Abstract

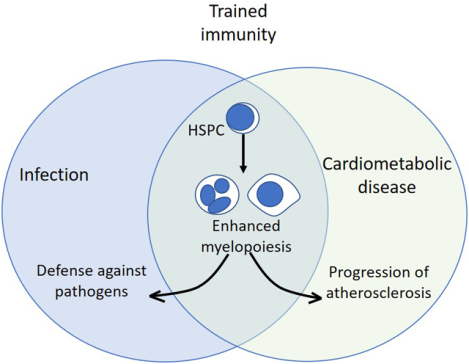

Until recently, immunological memory was considered an exclusive characteristic of adaptive immunity. However, recent advances suggest that the innate arm of the immune system can also mount a type of non-specific memory responses. Innate immune cells can elicit a robust response to subsequent inflammatory challenges after initial activation by certain stimuli, such as fungal-derived agents or vaccines. This type of memory, termed trained innate immunity (also named innate immune memory), is associated with epigenetic and metabolic alterations. Hematopoietic progenitor cells, which are the cells responsible for the generation of mature myeloid cells at steady-state and during inflammation, have a critical contribution to the induction of innate immune memory. Inflammation-triggered alterations in cellular metabolism, the epigenome and transcriptome of hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow promote long-lasting functional changes, resulting in increased myelopoiesis and consequent generation of ‘trained’ innate immune cells. In the present brief review, we focus on the involvement of hematopoietic progenitors in the process of trained innate immunity and its possible role in cardiometabolic disease.

Graphical Abstract

The major function of the immune system is host defense against pathogens. One of the important features of immunity is its ability to remember previous encounters with pathogens, thereby acquiring a long-term protective immunological memory1. Immunological memory has provided the basis for the development of vaccines, which are the most efficient way to prevent several infectious diseases, thereby leading to the increase in life expectancy during the previous century2,3. Even though immunological memory was until recently considered a typical feature of adaptive immunity, recent advances support that certain microbial stimuli can reprogram cell populations of the innate immune system, resulting in the acquisition of memory-like properties; this process is designated innate immune memory or trained immunity4. In addition to differentiated innate immune populations, progenitor cells of the hematopoietic system can also build innate immune memory, which – importantly – can be passed on to their myeloid progeny5. Here, we discuss emerging advances in the field of trained immunity, focusing particularly on the role of hematopoietic progenitors.

Immunological memory in innate immunity

The concept that immunological memory is an exclusive feature of adaptive immunity has been challenged by several reports suggesting that several stimuli, including pathogens and vaccines, cause long-term effects on cell populations of the innate immune system, altering their function and response to secondary challenges with the same or even heterologous stimuli4. According to clinical reports, routine vaccination in Guinea-Bissau with the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), a prototypic stimulus that induces trained immunity, resulted in decreased all-cause infant mortality6. A randomized trial of BCG vaccination in low-birth-weight neonates in Guinea-Bissau further supported a beneficial effect in neonatal survival resulting from a reduction in sepsis7. These studies suggest that BCG confers protection to heterologous infections.

Several experimental studies further evaluated different cell types and mechanisms that promote this type of heterologous protection against secondary infections induced by BCG, as well as β-glucan, the other prototypic stimulus known to induce trained immunity4. Monocytes from BCG-vaccinated volunteers accumulate epigenetic changes and show increased expression of inflammatory cytokines upon secondary encounter of heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus or Candida albicans8. Additionally, BCG administration protected against infection with C. albicans independently of T or B cells8. The induction of trained immunity by BCG is linked to metabolic changes in cells of the mononuclear lineage, including a shift towards glycolysis; these metabolic alterations underlie the induction of epigenetic modifications9,10. In a human challenge study, BCG vaccination could attenuate viremia upon administration of yellow fever virus vaccine11. In this case, IL-1β was identified as the mediator of trained immunity in monocytes, which enabled an improved response of the immune system against the virus11.

β-glucan, a component of the wall of fungi, such as C. albicans, has similar properties as BCG with regards to induction of trained immunity. Non-lethal C. albicans infection in Rag1−/− animals, which lack functional adaptive immune system, protected them from a secondary lethal infection12. β-glucan was additionally shown to train monocytes towards enhanced production of proinflammatory cytokines12. Another study further demonstrated that β-glucan protects against secondary infection with S. aureus in a manner dependent on trained monocytes; in this setting, the training effect of β-glucan was dependent on the induction of aerobic glycolysis and HIF-1α activation in monocytes13. Besides glycolysis, fumarate, a metabolite from the Krebs cycle, as well as mevalonate, a metabolite from the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, can both induce trained immunity-related epigenetic modifications in monocytes14,15.

The aforementioned studies provide solid evidence that trained immunity-associated stimuli have a protective role against secondary infection by inducing appropriate functional alterations in mature cells of the myeloid lineage.

Hematopoietic progenitor cells and emergency myelopoiesis

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) reside in the bone marrow in a quiescent state and are long-lived, being capable to maintain or replenish hematopoiesis throughout life16. HSC are able to respond not only to classical hematopoietic stress, such as hemorrhage or iatrogenic myeloablation (for instance, upon chemotherapy administration), but also to inflammatory types of stress5. Several pathogen-derived products (such as ligands of Toll-like receptors17–19), inflammatory cytokines (such interleukin [IL]-1β, interferons or TNF20–23) or other mediators, and myeloid-specific growth factors (such as, macrophage-colony stimulating factor or granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor24,25), can induce the proliferation of HSC and can trigger their differentiation predominantly towards the myeloid lineage. Such inflammatory mediators instruct HSC towards myelopoiesis via altering their transcriptional program. This process, termed emergency myelopoiesis, aims at providing adequate numbers of innate immune cells to ensure proper host defense5,26. For instance, IL-1 directly triggers proliferation and myeloid lineage commitment of HSC, although chronic exposure to IL-1 results in a loss of their fitness21. The Type I interferon family member interferon-α also stimulates HSC proliferation, accompanied by an impairment of HSC function27. However, the impairment of the self-renewal potential of HSC is self-limited and the quiescence of HSCs is restored upon efficient termination of the inflammatory process21,28.

Hematopoietic stem cells and trained immunity

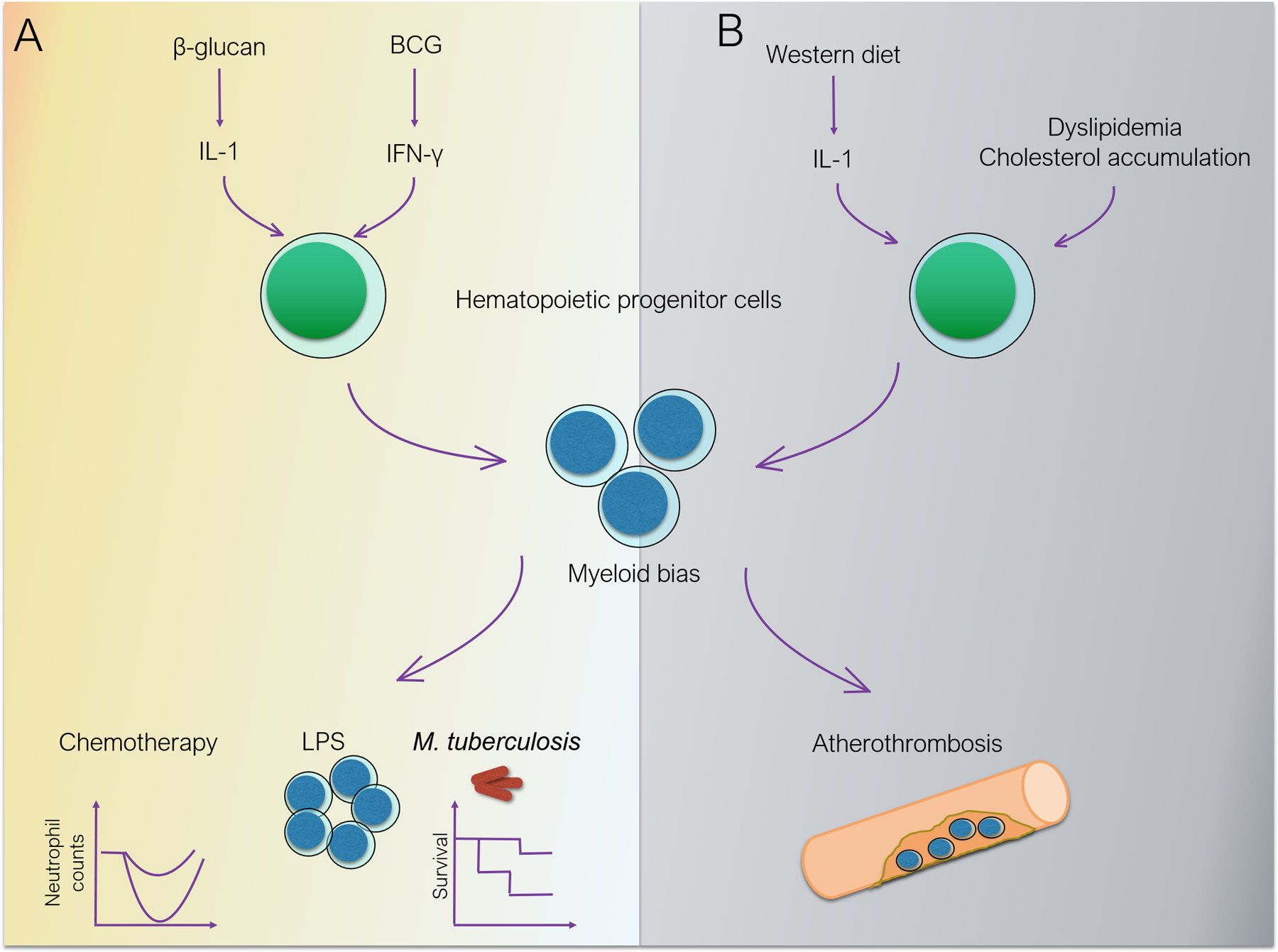

HSC re-enter a dormant state when inflammation resolves; this protects them from DNA damage and exhaustion28. However, recent advances suggest that certain stimuli, especially trained immunity agonists, can induce long-term changes in HSCs, and thereby enhanced responses upon secondary challenges; these HSC alterations also contribute to the development of bone marrow-based trained immunity that can be passed on to the myeloid progeny5. β-glucan administration to mice induces an inflammatory state that drives myelopoiesis in the bone marrow25. Early after β-glucan administration, HSCs proliferate and acquire a bias towards myelopoiesis; this phenotype persists for at least 28 days, as shown by transplantation experiments of HSCs from trained mice to non-trained recipient mice25. The effects of β-glucan on hematopoietic progenitors depend, at least in part, on inflammatory signaling mediated by IL-1 and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor, and are associated with metabolic changes in progenitor cells25 (Figure 1A). Additionally, β-glucan-induced myelopoiesis mediates a protective effect on HSCs, by decreasing the DNA damage and promoting an improved response of the hematopoietic system to chemotherapy-induced leukopenia, as well as to LPS administration25. These findings suggest that except from the acute effect of inflammation on proliferation and myeloid-lineage commitment of HSCs, long-term rewiring of myelopoiesis may also control the response of the innate immune system to secondary stimuli.

Figure 1. Trained immunity, hematopoietic progenitors and cardiovascular disease.

A. Trained immunity. BCG, through interferon-γ and β-glucan, through IL-1, induce long-term modulation of HSC function, promoting myeloid differentiation. The enhanced myelopoiesis confers resistance to chemotherapy and better response to secondary challenges, including protection against secondary mycobacterial infection. B. Cardiovascular disease. Dysregulation of cholesterol trafficking and obesogenic diet drive myeloid differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors and accumulation of inflammatory monocytes in atherosclerotic plaques, fueling cardiovascular disease progression.

Another study also demonstrated that BCG administration to mice had a similar effect on hematopoietic progenitors, driving their myeloid bias, induced by interferon-γ associated with alterations in their transcriptional program29 (Figure 1A). The reprogrammed HSCs can generate macrophages, which confer protection against mycobacterial infection in mice, as shown by parabiosis transplantation experiments29. A recent study further confirmed the role of IL-1 signaling in the stimulation of myelopoiesis upon β-glucan administration, by engaging mice deficient in the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R−/−)30. This study also demonstrated that β-glucan-induced training decreases mortality in mice after mycobacterial infection by reducing the mycobacterial burden in the lung30. This protective effect of β-glucan was lost in IL-1R−/− mice confirming the significance of IL-1 signaling in the training process30 (Figure 1A). The epigenetic basis of trained immunity in hematopoietic progenitors was further demonstrated in a study by Keating et al., showing that histone-lysine N-methyltransferase SET7 plays an important role on the effect of β-glucan-induced reprogramming in the bone marrow31. Deficiency in SET7 methyltransferase in mice (Setd−/−), which mediates histone H3 methylation at lysine 4 (H3K4me), resulted in a less pronounced increase in the transcriptional levels of Csf2 and Il-1b in the bone marrow of β-glucan injected mice upon secondary LPS administration31.

Furthermore, LPS was recently shown to drive long-term epigenetic modulation of HSC that enables them to elicit an improved response to secondary infection with P. aeruginosa32. This study showed that LPS administration drives epigenetic changes in HSCs that are associated with granulopoiesis32. Serial transplantation experiments, initiated four weeks after donor mice were treated with LPS, showed that the epigenetic memory developed in the transplanted HSCs persisted long-term, being able to potentiate emergency myelopoiesis in recipient mice32. Specifically, a more robust response of myelopoiesis to P. aeruginosa infection was observed in recipient mice that received hematopoietic progenitors from LPS-trained mice32. The enhanced myelopoiesis was associated with enhanced pathogen clearance and increased survival32. Besides LPS, polyI:C had a similar effect on epigenetic memory in HSCs, and the transcription factor C/EBPβ played an important role in the induction of the epigenetic memory32. Taken together, several in vivo studies in mice show that trained immunity can rewire HSCs towards increased myelopoiesis, thereby conferring a protective effect against different types of major hematopoietic stress, such as chemotherapy-induced myeloablation or infection.

In addition to mouse studies, recent findings further point to the role of trained-immunity agonists in the induction of memory in human hematopoietic progenitors. Vaccination with BCG in adult volunteers revealed that the effect of trained immunity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as revealed by enhanced cytokine production upon secondary challenge, lasts for at least three months, whereas the cellular composition in peripheral blood or bone marrow is not affected33. Transcriptomic analysis of bone marrow Lin−CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells 90 days after BCG vaccination revealed that granulopoiesis-associated pathways were highly enriched, and Hepatic Nuclear Factor 1A (HNF1A) and HNF1B were the transcription factors mediating these alterations33. The notion that granulopoiesis may be modulated by trained immunity was experimentally demonstrated by a recent report that β-glucan-induced reprogramming of granulopoiesis in the bone marrow resulted in production of neutrophils with potent anti-tumor activity34. Moreover, the anti-cancer activity of trained immunity was shown in a further recent study that used a nanobiologic agent, which inhibited tumor growth by inducing trained immunity in the bone marrow35.

Trained immunity in hematopoietic progenitors in the context of cardiovascular disease

Several lines of evidence indicate a critical involvement of myelopoiesis in cardiometabolic disease5 (Figure 1B). Chronic inflammation in cardiometabolic disease drives the activation of hematopoietic progenitors in the bone marrow resulting in the generation of mature myeloid cells, which may bear increased inflammatory potential, thereby culminating in a positive feedback loop5. Obesity is linked to activation of myelopoiesis in the bone marrow, as demonstrated by the enhanced numbers of myeloid progenitor cells and the resulting neutrophilia and monocytosis in obesity models36. The myeloid bias of bone marrow progenitors of obese mice was verified by transplantation experiments. The release of IL-1β by adipose tissue macrophages was held accountable for the enhanced myelopoiesis in the bone marrow36. Interestingly, weight loss in mice and humans reverses neutrophilia and monocytosis36. Additionally, exercise reduces myelopoiesis in obese mice and, consequently, the output of inflammatory cells, through a mechanism that depends on the production of leptin by the adipose tissue37. However, sustained inflammation in the adipose tissue, despite body weight normalization, may contribute to perpetuation of metabolic dysregulation; whether this obesogenic memory is linked with alterations in the bone marrow has not been addressed38.

Another study demonstrated that feeding a western diet to Ldlr−/− mice, which are prone to develop atherosclerosis, results in epigenetic modifications and respective transcriptional and functional changes in myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, in a manner involving IL-1 signaling39. These changes lasted even after shifting mice to normal diet and resulted in enhanced responses to secondary inflammatory stimulation, in a process reminiscent of trained immunity39. In particular, upon induction of trained immunity by western diet, granulocyte-macrophage progenitors proliferate and differentiate into inflammatory monocytes with the ability to release high amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, TNF and interferon-γ, upon secondary stimulation with LPS39. Another intriguing link between trained immunity and chronic cardiometabolic disease is the involvement of cholesterol metabolism. The mevalonate pathway and cholesterol biosynthesis and efflux contribute to induction of trained immunity in monocytes15 as well as in hematopoietic progenitors25. Interestingly, blocking of cholesterol efflux in hematopoietic progenitors in mouse models is associated with the acquisition of a myeloid bias in HSCs promoting myelopoiesis and vascular inflammation40,41. Specifically, ApoE deficiency40 or inactivation of the adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporters ABCA1 and ABCG141, which are major regulators of cholesterol efflux, resulted in proliferative expansion of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in the bone marrow. A recent study in a zebrafish model further demonstrated that apoA-I binding protein 2 regulates emergence of HSPCs in a manner dependent on sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2; consistently, suppression of Srebp2 expression abolished the proliferation of HSPCs in Ldlr−/− mice fed with western diet42.

During acute cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction, there is rapid response of myelopoiesis in the bone marrow, including expansion of a specific myeloid-biased CCR2+ subpopulation of HSCs, which proliferate and migrate from the bone marrow to extramedullary sites43. Interestingly, extramedullary myelopoiesis in the spleen was linked to the rapid generation of monocytes during myocardial infarction44. In a different setting, recurrent myocardial infarction results in a less pronounced inflammatory response, associated with reduced proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow45. Along the same line, ischemic stroke induced by transient occlusion of middle cerebral artery resulted in the activation of HSPCs in the bone marrow46. This effect was attributed to enhanced β3-adrenergic signaling in HSCs, as well as changes in the bone marrow niche, as the expression of Cxcl12, Vcam1 or Angpt1 encoding for molecules mediating HSC retention, was significantly downregulated 24h after stroke induction46. Abdominal aortic aneurysm development due to chronic angiotensin II infusion into Apoe−/− mice is another model of cardiovascular disease characterized by enhanced myelopoiesis47. Using mice deficient for the receptor of IL-27, the authors further showed that this cytokine was critical both for the development of the aneurysm and the proliferation of HSPCs47. Another study further confirmed that chronic angiotensin II infusion in wild-type mice results in the expansion of hematopoietic progenitors and their differentiation towards pro-inflammatory CCR2+ monocytes48. Although a direct impact of angiotensin II on HSPCs was not shown, the expression of angiotensin II receptor type 1a in HSCs suggested that angiotensin II might act directly on hematopoietic progenitors48.

Clinical studies further provide implications for the role of aberrant myelopoiesis in cardiovascular disease. Individuals with age-associated clonal hematopoiesis, also known as clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, that carry mutations in genes associated with increased risk of myeloid malignancies such as TET2, ASXL1, DNMT3 or SF3B1 have also increased cardiovascular risk49. Studies in animal models of atherothrombosis and heart failure have shown that the increased atherothrombosis in mice partially reconstituted with TET2-deficient BM cells (to mimic TET2 mutation-associated clonal hematopoiesis) depends on aberrant myelopoiesis and enhanced production by progeny macrophages of IL-1β50,51, a cytokine previously associated with atherosclerotic disease in CANTOS trial52.

Conclusion and open issues on trained immunity in cardiometabolic disease

Hematopoietic progenitor cells are critical players in the regulation of inflammation not only in the context of infections but also in the context of chronic inflammatory disorders, such as obesity or atherosclerosis, as well as the sequelae thereof, such as myocardial infarction. In turn, inflammation triggered by agonists of trained immunity can cause epigenetic, transcriptional and functional alterations in progenitors in the bone marrow, resulting in differential responses and of their progeny to secondary inflammatory stimuli. Even though trained immunity may promote a better response in the context of infection via sustained generation of mature leukocytes from the progenitors in the bone marrow, trained immunity may contribute to boosting chronic inflammation in a detrimental fashion, for instance in the context of progression of cardiometabolic disease.

In this context, several questions are still to be answered. Although the role of chronic inflammation and altered myelopoiesis in the progression of cardiometabolic disease is well established, based both on preclinical and clinical studies, the involvement of trained immunity in this process is poorly understood. For instance, it is not known whether short-term inflammatory attacks that resemble the stimuli that drive trained immunity can alter cardiometabolic disease progression by acting on hematopoietic progenitors, or even mature myeloid cells. Despite the fact that there are indications derived from chronic inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis53, that disease exacerbations / flares accelerate atherosclerosis, it is unclear whether trained immunity is the underlying mechanism in such cases. Additionally, it is not known whether the inflammatory stress that follows acute cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction, is also a trigger of trained immunity. In that regard, a recent study demonstrated that acute infarction in mice reprograms myelopoiesis to drive the generation of immunosuppressive monocytes that promote tumor progression54. Although the direct involvement of hematopoietic progenitors in the generation of the tumor-promoting monocyte phenotype was established by transplantation experiments54, the study did not address whether innate immune memory is the underlying mechanism.

Interestingly, trained immunity and cardiometabolic disease share common mechanistic pathways, including epigenetic changes, such as histone modifications, or macrophage activation in response to cytokines, such as IL-1β and interferon-γ55. Hence, these common pathways may represent therapeutic targets in cardiometabolic disorders. Taken together, a clear mechanistic understanding of the interplay among trained immunity, hematopoietic progenitors and progression of cardiometabolic disease may enable the therapeutic harnessing of trained immunity in these chronic diseases.

Highlights.

A hallmark of trained immunity is enhanced myelopoiesis in the bone marrow and generation of myeloid cells with increased pro-inflammatory preparedness.

Cardiometabolic disease is characterized by enhanced myelopoiesis, which also results in the generation of myeloid cells with increased inflammatory potential.

Trained immunity may contribute to development or progression of cardiometabolic disease.

Therapeutic targeting of trained immunity–related changes in progenitor cells of myeloid lineage may alter cardiometabolic disease progression.

Sources of Funding

The authors are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DE024716 to GH; DE028561, and DE026152 to G.H. and TC), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB1181 to TC), the National Center for Tumor Diseases Partner Site Dresden (to IM) and the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI-FM17-452 to IM).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin

- HSC

Hematopoietic stem cells

- HSPC

hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From Vaccines to Memory and Back. Immunity. 2010;33:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO | Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. WHO. Accessed March 30, 2020 https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/2/07-040089/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Netea MG, van der Meer JWM. Trained Immunity: An Ancient Way of Remembering. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:297–300. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chavakis T, Mitroulis I, Hajishengallis G. Hematopoietic progenitor cells as integrative hubs for adaptation to and fine-tuning of inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:802–811. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0402-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kristensen I, Aaby P, Jensen H. Routine vaccinations and child survival: follow up study in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. BMJ. 2000;321:1435–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aaby P, Roth A, Ravn H, Napirna BM, Rodrigues A, Lisse IM, Stensballe L, Diness BR, Lausch KR, Lund N, Biering-Sørensen S, Whittle H, Benn CS. Randomized trial of BCG vaccination at birth to low-birth-weight children: beneficial nonspecific effects in the neonatal period? J Infect Dis. 2011;204:245–252. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F, Joosten LAB, Ifrim DC, Saeed S, Jacobs C, van Loenhout J, de Jong D, Stunnenberg HG, Xavier RJ, van der Meer JWM, van Crevel R, Netea MG. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17537–17542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202870109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penkov S, Mitroulis I, Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Immunometabolic Crosstalk: An Ancestral Principle of Trained Immunity? Trends in Immunology. 2018;40:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arts RJW, Carvalho A, La Rocca C, et al. Immunometabolic Pathways in BCG-Induced Trained Immunity. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2562–2571. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arts RJW, Moorlag SJCFM, Novakovic B, et al. BCG Vaccination Protects against Experimental Viral Infection in Humans through the Induction of Cytokines Associated with Trained Immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:89–100.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quintin J, Saeed S, Martens JHA, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Ifrim DC, Logie C, Jacobs L, Jansen T, Kullberg B-J, Wijmenga C, Joosten LAB, Xavier RJ, van der Meer JWM, Stunnenberg HG, Netea MG. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng S-C, Quintin J, Cramer RA, et al. mTOR- and HIF-1α-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science. 2014;345:1250684. doi: 10.1126/science.1250684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arts RJW, Novakovic B, Ter Horst R, et al. Glutaminolysis and Fumarate Accumulation Integrate Immunometabolic and Epigenetic Programs in Trained Immunity. Cell Metab. 2016;24:807–819. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bekkering S, Arts RJW, Novakovic B, et al. Metabolic Induction of Trained Immunity through the Mevalonate Pathway. Cell. 2018;172:135–146.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendelson A, Frenette PS. Hematopoietic stem cell niche maintenance during homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Med. 2014;20:833–846. doi: 10.1038/nm.3647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takizawa H, Fritsch K, Kovtonyuk LV, Saito Y, Yakkala C, Jacobs K, Ahuja AK, Lopes M, Hausmann A, Hardt W-D, Gomariz Á, Nombela-Arrieta C, Manz MG. Pathogen-Induced TLR4-TRIF Innate Immune Signaling in Hematopoietic Stem Cells Promotes Proliferation but Reduces Competitive Fitness. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:225–240.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitroulis I, Chen L-S, Singh RP, et al. Secreted protein Del-1 regulates myelopoiesis in the hematopoietic stem cell niche. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3624–3639. doi: 10.1172/JCI92571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagai Y, Garrett KP, Ohta S, Bahrun U, Kouro T, Akira S, Takatsu K, Kincade PW. Toll-like receptors on hematopoietic progenitor cells stimulate innate immune system replenishment. Immunity. 2006;24:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamashita M, Passegué E. TNF-α Coordinates Hematopoietic Stem Cell Survival and Myeloid Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25:357–372.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pietras EM, Mirantes-Barbeito C, Fong S, Loeffler D, Kovtonyuk LV, Zhang S, Lakshminarasimhan R, Chin CP, Techner J-M, Will B, Nerlov C, Steidl U, Manz MG, Schroeder T, Passegué E. Chronic interleukin-1 exposure drives haematopoietic stem cells towards precocious myeloid differentiation at the expense of self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:607–618. doi: 10.1038/ncb334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Essers MAG, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA, Trumpp A. IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009;458:904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature07815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldridge MT, King KY, Boles NC, Weksberg DC, Goodell MA. Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-gamma in response to chronic infection. Nature. 2010;465:793–797. doi: 10.1038/nature09135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mossadegh-Keller N, Sarrazin S, Kandalla PK, Espinosa L, Stanley ER, Nutt SL, Moore J, Sieweke MH. M-CSF instructs myeloid lineage fate in single haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2013;497:239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature12026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitroulis I, Ruppova K, Wang B, et al. Modulation of Myelopoiesis Progenitors Is an Integral Component of Trained Immunity. Cell. 2018;172:147–161.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitroulis I, Kalafati L, Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Myelopoiesis in the Context of Innate Immunity. Journal of Innate Immunity. 2018;10:365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter D, Lier A, Geiselhart A, et al. Exit from dormancy provokes DNA-damage-induced attrition in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2015;520:549–552. doi: 10.1038/nature14131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pietras EM, Lakshminarasimhan R, Techner J-M, Fong S, Flach J, Binnewies M, Passegué E. Re-entry into quiescence protects hematopoietic stem cells from the killing effect of chronic exposure to type I interferons. J Exp Med. 2014;211:245–262. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufmann E, Sanz J, Dunn JL, et al. BCG Educates Hematopoietic Stem Cells to Generate Protective Innate Immunity against Tuberculosis. Cell. 2018;172:176–190.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moorlag SJCFM, Khan N, Novakovic B, Kaufmann E, Jansen T, van Crevel R, Divangahi M, Netea MG. β-Glucan Induces Protective Trained Immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection: A Key Role for IL-1. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107634. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keating ST, Groh L, van der Heijden CDCC, et al. The Set7 Lysine Methyltransferase Regulates Plasticity in Oxidative Phosphorylation Necessary for Trained Immunity Induced by β-Glucan. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107548. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laval B de, Maurizio J, Kandalla PK, et al. C/EBPβ-Dependent Epigenetic Memory Induces Trained Immunity in Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:657–674. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cirovic B, de Bree LCJ, Groh L, et al. BCG Vaccination in Humans Elicits Trained Immunity via the Hematopoietic Progenitor Compartment. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28: 322–334.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalafati L, Kourtzelis I, Schulte-Schrepping J, et al. Innate Immune Training of Granulopoiesis Promotes Anti-tumor Activity. Cell 220; 183: 771–785. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Priem B, van Leent MTM, Teunissen JPA, et al. Trained Immunity-Promoting Nanobiologic Therapy Suppresses Tumor Growth and Potentiates Checkpoint Inhibition. Cell 220; 183: 786–801.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagareddy PR, Kraakman M, Masters SL, et al. Adipose tissue macrophages promote myelopoiesis and monocytosis in obesity. Cell Metab. 2014;19:821–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frodermann V, Rohde D, Courties G, et al. Exercise reduces inflammatory cell production and cardiovascular inflammation via instruction of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2019;25:1761–1771. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0633-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitz J, Evers N, Awazawa M, Nicholls HT, Brönneke HS, Dietrich A, Mauer J, Bluüher M, Bruüning JC. Obesogenic memory can confer long-term increases in adipose tissue but not liver inflammation and insulin resistance after weight loss. Mol Metab. 2016;5:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christ A, Günther P, Lauterbach MAR, et al. Western Diet Triggers NLRP3-Dependent Innate Immune Reprogramming. Cell. 2018;172:162–175.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy AJ, Akhtari M, Tolani S, Pagler T, Bijl N, Kuo C-L, Wang M, Sanson M, Abramowicz S, Welch C, Bochem AE, Kuivenhoven JA, Yvan-Charvet L, Tall AR. ApoE regulates hematopoietic stem cell proliferation, monocytosis, and monocyte accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4138–4149. doi: 10.1172/JCI57559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yvan-Charvet L, Pagler T, Gautier EL, Avagyan S, Siry RL, Han S, Welch CL, Wang N, Randolph GJ, Snoeck HW, Tall AR. ATP-binding cassette transporters and HDL suppress hematopoietic stem cell proliferation. Science. 2010;328:1689–1693. doi: 10.1126/science.1189731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu Q, Yang X, Lv J, et al. AIBP-mediated cholesterol efflux instructs hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell fate. Science (New York, NY). 2019;363:1085–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.aav1749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dutta P, Sager HB, Stengel KR, et al. Myocardial Infarction Activates CCR2+ Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leuschner F, Rauch PJ, Ueno T, et al. Rapid monocyte kinetics in acute myocardial infarction are sustained by extramedullary monocytopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2012;209:123–137. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cremer S, Schloss MJ, Vinegoni C, Foy BH, Zhang S, Rohde D, Hulsmans M, Feruglio PF, Schmidt S, Wojtkiewicz G, Higgins JM, Weissleder R, Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Diminished Reactive Hematopoiesis and Cardiac Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Recurrent Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:901–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Courties G, Herisson F, Sager HB, Heidt T, Ye Y, Wei Y, Sun Y, Severe N, Dutta P, Scharff J, Scadden DT, Weissleder R, Swirski FK, Moskowitz MA, Nahrendorf M. Ischemic stroke activates hematopoietic bone marrow stem cells. Circulation Research. 2015;116:407–417. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peshkova IO, Aghayev T, Fatkhullina AR, Makhov P, Titerina EK, Eguchi S, Tan YF, Kossenkov AV, Khoreva MV, Gankovskaya LV, Sykes SM, Koltsova EK. IL-27 receptor-regulated stress myelopoiesis drives abdominal aortic aneurysm development. Nature Communications. 2019;10:5046. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13017-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim S, Zingler M, Harrison JK, Scott EW, Cogle CR, Luo D, Raizada MK. Angiotensin II Regulation of Proliferation, Differentiation, and Engraftment of Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex: 1979). 2016;67:574–584. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377:111–121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fuster JJ, MacLauchlan S, Zuriaga MA, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice. Science. 2017;355:842–847. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, MacLauchlan S, Katanasaka Y, Sano M, Zuriaga MA, Yoshiyama M, Goukassian D, Cooper MA, Fuster JJ, Walsh K. Tet2-mediated Clonal Hematopoiesis Accelerates Heart Failure through a Mechanism Involving the IL-1β/NLRP3 Inflammasome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377:1119–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Myasoedova E, Chandran A, Ilhan B, Major BT, Michet CJ, Matteson EL, Crowson CS. The Role of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Flare and Cumulative Burden of RA Severity in the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:560- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koelwyn GJ, Newman AAC, Afonso MS, et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates breast cancer via innate immune reprogramming. Nat Med. 2020;26:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0964-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis Frank M, Gallagher Katherine A Epigenetic Mechanisms in Monocytes/Macrophages Regulate Inflammation in Cardiometabolic and Vascular Disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2019;39:623–634. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.312135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]