Abstract

BACKGROUND

Total pancreatectomy (TP) is usually considered a therapeutic option for pancreatic cancer in which Whipple surgery and distal pancreatectomy are undesirable, but brittle diabetes and poor quality of life (QoL) remain major concerns. A subset of patients who underwent TP even died due to severe hypoglycemia. For pancreatic cancer involving the pancreatic head and proximal body but without invasion to the pancreatic tail, we performed partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy (PPTP-SP) in selected patients, in order to improve postoperative glycemic control and QoL without compromising oncological outcomes.

AIM

To evaluate the efficacy of PPTP-SP for patients with pancreatic cancer.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed 56 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma who underwent PPTP-SP (n = 18) or TP (n = 38) at our institution from May 2014 to January 2019. Clinical outcomes were compared between the two groups, with an emphasis on oncological outcomes, postoperative glycemic control, and QoL. QoL was evaluated using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC PAN26). All patients were followed until May 2019 or until death.

RESULTS

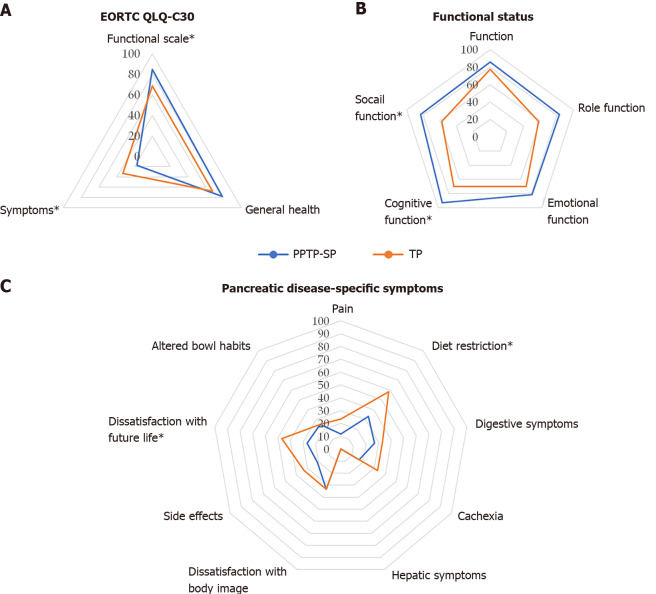

A total of 56 consecutive patients were enrolled in this study. Perioperative outcomes, recurrence-free survival, and overall survival were comparable between the two groups. No patients in the PPTP-SP group developed cancer recurrence in the pancreatic tail stump or splenic hilum, or a clinical pancreatic fistula. Patients who underwent PPTP-SP had significantly better glycemic control, based on their higher rate of insulin-independence (P = 0.014), lower hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level (P = 0.046), lower daily insulin dosage (P < 0.001), and less frequent hypoglycemic episodes (P < 0.001). Global health was similar in the two groups, but patients who underwent PPTP-SP had better functional status (P = 0.036), milder symptoms (P = 0.013), less severe diet restriction (P = 0.011), and higher confidence regarding future life (P = 0.035).

CONCLUSION

For pancreatic cancer involving the pancreatic head and proximal body, PPTP-SP achieves perioperative and oncological outcomes comparable to TP in selected patients while significantly improving long-term glycemic control and QoL.

Keywords: Partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy, Total pancreatectomy, Pancreatic cancer, Treatment outcome, Diabetes mellitus, Quality of life

Core Tip: In order to improve postoperative glycemic control and quality of life (QoL) while ensuring safety and oncological efficacy, we performed partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy (PPTP-SP) as an alternative to total pancreatectomy in selected patients. No patients in the PPTP-SP group developed cancer recurrence in the pancreatic tail stump or splenic hilum, or a clinical pancreatic fistula. Although the exocrine function of the remnant pancreas almost completely degenerated, its endocrine function was preserved. Our long-term follow-up indicated that PPTP-SP achieved significantly better postoperative glycemic control and QoL without compromising oncological outcomes. Moreover, PPTP-SP could also be indicated for other pancreatic neoplasms.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, pancreatic cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer deaths[1], and its incidence and mortality rates have also increased notably in China in recent years[2]. Surgical resection is currently the only method that is potentially curative, and total pancreatectomy (TP) is one of the three main surgical techniques used to treat pancreatic cancer. However, several studies in the late 20th century suggested that TP was associated with high operative morbidity, intractable long-term complications, and poor oncological outcomes[3-6]. Notably, the oncological outcomes after TP have been improved remarkably in recent years attributed to the development of surgical techniques and the advances in adjuvant therapies. The median survival time (17.9 to 21.9 mo) and 5-year survival rate (13% to 20%) of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) after TP are similar to those achieved by Whipple surgery or distal pancreatectomy[7-9]. However, postoperative glycemic disorder and poor quality of life (QoL) after TP remain significant challenges[10,11].

Previous studies indicated that 13% to 32% of patients who underwent TP were readmitted to hospitals because of glycemic disorders[10,12,13]. Many TP patients experienced symptomatic hypoglycemia, with hypoglycemic episodes occurring about two times per week[12,13], and causing several serious complications[10]. Moreover, chronic diabetes-specific complications, such as cardiovascular diseases, peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy, may also occur due to the increased survival time after TP[14,15]. On the other hand, although a few studies concluded that QoL after TP is acceptable, these results could be explained by the choice of the control group used in comparisons[12]. Müller et al[7] used a case-matched comparison and demonstrated that TP caused greater impairments to QoL than the Whipple procedure, especially in functional status.

The distal pancreas plays an important role in maintaining carbohydrate metabolism. It has been proven that the endocrine function of the distal pancreas can be preserved even when the atrophy and disappearance of the acini were evident[16,17]. More importantly, several recent studies demonstrated that lymph node (LN) metastasis at the splenic hilum (station 10) is rare in pancreatic body cancer[18,19], and splenic preservation using the Warshaw method can be technically feasible and oncologically reliable in the treatment of pancreatic body cancer in selected patients[20,21]. Thus, for pancreatic cancer involving the pancreatic head and proximal body, but without invasion to the pancreatic tail and splenic hilum, we performed partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy (PPTP-SP) with R0 margins as an alternative to TP in selected patients. Then, we compared the postoperative outcomes of patients who underwent PPTP-SP or TP, with an emphasis on oncological outcomes, postoperative glycemic control, and QoL. The aim of this study was to report the long-term efficacy of PPTP-SP for pancreatic cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study patients

This study was conducted at Huashan Hospital, affiliated to Fudan University (Shanghai, China), and was approved by Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital. All patients provided written informed consent. The study included patients who underwent PPTP-SP or TP for resectable PDAC from May 2014 to January 2019, and were followed until May 2019. All of the procedures were performed by the same team of surgeons. Patients were excluded if they underwent a second resection due to cancer recurrence in the remnant pancreas or the development of a Grade C pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Indications for PPTP-SP

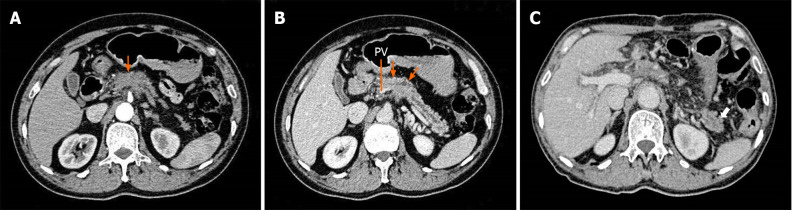

PPTP-SP was indicated for patients selected from those formerly considered as candidates for TP. Preoperative radiological examinations, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), were used to preliminarily evaluate the eligibility of patients to undergo PPTP-SP. Intraoperative findings and analysis of frozen-section pathology specimens were used to confirm whether the pancreatic stump could be preserved. PPTP-SP was performed only when all of the following criteria were met (Table 1): (1) Pancreatic cancer involved the pancreatic head and proximal body (Figure 1); (2) Neither the celiac axis nor the left gastric artery was invaded by cancer; (3) The distance between the carcinoma’s lateral margin and the splenic hilum was more than 6 cm; (4) PET-CT images indicated no high metabolic regions in the pancreatic tail or splenic hilum; and (5) R0 resection was verified by analysis of the intraoperative frozen section. Furthermore, the decision of PPTP-SP was changed to TP if: (1) The pancreatic carcinoma was concomitant with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN); (2) The pancreatic cancer was multifocal; or (3) Intraoperative findings indicated enlarged LNs in the pancreatic tail and/or splenic hilum.

Table 1.

Indications for partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy

| Criteria | PPTP-SP | TP |

| Inclusive criteria (all must be fulfilled) | ||

| Tumor involving both Ph and left pancreas | Necessary | Necessary |

| No LGA involvement | Necessary | Unnecessary |

| Tumor’s lateral margin more than 6 cm away from Sh | Necessary | Unnecessary |

| No high metabolic regions in Pt or Sh on PET-CT | Necessary | Unnecessary |

| Pt margin is negative | Necessary | Unnecessary |

| Exclusive criteria (if any) | ||

| Multifocal cancer | ||

| Concomitant with IPMN | Unrecommended | Recommended |

| Multifocal PDAC | Unrecommended | Recommended |

| Enlarged LNs in Pt and/or Sh | Unrecommended | Recommended |

Ph: Pancreatic head; LGA: Left gastric artery; Pt: Pancreatic tail; Sh: Splenic hilum; IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms; PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Figure 1.

Preoperative and postoperative computed tomography images of a 65-year-old male patient who underwent partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The pancreatic cancer involved the pancreatic head and proximal body, which led to the dilatation of the distal pancreatic duct. The length of the preserved pancreatic stump was 31 mm, and the patient was still insulin-independent at the last follow-up. A and B: Preoperative; C: Postoperative. PV: Portal vein.

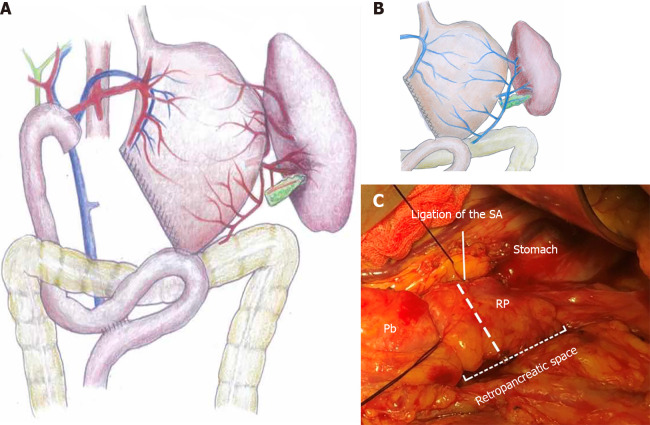

Surgical technique for PPTP-SP

Figure 2A and B provides a diagrammatic illustration of the surgery. The pancreatic head was mobilized after an extended kocherization of the duodenum. The gastrocolic ligament was divided near the transverse colon to expose the pancreas, while the gastrosplenic ligament was retained intact. Following the incision of the peritoneum along the inferior and superior borders of the pancreas, the superior mesenteric vessels and the splenic artery (SA) were exposed. The SA was ligated at the upper margin of the pancreatic tail, ensuring the integrity of the left gastropeiploic artery, the short gastric arteries, and the network of collateral arteries near the splenic hilum (Figure 2C). A tunnel was created behind the pancreatic tail, and the pancreas was transected at 2 to 3 cm proximal to the end of its tail with an Endo GIA stapler or a scalpel. The proximal resection margin was sent for intraoperative pathological examination, and if it was tumor-positive, then a TP needed to be performed. The left pancreas was separated from the retroperitonuem in a distal-to-proximal direction. The SA was ligated and divided close to its origin, and it would be removed with the specimen later. The stomach was transected using a linear stapler while ensuring the integrity of the left gastric vessels and the left gastroepiploic vessels. Retraction of the distal pancreas to the patient’s right was performed to expose the superior mesenteric-splenic-portal vein confluence. The uncinate process was carefully dissected from the superior mesenteric artery and vein. Finally, the splenic perfusion was inspected, and two prophylactic peritoneal drains were placed down to the superior and inferior margins of the pancreatic stump.

Figure 2.

Diagrams and intraoperative image showing the surgical technique. A and B: Care was taken to ensure the integrity of the left gastroepiploic vessels, the short gastric vessels, and the network of collateral vessels near the splenic hilum. The left gastric vein was preserved as much as possible (B); C: A tunnel was created behind the pancreatic tail, and the pancreas could be transected along the bold dashed line. SA: Splenic artery; Pb: Pancreatic body; RP: Remnant pancreas.

Postoperative management and follow-up

When patients who underwent PPTP-SP or TP were started on a liquid diet, oral pancreatic enzyme substitutes were administered to treat exocrine dysfunction, whereas the therapy for endocrine dysfunction was more complex. After surgery, an insulin pump was used for continuous subcutaneous insulin injection (CSII). The target range of postoperative fasting blood glucose (FBG) was 6 to 10 mmol/L. If symptomatic hypoglycemia was present or if the FBG was below 3.9 mmol/L, insulin infusion was suspended and a glucose solution was administered. Once the liquid diet was initiated, the CSII was gradually replaced by multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin. After consulting with endocrinologists, every patient was provided with a customized glycemic control program upon discharge.

All patients who underwent PPTP-SP or TP for PDAC were recommended to receive adjuvant chemotherapy (gemcitabin + 5-fluororacil + oxaliplatin or S1 + gemcitabin) for at least six cycles and were followed in the outpatient department and/or by telephone. Diagnosis of recurrence was based on the comprehensive evaluation of tumor markers and radiological examinations [CT, MRI, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and/or PET-CT]. Survival information and QoL were obtained from the patients or their family members. We used the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ C30 and EORTC QLQ PAN26) to evaluate the QOL after surgery, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to assess the psychological stress of the patients’ intimate family members. All living patients without cancer recurrence were enrolled in the QoL survey.

Definition of variables

The assessment of resectability was carried out according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. Pathological data, including pathological diagnosis, tumor’s greatest dimension, involvement of major visceral arteries (the celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery, and/or common hepatic artery), regional lymph nodal metastasis, and distant metastasis, were collected according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging of Pancreatic Cancer (8th ed., 2017)[22]. R0 resection in our institution was defined as the absence of tumor cells within 1 mm from the operative margin (‘R0-wide resection’)[23]. Pancreatic fistula and other complications after pancreatectomy were defined or graded according to criteria of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS)[24-27]. Resection of the portal/superior mesenteric vein was classified using the ISGPS consensus statement[28]. Mortality rate was defined as the number of patients who died within 30 d after operation, and readmission as admission within 30 d after discharge[20].

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and are expressed as the mean ± SD or medians with 25th and 75th percentiles. All categorical variables were compared using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to determine the significance of differences between groups. A P value below 0.05 was considered significant. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS-20, release 2.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, United States) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Demographic and baseline characteristics

We included 56 consecutive patients who underwent PPTP-SP (n = 18) or TP (n = 38) for PDAC. The two groups had no significant differences in age, gender, body mass index (BMI), presenting symptoms, major preoperative comorbidities, tobacco or alcohol use, or American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores (Table 2). The two groups were also similar in tumor markers, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, preoperative nutritional status, and preoperative glycemic status.

Table 2.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Parameter | PPTP-SP (n = 18) | TP (n = 38) | P value |

| Male, n (%) | 10 (55.6) | 22 (57.9) | 0.869 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 63.9 ± 7.8 | 62.5 ± 8.9 | 0.565 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 23.7 ± 3.2 | 22.3 ± 3.5 | 0.350 |

| Symptomatic, n (%); Incident, n (%) | 12 (66.7); 6 (33.3) | 29 (76.3); 9 (23.7) | 0.446 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 4 (22.2) | 12 (31.6) | 0.469 |

| Preoperative DM | 3 (16.7) | 11 (28.9) | 0.322 |

| Heart diseases | 3 (16.7) | 4 (10.5) | 0.525 |

| COPD | 1 (5.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.582 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | 0.173 | ||

| Pancreatic head | 6 (33.3) | 9 (23.7) | |

| Pancreatic body and tail | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.5) | |

| Whole pancreas | 12 (67.7) | 25 (69.4) | |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | 6 (33.3) | 11 (28.9) | 0.739 |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 7 (38.9) | 17 (44.7) | 0.680 |

| CA19-9 ≥ 37 U/mL, n (%) | 15 (83.3) | 31 (81.6) | 0.872 |

| CA125 ≥ 35 U/mL, n (%) | 4 (22.2) | 9 (23.6) | 0.904 |

| CEA ≥ 10 μg/L, n (%) | 2 (11.1) | 7 (18.4) | 0.475 |

| Preoperative biliary drainage, n (%) | 3 (16.7) | 8 (21.1) | 0.700 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy, n (%) | 5 (27.8) | 9 (23.7) | 0.741 |

| ASA score (II-III), n (%) | 10 (55.6) | 26 (68.4) | 0.348 |

| Preoperative ALB (g/L), median (IQR) | 42.0 (39.5-45.5) | 40.5 (39.0-43.5) | 0.201 |

| Preoperative fasting C-peptide (μg/L), mean ± SD | 1.39 ± 0.55 | 1.14 ± 0.97 | 0.265 |

| Preoperative fasting insulin (mU/L), mean ± SD | 8.80 ± 3.75 | 7.13 ± 3.58 | 0.422 |

| Preoperative fasting blood sugar (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 5.9 (4.9-6.7) | 6.3 (4.2-7.1) | 0.207 |

In the partial pancreatic tail preserving-subtotal pancreatectomy (PPTP-SP) group, ‘location in whole pancreas’ means that the tumor is locating in both the pancreatic head and proximal body. PPTP-SP: Partial pancreatic tail preserving-subtotal pancreatectomy; TP: Total pancreatectomy; BMI: Body mass index; DM: Diabetes mellitus; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; ALB: Albumin; SD: Standard deviation; IQR: Interquartile range.

Perioperative and pathological outcomes

The PPTP-SP group had a somewhat shorter operative time and blood loss, due to the omission of splenectomy (Table 3). The two groups were similar in terms of tumor size, node metastasis, vascular or neural invasion, and rate of advanced-stage disease. We performed the resection of the portal vein/superior mesenteric vein in 32 patients, 11 (61.1%) in the PPTP-SP group and 21 (55.3%) in the TP group; and type IV resection (segmental resection with an interposition venous graft) in 31 patients, 11 (61.1%) in the PPTP-SP group while 20 (52.6%) in the TP group. The overall morbidity rate was 38.9% after PPTP-SP and 34.2% after TP. All complications were successfully treated, and no patient required postoperative surgical intervention. Moreover, none of the patients in the PPTP-SP group developed a clinical pancreatic fistula or gastric bleeding. The postoperative hospital stay was somewhat longer in those who underwent TP (9.5 vs 11.5 d, P = 0.286). One patient in the PPTP-SP group was readmitted due to chyle leakage, and three patients in the TP group were readmitted, with one due to intra-abdominal fluid accumulation and the others due to severe glycemic disorder. Four patients in the TP group were confirmed to have PDAC concomitant with IPMN according to final pathology. No significant differences in the tumor differentiation, the number of LNs harvested, the frequency of LN metastasis, or the R0 rate were observed between the two groups. In addition, the rates of vascular invasion and perineural invasion, tumor size, and TNM stages were similar between the two groups.

Table 3.

Perioperative and pathological outcomes

| Parameter | PPTP-SP (n = 18) | TP (n = 38) | P value |

| Perioperative outcomes | |||

| Operative time (h), median (IQR) | 6.7 (6.6-8.2) | 7.3 (6.8-8.6) | 0.076 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL), median (IQR) | 550 (400-800) | 600 (500-1200) | 0.386 |

| Red cells transfusion (mL), median (IQR) | 200 (200-600) | 400 (200-1000) | 0.249 |

| Resection of PV/SMV, n (%) | 11 (61.1) | 21 (55.3) | 0.680 |

| Overall morbidity, n (%) | 7 (38.9) | 13 (34.2) | 0.733 |

| Major complications, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (7.9) | 0.751 |

| Delayed gastric emptying, n (%) | 2 (11.1) | 4 (10.5) | 0.947 |

| Pulmonary disease, n (%) | 3 (16.7) | 4 (10.5) | 0.516 |

| Chyle leakage, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (7.9) | 0.751 |

| Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 2 (5.3) | 0.964 |

| Abdominal collection, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (2.6) | 0.582 |

| Arrhythmia, n (%) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (7.9) | 0.693 |

| Biliary leakage, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Biochemical leak, n (%) | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.099 |

| Grade B or C pancreatic fistula, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Morality, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Readmission, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 3 (7.9) | 0.751 |

| Postoperative staying (d), median (IQR) | 9.5 (7-16) | 11.5 (9-17.5) | 0.286 |

| Pathological outcomes | |||

| Histology, n (%) | 0.153 | ||

| PDAC without IPMN | 18 (100.0) | 34 (89.5) | |

| PDAC concomitant with IPMN | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.5) | |

| Differentiation, n (%) | 0.829 | ||

| High | 1 (5.6) 1 (5.6) | 3 (7.9) | |

| Moderate | 11 (61.1) | 20 (52.6) | |

| Poor | 6 (33.3) | 15 (39.5) | |

| Harvested lymph nodes (n), median (IQR) | 12.5 (9-16) | 14.5 (10-20) | 0.521 |

| Lymph node metastasis, n (%) | 9 (50.0) | 25 (65.8) | 0.259 |

| Paraaortic lymph node metastasis (#16), n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 7 (18.4) | 0.199 |

| Resection Margin, n (%) | 0.487 | ||

| R0 | 18 (100.0) | 37 (97.4) | |

| R1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Vascular invasion (SMV/PV), n (%) | 9 (50.0) | 17 (44.7) | 0.712 |

| Perineural invasion, n (%) | 13 (72.2) | 20 (52.6) | 0.164 |

| Colonic invasion, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | 0.487 |

| Tumor size (cm), median (IQR) | 4.3 (3.0-5.1) | 4.4 (3.4-6.6) | 0.408 |

| T stage | 0.445 | ||

| T1 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.3) | |

| T2 | 8 (44.4) | 13 (34.2) | |

| T3 | 10 (55.6) | 22 (57.9) | |

| T4 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.6) | |

| N stage | 0.502 | ||

| N0 | 9 (50.0) | 13 (34.2) | |

| N1 | 7 (38.9) | 18 (47.4) | |

| N2 | 2 (11.1) | 7 (18.4) | |

| AJCC 8th stage | 0.657 | ||

| IA-IB | 4 (22.2) | 7 (18.4) | |

| IIA-IIB | 12 (66.7) | 23 (60.5) | |

| III | 2 (11.1) | 8 (21.1) | |

| IV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

PPTP-SP: Partial pancreatic tail preserving-subtotal pancreatectomy; TP: Total pancreatectomy; PV/SMV: Portal vein and/or superior mesenteric vein; PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer; IQR: Interquartile range.

Long-term survival

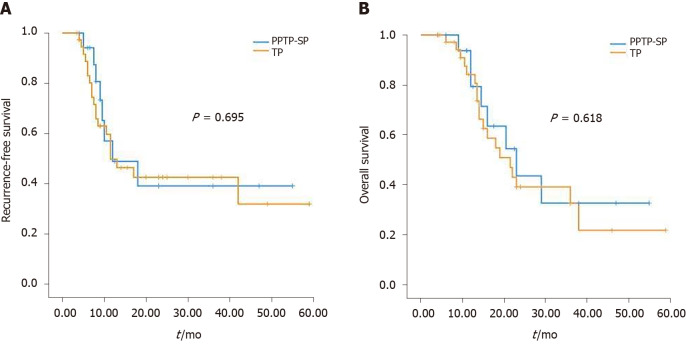

The analysis of outcomes (Figure 3) indicated the two groups had similar median RFS times (PPTP-SP: 12 mo; TP: 11.5 mo), median OS times (PPTP-SP: 23 mo; TP: 21.5 mo), 1- and 3-year RFS rates (PPTP-SP: 53.8% and 25.0%; TP: 53.1% and 20.8%), and 1- and 3-year OS rates (PPTP-SP: 85.7% and 27.3%; TP: 82.1% and 26.1%). All patients in the PPTP-SP group received adjuvant chemotherapy, and the proportion was 84.2% in the TP group. After a median follow-up period of 16 mo (range: 3.5 to 59), eight (44.4%) patients in the PPTP-SP group and 20 (52.6%) in the TP group had confirmed tumor recurrence. Their primary site of recurrence included the liver (4 vs 11 , P = 0.596), peritoneum (2 vs 5, P = 0.365), local recurrence (1 vs 3, P = 0.545), and lung (1 vs 1 , P = 0.544), with no significant differences between the two groups. As of the last follow-up, none of the patients in the PPTP-SP group experienced recurrence in the pancreatic tail stump or splenic hilum.

Figure 3.

Comparison of recurrence-free survival and overall survival between patients who underwent partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy or total pancreatectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. A: Recurrence-free survival; B: Overall survival. RFS: Recurrence-free survival; OS: Overall survival.

Long-term glycemic control and body weight change

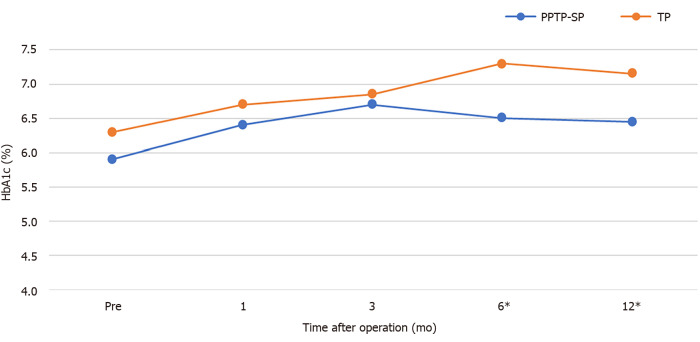

The two groups (PPTP-SP vs TP) had similar mean daily dosages of oral pancreatic enzyme substitutes (10.3 capsules vs 9.8 capsules, P = 0.662), mean weight loss (from pre-operation to the last follow-up, 8.1 kg vs 9.1 kg, P = 0.433), and mean BMI at the last follow-up (19.9 kg/m2 vs 19.2 kg/m2, P = 0.460). The analysis of long-term outcomes (Table 4) indicated that four of 18 patients in the PPTP-SP group were insulin-independent as of the last follow-up. The median frequency of postoperative hypoglycemic episodes was 0 per week after PPTP-SP and 1.25 per week after TP. The requirement for postoperative exogenous insulin was also significantly less after PPTP-SP than after TP (10 U vs 32 U, P < 0.001). The mean fasting C-peptide level was 0.61 μg/L in PPTP-SP patients, but was below 0.14 μg/L (the detection limit) in TP patients. The median HbA1c levels at the 6th mo (6.5% vs 7.3%, P = 0.012) and the 12th mo (6.45% vs 7.15%, P = 0.046) after operation were significantly lower after PPTP-SP than after TP (Figure 4).

Table 4.

Postoperative glycemic control

| Parameter | PPTP-SP (n = 18) | TP (n = 38) | P value |

| Insulin-dependent DM, n (%) | 14 (72.2) | 38 (100) | 0.014 |

| Frequency of hypoglycemia (n/per week), median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0-0.25) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | < 0.001 |

| Total daily insulin dosage (U), median (IQR) | 10 (6-14) | 32 (28-39) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting C-peptide (μg/L), mean ± SD | 0.61 ± 0.15 | < 0.14 | - |

| Fasting insulin (mU/L), mean ± SD | 6.3 ± 2.4 | 6.0 ± 3.9 | 0.418 |

| Frequency of glucose monitoring (n/per day), median (IQR) | 1.5 (1-2) | 4 (2-4) | < 0.001 |

PPTP-SP: Partial pancreatic tail preserving-subtotal pancreatectomy; TP: Total pancreatectomy; DM: Diabetes mellitus; IQR: Interquartile range; SD: Standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Change of hemoglobin A1c levels after partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy or total pancreatectomy. The asterisk indicates a statistical difference. HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c; PPTP-SP: Partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy; TP: Total pancreatectomy.

Assessment of QoL

A total of ten patients in the PPTP-SP group and 18 patients in the TP group completed the QoL survey, all of whom were recurrence-free at the last follow-up. The two groups had similar ‘global health’ (Figure 5), but the PPTP-SP group scored better on the ‘functional scale’ (84.0 ± 8.5 vs 68.9 ± 19.3, P = 0.036) and presented less severe symptoms (17.2 ± 7.5 vs 33.3 ± 15.8, P = 0.013). The scores for ‘cognitive function’ (93.3 ± 11.7 vs 70.0 ± 21.0, P = 0.024) and ‘social function’ (83.3 ± 22.2 vs 58.3 ± 25.2, P = 0.031) were significantly higher in the PPTP-SP group. Other relative parameters including ‘physical function’, ‘role function’, and ‘emotional function’ were better in the PPTP-SP group, but the differences were not statistically significant. The analysis of pancreatic disease-specific symptoms indicated that the two groups had no significant differences in ‘pain’, ‘digestive symptoms’, ‘hepatic symptoms’, ‘ascites’, ‘side effects’, ‘altered bowl habit’, or ‘cachexia’. However, patients in the PPTP-SP group were less likely to report ‘dissatisfaction with future life’ (26.7 ± 14.5 vs 46.7 ± 23.3, P = 0.035) and ‘diet restriction’ (26.7 ± 20.8 vs 58.3 ± 25.6, P = 0.011). The intimate family members of the two groups reported similar psychological burdens including anxiety (7.9 ± 3.8 vs 8.3 ± 3.6, P = 0.811) and depression (6.2 ± 3.5 vs 6.7 ± 2.8, P = 0.729).

Figure 5.

Patients’ quality of life (QoL) after partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy or TP. A: Quality of life (QoL) evaluated using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30; B: Functional status; C: Pancreatic disease-specific symptoms. Patients who underwent partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy had better functional status, milder symptoms, less severe diet restriction, and stronger confidence regarding future life. The asterisk indicates a statistical difference. EORTC QLQ-C30: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; PPTP-SP: Partial pancreatic tail preserving subtotal pancreatectomy; TP: Total pancreatectomy.

DISCUSSION

TP is usually considered a safe therapeutic option for pancreatic cancers in which partial pancreatectomy is unable to achieve R0 margins, but TP-induced diabetes and poor QoL are still big problems[10,14,29]. Exogenous supplements are still unable to totally replace endocrine pancreatic function[30], thus some modifications in the operative procedures may help to ameliorate TP-induced diabetes and improve long-term QoL. For example, subtotal pancreatectomy with ventral pancreas preservation can be a safe alternative to TP for selected patients[15] because it provides comparable oncological outcomes with superior postoperative glycemic control and QoL[15,31]. This method is currently accepted for treating pancreatic tumors with low malignancy, but not high malignancy. Notably, as the survival time after TP for PDAC has significantly improved, there is greater emphasis on other postoperative outcomes, such as QoL[12,13]. Therefore, we performed PPTP-SP for selected patients with PDAC on the purpose of ameliorating postoperative glycemic disorder and improving QoL, but without compromising oncological outcome.

There is currently a consensus that R0 resection and the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy are the most important independent predictors of prolonged survival[11,32]. The rate of recurrence in the remnant pancreas after radical partial pancreatectomy for PDAC is extremely low (2% for those without IPMN[33]). However, the presence of IPMN can increase the risk of tumor recurrence in the pancreatic remnant by up to 15%[33]. This suggests that PPTP-SP is not suitable when the carcinoma is multifocal or concomitant with mutifocal pancreatic cysts[34]. The extent of lymphadectomy in PPTP-SP is almost the same as classical TP, except that there is no excision of the LNs in station 10. Notably, there is a low rate (4%) of nodal metastasis in the splenic hilum in left-sided pancreatic cancers[19]. As for more proximal (neck/body) pancreatic cancer, there are no positive LNs in this station[18,19]. Thus, splenectomy can be omitted in well-selected patients. Our results also indicated that there was no tumor recurrence in the pancreatic stump or splenic hilum after PPTP-SP during the entire follow-up period. However, further studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are necessitated for more precise evaluation of the oncological outcomes after this procedure. In general, patients who are younger, have positive LNs, or have favorable postoperative recovery are more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy[35,36] as compared to those with poor QoL[9,11]. Moreover, intractable postoperative complications are likely to postpone or suspend adjuvant therapies[36]. Whether better glycemic control and QoL contribute to patients’ acceptance or completion of adjuvant chemotherapy requires further investigation.

Some doctors proposed that islet cells have an even distribution throughout the pancreas, and that exocrine dysfunction can induce degeneration of endocrine function[37]. In fact, glycemic disorder resulting from exocrine pancreatic disease is rare[38], accounting for 0.5% to 1.7% of all cases[39]. A recent study utilizing a three-dimensional (3D) map technique found that the volume and density of islet cells in the pancreatic tail were significantly greater than those in the proximal pancreas[40]. For adults, a partial pancreatectomy does not alter the fractional beta-cell volume in the remnant pancreas[41]. Furthermore, other studies[16,17] demonstrated that ligation of the pancreatic duct caused complete atrophy of the acini and fibrosis of pancreatic stump, but without obvious negative impact on islet cells. Thus, the partial preservation of the pancreatic tail using our method retains a considerable proportion of functional islets, leading to decreased use of insulin and fewer hypoglycemic episodes over the long term. It is not yet possible to completely replace the endocrine pancreatic function due to the intricate interactions among insulin, glucagon, and other endocrine-related hormones[42]. Therefore, our modified surgery could be considered as a feasible and effective method in alleviating type 3c diabetes secondary to TP.

In the 1980s, proximal subtotal pancreatectomy with stapling of the pancreatic remnant was performed for pancreatic head cancer in an effort to avoid postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatico-digestive anastomosis and to prevent total loss of pancreatic endocrine function[5,42-44]. The resection extent was similar to that of pancreaticoduodenectomy, except for removing more pancreatic parenchyma. The median survival time after subtotal pancreatectomy for PDAC is approximately 12 mo[44]. The rate of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) was 14% after retaining 5 cm of the pancreatic tail[5]. There were about 60% of patients who could maintain glucose metabolic balance without pharmacological intervention after this surgery[44]. However, with the advances in surgical techniques, the incidence of POPF after pancreaticojejunostomy has remarkably decreased[45] since the late 1990s. These previous studies can be used as a reference.

PPTP-SP is currently indicated for pancreatic cancer involving the pancreatic head and proximal body in selected patients. In our department, proximal body is defined as the proximal proportion of the pancreatic body with its left boundary more than 6 cm away from the splenic hilum. Warshaw’s technique (WT) is recommended for these cases because dissection of splenic vessels out of the pancreatic body may wreck the integrity of the margins around the cancer[46]. Pancreatic branches originating from the distal SA and/or inferior branch of SA could provide the arterial supply to the pancreatic stump[47]. Left gastroepiploic and short gastric veins are crucial to venous return of the spleen and pancreatic remnant. The collateral veins between the gastroepiploic veins and the left colonic vein also play a role to alleviate gastric venous congestion. Yang et al[20] found that the preservation of the spleen using the Warshaw operation leads to a 12.5% incidence of perigastric varices, however, combining with distal pancreatectomy could dramatically decrease the risk of gastric bleeding. The length of the retained pancreatic remnant ranged from 21 to 33 mm (median: 25 mm), which made pancreatico-digestive anatomosis technically difficult and practically unworthy. Overall, none of the patients developed a postoperative Grade B or Grade C POPF, and only two (11.1%) patients developed a biochemical leak. Soft pancreatic tissue are known risk factors for POPF[45,48,49]. For patients in the PPTP-SP group, the obstruction of the pancreatic duct by carcinoma caused fibrosis of the remnant pancreas, and degeneration of exocrine function. Moreover, the small volume of the pancreatic remnant retained leads to a low risk for pancreatic fistula[5]. Therefore, the outcomes of our study were not surprising. However, if the texture of the pancreatic remnant is normal (nonfibrotic), it is unknown whether PPTP-SP is feasible[48], and pancreaticoduodenectomy with SA resection (PD-SAR) can be considered as a therapeutic option[50]. Meanwhile, the relationship between the pancreatic stump volume and its endocrine function needs to be further evaluated. Hopefully, new methods for the preoperative assessment of pancreatic fibrosis[49] and the postoperative evaluation of the pancreatic remnant’s volume[50] could be available soon.

QoL is now considered as important as morbidity and mortality when assessing prognosis after pancreatectomy, and severe impairments and the complete absence of pancreatic function directly lead to poor QoL[3,7]. Patients who underwent TP had significantly poorer ‘function status’ and more severe symptoms compared with those who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy, even though their ‘global health’ scores were similar[7,14]. Several studies showed that partial preservation of pancreaitc exocrine function contributed to alleviation of cachexia, an improvement of bowel habits, and amelioration of some other pancreatic disease-specific symptoms[51,52], while partial preservation of pancreatic endocrine function can evidently improve ‘function status’ and reduce postoperative discomfort[7,14,15]. In our patients, the preserved pancreatic tail stumps did not contribute to the exocrine function and hence, the two groups had similar scores in most pancreatic disease-specific parameters. However, the patients in the PPTP-SP group showed fewer hypoglycemic episodes, fewer daily insulin supplements, and improved glycemic status, which contributed to the better QoL. These results were in consistent with the findings of Sutherland et al[29]. In the near future, patients undergoing PPTP-SP or TP will probably have more satisfactory QoL with the aid of a more effective pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy[53]. In addition, the extent of anxiety and depression in these patients’ intimidate family members was unaffected by the type of surgical procedure performed, perhaps because fear of the pancreatic cancer itself was the greatest source of their anxiety and depression.

There are a few limitations in this study. First of all, it was a retrospective analysis. Further research, ideally prospective randomized studies, should be performed to verify our conclusions. Second, our sample size was relatively small and all patients were from a single institution. Hence, future multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are needed to establish the generalizability of our findings.

CONCLUSION

For treating pancreatic cancer, our results indicated that PPTP-SP achieved perioperative and oncological outcomes comparable to those of TP in selected patients, but provided significantly better long-term glycemic control and more satisfactory QoL. None of the patients who underwent PPTP-SP developed cancer recurrence in the remnant pancreas or splenic hilum and none of them had a clinical pancreatic fistula or gastric bleeding as of the last follow-up. However, in future, multicenter and prospective studies with larger sample size are required to determine the long-term potential risks and benefits of this procedure.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Total pancreatectomy (TP) is usually considered a therapeutic option for pancreatic cancers in which neither Whipple surgery nor distal pancreatectomy could achieve R0 resection. Although the morbidity and mortality after TP have decreased continuously, the postoperative glycemic disorder and poor quality of life (QoL) are still big problems. The brittle diabetes following TP may expose patients to life-threatening complications, and those with poor QoL are less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

Research motivation

Several methods were invented for alleviating the brittle diabetes following TP, but some of them are expensive, time-consuming, or ineffective. We wanted to develop an easy and effective method to prevent or minimize this intractable complication using surgical techniques.

Research objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of partial pancreatic tail preserving- subtotal pancreatectomy (PPTP-SP) for patients with pancreatic cancer.

Research methods

Fifty-six consecutive patients who underwent TP or PPTP-SP for pancreatic cancer were enrolled in this retrospective study. The indications and surgical procedures have been elaborated in the article. Clinical outcomes were compared between the two groups (PPTP-SP vs TP), with an emphasis on oncological outcomes, postoperative glycemic control, and QoL.

Research results

PPTP-SP is indicated for patients selected from those usually considered as candidates for TP, and it is technically easy for skillful pancreatic surgeons. The perioperative outcomes were comparable between the two groups, as well as the long-term survival. Currently, no patients who underwent PPTP-SP developed cancer recurrence in the pancreatic tail stump or splenic hilum, or a clinical pancreatic fistula. Furthermore, those in the PPTP-SP group showed an evident glycemic advantage over those in the TP group, thus having better functional status, milder symptoms, less severe diet restriction, and higher confidence regarding future life.

Research conclusions

For treating pancreatic cancer, PPTP-SP could achieve perioperative and oncological outcomes comparable to those of TP in selected patients while providing significantly better long-term glycemic control and more satisfactory QoL.

Research perspectives

We hope that our study could give pancreatic surgeons throughout the world another option when treating pancreatic tumor in selected patients. Meanwhile, further research, ideally prospective randomized studies, with larger sample size and longer follow-up is needed to establish the generality of our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Yang F and Dr. Shi HJ for their contribution to manuscript revision, Yan D and Lee E for further linguistic revision, and Zhang L for diagram drawing.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University (Approval No. KY 2019-566).

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We declare that we have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: June 30, 2020

First decision: September 18, 2020

Article in press: November 11, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shah OJ, Smith RC S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li X

Contributor Information

Li You, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Shanghai 200040, China.

Lie Yao, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Shanghai 200040, China.

Yi-Shen Mao, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Shanghai 200040, China.

Cai-Feng Zou, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Shanghai 200040, China.

Chen Jin, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200040, China.

De-Liang Fu, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Pancreatic Disease Institute, Huashan Hospital, Shanghai 200040, China. surgeonfu@163.com.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin . 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin QJ, Yang F, Jin C, Fu DL. Current status and progress of pancreatic cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol . 2015;21:7988–8003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Chiaro M, Rangelova E, Segersvärd R, Arnelo U. Are there still indications for total pancreatectomy? Updates Surg . 2016;68:257–263. doi: 10.1007/s13304-016-0388-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks JR, Brooks DC, Levine JD. Total pancreatectomy for ductal cell carcinoma of the pancreas. An update. Ann Surg . 1989;209:405–410. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198904000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ihse I, Anderson H, Andrén-Sandberg Total pancreatectomy for cancer of the pancreas: is it appropriate? World J Surg . 1996;20:288–93; discussion 294. doi: 10.1007/s002689900046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dresler CM, Fortner JG, McDermott K, Bajorunas DR. Metabolic consequences of (regional) total pancreatectomy. Ann Surg . 1991;214:131–140. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199108000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller MW, Friess H, Kleeff J, Dahmen R, Wagner M, Hinz U, Breisch-Girbig D, Ceyhan GO, Büchler MW. Is there still a role for total pancreatectomy? Ann Surg . 2007;246:966–74; discussion 974. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c2ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt CM, Glant J, Winter JM, Kennard J, Dixon J, Zhao Q, Howard TJ, Madura JA, Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD. Total pancreatectomy (R0 resection) improves survival over subtotal pancreatectomy in isolated neck margin positive pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Surgery . 2007;142:572–8; discussion 578. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satoi S, Murakami Y, Motoi F, Sho M, Matsumoto I, Uemura K, Kawai M, Kurata M, Yanagimoto H, Yamamoto T, Mizuma M, Unno M, Kinoshita S, Akahori T, Shinzeki M, Fukumoto T, Hashimoto Y, Hirono S, Yamaue H, Honda G, Kwon M. Reappraisal of Total Pancreatectomy in 45 Patients With Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma in the Modern Era Using Matched-Pairs Analysis: Multicenter Study Group of Pancreatobiliary Surgery in Japan. Pancreas . 2016;45:1003–1009. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsaik AK, Murad MH, Sathananthan A, Moorthy V, Erwin PJ, Chari S, Carter RE, Farnell MB, Vege SS, Sarr MG, Kudva YC. Metabolic and target organ outcomes after total pancreatectomy: Mayo Clinic experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) . 2010;73:723–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong J, Wei A, Ke N, He D, Chian SK, Wei Y, Hu W, Liu X. A case-matched comparison study of total pancreatectomy versus pancreaticoduodenectomy for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Surg . 2017;48:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epelboym I, Winner M, DiNorcia J, Lee MK, Lee JA, Schrope B, Chabot JA, Allendorf JD. Quality of life in patients after total pancreatectomy is comparable with quality of life in patients who undergo a partial pancreatic resection. J Surg Res . 2014;187:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbier L, Jamal W, Dokmak S, Aussilhou B, Corcos O, Ruszniewski P, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A. Impact of total pancreatectomy: short- and long-term assessment. HPB (Oxford) . 2013;15:882–892. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts KJ, Blanco G, Webber J, Marudanayagam R, Sutcliffe RP, Muiesan P, Bramhall SR, Isaac J, Mirza DF. How severe is diabetes after total pancreatectomy? HPB (Oxford) . 2014;16:814–821. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Tan CL, Song HY, Yao Q, Liu XB. Duodenum and ventral pancreas preserving subtotal pancreatectomy for low-grade malignant neoplasms of the pancreas: An alternative procedure to total pancreatectomy for low-grade pancreatic neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol . 2017;23:6457–6466. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i35.6457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirota M, Kamekawa K, Tashima T, Mizumoto M, Ohara C, Beppu T, Shimada S, Yamaguchi Y, Ogawa M. Percutaneous embolization of the distal pancreatic duct to treat intractable pancreatic juice fistula. Pancreas . 2001;22:214–216. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200103000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engel S, Remine WH, Dockerty MB, Grindlay JH, Bartholomew LG. Effect of ligation of pancreatic ducts on chronic pancreatitis: experimental study. Arch Surg . 1962;85:1031–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collard M, Marchese T, Guedj N, Cauchy F, Chassaing C, Ronot M, Dokmak S, Soubrane O, Sauvanet A. Is Routine Splenectomy Justified for All Left-Sided Pancreatic Cancers? Ann Surg Oncol . 2019;26:1071–1078. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-07123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SH, Kang CM, Satoi S, Sho M, Nakamura Y, Lee WJ. Proposal for splenectomy-omitting radical distal pancreatectomy in well-selected left-sided pancreatic cancer: multicenter survey study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci . 2013;20:375–381. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0549-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang F, Jin C, Warshaw AL, You L, Mao Y, Fu D. Total pancreatectomy for pancreatic malignancy with preservation of the spleen. J Surg Oncol . 2019;119:784–793. doi: 10.1002/jso.25377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrone CR, Konstantinidis IT, Sahani DV, Wargo JA, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Twenty-three years of the Warshaw operation for distal pancreatectomy with preservation of the spleen. Ann Surg . 2011;253:1136–1139. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318212c1e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen PJ, Kuk D, Castillo CF, Basturk O, Wolfgang CL, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Ferrone CR, Morales-Oyarvide V, He J, Weiss MJ, Hruban RH, Gönen M, Klimstra DS, Mino-Kenudson M. Multi-institutional Validation Study of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (8th Edition) Changes for T and N Staging in Patients With Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg . 2017;265:185–191. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konstantinidis IT, Warshaw AL, Allen JN, Blaszkowsky LS, Castillo CF, Deshpande V, Hong TS, Kwak EL, Lauwers GY, Ryan DP, Wargo JA, Lillemoe KD, Ferrone CR. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: is there a survival difference for R1 resections versus locally advanced unresectable tumors? Ann Surg . 2013;257:731–736. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318263da2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CR, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery . 2017;161:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW, Yeo CJ, Büchler MW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Surgery . 2007;142:761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Yeo CJ, Büchler MW. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery . 2007;142:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Clavien PA. Assessment of complications after pancreatic surgery: A novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg . 2006;244:931–7; discussion 937. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000246856.03918.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bockhorn M, Uzunoglu FG, Adham M, Imrie C, Milicevic M, Sandberg AA, Asbun HJ, Bassi C, Büchler M, Charnley RM, Conlon K, Cruz LF, Dervenis C, Fingerhutt A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hartwig W, Lillemoe KD, Montorsi M, Neoptolemos JP, Shrikhande SV, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vashist YK, Vollmer C, Yeo CJ, Izbicki JR International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a consensus statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Surgery . 2014;155:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutherland DE, Radosevich DM, Bellin MD, Hering BJ, Beilman GJ, Dunn TB, Chinnakotla S, Vickers SM, Bland B, Balamurugan AN, Freeman ML, Pruett TL. Total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg . 2012;214:409–24; discussion 424. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Struyvenberg MR, Fong ZV, Martin CR, Tseng JF, Clancy TE, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Tillman HJ, Bellin MD, Freedman SD. Impact of Treatments on Diabetic Control and Gastrointestinal Symptoms After Total Pancreatectomy. Pancreas . 2017;46:1188–1195. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conci S, Ruzzenente A, Bertuzzo F, Campagnaro T, Guglielmi A, Iacono C. Total Dorsal Pancreatectomy, an Alternative to Total Pancreatectomy: Report of a New Case and Literature Review. Dig Surg . 2019;36:363–368. doi: 10.1159/000490198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda A, Boku N, Fukutomi A, Kondo S, Kinoshita T, Nagino M, Uesaka K. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine versus S-1 in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japan Adjuvant Study Group of Pancreatic Cancer (JASPAC-01) Jpn J Clin Oncol . 2008;38:227–229. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuda R, Miyasaka Y, Ohishi Y, Yamamoto T, Saeki K, Mochidome N, Abe A, Ozono K, Shindo K, Ohtsuka T, Kikutake C, Nakamura M, Oda Y. Concomitant Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Is an Independent Predictive Factor for the Occurrence of New Cancer in the Remnant Pancreas. Ann Surg . 2020;271:941–948. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikegawa T, Masuda A, Sakai A, Toyama H, Zen Y, Sofue K, Nakagawa T, Shiomi H, Takenaka M, Kobayashi T, Yoshida M, Arisaka Y, Okabe Y, Kutsumi H, Fukumoto T, Azuma T. Multifocal cysts and incidence of pancreatic cancer concomitant with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Pancreatology . 2018;18:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Åkerberg D, Björnsson B, Ansari D. Factors influencing receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery for pancreatic cancer: a two-center retrospective cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol . 2017;52:56–60. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1228118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merkow RP, Bilimoria KY, Tomlinson JS, Paruch JL, Fleming JB, Talamonti MS, Ko CY, Bentrem DJ. Postoperative complications reduce adjuvant chemotherapy use in resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg . 2014;260:372–377. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duggan SN. Negotiating the complexities of exocrine and endocrine dysfunction in chronic pancreatitis. Proc Nutr Soc . 2017;76:484–494. doi: 10.1017/S0029665117001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarles H. Chronic pancreatitis and diabetes. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab . 1992;6:745–775. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Czakó L, Hegyi P, Rakonczay Z Jr, Wittmann T, Otsuki M. Interactions between the endocrine and exocrine pancreas and their clinical relevance. Pancreatology . 2009;9:351–359. doi: 10.1159/000181169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ionescu-Tirgoviste C, Gagniuc PA, Gubceac E, Mardare L, Popescu I, Dima S, Militaru M. A 3D map of the islet routes throughout the healthy human pancreas. Sci Rep . 2015;5:14634. doi: 10.1038/srep14634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menge BA, Tannapfel A, Belyaev O, Drescher R, Müller C, Uhl W, Schmidt WE, Meier JJ. Partial pancreatectomy in adult humans does not provoke beta-cell regeneration. Diabetes . 2008;57:142–149. doi: 10.2337/db07-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahrén B, Andrén-Sandberg A. Capacity to secrete islet hormones after subtotal pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg . 1993;159:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahrén B, Tranberg KG, Andrén-Sandberg A, Bengmark S. Subtotal pancreatectomy for cancer: closure of the pancreatic remnant with staplers. HPB Surg . 1990;2:29–35; discussion 35. doi: 10.1155/1990/73475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gall FP. Subtotal duodeno-pancreatectomy for carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Preliminary report of an alternative operation to total pancreatectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol . 1988;14:387–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawaida H, Kono H, Hosomura N, Amemiya H, Itakura J, Fujii H, Ichikawa D. Surgical techniques and postoperative management to prevent postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatic surgery. World J Gastroenterol . 2019;25:3722–3737. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i28.3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warshaw AL. Distal pancreatectomy with preservation of the spleen. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci . 2010;17:808–812. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0226-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Covantev S, Mazuruc N, Belic O. The Arterial Supply of the Distal Part of the Pancreas. Surg Res Pract . 2019;2019:5804047. doi: 10.1155/2019/5804047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen JS, Liu G, Li TR, Chen JY, Xu QM, Guo YZ, Li M, Yang L. Pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: Risk factors and preventive strategies. J Cancer Res Ther . 2019;15:857–863. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_364_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schawkat K, Eshmuminov D, Lenggenhager D, Endhardt K, Vrugt B, Boss A, Petrowsky H, Clavien PA, Reiner CS. Preoperative Evaluation of Pancreatic Fibrosis and Lipomatosis: Correlation of Magnetic Resonance Findings With Histology Using Magnetization Transfer Imaging and Multigradient Echo Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Invest Radiol . 2018;53:720–727. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desaki R, Mizuno S, Tanemura A, Kishiwada M, Murata Y, Azumi Y, Kuriyama N, Usui M, Sakurai H, Tabata M, Isaji S. A new surgical technique of pancreaticoduodenectomy with splenic artery resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head and/or body invading splenic artery: impact of the balance between surgical radicality and QOL to avoid total pancreatectomy. Biomed Res Int . 2014;2014:219038. doi: 10.1155/2014/219038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zdenkowski N, Radvan G, Pugliese L, Charlton J, Oldmeadow C, Fraser A, Bonaventura A. Treatment of pancreatic insufficiency using pancreatic extract in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a pilot study (PICNIC) Support Care Cancer . 2017;25:1963–1971. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3602-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watanabe Y, Ohtsuka T, Matsunaga T, Kimura H, Tamura K, Ideno N, Aso T, Miyasaka Y, Ueda J, Takahata S, Igarashi H, Inoguchi T, Ito T, Tanaka M. Long-term outcomes after total pancreatectomy: special reference to survivors' living conditions and quality of life. World J Surg . 2015;39:1231–1239. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-2948-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Layer P, Kashirskaya N, Gubergrits N. Contribution of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy to survival and quality of life in patients with pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. World J Gastroenterol . 2019;25:2430–2441. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i20.2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.