Abstract

Chronic and excessive alcohol abuse cause direct and indirect detrimental effects on a wide range of body organs and systems and accounts for ~4% of deaths worldwide. Many factors influence the harmful effects of alcohol. This concise review presents newer insights into the role of select second hits in influencing the progression of alcohol-induced organ damage by synergistically acting to generate a more dramatic downstream biological defect. This review specifically addresses on how a lifestyle factor of high fat intake exacerbates alcoholic liver injury and its progression. This review also provides the mechanistic insights into how increasing matrix stiffness during liver injury promotes alcohol-induced fibrogenesis. It also discusses how hepatotropic viral (HCV, HBV) infections as well as HIV (which is traditionally not known to be hepatotropic), are potentiated by alcohol exposure to promote hepatotoxicity and fibrosis progression. Finally, this review highlights the impact of reactive aldehydes generated during alcohol and cigarette smoke coexposure impair innate antimicrobial defense and increased susceptibility to infections. This review was inspired by the symposium held at the 17th Congress of the European Society for Biomedical research on Alcoholism in Lille, France entitled ‘Second hits in alcohol-related organ damage’.

Short Summary: This review delineates the role and mechanism of action of selected risk factors in exacerbating alcohol-induced organ injury and will benefit researcher currently investigating alcohol’s role in organ pathology.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol consumption is an important social, economic and health problem (Axley et al., 2019). Heavy alcohol consumption causes direct and indirect detrimental effects on a wide range of body organs and systems, including liver, brain, lungs, pancreas, and accounts for ~4% of deaths worldwide (Global status report on alcohol and health 2018). There are many factors, both genetic and nongenetic, which by influencing the harmful effects of alcohol not only drives the progression of alcohol-related organ injury to end-stage diseases, but also worsens the treatment outcomes. Since the ‘second hits’ often exacerbate alcohol’s effect, efforts have been undertaken to understand the molecular mechanism(s) that affect the progression of alcohol-induced organ pathology. The role of genetic polymorphisms as well as the nongenetic factors, such as the pattern of drinking, gender, the kind of beverage, nutrition, microbiome in exacerbating alcohol’s effect were reviewed in our earlier publications (Kharbanda et al., 2018; Kirpich et al., 2020; Neuman et al., 2017; Osna et al., 2017) and will not be discussed here.

The goal of the review is to offer newer insights based on recent data into the role of select second hits in alcohol-induced organ dysfunction. Understanding of the nuances could help identify new druggable targets such that promising therapeutic agents to prevent, manage or reverse the disease pathogenesis could be developed. This narrative was inspired by the symposium held at the 17th Congress of the European Society for Biomedical research on Alcoholism in Lille, France entitled ‘Second hits in alcohol-related organ damage’ and is not a PRISMA-based systematic review. Here, we will overview the role of, high fat intake (a life-style factor), increased liver matrix stiffness, viral infections and the impact of reactive aldehydes generated by cigarette smoke coexposure in the development of alcohol-induced organ injury. Although high-fat diet and infections (alcohol-reduced innate immunity) are well-known insults known to promote organ damage by alcohol, the emphasis on the ethanol-potentiating properties of liver stiffness (LS) as a possible second hit is novel. It appeared that not only increased liver inflammation enhances LS (Raizner et al., 2017), but also a certain level of fibrosis in itself promotes progressive liver injury driven by the initial trigger. The experimental evidence for that was recently demonstrated in HCV–HIV coinfected liver cells where double-infected hepatocytes, plated on gels mimicking an increased stiffness (25 kPa), exhibit higher infection levels and increased susceptibility to apoptosis (Ganesan et al., 2018a; Ganesan et al., 2019c).

The take-home messages of this review are (a) a high-fat diet (HFD) exacerbates alcohol-induced liver injury than either agent alone and vice versa; (b) Increased liver matrix stiffness contributes in development of alcohol-induced organ injury; (c) Viral infections potentiate alcohol-induced liver injury and vice versa. (d) Stable hybrid aldehyde-protein adducts which are generation in lung coexposure to both cigarette smoke and alcohol exhibit multifaceted suppression of lung innate defense.

Alcohol and fat: a double whammy for liver injury and cancer

Steatosis and steatohepatitis are common to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcohol-related liver disease (ALD). Obesity and other metabolic risks, i.e. diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia can coexist, and influence disease severity, progression and outcomes in both NAFLD and ALD (Chiang and McCullough, 2014; Sim, 2015; Xia et al., 2019). The role of this ‘non-significant’ alcohol in the development of fatty liver disease remains controversial, more so because the mere name NAFLD excludes coexistence and contribution of alcohol in liver disease pathology. We believe that the recent consensus (Eslam et al., 2020) of replacing NAFLD with ‘metabolic associated fatty liver disease’ (MAFLD) is apt in this context, allowing consideration of coexisting ALD and MAFLD.

It is known that drinkers who are obese are more likely to develop cirrhosis than those within a healthy weight range (Hart et al., 2010). It is suggested that the effect of alcohol is similar to that of sugar (such as fructose in processed foods) resulting in metabolic dysfunction (Sim, 2015). The metabolic effect of excessive drinking depends on the source of energy, not simply on the total energy consumed. In some animal models, moderate alcohol increased MAFLD progression (Byun et al., 2013) and an increased inflammation and hepatitis development was also seen in a mouse model of HFD given an acute binge alcohol (Chang et al., 2015). However, there is a lower risk for MAFLD development in both humans and animal models consuming low to moderate alcohol levels (Dunn et al., 2012; Moriya et al., 2015). This indicates that the two etiologies influence the progression of liver injury, however, the direction of this interaction seems unresolved and mechanisms underlying this interaction remain unclear.

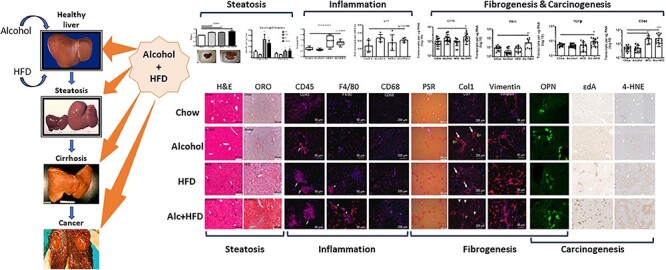

Animal models of liver injury by alcohol alone or diet alone have proven difficult to induce human equivalent of a severe liver disease. In both etiologies, a second hit (for example lipopolysaccharide for alcohol/diabetes for HFD), is required to progress the disease to an advanced stage (Bertola et al., 2013; Lo et al., 2011). Thus, investigators employed a mouse model that combined a regimen of fat rich food feeding with binge drinking for examining the interaction between alcohol and high-caloric intake. In this model, C57BL6 mice on a HFD (45% kcal fat ad lib) were given intermittent binge alcohol (2 g/kg body weight, twice per week for 12 weeks) which generated an amplified liver pathology compared to either alcohol or HFD alone (Duly et al., 2015). The Alcohol+HFD-fed mice exhibited increased body weight, liver weight, cholesterol, hepatic steatosis, micro- and macro-vesicular lipid droplets, dysregulated lipogenesis (SREBP-1, SCD-1, ACOX1 and PPARα), inflammation (CD45+/CD68+/F4/80+ cells) and fibrogenesis (activated hepatic stellate cells (HSC), Col1 expression) as shown (Fig. 1). Further, Alcohol+HFD-fed mice showed significantly higher insulin in the blood (P = 0.0017), greater glucose sensitivity (P = 0.064) and upregulated expression of several markers of fibrosis, including TGFβ (P = 0.003; P = 0.0004; P = 0.0001) and PAI-1 (P = 0.05; P = 0.007; P = 0.05) compared with alcohol or HFD alone.

Fig. 1.

Alcohol in combination with high-fat diet (HFD) exacerbates liver injury than either treatment alone. C57Bl6/J mice were fed a HFD (45% kcal fat ad lib) with intermittent binge alcohol (2 g/kg body weight, twice per week for 12 weeks. Superimposing alcohol in this HFD mouse model of liver injury shows increased steatosis (liver weight, lipid deposit, triglyceride and cholesterol), inflammation (serum insulin, insulin resistance, CD45+, F4/80+ and CD68+ inflammatory infiltrate), fibrogenesis (PSR staining, Col1, Vimentin+ activated stellate cells, osteopontin (OPN), PAI-1 and TGFβ) and markers of carcinogenesis (etheno DNA adducts (ɛDA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), OPN and CD44). Modified image from Duly et al. (2015).

Alcohol metabolism generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) which are an important factor in the pathogenesis of ALD and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). ROS is induced by inflammatory processes, such as in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (Peccerella et al., 2018), but also by the induction of cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), as seen with chronic alcohol consumption. ROS can react with polyunsaturated fatty acids resulting in the production of reactive aldehydes, such as 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE). HNE can react with DNA to form mutagenic exocyclic etheno-DNA adducts (εDA) involved in cancer (Peccerella et al., 2018). Nonetheless, there is little information on whether coexistence of MAFLD and ALD enhances the risk of liver cancer.

The immunohistochemical expression of ROS markers (Cyp2E1, HNE) and εDA examined in the livers of mice revealed no noticeable changes in hepatic Cyp2E1 expression across the treatments. However, the expression of HNE in Alcohol+HFD was driven mainly through alcohol as HFD alone treatment group showed similar staining as chow (Fig. 1). Whereas alcohol alone moderately and HFD alone to a greater extent increased εDA, Alcohol+HFD-fed mice showed a striking elevation in clusters of εDA within the liver (Fig. 1), indicating that a combination of alcohol and HFD could result in more severe pathology.

Another pathway of interest is osteopontin (OPN), a Th1 cytokine, which by recruiting neutrophils and monocytes modulates inflammation/fibrogenesis and promotes liver disease progression (Ramaiah and Rittling, 2008). Circulating and tissue expression of OPN positively correlate with disease severity in ALD patients (Seth et al., 2006). Further studies using an acute alcohol mouse model of steatosis revealed that the mechanism of OPN action is via stellate cell activation (Seth et al., 2014). OPN is also upregulated in MAFLD (Sahai et al., 2004; Syn et al., 2010) and HCC (Kim et al., 2006; Phillips et al., 2012), and is a known marker for metastasis in cancer, including HCC (Shang et al., 2011; Takafuji et al., 2007).

A significant increase was observed in hepatic OPN in the Alcohol+HFD-fed mice compared to chow (P = 0.013) or HFD (P = 0.002), which was mainly driven by alcohol (P = 0.589, Alcohol vs Alcohol+HFD, Fig. 1). It is likely that the increased OPN cytokine in the current model is recruiting neutrophils and retaining Kupffer cells in the liver, thereby contributing to progressive liver damage (Fig. 1). OPN increases HCC growth through interaction with its cell surface binding partner CD44 (Phillips et al., 2012). Interestingly, a significant overexpression of CD44 accompanied OPN increase in Alcohol+HFD-fed mice compared to chow or alcohol (P = 0.0001 for both) that was mainly driven through HFD (P = 0.999, HFD vs Alcohol+HFD, Fig. 1). It is likely that the interaction between coexisting ALD and MAFLD increasing disease severity may also confer increased risk for HCC development via the activated OPN-CD44 pathway. Further studies are required to understand the mechanisms.

To summarize, the animal model of chronic binge with moderate alcohol combined induced human equivalent of a severe liver disease including several indicators of carcinogenesis-related molecules, which activate within a 12-week period of treatment.

Matrix stiffness regulates fibrosis progression in alcohol-induced liver injury

Significant challenges remain for developing preventive or curative approaches targeting ALD (Bataller et al., 2003; Gao and Bataller, 2011; Siegmund and Brenner, 2005). Recently, LS has been investigated in clinical settings as a great read out for determining recovery, survival and disease staging of ALD patients’ (Moreno et al., 2019; Mueller et al., 2010). One of the reason for the increase in LS in ALD patients has been attributed to progressive fibrosis and cirrhosis development (Friedman, 2015; Hernandez-Gea and Friedman, 2011b; Lee et al., 2015; Trautwein et al., 2015). Liver fibrosis is a sustained wound healing response in the organ resultant of chronic stressors such as viral infections, autoimmune disorders, metabolic disorders or alcohol abuse (Bataller and Brenner, 2005). During liver fibrosis, stellate cells and other hepatic cell types acquire a profibrogenic phenotype that primarily results in (i) excessive production of extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules forming scar tissue; (ii) increased inflammatory response and (iii) loss of parenchymal function (Friedman, 2003). The reversibility of liver fibrosis depends on the nature and severity of the stressor and, irreversible fibrosis can result in fatal conditions such as cirrhosis, kidney failure and HCC (Hernandez-Gea and Friedman, 2011a). The pathological consequences of altered tissue mechanics in liver fibrosis during ALD development are well established with huge emphasis given to the role that matrix rigidity plays on stellate cells activation and matrix deposition (Caliari et al., 2016; Li et al., 2007; Olsen et al., 2011; Wells, 2013, 2016). Although acknowledging these seminal works, understanding the role of matrix rigidity in combination with alcohol exposure on hepatocytes remains a highly significant and unexplored area of research.

The incidence and prevalence of LS increase drastically with fibrosis progression due to ALD; however, despite this strong association, molecular mechanisms that account for the stiffness predilection to hepatocytes dysfunction during fibrosis have been underexplored. Experimental liver fibrosis in rodents (rats and mice) induced by surgical intervention (e.g. bile duct ligation), genetic manipulation of fibrosis-related genes (e.g. Mdr2 knockout mice) or application of hepatotoxins such as carbon tetrachloride or thioacetamide. However, in all of these animal models, the toxins or genetic manipulation adds another layer of biological stimulation that might potentially drive changes in liver physiology when coexposed with alcohol. This makes it challenging to isolate the role of stiffness as a sole parameter that impact alcohol driven organ damage using any of the fibrosis animal models. Factors contributing to the lack of progress are: (i) unable to use animal models to understand the mechanism; (ii) challenges in developing mechanically tunable scaffolds; (iii) culture and maintenance of primary hepatocytes on synthetic protein-free scaffolds; and (4) paucity of studies investigating the mechanisms linking biomechanical signaling in liver during fibrosis progression in ALD. To study the interaction between alcohol and stiffness on liver injury in modulating primary hepatocytes and stellate cell function, an innovative biomimetic liver fibrosis model that allows modulation of substrate stiffness (2 kPa, 9 kPa 25 kPa and 55 kPa mimicking healthy, early fibrotic, fibrotic and extremely fibrotic substrates (Natarajan et al., 2015) was employed.

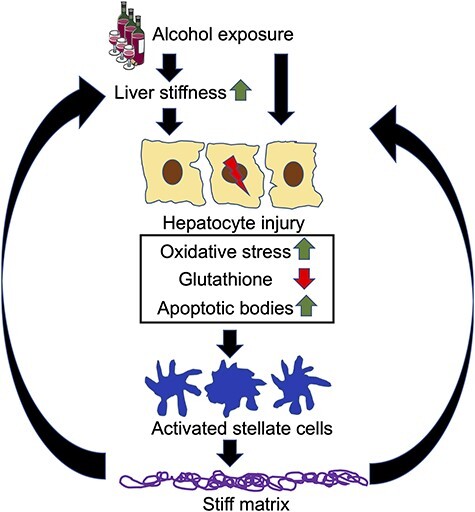

The hepatocytes cultured on soft substrates (2 kPa) displayed a more differentiated and functional phenotype for a longer duration as compared to stiff substrates (55 kPa) (Natarajan et al., 2015). Hepatocytes on soft substrates also exhibited higher urea and albumin synthesis. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) activity, another critical marker of hepatocytes, displayed a strong dependence on substrate stiffness, wherein hepatocytes on soft substrates retained 2.7-folds higher CYP activity on Day 7 in culture, as compared to collagen-coated tissue culture dishes. The increase in stiffness downregulated key drug transporter genes (NTCP, UGT1A1 and GSTM-2). Further, the epithelial cell phenotype was better maintained on soft substrates as indicated by higher expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α, cytokeratin18 and connexin 32. Additionally, hepatocytes cultured on NAFLD-like stiffness (i) upregulated lipogenic genes and lowered oxidation genes expression, mitochondrial respiration, and glycolytic capacity, (ii) increased ROS production and (iii) disrupted mitochondrial fusion process and dynamics. Furthermore, significant increase in oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and reduced glutathione (GSH) in hepatocytes cultured on ALD-like stiffness compared to healthy liver stiffness was observed (Moeller et al., 2019) as depicted (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Model diagram of the acceleration of fibrosis progression during alcohol exposure due to increase in liver matrix stiffness. Alcohol exposure induces prominent oxidative stress, and apoptosis in hepatocytes. These apoptotic bodies engulfed by HSC induce profibrotic activation. Increased matrix stiffness corresponding to more advanced stages of liver disease further promotes apoptosis of injured hepatocytes, thereby accelerating fibrosis development.

In vitro experiments were further designed using the conditioned medium (CM) of primary hepatocytes (isolated from alcohol-fed rats) cultured on stiffness mimicking healthy and fibrotic environment which was added to human HSC cultures (Thulasingam et al., 2019). Cells treated with CM from stiffer matrix resulted in a significant increase in HSC proliferation, and expression of fibrosis-related genes (COL1A; TGF-β; PDGFR). A previous study reported that increased matrix stiffness enhances apoptosis in HCV–HIV-coinfected hepatocytes and that apoptotic bodies (AB) derived from these infected hepatocytes activate HSC to drive fibrosis progression (Ganesan et al., 2018a). These considerations suggest that LS regulates hepatocytes function and contribute to stellate cells activation and progression of liver fibrosis during ALD and acts as a ‘second hit’ on liver exacerbating ALD.

Together, all these data demonstrate the plausible role of stiffness in regulating hepatocytes function and contributing to stellate cells activation and progression of liver fibrosis during alcohol liver disease.

Alcohol exacerbates pathogenesis of viral hepatitis

Here, we overview the role of ethanol in exacerbation of HCV, HBV and HIV-infection-induced liver injury. The prevalence of alcohol abuse is high in patients infected with hepatotropic viruses. In fact, the incidence of HCV-infection is 7–10-fold higher in patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD), and the most prominent changes were reported in heavy alcohol drinkers leading to development of advanced liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and HCC (Baumert et al., 2017; Bruden et al., 2017; Vandenbulcke et al., 2016). The link between HBV and alcohol consumption is less established; however, alcohol abuse increases risk of end-stage liver disease development in chronically HBV-infected patients (El-Serag, 2011; Sayiner et al., 2019). In addition, HIV was recently reported to induce liver injury in the absence of the hepatotoxic effects of modern antiretroviral therapy, and the development of liver fibrosis and HCC is also more frequent in alcohol abusers (Debes et al., 2016; Pandrea et al., 2010; Pascual-Pareja et al., 2009).

Both alcohol and chronic viral infections can serve as second hits depending on which condition takes place first. Viral infection may drive the progression of alcohol hepatitis to end-stage diseases in patients with AUD infected with any hepatotropic virus. It also might be the case when chronically infected patients become alcohol abusers. Regardless of which agent (virus or alcohol) is a primary cause of liver injury, the combination of two insults provides either synergistic or additive effects and exacerbates liver disease pathogenesis. Alcohol exacerbates pathogenesis of chronic infections in the liver by multiple ways. First, alcohol increases replication of hepatotropic viruses. This observation, related to both HCV (Ran et al., 2018; Seronello et al., 2010; Szabo et al., 2015) and HBV (Ganesan et al., 2019a; Larkin et al., 2001), was confirmed by using in vitro and in vivo animal models. In contrast, even though alcohol increases the levels of HIV RNA in hepatocytes, this is not because of alcohol-triggered HIV replication in liver parenchymal cells but likely occurs due to alcohol-induced accumulation of viral RNAs/proteins in hepatocytes (Ganesan et al., 2019b).

The pathological events induced by all three viruses (HCV, HBV and HIV) are based on their lipogenic properties, which leads to the development of fatty liver in monoinfections and coinfections (Ganesan et al., 2018c; Li et al., 2019; Rowe, 2017; Stroffolini et al., 2020). In addition to virus-initiated fat deposition, antigens of HCV, HBV and HIV, induce oxidative stress. In fact, both structural and nonstructural HCV proteins (core and NS5A) generate ROS, deplete glutathione levels and increase CYP2E1 expression in hepatocytes (Otani et al., 2005; Singal and Anand, 2007), causing an upregulation of HNE-adducted proteins in hepatocytes (Ganesan et al., 2015a). An increase of CYP2E1-induced oxidative stress by alcohol accompanied by adduction of proteins with HNE and malondialdehyde in HBV-infection has also been reported (Ganesan et al., 2019a; Ganesan et al., 2020; Min et al., 2013). Furthermore, HIV and ethanol metabolism also induce oxidative stress and HNE proteins adduct formation in hepatocytes (Ganesan et al., 2019b). Lipid accumulation and oxidative stress promote virus-triggered NASH progression to end-stage liver disease potentiated by alcohol exposure (Asfari et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2020; McCabe et al., 2019; Morrison et al., 2019; Singal et al., 2020). As a downstream from oxidative stress event, there is impairment in the activity of the proteasome, which is a major catabolic pathway for cellular protein degradation. This leads to suppressed degradation of viral proteins, dysregulation in the presentation on the surface of hepatocytes of MHC class I-viral peptide complex (and hence escape immune recognition by cytotoxic T-cells) and further enhancement in the oxidative and ER stresses (Ganesan et al., 2019a; Ganesan et al., 2019b; Osna, 2009; Osna et al., 2014; Osna et al., 2008).

Alcohol-induced increase in viral replication, expression of viral proteins in infected hepatocytes and subsequent oxidative stress generation occurs because ethanol metabolism suppresses innate immunity in hepatocytes, thereby making these cells more susceptible to the effects of viruses. In fact, the combination of HCV and ethanol suppresses interferon alpha (IFNα)-induced activation of antiviral IFN-stimulated genes via the JAK-STAT1 pathway (Ganesan et al., 2019a; Ganesan et al., 2019b; Osna et al., 2015). This occurs either due to HCV and ethanol metabolism-triggered induction of negative regulators of IFN signaling or because of impaired methylation of STAT1, which prevents protective gene activation (Ganesan et al., 2016b; Ganesan et al., 2018d; Ganesan et al., 2015b). In addition to innate immunity, alcohol may also affect the adaptive immunity to interfere with elimination of infected cells by immune system (Ganesan et al., 2020; Szabo et al., 2010).

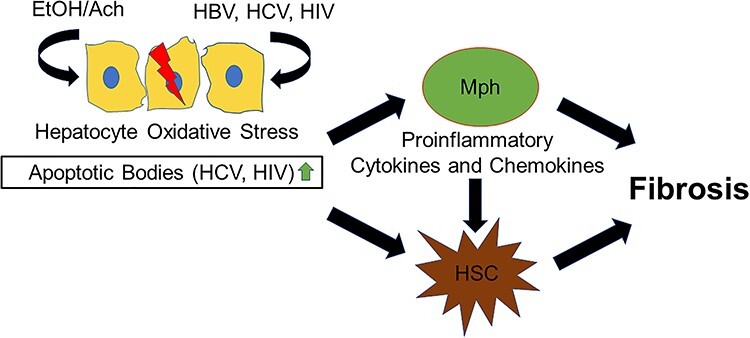

The major consequence of ethanol-hepatotropic virus induced oxidative stress is massive cell death (mainly, apoptotic) which promotes fibrosis progression. Although HBV slows down apoptosis, (Lin and Zhang, 2017), HCV and HIV induce apoptosis of infected hepatocytes of HCV and HIV-infected liver cells, and this effect becomes even more potent in coinfection (Ganesan et al., 2018a; Ganesan et al., 2019b; Ganesan et al., 2019c). Although it would appear that the rapid clearance of infected hepatocytes would be beneficial; it is not so because the engulfment of the viral particles-expressing apoptotic hepatocytes by liver macrophages and HSC causes inflammation and fibrosis development (Ganesan et al., 2016a; Ganesan et al., 2019b; Ganesan et al., 2018b).

In conclusion, alcohol increases hepatotoxicity initially triggered by HCV, HBV and HIV as shown in Fig. 3. Ethanol metabolites speed up viral replication and synergizing with virus, promote oxidative stress, which may cause detrimental consequences either by inducing hepatocytes activation/proliferation (as in the case of HBV) or apoptotic cell death (as seen by HCV and HIV infections). Subsequent activation of liver nonparenchymal cells by stress signals and engulfment of apoptotic hepatocytes promote fibrosis/inflammation development and progression to end-stage liver disease.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of how ethanol metabolism potentiates viral-induced liver injury. Viruses (HCV, HIV and HBV) combined with ethanol metabolism induce massive oxidative stress development. In HCV and HIV infections, this results in apoptotic death in hepatocyte. The engulfment of apoptotic hepatocytes by macrophages (Mph) and hepatic stellate cells (HSC) activates profibrotic/proinflammatory changes in these cells. HBV potentiated by ethanol metabolism promotes oxidative stress in hepatocytes. Although no apoptosis hepatocyte apoptosis occurs, enhanced fibrosis is observed via a yet nonidentified mechanism(s).

Reactive aldehydes from alcohol and cigarette smoke coexposure impair lung innate antimicrobial defense

The lung is a target for alcohol-induced tissue injury (Yeligar and Wyatt, 2019), yet few studies exist regarding coexposures of alcohol and other environmental agents. Smoking represents the most important ‘second hit’ exposure, as most individuals with an AUD also smoke cigarettes (Romberger and Grant, 2004). Alcohol misuse and cigarette smoking are comorbidities resulting in significant susceptibility to lung infections. Several innate lung defense mechanisms are altered by this combination (Yeligar et al., 2016). Functional targets of alcohol in the lung include alterations in alveolar epithelial barriers, macrophage-mediated cellular immunity, and decreases in mucociliary clearance. Mucociliary clearance is negatively impacted, in particular, by smoke and alcohol through cilia slowing and ciliated cell detachment caused by the coexposure-induced activation of protein kinase C epsilon (Wyatt et al., 2012). Lung pathologies associated with AUDs must be considered in the context of environmental and behavioral coexposures, sometimes referred to as the exposome, particularly with regard to cigarette smoking.

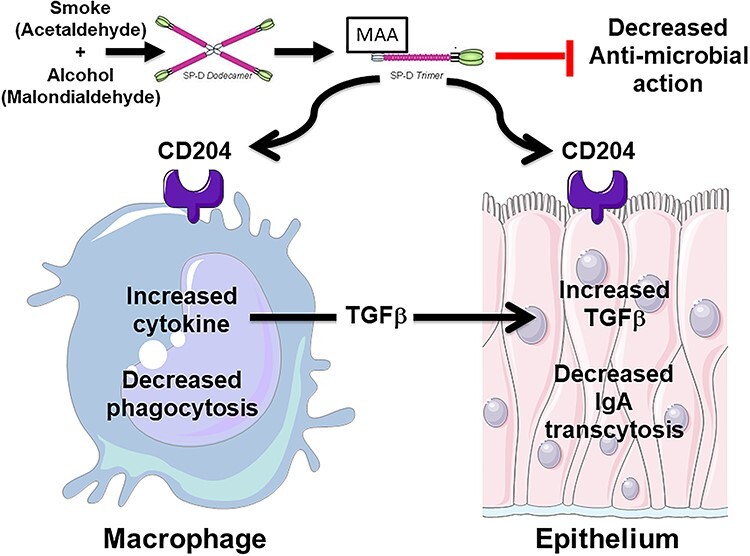

The lung represents a unique target for coexposure injury due to cigarette and alcohol consumption. Malondialdehyde and acetaldehyde, generated via both alcohol metabolism and the pyrolysis of tobacco, lead to the formation of stable hybrid adducts known as malondialdehyde–acetaldehyde (MAA) adducts (Sapkota and Wyatt, 2015). Adduct formation requires only the necessary aldehyde concentration and sufficient time for covalent adduction of lysine residues. Under this scenario, available lung protein could be subject to extracellular aldehydes generated from inhaled smoke and CYP-2E1-metabolized alcohol. Using a controlled-exposure mouse model, we identified several lung-adducted proteins that are altered through MAA adduction under conditions of smoke and alcohol coexposure that are not observed with either smoke or alcohol (McCaskill et al., 2011). Furthermore, we identified MAA adducts in the lungs of cigarette smokers who have AUD, whereas no such adducts were present in smokers only (Sapkota et al., 2017). Although the cumulative aldehyde threshold for lung protein adduction is likely only achieved by the combination of smoking and drinking, this scenario defines the importance of coexposure in creating unique second-hit injuries not seen by either exposure alone.

Injuries to airway epithelial cells in response to MAA adduct exposure include increased proinflammatory cytokine release (Wyatt et al., 2001), cilia slowing (Wyatt et al., 2012), and decreased epithelial wound repair in response to mechanical injury (Wyatt et al., 2005). Because lung surfactant proteins A and D (SPA and SPD) are key MAA adduction targets (McCaskill et al., 2011), there are likely pleiotropic effects on lung function beyond that of airway epithelium. We have found that macrophages bind MAA-adducted SPD (SPD–MAA) via a scavenger receptor A (CD204) pathway, resulting in decreased phagocytosis and bacteria killing (Sapkota et al., 2016). Because lung-secreted collectins such as SPA and SPD are essential innate defenses against lung viruses and bacteria, studies focus on whether SPD–MAA has any negative impact on antimicrobial activity and mucosal immunity.

Lung mucosal immunoglobulin A (sIgA) secretion is an important component of lung innate antimicrobial defense. sIgA deficiencies are associated with increased lung infections. Because the MAA moiety is highly immunogenic, the humoral response to MAA is the formation of antibodies. Specifically, IgA class antibodies to MAA were increased in the serum, but decreased in the lung lavage fluid of smokers with AUD (Sapkota et al., 2017). These changes were not observed in smokers or drinkers alone. These observations from a human cohort led to exploring whether SPD–MAA could change epithelial cell transcytosis of sIgA. Using an in vitro model of isolated human lung epithelial cells, it was observed that SPD–MAA exposure (with in vivo-detected concentrations of MAA) significantly decreases transcytosis of sIgA. SPD–MAA appeared to prevent the upregulated expression of the polymeric IgA receptor required for IgA binding at the basolateral surface. These responses were not observed with nonadducted SPD, which actually enhanced sIgA transcytosis. We replicated these observations in mice and the requirement for CD204 in the SPD–MAA response was revealed by using a scavenger receptor A knock-out mouse. Because both airway epithelial cells and macrophages bind MAA-adducted protein via CD204 (Berger et al., 2014), these data suggest that differential expression of CD204 polymorphisms may govern injury due to coexposure to smoke and alcohol.

Lastly, it is possible that aldehyde adduction of lung surfactant might alter the inherent antimicrobial effects of the collectin. Biologically active SPA and SPD bind to lung microbes and lead to the aggregation and killing of bacteria. These defensin proteins also provide antiviral protection to the epithelium. It is known that surfactant protein effects the lung epithelium from respiratory viral infection. Likewise, SPD protected bronchial epithelial cell viability in response to respiratory syncytial virus infection. No protection was conferred by SPD–MAA, however. Similarly, the enhanced binding, aggregation, and killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) caused by SPD were absent when the same surfactant is MAA adducted. These observations led to examining whether MAA adduction changes the structure, and therefore function of SPD. The antimicrobial form of SPD exists as a dodecamer, whereas the trimeric form of SPD is poorly antimicrobial and can be proinflammatory. Using nondenaturing gels, we found that SPD–MAA is in the trimeric form. Importantly, a potential lysine target for MAA adduction exists in the amino terminal region of SPD, the region that governs quaternary structure of the protein. Thus, aldehyde covalent modification of surfactant may lead to a structurally dependent change in protein function.

In conclusion, in vitro and in vivo models generated from lung coexposure to cigarette smoke and alcohol reveal the impact of reactive aldehydes. Surfactant protein is a likely target for such adduction with the stable hybrid MAA adduct. Once adducted, this modified protein undergoes structural changes, facilitating binding with the scavenger receptors on lung macrophages and epithelial cells, decreasing macrophage phagocytosis and epithelial sIgA secretion (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the direct antimicrobial characteristics of the surfactant itself are lost after MAA adduction.

Fig. 4.

Model diagram of malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducted (MAA) surfactant protein D (SPD) in antimicrobial airway defense. Elevated lung aldehydes from chronic exposure to alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking produce a stable covalent aldehyde adduct modification of native lung SPD, resulting in a structural shift from dodecameric SPD to trimeric SPD. Trimeric MAA-SPD exhibits decreased direct antimicrobial action and is capable of binding to scavenger receptor A (CD204) on airway macrophages and epithelial cells. MAA-SPD causes decreased macrophage phagocytosis and increased transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) production. TGFβ stimulation of mucosal airway epithelium results in decreased antimicrobial secretory IgA production.

FINAL SUMMARY

Overall, this review provides an update on the mechanistic aspect why which HFD, matrix stiffness, viral infection and hybrid aldehyde adducts exacerbated alcohol-induced organ damage. The following summarizes the take-home message of this review:

1. An animal model of chronic binge with moderate alcohol combined with fat rich diet recapitulated human lifestyle exhibiting increased steatosis, inflammation and fibrogenesis. A 12-week period of moderate alcohol superimposed on HFD activated several indicators of carcinogenesis-related molecules, indicating that the ‘second hit’ exacerbates liver injury compared to either agent alone (Fig. 1).

2. Stiffness plays a role in regulating hepatocytes function and contributes to stellate cells activation and progression of liver fibrosis during alcohol liver disease (Fig. 2).

3. Alcohol exacerbates liver pathology induced by HCV, HBV and HIV by either increasing apoptosis levels in hepatocytes (HCV and HIV infections) or suppressing the recognition of HBV-infected hepatocytes by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and enhancing HBV load (Fig. 3).

4. Reactive aldehydes generated from lung coexposure to both cigarette smoke and alcohol generates stable hybrid MAA adducts presumably on the surfactant protein. Once adducted, this modified protein undergoes structural changes allowing recognition by scavenger receptors on both macrophages and epithelial cells of the lung. Such receptor binding decreases macrophage phagocytosis and epithelial sIgA secretion. Furthermore, the direct antimicrobial characteristics of the surfactant itself are lost after MAA adduction (Fig. 4). Thus, the suppression of lung innate defense is multifaceted in alcohol misuse due to the comorbidity of cigarette smoking.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Omaha VA Medical Center. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Merit Review grants, BX004053 (K.K.K.), BX003635 (T.A.W.), Research Career Scientist Award IK6 BX003781 (T.A.W.); the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health CS-CAS NIOSH U54OH010162 (T.A.W.); NIH grants R01AA026723 (K.K.K.), R01AA027189 (N.A.O.), K01AA026864 (M.G.), P20GM113126 (S.K.-Project leader); UNL Office of Research and Development Biomedical Seed Grant (S.K.) and Nebraska Research Initiative Systems Grant (S.K.).

Contributor Information

Natalia A Osna, Research Service, Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, Nebraska 68105, USA; Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska 68198, USA.

Murali Ganesan, Research Service, Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, Nebraska 68105, USA; Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska 68198, USA.

Devanshi Seth, Drug Health Services, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Missenden Road, Camperdown, New South Wales 2050, Australia; Centenary Institute of Cancer Medicine and Cell Biology, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia.

Todd A Wyatt, Research Service, Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, Nebraska 68105, USA; Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska 68198, USA; Department of Environmental, Agricultural and Occupational Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska 68198, USA.

Srivatsan Kidambi, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588, USA.

Kusum K Kharbanda, Research Service, Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, Nebraska 68105, USA; Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska 68198, USA; Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska 68198, USA.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Asfari MM, Talal Sarmini M, Alomari M, et al. (2020) The association of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axley PD, Richardson CT, Singal AK (2019) Epidemiology of alcohol consumption and societal burden of alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 23:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataller R, Brenner DA (2005) Liver fibrosis. J Clin Investig 115:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataller R, North KE, Brenner DA (2003) Genetic polymorphisms and the progression of liver fibrosis: a critical appraisal. Hepatology 37:493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert TF, Juhling F, Ono A, et al. (2017) Hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of new generation antivirals. BMC Med 15:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger JP, Simet SM, DeVasure JM, et al. (2014) Malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde (MAA) adducted proteins bind to scavenger receptor A in airway epithelial cells. Alcohol 48:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertola A, Mathews S, Ki SH, et al. (2013) Mouse model of chronic and binge ethanol feeding (the NIAAA model). Nat Protoc 8:627–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruden DJT, McMahon BJ, Townshend-Bulson L, et al. (2017) Risk of end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related death by fibrosis stage in the hepatitis C Alaska cohort. Hepatology 66:37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun J-S, Suh Y-G, Yi H-S, et al. (2013) Activation of toll-like receptor 3 attenuates alcoholic liver injury by stimulating Kupffer cells and stellate cells to produce interleukin-10 in mice. J Hepatol 58:342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliari SR, Perepelyuk M, Soulas EM, et al. (2016) Gradually softening hydrogels for modeling hepatic stellate cell behavior during fibrosis regression. Integr Biol 8:720–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Xu MJ, Zhou Z, et al. (2015) Short- or long-term high-fat diet feeding plus acute ethanol binge synergistically induce acute liver injury in mice: an important role for CXCL1. Hepatology 62:1070–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang DJ, McCullough AJ (2014) The impact of obesity and metabolic syndrome on alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 18:157–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HSJ, Brouwer WP, Zanjir WMR, et al. (2020) Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with liver-related outcomes and all-cause mortality in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 71:539–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debes JD, Bohjanen PR, Boonstra A (2016) Mechanisms of accelerated liver fibrosis progression during HIV infection. J Clin Transl Hepatol 4:328–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duly AMP, Alani B, Huang EY-W, et al. (2015) Effect of multiple binge alcohol on diet-induced liver injury in a mouse model of obesity. Nutr Diabetes 5:e154–e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W, Sanyal AJ, Brunt EM, et al. (2012) Modest alcohol consumption is associated with decreased prevalence of steatohepatitis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). J Hepatol 57:384–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB (2011) Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 365:1118–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J, et al. (2020) MAFLD: a consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 158:1999–2014 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL (2003) Liver fibrosis–from bench to bedside. J Hepatol 38:38–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL (2015) Hepatic fibrosis: emerging therapies. Dig Dis 33:504–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Dagur RS, Makarov E, et al. (2018a) Matrix stiffness regulate apoptotic cell death in HIV-HCV co-infected hepatocytes: importance for liver fibrosis progression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 500:717–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Hindman J, Tillman B, et al. (2015a) FAT10 suppression stabilizes oxidized proteins in liver cells: effects of HCV and ethanol. Exp Mol Pathol 99:506–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Krutik VM, Makarov E, et al. (2019a) Acetaldehyde suppresses the display of HBV-MHC class I complexes on HBV-expressing hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 317:G127–G40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Natarajan SK, Zhang J, et al. (2016a) Role of apoptotic hepatocytes in HCV dissemination: regulation by acetaldehyde. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 310:G930–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, New-Aaron M, Dagur RS, et al. (2019b) Alcohol metabolism potentiates HIV-induced hepatotoxicity: contribution to end-stage liver disease. Biomolecules 9:851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Poluektova LY, Enweluzo C, et al. (2018b) Hepatitis C virus-infected apoptotic hepatocytes program macrophages and hepatic stellate cells for liver inflammation and fibrosis development: role of ethanol as a second hit. Biomolecules 8:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Poluektova LY, Kharbanda KK, et al. (2018c) Liver as a target of human immunodeficiency virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 24:4728–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Poluektova LY, Kharbanda KK, et al. (2019c) Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatotropic viruses co-morbidities as the inducers of liver injury progression. World J Gastroenterol 25:398–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Poluektova LY, Tuma DJ, et al. (2016b) Acetaldehyde disrupts interferon alpha signaling in hepatitis C virus-infected liver cells by up-regulating USP18. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40:2329–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Tikhanovich I, Vangimalla SS, et al. (2018d) Demethylase JMJD6 as a new regulator of interferon signaling: effects of HCV and ethanol metabolism. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:101–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Zhang J, Bronich T, et al. (2015b) Acetaldehyde accelerates HCV-induced impairment of innate immunity by suppressing methylation reactions in liver cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 309:G566–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan M, Allison E, Poluektova L, et al. (2020) Role of alcohol in pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 26:883–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Bataller R (2011) Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology 141:1572–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Morrison DS, Batty GD, et al. (2010) Effect of body mass index and alcohol consumption on liver disease: analysis of data from two prospective cohort studies. BMJ 340:c1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL (2011a) Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol 6:425–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL (2011b) Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol 6:425–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharbanda KK, Ronis MJJ, Shearn CT, et al. (2018) Role of nutrition in alcoholic liver disease: summary of the symposium at the ESBRA 2017 congress. Biomolecules 8:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Ki SS, Lee SD, et al. (2006) Elevated plasma osteopontin levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 101:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirpich IA, Warner DR, Feng W, et al. (2020) Mechanisms, biomarkers and targets for therapy in alcohol-associated liver injury: from genetics to nutrition: summary of the ISBRA 2018 symposium. Alcohol 83:105–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin J, Clayton MM, Liu J, et al. (2001) Chronic ethanol consumption stimulates hepatitis B virus gene expression and replication in transgenic mice. Hepatology 34:792–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YA, Wallace MC, Friedman SL (2015) Pathobiology of liver fibrosis: a translational success story. Gut 64:830–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Dranoff JA, Chan EP, et al. (2007) Transforming growth factor-beta and substrate stiffness regulate portal fibroblast activation in culture. Hepatology 46:1246–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZM, Kong CY, Zhang SL, et al. (2019) Alcohol and HBV synergistically promote hepatic steatosis. Ann Hepatol 18:913–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Zhang YJ (2017) Interference of apoptosis by hepatitis B virus. Viruses 9:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo L, McLennan SV, Williams PF, et al. (2011) Diabetes is a progression factor for hepatic fibrosis in a high fat fed mouse obesity model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 55:435–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe P, Galoosian A, Wong RJ (2019) Patients with alcoholic liver disease have worse functional status at time of liver transplant registration and greater waitlist and post-transplant mortality which is compounded by older age. Dig Dis Sci 65:1501–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaskill ML, Kharbanda KK, Tuma DJ, et al. (2011) Hybrid malondialdehyde and acetaldehyde protein adducts form in the lungs of mice exposed to alcohol and cigarette smoke. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35:1106–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min BY, Kim NY, Jang ES, et al. (2013) Ethanol potentiates hepatitis B virus replication through oxidative stress-dependent and -independent transcriptional activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 431:92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller M, Thulasingam S, Narasimhan M, et al. (2019, 2019) Stiffness induces NAFLD-like metabolic dysfunction in primary hepatocytes. Hepatology, 70,119A 70:119A. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C, Mueller S, Szabo G (2019) Non-invasive diagnosis and biomarkers in alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol 70:273–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya A, Iwasaki Y, Ohguchi S, et al. (2015) Roles of alcohol consumption in fatty liver: a longitudinal study. J Hepatol 62:921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison M, Hughes HY, Naggie S, et al. (2019) Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among individuals with HIV mono-infection: a growing concern? Dig Dis Sci 64:3394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller S, Millonig G, Sarovska L, et al. (2010) Increased liver stiffness in alcoholic liver disease: differentiating fibrosis from steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol 16:966–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan V, Berglund EJ, Chen DX, et al. (2015) Substrate stiffness regulates primary hepatocyte functions. RSC Adv 5:80956–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman MG, French SW, Zakhari S, et al. (2017) Alcohol, microbiome, life style influence alcohol and non-alcoholic organ damage. Exp Mol Pathol 102:162–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen AL, Bloomer SA, Chan EP, et al. (2011) Hepatic stellate cells require a stiff environment for myofibroblastic differentiation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301:G110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osna NA (2009) Hepatitis C virus and ethanol alter antigen presentation in liver cells. World J Gastroenterol 15:1201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osna NA, Donohue TM Jr, Kharbanda KK (2017) Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res 38:147–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osna NA, Ganesan M, Donohue TM (2014) Proteasome- and ethanol-dependent regulation of HCV-infection pathogenesis. Biomolecules 4:885–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osna NA, Ganesan M, Kharbanda KK (2015) Hepatitis C, innate immunity and alcohol: friends or foes? Biomolecules 5:76–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osna NA, White RL, Krutik VM, et al. (2008) Proteasome activation by hepatitis C core protein is reversed by ethanol-induced oxidative stress. Gastroenterology 134:2144–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani K, Korenaga M, Beard MR, et al. (2005) Hepatitis C virus core protein, cytochrome P450 2E1, and alcohol produce combined mitochondrial injury and cytotoxicity in hepatoma cells. Gastroenterology 128:96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandrea I, Happel KI, Amedee AM, et al. (2010) Alcohol's role in HIV transmission and disease progression. Alcohol Res Health 33:203–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Pareja JF, Caminoa A, Larrauri C, et al. (2009) HAART is associated with lower hepatic necroinflammatory activity in HIV-hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients with CD4 cell count of more than 350 cells/microl at the time of liver biopsy. AIDS 23:971–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peccerella T, Arslic-Schmitt T, Mueller S, et al. (2018) Chronic Ethanol Consumption and Generation of Etheno-DNA Adducts in Cancer-Prone Tissues. In Vasiliou V, Zakhari S, Mishra L, et al. (eds). Alcohol and Cancer—Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Vol. 1032. Cham: Switzerland Springer, 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RJ, Helbig KJ, Van der Hoek KH, et al. (2012) Osteopontin increases hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth through interaction with CD44. World J Gastroenterol 18:3389–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizner A, Shillingford N, Mitchell PD, et al. (2017) Hepatic inflammation may influence liver stiffness measurements by transient elastography in children and young adults. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 64:512–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaiah SK, Rittling S (2008) Pathophysiological role of osteopontin in hepatic inflammation, toxicity, and cancer. Toxicol Sci 103:4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran M, Chen H, Liang B, et al. (2018) Alcohol-induced autophagy via upregulation of PIASy promotes HCV replication in human hepatoma cells. Cell Death Dis 9:898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romberger DJ, Grant K (2004) Alcohol consumption and smoking status: the role of smoking cessation. Biomed Pharmacother 58:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe IA (2017) Lessons from epidemiology: the burden of liver disease. Dig Dis 35:304–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahai A, Malladi P, Melin-Aldana H, et al. (2004) Upregulation of osteopontin expression is involved in the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in a dietary murine model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287:G264–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota M, Burnham EL, DeVasure JM, et al. (2017) Malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde (MAA) protein adducts are found exclusively in the lungs of smokers with alcohol use disorders and are associated with systemic anti-MAA antibodies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41:2093–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota M, Kharbanda KK, Wyatt TA (2016) Malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde-adducted surfactant protein alters macrophage functions through scavenger receptor A. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40:2563–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota M, Wyatt TA (2015) Alcohol, aldehydes, adducts and airways. Biomolecules 5:2987–3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayiner M, Golabi P, Younossi ZM (2019) Disease burden of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global perspective. Dig Dis Sci 64:910–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seronello S, Ito C, Wakita T, et al. (2010) Ethanol enhances hepatitis C virus replication through lipid metabolism and elevated NADH/NAD+. J Biol Chem 285:845–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth D, Cordoba S, Gorrell MD, et al. (2006) Intrahepatic gene expression in human alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 45:306–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth D, Duly A, Kuo PC, et al. (2014) Osteopontin is an important mediator of alcoholic liver disease via hepatic stellate cell activation. World J Gastroenterol 20:13088–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang S, Plymoth A, Ge S, et al. (2011) Identification of osteopontin as a novel marker for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 55:483–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund SV, Brenner DA (2005) Molecular pathogenesis of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:102S–9S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim F (2015) Alcoholic drinks contribute to obesity and should come with mandatory calorie counts. BMJ 350:h2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singal AK, Anand BS (2007) Mechanisms of synergy between alcohol and hepatitis C virus. J Clin Gastroenterol 41:761–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singal AK, Satapathy SK, Reau N, et al. (2020) Hepatitis C remains leading indication for listings and receipt of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis 52:98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroffolini T, Sagnelli E, Sagnelli C, et al. (2020) The association between education level and chronic liver disease of any etiology. Eur J Intern Med 75:55–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syn W-K, Choi SS, Liaskou E, et al. (2010) Osteopontin is induced by hedgehog pathway activation and promotes fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 53:106–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Saha B, Bukong TN (2015) Alcohol and HCV: implications for liver cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 815:197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Wands JR, Eken A, et al. (2010) Alcohol and hepatitis C virus—interactions in immune dysfunctions and liver damage. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 34:1675–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takafuji V, Forgues M, Unsworth E, et al. (2007) An osteopontin fragment is essential for tumor cell invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 26:6361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulasingam S, Moeller M, Narasimhan M, et al. (2019) Stiffness induces hepatocytes metabolic reprograming during alcoholic fatty liver disease. Alcohol Clin Experimental Res 43:285a–a. [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein C, Friedman SL, Schuppan D, et al. (2015) Hepatic fibrosis: concept to treatment. J Hepatol 62:S15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbulcke H, Moreno C, Colle I, et al. (2016) Alcohol intake increases the risk of HCC in hepatitis C virus-related compensated cirrhosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol 65:543–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells RG (2013) Tissue mechanics and fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832:884–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells RG (2016) Location, location, location: cell-level mechanics in liver fibrosis. Hepatology 64:32–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt TA, Kharbanda KK, Tuma DJ, et al. (2001) Malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde-adducted bovine serum albumin activates protein kinase C and stimulates interleukin-8 release in bovine bronchial epithelial cells. Alcohol 25:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt TA, Kharbanda KK, Tuma DJ, et al. (2005) Malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts decrease bronchial epithelial wound repair. Alcohol 36:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt TA, Sisson JH, Allen-Gipson DS, et al. (2012) Co-exposure to cigarette smoke and alcohol decreases airway epithelial cell cilia beating in a protein kinase Cepsilon-dependent manner. Am J Pathol 181:431–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia MF, Bian H, Gao X (2019) NAFLD and diabetes: two sides of the same coin? Rationale for gene-based personalized NAFLD treatment. Front Pharmacol 10:877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeligar SM, Chen MM, Kovacs EJ, et al. (2016) Alcohol and lung injury and immunity. Alcohol 55:51–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeligar SM, Wyatt TA (2019) Alcohol and lung derangements: an overview. Alcohol 80:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]