Abstract

We develop a new mathematical model by including the resistive class together with quarantine class and use it to investigate the transmission dynamics of the novel corona virus disease (COVID-19). Our developed model consists of four compartments, namely the susceptible class, the healthy (resistive) class, the infected class, and the quarantine class, . We derive basic properties like, boundedness and positivity, of our proposed model in a biologically feasible region. To discuss the local as well as the global behaviour of the possible equilibria of the model, we compute the threshold quantity. The linearization and Lyapunov function theory are used to derive conditions for the stability analysis of the possible equilibrium states. We present numerical simulations to support our investigations. The simulations are compared with the available real data for Wuhan city in China, where the infection was initially originated.

Keywords: Mathematical model, COVID 19, Basic reproduction number, Linearization theory, Lyapunov function, Stability analysis, Numerical simulations

1. Introduction

Communicable diseases have always been an important part of human history. Large number of outbreaks have been occurred in human history due to which millions of people lost their lives. For instance the outbreak that occurred in the previous century, known as Spanish flow during which millions of people died. Many of such diseases then became endemic like HIV/AIDS due to which thousands of people are dying each year. In the last two decades, two corona-virus epidemics have been reported [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. Such micro organism are classes of viruses that can result infections in humans, ranging from the common cold to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The first corona-virus epidemic, known as SARS has effected more than eight thousand infections with eight hundred deaths. The second one, called MERS, spread from Saudi Arabia to number of other countries. About 25,000 individuals were infected with it among which nearly thousand people lost their life. MERS is still a root of some cases [6]. Nearly a year ago, a severe respirational infection originated in the Wuhan city of China [7]. It was reported that the main cause of this infection was the new coronavirus (COVID-9). It is reported that the disease was first transmitted from animals to humans [8]. Some researchers say that bats have the corona virus from which it was transmitted to the humans, as all the patients that were first identified working in wet market in the Wuhan city [9]. The infection was then transmitted very rapidly in the whole city of during the months of January and February 2020. Due to international travel, in March 2020 some patients were identified in USA, Thailand and Korea. Then it was also announced that the disease is contagious as it is transmitted from person to person by contact. During the mid of Mach 2020, WHO announced that the infection to be an outbreak [10]. One virologists named it ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome’ corona virus (SARS-CoV-2). There are many claims and several theories about the origin of COVID-19 in which the most probable is that it might have been originated from bat [11], or from a seafood market exposure [12]. As the disease is contagious, international travel could expedite the spread of the virus [13]. The novel corona virus outbreak currently as the most remarkable in the recent history. By April 2020, COVID-19 affected nearly the whole globe [14]. Researchers in the area of epidemiology and other branches of biology are working day and night to find treatment or vaccine for this disease. They use different tools to understand the procedure through which the disease transmits in a society and how to reduce or control it. The process of infectious diseases may be easily understood and described by using mathematical models [15], [16], [17].

Mathematical model is a powerful tool that effectively helps in investigation of real world phenomenon and processes [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. Bernoulli was the first mathematician who gave idea about mathematical modeling of spread of an infectious disease during 1760. After that numerous researchers took interest in the said area. One can easily understand various physical and biological phenomenon and their mechanism through such models. This area has been very well extended from simple models to more complex and complicated models. With the help mathematical models, large number of infectious and other diseases have been studied e.g., see [19], [20]. Using mathematical models, researchers first try to understand the dynamics of a disease, and afterwards they develop control and curing procedures for it. For some famous study in this regard, we refer [23], [24], [25], [26].

The researchers have used the tools of nonlinear numerical analysis to establish the global, local stability for the endemic and disease free equilibrium (DFE). In same line recently researchers have greatly investigated the novel COVID-19 through mathematical models from different aspects. The concerned investigations are devoted to stability theory, numerical simulation and global local dynamics. In this regards we have referred here some good work like [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33].

In all previous models the researchers have considered various compartments but to the best of our knowledge the resistive compartment along with quarantined class has not been reported yet. Our model makes the investigation unique by this way that we have involved the resistive class together with quarantined class in construction of our new model.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we describe mathematical model for the current COVID-19 and discuss its fundamental mathematical properties in a biologically feasible region. We perform the stability analysis in Section 3 and derive the basic reproduction number. In the same section we find conditions for the local as well as the global behaviour of the possible equilibria of the proposed model. In Section 4 we present numerical simulations to support and verify our analytical findings. These simulations are performed for biologically feasible values of the parameters of the model. Finally we conclude our work in Section 5.

2. Formulation of the model

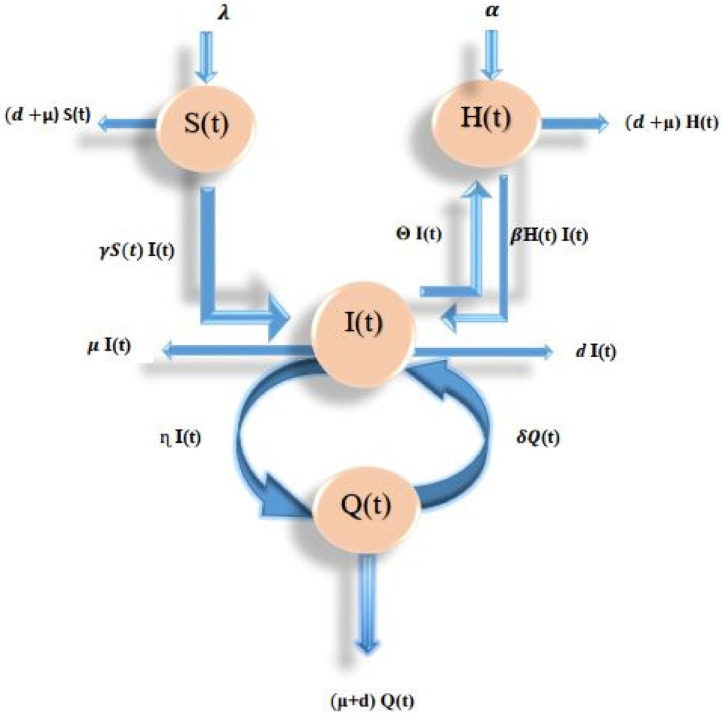

Inspired from the above mentioned literature, we develop a new mathematical model based on susceptible individuals healthy or resistant individuals infected and quarantine individuals respectively. All the parameters involved in the model are assumed to be non-negative. The susceptible individuals initially move to the infectious class with a constant flow rate. The suspected or infected individuals move to the quarantine class and confirmed cases are send back to the infected compartment for further treatment. Our model under consideration is expressed in the form of the following autonomous ordinary differential equations

| (1) |

The description of parameters in (1) is given in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Parameters and their explanation in the model (1).

| Parameters | The physical interpretation |

|---|---|

| Recruitment rate susceptible | |

| Disease transmission rate | |

| Natural death rate | |

| Recruitment rate of healthy human | |

| Transmission rate of healthy human | |

| Disease related death rate infected or suspected individuals | |

| Rate at which quarantine people get infection | |

| Cure rate of infected people in the quarantine class |

A systematic diagram of the model is given in Flow Chart 2 :

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the model (1) under consideration+.

We will investigate (1) under the following biologically feasible initial conditions

| (2) |

Let denotes the total population at time then we have

Taking the temporal derivatives of and using (1), one observes that obeys the law of mass action

| (3) |

Note that (3) is an exact differential equation with solution

| (4) |

Hence it is deduced that (4) possesses positive definite solutions for all .

Theorem 2.1

The dynamical system(1)exhibits boundedness for all non-negative initial conditions which are not all identically zero in the entire region given by

Proof

Assume that be any solution set of the model (1) with some non-negative initial conditions such as

(5) corresponding to any other non-negative initial conditions on and . Since is a positive parameter, so that from (3) one may write

Solving this equation leads to

where is the initial value of the total population of the dynamical system. Thus, for we have

(6) Hence is positive and bounded, and is the largest set for which the solutions are positive and bounded. This completes the proof of the theorem. □

3. Stability analysis

We will focus our attention on determining the possible stationary states of the system (1) and on deriving stability results. We consider the situation, when there is no infection of the disease in the community. The concerned state is called DFE. In the following, we denote such equilibrium by .

3.1. DFE state

Inserting in the given system and solving the autonomous differential Eq. (1) for and we obtain

To calculate the endemic equilibrium, we first need to determine the threshold quantity which plays a significant role in determining the global behavior of the given dynamical system.

3.2. Basic reproductive number

We follow the traditional technique, the next generation method [34] to derive . Let denotes the infectious class in model (1). We can write

| (7) |

The Jacobians of the above matrices are respectively given by

The multiplicative inverse of the matrix is calculated as

The next generation matrix for the DFE of the proposed problem is given by

The spectral parameter of this matrix gives the threshold parameter . Thus is given by

| (8) |

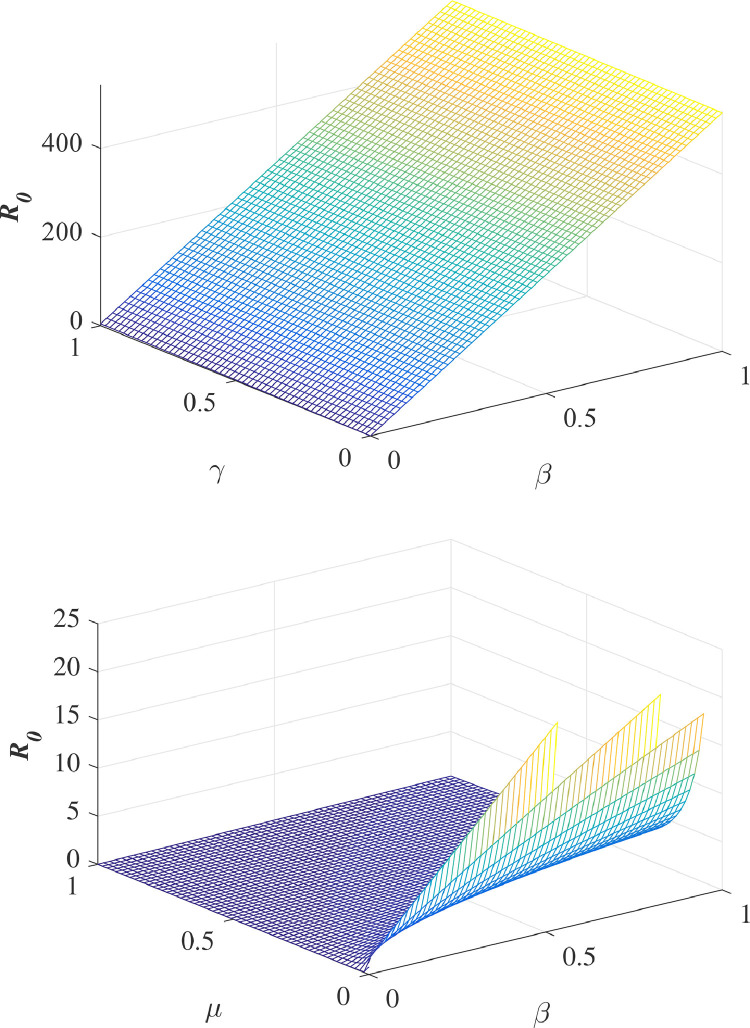

In Fig. 2 , we plot against different parameters involved in the model under consideration.

Fig. 2.

Plot of the basic reproduction number in terms of various parameters involved in the model under consideration.

3.3. Local stability at the DFE state

After determining the threshold quantity, we are now in position to derive stability conditions for our model.

Theorem 3.1

The DFE of the dynamical system(1)is locally asymptotically stable equipped the threshold quantityand

The DFE is unstable forand in the contrast of.

Proof

The local stability of for the proposed model (1) can be inquired by taking the Jacobian matrix of the form

(9) Exploiting elementary row operations, the last matrix yields

(10) where

Obviously the matrix (10) has eigenvalues . The remaining two eigenvalues and are negative if and only if

(11) Hence re-arranging the inequality (11) implies that Thus condition holds along with which shows that the system (1) exhibits the local asymptotical stability. On the other hand, we see that if has non-negative real part showing instability of the given system with growing time. This completes the proof of the theorem. □

3.4. Global stability of the DFE state

In this section, we discuss the global stability of the disease free state. In the following, we derive conditions for the global stability of the disease fee equilibrium using Castillo-Chaves [35]. The global stability of the DFE depends upon the following two conditions

where represents the susceptible and healthy classes, i.e., while denotes the infected and quarantine individuals, at the DFE point Thus the existence of the global asymptotic stability of depends upon the following conditions.

-

If then is globally asymptotically stable;

-

where for .

In the condition is an M-matrix having non-negative off diagonal entries, where represents the feasible region in biological sense. Thus the following Lemma holds.

Lemma 3.2

Ifthen the equilibrium pointof the dynamical system(1)is globally asymptotically stable whenever conditionsandare satisfied.

Theorem 3.3

Forthe system(1)exhibits global asymptotic stability at the DFE point

Proof

In order to prove the above theorem, we need to verify conditions and Let us use the symbols and and define where . With the use of system (1), we may write

(12) and

(13) Now if and Thus we conclude that whenever . From which one can say that is globally asymptotically stable. Similarly for the second condition, we need to express

(14) where is the Jacobian matrix of infected and quarantine classes at and Therefore, one may verify that matrix is of the form

(15) By taking

(16) we arrive at

(17) The total population of dynamical system is bounded by and such that from which it follows that . Thus is positive definite. Furthermore, the off diagonal elements of the M-matrix are non-negative. Thus conditions and are satisfied. So by Lemma stated above, the DFE is globally asymptotically stable. □

3.5. Endemic equilibrium point and backward bifurcation

In this subsection we determine the endemic equilibrium point of the model (1), i.e., when the infected individuals of the system are non-zero. We take the following steps. Let represent an arbitrary endemic equilibrium point of the dynamical system (1). Solving simultaneously equations of the model(1) at steady state gives

| (18) |

Obviously for the endemic state, we have Substituting and in the third equation of the model (1) at stationary state, one obtains the following quadratic equation

| (19) |

where and Surely the coefficient is always positive, as the parameters and are positive. Moreover is negative (positive) for is greater (less) than unity. Thus (19) depends upon the signs of and respectively to get its positive solutions. Now if is greater than unity, then two roots of (19) are positive real values and hence the endemic equilibrium state is unique. If is one, then is zero and hence there is either a trivial or no endemic state. The whole discussion shows that the endemic equilibrium of the model under consideration depends on . Thus there exists an interval such that

| (20) |

If is non-negative and either or then there have no positive solution of (19) and have no endemic equilibrium state. Finally, we establish the following result for various range of parameters.

Theorem 3.4

The model(1)has the following set of facts

Case 3 in Theorem (3.4) illustrates the existence of phenomenon of backward bifurcation, where the local asymptotic stabilities of both DFE as well endemic equilibrium co-exist, when [36], [37]. Now to probe the backward bifurcation, we must set the discriminant to zero in order to obtain critical value of . We obtain

| (21) |

Thus backward bifurcation occurs, when or equivalently The phenomenon of backward bifurcation and its epidemiological significance needs a classical requirement of although this condition is necessary but no longer sufficient to eliminate the disease. In same scenario,the disease elimination depends upon the initial state variables or initial size of the sub population of the system. The backward bifurcation in the same model (1) suggests the feasibility of controlling the disease when threshold quantity is greater than one and would depend on the initial stature of the sub-population of the system (1).

Lemma 3.5

The dynamical system(1)endures backward bifurcation when case 3 of theorem (3.4)holds along with

Lemma 3.6

Atthe system(1)undergoes backward bifurcation if and only if

Proof

For the sufficient part, assume the graph of Now if implies that and hence . Consequently graph of the function passes through origin. Furthermore, has a positive root if If we exceed from zero to some value . This guarantees that there exists an open interval which contains where has two real and positive roots. In short words, we try to show if then there are two endemic equilibrium states. The necessity is conspicuous, if (19) has no real positive roots, when □

3.6. Local stability of endemic equilibrium state

The following theorem is enough to show that the system(1) performs local stability at the endemic equilibrium point .

Theorem 3.7

The unique endemic equilibrium stateof model(1)is locally asymptotically stable provided.

Proof

The Jacobian matrix of the proposed model (1) for unique endemic equilibrium state is given by

(22) To know about the nature of the eigenvalues of the matrix (22), it is advantageous to apply the traditional row operations to obtain

(23) where The eigenvalues of are and In addition if and only if After using simple algebra we can rewrite

(24) Clearly all the coefficients of (24) are positive if and .Thus conditions of the above stated theorem are satisfied and consequently result in the local asymptotic stability of the endemic equilibrium . □

3.7. Global stability of endemic equilibrium state

In this section we explore the global stability of the endemic equilibrium point of our propose model (1)in terms of the basic reproduction number .

Theorem 3.8

The endemic equilibrium stateof model(1)is globally asymptotically stable, ifotherwise unstable.

Proof

To study the global stability of the model(1) under consideration we construct the following Lyapunov function.

(25) Clearly at the endemic state the function for the prescribed values of and . Further the given function is strictly positive, whenever and . This implies that the function for the given is positive semi-definite.

The time derivative of the function results in

(26) Inserting values from (1) into (26) and performing algebraic manipulation, (26) can be formatted as

(27) Clearly for and This mean that the time rate derivative of the defined function is negative semi definite. From which we have that is the largest invariant sub set in support that the endemic equilibrium state of the dynamical system (1) is globally asymptotically stable under the condition . The graphical investigation of the above theorem is illustrated in Fig. 2. □

4. Numerical results and discussion

Here we use RK4 method to perform the numerical simulations using some real data of as in the following Table 2

Table 2.

Description of the parameters used in model (1).

| Parameters | The physical interpretation | Numerical value |

|---|---|---|

| The susceptible population (recruit for test) | 1000 thousands | |

| The resistant population | 790 thousands | |

| The infected population | 170 thousands | |

| The quarantined population | 450 thousands | |

| Recruitment rate of susceptible | 0.0043217 | |

| Disease transmission rate | 0.125 | |

| Natural death rate | 0.002 | |

| Recruitment rate of healthy human | 0.535 | |

| Transmission rate of healthy human | 0.0056 | |

| Disease related death rate infected or suspected individuals | 0.0008 | |

| Rate at which quarantine people getting infection | 0.029 | |

| Cure rate of infected people in quarantine | 0.35 | |

| Contact rate of infected and healthy people | 0.025 |

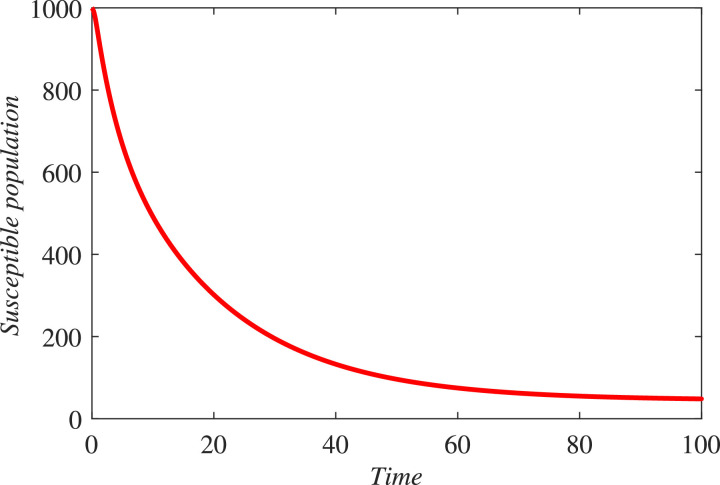

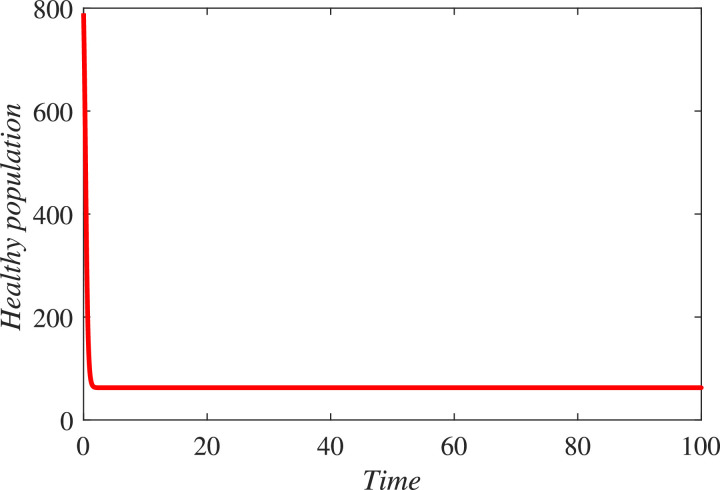

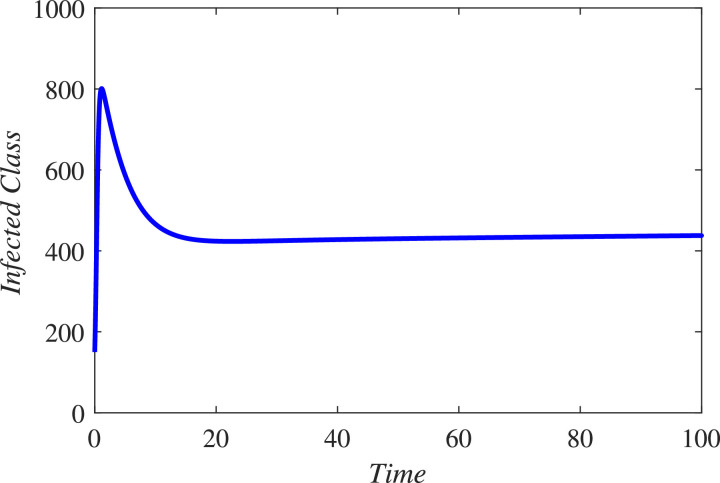

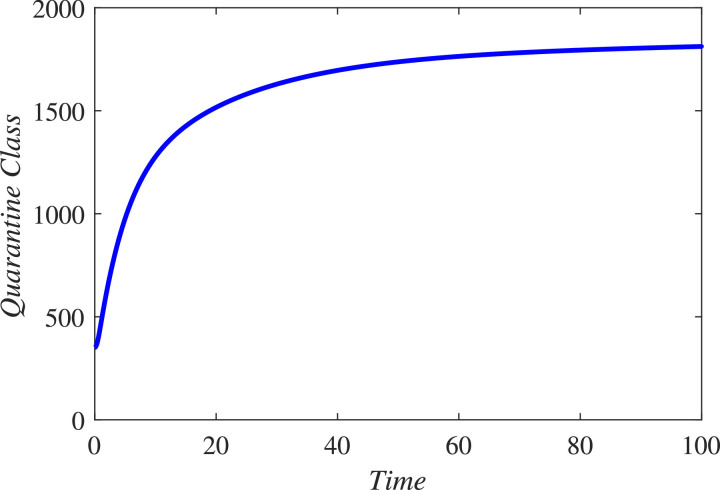

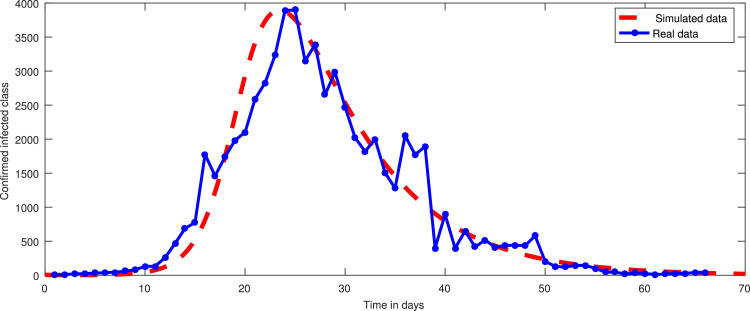

In the first hundred days in a locality, one thousand individuals were found susceptible, among which 170 were founded infected and 790 were declared healthy. 450 individuals either died or got rid from the infection. The infected individuals were quarantined. We simulated the new constructed model under these information and found that in coming few months the infectious will grow exponentially and hence more people will be quarantined if the people and government of a locality do not properly follow SOPs. As a result the resistive population decreases and this causes increase the classes and . It can be observed from Fig. 3 that susceptibility is decreasing and as a result healthy population also declines, as shown in Fig. 4 . Hence the infected and the quarantined classes are growing up, see Figures 5 and 6 respectively. The asymptotic stability behavior is clearly observed from these plots. Next, using available data of Wuhan city (China) and using the proposed model, we compared the real and simulated data for infected class as reported in [38], [39] for initial sixty eight days from 4th January 2020 to 8th March 2020 as The concerned parametric values in the model are taken as Where for compartments, we use the initial conditions We compare the simulated and real data in Fig. 7 . We rather see a very good agreement between the simulated and real data.

Fig. 3.

Dynamical behavior of the susceptible class (population).

Fig. 4.

Dynamical behavior of the resistive class (population).

Fig. 5.

Dynamical behavior of the infected class (population).

Fig. 6.

Dynamical behavior of the quarantined class (population) (population) for the considered model (1).

Fig. 7.

Comparison between simulated data and real data for the infected class using the model (1).

5. Conclusion

We have established a new model by considering the resistive class together with quarantine class for the transmission dynamics of COVID-19. Exploiting the Lyapunov function theory, we have developed sufficient conditions for global and local stability of the disease free and the endemic equilibria of our model in terms of the threshold quantity. We have shown the positivity and boundedness of solutions of the model in a feasible region. To support and verify our analytical work, we have performed numerical simulations. This has been achieved using the RK4 method by taking some real data of the city Wuhan in China.

It is well known fact that fractional analysis is a hot area of research in the recent time. Fractional calculus has been found very effective in modelling various real world phenomenon. Researchers have focused their attention on studying models of infectious disease like HIV, AIDS, etc under fractional order derivatives and integrals. For more detail we refer [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]. Some authors have also extended the area to classical and arbitrary order mathematical models of real world problems in physical sciences, see, for instance, [45], [46]. Our next step is to investigate the qualitative and numerical aspects of our proposed under different fractional order derivatives. Work on this is in progress and will be reported in a future publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Saeed Ahmad: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Saud Owyed: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Abdel-Haleem Abdel-Aty: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Emad E. Mahmoud: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Kamal Shah: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Hussam Alrabaiah: Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

I declare that I have no significant competing financial, professional, or personal interests that might have influenced the performance or presentation of the work. Also, we do not have any conflict of interest regarding this paper.

Acknowledgments

Saud Owyed and Abdel-Haleem Abdel-Aty extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at the University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through the COVID-19 Initiative Project under Grant Number (UB-COVID-31-1441). Emad E. Mahmoud acknowledges Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/20), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Hinedi K., Ghandour J., Khairalla H., Musleh S., Ujayli A., et al. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a case-control study of hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):160–165. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azhar E.I., El-Kafrawy S.A., Farraj S.A., Hassan A.M., Al-Saeed M.S., Hashem A.M., et al. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of mers coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2499–2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Y., Lee S., Chu C., Choe S., Hong S., Shin Y. The characteristics of middle eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus transmission dynamics in South Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2016;7(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Aty A.-H., Khater M.M.A., Dutta H., Bouslimi J., Omri M. Computational solutions of the HIV-1 infection of CD4+t-cells fractional mathematical model that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) with the effect of antiviral drug therapy. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139:110092. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alnaser W.E., Abdel-Aty M., Al-Ubaydli O. Mathematical prospective of coronavirus infections in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Inf Sci Lett. 2020;9(1):51–64. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z., Zhang W., Lu Y., Guo C., Guo Z., Liao C., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Han X., Li Q., et al. From SARS-CoV to Wuhan 2019-nCoV outbreak: similarity of early epidemic and prediction of future trends. 2020. CELL-HOST-MICROBE-D-20-00063.

- 7.Backer J.A., Klinkenberg D., Wallinga J. Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20-28 january 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(5) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhandapani P.B., Baleanu D., Thippan J., Sivakumar V.. On stiff, fuzzy IRD-14 day average transmission model of COVID-19 pandemic disease. AIMS Bioeng2020; 7:208–223.

- 9.Bozkurt F., Yousef A., Baleanu D., Alzabut J. A mathematical model of the evolution and spread of pathogenic coronaviruses from natural host to human host. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;138:109931. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World health organization: coronavirus disease 2019. 2020. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus. [PubMed]

- 11.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.L., Chen H.D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.D., Liu M.Q., Chen Y., Shen X.R., Wang X., Zheng X.S., Zhao K., Chen Q.J., Deng F., Liu L.L., Yan B., Zhan F.X., Wang Y.Y., Xiao G.F., Shi Z.L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogoch I.I., Watts A., Thomas B.A., Huber C., Kraemer M.U., Khan K. Pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: potential for international spread via commercial air travel. J Travel Med. 2020;27:1–2. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Razai M.S., Doerholt K., Ladhani S., Oakeshott P. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a guide for UK GPs. BMJ. 2020;368:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahzad M., Abdel-Aty A.-H., Attia R.A.M., Khoshnaw S.H.A., Aldila D., Ali M., Sultan F. Dynamics models for identifying the key transmission parameters of the COVID-19 disease. Alexandria Engineering Journal. 2020 [Google Scholar]; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2020.10.006

- 16.Abdel-Aty A.-H., Khater M.M.A., Attia R.A.M., Eleuch H. Exact traveling and nano-solitons wave solitons of the ionic waves propagating along microtubules in living cells. Mathematics. 2020;8:697. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khater M.M.A., Attia R.A.M., Abdel-Aty A., Alharbi W., Lu D. Abundant analytical and numerical solutions of the fractional microbiological densities model in bacteria cell as a result of diffusion mechanisms. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;136:109824. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranjan R., Prasad H.S. A fitted finite difference scheme for solving singularly perturbed two point boundary value problems. Inf Sci Lett. 2020;9(2):65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brauer F. Mathematical epidemiology: past, present, and future. Infect Dis Model. 2017;2(2):113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.En’Ko P.D. On the course of epidemics of some infectious diseases. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(4):749–755. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadhoud A.R. Quintic non-polynomial spline method for solving the time fractional biharmonic equation. Appl Math Inf Sci. 2019;13:507–513. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ereu J., Gimenez J., Perez L. On solutions of nonlinear integral equations in the space of functions of Shiba-bounded variation. Appl Math Inf Sci. 2020;14:393–404. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castillo-Chavez C. Science & Business Media; Springer Verlag: 2002. Mathematical approaches for emerging and reemerging infectious diseases: an introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar D., et al. A new fractional SIRS-SI malaria disease model with application of vaccines, antimalarial drugs, and spraying. Adv Differ Equ. 2019;2019(1):278. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y., Guo D. Molecular mechanisms of coronavirus RNA capping and methylation. Virol Sin. 2016;31(1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s12250-016-3726-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman G., Shah K., Haq F., Ahmad N. Host vector dynamics of pine wilt disease model with convex incidence rate. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2018;113:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaikh A.S., Shaikh I.N., Nisar K.S. A mathematical model of COVID-19 using fractional derivative: outbreak in India with dynamics of transmission and control. Adv Differ Equ. 2020;2020:373. doi: 10.1186/s13662-020-02834-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan M.A., Atangana A. Modeling the dynamics of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) with fractional derivative. Alex Eng J. 2020;59:2379–2389. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ndairou F., Area I., Nieto J.J., Torres D.F. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 transmission dynamics with a case study of Wuhan. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109846. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan A., Liu L., Wang C., Guo H., Hao X., Wang Q., et al. A conceptual model for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Wuhan, China with individual reaction and governmental action. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdo M.S., Shah K., Wahash H.A., Panchal S.K. On a comprehensive model of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) under Mittag-Leffler derivative. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109867. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yousaf M., Zahir S., Riaz M., Hussain S.M., Shah K. Statistical analysis of forecasting COVID-19 for upcoming month in Pakistan. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;138:109926. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atangana A. Modelling the spread of COVID-19 with new fractal-fractional operators: can the lockdown save mankind before vaccination? Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;136:109860. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van den Driessche P., Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math Biosci. 2002;180(1–2):29–48. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castillo-Chavez C., Song B. Dynamical models of tuberculosis and their applications. Math Biosci Eng. 2004;1(2):361. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2004.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdo M.S., Shah K., Wahash H.A., Panchal S.K. On a comprehensive model of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) under Mittag-Leffler derivative. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135:109867. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharomi O., Podder C.N., Gumel A.B., Elbasha E.H., Watmough J. Role of incidence function in vaccine-induced backward bifurcation in some HIV models. Math Biosci. 2007;210(2):436–463. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ndairou F., Area I., Nieto J.J., Torres D.F. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 transmission dynamics with a case study of Wuhan. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;138:109846. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qianying L. A conceptual model for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Wuhan, China with individual reaction and governmental action. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iqbal Z., Ahmed N., Baleanu D., Adel W., Rafiq M., MAU R., et al. Positivity and boundedness preserving numerical algorithm for the solution of fractional nonlinear epidemic model of HIV/AIDS transmission. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;134:109706. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srivastava V.K., Kumar S., Awasthi M.K., Singh B.K. Two-dimensional time fractional-order biological population model and its analytical solution. Egypt J Basic Appl Sci. 2014;1(1):71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srivastava V.K., Awasthi M.K., Kumar S. Numerical approximation for HIV infection of CD4+ t cells mathematical model. Ain Shams Eng J. 2014;5(2):625–629. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar S., Kumar R., Singh J., Nisar K.S., Kumar D. An efficient numerical scheme for fractional model of HIV-1 infection of CD4+ t-cells with the effect of antiviral drug therapy. Alex Eng J. 2020;59(4):2053–2064. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar S., Kumar R., Agarwal R.P., Samet B. A study of fractional Lotka-Volterra population model using haar wavelet and Adams-Bashforth-Moulton methods. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2020;43(8):5564–5578. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sajjadi S.S., Baleanu D., Jajarmi A., Pirouz H.M. A new adaptive synchronization and hyperchaos control of a biological snap oscillator. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;138:109919. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jajarmi A., Baleanu D. A new iterative method for the numerical solution of high-order non-linear fractional boundary value problems. Front Phys. 2020;8:220. [Google Scholar]