Abstract

Objectives:

Evaluate all-cause and endometriosis-related health care resource utilization and costs among newly diagnosed endometriosis patients with high-risk versus low-risk opioid use or patients with chronic versus non-chronic opioid use.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis of IBM MarketScan® Commercial Claims data from 2009 to 2018 was performed for females aged 18 to 49 with newly diagnosed endometriosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition code: 617.xx; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition code: N80.xx). Two sub-cohorts were identified: high-risk (⩾1 day with ⩾90 morphine milligram equivalents per day or ⩾1-day concomitant benzodiazepine use) or chronic opioid utilization (⩾90-day supply prescribed or ⩾10 opioid prescriptions). High-risk or chronic utilization was evaluated during the 12-month assessment period after the index date. Index date was the first opioid prescription within 12 months following endometriosis diagnosis. All outcomes were assessed over 12-month post-assessment period while adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics.

Results:

Out of 61,019 patients identified, 18,239 had high-risk opioid use and 5001 chronic opioid use. Health care resource utilization drivers were outpatient visits and pharmacy fills, which were higher among high-risk versus low-risk patients (outpatient visits: 17.49 vs 15.51; pharmacy fills: 19.58 vs 16.88, p < 0.0001). Chronic opioid users had a higher number of outpatient visits (19.53 vs 15.00, p < 0.0001) and pharmacy fills (23.18 vs 16.43, p < 0.0001) compared to non-chronic opioid users. High-risk opioid users had significantly higher all-cause health care costs compared to low-risk opioid users (US$16,377 vs US$13,153; p < 0.0001). Chronic opioid users also had significantly higher all-cause health care costs compared to non-chronic opioid users (US$20,930 vs US$12,272; p < 0.0001). Similar patterns were observed among endometriosis-related HCRU, except pharmacy fills among high-risk and chronic sub-cohorts.

Conclusion:

This analysis demonstrates significantly higher all-cause and endometriosis-related health care resource utilization and total costs for high-risk opioid users compared to low-risk opioid users among newly diagnosed endometriosis patients over 1 year. Similar trends were observed for comparing chronic opioid users with non-chronic opioid users, except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills and associated costs.

Keywords: cost, endometriosis, health care resource utilization, opioid, pain, real-world evidence

Introduction

Endometriosis, a chronic gynecological disease, is defined by an endometrial-type tissue outside of the uterine cavity that leads to inflammation and pelvic pain.1 Approximately 6%–10% of the United States, Canadian, and European women of reproductive age are affected.2–6 Endometriosis symptoms can include severe pelvic pain, even infertility.7 In a global survey of 1000 women with endometriosis, including women from the United States, 68%–71% presented with pain, 22%–30% presented with infertility, and 7.3%–29% presented with an endometrioma.8 Additional symptoms include bowel and bladder dysfunction, dysmenorrhea, abnormal uterine bleeding, low back pain, non-menstrual chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and chronic fatigue.1,4,7,8 Sexual dysfunction in women with endometriosis exacerbates psychological symptoms, such as depression and alexithymia.9,10

Endometriosis is a progressive disease where many patients deteriorate over time; therefore, timely diagnosis and treatments are important.11 First-line treatment consists of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and hormonal agents including estrogen-progestin contraceptives or progestin-only medications.4,12,13 Second-line treatment have historically included agents such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or danazol which have additional side effects.4,12,13 Emerging therapies, such as oral gonadotropin-releasing antagonists, are presenting additional options for therapy. If medical management fails for deep infiltrating disease, women may proceed with surgical evaluation and treatment with laparoscopy to excise/ablate the lesions; or even to hysterectomy with or without ovarian conservation.4,12,13 In the United States, more than 100,000 hysterectomies are performed annually for endometriosis.14

Women with endometriosis have a greater risk at receiving opioids.15,16 Compared with matched women without endometriosis, women with endometriosis have a greater risk to fill a prescription for an opioid (adjusted risk ratio (RR): 2.91) and for filling prescriptions for prolonged use, a higher dose, and/or a benzodiazepine.15 Women with endometriosis also have a greater risk at chronic opioid use (adjusted RR: 2.11).15,16 A 2019 retrospective analysis of opioid-using women with endometriosis found that the average (standard deviation, SD) number of opioid prescriptions received was 4.6 (6.7), average days supply was 61.1 (128.6) days, and 18.1% received ⩾90 days of opioids.17 A 2016 survey of fellows conducted by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) fellows found that 24% of patients with endometriosis received opioid medication prescribed by US OB/GYNs.16 A similar percentage of OB/GYNs were reported (27.6%) in a 2019 retrospective analysis, with other top opioid-prescribing specialties including family (23.4%) and internal medicine (9.2%) physicians.17

High-risk or chronic opioid use may act as gateways to opioid addiction, opioid-use disorders, illicit opioid use, and even opioid-related overdose deaths, thereby increasing the health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs.18,19 A previous study of adults without cancers had shown a high HCRU and expenditures among patients on chronic opioid therapy (COT) compared to patients without COT.20 Similarly, in addition to poor quality of life21 and pain,22 endometriosis has also been linked to increased direct and indirect costs.23–27 Compared to women without endometriosis, HCRU are significantly higher among endometriosis patients, including higher all-cause hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits, physician visits, outpatient visits, OB/GYN visits, and endometriosis-related surgical procedures.24–26,28 Similarly, all-cause costs among endometriosis patients are significantly higher compared to controls, ranging from US$11,556–US$42,020 versus US$4315–US$6124 annually, respectively.24–28 The total annual societal burden of endometriosis-associated symptoms was estimated at US$78.05 billion.20

However, to our knowledge, no studies provided insights on the impact of high-risk or chronic opioid use on HCRU and costs among endometriosis patients with opioid use. Therefore, a retrospective cohort study was conducted among newly diagnosed commercially insured endometriosis patients in United States to evaluate both all-cause and endometriosis-related HCRU and costs by service categories (outpatient, ER, inpatient, and pharmacy) among opioid-using endometriosis patients with high-risk or chronic opioid utilization.

Methods

Data source

This study is based on IBM® MarketScan® Commercial administrative claims database from 1 January 2009 to 30 September 2018 (study period). The Commercial Claims and Encounters database is comprised of fully adjudicated medical and pharmaceutical claims for more than 225 million unique patients from 300 contributing employers and 40 contributing health plans across the United States, which is approximately 62.9 million covered lives per year. It includes inpatient and outpatient diagnoses (in both International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) and Tenth Edition (ICD-10) format) and procedures (in Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Health care Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) formats) and both retail and mail-order prescription records. Available data on prescription records include the National Drug Code (NDC), J-codes, as well as the quantity of the medication dispensed. Additional data elements include demographic variables (age, gender, and geographic region), health plan type (e.g. health maintenance organization (HMO) and preferred provider organization), provider specialty, and eligibility dates related to plan enrollment and participation. These data represent commercially insured lives, and data contributors are generally self-insured employers.

This study is based on claims data. All database records are statistically de-identified and certified to be fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, institutional review board approval to conduct this study was not necessary.

Study design

This study was a retrospective analysis among female patients with newly diagnosed endometriosis. All-cause and endometriosis-related direct HCRU and costs were evaluated during a 12-month period for patients with high-risk versus low-risk or chronic versus non-chronic opioid use.

Study population

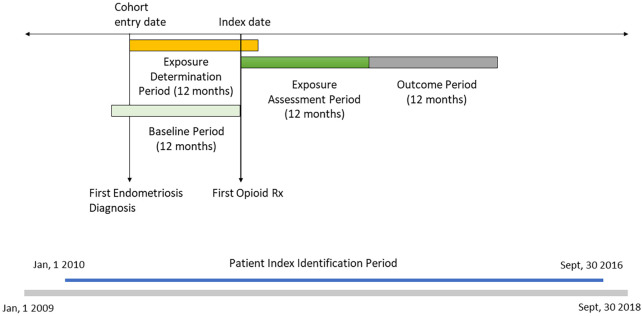

Females newly diagnosed with endometriosis (ICD-9 code: 617.xx; ICD-10 code: N80.xx) in the United States aged 18–49 between 1 January 2010 and 30 September 2015 were included, with the first endometriosis diagnosis date as the cohort entry date (Figure 1). Patients were required to have at least one record of opioids use within 12-month following their cohort entry date. Index date was defined as the first opioid prescription date. A minimum enrollment of 12-month prior to and 24-month post index date was required for each patient. Patients were excluded if they were diagnosed with malignant neoplasm anytime during the study period, had a diagnosis of endometriosis anytime prior to the cohort entry date during the study period, or had specific insurance plan types, such as HMO and point of service (POS) with capitation, during the 12-month baseline and 24-month follow-up periods.

Figure 1.

Timeline for evaluation of outcomes associated with high-risk and chronic opioid use.

Exposure determination period: time period from date of new endometriosis diagnosis running out to 12 months after diagnosis, which was used for determination of exposure (opioids vs no opioids). The date of first opioid prescription in the exposure determination period was determined as the index date.

Exposure assessment period: 12 months post-index date used for determination of high-risk and chronic opioid use.

Baseline period: 12 months prior to index date (not including index date) for evaluation of baseline covariates.

Outcome period: 12 months after the end of the exposure assessment period for determination of HCRU and costs.

Patient index identification period: time period for the potential index date of a patient. The period is between 1 January 2010 and 30 September 2016 since a minimum enrollment of 12 month prior to and 24 month post-index date was required for each patient.

Two stratification methods were used. First, the overall population was stratified into high-risk and low-risk opioid users. High-risk opioid use was defined as at least one day with ⩾90 morphine milligram equivalents per day or ⩾1-day concomitant opioid and benzodiazepine use during 12-month period post-index date (exposure assessment period). Second, the overall population was stratified into chronic and non-chronic opioid users. Chronic opioid use was defined as ⩾90 days of opioid supply prescribed or ⩾10 opioid prescriptions during the 12-month period post-index date (exposure assessment period).

Outcome measures

All-cause and endometriosis-related direct HCRU and costs were evaluated in total and by service category (outpatient, inpatient, ER, and pharmacy) over the 12-month post-exposure assessment period. Pharmacy fills were estimated using adjudicated prescription claims. Total length of stay (LOS) associated with inpatient visits were also evaluated. All costs were adjusted to 2018 costs using medical component of Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Adjudicated claims with primary or secondary diagnoses of endometriosis were used to calculate endometriosis-related HCRU and costs.29 Endometriosis-related pharmacy fills and costs were further specified for drugs primarily used in endometriosis management (danazol, goserelin, leuprolide, nafarelin, and estrogen/progestin oral contraceptives).

Study variables

Patient demographics measured on the index date, such as age, region, and insurance type, were reported. Clinical characteristics identified in the 12-month baseline period including the pain conditions (back/neck pain, joint pain/arthritis, headache/migraine, neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and other pain conditions including chest/visceral pain/wound/trauma), mental health conditions (anxiety/depression, mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance-use disorders (SUD)), prior opioid use, prior endometriosis-surgery and pregnancy status, and the Charlson Comorbidity index (CCI) were also represented. CCI is a continuous measure, which was computed using all medical claims (inpatient and outpatient) for 15 conditions (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, hemiplegia or paraplegia, diabetes (with and without complications), moderate to severe renal disease, mild and moderate to severe liver disease, peptic ulcer disease, rheumatologic disease, HIV/AIDS), since patients with malignant neoplasms were excluded from this analysis.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages; the significance for observed differences between high-risk and low-risk or chronic and non-chronic opioid users were evaluated using chi-square tests. Continuous variables were reported as mean with SD and t-tests were used to compare the mean differences between high-risk and low-risk or chronic and non-chronic opioid users.

Multivariable regression analyses were used to produce adjusted results for all outcomes of interest. Covariates included patient demographics and clinical characteristics, baseline outcomes, and index year. For HCRU, generalized linear models (GLM) with negative binomial (NB) distribution and log link function were used. For all-cause costs, GLM with Gamma distribution and log link function were used. A US$1 cost was added to those with zero costs.30 The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the mean ratio were also reported.

Since the percentage of patients with zero costs was greater than 10% for endometriosis-related costs, two-part models were used. First-part model estimated the probability of having a non-zero cost and the second part model estimated the costs encountered for those who have non-zero costs.31 The 95% CIs for the mean ratio between high-risk and low-risk or chronic and non-chronic opioid users were generated using bootstrapping method (repeated for 500 times).

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was determined by p value < 0.05.

Results

A total of 61,019 patients were identified in this analysis with 18,239 high-risk opioid users and 5001 chronic opioid users.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

High-risk versus low-risk opioid users

High-risk opioid users had a lower mean (SD) age compared to low-risk opioid users (38.1 (7.2) vs 38.3 (7.4) years, p = 0.0032; Table 1). Mean CCI was significantly higher for high-risk opioid users versus low-risk opioid users (0.33 (0.68) vs 0.25 (0.59), p < 0.0001). The high-risk opioid group had a significantly greater number of pain conditions compared to the low-risk opioid group (1.36 vs 0.96, p < 0.0001). The high-risk group had a higher percentage of prior opioid use pre-index compared to the low-risk group (58.9% vs 39.6%, p < 0.0001). Prior endometriosis-related surgery utilization was similar across groups (high-risk opioid users: 51.1%, low-risk opioid users: 51.3%, p = 0.6242).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for endometriosis patients with opioid use in the United States.

| Characteristic | Patients with high-risk opioid use | Patients with low-risk opioid use | p-value | Patients with chronic opioid use | Patients without chronic opioid use | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Number of unique patients | 18,239 | 100% | 42,780 | 100% | 5001 | 100% | 56,018 | 100% | ||

| Age group at index | ||||||||||

| 18–29 | 2351 | 12.9% | 5613 | 13.1% | <0.0001 | 619 | 12.4% | 7345 | 13.1% | <0.0001 |

| 30–39 | 7110 | 39.0% | 15,648 | 36.6% | 2010 | 40.2% | 20,748 | 37.0% | ||

| 40–49 | 8778 | 48.1% | 21,519 | 50.3% | 2372 | 47.4% | 27,925 | 49.9% | ||

| Age at index | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.1 | 7.2 | 38.3 | 7.4 | 0.0139 | 38.1 | 7.1 | 38.3 | 7.4 | 0.067 |

| Region at index | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 1969 | 10.8% | 5871 | 13.7% | 0.0034 | 573 | 11.5% | 7267 | 13.0% | <0.0001 |

| North Central | 4003 | 21.9% | 9683 | 22.6% | 1198 | 24.0% | 12,488 | 22.3% | ||

| South | 9023 | 49.5% | 21,668 | 50.6% | 2355 | 47.1% | 28,336 | 50.6% | ||

| West | 3147 | 17.3% | 5296 | 12.4% | 827 | 16.5% | 7616 | 13.6% | ||

| Unknown | 97 | 0.5% | 262 | 0.6% | 48 | 1.0% | 311 | 0.6% | ||

| Plan type at index | ||||||||||

| Comprehensive | 252 | 1.4% | 760 | 1.8% | 0.0011 | 139 | 2.8% | 873 | 1.6% | <0.0001 |

| EPO | 221 | 1.2% | 585 | 1.4% | 62 | 1.2% | 744 | 1.3% | ||

| POS | 1757 | 9.6% | 4018 | 9.4% | 442 | 8.8% | 5333 | 9.5% | ||

| PPO | 13,256 | 72.7% | 30,175 | 70.5% | 3636 | 72.7% | 39,795 | 71.0% | ||

| CDHP | 1460 | 8.0% | 4356 | 10.2% | 411 | 8.2% | 5405 | 9.6% | ||

| HDHP | 682 | 3.7% | 1741 | 4.1% | 157 | 3.1% | 2266 | 4.0% | ||

| Unknown | 611 | 3.3% | 1145 | 2.7% | 154 | 3.1% | 1602 | 2.9% | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score* | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.33 | 0.68 | 0.25 | 0.59 | <0.0001 | 0.47 | 0.84 | 0.25 | 0.59 | <0.0001 |

| Number of pain conditions (based on the following six pain categories) | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.36 | 1.27 | 0.96 | 1.08 | <0.0001 | 2.10 | 1.33 | 0.99 | 1.09 | <0.0001 |

| Number of patients with back/neck pain | ||||||||||

| Yes | 7108 | 39.0% | 11,760 | 27.5% | <0.0001 | 3119 | 62.4% | 15,749 | 28.1% | <0.0001 |

| No | 11,131 | 61.0% | 31,020 | 72.5% | 20,762 | 37.1% | 40,269 | 71.9% | ||

| Number of patients with joint pain/arthritis | ||||||||||

| Yes | 8165 | 44.8% | 14,904 | 34.8% | <0.0001 | 3082 | 61.6% | 19,987 | 35.7% | <0.0001 |

| No | 10,074 | 55.2% | 27,876 | 65.2% | 1919 | 38.4% | 36,031 | 64.3% | ||

| Number of patients with headache/migraine | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2674 | 14.7% | 3712 | 8.7% | <0.0001 | 1215 | 24.3% | 5171 | 9.2% | <0.0001 |

| No | 15,565 | 85.3% | 39,068 | 91.3% | 3786 | 75.7% | 50,847 | 90.8% | ||

| Number of patients with neuropathic pain | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1048 | 5.7% | 1443 | 3.4% | <0.0001 | 524 | 10.5% | 1967 | 3.5% | <0.0001 |

| No | 17,191 | 94.3% | 41,337 | 96.6% | 4477 | 89.5% | 54,051 | 96.5% | ||

| Number of patients with fibromyalgia | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1772 | 9.7% | 2141 | 5.0% | <0.0001 | 1031 | 20.6% | 2882 | 5.1% | <0.0001 |

| No | 16,467 | 90.3% | 40,639 | 95.0% | 3970 | 79.4% | 53,136 | 94.9% | ||

| Number of patients with other pain conditions (chest/visceral pain/wound/trauma) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 4018 | 22.0% | 7162 | 16.7% | <0.0001 | 1541 | 30.8% | 9639 | 17.2% | <0.0001 |

| No | 14,221 | 78.0% | 35,618 | 83.3% | 3460 | 69.2% | 46,379 | 82.8% | ||

| Number of mental health conditions (based on the following four mental health categories) | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.54 | 0.85 | 0.29 | 0.65 | <0.0001 | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.32 | 0.69 | <0.0001 |

| Number of patients with anxiety/depression | ||||||||||

| Yes | 5523 | 30.3% | 7302 | 17.1% | <0.0001 | 2049 | 41.0% | 10,776 | 19.2% | <0.0001 |

| No | 12,716 | 69.7% | 35,478 | 82.9% | 2952 | 59.0% | 45,242 | 80.8% | ||

| Number of patients with mood disorders | ||||||||||

| Yes | 3584 | 19.7% | 4464 | 10.4% | <0.0001 | 1363 | 27.3% | 6685 | 11.9% | <0.0001 |

| No | 14,655 | 80.3% | 38,316 | 89.6% | 3638 | 72.7% | 49,333 | 88.1% | ||

| Number of patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 280 | 1.5% | 230 | 0.5% | <0.0001 | 132 | 2.6% | 378 | 0.7% | <0.0001 |

| No | 17,959 | 98.5% | 42,550 | 99.5% | 4869 | 97.4% | 55,640 | 99.3% | ||

| Number of patients with substance-use disorder (SUD) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 386 | 2.1% | 243 | 0.6% | <0.0001 | 309 | 6.2% | 320 | 0.6% | <0.0001 |

| No | 17,853 | 97.9% | 42,537 | 99.4% | 4692 | 93.8% | 55,698 | 99.4% | ||

| Number of patients with prior opioid use | ||||||||||

| Yes | 10,738 | 58.9% | 16,945 | 39.6% | <0.0001 | 4666 | 93.3% | 23,017 | 41.1% | <0.0001 |

| No | 7501 | 41.1% | 25,835 | 60.4% | 335 | 6.7% | 33,001 | 58.9% | ||

| Number of patients with prior endometriosis-related surgery | ||||||||||

| Yes | 9326 | 51.1% | 21,967 | 51.3% | 0.6242 | 2149 | 43.0% | 29,144 | 52.0% | <0.0001 |

| No | 8913 | 48.9% | 20,813 | 48.7% | 2852 | 57.0% | 26,874 | 48.0% | ||

| Number of patients with pregnancy | ||||||||||

| Yes | 939 | 5.1% | 2477 | 5.8% | 0.0016 | 240 | 4.8% | 3176 | 5.7% | 0.0103 |

| No | 17,300 | 94.9% | 40,303 | 94.2% | 4761 | 95.2% | 52,842 | 94.3% | ||

SD = standard deviation.

CCI score was underestimated for some patients because of the intrinsic study design (i.e. patients with malignant neoplasms in the baseline were excluded from this study).

Chronic versus non-chronic opioid users

Similar mean (SD) ages were observed among chronic and non-chronic opioid users (38.1 (7.1) vs 38.3 (7.4) years, p = 0.0670; Table 1). The mean CCI was almost two-fold higher among chronic opioid users compared to non-chronic opioid users (0.47 (0.84) vs 0.25 (0.59), p < 0.0001). Chronic opioid users had a significantly greater number of pain conditions (2.10) compared to patients without chronic opioid use (0.99, p < 0.0001). Prior opioid use pre-index was significantly (p < 0.0001) higher among chronic opioid users (93.3%) versus non-chronic opioid users (41.1%). Prior endometriosis-related surgery was reported less frequently among chronic opioid users compared to non-chronic opioid users (43.0% vs 52.0%, p < 0.0001).

HCRU outcomes

High-risk versus low-risk opioid users

Results from multivariable regression analyses indicated that HCRU over 1 year was significantly higher for high-risk opioid users compared to low-risk opioid users in all service categories, except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted mean HCRU for endometriosis patients with opioid use in the United States.

| Characteristics | High- vs low-risk opioid users | Chronic vs non-chronic opioid users | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk opioid users | Low-risk opioid users | Estimated mean ratio with 95% CI | p-value | Chronic opioid users | Non-chronic opioid users | Estimated mean ratio with 95% CI | p-value | |

| All-cause HCRU | ||||||||

| Outpatient visits | 17.49 | 15.51 | 1.13 (1.11–1.14) | <0.0001 | 19.53 | 15.00 | 1.30 (1.27–1.33) | <0.0001 |

| ER visits | 0.71 | 0.53 | 1.33 (1.29–1.39) | <0.0001 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 1.67 (1.58–1.77) | <0.0001 |

| Inpatient visits | 0.21 | 0.16 | 1.30 (1.23–1.38) | <0.0001 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 1.87 (1.72–2.04) | <0.0001 |

| Total LOS | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.29 (1.17–1.42) | <0.0001 | 1.24 | 0.59 | 2.10 (1.80–2.46) | <0.0001 |

| Pharmacy fills | 19.58 | 16.88 | 1.16 (1.14–1.18) | <0.0001 | 23.18 | 16.43 | 1.41 (1.38–1.45) | <0.0001 |

| Endometriosis–related HCRU | ||||||||

| Outpatient visits | 0.265 | 0.223 | 1.19 (1.11–1.28) | <0.0001 | 0.336 | 0.197 | 1.71 (1.53–1.91) | <0.0001 |

| ER visits | 0.008 | 0.004 | 1.87 (1.48–2.37) | <0.0001 | 0.012 | 0.004 | 3.19 (2.37–4.28) | <0.0001 |

| Inpatient visits | 0.008 | 0.006 | 1.42 (1.17–1.71) | 0.0003 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 2.33 (1.80–3.01) | <0.0001 |

| Total LOS | 0.033 | 0.022 | 1.51 (1.10–2.07) | 0.0101 | 0.043 | 0.019 | 2.27 (1.37–3.78) | 0.0016 |

| Pharmacy fills | 0.054 | 0.056 | 0.98 (0.86–1.10) | 0.6962 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 0.8585 |

CI: confidence interval; ER: emergency room; HCRU: health care resource utilization; LOS: length of stay.

Estimated mean all-cause outpatient visits per patient among high-risk opioid users were higher than that for low-risk opioid users (17.49 vs 15.51, mean ratio: 1.13). Estimated mean all-cause ER visits per patient were 0.71 and 0.53 for high- and low-risk opioid users, respectively (mean ratio: 1.33). All-cause inpatient visits per patient for high-risk opioid users were greater than that for low-risk opioid users (estimated mean: 0.21 vs 0.16, mean ratio: 1.30), along with longer total LOS (estimated mean: 0.83 vs 0.65 days, mean ratio: 1.29). On average, all-cause pharmacy fills per patient among high-risk opioid users were 19.58 compared to 16.88 among low-risk opioid users (mean ratio: 1.16). All the comparisons were significant with p < 0.0001.

Except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills, estimated mean of endometriosis-related HCRU was significantly higher for high-risk opioid users compared to that for low-risk opioid users (outpatient: 0.265 vs 0.223, mean ratio: 1.19 and p < 0.0001; ER: 0.008 vs 0.004, mean ratio: 1.87 and p < 0.0001; inpatient: 0.008 vs 0.006, mean ratio: 1.42 and p = 0.0003; total LOS: 0.033 vs 0.022 days, mean ratio: 1.51 and p = 0.0101). However, high- and low-risk opioid users had similar endometriosis-related pharmacy fills (estimated mean: 0.054 vs 0.056 days, mean ratio: 0.98, p = 0.6962).

Similar trends were observed for unadjusted all-cause and endometriosis-related HCRU (Supplemental Table 1). On average, high-risk opioid users had higher HCRU per patient compared to low-risk opioid users. All the comparisons were significant with p < 0.0001 except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills.

Chronic versus non-chronic opioid users

Results from multivariable regression analyses indicated that HCRU more than 1 year was significantly higher for chronic opioid users compared to non-chronic opioid users in all service categories except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills (Table 2).

Estimated mean all-cause outpatient visits per patient among chronic opioid users were higher than that for non-chronic opioid users (19.53 vs 15.00, mean ratio: 1.30). Estimated mean all-cause ER visits per patient were 0.86 and 0.52 for chronic and non-chronic opioid users, respectively (mean ratio: 1.67). All-cause inpatient visits per patient for chronic opioid users were greater than that for non-chronic opioid users (estimated mean: 0.27 vs 0.14, mean ratio: 1.87), along with longer total LOS (estimated mean: 1.24 vs 0.59 days, mean ratio: 2.10). On average, all-cause pharmacy fills per patient among chronic opioid users were 23.18 compared to 16.43 among non-chronic opioid users (mean ratio: 1.41). All the differences were significant with p < 0.0001.

Except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills, estimated mean endometriosis-related HCRU was significantly higher for chronic opioid users compared to that for non-chronic opioid users (outpatient: 0.334 vs 0.197, mean ratio: 1.71 and p < 0.0001; ER: 0.012 vs 0.004, mean ratio: 3.19 and p < 0.0001; inpatient: 0.011 vs 0.005, mean ratio: 2.33 and p < 0.0001; total LOS: 0.043 vs 0.019 days, mean ratio: 2.27 and p = 0.0016). However, chronic and non-chronic opioid users had similar endometriosis-related pharmacy fills (estimated mean: 0.054 vs 0.055 days, mean ratio: 0.98, p = 0.8585).

Similar trends were observed for unadjusted all-cause and endometriosis-related HCRU (Supplemental Table 1). On average, chronic opioid users had higher HCRU per patient compared to non-chronic opioid users. All the comparisons were significant with p < 0.0001, except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills.

Health care costs

High-risk versus low-risk opioid users

Results from multivariable regression analyses indicated that estimated mean total costs over the 1 year was higher for high-risk opioid users compared to low-risk opioid users (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted mean costs for endometriosis patients with opioid use in the United States.

| Characteristics | High- vs low-risk opioid users | Chronic vs non-chronic opioid users | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk opioid users | Low-risk opioid users | Estimated mean ratio with 95% CI | p-value | Chronic opioid users | Non-chronic opioid users | Estimated mean ratio with 95% CI | p-value | |

| All-cause costs | ||||||||

| Total | US$16,377 | US$13,153 | 1.25 (1.22–1.27) | <0.0001 | US$20,930 | US$12,272 | 1.71 (1.64–1.77) | <0.0001 |

| Medical | US$14,561 | US$11,709 | 1.24 (1.21–1.27) | <0.0001 | US$18,563 | US$10,869 | 1.71 (1.64–1.78) | <0.0001 |

| Pharmacy | US$2255 | US$1806 | 1.25 (1.22–1.28) | <0.0001 | US$2809 | US$1717 | 1.64 (1.56–1.71) | <0.0001 |

| Endometriosis-related costs | ||||||||

| Total | US$525 | US$420 | 1.25 (1.12–1.39) | US$656 | US$380 | 1.73 (1.49–2.03) | ||

| Medical | US$520 | US$413 | 1.26 (1.13–1.42) | US$651 | US$363 | 1.79 (1.54–2.07) | ||

| Pharmacy | US$14 | US$12 | 1.10 (0.92–1.34) | US$19 | US$15 | 1.26 (0.90–1.69) | ||

CI: confidence interval; ER: emergency room; HCRU: health care resource utilization; LOS: length of stay.

Estimated mean all-cause total costs among high-risk opioid users were higher than that for low-risk opioid users (US$16,377 vs US$13,153, mean ratio: 1.25). Estimated mean all-cause medical costs were US$14,561 and US$11,709 for high- and low-risk opioid users, respectively (mean ratio: 1.24). Estimated mean all-cause pharmacy costs for high-risk opioid users were greater than that for low-risk opioid users (estimated mean: US$2255 vs US$1806, mean ratio: 1.25). All the comparisons were significant with p < 0.0001.

Estimated mean endometriosis-related total costs among high-risk opioid users were higher than that for low-risk opioid users (US$525 vs US$420, mean ratio: 1.25). Estimated mean endometriosis-related medical costs were US$520 and US$413 for high- and low-risk opioid users, respectively (mean ratio: 1.26). Estimated mean endometriosis-related pharmacy costs for high-risk opioid users were greater than that for low-risk opioid users (estimated mean: US$14 vs US$12, mean ratio: 1.10). All the comparisons were significant except for endometriosis-related pharmacy costs.

Similar trends were observed for unadjusted all-cause and endometriosis-related health care costs (Supplemental Table 2). On average, high-risk opioid users had higher all-cause and endometriosis-related health care costs compared to low-risk opioid users. All the comparisons were significant expect for endometriosis-related pharmacy costs. High utilization of outpatient visits was observed in this study for both high- and low-risk opioid users. Outpatient management was the driver of both HCRU magnitude and cost for these populations. Unadjusted all-cause costs for high-risk opioid users were driven by outpatient costs (55%); other contributors were pharmacy costs (20%), inpatient costs (19%), and ER costs (6%). Similar patterns were observed for all-cause costs among low-risk opioid users.

Chronic versus non-chronic opioid users

Results from multivariable regression analyses indicated that estimated mean total costs over 1 year was significantly higher for chronic opioid users compared to non-chronic opioid users (Table 3).

Estimated mean all-cause total costs among chronic opioid users were higher than that for non-chronic opioid users (US$20,930 vs US$12,272, mean ratio: 1.71). Estimated mean all-cause medical costs were US$18,563 and US$10,869 for chronic and non-chronic opioid users, respectively (mean ratio: 1.71). Estimated mean all-cause pharmacy costs for chronic opioid users were greater than that for non-chronic opioid users (estimated mean: US$2809 vs US$1717, mean ratio: 1.64). All the comparisons were significant with p < 0.0001.

Estimated mean endometriosis-related health care costs among chronic opioid users were higher than that for non-chronic opioid users (US$656 vs US$380, mean ratio: 1.73). Estimated mean endometriosis-related medical costs were US$651 and US$363 for chronic and non-chronic opioid users, respectively (mean ratio: 1.79). Estimated mean endometriosis-related pharmacy costs for chronic opioid users were greater than that for non-chronic opioid users (estimated mean: US$19 vs US$15, mean ratio: 1.26). All the comparisons were significant except for endometriosis-related pharmacy costs.

Similar trends were observed for unadjusted all-cause and endometriosis-related health care costs (Supplemental Table 2). On average, chronic opioid users had higher all-cause and endometriosis-related health care costs compared to non-chronic opioid users. All the comparisons were significant with p < 0.0001, expect for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills. High utilization of outpatient visits was observed in this study for both chronic- and non-chronic opioid users. Outpatient management was the driver of both HCRU magnitude and cost for these populations. Unadjusted all-cause costs for chronic opioid users were driven by outpatient costs (51%), while other contributors were pharmacy costs (22%), inpatient costs (21%), and ER costs (5%). Similar patterns were observed for all-cause costs among non-chronic opioid users.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated all-cause and endometriosis-related HCRU and costs associated with high-risk or chronic opioid use in a commercially insured endometriosis population in the United States. Within this analysis, opioid management is more directly captured in the all-cause outcomes, while endometriosis-related outcomes help characterize the disease-specific management baseline of this population.

Both unadjusted and multivariable analysis results demonstrated that high-risk opioid users had significantly higher outpatient, ER, and inpatient visits, as well as, longer total LOS compared to low-risk opioid users regardless if it was all-cause or endometriosis related. Compared to low-risk opioid users, high-risk opioid users had significantly higher all-cause pharmacy fills, although they had similar endometriosis-related pharmacy fills. This pharmacy fill trend aligns with the author’s expectations, as the endometriosis-related pharmacy fills were defined with specific medications (including danazol, goserelin, leuprolide, nafarelin, and estrogen/progestin oral contraceptives), all-cause pharmacy fills would represent opioids and other indications’ non-opioid medications. The HCRU analysis stratified by chronic and non-chronic opioid use also showed the same trend. In addition, chronic opioid users were also associated with significantly higher HCRU for all service categories except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills compared to non-chronic opioid users. The differences in HCRU between chronic and non-chronic opioid users were greater than that between high- and low-risk opioid users. For example, estimated mean all-cause outpatient visits per patient for high-risk opioid users were 13% more than that for low-risk opioid users (mean ratio: 1.13; 95% CI (1.11–1.14)), but chronic opioid users had 30% more all-cause outpatient visits per patient on average compared to non-chronic opioid users (mean ratio: 1.30; 95% CI (1.27–1.33)).

All-cause total, medical, and pharmacy costs for high-risk opioid users were significantly higher than those for low-risk opioid users according to both unadjusted and multivariable analysis. The endometriosis-related costs analysis results showed that significantly higher total and medical costs were observed in high-risk opioid users compared to low-risk opioid users, but not for endometriosis-related pharmacy costs. Similar results were also identified when comparing chronic opioid users to non-chronic opioid users. In addition, the differences in costs between chronic and non-chronic opioid users were greater than that between high- and low-risk opioid users. For example, chronic opioid users had 71% more all-cause total costs per patient compared to non-chronic opioid users (estimated mean: US$20,930 vs US$12,272, mean ratio: 1.71; 95% CI (1.64–1.77) but high-risk opioid users had 25% more all-cause total costs per patient compared to low-risk opioid users (estimated mean: US$16,377 vs US$13,153, mean ratio: 1.25; 95% CI (1.22–1.27).

Based on this study, total direct health care costs for newly diagnosed endometriosis patients with opioid use were largely driven by medical costs. Specifically, around 70% of medical costs were outpatient costs, followed by 25% inpatient costs and 5% ER costs. Patients with high-risk opioid use incurred all-cause total costs of US$1365 per patient per month (PPPM) compared to patients with low-risk opioid use (US$1096 PPPM), which were aligned with the existing literature (total costs of endometriosis ranged US$963–3502 PPPM).24–28 For patients with chronic opioid use, all-cause total costs were US$1744 PPPM compared to patients with non-chronic opioid use (US$1023 PPPM), which was also consistent with previous studies.24–28

The results for both of these populations align with the existing literature on HCRU.24 The two drivers were physician office visits and prescription claims among endometriosis patients verse the control population (percentage of patients with office visits: 97% vs 87%; outpatient prescription claim: 96% vs 83%). Other contributors identified were ER (32% vs 18%) and inpatient visits (29% vs 6%).24 Outpatient management is observed to drives cost, but this is a medical complex population at-risk for further HCRU. As this is a newly diagnosed population, we may expect HCRU utilization to continue to rise in the future.

One of the strengths of this analysis is that the controls in this analysis are endometriosis patients, unlike the existing endometriosis literature which has previously used patients without endometriosis.20,24–28,32,33 Another strength of this study is the exposure period is separated from the outcomes period. Finally, this study utilizes a geographically diverse commercial database.

Limitations

This study has several limitations inherent to claims data. The findings of this study are limited to IBM MarketScan commercial population and may not be generalizable to the entire United States. Claims data do not allow use of certain variables such as race, pain, and severity. Chronic opioid use was defined as at least 90 days of opioid supply prescribed or at least 10 opioid prescriptions during the 12-month period post-index date. The exact reason for chronic opioid use cannot be determined from the claims data; only observed according to the definition of chronic use. Reasons for chronic opioid use among endometriosis patients may vary and be impacted by the type, location, severity, and persistence of pain and symptoms. Women with endometriosis can experience pain in many areas, including low back pain, non-menstrual chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, dyschezia, or pain in the vaginal and abdominopelvic area. In addition, the persistence of symptoms, such as bowel/bladder dysfunction, abnormal uterine bleeding, or infertility, in the setting of failed medical (first-line use of NSAIDs or hormonal agents) or surgical management (laparoscopy or hysterectomy) may lead to chronic opioid use. This analysis does not capture opioid prescriptions paid for by cash or illicitly obtained for or administered during an inpatient study. Upcoding or miscoding may not reflect actual estimations and the analysis can only identify prescriptions filled and not prescriptions taken. The statistical differences do not imply clinical differences. Zero cost was observed for some patients in the cohort, which might be caused by billing error or claims adjustment in the database. The uncertainty of this may underestimate the true health care costs. However, appropriate modeling techniques were adopted in order to minimize the bias. The study’s objective was to describe the impact of opioids use patterns on health care burden among newly diagnosed endometriosis patients in the United States, but did not include identifying the underlying reason for using opioids, so patients may be prescribed opioids for a condition other than endometriosis. Finally, causal inference cannot be drawn from this analysis considering the intrinsic observational study design.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable and detailed information on the economic burden for newly diagnosed endometriosis patients with high-risk or chronic opioid use. Results from this analysis demonstrated significantly higher all-cause and endometriosis-related HCRU and total costs associated with high-risk or chronic opioid use in this population, except for endometriosis-related pharmacy fills and associated costs. From a managed care perspective, the burden of early management appears to be driven by outpatient services. Given the likely need for continued pain management in this population, trends in HCRU and costs may be expected to further rise as women will need care throughout their lifetime for this chronic disease management.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-whe-10.1177_1745506520965898 for The impact of high-risk and chronic opioid use among commercially insured endometriosis patients on health care resource utilization and costs in the United States by Stephanie J Estes, Ahmed M Soliman, Marko Zivkovic, Divyan Chopra and Xuelian Zhu in Women’s Health

Acknowledgments

Editorial/medical writing support for this manuscript was provided by Patrick Callahan, PharmD, MS and Nicole Safran, MPH, employees of Genesis Research, and funded by AbbVie.

Footnotes

Authors’ note: Description of prior peer-reviewed presentation at a professional/scientific conference: Preliminary results of this study were submitted for a poster session at the 2020 ISPOR conference; May 16-20, 2020; Orlando, FL

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: S.J.E. is a paid consultant for AbbVie Inc, provides AbbVie Inc. with research support and participates in their Speaker’s Bureau and provides research support for ObsEva and Ferring. A.M. S. is an employee of and own stock/stock options in AbbVie. M.Z. and X.Z. are employees of Genesis Research and were paid consultants for AbbVie Inc. D.C. is affiliated with university of Arkansas for Medical sciences and a paid contractor for AbbVie Inc.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by AbbVie.

ORCID iD: Stephanie J Estes  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8916-2537

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8916-2537

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, et al. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014; 10(5): 261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eskenazi B, Warner ML. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1997; 24: 29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists (ACOG). Practice bulletin No. 114: management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 116(1): 223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dunselman GAJ, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2014; 29(3): 400–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh S, Soliman AM, Rahal Y, et al. Prevalence, symptomatic burden, and diagnosis of endometriosis in Canada: cross-sectional survey of 30 000 women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2020; 42(7): 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fuldeore MJ, Soliman AM. Prevalence and symptomatic burden of diagnosed endometriosis in the United States: National estimates from a cross-sectional survey of 59,411 women. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2017; 82(5): 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bourdel N, Chauvet P, Billone V, et al. Systematic review of quality of life measures in patients with endometriosis. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(1): e0208464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sinaii N, Plumb K, Cotton L, et al. Differences in characteristics among 1,000 women with endometriosis based on extent of disease. Fertil Steril 2008; 89(3): 538–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Melis I, Agus M, Pluchino N, et al. Alexithymia in women with deep endometriosis? A pilot study. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord 2014; 6(1): 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Melis I, Litta P, Nappi L, et al. Sexual function in women with deep endometriosis: correlation with quality of life, intensity of pain, depression, anxiety, and body image. Int J Sex Heal 2015; 27(2): 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 11. van der Zanden M, Nap AW. Knowledge of, and treatment strategies for, endometriosis among general practitioners. Reprod Biomed Online 2016; 32(5): 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2014; 101(4): 927–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Committee on Adolescent Health Care. ACOG committee opinion number 760: dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in the adolescent. Obstet Gynecol 2018; 132: e249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rizk B, Fischer AS, Lotfy HA, et al. Recurrence of endometriosis after hysterectomy. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2014; 6(4): 219–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lamvu G, Soliman AM, Manthena SR, et al. Patterns of prescription opioid use in women with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 133(6): 1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Madsen AM, Stark LM, Has P, et al. Opioid knowledge and prescribing practices among obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2018; 131(1): 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Estes SJ, Soliman AM, Johns B, et al. Opioid utilization following endometriosis diagnosis: retrospective analysis of more than 100,000 women. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 133(5): 111S. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a national institutes of health pathways to prevention workshop. Ann Intern Med 2015; 162: 276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy, et al. Trends in opioid use, harms, and treatment. In: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy, et al. (eds) Pain management and the opioid epidemic: balancing societal and individual benefits and risks of prescription opioid use. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod 2012; 27(5): 1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferreira ALL, Bessa MMM, Drezett J, et al. Quality of life of the woman carrier of endometriosis: systematized review. Reproduc E Climate 2016; 31: 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morotti M, Vincent K, Becker CM. Mechanisms of pain in endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017; 209: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Soliman AM, Coyne KS, Gries KS, et al. The effect of endometriosis symptoms on absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace and at home. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2017; 23(7): 745–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soliman AM, Surrey E, Bonafede M, et al. Real-world evaluation of direct and indirect economic burden among endometriosis patients in the United States. Adv Ther 2018; 35(3): 408–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fuldeore M, Yang H, Du EX, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in women diagnosed with endometriosis before and after diagnosis: a longitudinal analysis of claims databases. Fertil Steril 2015; 103(1): 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Estes SJ, Soliman AM, Epstein AJ, et al. National trends in inpatient endometriosis admissions: patients, procedures and outcomes 2006-2015. PLoS ONE 2019; 14: e0222889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Soliman AM, Surrey ES, Bonafede M, et al. Health care utilization and costs associated with endometriosis among women with Medicaid insurance. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2019; 25(5): 566–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mirkin D, Murphy-Barron C, Iwasaki K. Actuarial analysis of private payer administrative claims data for women with endometriosis. J Manag Care Pharm 2007; 13(3): 262–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hepp Z, Lage MJ, Espaillat R, et al. The association between adherence to levothyroxine and economic and clinical outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism in the US. J Med Econ 2018; 21(9): 912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Basu A, Polsky D, Manning WG. Estimating treatment effects on healthcare costs under exogeneity: is there a ‘magic bullet’? Heal Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2011; 11(1–2): 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Casciano JP, Dotiwala ZJ, Martin BC, et al. The costs of warfarin underuse and nonadherence in patients with atrial fibrillation: a commercial insurer perspective. J Manag Care Pharm 2013; 19(4): 302–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs associated with endometriosis: a systematic literature review. Hum Reprod 2016; 31(4): 712–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Koltermann KC, Dornquast C, Ebert AD, et al. Economic burden of endometriosis: a systematic review. Ann Reprod Med Treat 2017; 2: 1015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-whe-10.1177_1745506520965898 for The impact of high-risk and chronic opioid use among commercially insured endometriosis patients on health care resource utilization and costs in the United States by Stephanie J Estes, Ahmed M Soliman, Marko Zivkovic, Divyan Chopra and Xuelian Zhu in Women’s Health