Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Total laryngectomy in thyroid cancer is controversial. Functional and oncologic outcomes are needed to inform surgical indications in this population.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was performed at a tertiary referral center from 1997 to 2018 to identify patients with a diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma who underwent total laryngectomy. Complications, survival outcomes, and functional outcomes were analyzed.

Results:

Thirty patients met inclusion criteria. The mean age was 62 years (range, 30–88 years) and the male to female ratio was 1:2.75. The most common diagnosis was well differentiated thyroid cancer (53.3%), followed by poorly differentiated (30%) and anaplastic (16.7%). Total laryngectomy was performed with a 10% rate of Clavien-Dindo grade III-V complications.

Median overall survival was 40 months (range, 1–237). Five-year overall survival was 39.5% and disease specific survival was 51.1%. Locoregional control was achieved in 80.0% of patients. Twelve months post-operatively, 100% of surviving patients were taking oral intake and 86.4% had self-reported functional voice.

Conclusion:

Total laryngectomy for locally advanced thyroid cancer is safe and provides acceptable rates of locoregional control. While the risk of distant metastases remains high, advances in systemic therapy may justify aggressive local control strategies to improve quality of life.

Keywords: thyroid cancer, laryngectomy, survival outcomes, functional outcomes

Introduction

Laryngeal involvement in thyroid cancer is uncommon and clinically challenging to manage. Gross extrathyroidal extension occurs in 5–13% of patients with papillary thyroid cancer, and is more frequently observed in those with poorly differentiated carcinoma.1–3 Compared to the excellent outcomes seen in patients with limited disease, extrathyroidal extension and aggressive histology are associated with higher risk of locoregional recurrence and death.4–6 In the case of airway involvement, local progression can be highly morbid and commonly results in death by airway hemorrhage or obstruction.7,8

Total laryngectomy for thyroid cancer is employed to varying degrees by thyroid surgeons. Primary radiation approaches have also been proposed.9 There is an understandable desire to preserve the functional larynx wherever possible. However, evidence shows that segmental airway resection including total laryngectomy improves locoregional control and affords superior survival outcomes when compared to shave or subtotal resection in patients with transmural involvement.10–13 The functional consequences of laryngectomy in this patient population have not been recently reported to our knowledge. The oncologic outcome for patients with locally advanced thyroid cancer who undergo total laryngectomy as a treatment approach is also unknown.

The objective of this study is to investigate whether total laryngectomy provides acceptable oncologic and functional outcomes in locally advanced thyroid cancer with airway involvement in order to inform surgical decision-making in this population.

Materials and Methods

Following approval from the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, a retrospective review was conducted of all patients with a diagnosis of thyroid cancer who underwent total laryngectomy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center from January 1997 to January 2018. Cases were identified using International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) diagnostic codes and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Clinical records, operative notes, imaging, and pathology reports were reviewed.

Surgery was performed with the goal of gross total resection. All patients had deep extraluminal or intraluminal extension of tumor into the larynx, cricoid, or post-cricoid region on pre-operative structural imaging, based on the classification proposed by Brauckhoff et al.14 In some cases where there was uncertainty on pre-operative imaging regarding the depth of invasion, endoscopic examination was also included. Reconstruction was based on the extent of resection and surgeon preference. Patients were excluded if the laryngectomy was performed for reasons other than thyroid cancer (for example, if the thyroid carcinoma was incidentally detected in the operative specimen from a laryngectomy performed for squamous cell carcinoma).

Complication, length of stay, and readmission data were obtained from the medical record. Complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.15 Calcium levels were corrected using the formula corrected calcium = serum calcium + 0.8*(normal serum albumin – measured serum albumin), where “normal serum albumin” was considered to be 4.0g/dL. Normal serum calcium level was defined as 8.5–10.5mg/dL and severe hypocalcemia was defined as < 7.0mg/dL.

The primary outcome was locoregional control. Secondary outcomes were overall survival, disease specific survival, functional voice, and functional swallow. Functional voice was defined as speech quality that allowed the patient to be understood when conversing in person or on the telephone, as reported by the patient to the speech and language pathologist. Functional swallow was defined as the patient taking daily oral intake (supplemental feeds via gastrostomy tube were permitted). Survival outcomes were measured from the time of surgery to the occurrence of an event (recurrence or death) or to the last follow-up, whichever was later. Functional outcomes were measured at 12 months post-operatively. Follow-up occurred in person and was scheduled in accordance with the surgeon’s preference.

Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier curves starting at the date of surgery. The log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics v.25 (Windows) software (IBM, Armonk, NY). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 30 patients were identified who met the inclusion criteria. Most had a histological diagnosis of well differentiated thyroid cancer (n=16), with fewer poorly differentiated (n=9) and anaplastic (n=5) diagnoses. Two-thirds of previously treated patients had recurrent disease. In this group, the median interval from initial diagnosis to laryngectomy was 6 years (range, 0–23 years). Patient and tumor characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The median duration of follow up was 8.8 years (range, 0.9–19.8 years).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with thyroid cancer who underwent total laryngectomy.

| Characteristic | No. (%) (n=30) |

|---|---|

| Mean age (range) | 62 (30–88) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 8 (27) |

| Female | 22 (73) |

| Prior treatment | |

| Surgery | 20 (67) |

| Radioactive iodine | 16 (53) |

| External beam radiotherapy | 9 (30) |

| Systemic therapy | 0 (0) |

| Histological type | |

| Papillary carcinoma subtypes | |

| Classic | 6 (20) |

| Follicular | 1 (3) |

| Tall cell | 7 (23) |

| Hurthle cell carcinoma | 2 (7) |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 9 (30) |

| Anaplastic carcinoma | 5 (17) |

| Surgical extent | |

| Total laryngectomy | 30 (100) |

| Total pharyngectomy | 9 (30) |

| Esophagectomy | 5 (17) |

| Adjuvant treatment | |

| Radioactive iodine | 7 (23) |

| External beam radiotherapy | 10 (33) |

| Systemic therapy | 8 (27) |

Surgical Details

Sixty-seven percent of patients presented with recurrent disease and had undergone prior surgery (n=20), of which six were believed to have been incompletely excised based on the operative and pathology report. All patients underwent total laryngectomy, with 30% requiring resection of adjacent structures including the pharynx and esophagus due to disease extent (Table 1).

Reconstructive approaches varied depending on the extent of resection as detailed in Table 2. In patients who had no or limited pharyngectomy, the majority (57%) had primary closure with no reconstruction. The remainder had either a pectoralis major pedicled myofascial flap overlaid across the primary pharyngeal closure (24%) or a fasciocutaneous free flap incorporated into the closure (19%). In those who had total pharyngectomy with or without esophagectomy, either a gastric pull-up (22%) or free flap (78%) was used.

Table 2.

Reconstruction of surgical defects in patients who underwent total laryngectomy for thyroid cancer.

| Extent of Resection | Reconstruction | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Closure (n=12) | Regional Tissue Transfer (n=7) | Free Flap (n=11) | |

| Total laryngectomy +/− limited pharyngectomy (n=21) | 12 primary closure | 5 pectoralis major | 3 radial forearm 1 anterolateral thigh |

| Total laryngectomy + total pharyngectomy (n=4) | 4 jejunum | ||

| Total laryngectomy + total pharyngectomy + esophagectomy (n=5) | 2 gastric pull-up | 3 jejunum | |

Perioperative Complications

Post-operative hypocalcemia was a near-ubiquitous complication and was observed in 27 out of 29 patients (one patient had no post-operative calcium levels recorded). Severe hypocalcemia (corrected calcium <7.0mg/dL) was recorded in 12 patients (41.4%) This was managed with a combination of enteral and intravenous supplementation. No patients developed life-threatening sequelae of hypocalcemia. The median nadir corrected serum calcium level was 7.0mg/dL (range, 5.7–9.2mg/dL). The lowest level was most commonly recorded on post-operative day one, but ranged from day zero to day eight. The nadir occurred within the first five post-operative days in 93.1% of patients.

Pharyngocutaneous fistulas developed in five patients (16.7%), two of whom had been previously irradiated. This represented a 22.2% rate of fistula in the irradiated group and 14.3% in the non-irradiated group. Initial management was conservative in all patients and involved at least daily wound packing and dressing changes. This approach was successful in four patients and resulted in complete closure of the fistula. The fifth patient suffered a severe secondary post-operative hemorrhage and died. This represented the only post-operative fatality (3.3%).

Two other (6.7%) patients had severe complications (Clavien-Dindo grade III and IV). One patient who had undergone a thoracoscopic-assisted gastric pull-up had a delayed large post-operative pneumothorax resulting in respiratory failure and prolonged ICU admission. The other patient had a non-surgical complication of acute coronary syndrome requiring inpatient percutaneous coronary intervention. Both patients made full recoveries and were discharged home.

The median length of hospital stay was 14 days (range, 8–51 days). There were two unplanned readmissions.

Adjuvant Therapy

Half of the cohort received adjuvant therapy, including one or more of the following: radioactive iodine (RAI), external beam radiotherapy, and systemic therapy (Table 1). Seven patients received post-operative RAI, and five of them also received radiotherapy in an attempt to improve locoregional control. Three patients who received post-operative radiotherapy had previously been irradiated.

In all eight patients who received systemic therapy, it was given due to the presence of distant metastases. Cytotoxic therapy was used in five patients and tyrosine kinase inhibition (sorafenib or lenvatinib) in three patients. Radiation was also employed for the management of select distant metastases, particularly those involving the central nervous system.

Survival Outcomes

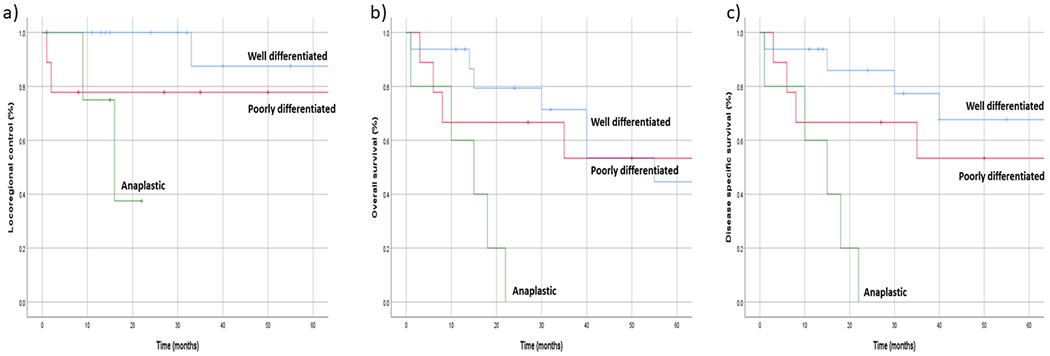

Locoregional control at 2 years was 84.7%, and at 5 years was 78.1%. Three patients failed locally at 1, 2, and 9 months post-operatively. Two patients developed regional nodal recurrence at 16 and 33 months post-operatively, and both subsequently went on to develop distant metastases. When stratified by histological differentiation, 5-year overall survival in well differentiated, poorly differentiated, and anaplastic carcinoma was 87.5%, 77.8%, and 37.5%, respectively (Figure 1). Locoregional control was worse in patients with anaplastic carcinoma when compared to well and poorly differentiated subtypes (P=0.047). None of the patients who developed locoregional recurrence were candidates for surgical salvage.

Figure 1.

Outcomes of a) locoregional control, b) overall survival, and c) disease specific survival in patients with thyroid cancer who underwent total laryngectomy, stratified according to histological differentiation.

Median overall survival was 40 months (range, 1–237 months). Overall survival at 2 years and 5 years was 61.8% and 39.5% respectively; and disease specific survival at 2 and 5 years was 64.8% and 51.1% respectively. When stratified by histological differentiation, 5-year disease specific survival in well differentiated, poorly differentiated, and anaplastic carcinoma was 67.5%, 53.3%, and 0%, respectively (Figure 1). Disease specific survival was worse in patients with anaplastic carcinoma (P=0.001), and with esophageal involvement (P=0.027). Prior treatment or prior incomplete excision did not predict survival outcomes (P=0.662 and P=0.692, respectively).

The most common mode of failure was distant metastases. At initial presentation, 16.7% of patients were found to have distant metastases and a further 40% went on to develop them during the study period. The most common site of distant metastasis was the lung (82.3%), followed by bone (29.4%) and brain (11.8%). Median time to development of distant metastases was 9 months (range, 1–69 months). Among those with distant metastatic disease at presentation, median overall survival was 24 months (range, 6–112 months).

Functional Outcomes

Twelve months post-operatively, 100% of surviving patients were taking oral intake and 86.4% had self-reported functional voice (Table 3). Voice was achieved most commonly with the use of a tracheoesophageal valve, which was placed primarily in 10 patients (33.3%) and secondarily in five patients (16.7%).

Table 3.

Functional outcomes of patients with thyroid cancer who underwent total laryngectomy at 12 months post-operatively.a.

| Functional Outcome | No. (%) (n=22) |

|---|---|

| Swallow status | |

| Full oral diet | 20 (91) |

| Combined oral diet with supplemental tube feeds | 2 (9) |

| Full tube feeds | 0 (0) |

| Voice status | |

| Tracheoesophageal valve | 11 (50) |

| Electrolarynx | 7 (32) |

| Esophageal speech | 1 (4) |

| No functional voice | 3 (14) |

n=22 due to 8 patients being deceased or lost to follow up prior to 12 months

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to examine the outcomes of laryngectomy in patients with advanced thyroid cancer.

These data show a 5-year locoregional control rate of 78.1%. There is a paucity of comparable data in the literature; however, this rate is similar to the 83.1% rate of local recurrence reported by Gaissert in 2007.11 While some debate exists regarding the optimal management of superficial laryngotracheal invasion,14,16–18 it is accepted that segmental airway resection reduces the risk of local recurrence in patients with deep or intraluminal airway involvement.19–23 The importance of achieving local control in patients to prevent invasive disease that progresses towards airway obstruction, hemorrhage, and death represents an important goal in the management of advanced head and neck cancer. Given the significant morbidity associated with local progression, we consider total laryngectomy in all patients with trans-cartilaginous or intramural involvement of the larynx.

Beckham et al reported the use of definitive radiotherapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced, unresectable, or gross residual non-anaplastic thyroid cancer. They found a 4-year local progression free survival of 77.3% and overall survival of 56.3%, and a 1-year percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy-dependence rate of 10.1%.9 Due to the differences between study groups and in the absence of prospective data, it is difficult to make direct comparisons between treatment approaches. Nevertheless, it illustrates a comparable management option for patients with locally advanced disease. Another strategy currently under investigation is the use of neoadjuvant lenvatinib in locally advanced thyroid cancer with a secondary endpoint “determined by structures requiring resection” (NCT04321954).24 This may offer another option for patients who would have been managed with total laryngectomy in the current cohort.

Despite the excellent locoregional control achieved with total laryngectomy, overall and disease specific survival outcomes in this patient population remain modest. This is likely a reflection of the relatively high rate of distant metastatic disease. Gaissert most recently reported a 5-year overall survival rate of 52% in all patients undergoing segmental laryngotracheal resection, although within their salvage surgical group the rate was 38%.11 Some historical studies have reported survival rates as high as 77–89%.16,17,20,25 Many of these studies included patients with only superficial tracheal involvement and therefore it is possible that this difference reflects the heterogeneity in definition of “airway invasion.” Furthermore, several studies included only patients with well differentiated thyroid cancer who are known to have a better prognosis.

The survival outcomes observed in this cohort are similar to those in patients undergoing total laryngectomy for advanced squamous cell carcinoma26,27 in whom the benefit of surgery in achieving local control is widely accepted. In keeping with this approach, we believe that surgery in patients with locally advanced thyroid cancer has benefit in terms of quantity and potentially quality of life, despite uncertain survival outcomes.

Functional speech and swallow outcomes in the current patient cohort were acceptable. Of those surviving beyond 12 months, 100% had functional swallow and 86.4% had self-reported functional voice. This data was based on the clinical notes recorded by speech and language pathology, rather than validated patient reported outcome measures. This is a limitation in our study methodology. Nevertheless, the data suggests that laryngectomy in these patients provides a satisfactory speech and swallow outcomes.

Serious complications occurred in the minority of patients with one perioperative mortality. Pharyngocutaneous fistula was observed in 14.3% of non-irradiated patients, which is comparable to the 14.3% incidence reported by Sayles and Grant in their meta-analysis of fistula rates in patients undergoing laryngectomy.28 Our irradiated group had a relatively lower rate of 22.2% compared to their reported 27.6%. This may be because the patients in our study had received only prior adjuvant radiotherapy to a maximum dose of 60 cGy compared to the likely higher definitive dose in the meta-analysis.

The post-operative calcium management of the patients in our study is worthy of special mention. The vast majority of our patients developed biochemical hypocalcemia in the immediate post-operative period, despite aggressive enteral repletion in all cases. This was severe in 41.4% of patients. This finding was not unexpected, given the extensive nature of surgery required for disease clearance. An additional contributing factor was that 66.7% of patients had undergone prior surgery and therefore the location and vascular supply of their parathyroid glands was less readily predictable. It is valuable to note that most cases occurred in the first few post-operative days, with stability achieved in 93.1% of patients by day five. We advise intra-operative identification of parathyroid glands wherever possible and close post-operative monitoring of calcium levels in these patients.

Patients presenting with residual or recurrent disease were managed the same way as those who had laryngotracheal involvement at initial presentation. However, it is possible that these three groups of patients have different tumor biology. We compared survival outcomes between the three groups and found no significant differences, although we were limited by small sample sizes. The question of whether patients presenting initially with locally advanced disease should be treated the same way as those who have multiple recurrences remains to be determined. Future research should focus on this area.

An important consideration in this patient group is how to manage those with pre-operative evidence of distant metastases. Ito et al showed that the 5-year cause-specific survival rate in a group of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer presenting with distant metastases who underwent locally curative surgery was 81%.29 This finding, along with advances in novel systemic therapeutics, places emphasis on local control even in the setting of distant disease. As Grillo explained, “resection of the airway invaded by thyroid malignancy … offers prolonged palliation [and] avoids suffocation due to bleeding or obstruction.”30 This approach is supported by our data showing a median overall survival estimate of 24 months in patients with distant metastatic disease at presentation. It is therefore readily conceivable that palliative resection can provide patients with meaningful improvements in duration and quality of life.

The management of patients with anaplastic carcinoma remains challenging. In the present cohort, the diagnosis of anaplastic carcinoma was unexpected and was made on histopathological review of the operative specimen in all cases. This scenario arose when the tumor had focally de-differentiated and the pre-operative biopsy was not representative of the entire tumor. It is not our practice to perform total laryngectomy in patients with confirmed anaplastic carcinoma. Current guidelines support complete surgical resection to aid in local control only if an R0 resection is considered achievable.31 In patients with laryngotracheal involvement, this is seldom possible without significant short-term morbidity. The high rate of distant failure and dismal survival outcomes in this group make it difficult to justify such extensive surgery when life expectancy is very limited. Systemic therapies offer some hope for improving survival outcomes in select patients. The neoadjuvant use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors in patients with BRAF-mutated anaplastic thyroid cancer has now become standard of care at our institution.32 A partial response to this regimen may provide a window of opportunity to perform surgical resection and achieve durable local control.

This study was limited by factors common to all retrospective data; including selection bias and missing data. The methods used to determine laryngotracheal invasion differed between patients. This introduces a degree of uncertainty into the clinical assessment and thus reduces the generalizability of the results. Due to the small study population, all subtypes of DTC were grouped together in order to allow comparison with poorly differentiated and anaplastic groups. It is likely that there are differences in outcomes within the DTC subgroups, however a larger study population would be required to make these comparisons. Finally, this study spans a long time period and it is likely that diagnostic tests and treatment options (particularly systemic therapies) have evolved significantly over this time.

Conclusions

Total laryngectomy for locally advanced differentiated thyroid cancer is safe and results in excellent locoregional control rates and acceptable functional outcomes. Although the risk of distant metastases in this cohort remains high, advances in systemic therapy may justify aggressive local control strategies to improve speech and swallow outcomes and thus quality of life.

Synopsis for table of contents:

Laryngectomy for patients with advanced thyroid cancer is controversial. This retrospective cohort study demonstrates excellent locoregional control rates and acceptable functional outcomes. Surgery should be considered as one of the management options for these patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding Acknowledgment: This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Disclosures and funding sources: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest / Disclosure Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest

Data Availability Statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hay ID, Johnson TR, Kaggal S, et al. Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (PTC) in Children and Adults: Comparison of Initial Presentation and Long-Term Postoperative Outcome in 4432 Patients Consecutively Treated at the Mayo Clinic During Eight Decades (1936–2015). World J Surg. 2018;42(2):329–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishida T, Nakao K, Hamaji M. Differentiated thyroid carcinoma with airway invasion: indication for tracheal resection based on the extent of cancer invasion. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114(1):84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avenia N, Vannucci J, Monacelli M, et al. Thyroid cancer invading the airway: diagnosis and management. Int J Surg. 2016;28 Suppl 1:S75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park JS, Chang JW, Liu L, Jung SN, Koo BS. Clinical implications of microscopic extrathyroidal extension in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2017;72:183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czaja JM, McCaffrey TV. The surgical management of laryngotracheal invasion by well-differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123(5):484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsumori T, Nakao K, Miyata M, et al. Clinicopathologic study of thyroid carcinoma infiltrating the trachea. Cancer. 1985;56(12):2843–2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishihara T, Yamazaki S, Kobayashi K, et al. Resection of the trachea infiltrated by thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1982;195(4):496–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman M Surgical management of thyroid carcinoma with laryngotracheal invasion. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1990;23(3):495–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckham TH, Romesser PB, Groen AH, et al. Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy With or Without Concurrent Chemotherapy in Nonanaplastic Thyroid Cancer with Unresectable or Gross Residual Disease. Thyroid. 2018;28(9):1180–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chala AI, Velez S, Sanabria A. The role of laryngectomy in locally advanced thyroid carcinoma. Review of 16 cases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2018;38(2):109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaissert HA, Honings J, Grillo HC, et al. Segmental laryngotracheal and tracheal resection for invasive thyroid carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(6):1952–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KH, Sung MW, Chang KH, Kang BS. Therapeutic dilemmas in the management of thyroid cancer with laryngotracheal involvement. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(5):763–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballantyne AJ. Resections of the upper aerodigestive tract for locally invasive thyroid cancer. Am J Surg. 1994;168(6):636–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brauckhoff M Classification of aerodigestive tract invasion from thyroid cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014;399(2):209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarty TM, Kuhn JA, Williams WL Jr., et al. Surgical management of thyroid cancer invading the airway. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4(5):403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCaffrey TV, Lipton RJ. Thyroid carcinoma invading the upper aerodigestive system. Laryngoscope. 1990;100(8):824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu XF, Li ZJ, Wang X, Tang PZ. [The management and prognosis of laryngotracheal invasion by well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2004;84(22):1888–1891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honings J, Stephen AE, Marres HA, Gaissert HA. The management of thyroid carcinoma invading the larynx or trachea. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(4):682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai YF, Tseng YL, Wu MH, Hung CJ, Lai WW, Lin MY. Aggressive resection of the airway invaded by thyroid carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2005;92(11):1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segal K, Abraham A, Levy R, Schindel J. Carcinomas of the thyroid gland invading larynx and trachea. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1984;9(1):21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillenwater AM, Goepfert H. Surgical management of laryngotracheal and esophageal involvement by locally advanced thyroid cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 1999;16(1):19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park CS, Suh KW, Min JS. Cartilage-shaving procedure for the control of tracheal cartilage invasion by thyroid carcinoma. Head Neck. 1993;15(4):289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenvatinib in Locally Advanced Invasive Thyroid Cancer. 2020; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04321954, 4/23/2020.

- 25.Segal K, Shpitzer T, Hazan A, Bachar G, Marshak G, Popovtzer A. Invasive well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma: effect of treatment modalities on outcome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(5):819–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birkeland AC, Beesley L, Bellile E, et al. Predictors of survival after total laryngectomy for recurrent/persistent laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2017;39(12):2512–2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grover S, Swisher-McClure S, Mitra N, et al. Total Laryngectomy Versus Larynx Preservation for T4a Larynx Cancer: Patterns of Care and Survival Outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92(3):594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sayles M, Grant DG. Preventing pharyngo-cutaneous fistula in total laryngectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(5):1150–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito Y, Masuoka H, Fukushima M, et al. Prognosis and prognostic factors of patients with papillary carcinoma showing distant metastasis at surgery (M1 patients) in Japan. Endocr J. 2010;57(6):523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grillo HC, Suen HC, Mathisen DJ, Wain JC. Resectional management of thyroid carcinoma invading the airway. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54(1):3–9; discussion 9-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smallridge RC, Ain KB, Asa SL, et al. American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2012;22(11):1104–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cabanillas ME, Ferrarotto R, Garden AS, et al. Neoadjuvant BRAF- and Immune-Directed Therapy for Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. Thyroid. 2018;28(7):945–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]