Highlights

-

•

Mammary hamartoma can reach large size especially in women.

-

•

Giant mammary hamartoma (GMH) can be diagnosed with mammogram and ultrasound only.

-

•

Imaging features are unique and feasible to illustrate in GMH.

Keywords: Case report, Giant, Mammary, Hamartoma, Radiological, Core biopsy

Abstract

Background

Mammary hamartoma is a benign rare tumour occurring in both sexes, with size range mostly between 2–4 cm. Giant breast hamartoma (GMH) is very rare and can reach unexpected sizes in women.

Presentation of the case

A 26 year old Egyptian female presented with left breast lump since 3 years, gradually increasing in size, with no other associated complaints. No family history of breast cancer, she did not smoke or consume alcohol, and had no past medical history. Examination revealed a large soft freely mobile mass (12 × 9 cm) in the lower outer quadrant of the left breast at the 3–6 o’clock position. There were no palpable axillary lymph nodes in both sides. Nipples and right breast were normal.

Discussion

The diagnosis of GMH can be made by examination and imaging only. The specific features that appear in mammogram and ultrasound can be used to reduce the need for core biopsy in hamartoma. Wide local excision is curative. We include a review of the literature of cases of GMH > 10 cm published during the last 15 years.

Conclusion

A non-invasive mammogram and ultrasound provide sufficient evidence of the tumour, hence core biopsy might not be critically required. However, if a breast hamartoma is still clinically suspected but with inconclusive or unequivocal mammographic and ultrasonographic features or if there is suspicion of dysplasia, then invasive core biopsy is justified. Recurrence is low and prognosis is good.

1. Introduction

Hamartomas are benign formations that can develop in various organs, including the breast [1]. Mammary hamartomas or (adenolipoma) represent rare benign breast tumours that account for < 4.8% of all benign breast disease [2]. The age group of affected patients is > 35 years and the mean age is about 45 years old [3]. A higher predominance of hamartomas exists among females compared to males [4]. The size of a hamartoma differs and might reach uncommonly large sizes. Giant hamartomas are very rare, only about 0.7% of hamartomas in women [5]. The increased sensitivity of screening and diagnostic modalities of breast disease (mammogram, breast ultrasound, core biopsy) have led to an increased diagnosis of hamartomas [6].

The term ‘hamartoma’ defines a pathology consisting of a well circumscribed tumour, composed of varying disorganised amounts of glandular tissue, fibrous stromas and fat tissue, with no neoplastic features [3]. A mammary hamartoma is mostly asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, or can present clinically as a painless, soft, freely mobile breast lump, with no attachments to skin or muscle [7]. They might be discovered incidentally during screening or for other reasons.

Hamartoma has unique imaging features on mammogram and ultrasound [7]. Ultrasound shows inhomogeneous echo structure of hypoechoic and hyperechoic areas, and band-like or nodular areas, reflecting the presence of adipose, epithelial, and fibrous connective tissues; while mammogram shows inhomogeneous radio-opaque and radiotransparent areas, and the presence of tissue that differ in density, with a thin radio-opaque pseudo-capsule [7].

We report a middle-aged Egyptian female with a large breast hamartoma. The case is unique as breast hamartomas are quite uncommon, and giant mammary hamartomas (GMH) are very rare [5]. In addition, the diagnosis of the current case was based on radiological features only, without the need of an invasive core biopsy. We also undertook and include a comprehensive review of the literature of cases of giant breast hamartomas >10 cm in the last 15 years. Accordingly, the size of the present hamartoma (13 × 11 × 3.7 cm) is amongst the four largest breast hamartomas within the last 15 years. The case is reported in line with the updated consensus-based surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines [8].

2. Case presentation

A 26 year old married Egyptian female presented to our breast outpatient clinic at Hamad General Hospital (largest academic tertiary care hospital) in Doha, Qatar, complaining of left breast lump since 3 years, gradually increasing in size, with no other associated breast complaint. The patient had no positive family history of breast cancer or any other significant family illness. She was multi-para, had her first child at the age of 22 years and breast-fed each child for 1.5 years. There was no significant hormonal intake, she did not smoke or consume alcohol, and had no past medical history.

On examination, the left breast looked larger than the right breast, cup A/B, with ptosis grade 2/3. On palpation, there was a large, soft, freely mobile mass (about 12 × 9 cm), located at the lower outer quadrant of the left breast at the 3–6 o’clock position. There were no palpable axillary lymph nodes in both sides, and the nipples and right breast were normal.

The patient was reassured and planned for mammogram with complementary ultrasound scan for both breasts in the next visit (used for diagnostic measures not for screening). Two weeks later at the breast clinic visit, the mammogram scan of both breasts showed a right breast cyst (5 mm) at the 1 o’clock position, and another lump (12 cm) in the outer lower quadrant of the left breast extending between the 2 and 6 o’clock positions (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). No other masses were observed in either breast and there were no lymph nodes.

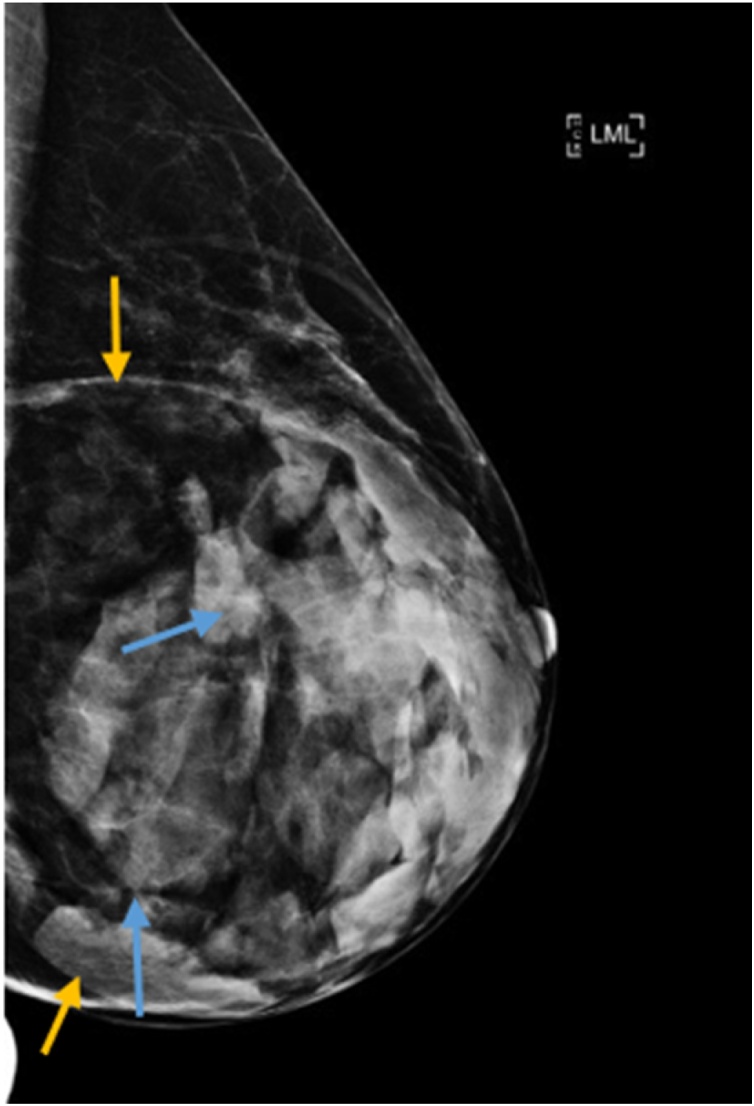

Fig. 2.

Medio-lateral mammogram of left breast showing large well circumscribed encapsulated mass (yellow arrows) and fibroglandular density (blue arrows).

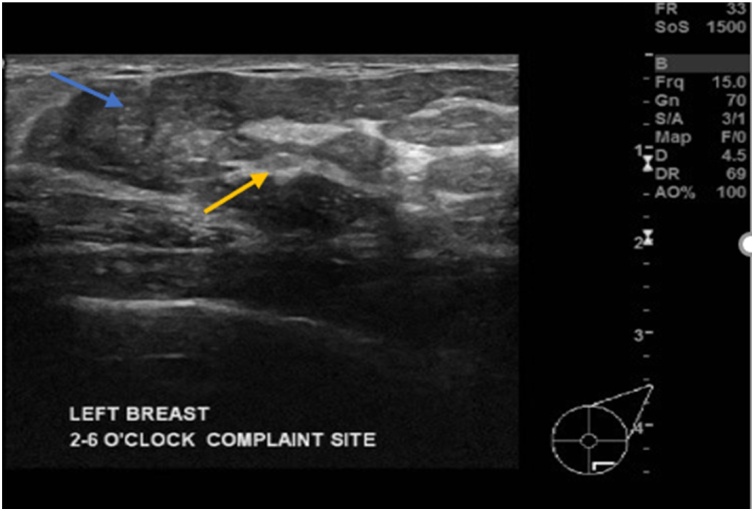

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound scan of left breast showing part of the mass in lower outer quadrant, demonstrating different echogenicity, peripheral isoechoic fat (blue arrow) and central echogenic fibroglandular tissue (yellow arrow).

The mammogram scan (Fig. 2) showed a large well circumscribed encapsulated mass with variable densities, fat (translucency subjacent to the capsule) and fibroglandular density, findings that are typical of hamartoma. The ultrasound scan (Fig. 3) showed part of the mass in the lower outer quadrant, demonstrating different echogenicity, peripheral isoechoic fat and central echogenic fibroglandular tissue typical of hamartoma.

In terms of differential diagnosis, the diagnosis of hamartoma by use of imaging is relatively straightforward, due to pathognomonic features in mammography. These comprised a mixed fat and glandular density lesion surrounded by a thin capsule. Fibroadenomas and phyllodes tumours, on the other hand, are predominantly dense with no apparent internal fat lucency in mammography.

The case was discussed with the radiologist who advised that there was no need for a core biopsy. The rationale behind not doing a biopsy was that the features of hamartoma were readily apparent on the ultrasound and mammogram. Instead of the invasiveness of the core biopsy, the radiologist suggested that it was more fruitful to proceed with excisional biopsy instead. Hence, the patient was planned for wide local excision of a left breast lump as a day care surgery case.

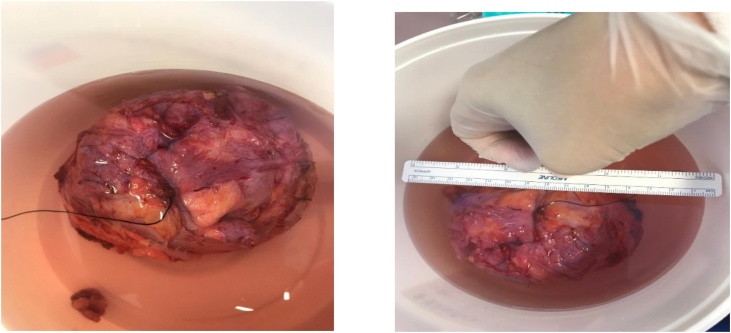

A wide local excision was undertaken by an experienced surgeon (consultant, breast surgery). On the day of surgery, the decision was to tackle the lump through an inframammary incision, with excision of a 2 cm wide skin ellipse from the superior fold in order to compensate for the discrepancy in the skin envelope size between both sides. As the hamartoma was soft and well circumscribed, dissection around it was relatively straightforward and it was excised fully with intact capsule. Haemostasis was performed and a 10 French surgical drain was inserted in the cavity, the wound was closed primarily in two layers with absorbable suture. The operation went smoothly with no complications. The mass was excised completely (Fig. 1), and the patient was discharged on the same day with the drain in left breast to prevent seroma collection. Upon follow up four days later at our breast clinic, the condition of the patient was good and the drain was removed. The histopathology reported dilated ducts of hamartoma and clusters of adipocytes within densely fibrotic stroma confirming mammary hamartoma of the left breast. The patient was reassured and she was pleased.

Fig. 1.

Specimen in formalin after excision; marking suture on lateral border of the tumor.

3. Discussion

The term breast hamartoma was first reported in 1971 by Arrigoni and colleagues [3]. GMH in women are very rare [5]. Based on the literature review we undertook of GMH reported in the last one and a half decades (Table 1). To the best of our knowledge, the current case is the first case from the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region reported in the last 15 years, as the rest of the published GMH cases during this period were reported from Europe and Asia.

Table 1.

Literature review of recent case reports of giant mammary hamartoma (> 10 cm, last 15 years).

| Case | G | Age | C | Investigation | Size (cm) | Lat | Location | Histopathology | Re |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Case 2020 Qatar | F | 26 | None | US and Ma: findings typical of H | 13 × 11 × 3.7 | L | Lower quadrant | Clusters of adipocytes with densely fibrotic stroma confirms H | — |

| Ghaedi 2018 UK [11] | F | 45 | — | Ma: encapsulated mass, mixed fat/soft tissue density, lobulated serpiginous areas of opacity centrally | 10 × 6 × 5 | L | Upper outer quadrant | Consistent with H: predominantly mature fat, varying proportions of breast parenchyma, nodular aggregate of lobular breast tissue, occasional stromal fibrosis | — |

| US: complex encapsulated mass, mixed texture, echogenic fatty with tubular hypoechoic structures | |||||||||

| CB: normal breast tissue, mild chronic inflammation | |||||||||

| MRI: complex encapsulated mass, soft tissue and fatty components | |||||||||

| Elhence 2017 India [12] | F | 35 | — | Ma: distorted breast architecture, prominent heterogeneous fibroglandular tissue, scattered hyperdense areas, lobulated hyperlucent areas, internal glandular density, few clustered coarse calcifications | 12 × 10 × 5 | R | Upper outer quadrant | Encapsulated lesion of variable admixture of connective tissue stroma suggesting H | — |

| CB: inconclusive, mature fibroadipose tissue and normal breast parenchyma | |||||||||

| Wang 2015 China [13] | F | 41 | — | US: solid heterogeneous mass | 11 × 9 × 3.5 | R | Upper outer quadrant | Encapsulated soft nodule, smooth margin, fibrotic envelope, adipocytic areas in fibrotic stroma suggesting H | — |

| Ma: well-circumscribed mass lesion, mixed density | |||||||||

| FNAC: refused by patient | |||||||||

| Kuhn-Beck 2014 France [15] | F | 26 | — | US: heterogeneous, characteristics suggest fibroepithelial lesion or H; no other imaging done due to pregnancy | 16 × 13 × 4 | R | — | Homogeneous lesion, no haemorrhagic or necrotic tissue, suggests H | — |

| CB: suspect the diagnosis of H | |||||||||

| Birrell 2012 Australia [16] | F | 58 | — | Ma: failed to identify the subtle capsule surrounding this space-occupying lesion | 18 × 16 × 7 | R | — | Revealed mixed stromal, glandular and fatty tissue, consistent with a H | — |

| Hernanz 2008 Spain [17] | F | 29 | — | Ma: well-circumscribed mass | 15 | L | Centre | Histopathology confirms H | — |

| CB: compatible with H | |||||||||

| Silva 2006 Brazil [14] | F | 33 | SLE | US: compatible with the diagnosis of a voluminous nodule | 10 × 8 × 6 | L | Axillary tail | Proliferated lobules and breast stroma, surrounded by capsule of conjunctive tissue characterizing the H | — |

| Sanal 2006 India [10] | F | 14 | — | MRI: well encapsulated mass, predominantly containing fat, randomly oriented hypointense areas | 13 × 9 | L | Upper quadrant | Lobular ducts surrounded by loose stroma, hyalinized connective tissue, adipose tissue consistent with H | — |

For space consideration, only the first author is cited; * in years; C: Comorbidities; CB: Core biopsy; F: female; FNAC: fine needle aspiration cytology; G: Gender; H: hamartoma; Lat: Laterality L: left; Ma: Mammogram; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; R: right; Re: Recurrence; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; US: ultrasound scan; —: not reported.

In terms of demographics, hamartomas affect patients of all age groups, mainly adults between the third and fifth decades, with a mean age of 45 years [3]. In addition, a higher predominance of tumours exists among females [4]. Table 1 is in agreement, where most of the patients with GMH were all females between 30–45 years old. Our patient was a 26 years old female, consistent with the literature.

The size of breast hamartomas in females commonly ranges between 2–4 cm, may vary considerably, and in rare instances could reach large sizes [9]. GMH are rarely encountered [10]. The current hamartoma reached 13 × 11 × 3.7 cm, larger than many other GMH reported in the literature [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. Table 1 depicts GMH > 10 cm, and shows that, globally, the current case represents the fourth GMH in the last 15 years, where only another three hamartomas larger than ours were reported in the literature [[15], [16], [17]]. Our case is also in agreement with that breast hamartomas commonly present as freely mobile well circumscribed painless lumps with no adherence to skin or muscle [7].

As for the investigations, the clinical diagnosis of a new breast lump is based on the ‘triple assessment’ approach, comprising examination, imaging (mammogram and sonography) and histology (core biopsy) that together provide a comprehensive algorithm [7]. Such combination of investigations results in a better diagnosis than the use of a single investigative method. In terms mammograph and ultrasonography, the classic GMH appearance comprises a mass surrounded by a thin radiopaque line (pseudocapsule) [18].

In our case, core biopsy was not undertaken because the mammogram and ultrasound both showed a clear appearance of a well circumscribed encapsulated mass, with variable density indicative of fat and fibrograndular tissue (Fig. 2, Fig. 3), strongly suggestive a hamartoma. Such an approach that relies on mammogram and ultrasound findings only without the need for additional core biopsy is consistent with other authors (Table 1) who also employed mammogram and ultrasound only, without core biopsy in their diagnosis [10,13,14,16]. Table 1 also illustrates others who undertook core biopsy after mammogram and ultrasound for four cases of hamartomas, however, the biopsy findings were inconclusive in two of these cases [11,12] whilst the diagnosis was suspected hamartoma in the other two cases [15,17].

Collectively, these imaging findings strongly suggest that invasive core biopsy might not be critically required in suspected GMH where non-invasive mammograph and ultrasonography provide sufficient evidence of the tumour. However, if a breast hamartoma is still clinically suspected but with inconclusive or unequivocal mammographic and ultrasonographic features, invasive core biopsy could then be justified. Likewise, in rare cases, an infiltrating carcinoma in situ may arise within a hamartoma [19]. Core biopsy in such instances is required to diagnose and detect the presence of carcinoma in situ or other dysplasia.

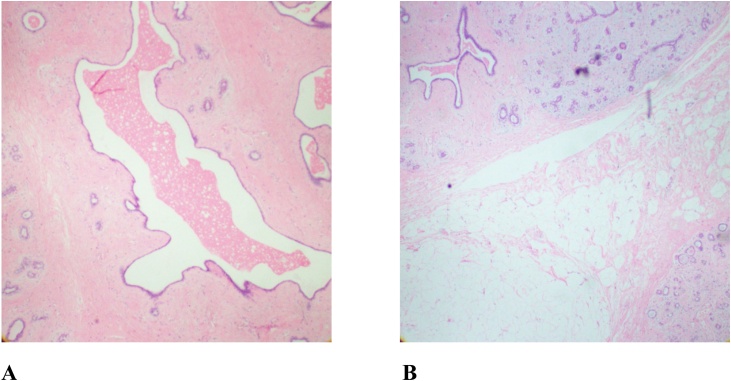

Histologically, hamartomas have been classified into various types based on the predominance of the tissue. The common types are fibrous, fibrocystic, and fibro-adenomatous with varying adipose tissue; rare types include myoid/muscular and chondroid/cartilage hamartomas [10]. For the current patient, the excised specimen confirmed the characteristics and diagnosis of a fibrous hamartoma (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A: Photomicrograph showing a dilated duct of breast hamartoma accompanied by fibrous stroma (H&E stain; original magnification ×20); B: Photomicrograph showing clusters of adipocytes within densely fibrotic stroma and disordered breast ducts and lobules (H&E stain; original magnification ×20).

In terms of procedure, wide local excision is the curative method for treating mammary hamartomas [20], as rarely, in situ malignancy can occur within a hamartoma. As for recurrence, Table 1 shows that for the reported cases of GMH during the last 15 years, there were no reported recurrences. Others have also observed that recurrence is only occasionally reported and has not been resolved yet [13].

4. Conclusion

Mammary hamartomas in females may develop to a large size. GMH has characteristic features on mammograph and ultrasound, and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a benign lump that is identified either clinically or due to certain features on imaging. In suspected GMH, if non-invasive mammograph and ultrasonography provide sufficient evidence of the tumour, core biopsy might not be critically required. However, if a breast hamartoma is still clinically suspected but with inconclusive or unequivocal mammographic and ultrasonographic features or if there is suspicion of dysplasia, invasive core biopsy could be justified. Overall, GMH has low potential of recurrence and good prognosis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Nothing to declare.

Funding

Nothing to declare.

Ethical approval

Approved by Medical Research Center, Hamad Medical Corporation reference number (MRC 04-20-1015).

Consent

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, written informed consent was not possible as it was deemed unethical that the patient travels to the hospital to sign the consent. Hence, informed verbal consent was obtained over the telephone from the patient after a through explanation of the fact that her case will be published in a scientific journal without breaking her confidentiality or disclosing her identity and she happily agreed to do so; the discussion was witnessed by a co-author.

Author’s contribution

Waleed Mahmoud: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Walid El Ansari: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Sara Hassan: Writing - review & editing. Sali Alatasi: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Haya Almerekhi: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Kulsoom Junejo: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Prof Dr Walid El Ansari.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the patient included in this report.

References

- 1.Wang T., Liu Y. Outcomes of surgical treatments of pulmonary hamartoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2016;12:116–119. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.191620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sevim Y., Kocaay A.F., Eker T. Breast hamartoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 27 cases and a literature review. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2014;69:515–523. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2014(08)03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrigoni M.G., Dockerty M.B., Judd E.S. The identification and treatment of mammary hamartomas. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1971;133:577–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erdem G., Karakaş H.M., Işık B., Fırat A.K. Advanced MRI findings in patients with breast hamartomas. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2011;17:33–37. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.1892-08.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanby A., Walker C., Tavassoli F.A., Devilee P. Volume IV. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2004. p. 103. (Pathology and Genetics: Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. WHO Classification of Tumours Series). Breast Cancer Research, 6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrokh D., Janbakhsh H., Ansaripour E. Breast hamartoma: mammographic findings. Iran. J. Radiol. 2011;8(4):258–260. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Kerwan A., SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. S1743-9191(20)30771-8. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones M.W., Norris H.J., Wargotz E.S. Hamartomas of the breast. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1991;173:54–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanal H.T., Ersoz N., Altinel O., Unal E., Can C. Giant hamartoma of the breast. Breast J. 2006;12(1):84–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaedi Y., Howlett D. Giant left breast hamartoma in a 45-year-old woman. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;30 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-226012. bcr2018226012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elhence P., Khera S., Rodha M.S., Mehta N. Giant hamartoma of the mammary gland- clinico-pathological correlation of an under-reported entity. Breast J. 2017;23(6):750–751. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z., He J. Giant breast hamartoma in a 41-year-old female: a case report and literature review. Oncol. Lett. 2015;10(6):3719–3721. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Silva B.B., Rodrigues J.S., Borges U.S., Pires C.G., Pereira da Silva R.F. Large mammary hamartoma of axillary supernumerary breast tissue. Breast. 2006;15(1):135–136. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhn-Beck F., Foessel L., Bretz-Grenier M.F., Akladios C.Y., Mathelin C. Gigantomastie unilatérale gravidique: à propos d’un cas d’hamartome géant [Unilateral gigantomastia of pregnancy: case-report of a giant breast hamartoma] Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. 2014;42(6):444–447. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birrell A.L., Warren L.R., Birrell S.N. Misdiagnosis of massive breast asymmetry: giant hamartoma. ANZ J. Surg. 2012;82(12):941–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernanz F., Vega A., Palacios A., Fleitas M.G. Giant hamartoma of the breast treated by the mammaplasty approach. ANZ J. Surg. 2008;78(3):216–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helvie M.A., Adler D.D., Rebner M., Oberman H.A. Breast hamartomas: variable mammographic appearance. Radiology. 1989;170:417–421. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.2.2911664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scally N., Campbell W., Hall S., McCusker G., Stirling W.J. Invasive ductal carcinoma arising within a breast hamartoma. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2011;180:767–768. doi: 10.1007/s11845-009-0402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sng K.W., Hong S.W., Foo C.L. Reduction mammaplasty in the surgical management of a giant breast hamartoma: case report. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 2001;(30):639–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]