Chiroptera is the second largest mammalian order in terms of species number. So far, there are more than 1400 known bat species across the six continents, making up 20% of the total number of mammalian species.1 Bats are well recognized to be the hosts of a number of highly pathogenic viruses, such as rabies virus, Hendra virus, Nipah virus, and Ebola virus, for a long time.2–5 Shortly after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic which originated from Southern China in 2003, we discovered that bats were the ultimate reservoir of SARS-related coronavirus(SARSr-CoV).6 In 2012, the cause of the even more fatal Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) which originated from the Middle East was also found to be another CoV, MERS-CoV.7 The ancestor of MERS-CoV was also from bats.8,9 Recently, the COVID-19 outbreak that has already officially infected more than 13 million patients with more than 574 000 deaths was also confirmed to be due to another betacoronavirus, named SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), from bats.10 Moreover, bat cell lines have also been harvested and propagated for the study of SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2.11,12 All these have put studies of bats at the center of the stage.

Since the SARS epidemic, we have been performing systematic studies to search for novel viruses from bats in Hong Kong.13,14 During the last 14 years, we have collected samples from a total of more than 8000 bats from various locations in Hong Kong. Recently, Cooper et al. investigated sex ratios in over two million bird and mammal specimen records from natural history museum collections. They found a bias towards males in all the six largest orders of mammals except Chiroptera, in which a slight bias towards females was observed. The authors suggested that female bats were more likely captured because female roosts were more often bigger and past practice of bat collectors was to collect the entire roosts and therefore may have accidentally collected more female than male bats.15 We hypothesize that such a sex bias may also be present in the samples we and other bat researchers collected. Such a potential bias would be important as it may skew the results of the questions bat researchers intend to answer. To test this hypothesis, we retrieved the records of all these bat samples and analyzed their sex bias.

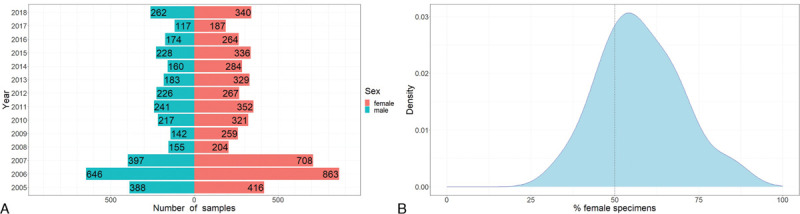

Records from a total of 8705 non-duplicated bat samples collected over a 14-year period (2005–2018) were retrieved. These bats, belonging to 26 species, were sampled from 54 different locations in Hong Kong. Among the 8705 samples, 40 (0.46%) had no records on the sex of the bats and were not included in the analysis. Of the remaining 8665 samples, 3535 (40.61%) were from male and 5130 (58.93%) from female bats. A bias towards females was consistently observed in all the 14 years (P < 0.001 by Wilcoxon signed rank test) (Figure 1A). The proportion of female samples varied across bat species (Figure 1B). Among the top ten sampled species represented by more than 100 samples, eight [Chinese horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus sinicus), Pomona leaf-nosed bat (Hipposideros pomona), common bent-winged bat (Miniopterus schreibersii), lesser bent-winged bat (Miniopterus pusillus), intermediate horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis), Himalayan leaf-nosed bat (Hipposideros armiger), Japanese pipistelle (Pipistrellus abramus), lesser bamboo bat (Tylonycteris pachypus)] have more females than males.

Figure 1.

A: Sex distribution of 8665 bat samples collected in Hong Kong from 2005 to 2018. B: Kernal density plots showing the percentage female specimens in bats. Only species with at least 20 specimens are included. The dashed line represents 50% female specimens.

In this study, we observed a consistent bias towards female bats that were captured. Bats make up around half of the native mammalian diversity in Hong Kong, where they mainly roost in caves, trees, and tunnels. During specimen collection, often multiple bats from a number of clusters or aggregations in a roost site were sampled. In the study by Cooper et al., 52.2% of the captured bats were females. In our present study, we observed an even higher bias, with 58.93% of the captured bats being females. Most of the bats sampled were captured during daytime from their roosting sites and it is likely that their roosting or breeding behaviors have led to the biased sex ratio. For example, for Chinese horseshoe bats which make up the largest number of samples, there is a strong sexual segregation observed during the breeding season, of which female bats tend to form large aggregations of nursery roosts during parturition and lactation, while male bats usually roost alone or in small groups.16 Furthermore, females may be easier to capture in roosting caves, particularly when they are carrying babies. On the other hand, for other mammals including rodents, soricomorpha, carnivores, primates, and artiodactyla, samples from males were collected more frequently. This maybe because males tend to attract hunter's attention and/or are more likely to wander away from their homes.15 Similar to museum professionals, microbiologists should be aware of the bias within our samples and whether such bias may skew the results of the questions we intend to answer. For example, the strain of a virus detected in female bats that are more easily captured for sampling may be different from the strain found in male bats that are more likely to be transmitted to other potential hosts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank C. T. Shek, Agriculture, Fisheries, and Conservation Department, HKSAR, for his invaluable advice and useful discussions. The collection of bat samples for surveillance study was approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Animals for Teaching and Research, the University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

References

- [1].American Society of Mammalogist. Mammal Diversity Database. Available from: https://mammaldiversityorg/#Y2hpcm9wdGVyYSZnbG9iYWxfc2VhcmNoPXRydWUmbG9vc2U9dHJ1ZQ. Accessed 21st August, 2020.

- [2].Badrane H, Tordo N. Host switching in Lyssavirus history from the Chiroptera to the Carnivora orders. J Virol 2001;75(17):8096–8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Halpin K, Young PL, Field HE, Mackenzie JS. Isolation of Hendra virus from pteropid bats: a natural reservoir of Hendra virus. J Gen Virol 2000;81(Pt 8):1927–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, et al. Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12(2):235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, et al. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 2005;438(7068):575–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102(39):14040–14045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 2012;367(19):1814–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lau SK, Li KS, Tsang AK, et al. Genetic characterization of Betacoronavirus lineage C viruses in bats reveals marked sequence divergence in the spike protein of pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 in Japanese pipistrelle: implications for the origin of the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 2013;87(15):8638–8650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lau SKP, Zhang L, Luk HKH, et al. Receptor usage of a novel bat lineage C Betacoronavirus reveals evolution of Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus spike proteins for human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 binding. J Infect Dis 2018;218(2):197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lau SKP, Luk HKH, Wong ACP, et al. Possible bat origin of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26(7):1542–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lau SKP, Fan RYY, Luk HKH, et al. Replication of MERS and SARS coronaviruses in bat cells offers insights to their ancestral origins. Emerg Microbes Infect 2018;7(1):209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lau SKP, Wong ACP, Luk HKH, et al. Differential tropism of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in bat cells. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26(12):2961–2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lau SK, Woo PC, Lai KK, et al. Complete genome analysis of three novel picornaviruses from diverse bat species. J Virol 2011;85(17):8819–8828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Woo PC, Lau SK, Li KS, et al. Molecular diversity of coronaviruses in bats. Virology 2006;351(1):180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cooper N, Bond AL, Davis JL, Portela Miguez R, Tomsett L, Helgen KM. Sex biases in bird and mammal natural history collections. Proc Biol Sci 2019;286(1913):20192025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shek CT. A Field Guide to the Terrestrial Mammals of Hong Kong. 1st edHong Kong, China: Friends of the Country Parks; 2006. [Google Scholar]