Abstract

Background/purpose

Previous studies have suggested that mouth breathing has harmful effects on atopic dermatitis (AD) and oral health in children, but the evidence has been insufficient. To investigate the association of mouth breathing with AD and oral health in Korean schoolchildren aged 8–11 years.

Materials and methods

Cross-sectional data were obtained from March to April 2016. A questionnaire was used to investigate children's mouth breathing habits and personal/family histories related to allergic disease. Oral health status was determined through a clinical oral examination. Data were analyzed with multivariable logistic regression.

Results

In total, 1507 children were included. A moderate relationship was observed between mouth breathing and AD (adjusted odds ratio, 1.05; 95% confidence interval, 1.00–1.10; p-value, 0.035), whereas no association was found between mouth breathing and dental caries in children. Mouth breathing during sleep (MBS) was closely related to allergic diseases and other respiratory diseases. Furthermore, mouth breathing was associated with child's tonsillitis and was identified as a possible risk factor for class II dental malocclusion.

Conclusion

We confirmed the positive association between mouth breathing (especially during sleep) and allergic diseases, including the AD in school-aged children. The influence of mouth breathing on dental caries remains uncertain. An intervention trial is required to evaluate whether the prevention of mouth breathing can reduce the risk of allergic diseases.

Keywords: Allergic rhinitis, Asthma, Atopic dermatitis, Dental caries, Mouth breathing

Introduction

Recently, mouth breathing has been reported as a risk factor for immune diseases such as atopic dermatitis (AD; synonyms: atopic eczema and childhood eczema). However, the mechanism whereby mouth breathing is associated with AD has not been elucidated, and there is not enough evidence that mouth breathing is associated with an increased risk of AD in children. AD is a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory skin disease that starts in infancy or childhood and is accompanied by pruritus, dry skin, and eczema. AD is increasing worldwide and is reported to affect 20% of the population.1 This disease cannot be explained by a single cause; instead, environmental factors, genetic predisposition, immunological reactions, and skin barrier abnormalities are considered to be the major causes. Recently, mutations in the genes that produce filaggrin are involved in the development of AD.2 Also, according to the hygiene hypothesis, the immune system can better tolerate exposure to allergens in the environment at an early age. In this respect, there has been controversy over whether oral pathogens can influence the risk of allergic diseases.3 Some studies have investigated oral pathogens or periodontal disease as potential mitigators of allergic disease,4,5 but the results have been inconsistent.6,7

Simply, oral breathing can be considered a consequence of being unable to perform nasal breathing. However, if oral breath continues, complex problems can arise. Especially in animal experiments, such as those involving rat models, forced mouth breathing has been found to affect respiratory function.8 Human infants are sometimes considered obligate nasal breathers,9 but healthy humans can generally perform mouth breathing and nasal breathing simultaneously during functional activities such as eating, exercising, and blowing into an instrument. Oral and nasal breathing have different quantitative and qualitative effects on the respiratory system.8,10,11 If mouth breathing becomes chronic, the saliva will evaporate due to the change in humidity in the oral cavity. Thus, the saliva will not be able to maintain the homeostatic function of filtering foreign substances and controlling the humidity, temperature, and pH.12,13

In the mouth, saliva is essential for immune defense, food digestion and lubrication, taste, and remineralization of the teeth. In particular, antimicrobial agents such as secretory IgA and lysozyme are essential for protection. Furthermore, saliva is supersaturated by several ions that maintain the pH in the oral cavity between 6.2 and 7.4, which is vital for the prevention of dental caries. Patients with significantly reduced saliva due to Sjogren's syndrome or xerostomia are susceptible to infection due to changes in homeostasis and become vulnerable to allergic diseases and dental diseases such as dental caries and periodontitis.13,14

There have been some prospective cohort studies examining whether mouth breathing influences allergic diseases such as asthma and AD,15, 16, 17 but clinical studies have been limited to date. Therefore, we investigated the association of mouth breathing with oral health and allergic diseases, including AD among schoolchildren. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effects of mouth breathing on the prevalence of AD in schoolchildren aged 8–11 years.

Material and methods

Study approval

This study was approved by the Jeonbuk National University Institutional Review Board (2016-12-037-002). Informed consent was obtained from parents (or guardians), and permission was obtained from the children. Written consent forms were collected and securely stored at the Jeonbuk National Hospital. The study design conformed to the Helsinki Declaration of Human Rights for human observation studies.

Study population, data collection, and examiner training and calibration

Four elementary schools in Jeonju were randomly selected and visited from March to April 2016. Questionnaires and oral examinations were conducted for 1831 elementary school students aged 8–11 years. Oral examinations were carried out by two trained team members (one dentist and one recorder). The questionnaire was distributed to each child's parents one week before the oral examination and was collected after the oral exam. The survey was completed by the parents based on their observations of the child's condition. The questionnaire was only sent if the parents agreed that it could be used as part of a clinical study.

A pilot study was conducted on 50 elementary school students before the study began. Two dental examiners (D.W and Y.M) were trained by one experienced investigator (J.G) from the Pediatric Department of Jeonbuk National University. Through preliminary testing, the reliability of the test was determined with ten volunteers, and the intra-observer reliability was assessed with Cohen's kappa score. Cohen's weighted kappa scores for the Brodsky and Mallampati classification were 0.95 and 0.84, respectively. Cohen's weighted kappa scores for the dental caries indices (DI) and malocclusion indices (MI) ranged from 0.85 to 0.93. Regarding the inter-observer reliability, the kappa score was 0.81 for the Brodsky classification and 0.83 for the Mallampati classification. The MI were evaluated as Cohen's unweighted kappa score between 0.87 and 0.95. The kappa score was 0.81 for the DI.

Outcome measures

Questionnaire items

A questionnaire was used to investigate the children's mouth breathing habits, personal and family histories related to allergic disease, and basic information. The survey included three questions each to evaluate mouth breathing in the daytime (MBD) and mouth breathing during sleep (MBS). The inquiries related to MBD were as follows: Q.1 Does the child breathe through his mouth? Q.2 Is the child's mouth ordinarily open? Q.3 Does the child open his mouth when chewing? The questions related to MBS were as follows: Q.1 Does the child snore? Q.2 Does the child open his mouth? Q.3 Is the child's mouth dry in the morning? Scores were assigned for each question to grade the severity of mouth breathing (Supplemental Appendix Table 1). The questionnaire item was modified through the methods described by Yamaguchi et al. (17). The MBD and MBS scores were the sum of three items, each with a minimum score of 3 and a maximum score of 11. The TMB score was defined as the sum of the MBD and MBS scores.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all subjects and the relationships of age, sex, BMI, child's respiratory disease history, family history, and oral examination indices to oral breathing indices.

| Total |

MBD |

p Value | MBS |

p Value |

TMBI |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) or Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD or Pearson r | Mean ± SD or Pearson r | Mean ± SD or Pearson r | ||||

| Age (Y)# | |||||||

| 8 | 34 (2.26) | 4.88 ± 2.21 | 0.999 | 6.47 ± 1.52 | 0.413 | 11.35 ± 3.02 | 0.799 |

| 9 | 570 (37.82) | 4.89 ± 2.01 | 6.39 ± 1.80 | 11.28 ± 3.23 | |||

| 10 | 476 (31.59) | 4.88 ± 2.07 | 6.24 ± 1.74 | 11.11 ± 3.20 | |||

| 11 | 427 (28.33) | 4.90 ± 1.98 | 6.23 ± 1.73 | 11.14 ± 3.13 | |||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 730 (48.44) | 4.84 ± 1.98 | 0.320 | 6.15 ± 1.77 | 0.002∗∗ | 10.98 ± 3.19 | 0.015∗ |

| Male | 777 (51.56) | 4.94 ± 2.06 | 6.44 ± 1.73 | 11.38 ± 3.17 | |||

| BMI | 0.436 | 0.285 | 0.255 | ||||

| Child's History | |||||||

| Allergic rhinitis | |||||||

| Yes | 715 (47.45) | 5.16 ± 2.08 | < 0.001∗∗∗ | 6.69 ± 1.67 | <0.001∗∗∗ | 11.84 ± 3.18 | <0.001∗∗∗ |

| No | 792 (52.55) | 4.65 ± 1.95 | 5.95 ± 1.76 | 10.59 ± 3.07 | |||

| Atopic dermatitis | |||||||

| Yes | 239 (15.97) | 5.17 ± 2.12 | 0.021 ∗ | 6.54 ± 1.72 | 0.021∗ | 11.68 ± 3.22 | 0.009∗∗ |

| No | 1268 (84.03) | 4.84 ± 2.00 | 6.25 ± 1.76 | 11.09 ± 3.17 | |||

| Asthma | |||||||

| Yes | 57 (3.78) | 5.35 ± 2.18 | 0.080 | 6.82 ± 1.67 | 0.022∗ | 12.18 ± 3.43 | 0.017∗ |

| No | 1450 (96.22) | 4.87 ± 2.02 | 6.28 ± 1.76 | 11.15 ± 3.17 | |||

| Sinusitis | |||||||

| Yes | 157 (10.42) | 5.38 ± 2.25 | 0.004∗∗ | 6.78 ± 1.79 | <0.001∗∗∗ | 12.16 ± 3.50 | <0.001∗∗∗ |

| No | 1350 (89.58) | 4.83 ± 1.99 | 6.24 ± 1.75 | 11.07 ± 3.13 | |||

| Tonsillitis | |||||||

| Yes | 170 (11.28) | 4.99 ± 1.97 | 0.479 | 6.81 ± 1.73 | <0.001∗∗∗ | 11.80 ± 3.13 | 0.008∗∗ |

| No | 1337 (88.72) | 4.88 ± 2.03 | 6.24 ± 1.75 | 11.11 ± 3.18 | |||

| Nasal congestion | |||||||

| Yes | 493 (32.71) | 5.01 ± 2.01 | 0.104 | 6.58 ± 1.68 | <0.001∗∗∗ | 11.60 ± 3.12 | 0.001∗∗ |

| No | 1014 (67.29) | 4.83 ± 2.03 | 6.16 ± 1.78 | 10.99 ± 3.2 | |||

| Otitis media | |||||||

| Yes | 393 (26.08) | 5.12 ± 2.07 | 0.009∗∗ | 6.63 ± 1.76 | 0.741 | 11.75 ± 3.28 | <0.001∗∗∗ |

| No | 1114 (73.92) | 4.81 ± 2.00 | 6.18 ± 1.74 | 10.99 ± 3.13 | |||

| Family History | |||||||

| Allergic rhinitis | |||||||

| Yes | 962 (63.84) | 4.88 ± 2.01 | 0.839 | 6.47 ± 1.73 | <0.001∗∗∗ | 11.35 ± 3.14 | 0.010∗ |

| No | 545 (36.16) | 4.90 ± 2.06 | 6.00 ± 1.76 | 10.90 ± 3.25 | |||

| Atopic dermatitis | |||||||

| Yes | 219 (14.53) | 5.09 ± 2.10 | 0.121 | 6.36 ± 1.74 | 0.580 | 11.45 ± 3.17 | 0.189 |

| No | 1288 (85.47) | 4.86 ± 2.01 | 6.29 ± 1.76 | 11.14 ± 3.19 | |||

| Asthma | |||||||

| Yes | 31 (2.06) | 5.10 ± 2.26 | 0.567 | 6.68 ± 1.99 | 0.227 | 11.77 ± 3.86 | 0.299 |

| No | 1476 (97.94) | 4.89 ± 2.02 | 6.29 ± 1.75 | 11.17 ± 3.17 | |||

| Sinusitis | |||||||

| Yes | 98 (6.5) | 5.3 ± 2.36 | 0.079 | 7.03 ± 1.68 | <0.001∗∗∗ | 12.33 ± 3.42 | <0.001∗∗∗ |

| No | 1409 (93.5) | 4.86 ± 2.00 | 6.25 ± 1.75 | 11.11 ± 3.15 | |||

| Tonsillitis | |||||||

| Yes | 85 (5.64) | 5.42 ± 2.38 | 0.035∗ | 6.53 ± 1.69 | 0.215 | 11.95 ± 3.44 | 0.215 |

| No | 1422 (94.36) | 4.86 ± 2.00 | 6.29 ± 1.76 | 11.14 ± 3.16 | |||

| Nasal congestion | |||||||

| Yes | 295 (19.58) | 5.02 ± 2.07 | 0.220 | 6.51 ± 1.71 | 0.023∗ | 11.53 ± 3.18 | 0.039∗ |

| No | 1212 (80.42) | 4.86 ± 2.01 | 6.25 ± 1.77 | 11.10 ± 3.18 | |||

| Oral Examination | |||||||

| MI $ | 1.37 ± 1.24 | 0.021 | 0.414 | 0.03859 | 0.134 | 0.0363 | 0.159 |

| Posterior occlusal relationship# | |||||||

| Class I | 1019 (72.9) | 4.87 ± 2.01 | 0.626 | 8.09 ± 1.89 | 0.659 | 10.49 ± 3.23 | 0.568 |

| Class II | 302 (21.6) | 4.84 ± 2.03 | 8.13 ± 1.98 | 11.57 ± 3.40 | |||

| Class III | 75 (5.3) | 5.09 ± 2.27 | 8.29 ± 1.95 | 13.07 ± 3.61 | |||

| Overjet of incisors# | |||||||

| >4 mm | 1243 (82.4) | 4.86 ± 2.01 | 0.054 | 8.03 ± 1.90 | 0.004∗∗ | 12.90 ± 3.25 | 0.013∗ |

| 0–4 mm | 226 (14.9) | 5.06 ± 2.12 | 8.49 ± 2.05 | 13.56 ± 3.59 | |||

| <0 mm | 38 (2.5) | 4.23 ± 1.63 | 8.21 ± 1.78 | 12.44 ± 2.79 | |||

| Overbite of incisors# | |||||||

| >4 mm | 1406 (93.2) | 4.87 ± 2.01 | 0.551 | 8.10 ± 1.92 | 0.220 | 12.97 ± 3.29 | 0.736 |

| 0–4 mm | 83 (5.5) | 5.08 ± 2.12 | 8.04 ± 1.93 | 13.13 ± 3.53 | |||

| <0 mm | 18 (1.1) | 4.61 ± 1.97 | 8.88 ± 2.13 | 13.50 ± 3.20 | |||

| Asymmetry | |||||||

| Yes | 531 (35.24) | 4.93 ± 2.04 | 0.538 | 6.34 ± 1.79 | 0.545 | 11.27 ± 3.29 | 0.443 |

| No | 976 (64.76) | 4.87 ± 2.02 | 6.28 ± 1.74 | 11.14 ± 3.13 | |||

| Lip competency | |||||||

| Yes | 489 (32.45) | 4.96 ± 2.12 | 0.335 | 6.38 ± 1.76 | 0.207 | 11.35 ± 3.35 | 0.189 |

| No | 1018 (67.55) | 4.86 ± 1.98 | 6.26 ± 1.75 | 11.11 ± 3.10 | |||

| TSI $ | 4.44 ± 1.48 | 0.034 | 0.193 | 0.086 | 0.001∗∗ | 0.070 | 0.007∗∗ |

| Mallampati | 2.25 ± 0.89 | 0.013 | 0.608 | 0.016 | 0.540 | 0.019 | 0.464 |

| Brodsky | 2.19 ± 1.09 | 0.048 | 0.063 | 0.081 | 0.002∗∗ | 0.080 | 0.002∗∗ |

| DI $ | 3.49 ± 2.92 | 0.015 | 0.574 | 0.043 | 0.092 | 0.031 | 0.223 |

| dft | 2.53 ± 2.5 | 0.013 | 0.628 | 0.021 | 0.396 | 0.022 | 0.382 |

| DMFT | 0.95 ± 1.44 | 0.038 | 0.141 | 0.010 | 0.676 | 0.024 | 0.337 |

Independent two-sample t-test, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)#, and Pearson correlation test$ were used to calculate p values. MBD: mouth breathing index in the daytime, MBS: mouth breathing index during sleep, TMBI: total mouth breathing index, SD: standard deviation, MI: malocclusion index, TSI: tonsil size index, DI: dental caries index. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Oral examination items

All examinations were performed by two trained examiners (one dentist and one recorder). The examiner used a mirror and an air syringe under a light source, with an average time of one minute per exam. Three categories of oral examination items were used in this study: the caries experience index of deciduous teeth (dft) and permanent teeth (DMFT), Mallampati and Brodsky classifications, and the malocclusion index (MI). To investigate the prevalence of dental caries, the dentist evaluated the dft and DMFT in terms of the decayed, missing, and filling status of each tooth. The dental caries index (DI) was defined as the sum of the dft and DMFT indices. Mallampati classification (grades 1 to 4) and Brodsky classification (grades 1 to 5) were used to evaluate the size of the tongue and the palatine tonsil, respectively. These were assessed while the children were seated in a chair without phonation, with the tongue being maximally exposed, and were measured twice for reliability. The tonsil size index (TSI) was defined as the sum of the Brodsky and Mallampati classifications. The MI was defined as the sum of the values of the occlusal relationship of the first permanent molars, overjet of central incisors and overbite of incisors, midline deviation of permanent incisors, and presence of lip competency at rest. Occlusion was evaluated in the state of the centric occlusion. If the first molar or permanent incisors were missing or had not erupted, the subject was excluded from the survey. The overjet and overbite of incisors were classified into three categories (<0, 0–4, >4 mm) using Vernier calipers. The occlusal relationship of both first permanent molars was assessed by angle classification (class I/II/III). Midline deviation (yes, >1 mm) and lip competency were scored as binary parameters (1 = no, 0 = yes).

Data analysis

The results from the questionnaires and oral examinations were analyzed with SAS (version 9.3, SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Pearson's χ2 test was used to investigate the relationships of the mouth breathing indices with continuous variables such as age, sex, BMI, and oral examination indices. An independent two-sample t-test was performed to compare the mean values of the mouth breathing indices with categorical variables, including personal and family histories. We also conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis to determine the factors affecting each child's history as dependent variables. The stepwise selection was used by analyzing the factors affecting the history of the child, with correcting only the significant factors to determine the influence of mouth breathing. Bonferroni correction was used for posthoc analysis. Furthermore, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to assess the degree of mouth breathing associated with children's allergic diseases. To determine the cut-off points, we used the point at which the Youden Index J (Sensitivity + Specificity - 1) was maximized. All statistical analyses were performed with a p-value of 0.05.

Results

The questionnaires were distributed to 1831 elementary school children aged 8–11 years, and 1567 surveys were collected, for a response rate of 82.3%. We excluded 31 questionnaires that were missing basic information such as height and weight and 29 questionnaires that were missing answers to one or more questions. Thus, we included a total of 1507 questionnaires in this study.

The overall characteristics of the 1507 elementary school children are shown in Table 1. The male to female ratio was 1:0.94. There were no significant differences in the mouth breathing indices according to age and BMI, but a significant difference according to gender was observed (p < 0.05). Table 1 also displays the children's respiratory disease histories, family histories, and oral examination indices according to mouth breathing indices. Allergic rhinitis (47.5%) was the most common child's respiratory disease, followed by nasal congestion (32.7%) and otitis media (26.1%). AD was observed in 16.0% of the children. Personal histories of all diseases except otitis media were significantly associated with TMB (p < 0.05) and MBS (p < 0.05), whereas only allergic rhinitis, AD, sinusitis, and otitis media were associated with MBD (p < 0.05). Allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, tonsillitis, and nasal congestion were associated with the most statistically significant differences in MBS (p < 0.001). Regarding family history, allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, and nasal obstruction were associated with TMB (p < 0.05) and MBS (p < 0.05), while only tonsillitis was associated with MBD (p < 0.05). In terms of the oral examination, only overjet and Brodsky classification were significantly associated with MBS (p < 0.01).

When the relationships between MBD, MBS, and TMB scores were analyzed, statistically significant correlations were observed between each pair of variables (p < 0.001) (Table 2). MBD and MBS exhibited a moderate correlation, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.42.

Table 2.

Associations between MBD, MBS, and TMBI.

| Mean ± SD | MBD |

MBS |

TMBI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson r | p Value | Pearson r | p Value | Pearson r | p Value | ||

| MBD | 4.89 ± 2.03 | – | 0.42 | <0.001∗∗∗ | 0.86 | <0.001∗∗∗ | |

| MBS | 6.30 ± 1.76 | – | 0.82 | <0.001∗∗∗ | |||

| TMBI | 11.19 ± 3.18 | – | |||||

In order to determine the correlations between MBD, MBS, and TMBI, p values were calculated using Pearson's χ2 test. MBD: mouth breathing index in the daytime, MBS: mouth breathing index during sleep, TMBI: total mouth breathing index. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

In Table 3, multivariable linear regression was used to identify factors influencing each child's mouth breathing pattern (the dependent variable). There was a gender difference in MBS and TMB scores. Regarding MBD scores, only the child's history (allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, sinusitis) showed a statistically significant difference. Concerning MBS scores, child's history (allergic rhinitis, tonsillitis), family history (allergic rhinitis, sinusitis), and tonsil size index showed a statistically significant difference.

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regression analysis of factors associated with mouth breathing.

| Mouth breathing pattern |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBD score |

MBS score |

TMB score |

||||

| B (SE) | p Value | B (SE) | p Value | B (SE) | p Value | |

| Gender (reference = male) | −0.22 (0.088) | 0.014 | −0.27 (0.161) | 0.093 | ||

| Child History | 0.425 (0.106) | <0.001 | 0.557 (0.096) | <0.001 | 1.04 (0.176) | <0.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | ||||||

| Atopic dermatitis | 0.263 (0.142) | 0.065 | 0.189 (0.12) | 0.116 | 0.424 (0.221) | 0.056 |

| Sinusitis | 0.348 (0.174) | 0.045 | 0.133 (0.151) | 0.379 | 0.427 (0.276) | 0.122 |

| Tonsillitis | 0.352 (0.141) | 0.013 | 0.262 (0.265) | 0.323 | ||

| Otitis media | 0.218 (0.119) | 0.067 | 0.494 (0.188) | 0.009 | ||

| Family History | ||||||

| Allergic rhinitis | 0.218 (0.097) | 0.025 | −0.05 (0.178) | 0.792 | ||

| Sinusitis | 0.492 (0.185) | 0.008 | 0.768 (0.337) | 0.023 | ||

| Oral Examination | ||||||

| Brodsky classification | 0.104 (0.03) | 0.001 | 0.165 (0.054) | 0.002 | ||

Each mouth breathing score were the dependent variable, and the following variables showing p < 0.05 in each univariate analysis were included as independent variables; gender, child history (allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, asthma, sinusitis, tonsillitis), family history (allergic rhinitis, sinusitis), and oral examination (Brodsky classification). MBD: mouth breathing in the daytime, MBS: mouth breathing during sleep, TMB: total mouth breathing, B: non-standardized coefficient, SE: standard error. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors influencing AD (the dependent variable). In Table 4, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of MBD, MBS and TMB score for AD were 1.08, 1.09, 1.05 (all p-value < 0.05), respectively. And the AORs of family history tonsillitis (AOR: 2.24, 95% CI: 1.35–3.74) and family AD (AOR: 5.35, 95% CI: 3.87–7.38) for the child's AD was even higher. Among children's medical history, allergic rhinitis and asthma were not significantly associated with AD. Mallampati classification was related to mouth breathing (TMB score; AOR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.01–1.39).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with atopic dermatitis.

| MBD |

MBS |

TMBI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | p Value | AOR (95% CI) | p Value | AOR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Child History | ||||||

| Mouth Breathing | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 0.095 | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) | 0.031∗ | 1.05 (1.00–1.10) | 0.035∗ |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.10 (0.80–1.50) | 0.567 | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) | 0.677 | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) | 0.675 |

| Asthma | 1.34 (0.79–2.56) | 0.366 | 1.34 (0.70–2.53) | 0.376 | 1.33 (0.70–2.53) | 0.383 |

| Family History | ||||||

| Tonsillitis | 2.25 (1.34–3.75) | 0.002∗∗ | 2.29 (1.37–3.80) | 0.001∗∗ | 2.24 (1.34–3.74) | 0.002∗∗ |

| Atopic dermatitis | 5.34 (3.86–7.36) | <0.001∗∗∗ | 5.39 (3.90–7.43) | <0.001∗∗∗ | 5.35 (3.87–7.38) | <0.001∗∗∗ |

| Oral Examination | ||||||

| Mallampati classification | 1.19 (1.01–1.39) | 0.036∗ | 1.19 (1.01–1.40) | 0.035∗ | 1.18 (1.01–1.39) | 0.036∗ |

Atopic dermatitis was the dependent variable, and the following variables showing p < 0.05 in each univariate analysis were included as independent variables: mouth breathing habit, child history (asthma, allergic rhinitis), family history (allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, tonsillitis), and oral examination (Mallampati classification). MBD: mouth breathing index in the daytime, MBS: mouth breathing index during sleep, TMBI: total mouth breathing index, AOR: adjusted odds ratio, 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Table 5 displays the cut-off points, specificity, sensitivity, and AUC values from the ROC curve analysis. The analysis was performed for allergic rhinitis, AD, tonsillitis, and otitis media, which were associated with mouth breathing. The results of this analysis indicated that most of the AUC values were less than 0.6.

Table 5.

Cut-off points were calculated with the Youden Index J = (Sensitivity + Specificity - 1) for continuous variables (mouth breathing indices) that affected the dichotomous variables (children's respiratory diseases).

| Allergic Rhinitis |

Tonsillitis |

Otitis media |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBD | MBS | MBS | TMBI | MBS | TMBI | |

| Cut-off | <4, ≥4 | <7, ≥7 | <7, ≥7 | <11, ≥11 | <7, ≥7 | <11, ≥11 |

| Specificity | 45.076 | 61.995 | 55.049 | 52.020 | 57.002 | 47.666 |

| Sensitivity | 68.531 | 55.385 | 56.471 | 62.937 | 55.471 | 62.850 |

| AUC | 0.568 | 0.587 | 0.558 | 0.575 | 0.562 | 0.553 |

When the mouth breathing index was used as an independent variable and the child's respiratory disease was used as a dependent variable, multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that allergic rhinitis, tonsillitis, and otitis media were associated with mouth breathing. The AUC was calculated by plotting the ROC curve on these, and the cut-off point was calculated with the Youden Index J. AUC: area under the curve, MBD: mouth breathing index in the daytime, MBS: mouth breathing index during sleep, TMBI: total mouth breathing index.

Discussion

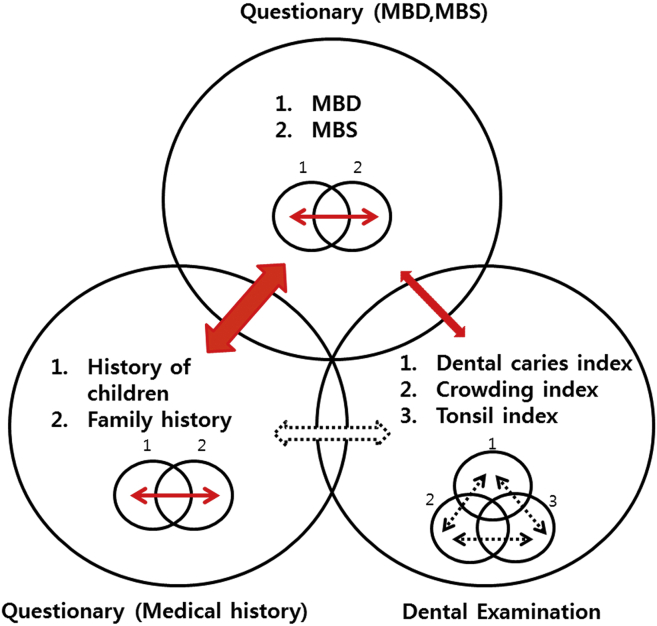

Fig. 1 outlines the relationship of the mouth breathing indices with personal or family histories of allergic diseases and oral examination indices in this study. The mouth breathing indices exhibited significant correlations with the children's allergic disease histories. The MBS was more closely related to the children's allergic diseases than the MBD. Furthermore, among the oral examination indices, the Brodsky classification and overjet of maxillary central incisors were related to mouth breathing indices. However, neither personal nor family allergic disease history was associated with oral examination indices. Most items in the children's allergic disease histories had strong relationships with the family histories, but there were weak correlations among the oral examination indices (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Summary of the relationship between the questionnaire items and the dental examination. A solid arrow means that there is a significant relationship, while a dotted arrow indicates that there is no significant relationship. MBD:mouth breathing in daytime, MBS: mouth breathing during sleep.

This study revealed that children with mouth breathing were at significantly higher risk for AD (TMB score; AOR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.00–1.10) and children's AD risk had a high correlation with parental AD history (TMB score; AOR: 5.3, 95% CI: 3.87–7.38). Although there have been few studies reporting the relationship between AD and mouth breathing, our findings are consistent with the results of a previous study of 468 preschool children aged 2–6 years suggesting that mouth breathing may be a risk factor for AD.17,18 According to the hygiene hypothesis, the allergy epidemic is the result of reduced microbial exposure.19 Several environmental factors related to microbial exposure have been studied for their association with AD, such as basic hygiene, daycare, farm environments and animals, endotoxin exposure, Helminth parasites, childhood infections, vaccinations, and antibiotics.1 In this context, some research has indicated that oral pathogens can influence the risk of allergic diseases.3 Although there are conflicting opinions, it can be inferred that the homeostasis of symbiotic bacteria in the oral cavity is critical. There have been reports that Staphylococcus aureus and coliforms are more common in the intestinal flora of children with a history of AD, and that fewer Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria are observed in traditional culture methods, indicating the importance of homeostasis in the human microflora.20,21 This is in line with recent findings that high salivary IgA levels are related to early day-care attendance and less atopy in Australian children,22 and that slow salivary secretory IgA maturation may be related to low microbial pressure and allergic symptoms in sensitized children.23

The results of this study suggest that there is a statistically significant relationship between MBD and MBS (p < 0.001, r = 0.419). Also, MBS was closely related to a child's medical history. MBS may be accompanied by reduced saliva secretion, resulting in further environmental changes in the oral cavity.24,25 Therefore, MBS is expected to be more harmful to children than MBD.

Many studies have used various methods to diagnose mouth breathing. Nevertheless, there are not many accurate ways to assess the severity of mouth breathing. Determining whether the mirror is frozen under the nose is a widely used method of diagnosing anatomical mouth breathing. However, habitual mouth breathing without accompanying anatomical problems cannot be identified by this method. Therefore, questionnaires are the easiest and most widely used method of diagnosing mouth breathing. However, surveys have limitations, in that the results differ according to the researchers’ standards for categorizing and analyzing categorical data. Therefore, in this study, we calculated the mouth breathing index as a continuous rather than a categorical variable, since the clinical standpoint for diagnosing mouth breathing is an arbitrary criterion and so is not clear. Regarding the ROC curve analysis, the sensitivity and specificity should generally be higher than 70%, and it is accepted that a diagnostic test is meaningful when the AUC is more significant than 0.7, which means that questionnaire surveys alone cannot accurately predict disease. This is because mouth breathing is a risk factor, not a cause of disease. However, questionnaires are non-invasive and cost-effective so that they can be useful supplements in predictions of allergic disease risk.

In this study, we employed the widely-used Brodsky and Mallampati classifications to measure the sizes of the tonsils and tongue, respectively. In general, the tonsils of a growing child are twice as large as those of an adult and decrease in size after puberty. Thus, some clinicians do not consider it necessary to cure tonsillar hypertrophy.26 However, when the increase in tonsil size exceeds the average level, the inner diameter of the upper airway decreases, which can markedly increase the air resistance (compared to that in adults) and induce mouth breathing. Therefore, some studies have reported that the frequency of mouth breathing was reduced and the quality of sleep was improved by adenotonsillectomy.27 In modern society, pediatric dentists observe tonsillar hypertrophy frequently in clinical practice and are interested in its relationship with immune disease. This study also indicated that the size of the palatine tonsil was related to mouth breathing. However, we cannot conclude whether mouth breathing is the cause or effect of tonsillar hypertrophy because nasal septum deviation or lower turbinate hypertrophy can also cause significant nasal obstruction. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that mouth breathing is a risk factor for AD development, especially in children with a genetic family history of AD, and can be a risk factor for tonsillitis (tonsillar hypertrophy) and class II dental malocclusion. Furthermore, mouth breathing during sleep (MBS) was closely related to allergic diseases and other respiratory diseases. Therefore, MBS is expected to be more harmful to children than MBD.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by research funds of Jeonbuk National University in 2018. This work was partially supported by the Biomedical Research Institute, Jeonbuk National University Hospital.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2020.06.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Flohr C., Mann J. New insights into the epidemiology of childhood atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2014;69:3–16. doi: 10.1111/all.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer C.N., Irvine A.D., Terron-Kwiatkowski A. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:441–446. doi: 10.1038/ng1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbes S.J., Jr., Matsui E.C. Can oral pathogens influence allergic disease? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1119–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbes S.J., Jr., Sever M.L., Vaughn B., Cohen E.A., Zeldin D.C. Oral pathogens and allergic disease: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1169–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedrich N., Völzke H., Schwahn C. Inverse association between periodontitis and respiratory allergies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36:495–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta A., Sequeira P.S., Sahoo R.C., Kaur G. Is bronchial asthma a risk factor for gingival diseases? A control study. N Y State Dent J. 2009;75:44–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stensson M., Wendt L.K., Koch G., Nilsson M., Oldaeus G., Birkhed D. Oral health in pre-school children with asthma–followed from 3 to 6 years. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:165–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2010.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie J., Xi Y., Zhang Q., Lai K., Zhong N. Impact of short term forced oral breathing induced by nasal occlusion on respiratory function in mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;205:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trabalon M., Schaal B. It takes a mouth to eat and a nose to breathe: abnormal oral respiration affects neonates' oral competence and systemic adaptation. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:207605. doi: 10.1155/2012/207605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daimon S., Yamaguchi K. Changes in respiratory activity induced by mastication during oral breathing in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2014;116:1365–1370. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01236.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erkan M., Erhan E., Sağlam A., Arslan S. Compensatory mechanisms in rats with nasal obstructions. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 1994;19:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi J.E., Waddell J.N., Lyons K.M., Kieser J.A. Intraoral pH and temperature during sleep with and without mouth breathing. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43:356–363. doi: 10.1111/joor.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eliasson L., Carlén A., Almståhl A., Wikström M., Lingström P. Dental plaque pH and micro-organisms during hyposalivation. J Dent Res. 2006;85:334–338. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitaba S., Matsui S., Iimuro E. Four cases of atopic dermatitis complicated by Sjögren's syndrome: link between dry skin and autoimmune anhidrosis. Allergol Int. 2011;60:387–391. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-CR-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurikainen K., Kuusisto P. Comparison of the oral health status and salivary flow rate of asthmatic patients with those of nonasthmatic adults–results of a pilot study. Allergy. 1998;53:316–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stensson M., Wendt L.K., Koch G., Oldaeus G., Birkhed D. Oral health in preschool children with asthma. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaguchi H., Tada S., Nakanishi Y. Association between mouth breathing and atopic dermatitis in Japanese children 2–6 years old: a population-based cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barros J., Becker H., Pinto J.A. Evaluation of atopy among mouth-breathing pediatric patients referred for treatment to a tertiary care center. J Pediatr. 2006;82:458–464. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okada H., Kuhn C., Feillet H., Bach J.F. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe S., Narisawa Y., Arase S. Differences in fecal microflora between patients with atopic dermatitis and healthy control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:587–591. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalliomäki M., Kirjavainen P., Eerola E., Kero P., Salminen S., Isolauri E. Distinct patterns of neonatal gut microflora in infants in whom atopy was and was not developing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:129–134. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.111237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewing P., Otczyk D.C., Occhipinti S., Kyd J.M., Gleeson M., Cripps A.W. Developmental profiles of mucosal immunity in pre-school children. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:196785. doi: 10.1155/2010/196785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fagerås M., Tomičić S., Voor T., Björkstén B., Jenmalm M.C. Slow salivary secretory IgA maturation may relate to low microbial pressure and allergic symptoms in sensitized children. Pediatr Res. 2011;70:572–577. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318232169e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawes C. How much saliva is enough for avoidance of xerostomia? Caries Res. 2004;38:236–240. doi: 10.1159/000077760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiler R.M., Fisberg M., Barroso A.S., Nicolau J., Simi R., Siqueira W.L., Jr. A study of the influence of mouth-breathing in some parameters of unstimulated and stimulated whole saliva of adolescents. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leboulanger N. Nasal obstruction and mouth breathing: the ENT's point of view. Orthod Fr. 2013;84:185–190. doi: 10.1051/orthodfr/2013048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Othman M.N., Abdul Latif H. Impact of adenotonsillectomy on the quality of life in children with sleep disordered breathing. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;91:105–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.