Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a significant impact on public mental health. Our objective was to assess prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among the general population in Saudi Arabia during this pandemic. A descriptive cross-sectional approach was used targeting all accessible populations in Saudi Arabia. Data were collected from participants using an electronic pre-structured questionnaire. Psychological impact was assessed using the Arabic version of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21). A total of 1597 participants completed the survey. In total, 17.1% reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms; 10% reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms; and 12% reported moderate to severe stress levels. Depression, anxiety, and stress were significantly higher among females, younger respondents, and health care providers. Depression was higher among smokers, singles, and non-working respondents. Anxiety was higher among those reporting contacts with COVID-19 positive cases, previously quarantined and those with chronic health problems. Our findings reaffirm the importance of providing appropriate knowledge and specialized interventions to promote the mental well-being of the Saudi population, paying particular attention to high-risk groups.

Keywords: coronavirus, DASS-21, psychological

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the strain of coronavirus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the highly infectious illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic [1]. The first cases were reported as a zoonotic transmission event in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019 and spread to other countries, leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare COVID-19 a global health emergency of international concern [2,3]. More than 203 countries, areas, or territories have been affected by the virus so far, with about 16,670,063 infected and nearly 659,077 deaths reported by 28 July 2020 [4].

In Saudi Arabia, the first case was detected on 2 March 2020, after which there has been a rapid rise in cases [5]. As of 13 April 2020, educational institutes (schools and universities), commercial centers, restaurants, beaches, and resorts were closed, and a 24-h curfew has been implemented in many cities in Saudi Arabia [6]. Residents are authorized to leave for essentials, like food and medications, between 6 a.m. and 3 p.m. on the requirement that they stay within the limits of their living area, and only one passenger per vehicle is allowed [6]. Like many other countries, Saudi Arabia has suspended national and international travel, and citizens returning from abroad were placed under a mandatory 14-day quarantine [7]. The Saudi government temporarily banned Umrah pilgrimages to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina for Saudi citizens and the kingdom’s residents due to concerns over coronavirus [8].

Even though COVID-19 has emerged very recently, due to the unusual nature of this pandemic, several studies have already been accomplished to examine its psychological consequences, primarily in China and Europe [9,10,11]. Studies from China, the first affected country, suggests that the fear of this pandemic can bring about mental illness such as stress disorders, anxiety, depression, somatization, and behaviors such as increased alcohol and tobacco consumption [12]. Furthermore, the application of strict lockdown measures in that country affected many aspects of people’s lives, causing a wide variety of psychological problems, such as panic disorder, anxiety, and depression (9). A recent study using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and The Center for Epidemiology Scale for Depression (CES-D) carried out in China with 7236 people showed that 20.1% of participants suffered moderate to severe depressive symptoms, and 35.1% suffered moderate to severe anxiety symptoms [13].

In Spain, another study administered the Spanish version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised, an instrument examining psychological distress caused by a traumatic life event in terms of three symptomatic responses (avoidance, intrusion, and hyperarousal). Results from 3055 participants showed that 36.6% experienced psychological distress because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Avoidance was the most commonly cited symptom, with the psychological impact consistently higher for young people and women compared to men [14]. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) was administered online to 2766 respondents in Italy, revealing that 32.8% of the sample reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms; 18.7% reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms, and 27.2% reported moderate to severe stress levels [15].

Given the paucity of research addressing the mental health impacts of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia, the present study intends to assess the psychological impact of the national restrictive measures through a public cross-sectional survey that estimates the prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and stress during the last weeks of lockdown. Our objective was to describe the mental health implications of COVID-19 among our sample, and to identify potentially vulnerable groups or possible contributing factors targeting strategies to reduce the burden of mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional approach was used targeting men and women aged 18 and over in Saudi Arabia. After obtaining permission from the Institutional ethics committee, data were collected from participants using an electronic pre-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was uploaded online using social media platforms by the researchers and their relatives and friends between May 10 and 16 May 2020. The researchers constructed the survey tool after an intensive literature review and expert consultation. The tool was reviewed using a panel of 5 experts for content validity. Tool reliability was assessed using the study entire population with a reliability coefficient (α-Cronbach’s) of 0.89. The tool covered the following data: participants′ socio-demographic data like age, gender, residence, education, participants’ medical history, and participants hazardous practice regarding COVID-19 pandemic such as traveling abroad, contact with COVID-19 cases, and being quarantined. Psychological impact was assessed using the Arabic version of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21), a reliable and valid measure in assessing mental health status in Arabic speakers [16]. DASS-21 is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 21 items, seven items per subscale: depression, anxiety, and stress. Patients were asked to score every item on a scale from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much). Sum scores were computed by adding up on the items per (sub)scale and multiplying them by 2. Sum scores for the total DASS-total scale thus range between 0 and 120, and those for each of the subscales ranged between 0 and 42. Cut-off scores of 60 and 21 were used for the total DASS score and the depression subscale, respectively. These cut-off scores were derived from a set of severity ratings, proposed by Lovibond and Lovibond [17]. Once multiplied by 2, each subscale was categorized as follows (Table 1):

Table 1.

Cutoff points for DASS-21 scale.

| Severity | Depression | Anxiety | Stress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 0–9 | 0–7 | 0–14 |

| Mild | 10–13 | 8–9 | 15–18 |

| Moderate | 14–20 | 10–14 | 19–25 |

| Severe | 21–27 | 15–19 | 26–33 |

| Extremely severe | 28+ | 20+ | 34+ |

2.1. Data Analysis

After data were extracted, it was revised, coded, and fed to statistical software IBM SPSS version 22 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical analysis was completed using two-tailed tests. A p-value of less than 0.05 was statistically significant. Descriptive analysis based on frequency and percent distribution was done for all variables, including participants personal data, medical health condition, and high risk for COVID-19 practice. Scores for depression, anxiety, and stress subscales were calculated by summing up all items discrete scores. The total score for each subscale was categorized reference to the cut off points mentioned in the methodology section. Cross tabulation was used to assess the distribution of participants depression, anxiety, and stress levels by their personal and other related data. The significance of relations in cross-tabulation was tested using the Pearson chi-square test.

2.2. Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics and Research Committee of the College of Medicine of King Khalid University approved the protocol. Approval number (ECM#2020-237)—(HAPO-06-B-001)

3. Results

A total 1597 respondents completed the survey. They ranged in age from 18 to 75 years old, with a mean age of 36.6 ± 10.8 years; Males made up 54.5 % of the sample (n = 871). More than 96.1% of respondents were Saudi (n = 1535), and they were overwhelmingly university graduates (81.8%; n = 1307). Almost half (49%; n = 783) worked in the governmental sector, while only 12% (n = 188) worked in the private sector. Among all respondents, 34% (n = 542) worked in the health care sector, and over half (54.5%) had monthly incomes that exceeded 10,000 SR. More than two thirds (69.1%) of the sample were married, and almost half (46.6%; n = 547) had 3–5 children, while only 9.6% of those married had no children. Thirty-four (6.7%) female respondents were pregnant. Almost 18% (n = 283) of the sample were current smokers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Personal data of survey participants regarding psychological impact of COVID-19 on public, Saudi Arabia, 2020.

| Personal Data | No | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 871 | 54.5% |

| Female | 726 | 45.5% | |

| Age in years | <18 years | 29 | 1.8% |

| 18–25 | 270 | 16.9% | |

| 26–35 | 501 | 31.4% | |

| 36–45 | 488 | 30.6% | |

| 46–55 | 223 | 14.0% | |

| 56–65 | 77 | 4.8% | |

| >65 years | 9 | 0.6% | |

| Nationality | Non-Saudi | 62 | 3.9% |

| Saudi | 1535 | 96.1% | |

| Educational level | Below secondary | 27 | 1.7% |

| Secondary | 263 | 16.5% | |

| University/more | 1307 | 81.8% | |

| Work | Not working | 496 | 31.1% |

| Governmental sector | 783 | 49.0% | |

| Private sector | 188 | 11.8% | |

| Military sector | 130 | 8.1% | |

| Health care practitioner | Yes | 542 | 33.9% |

| No | 1055 | 66.1% | |

| Monthly income | <5000 SR | 435 | 27.2% |

| 50,00–10,000 SR | 293 | 18.3% | |

| 10,000–20,000 SR | 587 | 36.8% | |

| >20,000 SR | 282 | 17.7% | |

| Marital status | Single | 424 | 26.5% |

| Married | 1104 | 69.1% | |

| Divorced/widow | 69 | 4.3% | |

| Number of children | None | 113 | 9.6% |

| 1–2 | 373 | 31.8% | |

| 3–5 | 547 | 46.6% | |

| 6+ | 140 | 11.9% | |

| If female, pregnant? | Yes | 34 | 6.7% |

| No | 476 | 93.3% | |

| Smoking | Never smoker | 1114 | 69.8% |

| Current smoker | 283 | 17.7% | |

| Ex-smoker | 200 | 12.5% | |

Table 3 demonstrates the risk of exposure to COVID-19 among survey respondents. Approximately 8% (n = 118) had recently travelled, 35 (2.2%) had been exposed to a COVID-19 positive cases, and 38 (2.4%) were previously quarantined. Considering chronic health problems, most of the participants (73.4%; n = 1172) were healthy. The most-reported health conditions were autoimmune diseases, including asthma (7.5%; n = 119) followed by diabetes (7.1%; n = 113), hypertension with treatment (5.8%; n = 93), and immunosuppressive disorders (2.1%; n = 34).

Table 3.

Risk of exposure to COVID-19 among survey participants.

| Risk of Exposure to COVID-19 | No | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Was abroad during last three months | Yes | 118 | 7.4% |

| No | 1479 | 92.6% | |

| Contact with COVID-19 case during last month | Yes | 35 | 2.2% |

| No | 1562 | 97.8% | |

| Previously quarantined | Yes | 38 | 2.4% |

| No | 1559 | 97.6% | |

| Chronic health problems | None | 1172 | 73.4% |

| Autoimmune diseases including asthma | 119 | 7.5% | |

| Hypertension under treatment | 93 | 5.8% | |

| Chronic heart diseases | 22 | 1.4% | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 113 | 7.1% | |

| Immunosuppressive disorders | 34 | 2.1% | |

| Hypothyroidism | 32 | 2.0% | |

| Renal disorders | 5 | 0.3% | |

| Others | 91 | 5.7% | |

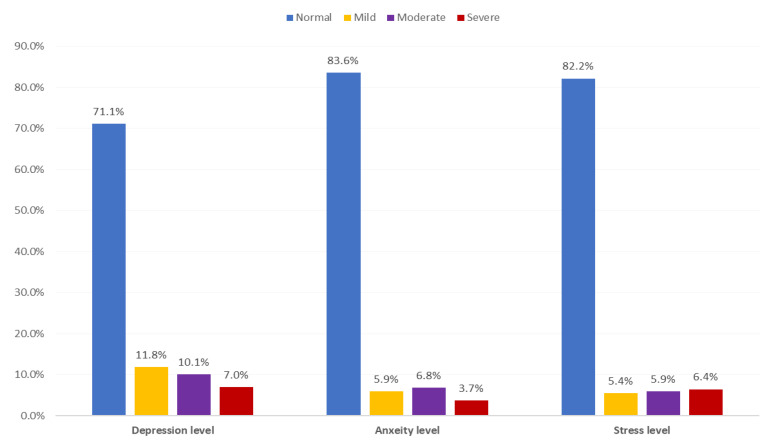

Participants’ psychological health status during COVID-19 pandemic (Table 4 and Figure 1) illustrate that over a quarter of respondents (28.9%; n = 462) reported experiencing any depression, with 11.8% reporting mild symptoms, 10.1% reporting moderate symptoms and 7% reporting severe symptoms. The most-reported depressive item was feeling downhearted and blue (50.1%), followed by not experiencing any positive feelings at all (41.55%), and lack of motivation (35.1%). More than 16% of respondents experiencing anxiety (n = 262), with more than 10% reporting moderate to severe symptoms. The most reported anxiety factors were concerns about panic and making fool of oneself (43.5%) followed by awareness of dryness of mouth (27.5%) and unexplained fear (22.5%). Almost 18% of sample respondents reported experiencing stress, with the majority (12%) reporting moderate and severe stress symptoms. The most-reported stress items were difficulty winding down (62.6%), followed by getting agitated (49.2%) and difficulty relaxing (44%).

Table 4.

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS) distribution among survey participants during COVID-19, Saudi Arabia, 2020.

| Domain | Items | Did Not Apply to Me at All | Applied to Me to Some Degree, or Some of the Time | Applied to Me to a Considerable Degree or a Good Part of Time | Applied to Me Very Much or Most of the Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | ||

| Depression | I could not seem to experience any positive feeling at all | 935 | 58.5% | 467 | 29.2% | 141 | 8.8% | 54 | 3.4% |

| I found it difficult to work up the initiative to do things | 1036 | 64.9% | 396 | 24.8% | 101 | 6.3% | 64 | 4.0% | |

| I felt that I had nothing to look forward to | 1042 | 65.2% | 376 | 23.5% | 102 | 6.4% | 77 | 4.8% | |

| I felt down hearted and blue | 797 | 49.9% | 556 | 34.8% | 133 | 8.3% | 111 | 7.0% | |

| I was unable to become enthusiastic about anything | 1174 | 73.5% | 302 | 18.9% | 72 | 4.5% | 49 | 3.1% | |

| I felt I wasn’t worth much as a person | 1224 | 76.6% | 242 | 15.2% | 84 | 5.3% | 47 | 2.9% | |

| I felt that life was meaningless | 1170 | 73.3% | 276 | 17.3% | 72 | 4.5% | 79 | 4.9% | |

| Anxiety | I was aware of dryness of my mouth | 1158 | 72.5% | 351 | 22.0% | 63 | 3.9% | 25 | 1.6% |

| I experienced breathing difficulty | 1372 | 85.9% | 176 | 11.0% | 36 | 2.3% | 13 | 0.8% | |

| I experienced trembling | 1437 | 90.0% | 133 | 8.3% | 13 | .8% | 14 | 0.9% | |

| I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself | 902 | 56.5% | 482 | 30.2% | 136 | 8.5% | 77 | 4.8% | |

| I felt I was close to panic | 1480 | 92.7% | 96 | 6.0% | 16 | 1.0% | 5 | 0.3% | |

| I was aware of the action of my heart in the absence of physical exertion | 1445 | 90.5% | 108 | 6.8% | 24 | 1.5% | 20 | 1.3% | |

| I felt scared without any good reason | 1238 | 77.5% | 277 | 17.3% | 54 | 3.4% | 28 | 1.8% | |

| Stress | I found it hard to wind down | 597 | 37.4% | 715 | 44.8% | 199 | 12.5% | 86 | 5.4% |

| I tended to over-react to situations | 962 | 60.2% | 458 | 28.7% | 129 | 8.1% | 48 | 3.0% | |

| I felt that I was using a lot of nervous energy | 957 | 59.9% | 481 | 30.1% | 104 | 6.5% | 55 | 3.4% | |

| I found myself getting agitated | 812 | 50.8% | 563 | 35.3% | 142 | 8.9% | 80 | 5.0% | |

| I found it difficult to relax | 895 | 56.0% | 468 | 29.3% | 142 | 8.9% | 92 | 5.8% | |

| I was intolerant of anything that kept me from getting on with what I was doing | 1066 | 66.8% | 392 | 24.5% | 86 | 5.4% | 53 | 3.3% | |

| I felt that I was rather touchy | 972 | 60.9% | 470 | 29.4% | 102 | 6.4% | 53 | 3.3% | |

Figure 1.

Distribution of psychological health parameters among general population in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19 pandemic, 2020.

Table 5 shows the distribution of participants psychological health aspects by their biodemographic data. Depression, anxiety, and stress were significantly higher among females than males (33.6% vs. 25%, 19.8% vs. 13.5%, and 22.2% vs. 14.2%, respectively; p < 0.05). Moreover, younger respondents (<35 years) were significantly more depressed, anxious, and stressed than older respondents (>35 years) (35.6% vs. 22.2%, 20.4% vs. 12.4%, and 23% vs. 12.7%, respectively; p < 0.05). Non-working respondents (34.5%) were more likely to report experiencing depression than those who were working, and health care practitioner, in particular, disproportionately experienced depression, anxiety, and stress (32.7% vs. 27%, 20.1% vs. 14.5%, and 22.1% vs. 15.6%, respectively; p < 0.05). Single participants were significantly more depressed and anxious than others (41.5% and 25%, respectively). More current smokers reported experiencing depression and stress than others (35.7%, and 23%, respectively). Almost a quarter (24.6%) of those who had travelled abroad were experiencing stress compared to 17.3% of non-travelers (p = 0.047). Anxiety was significantly higher among those reporting contacts with a COVID-19 positive cases (42.9% vs. 15.8%; p = 0.011), and those who were previously quarantined were more anxious than others (31.6% vs. 16%, respectively; p = 0.011). Of those suffering from chronic health problems, 21.6% were anxious compared to 14.5% of healthy persons (p = 0.001). Stress was also detected among 21.4% of high-risk participants compared to 16.6% of the healthy group (p = 0.025).

Table 5.

Distribution of participants psychological health aspects by their biodemographic data.

| Bio-Demographic Data | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | No | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 218 | 25.0% | 118 | 13.5% | 124 | 14.2% |

| Female | 244 | 33.6% | 144 | 19.8% | 161 | 22.2% | |

| p-Value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Age in years | <35 years | 285 | 35.6% | 163 | 20.4% | 184 | 23.0% |

| >35 years | 177 | 22.2% | 99 | 12.4% | 101 | 12.7% | |

| p-Value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Nationality | Non-Saudi | 23 | 37.1% | 15 | 24.2% | 14 | 22.6% |

| Saudi | 439 | 28.6% | 247 | 16.1% | 271 | 17.7% | |

| p-Value | 0.148 | 0.091 | 0.321 | ||||

| Educational level | Below secondary | 6 | 22.2% | 5 | 18.5% | 2 | 7.4% |

| Secondary | 71 | 27.0% | 37 | 14.1% | 39 | 14.8% | |

| University/ more | 385 | 29.5% | 220 | 16.8% | 244 | 18.7% | |

| p-Value | 0.536 | 0.520 | 0.120 | ||||

| Work | Not working | 171 | 34.5% | 87 | 17.5% | 97 | 19.6% |

| Governmental sector | 203 | 25.9% | 126 | 16.1% | 132 | 16.9% | |

| Private sector | 51 | 27.1% | 26 | 13.8% | 37 | 19.7% | |

| Military sector | 37 | 28.5% | 23 | 17.7% | 19 | 14.6% | |

| p-Value | 0.011 * | 0.662 | 0.412 | ||||

| Health care practitioner | Yes | 177 | 32.7% | 109 | 20.1% | 120 | 22.1% |

| No | 285 | 27.0% | 153 | 14.5% | 165 | 15.6% | |

| p-Value | 0.019 * | 0.004 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Marital status | Single | 176 | 41.5% | 89 | 21.0% | 106 | 25.0% |

| Married | 266 | 24.1% | 155 | 14.0% | 165 | 14.9% | |

| Divorced/ widow | 20 | 29.0% | 18 | 26.1% | 14 | 20.3% | |

| p-Value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| Number of children | None | 30 | 26.5% | 21 | 18.6% | 15 | 13.3% |

| 1–2 | 117 | 31.4% | 73 | 19.6% | 83 | 22.3% | |

| 3–5 | 124 | 22.7% | 70 | 12.8% | 75 | 13.7% | |

| 6+ | 15 | 10.7% | 9 | 6.4% | 6 | 4.3% | |

| p-Value | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | 0.001 * | ||||

| If female, pregnant? | Yes | 14 | 41.2% | 7 | 20.6% | 10 | 29.4% |

| No | 138 | 29.0% | 88 | 18.5% | 90 | 18.9% | |

| p-Value | 0.133 | 0.761 | 0.136 | ||||

| Smoking | Never smoker | 311 | 27.9% | 181 | 16.2% | 190 | 17.1% |

| Current smoker | 101 | 35.7% | 52 | 18.4% | 65 | 23.0% | |

| Ex-smoker | 50 | 25.0% | 29 | 14.5% | 30 | 15.0% | |

| p-Value | 0.015 * | 0.509 | 0.036 * | ||||

| Was abroad during last three months | Yes | 41 | 34.7% | 26 | 22.0% | 29 | 24.6% |

| No | 421 | 28.5% | 236 | 16.0% | 256 | 17.3% | |

| p-Value | 0.148 | 0.086 | 0.047 * | ||||

| Contact with COVID-19 case during last month | Yes | 15 | 42.9% | 15 | 42.9% | 9 | 25.7% |

| No | 447 | 28.6% | 247 | 15.8% | 276 | 17.7% | |

| p-Value | 0.066 | 0.001 * | 0.219 | ||||

| Previously quarantined | Yes | 11 | 28.9% | 12 | 31.6% | 5 | 13.2% |

| No | 451 | 28.9% | 250 | 16.0% | 280 | 18.0% | |

| p-Value | 0.998 | 0.011 * | 0.445 | ||||

| Chronic health problems | None | 326 | 27.8% | 170 | 14.5% | 194 | 16.6% |

| High risk health condition | 136 | 32.0% | 92 | 21.6% | 91 | 21.4% | |

| p-Value | 0.103 | 0.001 * | 0.025 * | ||||

P: Pearson X2 test; * p < 0.05 (significant).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the general population of Saudi Arabia. Our survey of 1597 respondents a cross Saudi Arabia showed that 28.9% of respondents reported depressive symptoms, 16.4% reported anxiety symptoms and 17.8% reported stress symptoms. Moderate to severe features of depression, anxiety, and stress were experienced by 17.1%, 10.5%, and 12.3%, respectively. Our respondents were less likely to report experiencing anxiety and stress compared to other international studies, such as those from Iran, where the prevalence of severe anxiety was 19.1% [18], and China where moderate to severe anxiety and stress were 28.8% and 29.6 %, respectively [19]. The results of this study are similar to the results of a study conducted in Spain by Jimenez O. et al., at about the same period of time [20].

Our results suggested that being female was associated with increased depression, anxiety, and stress, which is similar to finding reported in previous studies [9,19], and similar to evidence in international literature demonstrating females tend to be more susceptible to stress and post-traumatic symptoms [20].

In the present research, young age was found to be associated with increased depression, anxiety, and stress. To date, the literature reports mixed results for this variable concerning the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 crisis [9,20,21,22,23,24]. Some literature in the field of disaster reveals that the elderly is particularly vulnerable to the adverse psychological sequelae of critical situations, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [25]. However, in agreement with our results, most of the studies have found that age constitutes a protective effect, and this trend may be explained by their greater life experience, previous disaster exposure, or having to face fewer life responsibilities [26]. Some researchers have suggested that higher anxiety amidst the younger population may be due to their greater access to information via social media, which can easily provoke stress [27]. Furthermore, it is speculated that the crisis might be presenting a much greater range of difficulties for the working-age, rather than elder age groups. For example, in addition to financial worries, it is possible that COVID-19 may be currently inducing other stressors in younger age groups that similarly impacts mental health, such as the need for both parents to telework from home while also homeschooling their children. Other factors might be important in this context, an earlier study found, for example, that older adults were more psychologically resilient than their younger counterparts [28], which might be important when it comes to reacting to the sources of stress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Being married was a protective factor against psychological suffering, as has usually been found in the literature [29,30,31]. Strangely, having children turned out to be a protective factor against psychological distress. While one might assume that being impounded at home with children may cause a higher degree of anxiety and stress, our data showed otherwise. Consistent with results from studies showing that parenthood increases subjective well-being [29,32,33], our findings likewise showed that being a parent confers a level of protection from COVID-19 related mental health issues.

In contrast to Wang C. et al., study results [19], educational level has no significant association with the psychological impact of COVID-19, a finding similar to a Chinese study [34]. One explanation is that most of the participants in the current study hold university education or higher, and they all completed the online questionnaire by themselves, indicating they have access to online sources of information, thus attenuating the impact of educational background.

The present study found an association between a history of chronic medical problems and increased anxiety and stress. These finding echoes previous studies indicating that chronic illness or a self-evaluation of poor health is associated with increased psychological distress [19,35]. A possible interpretation for this finding is that persons with a history of medical problems who also perceive their health as weak might feel more vulnerable to contracting a new disease [36].

Smoking was associated with a higher degree of depression and stress, which could be attributed to the awareness of smokers that they have a high chance of developing more medical complications if they were infected with COVID-19 because of smoking habits [37].

The results showed that health care workers were associated with increased stress anxiety, and depression. Such workers tend to have a high degree of contact with the public, and hence are at a higher likelihood of being infected; this may increase their stress levels. Moreover, this is in agreement with previous studies published recently and during the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in Saudi Arabia and studies conducted during the current COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore and India [38,39,40,41]. In addition to that, individuals who reported having contact with COVID-19 patients or history of travel abroad were found to experience higher level of depression, anxiety, and stress; and this can be attributed to different reasons, first the increased risk of contracting the disease because they may have been in contact with an infected person; secondly, he/she is worried about the health condition of his/her family, friends or colleagues.

This study had some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the data. The first one we do not have a DASS-21 baseline of pre-pandemic data and detailed pre-post analyses could not be done; hence, we cannot be sure of any increase in distress levels or if any increase (if validated) was COVID-19 related. The survey provides only a snapshot of psychological responses at a particular point in time, and a longitudinal study is required to provide information on whether the observed impact will last for more extended periods. Another limitation, the quality of cohabitation was not included in this study, while it was shown to be a key variable in the psychological impact of the participants, since its poorer quality was related to higher scores of stresses [20]. The psychological self-reported effects, anxiety, depression, and stress may not adequately represent the mental health status assessed in an interview; thus, for the outcome to be determined, prospective studies are necessary to provide more accurate data to support the need for focused public mental health strategies.

5. Conclusions

Depression, anxiety, and stress are prevalent among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Saudi Arabia. We identified the specific subgroups of the general population at higher risk: females, those living alone during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, people with a history of smoking or chronic medical problems, and healthcare providers. Medical Authorities should focus on providing appropriate knowledge about the disease using appropriate methods, and specialized interventions to promote the mental well-being of the Saudi population, paying particular attention to high-risk groups. For instance, healthcare workers are known to be at a higher level of risk and thus should be prioritized when such interventions are implemented. Moreover, community mental health care should be made accessible to people who are at increased risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Sherry Larkins for reviewing the manuscript and providing professional language help.

Author Contributions

All authors had nearly the same role regarding idea conceptualization, data collection, original draft writing and review, and final draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institute of Research and Counselling Studies at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia (grant number 2020-S51-18).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: Classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishiura H., Jung S.M., Linton N.M., Kinoshita R., Yang Y., Hayashi K., Kobayashi T., Yuan B., Akhmetzhanov A.R. The Extent of Transmission of Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China, 2020. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:330. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Situation Reports. [(accessed on 20 November 2020)];2020 Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novelcoronavirus-2019/situation-reports.

- 4.Medicine JHU Coronavirus Resource Center. [(accessed on 20 November 2020)];2020 Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- 5.1389 New COVID-19 Cases and 1626 Recoveries, MOH Says [Press Release] Ministry of Health; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Aug 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdallah N. Saudi Arabia Imposes 24-Hour Curfew in Riyadh and Other Cities. Reuters. Apr 6, 2020.

- 7.Ministry of transportation Saudi Arabia Suspends International Flights Starting Sunday to Prevent Spread of Coronavirus. Arab News. Mar 14, 2020.

- 8.Samar Ahmed M.R. Saudi Arabia to Bar Arrivals from Abroad to Attend the Haj. Reuters. Jun 22, 2020.

- 9.Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry. 2020;33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagiolini A., Cuomo A., Frank E. COVID-19 Diary from a Psychiatry Department in Italy. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2020;81:20com13357. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20com13357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porcheddu R., Serra C., Kelvin D., Kelvin N., Rubino S. Similarity in Case Fatality Rates (CFR) of COVID-19/SARS-COV-2 in Italy and China. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2020;14:125–128. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shigemura J., Ursano R.J., Morganstein J.C., Kurosawa M., Benedek D.M. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020;74:281–282. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y., Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Rey R., Garrido-Hernansaiz H., Collado S. Psychological impact of COVID-19 in Spain: Early data report. Psychol. Trauma. 2020;12:550–552. doi: 10.1037/tra0000943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazza C., Ricci E., Biondi S., Colasanti M., Ferracuti S., Napoli C., Roma P. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali A.M., Ahmed A., Sharaf A., Kawakami N., Abdeldayem S.M., Green J. The Arabic Version of The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21: Cumulative scaling and discriminant-validation testing. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2017;30:56–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovibond S.H., Lovibond P.F., Psychology Foundation of Australia . Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia; Sydney, NSW, Australia: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;51:102076. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiménez Ó., Sánchez-Sánchez L.C., García-Montes J.M. Psychological impact of COVID-19 confinement and its relationship with meditation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:6642. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sareen J., Erickson J., Medved M.I., Asmundson G.J., Enns M.W., Stein M., Leslie W., Doupe M., Logsetty S. Risk factors for post-injury mental health problems. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:321–327. doi: 10.1002/da.22077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor M.R., Agho K.E., Stevens G.J., Raphael B. Factors influencing psychological distress during a disease epidemic: Data from Australia’s first outbreak of equine influenza. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:347. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian F., Li H., Tian S., Yang J., Shao J., Tian C. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112992. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y., Zhao N. Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Who will be the high-risk group? Psychol. Health Med. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia Z., Tian W., Liu W., Cao Y., Yan J., Shun Z. Are the elderly more vulnerable to psychological impact of natural disaster? A population-based survey of adult survivors of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngo E.B. When Disasters and Age Collide: Reviewing Vulnerability of the Elderly. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2001;2:80–89. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2001)2:2(80). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng C., Jun H., Liang B. Psychological health diathesis assessment system: A nationwide survey of resilient trait scale for Chinese adults. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 2014;12:735–742. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gooding P.A., Hurst A., Johnson J., Tarrier N. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2012;27:262–270. doi: 10.1002/gps.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodríguez-Rey R., Garrido-Hernansaiz H., Collado S. Psychological Impact and Associated Factors During the Initial Stage of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Among the General Population in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:1540. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frech A., Williams K. Depression and the psychological benefits of entering marriage. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2007;48:149–163. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalmijn M. The Ambiguous Link between Marriage and Health: A Dynamic Reanalysis of Loss and Gain Effects. Soc. Forces. 2017;95:1607–1636. doi: 10.1093/sf/sox015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radó M.K. Tracking the Effects of Parenthood on Subjective Well-Being: Evidence from Hungary. J. Happiness Stud. 2020;21:2069–2094. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00166-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nomaguchi K.M. Parenthood and psychological well-being: Clarifying the role of child age and parent-child relationship quality. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012;41:489–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai X., Hu X., Ekumi I.O., Wang J., An Y., Li Z., Yuan B. Psychological Distress and Its Correlates Among COVID-19 Survivors During Early Convalescence Across Age Groups. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2020;28:1030–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho C.S.H., Tan E.L.Y., Ho R.C.M., Chiu M.Y.L. Relationship of Anxiety and Depression with Respiratory Symptoms: Comparison between Depressed and Non-Depressed Smokers in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16:163. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16010163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hatch R., Young D., Barber V., Griffiths J., Harrison D.A., Watkinson P. Anxiety, Depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after critical illness: A UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22:310. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2223-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alqahtani J.S., Oyelade T., Aldhahir A.M., Alghamdi S.M., Almehmadi M., Alqahtani A.S., Quaderi S., Mandal M., Hurst J.R. Prevalence, Severity and Mortality associated with COPD and Smoking in patients with COVID-19: A Rapid Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0233147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan B.Y.Q., Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Jing M., Goh Y., Yeo L.L.L., Zhang K., Chin H.-K., Ahmad A., Khan F.A., et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;173:317–320. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Tan B.Y.Q., Jing M., Goh Y., Ngiam N.J.H., Yeo L.L.L., Ahmad A., Khan F.A., Shanmugam G.N., et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alsubaie S., Hani Temsah M., Al-Eyadhy A.A., Gossady I., Hasan G.M., Al-Rabiaah A., Jamal A.A., Alhaboob A.A., Alsohime F., Somily A.M. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus epidemic impact on healthcare workers’ risk perceptions, work and personal lives. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019;13:920–926. doi: 10.3855/jidc.11753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Temsah M.H., Al-Sohime F., Alamro N., Al-Eyadhy A., Al-Hasan K., Jamal A., Al-Maglouth I., Aljamaan F., Al Amri M., Barry M., et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020;13:877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]