Abstract

People integrate the valence of behavior and that of outcome when making moral judgments. However, the role of culture in the development of this integration among young children remains unclear. We investigated cultural similarities and differences in moral judgments by measuring both visual attention and verbal evaluations. Three- and four-year-olds from Japan and the U.S. (N = 141) were shown sociomoral scenarios that varied in agents’ behavior which reflected prosocial or antisocial intention and recipients’ emotional outcome (happy, neutral, or sad); then, they were asked to evaluate agents’ moral trait. Their eye fixations while observing moral scenarios were measured using an eye-tracker. We found culturally similar tendencies in the integration of behavior and outcome; however, a cultural difference was shown in their verbal evaluation. The link between implicit attention and explicit verbal evaluation was negligible. Both culturally shared and specific aspects of sociomoral development are discussed.

Keywords: attention, cross-cultural comparison, implicit and explicit processes, moral development, sociomoral trait evaluation, young children

Moral judgments are fundamental to humans’ social cognition—people spontaneously and easily infer morally good or bad traits from others’ behaviors (Goodwin, 2015; Todorov, Said, Engell, & Oosterhof, 2008; Uleman, Saribay, & Gonzalez, 2008). However, more complex judgment includes both trait-based inference, based on observed behaviors, and an understanding of the affective perspective of the victim or recipient of the action (Jensen, Vaish, & Schmidt, 2014). Since Piaget’s (1932) seminal work, the shift from outcome-based to intent-based moral judgment has been one of the central issues in the literature investigating the development of sociomoral understanding. A substantial body of evidence suggests that, when intention and outcomes conflict (e.g., attempted harm causes pleasure), children under 5 years of age are likely to use outcome information when making moral judgments; however, as children develop, their judgment shifts to intent-based (e.g., Costanzo, Coie, Grumet, & Farnill, 1973; Miller & McCann, 1979; Wellman, Larkey, & Somerville, 1979; Yuill & Perner, 1988; Zelazo, Helwig, & Lau, 1996).

Moral reasoning based on the valence of intention (prosocial or antisocial) is considered a fundamental component of mature morality. However, several studies suggested young children under four years of age are sensitive to intent information when stimuli are simple and controlled to exclude confounding factors (Armsby, 1971, Behne, Carpenter, Call, & Tomasello, 2005; Chernyak & Sobel, 2016). Ample findings also indicate that infants show sensitivity to both behavior/intention and outcome (Campos, 1983; Chiarella & Poulin-Dubois, 2013; Hamlin, 2013; Hamlin, Ullman, Tenenbaum, Goodman, & Baker, 2013; Hamlin & Wynn, 2011; Hamlin, Wynn, & Bloom, 2007, 2010; Holvoet, Scola, Arciszewski, & Picard, 2016; Kanakogi, Okumura, Inoue, Kitazaki, & Itakura, 2013; Lee, Yun, Kim, & Song, 2015; Margoni & Surian, 2018; Skerry & Spelke, 2014; Woo, Steckler, Le, & Hamlin, 2017). Hamlin and colleagues used preferential reaching or preferential looking as indicators and demonstrated that children in their first year of life showed a preference to the helper or an aversion to the hinderer (Hamlin & Wynn, 2011; Hamlin et al., 2007, 2010). Woo, Steckler, Le, and Hamlin (2017) also indicated that 10-month-olds preferred intentional helper over accidental helper, and accidental harmer over intentional harmer. Regarding sensitivity to the outcome, Kanakogi et al. (2013) reported that 10-month-old infants showed a preference for the victim of antisocial behavior, suggesting that they understand the outcomes of moral behaviors and displayed empathy for recipients.

Adults also integrate valences of both behavior/intention and outcome when making moral judgments (e.g., Berg-Cross, 1975; Cowell et al., 2017; Cushman, 2008; Kurdi, Krosch, & Ferguson, 2020; Mazzocco, Alicke, & Davis, 2004; Young, Cushman, Hauser, & Saxe, 2007). For example, Cushman (2008) demonstrated that adult participants relied on both the mental states of agent and outcomes (recipients’ reactions) when making judgments of blame and punishment. Kurdi et al. (2020) also reported the integration of intention and outcome information in adults’ implicit moral evaluation measured by an Implicit Association Test.

All these results indicate that the integration of valences between behavior/intention and outcome information in moral judgments are shown across the life course. However, it is unclear whether children show a similar integration pattern across cultures (Jensen et al., 2014). Although previous evidence suggests that there are cultural variations in the various aspects of sociomoral development (see Tomasello & Vaish, 2013), cross-cultural investigations on the development of moral judgments have been mostly limited to the investigation of middle childhood. Therefore, whether and how the developmental patterns of moral judgments vary across cultures among young children remains unclear. Moreover, the process underlying the integration of behavior/intention and outcome information is still poorly understood. The current study thus focused on cultural similarities and differences in the implicit and explicit integration of behavior/intention and outcome of young children’s moral judgments.

Culture and the development of moral judgment

Culture shapes how we encode and interpret behaviors, mental states, environments, customs, and more. Cultural psychology suggested that there are systematic cultural differences in how people attend to social information and draw meanings from encoded information (Henrich, 2015; Kitayama & Salvador, 2017; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). One of the main theoretical frameworks is the analytic vs. holistic thinking style; Westerners, such as North Americans, are characterized to have an analytic thinking style, decontextualizing a focal object and person from the situation. In contrast, East Asians, such as Japanese, Chinese, and Koreans, are characterized to have a holistic cognitive style, paying attention to the relationship between focal objects and their contexts (Fiske, Kitayama, Markus, & Nisbett, 1998; Miller, 1984; Morris & Peng, 1994). Another theoretical framework is the independent vs. interdependent self-construal (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, 2010; Varnum, Grossman, Kitayama, & Nisbett, 2010). Westerners are likely to hold an independent self-construal, emphasizing individual needs and attributes; while East Asians are likely to hold an interdependent self-construal, placing a stronger emphasis on maintaining relational harmony and obeying social expectations and norms (Rothbaum, Pott, Azuma, Miyake, & Weisz, 2000). Consistent with these frameworks, empirical evidence suggested that Americans are more likely than Asians to attribute behavior to internal traits, whereas Asians are more likely than North Americans to consider both disposition and situation information into their attributions (Fiske et al., 1998; Miller, 1984; Morris & Peng, 1994; Nisbett et al., 2001; Shimizu, Lee, & Uleman, 2017). Developmental investigations demonstrated that, when asked to make causal attributions of others, Hindu participants showed a high rate of situational attributions both among children and adults, whereas Americans were increasingly likely to make dispositional attributions as they age (Miller, 1984). Further, cross-cultural research of emotion recognition suggests that, when judging the emotion of a central person, Japanese people are more likely than European Americans to consider the emotions of people in the background (Masuda et al., 2008; Masuda, Wang, Ishii, & Ito, 2012; Matsumoto, Hwang, & Yamada, 2012; Miyamoto & Ryff, 2011).

The culturally unique styles of causal trait attribution and emotion recognition are mirrored in divergent socialization practices (Tomasello & Vaish, 2013). American mothers are more likely than Japanese counterparts to attribute children’s performance to their ability, whereas Japanese mothers are more likely to focus on effort (Hess et al., 1986; Holloway, 1988). A recent study by Shimizu, Senzaki, and Uleman (2018) reported that European American mothers, compared to their Japanese counterparts, made socially evaluative references more frequently such as “kind,” “mean,” “good,” and “bad” in their infant-directed speech. Regarding emotion recognition, when discussing emotional events with their 3-year-old children, American mothers were more likely to focus on personal themes as causes of individual emotion experiences of children (e.g., winning a race or losing a toy), whereas Chinese mothers were more likely to center social and relational themes (e.g., being visited by a friend or being scolded by an adult). Other evidence suggests that American children tend to be encouraged to focus on their own emotions, while Chinese children tend to be encouraged to be attuned to others’ emotions (Azuma, 1994; Wang & Leichtman, 2000). All these empirical findings suggest that Western children are more likely to be socialized to focus on internal traits than Asian children, while Asian children are more likely to be socialized to consider others’ emotions than Western children.

Of interest is how and when these cultural variations in social cognition emerge in the developmental process of moral judgments. So far, a substantial body of cross-cultural research on the development of moral judgment has reported West–East differences (Chiu Loke, Heyman, Itakura, Toriyama, & Lee, 2014; Fu, Xu, Cameron, Leyman, & Lee, 2007; Heyman, Itakura, & Kang, 2011; Taylor, Ogawa, & Wilson, 2002). For example, Chiu Loke et al. (2014) compared Japanese and American 7-, 9-, and 11-year-olds on the reporting of peers’ transgressions to authorities, suggesting that Japanese children tended to consider it more appropriate to report minor transgressions than their American counterparts did. Another line of research documenting cultural differences focused on the evaluation of lying and truth-telling (Cameron, Lau, Fu, & Lee, 2012; Fu et al., 2007; Heyman et al., 2011). Fu et al. (2007), for example, compared Canadian and Chinese 7-, 9-, and 11-year-olds regarding individual- or collective-oriented lies and truths. They demonstrated that Chinese children rated lying aimed at helping a group but harming an individual less negatively than did Canadian children. These cultural variations seem to be consistent with the aforementioned frameworks of West–East comparison in thinking style and social orientation.

However, cross-cultural research on the development of moral judgments has been mostly limited to the investigation of middle childhood and what has received less attention is how developmental patterns may vary across cultures among young children. Shimizu et al. (2018) compared the moral evaluations of Japanese and European American infants aged 6- to 18-months and found no cultural differences in the dishabituation to inconsistent moral behavior and in their preferential reaching for prosocial over antisocial agents. Although this research demonstrated that preverbal infants show culturally similar behaviors, it remains unclear when and how cultural variations emerge. To address this gap, we investigated similarities and differences in the development of implicit and explicit moral judgments between European American and Japanese young children.

Implicit and explicit moral understanding

Another focus of this study was on measuring implicit process of moral judgments and investigating its association with explicit processes. Research on the development of social cognition has frequently suggested that, long before children become able to explain verbally about the mental cause of others’ behaviors, they have an implicit understanding of others (e.g., Behne, Carpenter, Call, & Tomasello, 2005; Fawcett & Gredebäck, 2013; Gerson & Woodward, 2014; Uithol & Paulus, 2014). Recently, there have been some attempts to explore the association between the implicit and explicit moral understanding among preschool children (Smetana, Ball, Jambon, & Yoo, 2018; Van de Vondervoort & Hamlin, 2017). For instance, Smetana et al. (2018) investigated associations between preference for and verbal evaluations of a moral and a conventional transgressor among 2- to 5-year-olds. They found that children’s preferences were associated with their evaluations. However, it is still poorly understood what processes are involved in children’s moral judgments. Traditionally, it has been considered that children gradually develop their ability of deliberative moral reasoning (Kohlberg, 1976; Piaget, 1932), and the investigations of children’s moral understanding have focused on their explicit verbal responses. A representative example is Kohlberg’s studies, which presented children with moral dilemma scenarios and asked them to explain how they would reason for their judgments. The studies that investigated the shift from outcome- to intention-based judgments also asked children to verbally explain their reasoning processes (e.g., “Do you know why [agent] hit her?”).

In contrast, recent arguments of adults’ moral judgment have suggested that implicit, automatic, and intuitive information processing is an integral part of moral reasoning (Greene & Haidt, 2002; Haidt, 2001). Since it is sometimes difficult to recognize the own processing of intuitive judgments (Greene & Haidt 2002), researchers have sometimes employed an eye-tracking paradigm to tap the mechanisms behind moral intuitions. In particular, previous investigations using an eye-tracking paradigm suggested that visual encoding plays an important role in moral judgments. For instance, Decety, Michalska, & Kinzler (2011) measured participants’ attention using an eye-tracker while they were watching the stimuli depicting moral violations, and found that the participants allocated more attention to the victims of harmful act than to the agents who caused this harm, indicating that they showed empathic concerns to the victims. Garon, Lavallee, Estay, and Beauchamp (2018) also measured participants’ visual fixations on the social cues in the moral dilemma scenes and found that attention to the social cues predicted moral justification.

Investigating the visual encoding of moral scenes and its relationship with explicit evaluation has multiple implications to unveil the developmental process of sociomoral understanding. Asking children to explain their reasoning process is sometimes not appropriate, especially for young children, because they lack the mature verbal ability to fully explain their reasoning processes. Actually, it is sometimes difficult even for adults to introspect and verbalize implicit and automatic mental processing (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). Implicit and nonverbal assessment such as gaze fixations is also useful to examine cultural differences because language differences are less likely to affect the measurements. So far, a substantial body of research has applied the implicit measures such as eye movements and neural activities to explore the cognitive processes of social cognition among children (e.g., Brownell, Lemerise, Pelphrey, & Roisman, 2015; Holvoet, Scola, Arciszewski, & Picard, 2017). However, few studies have investigated the implicit attention process of young children in moral judgment using an eye-tracking paradigm, especially in cross-cultural investigations. Thus, we measured children’s visual attention while observing moral scenes using an eye-tracking paradigm to investigate their implicit encoding of sociomoral events. We also explored the association between implicit visual attention and explicit verbal evaluation.

The current study

This study was designed to investigate cultural influences on the development of sociomoral understanding. Specifically, we investigated the similarities and differences in both implicit visual encoding of sociomoral events and explicit verbal sociomoral evaluations between European American and Japanese three- and four-year-old. How implicit and explicit moral understandings are associated was also of interest. We used an eye-tracker to determine what components of sociomoral scenarios children were more likely to focus their attention on. Specifically, children’s visual fixation on the agent and the recipient in the sociomoral event were measured to investigate how they implicitly integrated agents’ intention and recipients’ emotional outcome, and whether the implicit visual encoding was associated with explicit verbal evaluation. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to use an eye-tracking paradigm in cross-cultural investigations of young children’s sociomoral development.

Children were shown six simple sociomoral stories that included behavior and outcome information. Similar to previous studies investigating moral evaluations of young children under 4 years of age and infants (e.g., Cowell & Decety, 2015; Hamlin & Wynn, 2011; Hamlin, Wynn, & Bloom, 2007, 2010; Van de Vondervoort & Hamlin, 2017), we simply displayed two types of behaviors (positive and negative) that reflected prosocial or antisocial intentions of agents. The outcome was displayed as recipients’ emotional reaction, following previous studies (e.g., Heyman & Gelman, 1998; Yuill & Perner, 1998; Zelazo et al., 1996). In the congruent event, an agent engaged in either prosocial or antisocial behavior and a recipient exhibited a congruent emotion (i.e., agent’s prosocial action and recipient’s happy emotion, or agent’s antisocial action and recipient’s sad emotion). In the incongruent event, when the agent engaged in a prosocial behavior, the recipient demonstrated a sad emotion; and when the agent engaged in an antisocial behavior, the recipient demonstrated a happy emotion. While the children were watching the stories, their visual attention was measured using an eye-tracker to determine what component (the agent vs. the recipient) received more attention. Children were then asked to verbally evaluate the agents’ sociomoral traits after seeing each scenario. If children pay more attention to the recipient when behavior and outcome is incongruent than when behavior and outcome is congruent, it would indicate that they anticipated the recipient’s reaction based on the valence of behavior. In addition, if children’s evaluation of agent’s moral trait changed depending on the outcome as well as the behavior, it would indicate that children tried to integrate the outcome and behavior information in their moral judgment.

Given that Asian children are more likely to be socialized to consider others’ emotions than are Western children (Azuma, 1994; Wang & Leichtman, 2000), and European American children are exposed to morally evaluative speech of mothers more frequently than are Japanese children from infancy (Shimizu et al., 2018), we proposed two hypotheses. First, we expected that, compared to European American children, Japanese children would focus more on the recipients’ emotion than agents’ behavior in both implicit and explicit sociomoral integrations. Second, European American young children would develop the ability to verbally evaluate the agent based on its prosocial or antisocial behaviors earlier than would Japanese young children.

Method

Participants

The participants comprised 78 Japanese children and 63 European American children. The Japanese sample included a group of three-year-olds (n = 38, 15 girls and 23 boys; M = 40.84 months, SD = 3.52 months, range = 35 to 47 months) and a group of four-year-olds (n = 40, 17 girls and 23 boys; M = 53.08 months, SD = 3.36 months, range = 48 to 59 months). The European American sample also included a group of three-year-olds (n = 33, 16 girls and 17 boys; M = 42.50 months, SD = 3.79 months, range = 34 to 47 months) and a group of four-year-olds (n = 30, 12 girls and 18 boys; M = 52.77 months, SD = 3.58 months, range = 48 to 59 months). An a priori power analysis using G*Power (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007), with effect size specification as in Cohen (1988), indicated that a sample of 48 participants (i.e., 12 per age-culture group) would be sufficient to detect a medium effect with power (1 - β) set at 0.80 and α = .05.1 Additional participants were excluded from data analyses because of insufficient looking time (less than 50% of the demonstration; eight Japanese and seven Americans), failure to answer the comprehension question correctly (see below in the scenario comprehension section; nine Japanese and seven Americans), or failure of the eye-tracker (two Japanese and one American).

The Japanese data were collected in a suburban area in Japan, and European American data were collected in a suburban area in the U.S. No significant difference was found in children’s parents’ education level between the two culture groups (for 82.1% of Japanese and 76.7% of European Americans, at least one parent had a college degree; χ2 = 0.40, p = .53). Written informed consent was provided by children’s parents. All procedures involving human participants in this study were approved by the ethics committees of Saitama University and University of Wisconsin-Green Bay where the project was conducted.

Stimuli

We created six different story themes in which two animals (e.g., an elephant and a monkey) or two shapes (e.g., a circle and a triangle with hands, feet, and eyes) interacted with each other. In each story, an agent performed either a positive (prosocial) or a negative (antisocial) behavior resulting in one of three different outcomes (happy, neutral, or sad), which was shown by the recipients’ emotional reaction. The neutral outcome was included as a baseline for the comparison to examine the effect of positive and negative outcomes.

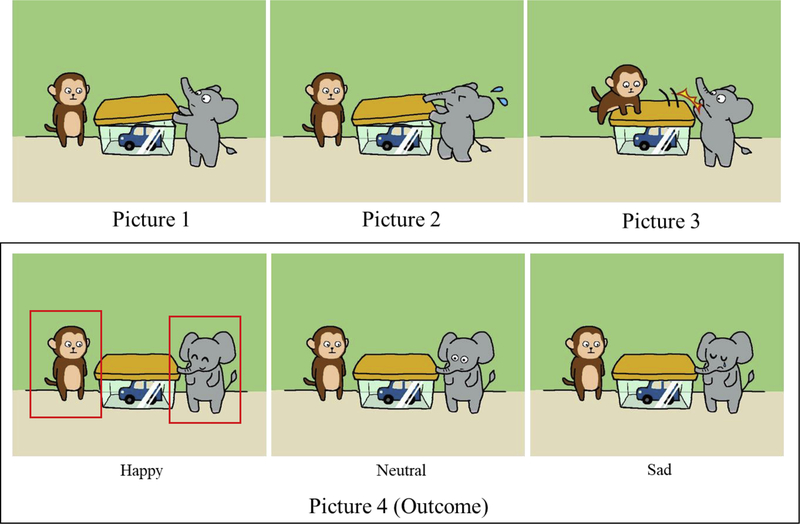

Each story consisted of four colorfully illustrated pictures. Each picture was presented for 15 s; therefore, the total duration of each story was 60 s. The accompanying story was narrated by a pre-recorded female voice in participants’ first language (Japanese or English). For example, the pictures illustrated in Figure 1 had the following narration: Picture 1) the elephant (recipient) was trying to open the box to get a toy, and the monkey (agent) was watching it; Picture 2) the elephant was trying over and over again; but he could not open the box; Picture 3) then, the monkey jumped on the lid of the box, slamming it shut; and Picture 4) the elephant could not get the toy from the box. The other storylines are shown in Table 1. The outcome was shown only by recipients’ facial expression, as depicted in the fourth picture and was not included in narrations. When the outcome was happy, the recipient was shown with a pleased expression. When it was sad, the recipient was shown with a displeased expression. When it was neutral, the recipient did not show any specific emotional expression.

Figure 1.

Sample of stimuli (negative behavior)

Table 1.

Storylines of six sociomoral scenarios

| Story | Picture | Narration |

|---|---|---|

| Positive behavior 1 | 1 | The elephant wanted to get a toy from the box, and the elephant was trying to open the box. The monkey was watching. |

| 2 | The elephant was trying over and over again; but the elephant could not open it because the lid was too heavy. | |

| 3 | Then the monkey opened the box together with the elephant. | |

| 4 | The elephant could get the toy from the box. | |

| Positive behavior 2 | 1 | The triangle was trying to climb up the hill. |

| 2 | The triangle was trying to climb up again and again; but the triangle could not do it. | |

| 3 | Then, the square pushed the triangle up from below. | |

| 4 | The triangle could climb up to the top of the hill. | |

| Positive behavior 3 | 1 | The pig was walking on the street. |

| 2 | The pig fell in a puddle and got wet. | |

| 3 | Then the rabbit dried the pig’s body with a towel. | |

| 4 | The pig’s body got dry and clean. | |

| Negative behavior 1 | 1 | The elephant wanted to get a toy from the box, and the elephant was trying to open the box. The monkey was watching. |

| 2 | The elephant was trying over and over again; but the elephant could not open it because the lid was too heavy. | |

| 3 | Then the monkey jumped on the lid of the box, slamming it shut. | |

| 4 | The elephant could not get the toy from the box. | |

| Negative behavior 2 | 1 | The triangle was trying to climb up the hill. The circle was watching. |

| 2 | The triangle was trying to climb up again and again; but the triangle could not do it. | |

| 3 | Then the circle pushed the triangle down from above. | |

| 4 | The triangle fell down to the bottom of the hill. | |

| Negative behavior 3 | 1 | The cat was walking on the street. |

| 2 | The hippo was holding a hose. | |

| 3 | Then the hippo splashed water on the cat with the hose. | |

| 4 | The cat got wet. | |

Procedure

The stimuli were presented on a 17-inch laptop computer. Participants sat on a chair at a distance of approximately 65 cm from the monitor. Each participant was presented with all six stories systematically varying in behavior (positive or negative) and outcome (happy, sad, or neutral). In total, there were four patterns of presentation, which differed in the matching of story theme, event type, and order; and each participant was randomly assigned to a pattern. Preliminary analyses revealed that the pattern of presentation did not significantly influence participants’ responses. The stories and questions were first created in Japanese and then translated into English by a researcher who was fluent in both languages. The English materials were then back-translated into Japanese by a professional translator to ensure the Japanese and English versions were equivalent.

Participants’ attention to agents and recipients while presented with each story were recorded using Tobii Pro X3–120 (Tobii technology, Sweden); and the eye-tracking data were collected at a sample rate of 120 Hz, at a resolution of 1,920 × 1,080 pixels. First, a five-point calibration was performed using Tobii Studio software. The calibration procedure was repeated until the calibration was considered successful. Then, the stories were presented. Before the first story was presented, children were told by the experimenter that they would be shown some stories and asked some questions. To quantify gaze fixations, we drew areas of interest (AOIs) encompassing the areas surrounding the agent and recipient in the fourth picture in each story, at a consistent size of 15 cm × 10 cm (see Picture 4, happy outcome in Figure 1, for one example). We measured the fixation duration to each of AOIs.

After seeing each story, the children were presented with the four pictures, simultaneously, that they had seen in the story and answered questions that evaluated the agent. Given that young children can understand and use trait labels for inductive reasoning (Heyman & Gelman, 1999, 2000) but rarely use personality traits spontaneously when describing others (Livesley & Bromley, 1973), we used a multi-level scale approach, following previous studies (e.g., Heyman & Gelman, 1998; Nobes, Panagiotaki, & Engelhardt, 2017; Zelazo et al., 1996). First, they were asked, “What kind of person is the [agent]?” If participants’ answers did not indicate either a positive trait (“good,” “kind,” “great,” or “helpful”), negative trait (“bad” or “mean”), or “neither,” they were further asked, “Do you think the [agent] is nice or mean?” If the child could not understand “nice” and/or “mean,” they were asked again, “Do you think [agent] is good or bad?” The children were then asked, “Do you think the [agent] is very nice (mean) or a little nice (mean)?” The orders of “nice” and “mean” or “very” and “a little” were counterbalanced within each participant across the six stories. Responses were coded from 1 (very mean) to 5 (very nice).

Scenario comprehension

As a rule-check and comprehension metric, at the end of the session; i.e., only for the final story, two comprehension questions were added to ensure that each child understood and remembered the story correctly. The questions concerned agents’ behavior (“Do you remember what [agent] did to [recipient]?”) and outcome (“How do you think [recipient] feels?”). The reason the comprehension questions were added only for the final story was to avoid enhancing children to focus on the specific information in the later scenarios. The percentages of children who answered the two comprehension questions correctly in the final (sixth) story were 86.8% of three-year-olds and 90.0% of four-year-olds for the Japanese sample and 84.8% of three-year-olds and 93.3% of four-year-olds for the European American sample. No significant difference was found in the accuracy rate between the two culture groups (3-year-olds, χ2 = 0.72, p = .79; 4-year-olds, χ2 = 0.12, p = .73). These results on accuracy rates indicate that most three- and four-year-old children in both cultures correctly understood and memorized the sociomoral events presented and both culture groups were similar in their ability to understand stories. Participants who answered the comprehension question incorrectly were excluded from analyses (see above in the Participants section). There were no main or interaction effects for children’sex; therefore, the data were collapsed across sex for analyses.

Results

Attention

Preliminary analysis.

The mean of total fixation duration (seconds) to whole area of the fourth picture across the six stories did not differ between the two cultures (t(139) = 0.70, p = .484, Cohen’s d = 0.12; Japanese M = 11.68, SD = 1.51, American M = 11.87, SD = 1.68) or between the two age groups (t(139) = 0.47, p = .639, Cohen’s d = 1.05; three-year-olds M = 11.83, SD = 1.56, four-year-olds M = 11.71, SD = 0.08). We also examined whether there were differences between cultures and ages in the fixation duration to the areas other than two AOIs in the fourth picture (i.e. the fixation duration to whole area minus that to AOIs of the agent and recipient). The results showed no difference between the two cultures (t(139) = 1.17, p = .243, Cohen’s d = 0.20; Japanese M = 2.11, SD = 1.95, American M = 1.75, SD = 1.63) or between the two age groups (t(139) = 0.87, p = .384, Cohen’s d = 0.15; three-year-olds M = 1.81, SD = 1.45, four-year-olds M = 2.08, SD = 2.12).

The means of the fixation duration to each of AOIs (seconds) were then entered into a 2 (Culture: Japanese and European American) × 2 (Target AOI: agent and recipient) factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results demonstrated only a main effect of Target, F(1, 139) = 1,005.73, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.88). Overall, recipients (M = 6.52, SD = 1.33) were viewed for twice as long as agents (M = 3.28, SD = 0.84). The main effect of Culture and the Culture × Target interaction were not significant, F(1, 139) = 1.34, p = .25, ηp2 = 0.01, F(1, 139) = 0.09, p = .761, ηp2 = 0.00, respectively.

Attentional bias to recipients against agents.

To investigate the differences in visual attention allocation to the scenarios, the total fixation duration to the AOI of the agent was subtracted from that of the recipient for each story; thus, the larger value indicates an attentional bias to the recipients against the agents (shown in Figure 2)2. This difference value was entered into a 2 (Culture) × 2 (Age: three-year-olds and four-year-olds) × 2 (Behavior: positive and negative) × 3 (Outcome: happy, neutral, and sad reaction) mixed ANOVA, with culture and age as between-participants factors and behavior and outcome as within-participants factors. The results indicated a significant main effect of Outcome, F(2, 137) = 3.40, p = .035, ηp2 = 0.02, and Behavior × Outcome interaction, F(2, 137) = 54.90, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.29. In both the negative and positive behavior events, the attentional bias differed among the three outcome events (negative behavior: happy reaction event M = 4.55, SD = 2.82, neutral reaction event M = 3.22, SD = 2.88, sad reaction event M = 2.21, SD = 3.42; positive behavior: happy reaction event M = 1.42, SD = 2.93, neutral reaction event M = 3.07, SD = 2.76, sad reaction event M = 4.97, SD = 3.24; all pairwise comparisons ps < .05, Bonferroni).

Figure 2.

Attentional bias to recipient against agent (fixation duration to recipient minus that to agent). Error bars show standard errors.

These results indicate that, among both cultures, children showed stronger attentional bias to the recipient over the agent when the valence of the behavior and the outcome was incongruent (i.e., positive behavior – sad reaction, negative behavior – happy reaction) than when the valence of the behavior and the outcome was congruent (i.e., positive behavior – happy reaction, negative behavior – sad reaction) or when the outcome was neutral. In contrast, the attentional bias to the recipient over the agent was weaker when the valence of the behavior and the outcome was congruent than when the valence of the behavior and the outcome was incongruent or when the outcome was neutral. No other main effects or interactions were significant, Fs < 1.00.

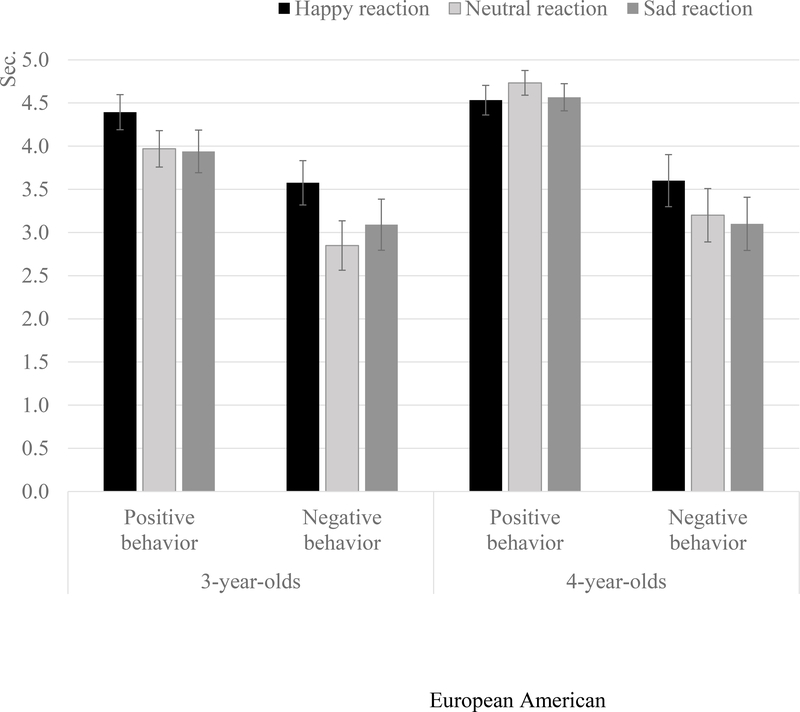

Verbal moral evaluation

Verbal moral evaluation scores reflect participants’ responses when asked the extent to which the agents were nice or mean (1: very mean to 5: very nice). The means of verbal evaluation in each culture group are shown in Figure 2. A 2 (Culture) × 2 (Age) × 2 (Behavior) × 3 (Outcome) mixed ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of Behavior, F(1, 137) = 89.69, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.40. This main effect was qualified by significant interaction effects of Age × Behavior, F(1, 137) = 15.35, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.10, and Culture × Age × Behavior, F(1, 137) = 5.30, p = .023, ηp2 = 0.04. We then conducted a 2(Age) × 2(Behavior) ANOVA for each culture. Results revealed that the Age × Behavior interaction was significant among Japanese, F(1, 76) = 20.50, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.21, but not European Americans, F(1, 61) = 1.27, p = .026, ηp2 = 0.02. Further analyses showed that, among European Americans, the difference in evaluations between positive and negative behaviors was significant both for three- and four-year-olds (t(32) = 3.76, p = .001, Cohen’s d = 0.65; t(29) = 5.75, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.05, respectively); however, among Japanese, the difference was significant only for four-year-olds, t(39) = 9.40, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.49, and not for three-year-olds, t(37) = 1.47, p = 0.151, Cohen’s d = 0.24.

The main effect of Outcome and the Behavior × Outcome interaction were also significant, F(2, 137) = 5.76, p = .004, ηp2 = 0.04; F(2, 137) = 4.94, p = .008, ηp2 = 0.04, respectively. The simple main effect of Outcome was significant for the negative behavior event, F(2, 137) = 7.44, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.05, but not for the positive behavior event, F(2, 137) = 0.30, p = .744, ηp2 = 0.00. In the negative behavior event, the trait evaluation of agent in the happy reaction event (M = 3.56, SD = 1.58) was more positive than that in the neutral reaction event (M = 2.94, SD = 1.66) and that in the sad reaction event (M = 3.16, SD = 1.71; all pairwise comparisons ps > .05, Bonferroni). No other main effects or interactions were significant, Fs < 1.00.

Relationship between visual attention and verbal responses

We then investigated whether the explicit verbal evaluation was associated with the implicit attentional bias to the recipient (relative to the agent) especially when the valence of the behavior and the outcome was congruent or incongruent. We analyzed the bivariate correlation between the attentional bias score and the trait evaluation score. The results showed that only among American four-year-olds, attention bias was positively correlated with trait evaluation when agents’ behavior was negative but recipients’ reaction was happy, r(28) = .38, p = .039. No other correlations were significant (rs <.27, ps > .13).

Discussion

The current study investigated cultural similarities and differences among three- to four-year-old children in the development of sociomoral judgments. We specifically examined the integration of information on emotional outcome versus observed behavior in both visual fixation/attention and verbal evaluations of the agent in sociomoral scenarios. Our results suggested that three- to four-year-old children were sensitive to the relationship between the emotional outcome and the observed behavior, that there were both cultural similarities and differences in the development of these integrations, and that there was little link between implicit attention to the components in the scenarios and explicit verbal judgments of agents.

We found culturally similar tendencies among young children in both implicit and explicit processes of the integration of behavior and emotional outcome. Generally, children from both Japan and the U.S. paid more visual attention to the recipient than the actor. The attentional bias while observing the sociomoral scenes has been reported in previous studies with infants and toddlers as well as adults (e.g., Cowell & Decety, 2015; Decety, Michalsk, & Kinzler, 2011; Skulmowski, Bunge, Kaspar, & Piga, 2014). For example, Decety et al. (2011) observed a longer fixation duration on the victims of wrongdoing. In the current study, the attention bias to the recipient was found to be greater especially when the valence of outcome was incongruent with that of behavior (i.e., positive behavior – sad reaction, negative behavior – happy reaction). This suggests that children anticipated recipients’ emotional reaction based on the valence of agents’ behavior, indicating that they have already had understanding of the relationship between sociomoral behavior and its outcome. Cultural similarity was also shown in their verbal evaluations. Children from both cultures evaluated the agent who demonstrated negative behavior more positively when the recipients’ reaction was happy than when the reaction was neutral or sad. Therefore, our first hypothesis, that Japanese children would be more sensitive to the recipients’ emotions than European American children, was not supported. Given that adults and infants also consider both behavior/intention and outcome in their moral judgments (e.g., Campos, 1983; Chiarella & Poulin-Dubois, 2013; Cushman, 2008; Hamlin, 2013; Hepach & Westermann, 2013; Kurdi et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2015; Young et al., 2007), the sensitivity to the outcome as well as the intention is universal and dominates moral computations for human beings.

The influence of the outcome on verbal moral evaluation was only observed for negative behavior events and not for positive behavior events in both cultures. One possible explanation is children’s positivity bias, which makes them more likely to evaluate others positively. Children’s overall mean of sociomoral trait evaluation against prosocial agents was 4.34 and that against antisocial agents was 3.22, meaning that, even for antisocial agents, their evaluation was beyond the midpoint (i.e., 3.0). The positivity bias in young children’s evaluations of others’ sociomoral traits has been reported repeatedly (Boseovski, 2010; Boseovski, Shallwani, & Lee, 2009; Heyman & Giles, 2004; Rholes & Ruble, 1984; Shimizu, 2000). Evidence suggests that children tend to make positive trait attributions even when they observed the agent’s positive behavior only once, while they are reluctant to make negative trait attribution on the basis of a single negative behavior (Rholes & Ruble, 1984). Therefore, children in this study may have evaluated the antisocial agent positively when the positive outcome was included, whereas they were reluctant to evaluate prosocial agent negatively even when the negative outcome was included. It is also possible that the children’s positivity bias was reflected in their inference of the agents’ intention: children might tend to infer less negative intention of agents when the antisocial behavior causes positive outcome, whereas they might tend to consider that the prosocial behavior was always caused by positive intention regardless of outcome. However, this positive-negative asymmetry was not observed in their visual encoding of the moral scenes. Therefore, it may be that the positivity bias observed in young children’s moral trait evaluation is caused not because children ignore the negative information but because they avoid evaluating other’s trait or intention negatively.

As predicted, a cultural difference was shown in children’s explicit verbal evaluations. Among European Americans, both three- and four-year-olds inferred that the agent who behaved prosocially had more positive sociomoral traits than the agent who behaved antisocially; while, among Japanese children, this tendency appeared only for four-year-olds but not for three-year-olds. This result is consistent with previous findings in cultural psychology that Western people are more likely to attribute personality trait as a cause of observed behavior than Eastern people (Fiske et al., 1998; Miller, 1984; Morris & Peng, 1994; Nisbett, 2003). The current evidence, from the developmental perspective, raised the possibility that cultural variations in verbal trait attributions emerge in early young childhood.

Another purpose of the current study was to examine the association between implicit visual attention and explicit verbal evaluation of moral judgment. We analyzed correlations between the attention bias to the recipient over the agent in the sociomoral scenario and the degree of positivity in verbal evaluations of the agent. Results indicated that, only among four-year-olds, the attention bias was positively correlated with the trait evaluation only when agents’ behavior was negative but recipients’ reaction was happy, but no other correlations were significant. Given that the correlation was weak and the number of each cell in the correlation analysis was small (40 at most), it seems that the overall relationship between implicit attention and explicit verbal evaluation was negligible.

The little link between implicit and explicit measures was also indicated by the results of cultural differences: there was no cross-cultural difference in implicit visual attention to the moral scenes, while explicit moral evaluation differed between two cultures. How can these results be interpreted? One possibility is that cultural meanings are embedded not in the process of encoding information of the sociomoral scenes but in the process of interpreting the encoded information. Perhaps the implicit encoding process reflects intuitive processing of moral judgments (e.g., Garon et al., 2018; Haidt, 2001), and therefore is universally shown across cultures. In contrast, explicit moral evaluations measured by verbal responses may reflect processes of culture-specific interpretations and expressions. Culture is shared knowledge, values, beliefs, and expectations among a member of social network. Since culture is embedded in the language (Kashima, Kashima, Kim, & Gelfand, 2006), parent–child verbal interactions play a key role in cultural transmissions (Bruner, 1990; Hess et al., 1986; Rothbaum et al., 2000). Previous studies comparing parental speech to children between Western and Eastern cultures suggested that children are exposed to culturally influenced speech from the first year of life (Fernald & Morikawa, 1993; Little, Carver, & Legare, 2016; Rothbaum et al., 2000; Shimizu et al., 2018). It may be that, through their experiences of adults repeatedly labeling the actors with moral traits, European American young children develop the ability to evaluate others verbally relatively earlier than Japanese counterparts.

Culture should affect not only how to interpret but also how to express the encoded information. Evidence suggest that Asians tend to avoid judging others explicitly to maintain relational harmony (Rothbaum et al., 2000). Given that, it is possible that Japanese children, compared to European American children, were reluctant to label others with explicit moral traits even if they had both implicit and explicit sociomoral understanding. In contrast, given the finding that European American children have more opportunities than their Japanese counterparts to hear morally evaluative trait words spoken by their parents from infancy (Shimizu et al., 2018), European American children might be used to describe others explicitly using moral trait labels. It is critical for future work to explore what process in moral judgments culture influences and how culturally unique patterns of sociomoral judgment emerge and are socialized. This should be accomplished using combined implicit indicators such as neurological activities and including in older age groups.

By measuring both implicit visual attention and explicit verbal evaluation, our findings provide new evidence regarding cultural similarities and differences in the early inclusion of emotional outcome and observed action in sociomoral evaluations among young children younger than five years of age. Our results are also informative for the debate on how implicit measures are useful for the developmental and cultural studies (e.g., Onishi & Baillargeon, 2005, Fazio & Olson, 2003; Senju et al., 2011; Uithol & Paulus, 2014). The dissociation between visual encoding and verbal implication shown in this study suggests the importance of using implicit measures as well as explicit measures to tap into developmental processes of sociomoral judgments, especially in cross-cultural investigations.

In the past decade, the lack of diversity in psychological research has been highlighted (Arnett, 2008; Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010; Legare & Harris, 2016), and developmental psychological research has also been conducted with unrepresentative populations from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic) backgrounds (Henrich et al., 2010; Nielsen & Haun, 2016; Nielsen, Haun, Karter, & Legare, 2017). Our findings extend this usual group by including children from both the United States and Japan, shedding light on the nature of cultural generalizability and specificity in sociomoral development. It should be noted, however, that to say that children’s moral development is influenced by culture is not to disregard the many additional mediating factors. Past research suggests associations between the development of moral reasoning and cognitive and social abilities such as executive function (Hinnant et al., 2013), empathy (Hoffman, 2000), theory of mind (Baird & Astington, 2004), and parents’ injustice sensitivity (Cowell & Decety, 2015). Investigating the factors behind individual and cultural differences and exploring the interactions between these factors in the development of sociomoral understanding would be a good next step. Additionally, future research would benefit from the inclusion of an increasingly broad sample from various socio-economic statuses and/or cultures.

Figure 3.

Average of verbal evaluation of agents’ traits. Error bars show standard errors.

Highlights.

European American and Japanese 3- to 4-year-olds were compared on the moral judgment

Children watched scenarios varying in behavior and outcome (recipient’s reaction)

Two cultures were similar in the integration of behavior and outcome information

The verbal evaluation of agents’ moral traits developed differently across cultures

The dissociation between implicit encoding and explicit evaluation was shown

Acknowledgments:

We thank Honami Arihara for assistance with developing the materials, and Sayaka Kitada for help with data collection.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to Yuki Shimizu (no. 15KK0075); and a grant by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health, awarded to Sawa Senzaki and Jason M. Cowell (no. R15HD094138)

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None

However, we considered that it was necessary to collect more samples since we expected that a certain number of participants will be dropped owing to failure to answer the comprehension question correctly or problems with the eye-tracking process (e.g., insufficient looking time, or failure of the eye-tracker).

We also calculated a proportion score limiting the time to only gazes at the actor and recipient, i.e., recipient / (recipient + actor). Children from all groups of culture and age showed a higher proportion score against chance level (0.5) (ts > 6.0, p < .001), indicating that children showed attentional bias to recipients against agents regardless of culture and age.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Armsby RE (1971). A reexamination of the development of moral judgments in children. Child Development, 42(4), 1241–1248. doi: 10.2307/1127807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2008). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist, 63(7), 602–614. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma H (1994). Two modes of cognitive socialization in Japan and the United States In Greeneld PM & Cocking RR (Eds.), Cross-cultural roots of minority child development (pp. 275–284). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Baird JA, & Astington JW (2004). The role of mental state understanding in the development of moral cognition and moral action. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 103, 37–49. doi: 10.1002/cd.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behne T, Carpenter M, Call J, & Tomasello M (2005). Unwilling versus unable: Infants’ understanding of intentional action. Developmental Psychology, 41(2), 328–337. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Cross LG (1975). Intentionality, degree of damage, and moral judgments. Child Development, 46(4), 970–974. doi: 10.2307/1128406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boseovski JJ (2010). Evidence for “rose-colored glasses”: An examination of the positivity bias in young children’s personality judgments. Child Development Perspectives, 4(3), 212–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00149.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boseovski JJ, Shallwani S, & Lee K (2009). It’s all good: Children’s personality attributions after repeated success and failure in peer and computer interactions. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27(4), 783–797. doi: 10.1348/026151008X377839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Lemerise EA, Pelphrey KA and Roisman GI (2015). Measuring Socioemotional Development In Lerner RM (Ed.), Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, 3. doi: 10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J (1990). Culture and Human Development: A New Look. Human Development, 33(6), 344–355. doi: 10.1159/000276535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron CA, Lau C, Fu G, & Lee K (2012). Development of children’s moral evaluations of modesty and self-promotion in diverse cultural settings. Journal of Moral Education, 41(1), 61–78. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2011.617414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ (1983). The importance of affective communication in social referencing: A commentary on Feinman. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 29(1), 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chernyak N, & Sobel DM (2016). “But he didn’t mean to do it”: Preschoolers correct punishments imposed on accidental transgressors. Cognitive Development, 39, 13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2016.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarella SS, & Poulin-Dubois D (2013). Cry babies and Pollyannas: Infants can detect unjustified emotional reactions. Infancy, 18(s1), E81–E96. doi: 10.1111/infa.12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Loke I, Heyman GD, Itakura S, Toriyama R, & Lee K (2014). Japanese and American children’s moral evaluations of reporting on transgressions. Developmental Psychology, 50(5), 1520–1531. doi: 10.1037/a0035993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo PR, Coie JD, Grumet JF, & Farnill D (1973). A reexamination of the effects of intent and consequence on children’s moral judgments. Child Development, 44(1), 154–161. doi: 10.2307/1127693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JM, & Decety J (2015). Precursors to morality in development as a complex interplay between neural, socioenvironmental, and behavioral facets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(41), 12657–12662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508832112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell JM, Lee K, Malcolm-Smith S, Selcuk B, Zhou X, & Decety J (2017). The development of generosity and moral cognition across five cultures. Developmental Science, 20, e12403. doi: 10.111/desc.12403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman F (2008). Crime and punishment: Distinguishing the roles of causal and intentional analyses in moral judgment. Cognition, 108(2), 353–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ, & Kinzler KD (2011). The Contribution of Emotion and Cognition to Moral Sensitivity: A Neurodevelopmental Study. Cerebral Cortex, 22(1), 209–220. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, & Buchner A (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett C, & Gredeback G (2013). Infants use social context to bind actions into a collaborative sequence. Developmental Science, 16(6), 841–849. doi: 10.1111/desc.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, & Olson MA (2003). Implicit measures in social cognition. research: their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 297–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, & Morikawa H (1993). Common themes and cultural variations in Japanese and American mothers’ speech to infants. Child Development, 64(3), 637–656. doi: 10.2307/1131208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske AP, Kitayama S, Markus HR, & Nisbett RE (1998). The cultural matrix of social psychology The handbook of social psychology, Vols. 1 and 2 (4th ed.) (pp. 915–981). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Fu G, Xu F, Cameron CA, Leyman G, & Lee K (2007). Cross-cultural differences in children’s choices, categorizations, and evaluations of truths and lies. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 278–293. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garon M, Lavallee MM, Vera Estay E, & Beauchamp MH (2018). Visual encoding of social cues predicts sociomoral reasoning. PLoS One, 13(7), e0201099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerson SA, & Woodward AL (2014). Learning from their own actions: The unique effect of producing actions on infants’ action understanding. Child Development, 85(1), 264–277. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GP (2015). Moral character in person perception. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), 38–44. doi: 10.1177/0963721414550709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, & Haidt J (2002). How (and where) does moral judgment work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6(12), 517–523. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(02)02011-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JK (2013). Failed attempts to help and harm: intention versus outcome in preverbal infants’ social evaluations. Cognition, 128(3), 451–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JK, & Wynn K (2011). Young infants prefer prosocial to antisocial others. Cognitive Development, 26(1), 30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JK, Wynn K, & Bloom P (2007). Social evaluation by preverbal infants. Nature, 450(22), 557–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JK, Wynn K, & Bloom P (2010). Three-month-olds show a negativity bias in their social evaluations. Developmental Science, 13(6), 923–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JK, Ullman T, Tenenbaum J, Goodman N, & Baker C (2013). The mentalistic basis of core social cognition: experiments in preverbal infants and a computational model. Developmental Science, 16(2), 209–226. doi: 10.1111/desc.12017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, & Norenzayan A (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepach R, & Westermann G (2013). Infants’ sensitivity to the congruence of others’ emotions and actions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 115(1), 16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess RD, Azuma H, Kashiwagi K, Dickson WP, Nagano S, Holloway S, … Hatano G (1986). Family influences on school readiness and achievement in Japan and the United States: An overview of a longitudinal study In: Stevenson H, Azuma H, Hakuta K (Eds.), Child development and education in Japan (pp. 147–166). Freeman: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, & Gelman SA (1998). Young children use motive information to make trait inferences. Developmental Psychology, 34(2), 310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, & Gelman SA (1999). The use of trait labels in making psychological inferences. Child Development, 70(3), 604–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, & Gelman SA (2000). Preschool children’s use of trait labels to make inductive inferences. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 77(1), 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, & Giles JW (2004). Valence effects in reasoning about evaluative traits. Merrill Palmer Q (Wayne State Univ Press), 50(1), 86–109. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2004.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GD, Itakura S, & Kang L (2011). Japanese and American children’s reasoning about accepting credit for prosocial behavior. Social Development, 20(1), 171–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnant JB, Nelson JA, O’Brien M, Keane SP, & Calkins SD (2013). The interactive roles of parenting, emotion regulation and executive functioning in moral reasoning during middle childhood. Cognition and Emotion, 27(8), 1460–1468. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.789792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML (2000). Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway SD (1988). Concepts of Ability and Effort in Japan and the United States. Review of Educational Research, 58(3), 327–345. doi: 10.3102/00346543058003327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holvoet C, Scola C, Arciszewski T, & Picard D (2016). Infants’ preference for prosocial behaviors: A literature review. Infant Behavior and Development, 45, 125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holvoet C, Scola C, Arciszewski T, & Picard D (2017). Infants’ social evaluation abilities: testing their preference for prosocial agents at 6, 12 and 18 months with different social scenarios. Early Child Development and Care, 189(6), 1018–1031. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2017.1361415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen K, Vaish A, & Schmidt MFH (2014). The emergence of human prosociality: Aligning with others through feelings, concerns, and norms. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 822. doi: 10.3389/fpsychg.2014.00822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanakogi Y, Okumura Y, Inoue Y, Kitazaki M, & Itakura S (2013). Rudimentary sympathy in preverbal infants: preference for others in distress. PLoS One, 8(6), e65292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima Y, Kashima ES, Kim U, & Gelfand M (2006). Describing the social world: How is a person, a group, and a relationship described in the East and the West? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(3), 388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, & Salvador CE (2017). Culture Embrained: Going Beyond the Nature-Nurture Dichotomy. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 841–854. doi: 10.1177/1745691617707317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg L (1976). Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive development approach In Lickona T (Ed.), Moral development and behavior. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdi B, Krosch AR, & Ferguson MJ (2020). Implicit evaluations of moral agents reflect intent and outcome. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 90. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2020.103990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YE, Yun JE, Kim EY, & Song HJ (2015). The Development of Infants’ Sensitivity to Behavioral Intentions when Inferring Others’ Social Preferences. PloS One, 10(9), e0135588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare CH, & Harris PL (2016). The ontogeny of cultural learning. Child Development, 87(3), 633–642. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little EE, Carver LJ, & Legare CH (2016). Cultural variation in triadic infant–caregiver object exploration. Child Development, 87(4), 1130–1145. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margoni F, & Surian L (2018). Infants’ evaluation of prosocial and antisocial agents: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 54, 1445–1455. doi: 10.1037/dev0000538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033295X.98.2.224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (2010). Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 420–430. doi: 10.1177/1745691610375557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T, Ellsworth PC, Mesquita B, Leu J, Tanida S, & Van de Veerdonk E (2008). Placing the face in context: Cultural differences in the perception of facial emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(3), 365–381. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T, Wang H, Ishii K, & Ito K (2012). Do surrounding figures’ emotions affect judgment of the target figure’s emotion? Comparing the eye-movement patterns of European Canadians, Asian Canadians, Asian international students, and Japanese. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 6, 72. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D, Hwang HS, & Yamada H (2012). Cultural differences in the relative contributions of face and context to judgments of emotions. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(2), 198–218. doi: 10.1177/0022022110387426 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco PJ, Alicke MD, & Davis TL (2004). On the robustness of outcome bias: No constraint by prior culpability. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 26(2–3), 131–146. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2004.9646401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JG (1984). Culture and the development of everyday social explanation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(5), 961–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, & McCann CD (1979). Children’s reactions to the perpetrators and victims of injustices. Child Development, 50(3), 861–868. doi: 10.2307/1128955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, & Ryff CD (2011). Cultural differences in the dialectical and non-dialectical emotional styles and their implications for health. Cognition & Emotion, 25(1), 22–39. doi: 10.1080/02699931003612114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MW, & Peng K (1994). Culture and cause: American and Chinese attributions for social and physical events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 949–971. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.949 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, & Haun D (2016). Why developmental psychology is incomplete without comparative and cross-cultural perspectives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 371(1686), 20150071. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Haun D, Kartner J, & Legare CH (2017). The persistent sampling bias in developmental psychology: A call to action. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 162, 31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE, Peng K, Choi I, & Norenzayan A (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE, & Wilson TD (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84(3), 231–259. 10.1037/0033-295X.84.3.231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nobes G, Panagiotaki G, & Engelhardt PE (2017). The Development of Intention-Based Morality: The Influence of Intention Salience and Recency, Negligence, and Outcome on Children’s and Adults’ Judgments. Developmental Psychology, 53(10), 1895–1911. doi: 10.1037/dev0000380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishi KH, & Baillargeon R (2005). Do 15-month-old infants understand false beliefs? Science, 308(5719), 255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1107621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J (1932). The moral judgment of the child. New York, NY: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rholes WS, & Ruble DN (1984). Children’s understanding of dispositional characteristics of others. Child Development, 55(2), 550–560. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Pott M, Azuma H, Miyake K, & Weisz J (2000). The development of close relationships in Japan and the United States: Paths of symbiotic harmony and generative tension. Child Development, 71(5), 1121–1142. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senju A, Southgate V, Snape C, Leonard M, & Csibra G (2011). Do 18-month-olds really attribute mental states to others? A critical test. Psychological Science, 22(7), 878–880. doi: 10.1177/0956797611411584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y (2000). The development of trait inference in young children: Does 3- to 6-year-old children understand causal relation of trait, motive, and behavior? Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology, 48, 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Lee H, & Uleman JS (2017). Culture as automatic processes for making meaning: Spontaneous trait inferences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 69, 79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2016.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Senzaki S, & Uleman JS (2018). The influence of maternal socialization on infants’ social evaluation in two cultures. Infancy, 23(5), 748–766. doi: 10.1111/infa.12240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skerry AE, & Spelke ES (2014). Preverbal infants identify emotional reactions that are incongruent with goal outcomes. Cognition, 130(2), 204–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Ball CL, Jambon M, & Yoo HN (2018). Are young children’s preferences and evaluations of moral and conventional transgressors associated with domain distinctions in judgments? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 173, 284–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skulmowski A, Bunge A, Kaspar K, Pipa G (2014) Forced-choice decision-making in modified trolley dilemma situations: a virtual reality and eye tracking study. Frontiers in behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SI, Ogawa T, & Wilson J (2002). Moral development of Japanese kindergartners. International Journal of Early Childhood, 34(2), 12–18. doi: 10.1007/bf03176763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov A, Said CP, Engell AD, & Oosterhof NN (2008). Understanding evaluation of faces on social dimensions. Trends in Cognitive Science, 12(12), 455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M, & Vaish A (2013). Origins of human cooperation and morality. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 231–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uithol S, & Paulus M (2014). What do infants understand of others’ action? A theoretical account of early social cognition. Psychological Research, 78(5), 609–622. doi: 10.1007/s00426-013-0519-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uleman JS, Saribay SA, & Gonzalez CM (2008). Spontaneous inferences, implicit impressions, and implicit theories. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 329–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vondervoort JW, & Hamlin JK (2017). Preschoolers’ social and moral judgments of third-party helpers and hinderers align with infants’ social evaluations. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 164, 136–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum MEW, Grossmann I, Kitayama S, & Nisbett RE (2010). The origin of cultural differences in cognition the social orientation hypothesis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, & Leichtman MD (2000). Same beginnings, different stories: A comparison of American and Chinese children’s narratives. Child Development, 71(5), 1329–1346. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman HM, Larkey C, & Somerville SC (1979). The early development of moral criteria. Child Development, 50(3), 869–873. doi: 10.2307/1128956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woo BM, Steckler CM, Le DT, & Hamlin JK (2017). Social evaluation of intentional, truly accidental, and negligently accidental helpers and harmers by 10-month-old infants. Cognition, 168, 154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Cushman F, Hauser M, & Saxe R (2007). The neural basis of the interaction between theory of mind and moral judgment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(20), 8235–8240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701408104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuill N., & Perner J. (1988). Intentionality and knowledge in children’s judgments of actor’s responsibility and recipients’ emotional reaction. Developmental Psychology, 24(3), 358–365. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.24.3.358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuill N, & Pearson A (1998). The development of bases for trait attribution: Children’s understanding of traits as causal mechanisms based on desire. Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 574–586. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.3.574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Helwig CC, & Lau A (1996). Intention, act, and outcome in behavioral prediction and moral judgment. Child Development, 67(5), 2478–2492. doi: 10.2307/1131635 [DOI] [Google Scholar]