Abstract

Tanshinones, the major bioactive components in Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen), are synthesized via the mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway or the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway and the downstream biosynthesis pathway. In this study, the bacterial component lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was utilized as a novel elicitor to induce the wild type hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. HPLC analysis revealed that LPS treatment resulted in a significant accumulation of cryptotanshinone (CT) and dihydrotanshinone I (DTI). qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that biosynthesis genes such as SmAACT and SmHMGS from the MVA pathway, SmDXS and SmHDR from the MEP pathway, and SmCPS, SmKSL and SmCYP76AH1 from the downstream pathway were markedly upregulated by LPS in a time-dependent manner. Furthermore, transcription factors SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2, which can activate the expression of SmDXR, SmDXS and SmCPS, were also increased by LPS. Since Ca2+ signaling is essential for the LPS-triggered immune response, Ca2+ channel blocker LaCl3 and CaM antagonist W-7 were used to investigate the role of Ca2+ signaling in tanshinone biosynthesis. HPLC analysis demonstrated that both LaCl3 and W-7 diminished LPS-induced tanshinone accumulation. The downstream biosynthesis genes including SmCPS and SmCYP76AH1 were especially regulated by Ca2+ signaling. To summarize, LPS enhances tanshinone biosynthesis through SmWRKY1- and SmWRKY2-regulated pathways relying on Ca2+ signaling. Ca2+ signal transduction plays a key role in regulating tanshinone biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza.

Keywords: lipopolysaccharide, tanshinones, Ca2+ signaling, SmWRKY

1. Introduction

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, also known as danshen, is a widely used Chinese herbal medicine for treating cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [1]. The primary bioactive ingredients of S. miltiorrhiza comprises salvianolic acids and tanshinones. In these secondary metabolites, tanshinones have received extensive attention for their multiple pharmacological properties, including cardioprotective effects, antitumor activity, anti-inflammatory activity and antibacterial activity [1,2]. The valuable tanshinones consist of tanshinone I (TI), tanshinone IIA (TIIA), tanshinone IIB (TIIB), cryptotanshinone (CT), dihydrotanshinone I (DTI), etc.

In S. miltiorrhiza, tanshinone biosynthesis experiences a complicated process. Based on metabonomics and genomics research, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) have been identified as the precursors of tanshinones. These two compounds can be generated either from the mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway or the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway [2]. In the MVA pathway, two molecules of acetyl-CoA are formed to acetoacetyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase (AACT), firstly. Then, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) is synthesized through adding another acetyl-CoA by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMGS). HMG-CoA is further reduced to MVA by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR). Subsequently, MVA is catalyzed in turn by mevalonate kinase (MK), 5-phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK) and MVAPP decarboxylase (MDC) to generate key intermediate IPP. IPP can be transformed to another precursor DMAPP by isopentenyl-diphosphate deltaisomerase (IPPI). In the MEP pathway, the initial reactants pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (GA-3P) are catalyzed by 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS) to form 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP). Then, DXP is reduced to MEP catalyzed by DXP reductoisomerase (DXR). In the rest of the reactions, there are five enzymes contributing to IPP and DMAPP synthesis, including 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate cytidyl transferase (MCT), 4-(cytidine 5-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase (CMK), 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (MDS), 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate (HMBPP) synthase (HDS), and HMBPP reductase (HDR) [2,3].

In the subsequent cyclization reactions, IPP and DMAPP are transformed into ferruginol catalyzed in turn by copalyl diphosphate synthase (CPS), kaurene synthase-like (KSL) and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP76AH1). During the last stage, ferruginol is eventually transformed into different tanshinones through some undefined reactions [4].

Recently, researchers have improved the content of tanshinones in S. miltiorrhiza through various strategies, including elicitor treatment, hormone signal regulation, overexpression of key biosynthesis genes, and transcriptional regulation [3,5,6]. Nevertheless, few studies have illustrated the role of Ca2+ signaling in tanshinone biosynthesis. In plant cells, calcium acts not only as an essential nutrient, but also as a crucial second messenger. When confronted with diverse abiotic and biotic stresses, plant cells generate a cytoplasmic Ca2+ signal, which can be decoded by calcium sensors such as calmodulin (CaM), calmodulin-like proteins (CMLs), Ca2+-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), and calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs) to regulate numerous downstream metabolic reactions [7,8].

Notably, Ca2+ signaling is closely related to secondary metabolism in plants [9,10,11,12]. For instance, through binding with a Ca2+-CaM complex, transcription factor CAMTA3 promotes the production of glucosinolates, which are defensive compounds against herbivores [9,10]. The biosynthesis of salicylic acid (SA) is controlled by CaM-binding transcription factors such as CBP60g, SARD1 and CAMTA3 [11,12]. Our previous studies have shown that Ca2+ signaling is essential to the SA-induced rosmarinic acid accumulation in S. miltiorrhiza [13]. Therefore, Ca2+ signaling can act as a vital player to regulate secondary metabolite biosynthesis.

Here, we focused on the regulation of secondary metabolism by Ca2+ signaling. In this study, bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a characteristic glycolipid component of a Gram-negative bacteria cell wall and is a stimulator of pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) triggered immunity (PTI) [14,15,16], was utilized as an elicitor to treat the wild type hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. We found that LPS treatment significantly upregulated the expression of key tanshinone biosynthesis genes and enhanced the accumulation of tanshinones in hairy roots. Due to LPS-triggered PTI depending on Ca2+ signaling in plant cells [15], the Ca2+ channel blocker LaCl3 and CaM antagonist W-7 were also used to analyze the role of Ca2+ signaling in tanshinone biosynthesis. These results demonstrate that LPS enhances tanshinone biosynthesis in a Ca2+-dependent manner and suggest that Ca2+ signal transduction is essential for modulating secondary metabolism in S. miltiorrhiza.

2. Results

2.1. LPS Enhances Tanshinone Accumulation in the Wild Type Hairy Roots of S. miltiorrhiza

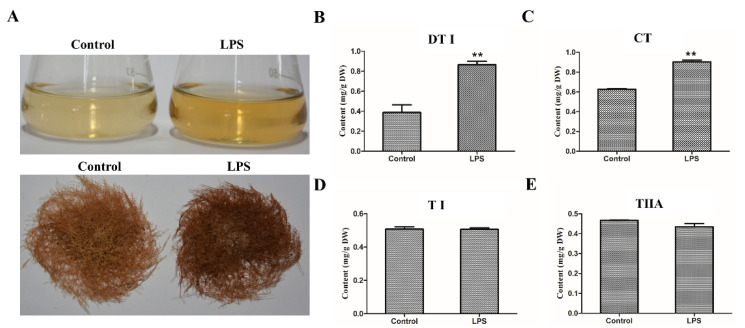

Since the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites might be induced by microorganisms, the bacterial component LPS was applied as a novel elicitor to treat the wild type (WT) hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. After being treated by 50 μg/mL LPS for 10 days, the hairy roots and the culture medium showed a deep red color, which is the characteristic color of tanshinones (Figure 1A). Compared to the control, LPS did not obviously affect the growth of hairy roots (Figure 1A). Further, the content of the tanshinones, including dihydrotanshinone I (DTI), cryptotanshinone (CT), tanshinones I (TI) and tanshinones IIA (TIIA), was analyzed by HPLC. When the hairy roots were treated by LPS, the content of DTI significantly increased from 0.38 mg/g to 0.86 mg/g in contrast to the control (Figure 1B), and the content of CT increased from 0.62 mg/g to 0.9 mg/g (Figure 1C). However, the content of TI and TIIA showed no significant change (Figure 1D,E). These results indicate that LPS can induce the accumulation of DTI and CT without markedly inhibiting the growth of S. miltiorrhiza WT hairy roots.

Figure 1.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) enhances tanshinone accumulation in the wild type (WT) hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. (A) LPS-treated WT hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. The hairy roots were treated by 50 μg/mL LPS for 10 days. H2O was used as a control. (B–E) The content of tanshinones in LPS-treated hairy roots. The content of the tanshinones was analyzed by HPLC and presented by the means ± SD. The significant differences between different groups were calculated by the Student’s t-test. (**) indicates a very significant difference (p ≤ 0.01). TI, tanshinone I; TIIA, tanshinone IIA; CT, cryptotanshinone; DT, dihydrotanshinone.

2.2. LPS Upregulates Key Gene’s Expression in Tanshinone Biosynthesis Pathways

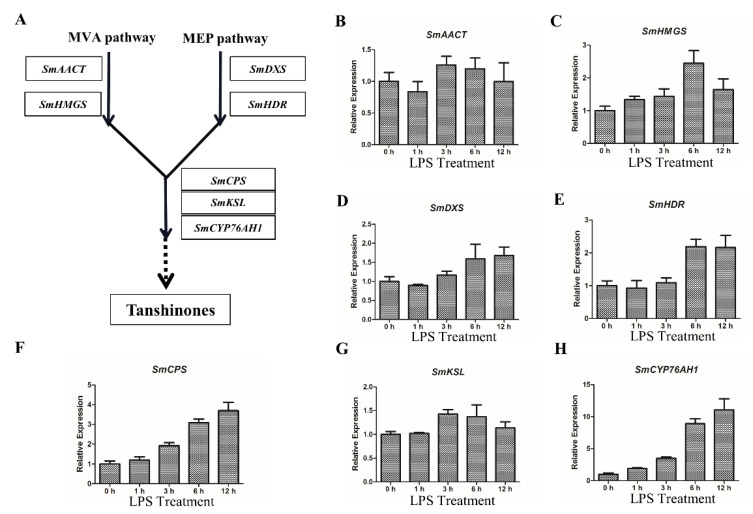

To elucidate the regulation mechanism of LPS, the key biosynthesis genes of tanshinones were analyzed by qRT-PCR. In the biosynthesis pathways of tanshinones, SmAACT and SmHMGS are from the MVA pathway, and SmDXS and SmHDR are from the MEP pathway (Figure 2A). After being induced by LPS, the transcripts levels of SmAACT and SmHMGS were obviously upregulated at 6 h (Figure 2B,C). Similarly, SmDXS and SmHDR showed the same response to LPS treatment (Figure 2D,E). In the confirmed biosynthesis pathway of tanshinones, SmCPS, SmKSL and SmCYP76AH1 are located downstream the MVA and MEP pathways (Figure 2A). Notably, the expression of these three genes also increased along with LPS treatment (Figure 2F–H). SmCPS and SmCYP76AH1 were especially upregulated by LPS in a time-dependent manner (Figure 2F,H).

Figure 2.

LPS upregulates the expression of key tanshinone biosynthesis genes in the WT hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. (A) The biosynthesis pathways of tanshinones in S. miltiorrhiza. (B,C) The relative expression levels of key genes in the MVA pathway. The transcript levels of SmAACT and SmHMGS were analyzed by qRT-PCR using SmACT for normalization. (D,E) The relative expression levels of key genes in the MEP pathway. The transcript levels of SmDXS and SmHDR were analyzed by qRT-PCR using SmACT for normalization. (F–H) The relative expression levels of key downstream genes in tanshinone biosynthesis. The transcripts levels of SmCPS, SmKSL and SmCYP76AH1 were analyzed by qRT-PCR using SmACT for normalization. (B–H) The hairy roots were treated by 50 μg/mL LPS in a time gradient. The gene’s expression level of 0 h was set to 1. The expression value of genes is shown as the means ± SD.

To further explore the stimulation mechanism of these biosynthesis genes by LPS, the expression of transcription factors SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. In S. miltiorrhiza, SmWRKY1 can bind with the promoter of SmDXR, and SmWRKY2 can bind with SmDXS and SmCPS, to positively regulate tanshinone biosynthesis [5,17,18]. Our further analysis indicated that LPS upregulated the transcript levels of SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 in the same time-dependent manner. The expression of these transcription factors responded to LPS and reached a peak at 6 h (Figure 3A,B). Hence, SmDXS, SmCPS and SmDXR can be highly transcribed due to the activation of SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2.

Figure 3.

LPS upregulates the expression of SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 in the WT hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. (A,B) The relative expression levels of SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 were analyzed by qRT-PCR using SmACT for normalization. The hairy roots were treated by 50 μg/mL LPS in a time gradient. The gene’s expression level of 0 h was set to 1. The expression value of genes is shown as the means ± SD.

Taken together, the secondary metabolite tanshinones can be induced by the immune regulator LPS. LPS enhances tanshinone accumulation through stimulating SmWRKY1- and SmWRKY2-regulated gene expression in tanshinone biosynthesis pathways.

2.3. Ca2+ Inhibitors Affect Tanshinone Accumulation

Ca2+ signal transduction is essential for the LPS-triggered plant immune response [15]. Thus, three Ca2+ signal inhibitors, including Ca2+ channel blocker LaCl3, CaM antagonist W-7 and Ca2+ chelator EGTA, were applied to analyze the role of Ca2+ signaling in tanshinone biosynthesis [15,19]. Since tanshinones can generate a deep red color in the roots of S. miltiorrhiza, we preliminarily observed the color of the hairy roots treated by different Ca2+ reagents. As shown in Figure 4A,B, the hairy roots treated by 1 mmol/L LaCl3 apparently showed a light color compared to the H2O control. Similarly, 100 μmol/L W-7 also led to light color in contrast to the DMSO control. Nevertheless, 1mmol/L EGTA did not obviously affect the color of the hairy roots compared to the H2O control. These results suggest that Ca2+ signaling is closely associated with tanshinone biosynthesis. The accumulation of tanshinones might be inhibited by blocking Ca2+ influx or repressing CaM-mediated signaling in the hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza.

Figure 4.

Ca2+ inhibitors affect tanshinone accumulation in the WT hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. (A) The culture medium of different treated hairy roots. (B) The different treated hairy roots. (A,B) The hairy roots were treated by 1 mmol/L LaCl3, 100 μmol/L W-7 and 1mmol/L EGTA for 10 days, respectively. H2O was the control of LaCl3 and EGTA. DMSO was the control of W-7.

2.4. Ca2+ Channel Blocker Inhibits LPS-Induced Tanshinone Accumulation

LaCl3 is capable of suppressing cytoplasmic Ca2+ elevation via blocking Ca2+ influx [15,19]. Thus, LaCl3 was synergistically utilized with LPS to analyze the role of Ca2+ signaling in tanshinone biosynthesis. As shown in Figure 5A, the LPS-treated hairy roots showed the deepest color and LaCl3 treatment resulted in the lightest color. LPS-induced deep red was apparently decreased by LaCl3 synergetic treatment (Figure 5A). Further, the content of tanshinones was examined by HPLC. Compared to the LPS treatment, the content of DTI in the LaCl3+LPS-treated sample significantly reduced from 0.71 mg/g to 0.28 mg/g, and CT reduced from 0.88 mg/g to 0.63 mg/g (Figure 5B,C). The LPS+LaCl3 treatment also led to a significant reduction in TI and TIIA in a similar way (Figure 5D,E). These results confirmed that with the inhibition of Ca2+ influx by LaCl3, LPS-induced tanshinone accumulation was accordingly diminished. Therefore, the Ca2+ influx signal is involved in regulating tanshinone accumulation.

Figure 5.

LaCl3 affects tanshinone accumulation in the WT hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. (A) The cultures of treated hairy roots. The WT hairy roots were treated by 50 μg/mL LPS, 1 mmol/L LaCl3 and 50 μg/mL LPS + 1 mmol/L LaCl3 for 10 days. H2O was used as a control. (B–E) The content of tanshinones in treated hairy roots. The content of tanshinones in H2O, LPS, LaCl3 and LPS+LaCl3 treated hairy roots was analyzed by HPLC. The bars are shown as the means ± SD. The significant differences between different groups were calculated by the Student’s t-test. (**) indicates a very significant difference (p ≤ 0.01).

2.5. CaM Antagonist Inhibits LPS-Induced Tanshinone Accumulation

CaM serves as a crucial sensor in Ca2+ signal transduction. Through binding with Ca2+, the Ca2+-CaM complex interacts with target proteins such as CNGC, CDPK, and MAPK to regulate numerous metabolism reactions [8,20]. Hence, the CaM antagonist W-7 was utilized to corporately treat hairy roots with LPS. As shown in Figure 6A, W-7 treatment partly decreased the LPS-induced deep red of the hairy roots and generated the lightest color, while showing no obvious growth inhibition. Compared to LPS treatment, the content of DTI, CT and TI significantly declined from 0.52 mg/g to 0.23 mg/g, 1.15 mg/g to 0.52 mg/g, and 0.29 mg/g to 0.20 mg/g in LPS+W-7 treated hairy roots (Figure 6B–D). Notably, the separate W-7 treatment resulted in extreme inhibition of these four tanshinones, especially CT and TI (Figure 6B–E). Taken together, CaM-mediated signaling is essential for LPS-induced tanshinone accumulation in S. miltiorrhiza hairy roots.

Figure 6.

W-7 affects tanshinone accumulation in the WT hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. (A) The cultures of treated hairy roots. The WT hairy roots were treated by 50 μg/mL LPS, 100 μmol/L W-7 and 50 μg/mL LPS + 100 μmol/L W-7 for 10 days, DMSO was used as a control. (B–E) The content of tanshinones in treated hairy roots. The content of tanshinones in DMSO, LPS, W-7 and LPS+W-7 treated hairy roots was analyzed by HPLC. The bars are shown as the means ± SD. The significant differences between different groups were calculated by the Student’s t-test. (**) indicates a very significant difference (p ≤ 0.01).

2.6. LPS Induces the Expression of Key Tanshinone Biosynthesis Genes in a Ca2+-Dependent Manner

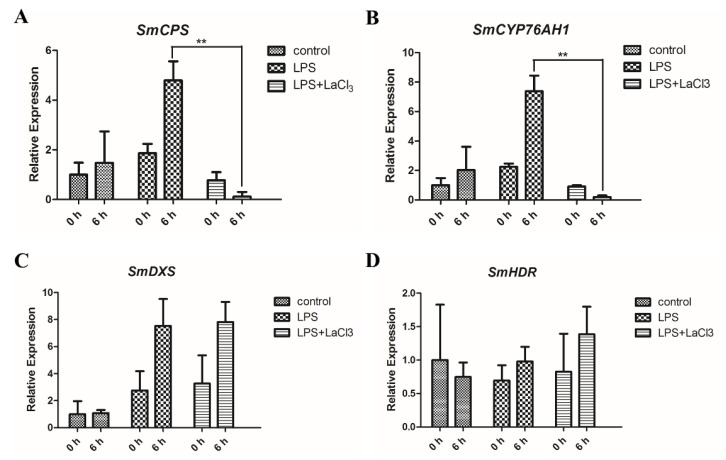

To further investigate the role of Ca2+ signaling in tanshinone biosynthesis, the expression levels of key genes in LPS and LaCl3 treated WT hairy roots were analyzed by qRT-PCR. When synergistically treated by LaCl3 and LPS for 6 h, the expression levels of SmCPS and SmCYP76AH1 reduced approximately 40-fold and 37-fold, respectively, compared to the LPS separate treatment (Figure 7A,B). However, SmHDR and SmDXS did not show apparent reduction by LaCl3+LPS treatment (Figure 7C,D). Comparatively, LaCl3 preferentially inhibits the downstream genes (SmCPS and SmCYP76AH1) in tanshinone biosynthesis pathways. This suggests that the downstream genes of the tanshinone biosynthesis pathway are more likely to be regulated by Ca2+ signaling than the MEP pathway genes.

Figure 7.

LaCl3 regulates the expression of downstream tanshinone biosynthesis genes. (A,B) The expression of SmCPS and SmCYP76AH1 in treated hairy roots. The WT hairy roots were treated by 50 μg/mL LPS and 50 μg/mL LPS + 1 mmol/L LaCl3 for 6 h. H2O was used as a control. SmCPS and SmCYP76AH1 were analyzed by qRT-PCR using SmACT for normalization. The expression value of genes is shown as the means ± SD. (C,D) The expression of SmDXS and SmHDR in treated hairy roots. The expression of SmDXS and SmHDR were analyzed by qRT-PCR using SmACT for normalization. (A–D) The gene’s expression level of 0 h was set to 1. The expression value of genes is shown as the means ± SD. The significant differences between different groups were calculated by the Student’s t-test. (**) indicates a very significant difference (p ≤ 0.01).

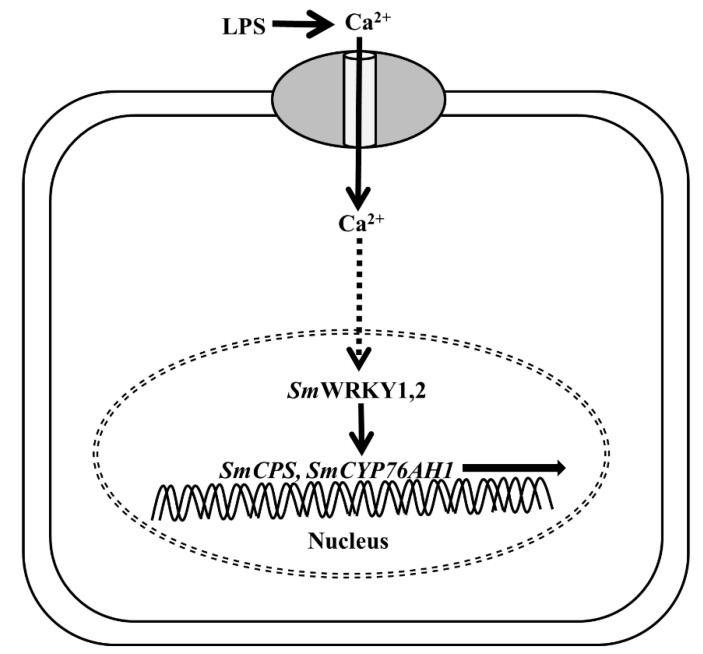

Therefore, we present the mechanism of LPS-induced tanshinone biosynthesis in Figure 8. Firstly, LPS induces the generation of Ca2+ signaling in the cytoplasm, which is accordingly decoded by the Ca2+-dependent regulators. Then, SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 are upregulated and activated by some undefined Ca2+-dependent regulators. Eventually, the key biosynthesis genes of tanshinones such as SmCPS, SmDXS, SmDXR and SmCYP76AH1 are transcribed in a high level that in turn synthesizes the tanshinones in the hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza.

Figure 8.

The diagram of LPS-induced tanshinone biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza. LPS induces tanshinone biosynthesis in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Firstly, LPS treatment leads to a Ca2+ elevation signal in the cytoplasm. Then, the transcription factors SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 are activated by some undetermined Ca2+-related regulators. Finally, key tanshinone biosynthesis genes are upregulated by SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 resulting in tanshinone accumulation in hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza.

3. Discussion

The dry roots of S. miltiorrhiza (Danshen) have been used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) since 200–300AD [2]. Because of slow growth and a low content of bioactive components, the wild resources of S. miltiorrhiza cannot meet the growing requirements from pharmaceutical markets. Therefore, improving the content of pharmacological ingredients is the main purpose of metabolic research. Up to now, many approaches have been applied to enhance the content of phenolic acids and tanshinones in S. miltiorrhiza [21]. In this study, the bacterial component lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was utilized as a novel elicitor to induce the wild type hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza. According to the biosynthesis pathway of tanshinones, cryptotanshinone (CT) is the first tanshinone to be generated, and then tanshinone IIA (TIIA), tanshinone IIB (TIIB), tanshinone I (TI), and dihydrotanshinone I (DTI) [3,22]. We have found that LPS significantly enhances the accumulation of tanshinones CT and DTI. Furthermore, the gene expression analysis has shown that key genes from the MVA pathway (SmAACT, SmHMGS), the MEP pathway (SmDXS, smHDR) and the downstream biosynthesis pathway (SmCPS, SmKSL, SmCYP76AH1) respond to LPS treatment in a time-dependent manner. These results demonstrate that LPS is capable of activating key genes’ expression in the tanshinone biosynthesis process. It is worth noting that LPS does not obviously inhibit the growth of hairy roots. Thus, LPS can be applied as a positive elicitor to enhance the content of tanshinones without affecting the growth of the S. miltiorrhiza hairy roots. This is valuable for increasing the content of metabolites.

In S. miltiorrhiza, researchers have promoted the content of tanshinones via pathway engineering such as SmGGPPS-SmDXS2 [23], SmHMGR-SmDXR [24]; or overexpression of key transcription factors including SmMYB98 [25], SmMYB36 [26], SmWRKY1 [17], SmWRKY2 [5], and SmbHLH3 [6]. Previous studies have confirmed that SmDXS2 and SmCPS are the target genes of SmWRKY2 [5], and SmDXR is the target of SmWRKY1 [17]. Our results have further shown that SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 were upregulated by LPS in the same manner as SmCPS, SmDXS2, SmCYP76AH1, etc. Therefore, we deduce that LPS promotes tanshinone biosynthesis through activating the SmWRKY1,2-SmCPS, SmDXS2, SmDXR pathway. In plants, WRKY transcription factors act as a key regulator in response to diverse abiotic and biotic stresses [18,27], including PAMP triggered immunity (PTI) [28,29]. WRKYs can interact with Ca2+-related regulators to regulate immune reactions, such as CPK and calmodulin [30,31,32,33]. These suggest that tanshinone metabolism is closely related with Ca2+ signaling and might be regulated in a similar way by immunity responding reactions.

The bacterial component LPS is an immune activator. It is capable of inducing cytoplasm Ca2+ elevation, which is essential for the plant innate immune response [15,34]. To analyze the role of Ca2+ signaling in tanshinone biosynthesis, S. miltiorrhiza hairy roots were collaboratively treated by LPS and Ca2+ inhibitors. Both Ca2+ channel blocker LaCl3 and CaM antagonist W-7 can significantly inhibit the accumulation of tanshinones. Further analysis has shown that the downstream biosynthetic genes (SmCPS, SmCYP76AH1) are presumably regulated by Ca2+ signaling in priority. Based on these data, we present the pathway of LPS-induced tanshinone biosynthesis as Ca2+ signal-Ca2+-dependent regulators-SmWRKY1,2-downstream genes axis in S. miltiorrhiza. Our study provides a new insight into the essential role of Ca2+ signaling in tanshinone biosynthesis. However, the exact mechanism of how SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 are modulated by Ca2+-dependent regulators remains unresolved. In the future, searching for the Ca2+-dependent master regulators, which are capable of activating SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2, might be the key to uncovering the mechanism of Ca2+-mediated tanshinone biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza. For the purpose of promoting the content of valuable metabolites, the Ca2+ transduction pathway might be the potential regulation target.

Based on our findings, the LPS-induced Ca2+ signal is highly associated with ion influx sourced from apoplast. In plant tissues, the arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs), negatively charged and anchored to the extracellular side of the plasma membrane, can reversibly bind with Ca2+ and hypothetically serve as the calcium capacitor [35]. Triggered by a low pH related to plasma membrane (PM) H+-ATPases, the AGPs-Ca2+ complex can release free Ca2+ into the cell-surface apoplast and in turn lead to [Ca2+]cyt signal generation [35]. In recent in-depth research, knockouts of the key β-glucuronosyltransferases (GlcATs), which are responsible for adding glucuronic acid (GlcA) to AGPs, resulted in reduced AGPs glucuronidation, impaired Ca2+ signaling and consequent deficient plant development [36,37]. This AGPs-Ca2+ interaction model highlights the crucial role of the proton pump in modulating Ca2+ signaling. The post-translational regulation, especially phosphorylation, is central to alternating PM H+-ATPases between the auto-inhibited state and active state [38]. For instance, fusicoccin, the secreta of fungi Fusicoccum amygdali, is able to activate plant PM H+-ATPases by increasing the phosphorylation level [38,39]. Notably, LPS-induced phosphorylation of key proteins such as AMPK [40], p53 [41] and mTOR [42], has been proved by massive studies in animals. In plants, LPS might similarly regulate phosphorylation of crucial proteins and might be a potential activator of PM H+-ATPases. Thus, we further hypothesize that LPS induces Ca2+ influx via the regulation of PM H+-ATPases. The phosphorylation modification of PM H+-ATPases could be the key to uncover LPS-generated Ca2+ influx in S. miltiorrhiza.

In addition, in comparison with the elaborated studies in animals, LPS-regulated pathways in plants are still elusive. Up to date, several proteins including AtLBR1,2 (LPS binding protein) and OsCERK1 (LysM-type receptor-like kinase) have been determined as the key players in LPS-induced immune responses [43,44]. However, the potential correlations between these LPS-related regulators and secondary metabolism have not been deeply elucidated. Consequently, the regulatory network of LPS in plants still needs to be illuminated by more comprehensive research in the future.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Lipopolysaccharides (L9143) and LaCl3 (449830) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and were dissolved in sterile water. W-7 (N-(6-Aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulfonamide Hydrochloride) (N136431) was from Aladdin (Shanghai, China) and was dissolved in DMSO. The SteadyPure Plant RNA Extraction Kit (AG21019), the Evo M-MLV RT Kit with gDNA Clean for qPCR (AG11601), and the SYBR® Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (AG11701) were from Accurate Biotechnology(Changsha, China). Acetonitrile and methyl alcohol for HPLC analysis were from TEDIA (Fairfield, OH, USA). The standards of DT, CT, TI and TIIA were from Herbpurify (Chengdu, China).

4.2. Hairy Roots Culture and Treatment

The S. miltiorrhiza wild type (WT) hairy roots were generated by Agrobacterium rhizogenes (ATCC15834). The generation and culture of hairy roots were based on previous research [45]. Before analysis, hairy roots weighing 0.3 g were cultured in 50 mL 6, 7-V liquid medium [46] containing an amount of 30 g/L sucrose for 21 days at 25 °C. LPS and other reagents were added into the culturing medium on the 10th day, and then the hairy roots were harvested on the 21st day. The hairy roots were dried at 45 °C for 4 days before HPLC analysis.

4.3. Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

To investigate the expression of key biosynthesis genes, the WT hairy roots were treated by 50 μg/mL LPS in a time gradient, and the 0 h treatment was used as a control. The total RNAs of the control and LPS-treated hairy roots were extracted by a SteadyPure Plant RNA Extraction Kit (AG21019). Total RNA (1 μg) was reversely transcribed by an Evo M-MLV RT Kit (with gDNA Clean) (AG11601). The gene expression was analyzed by a SYBR® Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (AG11701). qRT-PCR was conducted on a real-time PCR system (Bio-RAD CFX96, Hercules, CA, USA). SmACT was used as a reference gene. The relative expression level of a gene was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. The gene’s expression level of 0 h was set to 1. Gene-specific primers were shown in the Appendix A Table A1.

To investigate the regulation of Ca2+ signaling in gene expression, the WT hairy roots were treated by 50 μg/mL LPS and 50 μg/mL LPS + 1 mmol/L LaCl3 for 6 h, and H2O was used as a control. The total RNAs of the control and the different treated hairy roots were extracted, reversely transcribed and analyzed by qRT-PCR, as mentioned above. The gene’s expression level of control at 0 h was set to 1.

4.4. HPLC Analysis

The dried hairy roots powder (0.02 g) was extracted by 70% methyl alcohol (4 mL) overnight and treated by ultrasonic for 45 min. Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane before HPLC analysis. The content of DTI, CT, TI and TIIA was determined by the Waters 1525/2489 HPLC system (Milford, MA, USA) equipped with an InertSustain® C18 column (5 um, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, SHIMADZU-GL, Tokyo, Japan).

The HPLC operation software was Empower 2. The detection wavelength for tanshinones was 270 nm. Elution gradients are as follows (A: acetonitrile; B: 0.02% phosphoric acid solution): 0–10 min, 5–20% A; 10–15 min, 20–22% A; 15–20 min, 22–25% A; 20–28 min, 25–30% A; 28–40 min, 30–35% A; 40–45 min, 35–45% A; 45–50 min, 45–50% A; 50–58 min, 50–58% A; 58–67 min, 58–50% A; 67–70 min, 50–60% A; 70–80 min, 60–70% A; 80–85 min, 70–100% A; 85–95 min, 100–5% A. The column temperature was set at 30 °C. The flow rate was set as 1 mL/min.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted over three times. The results were described as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The significant differences between different groups were calculated by the Student’s t-test. (*) indicates a significant difference (0.01 < p < 0.05). (**) indicates a very significant difference (p ≤ 0.01).

5. Conclusions

On the basis of the data in this study, we proposed the model of LPS-enhanced tanshinone biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza. Firstly, LPS induces a cytoplasmic Ca2+ signal which consequently activates the expression of the transcription factors SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2 via some undefined Ca2+ sensors. Then, the key biosynthesis genes of tanshinones are upregulated by SmWRKY1 and SmWRKY2. To summarize, the Ca2+ signal-Ca2+-dependent regulators-SmWRKY1,2-downstream genes axis might be central to regulate tanshinone biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Huifang Duan for revising the language.

Abbreviations

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| TI | tanshinone I |

| TIIA | tanshinone IIA |

| TIIB | tanshinone IIB |

| CT | cryptotanshinone |

| DTI | dihydrotanshinone I |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Primers for qRT-PCR.

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| SmACT-F | GGTGCCCTGAGGTCCTGTT |

| SmACT-R | AGGAACCACCGATCCAGACA |

| SmAACT1-F | TGAAGGACGGACTCTGGGATGT |

| SmAACT1-R | CCTTGTCAACAATGGTGGATGG |

| SmCPS1-F | CCACATCGCCTTCAGGGAAGAAAT |

| SmCPS1-R | TTTATGCTCGATTTCGCTGCGATCT |

| SmCYP76AH1-F | ACGCATCACTTCACCCATCTCA |

| SmCYP76AH1-R | ATTGCCGACTCATCCACGAT |

| SmDXS2-F | CTCACGGTCGCATTGCATCAT |

| SmDXS2-R | CGCTTTCGTCTCGTTTAGGGA |

| SmHDR1-F | GGATTTGACCCGGACAAGGAT |

| SmHDR1-R | CCGCCAATGACTAGGATGAGA |

| SmHMGS1-F | TTAGGGCGAATCACATGGCTCA |

| SmHMGS1-R | TCGGCATCCAAGATCGAGAAC |

| SmKSL1-F | TGGAAACAGTGTGACCCTTCTGCT |

| SmKSL1-R | GCTTGCATACAAATAACACCCAATCCT |

| SmWRKY1-F | ACCTACAACGGCCAACACACT |

| SmWRKY1-R | TCGTCCGGTGTTTTCATTTG |

| SmWRKY2-F | ACTCATCCAAGCTGTCCGGT |

| SmWRKY2-R | ATTCATTGTTCCGTTTGAGCC |

Author Contributions

B.Z. and J.D. designed the work. B.Z., X.L. (Xueying Li), X.L. (Xiuhong Li), Z.L., X.C., Q.O.Y. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. B.Z. prepared the manuscript. J.D. and P.M. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31670301) and the College Students’ Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Plan Program (202010712106; S202010712368).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ren J., Fu L., Nile S.H., Zhang J., Kai G. Salvia miltiorrhiza in Treating Cardiovascular Diseases: A Review on Its Pharmacological and Clinical Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:753. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang Z., Gao W., Huang L. Tanshinones, Critical Pharmacological Components in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:202. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao W., Sun H.X., Xiao H., Cui G., Hillwig M.L., Jackson A., Wang X., Shen Y., Zhao N., Zhang L., et al. Combining metabolomics and transcriptomics to characterize tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. BMC Genom. 2014;15:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Z., Peters R.J., Weirather J., Luo H., Liao B., Zhang X., Zhu Y., Ji A., Zhang B., Hu S., et al. Full-length transcriptome sequences and splice variants obtained by a combination of sequencing platforms applied to different root tissues of Salvia miltiorrhiza and tanshinone biosynthesis. Plant J. 2015;82:951–961. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng C., Hao X., Shi M., Fu R., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Zhou W., Feng Y., Makunga N.P., Kai G. Tanshinone production could be increased by the expression of SmWRKY2 in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Plant Sci. 2019;284:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang C., Xing B., Yang D., Ren M., Guo H., Yang S., Liang Z. SmbHLH3 acts as a transcription repressor for both phenolic acids and tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Phytochemistry. 2020;169:112183. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bredow M., Monaghan J. Regulation of Plant Immune Signaling by Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinases. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2019;32:6–19. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-18-0267-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aldon D., Mbengue M., Mazars C., Galaud J.P. Calcium Signalling in Plant Biotic Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:665. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nie H., Zhao C., Wu G., Wu Y., Chen Y., Tang D. SR1, a calmodulin-binding transcription factor, modulates plant defense and ethylene-induced senescence by directly regulating NDR1 and EIN3. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:1847–1859. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.192310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu Y., Xi J., Du L., Suttle J.C., Poovaiah B.W. Coupling calcium/calmodulin-mediated signaling and herbivore-induced plant response through calmodulin-binding transcription factor AtSR1/CAMTA3. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;79:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9896-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du L., Ali G.S., Simons K.A., Hou J., Yang T., Reddy A.S., Poovaiah B.W. Ca2+/calmodulin regulates salicylic-acid-mediated plant immunity. Nature. 2009;457:1154–1158. doi: 10.1038/nature07612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L., Tsuda K., Truman W., Sato M., Nguyen le V., Katagiri F., Glazebrook J. CBP60g and SARD1 play partially redundant critical roles in salicylic acid signaling. Plant J. 2011;67:1029–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo H., Zhu N., Deyholos M.K., Liu J., Zhang X., Dong J. Calcium mobilization in salicylic acid-induced Salvia miltiorrhiza cell cultures and its effect on the accumulation of rosmarinic acid. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015;175:2689–2702. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutschera A., Ranf S. The multifaceted functions of lipopolysaccharide in plant-bacteria interactions. Biochimie. 2019;159:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2018.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali R., Ma W., Lemtiri-Chlieh F., Tsaltas D., Leng Q., von Bodman S., Berkowitz G.A. Death don’t have no mercy and neither does calcium: Arabidopsis CYCLIC NUCLEOTIDE GATED CHANNEL2 and innate immunity. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1081–1095. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman M.A., Dow J.M., Molinaro A., Parrilli M. Priming, induction and modulation of plant defence responses by bacterial lipopolysaccharides. J. Endotoxin Res. 2007;13:69–84. doi: 10.1177/0968051907079399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao W., Wang Y., Shi M., Hao X., Zhao W., Wang Y., Ren J., Kai G. Transcription Factor SmWRKY1 Positively Promotes the Biosynthesis of Tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:554. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu H., Guo W., Yang D., Hou Z., Liang Z. Transcriptional Profiles of SmWRKY Family Genes and Their Putative Roles in the Biosynthesis of Tanshinone and Phenolic Acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1593. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao C., Zheng Y., Guo Y. MYB30 transcription factor regulates oxidative and heat stress responses through ANNEXIN-mediated cytosolic calcium signaling in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2017;216:163–177. doi: 10.1111/nph.14679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yip Delormel T., Boudsocq M. Properties and functions of calcium-dependent protein kinases and their relatives in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2019;224:585–604. doi: 10.1111/nph.16088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi M., Liao P., Nile S.H., Georgiev M.I., Kai G. Biotechnological Exploration of Transformed Root Culture for Value-Added Products. Trends Biotechnol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma X.H., Ma Y., Tang J.F., He Y.L., Liu Y.C., Ma X.J., Shen Y., Cui G.H., Lin H.X., Rong Q.X., et al. The Biosynthetic Pathways of Tanshinones and Phenolic Acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Molecules. 2015;20:16235–16254. doi: 10.3390/molecules200916235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi M., Luo X., Ju G., Yu X., Hao X., Huang Q., Xiao J., Cui L., Kai G. Increased accumulation of the cardio-cerebrovascular disease treatment drug tanshinone in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots by the enzymes 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase and 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2014;14:603–615. doi: 10.1007/s10142-014-0385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi M., Luo X., Ju G., Li L., Huang S., Zhang T., Wang H., Kai G. HMGR-GGPPS Enhanced Diterpene Tanshinone Accumulation and Bioactivity of Transgenic Salvia miltiorrhiza Hairy Roots by Pathway Engineering. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;64:2523–2530. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hao X., Pu Z., Cao G., You D., Zhou Y., Deng C., Shi M., Nile S.H., Wang Y., Zhou W., et al. Tanshinone and salvianolic acid biosynthesis are regulated by SmMYB98 in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. J. Adv. Res. 2020;23:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding K., Pei T., Bai Z., Jia Y., Ma P., Liang Z. SmMYB36, a Novel R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor, Enhances Tanshinone Accumulation and Decreases Phenolic Acid Content in Salvia miltiorrhiza Hairy Roots. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5104. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04909-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amorim L.L.B., da Fonseca Dos Santos R., Neto J.P.B., Guida-Santos M., Crovella S., Benko-Iseppon A.M. Transcription Factors Involved in Plant Resistance to Pathogens. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2017;18:335–351. doi: 10.2174/1389203717666160619185308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bai Y., Sunarti S., Kissoudis C., Visser R.G.F., van der Linden C.G. The Role of Tomato WRKY Genes in Plant Responses to Combined Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:801. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Y., Guo H., Hu L., Martinez P.P., Moschou P.N., Cevik V., Ding P., Duxbury Z., Sarris P.F., Jones J.D.G. Distinct modes of derepression of an Arabidopsis immune receptor complex by two different bacterial effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:10218–10227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811858115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei W., Liang D.W., Bian X.H., Shen M., Xiao J.H., Zhang W.K., Ma B., Lin Q., Lv J., Chen X., et al. GmWRKY54 improves drought tolerance through activating genes in abscisic acid and Ca2+ signaling pathways in transgenic soybean. Plant J. 2019;100:384–398. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan C., Fan M., Yang M., Zhao J., Zhang W., Su Y., Xiao L., Deng H., Xie D. Injury Activates Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Phosphorylation of JAV1-JAZ8-WRKY51 Complex for Jasmonate Biosynthesis. Mol. Cell. 2018;70:136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui X., Zhao P., Liang W., Cheng Q., Mu B., Niu F., Yan J., Liu C., Xie H., Kav N.N.V., et al. A Rapeseed WRKY Transcription Factor Phosphorylated by CPK Modulates Cell Death and Leaf Senescence by Regulating the Expression of ROS and SA-Synthesis-Related Genes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020;68:7348–7359. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c02500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park C.Y., Lee J.H., Yoo J.H., Moon B.C., Choi M.S., Kang Y.H., Lee S.M., Kim H.S., Kang K.Y., Chung W.S., et al. WRKY group IId transcription factors interact with calmodulin. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1545–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun S.G., Meyer A., Holst O., Pühler A., Niehaus K. Characterization of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris lipopolysaccharide substructures essential for elicitation of an oxidative burst in tobacco cells. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18:674–681. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamport D.T., Várnai P. Periplasmic arabinogalactan glycoproteins act as a calcium capacitor that regulates plant growth and development. New Phytol. 2013;197:58–64. doi: 10.1111/nph.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopez-Hernandez F., Tryfona T., Rizza A., Yu X.L., Harris M.O.B., Webb A.A.R., Kotake T., Dupree P. Calcium Binding by Arabinogalactan Polysaccharides Is Important for Normal Plant Development. Plant Cell. 2020;32:3346–3369. doi: 10.1105/tpc.20.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y., Held M.A., Showalter A.M. Elucidating the roles of three beta-glucuronosyltransferases (GLCATs) acting on arabinogalactan-proteins using a CRISPR-Cas9 multiplexing approach in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:221. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02420-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falhof J., Pedersen J.T., Fuglsang A.T., Palmgren M. Plasma Membrane H+-ATPase Regulation in the Center of Plant Physiology. Mol. Plant. 2016;9:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camoni L., Visconti S., Aducci P., Marra M. From plant physiology to pharmacology: Fusicoccin leaves the leaves. Planta. 2019;249:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-3051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivas P.M.S., Vechiato F.M.V., Borges B.C., Rorato R., Antunes-Rodrigues J., Elias L.L.K. Increase in hypothalamic AMPK phosphorylation induced by prolonged exposure to LPS involves ghrelin and CB1R signaling. Horm. Behav. 2017;93:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barabutis N., Uddin M.A., Catravas J.D. Hsp90 inhibitors suppress P53 phosphorylation in LPS-induced endothelial inflammation. Cytokine. 2019;113:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei H.K., Deng Z., Jiang S.Z., Song T.X., Zhou Y.F., Peng J., Tao Y.X. Eicosapentaenoic acid abolishes inhibition of insulin-induced mTOR phosphorylation by LPS via PTP1B downregulation in skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2017;439:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Desaki Y., Kouzai Y., Ninomiya Y., Iwase R., Shimizu Y., Seko K., Molinaro A., Minami E., Shibuya N., Kaku H., et al. OsCERK1 plays a crucial role in the lipopolysaccharide-induced immune response of rice. New Phytol. 2018;217:1042–1049. doi: 10.1111/nph.14941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iizasa S., Iizasa E., Matsuzaki S., Tanaka H., Kodama Y., Watanabe K., Nagano Y. Arabidopsis LBP/BPI related-1 and -2 bind to LPS directly and regulate PR1 expression. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27527. doi: 10.1038/srep27527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu Z.B., Alfermann A.W. Diterpenoid production in hairy root cultures of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Phytochemistry. 1993;32:699–703. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veliky I.A., Martin S.M. A fermenter for plant cell suspension cultures. Can. J. Microbiol. 1970;16:223–226. doi: 10.1139/m70-041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]