Abstract

Bone cells must constantly respond to hormonal and mechanical cues to change gene expression programs. Of the myriad of epigenomic mechanisms used by cells to dynamically alter cell type-specific gene expression, histone acetylation and deacetylation has received intense focus over the past two decades. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) represent a large family of proteins with a conserved deacetylase domain first described to deacetylate lysine residues on histone tails. It is now appreciated that multiple classes of HDACs exist, some of which are clearly misnamed in that acetylated lysine residues on histone tails is not the major function of their deacetylase domain. Here, we will review the roles of proteins bearing deacetylase domains in bone cells, focusing on current genetic evidence for each individual HDAC gene. While class I HDACs are nuclear proteins whose primary role is to deacetylate histones, class IIa and class III HDACs serve other important cellular functions. Detailed knowledge of the roles of individual HDACs in bone development and remodeling will set the stage for future efforts to specifically target individual HDAC family members in the treatment of skeletal diseases such as osteoporosis.

INTRODUCTION

“Epigenetics” refers to structural chromatin changes that do not alter the genomic DNA sequence. Epigenetic information controls the active and silent states of gene expression during different biological processes in both prenatal and postnatal development. Within cells, there are four major epigenetic systems: chromatin remodeling, DNA methylation, histone modifications, and the expression of non-coding RNA species [1].

DNA is packaged into chromatin in cells [2]. As the core of chromatin, the nucleosome is composed of 147bp DNA wrapped around a histone octamer (H3, H4, H2A, H2B) [3]. The N-terminal tails of histones are the major targets of histone modifications. There are at least 8 distinct types of modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, sumoylation, ADP ribosylation, deamination, and protein isomerization, at over 60 different histone residues [4, 5]. Histone modification is reversible, with distinct histone modifying enzymes responsible for adding or removing specific histone modifications.

As a major histone post-translational modification (PTM), acetylation is regulated by the opposing activities of lysine acetyltransferases (KATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [6–8]. There are two characterized function for histone acetylation. First, acetylation of specific lysine residues can neutralize the positive charge of histone tails in order to unwind the condensed DNA-histone interactions and disrupt the histone-histone contacts [9]. Second, the acetylation signal is recognized by bromodomains of non-histone proteins [10]. Recruitment of nonhistone proteins could drive chromatin remodeling or affect higher-order chromatin structure that results in the activation of gene transcription [11–13].

Conversely, HDACs, by removing acetyl groups from histones, stimulate the formation of transcriptionally repressed chromatin structure and lead to gene expression changes [8]. HDACs are critical in maintaining a dynamic balance of acetylation by opposing the functions of KATs. Importantly, both KATs and HDACs can exert effects on gene expression by deacetylating non-histone proteins. Abnormal HDACs have been reported to play important roles in many human diseases including cancer, neurological disease, inflammatory and immune disorder, metabolic syndrome, cardiac disorder and pulmonary disease [14, 15].

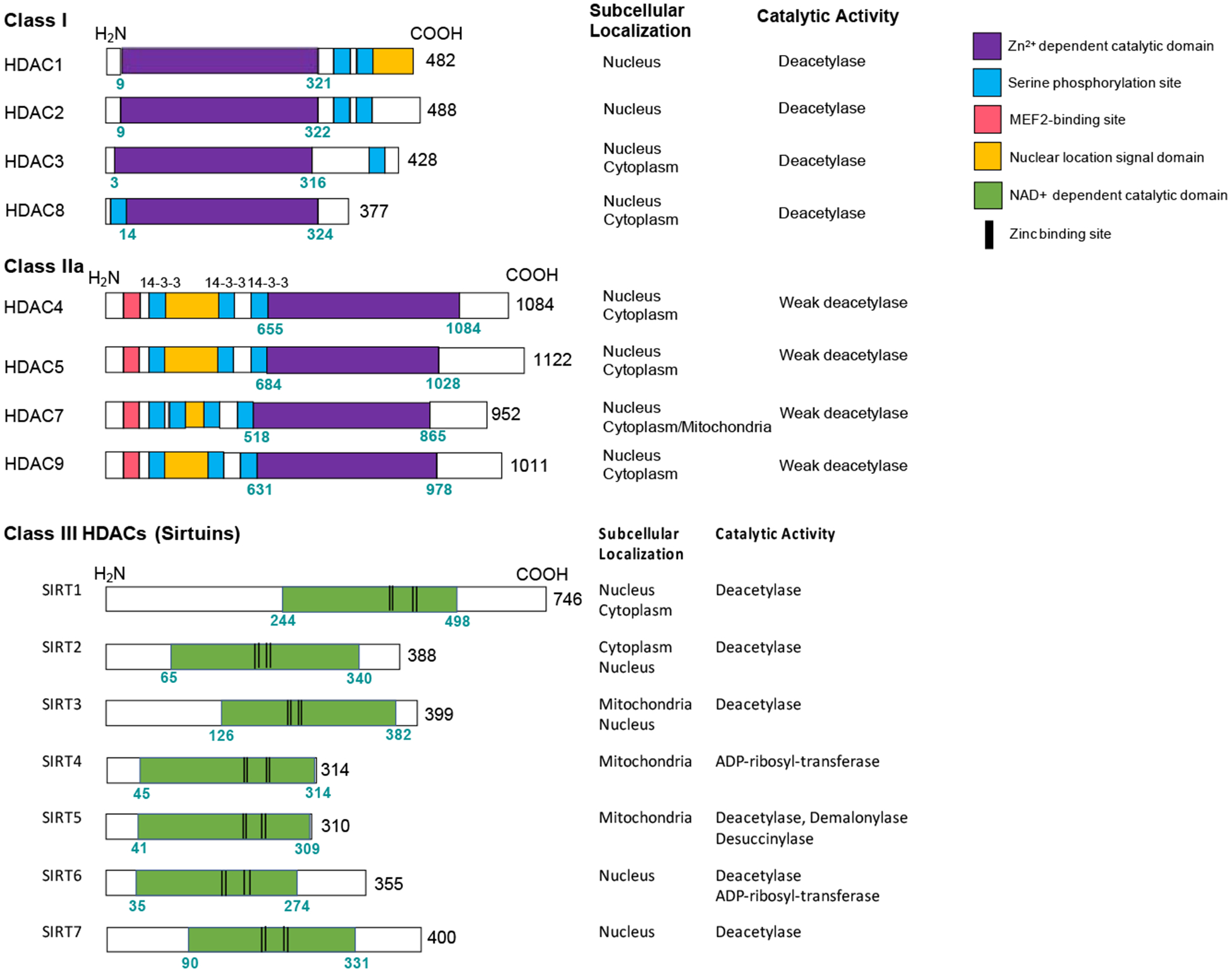

Bone is a dynamic endocrine organ that undergoes remodeling throughout life. Bone homeostasis is mainly controlled by the activity of osteoblasts (bone formation) and osteoclasts (bone resorption) [16]. Many human bone diseases are caused by the imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation [17, 18]. In this review, we focus on HDACs in bone development and remodeling. We will focus on three main classes of HDACs: class I HDACs, class IIa HDACs, and class III HDACs (Figure 1). As evident below, each class of HDACs bears distinct intracellular functions and roles in skeletal biology. A detailed understanding of how each distinct class of deacetylase domain-containing proteins functions in bone will be crucial to understand how bone cells control cell type-specific gene expression in response to physiologically-important external cues. Moreover, appreciating key differences between classes of HDACs will be vital in considering therapeutic applications of compounds that inhibit these enzymes.

Figure 1.

Overview of domain structure, subcellular localization, and catalytic activity for the HDAC subclasses reviewed here.

CLASS I HDACs

Identification of classes of HDACs

HDACs were initially identified in yeast [19]. 18 different mammalian HDACs have been identified and divided into four classes (class IIb HDACs will not be reviewed here as these are poorly-studied in bone at present) based on their similarity in sequence, structure and function. Known class I HDAC members are HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3 and HDAC8. They have high sequence identity and structure similarity to their prototype protein Rpd3 in S.cerevisiae [20, 21]. Class II and III HDACs have sequence similarity to the yeast Hda1 and Sir2 protein respectively [8]. Rpd3 regulates genes that are involved in cell cycle, which is much different from Hda1 and Sir2 that are involved in amino acid biosynthesis. Rpd3 and Hda1 regulate distinct acetylation patterns in the yeast genome, as evidenced by performing chromatin immunoprecipitation using the acetylation-site-specific antibodies [22].

Cellular mechanisms controlling class I HDAC activity

Class I HDACs are ubiquitously-expressed nuclear enzymes. They have relatively simple structure including a deacetylase domain plus short amino- and carboxy terminal extensions. Except for HDAC8, class I HDACs are components of multiprotein complexes. They are recruited to chromatin by transcription factors and other proteins since class I HDACs cannot bind to DNA directly [8]. HDAC1 and HDAC2 are mainly found together in similar repressive complexes including Sin3, NuRD (nucleosome-remodeling HDAC), CoREST (RE1 silencing transcription factor), PRC2 and MiDAC (mitotic cells specific HDAC) [23]. HDAC3 has a distinct function than HDAC1/2 and it interacts with NCoR-SMRT co-repressor complexes [24]. HDAC8 was the last member of Class I HDACs to be cloned and no direct association between HDAC8 to co-repressor complexes has reported [25].

Based on the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project of human, HDAC1 has the highest expression level in thyroid. HDAC2 and HDAC3 are mostly expressed in testis and skin. In RNA-sequencing studies, there is a great variability in expression of HDACs in adult human bone and articular cartilage. HDAC1 and HDAC3 are the most abundant HDACs in both tissues. HDAC2 has a much higher expression in normal human articular cartilage [26].

Role of class I HDACs in bone

Mammalian bones are formed through two different processes. Most bones develop via endochondral ossification with a cartilage template as the intermediate. The molecular basis for the key steps of endochondral ossification has been well studied. Many transcription factors are indispensable for endochondral ossification, such as Sox9, Runx2 and Sp7. Sox9 is the transcription factor that belongs to the SRY-related high mobility group box family. Sox9 is essential for chondrocyte differentiation in collaboration with two other Sox proteins (Sox5 and Sox6) [27]. Runx2 plays crucial roles in both chondrocyte hypertrophy and osteoblast differentiation [28–31]. Ablation of Runx2 in mice results in the complete lack of hypertrophic chondrocytes and osteoblasts. Osterix/Sp7 (encoded by the Sp7 gene) is a zinc finger-containing transcription factor that has been studied intensively by skeletal biologists due to its vital role in osteoblasts. Osteoblast differentiation is arrested, and no bone formation occurs in Sp7 null mice [32]. Sp7 expression is abolished in Runx2−/− mice while Runx2 expression remains the same in Sp7−/− mice. These results suggest that Sp7 acts downstream of Runx2 in osteoblast differentiation. Some craniofacial bones develop via intramembranous ossification and are formed directly from mesenchymal cells without a cartilaginous intermediate. These cells differentiate into matrix-producing osteoblasts and then form into mineralized bone by secreting Col1a1 and proteoglycans [33]. This commitment requires the transcription factors Runx2 and Osterix (Osx/Sp7) to promote osteoblast differentiation [32]. As discussed next, many class I HDACs contribute to various steps of the endochondral ossification and the intramembranous processes.

HDAC1

Hdac1 expression is decreased during osteoblast differentiation. In vitro knockdown of Hdac1 or pharmacologic inhibition of Hdac1 with relatively-specific Hdac1 inhibitors in different cell types leads to increased ALP activity and osteogenic-related gene expression levels [34, 35]. Hdac1 is recruited to the promoters of Osx/Sp7 and Ocn to suppress expression of these osteoblast-specific genes. These in vitro data suggest that Hdac1 plays a role to suppress osteoblast differentiation both in intramembranous and endochondral ossification, and the inhibition of Hdac1 stimulates osteogenesis in cell systems.

In mice, germline deletion of Hdac1 leads to embryonic lethality prior to E10.5 [36]. The function of Hdac1 in postnatal skeletal development remains unknown, and there has no conditional KO of Hdac1 models being reported. Based on the current prenatal animal models, Hdac1 is involved in the formation of cartilage and extracellular matrix (ECM) during endochondral ossification [37–41]. See Table 1 for a summary of mutant phenotypes seen in all germline and conditional Hdac mutant models. Hdac1 can associate with the transcription repressor Nkx3.2 to inhibit chondrogenesis [37, 38]. Hdac1 can also repress the expression of several cartilage ECM genes, such as collagen type 2 and aggrecan [39–41].

Table 1.

Mouse models of Hdac deficiency with reported skeletal phenotypes

| Hdac | Mouse Genetic Alteration | Skeletal phenotypes |

|---|---|---|

| Hdac1 | KO | Embryonic lethality prior to E10.5 [36] |

| Hdac2 | KO | Most mice die before birth. Reduced body size and long bone length in surviving Hdac2−/− [43] |

| Hdac3 | KO | Embryonic lethality prior to E9.5 [44] |

| Hdac3 | Neural crest cell-specific deletion (Wnt-Cre; Hdac3flox/flox; Pax3-Cre; Hdac3flox/flox) | Severe craniofacial defects including microcephaly and nearly absent frontal bone formation [45, 46] |

| Hdac3 | Osteo-progenitor-specific deletion (Sp7-Cre; Hdac3flox/flox) | Homozygous mice show small body size, craniofacial abnormalities, growth plate defects, decreased trabecular and cortical bone density [47] |

| Hdac3 | Chondrocyte and osteo- chondroprogenitor-specific deletion (Col2a1-Cre; Hdac3flox/flox) | Embryonic lethality [48] |

| Hdac3 | Postnatal chondrocyte and osteo-chondroprogenitor- specific deletion (Col2a1-CreER; Hdac3flox/flox) | Delayed endochondral ossification, elevated Mmp13 abundance, and reduced cancellous bone density [49] |

| Hdac3 | Mature osteoblast and osteocyte-specific deletion (Ocn-Cre; Hdac3flox/flox) | Decreased bone mineralization, loss of trabecular and cortical bone mass with aging [50] |

| Hdac4 | KO | Perinatal lethality with accelerated chondrocyte hypertrophy and early endochondral bone formation [84] |

| Hdac4 | Chondrocyte and osteo- chondroprogenitor-specific deletion (Col2a1-Cre; Hdac4flox/flox) | Perinatal lethality with accelerated rib chondrocyte hypertrophy [89] |

| Hdac4 | Osteoblast-specific deletion (Col1a1-Cre; Hdac4flox/flox) | Short limbs and mild osteopenia [91] |

| Hdac4 | Osteoblast-specific deletion (Runx2-Cre; Hdac4flox/flox) | Short limbs and mild osteopenia [92] |

| Hdac4 | Mature osteoblast and osteocyte-specific deletion (Dmp1-Cre; Hdac4flox/flox) | No obvious skeletal phenotype [94] |

| Hdac5 | KO | Mild osteopenia [63, 92] |

| Hdac4/5 | Germline Hdac5 KO and mature osteoblast and osteocyte-specific deletion of Hdac4 (Hdac5−/−; Dmp1-Cre; Hdac4flox/flox) | Cortical osteopenia with woven bone and increased osteocyte density, defective responses to loading [94, 120] |

| Hdac7 | KO | Embryonic lethality prior to E11 [101] |

| Hdac7 | Chondrocyte and osteo-chondroprogenitor-specific deletion (Col2a1-Cre; Hdac7flox/flox) | Partially penetrant lethality [102] |

| Hdac7 | Postnatal chondrocyte and osteo-chondroprogenitor- specific deletion (Col2a1-CreER; Hdac7flox/flox) | Increased chondrocyte proliferation and expanded proliferative zone in the growth plate [102] |

| Hdac7 | Osteoclast-specific deletion (LysM-Cre; Hdac7flox/flox) | Osteopenia associated with increased osteoclast numbers and activity [103] |

| Hdac8 | KO | Homozygous mice died at P4–6 with movement deficiency and hypoxia [51] |

| Hdac8 | Neural crest cell-specific deletion (Wnt-Cre; Hdac8flox/flox) | Impaired skull development with ossification defects [51] |

| Hdac8 | Chondrocyte and osteo-chondroprogenitor-specific deletion (Col2a1-Cre; Hdac8flox/flox) | No obvious skeletal phenotype [51] |

| Hdac8 | Osteoblast-specific deletion (Col1a1-Cre; Hdac8flox/flox) | No obvious skeletal phenotype [51] |

| Hdac9 | KO | Trabecular and cortical osteopenia associated with increased bone resorption at 3-month-old KO mice [67] |

| Sirt1 | KO | Death around 1 month of age on the inbred 129/Sv background Better survival but smaller in body size on mixed CD1 and 129/Sv background [125] |

| Sirt1 | KO | Under-mineralized bone during development, and skull suture defect at 6 weeks of age. Smaller body size [126] |

| Sirt1 | Chondrocyte and osteo-chondroprogenitor-specific deletion (Col2a1-Cre; Sirt1flox/flox) | Short bone and body length, narrow growth plate with impaired chondrocyte proliferation and increased apoptosis [127] |

| Sirt1 | Mesenchymal progenitor specific deletion (Prx1-Cre; Sirt1flox/flox) | Cortical and trabecular bone loss at 2.2 years of age, with decreased bone formation rate and osteoblast number, no significant difference at 2 months of age except for decreased trabecular thickness [129] |

| Sirt1 | KO | Greater loss in bone volume in 4-month-old global KO mice compared to 1-month-old KO mice [131] |

| Sirt1 | Osteoclast-specific deletion (LysM-Cre; Sirt1flox/flox) | Greater loss in bone volume at 4 months of age compared to 1-month-old KO mice [131] |

| Sirt1 | Osteoblast-specific deletion (Col1a1-Cre; Sirt1flox/flox) | Reduced bone mass at 4 months of age, but no significant effect at 1 month of age [131] |

| Sirt1 | Osteoclast-specific deletion (LysM-Cre; Sirt1flox/flox) | Reduced trabecular bone mass with increased osteoclast numbers [132] |

| Sirt1 | Osteoblast-specific deletion (Col1a1-Cre; Sirt1flox/flox) | Reduced trabecular bone mass with decreased osteoblast number [132] |

| Sirt1 | Osteo-progenitor-specific deletion (Sp7-Cre; Sirt1flox/flox) | Cortical bone loss with decreased endocortical bone formation rate at 12 weeks of age, no change in trabecular bone [133] |

| Sirt1 | Sir1+/− | 12-week-old females show osteopenia in trabecular bone with decreased bone formation rate (although no change in osteoblast number) while male mice were not significantly affected [134] |

| Sirt1 | Inducible deletion (Cre-ERT2; Sirt1flox/flox) | Reduced cortical bone thickness [135] |

| Sirt1 | Transgenic (Prx1 promoter) | Increased body weight and increased bone length at 4 weeks of age. Increased trabecular bone mass with increased osteoblasts and decreased osteoclast numbers [136] |

| Sirt3 | KO | Decreased trabecular bone mass with increased osteoclasts without changes in osteoblast number [172] |

| Sirt3 | Transgenic (actin promoter) | Cortical and trabecular bone loss with increased bone marrow adipocytes and osteoclasts (13-month old); no significant phenotype at 3 months of age [174] |

| Sirt3 | KO | Reduced trabecular bone mass with changes in serum parameters consistent with increased bone resorption and reduced bone formation [175] |

| Sirt6 | KO | Small body size at birth, death at ~3 weeks of age Osteopenia and lordokyphosis at 3.5 weeks of age [181] |

| Sirt6 | KO | Short bones, impaired chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation in 2-week old KO mice [184] |

| Sirt6 | KO | Cortical and trabecular bone loss with decreased bone turnover at 3 weeks of age [186] |

| Sirt6 | KO | Low body weight, reduced cartilage and mineralized bone at 3 weeks. Cortical and trabecular bone loss. Decreased bone formation and increased bone resorption. [187] |

| Sirt6 | KO | Dwarfism with reduced cartilage and mineralized bone at 3 weeks. Trabecular bone loss in vertebrae and long bones with increased osteoclasts [192] |

| Sirt6 | Osteoclast precursor specific deletion (Mx1-Cre; Sirt6flox/flox) | Increased trabecular bone mass with decreased osteoclasts [193] |

| Sirt7 | KO | Cortical and trabecular osteopenia with decreased bone formation rate in 14–15-week-old KO mice [197] |

| Sirt7 | Osteoblast specific deletion (Col1a1-Cre; Sirt7flox/flox) | Cortical and trabecular osteopenia with decreased bone formation at 15 weeks of age [197] |

HDAC2

Hdac1 and Hdac2 are highly homologous and they share many redundant functions. The role of Hdac2 in intramembranous ossification has not been reported. However, defective craniofacial development is seen in rare human syndromes due to HDAC2 mutations [42]. See Table 2 for a summary of human skeletal phenotypes associated with HDAC gene mutations and variants. These patients show thoracic scoliosis and vertebral rotation. More in-depth analyses are needed to uncover the mechanisms of HDAC2 during craniofacial bone development. Most of Hdac2 knockout mice die before birth. Surviving Hdac2−/− pups show reduced body size and reduced long bone length [43]. One potential explanation is that Hdac2 could suppress growth plate development during endochondral ossification process, though additional studies with germline and conditional Hdac2 mutant mice are needed to clarify the role of this class I HDAC in bone development.

Table 2.

Human models of HDAC mutations and reported skeletal phenotypes

| HDAC | Mutations | Skeletal phenotypes |

|---|---|---|

| HDAC2 | Deletion of several genes including HDAC2 | Defective craniofacial development (thoracic scoliosis and vertebral rotation) and limb abnormalities [42] |

| HDAC4 | Haplo-insufficient microdeletions within HDAC4 | Skeletal abnormalities including brachydactyly, shorter metatarsals and metacarpals [87] |

| HDAC5 | SNP located 8 kb upstream of HDAC5 | Low bone mineral density in lumbar spine and femoral neck [99] |

| HDAC8 | Loss of function mutations within HDAC8 locus | Distinctive craniofacial defects (delayed fontanel closure), small hands, small feet and short stature [53–56] |

| HDAC9 | SNP located within HDAC9 | Associated with calcification of the abdominal aorta [106] |

| SIRT1 | Decreased expression of SIRT1 at femoral neck of osteoporotic patients compared to osteoarthritic patients [163] | |

| SIRT1 | SIRT1 polymorphisms | Common SIRT1 polymorphisms were associated with BMI, but not BMD [164] |

| SIRT6 | Homozygous, inactivating SIRT6 mutation at position 187 (G to C) | Prenatal abnormalities, including intrauterine growth restriction and craniofacial abnormalities (death between 17–35 weeks of gestation) [183] |

HDAC3

Unlike Hdac1 and Hdac2, the role of Hdac3 in bone development has been well-studied through the use of conditional Hdac3 mutant mice. Global knockout of Hdac3 results in embryonic lethality [44]. In order to examine the role of Hdac3 in postnatal mice, Wnt1-Cre, Pax3-Cre, Prrx1-Cre, Col2a1-Cre, Col2a1-CreER, Sp7-Cre and Ocn-Cre have all been employed. Through these approaches, it has been demonstrated that Hdac3 is an essential regulator during intramembranous and endochondral ossification. Deletion of Hdac3 in migratory neural crest cells (NCCs) using Wnt-Cre and Pax3-Cre causes severe craniofacial defects, including microcephaly and almost no frontal bone formation [45, 46]. When deleted in osteo-progenitors with Sp7-Cre, Hdac3 mutants show craniofacial abnormalities and decreased cranial bone density [47]. However, significant long bone abnormalities are observed in Hdac3 cKO (Sp7- Cre) mice including short bones, low trabecular and cortical bone density, as well as reduced number of osteoblasts. Deletion of Hdac3 in chondrocytes and osteo-chondroprogenitors with Col2a1-Cre also results in embryonic lethality [48]. This suggests that Hdac3 is required for normal chondrocyte maturation. To overcome the barrier of embryonic lethality, postnatal deletion of Hdac3 in chondrocytes was assessed with tamoxifen inducible Col2a1-CreER [49]. Compared to control mice, these knockout mice have increased circulating Il-6, elevated Mmp13 abundance and reduced cancellous bone density. This supports the role of Hdac3 in extracellular matrix remodeling during chondrocyte maturation. Deletion of Hdac3 in mature osteoblasts and osteocytes using Ocn-Cre does not affect body size but causes decreased bone mineralization, and loss of trabecular and cortical bone mass with age [50]. Taken together, these findings demonstrate an important role for Hdac3 in mesenchymal cells in bone. Future studies are needed to define the molecular mechanisms used by Hdac3 to control distinct gene expression patterns in bone cells.

HDAC8

As the ‘new’ member of class I HDACs, Hdac8 was first examined in vitro. Inhibiting Hdac8 with valproic acid (VPA, not a selective Hdac8 inhibitor) in bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) leads to increased expression of osteogenic genes by maintaining the acetylation of H3K9 [51]. As for in vivo studies, both global and conditional Hdac8 knockout mice showed severe cranial skeletal defects [52]. Hdac8 null mice usually died 4–6 days after birth with movement deficiency and hypoxia. A wide foramen frontale and a distinct ossification defect of the interparietal bone were found in Hdac8−/− mice. Moreover, conditional deletion of Hdac8 with Wnt1-Cre resulted in the impairment in skull development by reducing the expression level of Otx2 and Lhx1 transcriptional factors [52]. HDAC8 loss-of-function mutations were identified in patients with Cornelia de Lange Syndrome 5 and Wilson-Turner X-linked Mental Retardation Syndrome [53–56]. Consistent with craniofacial impairments seen in Hdac8 knockout mice, all these patients have distinctive craniofacial defects, such as delayed fontanel closure. Surprisingly, patients also have small hands and feet, as well as short stature though no long bone abnormalities were discovered in Hdac8 cKO mice. To date, there is no evidence supporting the role of Hdac8 in endochondral ossification. Conditional deletion of Hdac8 with Col2-Cre and Col1a1-Cre in mice has no effect on long bone phenotypes [52].

Knowledge gaps related to the role of class I HDACs in osteocytes and osteoclasts

Osteocytes, the most abundant cell type in bone, control bone remodeling by secreting paracrine-acting factors that regulate osteoblast and osteoclast activity [57]. Osteocytes act as key regulators during osteoclast resorption by producing RANKL [58, 59]. In addition, osteocytes can also regulate bone formation by secreting sclerostin (encoded by Sost) which inhibits osteoblast differentiation and activity [60, 61]. Few studies have attempted to examine the role of class I HDACs in osteocytes. Inhibition of Hdac1, 2 and 3 with siRNA in osteocyte-like UMR106 cells results in a dramatic reduction of Sost expression [62]. Hdac3 may also function as a corepressor recruited by Hdac5 and suppress Sost expression in other osteocyte-like cell lines [63]. Future studies are needed to clarify the role of class I HDACs in osteocyte biology, and to define the relationship between class I and IIa HDACs (see below) in bone cells.

Osteoclasts are large, multinucleated cells of hematopoietic origin. They are the primary resorptive cells that degrade bone matrix [64]. Macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) are necessary for osteoclast differentiation [65, 66]. These two factors are secreted by osteoblasts and osteocytes, and are required for the induction of osteoclast-specific genes, including tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase and cathepsin K. The role of HDACs in osteoclasts are not as widely examined as they are in osteoblasts; however, this is an emerging area of scientific interest.

There are no published mouse models investigating the role of class I HDACs in osteoclast development or function. Hdac1 is expressed in osteoclast precursors but not in mature osteoclasts [67]. The reported function of Hdac1 is to serve as a transcriptional corepressor by localizing the promoters of osteoclast genes, such as Nfatc1, Oscar, Ctsk and Acp5 [68]. Both Hdac2 and Hdac3 have shown evidence of promoting osteoclast differentiation in cells [69, 70]. Knockdown of Hdac3 in bone marrow-derived osteoclasts exhibited inhibition of osteoclast formation and down-regelation of osteoclast-specific genes, including Nfatc1 and Ctsk [70]. To date, little is known about Hdac8 in osteoclasts other than the observation that Hdac8 shows increased expression during osteoclast differentiation [67].

Pharmacologic class I HDAC inhibitors

HDAC inhibitors are natural or synthetic derived small molecules that block the enzymatic activity. Most of the HDAC inhibitors could be divided into short-chain fatty acids, hydroxamic acids, carboxylates, benzamides, electrophilic ketones and cyclic peptides [71]. To date, most progress is made on non-specific HDACi compounds (pan-HDACis), which work equally against different classes of HDACs. Recently research has begun to focus on HDAC-selective inhibitors, which are preferential inhibitors of one class over the other [72]. Commonly used pan-HDACi are sodium butyrate, valproic acid, Trichostatin A (TSA) and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA or Vorinostat). Romidepsin and Entinostat (MS-275) are class I HDAC selective inhibitors.

As in osteoblasts, there have been many in vitro studies reporting the effects of pan-HDACi during bone formation. TSA, Valproate and sodium butyrate all up-regulate Runx2 transcription activity, induce osteoblast gene expression and alkaline phosphatase production (ALP) [35, 73, 74]. Class I HDACi MS-275 enhances osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells by accelerating cell proliferation and ALP production [35]. Another selective class I HDACi, Largazole, was found to promote osteogenesis in C2C12 cells by increasing the expression of Runx2 and several osteogenic markers [75]. Moving to osteoclasts, many pan-HDACis including TSA, sodium butyrate and 1179.4b, have demonstrated the ability of repression osteoclast differentiation and maturation in vitro [76, 77]. A few studies have reported that class I HDAC inhibitors can suppress the formation of TRAP positive osteoclasts and their ability of bone resorption including MS-275 and NW-21 [76, 78]. Another Hdac1 and 2 specific inhibitor, Romidepsin, represses osteoclast differentiation by inducing the expression of interferonβ, which is an osteoclast inhibitory factor [79]. Future studies that define the roles of Hdac1 and Hdac2 in bone cells in vivo will be helpful in developing a predictive model to understand effects seen with compounds that inhibit all class I HDAC isoforms.

CLASS IIA HDACS

Introduction

Proteins in the class IIa HDAC subfamily (HDAC4, 5, 7, and 9) all possess three distinct features that distinguish them from class I HDACs [80]. First, unlike class I HDACs, class IIa HDACs all bear long N-terminal extensions which allow them to sense and transduce signaling information and interact with specific nuclear transcription factors. Importantly, phospho-acceptor serine residues in this extension allow for dynamic changes 14-3-3 binding [81]. In general, when class IIa HDACs are phosphorylated in this region, these proteins are retained in the cytoplasm due to binding to 14-3-3 chaperones. In contrast, nuclear class IIa HDAC localization is noted when these sites are not phosphorylated. Therefore, upstream signals that regulate class IIa HDAC phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycles may a crucial role in dictating the subcellular localization and cellular activity of these nucleocytoplasmic shuttling factors. An additional key feature of the N-terminal extension of class IIa HDACs is a protein-protein interaction motif that allows these proteins to bind and MEF2 family transcription factors [80]. Therefore, a model has emerged in which class IIa HDACs serve as signal dependent regulators of MEF2-driven gene expression.

Second, all class IIa HDACs bear a histidine residue at a key position in the DHY catalytic triad seen in class I histone deacetylases. This tyrosine-to-histidine substitution dramatically decreases the deacetylase activity of class IIa HDACs towards acetylated histones [82]. As such, it is likely that class IIa HDACs are misnamed as their primary role is not necessarily to deacetylate lysine residues on histone tails. Rather, it is possible that the deacetylase domain of class IIa HDACs is used to bind acetylated histones and recruit multimeric complexes to specific genomic sites to regulate gene expression [83].

Third, class IIa HDACs contain a nuclear export signal in the C-terminal portion of their crippled deacetylase domain. Taken together, these three distinct features of class IIa HDACs suggest that these proteins are well-adapted to function as signaling proteins to translate information from external cues to regulating stimulus-dependent gene expression patterns. Indeed, examples abound in non-skeletal tissues such as muscle, liver, heart, endothelium, and neurons where class IIa HDACs control dynamic gene expression patterns in response to physiologic and pathophysiologic cues. Here, we will review the skeletal phenotypes present in mice lacking class IIa HDACs in bone, and review current knowledge and unanswered questions regarding mechanisms used to control class IIa HDAC subcellular localization in bone cells.

HDAC4

Multiple important roles for Hdac4 in bone have been reported since the initial description of accelerated growth plate hypertrophy in Hdac4-deficient mice in 2004 [84]. Mice with germline null Hdac4 mutations show perinatal lethality due to accelerated chondrocyte hypertrophy and early endochondral bone formation. In growth plate chondrocytes, Hdac4 suppresses the activity of Runx2 [84] and Mef2c [85], two key transcription factors that orchestrate the hypertrophic gene expression program. The Runx2 target gene Mmp13, which is overexpressed in Hdac4-deficient mice, plays an important role in the phenotype of Hdac4 mutants, as evidenced by partial rescue of the Hdac4-null phenotype with compound loss of Mmp13 [86]. Humans who are haplo-insufficient for HDAC4 due to 2q37 microdeletions show brachydactyly, a skeletal phenotype largely consistent with mice that are homozygous null for this gene [87]. Interestingly, a separate Hdac4 mutant mouse strain in which the N-terminus of the protein is preserved but the deacetylase domain is completely lacking does not shows completely normal bone development [88], indicating that the N-terminal Mef2 binding region of Hdac4 is needed for its function in the growth plate, while the deacetylase function of Hdac4 is not required for its role in blocking chondrocyte hypertrophy.

Skeletal cell-type specific Hdac4 deletion has been reported by multiple groups. Chondrocyte-specific Hdac4 deletion fully recapitulates the phenotype seen with global Hdac4 deficiency, including perinatal lethality due to accelerated rib chondrocyte hypertrophy and consequent respiratory insufficiency [89]. Analysis of mice lacking Hdac4 in osteoblasts is complicated by promiscuous expression of some ‘osteoblast-specific’ Cre drivers in terminal hypertrophic chondrocytes [90]. Col1a1-Cre and Runx2-Cre driven deletion of Hdac4 both lead to short limbs and mild osteopenia [91, 92]. In contrast to Col1a1-Cre, Dmp1-Cre (9.6 kB promoter fragment) is not active in growth plate chondrocytes, but does effectively target most mature osteoblasts and osteocytes [93]. Deletion of Hdac4 alone with Dmp1-Cre leads to no obvious skeletal phenotype, although mice lacking both Hdac4 and Hdac5 show dramatic osteopenia, abnormal osteocyte numbers, and increased expression of the Mef2c target gene Sost [94]. To date, no in vivo genetic evidence exists regarding a potential cell intrinsic role for Hdac4 in osteoclasts.

HDAC5

Amongst class IIa HDAC subfamily members, Hdac4 and Hdac5 are most closely related. Indeed, the two proteins heterodimerize [95] and show related and compensatory functions in other tissue types [96]. Global Hdac5-deficient mice [97] show mild osteopenia [92], a phenotype associated with increased Mef2c-driven Sost expression [63]. Sost encodes for sclerostin, an osteocyte-enriched secreted protein that inhibits Wnt-driven osteoblastic bone formation in a paracrine manner [98]. In humans, common intronic HDAC5 variants have been linked to bone density through genome wide association studies [99]. To date, Hdac5 conditional knockout mice have not been reported, precluding the ability to conduct studies to address a potential cell-intrinsic role of Hdac5 in osteoclasts. As noted above, when global Hdac5-deficient mice are crossed to mice lacking Hdac4 selectively in mature osteoblasts and osteocytes, dramatic cortical osteopenia with woven bone is noted, a phenotype present in neither single mutant strain alone [94]. While Hdac5-deficient mice show no overt phenotypes with respect to bone length or growth plate histology, compound Hdac4/5 deficiency in growth plate chondrocytes leads to accelerated hypertrophy beyond what is observed in Hdac4- deficient animals [89]. Taken together, these genetic observations clearly demonstrate compensation between Hdac4 and Hdac5 in bone, both in chondrocytes and osteocytes.

HDAC7

Similar to Hdac4 and Hdac5, Hdac7 also has been reported to bind and inhibit Runx2 and Mef2 family transcription factors [100]. Germline Hdac7 deletion in mice leads to embryonic lethality at E11.0 due to widespread circulatory system defects [101]. In endothelial cells, Hdac7 plays an essential role in suppressing Mef2-driven Mmp10 production which is a key regulator of blood vessel development. In contrast to Hdac4 and Hdac5, tamoxifen-inducible deletion of Hdac7 in chondrocytes and osteo-chondroprogenitors led to increased chondrocyte proliferation and an expanded proliferative zone in the growth plate [102]. Interestingly, Hdac7 controls chondrocyte proliferation via interacting with another key transcription factor, β-catenin [102]. To date, the role of Hdac7 in osteoblasts and osteocytes has not been reported.

Unlike Hdac4 and Hdac5, the function of Hdac7 in osteoclasts has been studied. Conditional deletion of Hdac7 using LysM-Cre, a driver active in myeloid cells including osteoclast precursors, leads to enhanced osteoclast differentiation in vitro and osteopenia associated with increased osteoclast numbers and activity in vivo [103]. In osteoclasts, Hdac7 binds and inhibits the function of the transcription factor Mitf [104], a key determinant of M-CSF-dependent osteoclast survival [105]. Interestingly, Hdac7 blocks Mitf activity in osteoclasts through a deacetylase-independent manner [104], consistent with the aforementioned observations that Hdac4 functions in chondrocytes independently of its deacetylase domain.

HDAC9

Among class IIa HDAC family members, relatively less attention has been paid towards Hdac9 due to low expression of this gene in mesenchymal lineage bone cells such as chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and osteocytes. However, germline Hdac9 deficient mice at 3 months of age show trabecular and cortical osteopenia associated with increased bone resorption [67]. Use of bone marrow transplantation experiments demonstrates that this low bone mass phenotype maps to the hematopoietic compartment. Moreover, Hdac9 appears to regulate PPARg activity in osteoclasts [67]. However, the precise cell autonomous role of Hdac9 in osteoclasts remains to be determined through the use of osteoclast-specific conditional knockout mice. Recently, it was reported that human HDAC9 variants are linked to aortic calcification, and that Hdac9-deficient mice are resistant to vascular calcification [106]. Therefore, it will be of major interest to determine the relationship between the function of Hdac9 in cardiac fibroblasts which can undergo osteogenic differentiation in many pathologic states [107].

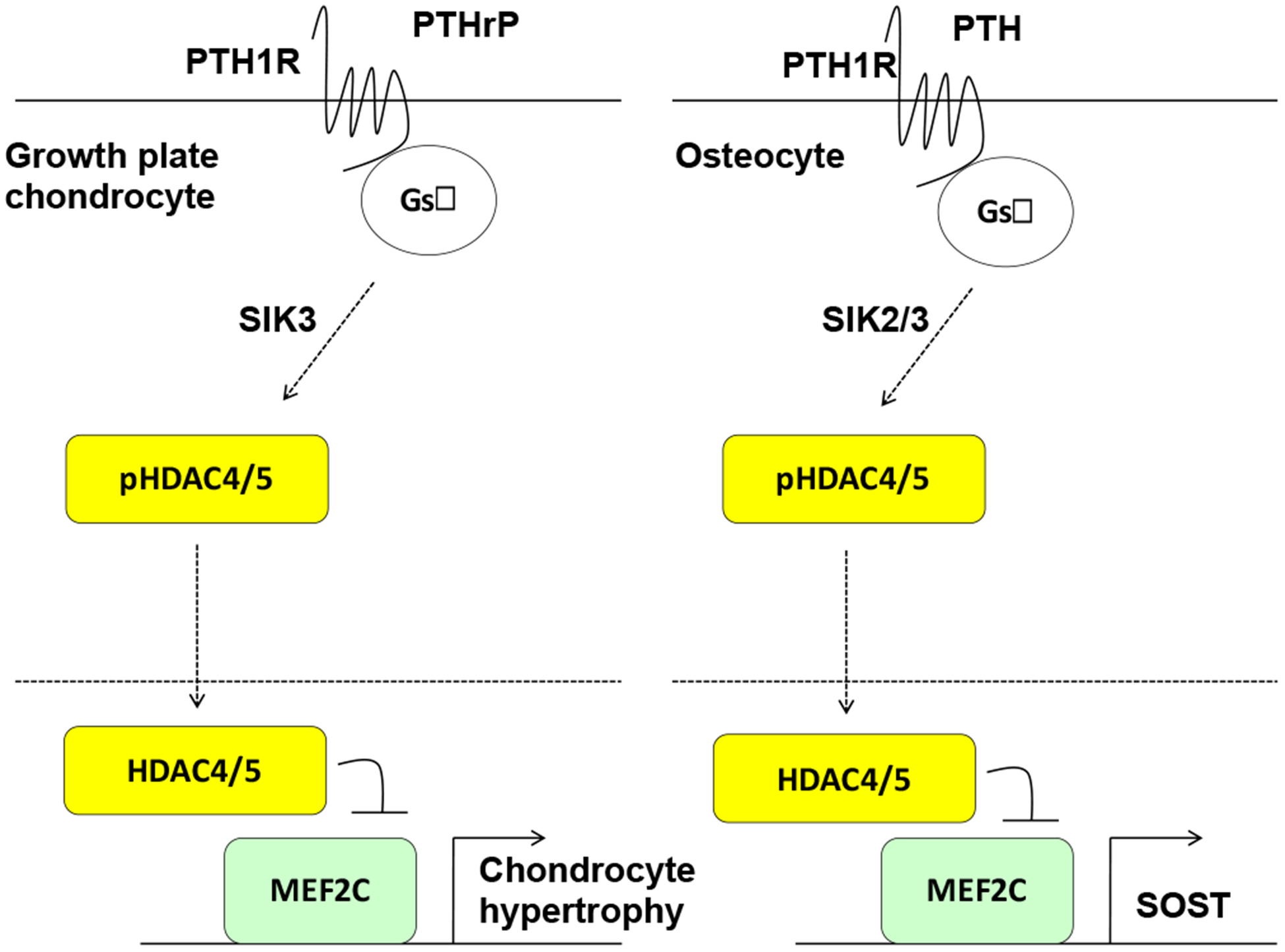

Upstream signaling to class IIa HDACs

Recently, the physiologically-relevant extracellular cues that trigger changes in class IIa HDAC subcellular localization in bone cells have been defined. In general, class IIa HDAC subcellular localization is governed by the balance between N-terminal extension phosphorylation, which promotes 14-3-3 binding and cytoplasmic retention, and dephosphorylation, which stimulates nuclear translocation [108]. Given the central role of HDAC4 and, to a lesser extent, HDAC5 in controlling MEF2-driven chondrocyte hypertrophy [84, 89], work has focused on identifying signals that regulate HDAC4/5 localization in chondrocytes.

The paracrine actions of parathyroid hormone related protein (PTHrP) suppress chondrocyte hypertrophy [109]. In chondrocytes, PTHrP signaling drives dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation of HDAC4 and HDAC5 [110]. Salt inducible kinases (SIKs) are a subclass of AMPK family kinases reported to function of class IIa HDAC kinases in other cells types [111]. Mice lacking Sik3 show delayed chondrocyte hypertrophy and increased nuclear Hdac4 staining [112]. Sik3 deficient mice display a growth plate phenotype highly reminiscent of animals overexpressing PTHrP [113], and PTHrP transgenic mice also show increased nuclear Hdac4 staining [89]. Moreover, humans with rare SIK3 mutations show a similar growth plate phenotype similar to what is observed with constitutively active PTH/PTHrP receptor expression in Jansen’s Metaphyseal Chondrodysplasia [114]. Remarkably, deletion of Hdac4 abrogates the growth plate phenotype seen in PTHrP transgenic mice [89], demonstrating that class IIa HDACs exist in the same genetic pathway as PTHrP signaling in the growth plate.

Work in many non-skeletal cell types has led towards a consensus mechanism linking cAMP signaling to regulation of SIK action [115, 116]. All three SIK isoforms bear consensus PKA sites in C-terminal extensions outside of their kinase domain. When these serine/threonine residues are phosphorylated by PKA, this creates a docking site for 14-3-3 chaperone proteins which trigger subcellular SIK redistribution to domains away from substrate proteins [117]. Therefore, the net effect of cAMP/PKA signaling is to inhibit SIK cellular activity through an allosteric mechanism. In osteocytes, parathyroid hormone (PTH) signaling triggers PKA-dependent SIK2 phosphorylation. PTH-dependent SIK2 inhibition leads to net reductions in HDAC4/5 phosphorylation and their nuclear translocation. Direct small molecule SIK inhibitors mimic the effects of PTH both in vitro and in vivo [94]. Therefore, SIK inhibition is a key action in the intracellular effects of PTH in osteocytes [118].

Insights into the role of SIKs downstream of PTH in osteocytes have been applied to understand the relationship between SIK3, class IIa HDACs, and PTHrP in the growth plate. PTHrP signaling in cultured chondrocytes triggers SIK3 phosphorylation at PKA sites. Genetic epistasis experiments demonstrate that class IIa HDACs are downstream of SIK3 in the growth plate: compound Sik3/Hdac4 mutants lack the expansion of proliferating chondrocytes seen in Sik3 mutant mice [119]. In addition, parallel epistasis studies demonstrate a similar model in osteoblasts and osteocytes. Deletion of both Sik2 and Sik3 using Dmp1-Cre leads to increased trabecular bone mass and high bone turnover, a phenotype with striking similarities to animals expressing an activating PTH receptor in osteoblasts and osteocytes. Strikingly, this Sik2/3 mutant phenotype is completely absent when Hdac4 and Hdac5 are simultaneously deleted [119]. Taken together, these genetic studies demonstrate the central importance of a signaling axis between PTH/PTHrP signaling, cAMP/PKA, SIKs, and class IIa HDACs in both growth plate chondrocytes and osteocytes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model demonstrating parallels between cAMP signaling via a SIK/class IIa HDAC axis in growth plate chondrocytes (left) and osteocytes (right).

Future studies are needed to determine if class IIa HDACs participate in the actions of PTH in other target tissues, and to develop an integrated model accounting for how multiple signaling inputs [92] impinge upon class IIa HDAC phosphorylation/ localization in target cells in bone. For example, recently it was demonstrated that dynamic changes in cell/matrix interactions in osteocytes cause changes in HDAC5 tyrosine phosphorylation downstream of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and that class IIa HDACs are required for gene expression changes in osteocyte mechanotransduction [120]. However, the relationship between mechanical and distinct hormonal inputs to class IIa HDACs remains to be determined. In addition, future studies with next-generation, highly-specific chemical probes [108] to test the function of the deacetylase domain and N-terminal portions of class IIa HDACs in bone cells will complement the genetic approaches reviewed here. Of note, challenges related to inhibitor specificity and remaining questions regarding the physiologic function (or lack thereof) of the deacetylase domain of class IIa HDACs limit the utility of many studies using currently-available class IIa HDAC pharmacologic inhibitors.

CLASS III HDACs: SIRTUINS

Introduction

Sirtuins are classified as Class 3 HDACs. Structurally unrelated to the other classes of HDACs, sirtuins are orthologues of the silent information regulator (Sir2) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae [121]. Instead of using Zn2+ as a co-factor, sirtuins work as NAD+ dependent deacetylases, which remove the acetyl group from the lysine side chain of a substrate, using NAD+ as a co-substrate [122]. Sirtuins are ubiquitously expressed in humans [123, 124] and possess a conserved catalytic domain and variable N- and C-terminal domains. There are 7 sirtuins in the mammalian system that vary in subcellular localization, the degree of their function as a deacetylase, and their ability to act as an adenosine-dephosphate (ADP) ribosyl transferase activity. Sirt1 is the most extensively studied, and its functions in various systems have been demonstrated, particularly in calorie restriction, aging, energy metabolism, inflammation, neurodegeneration, and cancer. An important role of Sirt1 in bone remodeling and homeostasis has been reported, which will be discussed in this review. In addition, current knowledge of Sirt3, 6, and 7 in the skeletal system will also be addressed.

SIRT1

Sirt1 is known for its NAD+ deacetylating activity, on numerous substrates including histone proteins, p53, p73, HIFs, PPARs, FoxOs, NF-κB, and many more [125]. As the sirtuins were first studied in aging and longevity, numerous studies demonstrated the protective role of Sirt1 against several geriatric diseases, including osteoporosis. Although Sirt1 knockout in 129/Sv mice causes death before 1 month of age [126], Sirt1 knockout mice in a mixed background were smaller in body size as early as embryonic day 12.5 [126], and showed some abnormal skeletal bone phenotypes including under-mineralized bone and defective suture closure in calvariae [127]. These detrimental effects of Sirt1 deficiency in development also agreed with the finding that cartilage-specific Sirt1 deletion at postnatal day 5 resulted in growth retardation and suppression in chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophy, with increased apoptosis, partially due to mTORC1 activation in growth plate [128]. On the other hand, Sirt1 seems to have minimal effects in bones undergoing postnatal growth during childhood or adolescence. Treatment with resveratrol, a Sirt1 activator, showed minimal skeletal effects in in rats during rapid growth [129], and Sirt1 knockout is more detrimental in aged bone (2.2 year old mice versus 2 month old [130]). However, calorie restriction-induced Sirt1 expression in proliferative zone of epiphyseal growth plate was accompanied with reduced Igfbp7 mRNA expression and serum IGF-1 in rapidly growing mice [131], while growth hormone secretion was not altered in Sirt1-knockout mice [127]. As there are conflicting results on whether Sirt1 expression in bone decreases with age [130, 132], it is even more puzzling how Sirt1 deficiency affects aged bone more severely. Thus, more studies are needed to investigate the age-dependent effects of Sirt1 in bone.

In global Sirt1 knockout mice, trabecular bone mass of long bones was decreased, the degree of which was greater with age [132]. Deletion of Sirt1 with Lysozyme M-Cre mice or Col1a1-Cre leads to reduced trabecular bone mass, with increased osteoclasts and decreased osteoblasts, respectively [133], but the double knockout mice did not show additive effect [132], implying that an Sirt1 may simultaneously regulate bone formation and resorption. In contrast to predominant effects of Sirt1 deficiency on trabecular bone, Osterix (Sp7-Cre)-specific Sirt1 deletion in female mice led to cortical bone loss, which suggests that Sirt1 deficiency in more mature osteoblasts is needed for cortical bone loss [134]. Moreover, Sirt1 heterozygous female mice showed reduction in trabecular bone mass with decreased bone formation [135]. In addition, Sirt1 activator (SRT2104) treated mice showed higher trabecular bone mineral density, greater mitochondrial content in muscle, and longer lifespan [136], while Prx1-promoter driven Sirt1 overexpressing mice showed greater body size, bone growth and trabecular bone mass with elevated expression of osteoblast marker genes [137]. Altogether, these studies in genetically-modified mice and pharmacological drugs suggest positive effects of Sirt1 in bone homeostasis, and an essential role in skeletal development and growth. The sex-dependent effect of female mice more severely affected by Sirt1 deletion is not clearly known, thus needs to be further investigated.

There are several mechanisms of how Sirt1 regulates bone homeostasis. One of the mechanisms by which Sirt1 promotes osteogenesis is to suppress adipogenesis at the level of mesenchymal progenitors. Treatment with nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), a key NAD+ intermediate which decreases with age, reduced adipogenesis and promoted osteogenesis in the bone marrow and bone marrow derived cell cultures, through Sirt1 upregulation [138]. Besides, estrogen replacement therapy in OVX mice increased Sirt1 expression and reduced PPAR-gamma and adipogenesis [139]. This suggests the association between Sirt1 expression and bone marrow adipogenesis caused by estrogen deficiency and aging, implying the importance of Sirt1 in regulating the adipogenic versus osteogenic fate of bone marrow mesenchymal cells. Indeed, using the mouse mesenchymal stem cell line C3H10T1/2, Backesjo et al. demonstrated that Sirt1 activators blocked adipogenesis, increased the expression osteoblast markers including osteocalcin and Runx2, and overpowered the PPAR-γ agonist-induced adipogenesis [140–142]. Rat bone marrow stromal cells treated with Sirt1 activator showed greater mineralization and increased osteoblastic genes [140, 141] via deacetylating Runx2, and the direct interaction between Sirt1 and PPAR-γ, forming a complex with NCoR (nuclear receptor co-repressor) [142], which also helps to activate Runx2 [142] and suppress PPAR-γ induced genes [143]. In addition to PPAR- γ, Sirt1 was also shown to interact with PPAR-α to promote osteogenic differentiation, and microRNA-132 also negatively regulate osteogenesis by suppressing Sirt1 and its downstream molecule PPAR-β/δ in MC3TC-E1 cells [144, 145]. Although these findings in MC3T3-E1 cells verification in vivo, this potential role of Sirt1 in regulating osteogenesis versus adipogenesis provides important insight for patients with osteoporosis and metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes.

Another mechanism potentially explaining the osteogenic effect of Sirt1 involves its interaction with FoxO family transcription factors. Osteolineage Sirt1 transgenic mice exhibited osteogenic effects in the bone microarchitecture and histomorphometry analyses while showing increases of Foxo3a and SOD (especially SOD2) mRNA and protein expressions in bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells [137]. Sirt1 was suggested to form a protein complex with FoxO3a via direct interaction and bind to a distal FoxO response element, activating the FOXO responsive element of the Runx2 promoter [146]. This, in turn, upregulates the expressions of osteoblastic genes including Runx2 and Ocn, while suppressing adipogenic genes such as PPAR-γ [146]. Moreover, Sirt1 was demonstrated to play an important role in Wnt signaling. Canonical Wnt target gene expression was significantly reduced in Prx-1-Cre specific Sirt1 knockout mice [130]. Indeed, mutation of lysine resides (at 49 or 345, to arginine) in β-catenin to mimic deacetylation successfully restored nuclear localization of β-catenin and osteoblast differentiation in Sirt1 deficient cells [130]. Sirt1 deficiency in mature osteoblasts (Sp7-Cre) also may induce FoxO binding with β-catenin, sequestering them from expressing osteoblastic genes [134]. Similarly, Sirt1 overexpression in MC3T3-E1 cells downregulated FoxO1 binding with β-catenin, which suppressed apoptosis-related genes, including Gadd45, PPAR-gamma, and Bim [147]. Taken altogether, Sirt1 promotes osteoblastic gene expressions by regulating β-catenin availability in nucleus, and decreases apoptotic genes by regulating decreasing FoxO binding with β-catenin. In addition, Sirt1 may regulate Wnt pathway signaling via indirect mechanisms. As Sirt1+/− mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells showed dramatically elevated mRNA and protein expressions of Sost and sclerostin, respectively, it was demonstrated that Sirt1 directly and negatively targets Sost by deacetylating histone 3 at Lysine 9 at the Sost promoter [135].

Additional mechanisms of how Sirt1 could regulate osteoblastic genes include its interaction with PTH signaling, vitamin D signaling and microRNAs. Sirt1 negatively regulated PTH-induced Mmp13 expression, critical in endochondral ossification and bone formation, thus prolonging the bone anabolic effect of PTH [148]. It was also demonstrated that Resveratrol potentiated 1,25(OH)2-D binding to Vitamin D receptor [149], and 1,25(OH)2-D protected human mesenchymal cells from oxidative stress via Sirt1/FoxO1 signaling (but not FoxO3) by decreasing PPAR-gamma and Caspase 3 expressions, while increasing osteogenic genes including osteopontin, Runx2, Col1a1, and osteocalcin [150].

The anti-oxidant ability of Sirt1 enhances osteogenesis. In human adult bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, oxidative stress up-regulated SIRT1, along with other intracellular antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase 1, suggesting that it is a naturally occurring phenomenon [151]. Sirt1 also exert its beneficial effects on cell viability and anti-apoptosis via deacetylating Akt, which, in turn, resulted in reduced caspase activation [152]. Melatonin, also known for its anti-oxidant effects, was shown to improve bone microarchitectures and mineralization and osteoblastic gene expressions in bone marrow stem cells in OVX rats, through Sirt1-mediated anti-oxidant enzymes [153]. In addition, pre-treatment of bone marrow stem cells with melatonin prevented oxidative damage-mediated phosphorylation of p38 mitogen activated protein kinase, decreased senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity, and encouraged more cells to enter S phase while Sirt1 inhibition blocked these protective effects of melatonin [154]. Furthermore, blueberry juice, as a food rich in Sirt1 activating substances, has shown its benefits in osteosarcoma and osteocyte cells by increasing ALP and Runx2, while decreasing Rankl and Sost expressions, as well as in OVX bone loss by increasing Col1a1 and decreasing collagenase expressions, marrow fat content, and cell senescence [155].

Suppression of NF-κB by Sirt1 is also recognized as a major mechanism of bone remodeling. Sirt1 over-expressing MC3T3-E1 cells suppressed TNF-alpha induced apoptosis and increased Runx2 and osteocalcin expressions and ALP activity [156]. Resveratrol treatment in vitro also inhibited IκBα kinase and IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, and acetylation, nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activity of NF-κB [157–159]. These findings suggest a benefit of resveratrol for for inflammatory disease-induced bone loss, and provide vital knowledge on the role Sirt1 in osteoclastogenesis.

As Sirt1 negatively regulates NF-κB activity, one could speculate that Sirt1 will suppress the action of osteoclast stimulatory cytokines. Indeed, osteoclast progenitor cell specific (Lysozyme M-cre) deletion of Sirt1 in mice resulted in decreased trabecular bone mass with increased osteoclasts on bone surfaces [133]. High dose of melatonin in mouse bone marrow macrophages has also been shown to inhibit osteoclastogenesis via Sirt1-mediated inhibition of NF-κB [160]. Likewise, Resveratrol treatment in RAW264.7 cells inhibited osteoclastogenesis by suppressing RANKL-induced ROS [161], which may be negatively regulated by miR-506 [162]. Furthermore, inhibitory effect Sirt1 on osteoclast proliferation and differentiation is suggested to occur via deacetylating FoxOs, and negatively regulating FoxO target genes such as catalase and hemeoxygenase [163]. This common signaling mechanism of FoxO deacetylation by Sirt1 in osteoblastic and osteoclastic progenitors suggest the dual effects of Sirt1 on bone remodeling [163].

In conclusion, studies on Sirt1 in bone have consistently confirmed the critical role for this factor in favoring osteogenesis, and opposing against aging, oxidative stress, inflammation, and osteoclastogenesis. However, it is worth noting that most of these studies were conducted in in vitro or animal models, and a limited number of studies with human materials are currently available. For example, osteoporotic patients with decreased cortical thickness had reduced Sirt1 mRNA and protein levels, compared to osteoarthritic patients, accompanied with increased sclerostin expression [164]. The bone marrow stromal cells from these patients’ biopsies showed a decrease in sclerostin and an increase in DMP1 after treated with SRT3025, a Sirt1 activator [164]. On the other hand, SIRT1 polymorphisms in humans showed significant association with BMI, but not bone mineral density [165]. Thus, an important area of future study will be to clarify the role of Sirt1 in human bone disease.

SIRT3

As a mitochondrial sirtuin, Sirt3 is well-documented for its role in mitochondrial respiratory chain and energy metabolism [166, 167]. Indeed, Sirt3 is critical in maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential, ultrastructure of mitochondria, oxygen consumption, and mitochondrial density and biogenesis in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells [168]. Previous studies showed that SIRT3 deacetylated of Superoxide Dismutase-2 (SOD2) in capillary endothelial cells and hepatocytes [169, 170]. Sirt3 knockdown in osteoblast cell line (MC3T3-E1) also decreased SOD2 through PGC-1 alpha transcription co-activator for SOD2, increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) [168]. This Sirt3-PGC1alpha-SOD2 interaction is observed in both osteoblasts and osteoclasts as discussed below, and currently recognized as the central pathway used by Sirt3 to regulate bone homeostasis.

Initial studies of Sirt3 in bone were first conducted in osteoclasts as the bone resorbing activity in multinucleated osteoclasts demands high energy [171], and osteoclasts contain large amounts of ROS-producing mitochondria [172]. Moreover, Sirt3 knockout mice showed decreased trabecular bone mass with increased osteoclasts without changes in osteoblast numbers [173]. Sirt3 and SOD2 expression were increased by RANKL [174], and SOD2 knockdown in osteoclast precursors increased osteooclastogenesis [174]. Sirt3-mediated deactylation of SOD2 at lysine 68 [174] and regulation of ROS is currently recognized as the major mechanism used by Sirt3 to control osteoclastogenesis.

However, Sirt3 seems to play a different role in aged bone. Interestingly, Sirt3 overexpressing old mice (6 months or older) showed less bone mass and greater bone marrow adipogenesis, with the increased PGC1β expression and subsequent activation of mTOR pathway in osteoclast precursors [175]. In addition, Sirt3 deletion in older mice also did not show any particular phenotype, suggesting age-dependent effect of Sirt3 in bone [175]. Future studies are needed to explore how endogenous Sirt3 expression is regulated and how Sirt3 exerts age-specific effects in bone.

Even though the number of osteoblasts did not seem to change in Sirt3 knockout mice [173], some studies suggest that Sirt3-PGC1-SOD2 pathway also participates in bone formation. Knock-down of Sirt3 in MC3T3 cells resulted in decreased ALP, Runx2, Col1a1, and osteocalcin [168], and Sirt3 deficient mouse bones show reduced ALP and Runx2 levels while serum BAP, osteocalcin, P1NP, PTH, Calcium, Phosphate, 25(OH)-vitamin D and OPG were all significantly decreased [176]. Likewise, primary osteoblasts from Sirt3 knockout mice showed impaired differentiation, which was improved when SOD2 was overexpressed, suggesting that the Sirt3-SOD2 pathway also is important in osteoblasts. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Sirt3 positively regulates bone homeostasis by promoting osteogenesis, and dampening osteoclastogenesis. On the other hand, the role of Sirt3 in osteoblasts could be limited to growing bone, thus its age-specific effect requires further study. Studies in animals other than rodents, where the growth plate never fuses, are also encouraged, and more studies to investigate the effect of Sirt3 on the overall bone remodeling process in vivo and different bone disease circumstances are needed. Furthermore, as recent studies suggest Sirt3-SOD2 pathway as the mechanism for osteogenic effects of zolendronic acid [177] and melatonin [178], the relation to bone active drugs should also be explored.

SIRT6

Sirt6 has weak NAD-dependent deacetylase activity, rather it functions as a de-fatty acylase and a nuclear ADP-ribosyl transferase. Sirt6 overexpressing mice have increased lifespan [179], and shows protection against age-related metabolic diseases [180, 181], whereas Sirt6 deficient mice die prematurely shortly after 3 weeks of age, with progeroid phenotypes including subcutaneous fat loss, lordokyphosis, colitis, lymphopenia, osteopenia, low serum Igf-1 and hypoglycemia [182]. In humans with a homozygous, inactivating SIRT6 mutation at position 187 (G to C), all four fetuses showed several prenatal abnormalities, including intrauterine growth restriction, congenital heart defects, microcephaly, cephalic and craniofacial abnormalities [183], which were all associated with chromosomal anomalies [184], and eventually led to perinatal death between 17–35 weeks of gestation [183].

The role of Sirt6 in the skeletal development has not been extensively studied. Sirt6 deficient mice showed small body size at 2 weeks of age [182]. Piao et al. suggested that this growth retardation in Sirt6 knockout mice was due to reduced expression of Indian hedgehog in chondrocytes, in which Sirt6 knockdown decreased binding of the transcription factor, Atf4, to the Indian hedgehog promoter [185]. However, considering that there is no endogenous Atf4 association with Sirt6 in primary chondrocytes [185], other indirect factors and paracrine signaling pathways, such as Igf-1 or glucose metabolism-related pathways, should be considered for future studies.

The role of Sirt6 in bone remodeling has been investigated recently. Ovariectomized mice showed decreased Sirt6 expression in bone [186]. Sirt6 deficient mice, in addition to many other progeroid symptoms, showed low-turnover osteopenia at 3 weeks of age [187], with significantly reduced bone growth, loss of cortical and trabecular bone mass, and dramatically decreased bone formation rate and mineral deposits in bone [187, 188]. In human mesenchymal stem cells, SIRT6 knockdown [186] causes decreased osteoblast differentiation, with reduced expression of osteocalcin (BGLAP), osteopontin (SPP1), RUNX2, and Osterix (SP7).

Despite the clear phenotype seen in vivo with Sirt6 deficiency, the mechanism of how Sirt6 regulates osteogenesis requires further investigation. Currently, proposed mechanisms include 1) deacetylation at histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) and subsequent excessive expression of Runx2 and Osx [187], 2) negative regulation of Dkk1 [187], 3) positive regulation of BMP signaling through mechanisms involving PCAF) [186]. However, SIRT6 overexpression has been reported to decrease ALP activity in human mesenchymal stem cells [189], while Sirt6 knockdown in rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells was also reported to decrease ALP activity [190]. These conflicting data suggest that there is species difference between humans and rats, although more evidence is needed. Lastly, there are a handful of studies that suggest anti-inflammatory effects of Sirt6 through NF-κB. Sirt6 overexpression in rat BMSCs showed accelerated bone regeneration with NF-κB suppression [190] and the bone rescuing effect of metformin in type 2 diabetic patients was also partially through increasing SIRT6, which inhibits phosphorylation of NF-κB and reduces RANKL expression [191]. Moreover, given that SIRT6 as a glycolysis regulator, SIRT6 was demonstrated 5) to reduce ROS and lactate generation, as well as hypoxia-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines such as Cyr61, TNF-alpha, IL-1 and IL-6, in human bone marrow derived osteoblasts [192]. This is particularly important in osteoclastogenesis, as pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to stimulate osteoclastogenesis. Altogether, these in vitro studies of Sirt6 in osteoblast-like cells suggest that its actions decrease osteoclastogenesis through indirect mechanisms.

Despite decreased osteoblastogenesis and suppression of NF-κB with Sirt6 deficiency, stimulation of osteoclasts was observed in Sirt6 knockout mice with increased Trap5b in circulation [188], and TRAP-positive osteoclasts on bone surfaces [193]. Interestingly, bone marrow macrophage-derived osteoclasts from Sirt6 knockout mice showed a greater number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts, but a majority of them were small in size and did not contain as many nuclei, compared to those from the wild-type mice [188, 193]. Smaller osteoclasts, however, did not correlate with less resorptive function [193], which suggested greater bone resorption in osteoclasts derived from Sirt6 knockout mice. On the other hand, in Mx1Cre-Sirt6fl/fl [194], bone mass significantly increased with decreased osteoclasts. In this study, the interaction of Sirt6 with Blimp1 seemed most important to explain the osteoclast phenotypes observed [195]. These phenomena strongly suggested that there was paracrine influence on osteoclasts, presumably from the osteoblasts. Indeed, Zhang et al. performed a co-culture experiment of neonatal calvaria derived osteoblasts from wildtype or knockout mice with osteoclasts from bone marrow of either mouse genotype, and showed that osteoclastogenesis was minimally changed by Sirt6 deletion in osteoclast precursors, but was dramatically increased when cultured with Sirt6-deficient osteoblasts [193]. The negative regulation of osteoclastogenesis by Sirt6 through Blimp1 [195] could perhaps explain numerous small osteoclasts from bone marrow of Sirt6 knockout mice, but further studies on the significance of Sirt6 complex with Blimp1 in osteoclast differentiation and fusion are needed.

Moreover, elevated Opg expression in osteoblast cultures from Sirt6 knockout mice provide another possible mechanism used by Sirt6 to control osteoblast-osteoclast crosstalk [187]. In this paper, co-culture of splenocytes with osteoblasts from wild-type and Sirt6 knockout mice showed the inhibitory effect of Sirt6 deficiency on osteoclastogenesis [187]. These conflicting data suggest that there could be differences in osteoclasts from bone marrow and spleen, depending on the presence of nearby osteoblasts in their micro-environment. The interaction between osteoblasts and osteoclasts should be carefully studied in the context of the previously-discussed anti-inflammatory effects of Sirt6. Certainly, future studies on the role of Sirt6 in osteoclastogenesis at the autonomous (within osteoclasts) versus paracrine (interaction between osteoclasts and osteoblasts) levels are needed to understand its function in bone remodelling. In addition, studies on how Sirt6 is controlled in a physiological condition could provide some insight. Nonetheless, as Sirt6 expression is reduced in the ovariectomized animals [186], its potential as a therapeutic agent should also be considered, and Sirt6 in other forms of osteoporosis should be explored.

SIRT7

Sirt7 is found in the cell nucleus as a NAD+ dependent deacetylase and a histone de-succinylase, and participates in a wide range of cellular activities, such as glycolysis, mitochondrial function, DNA repair, and aging, and tumorigenesis and chemo-sensitivity in cancer cells [196]. As the least studied sirtuin, relatively little is known about the role of Sirt7 in the skeletal system. SIRT7 knockdown in human bone marrow stromal cell cultures caused enhanced osteogenic potential, partly through the activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway [197]. In contrast, Fukuda et al. reported that Sirt7 is an essential deacetylator in Sp7/Osterix at lysine 368, and that both global and Col1a1-Cre driven knockout of Sirt7 in mice resulted in osteopenia with decreased bone formation and increased osteoclasts [198]. Considering this conflicting evidence, more comprehensive studies are needed to clarify the role of Sirt7 in bone remodeling.

In conclusion, sirtuins have diverse and important roles in bone remodeling. Study of sirtuins in bone cells is a relatively new area. We note that scarce amount information is available, especially for the sirtuins not mentioned in this review. While more studies will certainly clarify some conflicting data, the interaction and any redundancy between different sirtuins, and the substrate specificity of each sirtuin should be carefully examined. Future study using tissue specific knockout mice, specific pharmacologic inhibitors, and unbiased approaches to identify sirtuin substrates in bone cells will undoubtedly lead to new and important insights regarding the role of these fascinating NAD+-dependent deacetylases in skeletal biology.

CONCLUSIONS

As discussed above, class I, IIa, and III HDACs play distinct roles in bone cell physiology based on distinct catalytic domain sequence/activity, subcellular localization, ability to respond to upstream signaling cascades, cofactor requirements, substrate specificity, and expression patterns. Ample evidence now exists to demonstrate that HDACs play important roles in bone cell biology and skeletal homeostasis. Future studies are needed to explore the function of HDACs not discussed here (class IIb and class IV) in bone development and remodeling. Development of ‘next generation’ HDAC inhibitors that are truly class- and isoform-selective will be facilitated by increasing knowledge into the catalytic mechanisms of these proteins and allosteric determinants of key protein/protein interactions. The next decade of HDAC research in bone will be driven by new cell type-specific genetic models, human disease and cell culture systems, novel pharmacologic tools, advances in epigenomics, and new knowledge regarding physiologic non-histone substrates in bone cells.

Highlights.

Our cells bear three main classes of histone deacetylases (HDACs)

Class I HDACs deacetylate histones and regulate chromatin structure

Class IIa HDACs shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus

Class III HDACs are NAD+-dependent Sirtuin deacetylases

Multiple roles of HDACs in skeletal biology are reviewed here

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Wein laboratory for stimulating discussions. MNW acknowledges support from the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research (Rising Star award) and the NIH (DK116716 and DK011794).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests Statement

MNW receives research funding from Radius Health and Galapagos NV on projects unrelated to this review. These funders had no role in preparation of this review manuscript or decision to publish. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cavalli G and Heard E, Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature, 2019. 571(7766): p. 489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornberg RD and Thomas JO, Chromatin structure; oligomers of the histones. Science, 1974. 184(4139): p. 865–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luger K, et al. , Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature, 1997. 389(6648): p. 251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kouzarides T, Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell, 2007. 128(4): p. 693–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou VW, Goren A, and Bernstein BE, Charting histone modifications and the functional organization of mammalian genomes. Nat Rev Genet, 2011. 12(1): p. 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee KK and Workman JL, Histone acetyltransferase complexes: one size doesn’t fit all. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2007. 8(4): p. 284–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue A and Fujimoto D, Enzymatic deacetylation of histone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1969. 36(1): p. 146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seto E and Yoshida M, Erasers of histone acetylation: the histone deacetylase enzymes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2014. 6(4): p. a018713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinke H and Horz W, Histones are first hyperacetylated and then lose contact with the activated PHO5 promoter. Mol Cell, 2003. 11(6): p. 1599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhalluin C, et al. , Structure and ligand of a histone acetyltransferase bromodomain. Nature, 1999. 399(6735): p. 491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunstein M, Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature, 1997. 389(6649): p. 349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strahl BD and Allis CD, The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature, 2000. 403(6765): p. 41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekker J, Marti-Renom MA, and Mirny LA, Exploring the three-dimensional organization of genomes: interpreting chromatin interaction data. Nat Rev Genet, 2013. 14(6): p. 390–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falkenberg KJ and Johnstone RW, Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors in cancer, neurological diseases and immune disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2014. 13(9): p. 673–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benedetti R, Conte M, and Altucci L, Targeting Histone Deacetylases in Diseases: Where Are We? Antioxid Redox Signal, 2015. 23(1): p. 99–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksen EF, Cellular mechanisms of bone remodeling. Rev Endocr Metab Disord, 2010. 11(4): p. 219–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobacchi C, et al. , Osteopetrosis: genetics, treatment and new insights into osteoclast function. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2013. 9(9): p. 522–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng X and McDonald JM, Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Pathol, 2011. 6: p. 121–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein BE, Tong JK, and Schreiber SL, Genomewide studies of histone deacetylase function in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000. 97(25): p. 13708–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Ruijter AJ, et al. , Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J, 2003. 370(Pt 3): p. 737–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gregoretti IV, Lee YM, and Goodson HV, Molecular evolution of the histone deacetylase family: functional implications of phylogenetic analysis. J Mol Biol, 2004. 338(1): p. 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robyr D, et al. , Microarray deacetylation maps determine genome-wide functions for yeast histone deacetylases. Cell, 2002. 109(4): p. 437–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang XJ and Seto E, Collaborative spirit of histone deacetylases in regulating chromatin structure and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 2003. 13(2): p. 143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guenther MG, Barak O, and Lazar MA, The SMRT and N-CoR corepressors are activating cofactors for histone deacetylase 3. Mol Cell Biol, 2001. 21(18): p. 6091–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durst KL, et al. , The inv(16) fusion protein associates with corepressors via a smooth muscle myosin heavy-chain domain. Mol Cell Biol, 2003. 23(2): p. 607–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley EW, et al. , Histone Deacetylases in Bone Development and Skeletal Disorders. Physiol Rev, 2015. 95(4): p. 1359–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smits P, et al. , The transcription factors L-Sox5 and Sox6 are essential for cartilage formation. Dev Cell, 2001. 1(2): p. 277–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inada M, et al. , Maturational disturbance of chondrocytes in Cbfa1-deficient mice. Dev Dyn, 1999. 214(4): p. 279–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueta C, et al. , Skeletal malformations caused by overexpression of Cbfa1 or its dominant negative form in chondrocytes. J Cell Biol, 2001. 153(1): p. 87–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komori T, et al. , Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell, 1997. 89(5): p. 755–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otto F, et al. , Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell, 1997. 89(5): p. 765–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakashima K, et al. , The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell, 2002. 108(1): p. 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berendsen AD and Olsen BR, Bone development. Bone, 2015. 80: p. 14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee HW, et al. , Histone deacetylase 1-mediated histone modification regulates osteoblast differentiation. Mol Endocrinol, 2006. 20(10): p. 2432–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schroeder TM and Westendorf JJ, Histone deacetylase inhibitors promote osteoblast maturation. J Bone Miner Res, 2005. 20(12): p. 2254–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagger G, et al. , Essential function of histone deacetylase 1 in proliferation control and CDK inhibitor repression. EMBO J, 2002. 21(11): p. 2672–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng L, et al. , Shh establishes an Nkx3.2/Sox9 autoregulatory loop that is maintained by BMP signals to induce somitic chondrogenesis. Genes Dev, 2002. 16(15): p. 1990–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murtaugh LC, et al. , The chick transcriptional repressor Nkx3.2 acts downstream of Shh to promote BMP-dependent axial chondrogenesis. Dev Cell, 2001. 1(3): p. 411–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong S, et al. , A novel domain in histone deacetylase 1 and 2 mediates repression of cartilage-specific genes in human chondrocytes. FASEB J, 2009. 23(10): p. 3539–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu CJ, et al. , Leukemia/lymphoma-related factor, a POZ domain-containing transcriptional repressor, interacts with histone deacetylase-1 and inhibits cartilage oligomeric matrix protein gene expression and chondrogenesis. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(45): p. 47081–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huh YH, Ryu JH, and Chun JS, Regulation of type II collagen expression by histone deacetylase in articular chondrocytes. J Biol Chem, 2007. 282(23): p. 17123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner VF, et al. , A De novo HDAC2 variant in a patient with features consistent with Cornelia de Lange syndrome phenotype. Am J Med Genet A, 2019. 179(5): p. 852–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trivedi CM, et al. , Hdac2 regulates the cardiac hypertrophic response by modulating Gsk3 beta activity. Nat Med, 2007. 13(3): p. 324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emmett MJ and Lazar MA, Integrative regulation of physiology by histone deacetylase 3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2019. 20(2): p. 102–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh N, et al. , Histone deacetylase 3 regulates smooth muscle differentiation in neural crest cells and development of the cardiac outflow tract. Circ Res, 2011. 109(11): p. 1240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh N, et al. , Murine craniofacial development requires Hdac3-mediated repression of Msx gene expression. Dev Biol, 2013. 377(2): p. 333–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Razidlo DF, et al. , Histone deacetylase 3 depletion in osteo/chondroprogenitor cells decreases bone density and increases marrow fat. PLoS One, 2010. 5(7): p. e11492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]