PURPOSE

Maintenance therapy prolongs progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) not undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) but has generally been limited to immunomodulatory agents. Other options that complement the induction regimen with favorable toxicity are needed.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled TOURMALINE-MM4 study randomly assigned (3:2) patients with NDMM not undergoing ASCT who achieved better than or equal to partial response after 6-12 months of standard induction therapy to receive the oral proteasome inhibitor (PI) ixazomib or placebo on days 1, 8, and 15 of 28-day cycles as maintenance for 24 months. The primary endpoint was PFS since time of randomization.

RESULTS

Patients were randomly assigned to receive ixazomib (n = 425) or placebo (n = 281). TOURMALINE-MM4 met its primary endpoint with a 34.1% reduction in risk of progression or death with ixazomib versus placebo (median PFS since randomization, 17.4 v 9.4 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.659; 95% CI, 0.542 to 0.801; P < .001; median follow-up, 21.1 months). Ixazomib significantly benefitted patients who achieved complete or very good partial response postinduction (median PFS, 25.6 v 12.9 months; HR, 0.586; P < .001). With ixazomib versus placebo, 36.6% versus 23.2% of patients had grade ≥ 3 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs); 12.9% versus 8.0% discontinued treatment because of TEAEs. Common any-grade TEAEs included nausea (26.8% v 8.0%), vomiting (24.2% v 4.3%), and diarrhea (23.2% v 12.3%). There was no increase in new primary malignancies (5.2% v 6.2%); rates of on-study deaths were 2.6% versus 2.2%.

CONCLUSION

Ixazomib maintenance prolongs PFS with no unexpected toxicity in patients with NDMM not undergoing ASCT. To our knowledge, this is the first PI demonstrated in a randomized clinical trial to have single-agent efficacy for maintenance and is the first oral PI option in this patient population.

INTRODUCTION

Treatment for multiple myeloma (MM) is shifting increasingly to maintenance and continuous therapy, which improves outcomes versus fixed-duration treatment followed by a remission period.1-3 Real-world data suggest that, at relapse, approximately one third of patients never receive second-line treatment,4,5 highlighting the importance of maximizing progression-free survival (PFS) with initial therapy and the need for tolerable, active treatment options for long-term administration.6 Proteasome inhibitors (PIs), immunomodulatory drugs, and monoclonal antibodies are backbones of therapy for MM.7 However, there are no approved maintenance or continuous therapy options with PIs for initial therapy.8,9

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Does the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib improve progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) not undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation when used as maintenance therapy after best response to any standard-of-care induction?

Knowledge Generated

Treatment with weekly ixazomib maintenance resulted in a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in PFS since randomization, with an 8-month increase in the median, and demonstrated PFS benefits in prespecified patient subgroups, including a statistically significant benefit in patients who achieved complete or very good partial responses to initial therapy, and benefits in patients with stage IIII disease, patients aged ≥ 75 years, and patients with expanded high-risk cytogenetics. Ixazomib maintenance had a tolerable safety profile with no increase in health care use or impact on patients’ self-reported quality of life as measured by European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ)-Core 30 and EORTC QLQ-MY20 questionnaires.

Relevance

To our knowledge, ixazomib is the first induction-agnostic maintenance option investigated for transplantation-ineligible patients with NDMM and represents a valuable treatment option in this setting.

Maintenance therapy prolongs PFS in the post-transplantation and nontransplantation settings, and overall survival (OS) when used post-transplantation.10-12 To date, only lenalidomide is approved as post-transplantation maintenance therapy.13 There are currently no agents specifically approved as maintenance after any standard-of-care induction therapy for patients not undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). These patients may receive continuous treatment with one or more agents received as induction, such as lenalidomide9,14,15 and/or daratumumab.8,16 In routine clinical practice, treatment duration may be limited because of toxicity and route of administration.6,17 More tolerable and convenient options are required for this generally elderly population, who may not be eligible for transplantation because of age or presence of comorbidities.18

The oral PI ixazomib is approved in combination with lenalidomide-dexamethasone for the treatment of patients with MM who have received one prior therapy.19 Ixazomib as post-transplantation maintenance therapy prolongs PFS versus placebo,20 with limited cumulative toxicity or impact on quality of life (QoL).20,21 We report the efficacy and safety of ixazomib as maintenance therapy in transplantation-ineligible patients after standard-of-care induction therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Trial Design and Patients

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial, patients were randomly assigned from April 23, 2015, through October 8, 2018, at 187 sites in 34 countries (Data Supplement, online only). The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and appropriate regulatory requirements. Local independent ethics committees or institutional review boards at each site approved the protocol, which is available in the Data Supplement. All patients provided written informed consent.

Adults with a confirmed diagnosis of symptomatic MM per International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria22 who were ineligible for, or did not wish to receive, ASCT and who achieved at least a partial response (PR) as their best response after 6-12 months of any standard-of-care induction therapy, were eligible. Patients required an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2 and documented initial disease state, initial therapy and response, and cytogenetics and International Staging System (ISS) disease stage assessments at diagnosis (Data Supplement). Eligible patients were required to be randomly assigned ≤ 60 days after the last dose of induction therapy.

Procedures

Using centralized randomization through an interactive voice/web response system (Data Supplement), patients were randomly assigned 3:2 to receive either oral ixazomib 3 mg or matching placebo on days 1, 8, and 15 of 28-day cycles. The dose was increased to 4 mg from cycle 5 if tolerated during cycles 1-4 (Data Supplement). Randomization was stratified by induction regimen (PI-containing v non-PI therapy); preinduction ISS disease stage (I or II v III); age at randomization (< 75 v ≥ 75 years); and response to initial therapy at screening (complete response [CR] or very good partial response [VGPR] v PR). Patients continued treatment for approximately 24 months (if no treatment delays, equivalent to 26 cycles, to the nearest complete cycle) or until progressive disease (PD) or unacceptable toxicity, whichever occurred first. Dose adjustments for toxicities were permitted using protocol-specified dose-modification guidelines.

Outcomes and Assessments

The primary endpoint was PFS, defined as time since random assignment to first documentation of PD (per independent review committee [IRC] evaluation) or death as a result of any cause. The key secondary endpoint was OS. Secondary and exploratory endpoints are listed in the Data Supplement.

Patient evaluations and follow-up are summarized in the Data Supplement. Response was assessed on day 1 of every treatment cycle and every 4 weeks during the PFS follow-up period until PD. Response and PD were evaluated by an IRC blinded to both treatment assignment and investigator assessment of response; assessments were based on central laboratory M-protein results, plus local bone marrow and imaging data, using IMWG 2011 criteria.23 Adverse events (AEs) were assessed throughout the treatment period and through 30 days after the last dose of the study drug and graded according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03. For more details on assessments, see the Data Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

The study used a closed sequential testing procedure for the primary (PFS) and key secondary (OS) endpoints, in this order. Two interim analyses (IAs), plus a final analysis, were planned to test OS; the first IA, reported here, was the primary and only analysis of PFS. See the Data Supplement for detailed statistical analysis methodology. At this analysis, the study had 90% power to detect a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.71 (two-sided log-rank test, two-sided alpha of .04) for PFS in the intention-to-treat-population. Additionally, PFS was tested in parallel in three prespecified subgroups per stratification variables: patients with preinduction ISS stage III disease, patients aged ≥ 75 years, and patients who achieved CR or VGPR with initial therapy. Subgroup testing for PFS was conducted using the remaining alpha (.01) and the Hochberg procedure for multiplicity correction (Data Supplement). The study was not powered for statistical testing in other prespecified subgroups. The O’Brien-Fleming alpha spending function (Lan-Demets method24) was used to calculate the significance boundary for OS on the basis of the observed number of deaths at each IA. All other efficacy endpoints were tested at a two-sided alpha level of .05. Analysis populations are defined in the Data Supplement.

RESULTS

Patients

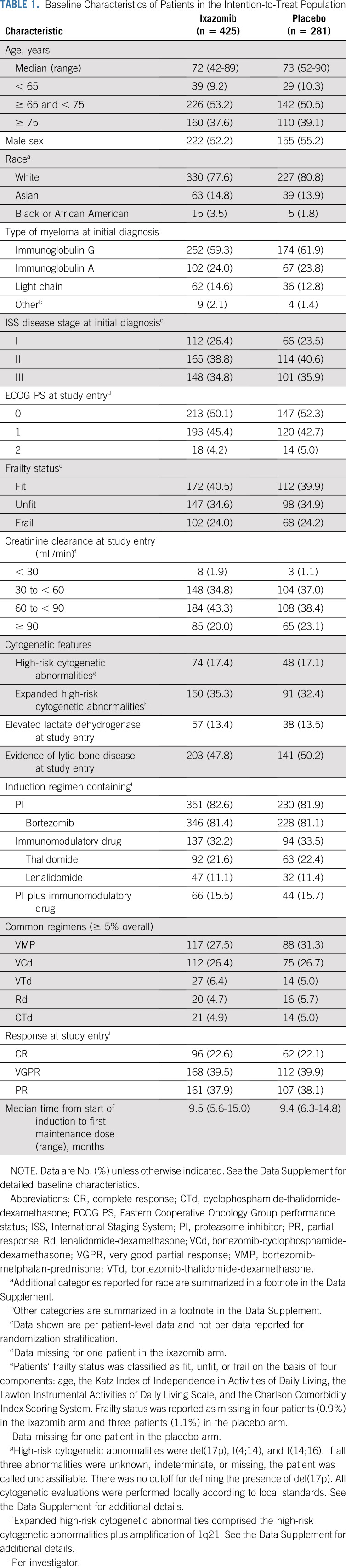

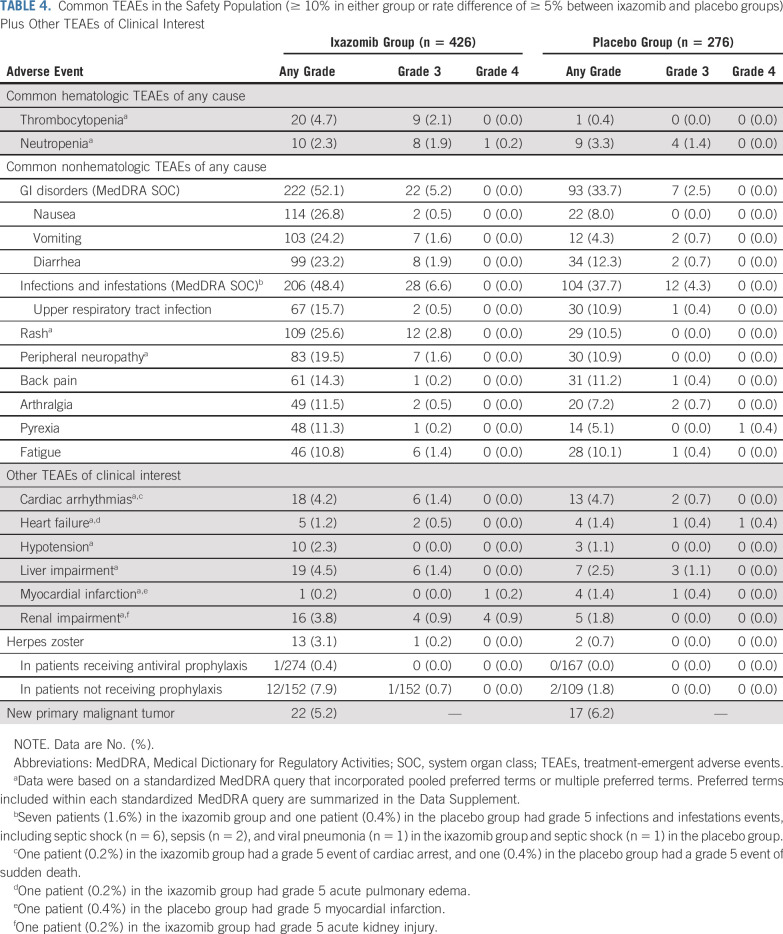

A total of 706 patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) were enrolled (Fig 1), 425 in the ixazomib arm and 281 in the placebo arm. Baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics, including prior induction treatment, were well balanced between groups (Table 1; Data Supplement). Overall median age at study entry was 73 years, with 38.2% of patients aged ≥ 75 years; 35.3% of patients had ISS stage III disease, 82.3% received a PI and 32.7% received an immunomodulatory drug as part of their induction regimen, and 62.0% were in CR or VGPR at study entry.

FIG 1.

CONSORT diagram.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients in the Intention-to-Treat Population

Efficacy

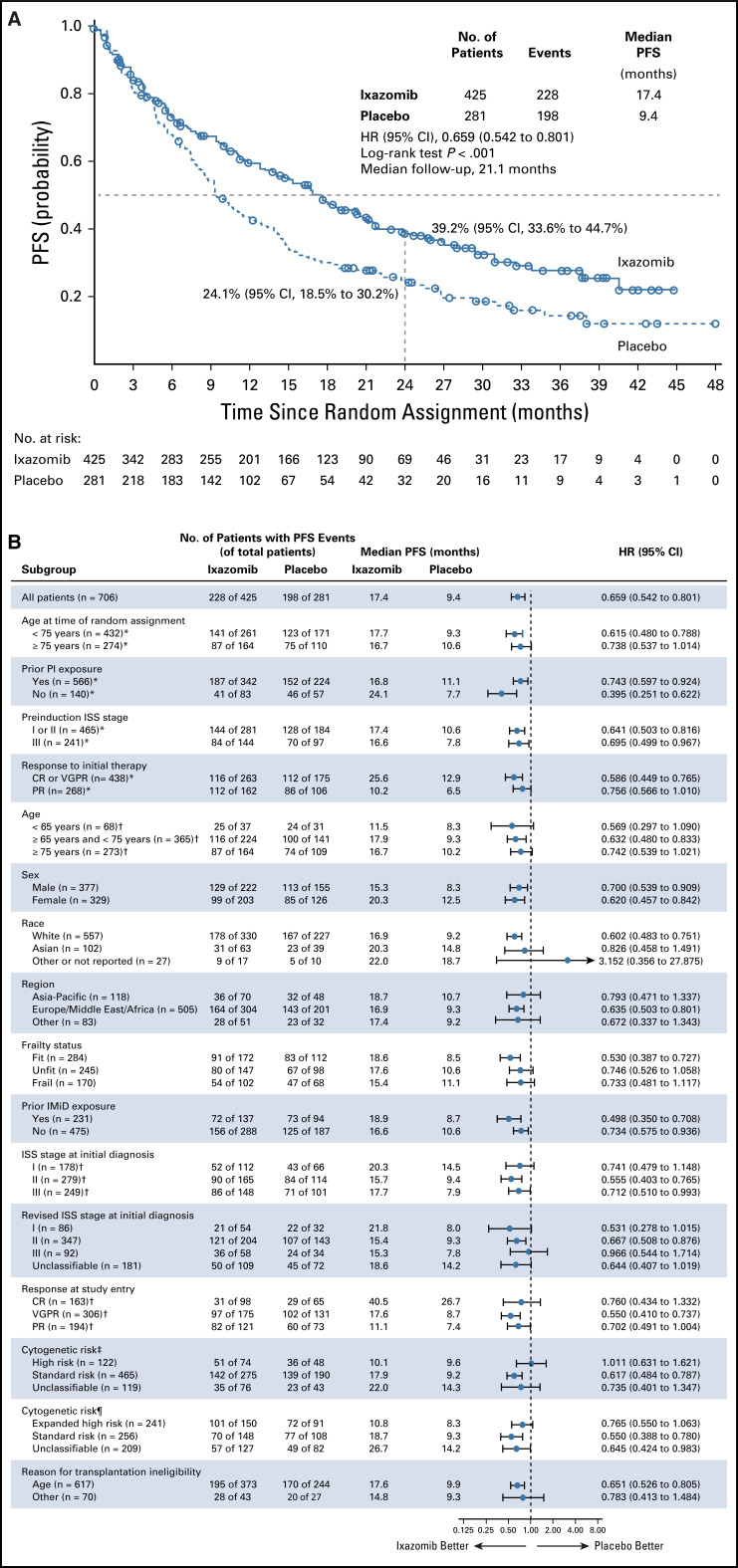

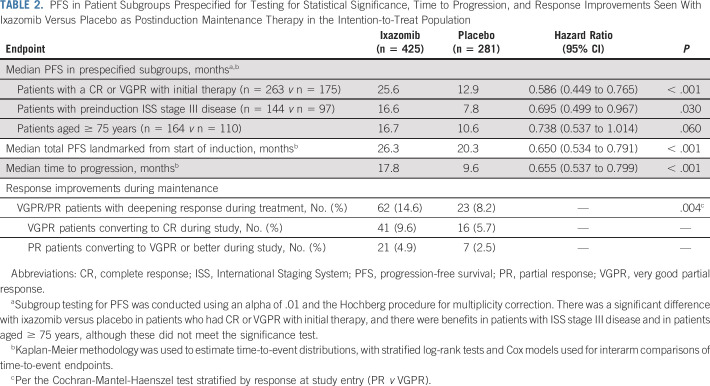

At data cutoff (August 12, 2019), with a median overall follow-up for PFS of 21.1 months, there was a significant 34.1% reduction in risk of progression or death in the ixazomib versus placebo group (HR, 0.659; 95% CI, 0.542 to 0.801; P < .001); median PFS since randomization was 17.4 months (95% CI, 14.8 to 20.3 months) versus 9.4 months (95% CI, 8.5 to 11.5 months; Fig 2A). When landmarked to the date of induction therapy, median total PFS time since start of induction was 26.3 versus 20.3 months in the ixazomib versus placebo group (Table 2). In the prespecified subgroups, there was a statistically significant improvement in PFS since randomization with ixazomib versus placebo in patients who achieved CR or VGPR with initial therapy (HR, 0.586; 95% CI, 0.449 to 0.765; P < .001). Clinical benefits were observed in patients with ISS stage III disease (HR, 0.695; 95% CI, 0.499 to 0.967; P = .030) and patients aged ≥ 75 years (HR, 0.738; 95% CI, 0.537 to 1.014; P = .060; Table 2). PFS benefit in other patient subgroups is summarized in Figure 2B.

FIG 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of progression-free survival (PFS) by independent review (A) in the intention-to-treat population and (B) by prespecified patient subgroups. Stratified log-rank tests and Cox models were used for interarm comparisons. Some subgroup data are not shown because of small patient numbers. (*) Data per stratification variables. (†) Data per individual patient-level clinical data after medical review. (‡) High-risk cytogenetic abnormalities were del(17p), t(4;14), and t(14;16). See the Data Supplement for additional details. (¶) Expanded high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities comprised the high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities plus amplification of 1q21. See the Data Supplement for additional details. CR, complete response; HR, hazard ratio; IMiD, immunomodulatory drug; ISS, International Staging System; PI, proteasome inhibitor; PR, partial response; VGPR, very good partial response.

TABLE 2.

PFS in Patient Subgroups Prespecified for Testing for Statistical Significance, Time to Progression, and Response Improvements Seen With Ixazomib Versus Placebo as Postinduction Maintenance Therapy in the Intention-to-Treat Population

Median time to progression was 17.8 versus 9.6 months with ixazomib versus placebo, and response improvements during maintenance were seen in 14.6% versus 8.2% of patients (Table 2). PFS2 and OS data were not mature at the time of this analysis. The study remains blinded; follow-up for PFS2 and OS continues.

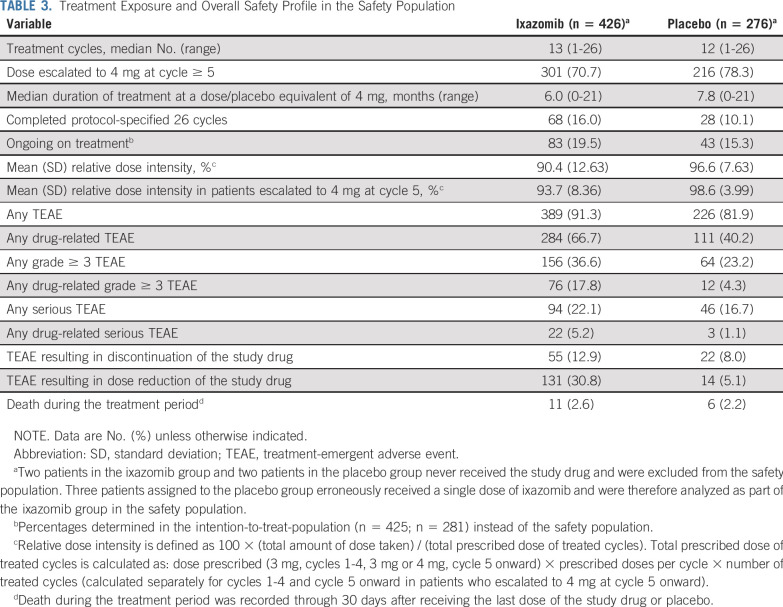

Treatment Exposure and Safety

The safety population included 426 and 276 patients in the ixazomib and placebo groups, respectively (Fig 1). Treatment exposure data are summarized in Table 3. At data cutoff, patients had received a median of 13 (1 to 26) and 12 (1 to 26) treatment cycles in the ixazomib and placebo groups, respectively, 16.0% and 10.1% of patients had completed all protocol-specified cycles, and 19.5% and 15.3% were ongoing; 70.7% and 78.3% of patients dose-escalated from the starting dose of 3 mg to 4 mg, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Treatment Exposure and Overall Safety Profile in the Safety Population

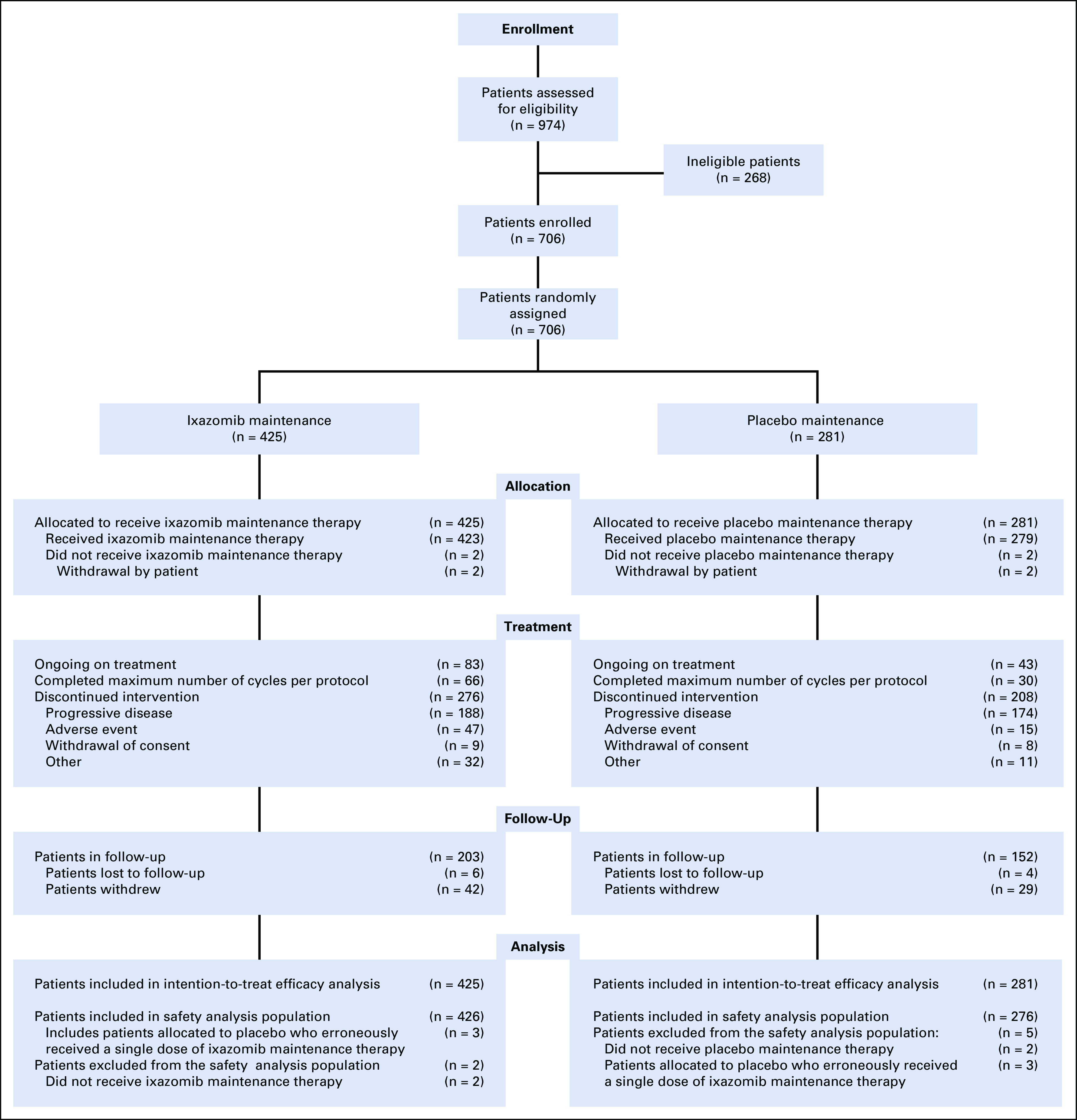

In the ixazomib versus placebo group, 36.6% versus 23.2% of patients had grade ≥ 3 treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs), 22.1% versus 16.7% had serious TEAEs, and 30.8% versus 5.1% had a dose reduction and 12.9% versus 8.0% discontinued because of TEAEs (Table 3). TEAEs for which the incidence was ≥ 5% higher with ixazomib versus placebo included nausea (26.8% v 8.0%), rash (25.6% v 10.5%), vomiting (24.2% v 4.3%), diarrhea (23.2% v 12.3%), peripheral neuropathy (19.5% v 10.9%), and pyrexia (11.3% v 5.1%; Table 4). Most TEAEs were grade 1 or 2 severity, with rates of grade ≥ 3 events being ≤ 3% for all individual TEAEs except pneumonia (3.8% grade 3; n = 16; ixazomib group). There was no evidence of cumulative toxicity over the course of treatment. Rates of cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, hypotension, liver impairment, and renal impairment were all low and similar between groups (Table 4). Nine patients (2.1%) in the ixazomib group had grade ≥ 3 events of renal impairment (considered unrelated to the study drug in six); three events resolved (two without drug interruption, one after dose delay), three resulted in discontinuation, and the one grade 5 event was considered unrelated to the study drug. Of these patients, three had preexisting kidney disease, including the patient who died. The overall rate of herpes zoster was 3.1% with ixazomib and 0.7% with placebo; in patients receiving antiviral prophylaxis, rates were 0.4% and 0%, respectively (Table 4). At a median follow-up of 2 years, there was no difference in the rate of new primary malignancies (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Common TEAEs in the Safety Population (≥ 10% in either group or rate difference of ≥ 5% between ixazomib and placebo groups) Plus Other TEAEs of Clinical Interest

Changes in mean Global Health Status/QoL score on the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core-30 are shown in the Data Supplement. Scores were similar between groups at study entry and were maintained in both groups during the protocol-defined treatment period.

Health care resource use (HRU) during treatment is summarized in the Data Supplement. Ixazomib did not result in additional HRU (hospitalizations, emergency room stays, and outpatient visits).

DISCUSSION

Ixazomib maintenance after standard-of-care induction treatment resulted in a statistically significant and clinically meaningful25 34.1% reduction in the risk of progression or death since the time of randomization compared with placebo, with an 8-month increase in median PFS. Additionally, a statistically significant benefit was demonstrated in patients who achieved CR or VGPR with initial therapy. Outcomes since randomization favoring ixazomib were seen in patients with ISS stage III disease and patients aged ≥ 75 years. In the prespecified subgroups of patients with no prior PI exposure and patients with prior immunomodulatory drug exposure, notable PFS benefits since randomization (based on HRs) were seen with ixazomib versus placebo. Although no PFS benefit was seen in the small subgroup of patients with conventional high-risk cytogenetics [t(4;14), t(14;16), del(17p)], ixazomib showed a PFS benefit in the larger subgroup with expanded high-risk cytogenetics, incorporating patients with amp1q21 in line with the current IMWG definition of high-risk cytogenetics.26 The benefits of ixazomib maintenance were realized in the context of a well-tolerated safety profile and no adverse impact on patients’ QoL or HRU, important considerations in this generally elderly, transplantation-ineligible population; similar and consistent findings have been reported from other phase III studies of ixazomib-based therapy in different treatment settings.21,27,28 TOURMALINE-MM4 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02312258) findings also support the significant PFS benefit seen with ixazomib versus placebo as post-transplantation maintenance therapy in the TOURMALINE-MM3 trial.20 Together, these studies demonstrate the utility and prolonged activity of oral, once-weekly ixazomib maintenance.

In the context of current therapy, the comparison versus placebo is a limitation of TOURMALINE-MM4; however, at the time of study design, there were no approved or standard-of-care maintenance therapies in nontransplantation NDMM and thus no clear comparator to use instead of placebo. Furthermore, current standard-of-care maintenance may vary among regions. Nevertheless, it is well established that lenalidomide provides a significant improvement in PFS after induction therapy in transplantation-ineligible patients. In the Myeloma XI trial,10 lenalidomide improved PFS since maintenance randomization versus observation.10 This study differs from TOURMALINE-MM4 in that patients received maintenance after thalidomide- (48%) or lenalidomide-containing (52%) induction10; that is, approximately half the patients received continuous lenalidomide through induction and maintenance. Lenalidomide maintenance after lenalidomide-based induction also demonstrated a PFS benefit, overall and since the start of maintenance, versus placebo or no maintenance in the MM-01512 and GIMEMA RV-MM-PI-20929 trials. In the FIRST trial of transplantation-ineligible patients with NDMM, continuous lenalidomide-dexamethasone since the start of therapy demonstrated improved PFS versus fixed-duration lenalidomide-dexamethasone, further highlighting the benefit of maintaining long-term lenalidomide therapy.15 However, no significant OS benefits were reported in these four studies.10,12,15,29 Similarly, bortezomib-based maintenance after bortezomib-based induction has contributed to notable overall outcomes in transplantation-ineligible patients in the GEM05MAS65,30 GIMEMA-MM-03-05,31 and UPFRONT studies32; however, the specific impact of bortezomib-based maintenance or PI-based maintenance more broadly has not been determined in a randomized, placebo-controlled phase III trial.

Patients in TOURMALINE-MM4 received induction therapy with a PI-containing and/or immunomodulatory drug–containing regimen at the discretion of their treating physicians. No patients received prior ixazomib, although 82.6% received PI-based induction, resulting in continuous PI-based therapy and a median total PFS of approximately 26 months. Evaluation of this overall median in the context of other data in transplantation-ineligible patients with NDMM is confounded by the immortal time bias arising from TOURMALINE-MM4 requiring patients to have achieved greater than or equal to PR at enrollment after 6-12 months of standard-of-care induction therapy. Comparisons among studies are also confounded by various patient- and disease-related factors, and should be avoided.

To our knowledge, TOURMALINE-MM4 is the first randomized phase III trial to specifically investigate an induction-agnostic maintenance approach—randomly assigning patients to ixazomib versus placebo regardless of the standard-of-care induction therapy received—in transplantation-ineligible NDMM. The feasibility of maintaining long-term PI-based therapy and convenience of oral administration with ixazomib are valuable attributes for treatment of the nontransplantation population, particularly for elderly patients, and this unique approach may be of value when considering tailoring treatment to specific patients. Given the disease heterogeneity of MM, physicians require options that enable them to amend and individualize first-line therapy. Prolongation of PFS with ixazomib regardless of the standard-of-care induction therapy is of potential value as an additional treatment option, along with continuous therapy approaches15,16 with lenalidomide12,29,33,34 or daratumumab8 after lenalidomide-based or daratumumab-based induction.

An alternative approach to long-term PI-based therapy is to use ixazomib in a continuous manner similar to that used with lenalidomide12,29,33,34 or daratumumab.8 A recent analysis of four phase II studies of ixazomib maintenance after ixazomib-based induction demonstrated the feasibility and activity of this approach.35 The phase III, placebo-controlled TOURMALINE-MM2 trial in transplantation-ineligible patients with NDMM compared ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone versus placebo-lenalidomide-dexamethasone for 18 cycles, followed by reduced-dose ixazomib-lenalidomide versus placebo-lenalidomide from cycle 19 onward. At the time of publication, a PFS benefit with ixazomib-based therapy, with a lengthy median, has been reported36 and the publication of the full study results is awaited. Transplantation-ineligible patients with NDMM are highly heterogeneous—one treatment approach does not fit all. An induction-agnostic maintenance or continuous therapy option may be of value for optimizing therapy in individual patients.

TOURMALINE-MM4 demonstrated the tolerability of ixazomib maintenance in this elderly population of transplantation-ineligible patients; 70.7% of patients tolerated the 3-mg dose of ixazomib sufficiently well to escalate to 4 mg. Overall rates of TEAEs were similar between groups, and TEAEs were mostly grade 1-2 severity. Rates of serious TEAEs and discontinuations because of TEAEs appeared slightly higher with ixazomib versus placebo, whereas rates of on-study death and new primary malignancies appeared similar. Common TEAEs that were more frequent with ixazomib included GI toxicities, rash, and peripheral neuropathy; however, rates of grade 3 events were low in both groups. No new safety signals were seen, reflecting the findings of TOURMALINE-MM3.20 In the Myeloma XI trial of lenalidomide as maintenance post-transplantation or postinduction, with a median duration of therapy of eighteen 28-day cycles, 28% of patients who had discontinued lenalidomide did so because of AEs.10 Furthermore, lenalidomide appeared to be associated with higher rates of dose modifications (69%) and serious AEs (45%)10 than seen in TOURMALINE-MM4 (dose reductions, 30.8%; serious TEAEs, 22.1%) or TOURMALINE-MM3 (19% and 27%, respectively),20 and an elevated risk of new primary malignancies.10 The tolerable safety profile of ixazomib maintenance in TOURMALINE-MM4 was reflected in similar HRU data between arms and in patient-reported QoL, which was maintained since study entry in both arms and was generally similar throughout the treatment period, indicating that active treatment with ixazomib did not have a negative impact on patient-reported QoL versus placebo in this double-blind trial.

In TOURMALINE-MM4, treatment duration was fixed at 2 years, based on the duration of bortezomib-based maintenance in prior phase III trials.31,37 At the time of trial design, PI-based treat-to-progression approaches had not been studied in a phase III trial, and, to date, the optimal duration of PI-based maintenance remains to be determined. Longer-term therapy may have resulted in improved outcomes in some patients in TOURMALINE-MM4; however, because median PFS was less than 24 months, the median would be unlikely to be affected. With the favorable tolerability of ixazomib, it was felt that this treatment duration could be achieved with minimal discontinuations because of toxicity and a reduced risk of developing resistant disease. Nevertheless, because median treatment duration was 13 cycles and 16.0% of patients completed protocol-specified therapy, treat-to-progression therapy is unlikely to have resulted in prolonged treatment except in a few patients.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, ixazomib is the first induction-agnostic maintenance option investigated for transplantation-ineligible patients with NDMM. These results indicate that ixazomib is well tolerated and provides a PFS benefit in this setting, thereby representing a valuable treatment option for patients. Subgroup analyses suggest PFS benefit across this population, including in elderly patients, those with preinduction ISS stage III disease, and patients achieving CR or VGPR postinduction. Furthermore, ixazomib may provide a valuable maintenance option in combination with other agents, such as immunomodulatory drugs and monoclonal antibodies. TOURMALINE-MM4 continues in a double-blind fashion for long-term evaluation of PFS2 and OS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. The trial was designed by the authors in collaboration with the sponsor. Data were gathered by the investigators and sponsor, and analyzed by the sponsor. The sponsor funded professional medical writing support to prepare the manuscript. We thank the patients and their families, as well as the physicians, nurses, study coordinators, and research staff for participation in the trial; Dasha Cherepanov, PhD, and Lauren Cain, PhD, of Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, for their contributions to health-related quality of life and health care resource use analyses and interpretations; Renda Ferrari, PhD, of Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for editorial assistance; and Steve Hill, PhD, of FireKite, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare, for professional medical writing assistance, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Poster presented at the ASCO20 Virtual Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, May 29-31, 2020; paper presented at the virtual 25th Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association, The Hague, Netherlands, June 11-21, 2020.

SUPPORT

Sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

CLINICAL TRIAL INFORMATION

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Meletios A. Dimopoulos, Wee-Joo Chng, Xavier Leleu, Gareth Morgan, Richard Labotka, Antonio Palumbo, Sagar Lonial

Provision of study materials or patients: Meletios A. Dimopoulos, Albert Oriol, Mamta Garg, Meral Beksac, Sara Bringhen, Wee-Joo Chng, Xavier Leleu, María-Victoria Mateos, Sagar Lonial

Collection and assembly of data: Meletios A. Dimopoulos, Ivan Špička, Hang Quach, Albert Oriol, Roman Hájek, Mamta Garg, Meral Beksac, Sara Bringhen, Eirini Katodritou, Wee-Joo Chng, Xavier Leleu, Shinsuke Iida, María-Victoria Mateos, Alexander Vorog

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Ixazomib as Postinduction Maintenance for Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Not Undergoing Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation: The Phase III TOURMALINE-MM4 Trial

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Meletios A. Dimopoulos

Honoraria: Amgen, Celgene, Takeda, Janssen-Cilag, Bristol Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, Takeda, Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb

Ivan Špička

Honoraria: Celgene, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, Takeda, Novartis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, Takeda, Novartis, Sanofi

Speakers' Bureau: Celgene, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, Takeda, BMS, Novartis, Sanofi

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene, Amgen, Janssen-Cilag, BMS

Hang Quach

Consulting or Advisory Role: GlaxoSmithKline, Celgene, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Janssen-Cilag, CSL Behring, Amgen, Sanofi

Research Funding: Celgene, Amgen, Karopharm, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi

Albert Oriol

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Janssen, Amgen, Sanofi, GSK

Speakers' Bureau: Amgen, Celgene

Roman Hájek

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, Amgen, Celgene, AbbVie, BMS, PharmaMar, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda, Amgen

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), BMS (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Takeda (Inst)

Mamta Garg

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Takeda

Meral Beksac

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene (Inst), Janssen-Cilag (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Sanofi Pasteur (Inst), Oncopeptides

Speakers' Bureau: Amgen (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Janssen-Cilag (Inst), Sanofi Pasteur (Inst)

Sara Bringhen

Honoraria: Celgene, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen-Cilag

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Janssen-Cilag, Takeda, Karyopharm, Amgen

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen, Celgene, Janssen-Cilag

Eirini Katodritou

Honoraria: Takeda, Janseen-Cilag, Amgen, Genesis-Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Janseen-Cilag

Research Funding: Takeda, Amgen, Janseen-Cilag, Genesis-Pharma

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genesis-Pharma, Takeda

Wee-Joo Chng

Honoraria: Johnson and Johnson, Amgen, Celgene, Takeda, AbbVie

Research Funding: Janssen (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Amgen (Inst)

Xavier Leleu

Honoraria: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Amgen, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda, Sanofi, AbbVie, Merck, Roche, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Carsgen Therapeutics, Oncopeptides, GSK

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Amgen, Takeda, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, Roche, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Oncopeptides, Carsgen Therapeutics, GSK

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Takeda

Shinsuke Iida

Honoraria: Takeda, Celgene, Janssen, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono Pharmaceutical, Sanofi, Ono Pharmaceutical, Takeda, Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie

Research Funding: Takeda (Inst), Chugai Pharma (Inst), Kyowa Hakko Kirin (Inst), Ono Pharmaceutical (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb Japan (Inst), Janssen (Inst), AbbVie (Inst)

Maria-Victoria Mateos

Honoraria: Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Amgen, Takeda, GSK, AbbVie/Genentech, Adaptive

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, Janssen-Cilag, Celgene, Amgen, AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Pharmamar-Zeltia

Gareth Morgan

Honoraria: BMS, Janssen, Genentech, Sanofi, Karyopharm, Takeda

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, GSK

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: BMS, Janssen

Alexander Vorog

Employment: Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited

Richard Labotka

Employment: Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited

Bingxia Wang

Employment: Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited

Antonio Palumbo

Employment: Takeda, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Takeda

Honoraria: Takeda

Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda

Research Funding: Takeda (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Takeda

Sagar Lonial

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: TG Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, AbbVie, Takeda, Merck, Juno Therapeutics

Speakers' Bureau: Sanofi

Research Funding: Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda

Other Relationship: TG Therapeutics

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palumbo A Gay F Cavallo F, et al. : Continuous therapy versus fixed duration of therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 33:3459-3466, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludwig H, Zojer N: Fixed duration vs continuous therapy in multiple myeloma. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2017:212-222, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gay F Jackson G Rosiñol L, et al. : Maintenance treatment and survival in patients with myeloma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 4:1389-1397, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yong K Delforge M Driessen C, et al. : Multiple myeloma: Patient outcomes in real-world practice. Br J Haematol 175:252-264, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terpos E, Suzan F, Goldschmidt H: Going the distance: Are we losing patients along the multiple myeloma treatment pathway? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 126:19-23, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chng WJ, Beksac M, Hajek R, et al: Addressing unmet medical needs in maintenance treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM). Hemasphere 2:1001, 2018 (abstr S1)

- 7.Kumar SK Callander NS Hillengass J, et al. : NCCN guidelines insights: Multiple myeloma, Version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17:1154-1165, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mateos MV Cavo M Blade J, et al. : Overall survival with daratumumab, bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ALCYONE): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 395:132-141, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durie BGM Hoering A Abidi MH, et al. : Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389:519-527, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson GH Davies FE Pawlyn C, et al. : Lenalidomide maintenance versus observation for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (Myeloma XI): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20:57-73, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy PL Holstein SA Petrucci MT, et al. : Lenalidomide maintenance after autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 35:3279-3289, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palumbo A Hajek R Delforge M, et al. : Continuous lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 366:1759-1769, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulte ED Dmytrijuk A Nie L, et al. : FDA approval summary: Lenalidomide as maintenance therapy after autologous stem cell transplant in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Oncologist 23:734-739, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benboubker L Dimopoulos MA Dispenzieri A, et al. : Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med 371:906-917, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facon T Dimopoulos MA Dispenzieri A, et al. : Final analysis of survival outcomes in the phase 3 FIRST trial of up-front treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood 131:301-310, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Facon T Kumar S Plesner T, et al. : Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. N Engl J Med 380:2104-2115, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson PG San Miguel JF Moreau P, et al. : Interpreting clinical trial data in multiple myeloma: Translating findings to the real-world setting. Blood Cancer J 8:109, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldschmidt H Ashcroft J Szabo Z, et al. : Navigating the treatment landscape in multiple myeloma: Which combinations to use and when? Ann Hematol 98:1-18, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.: Highlights of prescribing information. https://www.ninlaro.com/prescribing-information.pdf.

- 20.Dimopoulos MA Gay F Schjesvold F, et al. : Oral ixazomib maintenance following autologous stem cell transplantation (TOURMALINE-MM3): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 393:253-264, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schjesvold F, Goldschmidt H, Maisnar V, et al: Quality of life is maintained with ixazomib maintenance in post-transplant newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: The TOURMALINE-MM3 trial. Eur J Haematol 104:443-458, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Rajkumar SV Dimopoulos MA Palumbo A, et al. : International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 15:e538-e548, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajkumar SV Harousseau JL Durie B, et al. : Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: Report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood 117:4691-4695, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR: A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics 35:549-556, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar H, Fojo T, Mailankody S: An appraisal of clinically meaningful outcomes guidelines for oncology clinical trials. JAMA Oncol 2:1238-1240, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonneveld P Avet-Loiseau H Lonial S, et al. : Treatment of multiple myeloma with high-risk cytogenetics: A consensus of the International Myeloma Working Group. Blood 127:2955-2962, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hari P Lin HM Zhu Y, et al. : Healthcare resource utilization with ixazomib or placebo plus lenalidomide-dexamethasone in the randomized, double-blind, phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM1 study in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Med Econ 21:793-798, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leleu X Masszi T Bahlis NJ, et al. : Patient-reported health-related quality of life from the phase III TOURMALINE-MM1 study of ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone versus placebo-lenalidomide-dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol 93:985-993, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palumbo A Cavallo F Gay F, et al. : Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 371:895-905, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mateos MV Oriol A Martínez-López J, et al. : GEM2005 trial update comparing VMP/VTP as induction in elderly multiple myeloma patients: Do we still need alkylators? Blood 124:1887-1893, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palumbo A Bringhen S Rossi D, et al. : Bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide followed by maintenance with bortezomib-thalidomide compared with bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 28:5101-5109, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niesvizky R Flinn IW Rifkin R, et al. : Community-based phase IIIB trial of three UPFRONT bortezomib-based myeloma regimens. J Clin Oncol 33:3921-3929, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.226407. Bringhen S, D’Agostino M, Paris L, et al: Lenalidomide-based induction and maintenance in elderly newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients: Updated results of the EMN01 randomized trial. Haematologica 105:1937-1947, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larocca A Salvini M Gaidano G, et al. : Sparing steroids in elderly intermediate-fit newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with a dose/schedule-adjusted Rd-R vs. continuous Rd: Results of RV-MM-PI-0752 phase III randomized study. HemaSphere 3:244-245, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dimopoulos MA Laubach JP Echeveste Gutierrez MA, et al. : Ixazomib maintenance therapy in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: An integrated analysis of four phase I/II studies. Eur J Haematol 102:494-503, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Facon T Venner CP Bahlis NJ, et al. : Ixazomib plus lenalidomide-dexamethasone (IRd) vs. placebo-Rd for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients not eligible for autologous stem cell transplant: The double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM2 Trial. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 20(Suppl.1):S307-S308, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonneveld P Schmidt-Wolf IG van der Holt B, et al. : Bortezomib induction and maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: Results of the randomized phase III HOVON-65/ GMMG-HD4 trial. J Clin Oncol 30:2946-2955, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]