Abstract

We present an improved type of food gum (salecan) based hydrogels for oral delivery of insulin. Structural hydrogel formation was assessed with Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, thermogravimetric analysis, and X-ray diffraction. We found that the hydrogel modulus, morphology, and swelling properties can be controlled by varying the salecan dose during hydrogel formation. Insulin was introduced into the hydrogel using a swelling–diffusion approach and then further used a drug prototype. In vitro insulin release profiles demonstrated that the release of entrapped insulin was suppressed in acidic conditions but markedly increased at neutral pH. Cell viability and toxicity tests revealed that the salecan hydrogel constructs were biocompatible. Oral administration of insulin-loaded salecan hydrogels in diabetic rats resulted in a sustained decrease of fasting plasma glucose levels over 6 h postadministration. For nondiabetic animals, the relative pharmacological bioavailability of insulin was significantly larger (6.24%, p < 0.05) for insulin-loaded hydrogels compared to free insulin. These results encourage further development of salecan-based hydrogels as vehicles for controlled insulin delivery following oral administration.

Keywords: salecan polysaccharides, hydrogels, drug delivery, insulin, oral

1. INTRODUCTION

With diabetes being one of the major rising threats to global health, new technologies are being developed aimed at controlling blood glucose levels while improving patient compliance.1,2 As compared to conventional subcutaneous injection of insulin, administration via the oral route would be more convenient.1 pH-responsive hydrogels are promising candidates for the development of oral insulin delivery systems because they can retain loaded insulin in deswollen state and release loaded insulin in swollen state upon changes in the pH values of the surrounding environment fluctuates.3,4

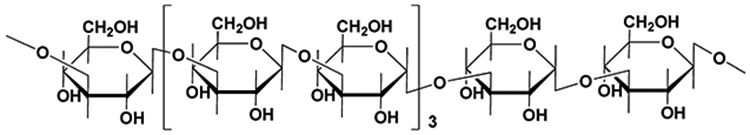

During the last two decades, naturally derived polymers including chitosan, cellulose, starch, pectin, and psyllium have been employed to develop pH-responsive hydrogel carriers for oral insulin delivery because they have intrinsic renewability, biodegradability, and biocompatibility.5-8 More recently, salecan has been studied as an alternative water-soluble bacterial polysaccharide for this purpose.9 Structurally, it is composed of α-1–3-linked d-glucopyranosyl and β-1–3-linked d-glucopyranosyl with stable sequential arrangements (Figure 1).10 Like other bacterial polysaccharides, salecan displays favorable biological characteristics in terms of biocompatibility and antioxidative properties.11-13

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of repeating units of salecan.

Usually, a polysaccharide hydrogel intended for drug delivery applications must be possess a certain mechanical strength to support a folded three-dimensional structure. However, conventional polysaccharide hydrogels present weak elasticity, which seriously restricts the overall scope of polysaccharide gel applications.14 To overcome this limitation, several strategies have been developed to preparing polysaccharide hydrogels with improved elastic properties. This includes producing double-network hydrogels consisting of two interpenetrating polymer networks (IPN), introducing side chains onto the polysaccharide chains to generate grafted hydrogels and incorporating nanoparticles into the hydrogel matrix for fabricating nanocomposite hydrogels.15-17 Among these methods, the IPN technique offers a convenient route to increase the mechanical strength of the polysaccharide. Another advantage of incorporating polysaccharides into the hydrogel using IPN originates from the fact that the polysaccharide chain can retain its own properties (such as biocompatibility and biodegradability) since there is no chemical bonding between polysaccharide and hydrogel matrix.18

Recently, we reported on the fabrication of salecan-based hydrogel devices for in vitro insulin delivery by grafting poly(2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propanesulfonic acid) (PAMPS) onto salecan chains (salecan-g-PAMPS hydrogel).9 The preliminary results on insulin release clearly suggested some limitations comprising its weak mechanical resistance, making it impossible to apply in vivo. Therefore, in this work, we adopted the semi-IPN method to synthesize rigid salecan-constructed hydrogels by employing salecan as the guest network and poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) (PMA) as host network. Acrylamide (AM) and acrylic acid (AA) were selected as the base monomers for their fast copolymerization velocity and stimulus-sensitive attributes, while salecan was chosen as the second network component for its high water affinity and excellent biocompatibility.10,19 We aimed to obtain a hydrogel with a moderate mechanical strength that can meet the clinical demands for oral insulin delivery. Compared to previously developed salecan-g-PAMPS hydrogels,9 the new salecan/poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) hydrogels (salecan/PMA) showed high elasticity even for gels containing high salecan concentrations. The favorable in vitro and in vivo insulin delivery profiles indicate that salecan-based hydrogels have translational potential for controlled insulin delivery after oral administration.

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1. Materials.

Acrylic acid (AA, 99.0%), acrylamide (AM, 99.0%), N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED, 98.0%), ammonium persulfate (APS, 99.0%), N,N′-methylenebis(acrylamide) (BisAA, 99.0%), and insulin (from bovine pancreas) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). An insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia) was purchased from Jiancheng Tech Co. Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Modified Bradford protein assay kit were purchased from Meilun Biology Technology Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China). Hoechst 33342 and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Propidium iodide (PI) was acquired from Life Technologies Corporation (Eugene, OR, USA). Salecan polysaccharide was prepared by the Nanjing University of Science and Technology (NJUST) Center for Molecular Metabolism.

2.2. Fabrication of Salecan/PMA Semi-interpenetrating Polymer Network Hydrogels (Semi-IPNs).

The macroscopic hydrogels were synthesized by polymerizing monomers (AM and AA) using a polymerization initiator (APS) and accelerator (TEMED) in the presence of salecan polysaccharide as described previously. Briefly, a monomer aqueous solution consisting of 0.1 mL of AA (29%, w/v) and 0.9 mL of AM (29%, w/v) was blended with 0.03 mL of BisAA (2%, w/v) and 0.01 mL of TEMED (40%, w/v) to make a stock solution. Different numbers of salecan solution (2%, w/v) were introduced to each stock solution to acquire ultimate salecan/monomer ratios (w/w) of 0.192, 0.144, 0.096, 0.048, and 0, respectively (Table S1, Supporting Information). After the solution was mixed completely and degassed with argon for 30 min, 0.04 mL of APS (10%, w/v) was introduced to initiate polymerization (the final volume of the precursor solution was tuned to 4 mL by deionized water). The reaction was conducted for 40 min (37 °C). The crude hydrogel transferred to beaker and then extracted with deionized water eight times for 4 days so as to remove the unreacted macromonomer, initiating species and other impurities. Finally, these hydrogels were cut into small pieces and lyophilized for further analysis.

2.3. Hydrogel Characterization.

2.3.1. Amount of Salecan in Washing Solutions of Designed Hydrogels.

We employed the phenol-sulfuric acid assay for the quantitative determination of salecan polysaccharide in the washing solutions of crude hydrogels.20 Typically, 500 μL of washing solution was incorporated into a glass tube with 250 μL of phenol solution (6%, v/v), followed by adding 1.25 mL of sulfuric acid (98 wt %). The glass tube was then shaken thoroughly for 10 min to obtain a uniform solution. The amount of salecan polysaccharide was determined using a V-630 UV–vis spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) at 490 nm. All samples were run in triplicate.

2.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR).

The chemical compositions of the developed hydrogels were analyzed adopting a Nicolet IS-10 instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in the region of 400–4000 cm−1. The resolution was 4 cm−1, with 32 scans per sample. Background tests were conducted prior to each sampling experiment and automatically subtracted.

2.3.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD).

The crystallinity of the samples was examined using a DMAX-2200 diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation (0.15418 nm). Parameters were set at 20 mA and 20 kV and a scanning speed of 5° /min within 10–60°.

2.3.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA).

Thermal properties of the samples were assessed using a TGA Q600 instrument (TA Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) under nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 50 mL/min from 50 to 600 °C.

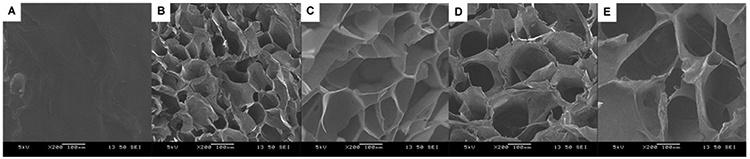

2.3.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

The internal morphology of the PMA and salecan/PMA hydrogels was examined by JSM-6380LV SEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 20 kV. Hydrogels were first swollen to equilibrium and then cut into small disks and dried utilizing liquid nitrogen. Lyophilized specimens were coated with gold to increase conductivity. The average diameter of pores was calculated using ImageJ software.

2.3.6. Rheology.

Dynamic rheological measurements were performed on a MCR 101 rheometer (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) equipped with a 50 mm diameter parallel plate at a gap of 1 mm. Immediately after the formation of salecan/PMA hydrogels, a dynamic strain sweep test was first performed to measure the linear viscoelasticity region of these hydrogels. Then dynamic frequency sweep test was conducted under a frequency ranging from 0.1 to 10 Hz and constant strain of 0.1%.

2.3.7. Swelling and Shrinking Properties.

The swelling and shrinking profiles of the salecan/PMA hydrogels were acquired employing a gravimetric method. Typically, salecan/PMA gel samples were first swollen to equilibrium. Then hydrogel specimens were cut into uniform blocks with size about 2 mm × 4 mm × 5 mm. After lyophilization, these preweighed hydrogels were soaked in three buffer solutions at 37 °C (Na2HPO4/KH2PO4 buffer, pH = 7.4; C8H5KO4 buffer, pH = 4.0; and HCl/NaCl buffer, pH = 1.3; for all these buffers, the ionic strength was adjusted to 0.1 M with NaCl). The hydrogel samples were removed from buffers at set time points and weighed after wiping excess surface water with moistened filter paper. This procedure was continued until a swelling equilibrium had been reached. The water uptake (WU) and equilibrium water uptake (EWU) were defined as

| (1) |

| (2) |

where W0, Wt, and We are the weight of dried gel, swollen gel at time t, and gel in equilibrium state, respectively. The water uptake ability of salecan/PMA hydrogel in NaCl solution with different concentration was measured in the same manner.

For the shrinking assay, the above-mentioned dried gels were submerged in deionized water to achieve water saturation. The swollen gels were then transferred to a 37 °C oven. The changes in gel weight was calculated at various time periods using eq 3:

| (3) |

where W0, Wt, and We represent the weight of lyophilized gel specimens, shrunken gel specimens at time t, and swollen gel specimens at equilibrium, respectively. All measurements were conducted in triplicate and the mean value was recorded.

2.4. Erosion Study.

The dried salecan/PMA gel samples were weighed and soaked in pH 7.4 buffers at 37 °C. At certain time points, the hydrogel samples were washed using distilled water and transferred to a 37 °C vacuum oven. These gels were weighed again and put into the buffers for another interval. This procedure was continued until the results support the erosion of hydrogel matrix. The percentage of weight loss (%) was calculated using eq 4:

| (4) |

where W0 represents the initial weight of dried gel, and Wt represents the weight of the dried gel after being soaked in buffers a certain interval.

2.5. Cell Viability Assay.

The 9L rat glioblastoma cells (9L), HCT116 human colon cancer cells (HCT116), and MC38 colon cancer cells (MC38) were cultured in standard medium at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The culture medium was refreshed every 72 h. The cytotoxicity of the hydrogels for these three cell lines was first evaluated using dual Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide (PI) staining. Cells were seeded into six-well plates at 1 × 104 cells/well and cultured for 24 h. After cell attachment, the three cell lines were treated with the same gel-extracted solution for 72 h. The medium in each well was aspirated and replaced with 2 mL of fresh culture medium containing 40 μg of Hoechst 33342 and 40 μg of PI for 15 min. Dual fluorescence-stained cells were washed with pH 7.4 phosphate buffer thrice and observed using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope (Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). Medium without hydrogel extracts was used as baseline control group.

Next, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was performed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the salecan/PMA hydrogels. In detail, gel specimens were sterilized twice with 70% ethanol twice. The obtained gels were extracted extensively with sterile PBS (pH = 7.4, 10 mM) to remove the adsorbed ethanol. Each sterile gel was placed in a cell culture dish filled with 5 mL of fresh cell culture medium at 37 °C for 3 days. Gels were cautiously removed, and the remaining liquid was collected filtered through a 0.22 μm Millipore filter. Simultaneously, 9L, HCT116, and MC38 cells were separately seeded into a 96-well plate at a cell density of 4000 cells per well. After 24 h of cultivation, the medium in each 96-well was removed completely and replaced with 150 μL of the gel-extracted liquids. Medium without salecan/PMA hydrogel addition was used as baseline control sample. Seventy-two hours later, 15 μL of MTT solution was incorporated into each well, and the cells were incubated for a further 4 h. After complete removal of MTT, the formed formazan salts was dissolved using dimethyl sulfoxide (150 μL). Relative cell viability was determined by contrasting the absorbance of cells treated with different hydrogel extracts at 570 nm against the control sample.

2.6. In Vitro Insulin Loading and Release Properties.

2.6.1. Loading Capacity of Salecan/PMA Hydrogels.

Insulin was introduced into the developed gels using a swelling–diffusion approach. Briefly, 50 mg of each lyophilized hydrogel specimen was placed in 10 mL of pH = 7.4 PBS (10 mM) containing 200 μg/mL insulin and allowed to swell at 37 °C.

After swelling equilibrium was reached, the hydrogels were carefully separated from the insulin media and washed with pH = 7.4 PBS (10 mM) five times to get rid of insulin absorbed at the gel surface. The remaining insulin and washing solutions were collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm Millipore filter. The insulin content left in the loading medium was quantified using the Bradford assay kit by an UV–vis spectrophotometer at 595 nm. The insulin loading efficiency (ILE) was calculated by the following formula:

| (5) |

where W0 (mmol) is the initial insulin used for drug loading, C1 (mmol/mL) is the remaining content of insulin in the filtrate solution after introduction of hydrogel sample, and V1 (mL) is the volume of the filtrate solution.

2.6.2. In Vitro Insulin Release Assay.

To assess the insulin release property, the insulin-loaded hydrogels were immersed in 25 mL of buffer solution (pH = 7.4 or 1.3) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking speed of 110 rpm. At predetermined time intervals, 1.5 mL of buffer was withdrawn and 1.5 mL of fresh buffer was added to keep the volume constant.

Aliquots of the collected buffers were centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 10 min and determined by the Bradford assay kit using an UV–vis spectrophotometer at 595 nm. The cumulative percentage of released insulin was determined by the following formula:

| (6) |

where m means the content of insulin in gel specimen before release test, V0 represents the volume of media used for release test, and Cn denotes the insulin amount in the nth hydrogel specimen.

2.7. In Vivo Insulin Delivery.

All animal procedures were approved and carried out according to our institutional guidelines for the care and utilization of laboratory animals. Male Wistar rats (180–200 g) were housed in metabolic cages at 21 °C and relative humidity level of 55% with 12 h of alternate light and dark cycles. All rats were allowed free access to water and food ad libitum prior to the experiment. For the diabetes induction, male Wistar rats were injected with streptozotocin (dissolved in 8 mM pH = 4.5 citrate buffer immediately prior to injection) at a dose of 48 mg/kg. Rats were considered to be diabetic when the fasted blood glucose levels (BGLs), which were determined using a glucometer, were higher than 300 mg/dL, 14 days after streptozotocin treatment.21 Twelve-hour fasted male Wistar diabetic rats were chosen and randomly divided into four groups (n = 6 per group). Group I rats were oral administration with saline as control. Group II rats were subcutaneous (s.c.) injected with standard insulin solution (2.5 IU/kg). Group III and Group IV rats were fed orally with insulin-free SH4 hydrogel (25 or 50 IU/kg) and insulin-loaded SH4 hydrogel (25 or 50 IU/kg), respectively. A drop of blood sample was taken from the tail vein before the administration and at predetermined time periods after the administration. The blood glucose level was measured utilizing a glucose meter. The relative pharmacological availability (rPA%) was analyzed by eq 7:22

| (7) |

where doses.c. and doseoral represent the insulin dose given by s.c. injection and oral administration, respectively. [AAC]s.c. and [AAC]oral indicate the region above the profile relative to s.c. injection and oral administration of insulin, respectively. All assays were conducted in triplicate.

2.8. In Vivo Bioavailability of Insulin.

The bioavailability of insulin was assessed in normal male Wistar rats. Briefly, 12 h fasted male Wistar rats were chosen and randomly divided into two groups (n = 6 per group). Group I received standard insulin (5 IU/kg) through s.c. injection as control, and Group II was fed insulin-loaded SH4 hydrogel (50 IU/kg) by oral route. Blood sample was taken from the jugular vein prior and after insulin administration. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 12 000 rpm for 15 min and stored at 4 °C until further analysis. Plasma insulin level was quantified utilizing the above-mentioned ELISA kit, subtracted with the basal insulin level at each corresponding time point.7 The relative bioavailability (rB%) was defined as22

| (8) |

where AUC represents the total area under the plasma insulin concentration curve. Doseoral and doses.c. indicate insulin doses by oral administration and s.c. injection, respectively.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Synthesis of Salecan/PMA Hydrogels.

In this study, improved salecan/PMA hydrogel formulations were developed using salecan, AM, AA, and the cross-linker BisAA for controlled release of insulin. An overview of the process for the development of salecan/PMA gel is displayed in Scheme 1. Typically, the monomers AM and AA were cross-linked with BisAA through radical polymerization reaction in the presence of salecan polysaccharides. Herein, APS was applied to initiate polymerization, while TEMED served as an activator to accelerate the generation of radicals. Unlike our previous work on salecan-g-PAMPS hydrogels,9 copolymerization of monomer (AM and AA) in the presence of salecan was conducted at 25 °C with a catalyst, instead of a higher temperature of 70 °C without a catalyst. This fabrication process allows the introduction of salecan chains into the PMA matrix, which can physically entangle and uniformly diffuse within the cross-linked PMA gel structure through hydrogen-bonding, ensuring maintenance of integrity of the salecan backbone after semi-interpenetrating polymer network formation.

Scheme 1.

Fabrication of Semi-IPN Hydrogels Employing PMA as Matrix and Salecan Polysaccharide as Entrapped Chain

3.2. Properties of Salecan/PMA Semi-IPN Hydrogels.

3.2.1. Stability of Salecan Polysaccharide in Semi-IPN Hydrogel.

Salecan content in the soaking media of salecan/PMA hydrogel was monitored adopting phenol-sulfuric acid assay (Table 1). A low salecan content was measured in the soaking solution, indicating that the incorporated salecan was stable within the PMA hydrogel matrix.

Table 1.

Content of Salecan in Soaking Medium and Hydrogel

| composition | amount of salecan in hydrogel (mg) |

amount of salecan in soaking medium (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| SH1 | 13.88 | 0.12 |

| SH2 | 27.67 | 0.33 |

| SH3 | 41.59 | 0.41 |

| SH4 | 55.48 | 0.52 |

3.2.2. FT-IR.

FT-IR was employed to acquire structural information on the resulting hydrogels. As shown in Figure 2A, salecan possessed an intensive peak located at about 3298 cm−1 assigned to the O─H stretching vibration.23 As expected, the characteristic absorption peaks of salecan were present between 1038 and 809 cm−1.9 More exactly, the band centered at 1038 cm−1 likely corresponds to C─OH stretching. The band at 891 cm−1 suggests that d-glucopyranose is connected by a β-configuration, whereas the weak band at 809 cm−1 was due to the existence of α-glucopyranose in polysaccharide chain.24

Figure 2.

(A) FTIR, (B) XRD, (C) TGA, and (D) DTG curves of salecan, PMA, and salecan/PMA.

Considering the spectrum of the pure PMA hydrogel, the acrylamide component in the PMA gel was manifested by the existence of a sharp band at approximately 1635 cm−1 due to the amide I stretching vibrations of the acrylamide.25,26 The acrylic acid segment in the PMA gel was evidenced by a prominent absorption band at 1253 cm−1 ascribed to the stretching vibration of C─O groups of acrylic acid.19 It is worth mentioning that another characteristic absorption bands of acrylic acid at around 1700 cm−1 (associating with C=O stretching vibration) disappeared in the copolymeric hydrogel. This typical peak might be overlapped by the amide I band of acrylamide at 1635 cm−1. Similar phenomenon was observed by Dai et al. in the prepared poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) hydrogel.28 In addition, the presence of the cross-linker unit (BisAA) could be verified by the presence of an intense band around 1161 cm−1 related to the C─N stretching vibrations of BisAA.27 As for the FT-IR spectrum of salecan/PMA hydrogel, the characteristic bands for both PMA hydrogel and salecan polysaccharide were observed, demonstrating a successful introduction of salecan chains into the cross-linked PMA network.

3.2.3. XRD Analysis.

To further investigate the cross-linking structure of the prepared hydrogels, XRD studies of the salecan, PMA, and salecan/PMA mixture were undertaken (Figure 2B). Salecan has a strong diffraction peak positioned at around 2θ = 21°, which can be associated with the crystal regions that exist in the polysaccharide chains, attributing to the hydrogen bonding interactions among functional moieties of salecan chains, such as hydroxyl groups.27,29 However, the salecan-containing semi-IPN hydrogels do not present this peak, which indicate that those established crystalline regions of salecan polysaccharide were destroyed after polymerization, revealing the dispersion of salecan chains within PMA matrices in an amorphous manner and further evidencing the formation of interpenetrating polymer networks.30

3.2.4. TGA.

TGA was applied to obtain thermal stability information on the synthesized hydrogels (Figure 2C). For salecan, the mass loss around 11.6 wt % below 140 °C was due to the removal of water absorbed from air. A two-step decomposition was noticed in the temperature range of 140–360 °C and 360–600 °C with 44.8% and 25.2% mass loss, respectively, which can be ascribed to thermal scission of the glycosidic units and cleavage of the C─O bonds.27,29 For the PMA hydrogel thermogram, three steps of weight loss could be observed. In the first step, a small reduction in weight of 11.4% before 148 °C can be assigned to the escape of moisture vapor. The second step from 148 to 300 °C exhibited a mass loss of 14.4%, which can be attributed to the breakage of side chain groups including ─NH2 and ─COOH. Beyond 300 °C, PMA lost its major weight (53.2%), primarily caused by the pyrolysis of the hydrogel backbone.31 As expected, thermal degradation of salecan/PMA semi-IPN gel possessed a similar thermal curve to that of PMA. The initial slight mass loss of 7.8% (50–145 °C) was caused by the vaporization of absorbed and bonded water. The second step between 145 and 271 °C showed a 11.9% weight loss. The third step from 271 to 600 °C showed a 57.3% decomposition. These latter two steps indicate a significant fragmentation of the PMA hydrogel network and dehydration of the salecan backbone.19

Meanwhile, it can be deducted from the DTG data (Figure 2D) that the introduction of salecan brings distinct variations in the thermal behavior of the overall gel: after salecan polysaccharide was incorporated into the PMA matrix, the maximum weight loss rate occurred at a higher temperature (375 °C) than that for salecan itself (278 °C), which can be attributed to the considerable intermolecular interaction of the pure PMA network with the salecan chains, leading to an improved thermal stability of the semi-IPN.

3.2.5. Hydrogel Morphology.

The internal structure of freeze-dried PMA and salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels was investigated by SEM (Figure 3). The PMA hydrogel sample presented a smooth and compact morphology, whereas semi-IPN hydrogels exhibited a honeycomb-like structure consisting of orderly arranged macropores after the introduction of salecan. Generally, the presence of porous structure could facilitate the penetration of water into polymeric network, consequently benefiting for the absorbency of water/drug solution.28,32 Moreover, from Figure 3, we also found that semi-IPN gels with a higher salecan polysaccharide had bigger macropores compared to gels with lower salecan polysaccharide. Among the four semi-IPN hydrogel specimens, SH4 had the largest pore size being 107.4 ± 20.5 μm, while the diameter of the pored declined to approximately 90.3 ± 16.9, 68.9 ± 14.3, and 31.4 ± 4.1 μm for SH3, SH2, and SH1, respectively. Hydrogels that had more salecan exhibited a higher water content (see further below), which stimulated the generation of a larger ice crystal when immersing the hydrogel into liquid nitrogen. These larger ice crystals were sublimated and eventually, bigger pores were produced.33

Figure 3.

SEM pictures of the PMA and salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels: (A) PMA, (B) SH1, (C) SH2, (D) SH3, and (E) SH4.

Taken together, the morphology of the developed salecan/PMA hydrogels could be adjusted by tuning the feeding ratios of salecan in initial pregel solution. Changes in morphology of the hydrogels may involve differences in their physical–chemical properties. The swelling/shrinking, mechanical, and drug loading/release behaviors of salecan/PMA hydrogel were also tunable by simply altering the salecan content in the semi-IPN structure.

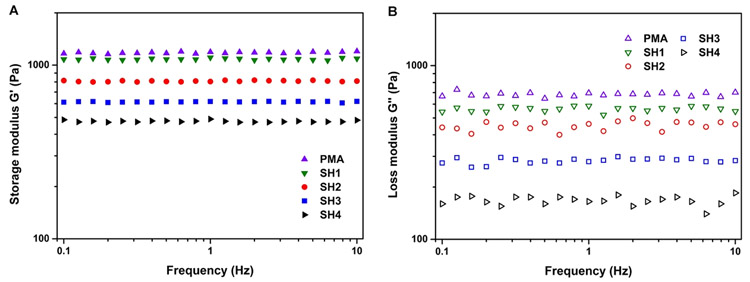

3.2.6. Mechanical Properties.

It is crucial that the designed hydrogel drug carriers retain their structural integrity during the drug storage and release process.34 For that purpose, mechanical behaviors of pure PMA and salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels were first investigated. Rheological tests of the salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels were undertaken at room temperature. The storage modulus (G′, disclosing the quantity of energy stored in materials) and loss modulus (G″, representing the material’s ability to dissipate energy) were determined as a function of frequency.35 As shown in Figure 4, the G′ was higher than G″ over the entire frequency range (0.1–10 Hz) for each gel sample, and their profiles did not across each other, suggesting the dominant elastic character. Similar phenomenon are obtained for other hydrogel samples.35-37 Besides, from Figure 4A, we also noticed that the stiffness of the salecan/PMA hydrogels could be varied by changing the salecan concentration in pregel solution. Specifically, the storage modulus declined gradually with increased salecan content, from 1060 Pa (PMA) to 476 Pa (SH4). This can be explained by the addition of salecan that enhances the affinity of hydrogel for water molecules, resulting in easier diffusion of water into the polymeric network, and finally, reducing stiffness of the gel. In addition, the storage modulus of salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogel was much higher than previous results for salecan-g-PAMPS gel (Table S2 and Figure S1, Supporting Information), favoring for drug storage and release.9

Figure 4.

(A) Storage modulus and (B) loss modulus of gels with different salecan/monomer ratios (PMA, SH1, SH2, SH3, SH4).

3.2.7. Swelling Properties.

The ability of semi-IPN gels to take up and retain water is of critical importance for their potential biomedical applications. The swelling and shrinking properties in response to various salt concentrations and pH values were therefore further explored.

3.2.7.1. Effect of Salt Concentration on Hydrogel Water Adsorption.

To assess the swelling properties of salecan/PMA hydrogels, we determined the equilibrium water uptake (EWU) as a function of NaCl concentration (Figure 5A). EWU values decreased with increasing NaCl concentrations, for example, for SH3 the values were 35.9, 20.6, and 10.2 for 0.3, 0.6, and 0.9% w/w NaCl, respectively. This observation can be explained by two factors. First, the Na+ counterion penetrates into the polymeric network and then binds to the anionic ─COO− groups of the PAA chains. This results in a release of water molecules by shielding of the electrostatic repulsion among carboxyl groups in the PAA skeleton.28,38 Second, the osmotic pressure between the inside and outside of hydrogels is increased with higher concentrations of salt solutions. Under these conditions, interior water molecules diffuse out of the hydrogel, causing acceleration evaporation and reduction of water adsorption.39,40

Figure 5.

Water uptake behavior of salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels. Shown are EWU values for different (A) salt concentrations and (B) pH values, (C) swelling kinetics in 10 mM PBS pH = 7.4, and (D) water retention kinetics.

3.2.7.2. Effect of Solution pH on Hydrogel Swelling Property.

To examine the effect of solution pH on water uptake, the EWU was determined for salecan/PMA gels in three different buffers (pH = 7.4, 4.0, and 1.3). All gels exhibited a similar trend of swelling, with the EWU decreasing at lower values (Figure 5B). For example, the EWU of SH4 was 25.3 for pH = 1.3, 40.1 for pH = 4.0, and 55.7 for pH = 7.4. This observation can be explained by the ionization and protonation equilibrium of the carboxyl groups (pKa = 4.3)41 present in the salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogel. In acidic environments (pH = 1.3 and 4.0), the carboxyl groups of salecan/PMA exist in protonated forms (─COOH) and thus the expansion of the gel network was remarkably impaired ascribing to the strong electrostatic attraction among ─COOH groups.19 As the external pH of buffer was tuned to 7.4 (above the pKa value of the PAA unit), the electrostatic attraction between the ─COOH groups was decreased probably attributed to the conversion of ─COOH to ─COO– groups, facilitating the diffusion of water molecules into network structure, leading to quick swelling.38,40 Since the salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels are responsive to changes in pH values, they have potential for controlled drug delivery.

3.2.7.3. Swelling Kinetics.

The degree of water uptake in hydrogels was calculated at pH = 7.4 using their gravimetric ratios. To this end, the weight of freeze-dried and water-swollen gel was measured over time (Figure 5C). All salecan/PMA gels demonstrated a similar swelling profile during the initial 4 h, reaching saturation after 12 h of immersion. As expected, gels containing more salecan adsorbed more water, with values of 22.1, 26.6, 35.2, 42.1 55.7 for PMA, SH1, SH2, SH3, and SH4, respectively. The increased water affinity with higher salecan content is likely related to the presence of multiple ─OH moieties on the backbone of salecan polysaccharide, promoting penetration of water molecules into the gel framework having as result a higher hydration.27 Similar results have been observed for other polysaccharide-based IPN hydrogels.42-44

3.2.7.4. Shrinking Properties.

Figure 5D shows the shrinking profiles of salecan/PMA hydrogels at 37 °C. Hydrogels with higher salecan content expelled more water and dehydrated at a faster rate from the hydrogel network. PMA was found to release >85.5% of its absorbed water after 600 min, while SH1, SH2, SH3, and SH4 lost 90.0%, 95.6%, 97.3%, and 98.2% of their water at this time point, respectively. Generally speaking, gel composed of more salecan polysaccharide had a stronger affinity for water molecules, which can act as water-releasing channels when collapse occurred, thus benefiting for the removal of water.29,45

3.2.7.5. Erosion Assay.

Table S3 (Supporting Information) shows the results of erosion test of salecan/PMA hydrogel samples at pH 7.4 buffers. As presented in Table S3, gels containing more salecan had high level of erosion, with values of 5.33 ± 1.55%, 6.58 ± 1.78%, 7.35 ± 2.01%, 8.17 ± 2.12%, and 9.67 ± 1.88% for PMA, SH1, SH2, SH3, and SH4 after 12 h in buffers at 37 °C, respectively. This phenomenon can be explained by the incorporation of salecan that decreases the stiffness of hydrogel matrix and enhances the susceptibility of polymer chains, thereby benefiting the erosion.46

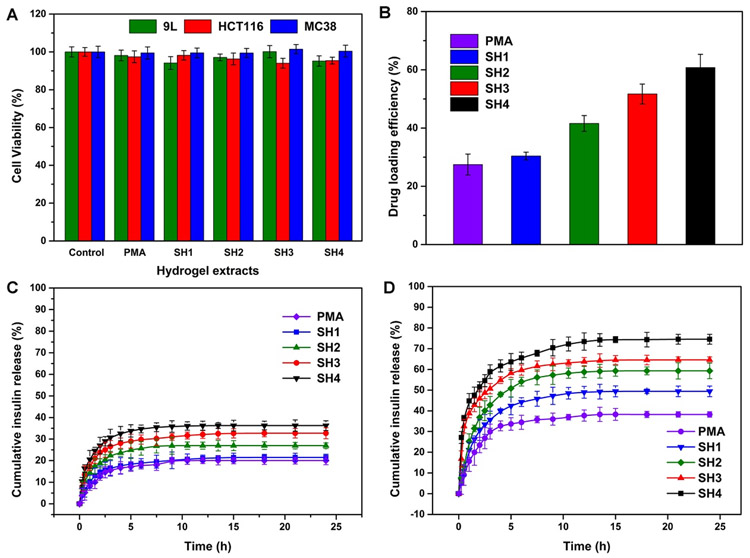

3.3. Cytotoxicity of Salecan/PMA Hydrogels.

Cytotoxicity is an indispensable consideration for a drug delivery carrier design.47 To serve as safe carrier for drug delivery, the carrier itself needs to possess a proper biocompatibility.48 In vitro cytotoxicity assay was performed using a cell staining assay (Figure 6). Hoechst 33342 dye labels nuclei of all cells present, while PI only stains nuclei of dead cells.49 As shown in Figure 6, few cells incubated with salecan/PMA hydrogels exhibited uptake of PI with no differences compared to the negative control. These findings were further corroborated by an MTT assay according to the ISO 10993–5 protocol as reference for biomaterial testing50 (Figure 7A). After 72 h of cultivation with different extracts of salecan/PMA hydrogels, the cell viability of treated 9L, HCT116, and MC38 cells was similar to untreated controls (>90%). MTT and cell staining assays suggested that the designed hydrogel was cell compatible, implying that the salecan/PMA hydrogels were suitable candidates for in vivo applications.

Figure 6.

Fluorescence images of 9L, HCT116, and MC38 incubated with the various hydrogel extracts for 72 h (scale bar = 50 μm). Cells were stained with PI (red) and Hoechst 33342 (blue).

Figure 7.

(A) Cell viability of 9L, HCT116, and MC38 cells after treatment with different hydrogel extracts. (B) Insulin-loading efficiency of salecan/PMA and PMA hydrogels. In vitro insulin release curves for simulated gastric fluid (C, pH = 1.3) and intestinal fluid (D, pH = 7.4).

3.4. In Vitro and in Vivo Insulin Delivery.

3.4.1. In Vitro Insulin Delivery.

We employed insulin, a widely used therapeutic agent for treatment of diabetes, as a model drug to assess the release characteristics of the PMA and salecan/PMA hydrogels. Insulin was incorporated into the PMA and salecan/PMA polymeric network by swelling-diffusion strategy.7 The gel-loaded insulin content was acquired by subtracting the remaining insulin amount in the incubation solution from the initial added amount used for loading.47 It can be observed from Figure 7B that the insulin loading efficiency (ILE) of PMA was 27.5%. Moreover, an increase in salecan content from 0.7 to 2.8 mL enhanced the ILE from 30.3% to 60.8% as a result of a larger WU of the semi-IPN architecture.51 On the one hand, the increase in the number of salecan molecules contributes to increased water uptake by the hydrogel, promoting the penetration of external insulin into the interior of the hydrogel. On the other hand, the semi-IPN architecture helps preventing the collapse of the insulin-loaded hydrogel during the desiccation process.51

To determine the in vitro release curves of insulin from PMA and salecan/PMA hydrogel specimens, experiments were conducted in simulated intestinal fluid (pH = 7.4) and gastric fluid (pH = 1.3). The amount of released insulin was pH-dependent (Figure 7C,D). At 24 h, the cumulative insulin release at pH = 1.3 was 19.7%, 21.5%, 26.9%, 32.7%, and 36.2% for PMA, SH1, SH2, SH3, and SH4, respectively, while at pH = 7.4 these values were 32.1%, 49.4%, 59.3%, 65.6%, and 74.5%. The higher release at pH = 7.4 can be expected, as this is above the pKa value of PAA (4.3)41 and the isoelectric point of insulin (5.4).52 Here, the stronger electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged insulin and the negatively charged carboxyl groups of the PAA segment in the PMA hydrogel facilitates the release of insulin. At the low pH value (pH = 1.3), the hydrogen bonding interactions between the protonated carboxylic groups of the PAA might preserve the hydrogel network in a compact collapsed state, preventing the release of insulin.3

In addition to the effect of pH on drug release, we also noted that the total salecan content in the gel significantly (p < 0.05) affects the rate of insulin release, with SH4 > SH3 > SH2 > SH1 > PMA, in agreement with the WU discussed above. A recent report confirmed that the drug release properties of the hydrogel are increase with the water uptake.53 Insulin is susceptible to biodegradation and denaturation.1,54 The major hurdles preventing the success of oral delivery of insulin are overcoming the enzymatic degradation in the stomach.55,56 Our salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels have desirable insulin release features when orally administered, as it can initiate and maintain a low release in the acidic stomach at pH = 1.3, while an accelerated release is triggered in the intestinal environment (pH = 7.4).

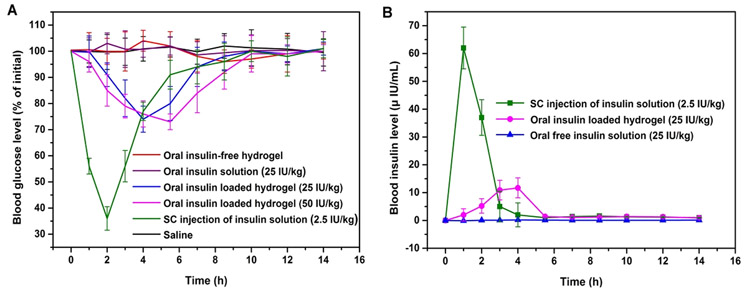

3.4.2. In Vivo Insulin Delivery.

Finally, we assessed the pharmacokinetics and therapeutic effects of orally administered insulin-loaded salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels in STZ-induced diabetic rats. SH4 hydrogel was selected for its optimal pH-dependent release behavior, where the hydrogel protects the insulin from the harsh stomach conditions and only effectively releases insulin in the small intestine environment. Figure 8A shows the time course of blood glucose level following oral administration of insulin-free and insulin-loaded hydrogels, as compared to s.c. injection of saline or pure insulin. No therapeutic effect (absence of hypoglycemia) could be noticed after oral administration of free insulin and s.c. injection of saline. For the animals given a s.c. injection of free insulin, blood glucose levels quickly dropped achieving a minimum of 36.0% at 2 h after injection after which the blood glucose returned to previous levels. This outcome is in agreement with the short half-life of insulin in blood.7 Animals treated with different dosages of insulin-loaded hydrogel exhibited dosage-dependent blood glucose changes. Two hours after administration, blood glucose gradually declined to 82.1% and 78.7% after administration of 25 and 50 IU/kg insulin-loaded SH4 gel, respectively. Unlike the rats injected with insulin s.c., hypoglycemia persisted for longer time periods, in agreement with the slower insulin release observed in vitro, with a maximum effect at 4–6 h after administration. The rPA (%) of insulin for orally administering insulin-loaded hydrogel was calculated to be 5.02%, much larger than that of orally administering free insulin (0.48%). It is noteworthy that the rPA (%) of the salecan/PMA semi-IPN hydrogels (5.02%) is comparable to that of recently reported hydrogel-based vehicles regarding the in vivo sustained release of insulin such as carboxymethyl cellulose/poly(acrylic acid) (6.35%)7 and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-β-methyl acrylic acid) hydrogels (4.77%).3

Figure 8.

Blood glucose levels of STZ-induced diabetic rats after orally administering insulin-loaded hydrogel (25 or 50 IU/kg), free insulin (25 IU/kg), insulin-free hydrogel, s.c. injection of free insulin (2.5 IU/kg), or saline via gavage (A, n = 6). Blood insulin levels of STZ-induced diabetic rats after oral administration of insulin-loaded hydrogel (25 IU/kg), free insulin (25 IU/kg), or s.c. insulin injection (2.5 IU/kg) (B, n = 6).

To further measure the bioavailability parameters of orally administered insulin-loaded hydrogels, the intestinal uptake of insulin was assessed by measuring plasma insulin levels in nondiabetic rats (Figure 8B). The s.c. injection of insulin triggered a rapid increase in plasma insulin peaking at 63.4 mIU per mL, followed by a gradual reduction after 1 h. In contrast, animals receiving insulin-loaded hydrogels showed a more gradual increase in plasma insulin, reaching a maximum of 11.7 mIU per mL 4 h postadministration. A similar time course of insulin delivery from other types of hydrogels has been observed by others.3,54 With the pharmacological bioavailability of s.c. injection of free insulin set as 100%, the pharmacological bioavailability of orally treated sal/PMA semi-IPN hydrogel-loaded insulin was calculated to be 6.24%.

4. CONCLUSIONS

A series of smart salecan-incorporated semi-IPN hydrogels composed of a soft segment of salecan and a high strength network of poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) were created using a free radical polymerization approach. These hydrogels displayed excellent stability, rapid response rate, high elasticity, and good biocompatibility. In vitro insulin release assay demonstrated that the entrapped insulin is protected within the hydrogel matrix under acidic conditions, with a selective release at neutral pH values. The release of insulin can be properly controlled by simply varying the salecan content in the hydrogel composition. Cell viability assays showed that salecan/PMA hydrogels were nontoxic. Orally administered insulin-loaded salecan/PMA hydrogels to diabetic rats resulted in a successive decrease of blood glucose levels and exhibited a greater than 10-fold rise in pharmacological availability compared to free insulin solution given orally. The present findings demonstrate that salecan-based hydrogels loaded with insulin have potential for controlled delivery of insulin following oral administration.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51573078), the China Scholarship Council (Scholarship 201606840064), and the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK106972).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02879.

Composition ratios used for synthesis of salecan/PMA semi-IPNs and salecan-g-PAMPS; storage modulus of salecan/PMA and salecan-g-PAMPS hydrogels; erosion test in PBS (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Xie J; Li A; Li J Advances in pH-Sensitive polymers for smart insulin delivery. Macromol. Rapid Commun 2017, 38, 1700413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ma R; Shi L Phenylboronic acid-based glucose-responsive polymeric nanoparticles: synthesis and applications in drug delivery. Polym. Chem 2014, 5 (5), 1503–1518. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Gao XY; Cao Y; Song XF; Zhang Z; Xiao CS; He CL; Chen XS pH- and thermo-responsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-acrylic acid derivative) copolymers and hydrogels with LCST dependent on pH and alkyl side groups. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1 (41), 5578–5587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ramkissoon-Ganorkar C; Liu F; Baudyš M; Kim SW Modulating insulin-release profile from pH/thermosensitive polymeric beads through polymer molecular weight. J. Controlled Release 1999, 59 (3), 287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Mukhopadhyay P; Sarkar K; Bhattacharya S; Bhattacharyya A; Mishra R; Kundu PP pH sensitive N-succinyl chitosan grafted polyacrylamide hydrogel for oral insulin delivery. Carbohydr. Polym 2014, 112, 627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Singh B; Chauhan N Modification of psyllium polysaccharides for use in oral insulin delivery. Food Hydrocolloids 2009, 23 (3), 928–935. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gao X; Cao Y; Song X; Zhang Z; Zhuang X; He C; Chen X Biodegradable, pH-responsive carboxymethyl cellulose/poly(acrylic acid) hydrogels for oral insulin delivery. Macromol. Biosci 2014, 14 (4), 565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sonia TA; Sharma CP An overview of natural polymers for oral insulin delivery. Drug Discovery Today 2012, 17 (13–14), 784–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Qi X; Wei W; Li J; Zuo G; Pan X; Su T; Zhang J; Dong W Salecan-based pH-sensitive hydrogels for insulin delivery. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2017, 14 (2), 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sun Q; Xu X; Yang X; Weng D; Wang J; Zhang J Salecan protected against concanavalin A-induced acute liver injury by modulating T cell immune responses and NMR-based metabolic profiles. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2017, 317, 63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wu M; Shi Z; Huang H; Qu J; Dai X; Tian X; Wei W; Li G; Ma T Network structure and functional properties of transparent hydrogel sanxan produced by Sphingomonas sanxanigenens NX02. Carbohydr. Polym 2017, 176, 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Roy A; Comesse S; Grisel M; Hucher N; Souguir Z; Renou F Hydrophobically modified xanthan: an amphiphilic but not associative polymer. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15 (4), 1160–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Varshosaz J Dextran conjugates in drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2012, 9 (5), 509–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chaturvedi K; Ganguly K; Nadagouda MN; Aminabhavi TM Polymeric hydrogels for oral insulin delivery. J. Controlled Release 2013, 165 (2), 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Dragan ES; Apopei Loghin DF; Cocarta AI Efficient sorption of Cu2+ by composite chelating sorbents based on potato starch-graft-polyamidoxime embedded in chitosan beads. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6 (19), 16577–16592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Maleki L; Edlund U; Albertsson A-C Green semi-IPN hydrogels by direct utilization of crude wood hydrolysates. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng 2016, 4 (8), 4370–4377. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zhang K; Feng Q; Xu J; Xu X; Tian F; Yeung KWK; Bian L Self-assembled injectable nanocomposite hydrogels stabilized by bisphosphonate-magnesium (Mg2+) coordination regulates the differentiation of encapsulated stem cells via dual crosslinking. Adv. Funct. Mater 2017, 27 (34), 1701642. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Mandal BB; Kapoor S; Kundu SC Silk fibroin/polyacrylamide semi-interpenetrating network hydrogels for controlled drug release. Biomaterials 2009, 30 (14), 2826–2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Singha NR; Mahapatra M; Karmakar M; Dutta A; Mondal H; Chattopadhyay PK Synthesis of guar gum-g-(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide-co-3-acrylamido propanoic acid) IPN via in situ attachment of acrylamido propanoic acid for analyzing superadsorption mechanism of Pb(ii)/Cd(ii)/Cu(ii)/MB/MV. Polym. Chem 2017, 8, 6750–6777. [Google Scholar]

- (20).DuBois M; Gilles KA; Hamilton JK; Rebers PA; Smith F Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem 1956, 28 (3), 350–356. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chaturvedi K; Ganguly K; Kulkarni AR; Rudzinski WE; Krauss L; Nadagouda MN; Aminabhavi TM Oral insulin delivery using deoxycholic acid conjugated PEGylated polyhydroxybutyrate co-polymeric nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2015, 10 (10), 1569–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Shan W; Zhu X; Liu M; Li L; Zhong J; Sun W; Zhang Z; Huang Y Overcoming the diffusion barrier of mucus and absorption barrier of epithelium by self-assembled nanoparticles for oral delivery of insulin. ACS Nano 2015, 9 (3), 2345–2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Su T; Qi X; Zuo G; Pan X; Zhang J; Han Z; Dong W Polysaccharide metallohydrogel obtained from Salecan and trivalent chromium: Synthesis and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym 2018, 181, 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Qi X; Hu X; Wei W; Yu H; Li J; Zhang J; Dong W Investigation of Salecan/poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels prepared by freeze/thaw method. Carbohydr. Polym 2015, 118, 60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Li S; Zhang H; Feng J; Xu R; Liu X Facile preparation of poly(acrylic acid–acrylamide) hydrogels by frontal polymerization and their use in removal of cationic dyes from aqueous solution. Desalination 2011, 280 (1–3), 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kong W; Huang D; Xu G; Ren J; Liu C; Zhao L; Sun R Graphene oxide/polyacrylamide/aluminum ion cross-linked carboxymethyl hemicellulose nanocomposite hydrogels with very tough and elastic properties. Chem. - Asian J 2016, 11 (11), 1697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Qi X; Wei W; Su T; Zhang J; Dong W Fabrication of a new polysaccharide-based adsorbent for water purification. Carbohydr. Polym 2018, 195, 368–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Dai H; Huang H Enhanced Swelling and Responsive Properties of Pineapple Peel Carboxymethyl Cellulose-g-poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) Superabsorbent Hydrogel by the Introduction of Carclazyte. J. Agric. Food Chem 2017, 65 (3), 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Qi X; Wei W; Li J; Su T; Pan X; Zuo G; Zhang J; Dong W Design of Salecan-containing semi-IPN hydrogel for amoxicillin delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2017, 75, 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Qi X; Wei W; Li J; Liu Y; Hu X; Zhang J; Bi L; Dong W Fabrication and characterization of a novel anticancer drug delivery system: salecan/poly(methacrylic acid) semi-interpenetrating polymer network hydrogel. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2015, 1 (12), 1287–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Liu P; Jiang L; Zhu L; Wang A Novel covalently cross-linked attapulgite/poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) hybrid hydrogels by inverse suspension polymerization: synthesis optimization and evaluation as adsorbents for toxic heavy metals. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2014, 53 (11), 4277–4285. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Garcia-Astrain C; Chen C; Buron M; Palomares T; Eceiza A; Fruk L; Corcuera MA; Gabilondo N Biocompatible hydrogel nanocomposite with covalently embedded silver nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16 (4), 1301–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Dragan ES; Lazar MM; Dinu MV; Doroftei F Macroporous composite IPN hydrogels based on poly(acrylamide) and chitosan with tuned swelling and sorption of cationic dyes. Chem. Eng. J 2012, 204–206, 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ma C; Shi Y; Pena DA; Peng L; Yu G Thermally responsive hydrogel blends: a general drug carrier model for controlled drug release. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54 (25), 7376–7380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ramin MA; Sindhu KR; Appavoo A; Oumzil K; Grinstaff MW; Chassande O; Barthelemy P Cation tuning of supramolecular gel properties: a new paradigm for sustained drug delivery. Adv. Mater 2017, 29 (13), 1605227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Clarke DE; Pashuck ET; Bertazzo S; Weaver JVM; Stevens MM Self-healing, self-assembled beta-sheet peptide-poly(gamma-glutamic acid) hybrid hydrogels. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (21), 7250–7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Peng N; Hu D; Zeng J; Li Y; Liang L; Chang C Superabsorbent cellulose–clay nanocomposite hydrogels for highly efficient removal of dye in water. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng 2016, 4 (12), 7217–7224. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Zhang M; Wang R; Shi Z; Huang X; Zhao W; Zhao C Multi-responsive, tough and reversible hydrogels with tunable swelling property. J. Hazard. Mater 2017, 322, 499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Yu C; Yuan P; Erickson EM; Daly CM; Rogers JA; Nuzzo RG Oxygen reduction reaction induced pH-responsive chemo-mechanical hydrogel actuators. Soft Matter 2015, 11 (40), 7953–7959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Chang C; He M; Zhou J; Zhang L Swelling Behaviors of pH- and salt-responsive cellulose-based hydrogels. Macromolecules 2011, 44 (6), 1642–1648. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Zhang S; Shu X; Zhou Y; Huang L; Hua D Highly efficient removal of uranium (VI) from aqueous solutions using poly(acrylic acid)-functionalized microspheres. Chem. Eng. J 2014, 253, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Pescosolido L; Schuurman W; Malda J; Matricardi P; Alhaique F; Coviello T; van Weeren PR; Dhert WJA; Hennink WE; Vermonden T Hyaluronic acid and dextran-based semi-IPN hydrogels as biomaterials for bioprinting. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12 (5), 1831–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Dragan ES; Apopei DF Multiresponsive macroporous semi-IPN composite hydrogels based on native or anionically modified potato starch. Carbohydr. Polym 2013, 92 (1), 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Miao T; Miller EJ; McKenzie C; Oldinski RA Physically crosslinked polyvinyl alcohol and gelatin interpenetrating polymer network theta-gels for cartilage regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3 (48), 9242–9249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Xu X; Bai B; Ding C; Wang H; Suo Y Synthesis and properties of an ecofriendly superabsorbent composite by grafting the poly(acrylic acid) onto the surface of dopamine-coated sea buckthorn branches. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2015, 54 (13), 3268–3278. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Dragan ES; Cocarta AI Smart Macroporous IPN Hydrogels Responsive to pH, Temperature, and Ionic Strength: Synthesis, Characterization, and Evaluation of Controlled Release of Drugs. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 12018–12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Zhang X; Yang P; Dai Y; Ma PA; Li X; Cheng Z; Hou Z; Kang X; Li C; Lin J Multifunctional Up-Converting Nanocomposites with Smart Polymer Brushes Gated Mesopores for Cell Imaging and Thermo/pH Dual-Responsive Drug Controlled Release. Adv. Funct. Mater 2013, 23 (33), 4067–4078. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Li X; Wang Y; Chen J; Wang Y; Ma J; Wu G Controlled release of protein from biodegradable multi-sensitive injectable poly(ether-urethane) hydrogel. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6 (5), 3640–3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Hartlieb M; Pretzel D; Wagner M; Hoeppener S; Bellstedt P; Görlach M; Englert C; Kempe K; Schubert US Core cross-linked nanogels based on the self-assembly of double hydrophilic poly(2-oxazoline) block copolymers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3 (9), 1748–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Zeng Q; Han Y; Li H; Chang J Design of a thermosensitive bioglass/agarose–alginate composite hydrogel for chronic wound healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3 (45), 8856–8864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Yin L; Fei L; Cui F; Tang C; Yin C Superporous hydrogels containing poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide)/O-carboxymethyl chitosan interpenetrating polymer networks. Biomaterials 2007, 28 (6), 1258–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Chen X; Wu W; Guo Z; Xin J; Li J Controlled insulin release from glucose-sensitive self-assembled multilayer films based on 21-arm star polymer. Biomaterials 2011, 32 (6), 1759–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mundargi RC; Rangaswamy V; Aminabhavi TM Poly(N-vinylcaprolactam-co-methacrylic acid) hydrogel microparticles for oral insulin delivery. J. Microencapsulation 2011, 28 (5), 384–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Morishita M; Goto T; Nakamura K; Lowman AM; Takayama K; Peppas NA Novel oral insulin delivery systems based on complexation polymer hydrogels: single and multiple administration studies in type 1 and 2 diabetic rats. J. Controlled Release 2006, 110 (3), 587–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Babu VR; Patel P; Mundargi RC; Rangaswamy V; Aminabhavi TM Developments in polymeric devices for oral insulin delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2008, 5 (4), 403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Mundargi RC; Rangaswamy V; Aminabhavi TM pH-Sensitive oral insulin delivery systems using Eudragit microspheres. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 2011, 37, 977–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.