Abstract

A subset of patients with initially unresected (Clinical Group III) rhabdomyosarcoma achieve less than a complete response (CR) despite multi-modal therapy. We assessed outcome based upon tumor response at the completion of all planned therapy. We studied 601 Clinical Group III participants who completed all protocol therapy without developing progressive disease on two Children’s Oncology Group studies ARST0531 (n=285) and D9803 (n=316). Response was defined by imaging and categorized by response; complete resolution (CR), partial response (PR), or no response (NR). Failure free survival (FFS) and overall survival (OS) between response groups were compared using the log-rank test. We found that radiographic response was CR in 393 (65.4%) and PR/NR in 208 (34.6%) patients. Achieving CR status was associated with study D9803, non-parameningeal (PM) primary sites, tumors ≤5 cm, non-invasive tumors, and alveolar histology/FOXO fusion positive tumors. The overall 5-year FFS was 75% for those achieving CR and 66.5% in those with PR/NR (adj. p=0.094). Patients with PM primary site who achieved CR had significant improved FFS (adj. p=0.037) while those with non-PM primary sites had similar outcomes (adj. p=0.47). Radiographic response was not associated with OS (adj. p=0.21). Resection of the end-of-therapy mass did not improve FFS (p=0.12) or OS (p=0.37). In conclusion, CR status at the end of protocol therapy in patients with PM Clinical Group III RMS was associated with improved FFS but not OS. Efforts to understand the biology and treatment response in patients with PM primary site are under investigation.

Keywords: rhabdomyosarcoma, paramengineal, residual mass

Introduction

Approximately 60% of patients registered onto Children’s Oncology Group (COG) rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) treatment studies are currently categorized as ‘intermediate risk’. 1 These patients usually have disease that is not amenable to upfront complete surgical resection of the primary tumor without excessive morbidity and therefore have gross residual disease (clinical group III) at the initiation of chemotherapy. Approximately 45% of intermediate risk patients have primary parameningeal (PM-RMS) disease.2 Multiple cooperative groups have analyzed the impact of early RMS primary tumor response to induction therapy on outcome and found variable results.3–6 Historically, European RMS clinical trials have used radiographic response to induction therapy to adjust subsequent therapy in an attempt to minimize toxicity yet maximize survival.7, 8 This treatment philosophy assumes that initial response to therapy is associated with ultimate outcome and can identify chemotherapy-sensitive tumors more likely to be cured with systemic therapy. However recent results from MMT-95 found that there was no correlation between early radiographic response and outcome.9 Two COG studies also did not demonstrate any correlation between early response and outcomes.3, 5

Local control for the majority of patients with Group III RMS is achieved by definitive radiotherapy (RT) since PM-RMS tumors are usually not amenable to resection, and residual tumor masses often remain following induction chemotherapy. The persistence of residual masses at the end of therapy are often a source of concern for both providers and families. In a prior analysis of IRS-IV, there was no statistical difference in 5-year failure-free survival (FFS) or overall survival (OS) between those who had complete response (CR, FFS 80%) versus partial/no response (PR/NR, FFS 78%) (p=0.4) for the primary tumor at the completion of all planned therapy.4 This observation held true for patients with PM and non-PM disease. In that analysis, surgical procedures to remove end-of-therapy masses often failed to achieve complete resection, were associated with significant morbidity, and provided no improvement in outcome.

While the presence of residual end-of-therapy mass has not been associated with inferior outcomes, it has been shown that residual viable tumor at earlier time points during therapy has clinical significance. Raney et al. demonstrated that 16% (n=79) of patients on IRS-IV underwent some form of surgical procedure (i.e. biopsy or resection) at a median of 24 weeks (range, 4–55 weeks) from start of therapy, of whom 37 (46%) had viable disease.10 FFS was significantly better for patients with no viable tumor at these earlier time points after induction chemotherapy.

We therefore sought to analyze contemporary data pooled from the two most recently completed COG studies in patients with intermediate risk RMS (D980311 and ARST053112) to determine the effect of end-of-therapy treatment response (CR vs. NR/PR) on FFS and OS. Secondary aims of the study were to determine predictors of end-of-therapy response and to correlate end-of-therapy imaging response with histologic findings of viable tumor.

Methods

Patient Population and Therapeutic Protocols

We studied 601 Clinical Group III (biopsy only or gross residual disease after resection without distant metastases) patients from COG studies D9803 (NCT00003958; 1999–2005) and ARST0531 (NCT00354835; 2006–2012) who did not develop progressive disease while on protocol therapy. The trials were approved by the Pediatric Central Review Board or by the institutional review boards of each participating institution, as required. Informed consent was obtained from patients’ parents or guardians, the patients, or both, according to guidelines of the NCI. Median follow-up for the patients who remained alive was 5.70 years (range 0.87 – 13.95 years) from study enrollment. Patient characteristics between the two studies are compared in Supplemental Table 1. Clinical group was assigned prior to the initiation of chemotherapy. Clinical Group III participants all had measurable primary tumors at study entry and therefore were evaluable for radiographic response.

Details of the chemotherapy treatment have been previously published.11, 12 Briefly, for D9803, patients were randomized to standard VAC (vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide) chemotherapy or VAC alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide (VAC/VTC); for ARST0531 vincristine and irinotecan (VI) alternating with VAC. All treatment arms were combined for our analysis because there were no significant differences in outcomes by treatment arm within each study.

Local control regimens were different between D9803 and ARST0531. For D9803 clinical group III patients, local RT began after week 12 except for patients with PM-RMS with intracranial extension, who received RT immediately.13 A dose of 50.4 Gy was used for definitive treatment of clinical group III tumors. By protocol design, patients with clinical group III tumors of the bladder dome, extremity, or trunk (including thorax, abdomen, and pelvis) were candidates for delayed primary excision (DPE) at week 12 if the primary tumor appeared resectable. Those who had complete resection with negative margins then received 36 Gy, whereas those with microscopic residual or biopsy confirmation of complete response received 41.4 Gy. Patients with gross residual disease after delayed surgery received 50.4 Gy postoperatively. This treatment paradigm utilizing DPE with reduced RT doses did not impact outcomes.14 In contrast, on ARST0531 for patients >24 months of age, definitive RT was the planned local control modality. Delayed primary resection before or after RT was allowed but not encouraged. For patients ≤ 24 months, individualized local control approaches for surgical resection and RT, were permitted. However, adherence to the RT algorithm whenever possible for patients < 24 months was encouraged. RT started at week 4 and the dose was determined by Clinical Group and histology at study entry: Clinical Group III alveolar RMS (ARMS) with orbital primary site, 45 Gy; Clinical Group III embryonal RMS (ERMS) or ARMS at non-orbital primary sites, 50.4 Gy.

Some patients had a surgical procedure during the last treatment period (week 30–42). The surgical and pathology records for these “end-of-therapy” procedures were reviewed to determine surgical intent, procedure performed, loss of vital structures, loss of function, margin status, and pathology results including viable tumor.

Definition of Endpoints

In both D9803 and ARST0531, response was categorized by the response achieved by the end of therapy and was determined by radiographic measurement of tumor at the local institutions, without central review (Table 1). FFS reflects the percentage of participants who remained alive in the study without relapse, progressive disease, or a fatal event from any cause. Local failure was defined as progression or relapse at the primary tumor site as a first event, including those with concurrent local plus regional or distant failure. OS was defined as the time from the start of treatment to death from any cause. FFS and OS for participants who had not experienced the event of interest were censored at the patient’s last contact date.

Table 1:

Definitions of radiographic response by study

| Complete Response | Partial Response | Stable Disease/No Response | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D9803 (2D measurements) | Disappearance of all tumor(s) with no evidence of disease. | ≥50% decrease in the sum of the products of the maximum perpendicular diameters | <50% decrease in the sum of the products of the maximum perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions; no evidence of progression in any lesion, and no new lesions, |

| ARST0531 (3D measurements) | Complete disappearance of the tumor | At least 64% decrease in volume compared to the baseline | Less than 64% decrease and no more than 39% increase in volume, |

Statistical Analysis Methods

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the FFS and OS distributions and estimates with confidence interval calculated using the Peto-Peto method.15 Differences between survival curves were analyzed by the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to adjust comparisons of the FFS and OS between patient groups with backward model selection for possible confounding factors including study (ARST0531 or D9803), primary site and categorization (favorable or unfavorable; PM or non-PM), age, stage, tumor size (≤ 5cm or > 5cm), t-stage, N-stage, histology, and FOX01 fusion status. The distributions of categorical participant characteristics were compared between the groups using a Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Analyses were based on data available by July 1, 2016. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The site of first recurrence was defined as local if the tumor recurred at the site of primary disease +/− regional or distant; as regional if regional lymph nodes were involved +/− distal recurrence; and as distant if any metastatic disease was present at recurrence in the absence of local or regional disease. The cumulative incidence of local failures at 5 years was estimated using a competing risk analysis.16

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available upon reasonable request and publicly within one year after publication. Requests for access to the data can be made on a National Cancer Institute website: https://nctn-data-archive.nci.nih.gov/

Results

Patient Demographics and Disease Characteristics

A total of 601 participants were eligible for evaluation, including 393 (65.4%) participants who achieved a CR and 208 participants (34.6%) who achieved a PR/NR at end of therapy. 285 (47.4%) participants were derived from ARST0531 and 316 (52.6%) from D9803. The distribution of clinical characteristics by radiographic response are shown in Table 2. Factors predictive of achieving CR included participation in D9803 (p<0.001), non-PM tumor site (p=0.006), tumor ≤5 cm (p=0.006), T1 stage (p=0.027), alveolar histology (p<0.001) and FOXO1 fusion positive status (p=0.003). Patient age (p=0.52), nodal status (p=0.064), primary site (favorable or unfavorable, p=0.14) and stage (p=0.44) were not significantly associated with a CR status.

Table 2:

Patient clinical characteristics based on response status

| Feature | Group | CR (n=393) | PR/NR (n=208) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | ARST0531 | 162 (56.8%) | 123 (43.2%) | <0.001 |

| D9803 | 231 (73.1%) | 85 (26.9%) | ||

| Primary Site | Favorable | 29 (76.3%) | 9 (23.7%) | 0.14 |

| Unfavorable | 364 (64.7%) | 199 (35.3%) | ||

| Specific Site | Head and neck | 18 (78.3%) | 5 (21.7%) | <0.001 |

| Orbit | 11 (73.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | ||

| Extremity | 64 (87.7%) | 9 (12.3%) | ||

| Trunk | 15 (75.0%) | 5 (25.0%) | ||

| GU B/P | 63 (61.8%) | 39 (38.2%) | ||

| Parameningeal | 177 (60.0%) | 118 (40.0%) | ||

| Retro/Peritoneal | 43 (64.2%) | 24 (35.8%) | ||

| Other | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | ||

| Parameningeal | PM | 177 (60.0%) | 118 (40.0%) | 0.006 |

| Non-PM | 216 (70.6%) | 90 (29.4%) | ||

| Age (years) | 1–9 | 260 (64.5%) | 143 (35.5%) | 0.52 |

| <1 or 10+ | 133 (67.2%) | 65 (32.8%) | ||

| Stage | 1 | 21 (70.0%) | 9 (30.0%) | 0.44 |

| 2 | 128 (68.4%) | 59 (31.6%) | ||

| 3 | 244 (63.5%) | 140 (36.5%) | ||

| Tumor Size | ≤5 cm | 187 (71.4%) | 75 (28.6%) | 0.006 |

| >5 cm | 200 (60.6%) | 130 (39.4%) | ||

| T-stage | T1 | 178 (70.4%) | 75 (29.6%) | 0.027 |

| T2 | 214 (61.7%) | 133 (38.3%) | ||

| N-stage | N0 | 308 (63.9%) | 174 (36.1%) | 0.064 |

| N1 | 84 (73.0%) | 31 (27.0%) | ||

| Histology | ARMS | 168 (74.7%) | 57 (25.3%) | <0.001 |

| ERMS | 225 (59.8%) | 151 (40.2%) | ||

| FOXO1 fusion status | Positive | 103 (75.2%) | 34 (24.8%) | 0.003 |

| Negative | 261 (61.1%) | 166 (38.9%) |

FFS Based on Best Therapeutic Response

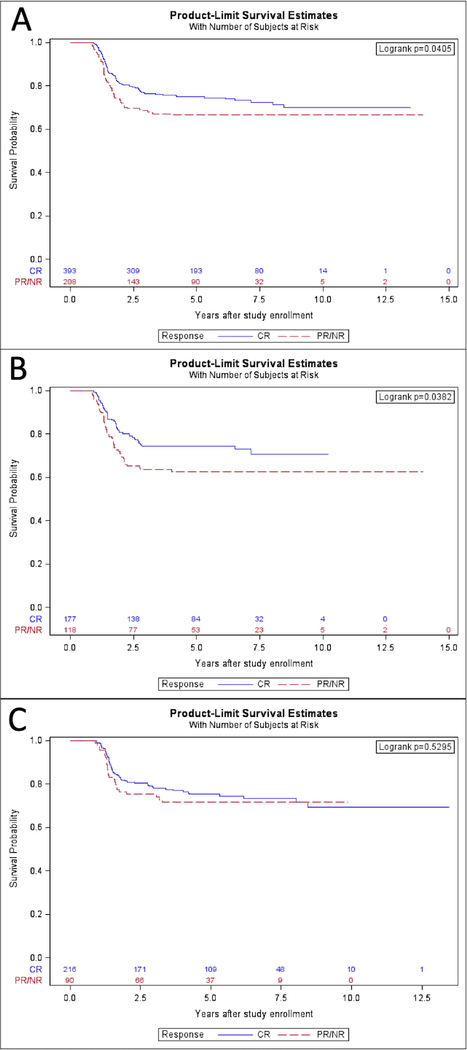

For the whole cohort, participants who achieved a radiographic response of CR had improved 5-year FFS compared to those who achieved a PR/NR (CR 5-year FFS 75.0% (95% CI 69.7%−80.3%) vs PR/NR 66.5% (95% CI 58.6%−74.5%), p=0.041) (Figure 1A). However, this difference in FFS was largely attributable to PM tumors (n=295), in whom 5-year FFS was 74.5% (95% CI 66.5%−82.6%) with CR and 62.7% (95% CI 52.4%−73.0%) with PR/NR (p=0.038) (Figure 1B). For non-PM participants (n=306), FFS was similar between response groups (CR 5-year FFS 75.3% (95% CI 68.3%−82.3%) vs PR/NR 71.6% (95% CI 59.3%−83.9%), p=0.53) (Figure 1C). To account for differences in clinical prognostic factors between the CR and PR/NR groups, including study (ARST0531 or D9803), primary site and categorization (favorable or unfavorable; PM or non-PM), age, stage, tumor size (≤ 5cm or > 5cm), t-stage, N-stage, histology, and FOX01 fusion status, we performed a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with backward selection. In the adjusted analysis, the significant difference in the risk of treatment failure for patients with PM disease persisted (p=0.037) but the finding in the overall cohort was no longer significant (p=0.094). Again, those with non-PM tumors had no difference in risk of treatment failure between response groups (Table 3).

Figure 1.

A. FFS of participants who achieved a best response of CR compared to PR/NR. B. FFS of participants with paramengineal tumors who achieved CR compared to PR/NR. C. FFS of participants with non-paramengineal tumors who achieved CR compared to PR/NR.

Table 3:

Risk of treatment failure defined by relapse, disease progression or death utilizing Cox proportional hazards regression modelling to adjust for potential confounding variables

| Patients and regression model | Hazard ratio (CR:PR/NR) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| All participants, N=601 | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.728 | (0.537, 0.988) | 0.041 |

| Adjusted | 0.756 | (0.545, 1.049) | 0.094 |

| PM sites only, N=295 | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.650 | (0.430, 0.980) | 0.040 |

| Adjusted | 0.630 | (0.407, 0.973) | 0.037 |

| Non-PM sites only, N=306 | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.860 | (0.536, 1.378) | 0.53 |

| Adjusted | 0.831 | (0.505, 1.369) | 0.47 |

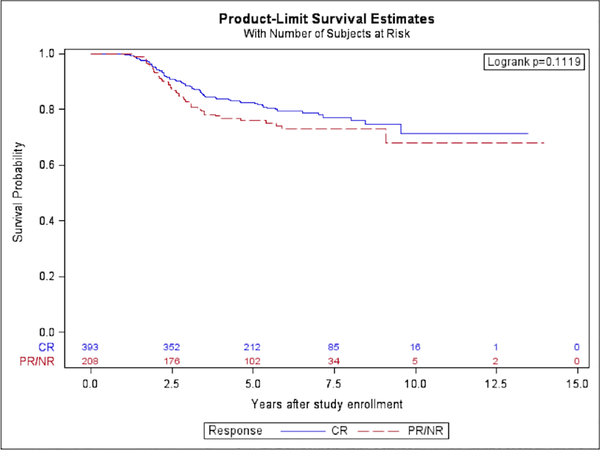

OS Based on Best Therapeutic Response

Five-year overall survival for all patients was similar with 82.5% (95% CI 77.9%−87.2%) in the CR group and 76.0% (95% CI 68.8%−83.2%) in the PR/NR group (p=0.11) (Figure 2). As expected, OS was higher than FFS due to the potential for curative second-line therapy. When analysis was limited to patients with PM tumors, there was also no difference in OS between the CR (82.5%, 95% CI 75.5%−89.5%) compared to PR/NR (72.3%, 95% CI 62.8%−81.9%, p=0.13). Cox regression analysis with backward selection adjusted for differences in prognostic characteristics between CR and PR/NR participants, including study (ARST0531 or D9803), primary site and categorization (favorable or unfavorable; PM or non-PM), age, stage, tumor size (≤ 5cm or > 5cm), t-stage, N-stage, histology, and FOX01 fusion status, demonstrated a similar OS (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Overall survival of participants who achieved a best response of CR compared to PR/NR.

Table 4:

Risk of death utilizing Cox proportional hazards regression modelling to adjust for potential confounding variables

| Patients and regression model | Hazard ratio (CR:PR/NR) | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| All participants, N=601 | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.753 | (0.531, 1.069) | 0.11 |

| Adjusted | 0.785 | (0.540, 1.142) | 0.21 |

| PM sites only, N=295 | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.696 | (0.437, 1.109) | 0.13 |

| Adjusted | 0.657 | (0.403, 1.073) | 0.093 |

| Non-PM sites only, N=306 | |||

| Unadjusted | 0.879 | (0.505, 1.530) | 0.65 |

| Adjusted | 0.921 | (0.507, 1.673) | 0.79 |

Pattern of First Recurrence

Disease failure occurred in 99/393 (25.2%) CR patients and 68/208 (32.7%) PR/NR patients (p=0.051). The 5-year local failure rate was higher in the PR/NR group (CR 14.1%, (95% CI 10.9% −18.3%) vs PR/NR 23.5%, (95% CI 18.0% −30.6%), p=0.004). Among those patients with disease progression, initial failure was purely local in 39.4% of CR patients and 57.4% of PR/NR patients. The site of first failure is shown in Table 5. Median time to failure was 1.47 years from study entry.

Table 5:

Distribution of site of failure in patients with disease progression stratified by tumor site

| Site | CR | PR/NR | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Patient Locala vs Regional/Distant | 0.039 | ||

| Local | 54 | 49 | |

| Regional or distant | 42 | 19 | |

| PM Local vs Regional/Distant | 0.045 | ||

| Local | 27 | 35 | |

| Regional or distant | 18 | 9 | |

| Non-PM Local vs Regional/Distant | 0.66 | ||

| Local | 27 | 14 | |

| Regional or distant | 24 | 10 |

local includes local +/− regional or distant

3 patients with unknown pattern of relapse; all three were included in the calculation of local failure rate for a conservative estimate

Procedures Performed at the Completion of Therapy

Twenty-six patients underwent end-of-therapy procedure, including 23 in D9803 and 3 in ARST0531. There were no statistical differences in 5-year FFS (88.5%, 95% CI 75.3%−100.0%, with procedure vs 71.3%, 95% CI 66.7%−76.0%, for no procedure, p=0.12) or OS (88.5%, 95% CI 75.3%−100.0%, with procedure vs 79.9%, 95% CI 75.8%−84.0%, for no procedure, p=0.37). End-of-therapy procedures were predominantly performed on patients with bladder/prostate tumors (15/26, 57.7%) and PM tumors (7/26, 26.9%). 22 patients underwent biopsy, while only 4 patients underwent resection. Viable RMS was reported by institutional pathology assessment in 5 of 23 cases (2 at resection and 3 at biopsy); central pathology review of resected specimens was not performed. Morbidity of surgical procedures included resection of the vas deferens in one case and orbital exenteration in one case.

Discussion

This is the largest analysis of radiographic response status at the end of therapy among patients with group III RMS. We have shown that the presence of a residual mass in patients with PM RMS at the end of therapy had a significant impact on FFS, although not on OS. In contrast, no difference in FFS was seen among patients with non-PM primary sites.

These results further refine our prior observations from IRS-IV regarding the prognostic value of end of therapy radiographic response in patients with Group III RMS.4 First, the majority of patients treated for Group III RMS experience a complete response by the end of therapy. Second, 34.6% of patients have a residual mass at completion of therapy, and for non-PM primary sites, this is not predictive of FFS or OS. Third, for PM tumors, residual mass is associated with inferior FFS but not inferior OS. Fourth, a number of clinical factors, including participation in D9803, favorable tumor site, smaller tumors (≤5 cm), stage (T1), and alveolar histology and/or fusion-positive status are associated with improved treatment response. Fifth, the number of end-of-therapy mass resections - which is known to be associated with a high rate of surgical morbidity - decreased from IRS-IV (17 patients) and D9803 (23 patients) to ARST0531 (3 patients) suggesting that our published findings from IRS-IV impacted subsequent surgical care for patients with end of therapy mass.

The rate of complete response was lower in ARST0531 (56.8%) compared to D9803 (73.1%) and IRS-IV (81.4%). There was also a concurrent increase in local failure rates in ARST0531.2 In all COG studies of RMS, the determination of response to therapy, based on radiographic findings, is performed at local institutions. Over the past two decades, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging has supplanted computed tomography (CT) as the predominant imaging modality for RMS, and resolution has improved dramatically for all imaging techniques. It is therefore possible that more contemporary patients are classified as PR rather than CR based on subtle post-treatment MR imaging findings that would not have been seen with previous CT imaging techniques. Concurrently, the utilization of biopsy or resection for end-of-therapy masses decreased from IRS-IV to D9803 and was minimal in ARST0531. Although not affecting clinical outcomes, in older studies these biopsies may have led to reclassification from PR to CR when histological examination noted no evidence of viable tumor. It is also possible that the underlying chemotherapy regimen in ARST0531, including the reduced dose of cyclophosphamide, partially explains the lower rate of CR. However, because our Cox regression analysis adjusted for study participation (ARST0531 vs D9803), the main findings hold despite these differences in rates of radiographic response and local failure.

Over one-third of patients had a residual mass at end-of-therapy. These residual masses may represent (1) reactive scar tissue, (2) mature, non-malignant rhabdomyoblasts that occur as a result of differentiation of RMS cells during therapy, or (3) residual viable tumor. Mature rhabdomyoblasts are often present at the end of therapy and are difficult to distinguish from residual viable tumor. Mature rhabdomyoblasts do not have malignant potential and are not an indication for additional therapy.17, 18 Best treatment response is currently assessed by cross-sectional imaging which cannot distinguish between the aforementioned entities. It is possible that other imaging modalities may better distinguish residual viable tumor from differentiated rhabdomyoblasts or scar formation. Institutional data from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center demonstrated that a complete metabolic response on 18-FDG-PET after 12 weeks of induction chemotherapy was associated with improved progression-free survival (72% vs 44%, p=0.01).19 Similarly, PET imaging at the completion of local control predicted progression free survival (PFS); those with negative PET had PFS of 67% compared to 33% PFS for those with positive PET imaging (p=0.0009). However, confirmation of the correlation between complete metabolic response and clinical outcomes has not yet been validated in a large clinical study group setting. 20 Although it will not address this exact question, comparing the outcome of patients with intermediate risk RMS based on their 18-FDG-PET response at week 9 of induction therapy is an exploratory aim under investigation in ARST1431.

The major new finding from this study is that a residual mass at the end of therapy correlates with inferior FFS for the subset of patients with PM primary sites. Although not statistically significant in the prior analysis from IRS-IV (n=341), those data suggested a potential correlation between residual disease and FFS in children with PM tumors.4 The adjusted hazard ratio for FFS for CR vs PR/NR in patients with PM tumors was 0.63 (p=0.2) in the IRS-IV study. The majority of PR/NR responders had a PM primary site. In the current, larger, pooled analysis, the HR for FFS was similar, but now achieves statistical significance. This difference may have a biologic underpinning. Recurrent mutations of MYOD1 have recently been described in RMS, occurring predominantly at PM primary sites and typically has a distinct sclerosis and spindle cell morphology. RMS with MYOD1 mutation is associated with aggressive biologic behavior and very poor outcomes.21, 22 MYOD1 mutation data was only available for 31 PM patients from our series, with six having a MYOD1 mutation. Future analyses will need molecular annotation to determine whether incomplete radiographic response is associated with MYOD1 mutation status. The difficulty in achieving negative surgical margins at this site may be another potential contributing factor.

In IRS-IV, end-of-therapy surgical procedures were performed in 22% of patients with a best response of PR/NR, but conferred no survival benefit and was complicated by significant patient morbidity including resection of vital structures in more than half of cases.4 In D9803 and particularly in ARST0531, end-of-therapy excision was actively discouraged and this manifested as a reduced rate of end-of-therapy surgery in the current study (ARST0531). Because of the low rate of end-of-therapy surgery in the current study, it is not possible to analyze the impact on clinical outcomes. In the IRS-IV study, it was somewhat surprising that late operative procedures, even complete resection, did not impact outcome. It is known that complete upfront resection is associated with improved outcomes.23 Similarly, delayed primary excision performed after 12 weeks of induction chemotherapy, allows for reduction in radiation dose without inferior local control outcomes.14 It would logically follow that resection of end-of-therapy masses, particularly in the 50% of cases with viable residual tumor would improve local failure-free survival rates, even if at the expense of surgical morbidity. Nonetheless, this conclusion is not supported by the best available current evidence. This may be due to a combination of factors, including small patient numbers limiting statistical power. At best, the 50% of patients with residual viable tumor would be expected to benefit from an end-of-therapy procedure. Furthermore, in a retrospective analysis, the patients who underwent end-of-therapy surgery may have been those with more aggressive-appearing imaging findings, worse underlying biology and other disease characteristics known to negatively impact prognosis. Finally, the inability to achieve R0 tumor resection (only 29% of cases in IRS-IV) may explain the lack of clinical benefit from end-of-therapy surgery. Given the unclear benefit and high risk of surgical morbidity, routine resection of end-of-therapy masses should continue to be discouraged. The role of surgery in select cases with (1) histologically-proven residual viable tumor and/or metabolic activity on PET and (2) findings amenable to R0 resection without excess surgical morbidity remains to be determined.

The pooling of patients from two studies (D9803 and ARST0531) with different treatment regimens, imaging modalities for assessing therapy response, and recommendations to guide DPE are limitations of this study. This heterogeneity was accounted for by adjusting for study (ARST0531 vs D9803) in the Cox regression. Because treatment regimens within each study had similar clinical outcomes, it was also felt appropriate to pool the study populations for this analysis. We are also limited with lack of tissue available to analyze for potential biological factors that may contribute to differences seen among PM patients, including MYOD1. As a sensitivity analysis, we assessed outcomes only for those patients enrolled on ARST0531. Although trends were similar, there was no significant differences in FFS for the PM or non-PM groups when limited to just this single study (Supplemental Table 2). The pooled analysis allows for a robust comparison of clinical outcomes in patients with CR vs PR/NR. However, because only a small subset of the PR/NR patients underwent a procedure for end-of-therapy mass, the risks and benefits of these procedures cannot be delineated.

In summary, end-of-therapy residual mass (best response PR/NR) occurs in 34.6% of clinical Group III participants treated on D9803 and ARST0531. The end-of-therapy response status was only predictive of clinical outcome for PM sites. The increased risk of treatment failure in patients with PM tumors who failed to achieve CR may relate to underlying biologic factors, including mutations in MYOD1. For non-PM sites, the comparable outcomes in patients with CR vs PR/NR may reflect current limitations in anatomic imaging, which is inadequate for distinguishing residual viable tumor from scar or mature rhabdomyoblasts. Better modalities for identifying the presence of residual viable tumor, potentially including assessment of metabolic response by 18-FDG-PET, are required to truly evaluate treatment response. Even when viable tumor is identified at the end of therapy, the impact of additional surgery on clinical outcome is unproven and potentially harmful. Future investigation will be necessary to understand the underlying differences in patients with PM and non-PM tumors in order to improve the outcome for these challenging patients.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Impact:

In this study of 601 children with Group III RMS the authors demonstrate that patients with parameningeal tumors who achieve a complete radiographic response at therapy completion have improved failure-free survival but no difference in overall survival. Radiographic response had no correlation with outcomes for patients with non-parameningeal tumors. Resection of residual end-of-therapy masses was not associated with a survival benefit.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by Children’s Oncology Group Grants U10CA180886, U10CA180899, U10CA098543, and U10CA098413 and Seattle Children’s Foundation, from Kat’s Crew Guild through the Sarcoma Research Fund.

Disclosures

Dr Hawkins reports grant support from Loxo Oncology, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharpe Dohme, Lilly, Eisai, Glaxo Smith Kline, Novartis, Sanofi, Amgen, Seattle Genetics, Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Incyte, as well as non-financial support from Celgene, Loxo Oncology, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Lilly outside the submitted work. Dr Wolden reports personal fees from Y-mAbs Therapeutics outside the submitted work. The other authors have no financial disclosures to report

Abbreviations:

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- RMS

rhabdomyosarcoma

- CR

complete response

- PR

partial response

- NR

no response

- FFS

failure-free survival

- OS

overall survival

- PM

parameningeal

- VAC

vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide

References

- 1.Hawkins DS, Spunt SL, Skapek SX, Committee COGSTS. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: Soft tissue sarcomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1001–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casey DL, Chi YY, Donaldson SS, Hawkins DS, Tian J, Arndt CA, Rodeberg DA, Routh JC, Lautz TB, Gupta AA, Yock TI, Wolden SL. Increased local failure for patients with intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma on ARST0531: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke M, Anderson JR, Kao SC, Rodeberg D, Qualman SJ, Wolden SL, Meyer WH, Breitfeld PP, Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology G. Assessment of response to induction therapy and its influence on 5-year failure-free survival in group III rhabdomyosarcoma: the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-IV experience--a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4909–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodeberg DA, Stoner JA, Hayes-Jordan A, Kao SC, Wolden SL, Qualman SJ, Meyer WH, Hawkins DS. Prognostic significance of tumor response at the end of therapy in group III rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3705–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg AR, Anderson JR, Lyden E, Rodeberg DA, Wolden SL, Kao SC, Parham DM, Arndt C, Hawkins DS. Early response as assessed by anatomic imaging does not predict failure-free survival among patients with Group III rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:816–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparber-Sauer M, von Kalle T, Seitz G, Dantonello T, Scheer M, Munter M, Fuchs J, Ladenstein R, Bielack SS, Klingebiel T, Koscielniak E, Cooperative Weichteilsarkom S. The prognostic value of early radiographic response in children and adolescents with embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma stage IV, metastases confined to the lungs: A report from the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe (CWS). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flamant F, Rodary C, Rey A, Praquin MT, Sommelet D, Quintana E, Theobald S, Brunat-Mentigny M, Otten J, Voute PA, Habrand JL, Martelli H, et al. Treatment of nonmetastatic rhabdomyosarcomas in childhood and adolescence. Results of the second study of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology: MMT84. Eur J Cancer 1998;34:1050–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koscielniak E, Jurgens H, Winkler K, Burger D, Herbst M, Keim M, Bernhard G, Treuner J. Treatment of soft tissue sarcoma in childhood and adolescence. A report of the German Cooperative Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study. Cancer 1992;70:2557–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaarwerk B, van der Lee JH, Breunis WB, Orbach D, Chisholm JC, Cozic N, Jenney M, van Rijn RR, McHugh K, Gallego S, Glosli H, Devalck C, et al. Prognostic relevance of early radiologic response to induction chemotherapy in pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the International Society of Pediatric Oncology Malignant Mesenchymal Tumor 95 study. Cancer 2018;124:1016–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raney B, Stoner J, Anderson J, Andrassy R, Arndt C, Brown K, Crist W, Maurer H, Qualman S, Wharam M, Wiener E, Meyer W, et al. Impact of tumor viability at second-look procedures performed before completing treatment on the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group protocol IRS-IV, 1991–1997: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:2160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arndt CA, Stoner JA, Hawkins DS, Rodeberg DA, Hayes-Jordan AA, Paidas CN, Parham DM, Teot LA, Wharam MD, Breneman JC, Donaldson SS, Anderson JR, et al. Vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide compared with vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with vincristine, topotecan, and cyclophosphamide for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: children’s oncology group study D9803. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5182–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins DS, Chi YY, Anderson JR, Tian J, Arndt CAS, Bomgaars L, Donaldson SS, Hayes-Jordan A, Mascarenhas L, McCarville MB, McCune JS, McCowage G, et al. Addition of Vincristine and Irinotecan to Vincristine, Dactinomycin, and Cyclophosphamide Does Not Improve Outcome for Intermediate-Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2018:JCO2018779694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolden SL, Lyden ER, Arndt CA, Hawkins DS, Anderson JR, Rodeberg DA, Morris CD, Donaldson SS. Local Control for Intermediate-Risk Rhabdomyosarcoma: Results From D9803 According to Histology, Group, Site, and Size: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015;93:1071–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodeberg DA, Wharam MD, Lyden ER, Stoner JA, Brown K, Wolden SL, Paidas CN, Donaldson SS, Hawkins DS, Spunt SL, Arndt CA. Delayed primary excision with subsequent modification of radiotherapy dose for intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee. Int J Cancer 2015;137:204–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peto R PJ. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant test procedures. J R Statist Soc A 1972;135:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine JP GR. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 17.d’Amore ES, Tollot M, Stracca-Pansa V, Menegon A, Meli S, Carli M, Ninfo V. Therapy associated differentiation in rhabdomyosarcomas. Mod Pathol 1994;7:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortega JA, Rowland J, Monforte H, Malogolowkin M, Triche T. Presence of well-differentiated rhabdomyoblasts at the end of therapy for pelvic rhabdomyosarcoma: implications for the outcome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2000;22:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casey DL, Wexler LH, Fox JJ, Dharmarajan KV, Schoder H, Price AN, Wolden SL. Predicting outcome in patients with rhabdomyosarcoma: role of [(18)f]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;90:1136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison DJ, Parisi MT, Shulkin BL. The Role of (18)F-FDG-PET/CT in Pediatric Sarcoma. Semin Nucl Med 2017;47:229–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agaram NP, LaQuaglia MP, Alaggio R, Zhang L, Fujisawa Y, Ladanyi M, Wexler LH, Antonescu CR. MYOD1-mutant spindle cell and sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma: an aggressive subtype irrespective of age. A reappraisal for molecular classification and risk stratification. Mod Pathol 2019;32:27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rekhi B, Upadhyay P, Ramteke MP, Dutt A. MYOD1 (L122R) mutations are associated with spindle cell and sclerosing rhabdomyosarcomas with aggressive clinical outcomes. Mod Pathol 2016;29:1532–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meza JL, Anderson J, Pappo AS, Meyer WH, Children’s Oncology G. Analysis of prognostic factors in patients with nonmetastatic rhabdomyosarcoma treated on intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma studies III and IV: the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3844–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available upon reasonable request and publicly within one year after publication. Requests for access to the data can be made on a National Cancer Institute website: https://nctn-data-archive.nci.nih.gov/