Abstract

Context

Weight gain is a major driver of dissatisfaction and decreased quality of life in patients with hypothyroidism. Data on the changes in body weight following thyroidectomy are conflicting.

Objective

To perform a systematic review of the literature and a meta-analysis of weight changes following total thyroidectomy.

Data Sources

Literature search on PubMed.

Study Selection

Studies in English published between September 1998 and May 2018 reporting post-thyroidectomy weight changes.

Data extraction

Data were reviewed and compared by 3 investigators; discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Meta-analyses were performed using fixed and random effect models. Univariable and multivariable meta-regression models for weight change were implemented against study follow-up, gender, and age. Exploratory subgroup analyses were performed for indication for surgery.

Data Synthesis

Seventeen studies (3164 patients) with 23.8 ± 23.6 months follow-up were included. Severe heterogeneity across studies was observed. Using a random effect model, the estimated overall weight change was a gain of 2.13 kg, 95% confidence interval (CI; 0.95, 3.30). Age was negatively associated with weight change (β = -0.238, P < 0.001). In subgroup analyses, weight gain was more evident in patients undergoing thyroidectomy for hyperthyroidism: 5.19 kg, 95% CI (3.21, 7.17) vs goiter or malignancy 1.55 kg, 95% CI (0.82, 2.27) and 1.30 kg, 95% CI (0.45, 2.15), respectively.

Conclusions

Patients undergoing thyroidectomy experience possible mild weight gain, particularly younger individuals and those with hyperthyroidism as the indication for surgery. Prospective studies directed to assess the pathophysiology of weight gain post-thyroidectomy, and to test novel treatment modalities, are needed to better characterize post-thyroidectomy weight changes.

Keywords: thyroidectomy, hypothyroidism, weight gain, meta-analysis, levothyroxine, systematic review

Every year more than 75 000 thyroidectomies are performed in the Unites States (1). Indications include malignancy, goiter with compression symptoms, and hyperthyroidism due to toxic multinodular goiter or Graves’ disease. Currently, the majority of such procedures are performed for multinodular goiter or differentiated thyroid cancer (2); hence, patients transition acutely from a state of euthyroidism to complete reliance on exogenous thyroid hormone, most commonly delivered in the form of levothyroxine. Patients often complain of weight gain following thyroid surgery, even if the therapeutic target of thyroid hormone replacement therapy is achieved (3–12). Moreover, weight gain is a major driver of dissatisfaction and decreased quality of life in patients with hypothyroidism irrespective of the etiology (13–16). In fact, in a cross-sectional study of 244 patients with hypothyroidism, the most common symptom patients attributed to hypothyroidism was weight gain (57% of the population) (17). A realistic discussion of the potential untoward effects of surgical procedures is a critical component in the shared decision-making process model; therefore, it is important to provide estimates of weight gain following thyroidectomy based on empirical evidence to allow patients to make an informed decision. Unfortunately, little data are available on the changes in body weight following thyroidectomy, and the results are conflicting (3, 7, 12, 18). Here, we present a systematic review of the literature and a meta-analysis, which estimates the changes in body weight following thyroidectomy and examines its relationship with study follow-up time, gender, age, and indication for the procedure.

Material and Methods

Eligibility criteria

Studies published between 1998 and 2018 that reported body weight changes and/or body weight measurements before and after total thyroidectomy, with at least 2 months follow-up, were included. Only manuscripts written in the English language were included. The outcome of interest was the mean difference in body weight. Studies in which patients were treated with drugs other than levothyroxine or liothyronine, or had follow-up periods of less than 2 months in total, were excluded.

Study identification and selection

PubMed and Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Libraries search engines were utilized for the primary round of data gathering. The following keywords were used to search for studies evaluating selected outcomes in patients undergoing thyroidectomy: weight gain and thyroidectomy; thyroidectomy weight gain; hormone replacement therapy after thyroidectomy; T4 and T3 therapy after thyroidectomy; levothyroxine AND liothyronine AND thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH); levothyroxine AND liothyronine AND TSH AND athyreotic; levothyroxine AND liothyronine AND thyroidectomy; levothyroxine AND liothyronine AND TSH AND thyroidectomy. All manuscript titles and abstracts were read for potential eligible inclusion, and studies were selected based on the further assessment of full-text publications for eligibility. Additional studies reported in the references were identified and assessed for inclusion as well.

Data collection and management

Investigators collected the following information from each included study as available: study design, number of patients studied, number of total thyroidectomies, indications for surgery, age and sex distribution, average levothyroxine dose, average TSH pre- and post-treatment, average recorded weights at follow-ups, and average weight change. Data were extracted and compiled in tabular format for further analysis. Data were reviewed by 3 investigators (C.N.H., L.K., and F.S.C.), and discrepancies in the abstraction/interpretation of the data were resolved by consensus.

Statistical methods

Meta-analysis was performed using fixed effect and random effect models. For both models, the inverse study variance weighting was used, and DerSimonian-Laird estimator for the variance of the true effect’s distribution was considered in the random effect models. Univariable and multivariable meta-regression models were implemented to assess the association between weight change and study follow-up time, gender distribution, as well as age. The difference in effect sizes was also examined between subgroups based on indication for surgery.

Results

Study identification

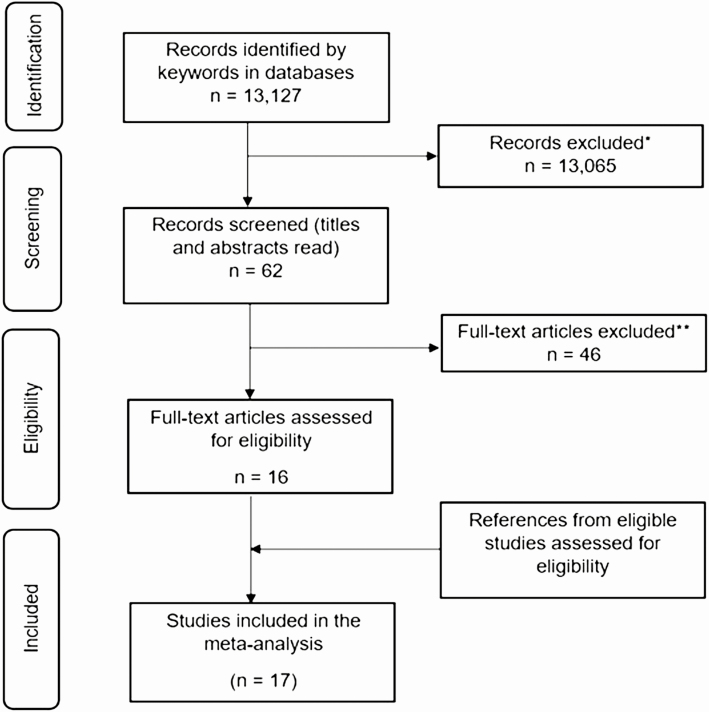

Our initial search generated 13 127 manuscripts. Of the studies identified, 17 met the inclusion criteria (2–10, 12, 18–24), with a total of 3164 patients. The study selection process (25) is described in Fig. 1, with a summary of the included studies in Table 1. Six studies were from the United States, 5 from Europe, 5 from Asia, and 2 from Oceania. Seven studies (5 from the United States) included patients with thyroid cancer, 10 studies included patients with benign nodular disease, 5 studies included patients with hyperthyroidism, and 1 study did not report the indication for surgery (2). In the aggregate we could attribute 1318 indications for surgery to thyroid cancer, 1336 to benign nodular disease, and 431 to hyperthyroidism. We were unable to identify the indications for surgery of the 79 patients reported by Glick et al (2).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of study selection. Study selection process: *Titles and abstracts were screened and studies were included if this revealed a possibility that the study would report weight gain after thyroidectomy; **full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Excluded studies included those that did not report body weight changes and/or body weight measurements before and after partial or total thyroidectomy, with at least 2-months’ follow-up.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author, Year, Reference | Enrollment Period | Total Patients | Overall Follow-up, Months | Overall Weight Change, kg (SD) | Indication | Number of Patients per Indication | Weight Change per Indication, kg (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bel Lassen 2017 (19) | 2001–2012 | 225 | 26 | 1.65 (4.7) | Euthyroid | 151 | 1 (4.9) |

| Hyperthyroid | 74 | 3.1 (4.3) | |||||

| Dale 2001 (4) | 1975–1998 | 13 | 6 | 10.27 (9.23) | Hyperthyroid | 13 | 10.27 (9.23) |

| Glick 2018 (2) | 2013–2014 | 79 | 18 | 0.06 (6.9) | Unassigned | 79 | 0.06 (6.9) |

| Jonklaas 2011 (3) | 2009–2010 | 120 | 12 | 3.1 (3.3) | Euthyroid | 120 | 3.1 (3.3) |

| Kedia 2016 (20) | 2006–2014 | 291 | 36 | 2.35 (8.57) | Euthyroid | 144 | 2.57 (9.41) |

| Cancer | 147 | 2.21 (7.77) | |||||

| Kormas 1998 (18) | Not reported | 8 | 12 | 0.5 (2.3) | Euthyroid | 8 | 0.5 (2.3) |

| Lang 2016 (7) | 2010–2013 | 581 | 12 | 1.16 (3.3) | Euthyroid | 581 | 1.16 (3.3) |

| Lombardi 2017 (21) | 2014–2015 | 155 | 2 | 0.16 (0.43) | Euthyroid | 155 | 0.16 (0.43) |

| Ozdemir 2010 (5) | 2006–2007 | 22 | 6 | 2 (2.5) | Euthyroid | 22 | 2 (2.5) |

| Polotsky 2012 (9) | 1995–2006 | 153 | 48 | 2.7 (4.6) | Cancer | 153 | 2.7 (4.6) |

| Rotondi 2014 (12) | 2005–2012 | 267 | 9 | 1.6 (4.1) | Euthyroid | 118 | 1.5 (4.1) |

| Cancer | 41 | 1.5 (4) | |||||

| Hyperthyroid | 108 | 1.7 (4.2) | |||||

| Schneider 2014 (22) | 2007–2012 | 204 | 13 | 4.7 (1) | Hyperthyroid | 204 | 4.7 (1) |

| Singh Ospina 2018 (23) | 2003–2006 | 157 | 36 | 0.32 (7.18) | Euthyroid | 7 | 2.76 (3.43) |

| 2000–2012 | Cancer | 150 | 0.15 (7.27) | ||||

| Sohn 2015 (10) | 2008 | 700 | 42 | 0.5 (3.1) | Cancer | 700 | 0.5 (3.1) |

| Tigas 2000 (8) | 1996–2000 | 57 | 16 | 6.1 (5.45) | Cancer | 25 | 0.6 (3) |

| Hyperthyroid | 32 | 10.4 (6.78) | |||||

| Weinreb 2011 (24) | Not reported | 102 | 99 | 1.51 (7.8) | Cancer | 102 | 1.51 (7.8) |

| Zihni 2017 (6) | 2011–2012 | 30 | 12 | 1.6 (3.8) | Euthyroid | 30 | 1.6 (3.8) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

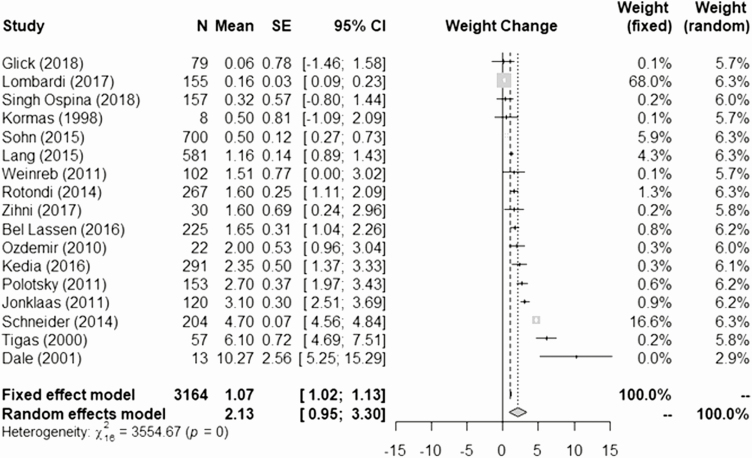

Weight change following thyroidectomy

The average follow-up duration was 23.8 ± 23.6 months, ranging from 2 to 99.6 months (8.3 years), and the average patient age was 48.9 ± 12.4 years. To estimate weight gain, we excluded patients with partial thyroidectomies to rule out confounders due to endogenous thyroid hormone secretion. The meta-analysis of the weight change of patients who underwent total thyroidectomy based on the fixed effects model was 1.07 kg, 95% confidence interval (CI) (1.02, 1.13), while using the random effects model with the DerSimonian-Larid variance estimator, the weight change was 2.13 kg, 95% CI (0.95, 3.30) (Fig. 2). The Cohran’s Q test for heterogeneity reported Q = 3554 (P-value < 0.0001), consistent with heterogeneity across studies. In consideration of the results of the Cohran’s Q test for heterogeneity, the random effects model appears to be more reliable for interpreting the data.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of weight changes following total thyroidectomy across the studies (3164 patients, 17 studies).

Age, gender, and follow-up

The association between weight change and age, gender, and study follow-up time was investigated using meta-regression (Table 2) based on total thyroidectomy cases. Age was found to be negatively associated with weight gain from both the univariable and multivariable model (P < 0.0001), while gender showed no significant association. Furthermore, the univariable and multivariable meta-regression model suggested a negative but not statistically significant association between study follow-up time and weight change. In addition, the relationship between study follow-up time and weight change was assessed using nonparametric, locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. The result indicated minimal impact of follow-up time on weight change. Collectively, the data did not present strong evidence of a significant association between study follow-up time and weight change.

Table 2.

Age, gender, and follow-up analysis

| Univariable Model (kg) | Multivariable Model (kg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | -0.238 (P < 0.001) | -0.263 (P < 0.001) |

| Gender (female percentage) | 1.314 (P = 0.869) | 3.190 (P = 0.552) |

| Follow up time (months) | -0.015 (P = 0.615) | -0.013 (P = 0.449) |

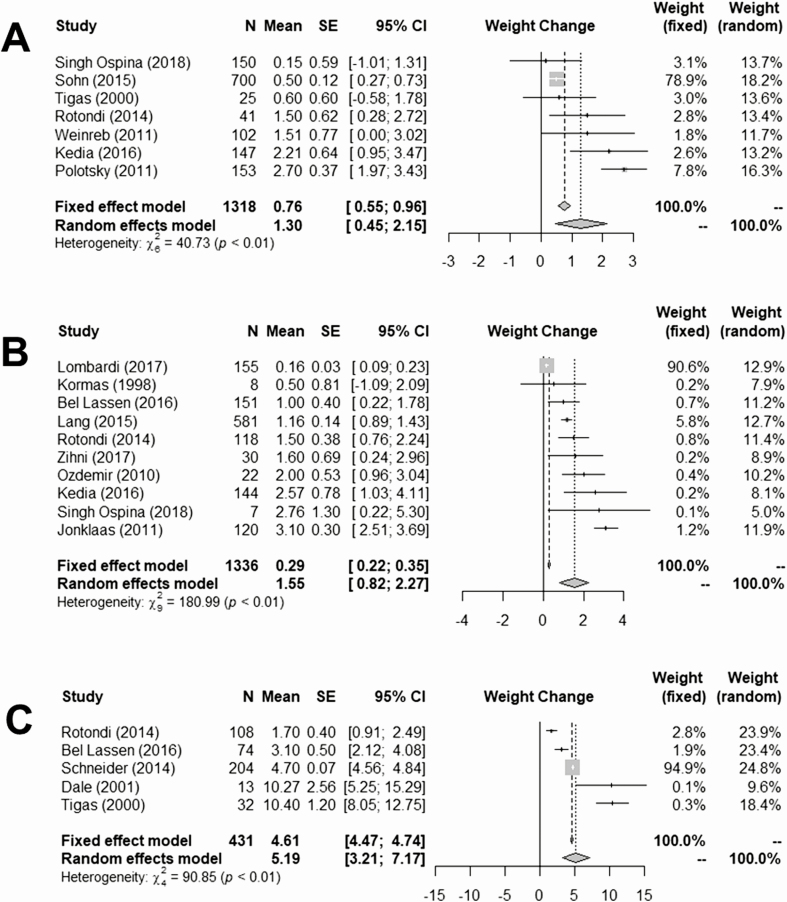

Indications for surgery

We next performed meta-analyses of the weight change for different indications for the surgical procedure, while excluding, similarly to the main meta-analysis, patients that underwent partial thyroidectomy (Fig. 3). Patients who had indication for total thyroidectomy because of thyroid cancer experienced weight gain of 1.30 kg, 95% CI (0.45, 2.15). Patients with euthyroid nodular disease experienced a similar weight gain of 1.55 kg, 95% CI (0.82, 2.27). The subgroup of patients that underwent total thyroidectomy for hyperthyroidism experienced a greater weight gain of 5.19 kg, 95% CI (3.21, 7.17). In all 3 subgroups, due to the heterogeneity among the studies, the random effects model estimates were considered more reliable. These results are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Subgroup meta-analysis according to the indications for surgery. A: Thyroid cancer (1318 patients, 7 studies). B: Euthyroid multinodular goiter (1336 patients, 10 studies). C: Hyperthyroidism (431 patients, 5 studies).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of weight changes relative to indications for surgery

| Indication for Surgery | Number of Patients | Weight Gain (kg) Based on Fixed Effects Model (95% CI) | Weight Gain (kg) Based on Random Effects Model (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid cancer | 1318 | 0.76 (0.55, 0.96) | 1.30 (0.45, 2.15) |

| Euthyroid (goiter) | 1336 | 0.29 (0.22, 0.35) | 1.55 (0.82, 2.27) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 431 | 4.61 (4.47, 4.74) | 5.19 (3.21, 7.17) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Weight gain despite thyroid hormone replacement is a major concern and driver of dissatisfaction among patients affected by hypothyroidism, but currently, with the exception of a small report (18), no formal prospective study has assessed the changes in body weight following thyroidectomy. Contrary to autoimmune thyroid disease, in which hypothyroidism is the result of a chronic process resulting in the progressive loss of function, total thyroidectomy causes an immediate transition from baseline (most often euthyroidism) to a state of hypothyroidism devoid of endogenous production of thyroid hormone, which relies entirely on the administration of exogenous thyroid hormone. Thus, postsurgical hypothyroidism could represent an ideal experimental model to assess the metabolic effects of hypothyroidism and thyroid hormone replacement (26). In the absence of prospective data, retrospective studies and meta-analyses can provide important information on the direction and effect size of the phenomenon of interest. Our systematic review identified 17 studies across 4 continents that provided sufficient numerosity to interrogate the relationship between thyroidectomy and changes in body weight.

Weight gain following thyroidectomy

The majority of the studies indicate a net increase in weight following total thyroidectomy, with the greater gain occurring within the first 2 years following surgery. The most significant weight gain was observed in patients undergoing thyroidectomy for hyperthyroidism, or in patients who underwent thyroid hormone withdrawal for treatment of thyroid cancer (8–10).

Our meta-analysis revealed statistically significant weight gain despite thyroid hormone replacement. Weight gain is a common occurrence in the adult population, with an average increase of 0.5–1.0 kg/year (27, 28), close to the estimates of our analyses; thus, studies may have not accrued sufficient patients to demonstrate a statistically significant difference from control groups (3, 23). It is also possible that only a minority of patients experience significant weight gain, while in aggregate the weight changes following thyroidectomy are similar to the ones observed in the general population. The heterogeneity of the findings and the wide variance within the individual studies support this interpretation.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 435 patients reported an average increase of 0.78 kg for thyroid cancer patients following thyroidectomy at the longest provided follow-up, and 1.07 kg for patients with benign nodules at 1 to 2 years of follow-up (23). The present analysis indicates a greater increase in weight during the first 2 years following surgery, while a regression to the mean was observed from 3 years following the intervention. The differences with our analysis can be attributed to the methodology, as our study included covariates such as age and gender. Additionally, we included a larger number of studies as well as patients with various indications for surgery.

Weight gain and follow-up

The relationship between weight change and follow-up time is still not completely defined; from our univariable and multivariable meta-regression models, the follow-up time showed a not statistically significant trend. Other studies also show mixed results. A study of 30 patients who underwent total thyroidectomy found that the weight change difference between the 6th and 12th months postoperatively was not statistically significant (6). A retrospective review of 267 thyroidectomized patients found that short-term changes (defined as 40–60 days postoperatively) in body weight were highly predictive of the outcome at 9 months (12). Another retrospective review of 107 patients found that patients’ weight changes increased with time (although it did not achieve statistical significance) (2). Singh Ospina reported that the number of patients whose weight increased between 5 and 10 kg increased during each year of follow-up: 16% of the patients gained between 5 and 10 kg at 3 years of follow-up; however, no predictors of weight change were identified, and the changes were not statistically different from the general population (23). It is possible that our finding of a downward trend between follow-up time and weight gain is attributable to the limited number of studies with longest follow-up time (over 90 months), which could have skewed our analysis. Additionally, the longer follow-up in studies focused on thyroid cancer compared with studies including benign indications for surgery may have played a confounder effect. Conversely, longer follow-up time could generate a regression to the mean effect due to unaccounted factors influencing weight changes both in the thyroidectomized and general population.

Weight gain and gender

Covariate analysis of gender revealed no significant association, although a higher female percentage in the study population tended to be associated with greater weight gain. This finding coincided with others’ reports (2, 5, 7, 12, 23, 24). However, several studies included in this analysis had conflicting results. A chart review of 120 patients demonstrated that postmenopausal women experienced statistically more weight gain than men (4.4 vs 2.5 kg) and premenopausal women (4.4 vs 2.3 kg) (3). Conversely, another study of 153 patients found that men had a greater weight gain than women (8). Lastly, a retrospective chart review of 700 patients found significant weight gain after 3 to 4 years of initial treatment for females, but not for males (10). The heterogeneity of the study populations and ethnicities (United States, Europe, Australia, and Asia) may also be a contributing factor to these differences.

Weight gain and age at surgery

We used meta-regression models to explore the interaction between age at the time of surgery and weight trajectory. Our results suggest that age has a significant negative association with weight change. From the univariable meta-regression model, for each year older, the weight change is diminished by 0.238 kg. We obtained very similar estimates from the multivariable meta-regression model: 0.263 kg less weight gain per additional year of age. In aggregate, the results suggest that younger patients are more likely to gain more weight. However, due to severe heterogeneity among studies and the use of only mean age for overall studies in analysis, there are many distortions possible in the relationship between age and weight gain. Nevertheless, the findings are supported by the largest studies we identified: Lang and colleagues’ study of 898 patients who underwent thyroidectomy for benign nontoxic nodular goiter found that younger age was a significant predictive factor for weight gain at 12 months (7). Likewise, Sohn and colleagues, in a retrospective review of 700 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer who underwent a total thyroidectomy, found that there was a significant association between age at surgery and weight gain (r = -0.25, P < 0.01): the younger the age at surgery, the greater the weight gain (10). However, smaller studies had opposite findings: in a prospective study of 33 patients with total thyroidectomy for benign multinodular goiter aimed to evaluate the effect of thyroxine replacement on body mass index (BMI), Ozdemir and colleagues found that the weight gain in patients over age 45 (2.2 ± 2.7 kg) was greater than in those under age 45 (0.1 ± 1.3 kg) (5). Other retrospective studies found no relationship between age and weight change (2, 3, 12). Although the results are conflicting, the consistency of findings among the larger studies support our finding that younger patients are more likely to gain more weight.

It is important to highlight the strengths and limitations of this analysis. Since the vast majority of the studies were retrospective, the accuracy of measurement and recording of weights is not guaranteed. However, weight measurements obtained during routine clinical visits are highly correlated with those of research measures (29, 30). Additionally, the meta-analysis method, by aggregating a large number of patients from different studies, should improve the accuracy of the estimation. Importantly, the vast majority of studies, even those which did not demonstrate a statistically significant weight gain, indicated an increase in weight following thyroidectomy. We observed significant heterogeneity of weight change distribution among studies, and among patients of differing indications for surgery, type of postsurgery thyroid treatment, and follow-up time points. Additionally, the different ethnic groups included in this analysis further contribute to the heterogeneity of the study population. This reduces the power of the estimate of weight change and its relationship with covariates. The heterogeneity also suggests that the random effects model may be more representative than the fixed effects model to estimate the average weight gain after surgery. Several studies included patients who underwent total thyroidectomy before the release of the latest American Thyroid Association guidelines for the treatment of thyroid cancer (31), so it is possible that a significant number of patients with thyroid cancer had undergone withdrawal-stimulated radioactive iodine therapy and thyroid hormone suppressive therapy. Nonetheless, one can infer that recombinant TSH has been widely employed in the studies that recruited patients after 2007 (32). Not surprisingly, the greater increase in weight was observed among hyperthyroid patients undergoing thyroidectomy (Fig. 3) with a 5.19 kg, 95% CI (3.21, 7.17) point estimate, not dissimilar to what observed in patients treated with radioactive iodine (33, 34). Interestingly, the point estimates in weight gain did not differ substantially between patients who underwent thyroidectomy for cancer (0.96 kg) and those for euthyroid multinodular goiter while being euthyroid (0.68 kg). This is consistent with reports that changes in levothyroxine dose do not cause significant changes in energy expenditure (35). In our systematic review, we did not identify a sufficient number of patients treated with levothyroxine/liothyronine combination or desiccated thyroid extracts to perform a meaningful analysis.

Some studies also have a small sample size of patients who underwent thyroidectomy (Dale, n = 13; Ozdemir, n = 22; Zihni, n = 30; Kormas, n = 8) (4–6), and some weight gain values were obtained from studies in which their main objective was not to estimate weight change post-thyroidectomy. Nevertheless, this analysis presents a large sample of thyroidectomy patients (n = 3164), which we believe provided us sufficient power to interrogate the effect of thyroidectomy on body weight. Also, by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis, an estimate of weight change and its relationship with covariates (age, gender, and follow-up time) post-thyroidectomy were obtained, further strengthening the applicability of these results.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis demonstrates that patients undergoing thyroidectomy experience possible mild weight gain, mostly in younger individuals in the first 6 months following surgery, with significant variance within, and heterogeneity of findings among studies. The large variance indicates that while the point estimate of weight gain is small, some patients experience much larger changes, which can negatively affect well-being and health outcomes. Although it is difficult to estimate the health risk associated with an individual’s weight gain, large epidemiologic data provide some prospective on the association between body weight and health consequences. A large retrospective analysis concluded that every 1 kg increase in weight is associated with a 4.5% increase in the prevalence of diabetes (36). This finding was recently confirmed in a prospective study (37). Conversely, even a modest, sustained weight loss of 1 kg is associated with a 16% reduction in the risk of diabetes (38). While the greatest weight gain was observed in patients undergoing thyroidectomy because of hyperthyroidism, a small but significant weight gain was also present in patients who underwent thyroidectomy while euthyroid, irrespective of the indication for surgery. It is important to note that while the point estimate of these groups is similar to weight change observed the general population, and that a significant number of patients will probably experience negligible changes, weight gain in the upper boundaries of the CI could contribute to untoward health outcomes. Prospective studies directed to assess the pathophysiology of weight gain post-thyroidectomy are necessary to identify the subgroup of patients who are more likely to gain weight following the procedure, and to test treatment modalities directed to minimize post-thyroidectomy weight gain and its impact on quality of life.

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: Dr Celi received honoraria as consultant by IBSA Pharma, Kashiv, and Acella pharmaceuticals. Christine N. Huynh is supported by a grant of the Honors College, Virginia Commonwealth University. This work was supported by the NIH-NIDDK grant 1 R21 DK122310-01A1

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Sosa JA, Hanna JW, Robinson KA, Lanman RB. Increases in thyroid nodule fine-needle aspirations, operations, and diagnoses of thyroid cancer in the United States. Surgery. 2013;154(6):1420–1426; discussion 1426–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Glick R, Chang P, Michail P, Serpell JW, Grodski S, Lee JC. Body weight change is unpredictable after total thyroidectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88(3):162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jonklaas J, Nsouli-Maktabi H. Weight changes in euthyroid patients undergoing thyroidectomy. Thyroid. 2011;21(12):1343–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dale J, Daykin J, Holder R, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA. Weight gain following treatment of hyperthyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2001;55(2):233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ozdemir S, Ozis ES, Gulpinar K, Aydin TH, Suzen B, Korkmaz A. The effects of levothyroxine substitution on body composition and body mass after total thyroidectomy for benign nodular goiter. Endocr Regul. 2010;44(4):147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zihni I, Zihni B, Karakose O, et al. An evaluation of the metabolic profile in total thyroidectomy. Galician Med J. 2017;24(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lang BH, Zhi H, Cowling BJ. Assessing perioperative body weight changes in patients thyroidectomized for a benign nontoxic nodular goitre. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;84(6):882–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tigas S, Idiculla J, Beckett G, Toft A. Is excessive weight gain after ablative treatment of hyperthyroidism due to inadequate thyroid hormone therapy? Thyroid. 2000;10(12): 1107–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polotsky HN, Brokhin M, Omry G, Polotsky AJ, Tuttle RM. Iatrogenic hyperthyroidism does not promote weight loss or prevent ageing-related increases in body mass in thyroid cancer survivors. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;76(4):582–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sohn SY, Joung JY, Cho YY, et al. Weight changes in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma during postoperative long-term follow-up under thyroid stimulating hormone suppression. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2015;30(3):343–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saravanan P, Chau WF, Roberts N, Vedhara K, Greenwood R, Dayan CM. Psychological well-being in patients on “adequate” doses of l-thyroxine: results of a large, controlled community-based questionnaire study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;57(5):577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rotondi M, Croce L, Pallavicini C, et al. Body weight changes in a large cohort of patients subjected to thyroidectomy for a wide spectrum of thyroid diseases. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(11):1151–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tan NC, Chew RQ, Subramanian RC, Sankari U, Koh YLE, Cho LW. Patients on levothyroxine replacement in the community: association between hypothyroidism symptoms, co-morbidities and their quality of life. Fam Pract. 2018;36(3):269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Malley B, Hickey J, Nevens E. Thyroid dysfunction – weight problems and the psyche: the patients’ perspective. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2000;13(4):243–248. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rubic M, Kuna SK, Tesic V, Samardzic T, Despot M, Huic D. The most common factors influencing on quality of life of thyroid cancer patients after thyroid hormone withdrawal. Psychiatr Danub. 2014;26(Suppl 3):520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelderman-Bolk N, Visser TJ, Tijssen JP, Berghout A. Quality of life in patients with primary hypothyroidism related to BMI. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(4):507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goel A, Shivaprasad C, Kolly A, Pulikkal AA, Boppana R, Dwarakanath CS. Frequent occurrence of faulty practices, misconceptions and lack of knowledge among hypothyroid patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(7):OC15–OC20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kormas N, Diamond T, O’Sullivan A, Smerdely P. Body mass and body composition after total thyroidectomy for benign goiters. Thyroid. 1998;8(9):773–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bel Lassen P, Kyrilli A, Lytrivi M, Ruiz Patino M, Corvilain B. Total thyroidectomy: a clue to understanding the metabolic changes induced by subclinical hyperthyroidism? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;86(2):270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kedia R, Lowes A, Gillis S, Markert R, Koroscil T. Iatrogenic subclinical hyperthyroidism does not promote weight loss. South Med J. 2016;109(2):97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lombardi CP, Bocale R, Barini A, et al. Comparative study between the effects of replacement therapy with liquid and tablet formulations of levothyroxine on mood states, self-perceived psychological well-being and thyroid hormone profile in recently thyroidectomized patients. Endocrine. 2017;55(1):51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schneider DF, Nookala R, Jaraczewski TJ, Chen H, Solorzano CC, Sippel RS. Thyroidectomy as primary treatment optimizes body mass index in patients with hyperthyroidism. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(7):2303–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh Ospina N, Castaneda-Guarderas A, Hamidi O, et al. Weight changes after thyroid surgery for patients with benign thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer: population-based study and systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2018;28(5):639–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weinreb JT, Yang Y, Braunstein GD. Do patients gain weight after thyroidectomy for thyroid cancer? Thyroid. 2011;21(12):1339–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Plos Med. 2009;6(7):1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Madan RC, Celi FS. Hypothyroidism: rationale,therapeutic goals, and design. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Williamson DF. Descriptive epidemiology of body weight and weight change in U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(7 Pt 2):646–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drøyvold WB, Nilsen TI, Krüger O, et al. Change in height, weight and body mass index: longitudinal data from the HUNT Study in Norway. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006;30(6):935–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arterburn D, Ichikawa L, Ludman EJ, et al. Validity of clinical body weight measures as substitutes for missing data in a randomized trial. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2008;2(4):277–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DiMaria-Ghalili RA. Medical record versus researcher measures of height and weight. Biol Res Nurs. 2006;8(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Food and Drug Administration. Search Orphan Drug Designations and Approvals. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/detailedIndex.cfm?cfgridkey=142301 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gibb FW, Zammitt NN, Beckett GJ, Strachan MW. Predictors of treatment failure, incipient hypothyroidism, and weight gain following radioiodine therapy for Graves’ thyrotoxicosis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2013;36(9):764–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Metso S, Jaatinen P, Huhtala H, Luukkaala T, Oksala H, Salmi J. Long-term follow-up study of radioiodine treatment of hyperthyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;61(5):641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Samuels MH, Kolobova I, Niederhausen M, Purnell JQ, Schuff KG. Effects of altering levothyroxine dose on energy expenditure and body composition in subjects treated with LT4. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(11):4163–4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ford ES, Williamson DF, Liu S. Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(3):214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Feldman AL, Griffin SJ, Ahern AL, et al. Impact of weight maintenance and loss on diabetes risk and burden: a population-based study in 33,184 participants. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2102–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.