Abstract

Internet of Things (IoT) technology has recently been integrated with various healthcare devices to monitor patients’ health status and share it with their healthcare practitioners. Since healthcare data often contain personal and sensitive information, healthcare systems must provide a secure user authentication scheme. Recently, Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al. and Sharma and Kalra proposed a lightweight protocol using hash function encryption only for user authentication on wireless sensor systems. In this paper, we found some weaknesses in target schemes. We propose a novel three-factor lightweight user authentication scheme that addresses these weaknesses and verifies the security of the proposed scheme using a formal verification tool called ProVerif. In addition, our proposed scheme outperforms other proposed symmetric encryption-based schemes or elliptic curve-based schemes.

Keywords: authentication, WSN, healthcare, IoT

1. Introduction

Digital healthcare services have recently received a considerable amount of attention as various Internet-enabled wearable devices have been deployed. Digital services can also be used to continuously monitor patients and share information with their healthcare practitioners. According to a Spyglass Consulting Group’s report [1], with 100 interviewees working in medical informatics and healthcare IT technology areas, about 88% of hospitals and healthcare systems have considered adopting remote patient monitoring (RPM) as their primary business model in the future.

RPM technology is increasingly used by hospitals and medical systems [1]. We believe that continuous monitoring and fast response times are necessary for high-risk patients with chronic diseases. For example, practitioners can use a monitoring device to collect ECG signals from patients with heart-related conditions and quickly identify any suspicious changes [2,3,4,5]. Because such data (e.g., raw ECG signals) are often highly personal and sensitive, any data that have been collected in healthcare systems should be securely protected and accessible only to authorized users such as primary care physicians. Furthermore, the scheme to monitor and analyze processes should not only be safe, but also be completed in real-time because patients might otherwise be at risk.

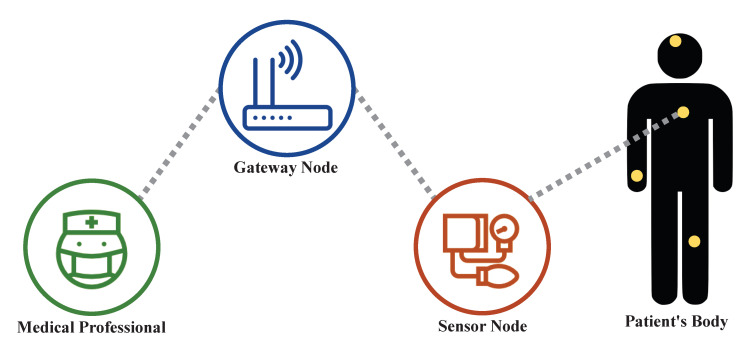

If there is a problem with the certification of these RPM technologies, the following damage can occur. First, if hospitals do not provide fast enough authentication using a heavy enough operation, quick feedback is impossible when monitoring the patient’s condition. In such cases, in a situation where urgent patients with fatal internal injuries require immediate treatment due to rapid changes, the treatment may be delayed due to the late certification speed. In the worst-case scenario, the treatment of patients can be difficult. Second, if there is a security flaw in the certification, privacy infringement of patients and medical personnel may occur. For example, if a session key is released, all medical information of the patient can be disclosed to the hacker. Therefore, in order to avoid such damage, a certification protocol is shown in Figure 1 that satisfies both high speed (i.e., lightweight computation) and safety should be used.

Figure 1.

The Architecture of User Authentication for Digital Healthcare Services.

Many security protocols (e.g., [6,7,8,9]) have been developed to satisfy these security and performance requirements. Among those protocols, Sharma and Kalra’s scheme [6] is specifically designed to improve the protocol’s efficiency. Unlike existing protocols that require expensive cryptographic operations or three authentication factors [7,9,10], Sharma and Kalra’s scheme [6] uses hash functions with only two authentication factors. Similarly, Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al. [11] also proposed a protocol using hash functions only. Sharma and Kala’s scheme [6] and Adavoudi-Jolfei et al.’s scheme [11] are the most recently written lightweight authentication protocols that can keep high speed and safety, the conditions required by the healthcare system.

In this paper, we confirmed that Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s scheme [11] has a severe vulnerability. We also demonstrate that Sharma and Kalra’s scheme [6] has a serious design error. Therefore, we propose a new scheme to fix the weaknesses of these target schemes. We formally verify the security of the new protocol using ProVerif, an automatic cryptographic protocol verifier. In summary, this paper presents the following contribution:

We demonstrate that Sharma and Kalra’s scheme [6] has a serious design error: mutual authentication between a practitioner and a sensor cannot be ensured in their original protocol.

We confirm that Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s scheme [11] and Sharma and Kalra’s scheme have a severe vulnerability. We find that Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s scheme [11] is vulnerable to user impersonation attack and session key attack. We also find that Sharma and Kalra’s scheme [6] is vulnerable to password guessing attack, stealing the session key and sensor impersonation attack.

We propose a scheme for smart healthcare systems. Our new scheme resists privileged insider attack, outsider attack, offline ID guessing attack, online id guessing attack, session key disclosure attack, practitioner impersonation attack, and sensor impersonation attack. We provide security proofs.

We formally verify the security of the new protocol using ProVerif, an automatic cryptographic protocol verifier.

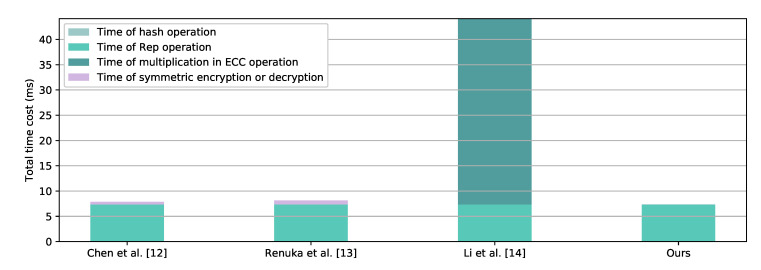

We show the performance analysis of the proposed scheme. We compared the proposed scheme with that of Chen et al. [12], Renuka et al. [13], and Li et al. [14] to show how efficient our proposed scheme is.

The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows: Section 2 describes related work. Section 3 introduces the preliminary knowledge necessary to understand the scheme by Sharma and Kalra and Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al. The target schemes are briefly described in Section 4. Section 5 discusses several weaknesses of the target schemes. We propose our improved scheme in Section 6 and show the security analysis of the proposed scheme in Section 7. In Section 8, we show the performance analysis of the proposed scheme. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Various user authentication schemes have been proposed for smart healthcare applications.

Hu et al. [15] proposed a real-time hardware and software-based healthcare monitoring system for cardiac patients in 2007. The proposed scheme focuses on efficiency improvements but lacks adequate security protection. Malasri et al. [16] proposed an authentication scheme for wireless mote-based medical sensor networks using an ECC (elliptic curve cryptography) system in 2009. However, the scheme cannot withstand denial-of-service and relay nodes attacks. Furthermore, ECC may be too expensive for embedded devices in the medical domain.

In 2012, Kumar et al. [17] proposed a two-factor user authentication scheme for wireless medical sensors to monitor patients’ health status. However, Khan and Kumari [18] found that Kumar et al.’s scheme is vulnerable to security attacks. The scheme included the use of a smart card to enhance the security of the protocol, but the user information stored on the smart card can end up leaked if the smart card is stolen. Khan and Kumari proposed an improved scheme to fix the security flaws of the previous scheme in 2014. Li et al. [19] and Wu et al. [20] each analyzed the scheme presented by Khan and Kumari [18]. They discovered that Khan and Kumari’s scheme is not secure against offline password guessing attacks, as it does not identify invalid input and user impersonation attacks. Li et al. [19] and Wu et al. [20] proposed their respective improved schemes, which employ a smart card to overcome the security flaws of Khan and Kumari [18]. Hossain et al. [21] proposed an IoT-based ECG health monitoring service framework in the cloud. They presented a framework for secure transmission of patients data from different sensors to the cloud in a wireless environment.

Recently, Sharma and Kalra [6] proposed an authentication scheme for cloud-IoT-based remote patient healthcare monitoring services. It is efficient because only the hash function is used for system encryption. Several papers briefly addressed security flaws of Sharma and Karla’s scheme [22,23]. However, they only mentioned briefly that privileged insider attacks are possible. However, we have pinpointed the structural problems of Sharma and Kalra’s scheme, and showed that password guessing attack, stealing the session key attack, and sensor impersonation attack are possible in the case of privileged insider attack.

In 2016, Gope et al. [24] proposed a novel two-factor lightweight anonymous authentication protocol in WSNs (wireless sensor networks) that uses a database to overcome prior vulnerabilities. However, Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al. [11] argue that protocol is vulnerable to side-channel attacks because of the use of 2-factors, and that the session keys are also vulnerable. To overcome these drawbacks, in 2019, Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al. [11]. proposed a new 3-factor authentication protocol in WSN. Unfortunately, Shin and Kwon found user collusion attacks, desynchronization attack and no sensor node anonymity. In addition, through our prior research, we found more weaknesses that user impersonation attack and session key attack are able to take advantage of.

3. Preliminaries

This section introduces the hash function, fuzzy extractor and threat model used in this paper.

3.1. Hash Function

Data convert an arbitrary value to a fixed-length value through a hash function. This is useful for fast and safe search functions. The hash function has the following properties [25].

Preimage-resistance It is computationally impossible to use the output of any hash value to find the input that results in this value, i.e., to find any preimage such that when given any b for which a corresponding input is not known.

2nd-preimage-resistance For any input, when there is an output for the hash function, it is computationally impossible to find another input value with this output, i.e., to find a 2nd-preimage such that .

Collision resistance It is computationally infeasible to find two different inputs with the same hashing result, i.e., any two distinct inputs a, , which hash to the same output, such that .

3.2. Fuzzy Extractor

Biometric information should be treated as sensitive. Since biometric information is unique to the user, it is convenient to use, but difficult to handle. In general, biometrics cannot be recognized equally each time. Therefore, a fuzzy extractor is used to recognize varied biometric information within a certain tolerance range. The fuzzy extractor can obtain a unique string using error tolerance. The fuzzy extractor operates through two procedures (, ), as follows [26,27]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

and are a probabilistic generation function and a deterministic reproduction function, respectively. returns a factored out string for the input biometrics B and a co-adjutant string . is a function that restores to , and any vector close to B.

3.3. Threat Model

Based on the work of Dolev and Yao [28] and other previous research [10,29], we employ a threat model with the following assumptions.

An attacker can steal a smart device with the user’s identity.

An attacker can eavesdrop on a public channel. An attacker can steal the message between the user and the gateway node or between the gateway node and the sensor node.

An attacker can extract the information stored in the smart device as a side-channel attack.

4. Review of Target Protocols

This section describes the target protocols.

4.1. Review of Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s Protocol

This section describes the protocol developed by Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al. [11]. The scheme consists of four phases: registration, login, authentication, and password change. The notation for the target paper [11] is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notations.

| Notations | Description |

|---|---|

| U | The user |

| P | The practitioner who is a medical professional |

| Gateway node | |

| Sensor node | |

| U’s identity | |

| U’s password | |

| U’s biometric information | |

| U’s disposable identity | |

| U’s shadow identity | |

| Set of access rights mask for U | |

| G | Group identity set of U |

| Biometric information of the practitioner P | |

| Identity of the practitioner P | |

| Password of the practitioner P | |

| Masked password of the user P | |

| ’s identity | |

| w | ’s private key |

| The secret emergency key between U and | |

| The secret key between U and | |

| ’s identity | |

| The secret key between and | |

| The session key between U and | |

| Smart card or smart device | |

| Database | |

| Timestamp sequence | |

| Masked password of the user P | |

| K | Secret key of |

| One-way hash function | |

| The timestamp | |

| Current timestamp | |

| A probabilistic generation function | |

| A deterministic reproduction function | |

| Maximum transmission delay | |

| ⊕ | XOR operation |

| ‖ | Concatenation operation |

4.1.1. Registration Phase

In the registration phase, U and in the private channel exchange secret information about . When the user authenticates, this allows confidential information to be stored in the database used by and .

User U chooses his/her identity and sends the registration request and personal credential to the gateway node in the secure channel.

-

The gateway node generates a random number , a unique random number used to identify a particular access group , a random number user access privilege mask and random sequence number . Then, the created variables are grouped as , , , , , . After obtaining the registration request from user U, calculates as follows:

()

()

, ,

()

, ,

, ,

()

()

()

()

()

() using its secret key w.

The data are saved (, ), , , , , in . sends , (, ), , , h to user U in .

-

After user U takes from the , chooses his/her , password , imprints the biometric and then computes as follows:

,

(

(h ( ( ())

(h )

(h ), (h )

Moreover, save the data , , (, ), , , , (, (, h ( in .

4.1.2. Login Phase

In the login phase, the user enters his/her confidential information into the smart card and requests login.

U inserts the smart card and enters , and . The smart card computes (, , and checks the condition . If it holds, the smart card ensures that the user successfully passes the verification process. Otherwise, this phase terminates immediately.

-

After successful verification, user U generates random number and the system computes as follows:

(h ( ( (

(

If there is a loss of synchronization, user U selects one of the unused pair of (, ) from (, ) and surrenders his/her , , and computes , , and .

U sends the login request messages , , , , , to .

4.1.3. Authentication Phase

In the authentication phase, verifies U with the login message received from U, and sends a new message containing secret information to . and U share their keys and exchange the secret information.

-

After receiving the login request messages from user U, first checks the validity of the transaction sequence number . computes as follows:

(

() that and are in .

Then, calculates , and checks if and are valid. If the verification of is successful, then calculation continues. Otherwise, terminates the session. generates a session key and time stamp T and calculates as follows:

, and

Finally, sends the messages , , , T, to the sensor node .

-

Upon receiving the message , assess the validity of T. If it is not valid, disconnects the session. If it is valid, also verifies . If this condition is not satisfied, disconnects the session. If it is satisfied, computes as follows:

and generates a new time stamp .

,

and

Finally, transmits , , to .

-

The gateway node checks that the time stamp and . If not, it terminates the connection. generates a random number and calculates as follows:

)

updates and . If cannot find in , generates a random number and calculates . Then, updates and then sends the messages , , , to the user U.

When user U obtains the message , the protocol checks its validity. If there is no abnormality, the system proceeds to the next step or ends the session. Furthermore, U computes , , and then updates and .

U and have successfully shared . responds to user U’s query according to stored for user U using session key . Finally, at the end of this phase, removes from storage for security reasons.

4.1.4. Password and Biometrics Change Phase

The protocol uses the following steps to change the user’s password:

U puts his/her smart card into the terminal and inserts , previous password and previous biometric . U then inputs the new password and new biometric .

-

The smart card computes , and retrieves , , , G and . The smart card continues to compute as follows:

-

The smart card computes , , , , and , as shown below.

,

Finally, the smart card replaces with , with , with , with , with and with .

4.2. Review of Sharma and Kalra’s scheme

This section briefly describes Sharma and Kalra’s scheme. The notation of the scheme is summarized in Table 1. Sharma and Kalra’s scheme consists of five different phases:

Setup Phase: The registration center sets up the parameters.

Registration Phase: The practitioner registers with his/her identity and password.

Login Phase: The practitioner logs in with his/her identity, password and smart device.

Authentication Phase: The practitioner and sensor node mutually authenticate.

Password Change Phase: The practitioner inputs identity, password and smart device, and changes his/her old password to the new password.

4.2.1. Setup Phase

The gateway node obtains its secret key K from the registration center. The center also computes and gives to the sensor node . and K are stored in and .

4.2.2. Registration Phase

The practitioner creates his/her identity and password. He/she registers through the gateway node to receive a smart device. The detailed process is as follows:

Practitioner P chooses his/her and and generates random number R, computes the masked password . Finally, he/she sends the registration message , to the gateway node .

After the gateway node receives the message from the practitioner, it computes variables , , and . After calculation, sends the smart device , c, to P.

P stores , c, d, in .

4.2.3. Login Phase

When the practitioner enters his/her identity and password, the smart device checks that the practitioner is an authorized party. The procedure for doing so is as follows:

P inputs his/her identity and password in his/her smart device.

computes , and compares a to . If the two are not the same, P fails to login.

4.2.4. Authentication Phase

We describe the mutual authentication of the practitioner’s login information and the sensor node. The procedure is as follows:

If P successfully logs in, computes , , . selects a random nonce N, and calculates , . Finally, posts the message , , , , to .

-

checks that the timestamp . means maximum transmission delay. If it is in range, chooses a random nonce M and computes:

Finally, sends the message , , , , , , , to the sensor node .

-

checks the validity of . If it is valid, continues as follows:

,

,

,

Finally, posts the message , , , , to .

-

checks the timestamp , and if it is valid, computes as follows:

At the end of the computation, sends the message , , , , to P.

P checks the timestamp . If it is in range, P computes . It also computes , and .

4.2.5. Password Change Phase

The practitioner should be able to change his/her password if he/she wants to do so (e.g., for security reasons or because of a lost password). The procedure is as follows:

P inputs his/her and to .

computes , . verifies that : if so, it computes , . Finally, sends the message to P.

P inputs his/her new password to .

computes , , , . Finally, replaces , c, with , , .

5. Analysis of Target Schemes

5.1. Analysis of Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s Scheme

In this section, we prove that the scheme put forth by Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al. [11] has some security vulnerabilities. The details are as follow.

5.1.1. Loss of Smart Card Information

Attacker can easily decrypt the information on the in the following two cases. The first case is an insider attack in the registration phase, while the second case is loss of synchronization in the login phase. Insider attack is the stronger of the two: it should be considered when there is no apparent loss of synchronization.

Insider Attack

In the registration phase, Attacker extracts the smart card when sends information to U. He/she can then read the information stored on the , , , , G, h that is not encrypted.

Loss of Synchronization

An attacker steals U’s smart card , which contains sensitive information , , (, ), , , , (, (, h (.

-

In the loss of synchronization case, can thus see the user’s login message , , , , , . computes as follows:

5.1.2. User Impersonation Attack

Attacker can carry out a user impersonation attack (the victim is assumed to be U). The details are as follows.

-

generates random numbers and computes:

, , and from and obtained from the stolen smart card attack.

transmits the login request , , , , , to the gateway node .

-

After obtains the login request from , first, it verifies and calculates:

(

()

checks if and is valid. does not detect the presence of the attacker. Unfortunately, still believes it is in communication with U.

As a result, attacker will be verified as by user U. Therefore, the user impersonation attack is successful.

5.1.3. Session Key Attack

Assume that Attacker has access to the . At this time, Attacker can extract the session key of user U and sensor node as follows.

Assume that attacker can access the database (, ), , , , , . He/she will use the data .

-

Attacker extracts the message , , , T, and calculates:

Thus, attacker has successfully seized the session key .

This result shows that Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s scheme does not satisfy the requirement of key security.

5.2. Analysis of Sharma and Kalra’s Scheme

5.2.1. Design Error in Sharma and Kalra’s Scheme

There is a fatal error in Sharma and Kalra’s paper. The design of their scheme is wrong. During the authentication phase of their scheme, the session keys computed by and are not identical. If the session key is not the same, when authentication is finished and the message is transmitted, there is a problem, because encryption is not properly performed. That is, mutual authentication would be processed incorrectly. We describe this problem in detail.

is the session key that the practitioner generates. is the session key that calculates. When sending and receiving messages later, this session key is encrypted.

In this phase, , but . Therefore, the session keys computed by and are not the same. Therefore, the authentication phase should be changed as follows.

If P logs in successfully, computes , , . selects a random nonce N and calculates , . Finally, posts the message , , , , to .

checks the timestamp . If it is in range, computes and chooses a random nonce M. continues to calculate and . Finally, sends the message , , , , , , , to the sensor node .

-

checks the validity of . If it is valid, continues the operation and checks that . keep calculating as follows:

Finally, sends the message , , , , to .

-

checks the timestamp and if it is valid, computes as follows:

At the end of the computation, sends the message , , , , to P.

P checks the timestamp . If it is in range, it computes . It also computes , and .

In addition to pointing out the correctness problem in Sharma and Kalra’s scheme, as discussed in Section 5.2.1, we demonstrate several attack methods that are fatal to the scheme. We describe the methods in detail as follows:

5.2.2. Password Guessing Attack

In the registration phase, if Attacker masquerades as , then he/she can easily obtain P’s . is hashed only once in with R. We assume that R can be extracted from the smart device, and the attacker knows the target user’s identity. Moreover, then, Attacker knows the practitioner P’s , and he/she can extract the information in using reverse engineering or a side-channel attack.

Attacker extracts a and R from P’s smart device .

compares a and , so that he/she can guess the password in a brute force attack.

Easily guessing a password implies knowing the practitioner’s identity and likely, passwords, and having access to his/her smart device, so it is virtually the same as a practitioner. This process can also be used to pretend to be a medical professional and directly engage with the patient’s healthcare-related information.

In order to make passwords difficult to guess, the authentication process should involve more robust data encryption.

5.2.3. Stealing the Session Key

We found that the session key can be extracted if attacker used attacks Section 5.2.2. The details are as follows.

computes , .

steals the message and extracts , . Then, he/she calculates .

also steals and in and computes .

Finally, he/she finds the session key .

now has the session key to use in future messages. This session key allows attackers to check the messages. This process is a serious breach of confidentiality.

5.2.4. Sensor Impersonation Attack

A sensor impersonation attack is also possible. Since only assesses the validity of the timestamp to check the sensor separately, the attacker can impersonate the sensor by sending just the timestamp. This attack generates meaningless data and wastes time.

6. Proposed Scheme

To address the problems of Sharma and Kalra’s scheme and Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s scheme, we propose a three-factor-based authentication scheme. We specifically introduce a new factor that is based on the practitioner’s biometrics data. In addition, our scheme contains a procedure to validate both and the sensor. The flow of the entire scheme is shown in the Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Proposed Scheme (Overall Algorithm Flow) |

|

6.1. Setup and Registration Phase

6.1.1. Setup Phase

In the setup phase, the gateway node gets its secret key K from the registration center. The center also computes and gives it to the sensor node . and K are stored in and .

6.1.2. Registration Phase

The practitioner creates his/her identity and password, and then registers them via the gateway node to receive a smart device. This is summarized in the Algorithm 2. The detailed procedure is as follows:

Practitioner P chooses his/her identity , password and imprints over a device for biometrics collection, and calculates a biometric information of the practitioner P like (, . He/she generates random number R and computes the masked password . Finally, he/she sends the registration message , to the gateway node .

-

After the gateway node obtains the message from the practitioner, it computes as follows:

,

After calculation, sends the smart device , c, to the practitioner P.

P stores , c, d, R, , , , in the smart device .

| Algorithm 2 Proposed Scheme (Registration Phase) |

|

6.2. Login and Authentication Phase

6.2.1. Login Phase

When the practitioner enters his/her identity and password, the smart device checks whether the practitioner is an authorized party. This phase is summarized in the Algorithm 3. The detailed procedure is as follows:

P inputs his/her identity , password and biometric information in his/her smart device.

-

The smart device executes the biometric information = (, ). computes masked password and the value a as follows:

If a and are not the same, P fails to login.

| Algorithm 3 Proposed Scheme (Login Phase) |

|

6.2.2. Authentication Phase

The practitioner’s login information and the sensor node execute a mutual authentication process. This phase is summarized in Algorithms 4–6. The procedure is as follows:

-

If P logs in successfully, selects a random nonce N and computes as follows:

Finally, sends the message , , , , to .

-

checks the timestamp . If it is in range, computes as follows:

also checks . If it is valid, chooses a random nonce M and computes as follows:

Finally, sends the message , , , , , , , to the sensor node .

-

checks the validity of . If it is valid, continues the operation and checks . computes as follows:

It also checks the validity of . If it is valid, computes:

,

,

Finally, sends the message , , , to .

-

checks the timestamp and if it is valid, computes:

and checks . If it is also valid, computes:

At the end of the computation, sends the message , , , , to P.

P checks the timestamp . If it is in range, P computes and checks . P also computes , and checks .

| Algorithm 4 Proposed Scheme (P’s Authentication Phase) |

|

| Algorithm 5 Proposed Scheme (GWN’s Authentication Phase) |

|

| Algorithm 6 Proposed Scheme (SN’s Authentication Phase) |

|

6.3. Password Change Phase

The practitioner can change his/her password. The procedure is as follows:

P inputs his/her identity , password and biometric information in his/her smart device.

The smart device executes (, ) = . computes , . checks . If so, it computes , . Finally, sends the message to P.

P inputs his/her new password to the smart device .

computes , , , . Finally, replaces , c, with , , .

7. Security Analysis

In this section, we analyze the security of the proposed scheme in two ways: formal security analysis and informal security analysis. We use a formal protocol verification tool called ProVerif in Section 7.1, to demonstrate the security of our scheme. We also provide a theoretical security analysis of the protocol in Section 7.2. Through this verification, we have demonstrated how safe our scheme can be in reality.

7.1. Formal Security Analysis

We use ProVerif to analyze the security and correctness of our scheme; ProVerif is widely used to verify security protocols [7,30,31]. ProVerif is a software tool that formally verifies the security of cryptographic protocols. We define basic cryptographic primitives such as hash function, encryption, digital signature and bit-commitment.

We used three channels: a registration channel (), a practitioner–gateway node channel () and a gateway node–sensor node channel (). The variables, constants, secret key, functions and events are defined in Table A1.

The “Registration” and “Login and Authentication” phases for practitioners are shown in Table A2. The “Registration” and “Authentication” phases for gateway nodes are shown in Table A3. The “Authentication” phase for sensor nodes is shown in Table A4. Table 2 and Table 3 show a query and the corresponding query results.

Table 2.

Query.

| (*—-queries—-*) |

| query attacker(IDp). |

| query id:bitstring; inj-event(endP(id)) ==> inj-event(beginP(id)). |

| query id:bitstring; inj-event(endGWN(id)) ==> inj-event(beginGWN(id)). |

| query id:bitstring; inj-event(endS(id)) ==> inj-event(beginS(id)). |

| process |

| ((!P)|(!GWN)|(!S)) |

Table 3.

Query Results.

| RESULT inj-event(endS(id)) ==> inj-event(beginS(id)) is true. |

| RESULT inj-event(endGWN(id_21256)) ==> inj-event(beginGWN(id_21256)) is true. |

| RESULT inj-event(endP(id_41657)) ==> inj-event(beginP(id_41657)) is true. |

| RESULT not attacker(IDp[]) is true. |

When we run the query in Table 2, we obtain the following result:

RESULT inj-event(EVENTA) ==> inj-event(EVENTB) is true.

RESULT inj-event(EVENTA) ==> inj-event(EVENTB) is false.

RESULT not attacker(QUERY) is true.

RESULT not attacker(QUERY) is false.

“RESULT inj-event (EVENTA) == > inj-event (EVENTB) is true.” means that EVENTA to EVENTB has been authenticated. On the other hand, “RESULT inj-event (EVENTA) == > inj-event (EVENTB) is false.” means that the authentication from EVENTA to EVENTB was not successful. “RESULT not attacker (QUERY) is true.” means that an attacker cannot get a free name QUERY, and “RESULT not attacker (QUERY) is false.” means that an attacker can trace a QUERY [32].

The results of the query in Table 2 are shown in Table 3. In that case, the authentication process is correctly performed and the attacker cannot obtain .

7.2. Informal Security Analysis

We present a theoretical analysis of our scheme. We then briefly explain the results of the analysis.

7.2.1. Privileged Insider Attack

In the registration step, the practitioner sends his/her plaintext ID and to the gateway node. Since the ID is used in conjunction with secret information K without being exposed to the outside, there is no way for an insider to know the practitioner’s personal information. Therefore, it is secure against a privileged insider attack.

7.2.2. Outsider Attack

The only contains the information , c, d, R, , , , . We cannot infer practitioner P in this case.

7.2.3. Offline ID Guessing Attack

The practitioner’s identity is not moved directly in the login and authentication phase after registration. When the sensor checks the practitioner’s ID, the information , K, and is required, all of which cannot be obtained through .

7.2.4. Online ID Guessing Attack

The practitioner’s identity can only be exposed as , K, and , as mentioned in the offline ID guessing attack. At this time, and can be seized through a message sent to the by the practitioner in the authentication phase, but the secret key K cannot be found.

7.2.5. Session Key Disclosure Attack

As shown in Section 5.2.1, the session key consists of . N is a value generated by and , and M is a value generated by and expressed as . Because the attacker is not the practitioner or , he/she cannot know the session key because including b and including K cannot be known.

7.2.6. Practitioner Impersonation Attack

verifies the practitioner in equation . If an attacker pretends to be an authorized practitioner, then he/she needs to know , . However, the attacker cannot obtain . Therefore, the attacker cannot impersonate the practitioner P.

7.2.7. Sensor Impersonation Attack

verifies a sensor with the Equation and checks that , . This means that a sensor can only prove that it is a sensor if it knows and b.

8. Performance Analysis of the Proposed Scheme

The four symbols necessary for comparison are as follows. is the time to check for a match when recognizing the user’s (or practitioner’s) biometric . is the time it takes to hash. is the time of the multiplicative operation used in ECC. The time taken for symmetric encryption or decryption is denoted by . These are listed in Table 4. We compared our scheme with the following three schemes of Chen et al. [12], Renuka et al. [13] and Li et al. [14]. The four symbols necessary for comparison are as follows, and depicted as a graph in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Notations of Time Symbol.

Figure 2.

Execution Time of Schemes.

Table 5 summarizes the total time cost for each scheme ([12,13,14]). The Y-axis shown in Figure 2 is the total time cost in microseconds (ms). This is calculated based on the times shown in Table 4. Table 6 shows the computer hardware and software used to calculate the algorithm’s runtime. Li et al.’s scheme [14] uses elliptic curve cryptography, however it has large time costs because of its slow encryption and decryption.

Table 5.

Comparison of Computation Costs.

Table 6.

Hardware and Software Condition.

| Specification | |

|---|---|

| CPU | Intel (R) Core(TM) 2T6570 2.1GHz |

| Memory | 4G |

| OS | Win7 32-bit |

| Software | Visual C++ 2008 |

The methods used in Chen et al.’s [12] and Renuka et al.’s [13] scheme have lower costs than Li et al.’s [14]. They used symmetric encryption and decryption, but had a significant difference in cost compared to ours.

9. Conclusions

Recently, several lightweight two-factor-based authentication protocols, such as Sharma and Kalra’s protocol [6] and Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s protocol [11], were proposed for IoT applications. Those protocols have some benefits in efficiency because they are designed with light and straightforward operations, such as hash function and XOR without complicated cryptographic operations. However, we found that those protocols have several security weaknesses.

To address these problems, we use three factors: the practitioner’s identity, a password, and biometric information. We propose a lightweight three-factor user authentication scheme to fix several issues in Sharma and Kalra’s protocol [6] and Adavoudi-Jolfaei et al.’s protocol [11]. We provide the security verification of the proposed scheme using ProVerif. Furthermore, we show that our proposed method outperforms other proposed symmetric-based or elliptic curve-based methods.

We are motivated to fix the problems of existing protocols and proposed a more efficient and secure authentication scheme. Our scheme is designed only with the hash function and XOR, providing fast and secure authentication. The proposed protocol can be used for various IoT applications such as medical devices.

Our proposed scheme can be implemented with simple operations, but introduces 11 new parameters. Furthermore, while our scheme is lighter than the symmetric-based or elliptic curve-based methods, it is not significantly lighter than the only used XOR and hash method. Therefore, in future work, we aim to develop a simpler authentication scheme with fewer variables. We also aim to develop a lightweight 3-factor authentication scheme with fewer xor operations and hash functions. Our efforts will contribute to creating a faster and more secure authentication scheme.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020-0-00258, Development of On-chain-based Electronic Contract Application Platform Using Zero-Knowledge Proof).

Appendix A. ProVerif Code

Table A1.

Define Values and Functions.

| (*—-channels—-*) |

| free cha:channel [private]. |

| free chb:channel. |

| free chc:channel. |

| (*—-constants—-*) |

| free Ru:bitstring [private]. |

| free IDp:bitstring [private]. |

| free IDg:bitstring [private]. |

| free IDs:bitstring. |

| free PWu:bitstring [private]. |

| (*—-secret key—-*) |

| free K:bitstring [private]. |

| (*—-functions—-*) |

| fun concat(bitstring, bitstring): bitstring. |

| fun xor(bitstring, bitstring): bitstring. |

| fun h(bitstring): bitstring. |

| equation forall a:bitstring, b:bitstring; xor(xor(a, b), b) = a. |

| (*—-events—-*) |

| event beginP(bitstring). |

| event endP(bitstring). |

| event beginGWN(bitstring). |

| event endGWN(bitstring). |

| event beginS(bitstring). |

| event endS(bitstring). |

Table A2.

Practitioner Scheme.

| (*—-P process—-*) |

| let P = |

| new R:bitstring; |

| let MPW = h(concat(h(concat(PWp, R)), Rp)) in |

| out(cha,(IDp, MPW)); |

| in(cha,(Xa:bitstring, Xc:bitstring, Xd:bitstring)); |

| event beginP(IDp); |

| new T1:bitstring; |

| new N:bitstring; |

| let ppb = xor(Xd, h(concat(MPW, Xa))) in |

| let hK = xor(Xc, h(concat(MPW, ppb))) in |

| let V1 = xor(IDp, h(concat(hK, T1))) in |

| let V2 = xor(N, h(concat(ppb, T1))) in |

| let V3 = h(concat(concat(V1, V2), concat(N, T1))) in |

| out(chb, (V1, V2, V3, T1, N)); |

| in(chb, (XXV6:bitstring, XXV8:bitstring, XV11:bitstring, XXT3:bitstring, XT4:bitstring)); |

| let pV8 = h(concat(concat(XXV6, ppb), XXT3)) in |

| let pM = xor(XXV6, h(concat(ppb, XXT3))) in |

| let SKp = h(xor(N, pM)) in |

| let pV11 = h(concat(concat(SKp, XXV6), concat(concat(XXV8, XXT3),XT4))) in |

| event endP(IDp). |

Table A3.

Gateway Node Scheme.

| (*—-GWN process—-*) |

| let GWN = |

| in(cha,(XIDp:bitstring, XMPW:bitstring)); |

| let a = h(concat(XMPW, XIDp)) in |

| let b = h(concat(XIDp, K)) in |

| let c = xor(h(K), h(concat(XMPW, b))) in |

| let d = xor(b, h(concat(XMPW, a))) in |

| out(cha, (a, c, d)); |

| in(chb, (XV1:bitstring, XV2:bitstring, XV3:bitstring, XT1:bitstring, XN:bitstring)); |

| event beginGWN(IDg); |

| new T2:bitstring; |

| new M:bitstring; |

| let pIDp = xor(XV1, h(concat(h(K), XT1))) in |

| let pV3 = h(concat(concat(XV1, XV2), concat(XN, XT1))) in |

| if pV3 = XV3 then |

| let MID = xor(IDs, h(concat(h(K), T2))) in |

| let X = h(concat(IDs, K)) in |

| let V4 = xor(M, h(concat(concat(X, XT1), T2))) in |

| let V5 = h(concat(concat(IDs, V4), concat(concat(XT1, T2), M))) in |

| out(chc, (XV1, XV2, XV3, V4, V5, XT1, T2, MID)); |

| in(chc, (XV6:bitstring, XV7:bitstring, XV10:bitstring, XT3:bitstring)); |

| new T4:bitstring; |

| new M:bitstring; |

| let pV8 = h(concat(XV6, concat(b, XT3))) in |

| let pV9 = h(concat(XV7, concat(X, XT3))) in |

| let pV10 = h(concat(pV8, concat(pV9, XT3))) in |

| if pV10 = XV10 then |

| let pN = xor(XV7, h(concat(X, XT3))) in |

| let SKg = h(xor(pN, M)) in |

| let V11 = h(concat(SKg, concat(concat(XV6, pV8), concat(XT3, T4)))) in |

| out(chb, (XV6, pV8, V11, XT3, T4)); |

| event endGWN(IDg). |

Table A4.

Sensor Scheme.

| (*—-S process—-*) |

| let S = |

| in(chc, (XXV1:bitstring, XXV2:bitstring, XXV3:bitstring, XV4:bitstring, XV5:bitstring, |

| XXT1:bitstring, XT2:bitstring, XMID:bitstring)); |

| event beginS(IDs); |

| new T3:bitstring; |

| let XX = h(concat(IDs, K)) in |

| let pM = xor(XV4, h(concat(concat(XX, XXT1), XT2))) in |

| let pV5 = h(concat(concat(IDs, XV4), concat(concat(XXT1, XT2), pM))) in |

| if pV5 = XV5 then |

| let pb = h(concat(IDp, K)) in |

| let ppN = xor(XXV2, h(concat(pb, XXT1))) in |

| let V6 = xor(pM, h(concat(pb, T3))) in |

| let V7 = xor(ppN, h(concat(XX, T3))) in |

| let V8 = h(concat(concat(V6, pb), T3)) in |

| let V9 = h(concat(concat(V7, XX), T3)) in |

| let V10 = h(concat(concat(V8, V9), T3)) in |

| out(chc, (V6, V7, V10, T3)); |

| event endS(IDs). |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R. and D.K.; methodology, J.R. and H.L.; software, H.L.; validation, J.R.; formal analysis, J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.; writing—review and editing, J.R. and H.K.; supervision, D.W.; project administration, J.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gregg M. Trends in Remote Patient Monitoring 2019. Spyglass Consulting Group. [(accessed on 12 December 2020)]; Available online: http://www.spyglass-consulting.com/wp_RPM_2019.html.

- 2.Hu Y.H., Tompkins W.J., Urrusti J.L., Afonso V.X. Applications of artificial neural networks for ECG signal detection and classification. J. Electrocardiol. 1993;26:66–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeh Y.C., Wang W.J. QRS complexes detection for ECG signal: The Difference Operation Method. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2008;91:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Ess D.W. ECG Signal Detection Device. 7,092,750. US Patent. 2006 Aug 15;

- 5.Chung W.Y., Lee Y.D., Jung S.J. A wireless sensor network compatible wearable u-healthcare monitoring system using integrated ECG, accelerometer and SpO2; Proceedings of the 2008 30th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; Vancouver, BC, Canada. 20–25 August 2008; pp. 1529–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma G., Kalra S. A Lightweight User Authentication Scheme for Cloud-IoT Based Healthcare Services. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 2019;43:619–636. doi: 10.1007/s40998-018-0146-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryu J., Lee H., Kim H., Won D. Secure and efficient three-factor protocol for wireless sensor networks. Sensors. 2018;18:4481. doi: 10.3390/s18124481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathore H., Al-Ali A., Mohamed A., Du X., Guizani M. DTW based authentication for wireless medical device security; Proceedings of the 2018 14th International Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC); Limassol, Cyprus. 25–29 June 2018; pp. 476–481. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali R., Pal A.K., Kumari S., Sangaiah A.K., Li X., Wu F. An enhanced three factor based authentication protocol using wireless medical sensor networks for healthcare monitoring. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2018:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s12652-018-1015-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi Y., Lee D., Kim J., Jung J., Nam J., Won D. Security enhanced user authentication protocol for wireless sensor networks using elliptic curves cryptography. Sensors. 2014;14:10081–10106. doi: 10.3390/s140610081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adavoudi-Jolfaei A., Maede A.T., Aghili S.F. Lightweight and anonymous three-factor authentication and access control scheme for real-time applications in wireless sensor networks. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2019;12:43–59. doi: 10.1007/s12083-017-0627-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y., Ge Y., Wang Y., Zeng Z. An improved three-factor user authentication and key agreement scheme for wireless medical sensor networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:85440–85451. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2923777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renuka K., Kumar S., Kumari S., Chen C.M. Cryptanalysis and improvement of a privacy-preserving three-factor authentication protocol for wireless sensor networks. Sensors. 2019;19:4625. doi: 10.3390/s19214625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X., Niu J., Bhuiyan M.Z.A., Wu F., Karuppiah M., Kumari S. A robust ECC-based provable secure authentication protocol with privacy preserving for industrial internet of things. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017;14:3599–3609. doi: 10.1109/TII.2017.2773666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu F., Jiang M., Wagner M., Dong D.C. Privacy-preserving telecardiology sensor networks: Toward a low-cost portable wireless hardware/software codesign. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2007;11:619–627. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2007.894818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malasri K., Wang L. Design and implementation of a securewireless mote-based medical sensor network. Sensors. 2009;9:6273–6297. doi: 10.3390/s90806273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar P., Lee S.G., Lee H.J. E-SAP: Efficient-strong authentication protocol for healthcare applications using wireless medical sensor networks. Sensors. 2012;12:1625–1647. doi: 10.3390/s120201625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan M.K., Kumari S. An improved user authentication protocol for healthcare services via wireless medical sensor networks. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2014;10:347169. doi: 10.1155/2014/347169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X., Niu J., Kumari S., Liao J., Liang W., Khan M.K. A new authentication protocol for healthcare applications using wireless medical sensor networks with user anonymity. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2016;9:2643–2655. doi: 10.1002/sec.1214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu F., Xu L., Kumari S., Li X. An improved and anonymous two-factor authentication protocol for health-care applications with wireless medical sensor networks. Multimed. Syst. 2017;23:195–205. doi: 10.1007/s00530-015-0476-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hossain M.S., Muhammad G. Cloud-assisted speech and face recognition framework for health monitoring. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2015;20:391–399. doi: 10.1007/s11036-015-0586-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wazid M., Das A.K., Shetty S., Rodrigues J.J.P.C., Park Y. LDAKM-EIoT: Lightweight device authentication and key management mechanism for edge-based IoT deployment. Sensors. 2019;19:5539. doi: 10.3390/s19245539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanveer M., Zahid A.H., Ahmad M., Baz A., Alhakami H. LAKE-IoD: Lightweight Authenticated Key Exchange Protocol for the Internet of Drone Environment. IEEE Access. 2020;8:155645–155659. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3019367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gope P., Tzonelih H. A realistic lightweight anonymous authentication protocol for securing real-time application data access in wireless sensor networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016;63:7124–7132. doi: 10.1109/TIE.2016.2585081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz J., Menezes A.J., Van Oorschot P.C., Vanstone S.A. Handbook of Applied Cryptography. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodis Y., Katz J., Reyzin L., Smith A. Annual International Cryptology Conference. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2006. Robust fuzzy extractors and authenticated key agreement from close secrets; pp. 232–250. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dodis Y., Reyzin L., Smith A. International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2004. Fuzzy extractors: How to generate strong keys from biometrics and other noisy data; pp. 523–540. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolev D., Yao A. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 1983;29:198–208. doi: 10.1109/TIT.1983.1056650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moon J., Lee D., Lee Y., Won D. Improving biometric-based authentication schemes with smart card revocation/reissue for wireless sensor networks. Sensors. 2017;17:940. doi: 10.3390/s17050940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee H., Lee D., Moon J., Jung J., Kang D., Kim H., Won D. An improved anonymous authentication scheme for roaming in ubiquitous networks. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu F., Li X., Sangaiah A.K., Xu L., Kumari S., Wu L., Shen J. A lightweight and robust two-factor authentication scheme for personalized healthcare systems using wireless medical sensor networks. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018;82:727–737. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2017.08.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanchet B., Smyth B., Cheval V., Sylvestre M. ProVerif 2.00: Automatic Cryptographic Protocol Verifier, User Manual and Tutorial. [(accessed on 12 December 2020)];2018 :5–16. Available online: https://prosecco.gforge.inria.fr/personal/bblanche/proverif/manual.pdf.

- 33.Das A.K. A secure and robust temporal credential-based three-factor user authentication scheme for wireless sensor networks. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2016;9:223–244. doi: 10.1007/s12083-014-0324-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L., Wu F. Cryptanalysis and improvement of a user authentication scheme preserving uniqueness and anonymity for connected health care. J. Med. Syst. 2015;39:10. doi: 10.1007/s10916-014-0179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]