Abstract

Non-typhoidal Salmonella present a major threat to animal and human health as food-borne infectious agents. We characterized 91 bacterial isolates from Armenia and Georgia in detail, using a suite of assays including conventional microbiological methods, determining antimicrobial susceptibility profiles, matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry, serotyping (using the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme) and genotyping (repetitive element sequence-based PCR (rep-PCR)). No less than 61.5% of the isolates were shown to be multidrug-resistant. A new antimicrobial treatment strategy is urgently needed. Phage therapy, the therapeutic use of (bacterio-) phages, the bacterial viruses, to treat bacterial infections, is increasingly put forward as an additional tool for combatting antibiotic resistant infections. Therefore, we used this representative set of well-characterized Salmonella isolates to analyze the therapeutic potential of eleven single phages and selected phage cocktails from the bacteriophage collection of the Eliava Institute (Georgia). All isolates were shown to be susceptible to at least one of the tested phage clones or their combinations. In addition, genome sequencing of these phages revealed them as members of existing phage genera (Felixounavirus, Seunavirus, Viunavirus and Tequintavirus) and did not show genome-based counter indications towards their applicability against non-typhoidal Salmonella in a phage therapy or in an agro-food setting.

Keywords: Salmonella, foodborne pathogens, Armenia, Georgia, bacteriophages, phage therapy, antibiotic resistance, genotyping, genome sequencing, clinical isolates

1. Introduction

Food and water-borne diseases represent a growing public health problem worldwide, in both animals and humans. An increasing number of people are at risk of foodborne bacterial infections, often causing severe or even fatal diarrheal diseases, with 550 million people getting ill annually, including 220 million children under the age of five [1]. Salmonella is one of the main causative agents of food-borne infections. This ubiquitous and increasingly antibiotic-resistant bacterium [2] can survive several weeks in dry environments and several months in water. While a typical Salmonella infection can be resolved without medical treatment, severe cases can have a lethal outcome in the absence of adequate antibiotic treatment.

Drug resistance in non-typhoidal Salmonella has been on the rise since 1996 [3]. In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) included fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella spp. in its high-priority pathogens list to guide research and development of new antibiotics [4]. Injudicious use of antimicrobials in veterinary medicine and agriculture has led to multidrug resistance in zoonotic Salmonella. Infections caused by resistant strains were found to be more severe, with lower treatment efficacy and higher hospitalization rates [3]. In the worst cases, bacteria spread from the intestines to the bloodstream, causing life-threatening Salmonella bacteremia. Certain serotypes are more prone to cause such invasive infections. The United States Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analyzed blood and stool Salmonella isolates obtained through their surveillance systems in the period 2004–2012 [5] and estimated the overall incidence of resistant Salmonella infections as roughly 2 for 100,000 persons per year, with the majority (73%) of the clinically important antimicrobial resistance (AMR) linked to four major Salmonella serotypes: Enteritidis, Newport, Typhimurium, and Heidelberg.

In February 2018, sixteen people were diagnosed with severe Salmonella food poisoning in Tbilisi, Georgia [6]. This outbreak was associated with chicken burgers sold in a supermarket of a well-known multinational retailer. The Georgian CDC identified the patients’ isolates as Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Agona (O:4,12; H1:f,g,s; H2:1,2), according to the Kauffmann-White classification. All isolates showed resistance to ampicillin, two isolates also showed intermediate resistance to nalidixic acid, and one isolate showed a multidrug-resistance phenotype, exhibiting resistance against ampicillin, tetracycline, and nalidixic acid, and intermediate resistance to ciprofloxacin and azithromycin. This example again illustrates that non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica is a leading cause of food poisoning in both developed and developing countries and that the emergence of multidrug resistant (MDR) strains represents an additional threat to public health. In the present study, we characterized 91 clinical Salmonella isolates, comprising determination of genotype distribution and antibiotic and phage susceptibility profiles. Almost two thirds of the isolates (61.5%, 56/91) were shown to be MDR with 18 isolates (19.7%) showing resistance to third generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones.

Therefore alternative means of treatment and prevention of salmonellosis are urgently needed.

Bacteriophages (phages) are considered as additional or complementary tools in the fight against MDR bacteria. Personalized Phage Therapy (PT) has been practiced in Georgia, Russia and Poland for nearly a century [7]. A number of phage preparations (such as Pyo and Intesti Bacteriophage, Eliava Biopreparation, Tbilisi, Georgia), active against various bacterial infections, are available as an over the counter medicine in Georgia. Moreover, the potential of phages to control bacterial pathogens in the agro-food industry has led to the development and marketing of a number of phage products in the United States [8]. Several phage preparations have now been approved as biocontrol agents of food pathogens [9].

Because phages are highly specific and adaptive antimicrobial agents, the investigation and monitoring of target infections, and the creation and maintenance of bacterial collections of well-characterized and epidemiologically relevant clinical isolates, are crucial in generating potent phage preparations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Isolation and Identification of Salmonella Isolates

One hundred and sixteen bacterial isolates from fecal samples of patients with suspected salmonellosis were obtained from the “Nork” Republican Infectious Clinical Hospital (Yerevan, Armenia; n = 77), the Infectious Diseases and AIDS Center (Tbilisi, Georgia; n = 25), and the Municipal Infectious Diseases Hospital (Dushanbe, Tajikistan; n = 14). The initial diagnoses of salmonellosis were based on clinical presentations: symptom or group of symptoms observed or detected after initial examination or disclosed by a patient to the physician, as well as laboratory analyses. Clinical presentations (anamnesis morbi) consistent with gastroenteritis were diarrhea, fever, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps. For the present investigation, only patients without any therapeutic interference before their hospitalization were selected.

Routine bacteriological analysis of fecal samples was performed. Samples were placed in sterile bottles and processed within one hour after collection. Approximately 0.9 g of fecal material was diluted 1:10 in 0.9% NaCl. Serial 100-fold dilutions of the fecal samples were inoculated on petri plates with Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) selective agar (Oxoid Limited, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated for 24 to 48 h at 37 °C. Bacterial identification of the obtained isolates was verified by brightfield microscopy at a ×1000 magnification of Gram-stained bacteria [10]. The nutritional and metabolic capabilities of the isolates were determined to define their genus and species identity. Tests establishing glucose fermentation, urease presence, indole production, H2S production, and fermentation of galactitol (dulcitol) were performed according to the UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations [11].

2.2. MALDI-TOF MS Identification

Genus level identification of bacterial isolates was performed by matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS, MicroFlex™, Bruker Daltonik, MA, USA). Freshly grown bacterial colonies were distributed on a ground steel MALDI target plate using a 1 μL disposable loop. The microbial smears were air-dried and overlaid with 1 μL Bruker IVD Matrix HCCA and further air-dried for 5 min at room temperature. The Bruker MicroFlex instrument was operated using FlexControl 3.0 software (Bruker Daltonik, MA, USA). External calibration of the instrument was performed using the Bacterial Test Standard (BTS, Bruker Daltonik, MA, USA) [12].

2.3. Serological Characterization of Salmonella Isolates

Serotyping of isolates was performed in accordance with the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme [13], using polyvalent antisera for flagellar (H) and lipopolysaccharide (O) antigens.

2.4. Molecular Typing of Salmonella Isolates

Molecular typing of Salmonella isolates was performed by a semi-automated repetitive element sequence-based PCR (rep-PCR) system (DiversiLab® System, bioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France). DNA was extracted using the UltraClean™ Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories Inc., Solana Beach, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Rep-PCR was performed using a PTC 200 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk a/d Ijssel, The Netherlands) and the Salmonella fingerprinting kit (Bacterial Barcodes, bioMérieux, Athens, GA, USA). The reaction mixture (total volume 25 μL) consisted of 18 μL rep-PCR MM1, 2.5 μL of Gene Amp PCR buffer 10×, 2 μL of primer Mix, 0.5 μL of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk a/d Ijssel, The Netherlands) and 2 μL of genomic DNA. Thermal conditions: an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles including denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 50 °C for 30 s and extension at 70 °C for 90 s, followed by a final extension step at 70 °C for 3 min. The amplified fragments were separated by electrophoresis using a microfluidic lab-chip. Electropherograms were automatically analyzed using DiversiLab software (version 3.4) (bioMérieux, Brussels, Belgium). All fingerprint patterns were normalized; Pearson correlation (PC) was used to calculate the distance matrices among all samples. Relying on unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) clustering and multidimensional scaling, the DiversiLab software created a customized report presenting a dendrogram, electropherograms, virtual gel images and scatter plots. Relatedness among isolates was deduced as previously described [14]; isolates showing similarity levels above 95% were considered as linked, while isolates with similarity levels below 95% were considered as distinct [15].

2.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Salmonella Isolates

The antibiotic susceptibility of the bacterial isolates was determined using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method [16]. The following antibiotic disks (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy) were used: ampicillin (AMP, 10 µg), amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (AUG, 20 µg/10 µg), azithromycin (AZI, 15 µg), ceftriaxone (CRO, 30 µg), chloramphenicol (C, 30 µg), ciprofloxacin (CIP, 5 µg), nalidixic acid (NAL, 30 µg), streptomycin (SM, 10 µg), tetracycline (TE, 30 µg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (T/S, 1.25 µg/23.75 µg), and sulfamethoxazole (S3, 300 µg). Susceptibility testing results were interpreted based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria [17].

2.6. Bacteriophages and the Propagation Bacterial Strains Used in the Study

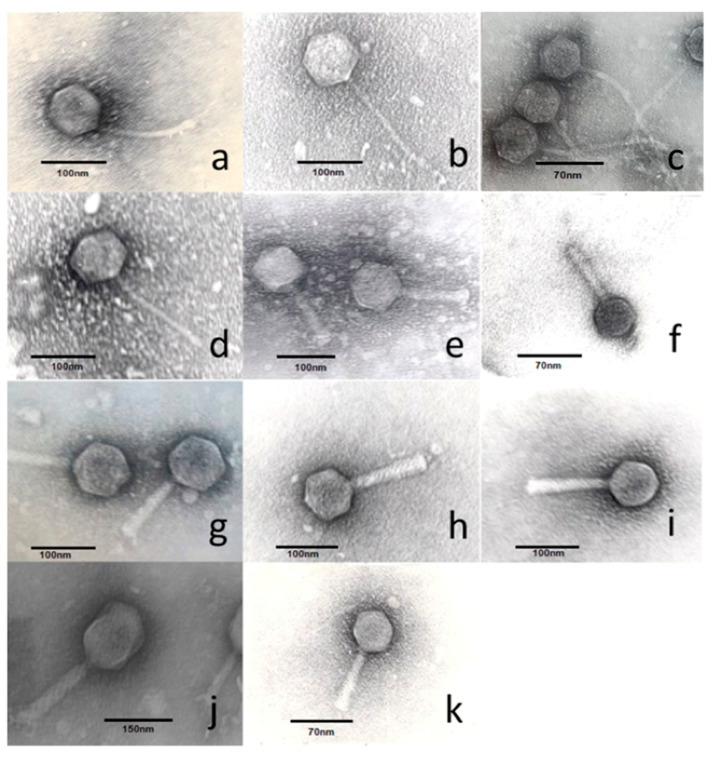

Eleven Salmonella specific single phage clones (GEC_vB_B1, GEC_vB_GOT, GEC_vB_N6, GEC_vB_N7, GEC_vB_N5, GEC_vB_N3, GEC_vB_NS7, GEC_vB_B3, GEC_vB_BS, GEC_vB_MG, GEC_vB_N8) (Table 1 and Figure 1) and three Salmonella specific phage cocktails, that were designed using different combinations of three clones selected from the set of eleven phage clones (BTR1, BTR2, BTR3) (Table 2), were screened for activity against the above-mentioned collection of Salmonella isolates. These phages were isolated from different environmental sources during the period 2013–2015 (Table 1). Three different bacterial strains (Table 3) were used to propagate the eleven individual phages.

Table 1.

List of bacteriophages used in the study.

| Phage Name | Genus (Morphology) | Size of Phage Head/Tail (nm) | Genome Size (kb) | NCBI Closest Match | NCBI Query Coverage (%) | NCBI Percent Identity (%) | Isolation Year | Isolation Source/Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEC_vB_N3 | Tequintavirus (Siphoviridae) | 68/140 | 110 | Salmonella phage 1-29 | 79 | 97 | 2013 | River Mtkvari, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_N5 | Tequintavirus (Siphoviridae) | 90/231 | 149 | E. coli phage T5 | 86 | 97 | 2013 | River Mtkvari, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_N7 | Tequintavirus (Siphoviridae) | 87/136 | 112 | Salmonella phage 1-29 | 81 | 95 | 2013 | River Mtkvari, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_N8 | Tequintavirus (Siphoviridae) | 77/168 | 51 | E. coli phage SPC35 | 84 | 92 | 2013 | River Mtkvari, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_N6 | Viunavirus (Myoviridae) | 104/140 | 158 | Salmonella phage STML-13-1 | 90 | 98 | 2013 | River Mtkvari, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_NS7 | Felixounavirus (Myoviridae) | 63/109 | 55 | Salmonella phage Mushroom | 96 | 99 | 2015 | Cow raw milk, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_MG | Seunavirus (Myoviridae) | 95/104 | 142 | Salmonella phage PVP-SE1 | 89 | 96 | 2013 | Sewage water, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_BS | Felixounavirus (Myoviridae) | 77/118 | 86 | Salmonella phage Mushroom | 98 | 98 | 2013 | Black Sea, Batumi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_B1 | Felixounavirus (Myoviridae) | 81/122 | 87 | Salmonella phage Mushroom | 96 | 98 | 2013 | River Mtkvari, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_GOT | Viunavirus (Myoviridae) | 90/119 | 157 | Salmonella phage STML-13-1 | 90 | 99 | 2013 | Sewage water, Tbilisi, Georgia |

| GEC_vB_B3 | Felixounavirus (Myoviridae) | 72/113 | 87 | Salmonella phage Mushroom | 96 | 98 | 2013 | River Mtkvari, Tbilisi, Georgia |

Figure 1.

Transmission electron micrographs of bacteriophages used in this study. (a) GEC_vB_N3; (b) GEC_vB_N5; (c) GEC_vB_N7; (d) GEC_vB_N8; (e) GEC_vB_N6; (f) GEC_vB_NS7; (g) GEC_vB_MG; (h) GEC_vB_BS; (i) GEC_vB_B1; (j) GEC_vB_GOT; (k) GEC_vB_B3.

Table 2.

Composition of the phage cocktails.

| Name of Cocktail | Name of Phages |

|---|---|

| Mix_BTR1 | GEC_vB_MG, GEC_vB__N7, GEC_vB_N5 |

| Mix_BTR2 | GEC_vB_N7, GEC_vB_N5, GEC_vB_N6 |

| Mix_BTR3 | GEC_vB_MG, GEC_vB_N7, GEC_vB_N6 |

Table 3.

Bacterial strains used for propagation of phages.

| Strain ID | Species/Serotype | Isolation Source | Isolation Place | Isolation Year | Propagated Phages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SeE.3 | S. enterica Enteritidis | Pig feces | Pig farm, South Korea | 2011 | GEC_vB_N3, GEC_vB_N8, GEC_vB_N5, GEC_vB_MG |

| SeT.4 | S. enterica Typhimurium | Pig feces | Pig farm, South Korea | 2011 | GEC_vB_N7, GEC_vB_GOT, GEC_vB_BS |

| SeT.6 | S. enterica Typhimurium | Pig feces | Pig farm, South Korea | 2011 | GEC_vB_N6, GEC_vB_NS7, GEC_vB_B3, GEC_vB_B1 |

2.7. Phage Isolation

Isolation of Salmonella specific phages was performed using the bacterial strain enrichment method [18]. Ten ml of 10× concentrated lysogeny broth (LB, Oxoid Limited, Basingstoke, UK) was pipetted into a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask, 90 mL of the water/milk sample was added and the mixture was inoculated with 1 mL of overnight culture of host bacteria (Table 3). The flask was incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. Then the mixture was centrifuged at 6000× g for 30 min at 4 °C and supernatant was filtered through 0.45 or 0.22 µm filters and tested for the presence of phages by a spot test on bacterial streaks [19]. Overnight host bacterial cultures were diluted in the sterile LB to a final concentration of 107 colony forming units (cfu)/mL and streaks were made on 2% LB agar plates using a 10 µL loopful of each strain, and air-dried for 10–15 min. Ten µL of each filtered enrichment sample was applied on each streak. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h and phage presence was assessed based on visualization of clear spots on the bacterial growth.

2.8. Preparation of High-Titer Phage Stocks

To prepare high-titer phage stocks, 0.1 mL containing 106 plaque forming units (pfu) of phages was mixed with 0.1 mL of 107 cfu of host bacteria. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min and 3–5 mL of 0.7% LB agar at 45 °C was added. The mixture was immediately poured into plates containing 30 mL of solid 2% LB agar. Plates were incubated for 18 to 24 h at 37 °C. When semi-confluent lysis occurred, the top (soft) agar was gently scraped off and collected into a sterile centrifuge tube using a sterile bent Pasteur pipette. The tube was centrifuged at 6000× g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was filtered through 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm filters. The obtained phage stocks were highly concentrated (1010 to 1011 pfu/mL)

2.9. Bacteriophage Susceptibility Test

Assessment of phage activity against different bacterial strains was performed using the parallel streaks method [19,20] with minor modifications. Briefly, overnight bacterial cultures and phage stocks were diluted in the sterile LB to a final concentration of 107 cfu/mL and 106 pfu/mL respectively. Bacterial streaks were made on 2% LB agar plates using a 10 µL loopful of each bacterial isolate and air-dried for 10–15 min. Five µL of each phage clone and cocktail was applied on each streak. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h and results were recorded. Phage activity was assessed based on visualization. Confluent lysis (CL), semi-confluent lysis (SCL), opaque lysis (OL), countable number of phage plaques on the phage application spots (“taches vierges”, TV) was considered as positive result. Uninterrupted bacterial growth on the spot was recorded as resistant (R). The probability of false-positive phage infection due to lysate impurities (e.g., bacterial toxins) or “lysis from without” was reduced by using defined media and phage production hosts known not to contain bacterial growth suppressing agents in their lysates. In addition, low phage concentration (106 pfu/mL), obtained by dilution of highly concentrated phage stocks (see Section 2.8)—thus strongly diluting potential impurities—were tested. Finally, the spot test often resulted in a countable amount of single phage plaques (TV in Table S1).

2.10. Sequencing and Analysis of Phage Genomes

Phage DNA was extracted from a high-titer phage stock by a phenol/chloroform extraction, according to Sambrook and Russell [21]. The phage genomes were subsequently sequenced using an in-house MiniSeq Illumina NGS platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The Nextera Flex DNA Library Kit (Illumina) was used for the library prep of the DNA and the concentration was determined with a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After sequencing, trimming and genome assembly was done using the PATRIC (v 3.6.6) server [22]. Using MEGA X [23], phage genomes were aligned to the closest type species as identified by BLASTn [24]. Next, they were annotated using RASTtk [25] and manually curated by BLASTp. Finally, the phage genomes were visualized using EasyFig [26] and SNP variants were called using iVar [27].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation, Identification and Characterization of Salmonella Isolates

A total of 116 bacterial isolates were collected from non-antibiotic-treated patients with presumed salmonellosis in three different countries (Section 2.1). Initially, all 116 isolates were identified as Salmonella spp., based on conventional microbiological and biochemical methods. Further MALDI-TOF MS analysis provided a more reliable genus level identification. Ninety-one isolates were confirmed to be Salmonella spp., while 25 isolates (14 from Tajikistan, five from Georgia and six from Armenia) appeared to be non-Salmonella isolates and were excluded from further analysis. Identification on the species level could not be done by MALDI-TOF and serological testing identified at least 86 of the 91 isolates as S. enterica subsp. enterica.

More specifically, serotyping based on the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme showed dominance of the Typhimurium serotype among clinical isolates from Georgia and Armenia (no Salmonella isolates from Tajikistan could be retained for further analysis). A total of 54 isolates were identified as S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium, among which ten originated from Georgia and 44 from Armenia. The remaining 10 Georgian and 22 Armenian isolates belonged to the S. Enteritidis serotype. For five Armenian isolates, serotypes could not be defined and they were assigned as Salmonella spp. We observed an even distribution of two serotypes for Georgian clinical isolates and an increased prevalence of S. Typhimurium in isolates from Armenia.

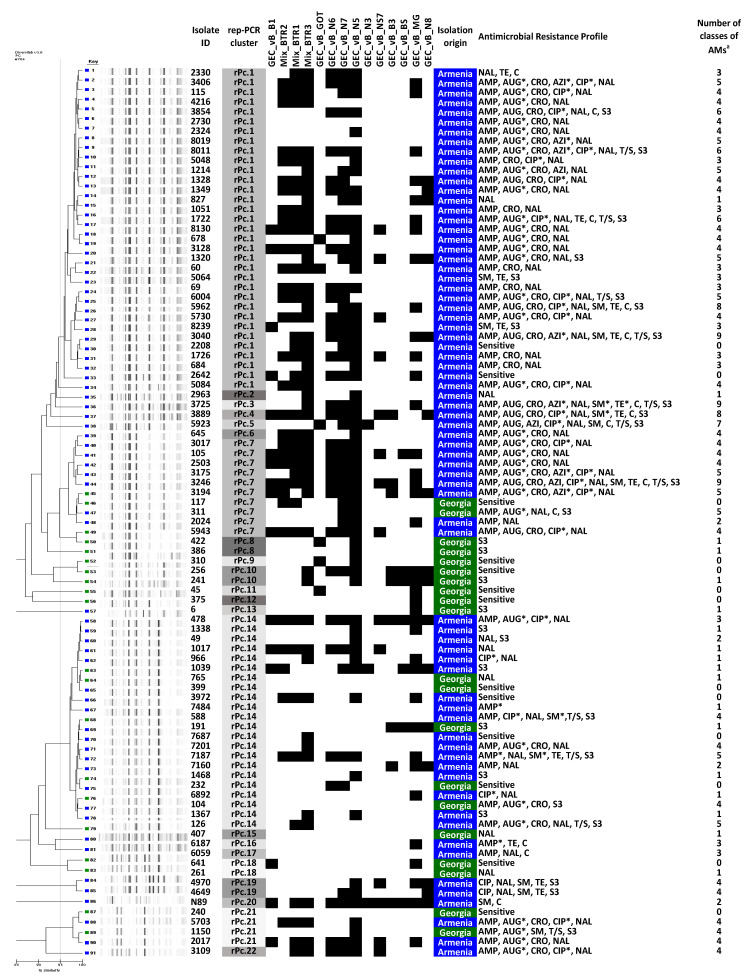

Rep-PCR analysis of the 91 confirmed Salmonella isolates revealed 22 distinct genotypic clusters. Three clusters were mixed, harboring both Georgian and Armenian isolates. Cluster rPc.7 consisted of two isolates of Georgian and eight isolates of Armenian origin. Cluster rPc.21 contained two Georgian and two Armenian isolates and cluster rPc.14 contained five Georgian and 17 Armenian isolates (Figure 2). Twenty Georgian isolates clustered in 11 rep-PCR genotypes, of which five were represented by a single strain, and the 71 isolates from Armenia clustered in 14 rep-PCR genotypes, of which nine were represented by a single strain (Figure 2). There was no correlation between rep-PCR cluster compositions and geographical origin or isolation time.

Figure 2.

Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) dendrogram of rep-PCR fingerprinting profiles, with corresponding phage typing and AM profiles. The report produced by the DiversiLab software truncated the dendrogram to only show relationships with similarities above 85%. a Number of classes of AMs to which the isolate showed resistant or intermediate phenotype; * Intermediate susceptibility to AMs. Black nods represent resistance to given phages. Rep PCR clusters are color coded for representation. AM, antimicrobial; AMP, ampicillin; AUG, amoxicillin + clavulanic acid; AZI, azithromycin; C, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CRO, ceftriaxone; NAL, nalidixic acid; SM, streptomycin; TE, tetracycline; T/S, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; S3, sulfonamides.

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

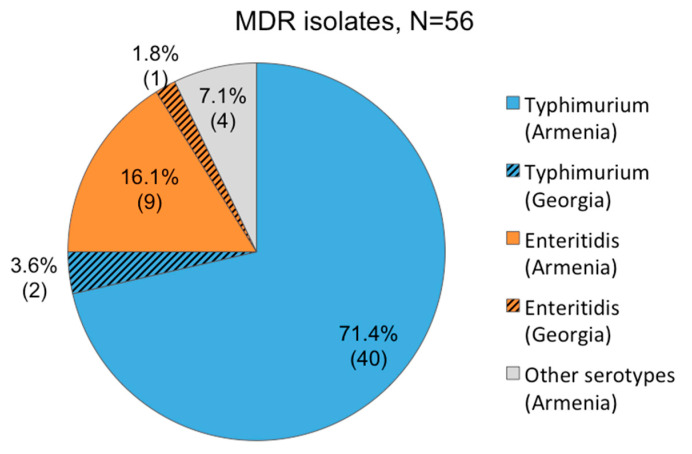

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed on the 91 MALDI-TOF confirmed Salmonella isolates. Strains were considered as MDR when they showed resistance to representatives of at least three antibiotic classes [28]. Distribution of MDR isolates and their antimicrobial resistance profiles are presented in Figure 3 and Table S1. Only three isolates (15%, 3/20) from Georgia exhibited MDR profiles, whereas 53 isolates (74.6%, 53/71) from Armenia were shown to be MDR. The highest levels of resistance among the MDR isolates were observed for nalidixic acid (91.07%, 51/56), the first of the synthetic quinolones, for ampicillin (91.1%, 51/56), for the third-generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone (75%, 42/56), for amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (73.2%, 41/56), for the fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin (42.9%, 24/56), and for sulfonamide (37.5%, 21/56). An alarming number of isolates showed resistance against antibiotics that are most commonly used to treat Salmonella infections, such as third-generation cephalosporins (42 isolates) and fluoroquinolones (24 isolates). Eighteen of the MDR isolates (32.14%, 18/56) showed simultaneous resistance to these classes of antimicrobials. The broadest resistance spectrum was observed in three S. Typhimurium isolates from Armenia, which showed resistance against nine antibiotic classes. The most effective antibiotics, at least in vitro, were azithromycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole with 89.0% (81/91) of isolates showing susceptibility. The least effective was nalidixic acid with only 31.9% (29/91) of isolates exhibiting susceptibility to this antimicrobial agent. Only nine isolates from Georgia and four isolates from Armenia were shown to be sensitive to all antibiotics tested in this study.

Figure 3.

Serotype distribution in multidrug resistant (MDR) Salmonella enterica isolates isolated from patients with salmonellosis in Armenia (53 isolates) and Georgia (three isolates).

3.3. Susceptibility of Salmonella Isolates to Different Phages

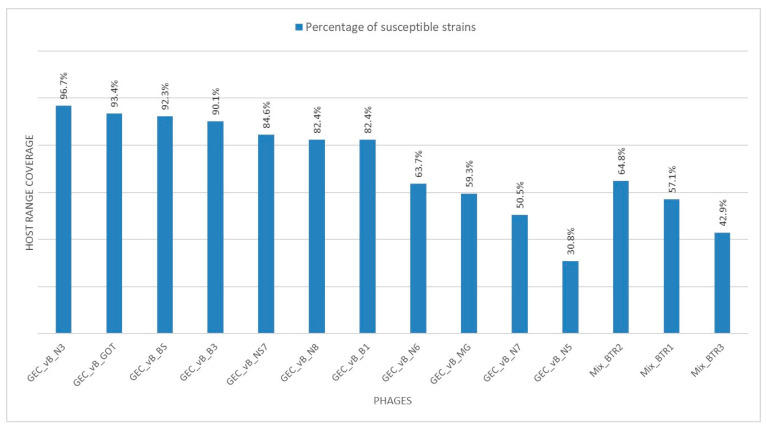

All 91 confirmed Salmonella isolates were tested for susceptibility to 11 single phage clones and three phage cocktails (Table 1 and Table 2). Of these 11 phage clones, eight were previously shown to have a broad host range against 226 Salmonella isolates of veterinary and human origin [29]. Three phages, GEC_vB_GOT, GEC_vB_N6, GEC_vB_N7, have not been reported before. In the present study, all 91 tested Salmonella isolates were found to be susceptible to at least one phage. None of the tested strains showed total phage resistance. Figure 4 and Table S1 show the host range coverage of the used phages.

Figure 4.

Host range coverages of 11 phage clones and 3 phage cocktails to 91 Salmonella isolates from the Caucasus.

The broadest host range (more than 95% of isolates lysed) was observed for siphovirus GEC_vB_N3. Interestingly, four of the eleven phages screened in this study, GEC_vB_BS, GEC_vB_B1, GEC_vB_B3 and GEC_vB_MG, showed activity against different Shigella spp. and Escherichia coli isolates, suggesting polyvalency consistent with related species [30].

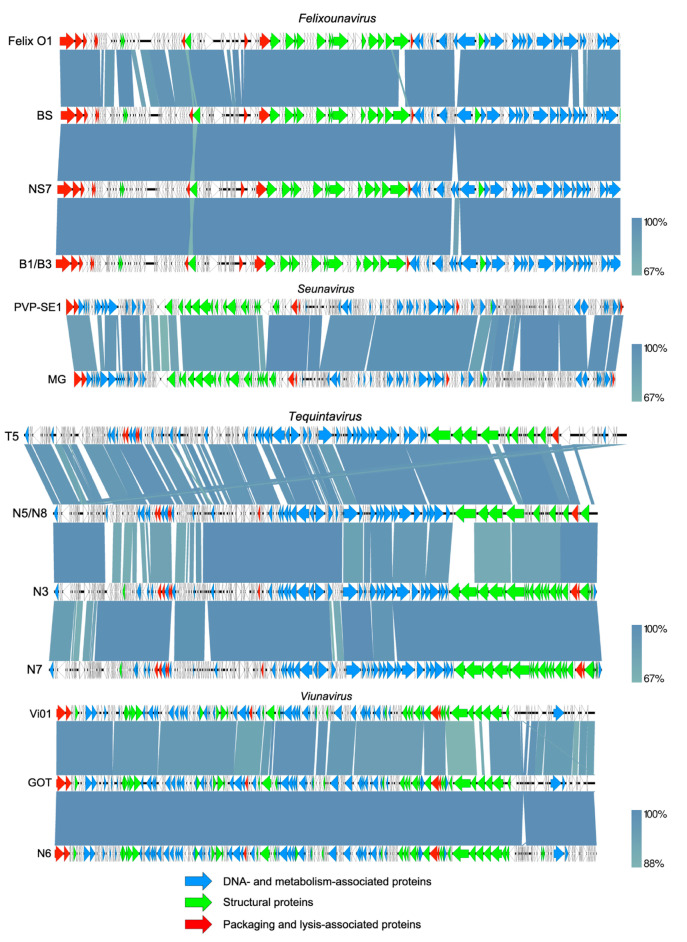

All phages were sequenced individually and their genomes showed high similarities to known phage sequences (Table 1). Phage genome fold coverages ranged from 112X to 364X and all assemblies resulted in circular contigs. The annotated sequences were deposited to NCBI and are available via Genbank accession numbers MW006474 through MW006482. They can be classified in four different genera: Felixounavirus (GEC_vB_BS, GEC_vB_NS7, GEC_vB_B1 and GEC_vB_B3), Seunavirus (GEC_vB_MG), Viunavirus (GEC_vB_GOT and GEC_vB_N6) and Tequintavirus (GEC_vB_N5, GEC_vB_N8, GEC_vB_N3 and GEC_vB_N7). The phage genomes were therefore aligned to the type species, representing each genus, and annotated (Figure 5). None of the phages encode genes associated with known lysogeny or virulence and antibiotic resistance determinants. Two morphological types are represented in the analyzed phage set: Myoviridae (n = 7) and Siphoviridae (n = 4) (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Genome maps of the sequenced Salmonella phages and comparison using a BLASTn analysis. The phages can be classified in four different genera: Felixounavirus (GEC_vB_BS, GEC_vB_NS7, GEC_vB_B1 and GEC_vB_B3), Seunavirus (GEC_vB_MG), Tequintavirus (GEC_vB_N5, GEC_vB_N8, GEC_vB_N3 and GEC_vB_N7) and Viunavirus (GEC_vB_GOT and GEC_vB_N6). In red, genes encoding packaging and lysis-associated proteins are displayed, in green structural proteins and in blue DNA- and metabolism-associated proteins (adapted EasyFig). Each white or colored arrow represents a predicted open reading frame. Members of the Tequintavirus contain direct terminal repeats (DTR) of approximately 10 kb for their packaging strategy, which can be observed by the homology of the last part of the T5 genome to the start of the N5/N8 genomes. For visibility reasons, these redundant DTR regions were deleted from the Genbank files and the figure.

The four phages from the Felixounavirus, GEC_vB_BS, GEC_vB_NS7, GEC_vB_B1 and GEC_vB_B3 showed high similarity to the myo-virus Mushroom isolated from the Intestiphage preparation produced by the Eliava Institute [31]. These phages exhibited a broad host range, showing activity against 82%–92% of all tested isolates. Phage GEC_vB_B1 and GEC_vB_B3 are very closely related. When comparing the latter to B1, a heterogenous population can be observed, only displaying some SNPs at a relatively low frequency, which might explain their differences in host range (Table S2). Representatives of the Felix O1-like viruses are well-known, strictly virulent phages active against various enterobacteria, including E. coli and Salmonella spp. Three out of four phages representing the Felixounavirus genus (excluding GEC_vB_NS7), also showed multi species activity. One of the characteristics of the phages from this genus, is a relatively large number of tRNAs (>20) [32], which is also observed in the newly sequenced phage genomes.

Seunavirus GEC_vB_MG exhibited a host range of 59.3 % and contains a genome of 142 kb, which showed similarity to the Salmonella phages PVP-SE1, the type species of this genus, and to SSE121. Similar to phage PVP-SE1, phage GE_vB_MG not only infects different serotypes of Salmonella [33], but also E. coli and Shigella strains. Phage SSE121 is also known for its activity against Salmonella serotypes of high public health importance, including S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, S. Heidelberg, S. Newport, and S. Hadar. Because of this ability, phage SSE121 is included in the SalmoFresh™ anti-microbial preparation (Intralytix, Baltimore, MD, USA), used for the biocontrol of Salmonella in different types of food products.

Phages GEC_vB_N6 and GEC_vB_GOT, respectively with an intermediate (63.7%) and a broad host range (93.4%), showed similarity to representatives of the genus Viunavirus, which includes Salmonella phages STML-13-1 (98.54% nucleotide identity), Vi01 (96.18%) and PhiSH19 (91.69%). Phage STML-13-1 is known for its broad host range and it is also included in the above-mentioned SalmoFresh™ preparation. Phages Vi01 and PhiSH19 are interesting because of their tail spike proteins [34]. According to Hooton et al. 2011, the variety in number or structure of tail spike protein modules determines host range specificity in the Vi01-like phage genus. Three tail spike protein genes have also been identified within the genomes of phages GOT and N6. Two of them (GOT_Gp163 or N6_Gp179 and GOT_Gp166 or N6_Gp182) reveal high similarity to Vi01 Tsp1 (84.99 and 86.74% identity, respectively) and the Vi01 hemolysin-type calcium-binding protein (99.53% identity), respectively. The second predicted tail spike protein (GOT_Gp165 and N6_Gp181), on the other hand, is similar to the tail spike protein of phage Marshall (86.10% identity), with beta helix/pectin lyase domains resembling the ones found in the tail spikes of the well-known Salmonella phage P22 [35]. No genes associated with either toxicity, lysogenicity or antibiotic resistance were found in any phages of the Vi01 genus [31].

The last four phages, GEC_vB_N5, GEC_vB_N8, GEC_vB_N3 and GEC_vB_N7, all belong to the Tequintavirus genus, which includes the well-known E. coli lytic phage T5 and a number of Salmonella phages, such as SPC35, Stitch, Shivani and others [36]. However, these phages revealed very different host ranges. GEC_vB_N5 showed activity against only 30.8% of the tested isolates, while GEC_vB_N8 lysed up to 82.4% of isolates. Activity of GEC_vB_N7 represents 50.5% while GEC_vB_N3 is the most active phage compared to other phages used in this study, lysing 96.7% of strains. On the genome level, however, phage GEC_vB_N5 and GEC_vB_N8 are very closely related. Similar to B1/B3, a heterogenous population can be observed, only displaying a few SNPs at a relatively low frequency (Table S3).

The phage cocktails screened in this study were designed based on the host range distribution of the individual phages. The four phages used in the cocktails (GEC_vB_MG, GEC_vB_N5, GEC_vB_N6 and GEC_vB_N7) belonged to three different genera and showed relatively narrow host ranges (30.8–63.7%), but at the same time exhibited an activity against the isolates that were resistant to other more active phage clones. Hypothetically, mixtures of three of these phages could have host ranges of above 80% (Table S1). In practice, however, the cocktails showed reduced activity against the tested Salmonella isolates compared to some individual phage clone components (Table S1). For instance, cocktails Mix_BTR1 and Mix_BTR3 showed an activity of 57.1% and 42.9%, respectively, while the individual component phage GEC_vB_MG was active against 59.3% of the isolates. This emphasizes the fact that therapeutic phage cocktails are best not designed as a mixture of phages, selected solely on phage type and the sum of their individual host ranges [37,38,39]. In designing complex phage therapeutics, the synergetic and antagonistic activity of the different component phages should also be taken into account.

4. Conclusions

Clinical non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates obtained from the Caucasian region were characterized using phenotypical and molecular methods. Investigation of antibiotic resistance profiles showed an alarming rate of MDR Salmonella isolates, including resistance to the third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones, which are commonly and widely used in the treatment of severe Salmonella infections. Because of the increasing rate of AMR in clinical Salmonella isolates, new treatment strategies and methods are urgently needed. The application of phages as an additional tool for the treatment of MDR Salmonella infections seems to be plausible. Phages are natural and specific antibacterial agents, which can lyse bacteria irrespective of their AMR status, whilst leaving the commensal microflora unharmed. This is one of the main advantages of phages in comparison to antibiotics. The phages tested in this study showed potential for application in phage therapy against MDR Salmonella infections.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Giorgi Tsertsvadze for the electron micrographs.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/12/12/1418/s1, Table S1: Distribution of MDR isolates and their antimicrobial resistance profiles, Table S2: SNP variant analysis of GEC_vB_B3 and the closely related GEC_vB_B1 using iVar, Table S3: SNP variant analysis of GEC_vB_N8 and the closely related GEC_vB_N5 using iVar.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and J.-P.P.; methodology N.C., A.S., J.-P.P., R.L.; software, J.W. and C.L.; validation, D.D.V. and R.L.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, K.M., E.K., N.G., N.B., K.A., Z.K., M.Z., Z.G., A.M., G.N., D.V. and J.W.; resources, N.C., A.S., J.-P.P., R.L.; data curation, A.S., K.M., N.M. and E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, M.M., J.-P.P., D.D.V., R.L.; visualization, K.M., E.K. and J.W.; supervision, N.C. and J.-P.P.; project administration, N.C. and A.S.; funding acquisition, F.T. and N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception and writing of this paper.

Funding

This study was supported by project grant funding from the International Science and Technology Center (ISTC), and more specifically by project ISTC A-2140. MM was funded by the Royal Higher Institute for Defense. CL is supported by a PhD fellowship from FWO Vlaanderen (1S64720N).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Salmonella (Non-Typhoidal) [(accessed on 10 October 2020)];Newsroom. 2018 Feb 20; Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salmonella-(non-typhoidal)

- 2.Wang X., Biswas S., Paudyal N., Pan H., Li X., Fang W., Yue M. Antibiotic Resistance in Salmonella Typhimurium Isolates Recovered from the Food Chain Through National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System Between 1996 and 2016. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:985. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. [(accessed on 11 October 2020)];2019 Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf.

- 4.Shrivastava S.R., Shrivastava P.S., Ramasamy J. World Health Organization releases global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. J. Med. Soc. 2018;32:76. doi: 10.4103/jms.jms_25_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al F.M.E., Gu W., Mahon B.E., Judd M., Folster J., Griffin P.M., Hoekstra R.M. Estimated incidence of antimicrobial drug–resistant nontyphoidal Salmonella infections, United States, 2004–2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:29. doi: 10.3201/eid2301.160771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elashvili E., Mikadze G., Vepkhvadze N., Zurashvili B., Giorgobiani M., Lashkarashvili M. Food related Salmonellosis poisoning cases in Georgia and modern preventive methods. J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2018;4:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cisek A.A., Dąbrowska I., Gregorczyk K.P., Wyżewski Z. Phage therapy in bacterial infections treatment: One hundred years after the discovery of bacteriophages. Curr. Microbiol. 2017;74:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-1166-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sillankorva S.M., Oliveira H., Azeredo J. Bacteriophages and their role in food safety. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/863945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagel T.E., Chan B.K., De Vos D., El-Shibiny A., Kang’Ethe E.K., Makumi A., Pirnay J.-P. The developing world urgently needs phages to combat pathogenic bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:882. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamshidi A., Kalidari G.A., Hedayati M. Isolation and identification of Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium from the eggs of retail stores in Mashhad, Iran using conventional culture method and multiplex PCR assay. J. Food Safety. 2010;30:558–568. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Public Health England Identification of Enterobacteriaceae. [(accessed on 11 October 2020)];2015 UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations. ID16, Issue No 4. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/423601/ID_16i4.pdf.

- 12.Wattal C., Oberoi J.K., Goel N., Raveendran R., Khanna S. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) for rapid identification of micro-organisms in the routine clinical microbiology laboratory. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017;36:807–812. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2864-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimont P.A., Weill F.X. Antigenic Formulas of the Salmonella Serovars. 9th ed. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella; Paris, France: 2007. [(accessed on 11 October 2020)]. Available online: https://www.pasteur.fr/sites/default/files/veng_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doléans-Jordheim A., Cournoyer B., Bergeron E., Croizé J., Salord H., André J., Mazoyer M.-A., Renaud F.N.R., Freney J. Reliability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa semi-automated rep-PCR genotyping in various epidemiological situations. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009;28:1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0755-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrano I., De Vos D., Santos J.P., Bilocq F., Leitão A., Tavares L., Pirnay J.-P., Oliveira M. Antimicrobial resistance and genomic rep-PCR fingerprints of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from animals on the background of the global population structure. BMC Vet. Res. 2016;13:58. doi: 10.1186/s12917-017-0977-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer A.W. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disc method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966;45:149–158. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/45.4_ts.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CLSI . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 29th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA, USA: 2019. CLSI Supplement. M100S. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams M.H. Bacteriophages. Interscience Publishers; New York, NY, USA: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Twest R., Kropinski A.M. Bacteriophage enrichment from water and soil. In: Clokie M.R., Kropinski A.M., editors. Bacteriophages. Volume 501. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ, USA: 2009. pp. 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merabishvili M., Pirnay J.-P., Verbeken G., Chanishvili N., Tediashvili M., Lashkhi N., Glonti T., Krylov V., Mast J., Van Parys L., et al. Quality-controlled small-scale production of a well-defined bacteriophage cocktail for use in human clinical trials. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J., Russell D. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wattam A.R., Davis J.J., Assaf R., Boisvert S., Brettin T., Bun C., Conrad N., Dietrich E.M., Disz T., Gabbard J.L., et al. Improvements to PATRIC, the all-bacterial Bioinformatics Database and Analysis Resource Center. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D535–D542. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stecher G., Tamura K., Kumar S. Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) for macOS. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020;37:1237–1239. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brettin T., Davis J.J., Disz T., Edwards R.A., Gerdes S., Olsen G.J., Olson R.J., Overbeek R., Parrello B., Pusch G.D., et al. RASTtk: A modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8365. doi: 10.1038/srep08365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan M.J., Petty N.K., Beatson S.A. Easyfig: A genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grubaugh N.D., Gangavarapu K., Quick J., Matteson N.L., De Jesus J.G., Main B.J., Tan A.L., Paul L.M., Brackney D.E., Grewal S., et al. An amplicon-based sequencing framework for accurately measuring intrahost virus diversity using PrimalSeq and iVar. Genome Biol. 2019;20:8. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1618-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magiorakos A.-P., Srinivasan A., Carey R., Carmeli Y., Falagas M., Giske C., Harbarth S., Hindler J., Kahlmeter G., Olsson-Liljequist B., et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makalatia K., Kakabadze E., Bakuradze N., Grdzelishvili N., Natroshvili G., Kusradze I., Goderdzishvili M., Sedrakyan A., Arakelova K., Mkrtchyan M., et al. Activity of bacteriophages to multiply resistant strains of salmonella and their various serotypes. Vet. Biotech. 2018;32:500–508. doi: 10.31073/vet_biotech32(1)-67. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gambino M., Sørensen A.N., Ahern S., Smyrlis G., Gencay Y.E., Hendrix H., Neve H., Noben J.P., Lavigne R., Brøndsted L. Phage S144, A New Polyvalent Phage Infecting Salmonella spp. and Cronobacter sakazakii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:5196. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolen T.N., Xie Y., Hernandez A.C., Everett G.F.K. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium myophage Mushroom. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e00154-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00154-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whichard J.M., Weigt L.A., Borris D.J., Li L., Zhang Q., Kapur V., Pierson F.W., Lingohr E.J., She Y.-M., Kropinski A.M., et al. Complete genomic sequence of bacteriophage felix o1. Viruses. 2010;2:710–730. doi: 10.3390/v2030710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos S.B., Kropinski A.M., Ceyssens P.-J., Ackermann H.-W., Villegas A., Lavigne R., Krylov V.N., Carvalho C., Ferreira E.C., Azeredo J. Genomic and proteomic characterization of the broad-host-range Salmonella phage PVP-SE1: Creation of a new phage genus. J. Virol. 2011;85:11265–11273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01769-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hooton S.P., Timms A.R., Rowsell J., Wilson R., Connerton I.F. Salmonella Typhimurium-specific bacteriophage ΦSH19 and the origins of species specificity in the Vi01-like phage family. Virol. J. 2011;8:498. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luna A.J., Wood T.L., Chamakura K.R., Everett G.F.K. Complete genome of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis myophage Marshall. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00867-13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00867-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim M., Ryu S. Characterization of a T5-like coliphage, SPC35, and differential development of resistance to SPC35 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:2042–2050. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02504-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodridge L.D. Designing phage therapeutics. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010;11:15–27. doi: 10.2174/138920110790725348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmerer M., Molineux I.J., Bull J.J. Synergy as a rationale for phage therapy using phage cocktails. PeerJ. 2014;2:590. doi: 10.7717/peerj.590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merabishvili M., Pirnay J.P., De Vos D. Guidelines to Compose an Ideal Bacteriophage Cocktail. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2018;1693:99–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7395-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.