Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are pivotal regulators of immune responses, specialized in antigen presentation and bridging the gap between the innate and adaptive immune system. Due to these key features, DCs have become a pillar of the continuously growing field of cellular therapies. Here we review recent advances in good manufacturing practice strategies and their individual specificities in relation to DC production for clinical applications. These take into account both small-scale experimental approaches as well as automated systems for patient care.

Keywords: Good manufacturing practice, Monocytes, Dendritic cells

Introduction

Cell therapies are defined as preventions or treatments of human malignancies through the administration (injection, engraftment, or implantation) of cells which have been treated or altered ex vivo [1]. These include for instance stem cell transplantations and cellular vaccines, with the latter having seen enormous strides in recent years, promising patient-tailored treatments for various malignancies. These vaccines are primarily designed to target cancer cells through the induction of cellular and antibody-mediated responses. The recent decade saw the introduction of therapies employing components of the adaptive immune system as tools against cancer and brought forward for instance chimeric antigen receptor T [2] and tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte [3] therapies which not only led to a paradigm shift from direct cancer treatment to immune system modulation, but also sparked the interest of popular media and revigorated personalized medicine approaches. However, the first US Food and Drug Administration-approved cell-based cancer therapy vaccine was the dendritic cell (DC) vaccine Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) in 2010 for the treatment of prostate cancer. Autologous DCs were loaded with a prostatic acid phosphatase-granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) fusion protein to induce antigen-specific T cell-mediated tumor regression [4]. Due to their potency in antigen presentation and their role in innate and adaptive immune response mediation, DCs have become a major focus of cellular therapy applications ever since.

DCs represent professional antigen-presenting cells able to regulate innate and adaptive immunity through activation and tolerance. In their immature state, DCs patrol the microenvironment whilst continuously taking up exogenous antigens and exhibit peripheral tolerance to self-antigens [5]. Upon antigen encounter, DCs become activated through the engagement of intracellular or membrane-bound pattern recognition receptors such as retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors and toll-like receptors (TLRs), respectively [6]. During activation, DCs migrate to draining lymph nodes and undergo transcriptional changes, leading to the downregulation of endocytic activity and simultaneous heightened expression of costimulatory molecules such as CD86 and CD40 [7]. In addition, mature DCs secrete inflammatory cytokines (IL-12p70, IL-6) and are able to present antigens to fully activate T lymphocytes, allowing an antigen-specific immune response [8].

These key features highlight the importance of DCs in immunity and their potential for clinical applications. Various methods and protocols have been established since their discovery, yet the production of standard DCs under good manufacturing practice (GMP) conditions for clinical use is time-, cost-, and labor-intensive and represents a bottleneck in personalized vaccine development. Recent years brought about new appliances and methods to optimize and automate DC generation, enriching therapeutic possibilities. This review provides an overlook over the current possibilities and strategies in DC generation and discusses perspectives of DC generation for cancer and autoimmune applications.

Human DC Subsets and Monocytes

DCs and monocytes constitute a heterogeneous family of antigen-presenting cells able to mediate lymphocyte reactivity. Each subpopulation possesses distinct phenotypic and functional properties, forming a complex cellular network which can dynamically shift between tolerance and inflammation, depending on the environmental cues [7].

DCs possess a finite life span and are continuously replenished via hematopoiesis within the bone marrow [9]. Arising from the hematopoietic stem cells, progenitor populations form in the sequence of granulocyte-macrophage progenitor, macrophage DC progenitor, common DC progenitor, and the final pre-DC stages, leading towards conventional DC1 and conventional DC2 subsets [7, 9, 10]. Upon release into the periphery, DC subsets fully differentiate following exposure to tissue-specific factors, giving rise to tissue- and functionally-specialized DC subsets [11, 12]. In vitro, DCs can be differentiated from multiple sources, including bone marrow or cord blood-derived CD34+ progenitor cells or, most commonly, from peripheral blood-derived monocytes [9, 13, 14, 15]. Additionally, primary DCs can be directly isolated from blood using apheresis products. However, this is limited by the poor availability of circulating DCs in blood, which represent <1.0% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

Human monocytes constitute three major populations: classical CD14+ CD16– monocytes (approximately 85%), nonclassical CD14+/– CD16+ monocytes (5–10%), and intermediate CD14+ CD16+ monocytes (5–10%) [16]. As with conventional DCs, monocytes stem from bone marrow common DC progenitors and are continuously released into the bloodstream. Upon pathogen or “danger” signal encounter, monocytes differentiate into monocyte-derived macrophages or monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) in order to replenish and aid local antigen-presenting cells [16, 17]. These typically describe MoDCs with immunostimulatory capabilities through the exposure to proinflammatory cytokines, including GM-CSF [18], IL-4, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). Through the release of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-12p70, IL-6, IL-8) [19, 20], antigen presentation, and high expression of costimulatory molecules such as CD83, MoDCs are thereafter able to initiate antigen-specific T cell activation necessary for pathogen clearance and cancer cell killing [7].

Apart from their pivotal role in T cell stimulation, MoDCs can also gain immunoregulatory tolerogenic (tolMoDC) functions with great therapeutic potential for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Instead of proinflammatory factors, tolMoDCs typically develop in the presence of IL-10 and are themselves able to release high concentrations of IL-10, promoting the development of regulatory T cells. These qualities are of particular interest in the context of autoimmune diseases, where for instance autoreactive T cells lead to severe inflammation and tissue damage [21]. Laboratories and GMP facilities aiming to produce tolMoDCs therefore expose monocytes to IL-10, transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) [22, 23], or immunosuppressive drugs such as dexamethasone [24], rapamycin [25], curcumin [26], or 9-cis-retinoic acid [27] to induce anti-inflammatory properties [21, 28]. Similar to classical MoDCs, tolMoDCs are still capable of antigen presentation and of blocking the clonal expansion of other T cell populations whilst also inducing anergy [29]. Several studies covering multiple sclerosis [30], rheumatoid arthritis [28], and organ transplantation [31] have shown promising data in the strive for GMP-confirmative generation of tolMoDC. For a detailed overview of current clinical trials covering tolMoDC generation please see Schinnerling et al. [21].

Monocyte Collection Procedures

Human monocytes can be enriched from healthy donors or patients from several blood sources, including leukocyte apheresis preparations and waste products of regular blood donations. Depending on the starting material, e.g., leukapheresis chambers (LRSC), Ficoll density purification is especially important to reduce high amounts of granulocytes and red blood cells, which would otherwise hinder adequate monocyte differentiation [32, 33].

Monocytes can thereafter be enriched from ficolled blood via plastic adherence, which is typically employed by research laboratories due to its low cost [34, 35, 36]. Freshly isolated monocytes strongly adhere to plastic surfaces due to beta integrins (CD18, CD11c) [37] within hours. Successive washing steps thereafter reduce the amount of nonadherent leukocytes. While this method is easily applicable and ideal for small-scale applications, it is difficult to transfer to large-scale or even GMP applications. The risk of contamination due to consecutive manual washing steps to remove unwanted cells and relatively low purity (approximately 70% [34]) make it unfit for GMP procedures [32, 38, 39].

Another commonly used system uses counterflow centrifugal elutriation (CCE), whereby monocytes are enriched from leukapheresis products of LRSC-derived PBMCs via centrifugation force [40, 41, 42, 43]. Due to the particular design of the elutriation chamber and applied centrifugation force, monocytes can be enriched based on their size, allowing recovery rates of >80% [40]. This procedure does not require any additional additives which might affect functionality and offers viable and physiologically uncompromised monocytes [40]. In addition, CCE allows a rapid separation speed of up to 20 × 109 PBMCs/h [44, 45]. However, CCE applications require expensive processing equipment, trained operators, and large volumes of starting material to vindicate the financial investment.

In order to reduce contamination risks, new closed systems were introduced, offering the benefits of the CCE in addition to a single-use disposable system. Here, monocytes are directly isolated via CCE from a leukapheresis product, offering high recovery rates and an average purity up to 82.95 ± 6.01% [33]. Due to these features, this method can be easily used for monocyte processing in a GMP setting. As with the previous open CCE, this method requires costly instruments for full leukapheresis product processing and is not affordable for smaller research laboratories.

Another option of a closed system relies on the use of magnetic enrichment of target cells, implementing positive selection or depletion of unwanted cells from leukocyte apheresis products. Here, positive selection of monocytes using α-CD14 monoclonal antibodies was shown to produce up to 96–97% purity and recovery rates of approximately 89% [36, 46, 47]. Due to the lack of a cytoplasmic domain required for TLR4 activation, CD14-targeting antibodies should not be able to activate monocytes, yet a small residual risk remains that positive selection might affect the finished products' functionality [32, 48, 49].

Generation of MoDCs

Regardless of the employed system, monocytes are further differentiated and matured into MoDCs, depending on the available equipment and desired final product. Though “gold standards” exist, final medical applications may differ greatly and require treatment-specific tailoring of protocols. The primary aim of all cell therapeutic MoDC formulations is to overcome the malfunction or blockage of endogenous DCs to enhance or elicit T cell responses directed against a tumor or infection.

In order to do so, MoDCs need to efficiently present antigens (signal 1), perform costimulation (signal 2), and secrete immunostimulatory cytokines (signal 3) [50], shifting CD4+ T cell polarization towards a type 1 (TH1) or type 2 (TH2) phenotype as well as regulatory T cells depending on the cytokine environment. As discussed later on, numerous strategies can be employed to generate mature MoDCs, all with their own specific capabilities. The decision as to which one should be used is primarily dictated by the desired application, meaning which type of disease or which type of tumor is targeted. It is generally assumed that MoDCs primarily depicting type 1 stimulatory capabilities are advantageous in optimal cancer treatment, which requires the presentation of antigens via MHC-II and secretion of IL-12p70. Type 1 polarized CD4+ T cells mediate cellular immunity by targeting intracellular infections as well as by secretion of high concentrations of interferon gamma (IFNγ) and TNFα and are especially important in the induction and maintenance of CTL responses [51]. In addition, TH1 cells display direct cancer cell killing capabilities through the secretion of FasL and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand [52]. Type 2 polarized CD4+ T cells are more focused on the induction of humoral responses and secrete IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, and IL-5 [53]. The following section will address some of these variables and generation strategies for the production of MoDC vaccines.

Culture Methods

Researchers in an experimental laboratory tend to use the materials that are readily available and cost-effective. Most experimental studies concerning MoDC generation are therefore conducted in either cell culture flasks or cell culture plates to test as many compounds as possible on a small scale. However, GMP laboratories have to rely on pre-established protocols and aim to produce sufficient quantities of the finished product for cellular therapies. In recent years, several new GMP-compliant cultivation methods have been introduced, all with their own pros and cons, concerning costs, required personnel, and product size. These include cell factory flasks [47], bioreactors (wave bioreactor [54], Quantum Terumo [55, 56]), and culture bags in a closed cultivation system (CliniMACS Prodigy [57]). The introduction of closed cell culture bags and the understanding that vessel materials and geometry have a significant impact on the efficacy of the cell therapeutic products reflect the complexity scientists and clinicians face in protocol development. For a detailed analysis of the effect of the employed cultivation method on MoDC generation and functionality, please see the respective studies as well as Fekete et al. [58] and Guyre et al. [59].

Differentiation

The generation of MoDCs is split into two sections, whereby isolated monocytes are first differentiated over the course of 5–7 days, followed by induced maturation for an additional 2 days. The differentiation step typically relies on the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 [60], with the latter suppressing monocyte-derived macrophage generation and actively promoting generation of MoDCs via induction of DC-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN; CD209) [61, 62]. This combination is considered to be the “gold standard” in GMP facilities for MoDC differentiation, yet concentrations for both cytokines may range between 400 and 1,000 IU/mL [63, 64, 65, 66]. This first step typically requires 5–7 days and transforms monocytes into immature MoDCs. However, experimental studies were able to show that differentiation into immature MoDCs can already be seen after 24 h [30, 31, 32]. This could significantly reduce time, hands-on work, and costs to produce GMP-grade MoDCs for immunotherapy.

In contrast to monocytes, immature MoDCs gradually downregulate CD14 and CD163 as well as genes associated with cell adhesion such as E-cadherin, ICAM1 (CD54), and PECAM1 (CD31) [21]. Likewise, cytokines and their receptors such as TNFα, IL-6, IL-6R, IL-13RA1, IL-10RA, and IL-15 are also downregulated [21, 67, 68]. Meanwhile, costimulatory molecules including CD83, CD80, and CD86 as well as receptors associated with antigen uptake and processing (CD1a, LAMP1, HLA-DPA1, HLA-DQA2) are slowly upregulated [21]. Particularly DC-SIGN, which is required for the detection of high-mannose type N-glycans and phagocytosis [69], has been shown to be a reliable indicator in immature MoDCs for investigators, as CD14 expression may not decrease due to the used starting material [70, 71].

Maturation

The second step in the generation of MoDCs focuses on their maturation. In general, maturation leads to a significant upregulation of costimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD83, CD86, CD40, and MHC-II as well as molecules associated with lymph node homing (CCR7), whereas markers such as DC-SIGN are slightly downregulated [66, 72]. Upon maturation, MoDC should also secrete high concentrations of IL-12p70 and low levels of IL-10, which poses a hurdle for many DC vaccines. In order to induce maturation, several strategies can be employed which can rely on immunostimulatory molecules or pyrogens as well as cytokine cocktails. The composition of the used components for maturation significantly influences the functionality of the matured MoDCs [73] and may differ greatly between GMP laboratories. Common strategies to induce maturation include: TLR ligands such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or its less toxic derivate monophosphoryl lipid A, resiquimod (R848), TNFα and CD40L; IFNs (IFNα/IFNγ), and maturation cocktails such as IL-6, IL-1β, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and TNFα or its modification as well as LPS, CD40L, and IFNγ [74, 75].

Due to its bacterial origin, LPS has been used extensively in DC maturation, leading to an increase in CCL5 (RANTES), CCL4, CCL20, and CCL18, which are associated with the recruitment and trafficking of T cells, monocytes, granulocytes, natural killer cells, and mast cells [76]. However, gene and protein expression studies have shown that through the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitory factors, LPS-mediated effects are damped in a self-regulatory manner over time [77, 78]. Another common strategy relies on the use of TNFα/CD40L, resulting in the generation of TH2-polarizing MoDCs. Maturation with these factors leads to a heightened expression of IL-10R, IL-13R, CCL17, and GM-CSF receptor needed for TH2 cell differentiation [79, 80, 81].

IFNs represent integral factors in the initiation of innate and adaptive immune responses and have been shown to induce in vitro differentiation and maturation of MoDCs. Especially IFNγ has been shown to elicit strong IL-12 releases either alone or in combination with other compounds. In contrast to the previously described TNFα maturation, IFN exposure leads to an increase in CXCR3 ligand chemokines, IRF-1, and IL-15, leading to a predominant TH1 cell polarization [75, 82, 83].

Nowadays laboratories mostly rely on maturation cocktails to recreate the physiological environment of in vivo MoDC maturation. Due to synergistic and antagonistic effects of the used compounds, expression profiles are not the sum of the individual agents but rather the consequence of complex interactions between the addressed downstream pathways. The most frequently used “gold standard” maturation cocktail comprises TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and PGE2, which is built on the enhancement of TNFα-mediated proinflammatory effects. This cocktail leads to a marked induction of IL-13R, CXCR4, CCL17, and IL-6, but not IL-10R or GM-CSF receptor [84].

PGE2, a typical component of maturation cocktails associated with lymphocyte homing and DC migration, has been shown to hinder IL-12p70 secretion via induction of tolerogenic responses [66, 85, 86, 87]. These effects can be partially overcome through the additional exposure to TLR ligands such as LPS and R848 [88]. However, several groups use cocktails devoid of PGE2. One of these comprises IL-1β, TNFα, IFNα, IFNγ, and poly(I:C), focusing on TH1 maturation of MoDCs [84]. Another frequently used PGE2-free cocktail consists of IFNγ and LPS or its alternative monophosphoryl lipid A [47, 89]. Similar to the single use of IFNγ, this combinations leads to the release of TH1-inducing factors such as CCL3, CCL5, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-12 and is able to induce the attraction of various immune cells [84, 89].

Antigen Loading

The choice of antigen or antigens to be loaded onto MoDCs is crucial for vaccine efficacy. Again, a variety of strategies have been explored both in research and GMP facilities. So far, DC vaccines have not lived up to their hoped effect due to functional deficiencies, but also to weak immunogenicity of the chosen antigen [90].

Classically, immature MoDCs have been loaded ex vivo with specific tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) via pulsing with a combination of peptides or whole protein to induce expression and presentation. Most cancer vaccines so far rely on the use of defined and shared HLA-restricted TAAs, such as gp100, p53, and MART-1 [91, 92]. However, this relies on prior knowledge of the desired antigens and is susceptible to antigen loss of the targeted tumor. Using multiple antigens within a vaccine formulation might overcome tumor escape, elicit a broader spectrum of T cell responses, and is not limited to solid tumors.

In a different approach, tumor lysates were tested to increase the availability of immunogenic antigens, comprising lysates from tumor cell lines (e.g., KATO-III [65, 93]) or autologous patient tumor lysates [46, 47, 94]. Using cell lines provides the advantage of preparing readily available lysates in advance; however, again antigen loss of the patient's tumor cannot be addressed. Using tumor lysates from autologous tumor samples is advantageous in many ways due to the absence of HLA restriction, reduced cost, and time necessary for preparation as well as the presence of numerous neoantigens within the lysate. A recent publication by Boudousquié et al. [47] optimized the immunogenicity of tumor lysate by repeatedly freeze-thawing hypochloric acid-treated autologous tumor lysates. Here, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were brought to proliferation through coculture with oxidized lysate-pulsed MoDCs. Likewise, manufactured MoDCs could remain viable and immunogenic after cryopreservation and meet the criteria for ≥50 pg/mL IL-12p70 secretion. However, one drawback remains as tumor lysate formulations are limited to the treatment of solid tumors.

MoDC Modifications

In addition to the above-listed approaches in antigen loading, several groups sought out to switch off mechanisms that typically regulate or inhibit T cell activation. In recent years, the RNAi and CRISPR/Cas9 techniques have gained increasing interest, targeting for instance programmed death-ligand 1 and 2 in MoDCs to block cell-intrinsic immunosuppressive T cell priming [95]. Another option, which could be incorporated into preexisting protocols, lies in the overexpression of endogenous cytokines and chemokines, such as CD40L, CXCL9, and CXCL10 through viral [96, 97] or mRNA delivery, allowing autonomous maturation [98]. A new alternative has been introduced by Squadrito et al. where antigen loading is taking place after the administration of the vaccine, enabling in situ TAA presentation, without the need for biopsies or surgery [99, 100]. Here, MoDCs are modified with a lentivirus-encoded chimeric receptor, enabling the specific uptake of cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Extracellular vesicles carry a broad spectrum of TAAs both on the inside and outside of the vesicle. This formulation was shown to elicit CD8+ T cell proliferation in a murine setting and could show that the main route of activation was the result of cross-dressing, whereby preformed HLA-I TAA complexes within the extracellular vesicles were transferred to MoDCs. Sundarasetty et al. [101]have described another strategy, whereby monocytes are programmed to self-differentiate using integrase-defective lentiviral vectors. The lentiviral vector enables the coexpression of GM-CSF and IFNα and the immune dominant pp65 tegument antigen of the human cytomegalovirus [102]. Though the concern for lentiviral-based insertional mutagenesis into myeloid cells progenitors remains, preliminary results in humanized mice yielded the development of naïve and memory T cells, stimulated B cell proliferation, and spawned pp65-specific cellular and humoral (IgM and IgG) responses [14, 103, 104].

Current Therapies in Clinical Testing

Though genetically engineered cell therapies, such as chimeric antigen receptor T cells, have demonstrated clinical success, few clinical tested DC vaccines rely on functional modifications. Current phase 3 trials predominantly rely on the treatment of cancers using classical ex vivo generation and loading of DCs for malignancies for which surgical reduction is challenging or not an option. Chief among them are DC vaccines addressing glioblastoma multiforme. A phase 3 trial at Oslo University Hospital is currently testing DC vaccines loaded with mRNA from autologous tumor stem cells, survivin, and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) (NCT03548571). Following leukapheresis, patients (n = 60) receive radiotherapy and standard care including temozolomide. Prepared DC vaccines are administered via intradermal injection in varying intervals. Patients are thereafter monitored over the course of 2 years following inclusion. Another ongoing study includes newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients and tests an autologous tumor lysate loaded DC vaccine (DCVax-L) in addition to standard care, radiation, and chemotherapy (NCT00045968; Northwest Therapeutics). Patients receive both temozolomide and DCVax-L (n = 232) or temozolomide and placebo (n = 99) via six intradermal injections in the first year. The vaccine is administered twice in the second year. In case of tumor recurrence, all patients are allowed to receive DCVax-L. First results show a median overall survival of 23.1 months following surgery in comparison to 15–17 months in standard care [105]. Adverse grade 3 and 4 events were seen in 2.1% of patients receiving the vaccine treatment. Another multicenter phase 3 trial in Germany is currently evaluating the effectiveness of a RNA-loaded DC vaccine targeting uveal melanoma (NCT01983748). Patients (n = 200) are vaccinated 8 times (20 × 106 DCs per vaccination) by intravenous administration over the course of 2 years. Patient assessment is conducted every 3 months via skin, lymph node, and ophthalmological inspection as well as laboratory and abdominal sonography.

Outlook

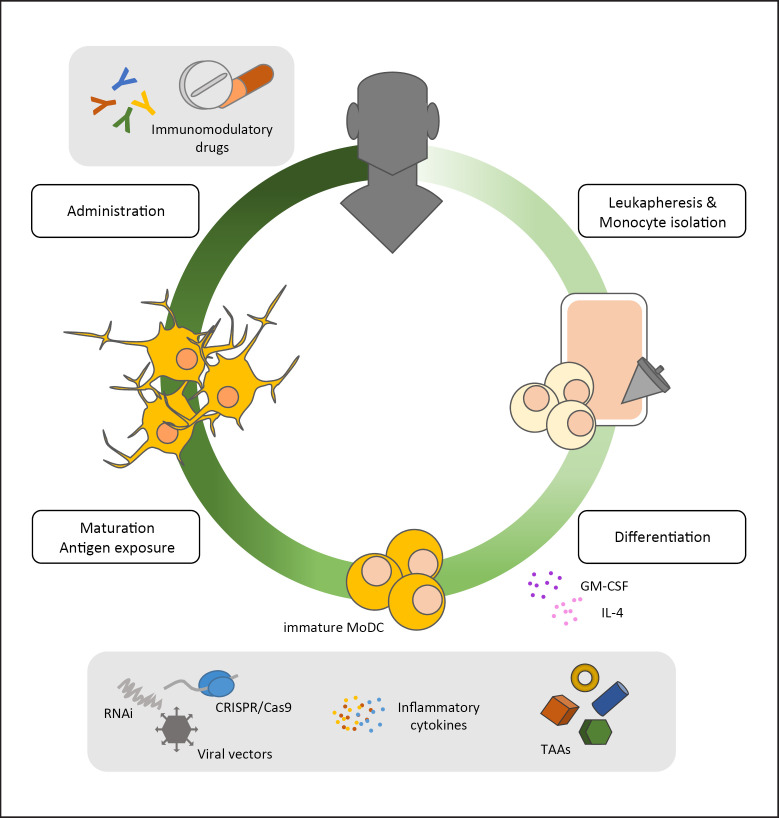

MoDCs are a versatile tool allowing patient-tailored vaccine formulations applicable for a broad range of cancers. Though cell therapies have demonstrated remarkable growing success in recent years, MoDC vaccines have yet to become a fully realized immunotherapy. As with other therapies, MoDC vaccines as a stand-alone treatment will not cure all cancer malignancies yet provide a powerful tool in concert with other treatments, such as immune checkpoint blockage and chemotherapy (Fig. 1). Likewise, researchers and clinicians have significantly broadened the spectrum and understanding of available methods to generate MoDCs with specific functional capabilities. The use of closed cultivation systems has significantly improved the reproducibility and safety of MoDC preparations. Further studies should continue to build on these advances to optimize and standardize the generation of MoDCs in order to maximize their therapeutic potential and operational readiness in clinical settings.

Fig. 1.

Manufacturing process of MoDCs. CD14+ monocytes are isolated from leukapheresis products of donors or patients and differentiated into immature MoDCs using GM-CSF and IL-4. Immature MoDCs are subsequently exposed to for instance TAAs, viral vectors, and inflammatory cytokines or are transcriptionally/genetically modified (RNAi, CRISPR/Cas9). Cells are subsequently matured and administered either alone or in combination with other immunomodulatory drugs (checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapeutic drugs). GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; MoDCs, monocyte-derived dendritic cells; TAAs, tumor-associated antigens.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

S. Cunningham conceived and wrote the manuscript. H. Hackstein conceived and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Starzl TE. History of clinical transplantation. World J Surg. 2000 Jul;24((7)):759–82. doi: 10.1007/s002680010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Rivière I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov. 2013 Apr;3((4)):388–98. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prieto PA, Durflinger KH, Wunderlich JR, Rosenberg SA, Dudley ME. Enrichment of CD8+ cells from melanoma tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures reveals tumor reactivity for use in adoptive cell therapy. J Immunother. 2010 Jun;33((5)):547–56. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181d367bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harzstark AL, Small EJ. Immunotherapy for prostate cancer using antigen-loaded antigen-presenting cells: APC8015 (Provenge) Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007 Aug;7((8)):1275–80. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.8.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31((1)):563–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemmi H, Akira S. “TLR Signalling and the Function of Dendritic Cells,” in Mechanisms of Epithelial Defense. Volume 86. Basel: KARGER; 2005. pp. pp. 120–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlitzer A, McGovern N, Ginhoux F. Dendritic cells and monocyte-derived cells: two complementary and integrated functional systems. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015 May;41:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joffre OP, Segura E, Savina A, Amigorena S. Cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012 Jul;12((8)):557–69. doi: 10.1038/nri3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collin M, Bigley V. Human dendritic cell subsets: an update. Immunology. 2018 May;154((1)):3–20. doi: 10.1111/imm.12888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.See P, Dutertre CA, Chen J, Günther P, McGovern N, Irac SE, et al. Mapping the human DC lineage through the integration of high-dimensional techniques. Science. 2017 Jun;356((6342)):eaag3009. doi: 10.1126/science.aag3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlitzer A, Ginhoux F. Organization of the mouse and human DC network. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014 Feb;26((1)):90–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baal N, Cunningham S, Obermann HL, Thomas J, Lippitsch A, Dietert K, et al. ADAR1 Is Required for Dendritic Cell Subset Homeostasis and Alveolar Macrophage Function. J Immunol. 2019 Feb;202((4)):1099–111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thurner B, Röder C, Dieckmann D, Heuer M, Kruse M, Glaser A, et al. Generation of large numbers of fully mature and stable dendritic cells from leukapheresis products for clinical application. J Immunol Methods. 1999 Feb;223((1)):1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daenthanasanmak A, Salguero G, Sundarasetty BS, Waskow C, Cosgun KN, Guzman CA, et al. Engineered dendritic cells from cord blood and adult blood accelerate effector T cell immune reconstitution against HCMV. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2015 Jan;1((November)):14060. doi: 10.1038/mtm.2014.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harada Y, Okada-Nakanishi Y, Ueda Y, Tsujitani S, Saito S, Fuji-Ogawa T, et al. Cytokine-based high log-scale expansion of functional human dendritic cells from cord-blood CD34-positive cells. Sci Rep. 2011;1((1)):174. doi: 10.1038/srep00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coillard A, Segura E. In vivo Differentiation of Human Monocytes. Front Immunol. 2019 Aug;10((August)):1907. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlitzer A, Sivakamasundari V, Chen J, Sumatoh HR, Schreuder J, Lum J, et al. Identification of cDC1- and cDC2-committed DC progenitors reveals early lineage priming at the common DC progenitor stage in the bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2015 Jul;16((7)):718–28. doi: 10.1038/ni.3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y, Liu CH, Roberts AI, Das J, Xu G, Ren G, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and T-cell responses: what we do and don't know. Cell Res. 2006 Feb;16((2)):126–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhn S, Ronchese F. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells: emerging players in the antitumor immune response. OncoImmunology. 2013 Nov;2((11)):e26443. doi: 10.4161/onci.26443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu K, Shen Q, Ulrich M, Zheng M. Human monocyte-derived dendritic cells expressing both chemotactic cytokines IL-8, MCP-1, RANTES and their receptors, and their selective migration to these chemokines. Chin Med J (Engl) 2000 Dec;113((12)):1124–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schinnerling K, García-González P, Aguillón JC. Gene Expression Profiling of Human Monocyte-derived Dendritic Cells - Searching for Molecular Regulators of Tolerogenicity. Front Immunol. 2015 Oct;6((OCT)):528. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinbrink K, Wölfl M, Jonuleit H, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of tolerance by IL-10-treated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997 Nov;159((10)):4772–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fogel-Petrovic M, Long JA, Misso NL, Foster PS, Bhoola KD, Thompson PJ. Physiological concentrations of transforming growth factor β1 selectively inhibit human dendritic cell function. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007 Dec;7((14)):1924–33. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia CQ, Peng R, Beato F, Clare-Salzler MJ. Dexamethasone induces IL-10-producing monocyte-derived dendritic cells with durable immaturity. Scand J Immunol. 2005 Jul;62((1)):45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedoric B, Krishnan R. Rapamycin downregulates the inhibitory receptors ILT2, ILT3, ILT4 on human dendritic cells and yet induces T cell hyporesponsiveness independent of FoxP3 induction. Immunol Lett. 2008 Oct;120((1-2)):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers NM, Kireta S, Coates PT. Curcumin induces maturation-arrested dendritic cells that expand regulatory T cells in vitro and in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010 Dec;162((3)):460–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zapata-Gonzalez F, Rueda F, Petriz J, Domingo P, Villarroya F, de Madariaga A, et al. 9-cis-Retinoic acid (9cRA), a retinoid X receptor (RXR) ligand, exerts immunosuppressive effects on dendritic cells by RXR-dependent activation: inhibition of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ blocks some of the 9cRA activities, and precludes them to mature phenotype development. J Immunol. 2007 May;178((10)):6130–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilkens CM, Isaacs JD. Tolerogenic dendritic cell therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: where are we now? Clin Exp Immunol. 2013 May;172((2)):148–57. doi: 10.1111/cei.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinbrink K, Graulich E, Kubsch S, Knop J, Enk AH. CD4(+) and CD8(+) anergic T cells induced by interleukin-10-treated human dendritic cells display antigen-specific suppressor activity. Blood. 2002 Apr;99((7)):2468–76. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willekens B, Presas-Rodríguez S, Mansilla MJ, Derdelinckx J, Lee WP, Nijs G, et al. RESTORE consortium Tolerogenic dendritic cell-based treatment for multiple sclerosis (MS): a harmonised study protocol for two phase I clinical trials comparing intradermal and intranodal cell administration. BMJ Open. 2019 Sep;9((9)):e030309. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007 Aug;7((8)):610–21. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hopewell EL, Cox C. Manufacturing Dendritic Cells for Immunotherapy: monocyte Enrichment. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020 Jan;16((March)):155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berger TG, Strasser E, Smith R, Carste C, Schuler-Thurner B, Kaempgen E, et al. Efficient elutriation of monocytes within a closed system (Elutra) for clinical-scale generation of dendritic cells. J Immunol Methods. 2005 Mar;298((1-2)):61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Almeida MC, Silva AC, Barral A, Barral Netto M. A simple method for human peripheral blood monocyte isolation. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000 Mar-Apr;95((2)):221–3. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762000000200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delirezh N, Shojaeefar E, Parvin P, Asadi B. Comparison the effects of two monocyte isolation methods, plastic adherence and magnetic activated cell sorting methods, on phagocytic activity of generated dendritic cells. Cell J. 2013;15((3)):218–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felzmann T, Witt V, Wimmer D, Ressmann G, Wagner D, Paul P, et al. Monocyte enrichment from leukapharesis products for the generation of DCs by plastic adherence, or by positive or negative selection. Cytotherapy. 2003;5((5)):391–8. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patarroyo M, Prieto J, Beatty PG, Clark EA, Gahmberg CG. Adhesion-mediating molecules of human monocytes. Cell Immunol. 1988 May;113((2)):278–89. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janssen WE, Ribickas A, Meyer LV, Smilee RC. Large-scale Ficoll gradient separations using a commercially available, effectively closed, system. Cytotherapy. 2010 May;12((3)):418–24. doi: 10.3109/14653240903479663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Law P, Dooley DC, Alsop P, Smith DM, Landmark JD, Meryman HT. Density gradient isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells using a blood cell processor. Transfusion. 1988 Mar-Apr;28((2)):145–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1988.28288179019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faradji A, Bohbot A, Schmitt-Goguel M, Siffert JC, Dumont S, Wiesel ML, et al. Large scale isolation of human blood monocytes by continuous flow centrifugation leukapheresis and counterflow centrifugation elutriation for adoptive cellular immunotherapy in cancer patients. J Immunol Methods. 1994 Sep;174((1-2)):297–309. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morijiri T, Yamada M, Hikida T, Seki M. Microfluidic counterflow centrifugal elutriation system for sedimentation-based cell separation. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 2013 Jun;14((6)):1049–57. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strasser EF, Eckstein R. Optimization of leukocyte collection and monocyte isolation for dendritic cell culture. Transfus Med Rev. 2010 Apr;24((2)):130–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stroncek DF, Fellowes V, Pham C, Khuu H, Fowler DH, Wood LV, et al. Counter-flow elutriation of clinical peripheral blood mononuclear cell concentrates for the production of dendritic and T cell therapies. J Transl Med. 2014 Sep;12((1)):241. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0241-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarnjak-Jankovic S, Hammerstad H, Saebøe-Larssen S, Kvalheim G, Gaudernack G. A full scale comparative study of methods for generation of functional Dendritic cells for use as cancer vaccines. BMC Cancer. 2007 Jul;7((1)):119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bauer J. Advances in cell separation: recent developments in counterflow centrifugal elutriation and continuous flow cell separation. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1999 Feb;722((1-2)):55–69. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eyrich M, Schreiber SC, Rachor J, Krauss J, Pauwels F, Hain J, et al. Development and validation of a fully GMP-compliant production process of autologous, tumor-lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Cytotherapy. 2014 Jul;16((7)):946–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boudousquié C, Boand V, Lingre E, Dutoit L, Balint K, Danilo M, et al. Development and Optimization of a GMP-Compliant Manufacturing Process for a Personalized Tumor Lysate Dendritic Cell Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel) 2020 Jan;8((1)):25. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu Z, Zhang Z, Lei Z, Lei P. CD14: biology and role in the pathogenesis of disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2019 Aug;48:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elkord E, Williams PE, Kynaston H, Rowbottom AW. Human monocyte isolation methods influence cytokine production from in vitro generated dendritic cells. Immunology. 2005 Feb;114((2)):204–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalinski P, Muthuswamy R, Urban J. Dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy: vaccines and combination immunotherapies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2013 Mar;12((3)):285–95. doi: 10.1586/erv.13.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knutson KL, Disis ML. Tumor antigen-specific T helper cells in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005 Aug;54((8)):721–8. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu JM, Zhu Y, Xu ZW, Ouyang WM, Wang JP, Liu XS, et al. Dynamic changes of apoptosis-inducing ligands and Th1/Th2 like subpopulations in Hantaan virus-induced hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2006 Jun;119((3)):245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang Y, Yu S, Ellis JS, Sharav T, Braley-Mullen H. Comparison of sensitivity of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2010 Jun;87((6)):1019–28. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0509352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meng Y, Sun J, Hu T, Ma Y, Du T, Kong C, et al. Rapid expansion in the WAVE bioreactor of clinical scale cells for tumor immunotherapy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14((10)):2516–26. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1480241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uslu U, Erdmann M, Wiesinger M, Schuler G, Schuler-Thurner B. Automated Good Manufacturing Practice-compliant generation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells from a complete apheresis product using a hollow-fiber bioreactor system overcomes a major hurdle in the manufacture of dendritic cells for cancer vaccines. Cytotherapy. 2019 Nov;21((11)):1166–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Startz T, Nguyen K, Peters R, Nankervis B, Jones M, Kilian R, et al. Maturation of dendritic cells from CD14+ monocytes in an automated functionally closed hollow fiber bioreactor system. Cytotherapy. 2014 Apr;16((4)):S29. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erdmann M, Uslu U, Wiesinger M, Brüning M, Altmann T, Strasser E, et al. Automated closed-system manufacturing of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunol Methods. 2018 Dec;463((September)):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fekete N, Béland AV, Campbell K, Clark SL, Hoesli CA. Bags versus flasks: a comparison of cell culture systems for the production of dendritic cell-based immunotherapies. Transfusion. 2018 Jul;58((7)):1800–13. doi: 10.1111/trf.14621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guyre CA, Fisher JL, Waugh MG, Wallace PK, Tretter CG, Ernstoff MS, et al. Advantages of hydrophobic culture bags over flasks for the generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells for clinical applications. J Immunol Methods. 2002 Apr;262((1-2)):85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Markowicz S, Engleman EG. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor promotes differentiation and survival of human peripheral blood dendritic cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1990 Mar;85((3)):955–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI114525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roy KC, Bandyopadhyay G, Rakshit S, Ray M, Bandyopadhyay S. IL-4 alone without the involvement of GM-CSF transforms human peripheral blood monocytes to a CD1a(dim), CD83(+) myeloid dendritic cell subset. J Cell Sci. 2004 Jul;117((Pt 16)):3435–45. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Relloso M, Puig-Kröger A, Pello OM, Rodríguez-Fernández JL, de la Rosa G, Longo N, et al. DC-SIGN (CD209) expression is IL-4 dependent and is negatively regulated by IFN, TGF-β, and anti-inflammatory agents. J Immunol. 2002 Mar;168((6)):2634–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vopenkova K, Mollova K, Buresova I, Michalek J. Complex evaluation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells for cancer immunotherapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2012 Nov;16((11)):2827–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nair S, Archer GE, Tedder TF. Isolation and generation of human dendritic cells. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2012 Nov;Chapter 7((1)):32. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0732s99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schnurr M, Galambos P, Scholz C, Then F, Dauer M, Endres S, et al. Tumor cell lysate-pulsed human dendritic cells induce a T-cell response against pancreatic carcinoma cells: an in vitro model for the assessment of tumor vaccines. Cancer Res. 2001 Sep;61((17)):6445–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dauer M, Obermaier B, Herten J, Haerle C, Pohl K, Rothenfusser S, et al. Mature dendritic cells derived from human monocytes within 48 hours: a novel strategy for dendritic cell differentiation from blood precursors. J Immunol. 2003 Apr;170((8)):4069–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Le Naour F, Hohenkirk L, Grolleau A, Misek DE, Lescure P, Geiger JD, et al. Profiling changes in gene expression during differentiation and maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells using both oligonucleotide microarrays and proteomics. J Biol Chem. 2001 May;276((21)):17920–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Angénieux C, Fricker D, Strub JM, Luche S, Bausinger H, Cazenave JP, et al. Gene induction during differentiation of human monocytes into dendritic cells: an integrated study at the RNA and protein levels. Funct Integr Genomics. 2001 Sep;1((5)):323–9. doi: 10.1007/s101420100037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McGreal EP, Miller JL, Gordon S. Ligand recognition by antigen-presenting cell C-type lectin receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005 Feb;17((1)):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Engering A, Geijtenbeek TB, van Vliet SJ, Wijers M, van Liempt E, Demaurex N, et al. The dendritic cell-specific adhesion receptor DC-SIGN internalizes antigen for presentation to T cells. J Immunol. 2002 Mar;168((5)):2118–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hosszu KK, Valentino A, Vinayagasundaram U, Vinayagasundaram R, Joyce MG, Ji Y, et al. DC-SIGN, C1q, and gC1qR form a trimolecular receptor complex on the surface of monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells. Blood. 2012 Aug;120((6)):1228–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-369728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Monrad SU, Rea K, Thacker S, Kaplan MJ. Myeloid dendritic cells display downregulation of C-type lectin receptors and aberrant lectin uptake in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10((5)):R114. doi: 10.1186/ar2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zobywalski A, Javorovic M, Frankenberger B, Pohla H, Kremmer E, Bigalke I, et al. Generation of clinical grade dendritic cells with capacity to produce biologically active IL-12p70. J Transl Med. 2007 Apr;5((1)):18. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Massa C, Thomas C, Wang E, Marincola F, Seliger B. Different maturation cocktails provide dendritic cells with different chemoattractive properties. J Transl Med. 2015 Jun;13((1)):175. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0528-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Castiello L, Sabatino M, Jin P, Clayberger C, Marincola FM, Krensky AM, et al. Monocyte-derived DC maturation strategies and related pathways: a transcriptional view. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011 Apr;60((4)):457–66. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0954-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Appay V, Rowland-Jones SL. RANTES: a versatile and controversial chemokine. Trends Immunol. 2001 Feb;22((2)):83–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01812-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu X, Yee E, Harlan JM, Wong F, Karsan A. Lipopolysaccharide induces the antiapoptotic molecules, A1 and A20, in microvascular endothelial cells. Blood. 1998 Oct;92((8)):2759–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen P, Li J, Barnes J, Kokkonen GC, Lee JC, Liu Y. Restraint of proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis by mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J Immunol. 2002 Dec;169((11)):6408–16. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Messmer D, Messmer B, Chiorazzi N. The global transcriptional maturation program and stimuli-specific gene expression profiles of human myeloid dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2003 Apr;15((4)):491–503. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Korthals M, Safaian N, Kronenwett R, Maihöfer D, Schott M, Papewalis C, et al. Monocyte derived dendritic cells generated by IFN-α acquire mature dendritic and natural killer cell properties as shown by gene expression analysis. J Transl Med. 2007 Sep;5((1)):46. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Matsunaga T, Ishida T, Takekawa M, Nishimura S, Adachi M, Imai K. Analysis of gene expression during maturation of immature dendritic cells derived from peripheral blood monocytes. Scand J Immunol. 2002 Dec;56((6)):593–601. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schlaak JF, Hilkens CM, Costa-Pereira AP, Strobl B, Aberger F, Frischauf AM, et al. Cell-type and donor-specific transcriptional responses to interferon-α. Use of customized gene arrays. J Biol Chem. 2002 Dec;277((51)):49428–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Longhi MP, Trumpfheller C, Idoyaga J, Caskey M, Matos I, Kluger C, et al. Dendritic cells require a systemic type I interferon response to mature and induce CD4+ Th1 immunity with poly IC as adjuvant. J Exp Med. 2009 Jul;206((7)):1589–602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Möller I, Michel K, Frech N, Burger M, Pfeifer D, Frommolt P, et al. Dendritic cell maturation with poly(I:C)-based versus PGE2-based cytokine combinations results in differential functional characteristics relevant to clinical application. J Immunother. 2008 Jun;31((5)):506–19. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318177d9e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaliński P, Vieira PL, Schuitemaker JH, de Jong EC, Kapsenberg ML. Prostaglandin E(2) is a selective inducer of interleukin-12 p40 (IL-12p40) production and an inhibitor of bioactive IL-12p70 heterodimer. Blood. 2001 Jun;97((11)):3466–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Luft T, Jefford M, Luetjens P, Toy T, Hochrein H, Masterman KA, et al. Functionally distinct dendritic cell (DC) populations induced by physiologic stimuli: prostaglandin E(2) regulates the migratory capacity of specific DC subsets. Blood. 2002 Aug;100((4)):1362–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells under the spell of prostaglandins. Trends Immunol. 2003 Mar;24((3)):108–11. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dauer M, Lam V, Arnold H, Junkmann J, Kiefl R, Bauer C, et al. Combined use of toll-like receptor agonists and prostaglandin E(2) in the FastDC model: rapid generation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells capable of migration and IL-12p70 production. J Immunol Methods. 2008 Sep;337((2)):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jin P, Han TH, Ren J, Saunders S, Wang E, Marincola FM, et al. Molecular signatures of maturing dendritic cells: implications for testing the quality of dendritic cell therapies. J Transl Med. 2010 Jan;8((1)):4. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mastelic-Gavillet B, Balint K, Boudousquie C, Gannon PO, Kandalaft LE. Personalized Dendritic Cell Vaccines-Recent Breakthroughs and Encouraging Clinical Results. Front Immunol. 2019 Apr;10((APR)):766. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schuler PJ, Harasymczuk M, Visus C, Deleo A, Trivedi S, Lei Y, et al. Phase I dendritic cell p53 peptide vaccine for head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014 May;20((9)):2433–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Di Pucchio T, Pilla L, Capone I, Ferrantini M, Montefiore E, Urbani F, et al. Immunization of stage IV melanoma patients with Melan-A/MART-1 and gp100 peptides plus IFN-α results in the activation of specific CD8(+) T cells and monocyte/dendritic cell precursors. Cancer Res. 2006 May;66((9)):4943–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Copier J, Dalgleish A. Overview of tumor cell-based vaccines. Int Rev Immunol. 2006 Sep-Dec;25((5-6)):297–319. doi: 10.1080/08830180600992472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim JH, Lee Y, Bae YS, Kim WS, Kim K, Im HY, et al. Phase I/II study of immunotherapy using autologous tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Immunol. 2007 Dec;125((3)):257–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hobo W, Maas F, Adisty N, de Witte T, Schaap N, van der Voort R, et al. siRNA silencing of PD-L1 and PD-L2 on dendritic cells augments expansion and function of minor histocompatibility antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2010 Nov;116((22)):4501–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Knippertz I, Hesse A, Schunder T, Kämpgen E, Brenner MK, Schuler G, et al. Generation of human dendritic cells that simultaneously secrete IL-12 and have migratory capacity by adenoviral gene transfer of hCD40L in combination with IFN-γ. J Immunother. 2009 Jun;32((5)):524–38. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a28422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Koya RC, Kasahara N, Favaro PM, Lau R, Ta HQ, Weber JS, et al. Potent maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells after CD40L lentiviral gene delivery. J Immunother. 2003 Sep-Oct;26((5)):451–60. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wilgenhof S, Corthals J, Heirman C, van Baren N, Lucas S, Kvistborg P, et al. Phase II Study of Autologous Monocyte-Derived mRNA Electroporated Dendritic Cells (TriMixDC-MEL) Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Pretreated Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr;34((12)):1330–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Squadrito ML, Cianciaruso C, Hansen SK, De Palma M. EVIR: chimeric receptors that enhance dendritic cell cross-dressing with tumor antigens. Nat Methods. 2018 Mar;15((3)):183–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Perez CR, De Palma M. Engineering dendritic cell vaccines to improve cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2019 Nov;10((1)):5408. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13368-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sundarasetty BS, Kloess S, Oberschmidt O, Naundorf S, Kuehlcke K, Daenthanasanmak A, et al. Generation of lentivirus-induced dendritic cells under GMP-compliant conditions for adaptive immune reconstitution against cytomegalovirus after stem cell transplantation. J Transl Med. 2015 Jul;13((1)):240. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0599-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Daenthanasanmak A, Salguero G, Borchers S, Figueiredo C, Jacobs R, Sundarasetty BS, et al. Integrase-defective lentiviral vectors encoding cytokines induce differentiation of human dendritic cells and stimulate multivalent immune responses in vitro and in vivo. Vaccine. 2012 Jul;30((34)):5118–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bialek-Waldmann JK, Heuser M, Ganser A, Stripecke R. Monocytes reprogrammed with lentiviral vectors co-expressing GM-CSF, IFN-α2 and antigens for personalized immune therapy of acute leukemia pre- or post-stem cell transplantation. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019 Nov;68((11)):1891–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02406-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Salguero G, Daenthanasanmak A, Münz C, Raykova A, Guzmán CA, Riese P, et al. Dendritic cell-mediated immune humanization of mice: implications for allogeneic and xenogeneic stem cell transplantation. J Immunol. 2014 May;192((10)):4636–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liau LM, Ashkan K, Tran DD, Campian JL, Trusheim JE, Cobbs CS, et al. First results on survival from a large Phase 3 clinical trial of an autologous dendritic cell vaccine in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Transl Med. 2018 May;16((1)):142. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]