Highlights

Highly crystalline Mn2O3 materials with tunable pore sizes are obtained and employed as high-performance cathode materials for reversible aqueous Zn-ion battery.

The Zn/Mn2O3 battery exhibits significantly improved rate capability and remarkable cycling durability due to the introduction of nanoporous architecture.

The Zn2+/H+ intercalations mechanism is put forward for the Zn/Mn2O3 battery.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40820-019-0351-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Porous Mn2O3, High-rate capability, Zn-ion battery, Cathode material, Zn-storage mechanism

Abstract

Manganese oxides are regarded as one of the most promising cathode materials in rechargeable aqueous Zn-ion batteries (ZIBs) because of the low price and high security. However, the practical application of Mn2O3 in ZIBs is still plagued by the low specific capacity and poor rate capability. Herein, highly crystalline Mn2O3 materials with interconnected mesostructures and controllable pore sizes are obtained via a ligand-assisted self-assembly process and used as high-performance electrode materials for reversible aqueous ZIBs. The coordination degree between Mn2+ and citric acid ligand plays a crucial role in the formation of the mesostructure, and the pore sizes can be easily tuned from 3.2 to 7.3 nm. Ascribed to the unique feature of nanoporous architectures, excellent zinc-storage performance can be achieved in ZIBs during charge/discharge processes. The Mn2O3 electrode exhibits high reversible capacity (233 mAh g−1 at 0.3 A g−1), superior rate capability (162 mAh g−1 retains at 3.08 A g−1) and remarkable cycling durability over 3000 cycles at a high current rate of 3.08 A g−1. Moreover, the corresponding electrode reaction mechanism is studied in depth according to a series of analytical methods. These results suggest that rational design of the nanoporous architecture for electrode materials can effectively improve the battery performance.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40820-019-0351-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Nowadays the development of new energy has become a hot issue under the background of the fast depletion and severe deterioration of non-renewable fossil fuels, and the in-depth study of advanced battery materials is crucial to meet the growing requirements for sustainable energy consumption [1–4]. Lithium ion batteries (LIBs) have been widely applied in the past decades because of their high energy density and considerable cycle retention; however, they still face the severe challenges of environmental pollution, high cost, safety concerns and resource limitation [5–10]. Recently, a series of rechargeable aqueous batteries employing alkaline cations such as Na+, Mg2+, Al3+ and Zn2+ as charge carriers have been studied because of their low cost and material abundance [11–18]. Among these batteries, aqueous Zn-ion batteries (ZIBs) exhibit high volumetric capacities and low redox potential, which suggests that ZIB is a prospective alternative of LIBs [19–22]. However, the use of ZIBs is still far away from practical applications because it is difficult to obtain a proper cathode material as the host for storage of Zn ions. Prussian blue analogues and vanadium-based materials are considered as potential cathode materials in ZIBs, whereas the former exhibits respectable cycling performance but limited capacities, and the latter delivers high capacities but low operating voltage [23–26]. Therefore, it is desirable to develop high-capacity ZIBs cathode materials.

Recently, manganese oxides are regarded as one of the most promising cathode materials in ZIB because of its high theoretical capacity and reversibility. Among them, Mn2O3 has drawn extensive attention due to its higher energy density. However, obstructed by unavoidable changes in volume during charging/discharging process, the Mn2O3 electrodes always exhibit low specific capacity and unsatisfactory rate capability [27, 28]. As we know, the construction of porous architectures is considered to be an effective way to alleviate volume expansion during electrochemical processes. Moreover, porous structures are able to provide a short path for ion diffusion and the increased surface area can offer more reaction sites between active materials and electrolytes, which synergistically guarantee the cyclic stability and rate capability of aqueous batteries [29–31]. Inspired by the previous reports that the participation of porous structure contributes to the improvement in battery performance, the synthesis of porous Mn2O3 cathode materials with large surface areas, high crystallization degree and tunable pore sizes may provide a new perspective for the development of rechargeable aqueous zinc batteries. However, only few reports are available on porous manganese oxide synthesized by conventional soft-templating strategy, because the complicated stable oxidation states of manganese make it difficult to control the interaction between the precursors and the micelles [32, 33]. Meanwhile, porous MnOx obtained by hard-templating method is hard to control over the pore sizes and suffers the limitation of high cost and low yield [34]. Hence, developing highly efficient and stable porous Mn2O3 cathode for ZIBs remains a challenge.

Herein, we demonstrate an efficient strategy to prepare nanoporous Mn2O3 architecture with controllable pore sizes, high crystallinity and large specific surface areas by a ligand-assisted self-assembly process employing citric acid as coordination agent. The different coordination degree between Mn2+ and citric acid ligand plays a key role in determining the crystallite sizes of mesoporous Mn2O3. The obtained Mn2O3 possesses tunable mesoporous architectures, pore sizes (3.2–7.3 nm) and specific surface areas (55–260 m2 g−1) with different molar ratio of Mn2+ to citric acid ligand. The resultant mesoporous Mn2O3 materials were employed as cathode materials in aqueous rechargeable ZIBs, and the electrochemical performances of the materials with various pore structures were investigated comparatively. It is worth noting that the discharge capacity improved greatly with the increase in the surface areas. Benefiting from the unique porous structure and high crystallinity, the battery shows high reversible capacity (~ 233 mAh g−1 at a current density of 0.3 A g−1), superior rate capability (162 mAh g−1 retains at 3.08 A g−1) and remarkable cycle stability over 3000 cycles in a mild aqueous electrolyte battery system. Moreover, the battery reaction mechanism was revealed via multiple analytical methods.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of Mesoporous Mn2O3

For the typical synthesis of MMO-7.3, 0.8 g of Pluronic P123 was dissolved in 7.0 mL n-butanol solvent, followed by adding 0.7 mL concentrated HNO3 to adjust the pH value under magnetic stirring. Then, 0.961 g citric acid was added, and after stirring for 1 h, 0.635 g inorganic source Mn(NO3)2·4H2O was added. The above suspension was stirred for over 2 h at room temperature and until the suspension forms transparent light yellow solution. Then, the solution was poured into a Petri dish (diameter 90 mm) to evaporate the solvent at 100 °C for 4 h. For the calcination process, the prepared brown powder product was scraped and then heated to 350 °C for 2 h under air atmosphere, leading to the highly crystalline mesoporous Mn2O3 product.

Electrochemical Measurements

As-synthesized material, ketjen black and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were mixed at a weight ratio of 7:2:1 in NMP. Subsequently, the slurry was cast onto carbon paper and dried at 80 °C under vacuum for 12 h to prepare the cathodes. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were taken on a CHI 660e electrochemical station at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1. Electrochemical measurements were taken on the CR2032 coin cells using zinc foils as an anode and glass fiber as a separator. The hybrid aqueous solution with 2 mol L−1 ZnSO4 and 0.2 mol L−1 MnSO4 was used as the electrolyte. Galvanostatic charge/discharge test was performed on a LAND CT2001A.

Results and Discussion

Morphology, Phase and Structure Analysis of Porous Mn2O3

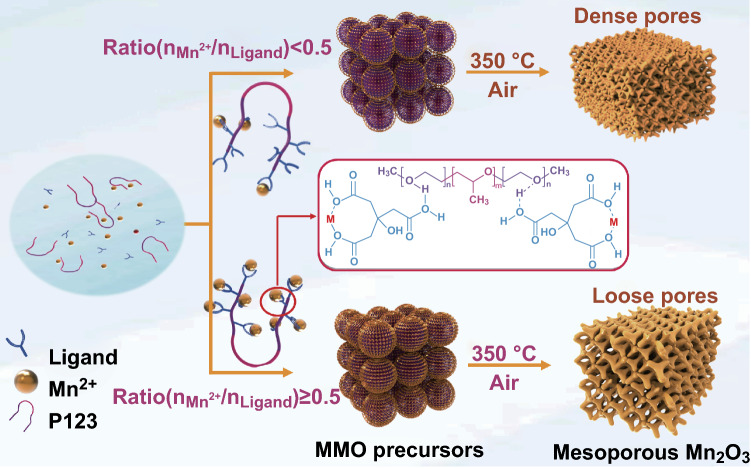

The illustration of formation mechanism for mesoporous Mn2O3 is shown in Fig. 1. In the ligand-assisted self-assembly process, porous Mn2O3 was synthesized by using Mn(NO3)2·4H2O as the metal source, citric acid as the coordination agent, Pluronic P123 as a soft template and n-butanol as a solvent, respectively. During the reaction, Mn2+ is connected with citric acid through coordination bonds, and citric acid and polyethylene oxide (PEO) chains are linked by hydrogen bonds. The synergistic effect of these two kinds of chemical bonds guarantees the controllable self-assembly process and contributes to the formation of well-defined mesostructure (Fig. S1). When the molar ratio of Mn2+ to citric acid is less than 0.5, the metal ions are in a non-full coordination state. In this process, the higher proportion of ligand and the higher coordination degree between Mn2+ and ligands are achieved; consequently, the larger metal precursors are obtained. When the molar ratio of Mn2+ to citric acid is greater than or equal to 0.5, the Mn2+ is in full coordination, so the coordinated metal precursors will not further grow up anymore. After calcination, the coordinated precursors convert to highly crystalline Mn2O3 nanoparticles, and the random close packing of these nanoparticles leads to the formation of the walls of nanoporous architecture. According to the pore sizes (confirmed by N2 adsorption measurements in the following), the samples are named as MMO-3.2, MMO-4.9, MMO-6.1 and MMO-7.3.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the formation process for mesoporous Mn2O3

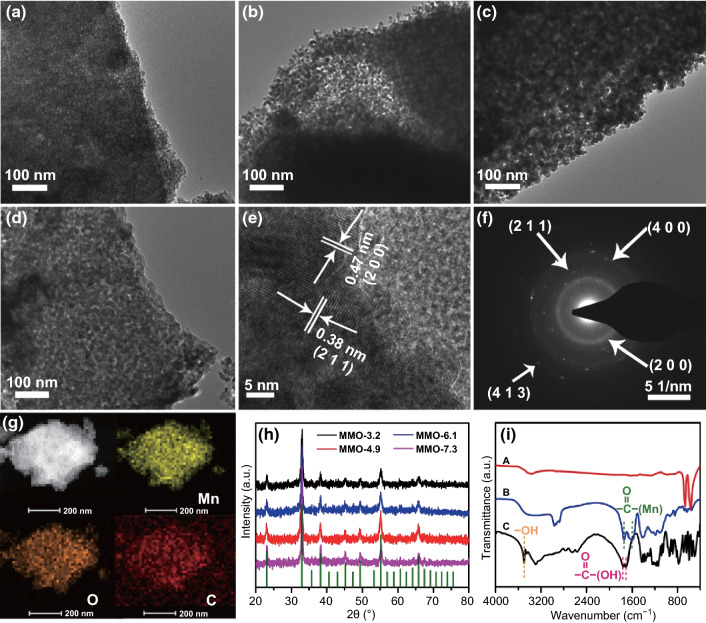

The morphology and structure of various mesoporous Mn2O3 were characterized by field emission transmission electron microscopy (FETEM). It can be clearly observed that the mesopores are evenly dispersed throughout the materials. The pore size can be tuned by simply adjusting the molar ratio of Mn2+ to citric acid ligand. The ratio between metal ion and ligand has a significant influence on the coordination degree between metal ions and ligands, which directly leads to different entanglement densities of the mesoporous framework. The walls of the mesopores are constructed from numerous connected intraparticle voids; in other words, the larger the particle size, the larger the pore size (Fig. S2). As shown in Fig. 2a–d, with the increase in the ratio (n2+Mn/nLigand) from 0.10 to 0.5, the pore sizes can be controlled in a certain range. However, when all ligands coordinate with Mn2+, excessive increase in the ratio (n2+Mn/nLigand) would no further improve the pore size and porosity. Figure 2e shows a high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of the MMO with pore size of 3.2 nm (MMO-3.2), and the interlayer distances of lattice fringes are 0.47 and 0.38 nm, which are assigned to the (200) and (211) plane lattice parameter of cubic Mn2O3 phase. The corresponding selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) shown in Fig. 2f exhibits a series of concentric rings, confirming the polycrystalline character of mesoporous Mn2O3. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) elemental mapping (Fig. 2g) reveals that Mn and O elements are distributed homogeneously among Mn2O3. The presence of C element is attributed to the incomplete combustion of P123 surfactant.

Fig. 2.

Morphological and structural characterizations for mesoporous Mn2O3. TEM images of mesoporous Mn2O3 synthesized at various concentrations of Mn2+: a MMO-3.2, b MMO-4.9, c MMO-6.1, d MMO-7.3. e HRTEM images and f SAED patterns of MMO-3.2. g TEM and elemental mapping of manganese, oxygen and carbon elements of MMO-3.2. h XRD pattern of MMO with different pore sizes. i FTIR spectrum of MMO-3.2 (line A: Mn2O3 obtained at 350 °C, line B: Mn2+ coordinated with citric acid, line C: citric acid ligand)

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was conducted to characterize the crystal structures of the synthesized manganese oxides (Fig. 2h). All characteristic peaks match well with the standard card of Mn2O3 (JCPDS No. 24-0805). The size of aggregated MMO-3.2 nanoparticles calculated by the Scherrer formula is approximately 5 nm, which is consistent with TEM observations. As shown in Fig. S3, the amorphous precursors can transform to highly crystalline Mn2O3 with the increase in the calcination temperatures. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra are shown in Fig. 2i, the peak of C=O in citric acid shifts to low wave number, and the peak of –OH in citric acid almost disappears, confirming that the carboxyl has coordinated with Mn2+ [35]. After calcination at 350 °C, the peak of C=O completely disappears in the spectra, and these results demonstrate that the thermal decomposition boosts the transition from intermediate state of manganese coordination compound to manganese oxide. Raman spectra were performed to further study the vibrational information of the Mn2O3. As shown in Fig. S4, one strong peak appeared at 634 cm−1 is attributed to the characteristic symmetric Mn–O stretching mode of MnO6 octahedrons. Peaks detected at 171 and 200–400 cm−1 are assigned to the out-of-plane bending modes and asymmetric stretching of bridging oxygen species (Mn–O–Mn) of Mn2O3, respectively [36, 37].

To determine the valence state of Mn, the obtained mesoporous material was studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Survey scan (Fig. 3a) reveals the coexisting of Mn, O and C on the material surface. As shown in Fig. 3b, two main signals at 641.6 and 653.4 eV of Mn 2p are ascribed to the Mn 2p3/2 and Mn 2p1/2, respectively, and the spin-energy separation of 11.8 eV is a typical value of Mn3+ in Mn2O3 [38]. Three O 1s peaks, at 529.7, 531.0 and 532.4 eV, can be observed in O XPS spectrum (Fig. 3c), corresponding to Mn–O–Mn, Mn–O–H and O–H–O, respectively. Peaks appearing at 288.3, 286.0 and 284.7 eV are ascribed to the C 1s of Mn2O3 (Fig. 3d), which come from the residual carbon from incomplete combustion of the surfactant. To monitor the degradation behavior of mesoporous Mn2O3, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was employed under air atmosphere (Fig. S5). The slight weight losses before 350 °C are attributed to the H2O absorbed in the mesoporous channels. The degradation of the residual carbon contributes to the weight loss in the range of 350–550 °C, leading to 78% mass retention [39].

Fig. 3.

XPS spectrum of MMO-3.2: a survey spectrum, b manganese peaks Mn 2p3/2 and Mn 2p1/2, c oxygen (O 1s) and d carbon (C 1s). e, f Nitrogen sorption isotherms and corresponding pore-size distribution curves of the samples

The nanoporous architectures were further studied by N2 adsorption–desorption measurements. Figure 3e, f shows the N2 isotherms and corresponding pore-size distributions of mesoporous Mn2O3 prepared with different molar ratios of Mn2+ to citric acid ligand. As shown in Fig. 3e, all of the isotherms exhibit typical type-IV curve with obvious H1-type hysteresis loop. For MMO-3.2, the specific surface area, pore volume and pore size are calculated to be 260 m2 g−1, 0.32 cm3 g−1 and 3.2 nm, respectively. With the increase in ratio (n2+Mn/nLigand), the pore size enlarged gradually from 3.2 to 7.3 nm, while the BET surface area of mesoporous Mn2O3 decreases from 260 to 55 m2 g−1 (Table S1). Apart from molar ratio, the calcination temperatures also have a great influence on the mesoporous architectures. For MMO-3.2, with the increase in calcination temperatures from 350 to 550 °C, the nanoparticles accumulate and aggregate together during the thermal recrystallization (Fig. S6). Consequently, the pore diameter and crystallinity degree increase at the same time, while the specific BET surface areas (from 230 to 42 m2 g−1) and pore volumes (from 0.321 to 0.113 cm3 g−1) decrease gradually (Fig. S7). Further increasing the calcination temperature to 650 °C, the Mn2O3 shows non-porous characteristics because the porous structure completely collapses (Fig. S8). The gradient mesoporous Mn2O3 materials provide sufficient samples to explore their electrochemical properties.

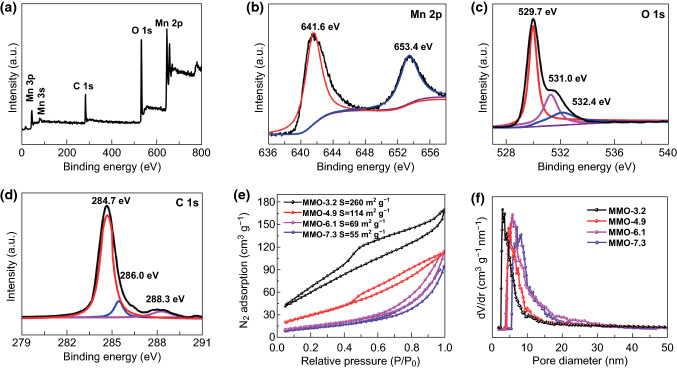

Electrochemical Characterization of Zn/Mn2O3 Battery

The research on ZIBs is currently in its primary stage, and Mn-based materials are considered as one of the most attractive candidates in ZIBs [14, 40]. Though the Mn2O3 as cathode materials possesses the advantages of high theoretical capacity and energy density, the research on Zn/Mn2O3 battery is rare and the reported Mn2O3 electrodes still face the challenge of poor rate capability and low specific capacity [27]. Here, Zn/Mn2O3 battery was assembled by employing highly crystalline mesoporous Mn2O3 as a cathode, Zn foils as the anode, 2 mol L−1 ZnSO4 and 0.2 mol L−1 MnSO4 solutions as the neutral electrolyte. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) test and galvanostatic discharge–charge experiment were operated to investigate the electrochemical performance of the as-synthesized mesoporous Mn2O3 materials. Figure 4a shows the CV curves of Zn/MMO-3.2 cell at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1 between 1.0 and 1.8 V. Two pairs of redox peaks on both cathodic and anodic sweeps can be observed, demonstrating a multistep reaction processes. The galvanostatic charge/discharge profiles of the MMO-3.2 electrode at a current rate of 100 mA g−1 are shown in Fig. 4b. The discharge curve exhibits two apparent plateaus appeared at about 1.25 and 1.38 V, and the charge curve exhibits plateaus at about 1.60 and 1.65 V, which are in accordance with the two pairs of reduction/oxidation peaks in the CV curves. The initial three discharge capacities are 262.5, 301.6 and 288.1 mAh g−1, respectively, much higher than previously reported results [27, 28]. The latter discharge capacities are larger than the first one, which can be ascribed to the discharge capacity improved by the activation process.

Fig. 4.

Electrochemical performances of Zn/Mn2O3 batteries. a Cyclic voltammetry curve of MMO-3.2 at 0.1 mV s−1. b Galvanostatic charge–discharge curve of MMO-3.2. c Rate capability and d cycling performance of Mn2O3 electrodes with different surface areas in hybrid electrolyte (2 M ZnSO4 + 0.2 M MnSO4). e Long-term cycling stability of MMO-3.2 at 3080 mA g−1

The rate performance of the Mn2O3 electrodes with different surface areas was examined by cycling at various current densities. As shown in Fig. 4c, owing to superior structural stability and remarkable electrode reaction kinetics of the mesoporous Mn2O3 materials, all the electrodes exhibited excellent rate performance. Under the same scan rate, the discharge capacities improve greatly with the increase in the surface areas. The optimal sample of MMO-3.2, possessing the smallest pore size and highest surface area, delivered the most excellent rate performance with discharge capacities of 292, 258, 228, 206, 179 and 162 mAh g−1 at various rates of 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5 and 10 C (1 C = 308 mA g−1), respectively. In order to further clarify the role of the nanoporous architecture in battery performance, the cycling performances of the Mn2O3 with different pore sizes were carried out at the current rate of 308 mA g−1 (1 C). As depicted in Fig. 4d, except obvious capacity fading can be observed from the cycling curves of MMO-7.3 in the first few cycles, and other porous samples all show steady cycling performance, demonstrating excellent structural stability and steady electrochemical kinetics. The capacity fading of MMO-7.3 in initial cycles is attributed to the unstable loose pore structure. The loose pores are not as robust as the dense ones. However, after several charging and discharging processes, the loose mesoporous structure is stabilized and the capacity almost keeps constant. It is noteworthy that the MMO-3.2 electrode delivers a much higher capacity of 233 mAh g−1 at the current of 308 mA g−1 and up to 99% capacity retention can be maintained after 120 cycles. The long-term cycling stability at high current density is crucial to evaluate the battery performance. As shown in Figs. 4e and S9, porous Mn2O3 materials exhibit considerable long-term cycling stability. Especially for MMO-3.2, the electrode presents admirable cycling capacity stabilized at 146 mAh g−1 after 3000 cycles at high current density of 3.08 A g−1 with a capacity retention of 89%. Moreover, the Coulombic efficiency always maintains nearly 100% in the whole cycle period, superior to most previous reported manganese oxide materials in terms of both discharge capacity and cycling stability as listed in Table S2 [20, 41, 42].

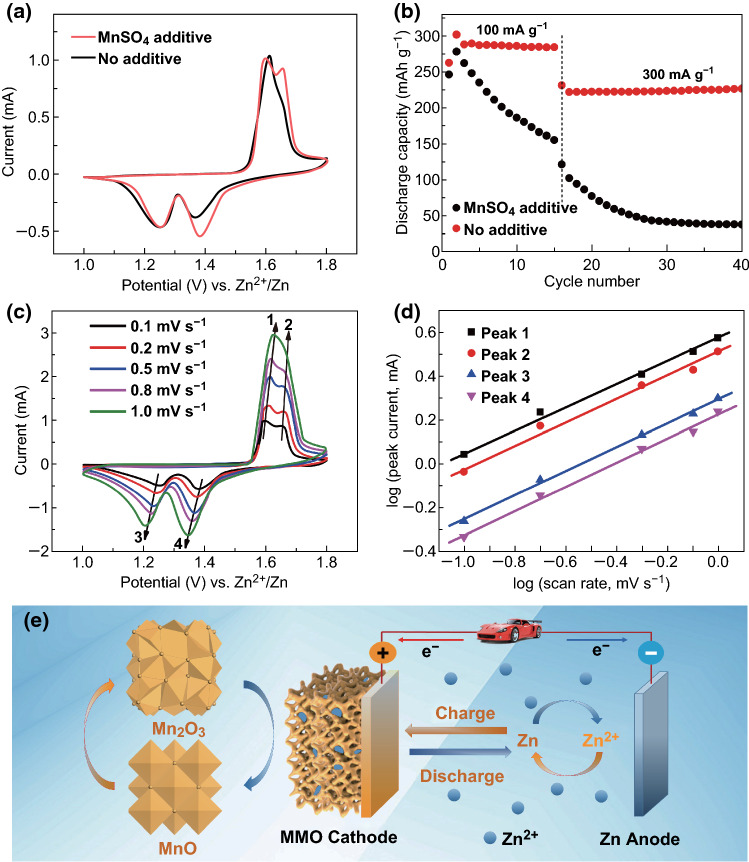

It is worth noting that the pre-addition of MnSO4 plays a crucial role in the enhancement of cycling performance. In the single ZnSO4 electrolyte atmosphere, the continuous Mn2+ dissolution results in a significant capacity loss. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, the pre-addition of 0.2 mol L−1 Mn2+ does not affect the progress of the redox reaction; instead, an appropriate dissolution equilibrium between Mn2+ dissolution and the reoxidation of Mn2+ is achieved, which effectively improves the cycle stability of the battery. Sweep voltammetry curves (Fig. 5c) at different scan rates from 0.1 to 1 mV s−1 were used to study the electrochemical kinetic according to Eqs. 1 and 2:

| 1 |

| 2 |

where a and b stand for adjustable coefficients, and the current (i) and the sweep rate (v) follow a power–law relationship. Generally, the b value [refer to the slope of log (i) vs. log (v) curve] of 0.5 demonstrates a diffusion-controlled process, whereas 1.0 signifies a surface capacitive-controlled process [43]. The b values of the four peaks (Fig. 5d) in CV curves were calculated to be 0.5338, 0.5406, 0.5432 and 0.5615, respectively, which indicates that the electrochemical kinetic of Mn2O3 electrode depends mainly on the diffusion-controlled process.

Fig. 5.

Kinetic behavior of Zn/Mn2O3 cells. a Comparison of CV scanning at 0.1 mV s−1 and b the cycling performance of MMO-3.2 electrodes with and without MnSO4 additive in ZnSO4 aqueous electrolyte at about C/3 and 1C, respectively. c CV curves at different scan rates of 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 1.0 mV s−1. d Logi versus logv plots at specific peak currents. e Illustration of charge/discharge process for Zn/Mn2O3 aqueous rechargeable battery

Apparently, the introduction of nanoporous architectures can considerably enhance the rate performance and cycling stability of Zn/Mn2O3 batteries. Compared with bulk Mn2O3, the superior performances of porous architectures are mainly attributed to the following aspects: First and foremost, the nanoporous architecture can effectively alleviate the volume expansion and contraction during charge/discharge process. Second, as shown in Fig. 1, the interconnected porous structure and large specific surface area facilitate liquid electrolyte diffusion into the nanoparticles and allow Zn2+ to easily transfer from liquid electrolyte to the solid electrode. Moreover, well-connected Mn2O3 nanocrystals provide a continuous electron-conducting path for ZIBs.

Mechanism Study on Zn/Mn2O3 Battery

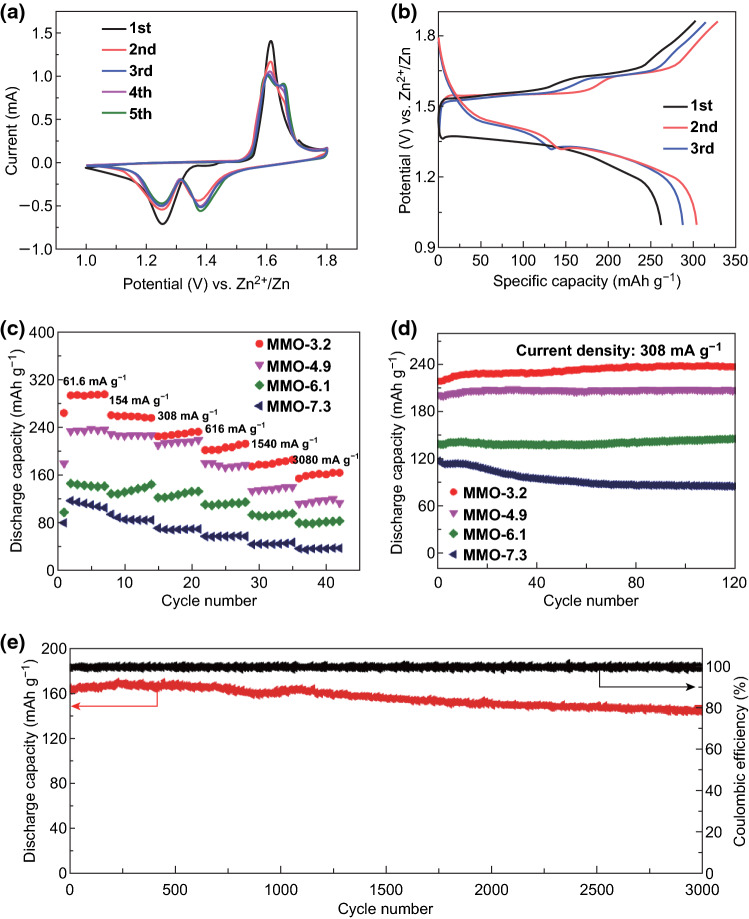

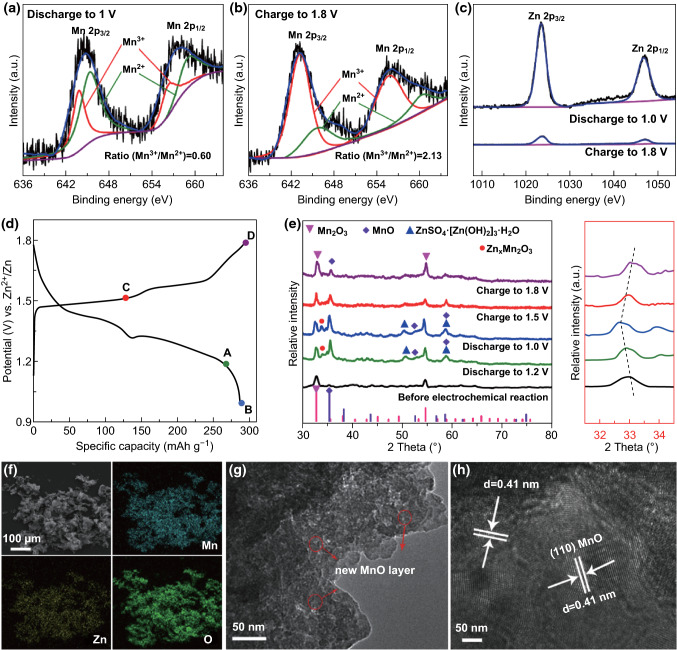

XPS, ex situ XRD and TEM analyses were carried out to reveal the Zn-storage mechanism of Zn/Mn2O3 batteries. Figures 6a–c shows the XPS spectra of Mn2O3 cathode in charge/discharge state, verifying the oxidation state of Mn and Zn elements. For Mn element, the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 peak can be, respectively, divisible into two different peaks corresponding to Mn3+ and Mn2+, and the area ratio of Mn3+/Mn2+ declined from 2.13 to 0.60 in the discharge process; nevertheless, in the following charging process, the value returns to the initial state (Fig. 6a, b). The change of intensity ratio is referred to the reversible redox reaction between Mn3+ and Mn2+. For Zn element, two peaks of Zn 2p at 1023.5 and 1046.7 eV can be observed in Zn XPS spectra at the fully discharged state (1.0 V), suggesting the formation of Zn-containing compound (Fig. 6c). Compared with the discharge state, the relative intensity of Zn 2p peak is much lower at the fully charge state of 1.8 V, demonstrating that the Zn2+ can be reversibly removed from the electrodes [44, 45].

Fig. 6.

Structural evolution and morphology characterization of Zn/Mn2O3 batteries during the electrochemical process. High-resolution XPS spectra of a, b Mn 2p and c Zn 2p at the fully discharge/charge state. d Charge/discharge profiles at 0.2C at the 100th cycle. e Ex situ XRD patterns in different discharge/charge states at the 100th cycle. f SEM–EDS mapping of the elemental distribution of Mn, Zn and O in the MMO-3.2 cathode. g, h Morphology characterization of cathode materials in the fully discharge state

To explore the structural evolution during discharge/charge process, ex situ XRD patterns of different states from A to D (marked in Fig. 6d) at the 100th cycle were conducted. As shown in Figs. 6e and S10, some new reflection peaks belonging to MnO (JCPDS No. 04-0326) appear at 36.1° and 58.5° in the discharge process and the intensities of the peaks gradually weaken in the following charging process, indicating a H+ insertion/extraction process. In this process, Mn2O3 reacts with a proton in H2O to form MnO, and the residual hydroxyl ions connect with ZnSO4 and H2O to form ZnSO4·[Zn(OH)2]3·xH2O for achieving charge balance in the neutral electrolyte atmosphere. The characteristic peak of ZnSO4·[Zn(OH)2]3·xH2O (JCPDS No. 39-0688) observed at 50.8° is in good agreement with the proposed H+ insertion process. In addition, the characteristic diffraction peak of (222) at 32.9° in Mn2O3 gradually shifts to lower diffraction angles during discharge process and returns to its original state during the charge process, demonstrating the expansion/recovery of crystal lattice of Mn2O3 [46–49]. Remarkably, the lattice expansion of Mn2O3 was attributed to the intercalation of Zn2+, who possesses larger atomic radii than Mn3+, and the new reflection appearing at around 34° belonging to ZnxMn2O3 further confirms the Zn2+ intercalation process. The reaction processes proposed above were verified by SEM mapping and TEM characterizations (Figs. S11 and 6f–h). In the fully discharge state, the EDX elemental mapping images reveal a uniform distribution of Mn, Zn and O element, which manifests the intercalation of Zn2+ into Mn2O3. Meanwhile, a newly formed thin layer with uniform lattice spacing of 0.41 nm can be clearly observed in the HRTEM image, which is attributed to the (110) lattice planes in MnO, confirming the reversible redox reaction between Mn2O3 and MnO. Overall, the Zn2+ and H+ intercalations mechanism (Fig. 5e) in the two electrodes is expressed as follows:

Cathode:

Anode:

Overall:

Conclusions

In summary, we propose an efficient approach to rationally design the nanoporous architecture of Mn2O3 by facilely altering molar ratio of Mn2+ to citric acid ligand via a ligand-assisted self-assembly process. Effectively modulating the molar ratio between Mn2+ and citric acid ligand can obtain mesoporous Mn2O3 with controllable grain sizes, high BET surface areas (from 55 to 260 m2 g−1) and tunable pore-size distributions (from 3.2 to 7.3 nm). The above-mentioned unique features make the mesoporous Mn2O3 materials outstanding candidates in rechargeable aqueous Zn-ion battery, exhibiting high capacity, together with superior rate capacity and remarkable cycle stability. Furthermore, the Zn-storage process is further studied and Zn2+/H+ intercalations mechanism is put forward by combining electrochemical measurements and multiple analytical methods. The key finding summarized in this work is that the rational design of the nanoporous architecture can effectively boost the battery performance, offering a new avenue for the development of advanced electrode materials.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Young Thousand Talented Program and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21671073 and 21621001), the “111” Project of the Ministry of Education of China (B17020) and Program for JLU Science and Technology Innovative Research Team.

Contributor Information

Bingkun Guo, Email: guobingkun@shu.edu.cn.

Zhen-An Qiao, Email: qiaozhenan@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Chen H, Ling M, Hencz L, Ling HY, Li G, Lin Z, Liu G, Zhang S. Exploring chemical, mechanical, and electrical functionalities of binders for advanced energy-storage devices. Chem. Rev. 2018;118(18):8936–8982. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cano ZP, Banham D, Ye S, Hintennach A, Lu J, Fowler M, Chen Z. Batteries and fuel cells for emerging electric vehicle markets. Nat. Energy. 2018;3(4):279–289. doi: 10.1038/s41560-018-0108-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mei J, Liao T, Kou L, Sun Z. Two-dimensional metal oxide nanomaterials for next-generation rechargeable batteries. Adv. Mater. 2017;29(48):1700176. doi: 10.1002/adma.201700176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang ZW, Xu JJ, Zhang XB. Recent progress in electrocatalyst for Li-O2 batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017;7(23):1700875. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201700875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter M, Barnett B, Xu K. Before Li ion batteries. Chem. Rev. 2018;118(23):11433–11456. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Susai FA, Sclar H, Shilina Y, Penki TR, Raman R, et al. Horizons for Li-ion batteries relevant to electro-mobility: high-specific-energy cathodes and chemically active separators. Adv. Mater. 2018;30(41):1801348. doi: 10.1002/adma.201801348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarascon J-M, Armand M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature. 2001;414(6861):359–367. doi: 10.1038/35104644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhan C, Wu T, Lu J, Amine K. Dissolution, migration, and deposition of transition metal ions in Li-ion batteries exemplified by Mn-based cathodes: a critical review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018;11(2):243–257. doi: 10.1039/C7EE03122J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou W, Wang S, Li Y, Xin S, Manthiram A, Goodenough JB. Plating a dendrite-free lithium anode with a polymer/ceramic/polymer sandwich electrolyte. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138(30):9385–9388. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen L, Yu L, Yu XY, Zhang X, Lou XW. Self-templated formation of uniform NiCo2O4 hollow spheres with complex interior structures for lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54(6):1868–1872. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nayak PK, Yang L, Brehm W, Adelhelm P. From lithium-ion to sodium-ion batteries: advantages, challenges, and surprises. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57(1):102–120. doi: 10.1002/ange.201703772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, Dong S, Cui Z, Du A, Li G, Cui G. Rechargeable magnesium batteries using conversion-type cathodes: a perspective and minireview. Small Methods. 2018;2(10):1800020. doi: 10.1002/smtd.201800020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu X, Wang B, Gong D, Xu Z, Lu B. Graphene nanoribbons on highly porous 3D graphene for high-capacity and ultrastable Al-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2017;29(4):1604118. doi: 10.1002/adma.201604118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song M, Tan H, Chao D, Fan HJ. Recent advances in Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018;28(41):1802564. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201802564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, McRae L, Firby CJ, Elezzabi AY. Rechargeable aqueous electrochromic batteries utilizing Ti-substituted tungsten molybdenum oxide based Zn2+ ion intercalation cathodes. Adv. Mater. 2019;31(15):1807065. doi: 10.1002/adma.201807065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu W, Wang Y. Recent progress on zinc-ion rechargeable batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 2019;11:90. doi: 10.1007/s40820-019-0322-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi YR, Lu YX, Ding FX, Zhang QQ, Li H, Huang J, Chen LQ, Hu YS. Slope-dominated carbon anode with high specific capacity and superior rate capability for high safety Na-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58(13):4361–4365. doi: 10.1002/anie.201900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang Q, Chen F, Wang S, Ru Q, He Q, Hou X, Su CY, Shi Y. An organic flow desalination battery. Energy Storage Mater. 2019;20:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ensm.2018.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan H, Shao Y, Yan P, Cheng Y, Han KS, et al. Reversible aqueous zinc/manganese oxide energy storage from conversion reactions. Nat. Energy. 2016;1:16039. doi: 10.1038/nenergy.2016.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang N, Cheng F, Liu Y, Zhao Q, Lei K, Chen C, Liu X, Chen J. Cation-deficient spinel ZnMn2O4 cathode in Zn(CF3SO3)2 electrolyte for rechargeable aqueous Zn-ion battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138(39):12894–12901. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang N, Cheng F, Liu J, Wang L, Long X, Liu X, Li F, Chen J. Rechargeable aqueous zinc-manganese dioxide batteries with high energy and power densities. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:405. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00467-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo T, Wang S, Hou X, Chen F, Liu X, Shao Z, Yan H. Cr–Zn redox battery with NiFe2O4 as catalyst for enhanced degradation of Cr(VI) pollution. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019;7(1):111–116. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trócoli R, Kasiri G, La Mantia F. Phase transformation of copper hexacyanoferrate (KCuFe(CN)6) during zinc insertion: effect of co-ion intercalation. J. Power Sources. 2018;400:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li G, Yang Z, Jiang Y, Jin C, Huang W, Ding X, Huang Y. Towards polyvalent ion batteries: a zinc-ion battery based on NASICON structured Na3V2(PO4)3. Nano Energy. 2016;25:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.04.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shan L, Zhou J, Han M, Fang G, Cao X, Wu X, Liang S. Reversible Zn-driven reduction displacement reaction in aqueous zinc-ion battery. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019;7(13):7355–7359. doi: 10.1039/C9TA00125E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou X, Liang Q, Hu X, Zhou Y, Ru Q, Chen F, Hu S. Coupling desalination and energy storage with redox flow electrodes. Nanoscale. 2018;10(26):12308–12314. doi: 10.1039/C8NR02737D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang B, Xu C, Wu C, Dong L, Li J, Kang F. Manganese sesquioxide as cathode material for multivalent zinc ion battery with high capacity and long cycle life. Electrochim. Acta. 2017;229:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2017.01.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Zhou X, Liu R, Li X, Bai Y, Xiao H, Wang Y, Yuan G. Tailoring three-dimensional composite architecture for advanced zinc-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(21):19191–19199. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b04583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng F, Wang H, Zhu Z, Wang Y, Zhang T, Tao Z, Chen J. Porous LiMn2O4 nanorods with durable high-rate capability for rechargeable Li-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011;4(9):3668–3675. doi: 10.1039/C1EE01795K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang D, Choi D, Yang Z, Viswanathan VV, Nie Z, et al. Synthesis and Li-ion insertion properties of highly crystalline mesoporous rutile TiO2. Chem. Mater. 2008;20(10):3435–3442. doi: 10.1021/cm8002589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Wu G, Liu X, Li W, Li M. Orderly integration of porous TiO2(B) nanosheets into bunchy hierarchical structure for high-rate and ultralong-lifespan lithium-ion batteries. Nano Energy. 2017;31:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poyraz AS, Kuo CH, Biswas S, King’ondu CK, Suib SL. A general approach to crystalline and monomodal pore size mesoporous materials. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2952. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng D, Gao T-N, Fan M, Li A, Li K, Wang T, Huo Q, Qiao Z-A. A general ligand-assisted self-assembly approach to crystalline mesoporous metal oxides. NPG Asia Mater. 2018;10:800–809. doi: 10.1038/s41427-018-0072-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L, Dai H, Xia Y, Jiang H, Zhang H, He H. Ultrasound-assisted nanocasting fabrication of ordered mesoporous MnO2 and Co3O4 with high surface areas and polycrystalline walls. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114(6):2694–2700. doi: 10.1021/jp910159b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou X, Zhu Y, Luo W, Ren Y, Xu P, et al. Chelation-assisted soft-template synthesis of ordered mesoporous zinc oxides for low concentration gas sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4(39):15064–15071. doi: 10.1039/c6ta05687c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kar P, Sardar S, Ghosh S, Parida MR, Liu B, Mohammed OF, Lemmens P, Pal SK. Nano surface engineering of Mn2O3 for potential light-harvesting application. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2015;3(31):8200–8211. doi: 10.1039/C5TC01475A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolathodi MS, Hanumantha Rao SN, Natarajan TS, Singh G. Beaded manganese oxide (Mn2O3) nanofibers: preparation and application for capacitive energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4(20):7883–7891. doi: 10.1039/C6TA01948J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji D, Zhou H, Zhang J, Dan Y, Yang H, Yuan A. Facile synthesis of a metal–organic framework-derived Mn2O3 nanowire coated three-dimensional graphene network for high-performance freestanding supercapacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4(21):8283–8290. doi: 10.1039/c6ta01377e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Möller K, Kobler J, Bein T. Colloidal suspensions of nanometer-sized mesoporous silica. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007;17(4):605–612. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200600578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han SD, Kim S, Li D, Petkov V, Yoo HD, et al. Mechanism of Zn insertion into nanostructured δ-MnO2: a nonaqueous rechargeable Zn metal battery. Chem. Mater. 2017;29(11):4874–4884. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Islam S, Alfaruqi MH, Mathew V, Song J, Kim S, et al. Facile synthesis and the exploration of the zinc storage mechanism of β-MnO2 nanorods with exposed (101) planes as a novel cathode material for high performance eco-friendly zinc-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017;5(44):23299–23309. doi: 10.1039/c7ta07170a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun W, Wang F, Hou S, Yang C, Fan X, et al. Zn/MnO2 battery chemistry with H+ and Zn2+ coinsertion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139(29):9775–9778. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang B, Fang G, Zhou J, Wang L, Lei Y, et al. Potassium vanadates with stable structure and fast ion diffusion channel as cathode for rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Nano Energy. 2018;51:579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma L, Chen S, Li H, Ruan Z, Tang Z, et al. Initiating a mild aqueous electrolyte Co3O4/Zn battery with 2.2 V-high voltage and 5000-cycle lifespan by a Co(III) rich-electrode. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018;11(9):2521–2530. doi: 10.1039/C8EE01415A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo Z, Ma Y, Dong X, Huang J, Wang Y, Xia Y. An environmentally friendly and flexible aqueous zinc battery using an organic cathode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57(36):11737–11741. doi: 10.1002/anie.201807121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pan C, Nuzzo RG, Gewirth AA. ZnAlxCo2−xO4 spinels as cathode materials for non-aqueous Zn batteries with an open circuit voltage of ≤ 2 V. Chem. Mater. 2017;29(21):9351–9359. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b03340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambandam B, Soundharrajan V, Kim S, Alfaruqi MH, Jo J, et al. Aqueous rechargeable Zn-ion batteries: an imperishable and high-energy Zn2V2O7 nanowire cathode through intercalation regulation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2018;6(9):3850–3856. doi: 10.1039/c7ta11237h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li W, Wang K, Cheng S, Jiang K. A long-life aqueous Zn-ion battery based on Na3V2(PO4)2F3 cathode. Energy Storage Mater. 2018;15:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ensm.2018.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ming F, Liang H, Lei Y, Kandambeth S, Eddaoudi M, Alshareef HN. Layered MgxV2O5·nH2O as cathode material for high-performance aqueous zinc ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2018;3(10):2602–2609. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.