Abstract

Background

Studies have shown that short‐term exposure to air pollution is associated with cardiac arrhythmia hospitalization and mortality. However, the relationship between long‐term particulate matter air pollution and arrhythmias is still unclear. We evaluate the prospective association between particulate matter (PM) air pollution and the risk of incident arrhythmia and its subtypes.

Methods and Results

Participants were drawn from a prospective cohort study of 178 780 men and women who attended regular health screening exams in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea, from 2002 to 2016. Exposure to PM with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤10 and ≤2.5 μm (PM10 and PM2.5, respectively) was estimated using a land‐use regression model. The associations between long‐term PM air pollution and arrhythmia were examined using pooled logistic regression models with time‐varying exposure and covariables. In the fully adjusted model, the odds ratios (ORs) for any arrhythmia associated with a 10 μg/m3 increase in 12‐, 36‐, and 60‐month PM10 exposure were 1.15 (1.09, 1.21), 1.12 (1.06, 1.18), and 1.14 (1.08, 1.20), respectively. The ORs with a 10 μg/m3 increase in 12‐ and 36‐month PM2.5 exposure were 1.27 (1.15, 1.40) and 1.10 (0.99, 1.23). PM10 was associated with increased risk of incident bradycardia and premature atrial contraction. PM2.5 was associated with increased risk of incident bradycardia and right bundle‐branch block.

Conclusions

In this large cohort study, long‐term exposure to outdoor PM air pollution was associated with increased risk of arrhythmia. Our findings indicate that PM air pollution may be a contributor to cardiac arrhythmia in the general population.

Keywords: air pollution, arrhythmias, particulate matter

Subject Categories: Arrhythmias, Epidemiology, Cardiovascular Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- NCDSS

the Korean National Climate Data Service System

- PM10

particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤10

- PM2.5

particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤2.5

- WPW

Wolff‐Parkinson‐White

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Long‐term particulate matter air pollution was associated with increased incidence of bradycardia, right bundle‐branch block, and premature atrial contraction arrythmias in the general population.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Measures to control the level of particulate matterair pollution are required and may reduce the burden of arrythmias, as exposure to particulate matter air pollution is chronic.

Prevention and treatment of cardiac arrythmias might benefit from identification of relevant pathophysiological pathways associated with particulate matter air pollutions.

Cardiac arrhythmias, a group of conditions defined by an abnormal electrical activity of the heart, are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality. 1 , 2 The prevalence of certain types of arrhythmia, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), is projected to increase exponentially in the next decade, 3 partly as a reflection of the rising prevalence of increased CVD risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. 4 Nevertheless, environmental biomarkers (such as air pollution, noise, and natural environment) other than traditional CVD risk factors are implicated in the development of arrhythmia and could be potential targets for its prevention and management. 5

While a meta‐analysis showed that short‐term exposure to air pollution was associated with cardiac arrhythmia hospitalization and mortality, 6 the relationship between long‐term particulate matter (PM) air pollution and arrhythmia is still unclear. Some studies have found a positive association between long‐term PM air pollution exposure and ventricular arrhythmia in patients in high risk. 7 , 8 More recently, 2 general population‐based cohort studies from Canada and South Korea found that air pollution was associated with increased onset of atrial fibrillation. 9 , 10 However, no previous study has evaluated the association between long‐term PM air pollution and other types of cardiac arrhythmias in a general population setting with relatively high air pollution levels.

We therefore evaluated the association between PM air pollution and risk of incident arrhythmia, including AF, bradycardia, premature cardiac contractions, right bundle‐branch block (RBBB), tachycardia, and other types of arrhythmias, in a large cohort of middle‐aged Korean men and women who attended repeated health screening exams between 2002 and 2016. We hypothesized that participants exposed to a higher concentration of PM air pollution would be at higher risk of arrhythmias compared with those exposed to a lower concentration of PM air pollution.

Methods

Study Population

We obtained data from the KSHS (Kangbuk Samsung Health Study), an ongoing cohort study of South Korean men and women 18 years of age or older who underwent comprehensive annual or biennial health examinations at the clinics of the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Total Healthcare Center in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea. 11 In our study, over 80% of the participants were employees from various companies or local government organizations and their spouses. The remaining participants voluntarily purchased screening exams at the health exam center.

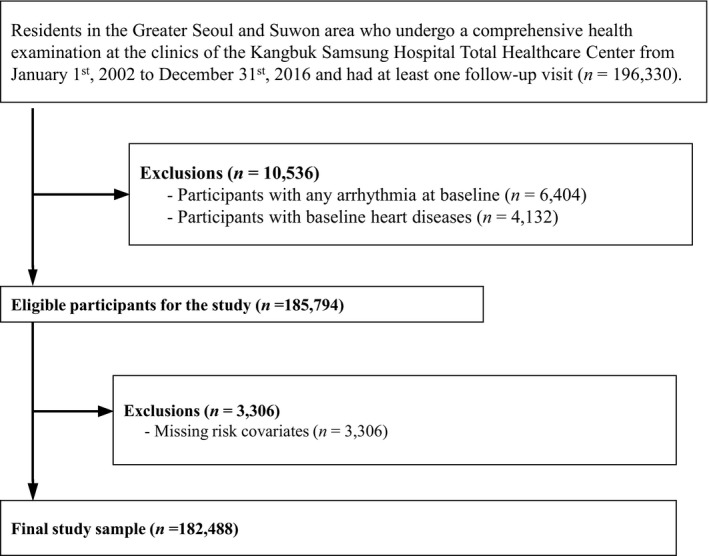

We included participants who lived in the Greater Seoul metropolitan areas (605.3 km2 in Seoul, 1063 km2 in Incheon, and 10 184 km2 in Gyeonggi‐do Province [Suwon center]) and who attended at least 2 health screening exams from January 1, 2002 through December 31, 2016 (n=196 330; Figure 1). We excluded participants with any arrhythmia (n=6404) or history of heart diseases (n=4132) at baseline. We further excluded participants with missing data on potential risk covariates (n=3306). The final sample included 182 488 participants (102 698 men and 79 790 women). The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, and the requirement of informed consent was waived because we only used deidentified data routinely collected during health screening visits.

Figure 1. Flowchart of study participants.

Assessment of PM Air Pollution

We used a land use regression model to estimate monthly PM10 and PM2.5 concentration at a 1‐km resolution for each participant based on their address postal codes in Seoul or Suwon city. 12 Briefly, PM concentrations were collected from the Seoul Metropolitan Government Atmospheric Environment, the Gyeonggi‐do Institute of Health & Environment, as well as the Korean National Climate Data Service System. For PM10, data were collected since 2002 for Seoul and Suwon. We used mixed generalized additive regression models to estimate individual monthly mean PM10 concentrations from January 1, 2002 through December 31, 2016. Covariates included smoothed county population density, seasonal terms (year and month), meteorological variables (temperature, humidity, wind speed, pressure, etc), digital altitude elevation, distance to the nearest power plants (industrial pollution), percentage of land coverage within 300, 500, 1000, 3000, and 5000‐m buffers, and distance to the nearest road (traffic pollution). For PM2.5, data were collected since 2008 for Seoul and since 2014 for Suwon, and were modeled in a way analogous to PM10, as described above. For Suwon, we imputed PM2.5 levels between 2008 and 2014 using the product of the PM2.5/PM10 ratio calculated using 2008 to 2014 data from Seoul and concurrent PM10 levels in Suwon.

In a cross‐validation study, we built the models in a training data set including 70% of the measurements, used the models to predict PM10 and PM2.5 values in a test data set including the rest 30% of the measurements, and compared the predicted values with the observed measurements. The models had a high predictive accuracy (cross‐validation R 2 values of 0.80 and 0.77 for PM10 and PM2.5, respectively).

For each participant, we calculated the 12‐, 36‐, and 60‐ month mean PM10 concentration and 12‐ and 36‐month mean PM2.5 concentration before each visit (60‐month PM2.5 analyses were unavailable because of the shorter time‐frame of measurements). The follow‐up for 12‐month PM10 analysis was from January 1, 2003 through December 31, 2016; the follow‐up for 12‐month PM2.5 was from January 1, 2009 through December 31, 2016.

Assessment of Cardiac Arrhythmias

In each health screening exam, standard 12‐lead ECGs were digitally acquired using an ECG recorder (CARDIMAX FX‐7542; Fukuda Denishi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 1 mV/cm calibration and 25 mm/s speed. All ECGs were initially inspected visually for technical errors and inadequate quality. Arrhythmias were automatically documented from the ECGs analysis program (PI‐19E, Fukuda Denshi, Tokyo, Japan) and interpreted by a cardiologist.

We defined 6 types of arrhythmia as end points for our analyses: AF or flutter, bradycardia (resting heart rate <50 beats/min), premature atrial contractions, premature ventricular contractions, right bundle branch blocks (RBBB, QRS ≥120 ms, RSR' pattern in V1–3, and slurred S wave in the lateral leads [I, aVL and V5–V6]), tachycardia (resting heart rate ≥100 beats/min), and other arrhythmias (Wolff‐Parkinson‐White [WPW] syndrome, sinus arrhythmia, etc). 13

Health Screening Exams

At each screening exam, standardized questionnaires were used to collect information on sociodemographic factors, lifestyle characteristics, disease history, and medication use. Alcohol consumption was categorized as none, moderate (men: >0 to ≤30 g/day, women: >0 to ≤20 g/day), or excessive (men >30 g/day, women >20 g/day). Physical activity was classified into 3 categories: none, <3 times per week, ≥3 times per week. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dL, a self‐reported history of diabetes mellitus, or self‐reported use of antidiabetic medications. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg, a self‐reported history of hypertension, or current use of antihypertensive medications.

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the design of the study, the writing or editing of this document, or the interpretation or dissemination of the results.

Statistical Analysis

We used pooled logistic regression models with time‐varying exposures and covariates to evaluate the association of long‐term PM10 and PM2.5 exposure and the development of arrhythmia. For time‐dependent analyses, the pooled logistic regression model closely approximates a Cox model when the risk of outcome between intervals is low. 14 The primary outcome of the study was the development of any arrhythmia. The secondary outcomes were the development of each individual type of arrhythmia. Participants who developed arrhythmia contributed person‐time from the baseline visit until the visit in which they developed the arrhythmia. The rest of participants contributed person‐time until their last available visit.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs were calculated per 10 μg/m3 increment in PM concentration. We used 2 models with increasing degrees of adjustment: model 1 adjusted for age, sex, study center, year of visit, and education level; model 2 additionally adjusted for systolic blood pressure, smoking status, height, weight, alcohol consumption, physical activity, diabetes mellitus, history of diabetes mellitus, and history of hypertension.

As for sensitivity analyses for PM10 air pollution, we conducted analyses for 12‐ and 36‐month PM10 exposure among the same participants as the 60‐month PM10 exposure. For PM2.5 air pollution, we conducted analyses for 12‐month PM2.5 exposure among the same participants as the 36‐month PM2.5 exposure.

To evaluate the nonlinear dose‐response relationships between PM air pollution and risk of arrhythmia, we modeled PM10 and PM2.5 air pollution using restricted cubic splines with knots at the 5th, 25th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of the distribution of PM concentrations. We also assessed potential effect modification by age group, sex, alcohol intake, physical exercise, and smoking status, using likelihood ratio tests comparing models with an interaction (product) term between air pollution exposure and the effect modifier versus models without the interaction term.

This study was done without adjustment for multiplicity (multiple exposures, multiple time points, and multiple end points) and, thus, the Type I error was not controlled to 0.05. All analyses were performed with Stata (version 15.0; Stata Corporation) and R (Version 3.4.1; R Development Core Team).

Results

The mean (SD) age at inclusion was 36.5 (7.0) years, and 56.3% of study participants were male. The monthly mean (SD) concentrations of PM10 during the 12‐, 36‐, and 60‐month periods before the baseline visit were 56.6 (7.5), 55.6 (6.2), and 56.1 (5.3) μg/m3, respectively; the mean (SD) concentration of PM2.5 during the 12‐ and 36‐month periods before the baseline visit were 26.6 (2.3) and 26.3 (2.3) μg/m3, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Medical History of KSHS Cohort Participants

| Characteristic | Overall | No Arrhythmia During Follow‐Up | Any Arrhythmia During Follow‐Up | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 182 488 | 167 763 | 14 725 | |

| Age, y | 36.5 (7.0) | 36.6 (7.0) | 36.3 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Male, % | 102 698 (56.3) | 92 371 (55.1) | 10 327 (70.1) | <0.001 |

| 12‐mo PM2.5 mean, μg/m3 | 26.6 (2.3) | 26.2 (2.3) | 26.4 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| 36‐mo PM2.5 mean, μg/m3 | 26.3 (2.3) | 26.3 (2.3) | 26.5 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| 12‐mo PM10 mean, μg/m3 | 56.6 (7.5) | 56.4 (7.5) | 58.8 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| 36‐mo PM10 mean, μg/m3 | 55.6 (6.2) | 55.5 (6.2) | 57.6 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| 60‐mo PM10 mean, μg/m3 | 56.1 (5.3) | 56.0 (5.3) | 57.8 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| Height | 167.7 (8.3) | 167.5 (8.3) | 169.7 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Weight | 65.6 (12.7) | 65.5 (12.7) | 66.5 (11.9) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | |||

| Never | 96 912 (53.1) | 90 894 (54.2) | 6018 (40.9) | |

| Former | 41 784 (22.9) | 37 396 (22.3) | 4388 (29.8) | |

| Current | 43 792 (24.0) | 39 473 (23.5) | 4319 (29.3) | |

| Alcohol intake | <0.001 | |||

| None | 50 091 (27.4) | 46 351 (27.6) | 3740 (25.4) | |

| Moderate | 115 219 (63.1) | 105 594 (62.9) | 9625 (65.4) | |

| High | 17 178 (9.4) | 15 818 (9.4) | 1360 (9.2) | |

| Daily physical activity | <0.001 | |||

| None | 110 357 (60.5) | 102 242 (60.9) | 8115 (55.1) | |

| <3 times | 54 608 (29.9) | 49 844 (29.7) | 4764 (32.4) | |

| 3 times or more | 17 523 (9.6) | 15 677 (9.3) | 1846 (12.5) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 2254 (1.2) | 2090 (1.2) | 164 (1.1) | 0.176 |

| Hypertension, % | 19 006 (10.4) | 17 528 (10.4) | 1478 (10.0) | 0.121 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 110.9 (13.5) | 110.8 (13.5) | 112.1 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | <0.001 |

Numbers in the table are mean (SD) or count (%). BP indicates blood pressure; KSHS, Kangbuk Samsung Health Study; PM10, particulate matter of <10 μm in aerodynamic diameter; and PM2.5, particulate matter of <2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter.

The median (range) follow‐up time was 4.8 (0.5–13.9) years for PM10 and 3.8 (0.5–7.9) years for PM2.5 analyses. For PM10 analyses, there were 16 149 incident cases of any arrhythmia during follow‐up (6373 bradycardias, 180 AF, 1705 premature ventricular contraction, 670 premature atrial contraction, 669 tachycardia, 4760 RBBB, and 1792 other arrythmias). For PM2.5 analyses, there were 12 769 incident cases of any arrhythmia during follow‐up (5499 bradycardias, 116 AF, 1186 premature ventricular contraction, 488 premature atrial contraction, 450 tachycardia, 3732 RBBB, and 1298 other arrythmias) (Table S1).

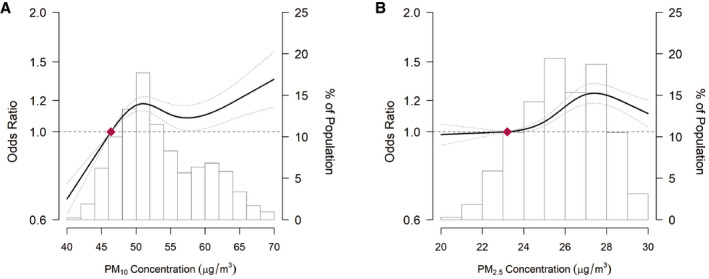

In the fully adjusted models, the ORs (95% CI) for any arrhythmia associated with a 10 μg/m3 increase in 12‐, 36‐, and 60‐month PM10 exposure were 1.14 (1.09–1.20), 1.11 (1.05–1.17), and 1.13 (1.07–1.19), respectively (Table 2). The ORs for a 10 μg/m3 increase in 12‐ and 36‐month PM2.5 exposure were 1.27 (1.15–1.40) and 1.11 (1.00–1.23). Spline regression analyses confirmed that increasing 12‐month mean PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations were associated with an increased risk of any arrhythmias, although the associations were non‐linear (P for non‐linear spline terms <0.001; Figure 2).

Table 2.

ORs (95% CI) for Each 10 μg/m3 Increase in Particulate Matter Exposure Associated with Risk of Any Arrhythmias in KSHS Cohort From 2002 to 2016

| Exposures | Models | 12‐mo | 36‐mo | 60‐mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM10 | Model 1 | 1.13 (1.08, 1.19) | 1.10 (1.05, 1.16) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) |

| Model 2 | 1.14 (1.09, 1.20) | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | |

| PM2.5 | Model 1 | 1.29 (1.17, 1.42) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.25) | |

| Model 2 | 1.27 (1.15, 1.40) | 1.11 (1.00, 1.23) |

Model 1. Adjusted for age (continuous), sex (men or women), study center (Seoul or Suwon), year of visit (continuous), and education level (no education, elementary school, middle school, high school, technical college, university, or more). Model 2. Additionally, systolic blood pressure (continuous), smoking status (never, current, former), height (continuous), weight (continuous), alcohol consumption (none, moderate, or excessive), physical activity (none, <3 times per week, or ≥3 times per week), and history of diabetes mellitus (yes or no) and history of hypertension (yes or no). KSHS indicates Kangbuk Samsung Health Study; PM10, particulate matter of <10 μm in aerodynamic diameter; and PM2.5, particulate matter of <2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter.

Figure 2. ORs for risks of arrhythmias by the level of exposure to 12‐month PM10 and PM2.5 concentration.

(A) OR for PM10 exposure; (B) OR for PM2.5 exposure. PM2.5 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤2.5), PM10 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤10). The dose‐response curve was calculated using restricted cubic splines with knots at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles of the distribution of 60‐month PM10 concentrations. The reference exposure level was set at the 10th percentile of the distribution of 12‐month PM10 concentrations (47.7 μg/m3) and 12‐month PM2.5 concentrations (23.2 μg/m3). ORs were adjusted for age (continuous), sex (men or women), study center (Seoul or Suwon), year of visit (continuous), education level (no education, elementary school, middle school, high school, technical college, university, or more), systolic blood pressure (continuous), smoking status (never, current, former), height (continuous), weight (continuous), alcohol consumption (none, moderate, or excessive), physical activity (none, <3 times per week, or ≥3 times per week), and history of diabetes mellitus (yes or no) and history of hypertension (yes or no).

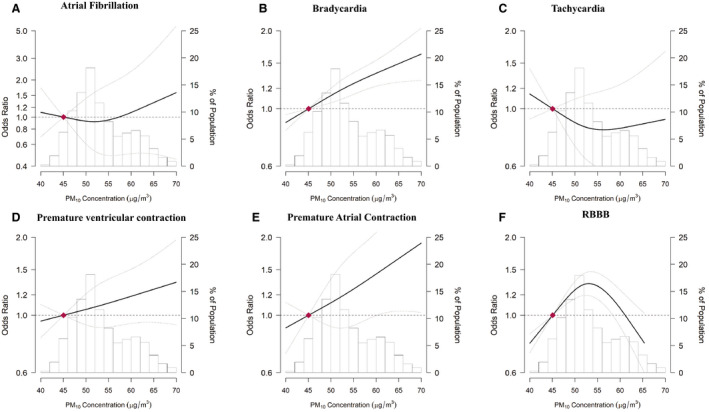

Among individual arrhythmia types, an increase in PM10 or in PM2.5 air pollution exposure was associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk of bradycardia, irrespective of the duration of the exposure period (Table 3). In addition, PM10 exposure during the 12‐ and 36‐months before baseline was associated with a statistically significant increased risk of premature atrial contraction, and PM2.5 exposure 12‐ and 36‐months before baseline was associated with RBBB disorders. In spline regression analyses, the risk of bradycardia and premature contraction increased with the increasing 12‐month mean PM10 throughout most of its distribution (Figure 3).

Table 3.

ORs (95% CI) for Secondary Outcomes Associated with Particulate Matter Exposures

| Arrhythmias | Exposure | Models | Exposure Duration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12‐mo | 36‐mo | 60‐mo | |||

| Atrial Fibrillation | PM10 | Model 1 | 1.04 (0.63, 1.74) | 0.98 (0.54, 1.79) | 1.33 (0.66, 2.67) |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (0.62, 1.74) | 0.99 (0.54, 1.80) | 1.34 (0.67, 2.70) | ||

| PM2.5 | Model 1 | 1.50 (0.64, 3.52) | 0.93 (0.47, 1.84) | ||

| Model 2 | 1.51 (0.66, 3.49) | 0.94 (0.48, 1.84) | |||

| Bradycardia | PM10 | Model 1 | 1.21 (1.12, 1.31) | 1.22 (1.13, 1.32) | 1.19 (1.10, 1.29) |

| Model 2 | 1.23 (1.14, 1.33) | 1.23 (1.14, 1.33) | 1.21 (1.12, 1.31) | ||

| PM2.5 | Model 1 | 1.22 (1.06, 1.40) | 1.22 (1.05, 1.41) | ||

| Model 2 | 1.20 (1.04, 1.38) | 1.19 (1.03, 1.38) | |||

| Premature Ventricular Contraction | PM10 | Model 1 | 1.11 (0.96, 1.29) | 1.08 (0.92, 1.27) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.25) |

| Model 2 | 1.11 (0.96, 1.29) | 1.08 (0.92, 1.27) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.25) | ||

| PM2.5 | Model 1 | 0.99 (0.72, 1.35) | 0.83 (0.59, 1.16) | ||

| Model 2 | 0.99 (0.72, 1.36) | 0.84 (0.60, 1.16) | |||

| Premature Atrial Contraction | PM10 | Model 1 | 1.31 (1.03, 1.65) | 1.33 (1.05, 1.69) | 1.38 (1.06, 1.79) |

| Model 2 | 1.31 (1.03, 1.66) | 1.34 (1.05, 1.70) | 1.39 (1.07, 1.80) | ||

| PM2.5 | Model 1 | 1.09 (0.63, 1.88) | 0.96 (0.53, 1.74) | ||

| Model 2 | 1.09 (0.63, 1.87) | 0.96 (0.53, 1.74) | |||

| RBBB | PM10 | Model 1 | 1.06 (0.97, 1.16) | 0.97 (0.88, 1.06) | 1.02 (0.92, 1.12) |

| Model 2 | 1.08 (0.98, 1.18) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.08) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.14) | ||

| PM2.5 | Model 1 | 1.74 (1.46, 2.08) | 1.19 (0.99, 1.44) | ||

| Model 2 | 1.70 (1.42, 2.04) | 1.17 (0.97, 1.41) | |||

| Tachycardia | PM10 | Model 1 | 0.95 (0.74, 1.22) | 1.09 (0.84, 1.41) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.43) |

| Model 2 | 0.92 (0.71, 1.18) | 1.05 (0.81, 1.36) | 1.03 (0.76, 1.39) | ||

| PM2.5 | Model 1 | 0.90 (0.60, 1.34) | 0.97 (0.63, 1.50) | ||

| Model 2 | 0.90 (0.60, 1.34) | 1.00 (0.65, 1.55) | |||

| Other | PM10 | Model 1 | 1.15 (0.99, 1.33) | 1.13 (0.97, 1.32) | 1.22 (1.04, 1.42) |

| Model 2 | 1.15 (0.99, 1.33) | 1.14 (0.97, 1.32) | 1.22 (1.05, 1.43) | ||

| PM2.5 | Model 1 | 0.88 (0.69, 1.11) | 0.87 (0.64, 1.18) | ||

| Model 2 | 0.87 (0.69, 1.10) | 0.86 (0.64, 1.16) | |||

Model 1. Adjusted for age (continuous), sex (men or women), study center (Seoul or Suwon), year of visit (continuous), and education level (no education, elementary school, middle school, high school, technical college, university, or more). Model 2. Additionally, systolic blood pressure (continuous), smoking status (never, current, former), height (continuous), weight (continuous), alcohol consumption (none, moderate, or excessive), physical activity (none, <3 times per week, or ≥3 times per week), and history of diabetes mellitus (yes or no) and history of hypertension (yes or no). PM10 indicates particulate matter of <10 μm in aerodynamic diameter; PM2.5, particulate matter of <2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter; and RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Figure 3. ORs for risks of specific arrhythmia diseases by the level of exposure to 12‐month PM10 concentration.

A, OR for atrial fibrillation; (B) OR for bradycardia; (C) OR for tachycardia; (D) OR for premature ventricular contraction; (E) OR for premature atrial contraction; (F) OR for RBBB. PM2.5 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤2.5), PM10 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤10), RBBB (right bundle branch block). The dose‐response curve was calculated using restricted cubic splines with knots at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles of the distribution of 12‐month PM10 concentrations. The reference exposure level was set at the 10th percentile of the distribution of 12‐month PM10 concentrations (47.7 μg/m3). ORs were adjusted for age (continuous), sex (men or women), study center (Seoul or Suwon), year of visit (continuous), education level (no education, elementary school, middle school, high school, technical college, university, or more), systolic blood pressure (continuous), smoking status (never, current, former), height (continuous), weight (continuous), alcohol consumption (none, moderate, or excessive), physical activity (none, <3 times per week, or ≥3 times per week), and history of diabetes mellitus (yes or no) and history of hypertension (yes or no). OR indicates odds ratio; and RBBB, right bundle branch block.

In sensitivity analyses, the associations between PM air pollution and general arrhythmias were consistent when we restricted the analyses for 12‐ and 36‐month PM10 exposure using the same participants as the 60‐month PM10 exposure, and for 12‐month PM2.5 exposure using the same participants as the 36‐month PM2.5 exposure (Tables S2 and S3).

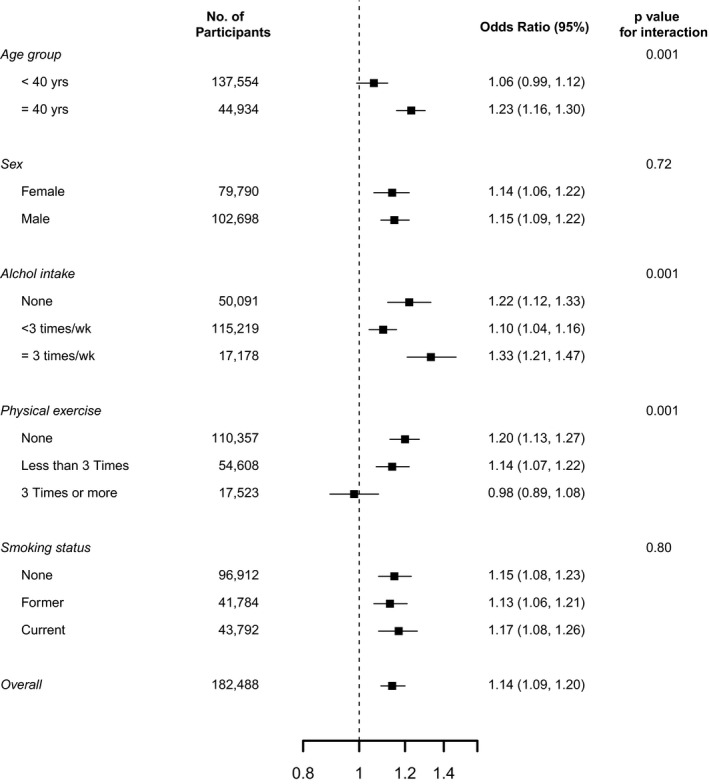

In subgroup analyses, the association between exposure to PM10 and risk of any arrhythmia was stronger in participants ≥40 years of age compared with those <40 years (P for interaction=0.001), in heavy alcohol drinkers compared with moderate drinkers or non‐drinkers (P for interaction=0.001), and in physically inactive compared with active participants (P for interaction=0.001, Figure 4).

Figure 4. ORs (95% CI) for risks of arrhythmias associated with a 10 μg/m3 increase in 12‐month PM10 concentrations, by baseline participant characteristics.

ORs were adjusted for age (continuous), sex (men or women), study center (Seoul or Suwon), year of visit (continuous), education level (no education, elementary school, middle school, high school, technical college, university, or more), systolic blood pressure (continuous), smoking status (never, current, former), height (continuous), weight (continuous), alcohol consumption (none, moderate, or excessive), physical activity (none, <3 times per week, or ≥3 times per week), and history of diabetes mellitus (yes or no) and history of hypertension (yes or no). OR indicates odds ratio.

Discussion

In this large prospective study of middle‐aged Korean men and women, long‐term exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 air pollution was associated with increased risk of arrhythmia, more specifically bradycardia, premature atrial contractions, and RBBB. The associations were stronger in older participants, heavy alcohol drinkers, and in those who were physically inactive.

The mechanisms underlying the association between PM air pollution and arrhythmias are unclear. Inhalation of PM and absorption of its constituents into the bloodstream could result in high levels of reactive oxygen species, systemic inflammation, and prothrombotic factors. Additionally, PM could alter endothelial structure and function and affect the autonomic tone, leading to acute or chronic vasoconstriction and cardiac arrhythmias. 15 In rats, ECG morphology changed and atrioventricular block arrhythmias increased in response to traffic derived PM2.5. 16 This finding is consistent with our observation of increased risk of RBBB associated with ambient PM2.5. In experimental studies on healthy adults, controlled short‐term exposure of concentrated ambient particles was also associated with significant changes in indices of inflammation, hemostasis, autonomic heart rate control, and cardiac repolarization. 17 Moreover, in cross‐sectional studies of subjects at high risk of CVD, short‐term and long‐term exposure to PM air pollution were associated with increased risk of arrhythmia. 7 , 18

Bradycardia

Bradycardia is a common, usually asymptomatic condition in the general population, but severe bradycardia could predict cardiac arrest and other CVD outcomes. 19 Few studies have investigated the effect of PM air pollution on the risk of bradycardia. Higher air pollution concentrations may increase the occurrence of bradycardia in infants in high‐risk. 20 In a study of 10 healthy participants over 60 years of age, short‐term exposure to concentrated ambient air pollution particles immediately decreased their heart rate variability and was associated with a 5‐fold increase in bradycardia. 21 The physiological importance of the observed association of long‐term PM air pollution exposure with bradycardia is unclear, and more research is warranted.

Premature Atrial Contraction

Premature atrial contraction is a common, benign cardiac dysrhythmia with no pathological significance; however, growing evidence has suggested that premature atrial contraction may be associated with the development of atrial fibrillation and stroke. 22 , 23 In a study of 105 community‐dwelling healthy nonsmokers, exposure to PM2.5 was not associated with increased premature atrial contraction frequency. 24 For long‐term PM exposure, the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study showed that increased long‐term, but not short‐term PM2.5 exposure, was associated with higher prevalence of premature atrial contraction. 25 Possible explanations for the discrepancies between the REGARDS study and our study include: the study design (cross‐sectional versus longitudinal), population (Black and White versus Asian), and exposure levels (1‐year PM2.5 mean concentration of 13.5 μg/m3 versus 26.6 μg/m3 in our study). The association between PM10 and premature cardiac contraction, however, has not been previously examined, and the positive association between long‐term PM10 and the risk of premature atrial contraction in our study needs to be confirmed in future studies.

Right Bundle‐Branch Block

The relationship between air pollution and the development of RBBB has not been extensively studied. In the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) study, long‐term exposure to PM2.5 was associated with an increased prevalence of ventricular conduction abnormalities in adults without clinical cardiovascular disease. 26 In our study, PM2.5, but not PM10, was associated with a higher risk of incident RBBB. It is known that PM2.5 penetrates deeper into the lungs and reaches the alveolar region because of its smaller size compared with PM10. Also, PM2.5 may be more toxic, as it includes nitrates, sulfates, metals, and particles with various chemicals, and the higher surface area per unit mass for PM2.5 could increase the adsorption and condensation toxicants. 27 In this study, we did not test the associations between long‐term PM exposure and other types of conduction disorders, including AV block and left bundle branch block, because of the limited number of cases during follow‐up visits.

Atrial Fibrillation and Tachycardia

Short‐ and long‐term exposure to PM or gaseous air pollution, including PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon dioxide (CO), ozone, and black carbon (BC) have been positively associated with AF and tachycardia. 18 , 28 In our study, long‐term PM air pollution exposure was associated with an increased risk of AF and tachycardia, but the associations were not statistically significant. Possible reasons for the inconsistent associations across studies include: differences in sample size, study settings, air pollution levels, and pre‐existing conditions of the study populations.

In our study, 12‐month PM2.5 had a stronger association than 36‐ or 60‐month PM2.5 with atrial fibrillation and RBBB. This could attributable to a more robust association with a longer follow‐up time for 12‐month PM2.5 analysis.

Interaction Effects

The positive association between air pollution and the risk of arrhythmias was more pronounced in participants ≥40 years of age, and in participants with higher levels of alcohol intake and lower levels of physical exercise. The mechanisms underlying these differences are unclear. Vulnerable populations, including the elderly, or participants with underlying conditions, tend to be more susceptible to the effects of PM air pollution exposure, but these differences need to be confirmed in future studies. 10 , 28 , 29

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study included the large sample size, the long follow‐up period, and the availability of detailed information on various potential lifestyle and socioeconomic confounders. Our findings, however, should be interpreted with the consideration of some limitations. First, model‐estimated exposures are surrogates for personal exposure, which depends on the time spent indoors, daily activity patterns, and workplace exposure. Exposure measurement error may underestimate the underlying associations between air pollution and arrhythmias.

Second, arrhythmias were detected from a single 10‐second electrocardiogram recording. Consequently, we were more likely to detect arrhythmias that were persistent or that occurred frequently, and may have missed episodes of paroxysmal arrhythmias, including paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. We were also unable to differentiate between long‐term disease and observation of acute events because of the limited duration of ECG. Furthermore, we do not have data on PR, QRS, and corrected QT intervals, which could better quantify the underlying arrhythmic abnormalities.

Third, our study population was relatively young, healthy, and highly educated, which reduces the risk of selection bias because of competing risks and the risk of confounding becasue of the presence of comorbidities or medication use; thus, our results may not be generalized to other populations.

Our study suggests that PM air pollution is associated with increased incidence of bradycardia, RBBB, and premature atrial contraction arrythmias in the general population. The dose‐response trend highlights the importance and potential opportunities for reducing the burden of arrythmias, as exposure to PM air pollution is chronic. Prevention and treatment of cardiac arrythmias might benefit from the identification of relevant pathophysiological pathways associated with PM air pollution.

Conclusions

In this large cohort of middle‐aged men and women, exposure to long‐term PM10 air pollution was independently associated with an increased risk of bradycardia and premature ventricular contractions, and PM2.5 with an increased risk of bradycardia and RBBB. Future studies are needed to understand the underlying mechanistic pathways, the interactions between PM exposure and other traditional CVD risk factors, and the benefits of PM reduction on cardiac rhythmicity.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S3

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank TS Choi (Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Information System, Seoul, Korea) for his help with technical support in gathering data. All authors listed made substantial contributions to the article presented here.

Zhang contributed to data analysis, reporting and drafting the work; Zhao and Shin contributed to planning, data analysis, and revising the work; Kang, Hong, Chang, Ryu, Park, Cho, Guallar, Shin, and Zhao contributed to revising and final approval of the work.

(J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016885 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016885.)

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.120.016885

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

Contributor Information

Ho Cheol Shin, Email: hcfm.shin@samsung.com.

Di Zhao, Email: dizhao@jhu.edu.

References

- 1. Brugada J, Katritsis DG, Arbelo E, Arribas F, Bax JJ, Blomström‐Lundqvist C, Calkins H, Corrado D, Deftereos SG, Diller G‐P, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardiathe task force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): developed in collaboration with the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:655–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dresen WF, Ferguson JD. Ventricular arrhythmias. Cardiol Clin. 2018;36:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zimetbaum P. Atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:ITC33–ITC48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lau DH, Nattel S, Kalman JM, Sanders P. Modifiable risk factors and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2017;136:583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Song X, Liu Y, Hu Y, Zhao X, Tian J, Ding G, Wang S. Short‐term exposure to air pollution and cardiac arrhythmia: a meta‐analysis and systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:642–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Song X, Liu Y, Hu Y, Zhao X, Tian J, Ding G, Wang S. Short‐term exposure to air pollution and cardiac arrhythmia: a meta‐analysis and systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Folino F, Buja G, Zanotto G, Marras E, Allocca G, Vaccari D, Gasparini G, Bertaglia E, Zoppo F, Calzolari V. Association between air pollution and ventricular arrhythmias in high‐risk patients (ARIA study): a multicentre longitudinal study. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1:e58–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Metzger KB, Klein M, Flanders WD, Peel JL, Mulholland JA, Langberg JJ, Tolbert PE. Ambient air pollution and cardiac arrhythmias in patients with implantable defibrillators. Epidemiology. 2007;18:585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shin S, Burnett RT, Kwong JC, Hystad P, van Donkelaar A, Brook JR, Goldberg MS, Tu K, Copes R, Martin RV, et al. Ambient air pollution and the risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke: a population‐based cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127:87009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim IS, Yang PS, Lee J, Yu HT, Kim TH, Uhm JS, Pak HN, Lee MH, Joung B. Long‐term exposure of fine particulate matter air pollution and incident atrial fibrillation in the general population: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2019;283:178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Z, Zhao D, Hong YS, Chang Y, Ryu S, Kang D, Monteiro J, Shin HC, Guallar E, Cho J. Long‐term particulate matter exposure and onset of depression in middle‐aged men and women. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127:77001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yanosky JD, Paciorek CJ, Laden F, Hart JE, Puett RC, Liao D, Suh HH. Spatio‐temporal modeling of particulate air pollution in the conterminous united states using geographic and meteorological predictors. Environ Health. 2014;13:63–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andersen K, Farahmand B, Ahlbom A, Held C, Ljunghall S, Michaelsson K, Sundstrom J. Risk of arrhythmias in 52 755 long‐distance cross‐country skiers: a cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3624–3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. D'Agostino RB, Lee ML, Belanger AJ, Cupples LA, Anderson K, Kannel WB. Relation of pooled logistic regression to time dependent cox regression analysis: the Framingham Heart Study. Stat Med. 1990;9:1501–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fiordelisi A, Piscitelli P, Trimarco B, Coscioni E, Iaccarino G, Sorriento D. The mechanisms of air pollution and particulate matter in cardiovascular diseases. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carll AP, Crespo SM, Filho MS, Zati DH, Coull BA, Diaz EA, Raimundo RD, Jaeger TNG, Ricci‐Vitor AL, Papapostolou V, et al. Inhaled ambient‐level traffic‐derived particulates decrease cardiac vagal influence and baroreflexes and increase arrhythmia in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2017;14:16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Samet JM, Rappold A, Graff D, Cascio WE, Berntsen JH, Huang Y‐CT, Herbst M, Bassett M, Montilla T, Hazucha MJ. Concentrated ambient ultrafine particle exposure induces cardiac changes in young healthy volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:1034–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Link MS, Luttmann‐Gibson H, Schwartz J, Mittleman MA, Wessler B, Gold DR, Dockery DW, Laden F. Acute exposure to air pollution triggers atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:816–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dharod A, Soliman EZ, Dawood F, Chen H, Shea S, Nazarian S, Bertoni AG; Investigators M . Association of asymptomatic bradycardia with incident cardiovascular disease and mortality: the Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peel JL, Klein M, Flanders WD, Mulholland JA, Freed G, Tolbert PE. Ambient air pollution and apnea and bradycardia in high‐risk infants on home monitors. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:1321–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Devlin R, Ghio A, Kehrl H, Sanders G, Cascio W. Elderly humans exposed to concentrated air pollution particles have decreased heart rate variability. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:76s–80s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Metayer P, Clementy J. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ofoma U, He F, Shaffer ML, Naccarelli GV, Liao D. Premature cardiac contractions and risk of incident ischemic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e002519 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.112.002519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He F, Shaffer ML, Rodriguez‐Colon S, Yanosky JD, Bixler E, Cascio WE, Liao D. Acute effects of fine particulate air pollution on cardiac arrhythmia: the APACR study. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:927–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Neal WT, Soliman EZ, Efird JT, Judd SE, Howard VJ, Howard G, McClure LA. Fine particulate air pollution and premature atrial contractions: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2017;27:271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Van Hee VC, Szpiro AA, Prineas R, Neyer J, Watson K, Siscovick D, Kyun Park S, Kaufman JD. Association of long‐term air pollution with ventricular conduction and repolarization abnormalities. Epidemiology. 2011;22:773–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pope CA III, Dockery DW. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2006;56:709–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dockery DW, Luttmann‐Gibson H, Rich DQ, Link MS, Mittleman MA, Gold DR, Koutrakis P, Schwartz JD, Verrier RL. Association of air pollution with increased incidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias recorded by implanted cardioverter defibrillators. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:670–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berger A, Zareba W, Schneider A, Ruckerl R, Ibald‐Mulli A, Cyrys J, Wichmann HE, Peters A. Runs of ventricular and supraventricular tachycardia triggered by air pollution in patients with coronary heart disease. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:1149–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S3