Abstract

The glomerular filtration barrier is a highly specialized capillary wall comprising fenestrated endothelial cells, podocytes, and an intervening basement membrane. In glomerular disease, this barrier loses functional integrity, allowing the passage of macromolecules and cells, and there are associated changes in both cell morphology and the extracellular matrix. Over the past 3 decades, there has been a transformation in our understanding about glomerular disease, fueled by genetic discovery, and this is leading to exciting advances in our knowledge about glomerular biology and pathophysiology. In current clinical practice, a genetic diagnosis already has important implications for management, ranging from estimating the risk of disease recurrence post-transplant to the life-changing advances in the treatment of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Improving our understanding about the mechanistic basis of glomerular disease is required for more effective and personalized therapy options. In this review, we describe genotype and phenotype correlations for genetic disorders of the glomerular filtration barrier, with a particular emphasis on how these gene defects cluster by both their ontology and patterns of glomerular pathology.

Keywords: glomerular filtration barrier, glomerular basement membrane, podocyte, endothelium, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, Kidney Genomics Series

Introduction

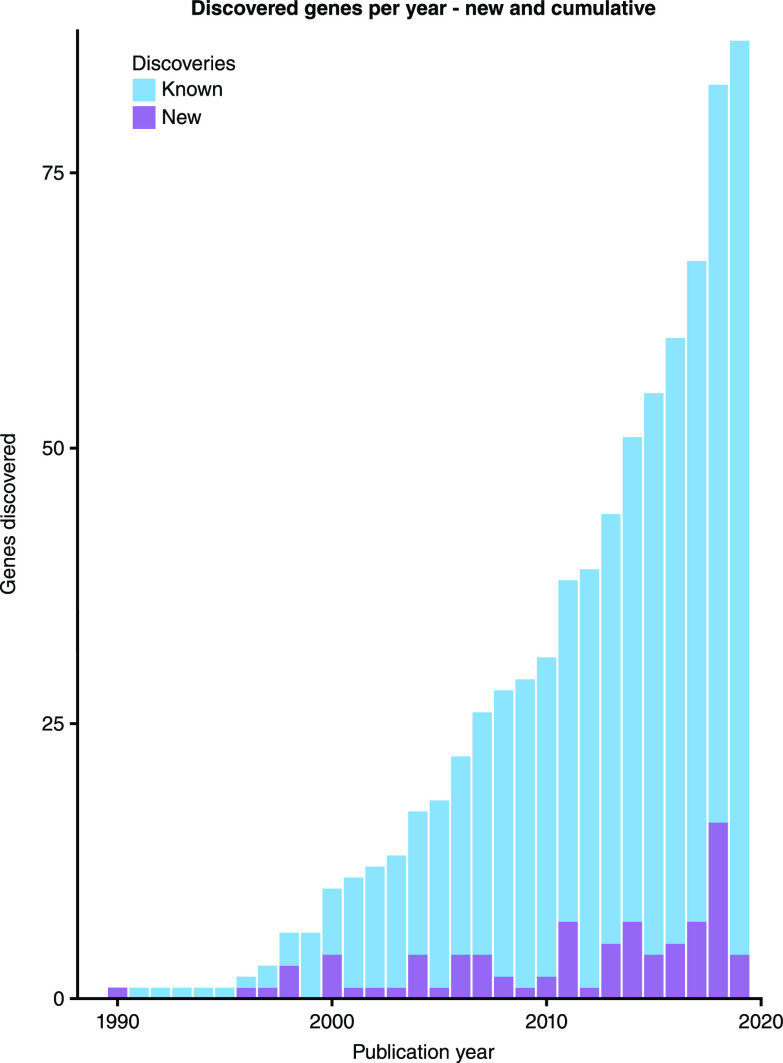

Defects in >80 genes have been found to cause disorders of the glomerular filtration barrier, with a rapid rise in gene discovery over the last 10 years (Figure 1). This list continues to expand with the use of next-generation sequencing in large cohorts of patients who have been deeply phenotyped (1–4). Whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing allows rapid screening for both pathogenic and novel variants in affected individuals and their families who lack a genetic diagnosis (5). Furthermore, advances in cell-specific genetic engineering techniques such as Cre-lox recombination (6) and more recent genome-editing approaches with CRISPR-Cas9 (7) have enabled focused in vivo and in vitro modeling of gene function. These approaches can elicit mechanistic details about genetic variants and cellular physiology to establish a causal link from gene to clinical phenotype (8). Using this pipeline from gene discovery to experimental modeling, our understanding of the glomerular filtration barrier in health and disease has been transformed. This review focuses on known human genetic disorders of the filtration barrier by considering the key component parts: podocytes, endothelial cells, and the glomerular basement membrane.

Figure 1.

The rapid rise in gene discovery. The number of new gene discoveries is shown together with the cumulative total. There is rapid rise in discoveries in the last 10 years, from 29 genes in 2009 to 87 in 2019.

The Glomerular Filtration Barrier

The filtration barrier comprises three layers: podocytes and endothelial cells with an intervening glomerular basement membrane (GBM). Together, this specialized capillary wall allows selective ultrafiltration while retaining circulating cells and plasma proteins. The barrier is both size selective and charge selective, as demonstrated by early studies of transferrin accumulation (9). Glomerular endothelial cells have fenestrae that are 70–100 nm in diameter and covered by an endothelial surface layer consisting largely of glycocalyx that contributes to the charge-selective barrier (10). The GBM is a unique basement membrane formed by secreted products from both endothelial cells and podocytes during glomerulogenesis (11). It is a complex gel-like structure consisting of core basement membrane components, including laminin isoforms, type IV collagen, nidogen, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans, in addition to many more less abundant structural and regulatory components (12). Podocytes are specialized epithelial cells covering the outer aspect of the glomerular capillary. These cells are basally anchored to the GBM through transmembrane receptors such as integrins and dystroglycans (10) and specialized cell-cell junctions known as slit diaphragms interconnect podocytes laterally (10). Podocyte foot processes have an actin-based cytoskeleton connecting basal, lateral, and apical domains via linker proteins to both cell-cell and cell-matrix junctions and thereby convey cues from the extracellular environment (10).

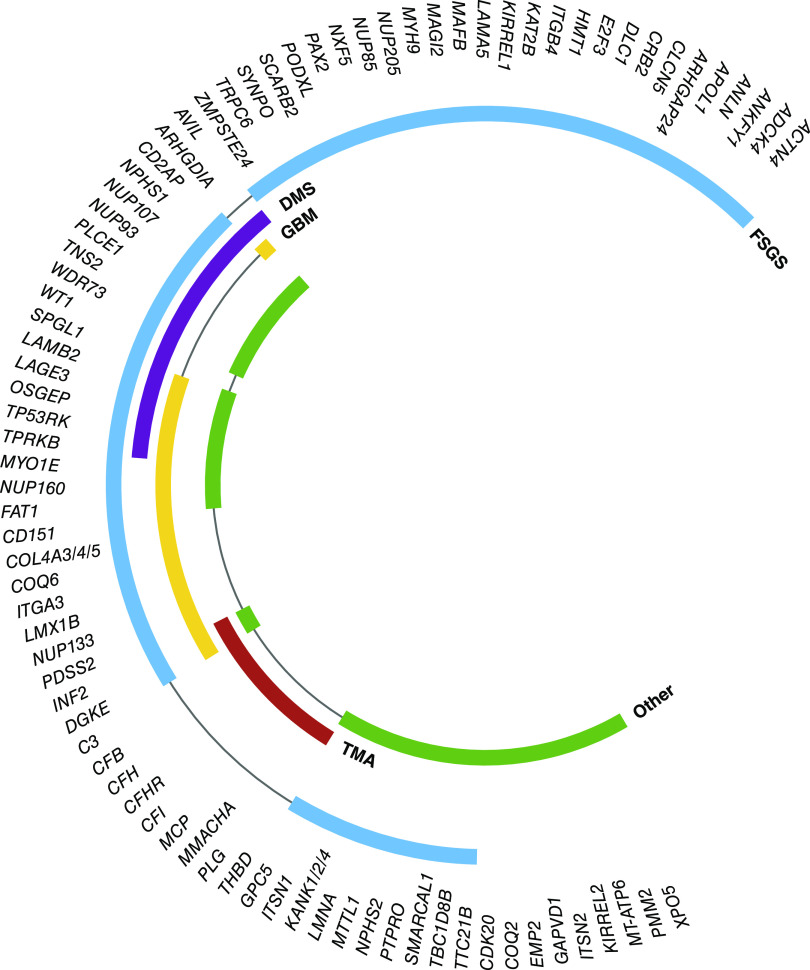

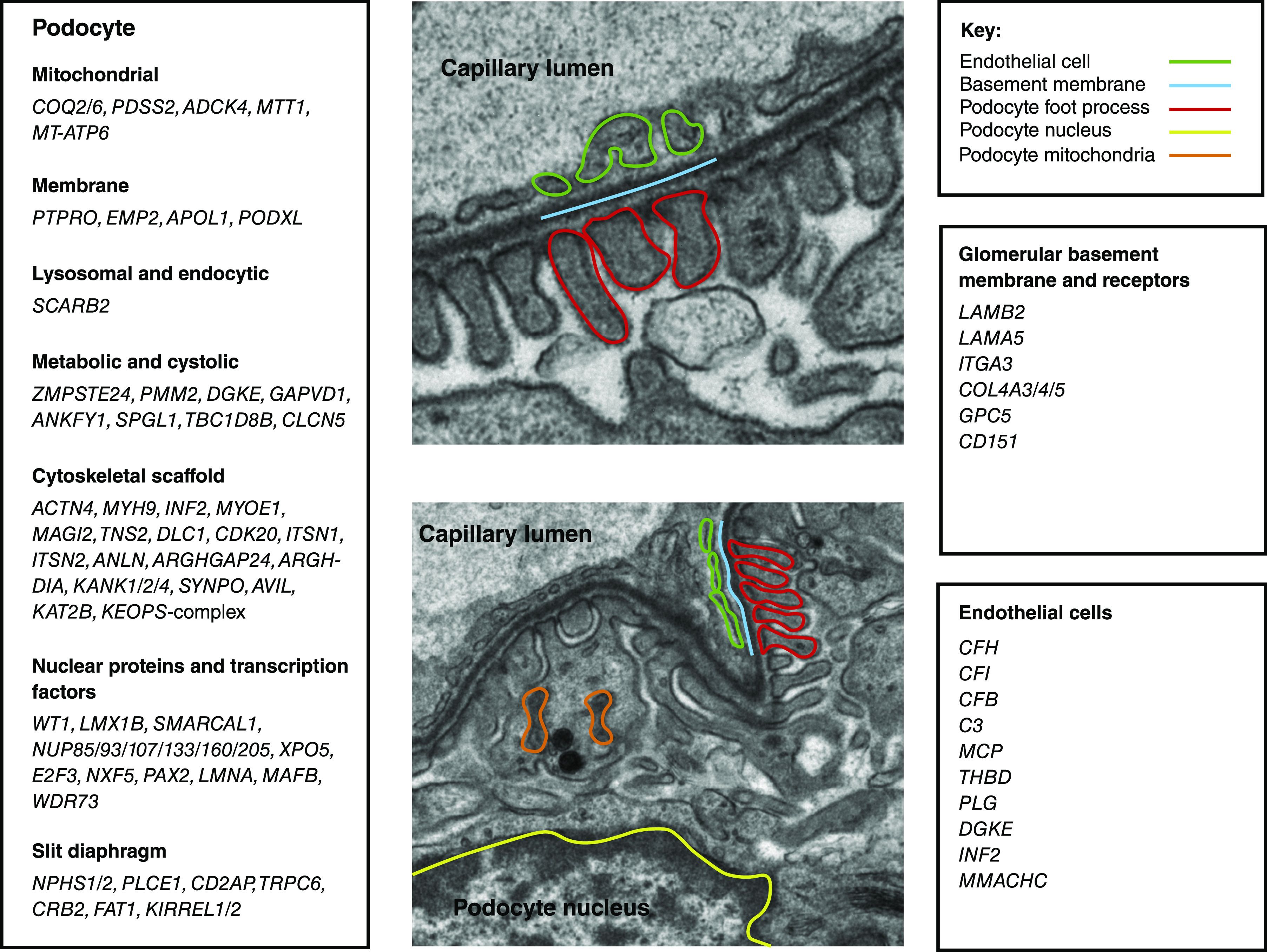

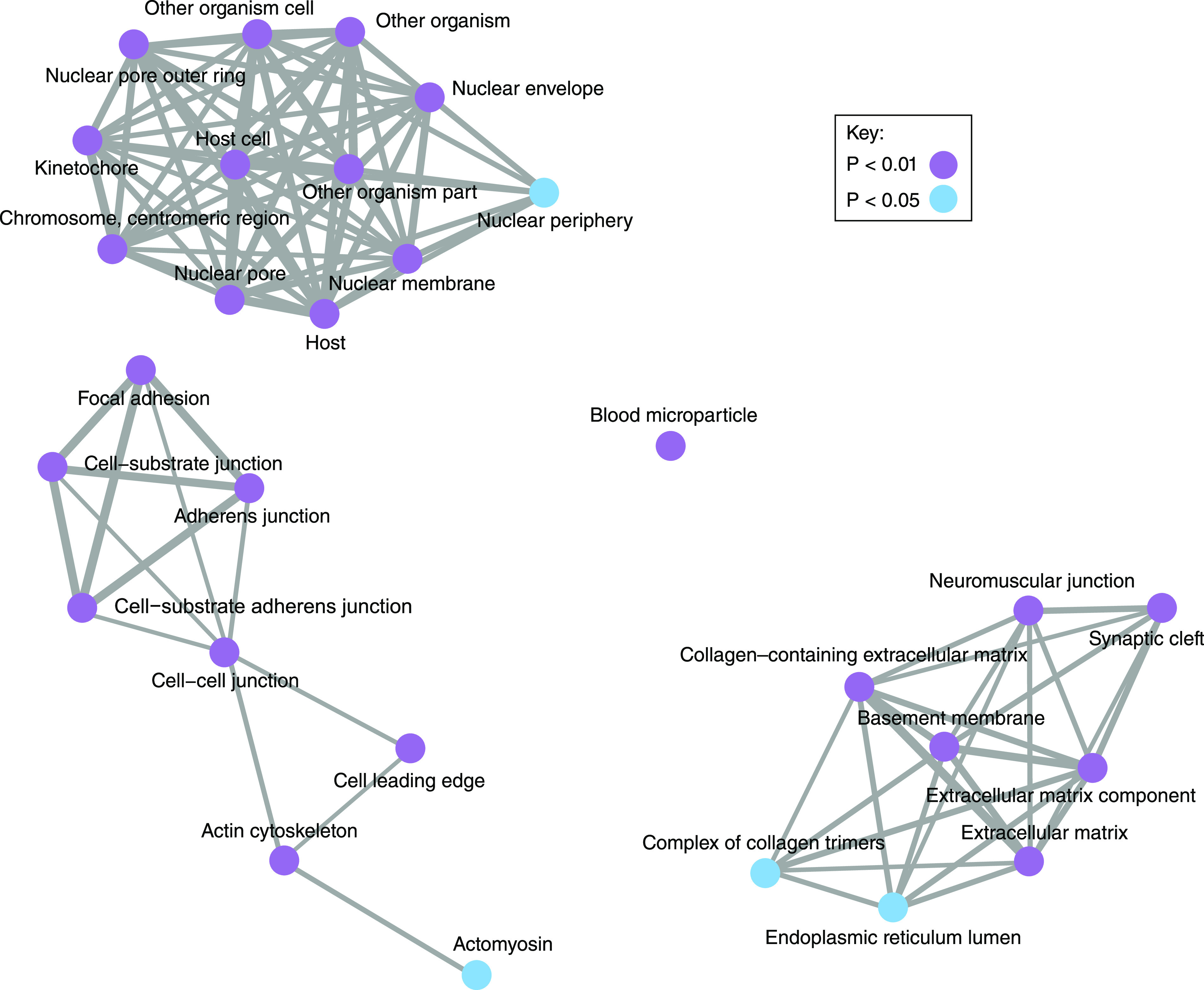

Pathogenic variants in a wide range of genes with functional relevance in glomerular filtration have been identified to date. As a high-level starting point, these genes can be classified according to their location within the three-layered filtration barrier (Figure 2). An alternative representation is demonstrated with enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology cellular compartment annotations for known genes (Figure 3). This analysis demonstrates the importance of the cellular cytoskeleton, cell-cell junctions, and extracellular matrix in genetic disorders of the filtration barrier. In the following sections, we demonstrate how genetic discovery has highlighted particular cellular components and biologic pathways and helped to build understanding about glomerular biology and pathophysiology.

Figure 2.

Disease-causing genes can be categorized by cellular localization. Electron microscopy from the kidney of an 8-week-old BL6/C57 mouse. The glomerular filtration barrier is shown with annotation. The genes known to cause glomerular filtration barrier dysfunction are listed and categorized by localization.

Figure 3.

Disease-causing genes are connected in their biological roles. A Gene Ontology enrichment analysis was performed for the 87 genes described in this review. We used clusterProfiler (59), which is an open-source tool useful for highlighting the predominant biologic roles in a collection of genes, and we selected the cellular compartment ontology. This highlights the importance of the podocyte, extracellular matrix, and nucleus.

Podocyte Genetics

Inherited podocyte dysfunction typically manifests as nephrotic syndrome, characterized by the clinical triad of massive proteinuria, albumin <25 g/L, and edema. Many genetic causes of nephrotic syndrome are resistant to treatment with glucocorticoids, leading to the classification of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. The prognosis for patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome is poor, and they invariably progress to kidney failure. Although kidney biopsy remains an important clinical tool for the histologic diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome, the availability of genetic testing has enabled a further layer of classification. Overall, the most frequent histologic pattern observed in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome is FSGS, whereas in early-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, diffuse mesangial sclerosis is a frequent finding. However, there is significant overlap between histopathology and ultrastructural patterns associated with pathogenic variants causing glomerular disease (Figure 4). These findings demonstrate the precision of genetic testing compared with kidney biopsies for reaching a diagnosis but also indicate that a range of genetic defects will potentially share similar mechanisms of injury. The discovery of pathogenic variants causing steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome provides important insights into the role of these genes in normal glomerular function. They also reaffirm the essential role of the podocyte in the function of the filtration barrier with the majority of genes implicated in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome localizing to the podocyte.

Figure 4.

Genetic mutations are associated with multiple patterns of glomerular pathology. In a quarter of genes encoding cellular compartment proteins, mutations result in glomerular basement membrane (GBM) defects as well as FSGS and/or diffuse mesangial sclerosis (DMS). Mutations in two genes, INF2 and DGKE, are associated with FSGS, GBM defects, and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Many gene mutations also result in other pathologic patterns such as minimal change disease, collapsing glomerulopathy, membranoproliferative GN, mesangial proliferation, and tubular dilation.

Slit Diaphragm–Related Genes

NPHS1 encodes nephrin, a transmembrane protein and a core component of the slit diaphragm. Between adjacent foot processes, nephrin molecules form homo- and heterodimers with its homolog Neph1 forming the slit diaphragm in a zipper-like pattern. Intracellularly, nephrin phosphorylation by the tyrosine kinase Fyn leads to enhanced PI3K/Akt/Rac pathway activation, promoting dynamic modeling of actin cytoskeleton. Nephrin interacts with podocin (encoded by NPHS2), an integral membrane protein, and CD2-associated protein (encoded by CD2AP), an adapter protein connecting nephrin to the actin cytoskeleton as well as interacting with the PI3K/Akt pathway. Nephrin also interacts with IQ motif–containing GTPase-activating protein 1 (IQGAP1), which in turn interacts with phospholipase Cε1 (encoded by PLCE1), a phospholipase generating downstream messengers such as inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. NPHS1 was identified as the pathogenic gene in congenital nephrotic syndrome of the Finnish type (13). Disease-causing homozygous NPHS1 variants are common in Finland, affecting approximately 1 in 10,000 children. Two truncating variants (Fin-major and Fin-minor) account for >94% of Finnish cases, demonstrating a founder effect. Outside Finland, classic NPHS1 variants are rare. Missense variants are associated with a milder FSGS phenotype (14). Homozygous variants in NPHS2 and PLCE1 causing steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome display genotype-phenotype correlation. Different NPHS2 variants can cause steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome with variant-specific disease severity and onset from early childhood to early adulthood. Truncating variants in PLCE1 cause early onset of proteinuria and progression to kidney failure, whereas missense variants are found in later-onset nephrotic syndrome and cause slower progression. Some individuals with PLCE1 variants were responsive to corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapy. Recently, defects in proteins encoded by KIRREL1 and KIRREL2, members of the NEPH family that interact with podocin, have also been found in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (15,16).

Enhanced calcium influx appears to be a key factor for mediating podocyte injury and is associated with monogenic causes of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Transient receptor potential channel C6 (encoded by TRPC6) is a slit diaphragm–associated calcium channel and mechanical stretch sensor. A heterozygous gain-of-function variant enhances TRPC6-mediated calcium signal amplitude amplification, resulting in prolonged channel activation. TRPC6 is also associated with angiotensin II–mediated calcium influx and apoptosis, leading to podocyte loss (17). Variants in other genes such as NPHS2, ACTN4, and APOL1 also result in calcium overload and podocyte injury, possibly via TRPC6 hyperactivity (18).

Podocalyxin is a transmembrane sialoglycoprotein localized to the podocyte apical surface and acts as an antiadhesin that maintains the opening of the slit diaphragm through charge repulsion. Autosomal dominant variants in podocalyxin, encoded by PODXL, cause adolescence- to adult-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome with incomplete disease penetrance (19). PTPRO encodes a tyrosine phosphatase expressed at the apical membrane of the foot processes. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the slit diaphragm components nephrin and ZO-1 alters their association with other slit diaphragm proteins. Notably, patients harboring PTPRO variants showed partial response to corticosteroid and cyclosporin combination therapy (20).

Cytoskeletal Genes

Podocyte cells are highly differentiated and polarized. Their architecture and morphology is integral to function as part of the glomerular filtration barrier. Healthy podocytes have an arborized shape characterized by multiple branching projections forming the foot processes (21). A hallmark feature of nephrotic syndrome is the loss of podocyte arborization and foot-process effacement, and this is associated with significant cytoskeletal remodeling. The slit diaphragm complex is inextricably connected to the highly dynamic actin cytoskeleton, transducing signals to affect and coordinate podocyte structure and function. Variants in a number of genes encoding modulators and components of the actin cytoskeleton have been identified as the causes of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Myosin 1E, encoded by MYO1E, is an actin-based molecular motor and a key component of the podocyte cytoskeleton that interacts with the slit diaphragm complex. Podocytes expressing defective MYO1E could not efficiently assemble actin cables along new cell-cell junctions (22). α-Actinin-4 is an actin-filament crosslinking protein encoded by ACTN4. Pathogenic variants in its actin-binding domain increase its binding affinity, resulting in a stiffened and more brittle actin network and making the podocyte vulnerable to detachment under environmental mechanical stress (23). Inverted formin 2, encoded by INF2, nucleates actin filaments and promotes actin elongation, as well as accelerating F-actin depolymerization and filament severing. Variants in INF2 lead to aberrant regulation of actin turnover and restructuring. INF2 also binds to and is regulated by the Rho GTPase Cdc42. The Rho family GTPases RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 signaling pathways are implicated in the pathogenesis of other monogenic variants causing steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Under the stress response, podocytes switch from a RhoA-dependent stationary state to a Cdc42- and Rac1-dependent migratory state. Rho GTPase–activating protein 24, encoded by ARHGAP24, activates RhoA, leading to downstream suppression of lamellipodia formation and cell spreading. This function is impaired in autosomal dominant ARHGAP24 variants because both wild-type and mutated proteins homodimerize and heterodimerize (24). In patients with homozygous ARHGDIA variants, the defective encoded protein Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor α fails to interact with Rac1 and Cdc42, resulting in increased GDP-bound Rac1 and Cdc42 activity. KANK 1/2/4 genes encoding kidney ankyrin repeat-containing proteins also harbor pathogenic variants (25). KANK2 interacts with ARHGDIA, whereas KANK1 colocalizes with synaptopodin encoded by SYNPO. Synaptopodin is a podocyte-specific, actin-binding protein and is antagonized by TRPC5- and TRPC6-mediated calcium influx. Loss-of-function variants in synaptopodin result in the loss of stress fibers and reduction in RhoA abundance and activity (26). Membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted 2, encoded by MAGI2, directly binds to the cytosolic tail of nephrin and regulates actin cytoskeleton via RhoA. MAGI2 variants have been found in patients with congenital steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (27). Recently, together with DLC1, CDK20, TNS2, ITSN1, and ITSN2, MAGI2 variants were also found to be pathogenic in partial treatment-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. These genes encode a cluster of proteins that either physically or functionally interact to regulate RhoA/Rac1/Cdc42 activation. Interestingly, glucocorticoid treatment abolished the effect of DLC1 or CDK20 knockdown on RhoA activation in vitro (28).

Transcription Factors and Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genes

Pathogenic variants in transcription factors controlling the development of urogenital system can cause a wide spectrum of systemic syndromes with kidney involvement. WT1 was the first mutated gene discovered in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Variants in WT1 cause Denys–Drash syndrome and Frasier syndrome associated with urogenital abnormalities, malignant Wilms tumor, and gonadoblastoma. Missense variants affecting the WT1 DNA-binding site are associated with diffuse mesangial sclerosis, early-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, and rapid progression to kidney failure. Risk of Wilms tumor is associated with truncating variants and late-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Intronic variants usually present with isolated childhood-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and slower progression of kidney impairment (29). Paired box protein 2, encoded by PAX2, is another transcription factor with a central role in kidney development. Variants in PAX2 lead to dysregulation in PAX2 targets including WT1, resulting in disrupted podocyte and foot process development (30). LMX1B encodes LIM homeobox transcription factor 1β, which regulates slit diaphragm genes. Variants in LMX1B cause steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in isolation or in association with nail–patella syndrome. Variants in MAFB encoding MAF bZIP transcription factor B cause adolescence- to adult-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in association with Duane retraction syndrome, characterized by impaired horizontal eye movement. Variants in E2F3, encoding E2F transcription factor, leads to early-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and intellectual impairment, mediated by dysregulation of VEGF synthesis.

Pathogenic variants in genes encoding several members of the nuclear pore complexes have been identified, including NUP93, NUP25, NUP107, NUP85, NUP133, and NUP160. Nuclear pore complexes are large macromolecular assemblies in the nuclear envelope that mediate the transport of proteins, RNAs, and RNP particles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Of interest, in patients with NUP93 variants, some had partial response to corticosteroid and cyclosporin treatment (31).

Genetic mutations causing mitochondrial dysfunction may be present in the nuclear or mitochondrial genome. Mutations in mitochondrial gene MTTL1 cause mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (known as MELAS); diabetes; deafness; and steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome has also been reported in association with a case of neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa syndrome (known as NARP) caused by mutation in mitochondrial gene MT-ATP6 (32). Variants in enzymes involved in the coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) biosynthesis pathway in the mitochondria result in CoQ10 deficiency and may present with abnormalities in multiple systems including encephalopathy, neuromuscular involvement, and nephrotic syndrome. Importantly, early initiation of CoQ10 supplementation has been reported to improve kidney phenotype (33).

Complex Genetic Associations

Rather than following the Mendelian mode of inheritance, the APOL1 gene (encoding apolipoprotein L1) displays more complex risk associations with development of FSGS, nephrotic syndrome, and CKD with striking racial disparity. From genome-wide association studies, two independent variants in the APOL1 gene have been found to associate with FSGS and hypertensive kidney failure. These variants are common in populations of African descent but absent in populations of European descent and appear to be positively selected in recent evolution history. Experimentally, the kidney disease–associated ApoL1 variants were able to lyse the parasite Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, suggesting resistance to infection as the selection pressure (34).

Also based on genome-wide analyses, GPC5 encoding glypican 5, a member of the heparin sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) family, was also identified as a risk gene for nephrotic syndrome and conferred susceptibility to damage in diabetic kidney disease. Glypican 5 was shown to localize to the endothelial cells and podocytes in the human kidney. It is known to play a role in binding growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor 2, which has been implicated as a potential damaging signal in nephrotic syndrome (35).

Basement Membrane Genes

Laminin-521 is the major laminin isoform in GBM. It is a cruciform, heterotrimeric glycoprotein composed of the laminin α5, β2, and γ1 chains. During glomerulogenesis, laminin-521 trimers are secreted from podocytes and endothelial cells and polymerize in the extracellular matrix to form lattice-like networks on each edge of the GBM. Laminin also serves as a ligand for cellular receptors enabling cell adherence and signaling (36). Homozygous variants in LAMB2, the gene encoding laminin-β2, causes Pierson syndrome, which is characterized by congenital nephrotic syndrome with diffuse mesangial sclerosis, neurodevelopmental delay, and ocular abnormalities including microcoria and hypoplasia of the ciliary and pupillary muscles. Recently, three homozygous variants were found in LAMA5 encoding laminin-α5, which may have contributed to the development in nephrotic syndrome in pediatric patients (37).

Type IV collagen is another structural component of the GBM. There are six collagen IV α-chains encoded by the genes COL4A1–6. The α-chains assemble into trimers in the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in three distinct isoforms: α1α2α1, α3α4α5, and α5α6α5. Once released into the extracellular matrix, they polymerize to form collagen IV hexameric networks. The mature collagen IV network in the GBM is α3α4α5(IV), which is centrally located, and the less abundant α1α2α1(IV) is adjacent to glomerular endothelial cells. COL4A5 is located on the X chromosome, whereas COL4A3 and COL4A4 are linked on chromosome 2. Alport syndrome is caused by X-linked COL4A5 or recessive COL4A3/4 variants. Because most pathogenic variants prevent assembly of the trimer, a variant in one gene will lead to absence or inadequate assembly of all chains. Clinically, Alport syndrome is characterized by hematuria, proteinuria, and progressive decline in kidney function. There is also sensorineural deafness and ocular manifestations such as anterior lenticonus, posterior cataracts, and corneal dystrophy. Electron microscopy shows splitting and lamination of the GBM; this is thought to be due to extensive injury and remodeling of the GBM, giving it its characteristic “basket-weave” appearance.

Within the large number of COL4A3–5 variants associated with kidney disease, a wide spectrum of disease phenotypes and pathology has been observed. This ranges from classic Alport syndrome, to the more slowly progressive CKD in heterozygous COL4A3–5 variants associated with FSGS, to clinically nonprogressive thin basement membrane nephropathy (Figure 4) (36).

Although the link between genetic variants encoding type IV collagen chains and rare kidney disease is well established, recent large genetic cohort studies suggest COL4A genes have a role in diseases that are much more common. Variants in COL4A genes have been found to be associated with CKD, diabetic nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, and stroke (38–42). This is perhaps representative of the organ-specific function of basement membranes and the role of the different type IV collagen isoforms.

The integrin α3β1 heterodimer links the podocyte to the laminin network in the GBM and is the most highly expressed integrin on the podocyte cell surface (43). The α3 chain is encoded by ITGA3, and pathogenic variants have been found to cause congenital nephrotic syndrome, interstitial lung disease, and epidermolysis bullosa. Kidney histology in these cases revealed profoundly abnormal basement membranes, FSGS, and tubular atrophy (44). The α6β4 integrin also binds to laminin networks and stabilizes adhesions in hemidesmosomes. A homozygous variant in ITGB4 encoding the β4 chain has been identified in a case of congenital nephrotic syndrome with FSGS, epidermolysis bullosa, and pyloric atresia (45). GPC5 encodes glypican 5, a member of the HSPG family, which was identified as a risk gene conferring susceptibility for nephrotic syndrome and diabetic nephropathy (35,46). CD151 is a transmembrane tetraspanin broadly expressed by many cell types. Tetraspanins form membrane complexes on the base of podocyte foot processes along the GBM and allow clustering of associated proteins such as integrins and kinases, therefore enabling cellular signal transduction and cell-matrix adhesion (47). A homozygous variant in CD151 was detected in three patients with kidney failure. Electron microscopy revealed splitting of the tubular basement membrane along with reticulation and fragmentation of the GBM (48).

Genes Affecting Endothelial Cell Function

Dysregulation and overactivation of the alternative complement pathway cause endothelial damage and underlie the pathogenesis of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). Histologically, this disease process is characterized by thrombotic microangiopathy, with glomerular capillary wall thickening, endothelial swelling, and subendothelial accumulation of material. Of all aHUS cases, 50% are associated with genetic abnormalities in factor H, factor I, membrane cofactor protein, thrombomodulin, C3, and factor B. Notably, 3% of patients with aHUS carry more than one mutated complement gene (49).

Noncomplement genes have also been found to harbor variants associated with the development of aHUS, including two genes associated with podocyte pathology and steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in DGKE are linked to 1%–5% of aHUS cases, all presenting at <12 months of age. In endothelial cells, DGKε inactivates diacylglycerols, and defective DGKε leads to increased protein kinase C activity and endothelial cell activation. Interestingly, a subset of the children developed nephrotic syndrome 3–5 years after the onset of aHUS, a very rare event not usually seen with other forms of aHUS (50). Finally, variants in INF2, another gene related to steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, were found in familial aHUS or post-transplant thrombotic microangiopathy in the presence of common aHUS risk haplotypes (51).

Relative Contribution of Genetic Variants to Disease

Several large cohort studies have identified underlying genetic causes for childhood and early adult–onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome or FSGS in approximately 30% of cases (1–4). Distribution of causative genes and prevalence of monogenic diseases in these cohorts strongly correlated with age of onset. The most frequently mutated genes were NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1, and COL4A3/4/5; a significant but less prominent group of contributors included LAMB2, SMARCAL1, PLCE1, INF2, ADCK4, INF2, TRPC6, and COQ2 (1–4). In two of the largest international pediatric cohorts, genetic causes were found in close to 70% of congenital nephrotic syndrome cases (age <3 months), 35%–50% of infantile onset (3–12 months), 21%–25% of early childhood onset (1–6 years), 15%–19% in late childhood onset (6–12 years), and 10%–16% in adolescent onset (13–20 years) cases (1,2). In adults, mutations in COL4A3/4/5 were the commonest genetic abnormalities found in FSGS (55%) (52,53) and in a large heterogenous CKD cohort (30% of pathogenic variants identified) (42).

Current and Future Therapies

Because defects in the glomerular filtration barrier result in albuminuria, conventional therapy relies on (1) renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade to reduce proteinuria, (2) optimization of kidney disease risk factors such as BP control, and (3) KRT with dialysis or transplantation. In Alport syndrome, early initiation of RAAS blockade delays kidney failure by a median of 13 years (54). In addition, a genetic diagnosis helps to better understand the genotype-phenotype correlation of diseases and to stratify patients for management and prognosis. Detection of a genetic variant known to associate with extrarenal manifestations also prompts screening for these features (Table 1). Because most cases of nephrotic syndrome caused by genetic abnormalities are resistant to glucocorticoid and immunosuppressive therapy, early diagnosis can avoid their unnecessary use. On the other hand, patients with variants in NUP93, PTPRO, PLCE1, DLC1, DLC1, CDK20, TNS2, ITSN1, ITSN2, and MAGI2 achieved partial remission with glucocorticoid and/or immunosuppression, and this could prompt a future trial of treatment based on patient genotype. Understanding the genetic bases of disease has also yielded effective treatments for CoQ10 deficiency–related nephrotic syndrome and aHUS. Eculizumab, a humanized mAb against C5, has revolutionized the management of aHUS. Treatment with eculizumab is able to control disease activity and preserve kidney function in complement-associated aHUS.

Table 1.

Genetic mutations associated with extrarenal manifestations

| Gene | Associated Extrarenal Manifestations |

|---|---|

| WT1 | Denys–Drash syndrome: ambiguous genitalia, Wilms tumor, urogenital abnormalities |

| Frasier syndrome: ambiguous genitalia, gonadoblastoma | |

| LMX1B | Nail-patella syndrome: hypoplastic nails, absent patellae, skeletal abnormalities, glaucoma |

| SMARCAL1 | Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia: short stature, lumbar lordosis, T-cell immunodeficiency, skin hyperpigmentation, cerebral ischemia |

| E2F3 | Mental retardation |

| NXF5 | Heart block |

| PAX2 | Coloboma, hearing impairment |

| LMNA | Familial partial lipodystrophy |

| WDR73 | Galloway-Mowat syndrome: microcephaly, developmental delay, seizures, hiatal hernia, optic atrophy, movement disorders, intellectual disability |

| KEOPS complex (OSGEP, TP53RK, TPRKB, LAGE3) | |

| MAFB | Duane retraction syndrome: eye movement anomaly |

| MYH9 | Epstein syndrome: mild hearing loss, thrombocytopenia with giant platelets |

| INF2 | Charco–Marie–Tooth disease: chronic peripheral motor and sensory neuropathies |

| ARHGDIA | Seizures, cortical blindness |

| KAT2B | Cardiomyopathy |

| COQ2 | Coenzyme Q10 deficiency, progressive encephalomyopathy |

| COQ6 | Coenzyme Q10 deficiency, sensorineural hearing loss |

| PDSS2 | Leigh syndrome: coenzyme Q10 deficiency, hypotonia, seizures, ataxia, deafness, growth retardation |

| MTTL1 | MELAS syndrome: mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, strokelike episodes, diabetes, deafness |

| MT-ATP6 | NARP syndrome: neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa |

| SCARB2 | Action myoclonus–renal failure syndrome: myoclonus, seizures, tremor, sensorineural hearing loss |

| ZMPSTE24 | Mandibuloacral dysplasia: mandibular and clavicular hypoplasia, acro-osteolysis, cutaneous atrophy, partial lipodystrophy |

| PMM2 | Congenital defect of glycosylation |

| SPGL1 | SPL insufficiency syndrome: fetal hydrops, primary adrenal insufficiency, neurologic deterioration, immunodeficiency, acanthosis, endocrine abnormalities |

| LAMB2 | Pierson syndrome: ocular abnormalities, hypotonia, movement disorder |

| COL4A3/4/5 | Alport syndrome: sensorineural hearing loss, ocular abnormalities |

| ITGA3 | Epidermolysis bullosa, interstitial lung disease |

| ITGB4 | Epidermolysis bullosa, pyloric atresia |

In addition, although patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome who have a confirmed genetic diagnosis have increased risks of disease progression toward kidney failure, their risks of recurrence after kidney transplant are extremely low compared with those without (30%–50% risk) (1,55,56). Genetic diagnosis is also important in evaluating family members for living kidney donation, especially in cases of complex genetic associations such as APOL1 and complement genes. However, underlying genetic causes have only been identified in approximately 30% of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and 50% of aHUS. Better understanding of the biology of the glomerular filtration barrier and further screening of large population cohorts will undoubtedly increase the yield of genetic testing for reaching a molecular diagnosis.

Much hope has been placed upon gene therapy in genetic disorders. Studies showing feasibility and proof of principle have been undertaken in Alport mice. Incorporating collagen α3α4α5(IV) chains after initial assembly via activation by a tetracycline induced transgene-delayed proteinuria (57). This suggests a possible target for genetic rescue in Alport syndrome. In fact, prior research showed a transgene was able to rescue Col4a3−/− mice, which had an Alport phenotype, resulting in normal levels of proteinuria after 6 months of follow-up (58). There remain many hurdles to overcome before this treatment modality could be attempted in a human model, including ethical considerations and vector transport.

Summary

Our ability to reach a molecular diagnosis for children and adults with glomerular disease has been transformed over the past 3 decades due to genetic discoveries. The expanding list of genetic disorders is also providing important insight into the underlying biology of the glomerular filtration barrier. The ontologic clustering of genes highlights the important role of the podocyte silt diaphragm, the cytoskeleton, and its interaction with the GBM. These may represent the importance of these specialized structures for sensing and responding to mechanical strain from capillary blood flow, because our most effective treatment for these disorders (RAAS blockade) reduces capillary hydrostatic pressure. The endothelial cell genetics highlights the susceptibility of the glomerular endothelium to complement dysregulation, and the resolution of these mechanisms has led to highly effective therapy based on a mechanistic understanding of the underlying disease process. In the decades ahead, further dissection of disease mechanisms should lead to new therapies to preserve native kidney function and prevent progression to kidney failure.

Disclosures

R. Lennon acted as an advisor for the following companies within the past 36 months: Liponext, Ono Pharmaceuticals, and Retrophin. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

J.F. Ingham is a year 3 foundation doctor undertaking academic training supported by the University of Manchester. R. Lennon is supported by the Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship award 202860/Z/16/Z and has received research funding from Kidney Research UK and the Medical Research Council. A.S. Li is a clinical research training fellow funded by Shire and the charity Kidneys for Life in the form of an educational grant.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Siddharth Banka (consultant clinical geneticist at Manchester University National Health Service Foundation Trust and clinical senior lecturer at the University of Manchester) for critical review of the manuscript and Craig Lawless for help with the Gene Ontology enrichment analysis.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Trautmann A, Bodria M, Ozaltin F, Gheisari A, Melk A, Azocar M, Anarat A, Caliskan S, Emma F, Gellermann J, Oh J, Baskin E, Ksiazek J, Remuzzi G, Erdogan O, Akman S, Dusek J, Davitaia T, Özkaya O, Papachristou F, Firszt-Adamczyk A, Urasinski T, Testa S, Krmar RT, Hyla-Klekot L, Pasini A, Özcakar ZB, Sallay P, Cakar N, Galanti M, Terzic J, Aoun B, Caldas Afonso A, Szymanik-Grzelak H, Lipska BS, Schnaidt S, Schaefer F; PodoNet Consortium: Spectrum of steroid-resistant and congenital nephrotic syndrome in children: The PodoNet registry cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 592–600, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadowski CE, Lovric S, Ashraf S, Pabst WL, Gee HY, Kohl S, Engelmann S, Vega-Warner V, Fang H, Halbritter J, Somers MJ, Tan W, Shril S, Fessi I, Lifton RP, Bockenhauer D, El-Desoky S, Kari JA, Zenker M, Kemper MJ, Mueller D, Fathy HM, Soliman NA, Hildebrandt F; SRNS Study Group: A single-gene cause in 29.5% of cases of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1279–1289, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bierzynska A, McCarthy HJ, Soderquest K, Sen ES, Colby E, Ding WY, Nabhan MM, Kerecuk L, Hegde S, Hughes D, Marks S, Feather S, Jones C, Webb NJ, Ognjanovic M, Christian M, Gilbert RD, Sinha MD, Lord GM, Simpson M, Koziell AB, Welsh GI, Saleem MA: Genomic and clinical profiling of a national nephrotic syndrome cohort advocates a precision medicine approach to disease management. Kidney Int 91: 937–947, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang M, Chun J, Genovese G, Knob AU, Benjamin A, Wilkins MS, Friedman DJ, Appel GB, Lifton RP, Mane S, Pollak MR: Contributions of rare gene variants to familial and sporadic FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1625–1640, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Retterer K, Juusola J, Cho MT, Vitazka P, Millan F, Gibellini F, Vertino-Bell A, Smaoui N, Neidich J, Monaghan KG, McKnight D, Bai R, Suchy S, Friedman B, Tahiliani J, Pineda-Alvarez D, Richard G, Brandt T, Haverfield E, Chung WK, Bale S: Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet Med 18: 696–704, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yarmolinsky M, Hoess R: The legacy of nat sternberg: The genesis of cre-lox technology. Annu Rev Virol 2: 25–40, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WareJoncas Z, Campbell JM, Martínez-Gálvez G, Gendron WAC, Barry MA, Harris PC, Sussman CR, Ekker SC: Precision gene editing technology and applications in nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol 14: 663–677, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun DA, Rao J, Mollet G, Schapiro D, Daugeron MC, Tan W, Gribouval O, Boyer O, Revy P, Jobst-Schwan T, Schmidt JM, Lawson JA, Schanze D, Ashraf S, Ullmann JFP, Hoogstraten CA, Boddaert N, Collinet B, Martin G, Liger D, Lovric S, Furlano M, Guerrera IC, Sanchez-Ferras O, Hu JF, Boschat AC, Sanquer S, Menten B, Vergult S, De Rocker N, Airik M, Hermle T, Shril S, Widmeier E, Gee HY, Choi WI, Sadowski CE, Pabst WL, Warejko JK, Daga A, Basta T, Matejas V, Scharmann K, Kienast SD, Behnam B, Beeson B, Begtrup A, Bruce M, Ch’ng GS, Lin SP, Chang JH, Chen CH, Cho MT, Gaffney PM, Gipson PE, Hsu CH, Kari JA, Ke YY, Kiraly-Borri C, Lai WM, Lemyre E, Littlejohn RO, Masri A, Moghtaderi M, Nakamura K, Ozaltin F, Praet M, Prasad C, Prytula A, Roeder ER, Rump P, Schnur RE, Shiihara T, Sinha MD, Soliman NA, Soulami K, Sweetser DA, Tsai WH, Tsai JD, Topaloglu R, Vester U, Viskochil DH, Vatanavicharn N, Waxler JL, Wierenga KJ, Wolf MTF, Wong SN, Leidel SA, Truglio G, Dedon PC, Poduri A, Mane S, Lifton RP, Bouchard M, Kannu P, Chitayat D, Magen D, Callewaert B, van Tilbeurgh H, Zenker M, Antignac C, Hildebrandt F: Mutations in KEOPS-complex genes cause nephrotic syndrome with primary microcephaly. Nat Genet 49: 1529–1538, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rennke HG, Cotran RS, Venkatachalam MA: Role of molecular charge in glomerular permeability. Tracer studies with cationized ferritins. J Cell Biol 67: 638–646, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrakka J, Tryggvason K: Molecular make-up of the glomerular filtration barrier. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 396: 164–169, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St John PL, Abrahamson DR: Glomerular endothelial cells and podocytes jointly synthesize laminin-1 and -11 chains. Kidney Int 60: 1037–1046, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lennon R, Byron A, Humphries JD, Randles MJ, Carisey A, Murphy S, Knight D, Brenchley PE, Zent R, Humphries MJ: Global analysis reveals the complexity of the human glomerular extracellular matrix. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 939–951, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kestilä M, Lenkkeri U, Männikkö M, Lamerdin J, McCready P, Putaala H, Ruotsalainen V, Morita T, Nissinen M, Herva R, Kashtan CE, Peltonen L, Holmberg C, Olsen A, Tryggvason K: Positionally cloned gene for a novel glomerular protein--nephrin--is mutated in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Mol Cell 1: 575–582, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koziell A, Grech V, Hussain S, Lee G, Lenkkeri U, Tryggvason K, Scambler P: Genotype/phenotype correlations of NPHS1 and NPHS2 mutations in nephrotic syndrome advocate a functional inter-relationship in glomerular filtration. Hum Mol Genet 11: 379–388, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solanki AK, Widmeier E, Arif E, Sharma S, Daga A, Srivastava P, Kwon SH, Hugo H, Nakayama M, Mann N, Majmundar AJ, Tan W, Gee HY, Sadowski CE, Rinat C, Becker-Cohen R, Bergmann C, Rosen S, Somers M, Shril S, Huber TB, Mane S, Hildebrandt F, Nihalani D: Mutations in KIRREL1, a slit diaphragm component, cause steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int 96: 883–889, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Wang L, Wan L, Lin T, Zhao W, Cui H, Li H, Cao L, Wu J, Zhang T: Mutational spectrum and novel candidate genes in Chinese children with sporadic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Res 85: 816–821, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, Farrington MK, Creazzo T, Hawkins AF, Daskalakis N, Kwan SY, Ebersviller S, Burchette JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Howell DN, Vance JM, Rosenberg PB: A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science 308: 1801–1804, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilatovskaya DV, Staruschenko A: TRPC6 channel as an emerging determinant of the podocyte injury susceptibility in kidney diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 309: F393–F397, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barua M, Shieh E, Schlondorff J, Genovese G, Kaplan BS, Pollak MR: Exome sequencing and in vitro studies identified podocalyxin as a candidate gene for focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 85: 124–133, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozaltin F, Ibsirlioglu T, Taskiran EZ, Baydar DE, Kaymaz F, Buyukcelik M, Kilic BD, Balat A, Iatropoulos P, Asan E, Akarsu NA, Schaefer F, Yilmaz E, Bakkaloglu A; PodoNet Consortium: Disruption of PTPRO causes childhood-onset nephrotic syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 89: 139–147, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavenstädt H, Kriz W, Kretzler M: Cell biology of the glomerular podocyte. Physiol Rev 83: 253–307, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mele C, Iatropoulos P, Donadelli R, Calabria A, Maranta R, Cassis P, Buelli S, Tomasoni S, Piras R, Krendel M, Bettoni S, Morigi M, Delledonne M, Pecoraro C, Abbate I, Capobianchi MR, Hildebrandt F, Otto E, Schaefer F, Macciardi F, Ozaltin F, Emre S, Ibsirlioglu T, Benigni A, Remuzzi G, Noris M; PodoNet Consortium: MYO1E mutations and childhood familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med 365: 295–306, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan JM, Kim SH, North KN, Rennke H, Correia LA, Tong HQ, Mathis BJ, Rodríguez-Pérez JC, Allen PG, Beggs AH, Pollak MR: Mutations in ACTN4, encoding alpha-actinin-4, cause familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet 24: 251–256, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akilesh S, Koziell A, Shaw AS: Basic science meets clinical medicine: Identification of a CD2AP-deficient patient. Kidney Int 72: 1181–1183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gee HY, Zhang F, Ashraf S, Kohl S, Sadowski CE, Vega-Warner V, Zhou W, Lovric S, Fang H, Nettleton M, Zhu JY, Hoefele J, Weber LT, Podracka L, Boor A, Fehrenbach H, Innis JW, Washburn J, Levy S, Lifton RP, Otto EA, Han Z, Hildebrandt F: KANK deficiency leads to podocyte dysfunction and nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest 125: 2375–2384, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buvall L, Wallentin H, Sieber J, Andreeva S, Choi HY, Mundel P, Greka A: Synaptopodin is a coincidence detector of tyrosine versus serine/threonine phosphorylation for the modulation of Rho protein crosstalk in podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 837–851, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bierzynska A, Soderquest K, Dean P, Colby E, Rollason R, Jones C, Inward CD, McCarthy HJ, Simpson MA, Lord GM, Williams M, Welsh GI, Koziell AB, Saleem MA; NephroS; UK study of Nephrotic Syndrome: MAGI2 mutations cause congenital nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1614–1621, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashraf S, Kudo H, Rao J, Kikuchi A, Widmeier E, Lawson JA, Tan W, Hermle T, Warejko JK, Shril S, Airik M, Jobst-Schwan T, Lovric S, Braun DA, Gee HY, Schapiro D, Majmundar AJ, Sadowski CE, Pabst WL, Daga A, van der Ven AT, Schmidt JM, Low BC, Gupta AB, Tripathi BK, Wong J, Campbell K, Metcalfe K, Schanze D, Niihori T, Kaito H, Nozu K, Tsukaguchi H, Tanaka R, Hamahira K, Kobayashi Y, Takizawa T, Funayama R, Nakayama K, Aoki Y, Kumagai N, Iijima K, Fehrenbach H, Kari JA, El Desoky S, Jalalah S, Bogdanovic R, Stajić N, Zappel H, Rakhmetova A, Wassmer SR, Jungraithmayr T, Strehlau J, Kumar AS, Bagga A, Soliman NA, Mane SM, Kaufman L, Lowy DR, Jairajpuri MA, Lifton RP, Pei Y, Zenker M, Kure S, Hildebrandt F: Mutations in six nephrosis genes delineate a pathogenic pathway amenable to treatment. Nat Commun 9: 1960, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipska BS, Ranchin B, Iatropoulos P, Gellermann J, Melk A, Ozaltin F, Caridi G, Seeman T, Tory K, Jankauskiene A, Zurowska A, Szczepanska M, Wasilewska A, Harambat J, Trautmann A, Peco-Antic A, Borzecka H, Moczulska A, Saeed B, Bogdanovic R, Kalyoncu M, Simkova E, Erdogan O, Vrljicak K, Teixeira A, Azocar M, Schaefer F; PodoNet Consortium: Genotype-phenotype associations in WT1 glomerulopathy. Kidney Int 85: 1169–1178, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vivante A, Chacham OS, Shril S, Schreiber R, Mane SM, Pode-Shakked B, Soliman NA, Koneth I, Schiffer M, Anikster Y, Hildebrandt F: Dominant PAX2 mutations may cause steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and FSGS in children. Pediatr Nephrol 34: 1607–1613, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun DA, Sadowski CE, Kohl S, Lovric S, Astrinidis SA, Pabst WL, Gee HY, Ashraf S, Lawson JA, Shril S, Airik M, Tan W, Schapiro D, Rao J, Choi WI, Hermle T, Kemper MJ, Pohl M, Ozaltin F, Konrad M, Bogdanovic R, Büscher R, Helmchen U, Serdaroglu E, Lifton RP, Antonin W, Hildebrandt F: Mutations in nuclear pore genes NUP93, NUP205 and XPO5 cause steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Nat Genet 48: 457–465, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemoine S, Panaye M, Rabeyrin M, Errazuriz-Cerda E, Mousson de Camaret B, Petiot P, Juillard L, Guebre-Egziabher F: Renal involvement in neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa (NARP) syndrome: A case report. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 754–757, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bezdicka M, Dluholucky M, Cinek O, Zieg J: Successful maintenance of partial remission in a child with COQ2 nephropathy by coenzyme Q10 treatment. Nephrology (Carlton) 25: 187–188, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Langefeld CD, Oleksyk TK, Uscinski Knob AL, Bernhardy AJ, Hicks PJ, Nelson GW, Vanhollebeke B, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Pays E, Pollak MR: Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 329: 841–845, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okamoto K, Tokunaga K, Doi K, Fujita T, Suzuki H, Katoh T, Watanabe T, Nishida N, Mabuchi A, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Maeda S, Nakamura Y, Noiri E: Common variation in GPC5 is associated with acquired nephrotic syndrome. Nat Genet 43: 459–463, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Funk SD, Lin MH, Miner JH: Alport syndrome and Pierson syndrome: Diseases of the glomerular basement membrane. Matrix Biol 71-72: 250–261, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun DA, Warejko JK, Ashraf S, Tan W, Daga A, Schneider R, Hermle T, Jobst-Schwan T, Widmeier E, Majmundar AJ, Nakayama M, Schapiro D, Rao J, Schmidt JM, Hoogstraten CA, Hugo H, Bakkaloglu SA, Kari JA, El Desoky S, Daouk G, Mane S, Lifton RP, Shril S, Hildebrandt F: Genetic variants in the LAMA5 gene in pediatric nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34: 485–493, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeanne M, Labelle-Dumais C, Jorgensen J, Kauffman WB, Mancini GM, Favor J, Valant V, Greenberg SM, Rosand J, Gould DB: COL4A2 mutations impair COL4A1 and COL4A2 secretion and cause hemorrhagic stroke. Am J Hum Genet 90: 91–101, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malik R, Chauhan G, Traylor M, Sargurupremraj M, Okada Y, Mishra A, Rutten-Jacobs L, Giese AK, van der Laan SW, Gretarsdottir S, Anderson CD, Chong M, Adams HHH, Ago T, Almgren P, Amouyel P, Ay H, Bartz TM, Benavente OR, Bevan S, Boncoraglio GB, Brown RD Jr., Butterworth AS, Carrera C, Carty CL, Chasman DI, Chen WM, Cole JW, Correa A, Cotlarciuc I, Cruchaga C, Danesh J, de Bakker PIW, DeStefano AL, den Hoed M, Duan Q, Engelter ST, Falcone GJ, Gottesman RF, Grewal RP, Gudnason V, Gustafsson S, Haessler J, Harris TB, Hassan A, Havulinna AS, Heckbert SR, Holliday EG, Howard G, Hsu FC, Hyacinth HI, Ikram MA, Ingelsson E, Irvin MR, Jian X, Jiménez-Conde J, Johnson JA, Jukema JW, Kanai M, Keene KL, Kissela BM, Kleindorfer DO, Kooperberg C, Kubo M, Lange LA, Langefeld CD, Langenberg C, Launer LJ, Lee JM, Lemmens R, Leys D, Lewis CM, Lin WY, Lindgren AG, Lorentzen E, Magnusson PK, Maguire J, Manichaikul A, McArdle PF, Meschia JF, Mitchell BD, Mosley TH, Nalls MA, Ninomiya T, O’Donnell MJ, Psaty BM, Pulit SL, Rannikmäe K, Reiner AP, Rexrode KM, Rice K, Rich SS, Ridker PM, Rost NS, Rothwell PM, Rotter JI, Rundek T, Sacco RL, Sakaue S, Sale MM, Salomaa V, Sapkota BR, Schmidt R, Schmidt CO, Schminke U, Sharma P, Slowik A, Sudlow CLM, Tanislav C, Tatlisumak T, Taylor KD, Thijs VNS, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Tiedt S, Trompet S, Tzourio C, van Duijn CM, Walters M, Wareham NJ, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Wilson JG, Wiggins KL, Yang Q, Yusuf S, Bis JC, Pastinen T, Ruusalepp A, Schadt EE, Koplev S, Björkegren JLM, Codoni V, Civelek M, Smith NL, Trégouët DA, Christophersen IE, Roselli C, Lubitz SA, Ellinor PT, Tai ES, Kooner JS, Kato N, He J, van der Harst P, Elliott P, Chambers JC, Takeuchi F, Johnson AD, Sanghera DK, Melander O, Jern C, Strbian D, Fernandez-Cadenas I, Longstreth WT Jr., Rolfs A, Hata J, Woo D, Rosand J, Pare G, Hopewell JC, Saleheen D, Stefansson K, Worrall BB, Kittner SJ, Seshadri S, Fornage M, Markus HS, Howson JMM, Kamatani Y, Debette S, Dichgans M; AFGen Consortium; Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Consortium; International Genomics of Blood Pressure (iGEN-BP) Consortium; INVENT Consortium; STARNET; BioBank Japan Cooperative Hospital Group; COMPASS Consortium; EPIC-CVD Consortium; EPIC-InterAct Consortium; International Stroke Genetics Consortium (ISGC); METASTROKE Consortium; Neurology Working Group of the CHARGE Consortium; NINDS Stroke Genetics Network (SiGN); UK Young Lacunar DNA Study; MEGASTROKE Consortium: Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes [published correction appears in Nat Genet 51: 1192–1193, 2019]. Nat Genet 50: 524–537, 2018. 29531354 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salem RM, Todd JN, Sandholm N, Cole JB, Chen WM, Andrews D, Pezzolesi MG, McKeigue PM, Hiraki LT, Qiu C, Nair V, Di Liao C, Cao JJ, Valo E, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Smiles AM, McGurnaghan SJ, Haukka JK, Harjutsalo V, Brennan EP, van Zuydam N, Ahlqvist E, Doyle R, Ahluwalia TS, Lajer M, Hughes MF, Park J, Skupien J, Spiliopoulou A, Liu A, Menon R, Boustany-Kari CM, Kang HM, Nelson RG, Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, Gao X, Mauer M, Maestroni S, Caramori ML, de Boer IH, Miller RG, Guo J, Boright AP, Tregouet D, Gyorgy B, Snell-Bergeon JK, Maahs DM, Bull SB, Canty AJ, Palmer CNA, Stechemesser L, Paulweber B, Weitgasser R, Sokolovska J, Rovīte V, Pīrāgs V, Prakapiene E, Radzeviciene L, Verkauskiene R, Panduru NM, Groop LC, McCarthy MI, Gu HF, Möllsten A, Falhammar H, Brismar K, Martin F, Rossing P, Costacou T, Zerbini G, Marre M, Hadjadj S, McKnight AJ, Forsblom C, McKay G, Godson C, Maxwell AP, Kretzler M, Susztak K, Colhoun HM, Krolewski A, Paterson AD, Groop PH, Rich SS, Hirschhorn JN, Florez JC; SUMMIT Consortium, DCCT/EDIC Research Group, GENIE Consortium: Genome-wide association study of diabetic kidney disease highlights biology involved in glomerular basement membrane collagen. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 2000–2016, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steffensen LB, Rasmussen LM: A role for collagen type IV in cardiovascular disease? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 315: H610–H625, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Groopman EE, Marasa M, Cameron-Christie S, Petrovski S, Aggarwal VS, Milo-Rasouly H, Li Y, Zhang J, Nestor J, Krithivasan P, Lam WY, Mitrotti A, Piva S, Kil BH, Chatterjee D, Reingold R, Bradbury D, DiVecchia M, Snyder H, Mu X, Mehl K, Balderes O, Fasel DA, Weng C, Radhakrishnan J, Canetta P, Appel GB, Bomback AS, Ahn W, Uy NS, Alam S, Cohen DJ, Crew RJ, Dube GK, Rao MK, Kamalakaran S, Copeland B, Ren Z, Bridgers J, Malone CD, Mebane CM, Dagaonkar N, Fellström BC, Haefliger C, Mohan S, Sanna-Cherchi S, Kiryluk K, Fleckner J, March R, Platt A, Goldstein DB, Gharavi AG: Diagnostic utility of exome sequencing for kidney disease. N Engl J Med 380: 142–151, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lennon R, Randles MJ, Humphries MJ: The importance of podocyte adhesion for a healthy glomerulus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5: 160, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Has C, Spartà G, Kiritsi D, Weibel L, Moeller A, Vega-Warner V, Waters A, He Y, Anikster Y, Esser P, Straub BK, Hausser I, Bockenhauer D, Dekel B, Hildebrandt F, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Laube GF: Integrin α3 mutations with kidney, lung, and skin disease. N Engl J Med 366: 1508–1514, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kambham N, Tanji N, Seigle RL, Markowitz GS, Pulkkinen L, Uitto J, D’Agati VD: Congenital focal segmental glomerulosclerosis associated with beta4 integrin mutation and epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 190–196, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okamoto K, Honda K, Doi K, Ishizu T, Katagiri D, Wada T, Tomita K, Ohtake T, Kaneko T, Kobayashi S, Nangaku M, Tokunaga K, Noiri E: Glypican-5 increases susceptibility to nephrotic damage in diabetic kidney. Am J Pathol 185: 1889–1898, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naudin C, Smith B, Bond DR, Dun MD, Scott RJ, Ashman LK, Weidenhofer J, Roselli S: Characterization of the early molecular changes in the glomeruli of Cd151 -/- mice highlights induction of mindin and MMP-10. Sci Rep 7: 15987, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karamatic Crew V, Burton N, Kagan A, Green CA, Levene C, Flinter F, Brady RL, Daniels G, Anstee DJ: CD151, the first member of the tetraspanin (TM4) superfamily detected on erythrocytes, is essential for the correct assembly of human basement membranes in kidney and skin. Blood 104: 2217–2223, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bresin E, Rurali E, Caprioli J, Sanchez-Corral P, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Pinto S, Goodship TH, Alberti M, Ribes D, Valoti E, Remuzzi G, Noris M; European Working Party on Complement Genetics in Renal Diseases: Combined complement gene mutations in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome influence clinical phenotype. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 475–486, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lemaire M, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Schaefer F, Choi M, Tang WH, Le Quintrec M, Fakhouri F, Taque S, Nobili F, Martinez F, Ji W, Overton JD, Mane SM, Nürnberg G, Altmüller J, Thiele H, Morin D, Deschenes G, Baudouin V, Llanas B, Collard L, Majid MA, Simkova E, Nürnberg P, Rioux-Leclerc N, Moeckel GW, Gubler MC, Hwa J, Loirat C, Lifton RP: Recessive mutations in DGKE cause atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Nat Genet 45: 531–536, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Challis RC, Ring T, Xu Y, Wong EK, Flossmann O, Roberts IS, Ahmed S, Wetherall M, Salkus G, Brocklebank V, Fester J, Strain L, Wilson V, Wood KM, Marchbank KJ, Santibanez-Koref M, Goodship TH, Kavanagh D: Thrombotic microangiopathy in inverted formin 2-mediated renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1084–1091, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gast C, Pengelly RJ, Lyon M, Bunyan DJ, Seaby EG, Graham N, Venkat-Raman G, Ennis S: Collagen (COL4A) mutations are the most frequent mutations underlying adult focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 961–970, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao T, Udwan K, John R, Rana A, Haghighi A, Xu L, Hack S, Reich HN, Hladunewich MA, Cattran DC, Paterson AD, Pei Y, Barua M: Integration of genetic testing and pathology for the diagnosis of adults with FSGS. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 213–223, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gross O, Friede T, Hilgers R, Görlitz A, Gavénis K, Ahmed R, Dürr U: Safety and efficacy of the ACE-inhibitor ramipril in alport syndrome: The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III EARLY PRO-TECT Alport trial in pediatric patients. ISRN Pediatr 2012: 436046, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bierzynska A, Saleem MA: Deriving and understanding the risk of post-transplant recurrence of nephrotic syndrome in the light of current molecular and genetic advances. Pediatr Nephrol 33: 2027–2035, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feltran LS, Varela P, Silva ED, Veronez CL, Franco MC, Filho AP, Camargo MF, Koch Nogueira PC, Pesquero JB: Targeted next-generation sequencing in Brazilian children with nephrotic syndrome submitted to renal transplant. Transplantation 101: 2905–2912, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin X, Suh JH, Go G, Miner JH: Feasibility of repairing glomerular basement membrane defects in Alport syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 687–692, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heidet L, Borza DB, Jouin M, Sich M, Mattei MG, Sado Y, Hudson BG, Hastie N, Antignac C, Gubler MC: A human-mouse chimera of the alpha3alpha4alpha5(IV) collagen protomer rescues the renal phenotype in Col4a3-/- Alport mice. Am J Pathol 163: 1633–1644, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY: clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16: 284–287, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]