complex functionally cooperates with NANOG to promote pluripotency. Cell Rep. 18, 1713–1726 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Montgomery R. L., Davis C. A., Potthoff M. J., Haberland M., Fielitz J., Qi X., Hill J. A., Richardson J. A., and Olson E. N. (2007) Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 redundantly regulate cardiac morphogenesis, growth, and contractility. Genes Dev. 21, 1790–1802 10.1101/gad.1563807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dovey O. M., Foster C. T., and Cowley S. M. (2010) Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), but not HDAC2, controls embryonic stem cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8242–8247 10.1073/pnas.1000478107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shao Z., Zhang Y., Yuan G.-C., Orkin S. H., and Waxman D. J. (2012) MAnorm: a robust model for quantitative comparison of ChIP-Seq data sets. Genome Biol. 13, R16 10.1186/gb-2012-13-3-r16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McLean C. Y., Bristor D., Hiller M., Clarke S. L., Schaar B. T., Lowe C. B., Wenger A. M., and Bejerano G. (2010) GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 495–501 10.1038/nbt.1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hnisz D., Abraham B. J., Long I., Lau A., Saint-Andre V., Sigova A. A. Hoke H. A., and Young R. A. (2013) Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 155, 934–947 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Whyte W. A., Orlando D. A., Hnisz D., Abraham B. J., Lin C. Y., Kagey M. H., Rahl P. B., Lee T. I., and Young R. A. (2013) Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 153, 307–319 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hnisz D., Schuijers J., Lin C. Y., Weintraub A. S., Abraham B. J., Lee T. I., Bradner J. E., and Young R. A. (2015) Convergence of developmental and oncogenic signaling pathways at transcriptional super-enhancers. Mol. Cell. 58, 362–370 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dannenberg J. H., David G., Zhong S., Van Der Torre J., Wong W. H., and DePinho R. A. (2005) mSin3A corepressor regulates diverse transcriptional networks governing normal and neoplastic growth and survival. Genes Dev. 19, 1581–1595 10.1101/gad.1286905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cowley S. M., Iritani B. M., Mendrysa S. M., Xu T., Cheng P. F., Yada J., Liggitt H. D., and Eisenman R. N. (2005) The mSin3A chromatin-modifying complex is essential for embryogenesis and T-cell development. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 6990–7004 10.1128/MCB.25.16.6990-7004.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. David G., Grandinetti K. B., Finnerty P. M., Simpson N., Chu G. C., and DePinho R. A. (2008) Specific requirement of the chromatin modifier mSin3B in cell cycle exit and cellular differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4168–4172 10.1073/pnas.0710285105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lagger G., O'Carroll D., Rembold M., Khier H., Tischler J., Weitzer G., Schuettengruber B., Hauser C., Brunmeir R., Jenuwein T., and Seiser C. (2002) Essential function of histone deacetylase 1 in proliferation control and CDK inhibitor repression. EMBO J. 21, 2672–2681 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Trivedi C. M., Luo Y., Yin Z., Zhang M., Zhu W., Wang T., Floss T., Goettlicher M., Noppinger P. R., Wurst W., Ferrari V. A., Abrams C. S., Gruber P. J., and Epstein J. A. (2007) Hdac2 regulates the cardiac hypertrophic response by modulating Gsk3β activity. Nat. Med. 13, 324–331 10.1038/nm1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zupkovitz G., Tischler J., Posch M., Sadzak I., Ramsauer K., Egger G., Grausenburger R., Schweifer N., Chiocca S., Decker T., and Seiser C. (2006) Negative and positive regulation of gene expression by mouse histone deacetylase 1. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 79136–7928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Streubel G., Fitzpatrick D. J., Oliviero G., Scelfo A., Moran B., Das S., Munawar N., Watson A., Wynne K., Negri G. L., Dillon E. T., Jammula S., Hokamp K., O'Connor D. P., Pasini D., et al. (2017) Fam60a defines a variant Sin3a-Hdac complex in embryonic stem cells required for self-renewal. EMBO J. 36, 2216–2232 10.15252/embj.201696307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wilson B. G., Helming K. C., Wang X., Kim Y., Vazquez F., Jagani Z., Hahn W. C., and Roberts C. W. M. (2014) Residual complexes containing SMARCA2 (BRM) underlie the oncogenic drive of SMARCA4 (BRG1) mutation. Mol. Cell Biol. 34, 1136–1144 10.1128/MCB.01372-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wang X., Lee R. S., Alver B. H., Haswell J. R., Wang S., Mieczkowski J., Drier Y., Gillespie S. M., Archer T. C., Wu J. N., Tzvetkov E. P., Troisi E. C., Pomeroy S. L., Biegel J. A., Tolstorukov M. Y., et al. (2017) SMARCB1-mediated SWI/SNF complex function is essential for enhancer regulation. Nat. Genet. 49, 289–295 10.1038/ng.3746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sen P., Luo J., Hada A., Hailu S. G., Dechassa M. L., Persinger J., Brahma S., Paul S., Ranish J., and Bartholomew B. (2017) Loss of Snf5 induces formation of an aberrant SWI/SNF complex. Cell Rep. 18, 2135–2147 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bernstein B. E., Tong J. K., and Schreiber S. L. (2000) Genomewide studies of histone deacetylase function in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13708–13713 10.1073/pnas.250477697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pile L. A., Spellman P. T., Katzenberger R. J., and Wassarman D. A. (2003) The SIN3 deacetylase complex represses genes encoding mitochondrial proteins: implications for the regulation of energy metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37840–37848 10.1074/jbc.M305996200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. De Nadal E., Zapater M., Alepuz P. M., Sumoy L., Mas G., and Posas F. (2004) The MAPK Hog1 recruits Rpd3 histone deacetylase to activate osmoresponsive genes. Nature 427, 370–374 10.1038/nature02258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang Z., Zang C., Cui K., Schones D. E., Barski A., Peng W., and Zhao K. (2009) Genome-wide mapping of HATs and HDACs reveals distinct functions in active and inactive genes. Cell 138, 1019–1031 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Baltus G. A., Kowalski M. P., Tutter A. V., and Kadam S. (2009) A positive regulatory role for the mSin3A-HDAC complex in pluripotency through Nanog and Sox2. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6998–7006 10.1074/jbc.M807670200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. van Oevelen C., Bowman C., Pellegrino J., Asp P., Cheng J., Parisi F., Micsinai M., Kluger Y., Chu A., Blais A., David G., and Dynlacht B. D. (2010) The mammalian Sin3 proteins are required for muscle development and sarcomere specification. Mol. Cell Biol. 30, 5686–5697 10.1128/MCB.00975-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ruiz-Roig C., Viéitez C., Posas F., and De Nadal E. (2010) The Rpd3L HDAC complex is essential for the heat stress response in yeast. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 1049–1062 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Terzi N., Churchman L. S., Vasiljeva L., Weissman J., and Buratowski S. (2011) H3K4 trimethylation by Set1 promotes efficient termination by the Nrd1-Nab3-Sen1 pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 31, 3569–3583 10.1128/MCB.05590-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Icardi L., Mori R., Gesellchen V., Eyckerman S., De Cauwer L., Verhelst J., Vercauteren K., Saelens X., Meuleman P., Leroux-Roels G., De Bosscher K., Boutros M., and Tavernier J. (2012) The Sin3a repressor complex is a master regulator of STAT transcriptional activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12058–12063 10.1073/pnas.1206458109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Saha N., Liu M., Gajan A., and Pile L. A. (2016) Genome-wide studies reveal novel and distinct biological pathways regulated by SIN3 isoforms. BMC Genomics 17, 10.1186/s12864-016-2428-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhu F., Zhu Q., Ye D., Zhang Q., Yang Y., Guo X., Liu Z., Jiapaer Z., Wan X., Wang G., Chen W., Zhu S., Jiang C., Shi W., and Kang J. (2018) Sin3a-Tet1 interaction activates gene transcription and is required for embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 6026–6040 10.1093/nar/gky347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dalton S. (2015) Linking the cell cycle to cell fate decisions. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 592–600 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Boward B., Wu T., and Dalton S. (2016) Concise review: control of cell fate through cell cycle and pluripotency networks. Stem Cells 34, 1427–1436 10.1002/stem.2345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Li V. C., and Kirschner M. W. (2014) Molecular ties between the cell cycle and differentiation in embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9503–9508 10.1073/pnas.1408638111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Li V. C., Ballabeni A., and Kirschner M. W. (2012) Gap 1 phase length and mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12550–12555 10.1073/pnas.1206740109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lai A., Marcellus R. C., Corbeil H. B., and Branton P. E. (1999) RBP1 induces growth arrest by repression of E2F-dependent transcription. Oncogene 18, 2091–2100 10.1038/sj.onc.1202520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lai A., Lee J. M., Yang W.-M., DeCaprio J. A., Kaelin W. G., Seto E., and Branton P. E. (1999) RBP1 recruits both histone deacetylase-dependent and -independent repression activities to retinoblastoma family proteins. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 6632–6641 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lai A., Kennedy B. K., Barbie D. A., Bertos N. R., Yang X. J., Theberge M.-C., Tsai S.-C., Seto E., Zhang Y., Kuzmichev A., Lane W. S., Reinberg D., Harlow E., and Branton P. E. (2001) RBP1 recruits the mSIN3-histone deacetylase complex to the pocket of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor family proteins found in limited discrete regions of the nucleus at growth arrest. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 2918–2932 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2918-2932.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Nitarska J., Smith J. G., Sherlock W. T., Hillege M. M. G., Nott A., Barshop W. D., Vashisht A. A., Wohlschlegel J. A., Mitter R., and Riccio A. (2016) A functional switch of NuRD chromatin remodeling complex subunits regulates mouse cortical development. Cell Rep. 17, 1683–1698 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Helming K. C., Wang X., Wilson B. G., Vazquez F., Haswell J. R., Manchester H. E., Kim Y., Kryukov G. V., Ghandi M., Aguirre A. J., Jagani Z., Wang Z., Garraway L. A., Hahn W. C., and Roberts C. W. M. (2014) ARID1B is a specific vulnerability in ARID1A-mutant cancers. Nat. Med. 20, 251–254 10.1038/nm.3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lessard J., Wu J. I., Ranish J. A., Wan M., Winslow M. M., Staahl B. T., Wu H., Aebersold R., Graef I. A., and Crabtree G. R. (2007) An essential switch in subunit composition of a chromatin remodeling complex during neural development. Neuron 55, 201–215 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kadoch C., and Crabtree G. R. (2013) Reversible disruption of mSWI/SNF (BAF) complexes by the SS18-SSX oncogenic fusion in synovial sarcoma. Cell 153, 71–85 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ho L., Ronan J. L., Wu J., Staahl B. T., Chen L., Kuo A., Lessard J., Nesvizhskii A. I., Ranish J., and Crabtree G. R. (2009) An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is essential for embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5181–5186 10.1073/pnas.0812889106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gadue P., Huber T. L., Paddison P. J., and Keller G. M. (2006) Wnt and TGF-beta signaling are required for the induction of an in vitro model of primitive streak formation using embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16806–16811 10.1073/pnas.0603916103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Nostro M. C., Cheng X., Keller G. M., and Gadue P. (2008) Wnt, Activin, and BMP signaling regulate distinct stages in the developmental pathway from embryonic stem cells to blood. Cell Stem Cell 2, 60–71 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Canver M. C., Smith E. C., Sher F., Pinello L., Sanjana N. E., Shalem O., Chen D. D., Schupp P. G., Vinjamur D. S., Garcia S. P., Luc S., Kurita R., Nakamura Y., Fujiwara Y., Maeda T., et al. (2015) BCL11A enhancer dissection by Cas9-mediated in situ saturating mutagenesis. Nature 527, 192–197 10.1038/nature15521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Canver M. C., Bauer D. E., Dass A., Yien Y. Y., Chung J., Masuda T., Maeda T., Paw B. H., and Orkin S. H. (2014) Characterization of genomic deletion efficiency mediated by clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/cas9 nuclease system in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 21312–21324 10.1074/jbc.M114.564625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kim J., Cantor A. B., Orkin S. H., and Wang J. (2009) Use of in vivo biotinylation to study protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 4, 506–517 10.1038/nprot.2009.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Creech A. L., Taylor J. E., Maier V. K., Wu X., Feeney C. M., Udeshi N. D., Peach S. E., Boehm J. S., Lee J. T., Carr S. A., and Jaffe J. D. (2015) Building the connectivity map of epigenetics: chromatin profiling by quantitative targeted mass spectrometry. Methods 72, 57–64 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Dobin A., Davis C. A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., and Gingeras T. R. (2013) STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lawrence M., Huber W., Pagès H., Aboyoun P., Carlson M., Gentleman R., Morgan M. T., and Carey V. J. (2013) Software for computing and annotating genomic ranges. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1003118 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Love M. I., Huber W., and Anders S. (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., and Salzberg S. L. (2009) Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10, R25 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Zhang Y., Liu T., Meyer C. A., Eeckhoute J., Johnson D. S., Bernstein B. E., Nusbaum C., Myers R. M., Brown M., Li W., and Liu X. S. (2008) Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Huang J., Liu X., Li D., Shao Z., Cao H., Zhang Y., Trompouki E., Bowman T. V., Zon L. I., Yuan G. C., Orkin S. H., and Xu J. (2016) Dynamic control of enhancer repertoires drives lineage and stage-specific transcription during hematopoiesis. Dev. Cell. 36, 9–23 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus with accession numbers GSE153633) and GSE153634) (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Summary of RNA-seq data (GSE153633) generated in this study

| Sample | Raw reads | Aligned reads | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA_endo_Arid4b_rep1 | 48,861,669 | 33,558,672 | GSM4648443 |

| RNA_endo_Arid4b_rep2 | 92,513,368 | 63,011,764 | GSM4648444 |

| RNA_endo_Arid4b_rep3 | 56,781,086 | 39,324,816 | GSM4648445 |

| RNA_endo_wt_rep1 | 45,504,785 | 31,133,800 | GSM4648440 |

| RNA_endo_wt_rep2 | 74,616,171 | 50,206,366 | GSM4648441 |

| RNA_endo_wt_rep3 | 34,571,724 | 23,814,171 | GSM4648442 |

| RNA_meso_Arid4b_rep1 | 60,249,575 | 41,640,361 | GSM4648449 |

| RNA_meso_Arid4b_rep2 | 61,808,239 | 41,860,535 | GSM4648450 |

| RNA_meso_Arid4b_rep3 | 48,766,906 | 33,823,527 | GSM4648451 |

| RNA_meso_wt_rep1 | 56,017,656 | 38,469,918 | GSM4648446 |

| RNA_meso_wt_rep2 | 25,745,470 | 17,614,638 | GSM4648447 |

| RNA_meso_wt_rep3 | 67,948,168 | 45,998,987 | GSM4648448 |

Table 4.

Summary of ChIP-seq data (GSE153634) generated in this study

| Sample | Raw reads | Aligned reads | Aligned reads rmdup | Peak | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K27ac_endo_Arid4b | 81,963,501 | 76,581,910 | 9,778,716 | 35,884 | GSM4648459 |