Abstract

In Vietnam, fisheries play a key role in the national economy. Helminth infections in fish have a major impact on public health and sustainable fish production. A comprehensive summary of the recent knowledge on fish helminths is important to understand the distribution of parasites in the country, and to design effective control measures. Therefore, a systematic review was conducted, collecting available literature published between January 2004 and October 2020. A total of 108 eligible records were retrieved reporting 268 helminth species, among which are digeneans, monogeneans, cestodes, nematodes and acanthocephalans. Some helminths were identified with zoonotic potential, such as, the heterophyids, opisthorchiids, the nematodes Gnathostoma spinigerum, Anisakis sp. and Capillaria spp. and the cestode Hysterothylacium; and with highly pathogenic potential, such as, the monogeneans of Capsalidae, Diplectanidae and Gyrodactylidae, the nematodes Philometra and Camallanidae, the tapeworm Schyzocotyle acheilognathi, the acanthocephalans Neoechinorhynchus and Acanthocephalus. Overall, these studies only covered about nine percent of the more than 2400 fish species occurring in the waters of Vietnam. Considering the expansion of the aquaculture sector as a part of the national economic development strategy, it is important to expand the research to cover the helminth fauna of all fish species, to assess their potential zoonotic and fish health impacts.

Keywords: Systematic review, Helminths, Fish, Occurrence, Vietnam

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

268 helminth species were reported in 213 fish species occurring in Vietnam.

-

•

Reported zoonotic helminths belonged to digeneans, nematodes and cestodes.

-

•

Other species included monogeneans, nematodes, cestodes and acanthocephalans.

1. Introduction

With a variety of water bodies, Vietnam has been favoured by nature with a great potential for aquaculture. Vietnam is one of the largest aquaculture producers worldwide, accounting for 4.5% of the global production, and the third largest world fish exporter after China and Norway (FAO, 2018). Fisheries play a key role in the national economic sector, accounting for 3.7% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (VASEP, 2018). Next to its importance for the economy, fish provides a cheap protein source for the Vietnamese population (Allison, 2011). However, the local culinary habit to consume raw fish puts the Vietnamese population at risk for fish-borne zoonoses (Nguyen et al., 2020b). At the same time, general consumer expectations and living conditions are progressing, thus leading to an increased demand for safer fish.

Globally, helminth infections have a major impact on the fish industry due to the pathogenic effects of several species affecting productivity, as well as because of the zoonotic potential of many species. Humans acquire fish-borne helminth zoonoses via the consumption of raw or undercooked fish containing infective parasite larvae (Tada et al., 1983; Chai et al., 2005). The most important fish-borne helminth zoonoses are caused by trematodes of the families Opisthorchiidae and Heterophyidae, nematodes of the families Anisakidae, Gnathostomatidae and Capillariidae and cestodes of the family Diphyllobothriidae (dos Santos and Howgate, 2011). Opisthorchiid liver flukes are the leading aetiological agents of cholangiocarcinoma in East and Southeast Asia (Sithithaworn et al., 2014), while the pathological effects caused by heterophyid infections are generally less severe (Chai and Lee, 2002). The nematodes Anisakis spp. and Pseudoterranova spp. of the family Anisakidae, Gnathostoma spp. and Capillaria spp. are the most commonly reported fish-borne nematodes in humans globally, leading to gastro-intestinal lesions (Anisakidae and Capillariidae) or cutaneous larva migrans (Gnathostomatidae) (Cross and Belizario, 2007; Diaz, 2015; Ewa et al., 2015). Furthermore, fish cestodes of the genera Diphyllobothrium, Dibothriocephalus and Adenocephalus cause intestinal infections in humans in Europe, North and South America and Asia (Waeschenbach et al., 2017). Finally, some acanthocephalan species of the genera Bolbosoma, Corynosoma and Acanthocephalus may induce abdominal pain, ileus, ulceration and bleeding (Schmidt, 1971; Tada et al., 1983; Fujita et al., 2016). Both in wild and cultured fish, parasites may also have an impact on the function, growth, reproduction and survival of the hosts (Sindermann, 1987). In cultured fish, however, parasitic diseases are generally more severe, and may cause important economic losses due to stock mortality, declined productivity and reduced marketability (Paladini et al., 2017). Globally, financial losses due to parasitic diseases in the sector were estimated at 9.6 billion US dollars/year (Shinn et al., 2015). A wide variety of parasite species are known to cause morbidity and mortality in fish. For instance, a number of digenean trematodes, belonging to the families Aporocotylidae, Bolbophoridae, Clinostomidae, Diplostomidae and Heterophyidae, can cause loss of vision, necrosis, hemorrhage, obstructed blood flow and mortality (Mitchell et al., 2000; Overstreet and Curran, 2004; Ogawa et al., 2007; Wise et al., 2013; Jithila and Prasadan, 2019). Monogenean ectoparasites (e.g. of the families Capsalidae, Diplectanidae, Anoplodiscidae) commonly infect external surfaces of fish (gills, fins, skin, etc.) and cause irritation, reduced growth, respiratory distress, gills/skin/tissue damage and mortality (Reed et al., 2009). Furthermore, nematodes, e.g. of the genera Capillaria, Camallanus, Rhabdochona are of economic importance, due to their pathological effects in fish, as well as their impact on fish product marketability due to consumer aversion caused by the presence of macroscopic parasites in food (Molnár et al., 2006). Cestodes are another great concern for global fish populations. For instance, Schyzocoty leacheilognathi of the family Bothriocephalidae, is known to damage the intestinal tract and cause significant mortality (Scholz et al., 2012). Acanthocephalans, e.g. of the families Echinorhynchidae, Neoechinorhynchidae,Pomphorhynchidae, may also cause irreversible intestinal damage and impaired nutrient absorption (de Matos et al., 2017).

Because of the potential impact of fish parasites on public health and fish performance, as well as the importance of the fish industry and consumption in Vietnam, a recent summary of the knowledge on the helminths in fish is important to understand the distribution of parasites in the country, and to design effective preventive and control measures. Earlier, a FAO report compiled published information on the occurrence of parasites in freshwater, brackish and marine water fish found from the first known record in 1898 until the end of 2003 (Arthur and Te, 2006). Our aim was to conduct a systematic review of the latest published literature on the occurrence, prevalence and incidence of helminth infections in fish in Vietnam from 2004 onwards.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

Vietnam is a Southeast Asian country located on the eastern side of the Indochina Peninsula. The country is divided into three distinct regions, North, Central and South Vietnam, based on geographical and climatic features. Fish farming practices in Vietnam vary widely, from household earthen ponds to floating cages in rivers and seas at different levels of intensification (FAO, 2005). Overall, aquaculture production in the country is mostly small-scale (FAO, 2019). In North Vietnam (“the North” hereafter), comprising of the highlands and the Red River Delta, aquaculture is dominated by small-scale freshwater pond production at the household level (Van Huong et al., 2018). The traditional polyculture and integrated farming system (“Garden - Fish rearing - Livestock husbandry” termed VAC) is typical in the region (Van Huong et al., 2018). Moreover, fish cage aquaculture is widely practiced in the mountainous provinces (Tuan, 2002), whereas the large coastal north-eastern region has a well-developed brackish water and marine aquaculture (Kongkeo et al., 2010). Central Vietnam (“the Centre” hereafter) is characterized by a long coastal line with a narrow coastal plain. The region has favourable geographical conditions for brackish water and marine aquaculture, while freshwater aquaculture plays only a minor role (FAO, 2005). Finally, South Vietnam (“the South” hereafter) with the Mekong River Delta, is characterized by diversified aquaculture systems. These include pond, fence and cage culture of catfish, and various intensification levels of integrated farming systems such as, rice-cum-fish or mangrove-cum-aquaculture (FAO, 2005). Intensive farming of higher value species, mainly catfish (Pangasius bocourti and P. hypophthalmus) remains the major driver of aquaculture production in the Mekong Delta, although the more sustainable integrated aquaculture-agriculture farming systems are on the rise (Nhan et al., 2007).

2.2. Search strategy and study selection

A systematic review was conducted to gather current knowledge on the occurrence, incidence and prevalence of digenean trematodes, monogeneans, nematodes, cestodes and acanthocephalans in cultured and wild freshwater, brackish water and marine water fish in North, Central and South Vietnam, published between January 1st, 2004 and October 1st, 2020. While the checklist published by Arthur and Te (2006) aimed to provide a parasite-host list organized on a taxonomic basis and to provide information for each parasite species on the environment, the location in or on its host, the species of host(s) infected, the known geographic distribution in Vietnam, and the published sources for each host and locality record, that document did not report prevalence estimates nor did it discuss the importance of the identified parasites on human and fish health. Our systematic review aimed to summarize the more recent knowledge (2004–2020) on helminth infections in fish in Vietnam, to provide information for each parasite species on the environment, the fish species involved, the anatomic location in or on its host, the environment and the geographical distribution, and in addition to present prevalence estimates and discuss the impact of the occurrence of fish – pathogenic and zoonotic parasite species on the Vietnamese fish industry and on public health, respectively. To this end, the international scientific databases AGRICOLA, Aquatic Sciences & Fisheries Abstracts, CABI: CAB Abstracts and Global Health, MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Zoological Record were searched using the following search terms and Boolean operators: fish AND (helminth* OR parasit*) AND Vietnam. Google Scholar was searched for additional records using the same key words.

The guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were used for reporting the systematic review (Moher et al., 2009). After merging lists of records retrieved from each database, duplicates were removed. Next, titles and abstracts were screened and records were removed in case they did not cover helminth infections in fish in Vietnam. Finally, full-texts were screened for eligibility, using the following exclusion criteria: i) language not English or Vietnamese; ii) review and checklist articles; iii) topic outside study question; iv) location outside study area; v) not covering targeted helminth parasites; vi) no full-text available.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

The following data were extracted from the retrieved records: reference, study period, study province, setting (freshwater/brackish water/marine water), fish source (aquaculture/wild-caught fish), fish species studied, parasite species studied, sample size and prevalence. Afterwards, the broader study region (North, Central, South Vietnam) was determined based on the categorization of the study province according to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam (GSO, 2020). Briefly, moving from North to South, the North region expands from provinces bordering China in the North and Lao PDR in the North-West up to and including Son La, Hoa Binh and Ninh Binh provinces. The Centre borders with Lao PDR and Cambodia in the West, and expands from Thanh Hoa province up to and including Dak Nong, Lam Dong and Binh Thuan provinces. The South region is the last region, expanding from Binh Phuoc, Dong Nai and Ba Ria – Vung Tau provinces up to provinces bordering Cambodia in the West. Due to the distinct features of the three regions, helminth infections in fish were described separately. Data were entered and a descriptive analysis was conducted in Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

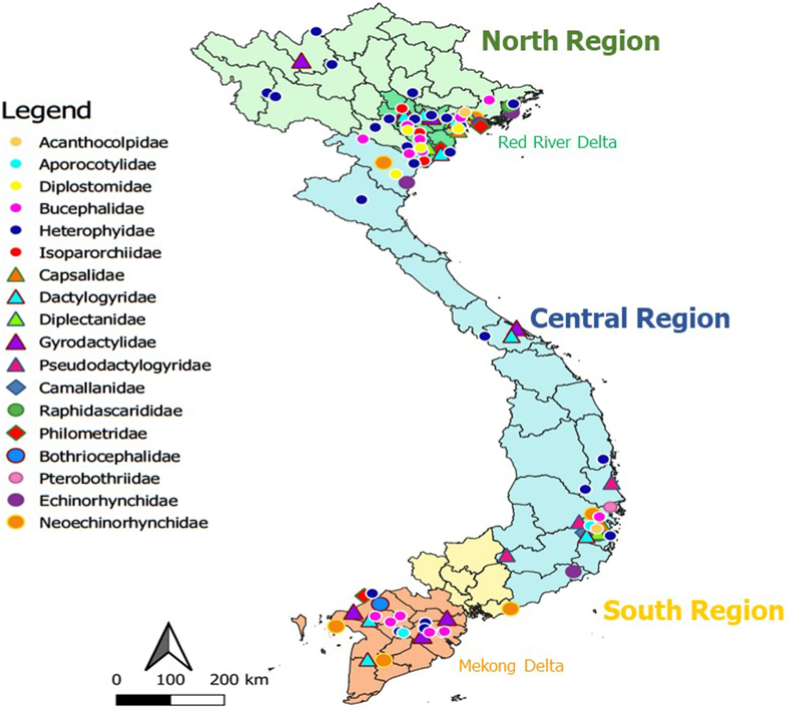

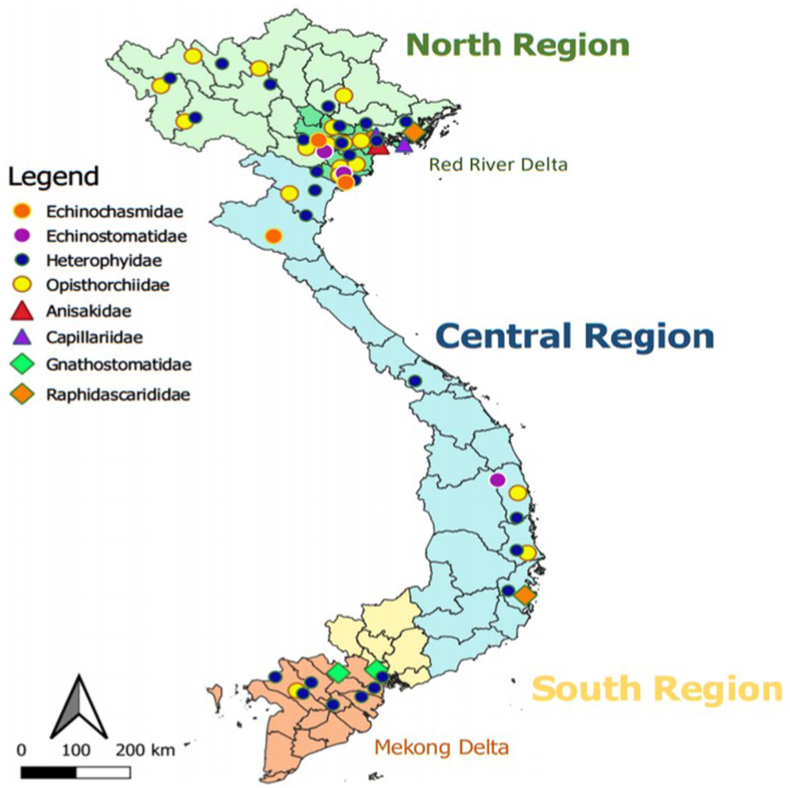

A total of 1772 records were retrieved from the scientific databases. After removing duplicates followed by title and abstract screening, full texts of 154 records were evaluated for eligibility. Two additional records were also evaluated. Finally, 108 studies were included in the qualitative analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). A total of 268 helminth species were reported in 213 of the more than 2400 fish species occurring in Vietnamese waters (Froese and Pauly, 2019). Among the 268 helminth species reported in our study, 159 had not been included in the report of Arthur and Te (2006), who described a total of 353 species. An overview of results on the occurrence of parasitic helminths in fish in freshwater and brackish/marine water in the 3 regions of the country is presented in Table 1, while more detailed results, including collected fish hosts for each study, are reported in Supplementary Table 1. The helminth list is taxonomically arranged according to the following classifications: for the trematoda, (Gibson et al., 2002; Bray et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2005); for the monogenea, (Boeger and Kritsky, 2001; WORMS, 2020); for the cestodes, (Caira and Jensen, 2017); for the nematoda (Bain et al., 2013), and for the acanthocephala, (Amin, 2013). Advances in molecular biology have resulted in continuous revisions in the taxonomy of helminth species. For instance, molecular evidence has indicated that the family Ancyrocephalidae of the monogenean class is not valid (Šimková et al., 2003, 2006; Blasco-Costa et al., 2012). Therefore, an updated classification of the parasites is provided (Table 1). Moreover, the existence of synonyms for helminths species names was checked by using Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/) and World Register of Marine Species (http://www.marinespecies.org/index.php) and is also presented in Table 1. The distribution of the potentially pathogenic parasitic helminths, and zoonotic helminths in fish are shown in Fig. 1 and in Fig. 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Overview of the results of a systematic review on helminth infections in fish in Vietnam.

| Parasite |

North |

Central |

South |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type |

Fresh |

Marine |

Brackish |

Fresh |

Marine |

Brackish |

Fresh |

Marine |

|||||||||||

| Trematodes |

W | C | W | C | W | C | W | C | W | C | W | C | W | C | W | C | |||

| Order | Family | Species | Synonyms | ||||||||||||||||

| Trematoda | |||||||||||||||||||

| Aspidogastrida | Aspidogastridae | Aspidogaster decatis | Aspidogaster enneatus | x | |||||||||||||||

| Aspidogaster limacoides | Aspidogaster donicum | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Azygiida | Isoparorchiidae | Isoparorchis hypselobagri | Distomum hypselobagri | x | |||||||||||||||

| Diplostomida | Aporocotylidae | Nomasanguinicola canthoensis | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Psettarium anthicum | Cardallagium anthicum | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Diplostomidae | Diplostomum spp. | Hemistomum spp.; Proalaria spp.; Monocerca spp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Posthodiplostomum sp. | Choanouvulifer sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Strigeidae | Nematostrigea vietnamiense | Prodiplostomulum vietnamiense | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Nematostrigea sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Plagiorchiida | Acanthocolpidae | Acanthocolpus liodorus | Acanthocolpus guptai; Acanthocolpus inglisi; Acanthocolpus luehei; Acanthocolpus luhei; Acanthocolpus manteri; Acanthocolpus microtesticulus | x | |||||||||||||||

| Acanthocolpus luhei | Acanthocolpus liodorus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Pleorchis hainanensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pleorchis sciaenae | Pleorchis ghanensis; Pleorchis psettodesai; Pleorchis puriensis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Stephanostomoides dorabi | Stephanostomoides tenuis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Stephanostomum spp. | Echinostephanus spp.; Lechradena spp.; Monorchistephanostomum spp.; Stephanochasmus spp. | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Stephanostomum bicoronatum | Distomum bicoronatum; Stephanochasmus bicoronatus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Stephanostomum ditrematis | Echinostephanus ditrematis; Stephanostomum longisomum; Stephanostomum seriolae | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Tormopsolus sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Aephnidiogenidae | Aephnidiogenes barbarus | Aephnidiogenes isagi | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Apocreadiidae | Homalometron sp. | Anallocreadium spp.; Apocreadium spp.; Austrocreadium spp.; Barbulostomum spp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Azygiidae | Azygia hwangtsiyui | Azygia amuriensis | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Azygia robusta | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bivesiculidae | Bivesicula spp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Paucivitellosus vietnamensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bucephalidae | Bucephalus polymorphus | Bucephalus markewitschi | x | ||||||||||||||||

| - | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Prosorhynchoides ozakii | Bucephaloides ozakii; Prosorhynchoides koreana | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Prosorhynchus epinepheli | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Prosorhynchus luzonicus | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Prosorhynchus maternus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Prosorhynchus pacificus | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Prosorhynchus tonkinensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Prosorhynchus spp. | Chabaudtrema sp.; Gotonius spp.; Paraprosorhynchus sp.; Rudolphinus sp. | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Callodistomidae | Cholepotes sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Cephalogonimidae | Eumasenia moradabadensis | Masenia moradabadensis | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Cryptogonimidae | Exorchis oviformis | Metadena oviformis | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Exorchis spp. | Parametadena spp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Metadena bagarii | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudallacanthochasmus plectorhynchi | Beluesca plectorhyncha | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Pseudometadena celebesensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Derogenidae | Gonocercella pacifica | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Vitellotrema fusipura | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Didymozoidae | - | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Multtubovarium amphibolum | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Echinochasmidae | Echinochasmus japonicus | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Echinochasmus spp. | Episthmium sp.; Episthochasmus sp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Echinostomatidae | Echinostoma spp. | Echinostomum spp. | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Faustulidae | Paradiscogaster drepanei | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Fellodistomidae | Pseudosteringophorus sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Gorgoderidae | Cetiotrema carangis | Phyllodistomum carangis | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Phyllodistomum strictum | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Phyllodistomum spp. | Catoptroides spp.; Phyllochorus sp.; Plesiodistomum sp.; Spathidium spp.; Vitellarinus sp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Haploporidae | Carassotrema koreanum | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Elonginurus mugilus | Phanurus oligoovus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Parahaploporus elegantus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parasaccocoelium mugili | Pseudohapladena mugili; Pseudohapladena lizae | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Pseudohaploporus planilizum | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudohaploporus pusitestis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudohaploporus sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudohaploporus vietnamensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Skrjabinolecithum spasskii | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Unisaccus tonkini | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Haplosplanchnidae | Haplosplanchnus pachysomus | Haplosplanchnus otolithi; Haplosplanchnus pachysoma | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Pseudohaplosplanchnus catbaensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hemiuridae | Allostomachicola secundus | Stomachicola secundus; Stomachicola rauschi | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Aphanurus mugilis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Aphanurus stossichi | Aphanurus monolecithus; Apoblema stossichii | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Dinurus sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Erilepturus formosae | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Erilepturus hamati | Ectenurus paralichthydis; Erilepturus paralichthydis; Ectenurus platycephali; Ectenurus hamati; Erilepturus platycephali; Erilepturus tiegsi; Erilepturus collichthydis; Erilepturus bohaiensis; Lecithochirium neopacificum; Uterovesiculurus berdae; Uterovesiculurus caranxi; Uterovesiculurus chilkai; Uterovesiculurus fujianensis; Uterovesiculurus gazzi; Uterovesiculurus hamati; Uterovesiculurus indicus; Uterovesiculurus lutianius; Uterovesiculurus neopacificus; Uterovesiculurus orientalis; Uterovesiculurus paralichthydis; Uterovesiculurus platycephali; Uterovesiculurus sinensis; Uterovesiculurus sphyraenae; Uterovesiculurus spindlis; Uterovesiculurus thrissocli | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Hemiurus arelisci | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hysterolecitha sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lecithochirium alectis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lecithochirium imocavum | Sterrhurus imocavus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithochirium neopacificum | Erilepturus hamati | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithichirium sp. | Anaplerurus sp.; Ceratotrema sp.; Magniscyphus sp.; Neohysterolecitha sp.; Separogermiductus spp.; Sterrhurus spp.; Umatrema sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithocladium apolecti | Lecithocladium anteporus; Lecithocladium arabianum; Lecithocladium hexavitellarii; Lecithocladium microcaudum; Lecithocladium microductus; Lecithocladium octovitellarii; Lecithocladium stromatei; Lecithocladium tetravitellarii | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithocladium excisum | Distoma excisum; Lecithocladium crenatum | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithocladium ilishae | Lecithocladium harpodontis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithocladium sp. | Bengalotrema sp.; Cleftocolleta sp.; Colletostomum sp.; Magnapharyngium sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Merlucciotrema praeclarum | Sterrhurus praeclarus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Parahemiurus merus | Hemiurus merus; Parahemiurus atherinae; Parahemiurus noblei; Parahemiurus parahemiurus; Parahemiurus platichthyi; Parahemiurus sardiniae; Parahemiurus seriolae | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Parahemiurus spp. | Anahemiurus spp.; Engraulitrema spp.; Daniella sp.; Dentiacetabulum sp.; Lecithomonoium sp.; Trilecithotrema sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Stomachicola muraenesocis | Stomachicola bayagbonai; Stomachicola chauhani; Stomachicola cinereusis; Stomachicola guptai; Stomachicola karachiensis; Stomachicola kinnei; Stomachicola magna; Stomachicola magnaesophagustum; Stomachicola mastacembeli; Stomachicola pelamysi; Stomachicola polynemi; Stomachicola rubeus; Stomachicola serpentina; Stomachicola singhi | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Heterophyidae | Centrocestus formosanus | Stamnosoma formosanum | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Centrocestus spp. | Stamnosoma spp. | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Haplorchis yokogawai | Monorchotrema yokogawei | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Haplorchis pumilio | Monostomum pumilio | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Haplorchis taichui | Haplorchis microrchis; Monorchotrema taichui | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Haplorchis spp. | Monorchotrema spp. | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Heterophyopsis continua | Heterophyes continua | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Metagonimus sp. | Dexiogonimus sp.; Loossiaspp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Procerovum cheni | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Procerovum varium | Procerovum hoihowense; Procerovum sisoni | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Procerovum spp. | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Pygidiopsis summa | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Stellantchasmus falcatus | Stellantchasmus amplicaecalis; Stellantchasmus formosanus; Stellantchasmus milvi | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| Stictodora lari | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| - | – | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithasteridae | Aponurus laguncula | Aponurus elongatus; Aponurus trachinoti; Aponurus waltairensis | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Aponurus pyriformis | Aponurus symmetrorchis; Brachadena pyriformis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Aponurus sp. | Bilqeesotrema sp.; Brachadena sp.; Mordvilkoviaster sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Brachadena pyriformis | Aponurus pyriformis; Lecithophyllum pyriforme | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Hysterolecitha nahaensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hysterolecithoides epinepheli | Hysterolecithoides frontilatus; Hysterolecithoides guangdongensis; Hysterolecithoides trilobatus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithaster confusus | Lecithaster bothryophorus; Lecithaster musteli | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithaster mugilis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lecithaster sayori | Lecithaster tylosuri | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithaster sp. | Anadichadena sp.; Leptosoma sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lecithodendriidae | Cryptotropa kuretanii | Cryptotrema kuretanii | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Lepocreadiidae | Caecobiporum rutellum | Diploproctodaeum rutellum | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Diploproctia drepanei | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Diploproctodaeum plataxi | Diploproctodaeoides plataxi | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Multitestis magnacetabulum | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Opechona formiae | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Trigonotrema alatum | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lissorchiidae | Asaccotrema vietnamiense | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Asymphylodora japonica | Orientotrema japonica | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Asymphylodora sp. | Orientotrema sp.; Parasymphylodora sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Microphallidae | Carneophallus sp. | Microphallus sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Maritrema subdolum | Maritrema rhodanicum | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Monorchiidae | Huridostomum formionis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Hurleytrematoides chaetodoni | Hurleytrema chaetodoni | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lasiotocus cacuminatus | Alloinfundiburictus cacuminatus; Genolopa cacuminata | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lasiotocus chaetodipteri | Infundiburictus chaetodipteri; Proctotrema chaetodipteri | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lasiotocus cryptostoma | Alloinfundiburictus cryptostoma; Proctotrema cryptastoma | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lasiotocus lizae | Sinistroporomonorchis lizae | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lasiotocus macrorchis | Paralasiotocus macrorchis Proctotrema macrorchis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Lasiotocus plectorhynchi | Genolopa plectorhynchi | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Leiomonorchis leiognathi | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Longimonorchis ovacutus | Opisthomonorcheides ovacutus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Monorchis diplovarium | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Opecoelidae | Allopodocotyle sp. | Pedunculotrema sp. | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Helicometra fasciata | Distoma fasciatum; Helicometra dochmosorchis; Helicometra flava; Helicometra gobii; Helicometra hypodytis; Helicometra labri; Helicometra markewitschi; Helicometra marmoratae; Helicometra mutabilis; Helicometra neoscorpanae; Helicometra pulchella; Helicometra scorpaenae; Helicometra sinuata; Helicometra upapalu | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Helicometra pisodonophi | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Helicometra sp. | Allostenopera sp.; Loborchis sp.; Stenopera sp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Macvicaria sp. | Cryptacetabulum spp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Opecoelus brevifistulus | Opegaster brevifistula | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Opecoelus haduyngoi | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Opecoelus parapristipomatis | Opegaster parapristipomatis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Opecoelus pteroisi | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Opecoelus sphaericus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Podocotyle petalophallus | Podocotyloides petalophallus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Podocotyle epinepheli | Allopodocotyle epinepheli | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Opisthorchiidae | Clonorchis sinensis | Distoma sinense | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Metorchis kimbangensis | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Opisthorchis viverrini | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Opisthorchis viverrini duck - genotype | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Orientocreadiidae | Macrotrema sp. | Orientocreadium sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Orientocreadium batrachoides | Orientocreadium barabankiae; Orientocreadium bharati; Orientocreadium dayalai; Orientocreadium dayali; Orientocreadium indica; Orientocreadium lazeri; Orientocreadium mahendrai; Orientocreadium philippai; Orientocreadium raipurensis; Orientocreadium secundum; Orientocreadium umadasi; Orientocreadium vermai | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Philophthalmidae | Phylophthalmus sp. | Natterophthalmus sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Sclerodistomidae | Prosogonotrema clupeae | Prosogonotrema bilabiatum | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Prosorchis chainanensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Transversotrematidae | Transversotrema patialense | Transversotrema chackai; Transversotrema koliense; Transversotrema laruei; Transversotrema soparkari | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| - | - | - | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Monogenea | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capsalidea | Capsalidae | Benedenia epinepheli | Benedeniella congeri; Epibdella epinepheli; Neobenedeniella congeri | x | |||||||||||||||

| Benedenia spp. | Neobenedeniella sp.; Tareenia spp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Encotyllabe spari | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neobenedenia spp. | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sessilorbis limopharynx | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sprostoniella multitestis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dactylogyridea | Ancylodiscoididae | Silurodiscoides spp. | Parancylodiscoides spp.; Thaparocleidus spp. | x | |||||||||||||||

| Thaparocleidus caecus | Ancylodiscoides caecus; Silurodiscoides caecus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Thaparocleidus furcus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Thaparocleidus infundibulus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Thaparocleidus siamensis | Silurodiscoides siamensis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Thaparocleidus sudartoi | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Thaparocleidus turbinatio | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dactylogyridae | Ancyrocephalus bilobatus | Haliotrema bilobatum; Haliotrema bilobatus | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Ancyrocephalus macrogaster | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ancyrocephalus parspinicirrus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ancyrocephalus scapulasser | Protogyrodactylus scapulasser | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Ancyrocephalus spinicirrus | Haliotrema spinicirrus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Ancyrocephalus spp. | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Ancyrocephalus unicirrus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dactylogyrus magnihamatus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dactylogyrus minutus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dactylogyrus spp. | Aplodiscus sp.; Falciunguis sp.; Microncotrema sp.; Microncotrematoides sp.; Neodactylogyrus spp.; Paradactylogyrus spp.; | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Haliotrema cromileptis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Haliotrema epinepheli | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Haliotrema geminatohamula | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Haliotrema spinicirrus | Ancyrocephalus spinicirrus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Haliotrema spp. | Parahaliotrema spp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Metahaliotrema kulkarnii | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Metahaliotrema mizellei | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Metahaliotrema scatophagi | Metahaliotrema geminatohamula | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Metahaliotrema similis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Metahaliotrema yamagutii | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Metahaliotrema ypsilocleithrum | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Paradiplectanotrema trachuri | Diplectanotrema trachuri | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Diplectanidae | Calydiscoides flexuosus | Calydiscoides indianus; Calydiscoides indicus; Lamellodiscus flexuosus | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Diplectanum blairense | Paradiplectanum blairense | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Diplectanum grouperi | Pseudorhabdosynochus grouperi | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Diplectanum spp. | Lamellodiscoides spp.; Pseudolamellodiscoides spp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Murraytrema pricei | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudorhabdosynochus epinepheli | Diplectanum epinepheli | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Pseudorhabdosynochus brunei | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudorhabdosynochus nhatrangensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pseudorhabdosynochus vietnamensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Psedorhabdosynochus spp. | Cycloplectanum spp. | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Protogyrodactylidae | Protogyrodactylus | Daitreosoma; Empleurosoma; Gussevstrema; Trivitellina | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Pseudodactylogyridae | Pseudodactylogyrus anguillae | Neodactylogyrus anguillae | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Pseudodactylogyrus bini | Dactylogyrus bini | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Gyrodactylidea | Bothitrematidae | Bothitrema spp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Gyrodactylidae | Gyrodactylus ctenopharyngodontus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Gyrodactylus ophiocephali | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gyrodactylus spp. | Paragyrodactyloides sp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Mazocraeidea | Axinidae | Loxuroides pricei | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Unnithanaxine naresii | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Diplozoidae | Diplozoon paradoxum | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Gastrocotylidae | Pseudaxinoides vietnamensis | Pseudaxine vietnamensis | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Heteraxinidae | Bicotyle perpolita | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Karavolicotyla ruber | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Karavolicotyla tuyeti | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lethrinaxine parva | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Monaxine formionis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Microcotylidae | Intracotyle orientale | Intracotyle orientalis | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Paramonaxinidae | Incisaxine dubia | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Nematoda | |||||||||||||||||||

| Enoplida | Capillariidae | Capillaria spp. | Thominx sp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Rhabditida | Anisakidae | Anisakis sp. | Conocephalus sp.; Stomachus sp. | x | |||||||||||||||

| Camallanidae | Camallanus spp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Spirocamallanus istiblenni | Procamallanus istiblenni | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Cucullanidae | Cucullanellus minutus | Cucullanus minutus; Dichelyne minutus | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Cucullanus sp. | Bacudacnitis sp.; Bulbodacnitis sp.; Dacnitis sp.; Indocucullanus sp.; Neocucullanellusus sp.; Paracucullanellus sp.; Serradacnitis sp.; Truttaedacnitis sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Kathlaniidae | Spectatus sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Raphidascarididae | Hysterothylacium spp. | Maricostula spp.; Thynnascaris spp. | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| Raphidascaris spp. | Neogoezia sp. | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Philometridae | Philometra spp. | Ichthyonema sp.; Sanguinofilaria spp.; Thwaitia spp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Spirurida | Cystidicolidae | Ascarophis moraveci | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Ascarophis spp. | Pseudocystidicola spp. | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Gnathostomatidae | Gnathostoma spinigerum | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Cestoda | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bothriocephalidea | Bothriocephalidae | Bothriocephalus acheilognathi | Schyzocotyle acheilognathi | x | |||||||||||||||

| Lecanicephalidea | Lecanicephalidae | Tylocephalumsp. | Spinocephalum sp. | x | |||||||||||||||

| Onchoproteocephalidea | Proteocephalidae | Proteocephalus sp. | Ichthyotaenia sp. | x | |||||||||||||||

| Rhinebothriidea | Rhinebothriinae | - | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Tetraphyllidea | - | - | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Trypanorhyncha | Pterobothriidae | Pterobothrium sp. | Neogymnorhynchus sp.; Syndesmobothrium sp. | x | |||||||||||||||

| Tentaculariidae | Nybelinia sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| – | - | - | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Acanthocephala | |||||||||||||||||||

| Echinorhynchida | Arhythmacanthidae | Heterosentis holospinus | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Heterosentis mongcai | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Heterosentis paraholospinus | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Cavisomatidae | Filisoma indicum | Filisoma hoogliense | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Neorhadinorhynchus atypicalis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neorhadinorhynchus nudum | Neorhadinorhynchus nudus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Echinorhynchidae | Acanthocephalus halongensis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Acanthocephalus parallelcementglandatus | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Echinorhynchus sp. | Metechinorhynchus sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Illiosentidae | Illiosentis sp. | Tegorhynchus sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchidae | Australorhynchus multispinosus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Cathayacanthus spinitruncatus | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Cleaveius longirostris | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cleaveius sp. | Mehrarhynchus sp. | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Gorgorhynchus tonkinensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Micracanthorhynchina kuwaitensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchus circumspinus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchus dorsoventrospinosus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchus hiansi | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchus johnstoni | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchus pacifcus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchus laterospinosus | x | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchus multispinosus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rhadinorhynchus trachuri | Nipporhynchus trachuri | x | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Transvenidae | Pararhadinorhynchus magnus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Sclerocollum neorubrimaris | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Quadrigyridae | Acanthocephalorhynchoides sp. | Pallisentis sp. | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Acanthogyrus (Acanthosentis) fusiformis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pallisentis (Brevitritospinus) vietnamensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pallisentis (Pallisentis) celatus | Neosentis celatus; Pallisentis (Neosentis) celatus | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchida | Neoechinorhynchidae | Neoechinorhynchus ampullata | x | ||||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchus (Hebesoma) manubrianus | Neoechinorhynchus manubriensis | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchus (Hebesoma) spiramuscularis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchus (Neoechinorhynchus) ascus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchus (Neoechinorhynchus) dimorphospinus | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchus (Neoechinorhynchus) johnii | Neoechinorhynchus johni | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchus (Neoechinorhynchus) longinucleatus | x | x | |||||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchus (Neoechinorhynchus) pennahia | x | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neoechinorhynchus (Neoechinorhynchus) plaquensis | x | ||||||||||||||||||

Note: No studies were done in brackish water fish in South Vietnam.

Abbreviation: W, wild; C, culture; x, parasite was reported; empty cells, information not available.

Fig. 1.

Distribution map of potentially pathogenic helminths in fish in Vietnam.

Fig. 2.

Distribution map of potentially zoonotic helminths in fish in Vietnam.

3.1. Digenean trematodes

Seventy-five studies recorded the occurrence of digenean trematodes with 148 species belonging to 37 families of 4 orders (Supplementary Table 1).

3.1.1. Zoonotic trematodes

Zoonotic trematodes of the families Heterophyidae, Opisthorchiidae, Echinochasmidae and Echinostomatidae were reported in freshwater fish throughout the country (Fig. 2). The heterophyids Centrocestus formosanus, Haplorchis taichui, Haplorchis pumilio, Procerovum varium, Haplorchis yokogawai, Heterophyopsis continua and Stellantchasmus falcatus were found to be the most frequently reported species (1.2–90%) (Thien et al., 2009; Madsen et al., 2015a), followed by the opisthorchiids Clonorchis sinensis in the North (2.5–76%) (Van et al., 2013; Bui et al., 2016) and Opisthorchis viverrini in Central and South Vietnam (4.3–74%) (Dung et al., 2014; Dao et al., 2017). The prevalence of these zoonotic parasites in cultured and wild-caught fish varied widely among and within regions and in different farming systems.

In cultured freshwater fish, the prevalence estimates of zoonotic flukes were lower in Central and South Vietnam than those in the North. In the North, the heterophyids including Haplorchis spp., C. formosanus, P. varium, H. continua, S. falcatus, the echinostomatids Echinostoma spp. as well as the opisthorchiid C. sinensis were commonly found in fish in integrated systems. In the Red River Delta, the overall prevalence of heterophyids and opisthorchiids recorded in multiple fish species was 72% (Phan et al., 2010b), whereas in multiple fish species stocked in household ponds and raised in a continuous production cycle, the prevalence was 65% (Phan et al., 2010a). In juvenile fish grown in earthen hatchery ponds located adjacent to households and farm animals, the prevalence reached 57% (Phan et al., 2010c), while cultured fish fed with wastewater in urban and rural farm ponds were infected at prevalences of 5.1% and 17%, respectively (Van De et al., 2012). In cultured fish in ponds fed with water from nearby small canals and closely located rice fields, the prevalence of heterophyids ranged from 32 to 90% (Madsen et al., 2015a). In caged fish raised in rivers, dams, and lakes, the prevalence of heterophyids was 26% (Hung et al., 2015). In the mountainous provinces, the prevalence of heterophyids in fish cultured in ponds was found similar to the prevalence reported in the Red River Delta region (46%) (Phan et al., 2016).

In the Centre, zoonotic flukes belonging to the heterophyid, echinostomatid and opisthorchiid families were found in fish of all stages in farm ponds, among which Haplorchis spp., C. formosanus and O. viverrini were most frequently reported. Prevalence estimates of the flukes in multiple cultured fish species were similar: 43% in fingerlings in nurseries ponds and 44% in mature fish in grown-out ponds (Chi et al., 2008), while the prevalence in giant mottled eel (Anguilla marmorata) in tanks was lower (9.0–10.6%) (Van Chu et al., 2014).

In the South, only heterophyids were reported with greatly varying prevalence estimates. In multiple juvenile fish species grown in earthen hatchery ponds, the prevalence was found to be 29% (Thien et al., 2009), while in monocultured juvenile giant gourami (Osphronemus goramy), it reached 48% (Thien et al., 2015). In contrast, in monocultured larger fish of the same species, the prevalence of these trematodes was only 1.7% (Thien et al., 2007). The prevalence of the flukes recorded in Sutchi catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) cultured in household ponds reached 8.7% (Thuy et al., 2011).

In wild-caught freshwater fish, the prevalence of zoonotic trematodes was found to be the highest in the North and Central region. In the North, the overall prevalence in fish caught from lakes and canals in the Red River Delta region was 69% (Hung et al., 2015), yet in the mountainous provinces, the prevalence of heterophyids in reservoirs and rivers was found to be lower (Phan et al., 2016). In wild-caught fish sold on local markets, the prevalence of C. sinensis was 69% (Dai et al., 2020), while the prevalence of heterophyids such as H. pumilio and C. formosanus, reached 85% and 68%, respectively (Chai et al., 2012). In the Centre, O. viverrini was found to be widespread, at a prevalence ranging between 13 and 74%, while high prevalences (80–90%) for both Echinostomatidae and Heterophyidae were also observed (Dao et al., 2017). In the South, the heterophyids H. pumilio and Procerovum sp. and opisthorchiid O. viverrini were reported in multiple fish species, at a prevalence of 30% (Thu et al., 2007).

In marine and brackish water fish, both cultured and wild-caught, a widespread occurrence of zoonotic flukes was reported in the North and Centre (Fig. 2). In the North, the heterophyids S. falcatus, P. varium and Stictodora lari were reported in the cultured brackish water four eyes sleeper (Bostrychus sinensis), at prevalences of 65%, 60%, and 35%, respectively, while in the wild-caught sleeper a prevalence of 93% was reported for S. falcatus and 77% for S. lari (Ha and Te, 2009). In the same report, the echinochasmid Echinochasmus sp. was reported at a prevalence of 22% (Ha and Te, 2009). In marine water cultured orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides), the prevalence of Centrocestus spp. ranged between 20 and 40% (Truong et al., 2017). In restaurants in Nam Dinh and Hanoi (North), where locally cultured fish or fish imported from neighbouring provinces are served as raw delicacy, the heterophyids C. formosanus, P. varium and H. continua were reported in marine fish, at an overall prevalence of 16% (Chi et al., 2009). In the Centre, only heterophyids were reported with prevalence estimates, however, being lower than those reported in the North (15% for P. varium and 6.0% for H. continua, respectively) (Vo et al., 2008). The prevalence estimates of heterophyids were higher in wild-caught fish than in cultured fish (2.7–75% vs. 2.0–15%) (Vo et al., 2008).

3.1.2. Non-zoonotic trematodes

Several non-zoonotic digeneans were reported in freshwater, brackish marine and marine water fish. In the North, Isoparorchis hypselobagri was reported in a variety of wild-caught freshwater fish (overall prevalence: 56%) (Ha et al., 2009; Shimazu et al., 2014), whereas Azygia spp. were found at a prevalence ranging between 5.3 and 20% (Ha et al., 2009). Moreover, Diplostomum spp. was reported in marine and brackish water cultured grouper (Epinephelus spp.) and sea bass (Lates calcarifer) (Chi et al., 2009); and Stephanostomum spp. in various cultured and wild-caught marine fish (Ngo et al., 2009, 2011; Ha and Ngo, 2010; Truong et al., 2017). Furthermore, bucephalid trematodes were reported in both freshwater and marine fish: Prosorhynchus spp. were commonly found in cultured and wild-caught groupers (37% and 13%, respectively) in the North and Centre (Vo et al., 2011; Truong et al., 2016, 2017); Bucephalus polymorphus in cultured sea bass in the Centre (Glenn et al., 2010); while Prosorhynchoides was commonly recorded in cultured catfish (Pangasius spp.) (13–23%) in the South (Thuy and Buchmann, 2008b; Thuy et al., 2011). Transversotrema patialense was found in cultured grouper in marine and brackish water in the North and Centre (Vo et al., 2011; Truong et al., 2017). Moreover, the blood fluke Psettarium anthicum was found in the heart of sea caged cobia (Rachycentron canadum) in the Centre (Warren et al., 2017) while Nomasanguinicola canthoensis was identified in branchial vessels of wild-caught catfish (Clarias macrocephalus) sold on a fish market in Can Tho province (South) (Truong and Bullard, 2013).

Additionally, some less common digenea were recorded in the North, namely: species of the families Aspidogastridae, Cephalogonimidae, Cryptogonimidae, Derogenidae, Gorgoderidae, Haploporidae, Lissorchiidae, Microphallidae and Orientocreadiidae in freshwater fish (Duc et al., 2009; Ha et al., 2009); and species of the families Aephnidiogenidae, Apocreadiidae, Bivesiculidae, Cryptogonimidae, Derogenidae, Didymozoidae, Faustulidae, Fellodistomidae, Gorgoderidae, Haploporidae, Haplosplanchnidae, Hemiuridae, Lecithasteridae, Lepocreadiidae, Monorchiidae, Opecoelidae and Sclerodistomidae in marine fish (Ngo et al., 2009, 2011; Besprozvannykh et al., 2016; Atopkin et al., 2017, 2019; Truong et al., 2017). In the Centre, some trematode species belonging to the family Strigeidae were found in freshwater fish (Poddubnaya et al., 2010); whereas species of the families Aspidogastridae, Bivesiculidae, Callodistomidae, Cryptogonimidae, Didymozoidae, Haploporidae, Hemiuridae, Lecithasteridae, Lecithodendriidae, Microphallidae, Opecoelidae and Philophthalmidae were reported in brackish and marine water fish (Hai, 2009; Glenn et al., 2010; Te et al., 2010; Vo et al., 2011; Tuan et al., 2015; Zhokhov et al., 2018; Atopkin et al., 2020). In the South, some digeneans of the families Strigeidae, Cryptogonimidae, Lissorchiidae were found in freshwater fish (Sokolov et al., 2020; Thu et al., 2007; Sokolov and Gordeev, 2019); while no trematodes were reported in brackish and marine fish.

3.2. Monogeneans

In 25 studies covering all 3 regions, 62 monogenean species belonging to 14 families of 4 orders were reported (See Supplementary Table 1). Although a widespread occurrence of pathogenic monogeneans was reported, very few monogenean species were found in freshwater fish and there was only 1 record on the occurrence of monogeneans in brackish water fish (Te et al., 2010). In freshwater fish, high prevalences of Dactylogyrus spp. and Gyrodactylus spp., ectoparasitizing the skin and the gills of cultured fish were recorded: 40% for both Dactylogyrus and Gyrodactylus in fingerling grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) in the North (Van et al., 2015); 70% for Dactylogyrus in cultured catfish (P. hypophthalmus) and 45% for Gyrodactylus in Oreochromis spp. in the South (Thuy, 2005; Nguyen Hoang and Campet, 2009); while in farmed roach fish (Cyprinus centralus) in the Centre, much lower prevalence estimates of 0.8% and 1.3% were found for Dactylogyrus sp. and Gyrodactylus sp., respectively (Te et al., 2010). Moreover, a high prevalence of Pseudodactylogyrus spp. was reported in cultured giant mottled eel (A. marmorata) in the Central region (66%), while in wild-caught glass eel, it was only 1.7% (Van Chu et al., 2014). In the Mekong Delta region, Thaparocleidus spp. were commonly found in cultured catfish (Pangasius spp.) (Pariselle et al., 2005; Thuy and Buchmann, 2008a; Thuy et al., 2011).

A more diverse group of monogenean ectoparasite species was identified in marine fish. In the North, the capsalid Benedenia sp. was found at a prevalence of 5.7% and diplectanids Psedorhabdosynochus spp. at a prevalence of 88% in cultured groupers, while in the wild-caught fish, the prevalence of these parasites was lower (56%) (Truong et al., 2017). In wild-caught fish in the North, the prevalence of monogeneans, including the pathogenic dactylogyrids Ancyrocephalus spp., Haliotrema spp. and diplectanids Diplectanum spp., ranged between 34% and 50% (Ngo et al., 2009, 2011). In the Centre, the overall prevalence of the capsalids Neobenedenia and Benedenia parasitizing the body surface of grouper and snapper in the region was 71% (Hoa and Van Ut, 2007). In sea fish, dactylogyrids Haliotrema spp. were found in caged grouper (2.2–15%) (Dang et al., 2010); and Ancyrocephalus spp. and Haliotrema spp. in wild-caught ornamental fish (Chaetodon spp., Parupeneus multifasciatus) (Hai, 2009; Tuan et al., 2015). Furthermore, diplectanids Psedorhabdosynochus spp. were recorded at a prevalence ranging between 7.0 and 27% in caged grouper, and 32% in wild-caught grouper (Dang et al., 2013). In the South, the presence of dactylogyrids Metahaliotrema spp. was reported in caged spotted scat (Scatophagus argus) (Kritsky et al., 2016).

Some less common monogeneans such as species of the families Gastrocotylidae, Heteraxinidae, Microcotylidae, Paramonaxinidae and Protogyrodactylidae (North) (Ngo et al., 2009, 2011; Kritsky et al., 2016); and species of the families Axinidae, Bothitrematidae and Heteraxinidae (Centre) (Tuan et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2016, 2020a), were also recorded in marine fish.

3.3. Nematodes

Thirteen nematode species belonging to 9 families of 3 orders were reported in 10 studies (See Supplementary Table 1). In the North, a general prevalence of 16% was reported in cultured freshwater fish; however, species identification was not established (Nguyen Van and Nguyen Van, 2004). In another study in cultured and wild-caught grouper (Epinephelus spp.) in the same region, Capillaria sp. (5.0%), Ascarophis sp. (60%), Hysterothylacium spp. (3.3–5.0%), Raphidascaris sp. (16%) and Philometra spp. (1.9–6.7%), were reported (Truong et al., 2017). In various wild-caught marine fish, the zoonotic Capillaria spp. and Anisakis spp. were found at prevalences of 65% (Ngo et al., 2009). In the Centre, Camallanus spp. (15–42%), Spirocamallanus istiblenni (13–90%) and Hysterothylacium sp. (10.0–56%), were reported in wild-caught ornamental fish (Parupeneus spp., Amphiprion spp.) (Tuan et al., 2015; Zhokhov et al., 2018, 2020), whereas in the South, the zoonotic G. spinigerum was found in cultured swamp eels (Monopterus albus) at a prevalence ranging between 0.8 and 19% (Sieu et al., 2009).

3.4. Cestodes

Six studies reported the occurrence of namely 5 cestode species belonging to 6 families of 6 orders in fish in Vietnam (See Supplementary Table 1). In the North, a general prevalence of 12% was reported in a study in farmed freshwater fish; however, no species identification was established (Nguyen Van and Nguyen Van, 2004). In the Centre, some parasitic cestodes were found in sea fish, such as Tylocephalum sp. in cultured sea bass (L. calcarifer); and Proteocephalus sp., Pterobothrium sp. and Nybelinia sp. in wild-caught ornamental fish (Hai, 2009; Glenn et al., 2010; Zhokhov et al., 2020). The tapeworm S. acheilognathi was reported in cultured Mekong catfish (P. hypophthamus) in the South at a prevalence of 0.6% (Hung, 2010).

3.5. Acanthocephala

Thirty studies recorded the occurrence of 30 thorny-headed worm species belonging to 8 families of 3 orders (See Supplementary Table 1). All studies, covering the 3 regions, were conducted in wild-caught fish, apart from one study in cultured fish in the North reporting a general prevalence of acanthocephalans of 7.7% (Nguyen Van and Nguyen Van, 2004). The acanthocephalan species found in marine fish outnumbered those found in freshwater fish. There were no reports on acanthocephalans in brackish water fish. In the North, Pallisentis (Pallisentis) celatus (11–48%), Pallisentis (Brevitritospinus) vietnamensis (9.8%), Acanthocephalorhynchoides sp. (3.3%), Cleaveius longirostris (8.3%) were reported in freshwater fish (Amin et al., 2004; Ha et al., 2009). The group of acanthocephalan species identified in marine fish in the North was more diverse than in other regions. The overall prevalence of Acanthocephalus halongensis; Gorgorhynchus tonkinensis; Rhadinorhynchus dorsoventrospinosus; Neorhabdinorhynchus spp. in various fish hosts was 2.0% (Ngo et al., 2011), while in another study, the prevalence of Illiosentis sp. only was 18% (Ngo et al., 2009). Other common acanthocephalans reported in the region included Rhadinorhynchus spp., Neoechinorhynchus spp. and Heterosentis spp. (Amin et al., 2011, 2014, 2019d; Ha et al., 2018). In the Centre, the presence of Acanthocephalus parallelcementglandatus and Neoechinorhynchus (Hebesoma) spiramuscularis was reported in only one study conducted in freshwater fish (Amin et al., 2014). The following families were recorded in marine fish: Arhythmacanthidae, Cavisomatidae, Echinorhynchidae, and Neoechinorhynchidae, Rhadinorhynchidae and Transvenidae (Amin et al., 2018a, b, 2019c). In the South, only acanthocephalans of the following families were reported in marine fish: Cavisomatidae, Neoechinorhynchidae, Quadrigyridae and Rhadinorhynchidae (Amin et al., 2014, 2019a, b, e).

4. Discussion

As shown in this review, a wide variety of helminth species, including zoonotic and pathogenic species, are parasitizing wild and cultured fish in different environments in Vietnam. Zoonotic trematodes belonging to the families Echinostomatidae, Echinochasmidae, Heterophyidae and Opisthorchiidae were widely reported in fish collected throughout the country. Heterophyid species (Haplorchis spp., Procerovum sp., C. formosanus) were predominant, and were commonly reported in cultured and wild-caught freshwater, brackish water and marine fish, including the cultured Pangasius spp., one of the most important export aquaculture commodities in Vietnam (Thu et al., 2007; Thuy et al., 2011; Madsen et al., 2015b). Several factors contribute to the transmission of these parasites in Vietnam. For instance, the widespread culinary habit to consume raw fish (Phan et al., 2011), which is increasingly being considered a “healthy food”, is posing a significant threat to public health. Moreover, snails belonging to the families Thiaridae and Bithyniidae, which act as the intermediate hosts for intestinal and liver trematodes (Le, 2000; Dung et al., 2010; Phan et al., 2010b; Dao et al., 2017), are common in Vietnam. Additionally, the contamination of the fish farming environment with zoonotic trematode eggs from definitive hosts (humans as well as fish-eating birds and domestic animals such as pigs, dogs, cats and poultry) is playing an important role in the epidemiology of zoonotic flukes (Olsen et al., 2006; Lan Anh et al., 2009; Anh et al., 2010). Therefore, strategies aiming to control food-borne zoonotic trematodes in fish farming communities should both address sanitation and management of animals in the vicinity of fish farms. Zoonotic heterophyid and echinostomatid species were also commonly reported in both cultured and wild marine/brackish fish, where, however, studies investigating the life cycle or the occurrence of the intermediate snail hosts of these trematodes in marine or brackish water in Vietnam are lacking up to now. Conducting epidemiological research on the vectors is paramount, in order to effectively control these zoonotic parasites.

The geographical distribution of the zoonotic opisthorchiids C. sinensis and O. viverrini in intermediate fish hosts found in this study is in agreement with the distribution of these trematodes in humans. Indeed, clonorchiasis is endemic in the North region (Dang et al., 2008), where it has been reported in 21 provinces and where more than one million people were estimated to be infected (Qian et al., 2012; Sithithaworn et al., 2012). The reported prevalence in humans ranged from 0.2% to 40.4%, and infection is associated with the consumption of raw fish (De et al., 2003; Nguyen et al., 2020b). On the other hand, O. viverrini infection in humans is endemic in Central Vietnam. In 2003, a high prevalence (36.9%) of opisthorchiasis was reported, based on faecal examination (De et al., 2003), yet a more recent survey reported a prevalence of only 11.4%, using a molecular approach (Dao et al., 2016). Although human infections with intestinal flukes have been reported in Vietnam (Olsen et al., 2006; Dung et al., 2007; De and Le, 2011), the finding of the widespread occurrence of C. sinensis in humans in North Vietnam seems contradictory to the predominance of zoonotic heterophyid/echinostomatid species in fish as summarized in this review. As the morphology of heterophyid and opisthorchiid eggs is quite similar, the diagnosis of human fluke infections based on coprological methods can be challenging, thus hampering the characterization of the true distribution of both trematode families (Johansen et al., 2015). The high prevalence of heterophyid/echinostomatid flukes in fish hosts found in this study, suggests that the number of human infections with intestinal flukes may have been overlooked and may actually be higher than human liver fluke cases.

Next to the zoonotic digenea, a number of studies reported the presence of non-zoonotic digenea, causing a serious threat to aquaculture, as these parasites potentially cause severe mortality, subsequently leading to significant economic losses. For instance, the heterophyid C. formosanus was reported to cause morbidity and mortality in cultured and wild-caught cichlids, cyprinids and characids in many parts of the world (Mitchell et al., 2000; Scholz and Salgado-Maldonado, 2000; Ramadan et al., 2002; Gjurčević et al., 2007; Ortega et al., 2009; Arguedas et al., 2010; Mehrdana et al., 2014), and this species was found at high prevalences in freshwater fish in Vietnam.

Among reported pathogenic monogenean ectoparasites were some species of the families Capsalidae, Diplectanidae and Gyrodactylidae, which mainly parasitize the gills and skin of marine and freshwater fish and are known to cause significant economic losses in the marine and freshwater fish industry in Asia (Whittington et al., 2001; Rohde, 2005), Australia (Deveney et al., 2001; Ernst et al., 2002) and Europe (Bakke et al., 2004; Dezfuli et al., 2007). The economically important marine and freshwater fish species such as, grouper (Epinephelus spp.), seabass (L. calcarifer), cobia (R. canadum), snapper (Lutjanus argentimaculatus), mullet (Mugil cephalus), cyprinids, rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and catfish (Pangasius spp.) were most affected by these ectoparasites. Their occurrence potentially affects fish quality and marketability. Although ectoparasites seldomly cause heavy infection in wild fish, in cultured fish kept in confined spaces such as ponds or hatcheries, with high fish densities and polluted water, parasitic monogenea can thrive and cause poor growth and mortality (Thoney and Hargis Jr, 1991). Opportunistic pathogens such as bacteria can then take advantage of the lesions caused by the ectoparasites, which may lead to heavy stock losses (Zhang et al., 2015). Preventing the introduction of pathogenic monogenea in culture ponds, especially at the fingerling stage, via screening of the stock, is thus crucial to reduce economic losses.

Among the parasitic nematodes in fish reported in this review, some of them (e.g. species of the families Capillariidae, Anisakidae, Gnathostomatidae, Raphidascarididae, Camallanidae and Philometridae) may exert a negative impact on public health and commercial fish production. However, species determination remains a restriction in the investigation of fish nematodes, as observed in this study. The zoonotic G. spinigerum reported in swamp eels; and Anisakis sp., Capillaria spp. and Hysterothylacium spp. recorded in grouper and various marine fish species, served raw in restaurants may affect human health. G. spinigerum, for instance, is endemic in Japan and Southeast Asian countries, and infections are commonly found in returning travelers in non-endemic regions (Herman and Chiodini, 2009). This nematode causes disease when larvae migrate through tissues, commonly the skin and subcutaneous tissues (Bravo and Gontijo, 2018). Infection with the roundworm C. philippinensis (McCarthy and Moore, 2000), may have a serious health impact and even cause mortality in case of autoinfection, due to the ability of these parasites to multiply and reproduce within the human host, and consequently re-invade the intestinal mucosa (Intapan et al., 2017). Furthermore, some Anisakis species (A. simplex, A. physeteris, A. pegreffii) can induce tissue damage due to the larval penetration of the stomach and intestine and by strong allergic reactions in humans (Caramello et al., 2003; Mattiucci and Nascetti, 2008). Some of the allergens are pepsin and heat-resistant, thus inducing a reaction even upon ingestion of cooked or canned food (Caballero and Moneo, 2004). Although the zoonotic potential of Hysterothylacium spp. of the family Raphidascarididae is still controversial, the parasites share antigens with A. simplex and are known to induce allergic reactions in humans following ingestion of infected fish (Valero et al., 2003).

The occurrence of other non-zoonotic, yet pathogenic nematode species of the families Philometridae, Raphidascarididae, Anisakidae, or Camallanidae in various marine fish species, including grouper and ornamental fish, poses a threat to the marine fish industry. Philometra spp. are well-known pathogenic nematodes that infect gonads, thus affecting reproduction of commercially important fish species in various geographical areas worldwide (Clarke et al., 2006; Séguin et al., 2011; Selvakumar et al., 2015, 2016; Ali and Afsar, 2018; Innal et al., 2020). The raphidascaridids Hysterothylacium spp. and Raphidascaris spp. are known to cause intestinal obstruction, gut damage or liver destruction, and even mortality in heavily infected fish thus resulting in economic losses (Szalai and Dick, 1991; Balbuena et al., 2000; Corral et al., 2018). Tissue migration of anisakid worms may induce severe inflammatory reactions and deformation, leading to potentially detrimental effects on fish (Buchmann and Foojan, 2016). Anisakis spp. and Hysterothylacium spp. may also cause economic losses due to the presence of macroscopic larvae in fish viscera and muscle leading to consumer aversion, rejection and reduced marketability of commercial fish products (Karl, 2008). Finally, the high prevalence of the camallanid blood-feeders reported in wild-caught coral reef fish (Parupeneus spp., Amphiprion spp.) is likely to exert negative effects on the ornamental fish industry resulting from physiological damage, rectal destruction, anaemia, emaciation and mortality (Moravec et al., 2006; Morey and Florindez, 2018). Overall, pathological effects caused by helminths may reduce fish performance or appearance as colour changes might occur, as well as mechanical damages or decreased reproductive performance, potentially resulting in a great loss (Dewi and Fadhilla, 2018). In the ornamental fish industry in particular, this is problematic as pet fish keeping is becoming increasingly popular and a growing source of employment (Bruckner, 2005). Additionally, as Vietnam is one of the important suppliers of ornamental fish for the global market (Wood, 2001), the accidental introduction of exotic parasites and infective fish hosts into new areas outside Vietnam, may lead to adverse effects on native fish populations and potentially economic losses (Evans and Lester, 2001; Kim et al., 2002; Lymbery et al., 2014).

Six cestode species of the families Bothriocephalidae, Lecanicephalidae, Proteocephalidae, Rhinebothriinae and Pterobothriidae were reported in Vietnamese fish. S. acheilognathi (formerly Bothriocephalus acheilognathi), known to pose a serious threat for wild and cultured fish worldwide due to its high pathogenicity and low host specificity (Heckmann, 2009; Scholz et al., 2012), was found in cultured catfish, a commercially important aquaculture target of Vietnam. The infection induced by this highly invasive species is not only potentially fatal to cultured fish, resulting in economic loss (Han et al., 2010), S. acheilognathi has also been documented to potentially parasitize humans (Yera et al., 2013). Furthermore, the trypanorhynch cestode Pterobothrium sp. is known to have an economic impact due to the repugnant appearance of infected fish resulting in fish disposal and subsequent financial loss (da Fonseca et al., 2012; Zuchinalli et al., 2018; Oliveira et al., 2019). Although this species was found only in wild-caught ornamental fish (Chaetodon spp.), its presence raises concerns about the potential negative impacts on edible fish living in the same environment.

A variety of species of the acanthocephalan families was reported in marine and freshwater fish in Vietnam. Previously, a checklist of acanthocephalan species in vertebrates in Vietnam, according to the classification of Amin, was published (Van et al., 2015). In this review, we updated this checklist with additional records on thorny-headed worms collected from fish. Among the acanthocephalans found, species of the genus Neoechinorhynchus and Acanthocephalus, which are known to induce mechanical damage resulting from penetration of the armed proboscis in the digestive tract (Raina and Koul, 1984; Sakthivel et al., 2016; de Matos et al., 2017; Langer et al., 2017) and likely resulting in financial losses (Silva-Gomes et al., 2017), were reported in various marine and freshwater fish in the country. These retrieved records focused only on the morphological description and classification of the acanthocephala species found in the fish hosts and not on their pathological effects.

The lengthy coastline and numerous rivers, lakes and reservoirs favor the expansion of Vietnam's commercial cage fish production. However, open net/cage systems may facilitate pathogen exchange from farmed fish to adjacent wild fish population and vice versa in the water environment. Wild fishes act as a reservoir for parasites that may infect other wild fish or farmed fish populations or enhance reinfection rates within the farms through spillback facilitated by the flow-through farming systems (Hayward et al., 2011; Barrett et al., 2019). On the other hand, overcrowded intensive farming conditions are known to amplify parasite loads significantly, thus worm burdens in cultured fish may be higher than those in wild fish, potentially causing parasite transmission from cultured to wild populations (Alves and Taylor, 2020). In addition, aquaculture is a known driver for the introduction of exotic parasites into new ecosystems, via trade and movements of live animals, which may put native fish populations at risk. For instance, the monogenea Gyrodactylus salaris has threatened wild salmon populations in Norwegian rivers following its introduction from Sweden via Atlantic salmon stocks resulting in massive economic loss (Mo et al., 2004). Moreover, the import of Asian eels Anguilla japonica from Japan to Europe has caused the introduction of the nematode Anguillicoloides crassus, partly contributing to a decline of wild European eel Anguilla anguilla populations (Kirk, 2003). In Vietnam, several new fish species have been introduced over the past two decades following the growth of the domestic aquaculture (FAO, 2020). In addition, the uncontrolled import of young stocks from China for cultivation in Vietnam is raising concerns on new parasite transmission putting native populations at stake (Kalous et al., 2012). Therefore, without improved mitigation measures such as establishment of free zones or improved legislation preventing the movement of animals from regions with unknown infection status, disease emergence as a result of non-native pathogen introduction will continue, with potentially negative effects on local ecosystems. We believe that reviews like this one can be valuable to identify current and potential pathogen-related problems in aquaculture and fisheries.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, we chose to report the overall prevalence of each helminth species per study, instead of presenting parasite prevalence for the separate fish species collected in the study, due to a large variety in fish host species (213 species) being sampled in the retrieved records. Secondly, some helminths species reported may have been incorrectly identified, due to difficulties arising from the morphological identification of digenean metacercariae. For instance, the morphology of trematode metacercariae is quite similar for several intestinal flukes and liver flukes (Scholz et al., 1991), thus requiring experimental infections in potential definitive hosts to obtain adult worms with fully developed internal organs, yet, only eleven out of 39 studies where metacercariae were found reported such procedures. Finally, despite of our efforts to retrieve all the published records on helminth infections in fish in Vietnam, we might have missed reports due to publication in local journals or use of a language different from English or Vietnamese.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review summarized recent knowledge on the distribution of parasites in fish hosts in Vietnam. A variety of zoonotic heterophyids was commonly reported in freshwater, marine and brackish water fish, including in cultured Pangasius spp., important export aquaculture targets of the country, while opisthorchiids C. sinensis and O. viverrini were reported in freshwater fish in the North, Central and South Vietnam, respectively. Moreover, various potentially pathogenic digeneans, as well as highly pathogenic monogeneans of the families Capsalidae, Diplectanidae and Gyrodactylidae were found in freshwater, marine and brackish water fish. Furthermore, the zoonotic nematodes G. spinigerum, Anisakis sp., Capillaria spp. and Hysterothylacium spp. were recorded in various marine fish species. Other potentially pathogenic nematodes were found, such as Philometra spp. in cultured catfish and camallanids in marine ornamental fish. The pathogenic tapeworm S. acheilognathi was also reported in cultured catfish. Finally, some thorny-headed worms of the genera Neoechinorhynchus and Acanthocephalus with pathogenic potential were found in marine fish. In this review, helminth species were reported for only nine percent of the more than 2400 species of fish hosts occurring in the waters of Vietnam. It is suggested that the diversity and richness of the parasitic faunain fish is extremely high and it is necessary to expand the research on parasitic fauna to a larger group of fish species, to obtain a comprehensive picture on helminth infections in Vietnam, considering the prioritisation of aquaculture as a part of the economic development strategy of the Vietnamese government.

Funding

This work was supported by the Directorate General for Development Cooperation (DGD) Belgium under the form of a scholarship (TH Nguyen) for the collaborative Master of Science in Tropical Animal Health of the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp, Belgium and the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2020.12.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Fig. S1.

Flow diagram of the study selection

References

- Ali M., Afsar N. A report of occurrence of gonad infecting nematode Philometra (Costa, 1845) in host Priacanthus sp. from Pakistan. Int. J. Biol. Biotechnol. 2018;15:575–580. [Google Scholar]

- Allison E.H. The WorldFish Center; Penang, Malaysia: 2011. Aquaculture, Fisheries, Poverty And Food Security; p. 60. Working Paper 2011-65. [Google Scholar]

- Alves M.T., Taylor N.G. Models suggest pathogen risks to wild fish can be mitigated by acquired immunity in freshwater aquaculture systems. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64023-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M. Classification of the acanthocephala. Folia Parasitol. 2013;60:273–305. doi: 10.14411/fp.2013.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Anshu C., Heckmann R.A., Ha N.V., Singh H.S. The morphological and molecular description of Acanthogyrus (Acanthosentis) fusiformis n. sp. (Acanthocephala: Quadrigyridae) from the catfish Arius sp. (Ariidae) in the Pacific Ocean off Vietnam, with notes on zoogeography. Acta Parasitol. 2019;64:779–796. doi: 10.2478/s11686-019-00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Ha N.V., Ha D.N. First report of Neoechinorhynchus (Acanthocephala: Neoechinorhynchidae) from marine fish of the eastern seaboard of Vietnam, with the description of six new species. Parasite. 2011;18:21–34. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2011181021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Heckmann R.A., Dallarés S., Constenla M., Ha N.V. Morphological and molecular description of Rhadinorhynchus laterospinosus Amin, heckmann & ha, 2011 (acanthocephala, Rhadinorhynchidae) from marine fish off the pacific coast of Vietnam. Parasite. 2019;26:14. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2019015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Heckmann R.A., Ha N.V. Acanthocephalans from fishes and amphibians in Vietnam, with descriptions of five new species. Parasite. 2014;21:53. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2014052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Heckmann R.A., Ha N.V. Descriptions of Acanthocephalus parallelcementglandatus (Echinorhynchidae) and Neoechinorhynchus (N.) pennahia (Neoechinorhynchidae) (acanthocephala) from amphibians and fish in central and pacific coast of Vietnam, with notes on N. (N.) longnucleatus. Acta Parasitol. 2018;63:572–585. doi: 10.1515/ap-2018-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Heckmann R.A., Nguyen Van H. Descriptions of Neorhadinorhynchus nudum (cavisomidae) and Heterosentis paraholospinus n. sp. (Arhythmacanthidae) (acanthocephala) from fish along the pacific coast of Vietnam, with notes on biogeography. J. Parasitol. 2018;104:486–495. doi: 10.1645/17-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Heckmann R.A., Nguyen Van H. Descriptions of two new acanthocephalans (Rhadinorhynchidae) from marine fish off the Pacific coast of Vietnam. Syst. Parasitol. 2019;96:117–129. doi: 10.1007/s11230-018-9833-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Heckmann R.A., Van Ha N. On the immature stages of Pallisentis (Pallisentis) celatus (Acanthocephala: Quadrigyridae) from occasional fish hosts in Vietnam. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2004;52:593–598. [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Rubtsova N.Y., Ha N.V. Description of three new species of Rhadinorhynchus luhe, 1911 (acanthocephala: Rhadinorhynchidae) from marine fish off the pacific coast of Vietnam. Acta Parasitol. 2019;64:528–543. doi: 10.2478/s11686-019-00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin O.M., Sharifdini M., Heckmann R., Ha N.V. On three species of Neoechinorhynchus (acanthocephala: Neoechinorhynchidae) from the pacific ocean off Vietnam with the molecular description of Neoechinorhynchus (N.) dimorphospinus Amin and sey, 1996. J. Parasitol. 2019;105:606–618. doi: 10.1645/19-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anh N.T.L., Madsen H., Dalsgaard A., Phuong N.T., Thanh D.T.H., Murrell K.D. Poultry as reservoir hosts for fishborne zoonotic trematodes in Vietnamese fish farms. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;169:391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]