Abstract

Although Latino immigrant men experience many health disparities, they are underrepresented in research to understand and address disparities. Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) has been identified to encourage participant engagement and increase representation in health disparities research. The CBPR conceptual model describes how partnership processes and study design impact participant engagement in research. Using this model, we sought to describe how these domains influenced participant engagement in a pilot randomized controlled trial of brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use (n = 121) among Latino immigrant men. We conducted interviews with a sample of study participants (n = 25) and reviewed logs maintained by ‘promotores’. We identified facilitators of participant engagement, including the relevance of the study topic, alignment with participants’ goals to improve their lives, partnerships with study staff that treated participants respectfully and offered access to resources. Further, men reported that the study time and location were convenient and that they appreciated being compensated for their time. Barriers to participant engagement included survey questions that were difficult to understand and competing demands of work responsibilities. Findings suggest that engaging underserved communities requires culturally responsive and community engagement strategies that promote trust. Future studies should further investigate how CBPR partnership processes can inform intervention research.

Introduction

Latino immigrant men face a number of structural and individual-level stressors which result in poor health outcomes, such as substance use, mental illness and chronic disease [1, 2]. They also have limited access to health insurance and health care [3]. Despite these significant public health problems, Latino immigrant men continue to be underrepresented in health research aimed at developing interventions to alleviate these burdens [4, 5]. Under-representation in research may be due to barriers to participation, such as mistrust of health and research institutions and competing demands [4–6]. Latino immigrants may be particularly reluctant to participate in research due to a history of exploitation in previous studies [7]. The current anti-immigrant political climate may make it even more difficult for researchers to build trust and engage with Latino immigrant communities [8, 9] or obtain research funding. For example, undocumented Latinos may fear that they will be reported to government officials if they participate in government funded research studies or reveal their immigration status as part of a research study [5, 10].

To help mitigate these barriers, Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approaches can help engage underserved populations in research to reduce health disparities [11–14]. CBPR is a collaborative research approach that brings together researchers and community members’ perspectives, skills, knowledge and expertise in an equitable partnership to address complex health problems [15, 16]. CBPR emphasizes shared power and knowledge democracy between communities and academic researchers [13]. Some positive outcomes of these partnerships include more ethical and culturally appropriate research protocols, developed through ongoing dialogue and negotiation with communities [16, 17]. Consequently, incorporating CBPR principles and approaches may help reduce fear and mistrust and improve knowledge sharing, eventually leading to more culturally relevant interventions that can increase engagement, improve health outcomes and reduce health disparities in underserved populations [13, 16].

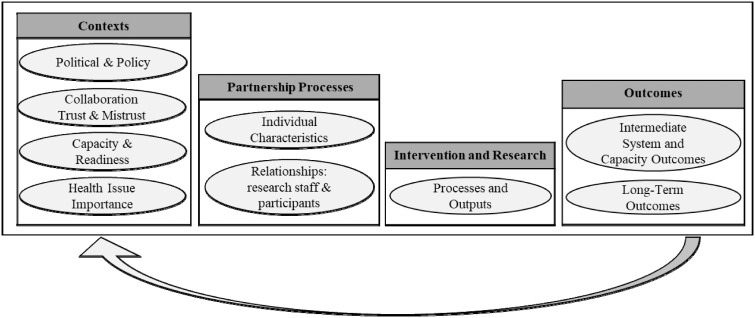

Wallerstein et al.’s CBPR conceptual model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and evaluating how four overarching domains—contexts, partnership processes, intervention and research, and outcomes—shape the collaborative research process [18]. The model posits that contexts can include the social and structural factors, political and policy factors, collaboration, trust and mistrust between the partners, capacity and readiness, and the perceived importance of health issue to the community [18]. The partnership processes domain includes partnership structures, individual characteristics of partners and relationships within partnerships. If these partnership processes are authentic, they have the potential to positively impact research design, intervention development and produce ‘culture-centered’ approaches that fit local populations and service domains. In turn, the implementation of successful research and interventions can lead to intermediate system and capacity outcomes, and eventually long-term health outcomes (see Fig. 1) [18].

Fig. 1.

CBPR conceptual model: domains of participant engagement from the Vida PURA study.

While there has been a growth in the use of CBPR strategies to engage underserved populations, little is known about best practices for engaging Latino immigrant men in CBPR. This study sought to describe how specific domains in the CBPR conceptual model (partnership processes and study design) contributed to participant engagement in the Vida PURA study. We define participant engagement as the various ways that community members are involved in a research study, including the decision to participate, staying engaged in the study and their attitudes about participation.

Background on the Vida PURA study

The Vida PURA study was a pilot randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a culturally adapted brief intervention to reduce unhealthy alcohol use among Latino day laborers [19]. The study built on a five-year collaboration between the Principal Investigator (I.O.) and Casa Latina, a community-based organization serving as a day labor worker center connecting clients with employment opportunities. The partnership began based on a mutual interest in addressing the health impact of immigration related stressors on the local Latino immigrant community. Previous collaborations included formative research to guide the development of the culturally adapted brief intervention, and a pilot study to test the feasibility of the intervention [20]. During the formative research phase, unhealthy alcohol use was identified as a community priority. The partnership follows CBPR principles of building on community strengths, facilitating co-learning and capacity building, disseminating findings to the community and a long-term commitment to sustained community health [21].

The study team included two bilingual and bicultural ‘promotores’ (lay community health workers) that conducted recruitment, data collection and delivered the intervention to study participants. The intervention consisted of a 30-min, motivational interviewing (MI) counseling session, which used a client-centered counseling style designed to elicit behavior change [22]. The sessions were conducted in Spanish and included personalized feedback, discussion of motives and consequences of drinking, and making a plan to change drinking behavior [23]. Participants in the Vida PURA study were included if they self-identified as Latino male, spoke Spanish, were born outside the US (immigrant) and had an alcohol screening score of six or greater on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Screened and eligible participants completed a baseline survey (n = 121) and were randomized into an intervention or control group. All participants completed interviewer-administered follow-up surveys two and eight weeks after the baseline survey. Participant retention rates were 87% for the two-week survey and 88% for the eight-week follow-up [20].

Despite using a CBPR approach, our research team had not previously documented the aspects of our partnership which contributed to our high levels of participant engagement. Using the CBPR conceptual model, we sought to describe which aspects of our partnership processes and study design impacted participant engagement using qualitative interviews with participants and study logs maintained by research staff. By describing how these domains within the CBPR conceptual model were operationalized in our study, we aim to provide recommendations for future research on how specific engagement strategies can optimize participation among Latino immigrant men in community-based health research.

Methods

Sample and design

We recruited a random sample of ∼20% of the n = 121 enrolled participants from the Vida PURA study who completed follow-up assessments and gave permission to be contacted in future studies to participate in qualitative interviews. Interviews (n = 25) took 30–45 min, were conducted in-person, in Spanish, in a private room at Casa Latina and were digitally audio recorded. Participants were asked for their consent prior to any data collection and received $30 for participating upon completion of the interview. Qualitative interviews were conducted by a graduate research assistant (V.T.) who did not participate in the intervention delivery or administering the surveys. In addition, we used data from detailed study logs kept by ‘promotores’ during the trial to describe recruitment and retention processes.

We completed interviews with 25 Latino immigrant men, all of whom had sought day labor employment at Casa Latina and had participated in the Vida PURA pilot trial (Table I). The participants’ mean age was 48 years. Most were from Mexico, and the average length of residence in the United States was 19 years. Most were very low income and had less than a high school education.

Table I.

Sample characteristics, n = 25

| Mean/n | (SD)/% | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 47.8 | (11.9) |

| Age in years | ||

| 18–34 | 4 | 16 |

| 35–49 | 8 | 32 |

| 50+ | 13 | 52 |

| Country of origin | ||

| Mexico | 13 | 52 |

| Central America | 10 | 40 |

| Other | 2 | 8 |

| Years living in the United States | 19.2 | (11.0) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 14 | 56 |

| Divorced/widowed | 5 | 20 |

| Married/cohabitating | 6 | 24 |

| Weekly salary | ||

| $200 or less | 9 | 36 |

| $200–$300 | 4 | 16 |

| $300–$400 | 4 | 16 |

| $400 or more | 8 | 32 |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary or less | 12 | 48 |

| High school graduate or GED | 7 | 28 |

| Some college or more | 6 | 24 |

| Hours of paid work in a typical week | 13.9 | (10.4) |

Data collection and analysis procedures

Qualitative interviews were semi-structured and the interview guide drew on partnership processes and study design described in the CBPR conceptual model [16]. Specifically, interview questions focused on motives to participate, interactions with research staff, best ways to maintain contact and barriers to participation.

Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed for accuracy by the research team. Data were analyzed using template analysis, a technique that utilizes a priori codes as well as emergent identification codes to identify themes [24]. The coding template was informed by the interview guide and the CBPR conceptual model. Transcripts were coded independently by two bilingual and bicultural graduate research assistants (F.R., V.T.), who met regularly to resolve any coding decisions, discrepancies and to revise the coding scheme as indicated. Themes were identified from the summarized queries for each code and reviewed by the research team to reach consensus on salient themes and examples. Salient representative quotes were translated from Spanish to English for presentation. We used Atlas.ti Version 8 to analyze interview data.

‘Promotores’ used logs to document recruitment, retention and data collection issues throughout the study. Comments from the logs were extracted and translated from Spanish to English. Comments were summarized and grouped into two categories: (i) logistical challenges for maintaining contact with participants and (ii) participant requests for additional resources. A final summary of themes from interviews and logs was shared with co-investigators and community advisors for assistance with interpretation. Data for the ‘promotor’ logs were analyzed by hand.

Results

Themes from qualitative interviews and ‘promotor’ logs

We identified four key themes with three subthemes that relate to the partnership processes and study design in the CBPR conceptual model: (i) participation was facilitated by the relevance of the study topic and a motivation to improve their life and help their community; (ii) personal relationships enabled access to resources and facilitated participation and engagement; (iii) logistical practicalities and financial incentives motivated participation. A fourth theme which relates to the intervention and research domain, that: (iv) study design and requirements sometimes inhibited participation and engagement. Below we describe themes and subthemes and highlight relevant quotes from the participants and logs. Table II also summarizes the themes and subthemes and provides examples for each domain.

Table II.

Mapping CBPR logic model with themes, subthemes and select quotes

| Partnership processes |

| Individual characteristics |

| Participation was facilitated by the relevance of the study topic to participant’s health and feelings that they were giving back and improving their lives |

| The relevance of the study topic to participants’ health facilitated participation |

|

| I want to improve my life and help my community |

|

| Relationships: research staff and participants |

| Personal relationships enabled access to resources, facilitated participation, and willingness to engage |

| Promotores treated me with respect (respeto) |

|

| I like to be contacted in-person by the promotores (personalismo) |

|

| Study staff provided access to resources outside the scope of the Vida PURA study aims |

|

| Intervention and research |

| Processes and outputs |

| Logistical practicalities and financial incentives motivated participation |

| The study time and location were convenient |

|

| ‘…we sometimes don’t get called for work, so we can come and participate.’ |

| Financial incentive—I appreciate being compensated for my time |

|

| Study design and requirements sometimes inhibited participation engagement |

|

Participation was facilitated by the relevance of the study topic and a motivation to improve their life and help their community

The relevance of the study topic to participants’ health facilitated participation

The relevance of the study topic was the single most common motive to participate. The men said that before deciding to participate, they needed to know more about the study. They were less interested in participating if the topic was not relevant to their lives, did not address their needs, or if they would be harmed in any way. Alcohol use was seen as a particularly relevant topic because they knew they had problems with their drinking and saw the study as an opportunity to receive ‘un consejo’ (advice) and ‘apoyo’ (support) to reduce their alcohol use.

I want to improve my life and help my community

Men also saw participation in the study as a way to ‘progresar’ (progress), ‘salir adelante’ (get ahead) or improve their lives. A few of the men felt that by participating in the study, they were being proactive about improving their lives, which in turn, affirmed their self-worth. In addition to improving their own lives, participants expressed their desire to support the Latino community by participating in the study. ‘…maybe my testimony will help other people…If you use [my testimony] for other people that are suffering with the same problem, then of course, I would participate.’ Other men also expressed their interest in collaborating with the research staff and engaging in mutual learning interactions. One participant said that he participated in order, ‘…to learn a little bit about what [the research team] is studying and to help each other.’

Personal relationships enabled access to resources and facilitated participation and engagement

Promotores treated me with (respeto) respect

Participants reported that the relationships they developed with the ‘promotores’ and other members of the research team played a key role in their willingness to engage in the study. As part of the study protocol, the research staff made weekly visits to Casa Latina for 10 weeks prior to data collection, to build familiarity and trust with the staff and potential participants. Also, throughout the study, the staff participated in Casa Latina events in an effort to maintain trust and rapport.

Participants were clearly familiar with the ‘promotores’ and other research staff. They mentioned certain characteristics of the research staff that were pivotal for developing good relationships, such as being trustworthy, transparent, kind, humble and knowledgeable. Participants reported that they were willing to participate in the study because they felt respected, acknowledged and cared for by the research staff. Another participant emphasized the importance of having trustworthy staff, ‘I know that what we talk about here, stays en confianza (in confidence) between us.’ However, participants reported that if the staff had been rude, authoritative or arrogant they would not have participated in the study.

I liked to be contacted in-person by the promotores (personalismo)

The most preferred modes of contact expressed by participants were in-person at Casa Latina. For example, one participant said, ‘I am more personal for things, for interviews and everything, for the doctor. My wife likes to do things over the phone. I go direct. I like to see the person with whom I will speak, and they understand me. I think you get better results when you speak in-person…Maybe it’s a custom that we have in our countries [of origin].’ The second most preferred mode of contact was by phone, and a few men were open to either calls or texts.

Study staff provided access to resources outside of the scope of the Vida PURA study aims

Data from the promotores’ logs noted any additional resources requested by the participants that were outside of the scope of the Vida PURA study aims. These included requests for assistance with immigration services, health insurance, housing, public transportation, employment opportunities and mental health support. The research staff made efforts to connect participants with other organizations that provide these services when requested. For example, a ‘promotor’ recorded the following in the logs, ‘I assisted a day worker with community resources for medical insurance and primary care services.’ Another issue that repeatedly surfaced as a major concern for participants was homelessness. In a few instances, the PI (India Ornelas) wrote letters of support for participants to use in their applications for low-income housing or immigration proceedings.

Logistical practicalities and financial incentives motivated participation

The study time and location were convenient

The men reported that they were able to participate in the study because it was conducted at a convenient location and time. Participants appreciated that the interviews were conducted at Casa Latina, while they were waiting for job assignments. One participant said, ‘…we sometimes don’t get called for work, so we can come and participate.’

Financial incentive—I appreciate being compensated for my time

Although a few participants reported that receiving a financial incentive was a strong motivation to participate, most participants reported that they would have still participated without it. The men expressed their gratitude for being paid for their time, since many were not working consistently, and needed the money. As one participant stated, ‘Oh of course, [the financial incentive helped]! That is another reason why I participated. Right now, things are slow. It’s raining and there is not much work.’ Many of the men mentioned that the money they received helped them pay for food, coffee, or transportation.

Study design and requirements sometimes inhibited participation and engagement

When asked about challenges experienced with the Vida PURA study, most participants gave neutral responses, such as, ‘Todo esta bien (everything is ok)’, but throughout the interview a few of the participants made suggestions and comments about ways to improve the study and intervention to further facilitate participation and engagement. About half of the men mentioned challenges with the survey questions (e.g. difficult to understand, repetitive or lengthy). For example, one participant said, ‘The questions are good, but sometimes they annoy you a little bit because [the ‘promotores’] repeat the [same questions] over and over.’ Additionally, others mentioned that it was difficult to answer some of the survey questions because they were unable to recall how much alcohol they had consumed in the past two weeks and another participant mentioned that the survey response-options were not always representative of his preferred response. ‘Promotores’ documented that a few of the participants faced challenges completing the surveys due to mental health conditions, alcohol intoxication and possible drug use. For example, one ‘promotor’ noted that the ‘Participant demonstrated high level of behavioral health needs and challenges [which made it] hard to…administer surveys in an appropriate timely manner.’

In addition, ‘promotores’ documented barriers to research participation. The loss to follow-up at two and eight weeks was often due to participants competing demands. For example, one of the promotor’s comments stated that the participant was not available to complete the follow-up surveys because ‘[he] went to Alaska to work in the fishing industry and may come back in one month.’ Another reason recorded by the ‘promotor’ for not being able to complete follow-up surveys was due to receiving services from a recovery center.

Discussion

Guided by the CBPR conceptual model, we conducted interviews and focus groups during the Vida PURA pilot trial to understand partnership processes and participant engagement. Findings suggest several factors facilitated engagement, including relevance of the study topic, alignment with participants’ goals to improve their lives and give back to their communities, and partnerships with study staff that offered access to resources and were experienced as respectful and personal. Some logistical aspects related to study design were facilitators, as well, but others were identified as barriers.

Our findings support previous work showing that racial/ethnic minority and immigrant populations are willing to engage in research under appropriate circumstances, especially when the research is seen as personally relevant to the participants [25]. Consistent with CBPR principles, participants expressed more interest when the research reflected their specific priorities and values. Our ability to recruit and retain participants in the Vida PURA study may have been related to the fact that the study addressed their needs and they perceived relevant benefits to participation.

Our findings reveal that one of the most important elements for engaging Latino immigrant men in research were the personal relationships developed with the ‘promotores’ and the time they spent with participants. The ‘promotores’ served as critical bridges between academic researchers and the community, largely due to their shared characteristics with study participants, including ethnicity, cultural knowledge, immigration experience and speaking Spanish [26]. This allowed ‘promotores’ to better understand the community needs and deliver the intervention in the context of a trusted relationship.

The ‘promotores’ further reduced other barriers to participation by using ‘culture-centered’ approaches that fit the local community [27]. Our findings show the importance of treating participants with ‘respeto’ (respect), a culture-specific value in which deference is shown to elders and authority figures [28, 29]. Participants were very responsive to the study procedures because they felt validated and respected by the ‘promotores’.

While not part of the original design of the intervention, the role of the ‘promotores’ in the study extended beyond addressing alcohol use. They were a resource that could help address social determinants like homelessness, access to job opportunities, immigration and health care services. Previous community-based studies among Latino men have also noted that the role of ‘promotores’ often extends to provide broader services than the original project scope [30, 31].

Study design elements were both facilitators and barriers to participation. The men found it easy to participate because the location and time were convenient and they got paid for their time. Previous studies have also shown increased engagement in research when it takes place in a setting that is accessible and convenient to the target population [32, 33]. By conducting data collection and intervention activities at the day labor worker center, while the men were waiting for job assignments, we were able to eliminate barriers such as transportation and scheduling conflicts with work [4, 5, 34]. However, for some of the men, especially for those with seasonal work, the timeline of the study was not aligned well with their lives. For example, during times when there are more employment opportunities, it may be challenging to engage participants who need to prioritize earning income.

There are several important limitations to consider when interpreting results from this study. While our study incorporated elements of the CBPR conceptual model to engage Latino immigrant men in research, we acknowledge that there are additional aspects of CBPR approaches we did not use or assess. For example, the contexts within which the study was conducted and the role of the community partner organization. Similarly, our findings are grounded in the specific context and relationships developed through our long-standing partnership and may not be generalizable to other contexts. Still, we hope that others working with similar populations can learn from our approaches. Another limitation is that the participants in this study may differ from those who choose not to participate. In our study, we selected participants from a recruited population who completed follow-up and agreed to further research participation, which likely indicates they are a more ‘research compliant’ group. Finally, participants’ responses may have been influenced by social desirability biases. Previous research indicates that Latinos often respond in socially desirable ways, meaning that they may have reported more favorable perceptions about their experience in our study out of an expectation to be polite or courteous [35].

Conclusion

In summary, this study described key aspects of partnership processes and study design which facilitated the engagement of Latino immigrant men in research, including selecting research topics that are relevant to the community, providing participants an opportunity to learn and give back to the community and strong relationships between the research staff and participants. Our findings suggest that intervention and research staff that are skilled at working with the target population are essential to building trust and engaging Latino immigrant men in research [5, 7, 34]. In addition, researchers should also make sure their study designs address the health concerns relevant to the community. By engaging Latino immigrant men in research, we have the potential to improve their health through shared knowledge between researchers and community members [36]. Future studies should further investigate how CBPR partnership processes can inform intervention and research approaches, and ultimately address Latino health disparities.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efforts of the entire research team as well as the support of our community partners Casa Latina. We further acknowledge the contributions of all the participants.

Funding

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1R34AA022696-01A1 to I.O., 3R34AA022696-02S1 to V.T.); the National Cancer Institute (T32CA092408 to V.T.); the Latino Scholars Graduate School Fellowship and the Graduate Opportunities and Minority Achievement Program Dissertation Fellowship.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Vasquez EP, Gonzalez-Guarda RM, De Santis JP. Acculturation, depression, self-esteem, and substance abuse among Hispanic men. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2011; 32: 90–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Velasco-Mondragon E, Jimenez A, Palladino-Davis AG et al. Hispanic health in the USA: a scoping review of the literature. Pub Health Rev 2016; 37: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pérez‐Escamilla R, Garcia J, Song D. Health care access among Hispanic immigrants:¿ Alguien está escuchando? [Is anybody listening?]. NAPA Bull 2010; 34: 47–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beech BM. Race & Research: Perspectives on Minority Participation in Health Studies. American Public Health Association, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Calderon JL, Baker RS, Fabrega H et al. An ethno-medical perspective on research participation: a qualitative pilot study. MedGenMed 2006; 8: 23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ceballos RM, Knerr S, Scott MA et al. Latino beliefs about biomedical research participation: a qualitative study on the US–Mexico border. J Emp Res Hum Res Ethics 2014; 9: 10–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Pub Health 2014; 104: e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morey BN. Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. Am J Pub Health 2018; 108: 460–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams DR, Medlock MM. Health effects of dramatic societal events—ramifications of the recent presidential election. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2295–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ornelas IJ, Yamanis TJ, Ruiz RA. The health of undocumented Latinx immigrants: what we know and future directions. Ann Rev Pub Health 2020; 41: 289–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol 2018; 73: 884–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice. Am J Pub Health 2008; 98: 216–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2007.114777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michener L, Cook J, Ahmed SM et al. Aligning the goals of community-engaged research: why and how academic health centers can successfully engage with communities to improve health. Acad Med 2012; 87: 285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wallerstein N, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract 2006; 7:312–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Ann Rev Pub Health 1998; 19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J et al. (eds). On Community-Based Participatory Research, 3rd edn San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maiter S, Simich L, Jacobson N, Wise J. Reciprocity: an ethic for community-based participatory action research. Act Res 2008; 6:305–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kastelic S, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J. Socio-ecologic framework for CBPR: development and testing of a model. In: Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J et al. (eds). Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity, 3rd edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2018, 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ornelas IJ, Allen C, Vaughan C et al. Vida PURA: a cultural adaptation of screening and brief intervention to reduce unhealthy drinking among Latino day laborers. Subst Abus 2015; 36: 264–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ornelas IJ, Doyle SR, Torres VN et al. Vida PURA: results from a pilot randomized trial of a culturally adapted screening and brief intervention to reduce unhealthy alcohol use among Latino day laborer. Transl Behav Med 2019; 9: 1233–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA et al. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles In: Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Processes to Outcomes, 3rd edn San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2018, 371–88. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd edn. New York: Guilford Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA et al. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140: 557–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. King N. Template analysis. In: Symon G, Cassell C (eds.). Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organizational Research. London: Sage Publications, 1998, 118–34. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med 2005; 3: e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Belone L, Lucero JE, Duran B et al. Community-based participatory research conceptual model: community partner consultation and face validity. Qual Health Res 2016; 26: 117–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dutta MJ, Anaele A, Jones C. Voices of hunger: addressing health disparities through the culture-centered approach. J Commun 2013; 63: 159–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Santiago-Rivera AL, Arredondo P, Gallardo-Cooper M. Counseling Latinos and la familia: A Practical Guide, vol. 17 Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Skaff MM, Chesla CA, de los Santos Mycue V, Fisher L. Lessons in cultural competence: adapting research methodology for Latino participants. J Community Psychol 2002; 30: 305–23. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Documet PI, Macia L, Thompson A et al. A male promotores network for Latinos: process evaluation from a community-based participatory project. Health Promot Pract 2016; 17: 332–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Singer M, Marxuach-Rodriquez L. Applying anthropology to the prevention of AIDS: the Latino gay men's health project. Hum Organ 1996; 55: 141–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson H et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 2: CD004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nilsen P. Brief alcohol intervention—where to from here? Challenges remain for research and practice. Addiction 2010; 105:954–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ojeda L, Flores LY, Meza RR, Morales A. Culturally competent qualitative research with Latino immigrants. Hisp J Behav Sci 2011; 33: 184–203. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hopwood CJ, Flato CG, Ambwani S et al. A comparison of Latino and Anglo socially desirable responding. J Clin Psychol 2009; 65: 769–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman AL et al. Reflections on researcher identity and power: the impact of positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Crit Sociol 2015; 41: 1045–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]