Summary

Inborn errors of human IFN-γ immunity underlie mycobacterial disease. We report a patient with mycobacterial disease due to inherited deficiency of the transcription factor T-bet. The patient has extremely low counts of circulating Mycobacterium-reactive NK, invariant NKT (iNKT), mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT), and Vδ2+ γδ T lymphocytes, and of Mycobacterium-non reactive classic TH1 lymphocytes, with the residual populations of these cells also producing abnormally small amounts of IFN-γ. Other lymphocyte subsets develop normally, but produce low levels of IFN-γ, with the exception of CD8+ αβ T and non-classic CD4+ αβ TH1* lymphocytes, which produce IFN-γ normally in response to mycobacterial antigens. Human T-bet deficiency thus underlies mycobacterial disease by preventing the development of innate (NK) and innate-like adaptive lymphocytes (iNKT, MAIT, and Vδ2+ γδ T cells) and IFN-γ production by them, with mycobacterium-specific, IFN-γ-producing, purely adaptive CD8+ αβ T and CD4+ αβ TH1* cells unable to compensate for this deficit.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In the course of primary infection, life-threatening disease in otherwise healthy children, adolescents, and even adults, can result from monogenic inborn errors of immunity (IEI), which display genetic heterogeneity and physiological homogeneity (Casanova, 2015a, 2015b). Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease (MSMD) is characterized by a selective, inherited predisposition to clinical disease caused by weakly virulent mycobacteria, such as Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccines and environmental mycobacteria (EM) (Bustamante, 2020; Kerner et al., 2020). Patients are also vulnerable to bona fide tuberculosis. Patients with typical, “isolated” MSMD are rarely prone to other infectious agents, with the exception of Salmonella and occasionally other intra-macrophagic bacteria, fungi, and parasites. Patients with atypical, “syndromic” MSMD often display other clinical phenotypes, infectious or otherwise. MSMD, both “isolated” and “syndromic”, displays a high level of genetic heterogeneity, with causal mutations in 16 genes, and additional allelic heterogeneity, resulting in 31 different disorders. However, there is also physiological homogeneity, as all known genetic causes of MSMD affect interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-dependent immunity (Bustamante, 2020; Kerner et al., 2020; Rosain et al., 2019). Mutations of IFNG, IL12B, IL12RB1, IL12RB2, IL23R, TYK2, ISG15, RORC, IKBKG (NEMO), IRF8, and SPPL2A impede IFN-γ production by innate and adaptive immune cells, whereas mutations of IFNGR1, IFNGR2, STAT1, JAK1, and CYBB impair cellular responses to IFN-γ (Fig. S1A). The clinical penetrance and severity of MSMD depend strongly on genetic etiology and increase with decreasing levels of IFN-γ activity (Dupuis et al., 2000). Seven etiologies also result in an impairment of immunological circuits other than the IFN-γ circuit, accounting for “syndromic” MSMD in the corresponding patients (Bustamante, 2020). Collectively, these studies revealed the crucial role of human IFN-γ in antimycobacterial immunity and its redundancy for immunity against many other pathogens.

The cellular basis of MSMD in patients with impaired responses to IFN-γ involves mononuclear phagocytes. The ability of these cells to contain the ingested mycobacteria depends on their activation by IFN-γ (Nathan et al., 1983). The cellular basis of MSMD in patients with impaired IFN-γ production is poorly understood, as most types of lymphocytes can produce IFN-γ (Schoenborn and Wilson, 2007). Some genetic etiologies of MSMD affect some lymphocyte subsets more than others. ISG15 deficiency preferentially impairs the production of IFN-γ by NK cells (Bogunovic et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015). IL-12Rβ2 deficiency preferentially impairs the production of IFN-γ by NK, B, γδ T, classic αβ T cells, type 1 innate lymphoid cells (ILC1s), and ILC2s, whereas IL-23R deficiency preferentially impairs the production of this cytokine by invariant NKT (iNKT) and mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, and both IL-12Rβ1 and TYK2 deficiencies impair both the IL-12- and IL-23-dependent subsets (Boisson-Dupuis et al., 2018; Martínez-Barricarte et al., 2018). SPPL2a and IRF8 deficiencies selectively impair the production of IFN-γ by CD4+ CCR6+ TH1 (TH1*) cells (Hambleton et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2018), a TH1 cell subset enriched in Mycobacterium-specific effector cells, whereas CCR6− TH1 cells do not respond to mycobacteria (Acosta-Rodriguez et al., 2007). RORγ/RORγT deficiency impairs the development of iNKT and MAIT cells, and also compromises the production of IFN-γ by γδ T and αβ TH1* cells (Okada et al., 2015). Interestingly, although the lack of both αβ T and γδ T cells in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) underlies BCG disease (Casanova et al., 1995), most, if not all other deficits of antigen-specific αβ T-cell responses, whether affecting only CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, such as MHC class II and MHC class I deficiencies, respectively, typically do not (Aluri et al., 2018; Ardeniz et al., 2015; Dimitrova et al., 2014; Elhasid and Etzioni, 1996; Hanalioglu et al., 2017; Hanna and Etzioni, 2014; De La Salle et al., 1994; Lum et al., 2019, 2020; Morgan et al., 2011; Saleem et al., 2000; Zimmer et al., 2005). Moreover, selective deficiencies of NK or iNKT cells do not confer a predisposition to mycobacterial disease (Casey et al., 2012; Cottineau et al., 2017; Hughes et al., 2012; Latour, 2007; Locci et al., 2009; Tangye et al., 2017). The nature of the IFN-γ-producing innate, innate-like adaptive, and purely adaptive lymphocyte subsets indispensable for antimycobacterial immunity, either alone or in combination, therefore remains largely unknown. No genetic cause has yet been identified for half the MSMD patients. We therefore sought to discover a new genetic etiology of MSMD that would expand the molecular circuit controlling human IFN-γ immunity while better delineating the cellular network involved.

Results

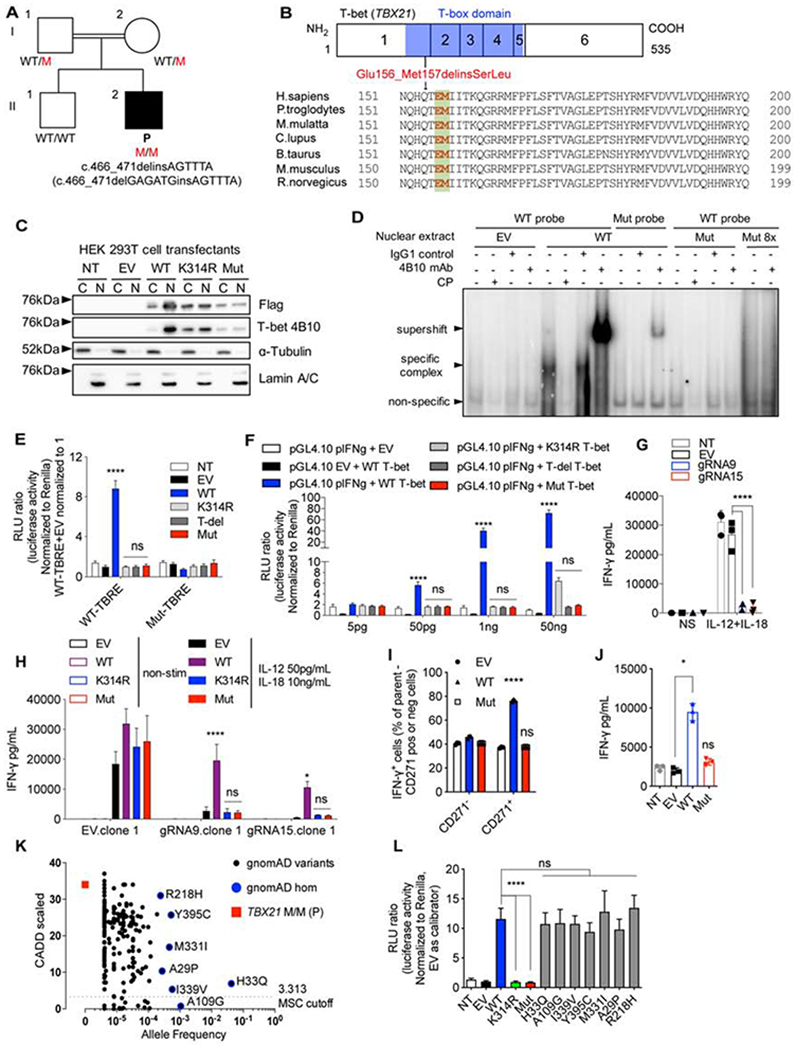

Identification of an MSMD patient homozygous for an indel variant of TBX21

We studied a three-year-old boy (“P”, II.2) born to first-cousin Moroccan parents (Fig. 1A). He suffered from disseminated BCG disease (BCG-osis) following vaccination at the age of three months. He also had persistent reactive airway disease (RAD), but was otherwise healthy (see STAR Methods - Case Report). He did not suffer from any other severe clinical infectious diseases despite documented (VirScan) infection with various viruses, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human cytomegalovirus (CMV), roseola virus, adenoviruses A, B, C and D, influenza virus A, rhinovirus A, and bacteria, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus (Fig. S1B). We hypothesized that P had an autosomal recessive (AR) defect. We performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) on P, his unaffected brother, and both parents. Genome-wide linkage (GWL) analysis revealed 32 linked regions (LOD score >1.3 and size >500 kb) under a model of complete penetrance (Supplemental Data S1). In these linked regions, there were 15 rare homozygous non-synonymous or essential splicing variants of 15 different genes (minor allele frequency, MAF < 0.003 in gnomAD v2.1 and 1000 Genomes Project, including for each major ancestry) with a combined annotation-dependent depletion (CADD) score above their mutation significance cutoffs (MSC) (Auton et al., 2015; Itan et al., 2016; Karczewski et al., 2020; Kircher et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018) (Table S1). After the exclusion of genes with other predicted loss-of-function (LOF) variants with a frequency greater than 0.5% in gnomAD and of genes not expressed in leukocytes, only four candidate genes (TBX21, PSMD9, ARHGAP27 and ERN1) remained. The c.466_471delGAGATGinsAGTTTA insertion and/or deletion (indel) variant of TBX21 (T-box protein 21, or T-box, expressed in T cells, T-bet) was the candidate variant predicted to be the most damaging (Kircher et al., 2014). Moreover, based on connectivity to IFNG, the central gene of the entire network of all known MSMD-causing genes (Itan et al., 2013, 2014), TBX21 was the most plausible candidate gene (Table S1). T-bet is a transcription factor that governs the development or function of several IFN-γ-producing lymphocytes in mice, including TH1 cells (Lazarevic et al., 2013; Szabo et al., 2000, 2002). These findings suggested that homozygosity for the rare indel variant c.466_471delGAGATGinsAGTTTA of TBX21 causes MSMD. We investigated this variant according to the guidelines for genetic studies of single patients (Casanova et al., 2014). Sanger sequencing confirmed that P was homozygous for the indel variant of exon 1 of TBX21, whereas his unaffected brother was homozygous wild-type (WT/WT) and both parents were heterozygous (WT/M) (Fig. S1C). A closely juxtaposed 12-nucleotide (nt) region identical to this variant sequence was detected 8-nt upstream from the variant, and may have served as a template for its generation (Fig. S1D). The variant did not alter the exon 1-exon 2 junction of the TBX21 mRNA in EBV-transformed B (EBV-B) cells or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Supplemental databases S1). The variant present in P thus resulted in the replacement of E156 and M157, two amino acids that are highly conserved across different species and among other paralogs of T-box transcription factors, with S156 and L157 (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1E).

Figure 1. Discovery of an MSMD patient with a homozygous TBX21 variant and the corresponding molecular characterization.

(A) Pedigree of a consanguineous family with the mutant TBX21 allele. (B) Schematic representation of the mutation. (C) Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions from HEK 293T cells transfected with indicated TBX21 cDNA-containing vectors subjected to immunoblotting against indicated proteins. (D) EMSA on nuclear extracts of HEK293T cells transfected with empty vector (EV), WT or Mut TBX21 alleles. (E) TBRE-reporter luciferase assay testing WT or Mut T-bet in HEK 293T cells. (F) Human IFNG reporter luciferase assay testing HEK 293T cells transfected with WT or Mut TBX21 cDNA-containing vectors, at the indicated concentrations. (G) IFN-γ production in response to stimulation with IL-12 and IL-18 in T-bet knock-out (KO) NK-92 cells. (H) IFN-γ production in response to stimulation with IL-12 and IL-18 in T-bet KO NK-92 cells complemented with EV, WT, K314R or Mut TBX21-containing plasmids. (I) Intracellular IFN-γ production in response to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (P/I) in expanding TH0 cells transduced with EV, WT or Mut TBX21 cDNA. (J) IFN-γ production from cells transduced as in (I) in response to stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 Ab. (K) Graph of CADD score against minor allele frequency (MAF), for TBX21 variants reported in the gnomAD. Mutation significance cutoff (MSC) was shown. (L) TBRE-reporter luciferase assay testing indicated variants of TBX21 as in (E). See also Figure S1, Table S1, and Supplemental Data S1.

In Fig. 1E - J and L, bars represent the mean and standard deviation. Dots represent individual samples or technical replicates. Two-way ANOVA was used for analysis in (E – I). One-way ANOVA was used for analysis in (J and L). In (E – J and L), * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, ns = not significant.

Overexpressed mutant T-bet is LOF

We investigated the expression of the mutant allele (Mut), by overexpressing an empty vector (EV), or vectors containing the WT or Mut allele, or negative controls with the T-box domain deleted (T-del) or K314R, the human ortholog of a known LOF mouse mutant, in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells (Jang et al., 2013). The production and nuclear translocation of Mut T-bet were impaired (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1F). An assessment of its binding to consensus T-box regulatory elements (TBRE) in DNA revealed that nuclear proteins from WT-transfected cells bound the WT-TBRE, but not the Mut-TBRE. Furthermore, this specific complex was super-shifted by an anti-T-bet antibody (Ab) and inhibited by a competitor probe (CP). However, Mut T-bet did not bind WT-TBRE DNA (Fig. 1D). We also assessed the ability of WT and Mut T-bet to induce a luciferase transgene under the control of the TBRE or human IFNG proximal promoter (Janesick et al., 2012; Soutto et al., 2002). WT T-bet induced high levels of luciferase activity with WT-TBRE but not with Mut-TBRE. Mut T-bet and the negative controls (T-del and K314R) did not induce luciferase activity (Fig. 1E). Mut T-bet was also LOF for transactivation of the IFNG promoter, whereas the negative control, K314R, was markedly hypomorphic (Fig. 1F). We investigated the amino-acid substitution responsible for the abolition of transcriptional activity. We tested the effects of the WT and Mut forms of T-bet and of T-bet forms with single-residue substitutions (E156S and M157L), or alanine substitutions (E156A and M157A) on T-bet protein production and transcriptional activity. The loss of E156 (E156S and E156A) abolished transcriptional activity, but the production of the T-bet protein was unaffected. By contrast, a loss of methionine residues (M157L and M157A) preserved transcriptional activity but decreased the levels of T-bet protein (Fig. S1G and H). T-bet is required for optimal IFN-γ production in NK, ILCs, γδ, and CD4+ T cells in mice and is sufficient for IFN-γ production in NK and CD4+ T cells in humans (Chen et al., 2007; Lazarevic et al., 2013; Powell et al., 2012; Szabo et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2006). We investigated the impact of the T-bet mutation on the induction of IFNG expression, by generating CRISPR/Cas9 gene-edited human NK-92 cell lines lacking TBX21 (Supplemental Data S1). Upon stimulation with IL-12 + IL-18, these TBX21 knockout (KO) NK-92 cells displayed a strong impairment of IFN-γ production (Fig. 1G and Fig. S1I). We re-introduced the WT or Mut TBX21-containing plasmid into TBX21 KO NK-92 cells. We found that the WT TBX21 rescued IFN-γ production, whereas the Mut TBX21 did not (Fig. 1H and Fig. S1J). Finally, the overexpression of WT, but not of Mut T-bet increased IFN-γ levels to values above those for endogenous production in expanding naïve CD4+ T cells from healthy donors (Fig. 1I and J, Fig. S1K). Thus, overexpression of Mut T-bet abolished DNA binding, and the mutant protein had no transactivation activity and could not induce IFN-γ production in an NK cell line or CD4+ T cells. It can, therefore, reasonably be considered a LOF allele.

TBX21 variants in the general population are functional

The TBX21 indel variant in P was not found in the gnomAD v2.1.1, v3, Bravo, or Middle Eastern cohort databases, or our in-house database of more than 8,000 exomes, including > 1,000 for individuals of North African origin (Karczewski et al., 2020; Scott et al., 2016; Taliun et al., 2019). The CADD score of 34 obtained for this allele is well above the MSC of 3.313 (Fig. 1K) (Itan et al., 2016; Kircher et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018). The TBX21 gene has a low tolerance of deleterious variations, with a low gene damage index (GDI) score of 3.493 (Itan et al., 2015) and a low residual variation intolerance score (RVIS: −0.74) (Petrovski et al., 2015). Moreover, only two predicted LOF variants (variants: 17:47745045 A/AGCTG, and 17:47744913 C/G) were found in the heterozygous state in gnomAD. As their MAFs were <5x10-6, homozygosity rates for any of these three variants are well below the prevalence of MSMD (about 1/50,000). In the general population covered by the gnomAD database, seven variants have been identified in the homozygous state: A109G has a low CADD score, below the MSC, whereas H33Q, I339V, Y395C, M331I, R218H, and A29P have CADD scores above the MSC (Fig. 1K and Supplemental Data S1). The mouse ortholog of H33Q (H32Q) has been shown to be functionally neutral (Tantisira et al., 2004). None of these seven alleles affected transactivation of the WT-TBRE promoter (Fig. 1L). Thus, all the TBX21 variants present in the homozygous state in gnomAD are functionally neutral. In our in-house cohort of >8,000 exomes from patients with various infectious phenotypes, P is the only patient carrying a rare biallelic variant at the TBX21 locus. We investigated whether any of the other 36 non-synonymous variants of TBX21 in our in-house database could underlie infections in the heterozygous state, by testing each of them experimentally (Supplemental Data S1). None had any functional impact on transcriptional activity (Fig. S1L and M). Therefore, the data for P and his family, our in-house cohort, and the general population suggest that inherited T-bet deficiency, whether complete or partial, is exceedingly rare in the general population (< 5.8 x 10-8). These findings also suggest that homozygosity for the Mut LOF variant of TBX21 is responsible for MSMD in P.

Homozygosity for the TBX21 mutation underlies complete T-bet deficiency

We investigated the production and function of endogenous Mut T-bet in Herpes saimiri virus-transformed T cells (HVS-T) and primary CD4+ T cells from P. Levels of TBX21 mRNA were normal, but endogenous T-bet protein levels were low in P’s cells (Fig. 2A and B, Fig. S2A and B). Together with the observation of low levels of Mut T-bet protein on overexpression (Fig. S1F), these findings suggest that the TBX21 mutation decreases T-bet protein levels by a post-transcriptional mechanism. T-bet transactivates IFNG and TNF by directly binding to their regulatory promoter or enhancer (Garrett et al., 2007; Kanhere et al., 2012; Soutto et al., 2002; Szabo et al., 2000; Tong et al., 2005). Levels of spontaneous IFN-γ and TNF-α production by P’s HVS-T cells were much lower than those for HVS-T cells from all the healthy donors and heterozygous relatives tested (Fig. 2C - F). This cytokine production defect in TBX21 mutant HVS-T cells was rescued by WT T-bet complementation (Fig. 2G and Fig. S2C). We investigated whether homozygous variants of PSMD9, ARHGAP27, or ERN1 contributed to the low levels of IFN-γ production, by transducing HVS-T cells from P with the WT cDNAs of PSMD9, ARHGAP27, or ERN1. Overexpression of the WT PSMD9, ARHGAP27, or ERN1 did not rescue the IFN-γ deficit (Fig. S2D - G). Moreover, the overexpression of these genes in HVS-T cells from P that had already been transduced with WT TBX21 did not further enhance IFN-γ production. These data suggest that PSMD9, ARHGAP27, and ERN1 variants make no significant contribution to the patient’s immunological and clinical phenotype (Fig. S2H and I).

Figure 2. The T-bet variant in patient-derived cells is loss-of-function.

(A) Whole-cell lysates from expanding CD4+ T cells from healthy donors (CTL), a heterozygous parent (WT/M) and the patient (M/M) subjected to immunoblotting. (B) Immunoblotting against indicated proteins of whole-cell lysates of HVS-T cells derived from CTL, M/M and WT/M. (C and D) Spontaneous production of IFN-γ (C) and TNF-α (D) from cultures of HVS-T cells from CTL, M/M and WT/M. (E and F) The IFNG (E) and TNF (F) expression of HVS-T cells, as in (C), was assessed by RT-qPCR. (G) HVS-T cells from M/M were rescued with EV or WT TBX21. The percentage of intracellular IFN-γ-producing cells with or without P/I stimulation is shown. (H) CD4+ T cells from CTL, M/M and WT/M were expanded under TH0 or TH1 conditions. M/M cells were transduced as described in (G). Cells were subjected to ICS for IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to P/I. (I) Percentage of IFN-γ- and TNF-α-producing cells in (H). (J) Transduced TH0 cells, as in (H), were isolated and restimulated, and were subjected to RNA-seq, along with non-transduced cells. Pathway enrichment among differentially regulated genes is shown. (K) The numbers of T-bet-dependent differentially expressed immune genes in RNA-seq are shown. (L) Heat-map of selected T-bet-dependent downstream genes, as in (K). See also Figure S2, Table S2, and Supplemental Data S1.

In Fig. 2C – G and I, bars represent the mean and the standard error of the mean. Dots represent individual samples. One-way ANOVA was used for analysis in (C and D). Mann-Whitney tests were used for analysis in (E and F), comparing WT/M or M/M to CTL. In (C - F), * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, and ns = not significant.

T-bet deficiency alters the expression of downstream target genes

The functional impact of the T-bet mutation was also investigated in primary CD4+ T cells. Upon stimulation with P/I, IFN-γ production was almost entirely abolished in P’s expanded TH0 cells and TNF-α production was impaired; the production of both these molecules was rescued by WT T-bet (Fig. 2H and I, Fig. S2J and K). In TH1 conditions, exogenous IL-12 bypassed T-bet and induced moderate IFN-γ production by P’s cells. However, the levels of IFN-γ were still ~60-70% lower than those in healthy donors (Fig. 2H and I). We investigated other T-bet-dependent transcriptional targets, by performing RNA-seq to compare TH0 cells from 4 healthy donors, P, and P’s cells complemented with WT T-bet after incubation with anti-CD3/28 Ab beads. We found that 415 genes were downregulated and 489 genes were upregulated in P’s cells relative to healthy donors (Supplemental Data S1, Table S2). The complementation of P’s cells with WT T-bet reversed the differential expression of 99 of the downregulated and 161 of the upregulated genes (Supplemental Data S1). Thus, only a subset of differentially regulated genes were rescued, possibly due to differences in genetic variants other than TBX21 between controls and P. Alternatively, T-bet may control the differential expression of some genes early in activation, and the genetic rescue may have occurred too late to reverse this effect. These targets were enriched in cytokine signaling pathway genes (Fig. 2J). We therefore decided to focus on genes involved in immunological signaling. Only 32 such genes were upregulated or downregulated in P’s cells, but these differences in expression relative to controls were reversed by WT T-bet (Fig. 2K). Known T-bet-dependent targets, such as IFNG, CCL3 and CXCR3, were downregulated in CD4+ T cells from the T-bet-deficient patient, whereas IFNGR2 expression was upregulated (Fig. 2L) (Iwata et al., 2017; Jenner et al., 2009). A set of new T-bet target genes was also identified, including CCL1, CCL13, CCL4, CSF2, CXCR5, GZMM, CD40, CD86, IL7R, IL10, LTB, ITGA5, and ITGB5 (Fig. 2L). Collectively, our data indicate that the patient had AR complete T-bet deficiency, affecting the expression of a set of T-bet-dependent target genes, including IFNG.

T-bet induces permissive chromatin accessibility and CpG methylation in IFNG

We analyzed the molecular mechanisms by which T-bet controls transcription. Epigenetically, T-bet is known to induce a permissive environment for transcription at the IFNG promoter through histone modifications and the suppression of CpG methylation (Lewis et al., 2007; Miller and Weinmann, 2010; Tong et al., 2005). However, it remains unknown whether T-bet directly regulates chromatin accessibility in mice or humans. The regulation of CpG methylation at the genome-wide scale by T-bet has never been studied. We performed omni-ATAC-seq analysis and EPIC DNA CpG methylation array analysis with TH0 cells derived from P and controls. In P’s cells, a gain of chromatin accessibility was observed at 1,661 loci and a loss of chromatin accessibility was observed at 3,675 loci (Fig. 3A and B, Supplemental Data S1, Table S3). We found that 662 and 1,642 of these loci, respectively, were subject to strict regulation by T-bet, as their gains and losses of chromatin accessibility were reversed by WT T-bet (Fig. 3B, Table S3). The chromatin regions opened up by T-bet were heavily occupied by bound T-bet, whereas those closed by T-bet did not typically require T-bet binding (Fig. 3C) (Kanhere et al., 2012). An enrichment in T-box binding elements was observed in loci for which chromatin accessibility was increased by T-bet, whereas an enrichment in Forkhead box elements was observed at loci for which chromatin accessibility was decreased by T-bet (Fig. 3D and E). The chromatin accessibility of 181 immunological genes (247 loci), including IFNG, CYBB, and TYK2, three known MSMD-causing genes, was increased by T-bet, whereas that of 73 immunological genes (82 loci) was decreased by T-bet (Fig. 3F, Supplemental Data S1, and Table S3). Three known T-bet-dependent targets, IFNG, TNF and CXCR3, were among the top hits for the differentially regulated loci. The transcription start sites (TSS) of IFNG and TNF, the proximal promoter of IFNG, and the enhancers of CXCR3 were inaccessible in T-bet-deficient cells, and this inaccessibility was rescued by WT T-bet (Fig. 3G - I). The EPIC DNA CpG methylation array analysis identified 644,236 CpG sites that were differentially regulated (Table S3). Three CpG loci within IFNG were hypermethylated in conditions of T-bet deficiency, whereas their methylation was reduced to levels similar to those in controls on complementation with WT T-bet (Fig. 3J and K). NR5A2, TIMD4, ATXN2, ZAK, SLAMF8, TBKBP1, CD247, HDAC4 and several other genes were also regulated in a similar manner (Fig. 3J and Table S3). Interestingly, the methylation of six CpG loci within ENTPD1 not previously linked to T-bet also increased in a T-bet-dependent manner (Fig. 3J and L). By contrast, IL10 was a top target for which CpG methylation was drastically reduced in T-bet deficiency but rescued by WT T-bet (Fig. 3M). Taken together, these results demonstrate that T-bet orchestrates the expression of target genes by modulating both their chromatin accessibility and CpG methylation. Genome-wide omni-ATAC-seq and CpG methylation array analyses identified new epigenetic targets of T-bet (Table S3). They also showed that chromatin accessibility at IFNG was increased by T-bet at both the TSS and promoter sites, whereas the CpG methylation of IFNG was decreased by T-bet at three different positions.

Figure 3. An altered spectrum of epigenetic regulation in CD4+ T cells in T-bet deficiency.

(A) Expanded CD4+ TH0 cells from CTL, IL-12Rβ1-deficient MSMD patients (IL12RB1 M/M), WT/M, M/M, and M/M cells complemented with empty vector (M/M +EV) or with WT T-bet (M/M +WT) were subjected to omni-ATAC-seq. PCA analysis of the peaks called in the various samples, plotted in ggplot2. (B) Number of called peaks differentially regulated as indicated. (C) Heatmap of all loci opening or closing in a T-bet-dependent manner as in (B). (D and E) The most significantly enriched DNA binding motifs at loci displaying T-bet-dependent increases (D) and loci displaying T-bet-dependent decreases (E), as in (B and C). (F) Chromatin accessibility heatmap for all the loci displaying the most significant differential regulation of immune genes (CTL – M/M, adjusted P-value < 1 x 10−5), abolished by WT T-bet (M/M+EV - M/M+WT, adjusted P-value < 1 x 10−5). (G - I) Chromatin accessibility of transcription start site (TSS), proximal promoter and distal enhancer regions of IFNG, TNF and CXCR3. (J) The differential methylation (beta-value) of CpG sites between M/M and CTL or between M/M+EV and M/M+WT is shown. (K - M) CpG methylation status of CpG sites in IFNG (K), ENTPD1 (L) and IL10 (M). See also Table S3 and Supplemental Data S1.

T-bet deficiency impairs NK cell maturation

We then investigated the role of T-bet in the development of leukocyte lineages. Complete blood counts for fresh samples from P showed that the numbers of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes were normal. We studied the PBMC subsets of P after recovery from mycobacterial disease, by mass cytometry (cytometry by time-of-flight, CyTOF). A simultaneous analysis of the expression of 38 different cell surface markers was performed to compare the leukocyte subsets of P and his parents, healthy donors, and patients with IL-12Rβ1 deficiency, the most common genetic etiology of MSMD, as controls (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3A) (Van Gassen et al., 2015; Korsunsky et al., 2019). The frequencies of the plasmacytoid DC (pDC) and conventional DC 1 and 2 (cDC1 and cDC2) subsets were not affected by human T-bet deficiency (Fig. S3B). All major myeloid lineages were normal in P. We therefore focused on the development of lymphoid lineages. Total NK cells (defined as Lin−CD7+CD16+ or CD94+) were present in normal numbers in P (Fig. S3C and D). However, CD16+ and CD56bright NK cells levels were much lower in P than in controls (Fig. 4A and B). Moreover, P had an abnormally high frequency of CD56−CD127− NK cells (Fig. S3D); this NK cell subset has low levels of cytotoxicity and is rare in healthy and normal individuals (Björkström et al., 2010). The frequencies of ILC precursors (ILCPs) and ILC2s in P were similar to those in healthy donors and IL-12Rβ1-deficient patients (Fig. S3E and F). In stringent analyses, ILC1 and ILC3 are too rare for quantification in human peripheral blood (Lim et al., 2017). Thus, human T-bet is required for the correct development or maturation of NK cells, but not monocytes, DCs, ILC2 or ILCP.

Figure 4. Impaired in vivo development of NK, invariant NKT, MAIT, Vδ2+ γδ T, and TH1 cells in T-bet deficiency.

(A) UMAP representation shows immunophenotyping of 40,000 CD45+CD66b−DNA+ live PBMCs from age-matched controls (Age CTL) and M/M, by CyTOF. (B) Frequencies of CD56bright NK cells and CD56dimCD16+ NK cells by CyTOF. (C - E) Percentages of iNKT (C), MAIT (D), and Vδ2+ γδ T cells (E) among live single cells from indicated individuals, including P’s healthy brother (WT/WT), by flow cytometry. (F) viSNE map of 10,000 CD45RA− memory CD4+ T cells from indicated individuals, with expression of CXCR3 and CCR5 shown. (G and H) Frequencies of CCR6− TH1 (CCR6−CXCR3+CCR4−) (G) and CCR6+ TH1* (CCR6+CXCR3+CCR4−) cells (H) among live CD45+CD66b− cells are shown. (I) A bubble graph is presented to show genes for which the proportion of cells displaying expression is altered in the M/M cells in comparison with PBMCs from the TBX21 WT/M father, as a control, by scRNA-seq. The size of the bubble indicates the proportion of cells expressing the gene and the color scale indicates the log2-transformed ratios. The genes highlighted in red were identified as T-bet-regulated by ATAC-seq and/or RNA-seq. LD (low level of detection). ND (not detected). See also Figure S3 - S4 and Supplemental Data S1.

In Fig. 4B – E, G and H, bars represent the mean and the standard error of the mean. Dots represent individual samples or technical replicates. Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests were used for analysis in (C – E). In (C - E), * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, ns = not significant.

Low levels of the iNKT, MAIT, and Vδ2+ γδ T-cell lineages in T-bet deficiency

iNKT, MAIT, and γδ T cells are “innate-like” adaptive T-cell lineages with less T-cell receptor (TCR) diversity than conventional, “purely” adaptive αβ T cells (Chien et al., 2014; Crosby and Kronenberg, 2018; Godfrey et al., 2019). iNKT cells constitute a group of T cells with invariant TCRs combining properties from both T cells and NK cells (Crosby and Kronenberg, 2018). The iNKT cell levels of P were low (present at a level ~27-fold lower than that in controls) (Fig. 4C, Fig. S3G and H). MAIT cells express invariant Vα7.2-Jα33 TCRα restricted by a monomorphic class I-related MHC molecule, along with ligands derived from vitamin B synthesis (Kjer-Nielsen et al., 2012; Xiao and Cai, 2017). P also had a lower frequency of MAIT cells than healthy donors (~15-fold) (Fig. 4D and Fig. S3I). Total γδ T-cell frequency was normal in P. However, the frequency of the Vδ2+ subset, a group of γδ T cells that recognize phosphoantigen (pAgs) (Gu et al., 2018; Harly et al., 2012; Vavassori et al., 2013), was low (~6-fold lower than control levels) in P, whereas the levels of the Vδ1+ subset of γδ T cells seemed to be slightly high (Fig. 4E, Fig. S3J and K). Mild abnormalities of B-cell development and antibody production unrelated to the patient’s mycobacterial disease were observed and will be reported in a separate study (Yang R, in preparation). CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells are the two most prevalent blood lineages of adaptive lymphocytes expressing a highly diverse αβ TCR repertoire. Antigen-driven CD8+ T-cell effector responses and the optimal induction of memory CD8+ T cells in mice are controlled by T-bet (Bettelli et al., 2004; Juedes et al., 2004; Sullivan et al., 2003). In the T-bet-deficient patient, total CD8+ T cells and the composition of naïve, central memory, effector memory and TEMRA cells were normal (Fig. S4A). We further investigated CD8+ T cells in an unbiased manner, by automatic viSNE clustering with a panel of surface markers, including chemokine receptors (Amir el et al., 2013). We found no apparent difference between the memory CD8+ T cells of P and controls. However, a small subset of naïve CD8+ T cells (CD45RA+CD38intCXCR3intCCR6−CCR5−CD27highCD127high) was absent from P (Fig. S4B). Thus, the development of iNKT, MAIT cells, Vδ2+ γδ T cells, and a small subset of naïve CD8+ T cells is impaired in T-bet deficiency.

Selective depletion of CCR6− TH1 cells from CD4+ T cells in T-bet deficiency

Both P and his heterozygous parents had normal distributions of naïve and memory CD4+ T cells (Fig. S4C). We further analyzed individual CD4+ T cell subsets by viSNE clustering on antigen-experienced memory cells. Several memory CD4+ T cell subsets typically present in healthy donors were missing in P. In particular, most of the CXCR3+ cells, corresponding to TH1 cells in humans, and CCR5+ cells (Groom and Luster, 2011; Loetscher et al., 1998; Sallusto et al., 1998), were missing in P (Fig. 4F, Fig. S4D and E). The frequency of classic CXCR3+CCR6− TH1 cells was lower than that in all healthy adult and age-matched donors examined, whereas the frequency of CXCR3+CCR6+ non-classic TH1* cells, which are known to be mostly Mycobacterium-specific, was comparable to that of age-matched healthy donors (Fig. 4G and H). The frequencies of human TH2, TH17, and follicular helper (TFH) cells in peripheral blood were normal (Fig. S4F - H). However, levels of CXCR3+ TFH cells, a group of TH1-biased TFH cells that produce IFN-γ together with IL-21 in germinal centers (Ma et al., 2015; Velu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019a), were low in P (Fig. S4H). CXCR3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), a group of TH1-skewed Tregs (Koch et al., 2009; Levine et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2016) were also present at abnormally low levels, but the proportion of total Tregs was normal (Fig. S4I and J). Thus, human T-bet deficiency selectively impairs development of the classic CXCR3+CCR6− TH1, CXCR3+ TFH, and CXCR3+ Treg CD4+ T-cell subsets, but has no effect on the TFH, TH2, TH17, CCR6+ TH1*, and total Treg subsets, as shown by CyTOF and flow cytometry.

Single-cell transcriptomic profile in vivo is altered by T-bet deficiency

We investigated the development and phenotype of leukocyte subsets in the patient further, by performing single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) with PBMCs from P and his father. The clustering of the various immune subsets yielded eight distinct major subsets: NK cells, pDCs, monocytes, B cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+ CTLs), CD8+ naïve, CD4+ naïve and CD4+ effector/memory T (TEM) cells (Becht et al., 2019). Consistent with the CyTOF results, normal frequencies of pDC, CD8+ CTLs, CD4+ naïve, and TEM cells, were obtained, together with a low frequency of NK cells, on scRNA-seq (Supplemental Data S1). We investigated the transcriptomic changes at single-cell level associated with T-bet deficiency, by filtering to select all genes with expression detected in > 5% of cells in at least one cluster, with at least a four-fold change in expression. We identified 34 genes as differentially regulated in T-bet-deficient cells relative to a heterozygous control. As for the RNA-seq data, some targets with expression known to be dependent on T-bet, including CXCR3 in TEM, CD8+ CTLs, and NK cells, and CCL4 and CCL3 in all cell types, were downregulated in T-bet-deficient cells (Fig. 4I). The expression of XCL1, STAT4, SOX4, LMNA and ANXA1 was also impaired in at least one subset of T-bet-deficient cells (Fig. 4I). In humans and mice, XCL1, STAT4, SOX4, LMNA and ANXA1 are known to be involved in TH1 immunity (Dorner et al., 2002, 2003, 2004; Gavins and Hickey, 2012; Kroczek and Henn, 2012; Nishikomori et al., 2002; Thieu et al., 2008; Toribio-Fernández et al., 2018; Yoshitomi et al., 2018). NKG7 is involved in the initiation of human TH1 commitment and its genetic locus is tightly occupied by T-bet (Jenner et al., 2009; Kanhere et al., 2012; Lund et al., 2005). NKG7 expression in naive CD4+, CD8+ and B cells was dependent on functional T-bet, whereas PRDM1 was downregulated in CD4+ T and CD8+ CTLs cells from P (Fig. 4I). The IFNG gene was weakly expressed across lymphocyte populations, as shown by scRNAseq, and its expression did not seem to be dependent on T-bet in basal conditions (data not shown). In addition, the expression of several genes not previously linked to T-bet was also altered in at least one cell subset in P (Fig. 4I). Thus, in addition to CXCR3, NKG7, CCL3 and CCL4, which were weakly expressed in at least one leukocyte subset from this patient with human T-bet deficiency, consistent with the findings of RNA-seq and omni-ATAC-seq, the expression of a set of previously unknown target genes in immune subsets is also controlled by T-bet (Fig. 4I).

Impaired IFN-γ production by NK, MAIT, Vδ2+ γδ T, and CD4+ T cells

Human IFN-γ is essential for antimycobacterial immunity, as all 31 known genetic etiologies of MSMD affect IFN-γ-dependent immunity. The in vivo development of NK, iNKT, MAIT, Vδ2+ γδ T, and classic TH1 cells was found to be impaired in P, but it remained possible that the IFN-γ production capacity of the remaining lymphocytes could compensate, thereby contributing to antimycobacterial immunity. We assessed the response of P’s PBMCs to ex vivo stimulation with P/I. They secreted significantly less IFN-γ secretion than control cells (Fig. 5A). The frequencies of IFN-γ- or TNF-α-producing total lymphocytes were also low in P (Fig. 5B - D). We assessed the IFN-γ and TNF-α production of lymphocyte subsets by spectral flow cytometry (Fig. S5A). Upon P/I stimulation, the frequencies of IFN-γ- or TNF-α-producing CD56+ NK cells were low in P (Fig. 5E, Fig. S5B and C). We then assessed of the response of P’s NK cells to ex vivo stimulation with IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18. Total NK cells from P displayed impaired degranulation, with low levels of CD107a expression, and almost no IFN-γ production (Fig. 5F, Fig. S5D and E). T-bet deficiency not only reduced the overall frequencies of iNKT, MAIT, and Vδ2+ γδ T cells, but also compromised the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α ex vivo by the residual activated iNKT, MAIT, and Vδ2+ γδ T cells detected in P (Fig. 5G - K, Fig. S5F). Despite an increase in the frequency of Vδ1+ γδ T cells in vivo, the levels of IFN-γ- or TNF-α-producing-Vδ1+ γδ T cells were also low ex vivo (Fig. 5G, Fig. 5L and M). By contrast, we observed no difference in IFN-γ and TNF-α production by Vδ1−Vδ2− γδ T cells between P and controls (Fig. 5G, Fig. S5G and H). IFN-γ-producing cells from the various lymphocyte subsets examined in healthy donors expressed high levels of T-bet, but all the residual IFN-γ-producing cells from the various subsets in P tested negative for T-bet (Fig. 5G). We also analyzed the response of αβ T cells to P/I. CD8+ T cells secrete substantial amounts of IFN-γ upon microbial challenge (Schoenborn and Wilson, 2007). The frequencies of CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ or TNF-α in response to P/I did not differ between P and age-matched healthy donors (Fig. S5I and J). By contrast, the frequencies of IFN-γ- or TNF-α-producing CD4+ T cells were slightly low in P (Fig. 5N and O). Thus, among the residual circulating lymphocytes of P, NK, iNKT, MAIT, Vδ2+, Vδ1+ γδ T, and CD4+ T cells had impaired IFN-γ production ex vivo in response to stimulation with IL-12, IL-15, IL-18 or P/I, whereas Vδ1−Vδ2− γδ and CD8+ αβ T cells did not.

Figure 5. Impaired IFN-γ ex vivo production from the remaining lymphocytes of the T-bet-deficient patient.

(A) IFN-γ production in culture supernatants of PBMCs from indicated individuals in response to stimulation with P/I is shown. (B) Dot-plots showing the expression of T-bet and IFN-γ in total live lymphocytes as in (A). (C and D) Frequency of IFN-γ (C) or TNF-α-producing (D) cells in response to P/I as in (B). (E) Frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells among NK cells in response to P/I. (F) PBMCs were stimulated with IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18. The expression of CD107a and IFN-γ among NK cells were assessed by flow cytometry. (G) Dot-plots showing the expression of T-bet and IFN-γ by indicated subsets in response to P/I. (H - O) Frequency of IFN-γ- (H, J, L, N) or TNF-α (I, K, M, O)-producing cells among MAIT cells, Vδ2+ γδ T cells, V1+ γδ T cells and CD4+ T cells in response to P/I. (P – U) FACS sorted naïve and memory CD4+ T cells were activated/expanded. The production of IFN-γ was assessed intracellularly (P) and in culture supernatants (Q). The production of TNF-α was assessed intracellularly (R) and in culture supernatants (S). The production of IL-22 (T) and IL-17A (U) was assessed in culture supernatants. (V - Y) Naïve CD4+ T cells were subjected to activation under TH0 or TH1 conditions. The production of IFN-γ (V and W) and TNF-α (X and Y) was assessed. (Z) Memory CD4+ T cells were activated under TH0 or TH1 conditions. The production of IFN-γ and TNF-α was assessed. See also Figure S5.

In Fig. 5A, C – F, H - Z, bars represent the mean and the standard error of the mean. Dots represent individual samples or technical replicates. Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests were used for analysis in (A, C – E, H - O). In (A, C – E, H - O), * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p <0.001, **** p < 0.0001, ns = not significant.

Selective impairment of IFN-γ production by TH cells in T-bet deficiency

T-bet was first discovered and has been most extensively studied in CD4+ T cells in the context of mouse TH1 cells (Szabo et al., 2000, 2002). This discovery, together with that of GATA3 (Zheng and Flavell, 1997), revealed the molecular determinism of TH1/TH2 CD4+ T-cell differentiation and paved the way for an understanding of TH17, iTreg, TH22, TFH, and TH9 cell lineage determination (Finotto et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2010). We therefore investigated the impact of T-bet deficiency on primary CD4+ T cells. IFN-γ production by memory CD4+ T cells was impaired by T-bet deficiency (Fig. 5P and Q). Another TH1 cytokine, TNF-α, was also produced in smaller amounts by memory CD4+ T cells from P than by those of most of the healthy donors (Fig. 5R and S). By contrast, the memory CD4+ T cells of P produced larger amounts of the TH17 effector cytokines IL-17A and IL-22 than did those of healthy donors (Fig. 5T and U, Fig. S5K). Unlike previous studies (Gökmen et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2019b), we found that T-bet deficiency had no effect on IL-9 production ex vivo (Fig. S5L and M). Surprisingly, ex vivo TH2 cytokines from memory CD4+ T cells were also not affected by human T-bet deficiency (Fig. S5N - Q). P’s memory CD4+ cells produced less IL-21 ex vivo than the memory CD4+ cells of most of the healthy donors (Fig. S5R). We then investigated the role of T-bet in human TH cell differentiation in vitro. Naïve CD4+ T cells from P or healthy donors were allowed to differentiate in TH0, TH1, TH2, TH9, or TH17 conditions. The induction of IFN-γ production in naïve CD4+ T cells was abolished by T-bet deficiency under TH1 conditions (Fig. 5V and W). Similarly, T-bet-deficient naïve CD4+ T cells produced less TNF-α than the corresponding cells from most controls (Fig. 5X and Y). Furthermore, the induction of IL-9 under various conditions in vitro was weaker in naïve CD4+ T cells from P than in the corresponding cells from most controls (Fig. S5S and T). In vitro-induced TH2 cells from P produced more IL-10, but not IL-13, than control cells (Fig. S5U and V). Even memory CD4+ T cells from P displayed impaired IFN-γ and TNF-α production under TH1 polarizing conditions (Fig. 5Z). Thus, AR T-bet deficiency leads not only to defective IFN-γ and TNF-α production ex vivo and in vitro, but also to a moderate upregulation of the production of IL-17A and IL-22, two cytokines characteristic of TH17 cells (Lazarevic et al., 2011).

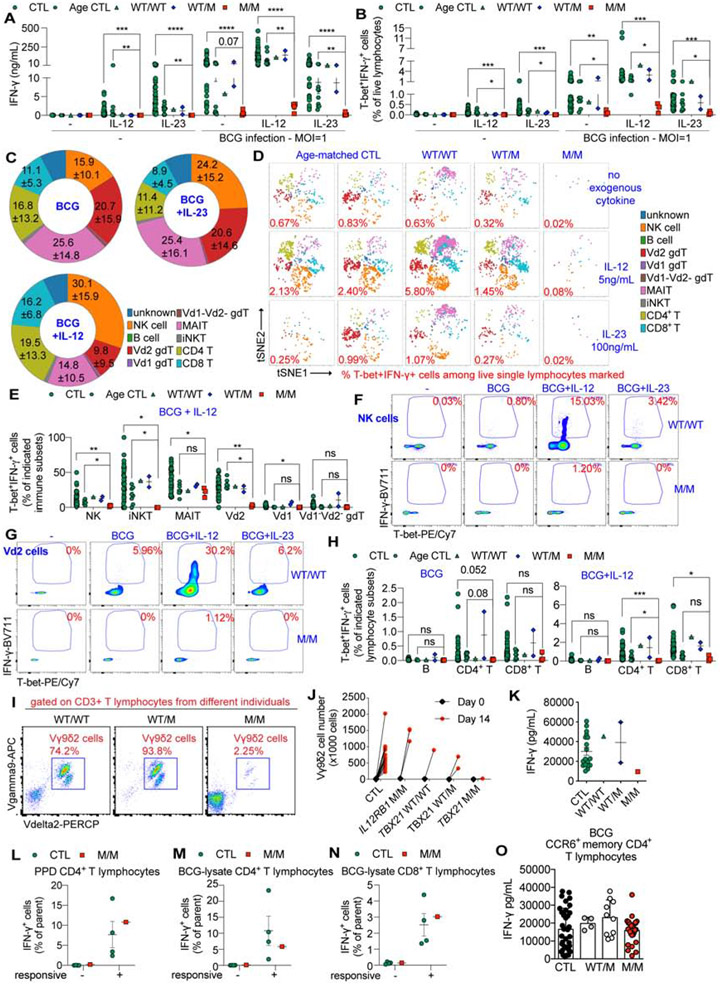

Poor cellular response to BCG infection in vitro in T-bet deficiency

We investigated the molecular and cellular basis of BCG disease in P, by identifying the leukocyte subsets producing the largest amounts of IFN-γ in a T-bet-dependent manner during acute BCG infection in vitro. The infection of PBMCs with BCG induced IFN-γ production, which was further increased by stimulation with exogenous IL-12 (Fig. 6A). PBMCs from P had low levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α production, but the level of IL-5 production in response to BCG infection was higher than that in most of the controls (Fig. 6A, Fig. S6A and B). Almost all the IFN-γ-producing cells in controls had high levels of T-bet expression (Fig. S6C). Thus, T-bet+ IFN-γ+ double-positive (DP) cells were the major Mycobacterium-responsive cells, with a function potentially dependent on T-bet. However, T-bet+ IFN-γ DP cell levels were low during acute infection in P (Fig. 6B, Fig. S6C). T-bet+ IFN-γ DP cells induced by exogenous IL-12 alone comprised predominantly NK cells, whereas those induced by IL-23 alone also contained a large proportion of MAIT cells, in addition to NK cells (Fig. S6D). Among the T-bet+ IFN-γ+ cells of healthy donors, NK, MAIT, Vδ2+ γδ T, CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells were the dominant responders during BCG infection, whereas iNKT, Vδ1+ γδ T, Vδ1−Vδ2− γδ T and B cells were minority responders (Fig. 6C and D). However, these subsets of T-bet+ IFN-γ+ cells were almost entirely depleted from P’s PBMCs following BCG infection (Fig. 6D). We then investigated each leukocyte subset separately (Supplemental Data S1). Fewer than 2% of Vδ1+ γδ T cells, Vδ1−Vδ2− γδ T cells, B cells, CD4+ or CD8+ αβ T cells became T-bet+ IFN-γ+ during BCG infection. However, among innate or innate-like lymphocytes, up to 10% of NK cells, 40% of iNKT, and 50% of Vδ2+ γδ T cells from healthy donors, but not from P, became T-bet+ IFN-γ+ in response to BCG infection, and the frequency of these cells was further increased by exogenous IL-12 (Fig. 6E - G, Fig. S6E and F). Up to 50% of MAIT cells became T-bet+ IFN-γ+ during BCG infection, but no difference was observed between age-matched healthy donors and P (Fig. 6E and Fig. S6E). Upon acute BCG infection in vitro, despite a less robust activation of CD4+ T cells than of innate or innate-like lymphocytes, the frequency of T-bet+ IFN-γ+ cells was low among CD4+ but not among CD8+ αβ T cells of P (Fig. 6H, Fig. S6G and H). Thus, the IFN-γ production controlled by T-bet during acute BCG infection in vitro takes place mostly in NK, iNKT, Vδ2+ γδ T and CD4+ αβ T cells, but not in Vδ1+ γδ T cells, Vδ1−Vδ2− γδ T cells, or CD8+ αβ T cells. The development of MAIT cells is also dependent on T-bet, whereas the IFN-γ production of these cells during BCG infection is not. These experimental findings in vitro do not exclude a contribution of other subsets in vivo. NK, iNKT, MAIT, and Vδ2+ γδ T cells responded robustly to acute BCG infection in vitro, but these subsets were absent or functionally deficient in the patient with inherited T-bet deficiency.

Figure 6. T-bet deficiency leads to defective NK, iNKT and Vδ2+ γδT cells, resulting in susceptibility to mycobacteria.

(A) IFN-γ secretion by PBMCs from indicated individuals stimulated with and without live M. bovis BCG in the presence and absence of IL-12 and IL-23. (B) Percentages of T-bet+ IFN-γ+ double-positive (DP) cells in the indicated samples, cultured as in (A). (C) Percentages of indicated immune subsets among the DP cells of both CTL and Age CTL individuals. (D) viSNE plots showing different clusters of immune cells among DP cells. (E) Percentages of DP cells within each immune subset, as indicated. (F and G) Dot-plots showing the expression of T-bet and IFN-γ in NK (F) and Vδ2+ γδ T cells (G), cultured as in (A). (H) Percentages of DP cells within each indicated adaptive immune subset. (I and J) PBMCs from indicated individuals were stimulated with lysates of M. bovis BCG (BCG-lysates) for 14 days. Dot plots of Vγ9δ2 γδT cells (I) and the total number of Vγ9δ2 γδT cells (J) are shown. (K) The level of IFN-γ in culture supernatants from (J) is shown. (L - N) The intracellular IFN-γ production of antigen-specific CD4+ or CD8+ T cells expanded from PPD or BCG-lysates was measured. The percentages of IFN-γ-producing cells among PPD-responsive CD4+ T (L), BCG-lysate-responsive CD4+ (M) and CD8+ T (N) cells are shown. (O) Memory CCR6+CD4+ T-cell clones responding to the peptide pool from M. bovis BCG were identified. IFN-γ production in culture supernatants from these BCG-specific clones was shown. See also Figure S6, Table S4, and Supplemental Data S1.

In Fig. 6A, B, E, H, K, L, M and N, bars represent the mean and the standard error of the mean. Dots represent individual samples and technical replicates. In (O), bars represent the mean and the standard deviation. Dots represent individual T-cell clones. In (C), the numbers indicate the mean and the standard error of the mean. Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests were used for analysis in (A, B, E and H). In (A, B, E and H), * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, and ns = not significant.

Defective prolonged anti-BCG immunity mediated by Vδ2+ γδ T cells

The stimulation of PBMCs in vitro with live BCG involves both antigens specifically recognized by Mycobacterium-specific cognate αβ and γδ T cells and many other stimuli. BCG infection in vitro mimics acute infection in vivo, but may not be robust enough for investigations of the antigen-specific adaptive immune response, particularly as concerns prolonged adaptive immunity. We therefore studied Vδ2+ γδ T cells and CD4+ αβ T cells, two adaptive immune lymphocyte subsets that produced substantial amounts of IFN-γ during BCG infection in vitro and are known to function in an antigen-specific manner. In PBMCs from healthy donors, Vδ2+ γδ T cells responded most robustly during BCG infection (Fig. 6E). Vδ2+ γδ T cells, a major subset of γδ T cells recognizing pAg from microbial sources (Gu et al., 2018; Harly et al., 2012; Vavassori et al., 2013), are also known to play an essential role in the recall response to mycobacterial re-infection in humans and non-human primates (Chen, 2005; Shen et al., 2002). Vδ2+ γδ T cells proliferate vigorously in response to mycobacterial infection in vivo and can expand robustly in response to pAg-rich lysates of mycobacterial species in vitro (Hoft et al., 1998; Modlin et al., 1989; Panchamoorthy et al., 1991; Parker et al., 1990; Tsukaguchi et al., 1995). We investigated whether the function of Vδ2+ γδ T cells was affected in the patient with T-bet deficiency, as these cells represented a small, but important proportion (~ 0.2%) of P’s peripheral lymphocytes. The populations of Vδ2+ T cells from all controls and relatives of P expanded vigorously following prolonged stimulation with BCG lysates. By contrast, no such expansion was observed for T-bet-deficient Vδ2+ T cells (Fig. 6I and J, Fig. S6I). After two weeks of expansion, the levels of IFN-γ production by T-bet-deficient cells were lower than those for healthy donors’ cells (Fig. 6K).

Redundant role of T-bet in IFN-γ production by BCG-specific cognate TH1* cells

IFN-γ production by CD4+ αβ T cells upon BCG infection ex vivo was subtly affected by T-bet deficiency, but it remains unclear whether there is a difference in the mycobacterial antigen-specific CD4+ αβ T-cell response. It also remains unclear whether the memory adaptive immunity to mycobacteria elicited by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells is dependent on T-bet. We addressed both these unresolved issues by analyzing Mycobacterium-responsive CD4+ T cells expanded through prolonged stimulation with BCG-lysates or tuberculin purified protein derivative (PPD) (Supplemental Data S1). Like those of BCG-vaccinated healthy donors, P’s CD4+ T cells proliferated equally well in response to both BCG-lysates and PPD (Supplemental Data S1). No difference in IFN-γ production from PPD-responsive CD4+ T cells was observed between healthy donors and P (Fig. 6L and Fig. S6J). Unlike PPD, which activated only CD4+ T cells, BCG-lysates activated both CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, albeit to a lesser extent (Supplemental Data S1). Like PPD stimulation, IFN-γ production from both BCG-lysate-responsive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was similar between controls and P (Fig. 6M and N, Fig. S6K and L). We confirmed these findings by screening antigen-reactive T-cell libraries established from the CD4+CCR6− (containing classic TH1 cells) and CD4+CCR6+ (containing TH1* Mycobacterium-responsive cells) memory subsets (Geiger et al., 2009). Consistent with our in vivo findings, the T cells in the CD4+CCR6− and CD4+CCR6+ libraries had low levels of CXCR3 or IFN-γ (Supplemental Data S1). P’s CD4+CCR6+ T-cell library responded robustly to BCG, tetanus toxoid and C. albicans, and his CD4+CCR6− T-cell library responded normally to influenza virus, CMV, and EBV. Despite intact proliferation, IFN-γ production from T-bet-deficient T cells responding to influenza virus, EBV, tetanus toxoid, and C. albicans was weak. However, P’s CCR6+ T cells, consisting almost entirely of Mycobacterium-specific memory TH1* cells (Acosta-Rodriguez et al., 2007; Becattini et al., 2015), proliferated robustly in response to BCG peptides. Moreover, their IFN-γ production was normal, and their levels of IL-10 production were slightly higher (Fig. 6O and Supplemental Data S1). The normal levels of IFN-γ production could not be attributed to cells with a revertant genotype, as reported in other T-cell primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs) (Davis et al., 2008; Revy et al., 2019), because the IFN-γ+ BCG-specific T-cell clones still carried the TBX21 indel variant. Thus, the prolonged immunity to BCG infection mediated by Vδ2+ γδ T and memory αβ T cells was divergently controlled by T-bet, as T-bet was required for the generation of long-term immunity due to Vδ2+ γδ T cells, but redundant for IFN-γ production by BCG-specific cognate CD4+ TH1* cells or Mycobacterium-responsive CD8+ αβ T cells (Table S4).

Discussion

We report here the identification and study of the first patient discovered to have inherited, complete T-bet deficiency resulting clinically in MSMD. Key observations made in T-bet-deficient mice were validated in this human patient with T-bet deficiency: 1) the development of TH1 cells and their production of effector cytokines, including IFN-γ in particular, requires T-bet (Szabo et al., 2000, 2002); 2) the development of NK and iNKT cells is dependent on T-bet (Townsend et al., 2004); and 3) the regulation of T-bet-dependent targets, including CXCR3, TNF and IFNG, involves both direct transactivation and epigenetic modulation (Miller and Weinmann, 2010). Accordingly, T-bet-deficient mice are highly vulnerable to mycobacteria, including M. tuberculosis and M. avium (Matsuyama et al., 2014; Sullivan et al., 2005), like mice deficient for other genes that govern IFN-γ immunity (Casanova, 1999). By contrast, despite the requirement of T-bet for immunity to a broad spectrum of pathogens following experimental inoculation in mice (Bakshi et al., 2006; Harms Pritchard et al., 2015; Hultgren et al., 2004; Kao et al., 2011; Lebrun et al., 2015; Oakley et al., 2013; Ravindran et al., 2005; Rosas et al., 2006; Svensson et al., 2005; Szabo et al., 2002), the only apparent infectious phenotype of the T-bet-deficient patient is MSMD. Our study provides compelling evidence that inherited T-bet deficiency is a genetic etiology of MSMD due to the disruption of IFN-γ immunity (Casanova et al., 2014). This experiment of nature suggests that T-bet is required for protective immunity to intramacrophagic mycobacteria but largely redundant for immunity to most intracellular pathogens, including viruses in particular. This is at odds with findings in mice, but consistent with other genetic etiologies of MSMD, all of which are inborn errors of IFN-γ immunity (Bustamante, 2020; Kerner et al., 2020). Our observation further suggests that the functions of T-bet unrelated to IFN-γ are redundant in humans. The identification of additional T-bet-deficient patients is required to draw firm conclusions. However, it is striking that humans genetically deprived of key immunological molecules other than T-bet or IFN-γ often show a much greater redundancy than the corresponding mutant mice (Casanova and Abel, 2004, 2018).

Our study also suggests unexpected immunological abnormalities not documented in T-bet-deficient mice that also contribute to the development of MSMD: 1) T-bet was apparently required for the optimal development of two innate-like adaptive lineages of immune cells, MAIT and Vδ2+ γδ T cells; 2) T-bet was also apparently required for the optimal production of IFN-γ by the few NK, iNKT, MAIT, and Vδ2+ γδ T lymphocytes that were able to develop (Bettelli et al., 2004; Daussy et al., 2014; Garrido-Mesa et al., 2019; Intlekofer et al., 2007; Lugo-Villarino et al., 2003; Pearce et al., 2003; Rankin et al., 2013; Sullivan et al., 2003; Tang et al., 2010). Unexpectedly, IFN-γ production by cognate purely adaptive Mycobacterium-specific TH1* CD4+ T cells, and by PPD-, or BCG-lysate-responsive CD4+ or CD8+ αβ T cells, was unaffected by T-bet deficiency. The compensatory mechanisms underlying intact IFN-γ production by these antigen-specific CD4+ T cells remain to be discovered. Taken together, impaired IFN-γ production by NK and iNKT cells, as in mice, and by MAIT and Vδ2+ γδ T cells, as shown here, accounts for MSMD in this patient with T-bet deficiency, despite normal TH1* development and function. By contrast, inborn errors of immunity that disrupt IFN-γ production by the selective depletion of NK, iNKT, CD4+, or CD8+ αβ T cells do not underlie mycobacterial disease, because of the compensation provided by other subsets. Conversely, the loss of all T-cell subsets in SCID patients does result in predisposition to mycobacterial disease. Interestingly, a different combination of deficits accounts for MSMD in patients with RORγT deficiency, who lack iNKT and MAIT cells and whose γδ T and TH1* cells do not produce IFN-γ, and whose NK cells are unable to compensate (Okada et al., 2015). T-bet and RORγT deficiencies are characterized by iNKT, MAIT, and γδ T-cell deficiencies, whereas an NK deficit is observed only in T-bet deficiency and a deficit of TH1* cells is observed only in RORγT deficiency. We found that human T-bet was essential for both innate (NK cells) and innate-like (iNKT, MAIT, and Vδ2+ γδ T cells) adaptive immunity to mycobacteria, but, surprisingly, redundant for classical, purely adaptive immunity (CD4+ TH1* and CD8+ αβ T cells) to mycobacteria.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Jean-Laurent Casanova (casanova@mail.rockefeller.edu).

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement with Inserm or the Rockefeller University.

Data and Code Availability

The whole-exome sequencing, RNA-seq and omni-ATAC-seq datasets generated during this study are available at the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (PRJNA641463). The scRNA-seq datasets generated during this study are available at the EGA European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGAS00001004504). This study did not generate any unique code. Any other piece of data will be available upon reasonable request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Human subjects

The patient and the relatives studied here were living in and followed up in Morocco. The study was approved by and performed in accordance with the requirements of the institutional ethics committee of Necker Hospital for Sick Children, Paris, France, and the Rockefeller University, New York, USA. Informed consent was obtained for the patient, his relatives, and healthy control volunteers enrolled in the study. This study was also approved by the Sydney Local Health District RPAH Zone Human Research Ethics Committee and Research Governance Office, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Camperdown, New South Wales, Australia (protocol X16-0210/LNR/16/RPAH/257). Written informed consent was obtained from participants or their guardians. Informed consent from participants in Switzerland was approved by the local ethical committee (CE3428 authorized by Comitato Etico Cantonale, www.ti.ch/CE). Experiments using samples from human subjects were conducted in the United States, France, Australia and Switzerland, in accordance with local regulations and with the approval of the IRBs of corresponding institutions. Plasma samples from unrelated healthy subjects used as controls for antibody profiling by phage immunoprecipitation-sequencing (PhIP-Seq) were collected at Sidra Medicine in accordance with a study protocol approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of Sidra Medicine.

Case report of the patient (P) - P was born in 2015 to Moroccan first-cousin parents. He was vaccinated with BCG at the age of three months. After vaccination, he developed fever and left axillary lymphadenopathy accompanied by a cutaneous eruption. He received amoxicillin for 10 days, resulting in clinical improvement. At the age of six months, he was hospitalized for persistent fever, weight loss, cutaneous erythema, ear drainage and persistent oral thrush. Axillary adenopathy was present, with fistulation associated with hepatosplenomegaly and multiple abdominal adenopathies. The patient was treated with four antimycobacterial drugs; he displayed a good clinical response to 18 months of treatment and has been off antibiotics for 15 months. He was also found to have mild cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia at the time (CMV PCR 3.74 log/mL, threshold < 2.4 log/mL), and was treated with ganciclovir. Serological PCR tests for CMV were negative at the age of two years, but weakly positive at the age of three years (IgM anti-CMV weakly positive, CMV PCR 3.62 log/mL, threshold < 2.4 log/mL). However, the patient showed no characteristic features of CMV infection and did not present clinically confirmed CMV disease. At the age of 11 months, he was hospitalized for four days due to airway hyperresponsiveness requiring treatment with inhaled steroids and albuterol. The patient had a high blood eosinophil count, documented since the age of since months (1,460/mm3). By the age of 17 months, he had persistent upper respiratory tract inflammation, with manifestations of persistent rhinorrhea, difficult respiration, wheezing and coughing that improved on treatment with oral steroid and salbutamol. The patient has since been treated with inhaled steroids for persistent upper respiratory tract inflammation. The clinical manifestations affecting the upper respiratory tract persisted at the age of three years. No trigger was identified for these symptoms and signs, which were not triggered by exercise, activity, feeding or parasitic infections. A serum IgE allergen screen was negative for more than 250 allergens tested. The patient requires inhaled steroid therapy (fluticasone spray) every morning and evening. He also frequently visits the emergency room, and is hospitalized about once per month for exacerbations requiring oral steroid (beta-methasone) and inhaled salbutamol. The patient has been vaccinated for Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Haemophilus B, for all of which positive serum IgG result have been obtained. He also tested positive for anti-HSV-1 IgG, anti-EBV IgG, anti-CMV IgG, anti-mumps IgG and anti-parainfluenza IgG in clinical serology examinations. No anatomical abnormalities of the airways were noted. The patient has a brother who is healthy, with no history of severe infectious disease or airway hyperresponsiveness. The genetic cause of the patient’s airway hyperresponsiveness will be studied separately.

Cell lines

HEK293T and Phoenix A retroviral packaging cells were cultured in IMDM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). B cells from the patient or controls were immortalized in-house with Epstein Barr virus (EBV-B cells) and cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS. NK-92 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 200 U/mL recombinant proleukin IL-2 (PROMETHEUS). Herpesvirus saimiri-transformed T (HVS-T) cells were generated with either H. saimiri strain C488 for transformation or the TERT transformation system (Wang et al., 2016). HVS-T cells were cultured in Panserin/RPMI 1640 (ratio 1:1) supplemented with 20% FBS, L-glutamine, gentamycin and 20 U/mL human rIL-2 (Roche). Isolated CD4+ T cells were cultured in X-vivo 15/gentamycin/L-glutamine (Lonza) supplemented with human AB Serum (GemCell). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS for stimulation experiments. All cell lines used tested negative for mycoplasma. HEK293T, Phoenix A and NK-92 cells were purchased from the ATCC.

METHOD DETAILS

Phage immunoprecipitation-sequencing (PhIP-Seq)

Patient serum and control samples were analyzed in duplicate by phage immunoprecipitation-sequencing (Hernandez et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2015). We used 10% liquid IVIg from pooled human plasma (Privigen® CSL Behring AG), human IgG-depleted serum (Supplier No HPLASERGFA5ML, Molecular Innovations, Inc.), and plasma samples from two unrelated healthy adult subjects and one unrelated healthy three-year-old boy for comparison. PhIP-Seq was carried out as previously described (Xu et al., 2015), but with the following modifications. We determined levels of total IgG in the serum or plasma samples with the Human IgG total ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated diluted samples containing approximately 4 μg of total IgG at 4°C overnight with 2 × 1010 plaque-forming units (PFUs) of a modified version of the original VirScan phage library (Xu et al., 2015). Specifically, the T7 phage library used here for peptide display contained the same viral peptides as the original VirScan phage library plus additional peptides derived from protein sequences of various microbial B-cell antigens available from the IEDB (www.iedb.org). For the computational analysis and background correction, we also sequenced the phage library before (input library sample) and after immunoprecipitation with beads alone (mock IP). We performed a number (n = 46) pf technical repeats. Single-end sequencing was performed with the NextSeq500 system (Illumina), to generate approximately two million reads per sample and ~20 million reads for the input library samples. As previously described (Xu et al., 2015), reads were mapped onto the original library sequences with Bowtie 2 and read counts were adjusted according to library size. A zero-inflated generalized Poisson model was used to estimate the p-values, to reflect enrichment for each of the peptides. We considered peptides to be significantly enriched only if the −log10 p-value was at least 2.3 in all replicates. Species-specific score values were computed for each serum or plasma sample, by counting the significantly enriched peptides for a given species with less than a continuous seven-residue subsequence, the estimated size of a linear epitope, in common. We corrected for unspecific binding of peptides to the capture matrix, by also calculating species-specific background score values by counting the peptides displaying enrichment to the 90th percentile of the mock IP samples. These peptides were used for background subtraction.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES), genotyping and genome-wide linkage (GWL) analysis

All four members of the family tested were subjected to genomic DNA extraction followed by WES. Exome capture was performed with the SureSelect Human All Exon V4+UTR and SureSelect Human All Exon V6 (Agilent Technologies). Paired-end sequencing was performed on a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina), generating 100-base reads. We used the Genome Analysis Software Kit (GATK) (version 3.4–46) best-practice pipeline to analyze our WES data (Li et al., 2009; McKenna et al., 2010). Reads were aligned with the human reference genome hg19, with BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009). PCR duplicates were removed with Picard tools (picard.sourceforge.net/). The GATK base quality score recalibrator was applied to correct sequencing artifacts. The GATK HaplotypeCaller was used to identify variant calls (Depristo et al., 2011; McKenna et al., 2010) Variants were annotated with SnpEff (snpeff. sourceforge.net/) (Cingolani et al., 2012).

All four members of the family were genotyped with Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 data. Genotype calling was achieved with the Affymetrix Power Tools Software Package (https://www.affymetrix.com/support/developer/powertools/changelog/index.html). Parametric multipoint linkage analysis was performed with MERLIN 1.1.2 software (Abecasis et al., 2002), assuming autosomal recessive inheritance with complete penetrance and a damaging allele frequency of 1 x 10−4. Allele frequencies were estimated for 562,685 SNP markers, with family founders and HapMap CEU trios. Markers were clustered using an r2 threshold (--rsq parameter) of 0.4. The genetic variant of interest was confirmed by PCR amplification of the region (forward primer: 5’- gtgaggactacgcgctacc-3’, and reverse primer: 5’-cagaagcattgtcgagccag-3’) followed by Sanger sequencing.

cDNA sequencing

We used cDNA sequencing to characterize the consequences of the patients’ variant. In brief, total RNA was extracted from EBV-B cells or PBMCs from the patient and healthy donors (Qiagen). We synthesized cDNA from mRNA, using Superscript III (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A region spanning the mutation site was amplified by PCR with the forward (5’- tagaagccaggcgtcagagc-3’) and reverse R4 (5’- ctcggcattctggtaggcag-3’), R5 (5’- gcaatgaactgggtttcttgg-3’), or R6 (5’- gactcaaagttctcccggaatcc-3’) primers. PCR amplicons were sequenced with the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Alternatively, cDNA generated from patient or control PBMCs was amplified by PCR with the forward primer 5’- tctacactctttccctacacgacgctcttccgatctgtgaggactacgcgctacc-3’ and reverse primer 5’- gtgactggagttcagacgtgtgctcttccgatctgcaatgaactgggtttcttgg-3’, to amplify a region spanning the mutation in a first round of PCR. A second round of PCR was then performed on the PCR products from the first PCR as a template. We used the forward primer 5’- aatgatacggcgaccaccgagatctacactctttccctacacgac -3’ and the reverse primers 5’- caagcagaagacggcatacgagatcgtattcggtgactggagttcagacgtgtg -3’, 5’-caagcagaagacggcatacgagatctcctagagtgactggagttcagacgtgtg -3’, and 5’- caagcagaagacggcatacgagattagttgcggtgactggagttcagacgtgtg -3’, to barcode two healthy control cDNAs and the patient’s cDNA. Adaptor and barcoded PCR amplicons were mixed and purified, and used for next-generation sequencing by Nano Format 350 paired-end MiSeq sequencing (illumina). We aligned MiSeq data to the reference genome with RNA-STAR aligner (Afgan et al., 2016; Dobin et al., 2013). The aligned sequencing data were then viewed with Integrative Genome Browser (Robinson et al., 2011).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells with the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) or the Quick-RNA kit (Zymo Research). Reverse transcription was performed with the Superscript III enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Messenger RNAs were quantified with the cDNA as a template and the TBX21 (Probe 1: Hs00894393 and Probe 2: Hs00894391), IFNG (Hs99999041), TNF (Hs01113624), IL5 (Hs01548712) (Thermo Fisher), GUSB (Thermo Fisher) probes.

T-bet/TBX21 overexpression

A wild-type (WT) TBX21 plasmid with a pCMV6 backbone was purchased from Origene (RC207902). The genetic variants of TBX21 studied here, and the variants described in gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) or in our in-house database were introduced into pCMV6-WT TBX21 by site-directed mutagenesis PCR with the CloneAmp HiFi PCR Premix (Takara Bio). TBX21 WT plasmids or plasmids containing variants were used to transfect HEK293T cells in the presence of Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to achieve overexpression. The WT or mutant (Mut) TBX21 was overexpressed in in vitro-expanded T cells, HVS-T cells, or NK-92 cells, as previously described (Martínez-Barricarte et al., 2016). In brief, the TBX21 plasmid was subcloned into pLZRSire-ΔNGFR (Addgene) (Van De Vosse et al., 2009). We then used pLZRS containing the WT or Mut TBX21 to transfect Phoenix A cells, and retroviruses were produced and concentrated with Retro-X (Takara Bio). Concentrated retrovirus preparations were used for retroviral transduction.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were solubilized in RIPA buffer containing 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS and 150 mM NaCl supplemented with protease-inhibitor cocktail (Complete mini, Roche). Alternatively, nuclear proteins from HEK293T transfectants were purified with the NE-PER Nuclear Extraction kit in accordance with the manufacturer’s procedures (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were quantified with the Bradford assay. Equal amounts of lysate (5 μg to 50 μg of) were mixed with SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5min at 95°C before being subjected to electrophoresis in 12% acrylamide SDS-PAGE gels. The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting: mouse anti-human T-bet 4B10 monoclonal Ab (BioxCell), rabbit anti-human T-bet polyclonal Ab (Proteintech), anti-Flag-M2 HRP-conjugated Ab (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-α-tubulin HRP-conjugated Ab (Proteintech), anti-lamin A/C Ab (Santa Cruz), anti-GAPDH HRP-conjugated Ab (Santa Cruz), anti-STAT1 monoclonal Ab (BD Biosciences), sheep ECL anti-mouse IgG HRP-conjugated Ab (GE Healthcare), and ECL anti-rabbit IgG HRP-conjugated Ab (GE Healthcare).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

HEK293T cells were transfected with empty plasmid (EV), WT or mutant TBX21 pCMV6 plasmids. After 2 days, nuclear extracts were obtained from the cells with the NE-PER Nuclear Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). EMSA was performed as previously described (Liu et al., 2011). In brief, 32P was used to label consensus T-box responsive element (TBRE) duplexes of DNA oligos (WT oligo: 5’-gataatttcacacctaggtgtgaaatt-3’, Mut Oligo as control: 5’-gataatttcacgtctaggtacgaaatt-3’ and 5’-gataatttcgtacctagacgtgaaatt-3’). Unlabeled WT TBRE duplex was used as non-radioactive competitive probe. We mixed 10 μg of nuclear extract from each condition or 80 μg (8x) of nuclear extract from Mut TBX21 transfectants with or without unlabeled probe, 2 μg mouse IgG1 control (BioxCell) or 2 μg mouse anti-T-bet 4B10 monoclonal Ab (BioxCell) and incubated for 30 min. 32P-labeled WT or Mut TBRE duplex was then added and the mixture was incubated for 30 min on ice in the presence of poly-dIdC (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gel was dried and placed against X-ray film for 2 days, after which the radioactive signal was read on a Typhoon platform.

Luciferase reporter assays

HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated expression plasmids, firefly luciferase plasmids under the control of WT or Mut TBRE (Janesick et al., 2012), as previously described, or with human IFNG promoters in a pGL4.10 backbone (−565 - +85 of IFNG), and with a constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase plasmid for normalization (pRL-SV40). Cells were transfected in the presence of Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 3 days. Luciferase levels were measured with Dual-Glo reagent, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). Firefly luciferase values were normalized against Renilla luciferase values, and fold-induction is reported relative to controls transfect with empty plasmid.

Generation and analysis of T-bet-deficient NK-92 cells

T-bet-deficient NK-92 cells were generated according to a protocol described elsewhere (Sanjana et al., 2014). We used oligonucleotides for gRNA9 and gRNA15 (gRNA9_Forward: 5’-caccgtccaacaatgtgacccaggt-3’, gRNA_Reverse: 5’-aaacacctgggtcacattgttggac-3’; gRNA15_Forward: 5’-caccgccgcactcaccgtccctgct-3’, gRNA15_reverse: 5’-aaacagcagggacggtgagtgcggc-3’). DNA duplex was annealed from the oligonucleotides above, and was inserted into pLenti-CRISPR-V2 plasmids (Addgene) (Sanjana et al., 2014). We then used pLenti-CRISPR plasmids, VSV-G envelope, and psPAX2 plasmids to transfect HEK293T cells in the presence of Lipofectamine 2000. Supernatants containing lentiviruses were harvested and concentrated with Lenti-X concentrator (Takara Bio). We resuspended 106 NK-92 cells with 20x concentrated lentiviruses for gRNA9, gRNA15 or empty plasmid, in the presence of proleukin IL-2 (200 U/mL) (PROMETHEUS). After incubation for 2 days, we added 3.75 μg/mL puromycin to the culture for the selection of stably transduced NK-92 cells. After a further two weeks, cells were harvested for the Surveyor Nuclease Assay (Integrated DNA Tech) and a three-primer PCR-based screening system (Harayama and Riezman, 2017) to confirm successful DNA editing. Cells were plated at a density of 0.7 cells in 200μL per well in a U-bottomed 96-well plate. Two weeks later, single-cell clones were screened with a three-primer PCR-based system, with Phire Direct PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primers used for this screening assay were gRNA9_Forward: 5’- agcccctacccctaattcct-3’, gRNA9_Reverse: 5’-ggcatctattccctgggacc-4’, gRNA9_Reverse_in: 5’-cttttgaagagcaggtcctacct-3’ and gRNA15_Forward: 5’-GCCTGAATATGACCCCCGTC-3’, gRNA15_Reverse: 5’-caccactaccaccactaaagc-3’; gRNA15_Forward_in: 5’-acagagatgatcatcaccaagca-3’. Single-cell clones with biallelic disruptions were selected for validation by RT-qPCR and western blotting. EV-transduced single-cell clones were randomly picked as controls. Cells were then transduced with retroviruses generated from pLZRS-ires-ΔD271 plasmids containing EV, WT, Mut or K314R TBX21, as described above (Martínez-Barricarte et al., 2016). Stably transduced cells were isolated with anti-CD271 antibody-coated beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were stimulated with 50 pg/mL IL-12 (R&D) and 10 ng/mL IL-18 (InvivoGen), or were left unstimulated, and all cells were incubated for one day. The IFN-γ content of the supernatants was determined by ELISA. Intracellular IFN-γ production was measured with flow cytometry with intracellular staining (ICS). In brief, cells were fixed and permeabilized (BioLegend), and were subjected to ICS staining with FcBlock (Miltenyi Biotec), anti-T-bet BV421 (BioLegend) and anti-IFN-γ PE (BioLegend) before their use for ICS flow cytometry analysis.

Cytokine determinations in TBX21-transduced primary CD4+ T cells