Abstract

The aim of this study was to estimate whether kinematic alignment (KA) improves knee function or clinical outcomes compared with mechanical alignment (MA) in the short term after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). We searched the literature for randomized controlled trials published before January 2020 from PubMed, EMBASE, Google, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and other databases. The observation markers included “The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index,” “Knee Society Score (KSS),” “Oxford Knee Score (OKS),” “combined Knee Society Score (KSS),” “Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS),” “European Quality of Life Measure‐5 Domain‐5‐Level (EQ‐5D‐5L),” range of motion (ROM), lower limb alignment, ligament release, and complications. A total of 11 randomized controlled trial studies were included in the study. During the follow‐up of 6–24 months, the KA‐TKA group was superior to the MA‐TKA group in terms of WOMAC scores, combined KSS, KSS, knee function scores, and knee range of flexion, but there was no significant difference in EQ‐5D‐5L, KOOS, KOOS (symptoms, pain, ADL, sports, and quality of life), complications, knee range of extension, hip‐knee‐ankle (HKA) angle, tibial component slope angle, lateral distal femoral angle (LDFA) or medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA) angle between the MA‐TKA group and the MA‐TKA group (P > 0.05). Our meta‐analysis revealed that the incidence of ligament release in the MA‐TKA group was higher than that in the KA‐TKA group. This meta‐analysis shows that the KA‐TKA group had better clinical outcomes and knee range of flexion than the MA‐TKA group at short‐term follow‐up.

Keywords: Alignment, Knee joint, Meta‐analysis, Total knee arthroplasty

Although the survival rate of MA‐TKA has improved, approximately 20%–25% of patients remain unsatisfied with the outcome.Therefore, this article to evaluate whether the clinical outcome of KA‐TKA is better than that of MA‐TKA.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most widespread joint disease in the elderly, and knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is more frequent than OA of the hip or ankle 1 , 2 . It has been predicted that in 2020, OA will be the fourth most common cause of disability worldwide 3 . At present, the first choice for severe joint diseases (Kellgren–Lawrence score ≥ 3) is total knee arthroplasty (TKA), which can relieve joint pain, correct deformity, and improve joint function, and many studies have suggested that the long‐term survival rate could reach more than 90% after 15 years 4 , 5 , 6 . It has been estimated that by 2030, every year, 3.8 mn people will undergo TKA 7 . Although the survival rate of TKA has improved, approximately 20%–25% of patients remain unsatisfied with the outcome 8 .

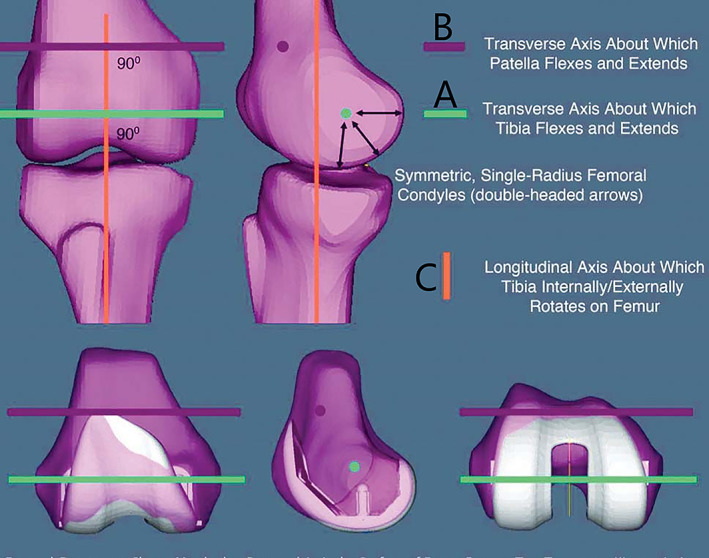

Traditional mechanical alignment (MA) has been used in TKA for more than 30 years, and it is still common worldwide. It is generally believed that a hip–knee–ankle (HKA) angle within less than 3° of the neutral mechanical axis is essential for postoperative limb recovery after TKA 9 , 10 . With the development of knee biomechanics, however, many people have assumed that MA does not entirely restore normal lower limb alignment, may alter the normal kinematics of knee motion and so contribute to some of the most serious ramifications. Some foreign scholars 11 , 12 , 13 have found that the kinetic characteristics of the normal knee are governed by three axes (Fig. 1). One is the transverse axis of the femur; during knee flexion and extension, the tibia moves around the transverse axis of the centerline of the medial and lateral condyle of the femur 14 , 15 , 16 . Another is the patellar transverse axis, a transverse axis around which the patella rotates during knee flexion and extension; its spatial position is anterior and proximal of the central transverse axis of the femur 17 , 18 . The last axis is the longitudinal axis of the tibia, which is perpendicular to the transverse axis of the femur; the tibia rotates internally and externally around the longitudinal axis of the tibia 16 , 17 , 18 . Therefore, the overall mechanical alignment takes into account the two‐dimensional alignment of the parts with the center of the femoral head, knee, and ankle. Kinematic alignment (KA) is different from mechanical alignment (MA) in that it mainly considers the three‐dimensional alignment of the components relative to the knee and involving movement in 6° of freedom (6‐DOF: front‐to‐back, proximal‐to‐distal, internally‐to‐externally, extension‐to‐flexion, varus‐to‐valgus, internal‐to‐external rotation) 12 , 13 . Based on this theory, in 2006, Howell et al. 19 proposed kinematic alignment in TKA (KA‐TKA). The primary purpose of KA‐TKA is to control the kinematics of the patella and tibia relative to the femur by restoring the above mentioned three axes of the distal femur and the proximal tibia rather than merely generating a neutral HKA angle. 12 Meanwhile, Howell et al. 12 also proposed an osteotomy and guide apparatus customized for KA‐TKA patients. However, this technique requires a highly reliable method. In other words, pre‐operative three‐dimensional scans of the articular surface of the femoral and tibia by MRI, in an MRI scan, require flexion‐extension axis (FEA) of tibia vertically to the sagittal. In addition to this, manual instrument techniques were also reported to be effective 20 . But, the following important aspects should be carefully evaluated: line of force of the lower limbs; anatomic axis of the knee; internal‐external rotation of the tibia component relative to the femur; valgus or varus degrees placement of the tibia component; anatomic axis of the knee 21 . Howell et al. 22 tested two methods for this purpose, and found that the accuracy was similar with and without Patient Specific Cutting Blocks. Some studies 19 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 have shown that KA‐TKA is more likely to restore normal knee kinematics and that its clinical outcome is quite favorable compared with MA‐TKA. And they consistently concluded that KA‐TKA could significantly improve patient's quality of life, higher mean flexion range angle, and reduced the prevalence of pain, joint stiffness, and instability 28 . However, KA‐TKA has some potential problems: an increased risk of patellar instability and polyethylene wear 29 , 30 .

Fig. 1.

The kinetic characteristics of normal knee are governed by three axes. (Photo credit: Dossett HG, Swartz GJ, Estrada NA, et al. 13

While relevant meta‐analyses have been published in recent years, these studies included randomized controlled trials, case reports, and systematic reviews 27 , 31 . Two systematic reviewss 27 , 31 have analyzed the kinematic and mechanical alignment techniques in TKA. These two meta‐analysess 27 , 31 included retrospective observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Both authors agree that the KA‐TKA provided better functional outcomes in addressing pain and improving function. Waterson et al. 32 have also analyzed 71 KOA patients undergoing TKA in which 36 patients underwent kinematic alignment treatment and 35 patients received mechanical alignment. The results showed that the two groups had similar function 1year post‐operatively. Another recent randomized controlled trial showed that the KA‐TKA offered better pain relief and higher mean flexion range angle than the MA‐TKA at two years 33 . As the quality of data in these studies is often limited, differences in results exist. It is still uncertain whether the benefits of KA‐TKA are superior to those of MA‐TKA. Therefore, we systemically analyzed the available data after searching the literature for randomized controlled trials to evaluate whether the clinical outcome of KA‐TKA is better than that of MA‐TKA.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

This meta‐analysis method was based on the Cochrane Collaboration standard. We searched the literature database for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published before January 2020. The databases that were searched included PubMed, EMBASE, Google, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. The retrieval strategy was performed by the method of free words combined with the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). The literature search was conducted using the keywords “Total Knee Arthroplasty,” “Kinematic Alignment,” “Kinematic,” “Mechanical Alignment,” “Mechanical,” and “biomarker” using Boolean operators (AND), (OR), and (NOT). Literature was retrieved without restricting the language.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Criteria for inclusion: (i) randomized controlled trials; (ii) comparisons of clinical results between KA‐TKA and MA‐TKA in total knee arthroplasty; (iii) primary knee replacement surgery; (iv) observation indexes include “The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index,”, “Knee Society Score (KSS),”“Oxford Knee Score (OKS),” “combined Knee Society Score (KSS),” “Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS),” ”EQ‐5D‐5L,” range of motion (ROM), lower limb alignment, ligament release, and complications; and v) studies published in English.

Criteria for exclusion: (i) basic research or cadaver study; and (ii) inaccessible data or full‐text.

Data Extraction

Data from the studies from all selected articles were extracted independently by two of the authors using a data extraction template, which was designed before the database searches. From each study, first author, years, type of study and surgery, sample size, follow‐up time, and clinical outcome were extracted from the literature. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion and consensus or consultation with other authors in cases of disagreement. If the data from a study was missing, insufficient, or vague, we contacted the author or corresponding authors by email or telephone to retrieve further information.

Quality Evaluation

Literature quality was evaluated independently by two of the authors with the Cochrane Collaboration Network risk evaluation tool. The risk of bias for each indicator was divided into three levels: “low,” “high,” and “unclear.” If we obtained more than 10 articles, a funnel chart or Eggers regression test was used to assess publication bias.

Observation Indexes

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)

The WOMAC is a validated questionnaire to evaluate lower extremity osteoarthritis and joint replacement. The WOMAC questionnaire produces three subscale scores (pain, stiffness, and physical function) and a total score. Patients are asked to answer each question about the severity of pain, stiffness, or behavioral difficulties experienced in the previous 48 hours. There are five response options ranging from “none” to “extreme” to choose. A response of “none” was scored as 0,”mild” as 1, “moderate” as 2, “severe” as 3, and “extreme” as 4. The scores of the questions in each subscale were summed together to get scores for pain, stiffness, and physical function. A lower subscale score indicates less pain, less stiffness, or better physical function. A total score of < 70 is considered a severe score, 21–48 is moderate, <21 is mild.

Knee Society Score (KSS)

The KSS is a condition‐specific validated questionnaire widely used to evaluate the functional capabilities of the knee joint before and after total knee arthroplasty. The scoring system consists of two parts. One part is the knee score. The assessment includes pain (maximum 50 points), stability (maximum 25 points), total range of flexion (maximum 25 points), and other items (varus, valgus, extension delay, and flexion contracture). The other part is the function score. The assessment includes walking distance (maximum 50 points), ability to climb stairs (maximum 50 points), and the use of walking aids. The highest score for each part is 100 points, and a higher score means better knee function. The evaluation result score is rated as four levels: 80–100 points, 70–79 points, 60–69 points, <60 points.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of all extracted data was carried out using Review Manager 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK), with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated by calculating the I 2. If the I 2 was greater than 50%, it was considered high heterogeneity, and a random‐effects model was chosen to analyze the data; otherwise, the fixed‐effects model was applied. Enumerated data were presented as the risk ratio (RR) or odds ratio (OR) and 95%CI, while continuous data were presented as the weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95%CI as a statistical measure of the curative effect. We attempted to use a funnel plot to evaluate the publication bias; a symmetrical funnel plot may indicate a low publication bias, while an asymmetric funnel plot may indicate possible publication bias.

Results

Literature Search Results and Study Characteristics

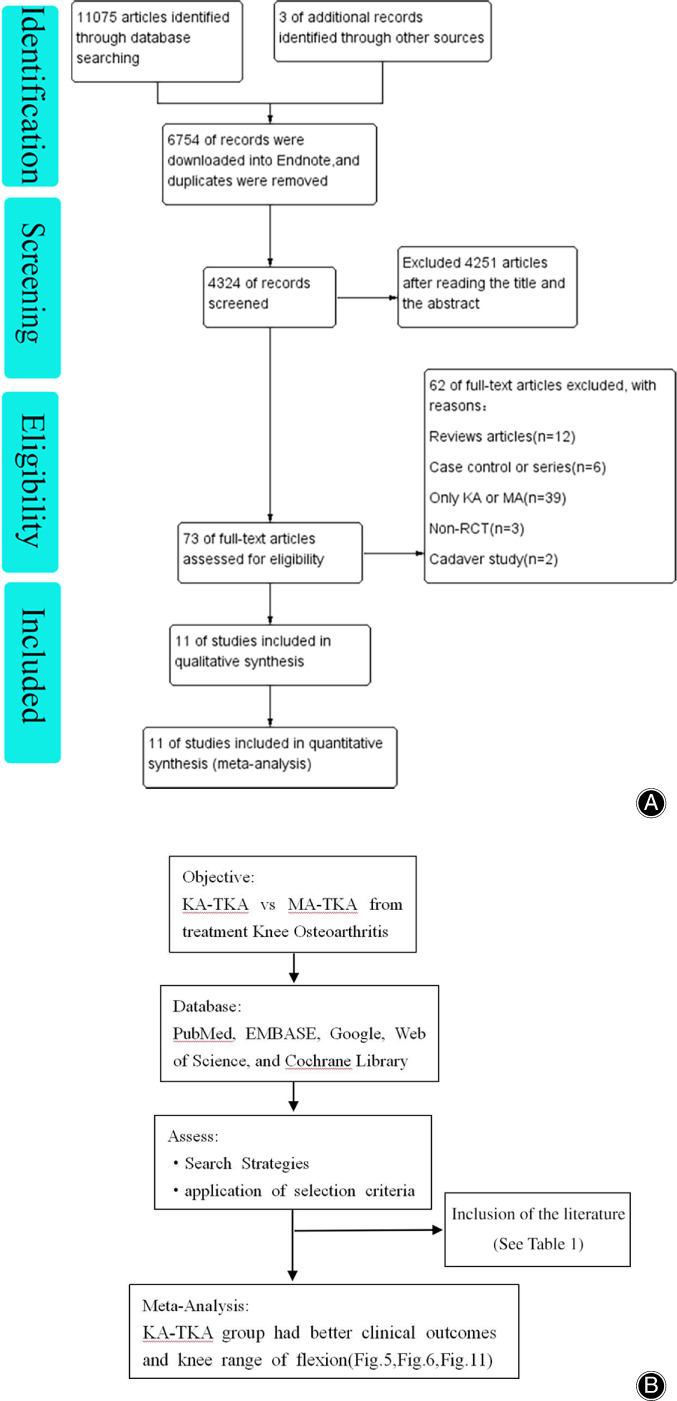

We retrieved 11,075 papers from the databases; 6754 duplicates were removed by EndNote X9.1 software (Fig. 2). This left 4324 articles. Next, 4251 articles were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts, and the remaining 73 articles were retained for further evaluation by reading the full texts. Of these articles, 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) 13 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 were included, with a total of 553 patients in the KA‐TKA group and 550 patients in the MA‐TKA group. The literature guide search and results are shown in Fig. 2B. The basic information of the 11 included articles is shown in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

(A) Flow chart of literature processing. (B) The literature guide search and results.

TABLE 1.

The basic information of the 11 RCT studies

| Authors | Year | Study design | Total patients | Sample size (knees) | Follow‐up times (months) | Measurement index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA | MA | ||||||

| MacDessi et al. 34 | 2020 | RCT | 128 | 70 | 68 | 12 | Operative time, FJS‐12, KOOS, HKA angle, LDFA, MPTA, KOOS, EQ‐5D‐5L |

| McEwen et al. 35 | 2020 | RCT | 82 | 41 | 41 | 24 | Tibial component slope angle, Femoral rotation angle, Ligament release,KOOS,OKS,FJS‐12,HKA angle, LDFA, MPTA, Extension/Flexion range |

| Yeo et al. 36 | 2019 | RCT | 60 | 30 | 30 | 8.0 years | WOMAC, KSS, Flexion range |

| Laende et al. 37 | 2019 | RCT | 47 | 24 | 23 | 24 | Ligament release, UCLA, OKS, HKA angle, MPTA |

| Young et al. 38 | 2017 | RCT | 99 | 49 | 50 | 24 | Tibial component slope angle, Femoral rotation angle, Ligament release,WOMAC,KSS,OKS,FJS‐12,HKA angle,LDFA,MPTA,EQ‐5D‐5L,Flexion range |

| Calliess et al. 39 | 2017 | RCT | 200 | 100 | 100 | 12 | Tibial component slope angle, WOMAC, KSS, HKA angle, LDFA, MPTA |

| Waterson et al. 32 | 2016 | RCT | 86 | 36 | 35 | 12 | KSS,UCLA,KOOS,EQ‐5D‐5L,Flexion range |

| Dossett et al. 33 | 2014 | RCT | 120 | 60 | 60 | 24 | WOMAC,KSS,OKS,HKA angle,LDFA,MPTA,Extension/Flexion range |

| Matsumoto et al. 41 | 2017 | RCT | 60 | 30 | 30 | 12 | KSS,Extension/Flexion range |

| Dossett et al. 13 | 2012 | RCT | 120 | 41 | 41 | 6 | Operative time, WOMAC, KSS, OKS, HKA angle, Extension/Flexion range |

| Claudio et al. 40 | 2015 | RCT | 144 | 72 | 72 | 6 | KSS |

FJS‐12, Forgotten Joint Score‐12; LDFA, Lateral distal femoral angle; MPTA, Medial proximal tibial angle; UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles Activity Score.

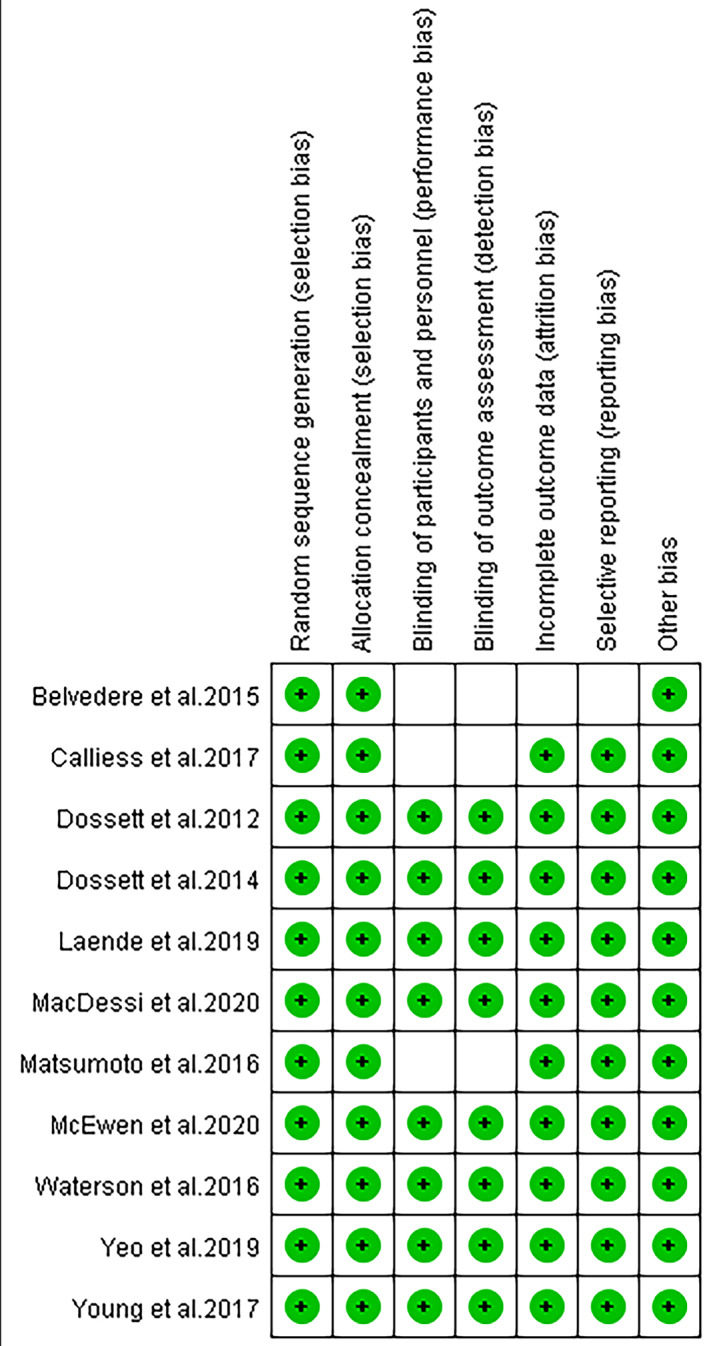

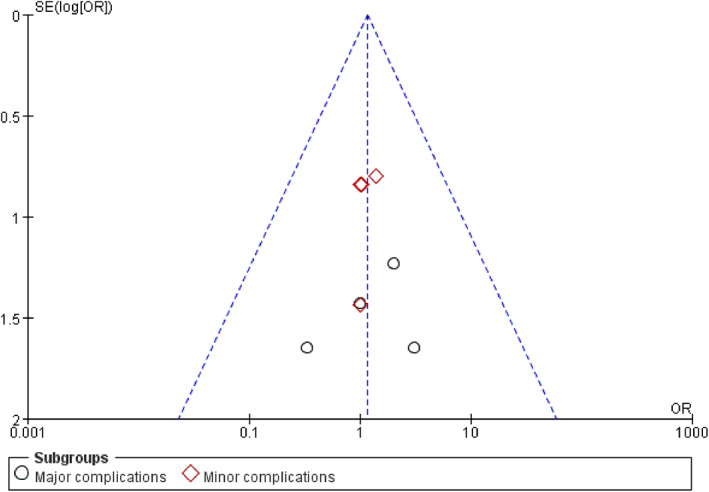

Risk‐of‐bias and Publication Bias Assessment

The 11 papers included were evaluated for risk of bias according to the seven aspects in Fig. 3, which shows that all the RCT articles had a low risk of bias. The symmetrical funnel plot may indicate low publication bias (Fig. 4).

Fig 3.

Eleven articles underwent Risk‐of‐Bias Assessment summary.

Fig. 4.

The funnel plot for the symmetrical may indicate a low publication bias.

Clinical Outcomes

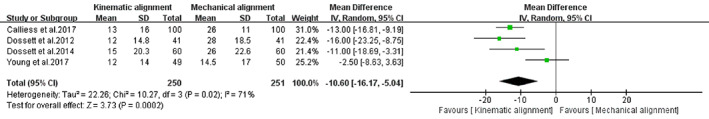

Five randomized controlled trials 13 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 with a total of 599 patients evaluated WOMAC scores. We detected high heterogeneity between the KA‐TKA and MA‐TKA groups (I 2 = 93%). We found that one of these studies 36 reported the results in the long term (8‐year follow‐up), while other studies reported a short‐term follow‐up. We excluded this article from our meta‐analysis for further analysis. The meta‐analysis result was heterogeneous (I 2 = 71%), so the random‐effects model was used for further analysis. The results showed that the WOMAC score of the MA‐TKA group was higher than that of the KA‐TKA group [MD = ‐10.60, 95%CI (−16.17, −5.04), P = 0.0002, Fig. 5].

Fig. 5.

The forest plot for WOMAC (0–96 best–worst).

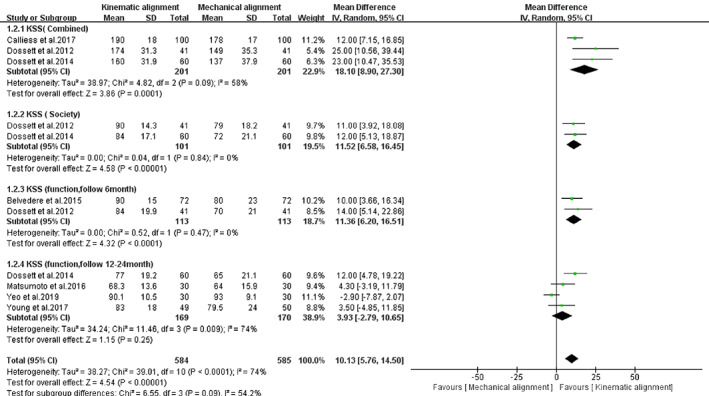

Knee joint function and pain scores were evaluated by the KSS and OKS. The total knee scores of the KA‐TKA group were better than those of the MA‐TKA group, and the differences were statistically significant [I 2 = 74%, MD = 10.13, 95%CI (5.76, 14.50), P < 0.00001, Fig. 6]. Three trials with a total of 402 patients evaluated the combined KSS. The random‐effects model was used instead of a fixed‐effects model due to the high heterogeneity (I 2 = 84%) of the combined KSS. The combined KSSs were better in the KA‐TKA group than in the MA‐TKA group, and the difference between the groups reached statistical significance [MD = 18.10, 95%CI (8.90, 27.30), P = 0.0001, Fig. 6].

Fig. 6.

The forest plot for Combined Knee Society score (KSS, 0–200 worst–best), Knee Society Score(0–100 worst–best), Knee function Score(0–100 worst–best).

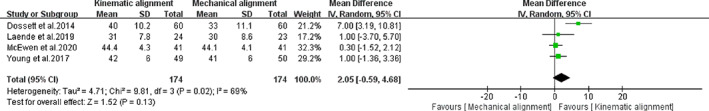

Two trials 36 , 38 with a total of 238 patients evaluated the KSS. The results indicated that the mean scores of the KA‐TKA group were higher than those of the MA‐TKA group [MD = 11.52, 95%CI (6.58, 16.45), P < 0.00001, Fig. 6]. Six trials 13 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 40 with a total of 565 patients evaluated the knee function score. According to the different scoring times, 6 months 13 , 40 and 12–24 months, 33 , 36 , 38 the included studies were divided into two subgroup analyses. Two trials 13 , 40 followed up 226 enrolled patients for 6 months, and based on our findings, the KA‐TKA group had higher mean scores than the MA‐TKA group [MD = 11.36, 95%CI (6.20, 16.51), P < 0.0001, Fig. 6]. Four trials 33 , 36 , 38 followed up 339 enrolled patients for 12–24 months, and the results showed that the two groups had similar mean scores [MD = 3.93, 95%CI (−2.79, 110.65), P = 0.25, Fig. 6]. Five trials 13 , 33 , 35 , 37 , 38 with a total of 430 patients evaluated OKS. However, one study 13 calculated the scores differently from the others, and hence, we excluded this article from this study. The meta‐analysis result was heterogeneous (I 2 = 69%), so the random‐effects model was used for further analysis. The results showed that the two groups had similar mean scores [MD = 2.05, 95%CI (−0.59, 4.68), P = 0.13, Fig. 7].

Fig. 7.

The forest plot for Oxford Knee Score(0–48 worst–best).

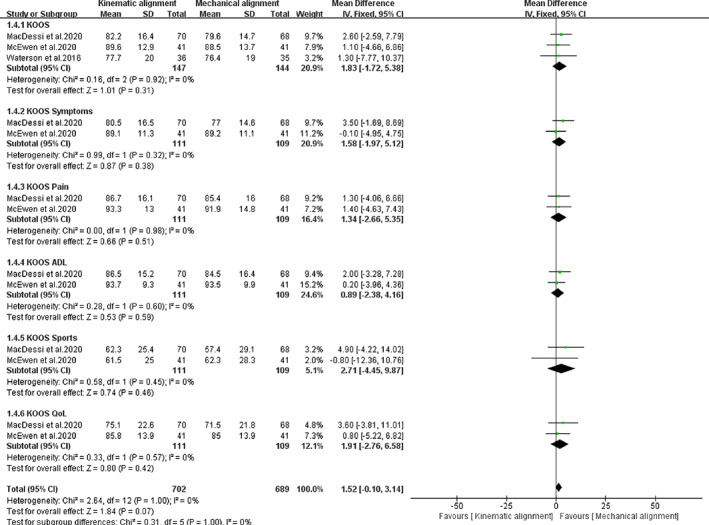

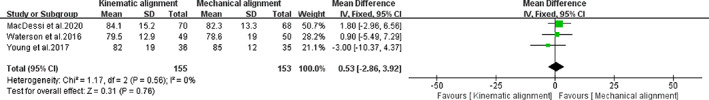

Quality of life (QoL) was evaluated using KOOS and EQ‐5D‐5L. Three trials with a total of 291 patients evaluated KOOS. The meta‐analysis result showed low heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%), and hence, a fixed‐effects model was used for further analysis. Figure 8 shows that these two groups had similar mean scores in terms of KOOS [MD = 1.83, 95%CI (−1.72, 5.38), P = 0.31], KOOS symptoms [MD = 1.58, 95%CI (−1.97, 5.12), P = 0.38], KOOS pain [MD = 1.34, 95%CI (−2.66, 5.35), P = 0.51], KOOS ADL [MD = 0.89, 95%CI (−2.38, 4.16), P = 0.59], KOOS sports [MD = 2.71, 95%CI (−4.45, 9.87), P = 0.46], and KOOS QoL [MD = 1.83, 95%CI (−2.76, 56.58), P = 0.42]. Three trials with a total of 291 patients evaluated EQ‐5D‐5L. The meta‐analysis result showed low heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%), and hence, a fixed‐effects model was used for further analysis. The results showed that the two groups had similar mean scores [MD = 0.53, 95%CI (−2.86, 3.92), P = 0.76, Fig. 9].

Fig. 8.

The forest plot for knee injury and osteoarthritis score (KOOS, 0‐100 worst–best).

Fig. 9.

The forest plot for EQ‐5D‐5L.

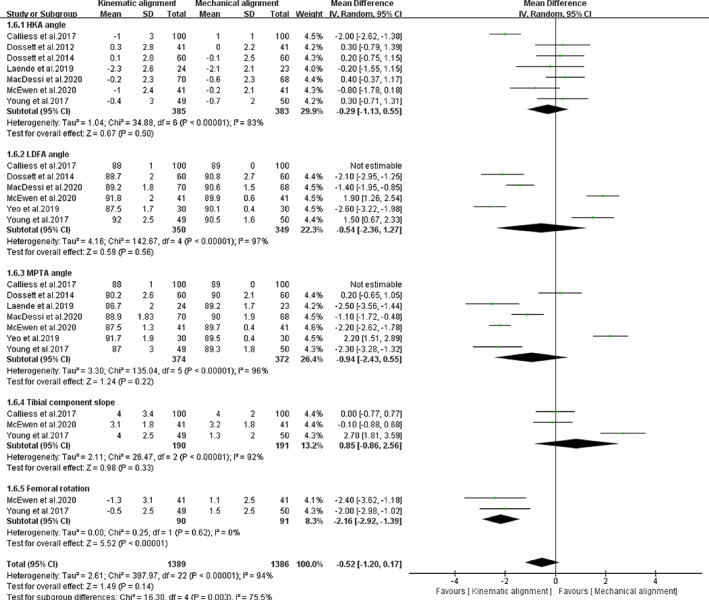

Lower Limb Alignment

Basic lower limb alignment measurements should include the HKA angle, tibial component slope angle, femoral component rotation to sulcus line angle, LDFA, and MPTA angle. The random‐effects model was used instead of a fixed‐effects model since there was heterogeneity. Figure 10 shows that the two groups had similar mean scores in terms of HKA angle [I 2 = 83%, MD = ‐0.29, 95%CI (−1.13, 0.55), P = 0.50], tibial component slope angle [I 2 = 92%, MD = 0.85, 95%CI (−0.86, 2.56), P = 0.22], LDFA angle [I 2 = 97%, MD = ‐0.54, 95%CI (−2.36, 1.27), P = 0.38], and MPTA angle [I 2 = 96%, MD = 0.94, 95%CI (−2.43, 0.55), P = 0.22]. The results of two trials with 181 patients showed that the femoral component internal rotation to sulcus line angles of the two groups were different [I 2 = 0%, MD = ‐2.16, 95%CI (−2.92, −1.39), P<0.00001, Fig. 10]. From the data in Fig. 8, the rotation angle of the KA‐TKA group still had a varus alignment, whereas the MA‐TKA group presented with a valgus pattern.

Fig. 10.

The forest plot for HKA, LDFA, MPTA, tibial component slope and femoral rotation angle.

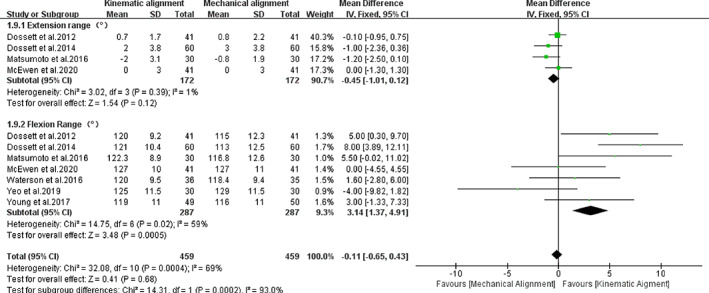

ROM

Our review found a total of seven relevant studies, including four studies 13 , 33 , 35 involving extension range angle and seven studies involving flexion range angle 13 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 . As seen from Fig. 11, the difference in extension range angle did not reach statistical significance [I 2 = 1%, MD = ‐0.45, 95%CI (−1.01, 0.12), P = 0.12] but the difference in flexion range angle did [I 2 = 59%, MD = 3.14, 95%CI (1.37, 4.91), P = 0.0005]. Furthermore, the KA‐TKA group had a higher mean flexion range angle than the MA‐TKA group (P = 0.0005).

Fig. 11.

The forest plot for extension/flexion range of knee.

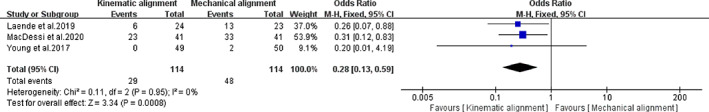

Ligament Release and Complications

Three articles 35 , 37 , 38 with 228 enrolled patients reported ligament release. Intraoperatively, 77 cases of ligament releases were recorded, with 29 cases in the KA‐TKA group and 48 cases in the MA‐TKA group. The fixed‐effects model was used instead of a random‐effects model due to the low heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%). The incidence of ligament release was lower in the KA‐TKA group than in the MA‐TKA group [MD = 0.28, 95%CI (0.13, 0.59), P = 0.0008, Fig. 12].

Fig. 12.

The forest plot for ligament release.

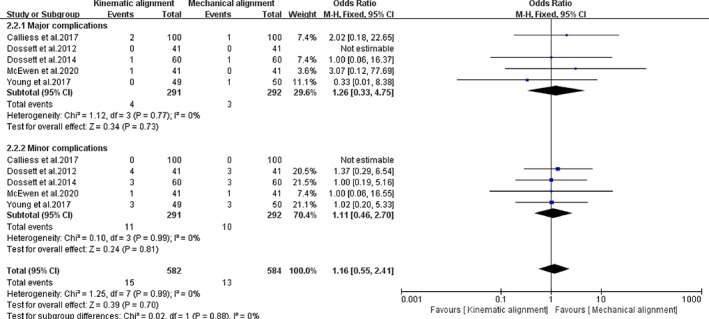

Of the 11 studies, five studies 13 , 33 , 35 , 38 , 39 provided data regarding complications (KA‐TKA: 15/582; MA‐TKA: 13/584). There was no statistical significance between the two groups (I 2 = 0%, MD = 1.16, 95%CI (0.55, 2.41), P = 0.70, Fig. 13). All the complications were clustered into two subgroups: subgroup 1 (major complications) and subgroup 2 (minor complications). Figure 13 shows that these two groups had the same result in terms of major complications [I 2 = 0%, MD = 1.26, 95%CI (0.33,4.75), P = 0.73] and minor complications [I 2 = 0%, MD = 1.11, 95%CI (0.46,2.56), P = 2.70].

Fig. 13.

The forest plot for complication. Major complications are defined as revision of knee joint or removal of prosthesis caused by various reasons; and other additional surgery treatments were classified as minor complications.

Discussion

Results on the Meta‐Analysis

The 11 studies (RCTs) that fulfilled the inclusion criteria included 1103 participants: 553 patients in the KA‐TKA group and 550 patients in the MA‐TKA group. Furthermore, follow‐up ranged from 6 months–8 years. Most of the literature reported that the patients were followed up for 6–24 months. The results of the KA‐TKA group were better than those of the MA‐TKA group in terms of the WOMAC score, combined KSS, KSS, knee function score, and knee range of flexion, while the EQ‐5D‐5L, KOOS, KOOS (symptoms, pain, ADL, sports, and QoL), complications, knee range of extension, HKA angle, tibial component slope angle, LDFA, and MPTA angle in the KA‐TKA group were not significantly different from those in the MA‐TKA group. The incidence of ligament release in the KA‐TKA (29/144) group was lower than that in the MA‐TKA (48/144) group, and the difference was statistically significant.

Functional Outcome After KA‐TKA

Although the survival rate and the clinical and functional outcomes of TKA are very good overall, approximately 20%–25% of patients remain unsatisfied with the outcome 8 . There are undoubtedly many reasons, but the two main reasons are as follows. (i) Reports have indicated that 98% of normal limb femoral and tibial mechanical axes are not in a straight line and that 76% of normal limbs exceed the range of 3° of the neutral mechanical axis 16 . Bellemans et al. 42 studied 250 young adults without arthritis and showed that the rate of constitutional varus knees was 24.6%, with a rate of 32.0% for males and 17.0% for females. If these patients need to be treated by MA‐TKA, the clinical outcomes of patients will still be poor after surgery. (ii) MA‐TKA does not entirely restore knee joint kinematics, kinetic characteristics can irritate the soft tissue, and imbalance of the knee joint has attracted the full attention of domestic and foreign scholars. The proposed kinematic alignment is based on the concept of the kinematic axes of the knee and their relationship to the femoral condyles 14 , 15 . KA‐TKA does not restore the HKA angle of the limb to neutral, it mainly considers the three‐dimensional alignment of the components relative to the knee, which may lower the frequency of ligament release and improve clinical effectiveness 19 , 36 , 37 , 38 . Recently, two RCTs compared KA vs MA in TKA, and KA‐TKA reduced the incidence of ligament release 35 , 37 . Our meta‐analysis revealed that the rate of ligament release in MA‐TKA was higher than that in KA‐TKA (P = 0.0008). Consistent with findings in previous studies 27 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , we found that the KA‐TKA group had better knee function outcomes than the MA‐TKA group in terms of the WOMAC score, KSS, combined KSS, and KSS.

Complications and Survival

Although the goal of KA‐TKA is to restore normal knee kinematics or prearthritic kinematics and restore the patient to previous functional levels, the concern for increased risk of patellofemoral instability and polyethylene wear was raised 29 , 30 , 43 , 44 , 45 . Ishikawa et al. 46 found that patients with more significant femoral rollback and external rotation of the femur can obtain better restoration of the motion of tibia flexion‐extension after KA‐TKA. Our updated meta‐analysis found that the KA‐TKA group had a higher mean flexion range angle than the MA‐TKA group (P = 0.0005). However, Ishikawa et al. 46 expressed concern about varus alignment of the tibial prosthesis, which can increase the risk of polyethylene wear, leading to reduced prosthesis survival, and which also increases contact stress at the patellofemoral joint and may cause patellofemoral joint instability. Our meta‐analysis reported three patients with patellar instability: two patients in the KA‐TKA group 13 , 38 and one patient in the MA‐TKA group 38 . The results showed that the two groups had similar rates of complications (KA‐TKA: 15/582, MA‐TKA: 13/584, P = 0.70). Howell et al. 24 prospectively followed 214 knees subjected to KA‐TKA, and the mean follow‐up was 38 months (31–43 months). There has been great interest in investigating varus (>3°) or valgus (<‐3°) knee alignment, and there was no polyethylene wear or loosening leading to loosening of the revision prosthesis in comparison with alignment of the HKA angle in range (0° ±3°). Another study showed that after patients underwent the KA‐TKA, 80% presented with varus alignment of the tibial component, and 70% had a varus alignment of the limb. However, varus alignment of the tibial component and limb did not adversely affect implant survival or function during the follow‐up periods. Of the patients whose follow‐up was 3 to 8 years (mean, 6.3 years), only two cases of loosening of the prosthesis were considered failures; the survival rate was 97.5% and the revision rate was 0.4% 47 . Howell et al. 48 show that the overall survival rate of prostheses hold on pleasurable,the 10‐years survival rate of approximately 97.5%. Yeo et al. 36 reported the follow‐up of patients after KA‐TKA and MA‐TKA for 8 years, and they obtained similar clinical and radiological results. Thus, they suggested that the increased risk of surgical failure after KA‐TKA may not hold. However, KA‐TKA as a new option for the treatment of patients with KOA lacks long‐term results, so it is necessary to collect detailed observations, perform studies with longer follow‐up and data analysis, and scientifically evaluate the new treatment methods.

Limitations

However, some limitations still existed in this study. First, high heterogeneity existed in some comparisons. Although we used several subgroups, heterogeneity was still present in some results, and we failed to thoroughly explain the heterogeneity. Second, although the short‐term clinical effect after KA‐TKA has been evaluated, there is a lack of long‐term follow‐up results for the survival rate of the prosthesis. Finally, the chief limitation of this study was the small sample size; thus, a large sampler size, more rigorous RCTs, and longer follow‐up supporting these results will be needed in the future.

Conclusion

This meta‐analysis shows that the KA‐TKA had better outcomes than the MA‐TKA on WOMAC score, Combined KSS, KSS (Society and Function) score, and knee range of flexion at short‐term follow‐up.

Disclosure

The authors declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank AJE for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Goldring MB, Goldring SR. Osteoarthritis. J Cell Physiol, 2007, 213: 626–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roque VA, Agre M, Barroso J, Brito I. Managing knee ostheoarthritis: efficacy of hyaluronic acid injections. Acta Reumatol Port, 2013, 38: 154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ, 2003, 81: 646–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abdel MP, Ollivier M, Parratte S, Trousdale RT, Pagnano MW. Effect of postoperative mechanical Axis alignment on survival and functional outcomes of modern Total knee arthroplasties with cement: a concise follow‐up at 20 years. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2018, 100: 472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parratte S, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Effect of postoperative mechanical Axis alignment on the fifteen‐year survival of modern, cemented Total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2010, 92: 2143–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonner TJ, Eardley WG, Patterson P, Gregg PJ. The effect of post‐operative mechanical axis alignment on the survival of primary total knee replacements after a follow‐up of 15 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2011, 93: 1217–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern M. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 1990 through 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2005, 87: 1487–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KDJ. Patient satisfaction after Total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2010, 468: 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lombardi AV Jr, Berend KR, Ng VY. Neutral mechanical alignment: a requirement for successful TKA: affirms. Orthopedics, 2011, 34: e504–e506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma DS, Wang ZW, Wen L, et al Improving Tibial component coronal alignment during Total knee arthroplasty with the use of a double‐check technique. Orthop Surg, 2019, 11: 1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ma CB, Lee K, Schrumpf MA, Majumdar S. Analysis of three‐dimensional in vivo knee kinematics using dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Oper Tech Orthop, 2005, 15: 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roth JD, Howell SM, Hull ML. Kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty limits high tibial forces, differences in tibial forces between compartments, and abnormal tibial contact kinematics during passive flexion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2018, 26: 1589–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dossett HG, Swartz GJ, Estrada NA, LeFevre GW, Kwasman BG. Kinematically versus mechanically aligned Total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics, 2012, 35: E160–E169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eckhoff D, Hogan C, DiMatteo L, Robinson M, Bach J. Difference between the epicondylar and cylindrical axis of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2007, 461: 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hollister AM, Jatana S, Singh AK, Sullivan WW, Lupichuk AG. The axes of rotation of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1993, 290: 259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eckhoff DG, Bach JM, Spitzer VM, et al Three‐dimensional mechanics, kinematics, and morphology of the knee viewed in virtual reality. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2005, 87: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coughlin KM, Incavo SJ, Churchill DL, Beynnon BD. Tibial axis and patellar position relative to the femoral epicondylar axis during squatting. J Arthroplasty, 2003, 18: 1048–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iranpour F, Merican AM, Dandachli W, Amis AA, Cobb JP. The geometry of the trochlear groove. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2010, 468: 782–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howell SM, Kuznik K, Hull ML, Siston RA. Results of an initial experience with custom‐fit positioning Total knee arthroplasty in a series of 48 patients. Orthopedics, 2008, 31: 857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Howell SM, Papadopoulos S, Kuznik KT, Hull ML. Accurate alignment and high function after kinematically aligned TKA performed with generic instruments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2013, 21: 2271–2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Christen B, Heesterbeek P, Wymenga A, Wehrli U. Posterior cruciate ligament balancing in total knee replacement: the quantitative relationship between tightness of the flexion gap and tibial translation. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2007, 89: 1046–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Howell SM, Hull ML. Principles of Kinematic Alignment in Total Knee Arthroplasty with and without Patient Specific Cutting Blocks (OtisKnee), 5th edn Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2011; 1255–1268. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Metcalfe AJ, Stewart C, Postans N, Dodds AL, Roberts AP. The effect of osteoarthritis of the knee on the biomechanics of other joints in the lower limbs. Bone Joint J, 2013, 95: 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Howell SM, Howell SJ, Kuznik KT, Cohen J, Hull ML. Does a kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty restore function without failure regardless of alignment category. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2013, 471: 1000–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schiraldi M, Bonzanini G, Chirillo D, de Tullio V. Mechanical and kinematic alignment in total knee arthroplasty. Ann Transl Med, 2016, 4: 130–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee YS, Howell SM, Won YY, et al Kinematic alignment is a possible alternative to mechanical alignment in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2017, 25: 3467–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Y, Wang S, Wang Y, Yang M. Does kinematic alignment improve short‐term functional outcomes after Total knee arthroplasty compared with mechanical alignment? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Knee Surg, 2018, 31: 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Howell SM, Rogers SL. Method for quantifying patient expectations and early recovery after total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics, 2009, 32: 884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klatt BA, Goyal N, Austin MS, Hozack WJ. Custom‐fit Total knee arthroplasty (OtisKnee) results in malalignment. J Arthroplasty, 2008, 23: 26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ritter MA, Davis KE, Meding JB, Pierson JL, Berend ME, Malinzak RA. The effect of alignment and BMI on failure of Total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2011, 93: 1588–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoon JR, Han S, Jee M, Shin Y. Comparison of kinematic and mechanical alignment techniques in primary total knee arthroplasty. Medicine (Abingdon), 2017, 96: e8157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Waterson HB, Clement ND, Eyres KS, Mandalia VI, Toms AD. The early outcome of kinematic versus mechanical alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomised control trial. Bone Joint J, 2016, 98: 1360–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dossett HG, Estrada NA, Swartz GJ, LeFevre GW, Kwasman BG. A randomised controlled trial of kinematically and mechanically aligned total knee replacements: two‐year clinical results. Bone Joint J, 2014, 96: 907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. MacDessi SJ, Griffiths‐Jones W, Chen DB, et al Restoring the constitutional alignment with a restrictive kinematic protocol improves quantitative soft‐tissue balance in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Bone Joint J, 2020, 102: 117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McEwen PJ, Dlaska CE, Jovanovic IA, Doma K, Brandon BJ. Computer‐assisted kinematic and mechanical Axis Total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial of bilateral simultaneous surgery. J Arthroplasty, 2020, 35: 443–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yeo JH, Seon JK, Lee DH, Song EK. No difference in outcomes and gait analysis between mechanical and kinematic knee alignment methods using robotic total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2019, 27: 1142–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Laende EK, Richardson CG, Dunbar MJ. A randomized controlled trial of tibial component migration with kinematic alignment using patient‐specific instrumentation versus mechanical alignment using computer‐assisted surgery in total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J, 2019, 101: 929–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Young SW, Walker ML, Bayan A, Briant‐Evans T, Pavlou P, Farrington B. The Chitranjan S. Ranawat award: no difference in 2‐year functional outcomes using kinematic versus mechanical alignment in TKA: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2017, 475: 9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Calliess T, Bauer K, Stukenborg‐Colsman C, Windhagen H, Budde S, Ettinger M. PSI kinematic versus non‐PSI mechanical alignment in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2017, 25: 1743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Claudio B, Tamarri S, Ensini A, et al Better joint motion and muscle activity are achieved using kinematic alignment than neutral mechanical alignment in total knee replacement. Gait Post, 2015, 42: S19–S20. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Matsumoto T, Takayama K, Ishida K, Hayashi S, Hashimoto S, Kuroda R. Radiological and clinical comparison of kinematically versus mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J, 2017, 99: 640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bellemans J, Colyn W, Vandenneucker H, Victor J. The Chitranjan Ranawat award: is neutral mechanical alignment Normal for all patients?: the concept of constitutional Varus. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2012, 470: 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nedopil AJ, Howell SM, Hull ML. What clinical characteristics and radiographic parameters are associated with patellofemoral instability after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop, 2017, 41: 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nedopil AJ, Howell SM, Hull ML. What mechanisms are associated with tibial component failure after kinematically‐aligned total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop, 2017, 41: 1561–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cucchi D, Menon A, Aliprandi A, et al Patient‐specific instrumentation affects rotational alignment of the femoral component in Total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Orthop Surg, 2019, 11: 75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ishikawa M, Kuriyama S, Ito H, Furu M, Nakamura S, Matsuda S. Kinematic alignment produces near‐normal knee motion but increases contact stress after total knee arthroplasty: a case study on a single implant design. Knee, 2015, 22: 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Howell SM, Papadopoulos S, Kuznik K, Ghaly LR, Hull ML. Does varus alignment adversely affect implant survival and function six years after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop, 2015, 39: 2117–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Howell SM, Shelton TJ, Hull ML. Implant survival and function ten years after Kinematically aligned Total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 2018, 33: 3678–3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]