Abstract

Background and Aims:

Because of its low prevalence, metastatic breast cancer (MBC) in males is managed based on clinical experience with women. Using a real-life database, we aim to provide a comprehensive analysis of male MBC characteristics, management and outcome.

Methods:

The Epidemiological Strategy and Medical Economics Data Platform collected data for all men and women ⩾18 years with MBC in 18 participating French Comprehensive Cancer Centers from January 2008 to November 2016. Demographic, clinical, and pathological characteristics were retrieved, as was treatment modality. Men were matched 1:1 to women with similar characteristics.

Results:

Of 16,701 evaluable patients, 149 (0.89%) men were identified. These men were older (median age 69 years) and predominantly had hormone receptor HR+/HER2– disease (78.3%). Median overall survival (OS) was 41.8 months [95% confidence interval (CI: 26.9–49.7)] and similar to women. Median progression-free survival (PFS) with first-line therapy was 9.3 months [95% CI (7.4–11.5)]. In the HR+/HER2– subpopulation, endocrine therapy (ET) alone was the frontline treatment for 43% of patients, including antiestrogens (n = 19), aromatase inhibitors (n = 15) with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogs (n = 3), and various sequential treatments. Median PFS achieved by frontline ET alone was similar in men [9.8 months, 95% CI (6.9–17.4)] and in women [13 months, 95% CI (8.4–30.9)] (p = 0.80). PFS was similar for HR+/HER2– men receiving upfront ET or chemotherapy: 9.8 months [95% CI (6.9–17.4)] versus 9.5 months [95% CI (7.4–11.7)] (p = 0.22), respectively.

Conclusion:

MBC management in men and women leads to similar outcomes, especially in HR+/HER2– patients for whom ET should also be a cornerstone. Unsolved questions remain and successfully recruiting trials for men are still lacking.

Keywords: male breast cancer, metastatic breast cancer, real-life study

Introduction

Male breast cancer (BC) is a rare disease, with less than 1% of all BC cases occurring in men. In the United States (US), around 2670 new male cases are anticipated in 2020 with 500 predicted deaths.1 Because of this low prevalence, characterizing the disease in men has been challenging, and the management of male BC is generally based on clinical experience with women.2,3 That approach may be suboptimal considering the difference in hormonal milieu between men and women. In the metastatic setting, data on male BC are even more limited. Only small retrospective series with incomplete data on clinical management, disease characteristics, and outcome have been reported.4–8 Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has stressed the urgent need to develop BC drugs for both the male and female populations.9 The eligibility criteria for BC clinical drug trials should make it possible to include both men and women.

Consequently, a number of unsolved questions influence daily practices and further research is needed to improve the stratification and management of males with metastatic disease. The French Epidemiological Strategy and Medical Economics (ESME) metastatic breast cancer (MBC) data platform is a unique, multicenter database collecting all MBC cases at 18 comprehensive cancer centers over the past 10 years. Using this data source, we aimed to provide a comprehensive view of the management and outcome of metastatic male BC in real-life settings and compare it with women.

Materials and methods

Study design

This noninterventional, retrospective, comparative study was carried out to describe the outcome of male MBC patients included in the ESME–MBC database. This database is an ongoing unique national cohort gathering real-life individual retrospective data from all consecutive patients, male or female, ⩾18 years, who started treatment for MBC in 1 of the 18 cancer centers participating in the ESME research program from 1 January 2008 to 30 November 2016. Patient-related data, hospitalization-related data, and pharmacy-related data are collected, including patient demographic characteristics, pathology, and outcomes. Treatment strategies are also recorded, including chemotherapy (CT), targeted agents, endocrine therapy (ET), radiotherapy (RT), and other local treatments, as well as supportive therapies such as bone-targeted agents (BTAs).

In this study, patient selection focused on all men in the database with no exclusion criteria. Data were collected until the cutoff date (30 November 2016), death, or date of last contact if lost to follow up.

An independent ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud Est II 2015-79) approved our analysis. No formal informed consent was required, but all patients had approved the reuse of their electronically recorded data. In compliance with French regulations, the ESME–MBC database was authorized by the French data protection authority (Registration ID 1704113 and Authorization N° DE-2013.-117) and managed by R&D UNICANCER in accordance with current best practice guidelines.10

Objectives and endpoints

The primary objectives were to evaluate the incidence of men in the ESME–MBC database and to retrieve the disease characteristics and management. Our secondary objectives were description of male outcomes by treatment type and comparison with a matched population of women selected from the database.

The study’s primary endpoint was the rate of metastatic breast cancer in men in the ESME–MBC database. Secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), defined as the time between the date of first metastasis diagnosis and date of death from any cause, and progression-free survival (PFS) as the time between the date of first metastasis diagnosis and date of first disease progression or death. A treatment line was defined as a given therapeutic strategy provided until progression, and therefore could involve several treatments including CT, targeted agents, and ET. Disease progression was defined as the occurrence of a new metastatic site, progression of existing metastases, local or locoregional recurrence of the primary tumor, discontinuation of CT, and/or targeted therapy due to metastatic progression, or death from any cause.

Tumor subtype assessment and evaluation

Standard guidelines were applied to any analysis performed within the ESME database. HER2 and hormone receptor (HR) status were derived from existing metastatic tissue sampling results if available, or, if not available, from most recent early disease samples. Breast cancer was HR+ if estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR) expression was ⩾10% (immunohistochemistry). HER2 immunohistochemical score 3+ or IHC score 2+ with positive fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH) classified the tumors as HER2+.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics [mean and standard deviation (SD)] and compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Student t test, when appropriate; a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Both OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and median follow-up durations using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. Survival curves with their log-rank tests were generated. Censored data were summarized descriptively for the two groups. We conducted a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for OS in the HR+/HER2– population. Variables, including prognostic factors, were selected for univariate analysis. Performance status was not included in the analysis due to the number of missing data. For each variable of interest, univariate coefficients were estimated with a Cox model using the available data for this variable. A multivariate analysis was then conducted using the backward variable selection method, checking for potential cofounding effects at each step. The initial model included all variables that were found to have a significant or moderate prognostic effect (p < 0.25) during the univariate analysis. The backward variable selection that led to the final model was realized using the sample of patients with complete data for every variable included in the initial model. The final model was then re-estimated using the sample of patient with complete data for the selected variables. The multivariate analysis was performed using a Cox model adjusted and stratified for prognostic survival factors and potential cofounders. The Breslow estimator was used to generate adjusted survival curves. HRs were presented on a descriptive basis with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

To allow specific comparisons, a matched population of women was selected according to the following criteria: age (years) at first metastatic relapse [<50 ; (50–70); >70], tumor grade according to Scarff–Bloom–Richardson, presence of visceral metastasis or not, HR/HER2 subtype, de novo metastatic disease or not, and adjuvant CT or not. The continuous variable of age was used in case of several matched female.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software (version 9.4; SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and management

Of the 16,701 evaluable patients in the database, 149 men (0.89%) met the study’s inclusion criteria. The main characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1. The median age at metastatic diagnosis was 69 years (range 44–90). HR+/HER2– disease was predominant (78.3%; n = 105), while HER2+ and HR–/HER2– subtypes represented 17.2% (n = 23) and 4.5% (n = 6) of patients, respectively. The main metastatic sites at diagnosis were bone (63.1%; n = 94), lung (45.6%; n = 68), and lymph nodes (29.5%; n = 44) while brain and liver metastases were relatively rare. Metastatic disease occurred de novo in 49 (32.9%) patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of metastatic disease in men compared with women in the ESME database.

| Characteristics | Category | Men n = 149 (%) | Women n = 16,552 (%) | p value (2-sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | <50 years | 7 (4.7%) | 3784 (22.9%) | <0.0001 |

| (50–70 years) | 78 (52.3%) | 8544 (51.6%) | ||

| >70 years | 64 (43%) | 4224 (25.5%) | ||

| Mean age at diagnosis (SD) | 68.05 (11.23) | 60.57; SD = 13.77 | <0.0001 | |

| Median age at diagnosis (range) | 69 (44–90) | 61; 19–99 | ||

| HR/HER2 subtypes group | 0.0009 | |||

| Triple Negative | 6 (4.5%) | 2315 (15.5%) | 0.0005 | |

| HER2+ | 23 (17.2%) | 2840 (18.9%) | 0.62 | |

| HR+/HER2– | 105 (78.3%) | 9815 (65.6%) | 0.0019 | |

| Missing | 15 | 1582 | ||

| Pathological subtypes | IDC | 133 (95.7%) | 12404 (80.3%) | <0.0001 |

| ILC | 2 (1.4%) | 2185 (14.1%) | ||

| IDC + ILC | 1 (0.7%) | 258 (1.7%) | ||

| Other | 3 (2.2%) | 598 (3.9%) | ||

| Missing | 10 | 1107 | ||

| Tumor grade | Grade 1 | 10 (7.3%) | 1153 (7.9%) | 0.7836 |

| Grade 2 | 63 (46%) | 7082 (48.4%) | ||

| Grade 3 | 64 (46.7%) | 6407 (43.8%) | ||

| Missing | 12 | 1910 | ||

| ER status | Negative | 13 (8.8%) | 3731 (23.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Positive | 134 (91.2%) | 12303 (76.7%) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 518 | ||

| PR status | Negative | 45 (30.8%) | 6674 (43.1%) | 0.0029 |

| Positive | 101 (69.2%) | 8822 (56.9%) | ||

| Unknown | 3 | 1056 | ||

| HR status | Negative | 9 (6.1%) | 3442 (21.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Positive | 138 (93.9%) | 12609 (78.6%) | ||

| Unknown | 2 | 501 | ||

| HER2 status | Negative | 111 (82.8%) | 12194 (81.1%) | 0.6112 |

| Positive | 23 (17.2%) | 2840 (18.9%) | ||

| Unknown | 15 | 1518 | ||

| Location of metastases | Bone | 94 (63.1%) | 9418 (56.9%) | 0.1289 |

| Liver | 21 (14.1%) | 4470 (27%) | 0.0004 | |

| Lung | 68 (45.6%) | 4035 (24.4%) | <0.0001 | |

| Brain | 4 (2.7%) | 1196 (7.2%) | 0.0326 | |

| Lymph node | 44 (29.5%) | 4434 (26.8%) | 0.4520 | |

| Skin | 11 (7.4%) | 1823 (11%) | 0.1581 | |

| Other | 16 (10.7%) | 1711 (10.3%) | 0.8728 | |

| Visceral | 92 (61.7%) | 9579 (57.9%) | 0.3405 | |

| Non-Visceral | 57 (38.3%) | 6973 (42.1%) | 0.3405 | |

| Number of metastatic sites | <3 | 111 (74.5%) | 13230 (79.9%) | 0.0996 |

| ⩾3 | 38 (25.5%) | 3322 (20.1%) | ||

| Mean number of metastatic sites | 1.85 | 1.75 | 0.2184 | |

| Settings | De novo | 49 (32.9%) | 4754 (28.7%) | 0.2636 |

| Relapsing disease | 100 (67.1%) | 11798 (71.3%) | ||

| For relapsing disease | Men n = 100 (%) | Women n = 11,798 (%) | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (relapsing disease) | Yes | 62 (62%) | 8223 (70%) | 0.0830 |

| No | 38 (38%) | 3527 (30%) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 48 | ||

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy (relapsing disease) | Yes | 86 (86%) | 7809 (66.3%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 14 (14%) | 3975 (33.7%) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 14 | ||

| Time to relapse in months | (6–24) | 26 (26%) | 2159 (13.1%) | 0.081 |

| ⩾24 | 74 (74%) | 9634 (58.4%) |

ER, estrogen receptor; ESME, epidemiological strategy and medical economics; IDC, infiltrating ductal carcinoma; ILC, infiltrating lobular carcinoma; PR, progesterone receptor; SD, standard deviation.

Of the 100 patients previously treated for localized breast cancer, 62% (n = 62) had received adjuvant CT, 82% (n = 82) adjuvant RT, and 86% (n = 86) adjuvant ET. Median time to metastatic relapse from primary diagnosis was 52.5 months (8.9–331.4). Overall, genetic counseling was provided to only 23% of men (n = 34) and the results were not available in the database.

In the entire male population, CT was the main frontline treatment of metastatic disease (58.1%; n = 86) with 30.4% (n = 45) of patients receiving maintenance after CT. ET alone was given in 41.9% (n = 62) of patients, whereas 14 (9.5%) received frontline anti-HER2 therapy. Data were missing for one patient.

Main clinical and histological differences between men and women in the metastatic setting

Some striking differences were observed between the database’s male and female populations in this metastatic setting (Table 1). Men were older at diagnosis: median age 69 versus 61 years (p < 0.0001). HR+/HER2– disease was predominant in men compared with women (78.3 versus 65.6%; p = 0.001), whereas HER2+ disease frequency was similar (17.2% versus 18.9%; p = 0.061). Infiltrating ductal carcinoma was predominant in men whereas the lobular subtype was 10 times less frequent than in women (1.4% versus 14.1%; p < 0.0001). De novo metastatic disease occurred in the same proportion in men and women (32.9% versus 28.7%; p = 0.26). The location of metastatic sites was slightly different, with fewer brain metastases and liver lesions in men but more lung metastases.

Outcome of the entire male population compared with matched women

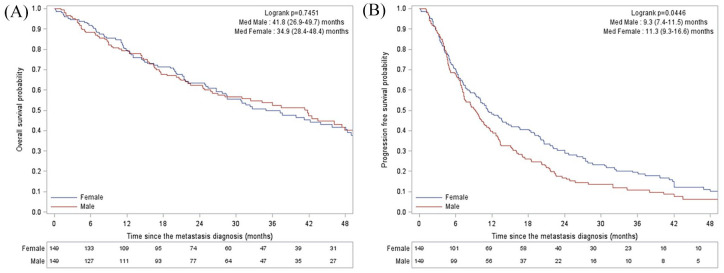

With median follow up of 41.9 months, the median OS of men was 41.8 months (95% CI, 26.9–49.7). Median PFS achieved by first-line therapy was 9.3 months (95% CI, 7.4–11.5) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

OS (A) and PFS (B) in men and in the matched cohort of women.

med, median; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Based on the aforementioned six-criteria matching procedure, the 149 men were matched with 149 women in the ESME database. Table 2 shows the characteristics of both cohorts. Tumor grade (III versus I/II) and number of metastatic sites (<3 versus ⩾3) were the only independent prognostic factors in the multivariate analysis (Supplemental Data).

Table 2.

Characteristics of metastatic disease in men and in a matched cohort of women.

| Characteristics | Category | Men n = 149 (%) | Women n = 149 (%) | p value (2-sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | <50 years | 7 (4.7%) | 7 (4.7%) | 1 |

| (50–70 years) | 78 (52.3%) | 78 (52.3%) | ||

| >70 years | 64 (43%) | 64 (43%) | ||

| Mean age at diagnosis (SD) | 68.05 (11.23) | 68.07 (11.28) | 0.9877 | |

| Performance status | PS 0 | 29 (37.7%) | 30 (36.6%) | 0.40 |

| PS 1 | 32 (41.6%) | 29 (34.5%) | ||

| PS 2 | 10 (13%) | 10 (12.2%) | ||

| PS 3 | 6 (7.8%) | 10 (12.2%) | ||

| PS 4 | 0 (0%) | 3 (3.7%) | ||

| Missing | 72 | 67 | ||

| HR/HER2 subtypes group | Triple Negative | 6 (4.5%) | 6 (4.5%) | 1 |

| HER2+ | 23 (17.2%) | 23 (17.2%) | ||

| HR+/HER2– | 105 (78.3%) | 105 (78.4%) | ||

| Missing | 15 | 15 | ||

| Pathological subtype | IDC | 133 (95.7%) | 108 (77.7%) | 0.0001 |

| ILC | 2 (1.4%) | 21 (15.1%) | ||

| IDC + ILC | 1 (0.7%) | 4 (2.9%) | ||

| Other | 3 (2.2%) | 6 (4.3%) | ||

| Missing | 10 | 10 | ||

| Tumor grade | Grade 1 | 10 (7.3%) | 10 (7.3%) | 1 |

| Grade 2 | 63 (46%) | 63 (46%) | ||

| Grade 3 | 64 (46.7%) | 64 (46.7%) | ||

| Missing | 12 | 12 | ||

| Location of metastases | Bone | 94 (63.1%) | 87 (58.4%) | 0.4063 |

| Liver | 21 (14.1%) | 38 (25.5%) | 0.0135 | |

| Lung | 68 (45.6%) | 37 (24.8%) | 0.0002 | |

| Brain | 4 (2.7%) | 4 (2.7%) | 1 | |

| Lymph node | 44 (29.5%) | 41 (27.5%) | 0.7003 | |

| Skin | 11 (7.4%) | 14 (9.4%) | 0.5307 | |

| Other | 16 (10.7%) | 21 (14.1%) | 0.3798 | |

| Visceral | 92 (61.7%) | 92 (61.7%) | 1 | |

| Non-Visceral | 57 (38.3%) | 57 (38.3%) | ||

| Number of metastatic sites | <3 | 111 (74.5%) | 117 (78.5%) | 0.4123 |

| ⩾3 | 38 (25.5%) | 32 (21.5%) | ||

| Mean number of metastatic sites | 1.85 | 1.75 | 0.4073 | |

| Settings | De novo | 49 (32.9%) | 49 (32.9%) | 1 |

| Relapsing disease | 100 (67.1%) | 100 (67.1%) | ||

| For relapsing disease | Men n = 100 (%) | Women n = 100 (%) | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (relapsing disease) | Yes | 62 (62%) | 66 (66%) | 0.0557 |

| No | 38 (38%) | 34 (34%) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | ||

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy (relapsing disease) | Yes | 86 (86%) | 86 (86%) | 1 |

| No | 14 (14%) | 14 (14%) | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | ||

| Time to relapse in months | (6–24) | 26 (26%) | 10 (10%) | 0.0131 |

| ⩾24 | 74 (74%) | 90 (90%) | ||

| Median time to relapse | 52.5 months | 81 months | 0.0002 |

HR, hormone receptor; IDC, infiltrating ductal carcinoma; ILC, infiltrating lobular carcinoma; SD, standard deviation.

OS appeared statistically similar in men and women: 41.8 months (95% CI, 26.9–49.7) versus 34.9 months (95% CI, 28.4–48.4) (p = 0.74), respectively. PFS achieved by first-line therapy was lower in men [9.3 months, 95% CI (7.4–11.5)] than in women [11.3 months, 95% CI (9.3–16.6)] (p = 0.0446) (Figure 1).

Management and outcome of the HR+/HER2– population

Given the predominance of HR+/HER2– disease (78.3%), we then focused on analyzing that population. The group’s main characteristics are shown in Table 3. Tumor grade (III versus I/II) was a strong prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis (Supplemental Data).

Table 3.

Characteristics of HR+/HER2– in men and matched women.

| Characteristics | Category | Men n = 105 (%) | Women n = 105 (%) | p-value (2-sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | <50 years | 4 (3.8%) | 4 (3.8%) | 1 |

| (50–70 years) | 61 (58.1%) | 61 (58.1%) | ||

| >70 years | 40 (38.1%) | 40 (38.1%) | ||

| Mean age at diagnosis (SD) | 66.60 (10.85) | 66.62 (10.84) | 0.9899 | |

| Performance status | PS 0 | 19 (34.6%) | 19 (32.8%) | 0.4045 |

| PS 1 | 24 (43.6%) | 24 (41.4%) | ||

| PS 2 | 9 (16.4%) | 7 (12.1%) | ||

| PS 3 | 3 (5.5%) | 5 (8.6%) | ||

| PS 4 | 0 (0%) | 3 (5.2%) | ||

| Missing | 50 | 47 | ||

| Location of metastases | Bone | 66 (62.9%) | 66 (62.9%) | 1 |

| Bone only | 28 (26.7%) | 30 (28.6%) | 0.7576 | |

| Liver | 14 (13.3%) | 25 (23.8%) | 0.0509 | |

| Lung | 46 (43.8%) | 24 (22.9%) | 0.0013 | |

| Brain | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 0.6508 | |

| Lymph node | 32 (30.5%) | 28 (26.7%) | 0.5412 | |

| Skin | 6 (5.7%) | 11 (10.5%) | 0.2059 | |

| Other | 13 (12.4%) | 15 (14.3%) | 0.6847 | |

| Visceral | 64 (61%) | 64 (61%) | 1 | |

| Non-Visceral | 41 (39%) | 41 (39%) | ||

| Number of metastatic sites | <3 | 77 (73.3%) | 83 (79%) | 0.3310 |

| ⩾3 | 28 (26.7%) | 22 (21%) | ||

| Mean number of metastatic sites | 1.88 | 1.77 | 0.4612 | |

| Settings | De novo | 31 (29.5%) | 31 (29.5%) | 1 |

| Relapsing disease | 74 (70.5%) | 74 (70.5%) | ||

| Time to relapse in months | (6–24) | 19 (18.1%) | 6 (5.7%) | 0.0171 |

| ⩾24 | 55 (52.4%) | 68 (64.8%) | ||

| Median time to relapse | 28 months | 51.2 months | 0.0027 |

HR, hormone receptor; PS, performance status; SD, standard deviation.

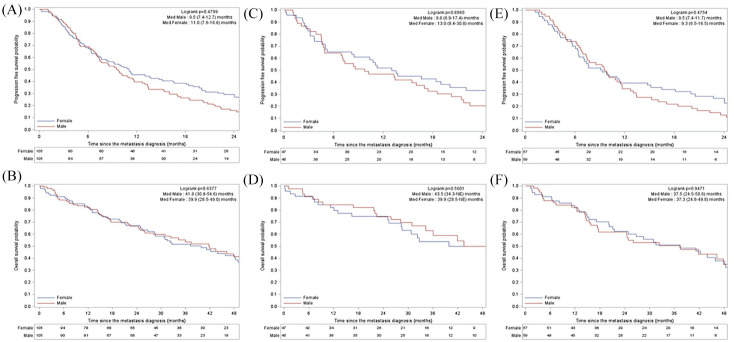

These patients had a median OS of 43.5 months (95% CI, 34.3–not estimated), which was similar to the OS of matched women (Figure 2A, B).

Figure 2.

PFS (A) and OS (B) in men with HR+/HER2– disease and in the matched cohort of women. PFS (C) and OS (D) in men with HR+/HER2– disease treated with first-line Et alone and in the matched cohort of women. PFS (E) and OS (F) in men with HR+/HER2– disease treated with first-line CT +/– ET maintenance and in the matched cohort of women.

CT, chemotherapy; ET, endocrine therapy; HR, hormone receptor; med, median; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

ET alone was the frontline treatment for 43% of patients. ET included antiestrogens (AE) (42.2%; n = 19), aromatase inhibitor (AI) alone (33.3%; n = 15) or in combination with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogs (6.7%; n = 3). Median PFS achieved with AE and AI alone was 8.5 months [95% CI (4.9–20.2)] and 6.9 months [95% CI (3.2–27.9)], respectively, while it was 17.4 months {95% CI [4.5–non-estimable (NE)]} for AI with LHRH analogs. However, the very low number of patients in each group prevent us from drawing any conclusions and these data should be considered with caution. The remaining eight patients (17.7%) received various sequential treatments after switching treatment without documented progression. The details of their treatment are shown in Table 4. Interestingly, median PFS achieved by frontline ET alone was statistically similar in men [9.8 months, 95% CI (6.9–17.4)] and in women [13 months, 95% CI (8.4–30.9)] (p = 0.80) (Figure 2C). Overall survival was similar in men and women receiving frontline ET alone (Figure 2D). Despite the low number of patients, PFS and OS seemed numerically similar for patients receiving frontline AE versus AI: 8.5 months (95% CI, 4.9–20.2) versus 6.9 months (95% CI, 3.2–27.9) (p = 0.37) and 41.9 months (95% CI, 27.1–NE) versus 43.5 months (95% CI, 34.3–74.9) (p = 0.8), respectively. A high proportion of patients received frontline CT (56.7%; n = 59), associated in 50.8% (n = 30) of patients with maintenance ET. Median PFS achieved with CT was 9.5 months (95% CI, 7.4–11.7) and OS was 37.5 months (95% CI, 24.5–50.6). This was statistically similar to the matched cohort of women (Figure 2E, F). Interestingly, PFS was statistically similar for HR+/HER2– patients who received upfront ET or CT: 9.8 months (95% CI; 6.9–17.4) versus 9.5 months (95% CI; 7.4–11.7) (p = 0.22) respectively.

Table 4.

Type of ET administered in the male HR+/HER2– population.

| Drug | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| AE (Tamoxifen, Fulvestrant) | 19 | 42.2 |

| AI alone | 15 | 33.3 |

| AI with LHRH analogs | 3 | 6.7 |

| Other (sequential treatments without documented progression) | 8 | 17.7 |

| Total | 45 | 100 |

(+) represents sequential treatment without documented progression.

AE, antiestrogen; AI, aromatase inhibitors; ET, endocrine therapy; HR, hormone receptor; LHRH, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone.

Discussion

In this large comprehensive cohort of real-life patients, our study shows that breast cancer in men and women globally has the same prognosis in the metastatic setting, despite clinical and pathological differences. Given the scarcity of data on males in the metastatic setting, our findings add valuable information on this rare disease.

The specific features of metastatic male breast cancer have already been reported in previous publications. The SEER reported on a series of 394 metastatic men, showing the predominance of HR+ disease in the metastatic setting.4 However, despite the impressive data collection, some important information was lacking, such as HER2 status and patient management. Foerster and colleagues have published the most comprehensive study on metastatic breast cancer in 41 men in Saxony between 1995 and 2011. The characteristics of that population were similar to ours in terms of median age, subgroup distribution and de novo metastatic disease distribution.11 Moreover, metastatic site distribution was consistent with the predominance of bone and lung disease (56.1% and 51.2%, respectively), whereas liver and brain metastasis were infrequent. Intriguingly, a recent analysis of 196 metastatic male BC cases confirms this specific pattern of metastasis distribution compared with women with no clear explanation.12 Recently, an international program has been launched to improve male breast cancer characterization. This three-part program includes the retrospective collection of clinical information and male breast cancer tumor tissue over 20 years, a prospective register of newly diagnosed cases over a 30-month period, and prospective clinical studies to optimize these patients’ management.13 The retrospective part of the program enrolled 1483 male patients with all stages diagnosed between 1990 and 2010, including 57 with metastatic disease. Vermeulen et al. reported on the predominance of invasive ductal carcinoma in men (86.6%) and the low prevalence of the lobular subtype (1.4%) as in our study (95.7% and 1.4%, respectively).14 In that study, Luminal A or Luminal B with HER2-negative profile was massively predominant, representing 91.2% of cases. Of note, no specific data were reported on the metastatic population.

The decision-making process for males with metastatic BC is extrapolated mainly from female-specific guidelines. Indeed, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines state that men with HR+/HER2– BC should be treated similarly to postmenopausal women, except that the use of aromatase inhibitors is ineffective without concomitant suppression of testicular steroidogenesis.3 The ABC 4 recommendations (4th ESO–ESMO International Consensus Guidelines for Advanced Breast Cancer) state that ET is the preferred option, unless there is concern or proof of endocrine resistance or rapidly progressive disease needing a fast response.2 Our study shows that only 43% of men with HR+/HER2– disease receive ET alone as initial treatment. This rate is lower than reported for women and not explained by the presence of visceral crisis reflecting the pattern distribution of metastases.12 The assumption that the ET given to women is less effective in men is a possible explanation as no prospective randomized data evaluating tamoxifen in metastatic male BC have been reported. However, we show that the median PFS achieved by frontline ET alone is similar in men and women. In addition, ET and CT achieved statistically similar PFS in these patients. Therefore, the use of ET in men with HR+/HER2– metastatic breast cancer should be encouraged even in the presence of visceral metastases and absence of visceral crisis. These data are supported by the recent approval of palbociclib in combination with AI or fulvestrant in men based on real-world data.15,16 Similarly, alpelisib is approved in men in combination with fulvestrant for HR+/HER2– PIK3CA mutant tumors, which appear less frequent than in women.17,18

Surprisingly, around one-third of patients received AI without LHRH analogs. According to ABC guidelines, Tamoxifen is the preferred option. If AI is necessary, a concomitant LHRH agonist or orchiectomy is the preferred option. Differences in estrogen production in men and women are raising concerns over the efficacy of AI monotherapy in males. AI suppress the main source of estrogen in men but do not affect the testicular production, leading to a theoretical feedback loop increasing the level of testosterone, which is an aromatase enzyme substrate.19,20 There are very few clinical data on the efficacy of AI +/– GnRH or LHRH analogues in metastatic male BC, with retrospective series including a maximum of 60 patients.7,21–24 SWOG-S0511 [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00217659] – a phase II trial designed to evaluate the efficacy of anastrozole plus goserelin in male metastatic breast cancer – closed prematurely due to poor accrual. The Male-GBG54 study is the first prospective, randomized, multicenter trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of different endocrine treatment options in male BC patients. Patients were randomized to receive tamoxifen, tamoxifen + GnRHa subcutaneous (s.c.) q3m and exemestane + GnRHa s.c. for 6 months as neo/adjuvant or metastatic therapy.25 The primary objective was estradiol (E2) suppression after 3 months. The analysis revealed increased E2 levels along the course of therapy after an initial steep decrease when GnRHa was given. Our study shows that the recommendations are not always followed. Notably, Tamoxifen is not always a practitioners’ first choice and the concomitant administration of LHRH analogues with AI is not systematic. Comorbidities, quality of life and toxicity profile might play a role, but those data were not gathered. A recent prospective cohort analysis showed a marked risk of thromboembolism events in male breast cancer patients receiving tamoxifen, up to 11.9%.26

The ESME-MBC program reports centralized, high-quality, and exhaustive real-life data with a clinical trial-like methodology, representing a very large-scale ongoing multicenter cohort with more than 24,000 MBC cases to date. It involves 18 French Comprehensive Cancer Centers managing over a third of all MBC cases in France, giving a reliable view of this single entity in a real-life setting. We should acknowledge that this study’s limitations are its retrospective and observational nature due to the real-life setting. In addition, important information like the results of genetic counseling were not available. Generating prospective data on male metastatic breast cancer is very challenging, as shown by the difficulty of conducting clinical trials in that population. In addition, men are frequently excluded from breast cancer trials, as shown by a recent report; between 2000 and 2017, of 426 trials retrieved in breast cancer, 65% excluded males.27 Overall, 0.42% of participants were male, with the lowest enrolment rates in hormonal and targeted therapy trials (0.1% and 0.1%, respectively). This paradigm should shift in the future given the FDA call to include men in BC trials.

Conclusion

MBC in men is a rare disease and represents an unmet need. Despite some biological discrepancies, the management of MBC in men leads to similar outcomes as in women, especially in the HR+/HER2– patients who represent almost 80% of cases. ET alone or in combination should be the cornerstone of HR+ management and existing guidelines should be distributed more widely. Some important questions remain unanswered and successful randomized trials are eagerly awaited to increase the level of evidence and knowledge of that specific population.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-tam-10.1177_1758835920980548 for Management and outcome of male metastatic breast cancer in the national multicenter observational research program Epidemiological Strategy and Medical Economics (ESME) by Junien Sirieix, Julien Fraisse, Simone Mathoulin-Pelissier, Marianne Leheurteur, Laurence Vanlemmens, Christelle Jouannaud, Véronique Diéras, Christelle Lévy, Mony Ung, Marie-Ange Mouret-Reynier, Thierry Petit, Bruno Coudert, Etienne Brain, Barbara Pistilli, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Anthony Goncalves, Lionel Uwer, Anne Patsouris, Olivier Tredan, Coralie Courtinard, Sophie Gourgou and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Acknowledgments

We thank the 18 French Comprehensive Cancer Centers for providing the data and each ESME local coordinator for managing the project at local level. Moreover, we thank the ESME Scientific Committee members for their ongoing support. Participating French Comprehensive Cancer Centers (FCCC): I. Curie, Paris/Saint-Cloud; G. Roussy, Villejuif; I. Cancérologie de l’Ouest, Angers/Nantes; C. F. Baclesse, Caen; ICM Montpellier; C. L. Bérard, Lyon; C. G-F Leclerc, Dijon; C. H. Becquerel, Rouen; I. C. Regaud, Toulouse; C. A. Lacassagne, Nice; Institut de Cancérologie de Lorraine, Nancy; C. E. Marquis, Rennes; I. Paoli-Calmettes, Marseille; C. J. Perrin, Clermont Ferrand; I. Bergonié, Bordeaux; C. P. Strauss, Strasbourg; I. J. Godinot, Reims; C. O. Lambret, Lille.

Footnotes

Author contributions: ESME central coordinating staff: Head of Research and Development: Claire Labreveux.

Program director: Mathieu Robain.

Data Management team: Coralie Courtinard, Emilie Nguyen, Olivier Payen, Irwin Piot, Dominique Schwob, and Olivier Villacroux.

Operational team: Michaël Chevrot, Daniel Couch, Patricia D’Agostino, Pascale Danglot, Cécilie Dufour, Tahar Guesmia, Christine Hamonou, Gaëtane Simon, and Julie Tort.

Supporting clinical research associates: Elodie Kupfer and Toihiri Said.

Project Associate: Nathalie Bouyer.

Management assistant: Esméralda Pereira.

Software designers: Matou Diop, Blaise Fulpin, José Paredes, and Alexandre Vanni.

ESME local coordinators:

Patrick Arveux, Thomas Bachelot, Stéphanie Delaine, Delphine Berchery, Etienne Brain, Mathias Breton, Loïc Campion, Emmanuel Chamorey, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Valérie Dejean, Anne-Valérie Guizard, Anne Jaffré, Lilian Laborde, Carine Laurent, Agnès Loeb, Muriel Mons, Damien Parent, Geneviève Perrocheau, Marie-Ange Mouret-Reynier, and Michel Velten.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by R&D UNICANCER. The ESME-MBC database is supported by an industrial consortium (Roche, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, MSD, Eisai and Daiichi Sankyo). Data collection, analysis and publication are fully managed by R&D UNICANCER independently of the industrial consortium.

ORCID iDs: Etienne Brain  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0881-9371

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0881-9371

Jean-Sébastien Frénel  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5273-0561

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5273-0561

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Junien Sirieix, Department of Medical Oncology, ICO Institut de Cancerologie de l’Ouest – René Gauducheau, Saint-Herblain, France.

Julien Fraisse, Biometrics Unit, ICM Regional Cancer Institute of Montpellier, Montpellier, France.

Simone Mathoulin-Pelissier, Bordeaux University, Inserm CIC1401 and Clinical and Epidemiological Research Unit, Institut Bergonie, Bordeaux, France.

Marianne Leheurteur, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Henri Becquerel, Rouen, France.

Laurence Vanlemmens, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille, France.

Christelle Jouannaud, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Jean Godinot, Reims, France.

Véronique Diéras, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Eugene Marquis, Rennes, France.

Christelle Lévy, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Francois Baclesse, Caen, France.

Mony Ung, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Claudius Regaud, Toulouse, France.

Marie-Ange Mouret-Reynier, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Jean Perrin, Clermont-Ferrand, France.

Thierry Petit, Department of Medical Oncology, GINECO & Paul Strauss Cancer Center and University of Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France.

Bruno Coudert, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Georges-François Leclerc, Dijon, France.

Etienne Brain, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Curie, Paris & Saint-Cloud, France.

Barbara Pistilli, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France.

Jean-Marc Ferrero, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice, France.

Anthony Goncalves, Department of Medical Oncology, Institute Paoli-Calmettes, Marseille, France.

Lionel Uwer, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut de Cancérologie de Lorraine – Alexis Vautrin, Vandoeuvre-Lès-Nancy, France.

Anne Patsouris, Department of Medical Oncology, ICO Institut de Cancerologie de l’Ouest – Paul Papin, Angers, France.

Olivier Tredan, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon, France.

Coralie Courtinard, R&D, Unicancer, Paris, France.

Sophie Gourgou, Biometrics Unit, ICM Regional Cancer Institute of Montpellier, Montpellier, France.

Jean-Sébastien Frénel, Department of Medical Oncology, ICO Institut de Cancerologie de l’Ouest – René Gauducheau, Saint-Herblain, France.

References

- 1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2019. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cardoso F, Senkus E, Costa A, et al. 4th ESO–ESMO international consensus guidelines for Advanced Breast Cancer (ABC 4). Ann Oncol 2018; 29: 1634–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gradishar WJ, Comprehensive RHL, Forero A, et al. NCCN guidelines index table of contents discussion. Breast Cancer 2018; 209: BINV-18. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen W, Huang Y, Lewis GD, et al. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors in male patients with stage IV breast cancer: a population-based study. Clin Breast Cancer. Epub ahead of print 9 August 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bradley KL, Tyldesley S, Speers CH, et al. Contemporary systemic therapy for male breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2014; 14: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Lauro L, Pizzuti L, Barba M, et al. Efficacy of chemotherapy in metastatic male breast cancer patients: a retrospective study. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015; 34: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Lauro L, Pizzuti L, Barba M, et al. Role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues in metastatic male breast cancer: results from a pooled analysis. J Hematol Oncol 2015; 8: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu S-G, Zhang W-W, Liao X-L, et al. Men and women show similar survival outcome in stage IV breast cancer. Breast 2017; 34: 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Male breast cancer: developing drugs for treatment, http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/male-breast-cancer-developing-drugs-treatment (2019, accessed 3 February 2020).

- 10. Public Policy Committee and International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology. Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practice (GPP). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016; 25: 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Foerster R, Schroeder L, Foerster F, et al. Metastatic male breast cancer: a retrospective cohort analysis. Breast Care 2014; 9: 267–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xie J, Ying Y-Y, Xu B, et al. Metastasis pattern and prognosis of male breast cancer patients in US: a population-based study from SEER database. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2019; 11: 175883591988900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cardoso F, Bartlett JMS, Slaets L, et al. Characterization of male breast cancer: results of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG international male breast cancer program. Ann Oncol. Epub ahead of print 28 October 2017. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdx651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vermeulen MA, Slaets L, Cardoso F, et al. Pathological characterisation of male breast cancer: results of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG international male breast cancer program. Eur J Cancer 2017; 82: 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wedam S, Fashoyin-Aje L, Bloomquist E, et al. FDA approval summary: palbociclib for male patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. Epub ahead of print 24 October 2019. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartlett CH, Mardekian J, Yu-Kite M, et al. Real-world evidence of male breast cancer (BC) patients treated with palbociclib (PAL) in combination with endocrine therapy (ET). J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 1055. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piscuoglio S, Ng CKY, Murray MP, et al. The genomic landscape of male breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22: 4045–4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deb S, Wong SQ, Li J, et al. Mutational profiling of familial male breast cancers reveals similarities with luminal A female breast cancer with rare TP53 mutations. Br J Cancer 2014; 111: 2351–2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hemsell DL, Grodin JM, Brenner PF, et al. Plasma precursors of estrogen. II. Correlation of the extent of conversion of plasma androstenedione to estrone with age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1974; 38: 476–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mauras N, O’brien KO, Klein KO, et al. Estrogen suppression in males: metabolic effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85: 2370–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Giordano SH, Valero V, Buzdar AU, et al. Efficacy of anastrozole in male breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2002; 25: 235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doyen J, Italiano A, Largillier R, et al. Aromatase inhibition in male breast cancer patients: biological and clinical implications. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 1243–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Koutoulidis V, et al. Aromatase inhibitors with or without gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue in metastatic male breast cancer: a case series. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 2259–2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vici P, Del Medico P, Laudadio L, et al. Letrozole combined with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for metastatic male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 141: 119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reinisch M, Seiler S, Hauzenberger T, et al. Final analysis of the Male-GBG54 study: a prospective, randomised multi-centre phase II study evaluating endocrine treatment with either tamoxifen +/– gonadotropin releasing hormone analogue (GnRHa) or an aromatase inhibitor + GnRHa in male breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. Epub ahead of print 1 October 2018. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdy424.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eggemann H, Bernreiter A-L, Reinisch M, et al. Tamoxifen treatment for male breast cancer and risk of thromboembolism: prospective cohort analysis. Br J Cancer 2019; 120: 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duma N, Hoversten KP, Ruddy KJ. Exclusion of male patients in breast cancer clinical trials. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2018; 2: pky018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-tam-10.1177_1758835920980548 for Management and outcome of male metastatic breast cancer in the national multicenter observational research program Epidemiological Strategy and Medical Economics (ESME) by Junien Sirieix, Julien Fraisse, Simone Mathoulin-Pelissier, Marianne Leheurteur, Laurence Vanlemmens, Christelle Jouannaud, Véronique Diéras, Christelle Lévy, Mony Ung, Marie-Ange Mouret-Reynier, Thierry Petit, Bruno Coudert, Etienne Brain, Barbara Pistilli, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Anthony Goncalves, Lionel Uwer, Anne Patsouris, Olivier Tredan, Coralie Courtinard, Sophie Gourgou and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology