Abstract

BACKGROUND

The gram-negative aerobic bacterium Moraxella osloensis is an opportunistic pathogen in brain tissues.

CASE SUMMARY

The gram-negative aerobic bacterium Moraxella osloensis was isolated from a patient’s brain tissue during a stereotactic biopsy.

CONCLUSION

This is the first report of a brain tissue infection with Moraxella osloensis possibly causing brain gliomatosis.

Keywords: Moraxella osloensis, Brain infection, Cerebral gliomatosis, Stereotactic brain biopsy, Case report

Core Tip: The gram-negative aerobic bacterium Moraxella osloensis is an opportunistic pathogen and was isolated from a patient’s brain tissue during a stereotactic biopsy. This is the first report of a brain tissue infection with Moraxella osloensis, possibly causing brain gliomatosis.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the recent advances in neuroimaging of the brain, an accurate diagnosis of focal brain lesions requires tissue sampling and histological verification in order to determine treatment modalities in neuro-oncology. Stereotactic biopsy is the gold standard for neuropathological diagnosis that guides the choice of management and avoids the risks of blind treatment. It is particularly reliable for diagnosing those lesions that cannot be removed through open surgery due to their location, depth and number, such as deeply located cerebral lesions, multifocal tumors and lesions located in eloquent areas[1,2].

Bacterial isolates from brain tissue are extremely rare[3]. The gram-negative aerobic bacterium Moraxella osloensis is considered an opportunistic human pathogen. Although this particular bacterium is very rarely encountered in clinical practice, there have been individual case reports of endophthalmitis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, pneumonia, central venous catheter infection, as well as bacteraemia caused by Moraxella osloensis, including three patients with meningitis[4-8]. However, it is not known whether this microbe may also be involved in tumorigeneses of brain tissue. The mechanism for such oncogenic transformation in Moraxella osloensis infections is not completely understood and it is supposed that the pathogenesis may be similar to that of oncogenic viruses or, alternatively, as a result of a long chronic low-grade infection that eventually results in uncontrolled growth[7]. We report a patient with gliomatosis cerebri and Moraxella osloensis isolated from the brain tissue. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of brain infection with this agent, which might be the reason for the brain gliomatotic alterations.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 74-year old lady was admitted to the Neurological Clinic of the University Medical Centre Ljubljana with a 3-mo history of gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, cognitive decline and mood changes.

History of present illness

The patient reported gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, cognitive decline and mood changes for the last three months.

History of past illness

No past illnesses were documented.

Personal and family history

Personal and family history was unremarkable, except for arterial hypertension.

Physical examination

On admission, the neurological examination revealed left hemiparesis with positive plantar response on the left. She walked with difficulty. The mental state examination found both an attention deficit and memory deficit. The lady was slow, uninterested and lacked spontaneity. Neuropsychological tests indicated frontal lobe syndrome.

Laboratory examinations

Microbiological cultures of the peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid were negative. Specific analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and blood excluded infection with Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum. The chest radiograph was normal. Systemic diseases and primary neoplasms elsewhere were ruled out and eventually, the patient was discharged.

After two months, she was referred to the Department of Neurosurgery of the University Medical Centre Maribor. On admission, she was immobile, slow and uninterested. The neurological examination revealed left central facial palsy and left hemiparesis. Repeated magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was similar to the first scan.

Routine blood chemistry tests were also performed and all the results were within the reference range, as were the sedimentation rate and hematological tests. The laboratory tests showed normal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, B12 and folic acid. The cerebrospinal fluid was clear with a normal protein concentration (protein, 0.28 g/L; lactate, 1.8 mmol/L; glucose, 3.7 mmol/L; 1 lymphocyte/μL).

Imaging examinations

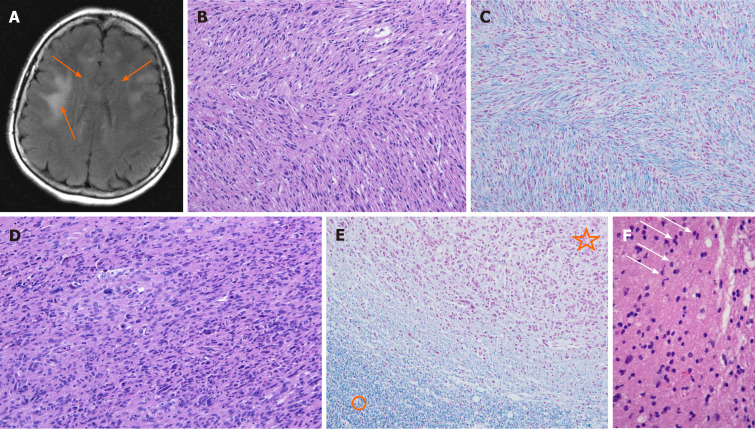

Neuroradiological investigations revealed multifocal brain lesions. Computed tomography (CT) shown bilateral hypodense and poorly defined subcortical brain alterations. Initial MRI, obtained seven days after admission, demonstrated some small focal areas of high intensity on T2-weighted imaging and on fluid attenuation inversion recovery sequences, located in the periventricular region of both frontal lobes. No contrast enhancement was evident (Figure 1A). Cerebral perfusion scintigraphy revealed only minimal changes in brain perfusion in the frontal region, which could have coincided with frontotemporal dementia.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging, T2-weighted sequence, stereotactic brain biopsy, and post-mortem brain changes in the patient. A: Magnetic resonance imaging revealed some focal areas of high intensity in the white matter of both frontal lobes (arrows) on T2-weighted sequence; B and C: Microscopic feature of cerebral gliomatosis in the genu of the corpus callosum: Hypercellular white matter with tumor cells in between the myelinated fibers [hematoxylin and eosin (H/E) staining and Klüver-Barrera staining, respectively]; D: Microscopic feature of malignant glioma in the splenium of the corpus callosum: Hypercellular tumor composed of polymorphic and some multinucleated tumor cells with brisk mitotic activity (H/E); E: There were no myelinated nerve fibers inside the tumor mass (upper part, star) compared to the adjacent white matter (lower part, circle) (Klüver-Barrera); F: Hypercellular white matter with slightly polymorphic nuclei (arrows) suspected for infiltrating neoplastic glial cells.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The autopsy revealed massive pulmonary thromboembolism on both sides. The post mortem examination of the central nervous system showed thrombosis of the left middle cerebral artery with a consequent acute hemorrhagic left hemispheric brain infarction and thickened corpus callosum. Microscopic analysis revealed widespread neoplastic astrocytic growth, infiltrating the brain tissue and affecting many areas, including the area of previous biopsy, left thalamus, whole corpus callosum and both gyri cinguli as well as the left occipital, right parietal and both temporal lobes. In the splenium of the corpus callosum, there was microscopic tumor growth of glioblastoma, consistent with cerebral gliomatosis type 2 (Figure 1B-E).

TREATMENT

The patient underwent a stereotactic biopsy for histological verification of the changes in the right periventricular region. The modified Riechert Stereotactic System (MHT, Freiburg, Germany) and a workstation for multi-planar trajectory planning (Amira, Visage Imaging; Berlin, Germany) were used. The biopsy samples were obtained stepwise along the trajectory through the entire lesion - serial biopsy specimens. The cytopathologist in the operating room immediately evaluated the alternate tissue samples using a smear preparation with methylene blue staining, and reported possible gliomatosis. The tissue fragments for microbiological investigations were immediately transferred from the biopsy forceps into culture medium (BacT/ALERT FA; Biomerieux Durham, United Kingdom) and sent to the microbiological laboratory. The identification was performed with VITEK 2 (Bio Mereus; Craponne, France). Sequencing of the amplified 16S rRNA gene confirmed the identification. The amplification was performed using primers and conditions described by Bianciotto et al[9] and sequencing was carried out by MWG BIOTECH (Ebersberg, Germany). The sequence showed 99% identity to Moraxella osloensis in the NCBI database (NCBI/BLAST: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and 98.6% identity to Moraxella osloensis in the curated database Ribosomal Database Project (http:// rdp.cme.msu.edu/seqmatch/seqmatch_intro.jsp) (Table 1). Similar identity scores were also obtained for Enhydrobacter aerosaccus. Due to reported errors in Enhydrobacter sequences, a low number of Enhydrobacter hits as compared to Moraxella hits and phenotypic identification results, the final reported identification of this strain was Moraxella osloensis. The bacterial strain is still available in the archive of the microbiological laboratory. The remaining tissue fragments were fixed in formaldehyde and sent to the pathology laboratory for analysis. A post-biopsy CT scan was performed to exclude complications and to verify accurate target sampling.

Table 1.

An overview of closest matches of patient isolates 16S rDNA with sequences in two databases (GenBank and Ribosomal Database Project)

| Identification |

GenBank

|

RDP

|

||

|

GenBank numbers

|

% of identity

|

RDP numbers

|

% of identity

|

|

| Moraxella osloensis | AB643592.1 | 99% | S000386983, S000425263, S002227306, S003316307 | 98.6% |

| Moraxella species | AB905490.1, KC119125.1 | 99% | S003750534, S004078352 | 98.6% |

| Enhydrobacter species | FR823402.1 | 99% | S002223560, S002408247 | 98.6% |

RDP: Ribosomal Database Project.

The patient’s clinical condition was unchanged during hospitalization. After a week, she was transferred to the neurological clinic.

The histological analysis of samples obtained by serial stereotactic biopsy failed to provide a definitive diagnosis (Figure 1F). The pathologist found gliomatosis, intermingled with some neoplastic astrocytes. Three weeks later, we received the microbiological test results of the brain tissue samples, which detected Moraxella osloensis. An antimicrobial susceptibility test performed using the disk diffusion method showed that the isolate was susceptible to a variety of antimicrobial agents such as ampicillin, cefaclor, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, imipenem, azithromycin and rifampicin.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Unfortunately, the patient was in poor clinical condition after the stereotactic biopsy due to continuous neurological deterioration. She received palliative medical care in the neurological department and six weeks after the biopsy she died.

DISCUSSION

A specific histological diagnosis is crucial in order to select the best therapeutic option. In this case report, we presented a patient with a progressive frontal lobe syndrome. After extensive diagnostic evaluation, multiple lesions detected by MRI remained the only discernible evidence of her illness. The differential diagnosis based on CT and MRI findings included, among others, gliomatosis cerebri, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and lymphoma. Surprisingly, microbiological analysis of the brain samples revealed infection with Moraxella osloensis, which was completely unexpected. The samples were obtained under sterile conditions during the stereotactic biopsy and it was very unlikely that the samples were contaminated during the course of sampling and analysis. The infection with Moraxella osloensis was probably clinically silent at first in our patient, due to the low virulence of this organism or perhaps due to the antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infection. It was unclear where the organism had spread from. The incidence of surgical site infection at our hospital is lower than reported in many comparable studies[10].

The post-mortem neuropathological examination revealed cerebral gliomatosis affecting various areas of both cerebral hemispheres and the corpus callosum. We suppose that the patient suffered a latent brain infection with Moraxella osloensis, which could have had a possible oncogenic effect on the development of cerebral gliomatosis, or more likely, unfavorably altered the course of the disease. Different microorganisms have long been suspected to play a role in development of brain tumors[10-12]. Another possibility could be that a latent bacterial infection may have modulated the immune responses in the brain tumor defense[12,13]. However, some chronic bacterial infections are thought to be associated with amyloid depositions in Alzheimer’s disease, as well[13]. A PubMed search yielded some published cases of Moraxella osloensis meningitis[3,5]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of brain tissue infection with this microorganism. Bacteria may initiate a cascade of events, leading to chronic inflammation and amyloid deposition or even participate in tumorigenesis. An early diagnosis of encephalitis is critical for effective treatment. In addition to histological analysis, we suggest performing microbiological analysis more often during stereotactic biopsy for multiple brain lesions. However, we are aware that the association between bacterial infection and gliomatosis cerebri could be purely coincidental. In order to rule out a possible causal relationship between microbial infection and cerebral gliomatosis, further studies are needed.

CONCLUSION

This is the first report of a brain tissue infection with Moraxella osloensis, which may initiate a cascade of events, leading to chronic inflammation, amyloid deposition or even tumorigenesis. Early diagnosis of encephalitis is vital for effective treatment. In addition to histological examination, microbiological analysis of stereotactic biopsy samples is imperative.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: The patient provided informed consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 31, 2020

First decision: September 24, 2020

Article in press: November 4, 2020

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Slovenia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Vyshka G S-Editor: Chen XF L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Tadej Strojnik, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Centre Maribor, Maribor SI-2000, Slovenia; Faculty of Medicine, University of Maribor, Maribor SI-2000, Slovenia.

Rajko Kavalar, Department of Pathology, University Medical Centre Maribor, Maribor SI-2000, Slovenia.

Kristina Gornik-Kramberger, Department of Pathology, University Medical Centre Maribor, Maribor SI-2000, Slovenia.

Maja Rupnik, Faculty of Medicine, University of Maribor, Maribor SI-2000, Slovenia; National Laboratory for Health, Environment and Food, Maribor SI-2000, Slovenia.

Slavica Lorencic Robnik, National Laboratory for Health, Environment and Food, Maribor SI-2000, Slovenia.

Mara Popovic, Institute of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana 1000, Slovenia.

Tomaz Velnar, Department of Neurosurgery, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Ljubljana 1000, Slovenia. tvelnar@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Leksell LA. A stereotaxic apparatus for intracerebral surgery. Acta Chir Scand. 1949;99:229–333. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiegel EA, Wycis HT, Marks M, Lee AJ. Stereotaxic Apparatus for Operations on the Human Brain. Science. 1947;106:349–350. doi: 10.1126/science.106.2754.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah SS, Ruth A, Coffin SE. Infection due to Moraxella osloensis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:179–181. doi: 10.1086/313595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan L, Grewal PS. Pathogenicity of Moraxella osloensis, a bacterium associated with the nematode Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita, to the slug Deroceras reticulatum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5010–5016. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.5010-5016.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berrocal AM, Scott IU, Miller D, Flynn HW Jr. Endophthalmitis caused by Moraxella osloensis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:329–330. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0449-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagnard JC, Hidri N, Grillon A, Jesel L, Denes E. Moraxella osloensis, an emerging pathogen of endocarditis in immunocompromised patients? Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14185. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugarman B, Clarridge J. Osteomyelitis caused by Moraxella osloensis. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1148–1149. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1148-1149.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vuori-Holopainen E, Salo E, Saxen H, Vaara M, Tarkka E, Peltola H. Clinical "pneumococcal pneumonia" due to Moraxella osloensis: case report and a review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:625–627. doi: 10.1080/00365540110026737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianciotto V, Lumini E, Bonfante P, Vandamme P. 'Candidatus glomeribacter gigasporarum' gen. nov., sp. nov., an endosymbiont of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:121–124. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taskovska D, Flis V. Incidence of surgical site infections in a tertiary hospital in Slovenia. Acta Medico-Biotechnica. 2015;8:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alibek K, Kakpenova A, Baiken Y. Role of infectious agents in the carcinogenesis of brain and head and neck cancers. Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sowers JL, Johnson KM, Conrad C, Patterson JT, Sowers LC. The role of inflammation in brain cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;816:75–105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miklossy J. Chronic inflammation and amyloidogenesis in Alzheimer's disease -- role of Spirochetes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;13:381–391. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-13404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]