Abstract

Background:

There is a significant proportion of workers with mental disorders who either are struggling at work or who are trying to return to work from a disability leave.

Objective:

Using a population-based survey of working adults in Ontario, Canada, this paper examines the perceptions of workers towards mental disorders in the workplace.

Methods:

Data are from a sample of 2219 working adults identified through random digit dialing who either completed a telephone questionnaire administered by professional interviewers or a web-based survey.

Results:

A third of workers would not tell their managers if they experienced mental health problems. Rather than a single factor, workers more often identified a combination of factors that would encourage disclosure to their managers. One of the most identified disincentives was the fear of damaging their careers. The most pervasive reasons for concerns about a colleague with a mental health problem included safety and the colleague's reliability.

Conclusion:

Although critical for workers who experience a mental disorder and who find work challenging, a significant proportion do not seek support. One barrier is fear of negative repercussions. Organizations' policies can create safe environments and the provision of resources and training to managers that enable them to implement them. By making disclosure safe, stigma and the burden of mental disorders in the workplace can be decreased.

Keywords: Mental disorders, Social stigma, Workplace, Disclosure, Mental disorders/psychology, Mental health

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

A significant proportion of workers have mental disorders who either are struggling at work or who are trying to return to work from a disability leave.

Support of these workers could benefit their workplaces and minimize productivity loss.

Supervisors and co-workers are the two groups that critically contribute to mental health.

The most prevalent reason for not disclosing their mental health problems is that workers are afraid that it would affect their careers.

A significant proportion of workers who are concerned about how mental health problems affect the workplace worry about the reliability of colleagues who have a mental health problem.

Males and those who were members of visible minorities were less likely to have positive attitudes towards mental illness.

Managers may be an effective conduit of education regarding mental illness and stigma reduction.

Introduction

There is a significant proportion of workers with mental disorders who either are struggling at work or who are trying to return to work from a disability leave. For example, between 8% and 10% of the working population experiences a major depressive episode during a 30-day period.1,2 In addition, annually almost 3% of workers are on short-term work disability leave related to a mental disorder;3 more than 75% of these workers return to work at the end of their disability leaves.4 These workers are at increased risk of decreased work productivity during their episodes of mental illness.5-7 This suggests there is a portion of the workforce that could benefit from support at their workplaces.

Although they need support, workers are often hesitant to ask for it. Support is especially critical for workers who are finding work challenging, as well as to minimize productivity loss. Part of the hesitation to ask for help may lie in the fact that it requires either recognizing the need for help or disclosing the mental disorder to others.8 The discloser becomes vulnerable to stigma.9 As a result, the discloser is at risk of losing the support of supervisors and co-workers because of prejudices related to mental disorders. Yet, supervisors and co-workers are the two groups that critically contribute to mental health.10,11 Thus, rather than risk affecting work relationships, workers may choose to try to hide their struggles.

Stigma Related to Mental Disorders

Thornicroft and colleagues12 identify negative attitudes (ie , prejudice) as a major component of stigma. These prejudices can turn into negative actions (ie , discrimination). As Thornicroft, et al ,12 point out, copious studies have been conducted to describe the substance of the negative attitudes. Anticipated or actual, the negative attitudes can become a significant deterrent to help seeking in the workplace.9

Often, these negative attitudes take the form of fear. Among the general public, there is fear that mental illness is associated with violence.13,14 There is also the belief that symptoms can lead to undesirable behavior or unpredictability.13,14 These fears of violence and unpredictability also exist among the working population.15,16 Related to unpredictability, there is also the fear that workers with mental illnesses will be relatively less reliable, resulting in additional work for co-workers.16-18

Reasons for Concealment

As a result of these negative attitudes, managers have expressed concerns about how employees with mental disorders will be treated by co-workers.15,16 The reluctance of workers who have mental disorders to disclose their struggles also reflects the desire to avoid these potentially negative attitudes and actions.9 In their review of the literature, Brohan and colleagues9 found that people hesitate to disclose their mental illnesses because they are afraid that they would lose their credibility, be rejected and become the object of gossip. In short, they fear that they will become targets of prejudice and discrimination.

The literature suggests that not only do workers with mental disorders seek to avoid the negative judgments of others but of themselves as well. Along with externally experienced stigma, there is self-directed stigma that includes negative value judgments about oneself.19 For example, workers indicate that they did not want other people to know about their mental illness because it was either a private matter or that it would go away in due course.9 That is, workers potentially do not want to view themselves as either needing help or having difficulty performing.8 In essence, to speak about it is to acknowledge it.

Reasons for Disclosure

Although there are factors that prevent disclosure, there are also positive workplace factors that can support it. In a survey of managers and professionals, Ellison, et al ,20 found that 80% would disclose that they had a mental disorder to their supervisor. A lower proportion of 73% would tell a co-worker and about 28% would tell their human resources department.20 This suggests that managers play critical roles in the decision to disclose.

Some of the reasons that people were willing to disclose their experiences of mental illness were to be able to access work accommodation and support.9 For instance, Ellison and colleagues20 observed that workers chose to disclose if they could be assured of non-negative consequences, had secure employment and were appreciated by their supervisors. Therefore, one of the factors that influenced their decision was having a safe and secure work environment.

Workers also indicated that they disclose the need for help because they felt that was the honest thing to do.9 In their study, Ellison and colleagues20 found that one of the main reasons for disclosure was because circumstances made it seem necessary, ie , they recognized they needed help and were hopeful that they would receive it.

The decision to disclose is complex. However, one step for employers to decrease the impact of mental disorders on the workplace would be to implement interventions to address the fears and concerns that could lead to negative experiences emerging from disclosure for the workers affected by mental disorders, their co-workers and managers. The objective of this study was to use a population-based survey of 2219 working adults in Ontario, Canada to examine the perceptions that workers have regarding mental disorders in the workplace. The results of these analyses can be useful in understanding the magnitude and combinations of the types of fears and concerns that are most prevalent and that discourage and encourage help seeking at work. This information could be used to develop workplace programs that help to foster supportive work environments that also decrease the productivity losses related to mental disorders and promote help seeking at work.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The data for this study are from a sample of 2219 working adults identified through random digit dialing who either completed a telephone questionnaire that was administered by professional interviewers (n=2145) or a web-based survey (n=74) during the period from October 2013 to January 2014. Inclusion criteria included 1) age ≥18 years, 2) living in Ontario, and 3) workforce participation during the 12 months preceding the survey. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health’s Research Ethics Board reviewed the project protocol.

Variables

There were four types of variables used in these analyses 1) demographic, 2) attitudes towards disclosing a mental health problem to a manager, 3) attitudes towards mental health problems in the workplace, and 4) mental health status.

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic information was collected including sex (male/female), age (<30, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–64, and ≥65 years), marital status (single/never married, married/cohabiting, divorced/separated/widowed), educational attainment (≤high school yes/no) and Race (white/non-white). In addition, an occupation variable was created to indicate whether the respondent was in a management/professional position (yes/no).

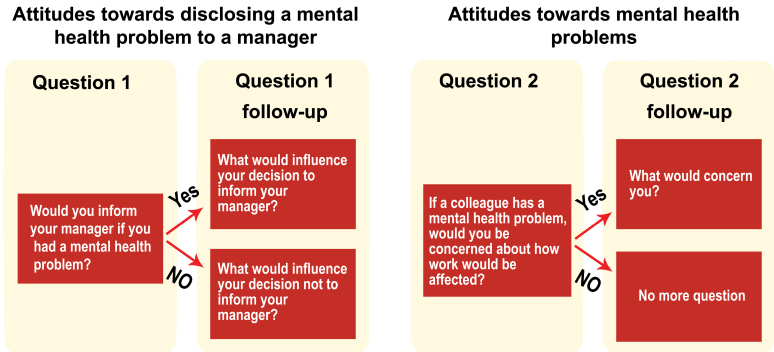

Attitudes towards Disclosing a Mental Health Problem to a Manager

Three questions were used to gather information about disclosure to a manager ( Fig 1). They were adapted from a study conducted by Brohan, et al ,18 that examined employers’ attitudes towards mental illness in their workforces. The first question in the series asked, “Would you inform your manager if you had a mental health problem?” Each of the subsequent two sub-questions was asked based on the response to the first. If the first question was answered affirmatively, the respondent was asked, “What would influence your decision to inform your manager?” Alternatively, if the first question was answered negatively, the question posed was, “What would influence your decision not to inform your manager?” The answers to these two sub-questions were assigned to response categories.

Figure 1.

Survey questions that were analyzed

Attitudes towards Mental Health Problems

Two questions were used to collect information about attitudes toward mental disorders (Fig 1). The questions for this section also were adapted from Brohan, et al .18 The first question in this series queried was, “If a colleague has a mental health problem, would you be concerned about how work would be affected?” If the respondent responded affirmatively, this question was followed with the sub-question, “What would concern you?” The answers to this sub-question were assigned to response categories.

Depression Measure

The Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) was used to identify whether a worker was experiencing a current depressive episode.21 The PHQ-8 is an 8-item depression measure that was developed for use in population surveys. It has been validated using a general population sample and has been shown to have good sensitivity and specificity for depression.21 Using the total PHQ-8 score, an indicator variable for depression was created such that a score ≥10 indicated the presence of moderate to severe depression.

Statistical Analysis

χ2 test was used to examine the differences in the prevalence by respondent characteristics for those who: 1) were willing to tell a manager about a mental health problem, and 2) would be concerned if a colleague had a mental health problem.

The 95% confidence intervals were calculated for: the prevalence rates for the responses for 1) the two questions that asked about what influenced the decision to inform a manager about a mental health problem, and 2) the question inquiring why a respondent would be concerned if a colleague had a mental health problem.

Results

The results indicate (Table 1) that about 61.4% (95% CI: 59.2–63.5) of respondents would tell their current manager if they were experiencing a mental health problem. However, there were differences among groups. Workers who were between 40 and 49 years were significantly less likely to inform their managers (57.5%, p=0.022) as were people with more than a high school education (59.6% vs 68.0%, p=0.0013), who were white (60.2% vs non-white 66.7%, p=0.04) and who were currently experiencing depression (45.4% vs 64.2%, p<0.0001).

| Table 1: Description of respondents by willingness to disclose a mental health problem to a manager | ||||

| Characteristics | Total n (%) |

Would disclose a mental he alth problem to a manager n (%) |

Would not disclose a mental health problem to a manager n (%) |

p value |

| Male | 799 (36.1) | 424 (62.4) | 256 (37.7) | 0.54 |

| Female | 1416 (64.0) | 778 (61.0) | 499 (39.1) | |

| Age (yrs) | ||||

| <30 | 157 (7.2) | 94 (65.3) | 50 (34.7) | 0.32 |

| 30–39 | 367 (16.8) | 200 (61.0) | 128 (39.0) | 0.88 |

| 40–49 | 637 (29.1) | 331 (57.5) | 245 (42.5) | 0.022 |

| 50–59 | 718 (32.8) | 396 (62.9) | 234 (37.1) | 0.35 |

| 60–64 | 195 (9.0) | 111 (65.3) | 59 (34.7) | 0.27 |

| ≥65 | 116 (5.3) | 54 (63.5) | 31 (36.5) | 0.67 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 496 (22.6) | 302 (68.0) | 142 (32.0) | 0.0013 |

| More than high school | 1697 (77.4) | 889 (59.6) | 603 (40.4) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1608 (84.0) | 874 (60.2) | 578 (39.8) | 0.040 |

| Non-white | 306 (16.0) | 190 (66.7) | 95 (33.3) | |

| Position | ||||

| Management | 1083 (49.5) | 565 (60.8) | 364 (39.2) | 0.53 |

| Non-management | 1104 (50.5) | 624 (62.2) | 379 (37.8) | |

| Current depression | ||||

| Yes | 305 (14.6) | 128 (45.4) | 154 (54.6) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1791 (85. 5) | 1011 (64.2) | 563 (35.8) | |

| Note: Numbers may not sum due to missing values. | ||||

Reasons for Disclosure

In total, among workers who indicated they would tell their managers, 79.4% (n=935) reported that a good relationship with their managers would encourage their disclosure (Table 2). However, only 27.6% (n=325) suggested that this would be the only reason for disclosing. Rather, 8.9% (n=105) indicated their decisions also would be encouraged by supportive co-workers.

| Table 2: Attitudes towards disclosing a mental health problem to a manager | ||

| Reasons | n (%) | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Reasons to disclose (n=1178) | ||

| Good relationship with manager | 935 (79.4) | 77.1–81.7 |

| Organizational policies and practices | 593 (50.3) | 47.5–53.2 |

| Supportive co-workers | 571 (48.5) | 45.6–51.3 |

| Positive experiences of others in organization | 398 (33.8) | 31.1–36.5 |

| Responsible thing to do | 78 (6.6) | 5.2–8.0 |

| Other | 40 (3.4) | 2.4–4.4 |

| Reasons not to disclose (n=717) | ||

| Afraid of hurting career | 392 (54.6) | 51.0–58.3 |

| Fear of losing friends | 105 (14.6) | 12.1–17.2 |

| Bad experiences of others | 140 (19.5) | 16.6–22.4 |

| Would not impact work | 215 (30.0) | 26.6–33.3 |

| Handle on own/private matter | 79 (11.0) | 8.7–13.3 |

| Lack of trust | 47 (6.6) | 4.7–8.4 |

| Embarrassed | 33 (4.6) | 3.1–6.1 |

| Other | 31 (4.3) | 2.8–5.8 |

| Note: Numbers may not sum due to missing values. | ||

Overall, about 50.3% (n=593) indicated that organizational policies and practices were important (Table 2). However, only 7.9% (n=93) pointed to organizational policies and practices alone as sufficient encouragement. For about 5.2% (n=61), good relationships with their managers were also incentives. About 35.2% (n=415) indicated their decision would depend on the combination of their relationships with their managers, supportive colleagues and organizational policies and procedures.

Among workers who reported they would disclose, a total of 33.8% (n=398) suggested that the positive experiences of others in the organization were an influential factor. Yet, only 1.1% (n=13) indicated that this factor alone would influence their decision. It was most frequently identified (26.3%, n=305) as one of four factors including relationships with their managers, supportive colleagues and organizational policies and procedures.

Reasons Not to Disclose

In contrast, among workers who would not tell their managers, 54.6% (n=392) identified fear that it would affect their careers as being the reason. In addition, 29.7% (n=213) indicated this reason alone as a disincentive to disclosing. Another 7.3% (n=52) reported that in addition to fear about the potential effect on their careers, they pointed to the bad experiences of others. Furthermore, 5.9% (n=26) coupled this reason with the fear of losing friends. For 6.4% (n=23), the combination of all three of the previous factors was a reason for not disclosing.

About 30.0% (n=215) suggested that they would not inform their managers because their mental health problems would not affect their work. This was the sole reason given by 19.8% (n=142) respondents.

Reasons for Concern

When asked if they would be concerned about how the work would be affected if a colleague had a mental illness, 64.2% (95% CI: 62.2–66.3) answered affirmatively (Table 3). There were significant differences among groups. Men were more likely than women to express a concern (71.3% vs 60.1%, p<0.0001). Those who were 60 years or older were more likely to have a concern. In addition, workers in management positions were more likely to be concerned (66.9% vs 61.5%, p=0.010) as were those who were non-white (76.9% vs 60.1%, p<0.0001).

| Table 3: Description of respondents by concern about how work would be affected if a colleague has a mental health problem | |||

| Characteristics |

Would be concerned n (%) |

Would not be concerned

n (%) |

p value |

| Male | 542 (71.3) | 218 (28.7) | <0.0001 |

| Female | 789 (60.1) | 524 (39.9) | |

| Age (yrs) | |||

| <30 | 93 (61.2) | 59 (38.8) | 0.43 |

| 30–39 | 216 (63.3) | 125 (36.7) | 0.76 |

| 40–49 | 360 (60.1) | 239 (39.9) | 0.016 |

| 50–59 | 444 (65.7) | 232 (34.3) | 0.29 |

| 60–64 | 131 (70.8) | 54 (29.2) | 0.045 |

| ≥65 | 69 (71.9) | 27 (28.1) | 0.10 |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 288 (62.1) | 176 (37.9) | 0.26 |

| More than high school | 1033 (64.9) | 558 (35.1) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 912 (60.1) | 606 (39.9) | <0.0001 |

| Non-white | 223 (76.9) | 67 (23.1) | |

| Position | |||

| Management | 674 (66.9) | 333 (33.1) | 0.010 |

| Non-management | 639 (61.5) | 400 (38.5) | |

| Current depression | |||

| Yes | 177 (60.4) | 116 (39.6) | 0.15 |

| No | 1087 (64.7) | 592 (35.3) | |

| Note: Numbers may not sum due to missing values. | |||

About 42.7% (n=560) of workers who indicated that they would be concerned indicated that the reason was related to safety. For only 15.0% (n=197) of respondents this was the only factor that would raise a concern. Another 8.4% (n=110) were additionally anxious about the reliability of the worker and 10.8% (n=141) had misgivings about these two factors along with not wanting to make the mental health problem worse (Table 4).

| Table 4: Reasons for concern about mental health problems in co-workers | ||

| Reasons | n (%) | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Safety of self and others | 560 (42.7) | 40.0–45.4 |

| Reliability | 556 (42.4) | 39.7–45.1 |

| Potentially adding to mental health problem | 298 (22.7) | 20.5–25.0 |

| Wanting to help | 649 (49.5) | 46.8–52.2 |

| Effect on the work environment | 69 (5.3) | 4.1–6.5 |

| Health and well-being of person | 57 (4.3) | 3.2–5.5 |

| Other | 34 (2.6) | 1.7–3.5 |

| Note: Numbers may not sum due to missing values. | ||

Another reason was the desire to help the person; overall 49.5% (n=649) said they would be concerned about a colleague because they would want to help. However, for only 19.0%, this was their only reason for worry. The remainder was concerned either about safety, reliability or the possibility of exacerbating the mental health problem (Table 4).

Discussion

This is one of the first population-based surveys of Canadian workers regarding their perceptions about mental disorders in the workplace. These analyses indicate that a third of the workers interviewed would not tell their managers that they were experiencing mental health problems. The most prevalent reason for not disclosing is that they are afraid that it would affect their careers. The results also suggest that a significant proportion of workers who are concerned about how mental health problems affect the workplace worry about the reliability of colleagues who have a mental health problem. Corroborating reports from other countries, these results suggest that a significantly higher proportion of workers in management positions indicated they would be concerned about the effects of mental health problems on the workplace. Similar attitudes were reported among UK and Swiss employers.17,22

The results also suggest there are some sub-groups that are more at risk of being concerned about a colleague having mental health problems. These included males and those who were visible minorities. Similar results were reported by Kobau, et al ,23 who observed that males and those who were members of visible minorities were less likely to have positive attitudes about mental illness. It may be useful for further research to explore attitudes in these groups to understand how negative attitudes effectively could be addressed in these sub-groups.

At the same time, responses to questions regarding willingness to disclose a mental health problem to a manager indicate that workers with lower educational attainment and visible minorities are more willing to disclose. This either may be a signal of trust in management or a feeling of obligation towards management. This result could suggest that managers may be an effective conduit of education regarding mental illness and stigma reduction. However, if managers are among the groups that are more likely to have negative attitudes towards mental illness, it may be necessary for them to be among the first targets for workplace anti-stigma activities.

Studies also have reported that employees who return from disability leave related to mental disorders are fearful of their manager’s expectations and their abilities to work at pre-disability leave levels.16 The results of the current study may also reflect this apprehension; workers currently experiencing depression are significantly less likely to tell their managers about their mental health problems.

These results suggest there is a challenge of addressing the fear that mental disorders will result in decreased dependability and by extension, productivity. At the same time, studies show that one of the work outcomes of mental disorders is decreased productivity.6,7 Thus, to an extent, this may be a valid but not necessarily insurmountable concern. Allen and Carlson8 suggest that disclosure planning may be one way in which this can be addressed. Rather than focus on the diagnoses, the plan would address areas in which there are functional difficulties. The manager and worker could create a list of work accommodations to help compensate for the difficulties. In this way, there is an acknowledgement of potential decreases in productivity. Concomitantly, there is a concrete way of meeting them. In this way, it reinforces the idea that struggles with mental disorders at work are something that can be successfully addressed.8

These study results also indicate that together, two of the most important factors related to the willingness to disclose are supportive managers and organizational policies and practices. These results reflect those identified in Brohan, et al’ s,9 systematic review. They also highlight the need for training and supports to assist supervisors by building their confidence and abilities to manage workers with mental health problems.9 Without these resources, supervisors can feel vulnerable.16 This also underscores the need for organization policies and practices that provide managers with resources that enables them to provide accommodations without creating burdensome additional work for co-workers.

It is important for this management training to include skills in creating a supportive and secure environment.20 Gates describes work accommodations as having a social impact.24 Thus, managers may face challenges in creating this culture given the potential discrimination associated with mental disorders. For example, respondents of this study indicate that a fear of violence related to mental disorders persists. This fear has been observed during the past three decades; there is a fear people with mental disorders are prone to violence and unpredictable behaviors.14,15 These misgivings on the part of co-workers can result in ostracism and negative reactions.15 Therefore, managers must not only support the worker who needs help but also manage co-worker behavior.

These study results also suggest there is the potential that workers either are not aware that they need help or do not think they need help. Mojtabai, et al ,25 found that this is a common barrier to help seeking among people with mental disorders. This perspective could stem from stigma.9,26 Yet, these results also indicate there are colleagues who are interested in helping co-workers who need help. This raises another role for managers—to help workers realize when there is a change in behavior and to offer assistance. In addition, training could help managers consider ways to harness constructively the help of willing and concerned co-workers to also support the struggling employee.

Toth, et al ,27 suggest that in making their decision to disclose, workers weigh each of the preceding factors in turn. Therefore, interventions need to be multi-faceted such that they create an environment in which there are more benefits to disclosure than risks. This type of environment also creates a self-reinforcing feedback loop. For example, Link, et al ,28 point out that the concealment of a mental disorder decreases contact. Yet, the lack of contact with people who are experiencing mental disorders does nothing to dispel negative perceptions whereas contact decreases stigma.29,30 By disclosing, contact is increased; this introduces a situation in which stigma can be decreased.30 For instance, these study results indicate that the positive experiences of other people in an organization introduce more incentives for others to disclose. Thus, as more people disclose and there are more positive experiences, there are increased opportunities to decrease stigma.

The results of these analyses should be considered in light of the limitations of the data. First, this sample contains a larger proportion of women than men, whereas the Ontario labor force is comprised of a greater proportion of men than women.31 The results could either underestimate or overestimate the prevalence of negative perceptions of mental disorders in the workplace if there are differences in the sexes with respect to predisposition for disclosure and prejudice against mental disorders. For instance, these study results suggest that men are more likely to be concerned about mental disorders experienced by co-workers. If the sample had a higher proportion of men, there would have been a lower proportion of respondents who did not indicate they would be concerned.

Furthermore, potential respondents may have been hesitant to respond to a survey. To the extent that this would be more likely for people experiencing mental health problems and in turn, these people were more likely to decide against disclosure, these findings would underestimate their experiences. Thus, the findings in this paper would be a conservative description of lack of disclosure among people with mental health problems.

In addition, the data were drawn from a sample of employed people in Ontario. Thus, the data are generalizable to other jurisdictions to the degree to which the employed populations within those entities are similar with respect to attitudes and policies.

Furthermore, interviews were limited to people with landline telephones. If telephone landline use excludes certain groups of workers, the results of this study will not be representative.

Finally, the responses represent intent but do not necessarily translate into action. At the time of action, intentions may no longer be consistent with action. An important next step would be to understand how closely they are correlated and the circumstances in which they are not.

In conclusion, while support could be critical for workers who are experiencing a mental disorder and who are finding work challenging, a significant proportion do not seek support at work. Part of the hesitation to ask for help involves the fear of negative repercussions. Organizations can create safe environments through their policies and by providing resources and training to managers to enable them to carry out these policies. By making it safe to disclose the need for help, incentives are created that foster help seeking. In the process, stigma as well as the burden of mental disorders in the workplace can be decreased.

Acknowledgements

Interviewing and data assembly were completed by a private research firm, Malatest and Associates.

Conflicts of Interest:

None declared.

Funding:

Data collection for the dataset used in this paper was financially supported by a grant from Lundbeck Canada with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The author gratefully acknowledges the support provided by a CIHR/PHAC Applied Public Health Chair. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation nor did the funders participate in the development of this manuscript or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Cite this article as: Dewa CS. Worker attitudes towards mental health problems and disclosure. Int J Occup Environ Med 2014;5:175-186

References

- 1.Sanderson K, Andrews G. Common mental disorders in the workforce: recent findings from descriptive and social epidemiology. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51:63–75. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Kelley D. et al. Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: mental health services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:78–89. doi: 10.1002/da.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Hees H. Incidence rates of sickness absence related to mental disorders: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:205. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewa CS, Goering P, Lin E, Paterson M. Depression-related short-term disability in an employed population. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:628–33. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewa CS, Lin E. Chronic physical illness, psychiatric disorder and disability in the workplace. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim D, Sanderson K, Andrews G. Lost productivity among full-time workers with mental disorders. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2000;3:139–46. doi: 10.1002/mhp.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewa CS, Lin E, Kooehoorn M, Goldner E. Association of chronic work stress, psychiatric disorders, and chronic physical conditions with disability among workers. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:652–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen S, Carlson G. To conceal or disclose a disabling condition? a dilemma of employment transition. J Vocational Rehab. 2003;19:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brohan E, Henderson C, Wheat K. et al. Systematic review of beliefs, behaviours and influencing factors associated with disclosure of a mental health problem in the workplace. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karasek RA, Theorell T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York, Basic Books, 1990.

- 11. Dewa CS, Lin E, Corbiere M, Shain M. Examining the Mental Health of the Working Population: Organizations, Individuals and Haystacks. In: Cairney J, Streiner D, eds. Mental Disorder in Canada: An Epidemiological Perspective. Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2010.

- 12.Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A, Sartorius N. Stigma: ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:192–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M. et al. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1328–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S. et al. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:4–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tse S. What do employers think about employing people with experience of mental illness in New Zealand workplaces? Work. 2004;23:267–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman D, Cromwell C, Aarenau D. et al. Factors Leading to Successful Work Integration of Employees Who Have Experienced Mental Illness. Employee Assistance Quarterly. 2004;19:51–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deuchert E, Kauer L, Meisen Zannol F. Would you train me with my mental illness? Evidence from a discrete choice experiment. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2013;16:67–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brohan E, Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination of mental health problems: workplace implications. Occup Med (Lond) 2010;60:414–5. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T. et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2014:1–17. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellison ML, Russinova Z, MacDonald-Wilson KL, Lyass A. Patterns and Correlates of Workplace Disclosure Among Professionals and Managers with Psychiatric Conditions. J Vocational Rehab. 2003;18:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brohan E, Henderson C, Little K, Thornicroft G. Employees with mental health problems: Survey of UK employers’ knowledge, attitudes and workplace practices. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2010;19:326–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobau R, Zack MM. Attitudes toward mental illness in adults by mental illness-related factors and chronic disease status: 2007 and 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:2078–89. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gates LB. Workplace Accommodation as a Social Process. J Occup Rehab. 2000;10:85–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA. et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2011;41:1751–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. The impact of beyondblue: the national depression initiative on the Australian public’s recognition of depression and beliefs about treatments. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:248–54. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toth KE, Dewa CS. Employee Decision-Making About Disclosure of a Mental Disorder at Work. J Occup Rehabil. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10926-014-9504-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Link BG, Cullen FT. Contact with the mentally ill and perceptions of how dangerous they are. J Health Soc Behav. 1986;27:289–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crisp A, Gelder M, Goddard E, Meltzer H. Stigmatization of people with mental illnesses: a follow-up study within the Changing Minds campaign of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2005;4:106–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg SG, Kileen MB, O’Day B. The Disclosure Conundrum: How People with Psychiatric Disabilities Navigate Employment. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2005;11:463–500. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Statistics Canada. Experienced labour force 15 years and over by occupation and sex, by province and territory (2006 Census), 2014.