Abstract

Background

Stable, affordable housing is an established determinant of health. As affordable housing shortages across the USA threaten to displace people from their homes, it is important to understand the implications of cost-related residential moves for healthcare access.

Objective

To examine the relationship between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs.

Design

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of 7 waves (2011–2017) of the California Health Interview Survey.

Participants

We included all respondents ages 18 and older.

Main Measures

The primary predictor variable was residential move history in the past 5 years (cost-related move, non-cost-related move, or no move). The primary outcome was unmet medical needs in the past year (necessary medications and/or medical care that were delayed or not received).

Key Results

Our sample included 146,417 adults (42–47% response rate), representing a weighted population of 28,518,590. Overall, 20.3% of the sample reported unmet medical needs in the past year, and 4.9% reported a cost-related move in the past 5 years. In multivariable logistic regression models, adjusted risk of unmet medical needs increased for adults with both cost-related moves (aOR 1.38; 95% CI 1.19–1.59) and non-cost-related moves (aOR 1.17; 95% CI 1.09–1.26) compared to those with no moves. Among people who had moved, those with cost-related moves were more likely to report unmet medical needs compared to people with non-cost-related moves (p = 0.03).

Conclusions

People who have moved due to unaffordable housing represent a population at increased risk for unmet medical needs. Policy makers seeking to improve population health should consider strategies to limit cost-related moves and to mitigate their adverse effects on healthcare access.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-020-06347-3.

KEY WORDS: affordable housing, housing cost, displacement, access to care, delayed care

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, widespread affordable housing shortages have impacted a growing number of Americans and exposed the ties between housing and health disparities.1,2 People who cannot afford their housing are at risk for undergoing cost-related residential moves, whether in response to formal processes, such as evictions and foreclosures, or informal forces, such as excessive rent increases or personal financial challenges. In 2016, approximately 2.3 million people in the USA moved in search of less expensive housing, while another 283,000 moved due to foreclosure or eviction.3 The threat of losing one’s home due to unaffordable housing is magnified in California, where over 40% of households meet criteria for high housing cost burden.1

In addition to being at risk for moving, people who struggle to pay for housing face increased barriers to meeting their medical needs.4–9 However, it is unclear whether cost-related moves help people restore access to necessary medical care or contribute to ongoing access challenges. Besides one study from Philadelphia, which showed an association between mortgage foreclosure and increased risk of unmet medical needs,9 few studies have examined the consequences of cost-related moves for healthcare access. While evictions are clearly linked to poor mental and physical health outcomes,10 impaired access to medical care—a potential mediator of this effect—has not specifically been examined in the evictions context. Even less is known about the medical needs of people undergoing informal cost-related moves. Furthermore, whether cost-related moves are more disruptive than other types of moves remains unknown.

In this study, we used a population-based sample of California adults at the peak of the affordable housing crisis1,11 to describe the association between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs, defined as having delayed or not received necessary medications or medical care. While all moves are acutely disruptive events12 with the potential to interrupt access to medical care, we hypothesized that the circumstances surrounding cost-related moves might be particularly burdensome, resulting in geographic, logistical, financial, and psychological barriers to fulfilling medical needs.13 We compared unmet medical needs among people with recent cost-related moves versus people with non-cost-related moves and versus those who did not move. We also hypothesized that higher income, better general health, moves within the same neighborhood, and longer time since a move might attenuate the association between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs. Consequently, we explored whether the relationship between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs differed by income and general health (individual characteristics) and by shorter or longer time since move and moves within the same neighborhood versus to a new neighborhood (move-related factors).

METHODS

Data and Study Population

This was a cross-sectional analysis of data from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) from 2011 to 2017.14 We included all participants ages 18 and older. CHIS, the country’s largest state health survey, used multistage geographic stratification and random-digit dialing via landline and cell phone to interview California households in English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Tagalog. The sampling frame excluded individuals without a phone, college students, people experiencing homelessness, and those living in institutionalized settings.15 We evaluated 2011–2017 data because they contained questions relevant to cost-related moves. All measures were self-reported except where noted. CHIS provided imputed values for all missing responses via a combination of logical and hot-deck imputation (reported by CHIS as < 1–2% for most variables but greater than 20% for household income in the 2011–2014 survey waves).15

Measures

Residential Move History

The primary predictor was move history in the past 5 years. Following methods established for other surveys,16 we constructed this variable from the items, “About how long have you lived at your current address?” and “The last time you moved, what was your main reason for moving?” We operationalized move history as a 3-level variable: (1) cost-related move (people who moved in the past 5 years because they “couldn’t afford mortgage/rent”), (2) non-cost-related move (people who moved in the past 5 years for reasons other than housing cost), or (3) no move (people who did not move in the past 5 years) (Supplement, eTable 1).

Unmet Medical Needs

The primary outcome was unmet medical needs. We regarded participants as having unmet medical needs if they responded affirmatively to either of two yes/no questions: “During the past 12 months, did you delay or not get a medicine that a doctor prescribed for you?” or “During the past 12 months, did you delay or not get any other medical care you felt you needed—such as seeing a doctor, a specialist, or other health professional?” (Supplement, eTable 1). Respondents answering yes to either question were asked whether or not the unmet need was due to “cost or lack of insurance” (yes/no).

Covariates

We included gender, age, race/ethnicity, employment, income, education, household composition, urbanicity, health insurance type, having a usual source of medical care, general health, and survey wave (Supplement, eTable 1) in multivariable models.

Moderators

We assessed income (collapsed to tertiles) and general health (dichotomized) as individual characteristics that might modify the relationship between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs (Supplement, eTable 1). We also created indicators that accounted for (1) move history by neighborhood change (moves within the same neighborhood versus to a new neighborhood) as well as (2) move history by time since move (0–6, 7–12, 13–24, or 25–59 months) to capture move-related characteristics that might influence our findings (Supplement, eTable 1).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses incorporated survey weights specific to each wave of data collection to account for the sampling design and generate accurate variance estimates.

Unmet Medical Needs

First, we described characteristics related to demographics, residential moves, and medical care with univariate and bivariate statistics. We then performed multivariable logistic regression to compare odds of unmet medical needs by move history, using “no move” as reference and adjusting for all covariates. We then compared the coefficients for cost-related moves and non-cost-related moves.

Moderation Analyses

To assess whether individual characteristics influenced the relationship between move history and unmet medical needs, we regressed unmet medical needs on move history within subsamples stratified by income and general health. To examine differences in unmet medical needs by move-related characteristics, we repeated the primary regression models using the indicators for move history by neighborhood change as well as move history by time since move. For all moderation analyses, we compared the coefficients for cost-related moves across strata using Wald tests.

Sensitivity Analyses

To assess the validity of our composite unmet medical needs outcome, we repeated separate multivariable analyses for the components of the composite outcome: unmet medication needs and other unmet medical needs.

Next, we checked the robustness of our results to two alternate definitions of cost-related moves. First, we repeated the multivariable analyses with a broadened “housing-related moves” predictor that expanded the “cost-related moves” category to include people who reported moving because of “changes in renting/lease” (coded from write-in responses) and “other housing related” reasons (Supplement, eTable 1). Second, because unmet medical needs were reported for the last year but moves were reported for the last 5 years, we were unable to confirm whether a move that occurred within the last year preceded a reported unmet medical need. In order to focus on moves that preceded the most recent unmet medical need, we generated alternate predictors for people who had cost-related and non-cost-related moves in the past 13–59 months only (Supplement, eTable 1).

We performed all analyses using Stata version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Our analytic sample of 146,417 adults corresponded to a weighted population of 28,518,590 individuals (Table 1). The response rate among eligible individuals ranged from 42.3 to 47.4%.15 Cost-related moves were reported by 4.9% of the sample, and 35.2% reported non-cost-related moves (Table 2). Analyses stratified by move history showed that people with cost-related moves were generally younger, less white, more likely to have several children, less educated, lower income, more often unemployed and uninsured, and in worse health (Table 1). About half of all recent moves occurred within the past year, while over three-quarters of moves occurred within the same neighborhood (Table 2).

Table 1.

Weighted Demographic Characteristics of Adult California Health Interview Survey Respondents, 2011–2017

| Variable | Total sample (n = 146,417), % |

Residential move history | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost-related move (n = 7,131), % |

Non-cost-related move (n = 51,568), % |

No move (n = 87,718), % |

χ2 test, p |

||

| Gender | < 0.01 | ||||

| Female | 51.2 | 50.5 | 49.4 | 52.3 | |

| Age (years) | < 0.01 | ||||

| 18–34 | 32.0 | 44.1 | 48.0 | 21.6 | |

| 35–44 | 17.6 | 20.8 | 22.3 | 14.6 | |

| 45–64 | 33.5 | 28.3 | 22.4 | 40.4 | |

| ≥ 65 | 17.0 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 23.4 | |

| Race/ethnicity | < 0.01 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 42.8 | 27.2 | 38.3 | 46.7 | |

| Hispanic | 34.8 | 49.4 | 36.3 | 32.7 | |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 14.0 | 11.7 | 15.8 | 13.1 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 5.6 | 8.9 | 6.4 | 4.9 | |

| Other/multiple | 2.8 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.6 | |

| Adults in household | < 0.01 | ||||

| 1 | 14.2 | 17.6 | 16.3 | 12.7 | |

| 2 | 43.9 | 36.8 | 45.8 | 43.4 | |

| 3 or more | 41.9 | 45.5 | 37.9 | 43.9 | |

| Children in household | < 0.01 | ||||

| 0 | 60.9 | 54.0 | 55.4 | 64.7 | |

| 1 | 16.2 | 17.4 | 17.8 | 15.1 | |

| 2 | 13.9 | 14.5 | 15.8 | 12.8 | |

| 3 or more | 9.0 | 14.2 | 11.0 | 7.4 | |

| Educational attainment | < 0.01 | ||||

| Less than high school | 23.1 | 25.2 | 15.2 | 16.0 | |

| High school diploma | 23.3 | 25.4 | 22.7 | 23.4 | |

| Some college | 24.4 | 26.6 | 24.4 | 24.2 | |

| BA or BS degree | 22.3 | 16.7 | 24.3 | 21.6 | |

| Any graduate school | 13.9 | 6.1 | 13.4 | 14.8 | |

| Employment | < 0.01 | ||||

| Full-time | 54.4 | 54.2 | 61.6 | 50.3 | |

| Part-time or other | 9.2 | 10.2 | 8.8 | 9.3 | |

| Not employed | 36.4 | 35.7 | 29.7 | 40.4 | |

| Income as % of FPL | < 0.01 | ||||

| < 100 | 16.5 | 32.4 | 20.2 | 13.0 | |

| 100–200 | 19.5 | 28.5 | 20.6 | 18.1 | |

| 201–400 | 24.4 | 22.9 | 23.9 | 24.8 | |

| 401–600 | 15.4 | 8.4 | 14.3 | 16.6 | |

| > 600 | 24.2 | 7.9 | 21.0 | 27.5 | |

| Urbanicity | 0.01 | ||||

| Urban (vs. rural) | 90.0 | 91.8 | 90.8 | 89.4 | |

FPL federal poverty level. Unweighted sample sizes are shown. All frequencies reflect weighted estimates based on all adult respondents in the pooled 2011–2017 California Health Interview Survey (weighted N = 28,518,590)

Table 2.

Weighted Residential Move Characteristics, Medical Characteristics, and Unmet Medical Needs of Adult California Health Interview Survey Respondents, 2011–2017

| Variable | Total sample (n = 146,417), % |

Residential move history | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost-related move (n = 7131), % |

Non-cost-related move (n = 51,568), % |

No move (n = 87,718), % |

χ2 test, p |

||

| Characteristics of residential moves in the past 5 years | |||||

| Move history | n/a | ||||

| Cost-related move | 4.9 | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Non-cost-related move | 35.2 | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| No move | 59.9 | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Time since last move | < 0.01 | ||||

| 0–6 months | 8.3 | 21.3 | 20.7 | n/a | |

| 7–12 months | 9.2 | 24.8 | 22.6 | n/a | |

| 13–24 months | 9.6 | 24.2 | 23.8 | n/a | |

| 25–59 months | 13.0 | 29.6 | 32.9 | n/a | |

| Did not move in the past 5 years | 59.9 | n/a | n/a | 100 | |

| Neighborhood change* | < 0.01 | ||||

| Moved to new neighborhood | 19.8 | 23.8 | 19.3 | n/a | |

| Moved within neighborhood | 80.2 | 76.2 | 80.7 | n/a | |

| Medical characteristics | |||||

| Health insurance | < 0.01 | ||||

| Employer-based | 44.2 | 26.4 | 45.8 | 44.7 | |

| Medicaid alone | 15.9 | 30.1 | 20.2 | 12.1 | |

| Not insured | 13.6 | 27.1 | 16.7 | 10.7 | |

| Medicare + other | 11.5 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 16.6 | |

| Privately purchased | 6.5 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 6.6 | |

| Medicaid + Medicare | 4.6 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 5.3 | |

| Medicare or other public alone | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 4.0 | |

| Has a usual source of care† | < 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 83.0 | 71.3 | 77.4 | 87.2 | |

| General health | < 0.01 | ||||

| Good, very good, or excellent (vs. poor or fair) | 79.6 | 69.7 | 81.5 | 79.3 | |

| Unmet medical needs | |||||

| Unmet medical need in the past year | < 0.01 | ||||

| Any unmet medical need | 20.3 | 27.2 | 22.7 | 18.4 | |

| Unmet medication need | 10.9 | 15.8 | 11.8 | 10.0 | |

| Other unmet medical need | 13.7 | 18.8 | 15.9 | 12.0 | |

| Was unmet medical need due to cost or lack of insurance? | < 0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 9.3 | 16.8 | 10.6 | 7.9 | |

| No | 11.0 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 10.5 | |

| n/a: No unmet medical need | 79.7 | 72.8 | 77.4 | 81.6 | |

ED emergency department, UC urgent care. Unweighted sample sizes are shown. All frequencies reflect weighted estimates based on all adult respondents in the pooled 2011–2017 California Health Interview Survey (weighted N = 28,518,590)

*Among people who moved in the past 5 years (unweighted N = 58,699)

†Other than the emergency department or urgent care

Unmet Medical Needs

Unmet medical needs were reported by 27.2% of participants with cost-related moves, 22.7% of those with non-cost-related moves, and 18.4% of those who did not move (Table 2).

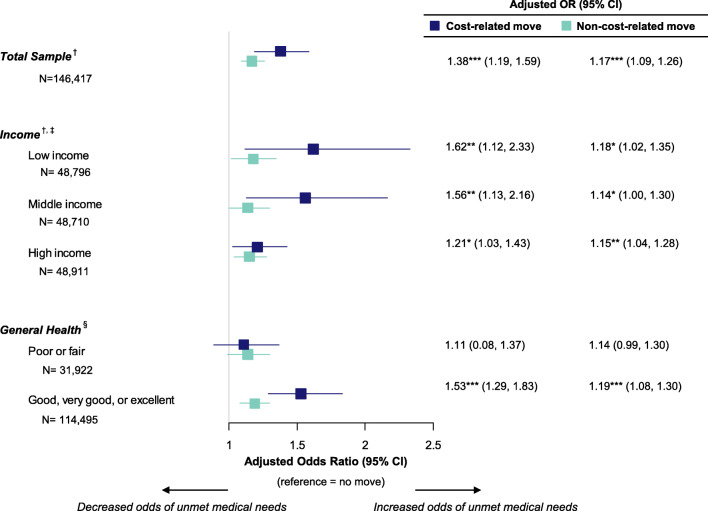

In adjusted analyses, compared to people who did not move, odds of unmet medical needs were increased by 38% (95% CI 19%, 59%) for people with cost-related moves and by 17% (95% CI 9%, 26%) for people with non-cost-related moves (Fig. 1). The magnitude of the association between unmet medical needs and moves was significantly larger for cost-related moves than for non-cost-related moves (p = 0.03).

Figure 1.

Odds ratios of unmet medical needs relative to no move: total sample and stratified by individual characteristics. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Unweighted sample sizes are shown; all other values reflect weighted estimates. Source: Adult California Health Interview Survey, 2011–2017. †Odds ratios adjusted for gender, age, age squared, race/ethnicity, employment, log of income as percent of federal poverty level, education, number of adults in household, number of children in household, neighborhood type, health insurance, having a usual source of care, general health status, and survey wave. ‡Household income as percent of federal poverty level (FPL) stratified by tertiles, roughly corresponding to < 200% of FPL, 200–399% of FPL, and ≥ 400% of FPL. §Odds ratios adjusted for gender, age, age squared, race/ethnicity, employment, log of income as percent of federal poverty level, education, number of adults in household, number of children in household, neighborhood type, health insurance, having a usual source of care, and survey wave.

Moderation Analyses

In income-stratified analyses, odds of unmet medical needs were higher for people with cost-related moves versus people with no moves across all income tertiles (aOR [95% CI] for low income, 1.62 [1.12, 2.33]; middle income, 1.56 [1.13, 2.16]; high income, 1.21 [1.03, 1.43]) (Fig. 1). The coefficients for cost-related moves did not differ significantly by income tertile (p = 0.72).

In analyses stratified by general health, cost-related moves were associated with increased odds of unmet medical needs (compared to people who did not move) among people in better health (aOR 1.53 [95% CI 1.29, 1.83]) (Fig. 1). Among people with worse health, odds of unmet medical needs did not significantly differ by move history (aOR 1.11 [95% CI 0.08, 1.37]) (Fig. 1). The cost-related move coefficients differed significantly by general health status (p = 0.01).

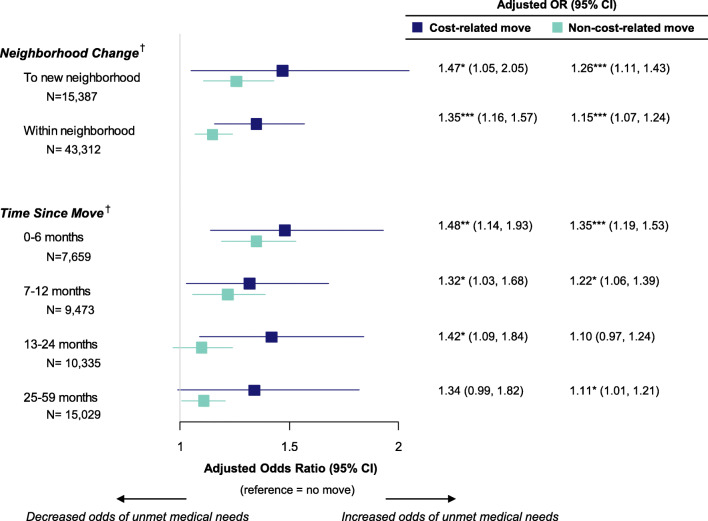

In analyses stratified by neighborhood change, compared to people who did not move, those with cost-related moves had increased odds of unmet medical needs, regardless of whether they moved to a new neighborhood or within the same neighborhood (aOR [95% CI] for moves to new neighborhood, 1.47 [1.05, 2.05]; within neighborhood, 1.35 [1.16, 1.57]) (Fig. 2). These odds did not differ significantly for moves within the same neighborhood versus moves to a new neighborhood (p = 0.64).

Figure 2.

Odds ratios of unmet medical needs relative to no move: stratified by move characteristics. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Unweighted sample sizes are shown; all other values reflect weighted estimates. Source: Adult California Health Interview Survey, 2011–2017. †Odds ratios adjusted for gender, age, age squared, race/ethnicity, employment, log of income as percent of federal poverty level, education, number of adults in household, number of children in household, neighborhood type, health insurance, having a usual source of care, general health condition, and survey wave.

Analyses by time since move showed that having a cost-related move was associated with increased odds of unmet medical needs for at least 24 months after moving, relative to no move (aOR [95% CI] for 0–6 months, 1.48 [1.14, 1.93]; 7–12 months, 1.32 [1.03, 1.68]; 13–24 months, 1.42 [1.09, 1.84]; 25–59 months, 1.34 [0.99, 1.82]) (Fig. 2). These odds did not differ significantly across time-since-move strata (p = 0.90).

Sensitivity Analyses

Cost-related moves and non-cost-related moves remained significant predictors of the separate “unmet medication needs” and “other unmet medical needs” outcomes compared to those who did not move (Supplement, eTable 2). Compared to non-cost-related moves, cost-related moves were associated with greater odds of unmet medication needs but not of other unmet medical needs (Supplement, eTable 2).

The positive association between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs relative to people who did not move was robust to alternate specifications of the primary predictor, including a broader definition of cost-related moves and a narrower definition for moving window (moves only in the past 13–59 months) (Supplement, eTable 3 and eTable 4). However, coefficients for the alternatively specified primary predictors did not differ significantly from those for non-cost-related moves. Distinguishing between cost-related and non-cost-related moves was thus less important when housing-related moves were defined more inclusively or when the most recent moves were excluded.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study from 2011 to 2017, nearly one in twenty California adults moved due to unaffordable housing costs in the past 5 years. This population, equivalent to a staggering 1.4 million people per year in California alone, was more likely than those who did not move and those who moved for other reasons to report unmet medical needs in adjusted analyses. This is consistent with prior work focused on people undergoing mortgage foreclosure.9

There are several reasons why residential moves, and particularly cost-related moves, might disrupt the receipt of medical care. First, the financial toll of moving (e.g., rental security deposits and time off of work) may exacerbate underlying hardship, making it harder for people with cost-related moves (who likely have less of a buffer to absorb additional costs) to later pay for medical services. Housing instability can also lead to job instability, perpetuating economic adversity.17 However, the fact that even high-income individuals were not fully buffered from this risk in our moderation analyses suggests that additional mechanisms should be considered.

A second potential explanation is that job changes (e.g., changes in hours or income) might lead to both cost-related moves and unmet medical needs. Alternatively, people undergoing cost-related moves might make pragmatic changes to their working or living arrangements (such as working increased hours or living farther from familiar medical facilities) that stabilize their financial and housing needs but make it harder to access medical care. Persistence of the association between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs for people who moved within the same neighborhood suggests that any new working or living arrangements associated with cost-related moves may disrupt medical needs more through time demands (e.g., longer commutes) and/or increased stress12 than through loss of neighborhood familiarity or geographic access to resources. However, for people who move to new neighborhoods, the need to establish care with a new provider or travel farther for care could be an added barrier to addressing medical needs, especially for those who change or lose their jobs and health insurance.

Finally, our findings may reflect a natural response to stress amid competing priorities. Under conditions of scarcity, most people prioritize subsistence needs, like food and housing, over medical needs.18,19 Housing, in particular, holds high personal value, and unwanted residential moves have been described as “displacement” and an experience of “affective, emotional and material rupture.”20 This is consistent with Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory, which holds that people experience distress when they lose things they value highly (“resources”).21,22 Indeed, prior work has linked unaffordable housing and cost-related moves to increased distress and adverse mental health outcomes.10,13,16,23–25 Furthermore, per COR Theory, because people must invest additional resources to obtain or protect resources, loss of resources begets more loss.21,22 Subsequently, if cost-related moves are experienced as resource loss, people undergoing them may invest in recovering or preserving shelter and money, perhaps at the expense of meeting their medical needs. COR Theory might also explain our finding that individuals in worse health, who might place greater value on their health as a scarcer resource, seemed to seek needed medical care regardless of cost-related moves, while those in better health might have been more willing to forgo care, at least in the short term, after cost-related moves.

An important strength of our study is our use of a metric capturing both formal and informal cost-related moves, thus expanding on prior studies to show that the relationship between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs persists more broadly. We also extend previous work by comparing people with cost-related moves to people with non-cost-related moves, showing that moves provoked by unaffordable housing may be more disruptive than other types of moves. Other strengths of this study include our ability to control for a large number of individual-level socioeconomic and health covariates and our use of a large population sample, which makes the results broadly generalizable.

Although our results do not demonstrate causality, they suggest that efforts may be needed not only to ensure healthcare delivery to people who have had to move because of unaffordable housing, but also to prevent cost-related moves in the first place. In the short term, interventions focused on health care delivery (e.g., enhanced telemedicine capacity, interoperable health records, social needs screening, and care coordination) have the potential to mitigate some of the harms of these moves. In the long run, public policy can help minimize healthcare disruption by preventing cost-related moves outright, such as through efforts to promote greater affordable housing supply (e.g., zoning reform and tax incentives) and enhanced tenant protections (e.g., rent stabilization, eviction protections, and medical-legal partnerships). Such interventions may be particularly urgent in light of widespread economic hardship during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has raised concerns about a looming eviction crisis26 that could exacerbate health disparities.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Regarding study design, the sample excluded populations experiencing some of the most harmful consequences of cost-related moves (e.g., homelessness), meaning that this work may underestimate the potential effects of these moves. Additionally, although response rates reported by CHIS are relatively low, previous studies have attributed these numbers to CHIS’s conservative response rate calculation methods15 and shown that major nonresponse bias is unlikely.27

Survey question language also posed limitations. First, survey questions did not allow us to distinguish formal (e.g., evictions) from informal (e.g., rent increases or income loss) cost-related moves, but our findings were robust to defining housing-related reasons for moves more broadly in sensitivity analyses. Additionally, survey wording limited our ability to exclude reverse causality; if, in some cases, unmet medical needs result in poor health, subsequent medical expenses and barriers to labor-force participation might lead to financial hardship28 that obligates cost-related moves, positively biasing our results. Even so, the relationship between cost-related moves and unmet medical needs could be bidirectional, such that either cost-related moves or unmet medical needs can trigger an escalating spiral of worse health and poverty. Finally, the self-reported measures introduce risk of bias. The high proportion of moves within the past year suggests that people reported moves as more recent than they actually were or that they forgot moves that happened longer ago (recall bias).

CONCLUSION

This analysis highlights the link between stable, affordable housing and healthcare, demonstrating that cost-related moves may be a modifiable driver of health disparities. Promoting health equity amidst an affordable housing crisis may require cross-sectoral collaboration among clinicians, public health leaders, housing agencies, and community advocates. Further investigation is needed to understand the downstream clinical effects of cost-related moves and to identify the most effective ways to mitigate harm and deliver necessary care to people who have had to move.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 25 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the California Health Interview Survey Data Access Center staff for assistance with analyzing the confidential survey data.

Funding

This study was funded by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center via the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethics Approval

This analysis was approved by the University of California, Los Angeles South General Institutional Review Board (IRB#11-002227).

Conflict of Interest

Joann Elmore, MD serves as Editor-in-Chief for adult primary care topics at UpToDate. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

This study was presented as a poster at the Society of General Internal Medicine California/Hawaii Regional Meeting in Irvine, California (January 25, 2020). This work was also accepted for a poster presentation at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine in Birmingham, Alabama (canceled due to COVID-19).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/28/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s11606-022-07747-3

References

- 1.HUD Office of Policy Development and Research. Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy Data. U.S. Housing and Urban Development. Published August 5, 2019. Accessed March 1, 2020. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/cp.html#2006-2016_query

- 2.Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. America’s Rental Housing 2020.; 2020. Accessed September 10, 2020. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2020.pdf

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. CPS Historical Migration/Geographic Mobility Tables. Published November 2019. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/geographic-mobility/historic.html

- 4.Meltzer R, Schwartz A. Housing Affordability and Health: Evidence From New York City. Hous Policy Debate. 2016;26(1):80–104. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2015.1020321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing Instability and Food Insecurity as Barriers to Health Care Among Low-Income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charkhchi P, Fazeli Dehkordy S, Carlos RC. Housing and Food Insecurity, Care Access, and Health Status Among the Chronically Ill: An Analysis of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):644–650. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin P, Liaw W, Bazemore A, Jetty A, Petterson S, Kushel M. Adults with Housing Insecurity Have Worse Access to Primary and Preventive Care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(4):521–530. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stahre M, VanEenwyk J, Siegel P, Njai R. Housing Insecurity and the Association With Health Outcomes and Unhealthy Behaviors, Washington State, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12. doi:10.5888/pcd12.140511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Pollack CE, Lynch J. Health Status of People Undergoing Foreclosure in the Philadelphia Region. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1833–1839. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desmond M, Kimbro RT. Eviction’s Fallout: Housing, Hardship, and Health. Soc Forces. 2015;94(1):295–324. doi: 10.1093/sf/sov044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor M.California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences. Legislative Analyst’s Office; 2015:44. . https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2015/finance/housing-costs/housing-costs.pdf

- 12.Rahe RH, Mahan JL, Arthur RJ. Prediction of near-future health change from subjects’ preceding life changes. J Psychosom Res. 1970;14(4):401–406. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(70)90008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nettleton S, Burrows R. When a Capital Investment Becomes an Emotional Loss: The Health Consequences of the Experience of Mortgage Possession in England. Hous Stud. 2000;15(3):463–478. doi: 10.1080/02673030050009285. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2011-2017 Confidential Data Files. Published online February 2020. http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/Pages/default.aspx

- 15.University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Health Policy Research. CHIS Methodology Reports (2011-2012, 2013-2014, 2015-2016, 2017-2018). Published 2019. https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Pages/methodology.aspx

- 16.Burgard SA, Seefeldt KS, Zelner S. Housing instability and health: Findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2215–2224. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desmond M, Gershenson C. Housing and Employment Insecurity among the Working Poor. Soc Probl. 2016;63(1):46–67. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spv025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(2):217–220. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, et al. The Impact of Competing Subsistence Needs and Barriers on Access to Medical Care for Persons With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Receiving Care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1270–1281. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott-Cooper A, Hubbard P, Lees L. Moving beyond Marcuse: Gentrification, displacement and the violence of un-homing. Prog Hum Geogr. Published online February 24, 2019:0309132519830511. doi:10.1177/0309132519830511

- 21.Hobfoll SE. Traumatic stress: A theory based on rapid loss of resources. Anxiety Res. 1991;4(3):187–197. doi: 10.1080/08917779108248773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvaro C, Lyons RF, Warner G, et al. Conservation of resources theory and research use in health systems. Implement Sci IS. 2010;5:79. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim S, Chan PY, Walters S, Culp G, Huynh M, Gould LH. Impact of residential displacement on healthcare access and mental health among original residents of gentrifying neighborhoods in New York City. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12). 10.1371/journal.pone.0190139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Taylor MP, Pevalin DJ, Todd J. The psychological costs of unsustainable housing commitments. Psychol Med. 2007;37(7):1027–1036. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bentley R, Baker E, Mason K, Subramanian SV, Kavanagh AM. Association Between Housing Affordability and Mental Health: A Longitudinal Analysis of a Nationally Representative Household Survey in Australia. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(7):753–760. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blasi G. UD Day: Impending Evictions and Homelessness in Los Angeles. UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy; 2020:37. Accessed September 10, 2020. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2gz6c8cv

- 27.Lee S, Brown ER, Grant D, Belin TR, Brick JM. Exploring Nonresponse Bias in a Health Survey Using Neighborhood Characteristics. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1811–1817. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bor J, Cohen GH, Galea S. Population health in an era of rising income inequality: USA, 1980–2015. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1475–1490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 25 kb)