Abstract

A survey of bambusicolous fungi in Bijiashan Mountain Park, Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China, revealed several Arthrinium-like taxa from dead sheaths, twigs, and clumps of Bambusa species. Phylogenetic relationships were investigated based on morphology and combined analyses of the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), large subunit nuclear ribosomal DNA (LSU), beta tubulin (β-tubulin), and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef 1-α) gene sequences. Based on morphological characteristics and phylogenetic data, Arthrinium acutiapicum sp. nov. and Arthrinium pseudorasikravindrae sp. nov. are introduced herein with descriptions and illustrations. Additionally, two new locality records of Arthrinium bambusae and Arthrinium guizhouense are described and illustrated.

Keywords: Apiosporaceae, bamboo, fungal taxonomy, new locality records, novel species

Introduction

Arthrinium Kunze is accommodated in Apiosporaceae, Xylariales, which is morphologically different from other xylariaceous genera by the presence of basauxic conidiophores and dark, aseptate, globose to lenticular conidia with a hyaline rim or germ slit (Minter, 1985; Petrini and Müller, 1986; Singh et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2018; Pintos et al., 2019). Basauxic conidiophores simply mean elongation of conidiogenous cells from the basal growing point after formation of a single, terminal blastic conidium at its apex (Cole, 1986).

Arthrinium species are distributed worldwide in various hosts as endophytes, epiphytes, or saprobes, as well as plant pathogens on some commercial crops and ornamentals (Agut and Calvo, 2004; Ramos et al., 2010; Crous and Groenewald, 2013; Sharma et al., 2014; Senanayake et al., 2015; Wijayawardene et al., 2020). Also, species of Arthrinium (Schmidt and Kunze, 1817) inhabit a wide range of substrates, i.e., air, soil debris, lichens, marine algae (Agut and Calvo, 2004; Senanayake et al., 2015; Dai et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2019), and even human tissues (Sharma et al., 2014). The genus Arthrinium morphologically differs from other xylariaceous anamorphic genera by the presence of basauxic conidiogenous cells which arise from conidiophore mother cells (Schmidt and Kunze, 1817; Minter, 1985).

The commonly reported diseases by Arthrinium species are kernel blight of barley and brown culm streak of Phyllostachys praecox by A. arundinis, damping-off of wheat by A. sacchari, and culm rot of bamboos and Phyllostachys viridis by A. phaeospermum (Martínez-Cano et al., 1992; Mavragani et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016). Additionally, the causative agent of cutaneous infections of humans has been reported as A. phaeospermum (Rai, 1989; Zhao et al., 1990; De Hoog et al., 2000; Crous and Groenewald, 2013). Some Arthrinium species produce bioactive compounds with pharmacological and medicinal properties (Hong et al., 2015), while some produce industrially important enzymes (Shrestha et al., 2015). Crous and Groenewald (2013) reviewed the genus Arthrinium based on morphology and multigene phylogeny. There are several subsequent studies providing additions to the genus (Singh et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2014; Crous et al., 2015; Senanayake et al., 2015; Dai et al., 2016, 2017; Hyde et al., 2016; Réblová et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2018, 2020; Wang et al., 2018; Pintos et al., 2019).

Several studies revealed bambusicolous Arthrinium species from Poaceae and Cyperaceae host plants in China (Dai et al., 2016, 2017; Jiang et al., 2018, 2020; Wang et al., 2018), and several Arthrinium-like taxa on dead leaves, clumps, and twigs of bamboo were collected from Shenzhen (China) during this study. The aims of this study are identifying these Arthrinium-like taxa based on morphology and phylogeny and describe and illustrate them. Phylogenetic relationships were investigated based on DNA sequence data of the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), large subunit nuclear ribosomal DNA (LSU), beta tubulin (β-tubulin), and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef 1-α), and two new Arthrinium species from bamboo are introduced as Arthrinium pseudorasikravindrae and A. acutiapicum and two locality records, Arthrinium bambusae and Arthrinium guizhouense, are described and illustrated.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Fungal Isolation

Fresh specimens of Arthrinium-like taxa were collected from Bijiashan Mountain Park, Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China, in September–October 2018, and the collection site has a tropical climate with abundant sunshine and rainfall all year round. The yearly average temperature is 22°C and vegetative type is tropical evergreen monsoon forests (Li et al., 2015). Specimens were brought to the laboratory in paper bags and they were examined under a stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss Discovery V8), and blackish conidial mass and fruit bodies were observed. The fruit bodies were studied and photographed using a stereomicroscope fitted with a camera (ZEISS Axiocam 208). The micromorphological characters were studied and photographed using a compound microscope (Nikon Eclipse 80i) fitted with a digital camera (Canon 450D). All microscopic measurements such as the length of the conidiophores, conidiogenous cells, and conidia were made with Tarosoft image framework (v. 0.9.0.7).

Single conidial isolation was carried out following the method described by Senanayake et al. (2020a). Germinated conidia were aseptically transferred into fresh potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates, incubated at 20°C to obtain pure cultures, and later transferred to PDA slants and stored at 4°C for further study. Colony characteristics were recorded from cultures grown on PDA. Additionally, pure cultures were inoculated in 2% PDA together with sterilized bamboo leaves and incubated at 25°C for sporulation.

Fungarium materials are deposited in the Herbarium of Cryptogams, Kunming Institute of Botany, Academia Sinica (HKAS), and all the ex-type living cultures are deposited at the Culture Collection of Kunming Institute of Botany (KUMCC). Index Fungorum numbers1 were obtained for the new strains.

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

Fresh fungal mycelium grown on PDA for 2 weeks at 20°C in the dark was used for DNA extraction using fungal genomic DNA extraction kit (Biospin DNA Extraction Kit, Bioer Technology, Co. Ltd., Hangzhou, China) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Polymerase chain reactions (PCR) and sequencing were carried out for the following loci: the complete ITS region with the primer pair of ITS1/ITS4 (White et al., 1990); the LSU ribosomal DNA, amplified and sequenced as a single fragment with primers LR0R/LR5 (Vilgalys and Hester, 1990); the tef 1-α gene with primers EF1-728F/EF2 (Carbone and Kohn, 1999; Rehner, 2001); and the β-tubulin gene with primers bt2a and bt2b (Glass and Donaldson, 1995).

The PCR amplification reactions were carried out with the following protocol. The total volume of the PCR reaction was 25 μl reaction volume containing 1 μl of DNA template, 1 μl of each forward and reverse primer, 12.5 μl of 2 × PCR Master Mix, and 9.5 μl of double-distilled sterilized water (ddH2O). The reaction was conducted by running for 35 cycles following the condition of Senanayake et al. (2020b). The PCR products were observed on 1% agarose electrophoresis gel stained with ethidium bromide. Purification and sequencing of PCR products were carried out at Sunbiotech Company, Beijing, China. Sequence quality was checked and sequences were condensed with DNASTAR Lasergene v.7.1. Sequences derived in this study were deposited in GenBank and accession numbers were obtained (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Details of the isolates used in the phylogenetic analyses.

| Species | Strains | Substrate | Location |

GenBank Accession Number |

|||

| ITS | LSU | β-Tubulin | tef 1-α | ||||

| Arthrinium acutiapicum | KUMCC 20-0209 | Bambusa bambos | China | MT946342 | MT946338 | MT947365 | MT947359 |

| A. acutiapicum | KUMCC 20-0210 | Bambusa bambos | China | MT946343 | MT946339 | MT947366 | MT947360 |

| A. aquaticum | MFLU 18-1628 | Submerged wood | China | MK828608 | MK835806 | N/A | N/A |

| A. arundinis | CBS 450.92 | N/A | N/A | AB220259 | N/A | AB220306 | N/A |

| A. arundinis | CBS 114316 | Hordeum vulgare | Iran | KF144884 | KF144928 | KF144974 | KF145016 |

| A. arundinis | AP11118A | Bambusa sp. | Spain | MK014868 | MK014835 | MK017974 | MK017945 |

| A. aureum | CBS 244.83 | Phragmites australis | AB220251 | KF144935 | KF144981 | KF145023 | |

| A. balearicum | CBS 145129 | Poaceae sp. | Spain | MK014869 | MK014836 | MK017975 | MK017946 |

| A. bambusae | CGMCC 3.18335 | Bamboo | China | KY494718 | KY494794 | KY705186 | KY806204 |

| A. bambusae | KUMCC 20-0207 | Bambusa dolichoclada | China | MT946346 | MT946340 | MT947370 | MT947363 |

| A. bambusae | LC7107 | Bamboo | China | KY494719 | KY494795 | KY705187 | KY705117 |

| A. camelliae-sinensis | CGMCC 3.18333 | Camellia sinensis | China | KY494704 | KY494780 | KY705173 | KY705103 |

| A. camelliae-sinensis | LC8181 | Brassica campestris | China | KY494761 | KY494837 | KY705229 | KY705157 |

| A. caricicola | CBS 145127 | Carex ericetorum | Germany | MK014871 | MK014838 | MK017977 | MK017948 |

| A. chinense | CFCC 53036 | Fargesia qinlingensis | China | MK819291 | N/A | MK818547 | MK818545 |

| A. chinense | CFCC 53037 | Fargesia qinlingensis | China | MK819292 | N/A | MK818548 | MK818546 |

| A. curvatum | CBS 145131 | Carex sp. | Germany | MK014872 | MK014839 | MK017978 | MK017949 |

| A. descalsii | CBS 145130 | Ampelodesmos mauritanicus | Spain | MK014870 | MK014837 | MK017976 | MK017947 |

| A. dichotomanthi | CGMCC 3.18332 | Dichotomanthus tristaniaecarpa | China | KY494697 | KY494832 | KY705167 | KY705096 |

| A. dichotomanthi | LC8175 | Dichotomanthus tristaniaecarpa | China | KY494755 | KY494831 | KY705223 | KY705151 |

| A. esporlense | CBS 145136 | Phyllostachys aurea | Spain | MK014878 | MK014845 | MK017983 | MK017954 |

| A. euphorbiae | IMI 285638b | Bambusa sp. | Bangladesh | AB220241 | N/A | AB220288 | NA |

| A. gaoyouense | CFCC 52301 | Phragmites australis | China | MH197124 | N/A | MH236789 | MH236793 |

| A. gaoyouense | CFCC 52302 | Phragmites australis | China | MH197125 | N/A | MH236790 | MH236794 |

| A. garethjonesii | JHB004 | Bambusa sp. | China | KY356086 | KY356091 | N/A | N/A |

| A. garethjonesii | HKAS 96289 | Bambusa sp. | China | NR_154736 | NG_057131 | N/A | N/A |

| A. guizhouense | LC5318 | Air | China | KY494708 | KY494784 | KY705177 | KY705107 |

| A. guizhouense | KUMCC 20-0206 | Bambusa multiplex | China | MT946347 | MT946341 | MT947369 | MT947364 |

| A. guizhouense | CGMCC 3.18334 | Air | China | KY494709 | KY494785 | KY705178 | KY705108 |

| A. gutiae | CBS 135835 | Gut of a grasshopper | India | KR011352 | MH877577 | KR011350 | KR011351 |

| A. hispanicum | IMI 326877 | Maritime sand | Spain | AB220242 | AB220336 | AB220289 | NA |

| A. hydei | KUMCC 16-0204 | Bambusa tuldoides | China | KY356087 | KY356092 | N/A | NA |

| A. hydei | CBS 114990 | Bamboo | China | KF144890 | KF144936 | KF144982 | KF145024 |

| A. hyphopodii | MFLUCC 15-0003 | Bambusa tuldoides | China | KR069110 | N/A | N/A | NA |

| A. hyphopodii | KUMCC 16-0201 | Bamboo | China | KY356088 | N/A | N/A | NA |

| A. hysterinum | ICPM6889 | Bamboo | New Zealand | MK014874 | MK014841 | MK017980 | MK017951 |

| A. hysterinum | AP2410173 | Phyllostachys aurea | Spain | MK014876 | MK014843 | N/A | N/A |

| A. ibericum | CBS 145137 | Arundo donax | Portugal | MK014879 | MK014846 | MK017984 | MK017955 |

| A. italicum | CBS 145138 | Phragmites australis | Spain | MK014880 | MK014847 | MK017985 | MK017956 |

| A. italicum | AP221017 | Phragmites australis | Spain | MK014881 | MK014848 | MK017986 | MK017957 |

| A. japonicum | IFO 30500 | Carex despalata | Japan | AB220262 | AB220356 | AB220309 | N/A |

| A. japonicum | IFO 31098 | Carex despalata | Japan | AB220264 | AB220358 | AB220311 | N/A |

| A. jatrophae | MMI 00051 | Jatropha podagrica | India | JQ246355 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| A. jiangxiense | CGMCC 3.18381 | Maesa sp. | China | KY494693 | N/A | KY705163 | KY705092 |

| A. jiangxiense | LC4578 | Camellia sinensis | China | KY494694 | KY494770 | KY705164 | KY705093 |

| A. kogelbergense | CBS 113332 | Cannomois virgate | South Africa | KF144891 | KF144937 | KF144983 | KF145025 |

| A. kogelbergense | CBS 113333 | Restionaceae sp. | South Africa | KF144892 | KF144938 | KF144984 | KF145026 |

| A. locutum-pollinis | LC11683 | Brassica campestris | China | MF939595 | N/A | MF939622 | MF939616 |

| A. longistromum | MFLUCC 11-0479 | Bamboo | Thailand | KU940142 | KU863130 | N/A | NA |

| A. longistromum | MFLUCC 11-0481 | Bamboo | Thailand | KU940141 | KU863129 | N/A | NA |

| A. longistromum | MFLU 15-1184 | Bambusa sp. | Thailand | NR_154716 | N/A | N/A | NA |

| A. malaysianum | CBS 251.29 | Cinnamomum camphora | N/A | KF144897 | KF144943 | KF144989 | KF145031 |

| A. malaysianum | CBS 102053 | Macaranga hullettii | Malaysia | KF144896 | KF144942 | KF144988 | KF145030 |

| A. marii | CBS 497.90 | Air | Spain | AB220252 | KF144947 | KF144993 | KF145035 |

| A. marii | CBS 114803 | Arundinaria hindsii | China | KF144899 | KF144945 | KF144991 | KF145033 |

| A. mediterranei | IMI 326875 | Air | Spain | AB220243 | N/A | AB220290 | NA |

| A. neosubglobosa | JHB006 | Bamboo | China | KY356089 | KY356094 | N/A | NA |

| A. neosubglobosa | JHB007 | Bamboo | China | KY356090 | KY356095 | N/A | NA |

| A. obovatum | CGMCC 3.18331 | Lithocarpus sp. | China | KY494696 | KY494834 | KY705166 | KY705095 |

| A. obovatum | LC8177 | Lithocarpus sp. | China | KY494757 | KY494833 | KY705225 | KY705153 |

| A. ovatum | CBS 115042 | Arundinaria hindsii | China | KF144903 | KF144950 | KF144995 | KF145037 |

| A. paraphaeospermum | MFLUCC 13-0644 | Bamboo | Thailand | KX822128 | KX822124 | N/A | NA |

| A. phaeospermum | CBS 114314 | Hordeum vulgare | Iran | KF144904 | KF144951 | KF144996 | KF145038 |

| A. phaeospermum | CBS 114315 | Hordeum vulgare | Iran | KF144905 | KF144952 | KF144997 | KF145039 |

| A. phragmitis | CPC 18900 | Phragmites australis | Italy | KF144909 | N/A | KF145001 | KF145043 |

| A. phragmitis | AP3218 | Phragmites australis | Spain | MK014891 | MK014858 | MK017996 | MK017967 |

| A. phragmitis | AP2410172A | Phragmites australis | Spain | MK014890 | MK014857 | MK017995 | MK017966 |

| A. piptatheri | CBS 145149 | Piptatherum miliaceum | Spain | MK014893 | MK014860 | N/A | MK017969 |

| A. pseudoparenchymaticum | CGMCC 3.18336 | Bamboo | China | KY494743 | KY494830 | KY705211 | KY705139 |

| A. pseudoparenchymaticum | LC8173 | Bamboo | China | KY494753 | KY494829 | KY705221 | KY705149 |

| A. pseudorasikravindrae | KUMCC 20-0208 | Bambusa dolichoclada | China | MT946344 | N/A | MT947367 | MT947361 |

| A. pseudorasikravindrae | KUMCC 20-0211 | Bambusa dolichoclada | China | MT946345 | N/A | MT947368 | MT947362 |

| A. pseudosinense | CBS 135459 | Bamboo | Netherlands | KF144910 | KF144957 | N/A | KF145044 |

| A. pseudospegazzinii | CBS 102052 | Macaranga hullettii | Malaysia | KF144911 | KF144958 | KF145002 | KF145045 |

| A. pterospermum | CBS 123185 | Machaerina sinclairii | New Zealand | KF144912 | KF144959 | KF145003 | NA |

| A. pterospermum | CBS 134000 | Machaerina sinclairii | Australia | KF144913 | KF144960 | KF145004 | KF145046 |

| A. puccinioides | CBS 549.86 | Lepidosperma gladiatum | Germany | AB220253 | AB220347 | AB220300 | NA |

| A. qinlingense | CFCC 52303 | Fargesia qinlingensis | China | MH197120 | N/A | MH236791 | MH236795 |

| A. qinlingense | CFCC 52304 | Fargesia qinlingensis | China | MH197121 | N/A | MH236792 | MH236796 |

| A. rasikravindrae | NFCCI 2144 | Cissus sp. | Netherlands | KF144914 | N/A | N/A | NA |

| A. rasikravindrae | MFLUCC 11-0616 | Bamboo | Thailand | KU940144 | KU863132 | N/A | NA |

| A. sacchari | CBS 212.30 | Phragmites australis | UK | KF144916 | KF144962 | KF145005 | KF145047 |

| A. sacchari | CBS 301.49 | Bamboo | Indonesia | KF144917 | KF144963 | KF145006 | KF145048 |

| A. saccharicola | CBS 191.73 | Air | Netherlands | KF144920 | KF144966 | KF145009 | KF145051 |

| A. saccharicola | CBS 463.83 | Phragmites australis | Netherlands | KF144921 | KF144968 | KF145010 | KF145052 |

| A. serenense | IMI 326869 | N/A | Spain | AB220250 | N/A | AB220297 | NA |

| A. serenense | ATCC 76309 | N/A | N/A | AB220240 | N/A | AB220287 | NA |

| A. sporophleum | CBS 145154 | Juncus sp. | Spain | MK014898 | MK014865 | MK018001 | MK017973 |

| A. subglobosum | MFLUCC 11-0397 | Bamboo | Thailand | KR069112 | KR069113 | N/A | NA |

| A. subroseum | LC7291 | Bamboo | China | KY494751 | KY494827 | KY705219 | KY705147 |

| A. subroseum | CGMCC3.18337 | Bamboo | China | KY494752 | KY494828 | KY705220 | KY705148 |

| A. thailandicum | MFLUCC 15-0199 | Bamboo | Thailand | KU940146 | KU863134 | N/A | NA |

| A. thailandicum | MFLUCC 15-0202 | Bamboo | Thailand | KU940145 | KU863134 | N/A | NA |

| A. tintinnabula | ICPM 6889 | Bamboo | New Zealand | MK014874 | MK014841 | MK017980 | MK017951 |

| A. trachycarpum | CFCC 53038 | Trachycarpus fortune | China | MK301098 | N/A | MK303394 | MK303396 |

| A. trachycarpum | CFCC 53039 | Trachycarpus fortune | China | MK301099 | N/A | MK303395 | MK303397 |

| A. vietnamense | IMI 99670 | Citrus sinensis | Vietnam | KX986096 | KX986111 | KY019466 | NA |

| A. xenocordella | CBS 478.86 | Soil | Zimbabwe | KF144925 | KY494763 | N/A | NA |

| A. xenocordella | CBS 595.66 | Soil | Austria | KF144926 | KF144971 | KF145013 | KF145055 |

| A. yunnanum | MFLU 15-0002 | Phyllostachys nigra | China | KU940147 | KU863135 | N/A | NA |

| A. yunnanum | CFCC 52312 | Bamboo | China | MH191120 | N/A | N/A | NA |

| Pestalotiopsis hamaeropis | CBS 237.38 | N/A | Italy | MH855954 | MH867450 | KM199392 | KM199474 |

Newly obtained sequences are indicated in black bold. ATCC, The American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, United States; CBS, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CFCC, China Forestry Culture Collection, Beijing, China; CGMCC, China General Microbiological Culture Collection, Beijing, China; CPC, Culture collection of Pedro Crous, housed at the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute; HKAS, Herbarium of Cryptogams, Kunming, China; ICPM, International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants, Auckland, New Zealand; IFO, Institute for Fermentation, Osaka; IMI, Culture collection of CABI Europe UK Centre, UK; KUMCC, Culture Collection of Kunming Institute of Botany, Kunming, China; MFLU, Mae Fah Luang University Herbarium, Chiang Rai, Thailand; LC, Working collection of Lei Cai, housed at CAS, China; MFLUCC, Mae Fah Luang University Culture Collection, Chiang Rai, Thailand; NFCCI, National Fungal Culture Collection of India.

Sequence Alignments and Phylogenetic Analyses

BLASTn searches were made using the newly generated sequences to assist in taxon sampling for phylogenetic analyses. Jiang et al. (2018, 2020), Wang et al. (2018), and Pintos et al. (2019) were followed to obtain sequences from GenBank that are listed in Table 1. The concatenated ITS, LSU, β-tubulin, and tef 1-α sequence dataset comprised 101 strains of Arthrinium, while the outgroup taxon was Pestalotiopsis chamaeropis (CBS 237.38). DNA sequences of the ITS, LSU, β-tubulin, and tef 1-α were aligned using the online version of MAFFT v. 7.0362 (Katoh et al., 2020) with default settings and manually adjusted using BioEdit 7.1.3 (Hall, 1999) to allow maximum alignment and minimum gaps. Further, single gene alignments were combined to obtain the final multiloci alignment that was containing 2,817 nucleotide characters, viz. 681 of ITS, 875 of LSU, 434 of β-tubulin, and 827 of tef 1-α. Both single and concatenated alignments were used for the analyses.

Maximum likelihood analyses were performed by RAxML (Stamatakis and Alachiotis, 2010) implemented in raxmlGUIv.1.5 (Silvestro and Michalak, 2012) using the ML + rapid bootstrap setting and the GTR + I + G model of nucleotide substitution with 1,000 replicates. The matrix was partitioned for the different gene regions included in the combined multilocus analyses.

For the Bayesian inference (BI) analyses, the optimal substitution model for the combined dataset was determined to be GTR + I + G using the MrModeltest software v. 2.2 (Nylander, 2004). The BI analyses was computed with MrBayes v. 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al., 2012) with four simultaneous Markov chain Monte Carlo chains from random trees over 10 M generations (trees were sampled every 500th generation).

The distribution of log-likelihood scores was observed to check whether sampling is in stationary phase or not, and Tracer v1.5 was used to check if further runs were required to reach convergence or not (Rambaut and Drummond, 2007). The Bayesian analyses lasted until the average standard deviation of split frequencies has a value less than 0.01, and the consensus tree and posterior probabilities were calculated after discarding the first 20% of the sampled trees as burn-in. The phylogram was visualized in FigTree v. 1.4 (Rambaut, 2009). All the phylogenetic trees derived from this study were deposited in TreeBase3 under accession number S27147.

Results

Phylogenetic Inferences

All individual trees generated under different criteria and from single gene datasets were essentially similar in topology and not significantly different from the tree generated from the concatenated dataset (not discussed herein). Additionally, this tree topology is similar to previous studies on Arthrinium (Dai et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2018, 2020; Wang et al., 2018; Pintos et al., 2019).

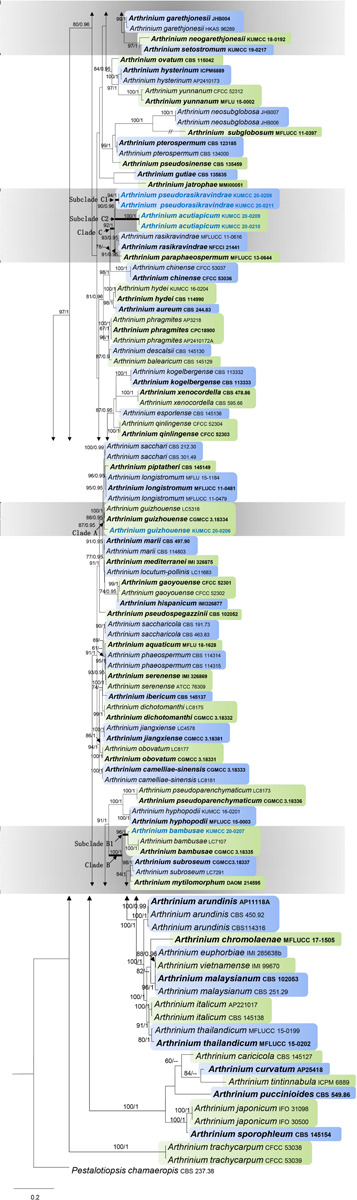

Maximum likelihood analysis of Arthrinium species in this study with 1,000 bootstrap replicates yielded the best ML tree (Figure 1) with the likelihood value of –29,933.362493 and the following model parameters: estimated base frequencies—A = 0.239654, C = 0.250345, G = 0.255054, and T = 0.254948; substitution rates—AC = 1.275584, AG = 2.530572, AT = 1.397969, CG = 1.184045, CT = 4.063803, and GT = 1.0; proportion of invariable sites—I = 0.203121; gamma distribution shape parameter—α = 0.54383. The alignment contained a total of 1,756 distinct alignment patterns and 28.72% of undetermined characters. After discarding the first 20% of generations, 36,000 trees remained from which 50% consensus trees and posterior probabilities (PP) were calculated (Figure 1). Maximum likelihood bootstrap values ≥ 60% and BI ≥ 0.95 are given at each node. Tree topologies of the ML and Bayesian analyses were similar to each other and there are no significant differences.

FIGURE 1.

Phylogram generated from maximum likelihood analysis based on combined internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), large subunit nuclear ribosomal DNA (LSU), β-tubulin, and tef 1-α sequence data. Bootstrap support values greater than 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities greater than 0.90 are given at the nodes. The tree is rooted with Pestalotiopsis chamaeropis (CBS 237.38). Ex-type strains are in bold and the newly obtained sequences are indicated in blue bold.

There are 101 Arthrinium strains in this study together with a new isolate that is introduced here. All the ex-type strains of Arthrinium species were included if available, and other authentic strains were selected when sequences from ex-type strains are unavailable. Our new isolate KUMCC 20-0206 clustered with the type strain of A. guizhouense (CGMCC 3.18334) and another representative strain (LC5318) with 87% ML and 0.95 PP support. This clade (clade A) has a close phylogenetic affinity to Arthrinium longistromum, A. piptatheri, and A. sacchari with 95% ML and 0.95 PP support. Two strains of A. bambusae (CGMCC 3.18335 and LC7107) and the new isolate KUMCC 20-0207 were grouped in a separate clade with 96% ML and 1.00 PP support. This clade (subclade B1) shares a monophyletic relationship to Arthrinium garethgonesii, A. mytilomotphum, A. neogarethjonesii, A. setostromun, and A. subroseum with strong bootstrap supports (100% ML, 1.00 PP, clade B, Figure 1). Two new isolates, KUMCC 20-0208 and KUMCC 20-0211, were monophyletic in subclade C1 (Figure 1) with 90% ML and 0.96 PP support. Subclade C2 is also monophyletic with two novel strains, viz. KUMCC 20–0209 and KUMCC 20–0210, which are sisters to subclade C1 with 90% ML and 0.96 PP support (clade C, Figure 1). With these four new strains, clade C shares a close phylogenetic affiliation to A. paraphaeospermum and A. rasikravindrae.

Taxonomy

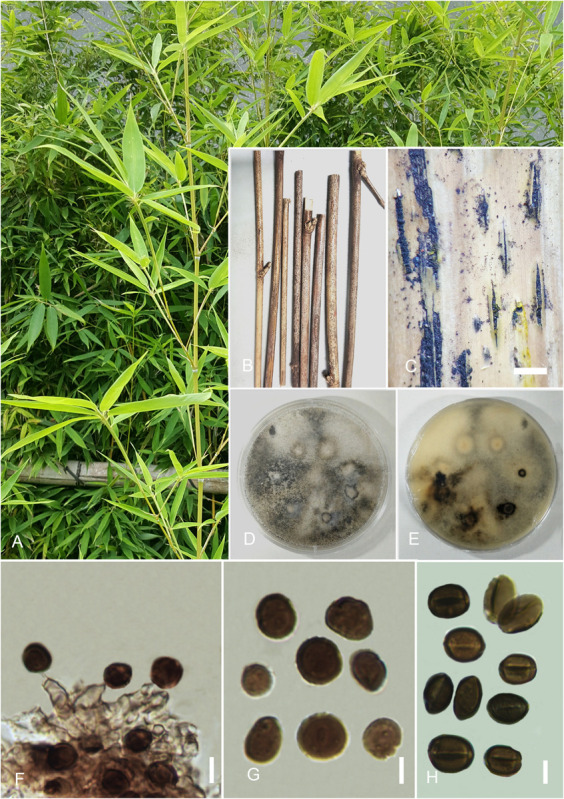

Arthrinium acutiapicum Senan. and Cheew. sp. nov. Figure 2

FIGURE 2.

Arthrinium acutiapicum (HKAS 107673). (A) Host. (B) Fungarium specimen. (C) Conidiomata on substrate. (D) Surface view of culture on potato dextrose agar (PDA). (E) Reverse view of culture on PDA. (F) Conidia and conidiogenous cells. (G,H) Conidia. Scale bars: (C) = 500 μm, (F–H) = 10 μm.

Index Fungorum number: IF557868

Etymology: Species epithet “acuti” refers to pointed and “apicum” refers to apex of conidiogenous cells.

Holotype: HKAS 107673

Saprobic on dead twigs of Bambusa bambos (L.) Voss. Hyphae 1.5–2.5 μm diam., hyaline, branched, septate, sparse. Sexual morph: undetermined. Asexual morph: Conidiomata 350–450 μm, pycnidial, immersed, aggregated, scattered, subglobose, ostiolate, black, coriaceous. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells 4–7 × 2–3 μm ( = 6.3 × 2.1 μm, n = 30), holoblastic, develop from conidiophore mother cells, erect, basauxic, cylindrical to ampulliform, apex pointed and hyaline, smooth and thick-walled, pale brown. Conidia 7.5–10 × 8.5–12 μm ( = 9.3 × 11.9 μm, n = 30), globose in surface view, subglobose to oval in side view, apex and base blunted, smooth-walled, brown to dark brown, with a dark equatorial slit.

Culture Characteristics

Colonies grew on PDA at 20°C in the dark attenuated 2 cm diam., within 7 days, flat, circular, entire margin, wooly, with abundant aerial mycelia, white in surface view and off-white to yellow in reverse. Sporulation occurred after 10 days on PDA incubated at 20°C in the dark without any host substrate. Conidia seem black mass and well spread on culture.

Specimen Examined

China, Guangdong Province, Shenzhen City, Futian District, northwest of Futian, Bijiashan Park, on dead twigs of B. bambos (L.) Voss (Poaceae), 23 September 2018, IS, SI 86 (HKAS 107673, holotype), ex-type culture, KUMCC 20-0210; ibid 15 October 2018, IS, SI 86-1 (HKAS 107674, paratype), ex-paratype culture KUMCC 20-0211.

Notes

Arthrinium acutiapicum forms a distinct subclade (subclade C2, Figure 1) with strong bootstrap support values (ML/PP = 90/0.96) in our phylogenetic analysis, which is a sister to the newly introduced species A. pseudorasikravindrae. Additionally, A. acutiapicum shows close phylogenetic affinities to A. paraphaeospermum, A. pseudorasikravindrae, and A. rasikravindrae in clade C (Figure 1) and A. chinense. Blast results of ITS, LSU, β-tubulin, and tef 1-α sequences of A. acutiapicum show high similarity to A. hydei, A. paraphaeospermum, and A. rasikravindrae. Morphologically, A. acutiapicum is distinct from A. pseudorasikravindrae by the reduction of conidiophores to conidiogenous cells, cylindrical to ampulliform, pale brown conidiogenous cells with pointed, hyaline apex and brown to dark brown, smooth-walled conidia with dark equatorial slit. Additionally, A. acutiapicum is distinct from A. rasikravindrae by the reduction of conidiophores to pale brown conidiogenous cells and dimorphous, acropleurogenously arising conidia.

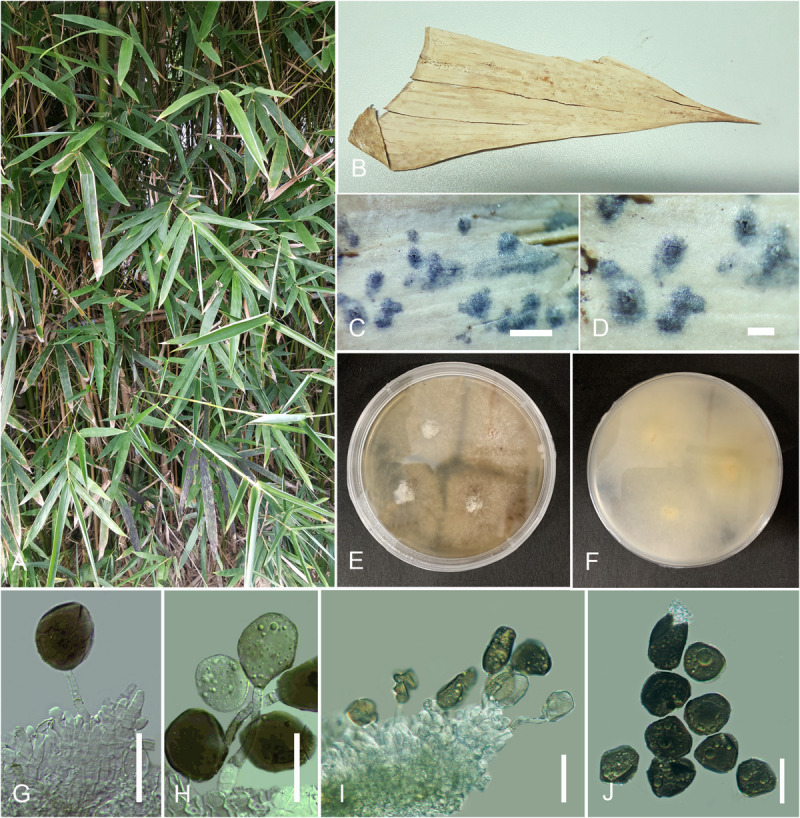

Arthrinium bambusae M. Wang and L. Cai, in Wang et al. (2018) Figure 3

FIGURE 3.

Arthrinium bambusae (HKAS 107671). (A) Host. (B) Fungarium specimen. (C,D) Conidiomata on substrate. (E,F) Culture on potato dextrose agar (PDA; surface and reverse view). (G–I) Conidia and conidiogenous cells. (J) Conidia. Scale bars: (C,D) = 100 μm, (G–J) = 15 μm.

Index Fungorum number: IF 824906

Saprobic on sheath of Bambusa dolichoclada Hayata. Hyphae 1–3 μm diam., hyaline, branched, septate, sparse. Sexual morph: undetermined. Asexual morph: appears as black, spotty patches on host surface. Conidiomata immersed, pycnidial, scattered, globose to slightly conical, ostiolate, black, coriaceous. Conidiomatal wall thin, comprising several layers of black, large cells of textura angularis. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells or rarely inconspicuous with cylindrical, thick-walled, hyaline. Conidiogenous cells 5–12 × 3–10 μm ( = 8.6 × 4 μm, n = 30), basauxic, holoblastic, develop from conidiophore mother cells, with periclinal thickening, doliiform to ampulliform or lageniform, erect, aggregated in clusters on hyphae, hyaline to pale brown, smooth. Conidia 10.5–17.5 × 8–15 μm ( = 15 × 12 μm, n = 30), subglobose to ellipsoid, guttulate, smooth to finely roughened, olivaceous to dark brown.

Culture Characteristics

Colonies grew on PDA at 20°C in the dark attenuated 2 cm diam., within 7 days, flat, spreading, margin circular, with abundant aerial mycelia, surface and reverse white to off-white.

Specimen Examined

China, Guangdong Province, Shenzhen City, Futian District, northwest of Futian, Bijiashan Park, on sheath of B. dolichoclada Hayata (Poaceae), 23 September 2018, IS, SI 80 (HKAS 107671), living culture, KUMCC 20-0207.

Notes

Arthrinium bambusae was introduced by Wang et al. (2018) from Guangdong Province, China, where our collection also was obtained. However, the exact locality is not mentioned in the original description there. The morphology of our collection was obtained from fungal structures on the host specimen, while Wang et al. (2018) had described the fungus from sporulated cultures. However, the morphology of our collection is similar to the holotype. Phylogenetically, A. bambusae clusters with A. garethjonesii, A. neogarethjonesii, A. mytilomorphum, A. setostromum, and A. subroseum with strong bootstrap value (ML/PP = 100/1), and the A. bambusae isolate (KUMCC 20-0207) clustered well with the ex-type culture (ML/PP = 96/1).

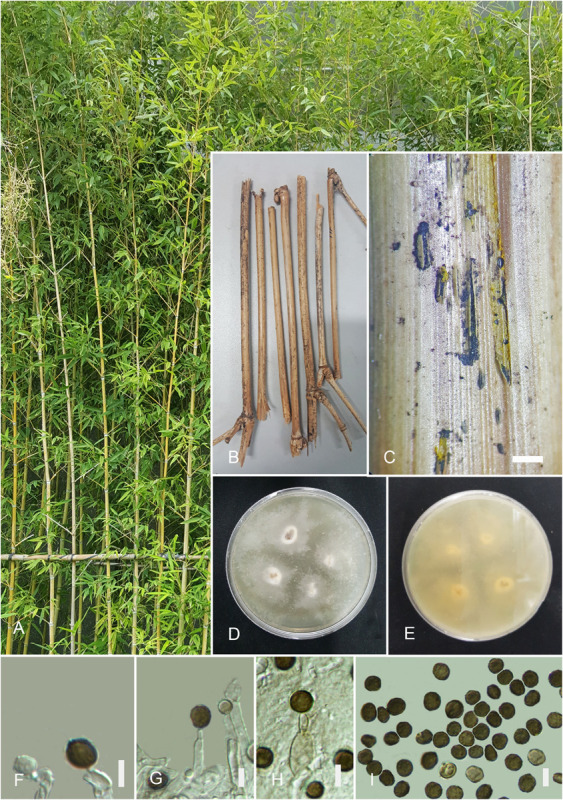

Arthrinium guizhouense M. Wang and L. Cai, in Wang et al. (2018)Figure 4

FIGURE 4.

Arthrinium guizhouense (HKAS 107672). (A) Host. (B) Fungarium specimen. (C) Conidiomata on substrate. (D) Surface view of culture on potato dextrose agar (PDA). (E) Reverse view of culture on PDA. (F–H) Conidia and conidiogenous cells. (I) Conidia. Scale bars: (C) = 1,000 μm, (F–I) = 5 μm.

Index Fungorum number: IF824909

Saprobic on dead twigs of Bambusa multiplex (Lour.) Raeusch. ex Schult. f., appear as black mass coming out from ruptured bark. Hyphae hyaline, branched, septate, 1.5–6 μm diam. Sexual morph: undetermined. Asexual morph: Conidiomata 450–350 μm, picnidial, semi-immersed, aggregated, scattered, globose, ostiolate, black, coriaceous. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells 4–8 × 3–5 μm ( = 5.3 × 4 μm, n = 30), develop from conidiophore mother cells, erect, subglobose, basauxic, ampulliform or doliiform, hyaline to pale brown, smooth. Conidia 5–7 × 4–7 μm ( = 6.3 × 5.7 μm, n = 30), globose or subglobose, smooth to finely roughened, dark brown to black, with a longitudinal, hyaline, thin, germ slit.

Culture Characteristics

Colonies grew on PDA at 20°C in the dark attenuated 2 cm diam., within 5 days, flat, wooly, margin circular, with slight aerial mycelia, surface initially white, becoming grayish white and reverse yellowish white.

Specimen Examined

China, Guangdong Province, Shenzhen City, Futian District, northwest of Futian, Bijiashan Park, on twigs of B. multiplex (Lour.) Raeusch. ex Schult. f. (Poaceae), 23 September 2018, I.C. Senanayake, SI 84 (HKAS 107672), living culture, KUMCC 20-0206.

Notes

NCBI blast result for β-tubulin sequences of this isolate gives high sequence similarities to A. guizhouense (99.55%), A. sacchari (98.25%), A. arundinis (98.25%), and A. marii (95.62%) while A. guizhouense (93.41%) and A. marii (92.94%) for tef 1-α. Additionally, high blast similarities for ITS loci are A. marii (99.54%), A. sacchari (99.22%), A. phaeospermum (99.20%), A. pseudospegazzinii (98.13%), A. longistromum (98.72%), and A. guizhouense (99.83%) while A. marii (100%), A. sacchari (100%), A. guizhouense (100%), and Apiospora montagnei (100%) for LSU. In the phylogenetic analysis, this isolate (KUMCC 20-0206) clusters with the ex-holotype strain of A. guizhouense (CGMCC3.18334) with moderate support value (ML/PP = 87/0.95). Morphologically, this collection is closely similar to the holotype specimen of A. guizhouense having brown to black, smooth to finely roughened, globose or subglobose, conidia with pale brown, subglobose, ampulliform or doliiform conidiogenous cells. However, the holotype of A. guizhouense has been collected from the air in karst cave in Guizhou Province, China, and this collection was obtained from bamboo twigs in Guangdong Province. Hence, HKAS 107672 is identified as A. guizhouense based on morphology and phylogeny. This is the first record of A. guizhouense in Guangdong Province and on bamboo.

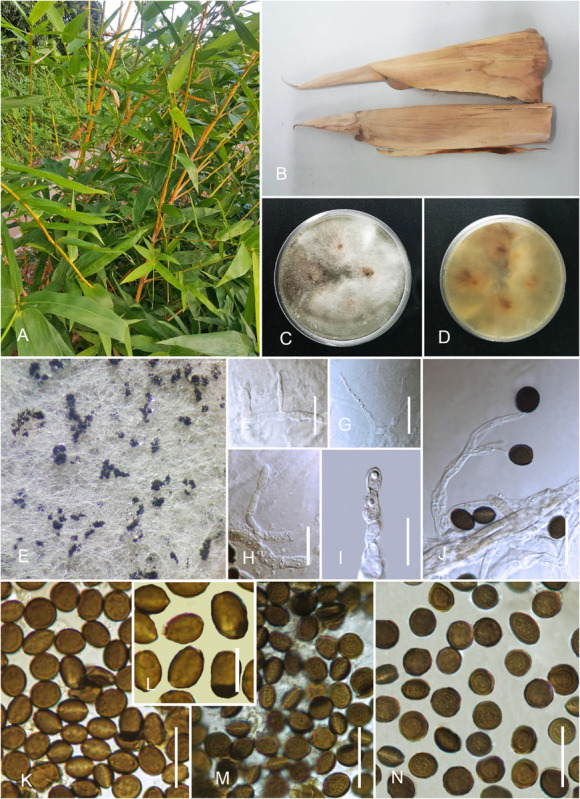

Arthrinium pseudorasikravindrae Senan., and Cheew. sp. nov. Figure 5

FIGURE 5.

Arthrinium pseudorasikravindrae (HKAS 107669). (A) Host. (B) Fungarium specimen. (C) Surface view of culture on potato dextrose agar (PDA). (D) Reverse view of culture on PDA. (E) Conidial mass on cultures. (F–J) Conidia, conidiogenous cells, and conidiophores. (K–N) Conidia (concentric pale rings are arrowed in I). Scale bars: (F–N) = 10 μm.

Index Fungorum number: IF 557870

Etymology: Species epithet the morphological similarity of this collection to Arthrinium rasikravindrae.

Holotype: HKAS 107669

Saprobic on sheaths of B. dolichoclada Hayata. Mycelium 1.5–3 μm in diam., consisting of smooth, hyaline, septate, branched, hyphae. Sexual morph: undetermined. Asexual morph: Conidiophores 10–15 × 3–7 μm ( = 12.3 × 5.2 μm, n = 30), basauxic, straight or flexuous, cylindrical, hyaline, thick, smooth-walled, aseptate. Conidiogenous cells 4–10 × 1.2–5 μm ( = 8.6 × 4.2 μm, n = 30), holoblastic, develop from conidiophore mother cells, ampulliform, cylindrical or doliiform, hyaline to olivaceous. Conidia 5–10 × 5.5–11 μm ( = 9.3 × 10.1 μm, n = 30), globose in face view, lenticular in side view, with a pale longitudinal slit, dark brown, thick-walled, finely roughened with one or two concentric pale rings.

Culture Characteristics

Colonies grew on PDA at 20°C in the dark attenuated 2 cm diam., within 5 days, flat, spreading, circular, margin filiform with abundant aerial mycelia, surface white to off-white and reverse pale yellow, sporulation occurs on 2% PDA incubated at 25°C after 2 weeks, black, conidial mass concentrated at colony margins. Sporulation occurred after 10 days on PDA incubated at 20°C in the dark without any host substrate. Conidia seem black mass and spread mostly in colony margins.

Specimen Examined

China, Guangdong Province, Shenzhen City, Futian District, northwest of Futian, Bijiashan Park, on sheath of B. dolichoclada Hayata (Poaceae), 23 September 2018, IS, SI 73 (HKAS 107669, holotype), ex-type culture, KUMCC 20-0208; ibid October 15, 2018, IS, SI 73-1 (HKAS 107670, paratype), ex-paratype culture KUMCC 20-0211.

Notes

Blast results of ITS, LSU, β-tubulin, and tef 1-α sequences of A. pseudorasikravindrae (KUMCC 20-0208, KUMCC 20-0211) show high similarity to A. hydei, A. paraphaeospermum, and A. rasikravindrae. In our phylogenetic analysis, A. pseudorasikravindrae forms a subclade (subclade C1, Figure 1) with strong bootstrap support values (ML/PP = 90/0.96), which is a sister to the newly introduced species A. acutiapicum. Additionally, A. pseudorasikravindrae shows close phylogenetic affinities to A. chinense, A. paraphaeospermum, and A. rasikravindrae (Figure 1).

Arthrinium pseudorasikravindrae is morphologically distinct from the above species (Table 2) by its thick-walled, finely roughened conidia with pale, equatorial slit and ampulliform, cylindrical or doliiform, basauxic conidiogenous cells. The morphology of A. pseudorasikravindrae is compared with other closely related species (Table 2). Therefore, considering morphological and molecular uniqueness, these isolates are introduced here as belonging to a new species, A. pseudorasikravindrae. HKAS 107669 and HKAS 107670 represent a distinct clade (clade A, Figure 1) which not known before in the phylogenetic analysis, and hence, these collections are introduced here as a new species based on their morphology and phylogeny.

TABLE 2.

Morphological comparisons of species which are phylogenetically closely related to Arthrinium acutiapicum and Arthrinium pseudorasikravindrae.

| Characters | A. acutiapicum | A. chinense | A. paraphaeospermum | A. pseudorasikravindrae | A. rasikravindrae |

| Host/substrate | Bambusa bambos/dead twigs | Fargesia qinlingensis/culms | Bambusa sp./culms | Bambusa dolichoclada/sheath | Soil, Coffea arabica/leaf, Pinus thunbergii/wood, marine submerged wood, Oryza granulate/leaf |

| Localities | China | China | Thailand | China | Norway, China, Japan |

| Life mode | Saprobic | Saprobic | Saprobic | Saprobic | Saprobic, endophytic |

| Conidiophore | Reduced to conidiogenous cells | Reduced to conidiogenous cells | Reduced to conidiogenous cells | 10–15 × 3–7 μm, cylindrical, branched, aseptate thick-walled hyaline | 5-90 × 1-1.5 μm, arising from swollen basal cells, unbranched, septate, thin-walled hyaline to subhyaline |

| Conidiogenous cell | 4–7 × 2–3 μm, cylindrical to ampulliform with pointed apex, pale brown, apex hyaline | 1.5–6.5 × 1–3.5 μm, aggregated in clusters on hyphae, doliiform to clavate or lageniform, hyaline to pale brown | 25–30 × 4–6 μm, aggregated in clusters on hyphae, elongated, conical to ampulliform, hyaline | 4–10 × 1.2–5 μm, phialidic with periclinal thickening, ampulliform, cylindrical or doliiform, hyaline to olivaceous | 5–10 × 2–4 μm, phialidic with periclinal thickening, ampulliform, hyaline |

| Conidia | Monomorphous, 7.5–10 × 8.5–12 μm, globose in surface view, subglobose to oval in side view, brown to dark brown, smooth, apex and base blunted, dark equatorial slit | Monomorphous, 8.5–11 × 6.5–8 μm, subglobose to lenticular, brown to dark brown, smooth to finely roughened, a longitudinal germ slit | Dimorphous, globose 10–19 × 11–20 μm, ellipsoid to clavate 20–30 × 9–13 μm, brown, smooth to somewhat granular, with pale equatorial slit | Monomorphous, 5–10 × 5.5–11 μm, globose in surface view, lenticular in side view, dark brown, thick-walled, with a pale equatorial slit, finely roughened, one or two concentric pale rings | Dimorphous, lenticular 10-15 × 6-10.5 μm, elongate to clavate 15-25 × 7.5-10 μm, arising acropleurogenously, brown to olivaceous, smooth, two-walled, prominent truncate base and equatorial germ slit |

| References | This study | Jiang et al. (2020) | Hyde et al. (2016) | This study | Singh et al. (2012) |

Discussion

Bamboo is an important group of flowering plants that helps to conserve and manage forest ecosystems and reduce soil erosion and it is also important for panda conservation and many more commercial applications such as making fishing rod, flute, paper, flooring material, etc. and as food for humans and livestock (Chapman and Peat, 1992). Members of bamboo belong to the family Poaceae comprising more than 115 genera with approximately 1,450 species (Gratani et al., 2008; Kelchner and Group, 2013), and bamboo occurs in all tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions as herbaceous or woody plants. Microfungi associate with bamboo in many ways and phytopathogenic or endophytic microfungi form diseases while saprobic microfungi help to decompose plant debris (Zhang and Wang, 1999; Hyde et al., 2002a,b).

The first monograph on bambusicolous fungi was published with 258 fungal species by Hino and Katumoto (1960), and 63 new species were introduced by Petrini et al. (1989). Eriksson and Yue (1998) provided a checklist of the ascomycetes on bamboo, while Zhang and Wang (1999) recorded 213 species described from bamboo in China. Kuai (1996) listed phytopathogenic bambusicolous fungi in China and Taiwan. Hyde et al. (2002a) reviewed bambusicolous fungi that grow on all bamboo substrates including the leaves, culms, branches, rhizomes, and roots and enlisted more than 1,100 species, which belong to 228 genera. Dai et al. (2018) have reviewed the taxonomy of bambusicolous fungi. This study is one of the articles in the series on bambusicolous microfungi in Guangdong Province. Herein, we collected Arthrinium-like taxa from bamboo plant samples from Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China. Currently, there are 81 species in the Arthrinium (Species Fungorum, 2020) and only 61 have molecular data. More than 30% of holotypes of Arthrinium species have been collected in China (Table 1). Therefore, the aims of this paper were to study Arthrinium-like fungi in Guangdong Province and to introduce several putative new species by comparing them morphologically and genetically with existing taxa.

According to morphology and phylogeny, two novel Arthrinium species were obtained with two new locality records. Most phylogenetic studies on Arthrinium used ITS, β-tubulin, and tef 1-α; however, LSU has been added to the analyses here. Negligible variations occur in tree topology in spite of adding LSU. A. guizhouense (HKAS 107672) is the first record in Guangdong Province and also from bamboo. The holotype of A. guizhouense was collected from the air in kart caves in Guizhou Province, China (Wang et al., 2018). This suggests that fungal conidioma in plant hosts release the conidia and conidia can survive in the air for a sufficiently long time. Our strain of A. bambusae is identical to the holotype which was collected from Guangdong Province on bamboo (Wang et al., 2018). Hence, this specimen can be used as an epitype if the holotype cannot be used for taxonomic purpose. The morphological differences between these two Arthrinium species are listed in Table 2. However, the life mode, host, and colony characters of these two species are not significantly different.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

IS designed the study, performed the morphological study and phylogenetic analyses, and wrote the manuscript. JB, NX, and RC reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the kind support given by the laboratory staff of the College of Life Science and Oceanography, ShenzhenUniversity, Shenzhen, China, for the support in doing molecularwork. IS thanks Chiang Mai University and NX thanks the National Natural Science Foundation of China for funding this research. Our special thanks go to staff members of the Herbarium of Cryptogams, Kunming Institute of Botany, Academia Sinica (HKAS) and the Culture Collection of Kunming Institute of Botany (KUMCC) for depositing all the authentic cultures and fungarium specimens. IS thanks Dr. Shaun Pennycook for proposing Latin names of the new species.

Funding. This study was funded by Chiang Mai University postdoctoral research fund, Science and technology Project of Shenzhen City, Shenzhen Bureau of Science, Technology and Information (JCYJ20180305123659726), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31601014).

References

- Agut M., Calvo M. A. (2004). In vitro conidial germination in Arthrinium aureum and Arthrinium phaeospermum. Mycopathologia 157 363–367. 10.1023/B:MYCO.0000030432.08860.f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I., Kohn L. M. (1999). A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 91 553–556. 10.1080/00275514.1999.12061051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman G. P., Peat W. E. (1992). An Introduction to Grasses (including Bamboos and Cereals). London: Redwood Press Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Wu X. Q., Huang M. X., Han Y. Y. (2014). First report of brown culm streak of Phyllostachys praecox caused by Arthrinium arundinis in Nanjing, China. Plant Dis. 98 1274. 10.1094/PDIS-02-14-0165-PDN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole G. T. (1986). Models of cell differentiation in conidial fungi. Microbiol. Rev. 50 95–132. 10.1128/MMBR.50.2.95-132.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous P. W., Groenewald J. Z. (2013). A phylogenetic re-evaluation of Arthrinium. IMA Fungus 4 133–154. 10.5598/imafungus.2013.04.01.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous P. W., Wingfield M. J., Le Roux J. J., Richardson D. M., Strasberg D., Shivas R. G., et al. (2015). Fungal planet description sheets: 371-399. Persoonia 35 264–327. 10.3767/003158515X690269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai D. Q., Jiang H. B., Tang L. Z., Bhat D. J. (2016). Two new species of Arthrinium (Apiosporaceae, Xylariales) associated with bamboo from Yunnan, China. Mycosphere 7 1332–1345. 10.5943/mycosphere/7/9/7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai D. Q., Phookamsak R., Wijayawardene N. N., Li W. J., Bhat D. J., Xu J. C., et al. (2017). Bambusicolous fungi. Fungal Divers. 82 1–105. 10.1007/s13225-016-0367-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai D. Q., Tang L. Z., Wang H. B. (2018). “A review of bambusicolous ascomycetes,” in Bamboo: Current and Future Prospects, ed. Abdul Khalil H. P. S. (IntechOpen: ), 210. [Google Scholar]

- De Hoog G. S., Guarro J., Gene J., Figueras M. J. (2000). Atlas of Clinical Fungi, 2nd Edn, Utrecht: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson O., Yue J. Z. (1998). Bambusicolous pyrenomycetes, an annotated check-list. Myconet 1 25–78. [Google Scholar]

- Glass N. L., Donaldson G. C. (1995). Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61 1323–1330. 10.1128/AEM.61.4.1323-1330.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratani L., Crescente M. F., Varone L., Fabrini G., Digiulio E. (2008). Growth pattern and photosynthetic activity of different bamboo species growing in the Botanical Garden of Rome. Flora Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 203 77–84. 10.1016/j.flora.2007.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hino I., Katumoto K. (1960). Icones Fungorum Bambusicolorum Japonicorum. Kobe: The Fuji Bamboo Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Hong J. H., Jang S., Heo Y. M., Min M. (2015). Investigation of marine-derived fungal diversity and their exploitable biological activities. Mar. Drugs 13 4137–4155. 10.3390/md13074137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde K. D., Hongsanan S., Jeewon R., Bhat D. J., McKenzie E. H. C., Jones E. B. G., et al. (2016). Fungal diversity notes 367-490: taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 80 1–270. 10.1007/s13225-016-0373-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde K. D., Zhou D., Dalisayl T. (2002a). Bambusicolous fungi: a review. Fungal Divers. 9 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde K. D., Zhou D., McKenzie E., Ho W., Dalisay T. (2002b). Vertical distribution of saprobic fungi on bamboo culms. Fungal Divers. 11 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N., Li J., Tian C. M. (2018). Arthrinium species associated with bamboo and reed plants in China. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2 1–9. 10.3114/fuse.2018.02.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N., Liang Y. M., Tian C. M. (2020). A novel bambusicolous fungus from China, Arthrinium chinense (Xylariales). Sydowia 72 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Rozewicki J., Yamada K. D. (2020). MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 20 1160–1166. 10.1093/bib/bbx108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelchner S. A., Group B. P. (2013). Higher level phylogenetic relationships within the bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) based on five plastid markers. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 67 404–413. 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuai S. Y. (1996). A checklist of pathogenic Bambusicolous fungi of mainland China and Taiwan. J. For. Sci. Technol. 4 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Li B. J., Liu P. Q., Jiang Y., Weng Q. Y., Chen Q. H. (2016). First report of culm rot caused by Arthrinium phaeospermum on Phyllostachys viridis in China. Plant Dis. 100 1013–1013. 10.1094/PDIS-08-15-0901-PDN [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Chan P. W., Wang D., Tan M. (2015). Rapid urbanization effect on local climate: intercomparison of climate trends in Shenzhen and Hong Kong, 1968-2013. Clim. Res. 63 145–155. 10.3354/cr01293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.-L., Hyde K. D., Liu J.-K., Maharachchikumbura S. S. N., Jeewon R., Bao D.-F., et al. (2019). Freshwater sordariomycetes. Fungal Divers. 99 451–660. 10.1007/s13225-019-00438-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cano C., Grey W. E., Sands D. C. (1992). First report of Arthrinium arundinis causing kernel blight on barley. Plant Dis. 76:1077 10.1094/PD-76-1077B [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mavragani D. C., Abdellatif L., McConkey B., Hamel C., Vujanovic V. (2007). First report of damping-off of durum wheat caused by Arthrinium sacchari in the semi-arid Saskatchewan fields. Plant Dis. 91:469. 10.1094/PDIS-91-4-0469A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minter D. W. (1985). A re-appraisal of the relationships between Arthrinium and other hyphomycetes. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. 94 281–308. [Google Scholar]

- Nylander J. A. A. (2004). MrModeltest 2.0. Program Distributed by the Author. Sweden: Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Petrini L. E., Müller E. (1986). Haupt-und nebenfruchtformen europäischer Hypoxylon-Arten (Xylariaceae, Sphaeriales) und verwandter Pilze. Mycol. Helv. 1 501–627. [Google Scholar]

- Petrini O., Candoussau F., Petrini L. (1989). Bambusicolous fungi collected in southwestern France 1982–1989. Mycologia Helvetica 3, 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Pintos A., Alvarado P., Planas J., Jarling R. (2019). Six new species of Arthrinium from Europe and notes about A. caricicola and other species found in Carex spp. Hosts. Mycokeys 49 15–48. 10.3897/mycokeys.49.32115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai M. K. (1989). Mycosis in man due to Arthrinium phaeospermum var. indicum. First case report of mycosis due to Arthrinium phaeospermum var. indicum in humans. Mycoses 32 472–475. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1989.tb02285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. (2009). FigTree v1.4: Tree Figure Drawing Tool. Available online at: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtre?e/ (accessed July 25, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A., Drummond A. J. (2007). Tracer v1, 4. Available online at: http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer (accessed July 1, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Ramos H. P., Braun G. H., Pupo M. T., Said S. (2010). Antimicrobial activity from endophytic fungi Arthrinium state of Apiospora montagnei Sacc. and Papulaspora immersa. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 53 629–632. 10.1590/S1516-89132010000300017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Réblová M., Miller A. N., Rossman A. Y., Seifert K., Crous P., Hawksworth D., et al. (2016). Recommendations for competing sexual-asexually typified generic names in Sordariomycetes (except Diaporthales, Hypocreales, and Magnaporthales). IMA Fungus 7 131–153. 10.5598/imafungus.2016.07.01.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehner S. (2001). Primers for Elongation Factor 1-α (EF1-α). Washington, DC: Insect Biocontrol Laboratory: USDA, ARS, PSI. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Teslenko M., van der Mark P., Ayres D. L., Darling A., Höhna S., et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 61 539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J. C., Kunze G. (1817). Mykologische Hefte. 1. Leipzig: Vossische Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake I. C., Jeewon R., Hyde K. D., Bhat J. D., Cheewangkoon R. (2020a). Taxonomy and phylogeny of Leptosillia cordylinea sp. nov. from China. Phytotaxa 435 213–226. 10.11646/phytotaxa.435.3.1 24943631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake I. C., Rathnayake A. R., Marasinghe D. S., Calabon M. S., Gentekaki E., Lee H. B., et al. (2020b). Morphological approaches in studying fungi: collection, examination, isolation, sporulation and preservation. Mycosphere (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake I. C., Maharachchikumbura S. S., Hyde K. D., Bhat J. D., Jones E. G., Wendt L., et al. (2015). Towards unraveling relationships in Xylariomycetidae (Sordariomycetes). Fungal Divers. 73 73–144. 10.1007/s13225-015-0340-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Kulkarni G., Sonawane M. S., Shouche Y. S. (2014). A new endophytic species of Arthrinium (Apiosporaceae) from Jatropha podagrica. Mycoscience 55 118–123. 10.1016/j.myc.2013.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha P., Ibáñez A. B., Bauer S., Glassman S. I., Szaro T. M., Bruns T. D., et al. (2015). Fungi isolated from Miscanthus and sugarcane: biomass conversion, fungal enzymes, and hydrolysis of plant cell wall polymers. Biotechnol. Biofuels 8:1. 10.1186/s13068-015-0221-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestro D., Michalak I. (2012). raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org. Divers. Evol. 12 335–337. 10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. M., Yadav L. S., Singh P. N., Hepat R., Sharma R., Singh S. K. (2012). Arthrinium rasikravindrii sp. nov. from Svalbard, Norway. Mycotaxon 122 449–460. 10.5248/122.449 30528588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Species Fungorum (2020). Available online at: http://www.speciesfungorum.org/Names/Names.asp (accessed July 10, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A., Alachiotis N. (2010). Time and memory efficient likelihood-based tree searches on phylogenomic alignments with missing data. J. Bioinform. 26 132–139. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R., Hester M. (1990). Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 172 4238–4246. 10.1128/JB.172.8.4238-4246.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Tan X. M., Liu F., Cai L. (2018). Eight new Arthrinium species from China. Mycokeys 34 1–24. 10.3897/mycokeys.34.24221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T. J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. Guide Methods Appl. 18 315–322. 10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wijayawardene N. N., Hyde K. D., Al-Ani L. K. T., Tedersoo L., Haelewaters D., Fiuza P. O., et al. (2020). Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa. Mycosphere 11 1060–1456. 10.5943/mycosphere/11/1/8 10549654 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. Q., Wang X. G. (1999). Fungus resource of bamboos in China. J. Bamboo Res. 18 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. M., Deng C. R., Chen X. (1990). Arthrinium phaeospermum causing dermatomycosis, a new record of China. Acta Mycol. 9 232–235. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.