Abstract

Systemic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitions can induce worsening hypertension, proteinuria and glomerular diseases of various types. These agents can also be used to treat ophthalmic diseases like proliferative diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema, central retinal vein occlusion and age-related macular degeneration. Recently, pharmacokinetic studies confirmed that these agents are absorbed at levels that result in biologically significant suppression of intravascular VEGF levels. There have now been 23 other cases published that describe renal sequela of intravitreal VEGF blockade, and they unsurprisingly mirror known systemic toxicities of VEGF inhibitors. We present three cases where stable levels of proteinuria and chronic kidney disease worsened after initiation of these agents. Two of our three patients were biopsied. The first patient’s biopsy showed diabetic nephropathy and focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) with collapsing features and acute interstitial nephritis (AIN). The second patient’s biopsy showed AIN in a background of diabetic glomerulosclerosis. This is the second patient seen by our group, whose biopsy revealed segmental glomerulosclerosis with collapsing features in the setting of intravitreal VEGF blockade. Though FSGS with collapsing features and AIN are not the typical lesions seen with systemic VEGF blockade, they have been reported as rare case reports previously. In addition to reviewing known elements of intravitreal VEGF toxicity, the cases presented encompass renal pathology data supporting that intravitreal VEGF blockade can result in deleterious systemic and renal pathological disorders.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, aflibercept, bevacizumab, diabetic retinopathy, focal and segmental sclerosis, nephrotic syndrome, proteinuria, ranibizumab, vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF depletion

INTRODUCTION

There will be an estimated 54 million diabetics in the USA by 2030 [1], and while the prevalence estimates from 2004 are dated, they showed that 4 million adults had diabetic retinopathy (DR) [2]. The development of macrovascular and microvascular complications increases greatly with the duration of time a patient has had diabetes, especially if poorly controlled [3]. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is diagnosed in 80% of patients with diagnosed DR [4, 5]. There are nearly 125 000 patients receiving vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections in the USA as of 2015, and a large subset of these patients are vulnerable, and at risk for worsening renal function, proteinuria and end-stage renal disease [6, 7]. DR is due to neo-vascularization caused by VEGF-induced dysregulation of vascular proliferation [8]. It can be remedied by laser photocoagulation and intravitreal VEGF blockade [9].

VEGF SIGNALING

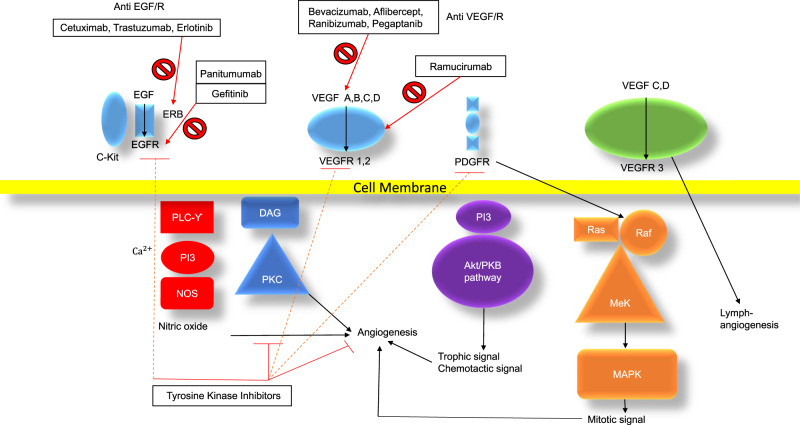

VEGF inhibitors inhibit a very complex cellular signaling system involved in cell growth, endothelial function and podocyte function [10–12]. The VEGF signaling pathway is linked with the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway at the cellular signaling level. Its downstream mediators are the targets of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [13] and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling system [14]. Figure 1 demonstrates VEGF signaling and related EGFR signaling, as well as downstream signaling from TKI and mTOR pathways.

FIGURE 1.

EGFR, VEGF, TKI and mTOR signaling pathways: Akt, protein kinase B (PKB); C-Kit, mast/stem cell growth factor receptor; DAG, diacyl glycerol; ERB, EGFR related-receptor protein (Her2Neu is on type of this); MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; Mek, dual threonine and tyrosine recognition kinase; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; PKC, protein kinase C; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PI3, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; PLCϒ, phospholipase C-gamma; RAF, serine/threonine kinase/cellular homolog of viral RAF gene; RAS, rat sarcoma protein; VEGF A–D, vascular endothelial growth factor A–D; VEGFR 1–3, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1–3. Adapted from Selamet et al. [10].

VEGF ANTAGONIST USES IN ONCOLOGIC INDICATIONS

The oncologic uses of VEGF blockade are many, and they are well established as adjunct chemotherapy agents [10–12]. It is equally recognized that they can sometimes have severe systemic side effects [10, 11]. Bevacizumab was the first VEGF blocking agent used systemically in cancer patients. It is a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody that is currently indicated for non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, gliomas (a form of brain tumor) and other malignancies [15–21]. Bevacizumab was Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for systemic use in 2004 [22].

The evidence is firm that systemic VEGF blockade in oncologic treatment results in worsening hypertension, de novo or worsening proteinuria and thrombotic microangiopathy. VEGF blockade can also result in worsening kidney function and irreversible glomerular injury [10–12].

THE PHYSIOLOGIC ROLE OF VEGF IN THE KIDNEYS AND ENDOTHELIUM

VEGF is an increasingly recognized signal mediator that has been shown to be important in the health of renal podocytes and endothelial cells [11, 12, 23]. Both an excess and deficiency in VEGF signaling have been shown to negatively affect podocyte structure and function. In the podocyte, VEGF signaling is involved in organizing the actin cytoskeleton, including interactions with non-structural Protein 1 and Nephrin [11, 12, 23]. Proper signaling also results in a trophic survival signal through Akt [protein kinase B (PKB)], proper cell cycle function through Ras (Rat-Sarcoma-Protein)/Raf (Serine/threonine-protein kinase) interactions. Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells-mediated targets of inflammation and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone activation are also suppressed with proper VEGF stimulation [11, 12, 23].

In the endothelium, VEGF signaling is involved in nitric oxide production and vasodilation, a trophic signal for endothelial survival and proper function. Di-Acyl Glycerol-Kinase-Epsilon is also controlled through VEGF signaling, and disruption of this signaling can lead to thrombotic microangiopathy [11, 12, 23]. Hence, significant inhibition of this pathway can easily be shown to lead to podocyte effacement, inflammation and nephrotic syndrome by disruption of the cytoskeleton of the podocyte [11, 12, 23]. There is also a clear link to the thrombotic disorders and hypertension, which would be caused by dysfunction of endothelial cells, clotting dysregulation and nitric oxide synthesis disruption [11, 12, 23].

OPHTHALMIC USE OF VEGF ANTAGONISTS

The use of VEGF antagonists in ophthalmic diseases was initially administered ‘off-label’, but the US FDA has granted ‘on-label’ indications for aflibercept (Eylea®) and ranibizumab (Lucentis®) [23]. These agents are indicated for proliferative diabetic retinopathy /diabetic macular edema (DME), central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [23].

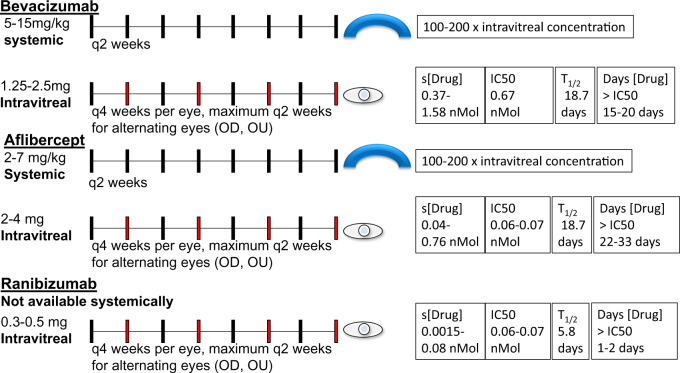

A typical ophthalmologic regimen would usually be given every month in each eye. The most intensive therapeutic regimens would involve patients getting injections in alternating eyes every 2 weeks with a duration of 1 month between injections in the same eye. The dose of bevacizumab for each injection is 1.25–2.5 mg intravitreally/dose. The typical dose of aflibercept is 2–4 mg given intravitreally/dose. The dose of ranibizumab is 0.3–0.5 mg given intravitreally/dose.

For comparison, the usual systemic dose of bevacizumab is 5–15 mg/kg every 2 weeks. The usual systemic dosage of aflibercept is 2–7 mg/kg every 2 weeks, while ranibizumab is not used systemically. The drug levels with systemic administration are estimated at 100- to 200-fold higher than those achieved with intravitreal injection as cited in FDA package inserts [11, 15–17, 22–26].

SYSTEMIC ABSORPTION OF INTRAVITREAL VEGF ANTAGONISTS

Pharmacokinetic studies have confirmed that the ophthalmic administration of these agents results in absorption and serum drug levels that are near or greater than the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) [26]. The detected serum levels are high enough to result in suppression of more than 50% of intravascular VEGF levels as described by Avery et al. [16–18, 27].

The serum level of bevacizumab achieved with intravitreal injection was noted to range from 0.37 nanomoles (nMol) at a minimum and up to 0.77–1.58 nMol at a maximum level. This is greater than the 0.668 nMol IC50. The serum half-life of 18.7 days after three intravitreal injections means that the agent may stay above the IC50 at most for 15–20 days after injection [11, 15–17, 23, 26].

The serum level achieved with intravitreal aflibercept ranges between 0.04 and 0.76 nMol at a maximum level, which is an order of magnitude higher than the IC50 of 0.06–0.07 nMol. The serum half-life is estimated at 11.4 days after 3-month interval injections, and therefore this agent can stay above the IC50 at most for 22–33 days after injection [16, 17, 23, 26].

The serum level achieved with intravitreal ranibizumab ranges between 0.0015 nMol and 0.08 nMol; the maximum of this range is near the IC50 of 0.06–0.07 nMol. A serum half-life of 5.8 days was noted, without any evidence of accumulation of drugs between subsequent injections [16, 17, 23, 26]. This agent is only transiently (1–2 days) at higher concentrations than the IC50. Ranibizumab has a shorter half-life in the vitreous humor and is more rapidly cleared because it is a light chain molecule, explaining its lower systemic absorption. Rapid removal of drugs from serum explains the lower half-life, lower systemic concentration, and explains why it has a decreased risk of intravascular VEGF inhibition and resultant systemic effects [16, 17, 23, 26]. See Figure 2 for a depiction of systemic versus intravitreal dosages, serum drug levels as compared with published IC50, half-life and time the drug persists above the IC50.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of pharmacokinetic studies showing serum drug levels, serum half-lives from systemically and intravitreally injected VEGF inhibitors. [Drug], concentration of drug every 2 weeks; mg, milligrams; mg/kg, milligram/kilogram; OD, right eye; OU, left eye; q(x) weeks, every (x) weeks; s[Drug], serum concentration of drug; T1/2, half-life (in days).

Several studies corroborate that VEGF suppression is detected by measuring serum VEGF levels [19–21, 28], but the clinical significance is only now being investigated [23]. Accordingly, it is expected that these agents are absorbed at levels capable of causing systemic effects due to the finding of suppressed intravascular VEGF [29]. Bevacizumab and aflibercept are higher potencies, with a longer half-life, stronger absorption have more pronounced VEGF depletion [15–18, 28]. Ranibizumab, on the other hand, tends to have lower absorption and less pronounced VEGF depletion [15–18, 28]. Table 1 depicts the structural and functional differences between VEGF antagonists in common ophthalmologic use.

Table 1.

VEGF monoclonal antibodies

| Agent | Brand name | Weight (kDa) | IC50 (nmol/L) | Binding specificity | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab | Avastin© | 149 | 0.66 | VEGF-A | IgG1, murine variable region, mAb |

| Aflibercept | Zaltrap©, Eylea© | 115 (15% glyc) | 0.06–0.07 | VEGF-A, B | IgG Fc dimerized, dimeric VEGFR 1,2 binding sites |

| Ranibizumab | Lucentis© | 48 | 0.06–0.07 | VEGF-A | Kappa light chain mAb fragment |

Fc, constant region; g/mol, grams/mole; glyc, glycosylated; IgG, immunoglobulin G; mAb, monoclonal antibody; kDa, kilodalton; mol, mole; mmol/L, millimoles per liter; VEGF-A, B, vascular endothelial growth factor (A, B); VEGFR, Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

SYSTEMIC EFFECTS OF INTRAVITREAL VEGF BLOCKADE

Animal studies have shown that anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody binding can be detected in glomeruli after intravitreal injection. This alters levels of glomerular VEGF and can alter the number of endothelial capillary fenestrations in simian studies [30]. There have been mixed results regarding effects on hypertension [31–34], with one new study linking hypertension and the need for intravitreal VEGF inhibitor use, though the converse relationship cannot be ruled out [35]. Studies have not linked VEGF inhibition to acute kidney injury, but follow-up has been limited [36]. The systemic absorption has known uses in ophthalmology, with the fellow eye effect. This is an observed effect where treating one eye with VEGF blockade improves DR in the contralateral eye [23].

Intravitreal VEGF inhibition raising blood pressure was shown in two studies; one offered an analysis showing 14.3% of patients suffered from a worsening of systolic blood pressure with VEGF blockade [33]. Though no statistically significant change in proteinuria was found in several studies, one recently published study found that 45% of patients with diabetic nephropathy showed increased albuminuria after VEGF blockade was initiated [31]. Another study showed 12.2% of patients with worsening urine albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) category after intravitreal VEGF blocking antibody injections, but this was not significant [37]. A significant limitation of looking for worsening of categories of proteinuria (as in Glassman et al. [37]) is that patients who already have macroalbuminuria (A3 category) would not be captured in the analysis if they experience an exacerbation.

A recent retrospective review of 90 patients, including 45 with diabetic kidney disease, showed worsening proteinuria and renal function in patients with DR and DN over 31 months but was unable to link this progression to greater number of anti-VEGF injections given. Twelve percent of these patients had A3 proteinuria (>300 mg albumin/g protein), as this is the most vulnerable class of patients with DN and DR [38]. This study had significant limitations per the authors because it represented a small, uncontrolled and retrospective study where treatment regimens involved injections in one eye, and systemic absorption was not verified and differences therein were not controlled for [38]. This may indicate that proteinuria and glomerular disease are effects seen within a particular subgroup of patients rather than a side effect seen in all patients receiving these agents [31, 37, 38].

POPULATION STUDIES AND INTRAVITREAL VEGF BLOCKADE

Some population studies have also raised concerns about all-cause and vascular mortality after initiation of these therapies in patients with AMD [18, 39–41], although these findings were not uniformly observed [42, 43]. The Hanhart studies are worrisome because they consistently showed an increased risk of all-cause mortality, post-cardiovascular (CV) event mortality and post-cerebrovascular (CVA) event mortality. The Hanhart studies were controlled against age- and gender-matched controls. In patients with CVA or CV events, the controls also had a CV/CVA event [39–41]. These events can be plausibly linked with proteinuria, a variable that is not optimally tracked. Table 2 reviews all current studies with data on VEGF absorption, hypertension, renal function and proteinuria.

Table 2.

Summary of literature on clinical systemic effects of intravitreal anti-VEGF injection

| Systemic effect/pathology | n | Study type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Evidence of drug absorption and systemic VEGF inhibition | |||

| Absorption in AMD, dec. systemic VEGF (Bev, Aflb) >Ran | 56 | Prospective observational study | Avery et al. [16] |

| Absorption in AMD/DME/CRVO, dec. systemic VEGF (Bev, Aflib) >Ran | 151 | Prospective observational study | Avery et al. [17] |

| Absorption of drug in AMD, dec systemic VEGF | 610 | Retrospective study of RCT data | Rogers et al. [20] |

| Dec. systemic VEGF (Bev, Aflib) | 38 | Prospective randomized observational study | Zehetner et al. [21] |

| Dec. systemic VEGF (Bev, Aflib) | 72 | Prospective non randomized clinical study | Hirano et al. [28] |

| Dec. systemic VEGF (Bev, Aflib) >Ran | 436 | Prospective randomized clinical study | Jampol et al. [29] |

| B. Animal studies showing anti-VEGF binding to glomeruli | |||

| Absorption of drug, binding at glomerulus | N/A | Animal (Simian) study | Tschulakow et al. [30] |

| C. Effects on hypertension after intravitreal injection | |||

| Limited short-term rise in blood pressure at 1 h | 135 | Prospective observational study | Lee et al. [32] |

| Long- and short-term rise in systolic blood pressure | 82 | Observational study | Rasier et al. [33] |

| No significant change in blood pressure | 57 | Observational study | Risimic et al. [34] |

| Higher blood pressure linked to need for more VEGFi | 2916 | Retrospective study | Shah et al. [35] |

| D. Trial data | |||

| Increased proteinuria 45% of patients (not statistically significant) | 40 | Prospective observational Study | Bagheri et al. [31] |

| Significant rise in diastolic blood pressure | |||

| Significant rise in hemoglobin and platelets | |||

| No change in eGFR 7–30 days after injection (Bev, Aflib, Ran) | 69 | Retrospective observational study | Kameda et al. [36] |

| No long-term change in HTN or category of albuminuria | 660 | Planned retrospective analysis of trial | Glassman et al. [37] |

| No association with # VEGFi injections and proteinuria | 43 | Retrospective observational study | O’Neill et al. [38] |

| Significant rise in UPCR in patients with preexisting proteinuria | 53 | Prospective observational study | Chung et.al. [64] |

| E. Population studies showing increased morbidity and mortality | |||

| Increased risk of CVA in DME patients | N/A | Meta-analysis | Avery et al. [18] |

| Increased AC mortality in AMD patients | 1063 | Retrospective observational studya | Hanhart et al. [39] |

| Increased risk of mortality after MI in AMD patients | 211 (with MI) | Retrospective observational studyb | Hanhart et al. [40] |

| Increased risk of mortality after CVA in AMD patients | 948 (with CVA) | Retrospective observational studyb | Hanhart et al. [41] |

| No finding of CVA, MI, AC mortality in AMD patients | 504 | Retrospective observational studyb | Dalvin et al. [42] |

| No finding of increased CVA in DME patients | 2541, 690 (with VEGFi) | Retrospective observational studyb | Starr et al. [43] |

, number of (injections); AC, all-cause mortality; Aflib, aflibercept; Bev, bevacizumab; dec., decreased; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; n, number of study subjects; Ran, ranibizumab; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VEGFi, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors. Green lettering = positive result linking VEGFi and renal outcome; orange lettering = equivocal result; red lettering = negative result.

Age- and gender-matched control served as comparator group.

Age- and gender-matched control with a CV or CVA event served as comparator group.

CLINICAL CASES SHOWING WORSENING RENAL PARAMETERS

At this point, there are multiple published cases reports and series of intravitreal VEGF administration associated with worsening proteinuria, hypertension and glomerular disease [11, 31, 44–54]. We present three additional cases where stable levels of proteinuria and chronic kidney disease (CKD) worsened after initiation of intravitreal VEGF antagonists.

Clinical cases

Case 1

A 58-year-old man with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (DM) Type 2 diagnosed in 2010, CKD due to diabetic nephropathy, bilateral proliferative DR, bilateral macular edema, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and history of tobacco use was referred by his nephrologist for continued management of CKD Stage 5 and initiation of peritoneal dialysis (PD). He complained of poor appetite without nausea or vomiting. He generally felt fatigued without dyspnea or extremity swelling. No kidney biopsy was performed previously.

The patient was diagnosed with DM upon initial evaluation with his primary care physician in 2010. The initial hemoglobin A1c was 10.8%. His diabetes was well controlled since at least 2013 with a hemoglobin A1c no greater than 6.8%. Oral medications included atorvastatin, calcium acetate, citric acid-sodium citrate solution, diltiazem ER, ergocalciferol, furosemide, hydralazine, sitagliptin, patiromer, pentoxifylline and sevelamer. He had no history of Non Steroidal Anti Inflammatory Drug (NSAID) use, iodinated contrast exposure or ingestion of Chinese herbal medications. There was no history of bisphosphonate administration.

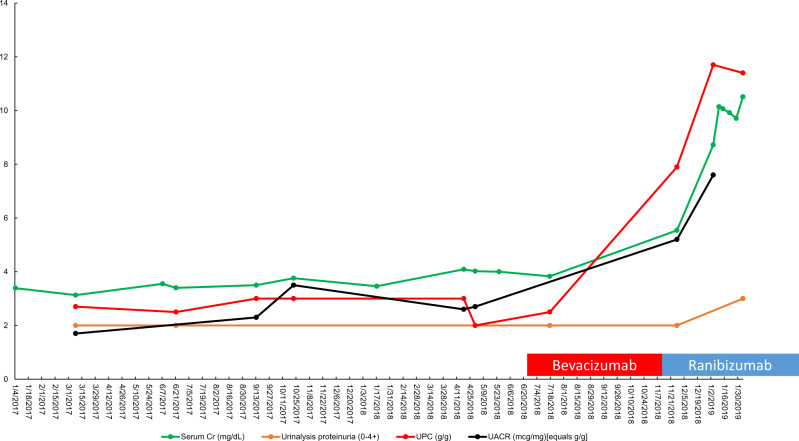

His baseline serum creatinine (Cr) was 3.4–3.8 mg/dL from 2015 to August 2018, and his estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 15–20 mL/min. His serum Cr then rose to 5.5 mg/dL in November 2018 and then rose again to serum Cr of 10 mg/dL in February 2019. The eGFR declined correspondingly from 15 to 10 mL/min, and then to 5 mL/min ultimately by November 2018. UACR also increased from a baseline of 1.7–2.7 g albumin/g Cr in April 2018 to 5.2–7.6 g albumin/g Cr in December 2018 to January 2019. The patient’s baseline urine protein/Cr ratio was stable at 2–3.5 mg/dL fromAugust 2015 to July 2018. The urine protein/Cr ratio increased from 2.5 g protein/g Cr in July 2018 to 11.7 g protein/g Cr in January 2019. A renal ultrasound had revealed no structural renal disease. A VEGF-A level was not be obtained on this patient, while he was on intravitreal VEGF blockade therapy, and he is currently off medication. Serum albumin dropped from 4 to 2.6 g/L over the course of the 2018–19 after the initiation of intravitreal anti-VEGF agents.

Upon review of records, the patient began following with ophthalmology in May 2018. Due to left vitreous hemorrhage, the patient underwent pars plana vitrectomy, fluid-air exchange and pan-retinal photocoagulation of the left eye in May 2018. He was then initiated on pan-retinal photocoagulation and intravitreal bevacizumab (1.25 mg): 20 June 2018 (L-left eye) and 28 June 2018 (R-right eye). Due to worsening diabetic macular edema, the patient was switched to intravitreal ranibizumab (0.3 mg): 7 December 2018 (R), 2 January 2019 (L), 18 January 2019 (R), 1 February 2019 (L), 1 March 2019 (R), 8 March 2019 (L) and 5 April 2019 (L). These injections together give a total dose of 2.5 mg of bevacizumab and 2.1 mg of ranibizumab. Figure 3 depicts the trends of serum and urine markers of renal function with respect to the timing of initiation of intravitreal VEGF blockade.

FIGURE 3.

Trend of serum Cr, urinalysis proteinuria, urine protein/Cr ratio and urine albumin/Cr ratio for Patient 1 versus date. Red box, bevacizumab administration; blue box, ranibizumab administration. UPC, urine protein/Cr ratio.

His blood pressure remained controlled throughout this time. Despite good control in diabetes and hypertension, the patient had an abrupt worsening in proteinuria and renal function soon after the initiation of intravitreal anti-VEGF agents. The patient declined a renal biopsy, and his serum Cr continued to deteriorate up to 10.5 mg/dL in December 2018. During December 2018 to January 2019, he was transitioned to PD, and he remains on renal replacement therapy (RRT) therapy as of March 2020.

Case 2

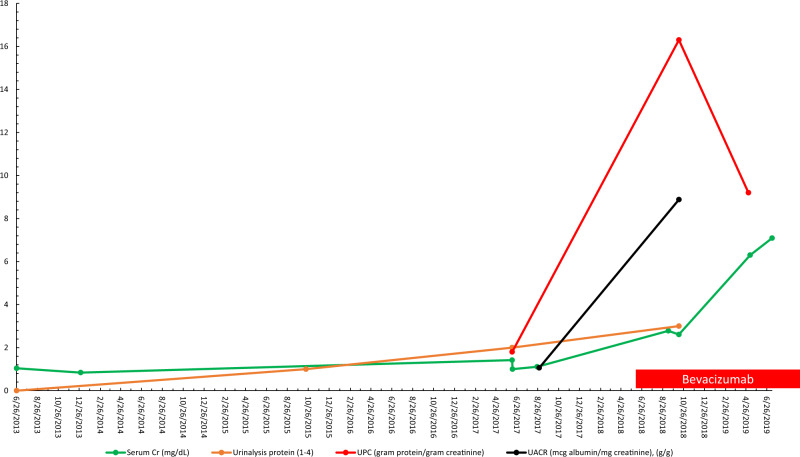

A 59-year-old male presented to care with a history of poorly controlled DM Type 2 and obesity that was known for 15 years (diagnosed 2003), as well as concomitant hypertension. He had no prior use of NSAIDs, herbal medicines or intravenous iodinated contrast. The patient was taking calcifediol, folic acid, furosemide, lisinopril, amlodipine, sitagliptin, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12. Serum Cr had been stable at 1.1 mg/dL in August 2017, which increased to 2.78 mg/dL by September 2018 following intravitreal VEGF blockade. eGFR was 73 mL/min initially in August 2017 and decreased to 36 mL/min by September–October 2018. In August 2017, the patient had 1.1 g of albuminuria with an increase of in albumin/Cr ratio of 9.4 g albumin/g- Cr in October 2018 over the course of a year. The patient had 1.8 g protein/g Cr in June 2017, which increased profoundly to 16.3 g protein/g Cr by October 2018. Serum albumin also dropped from 4 g/L in August 2017 to 2.7 g/L in May 2019 after intravitreal VEGF blockade was initiated. The patient remained hypertensive throughout, with average blood pressures of 150–170/80–90 mmHg throughout time period of 2018–19 with no change relative to his elevated baseline blood pressure.

Hemoglobin A1c had decreased at the time of presentation with intensive control to 6.6% from a high of 14.3%. Extensive serological testing was mainly negative [human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis panel and anti-nuclear antibody (ANA)]. Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) did show a faint restricted monoclonal band but with no corresponding monoclonal band seen on immunofixation. Complement levels were normal as well for C3 (144 mg/dL) and C4 (48 mg/dL). Urinalysis showed only trace blood and 3+ proteinuria. Renal ultrasound revealed no hydronephrosis and echogenic kidneys compatible with chronic renal disease. Treatment history was as follows: 1.25 mg of bevacizumab on 16 July 2018 (R); 1.25 mg on 18 July 2018 (L); 1.25 mg on 8 August 2018 (R); 1.25 mg ×2 on 15 September 2018 (R, L); 1.25 mg ×2 on 10 October 2018 (R, L); 1.25 mg on 7 December 2018 (L); 1.25 mg on 15 January 2019 (R); 1.25 mg on 3 March 2019 (L); 1.25 mg on 3 April 2019 (R) and 1.25 mg on 22 May 2019 (R). These injections give a total dose of bevacizumab of 16.25 mg.

Given ongoing deterioration of renal function, a renal biopsy was obtained and showed 15 glomeruli on light microscopy, all without global sclerosis. The glomeruli had diffuse and nodular mesangial matrix expansion with segmental glomerulosclerosis in four glomeruli. One of these lesions of segmental sclerosis demonstrated collapsing features characterized by luminal obliteration with insudates, segmental tuft deflation and associated podocyte hyperplasia with prominent cytoplasmic vacuolization. No crescents or necrotizing features were seen. There was diffuse interstitial edema with a mild to moderate mixed interstitial inflammatory infiltrate, which included both neutrophils and eosinophils. Tubulointerstitial scarring was moderate and arterioles demonstrated afferent and efferent hyalinization. No intravascular fibrin thrombi were seen, nor were there vasculitic changes. Immunofluorescence evaluation demonstrated no significant glomerular staining for immune deposits. Electron microscopy displayed global glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickening as well as diffuse and nodular mesangial matrix expansion consistent with diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Podocytes display partial foot process effacement. No GBM double contours were noted and endothelial cell fenestrations were intact. The final diagnoses were diffuse and nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis and segmental glomerulosclerosis with focal collapsing features and interstitial nephritis.

The patient’s renal function continued to deteriorate rapidly with the serum Cr increasing to 6.3 mg/dL by May 2019, with eGFR of 11 mL/min, requiring initiation of three times weekly hemodialysis (HD). Figure 4 depicts the trend in serum Cr, urine protein/Cr ratio, UACR and urinalysis proteinuria. Figure 5 shows the renal biopsy findings. A plasma VEGF-A level was not obtained while the patient was on intravitreal VEGF blockade. The patient was transitioned to RRT (HD) as of March 2020.

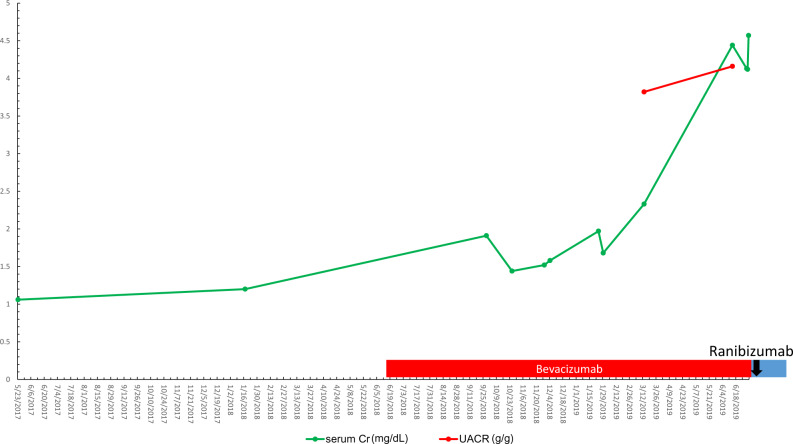

FIGURE 4.

Trend of serum Cr, urinalysis proteinuria, urine protein/Cr ratio and urine albumin/Cr ratio for Patient 2 versus date. UPC, urine protein/Cr ratio.

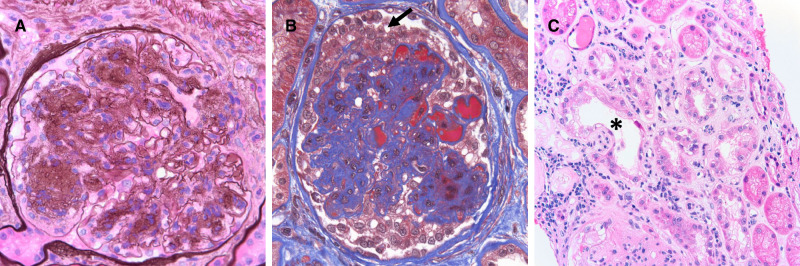

FIGURE 5.

Renal biopsy micrographs for Patient 2 showing diabetic nephropathy and focal and segmental sclerosis with collapsing features. Renal biopsy reveals underlying diffuse and nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis (A, Jones methenamine silver 600×). There were lesions of segmental sclerosis with focal collapsing features (B, Trichrome stain 600×) characterized by capillary luminal obliteration by insudates and segmental tuft deflation, with overlying podocyte hyperplasia and prominent cytoplasmic vacuolization (black arrow). There was also concomitant acute tubular necrosis (C, asterisk, hematoxylin and eosin, 200×), with interstitial edema and a mixed interstitial inflammatory infiltrate (interstitial nephritis).

Case 3

A 46-year-old male presented to care with a history of DM Type 2 known for 14 years (diagnosed 2005), requiring both insulin and metformin, but due to deterioration in renal function he was taken off metformin with an urgent referral for a nephrology evaluation. He had no recent use of NSAIDs but had taken naproxen remotely and was told to not take again. He denied the use of herbal medicines or intravenous iodinated contrast. The patient was taking glargine insulin, lisinopril, acetazolamide eye drops, furosemide, baby aspirin and atorvastatin. There was no use of bisphosphonates documented throughout the patient’s medical history.

Serum Cr had been 1–1.2 mg/dL before intravitreal anti-VEGF initiation in June 2018. The serum Cr increased to 2.33 mg/dL by March 2019 after initiation of intravitreal VEGF blockade. eGFR was 46–48 mL/min prior to intravitreal VEGF blockade was initiated in 6/2018 and had been stable, after starting intravitreal VEGF blockade the eGFR had declined to 32 mL/min by 13 March 2019. Unfortunately, there were no baseline levels for UACR and urine protein/Cr ratio (grams protein/gram Cr) that could be located despite a thorough historical search. Albuminuria was measured after starting intravitreal bevacizumab and was found to be at 3.8 g of albumin/g Cr in March 2019 that rose to 4.2 g albumin/g Cr by June 2019. The urine protein/Cr ratio was first checked after VEGF blockade was started and was markedly elevated at 6.35 g protein/g Cr; however, no prior baseline could be found. The serum albumin had dropped from 3.9 to 3.2 g/L over the course of 12 months of intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy from June 2018 to June 2019 . Blood pressure when first seen (after intravitreal VEGF inhibition) was 170s–190s/100s mmHg, higher than the patient’s baseline of 150–170 mmHg prior to June 2018. The patient’s blood pressure was eventually controlled with addition and titration of nifedipine to 140–150 mmHg systolic blood pressure, but with continuing proteinuria and renal dysfunction.

Hemoglobin A1c was controlled at 6.2–6.4%, and extensive serological testing was once again negative (HIV, hepatitis panel, ANA and SPEP). Complement levels were within normal limits. A renal ultrasound showed no hydronephrosis, no masses and increased echogenicity consistent with CKD. Magnetic resonance venography ordered without gadolinium contrast showed no renal vein thrombosis. Urinalysis showed only trace blood and 3+ proteinuria. Treatment history with bevacizumab was as follows: 1.25 mg on 14 June 2018 (R); 1.25 mg on 30 July 2018 (L); 1.25 mg on 24 February 2019 (R) and 1.25 mg ×2 on 26 February 2019 (R, L). He was then switched to ranibizumab 0.3 mg on 25 June 2019 (R, L). These injections give a total dose of bevacizumab of 7.5 mg and a total dose of ranibizumab of 0.6 mg.

Given the ongoing deterioration of renal function, a renal biopsy was obtained. The light microscopy section showed 33 glomeruli, 12 of which were globally sclerotic (approximately 33% global glomerulosclerosis). Mesangial areas displayed diffuse and nodular expansion by matrix material. No segmental sclerosis or crescents were seen. A patchy and focally dense mixed interstitial inflammatory infiltrate containing few eosinophils was also present. There was severe tubulointerstitial scarring. Immunofluorescence was performed and there was no significant glomerular staining for immune reactants. Electron microscopy revealed global GBM thickening as well as diffuse and nodular mesangial matrix expansion. The final diagnoses were diffuse and nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis and likely drug/medication-induced interstitial nephritis. The patient’s renal function continued to deteriorate rapidly with a recent serum Cr of 4.57 mg/dL (eGFR of 15 mL/min) by July 2019 and an eventual initiation of HD. Figure 6 depicts the trends in serum Cr, urine protein/Cr ratio, UACR and urinalysis proteinuria. Figure 7 shows the renal biopsy findings. A plasma VEGF level was obtained by June 2019 and found to be low at 36 pg/mL, approximating at the lowest detectable level on this assay (>31 pg/mL). The patient was transitioned to RRT via HD as of March 2020.

FIGURE 6.

Trend of serum Cr, urinalysis proteinuria, urine protein/Cr ratio and urine albumin/Cr ratio for Patient 3 versus date. Black arrow, ranibizumab initiation; UACR, albumin/Cr ratio.

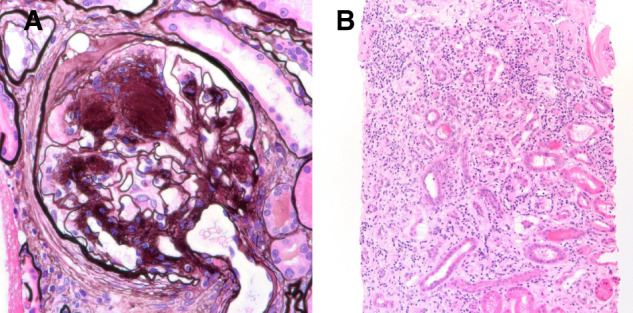

FIGURE 7.

Renal biopsy micrographs for Patient 3 showing diabetic nephropathy and drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Renal biopsy revealed diffuse and nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis (A, Jones methenamine silver 600×). There were diffuse interstitial edema and extensive interstitial inflammation (B) with associated tubular inflammation and acute necrosis, consistent with interstitial nephritis.

NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF THE SYSTEMIC EFFECTS OF INTRAVITREAL VEGF BLOCKADE

Unrecognized renal and vascular events may be occurring in certain patients treated with VEGF blockade [11, 31, 44–54]. This is especially true in diabetic patients who often have comorbid hypertension, proteinuria and CKD [11, 23]. The concurrence of diabetes and diabetic eye disease with hypertension, proteinuria and CKD means that intravitreal VEGF toxicity may be attributed to underlying comorbidities [10, 11, 23].

It is likely that there are certain factors that may exacerbate the harmful effects of VEGF blockade. Co- or preexisting hypertension, CKD and proteinuria are known to increase the risk of the developing preeclampsia [23]. This process is mediated by soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 resulting in increased VEGF scavenging and signaling depletion [55]. Since preeclampsia is known to be affected by the above renal parameters, it stands to reason that the process of significant VEGF depletion may be inherently dangerous in patients with hypertension, proteinuria and renal disease [23, 55]. It is this subset of patients in whom VEGF depletion may cause worsening hypertension, proteinuria, renal dysfunction and in some instances, glomerulopathies [10–12, 23, 34].

There were previously 23 published case reports of worsening proteinuria, decreased renal function, glomerular diseases and hypertension following initiation of intravitreal VEGF blockade [11, 31, 44–54, 56–59]. There are also three recently described cases of chronic thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) associated with starting intravitreal VEGF blockade with bevacizumab and aflibercept (under review).

With the addition of these three cases, this brings the total potential published cases to 26, including one instance of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) with collapsing features (cFSGS) in a patient receiving VEGF blockade for AMD, similar to the biopsy in Case 2. The finding of two such cases is notable, especially given link between cFSGS and TMA noted in literature [51]. This highlights the importance of renal biopsies in identifying unique pathology, which may be induced by intravitreal VEGF blockade.

While systemic VEGF blockade was initially reported to cause TMA, diverse glomerular lesions have been documented, including minimal change disease (MCD), membranous nephropathy and FSGS [10–14, 23]. Notably with intravitreal VEGF blockade, there have been two cases of collapsing FSGS, four published TMA cases and three new ones under review (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pathology and intravitreal VEGF blockade use

| Reference | n | Age(s) (years) | Gender | Agent used | Clinical pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanna et al. [11] | 4 | 82, 54, 53 and 65 | F | Bev & Ran | Case 1 de novo MCD (biopsy+), Cases 2–4 increased proteinuria, CKD progression, HTN worsening |

| Bagheri et al. [31] | 18/40 | 60.3 ± 9.2 | 33 F and 7 M | Bev | Increased proteinuria in 18/40, 45% of patients |

| Cheungpasitporn et al. [44] | 2 | 52, 67 | 2 M | Bev | Case 1, MGN and Case 2 TMA (biopsy+) |

| Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network [45] | 3 | NR | NR | Bev | Decreased eGFR |

| Georgalas et al. [46] | 2 | 51 and 68 | F and M | Ran & Bev | Decreased eGFR, HD started |

| Jamrozy-Witkowska et al. [47] | 1 | NR | NR | NR | Decreased eGFR |

| Kenworth et al. [48] | 1 | 88 | F | Bev | Increased proteinuria |

| Khneizer et al. [49] | 1 | 74 | M | Bev | MGN (biopsy+) |

| Morales et al. [50] | 1 | 56 | M | Ran | DN (biopsy+) |

| Nobakht et al. [51] | 1 | 96 | F | Bev → Ran → Aflib | cFSGS (biopsy+) + low systemic VEGF level |

| Pellé et al. [52] | 1 | 77 | F | Ran | TMA (biopsy+) |

| Perez-Valdivia et al. [53] | 1 | 54 | M | Bev | Relapsed MCD (biopsy+) |

| Sato et al. [54] | 1 | 16 | F | Bev | Relapsed MCD (biopsy+) |

| Hanna et al. [56] | 1 | 38 | F | Bev → Ran | Worsening HTN and proteinuria, lessened with Ran use versus Bev |

| Touzani et al. [57] | 1 | 72 | M | Bev | Endotheliosis/possible TMA (biopsy+) |

| Tran [58] | 1 | 51 | M | Bev | AIN (biopsy+) |

| Yen et al. [59] | 1 | 56 | M | Bev | TMA (biopsy+) |

| Hanna et al. [manuscript under review] | 3 | 43, 56 and 77 | M, F and F |

|

|

| CCS (Shye et al.) | 3 | 46, 58 and 59 | 3 M |

|

|

Biopsy only if (biopsy+) stated. Aflib, aflibercept; AIN, acute interstitial nephritis; Bev, bevacizumab; biopsy+, biopsy obtained; CCS, current case series; F, female; HTN, hypertension; M, male; MGN, membranous glomerulonephritis; n, number of patients; NR, not recorded; Ran, ranibizumab.

The coexistence of these different glomerular diseases continues to be noted in association with intravitreal VEGF blockade. Although systemic VEGF and tyrosine kinase blockade should involve different arms of the C-Maf-inducing protein and v-rel avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A pathways [60], the clinical cases consistently show some overlap with TMA and MCD in both cases of systemic and intravitreal VEGF blockade [10–14, 23].

Overall, these studies suggest an urgent need for closer examination of the pathological effects of long-term VEGF suppression with intravitreal injections [23]. Clinical guidelines are also needed to reduce renal risk in patients where VEGF blockade is needed to maintain acceptable vision [23]. Studies on the use of ranibizumab, with its theoretically improved safety profile, are especially needed [23]. The lack of uniform study results in the literature is an acknowledgment of the complexity of the problem [11, 15–18, 21, 23, 31–34, 36, 37, 39–41, 61]. Despite limited data, risks of intravitreal VEGF inhibition can be approximated to be near 14% for hypertension worsening and 14–45% for proteinuria worsening [31, 33, 37]. The risks are lower than systemic VEGF inhibition administration, where 23.6% of patients have worsening hypertension and 21–63% have worsening proteinuria [62, 63, 64].

There are several gaps in knowledge, the most pressing being the event rate of glomerular disease and proteinuria worsening. The second aspect that needs clarification is which patients tend to absorb VEGF inhibitors intravitreally, and whether there are other modulating factors that need to be considered (disease state). Unique variations in sensitivity to aberrations in VEGF signaling within each patient are also a theoretical point of difference. The variability in systemic exposure of intravitreally injected VEGF inhibitor is another key point of interest [11, 23, 56].

One study that took a step in documenting the observed physiologic changes with VEGF depletion was Bagheri et al. [31]; they reported the change in proteinuria as a continuous variable, rather than as KDIGO categories. Interestingly, this study revealed statistically significant changes in diastolic blood pressure similar to the earlier study of Rasier et al. [31, 33]. Of note, this study also showed changes in hematological parameters (hemoglobin and platelet count) [31]. This observation is consistent with known endothelial effects of VEGF blockade and can provide additional mechanisms for the pro-thrombotic effects suggested by the studies of Hanhart et al. [23, 39–41].

A study that would have the best chance of documenting the systemic effects of intravitreal VEGF inhibition with a reasonable level of confidence would be complex. Kameda et al. [36] suggest the need to look at renal function chronically and to assess acute and subacute renal injury markers (besides proteinuria). Glassman et al. [37] suggest the need to look at proteinuria as a continuous variable, rather than as a categorical measure. Bagheri et al. [31] suggest the need to confirm VEGF inhibition, and Avery et al. [16, 17] suggest the need to measure drug levels after intravitreal injection. O’Neill et al. [38] suggest the need to look at the changes in proteinuria prospectively. Given these considerations, a well-designed study to adequately assess the systemic effects of intravitreal VEGF inhibition would need to be well controlled. It also must be well powered, especially if the event rate is low or the effects are mostly detected in a subgroup of patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Ethics approval and consent to participate: not applicable. This research work does not contain human subject research material, as it is an individual anonymized case series. Ethical permission/consent for publication: IRB permission was not applied for as it is not required for individual case reports or case series with three patients or less in our institution (University of California, Los Angeles). Consent was obtained from the patient and documented, on condition that no identifiable data be published. Availability of data and materials: not applicable, no data.

FUNDING

I.K. is supported in part by funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01-DK077162), the Allan Smidt Charitable Fund, the Factor Family Foundation and the Ralph Block Family Foundation. Sponsorship: this work was not sponsored. I.K. is supported in part by funds from the NIH (R01-DK077162), the Allan Smidt Charitable Fund, the Factor Family Foundation and the Ralph Block Family Foundation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rowley WR, Bezold C, Arikan Y et al. Diabetes 2030: insights from yesterday, today, and future trends. Popul Health Manag 2017; 20: 6–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kempen JH, O’Colmain BJ, Leske MC et al. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122: 552–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nazimek-Siewniak B, Moczulski D, Grzeszczak W. Risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in Type 2 diabetes: results of longitudinal study design. J Diabetes Complicat 2002; 16: 271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ching J. Diabetic nephropathy: scope of the problem In: Lerma E, Batuman V (eds). Diabetes and Kidney Disease. New York, NY: Springer, 2014; 258–263 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yousefzadeh G, Shokoohi M, Najafipour H. Inadequate control of diabetes and metabolic indices among diabetic patients: a population based study from the Kerman Coronary Artery Disease Risk Study (KERCADRS). Int J Health Policy Manag 2014; 4: 271–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hung CC, Lin HY, Hwang DY et al. Diabetic retinopathy and clinical parameters favoring the presence of diabetic nephropathy could predict renal outcome in patients with diabetic kidney disease. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Skyler JS. Diabetic complications. The importance of glucose control. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1996; 25: 243–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mima A, Kitada M, Geraldes P et al. Glomerular VEGF resistance induced by PKCdelta/SHP-1 activation and contribution to diabetic nephropathy. Faseb J 2012; 26: 2963–2974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stewart MW. Treatment of diabetic retinopathy: recent advances and unresolved challenges. World J Diabetes 2016; 7: 333–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selamet U, Hanna RM, Rastogi A et al. Chapter 26: Chemotherapeutic Agents and the Kidney. In: Lapsia V, Jaar B, Ahsan Ejaz A (eds) Kidney Protection. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanna RM, Lopez E, Hasnain H et al. Three patients with injection of intravitreal vascular endothelial growth facto inhibitors and subsequent exacerbation of chronic proteinuria and hypertension. Clin Kidney J 2018; 12: 92–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hanna RM, Lopez E, Wilson J et al. Minimal change disease onset observed after bevacizumab administration. Clin Kidney J 2016; 9: 239–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hanna RM, Selamet U, Hasnain H et al. Development of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and thrombotic microangiopathy in a liver transplant patient on sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. Transplant Proc 2018; 50: 4033–4037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hanna RM, Yanny B, Barsoum M et al. Everolimus worsening chronic proteinuria in patient with diabetic nephropathy post liver transplantation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2019; 30: 989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avery RL. What is the evidence for systemic effects of intravitreal anti-VEGF agents, and should we be concerned? Br J Ophthalmol 2014; 98: i7–i10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Avery RL, Castellarin AA, Steinle NC et al. Systemic pharmacokinetics following intravitreal injections of ranibizumab, bevacizumab or aflibercept in patients with neovascular AMD. Br J Ophthalmol 2014; 98: 1636–1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Avery RL, Castellarin AA, Steinle NC et al. Systemic pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravitreal aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab. Retina 2017; 37: 1847–1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Avery RL, Gordon GM. Systemic safety of prolonged monthly anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for diabetic macular edema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016; 134: 21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jampol LM, Glassman AR, Liu D et al. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations after intravitreous anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2018; 7: 1054–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rogers CS, Reeves BC, Downes S et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the IVAN trial; relationships with drug, dosing, and systemic serious adverse events. Ophthalmol Retina 2018; 2: 118–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zehetner C, Kralinger MT, Modi YS et al. Systemic levels of vascular endothelial growth factor before and after intravitreal injection of aflibercept or ranibizumab in patients with age-related macular degeneration: a randomised, prospective trial. Acta Ophthalmol 2015; 93: e154–e159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avastin FDA package Insert. 2004.

- 23. Hanna RM, Barsoum M, Arman F et al. Nephrotoxicity induced by intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors: emerging evidence. Kidney Int 2019; 96: 572–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eylea FDA package Insert. 2011

- 25.Lucentis FDA package Insert. 2012

- 26. Garcia-Quintanilla L, Luaces-Rodriguez A, Gil-Martinez M et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravitreal anti-VEGF drugs in age-related macular degeneration. Pharmaceutics 2019; 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drug Bank. Bevacizumab. https://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00112 (1 March 2020, date last accessed)

- 28. Hirano T, Toriyama Y, Iesato Y et al. Changes in plasma vascular endothelial growth factor level after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab, aflibercept, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. Retina 2018; 38: 1801–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jampol LM, Glassman AR, Liu D et al. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations after intravitreous anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2018; 125: 1054–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tschulakow A, Christner S, Julien S et al. Effects of a single intravitreal injection of aflibercept and ranibizumab on glomeruli of monkeys. PLoS One 2014; 9: e113701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bagheri SD, Afarid M, Sagheb MM. Proteinuria and renal dysfunction after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab in patients with diabetic nephropathy: a prospective observational study. Galen Med J 2018; 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee K, Yang H, Lim H et al. A prospective study of blood pressure and intraocular pressure changes in hypertensive and nonhypertensive patients after intravitreal bevacizumab injection. Retina 2009; 29: 1409–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rasier R, Artunay O, Yuzbasioglu E et al. The effect of intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) administration on systemic hypertension. Eye (Lond) 2009; 23: 1714–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Risimic D, Milenkovic S, Nikolic D et al. Influence of intravitreal injection of bevacizumab on systemic blood pressure changes in patients with exudative form of age-related macular degeneration. Hellenic J Cardiol 2013; 54: 435–440 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shah AR, Van Horn AN, Verchinina L et al. Blood pressure is associated with receiving intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment in patients with diabetes. Ophthalmol Retina 2019; 3: 410–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kameda Y, Babazono T, Uchigata Y, et al. Renal function after intravitreal administration of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. J Diabetes Investig 2018; 9: 937–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glassman AR, Liu D, Jampol LM et al. ; for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Changes in blood pressure and urine albumin-creatinine ratio in a randomized clinical trial comparing aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018; 59: 1199–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O’Neill RA, Gallagher P, Douglas T et al. Evaluation of long-term intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections on renal function in patients with and without diabetic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 2019; 20: 478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hanhart J, Comaneshter DS, Freier Dror Y et al. Mortality in patients treated with intravitreal bevacizumab for age-related macular degeneration. BMC Ophthalmol 2017; 17: 189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hanhart J, Comaneshter DS, Freier-Dror Y et al. Mortality associated with bevacizumab intravitreal injections in age-related macular degeneration patients after acute myocardial infarct: a retrospective population-based survival analysis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2018; 256: 651–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hanhart J, Comaneshter DS, Vinker S. Mortality after a cerebrovascular event in age-related macular degeneration patients treated with bevacizumab ocular injections. Acta Ophthalmol 2018; 96: e732–e739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dalvin LA, Starr MR, AbouChehade JE et al. Association of intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy with risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and death in patients with exudative age-related macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019; 137: 483–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Starr MR, Dalvin LA, AbouChehade JE et al. Classification of strokes in patients receiving intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2019; 50: e140–e157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cheungpasitporn W, Chebib FT, Cornell LD et al. Intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy may induce proteinuria and antibody mediated injury in renal allografts. Transplantation 2015; 99: 2382–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network; Scott IU, Edwards AR, Beck RW et al. A phase II randomized clinical trial of intravitreal bevacizumab for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2007; 114: 1860–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Georgalas I, Papaconstantinou D, Papadopoulos K et al. Renal injury following intravitreal anti-VEGF administration in diabetic patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and chronic kidney disease–a possible side effect? Curr Drug Saf 2014; 9: 156–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jamrozy-Witkowska A, Kowalska K, Jankowska-Lech I et al. Complications of intravitreal injections–own experience. Klin Oczna 2011; 113: 127–131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kenworthy J-A, Davis J, Chandra V et al. Worsening proteinuria following intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy for diabetic macular edema. J Vitreoretin Dis 2019; 3: 54–56 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Khneizer G, Al-Taee A, Bastani B. Self limited membranous nephropathy after intravitreal nephropathy after intravitreal bevacizumab therapy for age related macular degeneration. J Nephropathol 2017; 6: 134–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morales E, Moliz C, Gutierrez E. Renal damage associated to intravitreal administration of ranibizumab. Nefrologia 2017; 37: 653–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nobakht NN, Kamgar M, Abdelnour L et al. Development of collapsing focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis in a patient receiving intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor blockade. Kidney Int Rep 2019; 4:1 508–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pellé G, Shweke N, Van Huyen J-PD et al. Systemic and kidney toxicity of intraocular administration of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 57: 756–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perez-Valdivia MA, Lopez-Mendoza M, Toro-Prieto FJ et al. Relapse of minimal change disease nephrotic syndrome after administering intravitreal bevacizumab. Nefrologia 2014; 34: 421–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sato T, Kawasaki Y, Waragai T et al. Relapse of minimal change nephrotic syndrome after intravitreal bevacizumab. Pediatr Int 2013; 55: e46–e48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Thadhani R, Hagmann H, Schaarschmidt W et al. Removal of soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 by dextran sulfate apheresis in preeclampsia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27: 903–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hanna RM, Abdelnour L, Hasnain H et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab-induced exacerbation of proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy, and amelioration by switching to ranibizumab. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 2020; 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Touzani F, Geers C, Pozdzik A. Intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF antibody induces glomerular endothelial cells injury. Case Rep Nephrol 2019; 2019: 1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tran T. Intravitreal VEGF inhibitor causing allergic interstitial nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 2017; 69: A99 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yen W., Zhang Pl; Intravitreal Injection of Avastin (IIA) over Time Can Be Associated with Thrombotic Microangiopathy (TMA) in the Native Kidney. ASN Kidney Week; JASN, Washington, DC, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ollero M, Sahali D. Inhibition of the VEGF signalling pathway and glomerular disorders. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1449–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu S, Kim C, Baer L et al. Bevacizumab increases risk for severe proteinuria in cancer patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21: 1381–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Izzedine H, Massard C, Spano JP et al. VEGF signalling inhibition-induced proteinuria: mechanisms, significance and management. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46: 439–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ranpura V, Pulipati B, Chu D et al. Increased risk of high-grade hypertension with bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 2010; 23: 460–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chung YR, Kim YH, Byeon HE, Jo DH, Kim JH, Lee K. Effect of a single intravitreal injection of bevacizumab on proteinuria in patients With diabetes. Tranls Vis Sci Technol 2020; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]