Abstract

In this issue, Matthews et al. provide a comprehensive review of published cohorts with heterozygous pathogenic variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4, documenting the wide spectrum of the disease. Due to the extreme phenotypes that patients with heterozygous pathogenic variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4 may show, the disease has been referred to in a variety of ways, including ‘autosomal dominant Alport syndrome’, ‘thin basement membrane disease’, ‘thin basement membrane nephropathy’, ‘familial benign hematuria’ and ‘carriers of autosomal dominant Alport syndrome’. This confusion over terminology has prevented nephrologists from being sufficiently aware of the relevance of the entity. Nowadays, however, next-generation sequencing facilitates the diagnosis and it is becoming a relatively frequent finding in haematuric–proteinuric nephropathies of unknown origin, even in non-familial cases. There is a need to raise awareness among nephrologists about the disease in order to improve diagnosis and provide better management for these patients.

Keywords: Alport, autosomal dominant Alport syndrome, COL4A3, COL4A4, familial haematuria, thin basement membrane disease

It is well known that genomics can allow the reclassification of genetic diseases, and inherited kidney diseases are no exception. Many renal diseases have been named after the physicians who first identified them, as in the case of Fabry disease, von Hippel–Lindau syndrome, Bartter syndrome and Liddle syndrome, among others. For some other diseases, a new name more descriptive of the entity has generally replaced the original name; examples include ‘tuberous sclerosis complex’ instead of ‘Pringle-Bourneville disease’ and ‘immunoglobulin A nephropathy’ instead of ‘Berger’s disease’. For nephropathies caused by newly identified genes, the disease term frequently originates from the gene itself plus a brief description of the entity, such as autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial disease (ADTKD) followed by the name of the causative gene, e.g. ADTKD-UMOD (uromodulin) or ADTKD-MUC1 (mucin 1).

Giving descriptive names to new diseases is usually much easier than changing old names in the light of new findings. In the case of patients with heterozygous pathogenic variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4, use of the traditional term Alport syndrome is contentious, but a new term has yet to emerge. While Alport syndrome as traditionally described fits very well into X-linked (XLAS) and autosomal recessive (ARAS) forms, this does not hold true for patients with heterozygous variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4. In this issue of CKJ, Matthews et al. provide a systematic review of published cases with heterozygous pathogenic variants in COL4A3 or COL4A4. The terms ‘autosomal dominant Alport syndrome’ (ADAS), ‘thin basement membrane disease, ‘thin basement membrane nephropathy,’ ‘familial benign hematuria’ and ‘carriers of ARAS’ have all been used to designate this entity. This confusing terminology has prevented many diagnoses and stopped many patients from receiving early renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibition, among other measures. Also, the variation in names leads to bias in published series, as patients are selected on the basis of the presence of the clinical features associated with the name of the disease specified in the individual article in question.

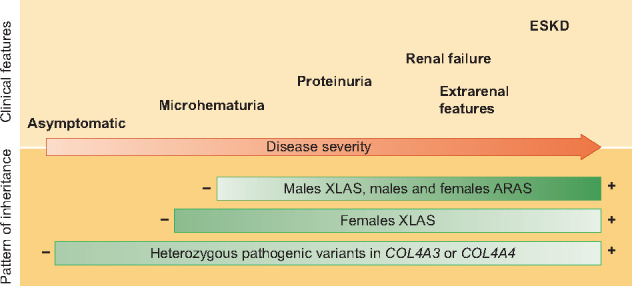

As shown in the review article by Matthews et al., carriers of heterozygous pathogenic variants of COL4A3 or COL4A4 present with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from haematuria (or even bland urine sediment) to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) (Figure 1). Although two recent consensus documents have continued to use the term ‘thin basement membrane disease’ [1, 2], this designation no longer seems suitable, primarily because it is a pathological term and this finding can be found in the early stages of XLAS and ARAS, as well as in other glomerular diseases. For the same reason, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is not used for patients with heterozygous pathogenic variants of COL4A3 or COL4A4 and advanced kidney disease [3–5]. The name ‘familial benign hematuria’ is old fashioned, as we now know that some of these patients may develop ESKD, indicating that this is far from being a ‘benign’ disorder. Moreover, it makes little sense that different affected members of a single family can be considered to have ‘different diseases’ when all share the same single mutation, or that a single patient may be given different names for his/her disease over the course of his/her lifetime.

FIGURE 1.

Clinical spectrum of Alport syndrome according to the pattern of inheritance. Figure modified with permission from Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019 Aug 1;34(8):1272–1279. PMID: 31190059.

With all these terminological issues, Alport syndrome is at least the second most common inherited kidney disease after autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) [6]. It may be even more prevalent than ADPKD if one takes into account the fact that many of these individuals show only microhaematuria. Of course, in terms of health impact, the most relevant subgroup comprises individuals with heterozygous pathogenic variants of COL4A3 or COL4A4 who develop ESKD.

Today there is a need for the nephrologist to be aware of the existence of these diseases for many reasons: this will reduce the number of patients with ‘nephropathy of unknown etiology’ who reach ESKD; it will allow genetic counselling and evaluation of at-risk relatives; patients will be able to participate in Alport syndrome clinical trials; early diagnosis will allow patients to receive early antiproteinuric treatment, specific treatment when available, and adequate follow-up; increased knowledge of the disease will facilitate the development of prognostic tools and therefore differentiation between those patients who will progress to ESKD and those who will not; and it will enable patients to get in touch with patient advocacy and support groups.

The use of next-generation sequencing for routine analyses of suspected cases of familial nephropathy is of seminal relevance to the identification of ADAS patients who would otherwise elude any diagnosis of kidney disease. But not only family cases should be studied; expression of the disease is highly variable in patients with heterozygous pathogenic variants of COL4A3 or COL4A4, meaning that very extreme phenotypes may coexist within a single family. This may prevent recognition of the fact that a genetic disease runs in the family. Also, families may be unaware that relatives have haematuria or chronic kidney disease, and even if they are aware of it, the condition may have been attributed to age, hypertension, diabetes, etc. Therefore ADAS should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with persistent glomerular haematuria, even without a family history.

When nephrologists think of Alport syndrome, most will anticipate some extrarenal manifestations, such as sensorineural deafness and ocular anomalies, but, as shown by Matthews et al., these findings are very uncommon in patients with heterozygous pathogenic variants of COL4A3 or COL4A4.

The review by Matthews et al., and hopefully the future publication of findings in more cohorts, will raise awareness of this ‘not so rare’ disease and allow precise diagnosis and follow-up for a significant number of kidney patients who have been undiagnosed or misdiagnosed to date.

FUNDING

The author’s research is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III/Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) funds, RETIC REDINREN RD16/0009 FIS FEDER FUNDS (PI15/01824, PI16/01998, PI18/00362, PI19/01633).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kashtan CE, Ding J, Garosi G et al. Alport syndrome: a unified classification of genetic disorders of collagen IV α345: a position paper of the Alport Syndrome Classification Working Group. Kidney Int 2018; 93: 1045–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Savige J, Ariani F, Mari F et al. Expert consensus guidelines for the genetic diagnosis of Alport syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2019; 34: 1175–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 2014; 86: 1253–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gast C, Pengelly RJ, Lyon M et al. Collagen (COL4A) mutations are the most frequent mutations underlying adult focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 961–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang M, Chun J, Genovese G et al. Contributions of rare gene variants to familial and sporadic FSGS. J Am Sci Nephrol 2019; 30: 1625–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groopman EE, Marasa M, Cameron-Christie S et al. Diagnostic utility of exome sequencing for kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 142–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]